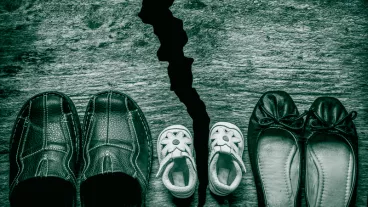

Understanding parenting disputes after separation

Download Research report

Overview

This report explores the behaviour of separated parents by exploring the psychology of post-separation parental disputes and then interrogating three independent data sets to see what further insights they provide on the issues.

The data sets are drawn from:

- the Caring for Children after Parental Separation study (CFCAS; longitudinal Australian data on the dimensions, predictors and outcomes of parent–child contact after parental separation);

- a series of focus groups conducted by AIFS researchers with professionals working in the wider family law system; and

- interviews conducted or supervised by AIFS researchers with individuals who had significant ongoing conflicts and who had volunteered to participate in child-focused mediation.

The CFCAS data suggest that parents who focused on the interests and preferences of their children were able to avoid disputes, and that the higher the level of dysfunction or complexity of the parents’ relationship, the longer it takes to reach a resolution regarding parenting arrangements.

The CFCAS data also indicates that the absence of a reported dispute does not necessarily reflect an amicable or cooperative parental relationship: e.g., absence of contact between parents is one way of avoiding disputes.

The focus groups with family law professionals and interviews with parents point to recognisable patterns of behaviour among significantly conflicted separated parents. The sense of injustice, the extent of the humiliation or trauma resulting from the experience of abuse, or the degree to which communication has broken down will impact on the capacity of separated parents to reach a resolution that works for the children, as well as the capacity of the practitioner to assist in that process. The skill of the practitioner in “difficult cases” will always come down to engaging with the particular issues and dynamics and reflecting them back to the client with empathy and without judgement.

Key messages

-

Even prior to the 2006 reforms, many separated parents were capable of dealing with disputes or potential disputes over children's matters with little evidence of acrimony.

-

The most common way in which parents said they dealt with potential disputes was by focusing on cooperation and by recognising the importance of compromise, flexibility and good communication.

-

A less positive way of avoiding disputes between parents was for the parents to have little or no contact with each other, even though they continued to have a relationship with their children.

-

Assisting a higher proportion of parents to resolve or manage their child-related disputes at an earlier stage after the separation and wherever possible, to move beyond the solution of "parallel parenting" will improve their children's wellbeing

-

A parent's sense of injustice, the extent of humiliation or trauma resulting from an experience of abuse, or the degree to which communication has broken down will impact on the capacity to reach a resolution that works for the children and the capacity of the practitioner to assist in this process.

1. Introduction

Promoting and maintaining child-focused principles during parental separation, against a background of high emotions, is a key challenge for decision makers and family welfare professionals. Despite that, until recently there was little empirical data on how Australian separated parents were relating to each other, as well as data on the link between quality of relationship and the level of disputation over the children.

The seminal study of parenting relationships and arrangements after separation was conducted by Maccoby and Mnookin (1992). These authors found that post-separation relationships and parenting styles could be described according to levels on a spectrum, with “cooperative” at one end and “highly conflicted” at the other. In between, the authors identified a significant group of separated parents who engaged in “parallel parenting”. These parents were more business-like in their approach. They generally refrained from overt criticism but also maintained minimum contact with each other.

The most comprehensive data on how Australian parents manage separation and divorce was published as part of a major evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms (Kaspiew et al., 2009) conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS). A key source of data in this regard came from the Longitudinal Study of Separated Parents (LSSF). Since that time, evidence from two further waves of the LSSF has also been published (Qu & Weston, 2010; Qu, Weston, Moloney, Kaspiew, & Dunstan, 2014).

Following the 2006 family law reforms, various initiatives in Australian family law have, where appropriate to do so,1 aimed to discourage the conflation of adult-focused interpersonal difficulties with the management and resolution of parenting disputes. Initiatives have included: the funding of Family Relationship Centres (Parkinson, 2013); greater collaboration between relationship practitioners and lawyers (Moloney, Kaspiew, Deblaquerie, & De Maio, 2013); and less adversarial processes within courts (Harrison, 2009). These initiatives are consistent with long-standing evidence linking child wellbeing after separation with the level and persistence of parental conflict (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Emery, 2012).

The present report adds to our knowledge of the behaviour and motivations of separated parents by interrogating three independent data sets.

The first, the “Caring for Children after Separation Study”, covered in Chapter 2, collected Australian data on the dimensions, predictors and outcomes of parent–child contact after parental separation.

The second, covered in Chapter 3, reports on family law professionals’ experiences of, and attitudes towards, separated parents.

The third, covered in Chapter 4, presents the results of face-to-face interviews with highly conflicted separated parents who had presented at community mediation centres.

Finally, Chapter 5 contains some concluding observations that link these data sets together and place them in the context of the 2006 family law reforms.

1 We acknowledge the important distinction between interpersonal conflict and entitlement-driven controlling behaviours that are commonly associated with a pattern of violence towards partners and children.

2. Analysis of the Caring for Children after Parental Separation study

The AIFS Caring for Children After Parental Separation (CFCAS) study is a longitudinal survey of separated parents of at least one child aged 18 years or less.4 This chapter reports on three waves of self-report data. The original sample of 971 separated parents was obtained in 2003 through random digit dialling. The samples of men and women are independent. That is, the men and the women had not been in a relationship with each other (i.e., married or cohabitating). The survey sought information on a range of issues, including respondents’ parenting arrangements (including residence, contact and child support), decision-making responsibilities, wellbeing and demographic circumstances. Information regarding residence and contact was gathered in relation to the youngest child of the respondent.

The original sample was stratified by gender and geographical location from the population of Australian households with landline telephones.5 To obtain this sample, more than 163,000 telephone calls were made around Australia, leading to the identification of nearly 70,000 households (43%). Of these households, 77% did not contain a person in scope, while for 15%, the person who answered the telephone refused participation without revealing whether there was a person in scope.

The most favourable response rate (where interviews achieved are calculated as a percentage of interviews plus refusals by a person known to be in scope) is 44%. A more likely estimate, however, is around 26%—assuming that 15% of households where refusal occurred before eligibility could be determined were in scope.6 Most parents agreed to be recontacted at a later date for future research.

A second wave of interviews was conducted early in 2005. Respondents were interviewed for approximately 15 minutes on their attitudes to child support. Attempts were made to recontact the 896 (of the original 971) participants in Wave 1 who agreed to be recontacted at a later date. Of these, 678 were contactable: 92% (n = 623) were interviewed, 4% refused and 4% were away during the survey period.

A third wave of interviews took place in mid-2006. Attempts were made to recontact the 555 (of the original 971) participants in the CFCAS project who agreed to be recontacted at a later date.7 Of these, 438 were contactable, 93% (n = 406) were interviewed, 5% refused, and 2% were away during the survey period.

