Elder abuse: Understanding issues, frameworks and responses

February 2016

Rae Kaspiew, Rachel Carson, Helen Rhoades

Download Research report

Overview

This report provides an overview of elder abuse in Australia - including its characteristics, context, and prevention. First, it considers definitional issues and what is known about prevalence and incidence, risk and protective factors, and the dynamics surrounding disclosure and reporting. The report then sets out evidence on the demographic and socio-economic features of the Australian community that are relevant to understanding social dynamics that may influence elder abuse, including intergenerational wealth transfer and the systemic structures that intersect with elder abuse. Lastly, the report considers legislative and service responses and Australian and overseas approaches to prevention.

Key messages

-

Evidence about prevalence in Australia is lacking, though if international indications provide any guidance, it is likely that between 2% and 14% of older Australians experience elder abuse in any given year, with the prevalence of neglect possibly higher.

-

The available evidence suggests that most elder abuse is intra-familial and intergenerational, with mothers most often being the subject of abuse by sons, although abuse by daughters is also common, and fathers are victims too.

-

Financial abuse appears to be the most common form of abuse experienced by elderly people, and this is the area where most empirical research is available. Psychological abuse appears slightly less common than financial abuse, and seems to frequently co-occur with financial abuse.

-

The problem of elder abuse is of increasing concern as in the coming decades unprecedented proportions of Australia’s populations will be older: in 2050, just over a fifth of the population is projected to be over 65 and those aged 85 and over are projected to represent about 5% of the population.

-

Our federal system of government means that responses to elder abuse are complicated as they are contained within multiple layers of legislative and policy frameworks across health, ageing and law at Commonwealth and state level.

1. Introduction

This report provides a broad analysis of the issues raised by elder abuse in the Australian context. Elder abuse - which involves the physical, emotional, sexual or financial abuse or neglect of an older person by another person in a position of trust - presents a range of complex challenges for the Australian community. Although solid evidence about prevalence in Australia is lacking, the incidence of elder abuse will certainly increase as Australia's "baby boomer" generation reaches old age, with increased life expectancy meaning that the aged will, in coming years, comprise a greater proportion of the population than ever before. Fundamentally a human rights issue, responses to the management and prevention of elder abuse sit within a range of complex policy and practice structures across different levels of government, and various justice system frameworks within the private sector and across non-government organisations.

In this respect, the management of elder abuse has similar features to family and domestic violence, sexual assault and child protection. Recognition of the need for a national approach to family and domestic violence (and specifically violence against women and their children) and to child protection has seen the development in the past ten years of family and domestic violence national plans and child protection frameworks, all auspiced by the Council of Australian Governments. The structures and frameworks in the areas of ageing generally and elder abuse particularly have parallels with those that shape responses to family and domestic violence and child protection, but the range of frameworks is greater and more complex. From a policy perspective, Commonwealth, state and territory governments have intersecting responsibilities in relation to ageing, aged care and health. Local governments also have responsibility for the delivery of services to the aged. Many of the legal issues potentially raised by elder abuse - such as criminal justice responses and the legislative and organisational infrastructure that deals with matters including substituted decision making and wills and estates - are the preserve of the states and territories. A range of professions, disciplines and organisations interact with elders and their family members. Professionals from health, law, social work and the banking and financial industry potentially engage with elder abuse in their day-to-day practice, and a range of public, private and non-government organisations provide aged care services in private and public settings.

Against this complex structure and organisational background, this report provides an overview of the issues raised by elder abuse in Australia. It also draws on international material where relevant. The report first considers definitional issues in relation to elder abuse and what is known about prevalence and incidence, risk and protective factors and the dynamics surrounding disclosure and reporting. It then sets out some evidence on the demographic and socio-economic features of the Australian community that are relevant to understanding social dynamics that may influence elder abuse. Section 6 outlines some of the features of the systemic structures that intersect with elder abuse and section 7 considers prevention. Section 8 discusses international approaches.

2. What is elder abuse?

Varied conceptualisations of elder abuse are evident in different frameworks and disciplines (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [UNDESA], 2013). One of the dominant disciplines in the field has been social gerontology, which is concerned with the study of ageing. Human rights and public health perspectives are also evident, and intersecting fields of thinking and concern include those related to family violence, violence against women, and disability. An approach informed by an older adult protection philosophy arising from the discipline of geriatrics in medicine has influenced some approaches in the United States, including the establishment of adult protective services (UNDESA, 2013; also see section 8.2). In Australia, approaches of organisations concerned with elder issues, such as COTA Australia (the peak national organisation representing the rights, needs and interests of older Australians), tend to be informed by human rights conceptualisations that emphasis self-determination, autonomy and respect (Department of Health, Victoria, 2012).

The way in which elder abuse issues and responses are approached depends on the perspective adopted. The WHO takes a public health perspective, adopting a 1995 definition developed by Action of Elder Abuse UK to describe elder abuse as "a single or repeated act or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person" (WHO, 2008, p. 6). This is the definition adopted in some Commonwealth frameworks in Australia (e.g., MyAgedCare). A working definition put forward by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2015), again from a public health perspective, is more specific: "an intentional act or failure to act by a caregiver or another person in a relationship involving an expectation of trust that causes or creates a risk of harm to an older adult" (defined as someone age 60 or older). It also provides working definitions of specific types of abuse (see Appendix).

A commonly applied definition locally is that adopted by the Australian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse in 1999 (also based on the Action of Elder Abuse UK definition), which specifies that elder abuse is:

any act occurring within a relationship where there is an implication of trust, which results in harm to an older person. Abuse may be physical, sexual, financial, psychological, social and/or neglect.1

Although these definitions have similar elements, the absence of a precise agreed definition is considered problematic for a range of reasons, not the least of which is the difficulty in measuring elder abuse. One important area where this is evident is in relation to the age at which one might be considered an elder. For the purpose of the WHO and CDC definitions, 60 is the defining age. In Australia, however, for statistical and range of other purposes, including access to the pension (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2012b), 65 is the starting point for status as an "elder", and 70 is the age for access to aged care services (Cotterell, Leonardi, Coward, Thomson, & Walters, 2015). The definition of "older" Australian used in this paper is consistent with that used by the ABS, which classifies people over 65 as "older". It should be noted, however, that some definitions, studies and services concerned with elder abuse use the age of 60 as a starting point. The literature on ageing also distinguishes between "old" people (65-84 years) and "old old" people, aged 85 and above (e.g., Wainer, Owada, Lowndes, & Darzins, 2011). The discussion in section 3 establishes that this is a useful distinction to make from a statistical viewpoint as there are significant differences in some areas between these age groups. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who have a substantially lower life expectancy than non-Indigenous peoples, a lower age for those who are "older" is considered appropriate (e.g., 45-50 years; Cotterell et al., 2015).

At a more complex level, as a "multi-faceted construct involving intentional and unintentional actions of both a passive and an active nature" (Clare, Blundell, & Clare, 2011, p. 44), consideration of the definition of elder abuse raises the fundamental question of what purpose the definition serves. A recent critique by a Western Australian research team (Clare et al., 2011) has raised several other concerns, arguing that, in addition to the age question, the term "elder abuse" needs to be fundamentally reconsidered. In addition to the operational complications arising from the application of different definitions in different legal, policy and practice frameworks in the Western Australian context, Clare and colleagues called for a debate on whether age should be the defining aspect of elder abuse, or whether it should be conceptualised on the basis of "an assessment of capacity for self-care and self-protection" (p. 40).