On average, interviews lasted approximately 20 minutes. Key topics included: relationship support services that they used around the time they separated and that they might consider using again, issues relating to post-separation disputes about parenting arrangements, and services used in resolving such disputes. Information on parenting arrangements was also collected to ascertain change in order to identify different trajectories of patterns of care over time.

Sample characteristics at Waves 1 and 3

This paper makes use of Waves 1 and 3 of the CFCAS project. Sample attrition (or loss of participants between data collection waves) is an issue in longitudinal research; however, this issue is particularly apparent with research involving separated parents, given that their accommodation tends to be more transient than the rest of population. It has been found in other longitudinal studies that individuals who “drop out” of studies tend to differ from those who continue to participate. Specifically, attrition tends to be higher among persons who are relatively young (aged between 15 and 24 years), single, unemployed or working in low-skilled occupations, or have relatively low levels of education.8

Table 2.1 provides a summary of key socio-demographic characteristics of those who participated in both Waves 1 and 3 compared to those who only participated in Wave 1. As can be seen, parents were more likely to have not participated in Wave 3 if they were in rental accommodation, aged less than 35 years old, had a child aged 5 years or less, were receiving government benefits, were unemployed, were in a de facto relationship before separation, had an income of less than $20,000, or had been separated for less than 2 years.

| Wave 1 only ( n = 567) % | Waves 1 & 3 ( n = 404) % | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 44.3 | 44.6 | |

| Dispute regarding contact arrangements reported at Wave 1 | 21.6 | 21.8 | |

| Residence and gender | |||

| Resident mother | 45.3 | 48.0 | |

| Non-resident father | 27.7 | 28.2 | |

| Resident father | 7.9 | 6.7 | |

| Shared-time father | 4.8 | 7.4 | |

| Shared-time mother | 3.5 | 4.2 | |

| Split-residence father | 3.9 | 2.2 | |

| Split-residence mother | 3.5 | 1.7 | |

| Non-resident mother | 3.4 | 1.5 | |

| Geographic location | |||

| City | 58.7 | 60.9 | |

| Country | 41.3 | 39.1 | |

| Education | |||

| Secondary only | 53.0 | 45.9 | |

| Diploma/vocational | 29.6 | 33.8 | |

| Degree | 17.3 | 20.3 | |

| Housing tenure | *** | ||

| Purchasing | 27.7 | 42.8 | |

| Renting | 54.2 | 37.4 | |

| Own outright | 9.5 | 14.4 | |

| Other | 8.5 | 5.4 | |

| Labour force status | ** | ||

| Part-time | 20.8 | 27.0 | |

| Full-time | 40.9 | 42.7 | |

| Unemployed | 12.3 | 7.1 | |

| Not in labour force | 26.0 | 23.2 | |

| Personal income ($’000s) | ** | ||

| < 20 | 37.9 | 32.2 | |

| 20–49 | 45.9 | 42.0 | |

| 50–79 | 11.0 | 21.3 | |

| 80+ | 5.2 | 4.6 | |

| Government benefits | 45.2 | 33.4 | *** |

| Current relationship status | |||

| Remarried | 13.1 | 17.7 | |

| De facto | 14.1 | 16.2 | |

| Single | 72.8 | 66.1 | |

| Relationship status of former partner | |||

| Re-partnered | 60.5 | 66.7 | |

| Age of respondent (yrs) | *** | ||

| 18–34 | 33.7 | 18.1 | |

| 35–39 | 20.5 | 22.3 | |

| 40–44 | 24.4 | 32.0 | |

| 45–54 | 18.7 | 24.8 | |

| 55+ | 2.7 | 2.7 | |

| Relationship status before separation | * | ||

| Married | 69.3 | 76.2 | |

| De facto | 25.4 | 18.8 | |

| Not living together | 5.3 | 5.0 | |

| Distance between parents (km) | |||

| 0–19 | 45.5 | 48.8 | |

| 20–49 | 16.5 | 15.3 | |

| 50–99 | 6.5 | 5.7 | |

| 100–499 | 11.3 | 15.8 | |

| 500+ | 16.8 | 10.6 | |

| Overseas | 3.5 | 3.6 | |

| Age of youngest child (yrs) | *** | ||

| < 5 | 23.3 | 13.1 | |

| 5–11 | 42.0 | 50.5 | |

| 12+ | 34.7 | 36.4 | |

| Time since separation (yrs) | * | ||

| < 2 | 31.3 | 23.9 | |

| 2–5 | 27.7 | 27.4 | |

| 6+ | 40.9 | 48.7 |

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Source: CFCAS Waves 1 and 3

Measures

At Wave 1, experiences of “disputes” were identified from several items. Respondents were asked how the initial decision about their children’s living arrangements was made (court adjudication, between the parents, or “just happened”). Arrangements that resulted from court adjudication were assumed to reflect the occurrence of disputes in the initial process of determining parenting arrangements. Respondents were also asked whether the initial arrangement was still in place. If it was not, they were asked how current arrangements had been decided. A court-adjudicated revision of an initial arrangement was interpreted as reflecting a dispute concerning an existing parenting arrangement. It was therefore possible to distinguish between disputes that resulted from the breakdown of an existing arrangement and those that took place when arrangements were first being determined.

Many parents who have post-separation disputes over their children do not use formal legal processes to resolve their disagreements. Therefore, those respondents who indicated that their initial and current arrangements were determined through means other than court adjudication were asked whether they had experienced a dispute about their children’s living arrangements and/or time spent with the child. It should be noted that if parents indicated that they had had a dispute, it is possible that such a dispute might have resulted in legal proceeding and adjudication without affecting living arrangements. Parents were not asked if they had had a dispute in cases in which there had been no contact between the non-resident parent and the child for the past 12 months (n = 180), or in cases in which a decision about parenting had not been finalised (n = 11). Because those without contact were not asked about this, all of the analyses of Wave 1 data were based on those cases in which both parents were involved with the child(ren) (n = 791).

In Wave 3, respondents were again asked whether they had ever had a dispute about their children’s living arrangements or time spent with the child. Additional information concerning the dispute was also sought, including how long ago the dispute occurred, and if they had sought professional help to resolve the dispute. Respondents were also asked to provide a short answer to an open-ended question on the nature of the dispute. If respondents did not report a dispute they were asked to provide a short answer about how they avoided a dispute.

A list of areas that may contribute to disagreements about parent–child contact after separation was provided to all respondents irrespective of whether they reported a dispute since separation. Parents were asked whether each listed item had lead to a disagreement with their ex-partner. By asking all respondents about disagreements, we were able to compare the responses of those who did and did not report disputes to examine whether there are particular types of disagreements that contribute to disputes.

Results

The use of court services to determine parenting arrangements—Wave 1

All parents were asked how the decision about their children’s living arrangements or time spent with their children was initially determined: either imposed by court, made by the parents themselves, or something that “just happened” (i.e., occurred passively and with minimal discussion).

Table 2.2 displays the type of decision-making process for the initial arrangement by residence and gender status of parents. Approximately 10% of parents indicated that their initial arrangements had been determined by court (i.e., that there was a dispute). Most parents indicated that they had made their initial arrangements themselves (more than two-thirds), while one in five indicated that the arrangement “just happened”.

| Respondent’s parental status | n | Arrangements | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determined by court % | Made by parents % | Something that just happened % | Total % | ||

| Resident mother | 343 | 4 | 69 | 27 | 100 |

| Non-resident father | 215 | 14 | 66 | 20 | 100 |

| Resident father | 62 | 18 | 58 | 24 | 100 |

| Non-resident mother | 22 | 14 | 63 | 23 | 100 |

| Shared-time father | 57 | 7 | 86 | 7 | 100 |

| Shared-time mother | 37 | 5 | 81 | 14 | 100 |

| Split-residence father | 28 | 11 | 75 | 14 | 100 |

| Split-residence mother | 26 | 4 | 88 | 8 | 100 |

| Overall | 790 | 9 | 69 | 22 | 100 |

Source: CFCAS Wave 1

It is difficult to interpret differences in the prevalence of court adjudication between different resident arrangements (resident mothers/non-resident fathers, resident fathers/non-resident mothers, shared-time and split arrangements) due to discrepancies between the groups on specific arrangements. For instance, for the most common arrangement, mother residence, non-resident fathers were more likely than resident mothers to indicate that their arrangements were determined by court (14% vs 4%).9 This discrepancy was also the case with split-residence fathers and mothers (11% vs 4%). There was agreement, however, between shared-time mothers and fathers, with 5–7% of these groups reporting a court adjudicated arrangement. Similarly, there was also consistency between resident fathers and non-resident mothers (18%–14%). Thus it seems that father residence arrangements were more likely to arise from court-adjudicated arrangements than shared-care arrangements.

Looking at differences between specific residence-gender groups, resident fathers were the most likely to indicate that their arrangements had been determined by court (18%), followed by non-resident fathers and mothers (14%). A relatively high proportion of split-residence fathers also reported court adjudicated arrangements. Fewer shared-time mothers and fathers, resident and split-resident mothers reported court adjudicated arrangements. Fathers overall were significantly more likely than mothers to report that arrangements had been determined by court.10 These differences will be discussed in further detail in a later section.

Those who had been separated for longer than 12 months were asked if their initial arrangement was still in place. If initial arrangements were no longer in place, parents were asked how their existing arrangements were determined. A court-adjudicated revision of arrangements was interpreted as reflecting a dispute concerning an existing arrangement. As can be seen in Table 2.3, three-quarters of respondents indicated that the initial arrangement was still in place. There is a significant difference between the type of process used to determine initial arrangements in the likelihood of revision. Specifically, those whose arrangements were determined by court were more likely than those whose arrangements were determined by other means to report that their initial arrangements were no longer in place (38% vs 23–24% in the other groups).11 This difference remained significant after accounting for time since separation.

Table 2.3 also shows that just fewer than 10% of parents who had been separated for more than 12 months reported court-adjudicated revision of arrangements. A similar proportion indicated that their current arrangements were made by themselves (12%), while considerably fewer parents reported that the arrangement just happened (4%). Similar proportions of those whose initial arrangements were determined by court or something that just happened reported that their current arrangement was court-adjudicated (14–16%). Fewer parents who actively made their own arrangements suggested that their current arrangements were court-adjudicated (6%).

| Initial | n | Decision-making process of current arrangement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrangements determined by court % | Made by parents % | Something that just happened % | Initial agreement still in place % | Total % | ||

| Arrangements determined by court | 63 | 16 | 16 | 6 | 62 | 100 |

| Made by parents | 466 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 77 | 100 |

| Something that just happened | 163 | 14 | 7 | 3 | 76 | 100 |

| Overall | 692 | 9 | 12 | 4 | 75 | 100 |

Note: Those who had been separated for less than 12 months were not asked if their initial arrangement was still in place.

Source: CFCAS Wave 1

Table 2.4 shows the decision-making process of current arrangements only for parents separated for more than 12 months who indicated that their initial arrangement was no longer in place. About one-third of parents who reported that their initial arrangements were no longer in place reported that the new arrangements had been determined by court. This is much higher than the proportion of parents whose initial arrangements were determined in court (9%, see Table 2.3). This indicates that if the initial arrangement had been revised, parents were more likely to have used the court to determine the revised arrangements than to determine their initial arrangements. Interestingly, if those whose initial arrangements were court-adjudicated had revised their arrangements, they were more likely to have revised arrangements without going to court. Specifically, approximately 60% of the parents who reported that their initial arrangement had been made in court revised their arrangements without going to court. In contrast, most parents (56%) whose initial arrangements “just happened”, and who revised their arrangements, reported that their current arrangement was court-adjudicated.

| Initial | n | Decision-making process of current arrangement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrangements determined by court % | Made by parents % | Something that just happened % | Total % | ||

| Arrangements determined by court | 24 | 42 | 42 | 17 | 100 |

| Made by parents | 108 | 25 | 56 | 19 | 100 |

| Something that just happened | 39 | 56 | 31 | 13 | 100 |

| Overall | 171 | 35 | 47 | 18 | 100 |

Note: Those who had been separated for less than 12 months were not asked if their initial arrangement was still in place.

Source: CFCAS Wave 1. Percentages may not total exactly 100% due to rounding.

Table 2.5 presents the relationship between the decision-making processes of initial and revised/current arrangements for parents who had been separated for 12 months or more, by residence and gender status of parents. As can been seen, resident mothers and non-resident fathers in particular were most likely to report that contact arrangements were still in place (83% and 76% respectively), followed by shared-time fathers and mothers (74% and 73% respectively). The proportions of other groups that reported that their initial arrangements were still in place were lower.

| Initial | n | Decision-making process of current arrangement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial agreement no longer in place % | Initial agreement still in place % | Total % | ||

| Resident mother | 299 | 17 | 83 | 100 |

| Non-resident father | 194 | 24 | 76 | 100 |

| Resident father | 57 | 35 | 65 | 100 |

| Non-resident mother | 19 | 58 | 42 | 100 |

| Shared-time father | 50 | 26 | 74 | 100 |

| Shared-time mother | 26 | 27 | 73 | 100 |

| Split-residence father | 25 | 52 | 48 | 100 |

| Split-residence mother | 21 | 48 | 52 | 100 |

| Overall | 691 | 25 | 75 | 100 |

Note: Those who had been separated less than 12 months were not asked if their initial arrangement was still in place.