This analysis highlights an important issue in considering definitions, given that many of the behaviours captured by the definition may be experienced at any stage of the life course and are covered by various criminal and civil law frameworks. From a conceptual standpoint, this raises the question of whether harmful behaviours involving older people are distinguishable from harmful behaviours involving other adults because they involve older people or because they involve the exploitation of vulnerability. A further significant question that arises in this context is how, in such an analysis, issues such as the dynamics of dependence (section 3) should be dealt with.

Considering the phenomenon of elder abuse more broadly, theoretical models and approaches attribute its occurrence to a complex array of factors, including social and cultural attitudes to the aged. The international literature draws common links between the causes of and conditions for the occurrence of different kinds of abuse and maltreatment, including family violence, child abuse and neglect, and elder abuse (Wilkins, Tsao, Hertz, Davis, & Klevens, 2014; WHO, 2002b). Originally developed to support the conceptualisation of family violence prevention approaches, the socio-ecological model is also considered to be an apt approach in relation to elder abuse (WHO, 2002b). This model posits that interpersonal violence occurs as a result of interactions between factors at four levels of influence: individual, relationship, community and societal. In relation to violence against women across these four levels, attitudes inconsistent with the equality of women are associated with higher levels of family violence. An analogous approach is evident in relation to elder abuse, in which age discrimination and a lack of respect for elders are are societal factors associated with its occurrence (Gil et al., 2015; Hayslip, Reinberg, & Williams, 2015; Mann, Horsley, Barrett, & Tinney, 2014; WHO, 2002b). The authors of a recent prevalence study in Portugal noted that the findings of the study demonstrate that "prevalence rates vary by type of abuse, the victims socio-demographic characteristics, the victims' relationship with the perpetrator … The social responses toward victim protection and collective representations of this social problem, such as the belief systems, cultural norms, and social attitudes towards violence (e.g., higher or lower tolerance toward it) are structural dimensions that indirectly influence it" (Gil et al., 2015, p. 190).

Although different types of interpersonal violence are considered to have common elements in this theoretical model, a range of different theoretical and practice paradigms are applied in relation to each kind of violence. Responses to family violence, for example, have developed out of a feminist framework, and some Australian and American analyses have highlighted theoretical and practical tensions in responses to family violence involving women when feminist and gerontological approaches intersect internationally and locally (Bagshaw, Wendt, Zannettino, & Adams, 2013; Cramer & Brady, 2013). Similarly, analogies between child abuse and elder abuse are seen as problematic in some respects, as "making comparisons between elder abuse and child abuse, and drawing on responses used in child protection, is ageist and generally not appropriate" (Australian Association of Gerontology, 2015, p. 4). However, the structural and systemic issues raised by elder abuse, as highlighted in this and other reports, mean that recent experience in developing national approaches to child protection (the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children) and family violence (the National Plan for the Reduction of Violence Against Women and Their Children) provide insight into the development of national approaches in relation to complex issues involving multiple levels of governments and a spread of different agencies.

Progress towards understanding elder abuse and developing effective response and prevention measures, are recognised to be considerably less well developed than in other areas of interpersonal violence, including family violence and child abuse (WHO, 2014). The following section outlines what is known about prevalence and risk factors internationally and locally.

1 See the Definition of Elder Abuse at: <www.arasagedrights.com/definition-of-elder-abuse.html>.

3. What is known about the prevalence and dynamics of elder abuse?

This section considers evidence on the prevalence and incidence of elder abuse generally and of the different types of elder abuse that occur. The discussion establishes that there is very limited evidence in Australia that would support an understanding of the prevalence of elder abuse, and there is emerging recognition of the need for systematic research in this area (e.g., Elder Abuse Prevention Unit [EAPU], n. d.). There is some limited evidence on the incidence of elder abuse, mainly based on data derived from calls to state-based elder abuse helplines. There is also some international research on prevalence in different countries - the United States, the United Kingdom and Portugal, for example - but these studies have used different definitions and methodologies.

The discussion in this section first sets out the international evidence on prevalence and then considers what is known about the phenomenon in Australia.

The available evidence suggests that prevalence varies across abuse types, with psychological and financial abuse being the most common types of abuse reported, although one study suggests that neglect could be as high as 20% among women in the older age group (Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health [ALSWH], 2014). Older women are significantly more likely to be victims than older men, and most abuse is intergenerational (i.e., involving abuse of parents by adult children), with sons being perpetrators to a greater extent than daughters. For some women, the experience in older age of family violence, including sexual assault, represents the continuation of a lifelong pattern of spousal abuse (Cramer & Brady, 2013; Mann et al., 2014; UNDESA, 2013). Evidence on elder abuse occurring outside of a familial context (e.g., in care settings) is particularly sparse.

At the international level, the WHO (2015) recently reported that estimated prevalence rates of elder abuse in high- or middle-income countries ranged from 2% to 14%, with the following prevalence rates for the most common types of elder abuse:

- physical abuse (0-5%);

- sexual abuse (0-1%);

- psychological abuse, above a threshold for frequency or severity (1-6%);

- financial abuse (1-9%)

- neglect (0-6%).

These prevalence estimates are based on data sources involving elderly people living in private and community settings and do not include those in institutional care or those with a cognitive impairment. These two latter limitations are characteristic of most prevalence studies, which therefore only reflect a partial view of the extent of elder abuse.

3.1 Prevalence studies

International

A US study based on 5,777 respondents (aged 60 and over), contacted through random-digit dialling in 2008, found that one in ten respondents had experienced elder abuse in the past year (Acierno, Hernandez, & Kilpatrick, 2010). The most common types of abuse were: financial abuse by a family member (5%), potential neglect (5%), and emotional abuse (5%). Physical abuse (2%) and sexual abuse (1%) were substantially less common.

A very different approach was taken in assessing prevalence in the UK Study of Abuse and Neglect of Older People (O'Keeffe et al., 2007). This study was based on face-to-face interviews with 2,111 people aged over 66 living in private settings across the UK in 2006. The study measured whether the participants had experienced mistreatment in the preceding 12 months at the hands of a family member, friend or care worker. Overall, 4% of the sample reported mistreatment in the defined period, comprising 4% of women and 1% of men. In this study, neglect (1%) and financial abuse (0.7%) were the most common forms of abuse, followed by psychological and physical abuse (each 0.4%). Sexual abuse was reported uncommonly (0.2% of women). The dominant relationship dynamic associated with abuse in this study was spousal, with 51% of perpetrators reported to be a spouse or partner, and married people more likely to report being abused compared to widows (9% cf. 1%). The other big perpetrator group was "another family member" (49%). Other reported perpetrators were care workers (13%) and close friends (5%).

A prevalence study from Portugal, based on a sample of 1,123 people aged over 60 living in private households, found that 12% had experienced elder abuse in the preceding twelve months (Gil et al., 2015). The relative distribution of the types of abuse were broadly consistent with the US findings, with financial and psychological abuse most common (6% each). Neglect was less common in the Portuguese sample (0.4%), though this may reflect the application of different definitions in the studies. Physical abuse was reported by 2% of participants, and sexual abuse by 0.2%. In this study, the largest group of defined perpetrators was ex-spouses or partners (14%), followed by sons and step-sons (13%), and daughters and step-daughters (6%). "Other relatives" accounted for incidents of abuse in 42% of cases, friends and neighbours in 16%, and paid professionals in 4%. One in five respondents refused to identify the perpetrators.

Australia

In Australia, there are two population-based studies that have yielded some insights into the extent to which older women experience violence, but there are limitations in the measures used and the extent to which they assess concepts relevant to elder abuse. One is a recently published, detailed analysis of data from the Personal Safety Survey (ABS, 2012a) by Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety (ANROWS) (Cox, 2015). The age range for "older women" in that study was 55 plus, and the analysis was framed to assess violence against women, focusing on sexual assault by any perpetrator, and partner violence involving physical assault, physical threat, sexual assault and sexual threat by a cohabiting or intimate partner. In relation to cohabiting partner violence, 0.4% of women aged 55 and older reported this experience in the preceding 12 months (c. 12,800 women), compared with 3% of 25-34 year old women, the age group where this form of violence is most common. In relation to sexual assault, 0.2% of the sample aged 55 plus (c. 7,000 women) reported experiencing sexual assault in the preceding twelve months, against a national average rate across all age groups of 1%.