Source: CFCAS Wave 1

It should be noted that more recent data (Smyth, Weston, Moloney, Richardson, & Temple, 2008) suggest that shared parenting arrangements are likely to be the least stable. This reinforces a view that the “shared time” numbers in these data are too small to permit any statements about the stability of these arrangements.

Table 2.6 displays the proportion of parents who reported that either their initial or revised (current) arrangement had been determined in court. This table indicates the prevalence of disputes that resulted in a court-adjudicated arrangement among the sample of parents. Overall, 15% of parents indicated that they had had disputes that resulted in a court-adjudicated arrangement. Non-resident fathers were almost three times as likely to report their parenting arrangements had been determined by the court than resident mothers (23% vs 8%). Of course differential reporting by mothers and fathers, and different types of sample bias among independent groups of separated mothers and fathers are not uncommon in family law research.

| Respondent’s parental status | n | Initial or current parenting arrangements determined by court % |

|---|---|---|

| Resident mother | 343 | 8 |

| Non-resident father | 215 | 23 |

| Resident father | 62 | 24 |

| Non-resident mother | 21 | 24 |

| Shared-time father | 57 | 12 |

| Shared-time mother | 37 | 11 |

| Split-residence father | 28 | 21 |

| Split-residence mother | 26 | 12 |

| Overall | 789 | 15 |

Note: Those who had been separated less than 12 months were not asked if their initial arrangement was still in place.

Source: CFCAS Wave 1

Disputes about parenting arrangements that did not result in a court-adjudicated arrangement—Wave 1 (2003)

As noted, many parents who have disputes do not use the legal system to resolve their disagreements. Therefore, those respondents who indicated that their initial and current arrangements were determined through means other than court adjudication were asked whether they had experienced a dispute about their children’s living arrangements and/or time spent with their children. As shown in Table 2.7, 22% of respondents who indicated that their initial and current arrangements were not legally adjudicated reported that there had been major disputes about their children’s living arrangements.

| Respondent’s parental status | n | Dispute % |

|---|---|---|

| Resident mother | 315 | 20 |

| Non-resident father | 162 | 22 |

| Resident father | 47 | 30 |

| Non-resident mother | 14 | (14) |

| Shared-time father | 50 | 20 |

| Shared-time mother | 32 | 19 |

| Split-residence father | 22 | 41 |

| Split-residence mother | 23 | 22 |

| Overall | 665 | 22 |

Note: Those who had been separated for less than 12 months were not asked if their initial arrangement was still in place.

Source: CFCAS Wave 1

The prevalence of such disputes was similar across the different resident-gender groups, with the exception of the relatively high proportion of split-resident and resident fathers who reported a dispute (41% and 30% respectively). (The size of the non-resident mothers group is insufficient to make valid inferences.) Interestingly, shared-time arrangements are commonly viewed to be associated with a less conflicted post-separation relationship; however, the proportions of shared-time mothers and fathers who reported a dispute were similar to resident mothers and non-resident fathers.

Overall prevalence of disputes—Wave 1 (2003)

The proportion of parents who reported that initial or revised (current) arrangements had been determined in court or that they had had a dispute about their children’s living arrangements provides an estimate of the prevalence of disputes among parents. One-third of parents reported that they had experienced a dispute or that their arrangements had been adjudicated by the court (Table 2.8).

| Respondent’s parental status | N | Dispute or initial or current arrangements determined by court % |

|---|---|---|

| Resident mother | 341 | 26 |

| Non-resident father | 212 | 41 |

| Resident father | 62 | 47 |

| Non-resident mother | 19 | 37 |

| Shared-time father | 57 | 30 |

| Shared-time mother | 36 | 28 |

| Split-residence father | 28 | 54 |

| Split-residence mother | 26 | 31 |

| Overall | 781 | 33 |

Source: CFCAS Wave 1

Again, it is very difficult to interpret the differences between different residence arrangements. Chiefly this relates to differences in the prevalence between gender-residence groups that represent specific arrangements (e.g., non-resident fathers vs resident mothers).

Looking at specific residence/gender groups, fathers were more likely than mothers to report a dispute or court adjudication. Specifically, non-resident fathers were more likely than resident mothers (41% vs 26%), and split-residence and resident fathers were most likely to report a dispute or court adjudication (54% and 47% respectively). Resident and shared-time mothers were least likely to report a dispute or court adjudication (26% and 28% respectively).

Summary

- Approximately 10% of parents indicated that their initial arrangements had been determined by court (i.e., there had been a dispute in deciding initial arrangements).

- Parents whose initial arrangements were determined by court were more likely than those whose arrangements were determined by other means to report that their initial arrangements were no longer in place (38% vs 23–24% in the other groups). This difference remained significant after accounting for time since separation.

- Overall, approximately one-third of parents who reported that they had revised their initial arrangements also reported that their current revised arrangements had been determined by court. This suggests that court-adjudication may be more likely if the dispute arises when arrangements are already in place, compared to those that arise in deciding the initial arrangement.

- The overall prevalence of disputes that resulted in a court-adjudicated arrangement (either in deciding initial arrangements or revising arrangements) among the sample of parents was 15%.

- Another 18% of parents indicated that there had been major disputes about children’s living arrangements that did not result in a court-adjudicated arrangement.

- The overall prevalence of disputes (i.e., dispute or court-adjudicated arrangement) was 33%.

- It is difficult to interpret differences in the prevalence of court adjudication between different resident arrangements (resident mothers/non-resident fathers, resident fathers/non-resident mothers, shared-time and split arrangements) due to discrepancies between the groups making up specific arrangements. Generally, father groups were more likely than the corresponding mother groups to report a dispute. For instance, for the most common arrangement, mother residence, non-resident fathers were more likely than resident mothers to report a dispute or that the initial or current arrangement had been determined by court (41% vs 26%).

Differences between residence/gender groups in the prevalence of disputes—Wave 1 (2003)

Unfortunately, due to the small size of some groups (e.g., non-resident mothers), residence status and gender are very highly correlated. Therefore, a statistical examination of whether gender (i.e., male vs female) or residence status (i.e., residence vs non-residence vs shared care) has the strongest influence on the likelihood of reporting a court-adjudicated arrangement or a major dispute is difficult due to the increased likelihood of error. In particular, it is difficult to ascertain whether non-resident fathers are more likely than resident mother groups to report a dispute because they are male or because they are a non-resident parent.

If gender were not an issue, however, one would expect that the prevalence of disputes among father and mother groups making up specific resident arrangements should be similar. For this reason, it is useful to speculate on possible reasons for the differences between these groups.

It may be that differences reflect the subjective nature of a “dispute” and of situations that lead to a dispute. For instance, many men in dispute may feel that they have been left out of parenting of the child. It may also be that there are differences in the characteristics of mothers and fathers that explain differences in the prevalence of disputes. For instance, fathers in the sample may have been separated for a greater amount of time than mothers, or may be more likely to have re-partnered, or may be of a lower socio-economic status.

Given this, the next section, which examines the characteristics of those who report disputes, will also try to elucidate differences in the prevalence of disputes between mothers and fathers in the most common type of residence arrangement: mother residence (that is, the higher prevalence of disputes reported by non-resident fathers compared with resident mothers). It will first examine characteristics that are significantly associated with the reporting of a dispute or use of court to determine initial or current arrangements among the whole sample. It will also examine the relationship between characteristics and disputes separately for non-resident fathers and resident mothers, to see if there are differences in the characteristics associated with disputes between the groups. Finally, characteristics that are significantly associated with the reporting of a dispute among the whole sample and on which there are significant differences between resident mothers and non-resident fathers will be statistically analysed to determine if such characteristics might explain the differences between these groups in the prevalence of reporting disputes.

Characteristics of those who have had disputes or used court to determine initial or current arrangements—Wave 1 (2003)

In order to examine whether those who experience a dispute or use a court to determine initial or current arrangements differ from those who do not experience a dispute, characteristics were selected from several areas that have been found to be associated with disputes. The areas are demographic characteristics, co-parental relationship, parent–child relationship (pre- and post-separation), and time spent with the child by the non-resident parent.12 Table 2.9 displays differences between those who did and did not report a dispute in variables selected from these areas. The analysis was taken separately for resident mothers and non-resident fathers.

| Resident mothers | Non-resident fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispute n = 88 % | No dispute > n = 253 % | p | Dispute n = 86 % | No dispute n = 126 % | p | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Education | * | |||||

| Secondary only | 49 | 54 | 48 | 49 | ||

| Diploma/vocational | 31 | 26 | 42 | 29 | ||

| Degree | 20 | 21 | 9 | 22 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Housing tenure | ||||||

| Purchasing | 38 | 36 | 42 | 33 | ||

| Renting | 48 | 49 | 36 | 42 | ||

| Own outright | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | ||

| Other | 3 | 4 | 11 | 15 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Labour force status | ||||||

| Part-time | 35 | 32 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Full-time | 29 | 20 | 70 | 77 | ||

| Unemployed | 14 | 14 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Not in labour force | 22 | 34 | 14 | 10 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Personal income ($A) | ||||||

| < 20 | 37 | 40 | 29 | 20 | ||

| 20–49 | 51 | 48 | 43 | 47 | ||

| 50–79 | 9 | 9 | 25 | 22 | ||

| 80+ | 3 | 3 | 4 | 11 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 101 | 100 | ||

| Receiving government benefits | * | * | ||||

| Yes | 44 | 57 | 23 | 13 | ||

| No | 56 | 43 | 77 | 87 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Age of respondent (yrs) —Mean (SD) | 37.99 (7.60) | 37.49 (7.62) | 41.07 (7.54) | 41.06 (8.65) | ||

| Age of youngest child (yrs) —Mean (SD) | 9.43 (4.36) | 8.19 (4.87) | * | 8.95 (3.80) | 9.24 (4.61) | |

| Time since separation (yrs) —Mean (SD) | 6.45 (4.05) | 5.32 (4.56) | * | 6.58 (4.11) | 5.66 (4.38) | |

| Current relationship status | * | * | ||||

| Remarried | 9 | 12 | 29 | 17 | ||

| De facto | 16 | 7 | 27 | 20 | ||

| Single | 75 | 81 | 44 | 63 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Relationship status of former partner | * | |||||

| Re-partnered | 64 | 55 | 76 | 61 | ||

| Single | 36 | 45 | 24 | 39 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Ex and respondent re-partnered | ** | * | ||||

| Only respondent | 13 | 4 | 11 | 15 | ||

| Only ex | 50 | 39 | 30 | 37 | ||

| Neither | 23 | 41 | 14 | 24 | ||

| Both | 14 | 16 | 45 | 24 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Relationship status before separation | ||||||

| Married | 71 | 72 | 74 | 81 | ||

| Living together | 26 | 22 | 21 | 18 | ||

| Not living together | 3 | 6 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Distance between parent (km) | ** | |||||

| 0–19 | 52 | 48 | 35 | 55 | ||

| 20–49 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 18 | ||

| 50–99 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 10 | ||

| 100–499 | 12 | 12 | 16 | 11 | ||

| 500+ | 12 | 14 | 21 | 6 | ||

| Overseas | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Co-parental relationship | ||||||

| Conflict with former partner | *** | *** | ||||

| Great deal | 65 | 16 | 66 | 8 | ||

| Some | 24 | 37 | 23 | 38 | ||

| Very little-none | 11 | 47 | 11 | 54 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Fear for safety in relation to former partner | *** | ** | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 14 | 16 | 4 | ||

| No | 68 | 86 | 84 | 96 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Former partner has accepted the end of relationship | * | ** | ||||

| Yes | 57 | 73 | 64 | 84 | ||

| No | 43 | 27 | 36 | 16 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Relationship between child and parent | ||||||

| Rate former partner as a parent prior to separation | *** | *** | ||||

| Excellent | 1 | 14 | 12 | 27 | ||

| Good | 31 | 30 | 35 | 54 | ||

| Adequate | 17 | 25 | 22 | 6 | ||

| Fair | 12 | 15 | 12 | 7 | ||

| Poor | 39 | 16 | 19 | 6 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Current rating of former partner as a parent | * | *** | ||||

| Excellent | 3 | 12 | 10 | 30 | ||

| Good | 28 | 30 | 36 | 45 | ||

| Adequate | 18 | 21 | 26 | 12 | ||

| Fair | 15 | 17 | 9 | 7 | ||

| Poor | 37 | 21 | 20 | 6 | ||

| Total | 101 | 101 | 101 | 100 | ||

| Day-to-day involvement of non-resident parent in parenting prior to separation | ||||||

| Very involved | 11 | 11 | 68 | 55 | ||

| Quite involved | 18 | 31 | 28 | 38 | ||

| Not very involved | 54 | 49 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Not at all involved | 17 | 9 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 101 | 101 | ||

| Current day-to-day involvement of non-resident parent in parenting | *** | |||||

| Very involved | 0 | 6 | 15 | 17 | ||

| Quite involved | 18 | 14 | 15 | 35 | ||

| Not very involved | 33 | 42 | 35 | 41 | ||

| Not at all involved | 49 | 38 | 35 | 7 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Concerns about abuse or neglect of child in relation to former partner | *** | *** | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 2 | 26 | 5 | ||

| No | 85 | 98 | 74 | 95 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Time that non-resident parent spent with the child | ||||||