The other population-based study to yield approximations of prevalence of elder abuse (for women only) is the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women's Health (2014), which has measures relevant to vulnerability, coercion, dependence and dejection. This study is based on a random sample of women using a sampling frame from Medicare, with the oldest cohort (n = 5,561) being born between 1921 and 1926. When this cohort was surveyed in 2011 (at age 85-90), the findings suggested that 8% had experienced vulnerability to abuse, with name calling and put-downs being the most common forms. A similar level of prevalence was evident for this cohort in a preceding wave, conducted in 2008 (age 82-87), and slightly lower prevalence levels were found at younger ages (70-81 years). Measures the researchers used to assess neglect indicate a relatively stable prevalence rate of about 20% across waves, from ages 70-75 and 85-90 years.

Studies based on data from calls to helplines for elder abuse provide some further insights into the occurrence of elder abuse in Australia. There are three recently published sources from Queensland (Spike, 2015), Victoria (Joosten, Dow, & Blakey, 2015) and NSW (NSW Elder Abuse Helpline and Resource Unit, 2015). They reflect circumstances in which elder abuse is known or suspected and a person concerned has decided to seek advice on the situation.

In Queensland, calls to the EAPU helpline have increased substantially over the period that it has been operating, from just over 200 in 2000-01 to nearly 1,300 in 2014-15 (Spike, 2015; see further discussion in sections 3.2-3.4). The EAPU analysis of call data from the past five years provides a profile of the elder abuse concerns notified to the helpline. The calls were mostly in relation to female victims (68% female cf. 31 male cf. 1% unknown). The most common age group of victims was 80-84 years (23%), followed by 75-79 years (16%) and 85-89 years (15%). Perpetrators were male in 50% of calls and female in 45% (unknown: 5%). Where perpetrator age was known, the most common age group was 50-54 years (17%). Children were the largest groups of perpetrators reported (31% sons, 29% daughters). Otherwise, 10% were "other relatives", 9% a spouse/partner, and 21% fell into a combined category of neighbours, friends, workers and informal carers.

In 2014-15, the most commonly reported type of abuse to the EAPU helpline was financial abuse, accounting for 40% of reports, compared to 35% for psychological abuse, which had been the most common type up to 2012-13. The next most common types were neglect and social isolation, at about 10% each. Physical abuse was reported in just under 5% of calls, and sexual abuse was referred to in about 1% of calls. Where the perpetrator was a partner or spouse, the most likely form of abuse was psychological (41%). Where the perpetrators were adult children, financial abuse (39%) and psychological abuse (38%) were the most common types of abuse.

In Victoria, a recent study by the National Ageing Research Institute (Joosten et al., 2015), commissioned by Seniors Rights Victoria (SRV), was based on an analysis of data derived from records of calls to a helpline operated by SRV between July 2012 and June 2014. Of 755 calls, 455 involved discussion of a matter that raised elder abuse issues (including some that raised multiple types of abuse), and 236 raised issues not relating to elder abuse. The most common concerns raised in relation to elder abuse were about financial abuse (61%) and psychological or emotional abuse (59%). Physical abuse was raised much less frequently (16%), as were social abuse (9%), neglect (1%) and sexual abuse (0.4%). Elder abuse issues were most commonly reported in relation to female victims (73% females cf. 28% males) and the most commonly reported perpetrators were male (60% males cf. 40% females). The majority of perpetrators of the abuse reported to the SRV helpline were children of the victim (67%), with sons responsible for 40% of incidents reported, and daughters for 27%. Spouses were reported to be responsible in small proportions of cases (5% husbands and 3% wives).

In NSW, two years of call data (n = 3,388) to the NSW Elder Abuse hotline (NSW Elder Abuse Helpline and Resource Unit, 2015) reveal broadly similar patterns to the Queensland and Victorian data. Women were most commonly reported to be the victims (71% women cf. 28% men), and the most common age group of concern in the calls was 75-84 year olds (33%). In 71% of calls, the perpetrators were family members, and the largest group of perpetrating relatives were adult children (26% sons and 21% daughters). Just over one in ten (12%) of perpetrators were spouses. The most common abuse type reported in the calls was psychological abuse (57%), followed by financial abuse (46%), neglect (25%), physical abuse (17%) and sexual abuse (1%).

Three reports completed in the past five years (Clare et al., 2011; Miskovski, 2014; Wainer, Darzins, & Owada, 2010) have used data from a range of agencies to assess the extent and nature of elder abuse. The reports by Wainer, Darzins et al. and Miskovski specifically focused on financial abuse, and this kind of abuse emerged as the predominant concern in the report by Clare et al. Each of these reports illustrated the point that because responses to elder abuse are spread across different legal, policy and practice frameworks, the evidence available from these sources offers a piecemeal empirical understanding of elder abuse.

3.2 Risk factors and consequences

In the absence of systematic local research, insight into the factors that may mean older Australians are at higher risk of experiencing abuse, or the factors that may protect them against this risk is limited. As the discussion in the preceding section indicates, women are at higher risk of experiencing elder abuse than men (in part reflecting their greater representation in the older population; see further below). The literature indicates that there are different risk factors for different types of abuse. Among the common overall risk factors identified for which the empirical evidence is strong are when the older person has cognitive impairment or another disability, is isolated, or has a prior history of traumatic life events (Acierno et al., 2010; O'Keeffe et al., 2007; WHO, 2015). This section provides an overview of the main points that emerge from the literature on these issues.

Cognitive impairment or other disability

Cognitive impairment and other forms of disability are established in the research literature as having a strong association with being vulnerable to elder abuse (Acierno et al., 2010; Gil et al., 2015; WHO, 2015). The World Health Organization (2015) uses the term "intrinsic capacity" to refer to "all the physical and mental capacities" of an individual (p. 28), recognising that this varies across the life course and is influenced by a range of factors, including genetics (75%) and exposure to a variety of personal factors, such as socio-economic status. On average, intrinsic capacity peaks at age 20 and declines thereafter, with the rate of decline increasing from age 60. Compromised intrinsic capacity (as a result of conditions such as dementia or care dependence), which occur along a continuum ranging from low to severe, are associated with heightened risk of elder abuse, but are also a consequence of elder abuse (WHO, 2015). "Capacity", in a narrower sense, is a central concept in legal, medical and other responses to elder abuse, which recognises that there are degrees to which a person has capacity, and capacity may be present for some functions but not for others. In broad terms, capacity is the ability to make reasonable decisions. The link between cognitive impairment, which leads to reduced capacity, and elder abuse is well established (Acierno et al., 2010; Gil et al., 2015 & O'Keeffe, et al., 2007).

The Queensland EAPU analysis of helpline data (derived from calls made predominantly by family members and friends, but also from professionals) established that the incidence of abuse types observed varies according to whether the victim is reported to have dementia (Spike, 2015). Financial abuse is reported to occur at similar rates whether or not the victim has dementia, but psychological abuse (as a primary abuse type) occurs about half as often when the victim has dementia. This suggests that psychological abuse occurs to support financial abuse where dementia is not present, but is no longer necessary where dementia is present. Spike (2015) observed that "where financial motives are driving psychological abuse, once a victim has lost the capacity to manage their finances, psychological abuse becomes either: ineffectual as the victim no longer has the ability to direct their funds; or unnecessary because the perpetrator already has full access to the victim's assets". Miskovski (2014) observed the link between psychological abuse and financial abuse, noting that the former is a grooming behaviour for the latter.

Social isolation and traumatic life events

Social isolation has a well-established association with being vulnerable to elder abuse (Acierno et al., 2010; ALSWH, 2014; O'Keeffe et al., 2007; WHO, 2015). There are several dimensions to the connection between this condition and elder abuse. Isolation renders elders more vulnerable to exploitation for psychological, emotional and physical reasons, and it also means that abusive behaviour is less likely to be discovered due to the absence of social and other networks around the older person. Mariam, McLure, Robinson, and Yang (2015) explained the issues in this way:

As with most forms of abuse, access to the potential victim is a significant risk factor for the emergence of or continuation of elder abuse. Also in regard to living arrangements, social isolation has been shown to contribute to and result from ongoing abusive situations. Caregivers, family members and potential victims who lack substantial social networks experience increased demand on a limited number of caregivers and decreased social sanctions as a result of abusive behaviour, and they may avoid further social interactions out of shame or fear of discovery. (p. 20)

The association between experiences of elder abuse and previous traumatic events, including interpersonal and domestic violence, is evident in a range of sources (Acierno et al., 2010; Mann et al., 2014; UNDESA, 2013) and suggests elder abuse reflects the perpetuation of complex familial dynamics. Acierno et al. observed in their study that these experiences increased the risk of emotional, sexual and financial mistreatment. They suggested that:

there may be some shared variance between causes of these forms of mistreatment and precipitants of traumatic life events. On the most obvious level, interpersonal environments characterized by exposure to traumatic events are probably also more likely to contain abusive individuals over time. (p. 295)

There is a lack of detailed insight into the dynamics of intergenerational elder abuse in this context, and the extent to which elder abuse may be a response to the abusive adult child being abused or exposed to abuse in childhood involving the elder or other adults. Each of these dynamics is referred to in material emanating from practice perspectives on elder abuse,2 but empirical evidence is limited. A Canadian study examining prevalence and risk factors for "spouse abuse" at two different life stages (45-59 years, and 60 years and over) found slightly diminished rates of spousal abuse in the older sample, but a similar distribution between types of abuse (Yon, Wister, Mitchell, & Gutman, 2014). In the mid-age cohort, 9% experienced emotional/financial abuse, and 2% physical/sexual abuse. In the older cohort, the prevalence of emotional/financial abuse was 7%, and 1% for physical and emotional abuse.

Other factors

Other factors that have been established as risk factors for the perpetration of elder abuse include the perpetrator’s depression or alcohol and drug misuse, and the perpetrator being in a position of financial, emotional or relational dependence with the victim (WHO, 2015).

More generally, a theme that emerges from the analytic literature on elder abuse, but has not necessarily been directly measured in research, relates to attitudes and values (Gil et al., 2015; UNDESA, 2013; WHO, 2002a, 2015). As flagged at the outset, attitudes and values are associated with elder abuse in several different ways. Generally, social and individual values that fail to accord respect and consideration to elders and their human rights are considered to create an environment conducive to elder abuse (Peri, Fanslow, & Hand, 2009). Some literature points to an association between gender roles and elder abuse, particularly financial abuse, because under traditional gender role paradigms, women have not expected, or been expected, to take responsibility for financial matters. In this respect, norms that support women's relinquishment of financial control to others are also seen to be conducive to creating opportunities for elder abuse (Peri et al., 2009).

Consequences

Elder abuse has a range of physical, psychological and financial consequences. It can result in pain, injury and even death, and is associated with higher levels of stress and depression and an increased risk of nursing home placement and hospitalisation (WHO, 2015). Darzins, Lowndes, and Wainer (2009) referred to research suggesting that the effects of financial abuse on the elderly tend to be greater than on young people, as older people lack the capacity and time to recoup their financial losses, and those who suffer financial abuse experience "higher levels of psychological distress and depression than their peers … decline in physical health coupled with decreased resources for managing their healthcare" (p. 12).

Prevention

Preventative responses to elder abuse are generally seen to be underdeveloped in Australia. Directions in the themes underpinning thinking about prevention have two broad elements locally and internationally. The first is oriented toward changing the values and attitudes among the broader community and among professionals and individuals who interact with elders to address ageist (and sexist) assumptions and attitudes and to develop understanding of ageing processes, including potential cognitive decline. The second is oriented toward mitigating the risk factors for elder abuse, through measures to reduce social isolation, increase autonomy and empowerment, and support retention of control over financial affairs, or at the very least to help elders maintain knowledge of their financial affairs (e.g., Mariam et al., 2015; Wainer, Darzins et al., 2010). These issues are further discussed in section 7.

3.3 What is known about particular types of elder abuse?

Financial abuse

Of the different types of abuse identified in the preceding section, financial abuse is the most well researched in Australia. Evidence is sparse on the other kinds of abuse, although there is one recent qualitative study on sexual abuse and older women. There is little research on psychological abuse and neglect, although, as noted earlier, there is some evidence that suggests psychological and financial abuse often co-occur, and that psychological abuse may be a form of "grooming for financial abuse" (EAPU, n. d.; Miskovski, 2014; Wainer, Darzins et al., 2010).

The WHO (2002a) defines elder financial abuse as "the illegal or improper exploitation or use of funds or resources of the older person" (p. 3). Darzins et al. (2009) estimated that this experience affects between 0.5% and 5% of older Australians. The forms that financial abuse takes are varied, and it is this kind of abuse that is most likely to come to the attention of professionals across various areas (including banking, law and the welfare sector) because it may involve transactions and engagement with institutions and organisations. Financial abuse covers a spectrum of behaviours, and a guide published by Seniors Rights Victoria describes it as existing "in the grey area between thoughtless practice and outright theft" (Kyle, 2012, p. 7).

Several studies and analytic reports have raised concerns about financial management practices that are risky from the perspective of both the elder whose finances are being managed and the person managing them. Assistance in managing financial arrangements may be informal or formal in nature, ranging from informal responsibility for banking and bill payments, to substantial responsibility for financial arrangements being assumed. The frameworks and instruments governing formal transfers of financial responsibility are those relating to enduring power-of-attorney instruments, which are executed when a person has capacity, and allow another person (the attorney) to take responsibility for financial matters. If an enduring power of attorney has not been executed and it becomes necessary for someone else to exercise responsibility for an elder's financial affairs, then application must be made to a guardianship board or tribunal. It appears that anticipatory execution of enduring power-of-attorney instruments is common, with one study of supported asset management identifying 69% of a sample of 421 Victorians aged 65 and over using an enduring power of attorney (Tilse, 2007, as cited in Wainer, Darzins et al., 2010).

In 2010, Wainer, Darzins, and Owada observed that "supported asset management is a common experience for family members and there is much work to be done to understand the dynamics of this form of care, particularly in a multi-cultural society" (p. 6). In this area, varying societal values about the extent to which assets are considered communal or personal within a family are evident, and it is also evident that expectations are culturally determined (Miskovski, 2014; Wainer, Darzins et al., 2010). The study by Wainer, Darzins and Owada was based on an analysis of data from a range of agencies whose operations bring them into contact with elder financial abuse in Victoria. The findings of this study, consistent with the discussion in section 3.2, showed that, to the extent data were available, between one- and two-thirds of the elderly concerned were vulnerable because of dementia. The interviews with professionals also confirmed that financial abuse was accompanied by psychological abuse that was intimidating, controlling and fear inducing. Among the ways in which financial abuse was carried out were through misuse of powers of attorney, coerced changes to wills, unethical trading in title to property, and the coercion of people without capacity into signing documents in relation to assets that would result in financial gain for the perpetrator. Concerns were also raised, particularly by professionals from helplines, in relation to situations where adult children were dependent on aged parents for accommodation or financial support by reason of addiction or mental ill health, but failed to fulfil reciprocal expectations in relation to caregiving activities. Another area where financial abuse was identified was where an adult child held power of attorney and was also the beneficiary of a will and acted to preserve their inheritance by not selling the family home to release funds for an assisted accommodation bond, even though this was needed for their parent. Another analysis of the circumstances in which concerns about financial abuse arise indicated that in some circumstances adult children holding powers of attorney may use this power to gain pre-mortem control over heritable property and exhaust the resources in the estate, to the disadvantage of the other beneficiaries (Miskovski, 2014).