| Frequency of time spent with child | *** | |||||

| At least weekly | 26 | 35 | 15 | 51 | ||

| Fortnightly–monthly | 43 | 34 | 58 | 37 | ||

| 3–12 months | 31 | 31 | 27 | 12 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Set pattern | ||||||

| Yes | 58 | 51 | 76 | 65 | ||

| No | 42 | 49 | 24 | 35 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Flexibility | *** | |||||

| Very–fairly flexible | 80 | 90 | 40 | 86 | ||

| Neither | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Very–fairly inflexible | 16 | 8 | 59 | 12 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Would like to change residence | *** | |||||

| Yes | 3 | 3 | 73 | 36 | ||

| No | 97 | 97 | 27 | 64 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Written log of overnights stays | ** | |||||

| Yes | 22 | 9 | 17 | 11 | ||

| No | 78 | 91 | 83 | 89 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Satisfaction with contact | *** | |||||

| Satisfied | 55 | 58 | 13 | 57 | ||

| Neither | 7 | 8 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Dissatisfied | 38 | 34 | 85 | 37 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Non-resident parent not showed for contact | * | |||||

| Very–fairly often | 21 | 10 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Sometimes | 15 | 16 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Rarely–never | 65 | 74 | 99 | 100 | ||

| Total | 101 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Child has not wanted contact | ** | |||||

| Very–fairly often | 27 | 11 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sometimes | 27 | 20 | 9 | 5 | ||

| Rarely–never | 46 | 68 | 90 | 95 | ||

| Total | 100 | 99 | 100 | 101 | ||

| Resident parent has prevented a visit | * | *** | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 14 | 77 | 22 | ||

| No | 73 | 86 | 23 | 78 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Source: CFCAS Wave 1

Overall, parents who reported a dispute were similar in demographic characteristics to those who did not report any disputes. Nevertheless, non-resident fathers who reported a dispute were significantly more likely to hold a diploma or vocational qualification and less likely to have completed a tertiary degree compared with those fathers without dispute. Among resident mothers, those who reported a dispute had been separated for longer and had older children than those who did not report a dispute.

Non-resident fathers who reported a dispute were also significantly more likely than other non-resident fathers to report that their former spouse had re-partnered, to live further away from their former partner and their child, and to report that time spent with the child was on a fortnightly–monthly or infrequent basis (every 3–12 months) rather than on a more frequent basis (at least weekly). Non-resident fathers who reported a dispute were more likely than their counterparts without dispute to report that their contact arrangements were inflexible, that the resident mother had prevented a visit, that they were not satisfied with the level of contact, and that they would like to change their child’s residence arrangements.

Resident mothers who reported a dispute were also more likely than other resident mothers to have kept a written log of overnight stays, to report that the non-resident father had not showed up for contact, and report that the child had not wanted contact.

Not surprisingly, there were strong differences on variables associated with the post-separation co-parental relationship. For both resident mothers and non-resident fathers, compared to the no-dispute parents, those who reported a dispute reported significantly more conflict since separation, to be in fear of their safety in relation to their former partner, and to have concerns about abuse or neglect of their children.

The groups also differed to a considerable extent in their perception of the relationship between their former partner and their child, and the parenting ability of their former partner. Specifically, compared to the no-dispute group, the dispute group was significantly more likely to rate their former partners’ parenting prior to and after separation as “fair” or “poor” and report the non-resident parent as less involved in post-separation parenting, but not prior to separation (non-resident and male shared-time parents reported on their own relationship with the child). These differences were apparent for both resident mothers and non-resident fathers.

Summary

- There were few demographic characteristics that differentiated those who did and did not report a dispute.

- For both resident mothers and non-resident fathers, the dispute group were more likely than the non-dispute group to have poor inter-parental relationships and lots of conflict, fear for their safety in relation to their former partner, and concerns about abuse or neglect of their children.

- Among non-resident fathers, characteristics that were associated with the reporting of a dispute seemed to relate to perceptions of being excluded from the post-separation parenting (less time spent with child, inflexibility of contact arrangements, prevention of time with child by the resident mothers) and, accordingly, dissatisfaction with residence and time spent with the child. In contrast, characteristics associated with disputes among resident mothers, but not non-resident fathers, appeared to reflect perceived problems with non-resident fathers’ time spent with children (e.g., non-resident father had not “showed up” for contact and child had not wanted contact).

Disputes and residence—Wave 3 (2006)

Table 2.10 demonstrates that at Wave 3, 24% of respondents reported a major dispute about children’s living and contact arrangements. It is important to note that all of the analyses of Wave 1 data were based on those with contact (n = 791) (i.e., parents who reported that there had been no contact between the non-resident parent and the child in the past 12 months were excluded). In contrast, at Wave 3, the dispute item was asked of all respondents who participated at this wave. It is therefore difficult to compare the proportion that reported a dispute at each of the waves. However, it is notable that the differences between different gender/resident groups are again present, with fathers overall more likely than mothers to report a dispute.

| Respondent’s parental status # | N | Dispute % |

|---|---|---|

| Resident mother | 168 | 17 |

| Non-resident father | 114 | 32 |

| Resident father | 19 | (42) |

| Shared-time father | 17 | (27) |

| Shared-time mother | 6 | (18) |

| Non-resident mother | 11 | (33) |

| Child over 18 years | 63 | (24) |

| Total | 398 | 24 |

Note: # The residence status of 66 parents was not technically determinate. There were 63 parents whose children were 18 years or over. These children are considered to be legally independent and are therefore not covered by the jurisdiction of the family law system. In addition, three parents of children under 18 years reported that their children were living independently.

Source: CFCAS Wave 3

Timing of disputes

On average, respondents reported that the dispute occurred approximately two-and-a-half years ago (M = 2.7, SD = 2.5, Mdn = 2.0). The average length of time between separation and dispute was 7.3 years (SD = 4.0, Mdn = 6.7).

What are disputes about?

Parents who reported a dispute were asked what they thought the dispute was about. Responses were open-ended, allowing for the diversity of themes underlying the disputes to be captured. A short verbatim answer to the question was recorded. Responses were classified according to a “grounded theory” approach by trying to create categories according to themes that emerged from the set of answers. The formation of categories was also informed by research findings regarding triggers of contact disputes after separation.

Occasionally, multiple themes were evident. However, in these cases an attempt was made to deduce the main underlying theme of the dispute. At times there was particular uncertainty regarding the distinction between concerns about parenting time and residence, given that changes in contact may alter the residence status of parents. It was generally unclear if a dispute about the amount of contact also constituted a change to residence. As such, categories regarding residence and contact can be regarded as overlapping. To reduce ambiguity, examples of responses are provided to illustrate respective categories.