Wainer, Darzins et al. (2010) concluded that the legal system was rarely used and unhelpful when trying "to prevent or remedy financial abuse". There were a number of reasons for this, including privacy issues and the lack of an easily identifiable and accessible mechanism for reporting concerns. These findings are consistent with those of a multi-dimensional study by Tilse et al. (2005) on practices surrounding the management of older people's assets. The research found poor understanding of legal obligations and mechanisms in relation to assisted asset management among elder people and those caring for them. It also highlighted "attitudes that suggest entitlement" to the older person's assets, that together with risky asset management practices, created the conditions for financial elder abuse. Concluding that legal redress is often unattainable for practical reasons (assets are unrecoverable) or personal reasons (the older person decides that maintaining relationships is more important than pursuing justice), the researchers highlighted the need for a cross-sectoral approach involving financial institutions, advocacy organisations and agencies concerned with providing services to older people.

Bagshaw and colleagues (2013) examined in separate surveys the views of 209 service providers on the risk factors for elder financial abuse, and the concerns of 114 older people and their family members about financial abuse. Six risk factors were identified by majorities of services providers:

- a family member having a strong sense of entitlement to an older person's property or possessions (84%);

- an older person having diminished capacity (82%);

- an older person being dependent on a family member for care (81%);

- a family member having a drug or alcohol problem (73%);

- an older person feeling frightened of a family member (73%); and

- an older person lacking awareness of his or her rights and entitlements (72%).

About half of the sample of older people and their family members indicated they did not have concerns about financial management issues. The balance indicated they were "somewhat concerned" (30%), "concerned" (8%) or "very concerned (18%).

Sexual abuse

As the prevalence and helpline data set out in section 3.1 indicate, sexual abuse appears to be an uncommon form of elder abuse; however, the ANROWS analysis of Personal Safety Survey data suggests it is potentially experienced by thousands of older women annually.

Empirical evidence in this area is limited, but a recent study by researchers at La Trobe University has shed some light on the issue. Mann and colleagues (2014) conducted a study involving professionals concerned with sexual assault, service providers in aged care services, and women over 65 who had experienced sexual assault, their family members and friends. The findings showed that "the sexual assault of older women occurs in a wide range of contexts, settings and relationships. Older women remain vulnerable to sexual assaults by husbands/partners and family members. They can also face threats from service providers that they may rely on for general care, health care and intimate care. Assaults in such settings can be perpetrated by female as well as male staff" (p. 2). The research highlighted a lack of mechanisms to ensure that professionals such as personal care workers were fit for the responsibilities of working with the aged, and suggested a need for licensing of these workers and a way of conducting background checks analogous to the Working with Children Checks that are required for people who work with children (Child Family Community Australia, 2014). It also revealed mixed views on the question of reporting obligations, with evidence of some support among professionals for mandatory reporting. Concern was expressed in relation to gaps in reporting obligations. Most significantly, the research highlighted the fact that no statutory reporting obligations apply in aged care services that do not receive Commonwealth government funding. The researchers also expressed concern about the narrow statutory reporting obligations in the Aged Care Act 1997 (Cth) in relation to Commonwealth-funded facilities, and the implications of the discretion not to report (where reporting would otherwise be mandatory) in circumstances where the reportable act is committed by a person with cognitive impairment.

3.4 Elder abuse in particular contexts

As with elder abuse in general, insight into elder abuse in particular contexts is limited, including among Aboriginal communities, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, rural communities, and gay, lesbian, bisexual, transsexual, intersex and queer (GLBTIQ) communities (Higgins, 2004). As the dynamics of elder abuse are context dependent, there remains much to be understood about the extent to which the dynamics of elder abuse are different or similar in varying contexts, and the extent to which different responses may be required.

In relation to elder abuse in Aboriginal communities, a 2005 report by the Office of the Public Advocate in Western Australia established that in the Aboriginal context, even at the level of terminology, the conceptualisation of the mainstream concept of elder abuse requires reconsideration. Both the terms "elder" and "abuse" were considered problematic, as "elder" has a specific meaning in Aboriginal communities, and "abuse" may be considered inapt and confrontational. The research indicates that, as in the non-Aboriginal context, the most common type of abuse is financial but that other types of abuse also occur. Two factors that were identified as having particular implications in the Aboriginal context were cultural obligations and the circumstances of grandparents. From a cultural perspective, Aboriginal norms in relation to reciprocity, the expectation that resources will be shared, and kinship (where a wide variety of relationships are involved in familial and community networks), are dimensions that complicate understandings of whether and how elder abuse is occurring. The extent to which calls on grandparent resources to care for grandchildren are culturally reasonable or unreasonable was also highlighted by the research. Substantially more work is required to understand and conceptualise elder abuse in the Aboriginal context, especially among different groups in different circumstances, given the diversity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

In CALD communities, the literature suggests that a number of factors can heighten vulnerability to abuse, including language difficulties for those whose primary language is not English, social dependence on family members for support, and the potential conflict caused by cross-generational expectations in relation to care (Bagshaw et al., 2009). Two studies have shed some light on these issues, although of course the extensive range of cultures represented in our community, the spread of religious and cultural values, and the diverse range of settlement and migration pathways and timeframes mean that a complex range of dynamics will be relevant in different families and communities. A study by Wainer and colleagues (2011) examined practices in Greek, Italian and Vietnamese communities in relation to asset management, enduring power of attorney instruments and wills, and knowledge about elder abuse. The research highlighted similarities and differences between these groups in their awareness of and attitudes to elder financial abuse, and in relation to assisted asset management should that become necessary. All three groups had an awareness of elder financial abuse, and Italians were more likely than the other groups to know of examples of this. Greeks were most likely to believe elder financial abuse to be common, and the Italians and Vietnamese were least likely to believe this. All three groups intended to rely on family members for assistance with asset management should they be unable to manage this themselves. The use of wills and enduring powers of attorney was high among Italian and Greek participants, but not the Vietnamese.

In a focused case study exploration, Zannettino, Bagshaw, Wendt, and Adams (2015) documented one account where a mother, born in a northern European country, was reported by her son to have been isolated from her other children by her abusive daughter. One consequence of the abuse was that the mother was coerced into signing a will leaving the majority of the estate to the abusive daughter. The authors concluded that the case study demonstrates "the relationship between financial and emotional abuse in the context of CALD older people, whose isolation from the dominant culture may make them more dependent on family members and more vulnerable to abuse" (p. 82).

Some issues particularly pertinent to people resident in rural areas have been highlighted in the research (Tilse et al., 2006; Wainer, Lowndes, Owada, & Darzins, 2010). These include the complexity of assets held by families resident in rural areas such as farming properties; lack of access to services that may assist with asset management arrangements and responses to situation where elder abuse is occurring or expected; and the dynamics involved in reporting or disclosing elder abuse in rural communities, where shame and concern to protect the family name potentially play an inhibiting role. The rural participants in Wainer, Lowndes et al.'s study showed lower levels of confidence in their own ability to recognise whether an elder was experiencing financial abuse. Tilse et al.'s study highlighted the complex and potentially conflictual dynamics around farming properties with the multi-generational interests involved where the farm is the family business. These included complications about the treatment of farms as inheritance, and the balance between providing for children and maintaining the family business, placing one child in a different position from the others, and the treatment of labour and other contributions to the improvement of the farm in estates.

3.5 Dynamics in relation to disclosure and reporting

Complex dynamics and structures are relevant to consideration of the questions of disclosing, discovering and reporting elder abuse if it is disclosed or discovered. This section introduces some the issues raised in the empirical and analytic literature, with reporting obligations and mechanisms discussed more formally in section 6.

Empirical evidence on these issues is very limited in Australia. Elder abuse is generally considered to be remain hidden to a significant extent, and if it is disclosed or discovered, under-reported (Jackson & Hafmeister, 2015; UNDESA, 2013; WHO, 2002b). A range of issues is influential in this context, including difficulties in detecting and identifying elder abuse and the conditions within which it occurs. The same factors that are associated with vulnerability to elder abuse - social isolation and cognitive impairment - also militate against disclosure or discovery and reporting. Where abuse occurs in the context of familial or caregiver relationship dynamics (Jackson & Hafmeister, 2015), this may inhibit a parent disclosing mistreatment by a child and a spouse disclosing mistreatment by a partner. The dynamics of dependence are also relevant, since an aged person may be reluctant to disclose abuse by someone on whom they depend for care, since disclosure may mean withdrawal of the care and potentially an unchosen change in living circumstances. Cognitive impairment may also mean that an older person is unable to disclose or is not believed when they do disclose. Shame, embarrassment, fear of negative repercussions and/or a belief that disclosure and/or reporting may result in no consequences or negative consequences may also be relevant.

The question of reporting obligations in Australia is the subject of significant debate. Apart from limited obligations in relation to specific offences for Commonwealth-funded care facilities (Aged Care Act 1997 (Cth), s 63-1AA), there are no statutory mandatory obligations on professionals to report elder abuse (see section 6.1). Reporting pathways are acknowledged to be complex and confusing both for members of the community and professionals. Duties in relation to reporting depend on the professional context in which elder abuse is discovered. Some analyses have shown that even professionals providing care and other services to elders are unaware of reporting mechanisms (e.g., Miskovski, 2014).

There are a number of different perspectives on the question of whether mandatory reporting obligations should be introduced. One view is that mandatory reporting is paternalistic and detracts from the autonomy of the elder involved. This position is predicated on the view that the elder is in the best position to make a decision about whether abuse should be reported, and derogating from this position reflects an infringement of their human rights, particularly the right to self-determination (EAPU, 2006). Although some organisations and individuals suggest that mandatory reporting might be an appropriate response where elders have diminished capacity, the EAPU asserts that existing obligations arising from professional duty of care requirements already impose sufficient reporting requirements on professionals.

Research suggests mixed views among professionals. The Alzheimers Australia NSW (Miskovski, 2014) study found some support for mandatory reporting of financial abuse among professionals. The study by Mann et al. (2014) on sexual assault and older women also found support among some professionals for mandatory reporting of sexual assault in this context, but this was not a universal view. Mann and colleagues summarised the complex issues that arise in this context in this way:

Such accounts highlight complex ethical, legal, managerial and practical dilemmas and they point to tensions between rights and responsibilities. They also raise issues that extend beyond the residential care sector, suggesting the need for a wider response that encompasses the spectrum of settings in which older women live (p. 53).

A study from the US that interviewed victims and case workers from an adult protective service to examine the dynamics of detection and disclosure showed that relationship factors were an important influence in whether elder abuse was: (a) detected, and (b) reported (Jackson & Hafmeister, 2015). This indicates that where there is a close relationship between the victim and perpetrator, abuse tends to be reported only when it reaches a high threshold of severity. Abuse is more likely to be reported when the victim-offender relationship is not close; for example, when the abuse is being committed by a care worker. The study also found that the relationship between the victim and the person reporting the abuse is relevant, with superficial connections - such as when the reporter is a professional rather than a family member - resulting in reports occurring more readily.

2 See, for example, the EAPU web page on risk factors: <www.eapu.com.au/elder-abuse/risk-factors>.

4. Australia's older population: Demography and health statistics

This part of the discussion focuses on two important aspects of the social, demographic and health backdrop to the issues considered in this paper. It profiles the demographic characteristics of older Australians on the basis of ABS data derived from the 2011 Census (in particular ABS, 2012b, 2013c) and sets out projections in relation to ageing. The discussion also highlights a range of issues, including relationship status, living circumstances, cultural background and disability status that are relevant to a range of considerations in relation to risk factors and response opportunities for elder abuse, as identified in the preceding section. The discussion also uses Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) data to identify the health implications of our ageing population, which again provides insight into the extent of some risk factors and response opportunities for elder abuse.

4.1 Older Australians

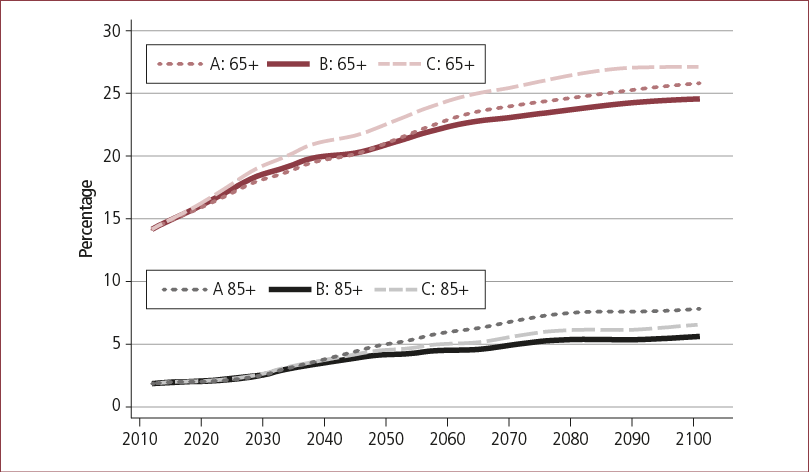

Older Australians have increased significantly as a proportion of the total population, reaching 15% (15% women, 14% men) in June 2014 (ABS, 2015a), compared with 7% in 1941 (n = 3 million). The proportion of people aged 85 years and older tripled between 1971 and 2014, from 0.5% to 2%. Population projections indicate that these trends are set to continue, due to a combination of improved life expectancy and fall in fertility rate since the late 1960s. The ABS has projected that persons aged 65 years and older will account for 20-21% of the Australian population by 2040, and 21-23% by 2050 (Figure 1). The projections indicate that from less than 2% in 2011, persons aged 85 years and older will represent about 4% of the Australian population by 2040, and 4-5% by 2050.

4.2 Relationship status

In terms of relationship status, 73% of men and 63% of women in the 65-69 year age bracket were recorded as being married in the 2011 Census (ABS, 2012b), with this differential broadening in the older age brackets due to the lower life expectancy of men compared to women (80.3 years for men cf. 84.4 years for women in 2014) (ABS, 2015b). The proportions of men and women who reported being widowed peaked in the 90+ age group, at 49% of men and 85% of women. Widowhood was most common for men when they were in the 90+ age bracket, with 49% having this status, whereas for women, 85% in this age group were widowed. Widowhood was common for women in 75-79 year age bracket (40%), compared with just 5% of men.

In the 85-89 year old age bracket, 59% of men were married, compared to 19% of women (ABS, 2012b). The proportion of divorced men in the 65-69 year old age bracket was 13%, compared with 15% of women.