Table 2.11 displays the categories that emerged from analysis of responses of those who reported a dispute and the proportion of responses that were classified into each category. The proportions of resident mothers and non-resident fathers’ responses that were classified into each category are also displayed in Table 2.11. It should be noted that the small (unrepresentative) groups limit the extent to which the observations can be generalised, and inferences should be made with caution.

| Response | Reported disputes n = 90 % | Res. mothers n = 27 % | Non-res. fathers n = 33 % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement breakdown | |||

| Resident parent prevented contact | 17 | 11 | 24 |

| Changeover logistics | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| Non-resident parent not returning child after seeing child | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Sub-total | (21) | (22) | (24) |

| Where the child lives—parent’s wishes | 16 | 11 | 9 |

| Violence or child safety | 14 | 22 | 6 |

| Amount of time spent with child | 9 | 7 | 15 |

| Parenting | 9 | 16 | 6 |

| Child wishes | |||

| Change residence | 8 | 4 | 9 |

| No contact | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Sub-total | (9) | (8) | (9) |

| Relocation | |||

| Resident parent’s relocation | 6 | 0 | 12 |

| Non-resident parent’s relocation | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Sub-total | (8) | (4) | (12) |

| Money | |||

| Child support | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Divorce assets | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| FTB | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Sub-total | (8) | (0) | (12) |

| Non-resident wish for no contact | 4 | 11 | 0 |

| Re-partnering | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Note: Percentages may not add up to exactly 100 due to rounding.

Source: CFCAS Wave 3

A common theme that emerged from parents’ responses was the breakdown of an existing contact arrangement. This theme emerged in approximately one-fifth of these responses. Resident mothers and non-resident fathers were equally likely to report such disputes; however, there were differences between these groups on the specific nature of breakdown. Non-resident fathers were more likely than resident mothers to report a dispute involving perceived denial of agreed time with the child (24% vs 11%). For example:

[My former partner] enrolled [child] in a sporting program and along with the travel involved this takes up an entire day of my 48-hour access period. (Non-resident father)

In my court papers I was supposed to see [child] from Friday afternoon to Saturday afternoon each weekend; however, the mother allowed [child] to go to Melbourne during the weekend when he should have been with me. (Non-resident father)

In contrast, resident mothers’ concerns about the breakdown of contact arrangements related to a child not being returned after seeing a parent or the logistics of the changeover (11% vs 0%):

They went away camping and didn’t come back for several days. I feel that the father should have contacted me to let me know what was going on. (Resident mother)

Him wanting the girls to travel on a train to [interstate city] for weekends [is inconvenient]. (Resident mother)

Parents’ wishes to change where the child lived were also commonly cited as the issue of dispute (16%), as typified by this response:

[My former partner] wanted him for more time. At that stage it was 10 nights with me and four nights with [him]; we agreed that we would go 50/50 at year 7. (Resident mother)

Interestingly, another 8% of responses suggested that a dispute arose because the child wished to live with the other parent. Altogether, disagreements concerning the resident arrangement appeared to be the central theme of 24% of disputes (15% of resident mothers and 18% of non-resident fathers).

[The child] was getting annoyed with her mother hassling her and I said she could come to stay with me. (Non-resident father)

My daughter wanted to live with the mother but the mother was reluctant to start with. (Non-resident father)

On the other hand, 9% of responses suggested that the dispute was about one parent wanting to increase the amount of time with the child, seemingly above what was agreed. Non-resident fathers were more likely than resident mothers to report a dispute of this nature (15% vs 7 %).

Just extra access, [he] gave me that day warning and he rang up and wanted her, around Christmas. (Resident mother)

[I want] to have more time to spend with my daughter. (Non-resident father)

Issues relating to violence and child safety were apparent in 14% of responses. A higher proportion of resident mothers than non-resident fathers reported that that the dispute was about violence or the safety of children (23% vs 6%).

The kids had gone on access there for three weeks, he got violent towards one of them and also there was the concern that the girls were in danger of general abuse. (Resident mother)

She was drinking too much and she trashed the house that she was living in. She was arrested for her own safety. That’s when I ended up with all the kids. The dispute was about custody and her drinking. (Shared-time father)

A further 9% of responses suggested that the dispute was about parenting issues such as decisions about the child’s education or parenting behaviours toward the child. A higher proportion of resident mothers than non-resident fathers reported disputes of this type (16% vs 6%).

My daughter is now 16 years old and very street-wise. She lives with her father, she is not going to school a lot, and her father thinks she should stay in school and I think she is ok to be working. (Resident mother)

Some disputes (8%) appeared to be about relocation. Mostly this was about the resident mother wanting to move with the child, which would prevent the non-resident father from seeing the child; however, there were two instances in which the non-resident mother was unhappy because the father’s move prevented him from being able to see the child.

She walked away with the child [and] I don’t know where she is. [She] won’t let me have the child, and took me for all I have and turned the family against me. (Non-resident father)

The fact that he won’t come back and live in Australia and his son is deeply troubled at the moment. (Resident mother)

In another 8% of responses, parents indicated that the dispute was about the intersection of money (child support, family tax benefit and divorce assets) and time with child. A higher proportion of non-resident fathers than resident mothers believed that the dispute was about money (12% vs 0%).

Centrelink said that they would take money from [my former partner] and give it to me because I had custody of [our child]. So [my former partner] changed her mind and then wanted full custody because she wanted the money. She realised she was going to lose money. (Non-resident father)

A very small proportion of responses suggested that disputes were about the non-resident father not wanting contact (4%) or about re-partnering (2%).

Disagreements—Wave 3 (2006)

A list of areas that may contribute to disagreements about parent–child contact after separation was provided to all respondents irrespective of whether they reported a dispute since separation. Parents were asked whether any of these had led to a disagreement with their ex-partner. By asking all respondents about disagreements, we were able to compare the responses of those who did and did not report disputes to examine whether there are particular types of disagreements that might contribute to disputes.

As displayed in Table 2.12, the most common area over which separated parents reported a disagreement was money (including child support), with 61% of parents admitting disagreement in this area. Issues relating to re-partnering, the wishes of a child, and concerns of parenting also quite commonly led to disagreement (approximately 40%). One-quarter of parents reported a disagreement about relocation.