4.3 Cultural background

In the 2011 Census, Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander peoples made up 3% of the population under 64 years, and only 1% in the 65 years and over group (ABS, 2012b).

Australia's older population reflects significant cultural diversity due to post-war immigration policies, with 36% of 65+ year olds having been born overseas (compared to 24% of people under 65 years old) (ABS, 2012b). Among the older immigrants, 25% in 2011 were from non-Anglo countries, compared with 12% from the UK and Ireland. The country of origin with the largest representation of older Australians, after the UK and Ireland, was Italy, followed by Greece. Australia's older population will become increasingly culturally diverse, with weakening dominance of immigrants from European countries. Indeed, while 5% of people aged 65 years and over were from Asian countries in 2011, the proportions were 8% of people aged 50-64 years, and 11% of those aged 35-49 years.

Figure 1: Proportion of projected population aged 65+ years and aged 85+ years, based on three alternative sets of assumptions, 2011-2101

Notes: Series A: total fertility rate = 2.0 births per women from 2026; net overseas migration = 280,000 from 2021; life expectancy = 92.1 and 93.6 for men and women from 2061. Series B: total fertility rate = 1.8 births per women from 2026; net overseas migration = 240,000 from 2021; life expectancy = 85.2 and 88.3 for men and women from 2061. Series C: total fertility rate = 1.6 births per women from 2026; net overseas migration = 200,000 from 2021; life expectancy = 85.2 and 88.3 for men and women from 2061.

Source: ABS (2013b).

4.4 Disability

Increasing increments of older Australians are classified as having a profound or severe disability across the 65+ year age brackets, standing at 9% for 65-69 year olds, and rising to 67% in the 90+ age group according to 2012 Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (ABS, 2013a).

AIHW estimates indicate that 342,800 Australians had dementia in 2015, with this reflecting a rate of one in ten in the 65+ age group, and three in ten for the 85+ age group.3 AIHW projections indicate that the number of people with dementia will grow to 400,000 in 2020 and 900,000 in 2050. More than 50% of permanent residents in Australian Government-funded aged care facilities in 2013-14 had a diagnosis of dementia.

4.5 Where do older Australian live?

In 2011, the two states with the highest concentrations of older Australians were Tasmania and South Australia (16% each; ABS, 2013c), followed by NSW, Victoria, Queensland and WA, which were close to the national average of 14%. The two territories had noticeably lower proportions, especially the Northern Territory, with 6%, reflecting the higher proportion of Aboriginal people in that territory, who typically have a younger age profile than non-Indigenous Australians.

Most older Australians, like most Australians, lived in major urban areas in 2011 (65%; ABS, 2013c). About a quarter of older Australians (23% men and 24% of women) lived in other urban areas (smaller cities and towns). Bounded localities, classified as areas with between 200 and 900 people, were home to 3% of older men and 4% of older women. Of older people, 10% of men and 7% of women lived in rural areas.

For the 65-74 year old age bracket, the most common living arrangement was living in a private dwelling with a spouse or partner, with 67% in these circumstances (74% men and 60% women; ABS, 2013c). In the 75-84 and 85+ age brackets, the gender differential increased, with 46% of men and 11% of women aged 85 years and older living in this situation. A quarter of all older Australians lived alone (32% of women and 17% of men), while 8% lived with other relatives, including their siblings or children.

The higher life expectancy of women is reflected in the patterns in their living circumstances among older men and women. Thirty-two per cent of older women lived alone in 2011, compared to 17% of older men (ABS, 2013c). More older women than men lived with family members other than a partner (65-74: 10% women cf. 4% men; and 85+ years: 15% women cf. 7% men). Most commonly, people in these arrangements were living with one or their children.

Most people aged 65 years and over lived in private dwellings (94%; ABS, 2013c). The most common other living circumstance was non-private dwellings (covering a range of non-self-contained, mostly supported, arrangements). By the age of 85 and older, the proportion of people living in non-private dwellings was 18% (men) and 31% (women), compared with 2% (men) and 1% (women) aged 65-74.

3 See the AIHW's information on dementia: <www.aihw.gov.au/dementia/>.

5. Socio-economic context and intergenerational wealth transfer

The socio-economic characteristics of Australia's ageing population raise some significant issues when considering and developing policy responses to elder abuse. The management of the financial resources and assets of older Australians in particular raises significant challenges. This section considers the socio-economic backdrop to the forms of financial abuse described in section 3, and the likely increase in the coming decades in the numbers of Australians with cognitive decline. It also sets out what is known about attitudes to and the dynamics of inter-generational wealth transfers before and after death, and community practices in relation to will-making, bequests and estate contestation.

As a result of the strong economic conditions that have characterised the baby boom generation's life cycle, the aggregated value of the assets that they hold is significant. Baby boomer wealth profiles are characterised by high levels of home ownership and the rewards of the periods of economic prosperity that have occurred throughout their adult lives. One estimate indicates that the total household wealth that may be subject to transfer by bequest (largely due to high rates of home ownership) may be as high as $70 billion in 2030 (Kelly, Harding, AMP, & NATSEM, 2003), up from $8.8 billion in 2000. In addition to home ownership, the introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee system in 1993 has seen substantial growth in levels of superannuation holdings, which in turn has increased the amount of potentially heritable assets. The 2015 Intergenerational Report: Australia in 2055 predicted that superannuation assets - which stood at $1.84 trillion at the end of 2013-14 - could rise to $9 trillion by 2040 (Treasury, 2015). Depending on how retirement income streams are managed, this may mean that in the future substantial levels of superannuation residues may be transferred to beneficiaries posthumously, given the evidence that some retirees manage fears about outliving their income streams by taking a frugal approach to expenditure (Wu, Asher, Meyricke, & Thorp, 2015).

The implications of the home ownership profile of the now ageing baby boomer generation have been studied by human geographers for some time. Writing in 2001, O'Dwyer noted that:

the transfer of housing wealth which will occur when the baby boom cohorts (currently the inheriting generation) reach the end of their life cycles in 20-30 years time may indeed represent a significant transfer of wealth. We already know that home ownership among this generation is very high and they tended to have fewer children than their parents' generation. Thus the pie of wealth will not only be larger, but will be divided between fewer persons. (p. 96)

The extent to which this prediction eventuates will depend on how the baby boomer generation manages its wealth, the extent to which assets are decumulated prior to death, and the extent to which assets are exhausted in meeting financial and care needs over an extended life span (Olsberg & Winters, 2005). Whether distribution of wealth (housing, investments, retirement income streams and residues) occurs posthumously or not, the socio-economic profile of the baby boomer generation means that the emerging generations of older Australians have much greater levels of assets than those that preceded them.

A further influence arises from the disparities in wealth and access to housing between the baby boomer generation and the generations that follow (Barrett, Cigdem, Whelan, & Wood, 2015; Birrell & McCloskey, 2015). The extent to which, through pre- or post-mortem distribution of assets, this will mean that the intergenerational transfer of wealth will support access to home ownership for the children and grandchildren of the baby boom generation has been the subject of some debate in the academic literature. Uncertainties in this context arise in relation to the attitudes of the older generation, the extent to which they voluntarily preserve or transfer assets for and to their children, and the extent to which assets are not exhausted by the need to meet care and health needs in the face of longer life expectancy (Tomlinson, 2012). The concept of "inheritance impatience" has been developed, meaning: "a situation where family members deliberately or recklessly prematurely acquire their ageing relatives' assets that they believe will, or should, be theirs one day" (Miskovski, 2014, p. 18).

Researchers have highlighted the tensions that arise in relation to wealth preservation or dispersal, the care needs of older generations and the wealth transfer expectations of younger generations (Darzins et al., 2009; Wilson, Tilse, Setterlund, & Rosenman, 2009). This is an area where private interests and public policies intersect in multiple and complex ways, particularly in the context of aged care policies being oriented toward developing a self-funded aged care system, and access to the aged pension being means tested. Wilson et al. analysed the issues raised in this way:

older people's assets can be a site of competing interests. Families have an interest in protecting potential inheritances; the market has interests in promoting lifestyle, care and accommodation options, as well as financial products, such as reverse mortgages; the state is concerned with self-provision and financial independence in older age, and, with service providers, also has an interest in preserving assets to pay user charges for health, care and accommodation in older age. (p. 156)

In this context, generational attitudes and expectations in relation to asset transfers before or after death, and the broader question of attitudes and expectations in relation to mutual or non-mutual intergenerational support in terms of material resources and care, form an important part of the backdrop to the social and economic dynamics that may influence the conditions in which elder abuse occurs. Research based on a sample of 7,000 Australians aged 50 and over reveals a significant amount of complexity in some of these dynamics (Olsberg & Winter, 2005). The authors suggested that the findings showed an erosion in the concept "of a strong and supporting family structure" among the participants, with the emergence of a shift away from "self-sacrifice" to "self-interest" in relation to attitudes to obligations by adult children. In part, this was underpinned by a realisation among participants that their resources would need to remain available to fund their own care and would probably be exhausted by the end of their own lives. But the research also highlighted the prevalence of attitudes negating the observation of continuing obligations to provide financial support for older children, on the basis of a perception that the participants had made enough sacrifices in their children's interests and that the younger generation had "had it all". One third of the sample had already provided support for their children to purchase homes, mostly in the form of an informal loan, often interest free. Particular indications of negative intergenerational dynamics were evident among participants who had experienced relationship breakdowns and re-formations, and there was concern among participants about the implications of these dynamics for potential conflicts over inheritance.

The study by Olsberg and Winter (2005) is one of a very limited number of studies on intentions and actions in relation to pre-mortem transfers of wealth, and the dynamics in this area remain little understood. This is particularly so where such a transfer is part of a "family agreement" in which access to housing, or support to obtain housing, is part of a familial (usually intergenerational) arrangement in which it is exchanged for care and support so that a parent may avoid assisted living or aged care arrangements. These agreements may have various degrees of formality, but evidence considered by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs on Older People and the Law (2007) raised concern about the lack of specific mechanisms regulating them (para. 4.40). The limited evidence available in relation to such arrangements indicates that some may be disadvantageous to the older adult, such as in circumstances where expectations about care are not fulfilled, but the material part of the agreement is irreversible or would take significant effort to reverse (Miskovski, 2014). The House of Representatives (2007) report concluded that "the potentially disastrous consequences that can be suffered by parties to family agreements due to uncertainty, dispute or abuse warrant some form of regulation, particularly if the use of family agreements increases in the future" (para. 4.40). Case studies presented in various reports, including that published by Miskovski, suggest that, in some cases, family agreements and the exercise of powers under enduring power-of-attorney instruments may provide scope for assets to be stripped out of estates.

The available empirical evidence in relation to the post-mortem transfers of assets demonstrates that most people in the older age groups have wills, and that intestacy (not having a will) is rare. In the 50+ year cohort surveyed by Olsberg and Winter (2005), 96% had a will. A more recent study by Tilse, Wilson, White, Rosenman, and Feeney (2015) also evidences an increased emphasis on will-making from middle age onwards. In their community sample of 2,400 people, having a will became more common than not having a will in the 40-49 age group, with 62% of this sub-sample having a will. Increasing increments of participants in the older age groups had a will, rising to 93% in the 70+ age group. The research by Tilse et al. and another study in the same research program on court judgments in will disputes over a one-year period, shed some light on the dynamics surrounding inheritance and will disputes. The analysis suggests that norms and practices in these areas are shifting in line with some social attitudes. From a socio-legal perspective, the context for this has been shifts in some Australian jurisdictions that have weakened longstanding principles in support of testamentary freedom in favour of strengthened recognition of obligations to provide for dependents. In some areas the class of person who may claim entitlement to provision from an estate has also widened (Tilse et al., 2015; White et al., 2015). Consistent with the findings of Olsberg and Winter (2015), Tilse et al. found that participants were not necessarily preserving wealth to ensure a substantial inheritance. Providing for dependents while alive, as well as living comfortably in old age and retirement were seen as just as important. The most common approaches to bequests were providing for spouses and distributing estates equally among children (consistent with Baker & Gilding, 2011). The study indicates that pre-mortem material support for adult children, where the same values in relation to the equal treatment of children in relation to pre-mortem wealth transfers were not evident, is not interconnected to any great extent with approaches to bequests in wills.

The study by White et al. (2015) analysed 195 judgments from 2011 (sourced from AustLII) in relation to disputes over wills, and sheds light on some of the dynamics underlying situations where wills, and the arrangement made in them, are disputed. The analysis showed that the most common class of cases in the sample reflected circumstances where a person with eligibility under the relevant state legislation was seeking to gain or increase a share of the estate (family provision claims, 99 cases). Where the contests involved a partner of the deceased person, 17 (out of 27) involved challenges to provisions made for children of a previous relationship of the deceased, and only one involved a case against the current partner's own child. Where claims were being made by children (73 cases), they most commonly reflected a contest between siblings (43 cases), but challenges by children against provisions made for partners were not uncommon (20 cases). In considering the contests involving siblings, the published account of the research does not shed light on the circumstances that underlie such disputes. In terms of the issues considered in this section, the study findings indicated, consistent with the concerns expressed by the participants in Olsberg and Winter's (2005) sample, that family re-formation is associated with disputes over wills, indicating that complex family dynamics continue to be manifested even at this life stage. White et al. observed that disputes between siblings and those between children of a former marriage and subsequent partner of the deceased are the "fiercest" (p. 902). The authors also observed that the study showed that "competent, financially comfortable adult children are making claims" against estates (p. 906), in contrast to the original intention of family provision law to ensure that widows and children of the deceased were not left financially destitute.

In the study by White et al. (2015), validity was the legal ground most likely to indicate circumstances where elder abuse may have occurred. In the study, two distinct legal categories were grouped together under this heading: circumstances where it was claimed the will-maker did not have the capacity to make the will; and undue influence, where it is claimed that the will is the result of the will-maker's intention being overborne. These grounds were raised in 43 out of 195 cases in the sample.

6. Structures, frameworks and organisation

The discussion in this chapter will identify a range of intersecting frameworks and structures that potentially engage with elder abuse across a range of areas, laws and jurisdictions. Following an examination of the Commonwealth legislative and policy frameworks, examples from the range of state and territory frameworks will be considered, prior to an examination of financial systems focusing on measures encouraging financial literacy and protecting against financial abuse. The chapter will conclude with a brief discussion of a range of advice and advocacy services available through non-government organisations and community bodies that facilitate protection against, and response to, the perpetration of elder abuse.

6.1 Commonwealth legislative and policy frameworks

Legislative frameworks

In spite of the “myth of an all-encompassing federal legal and policy dominance in the ageing portfolio" (Lacey, 2014, p. 101), the Commonwealth Parliament has limited sources of power with which to legislate specifically with respect to elderly Australians and aged care. The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (the Constitution) contains the following heads of power which may provide a basis for the Commonwealth to legislate on matters for this population:

- s 51(xxiii): invalid and old-age pensions;

- s 51(xxiiiA): … widows' pensions … pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services …;

- s 51(xiii): banking…;

- s 51(xx): foreign corporations, and trading or financial corporations formed within the limits of the Commonwealth;

- s 51(xiii): banking …;