Parents who reported a major dispute were more likely than those who did not to admit disagreement in all areas. These differences were statistically significant, with the exception of disagreements over issues relating to a new partner. The largest differences between those who did and did not report a major dispute were in disagreement over the ability of either parent to care for the children and the relocation of either the respondent or ex-partner. Those who had a dispute reported a significantly greater number of different types of disagreements (M = 2.8, SD = 1.0 vs M = 1.6, SD = 1.3)13 compared to those who had not.

| Area | Total n = 400 % | Reported dispute n = 95 % | Did not report dispute n = 297 % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Money (including child support) | 61 | 78 | 56 |

| Issues relating to a new partner | 40 | 49 | 36 |

| The wishes of one or more of the children | 37 | 58 | 31 |

| Concerns about the ability of either of you to care for the children | 37 | 66 | 28 |

| You or ex-partner moved or wanted to move | 25 | 48 | 17 |

Source: CFCAS Wave 3

Table 2.13 shows the proportion of non-resident fathers and resident mothers who reported disagreements in the particular areas measured. A significantly higher proportion of non-resident fathers than resident mothers reported disagreements over the wishes of one or more of the children (46% vs 33%) and relocation (33% vs 20%). Other differences were not significant.

| Area | Resident mothers n = 165 | Non-resident fathers n = 114 |

|---|---|---|

| Money (including child support) | 67 | 57 |

| Issues relating to a new partner | 40 | 40 |

| The wishes of one or more of the children | 33 | 46 |

| Concerns about the ability of either of you to care for the children | 36 | 38 |

| You or ex-partner moved or wanted to move | 20 | 33 |

Source: CFCAS Wave 3

Summary

The most common themes to emerge from parents’ responses about what their dispute was about related to disagreements about where the child lived (whether this was the parent’s or child’s wish) and the breakdown of existing contact arrangements (typically that the resident parent had denied agreed contact time). Disputes about violence and child safety were also relatively common. Other themes included disputes about increases in the amount of time spent with the child (above what was agreed), parenting issues, relocation (typically of the resident parent), and money. Disputes about the non-resident parent’s wish for no contact and re-partnering issues were relatively uncommon.

There were differences in the responses of resident mothers and non-resident fathers in what they felt the dispute was about. Non-resident fathers were more likely than resident mothers to believe that the dispute was about the resident parent preventing agreed time spent with the child, non-resident fathers’ desire for time with the child above that which had been agreed to, the resident parent’s relocation, and money. In contrast, resident mothers were more likely than non-resident fathers to suggest that the dispute concerned changeover logistics, the child not being returned as agreed, and issues of violence and child safety.

We also compared the proportion of those who did and not report a dispute on their experiences of particular types of “disagreements”, to examine whether there are particular types of disagreements that might contribute to disputes. Parents who reported a major dispute were significantly more likely than those who did not to admit disagreement in all areas, with the exception of disagreements over issues relating to a new partner.

Sources of help used in resolving disputes—Wave 3 (2006)

Parents who reported a major dispute since separation were asked which sources of help they consulted to resolve the dispute. Approximately half (48%) of those who had a dispute sought help for the dispute. The most common source of help was a lawyer, with 74% of those who sought help seeking legal advice. Roughly one-third who sought help reported seeking help from a mediator or a counsellor, and about one-quarter sought help from someone else. Of the individuals who sought help from non-legal dispute services (i.e., mediation or counselling), most also sought help from a lawyer.

| Source of help | Those who reported a dispute n = 95 % | Those who sought help for a dispute n = 46 % |

|---|---|---|

| Lawyer | 36 | 74 |

| Mediator | 15 | 30 |

| Counsellor | 17 | 35 |

| Someone else | 11 | 22 |

| Any help | 48 | NA |

Source: CFCAS Wave 3

Table 2.15 summarises the number of different sources of help that were accessed. Of those who reported getting help, the average number of different sources used was 1.6 (SD = 0.95).

| No. of different sources of help | Those who reported a dispute n = 95 % | Resident mothers n = 28 % | Non-resident fathers n = 36 % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 52 | 49 | 58 |

| 1 | 32 | 29 | 25 |

| 2 | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| 3 | 6 | 14 | 6 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: CFCAS Wave 3

How disputes were avoided

If parents did not report a dispute about parenting arrangements, they were asked how they managed to avoid such a dispute. Again, responses were open-ended and a short verbatim answer to the question was recorded. Similarly, responses were classified according to a “grounded theory” approach by trying to create categories according to themes that emerged from the set of answers.

Table 2.16 displays the categories that emerged from analysis of responses and the proportion of responses that were classified into each category. The proportions of resident mothers and non-resident fathers’ responses that were classified into each category are also displayed.

| Response | Did not report disputes n = 297 % | Resident mothers n = 137 % | Non-resident fathers n = 75 % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental cooperation | |||

| Compromise/communication/flexibility | 27 | 22 | 44 |

| Arrangement suits both parents | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Good parental relationship | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Trust | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Similar views on parenting | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sub-total | 35 | 29 | 53 |

| Child-focused | |||

| Childs interests put first in negotiation | 14 | 13 | 12 |

| Child decides | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Non-resident parent less able to parent | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Sub-total | 27 | 26 | 17 |

| Unilaterally determined arrangements | |||

| Non-resident parent disinterest | 12 | 19 | 0 |

| Resident parent decides/ non-resident parent concedes | 7 | 4 | 12 |

| Non-resident parent has no contact with child | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| Non-resident parent decides/ resident parent concedes | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Sub-total | 25 | 31 | 13 |

| Intervention or other measures | |||

| Parenting court agreement/order | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| No contact between parents | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Threats of legal intervention | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Extended family support or involvement | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Sub-total | 9 | 8 | 13 |

| Distance determines contact | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Unclear or other | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: CFCAS Wave 3

As can be seen, five main themes emerged from the analysis: parental cooperation, a child-focused orientation, unilateral arrangements, intervention and further measures, and distance.

The most common theme that emerged as to how disputes were avoided seemed to reflect some degree of parental cooperation in decisions over residence and time spent with the child. This theme emerged in approximately one-third of responses. Typically such responses suggested that disputes were avoided because of communication, flexibility and compromise in negotiating arrangements. Non-resident fathers tended to cite such reasons more than resident mothers (44 vs 22%). Examples of such responses include:

You listen a bit more and say a bit less. We know what the routine is—if there is something happening we talk to each other and say I’m going to a kid’s birthday party and they might sleep over. Just talk to each other and figure something out. (Shared-time father)

By giving [my former partner] more time, [this] lessened any conflict, and with more compromise and communication, building up trust allowed him to feel that he can make an equal contribution to [child’s] parenting. (Shared-time mother)

Compromise mainly—I never made demands—flexibility and consideration of everything else. We treated it in some ways as if we were still together; communicated about the kids, still got him involved in special days. (Non-resident father)

Some parents suggested that cooperation was achieved specifically because parents shared a good relationship or similar views on parenting, or because the arrangements suited both. For example:

I believe that both of us have worked towards [the arrangement], and we get on fine and we pretty much agree on the arrangements. We talk freely, we support each other in decisions that [we] have made, [we have a] high level of communication. (Non-resident father)

We are like-minded enough on how [our child] is brought up. We have similar views on how she is raised. (Non-resident father)

We came up with our custody agreement. If he wanted to have them for five nights a fortnight, he could, but he just didn’t [want that] and it worked out fine for him and fine for me. It just worked out [that we were] both happy with the arrangement. (Resident mother)

Another major theme in responses seemed to suggest that disputes were avoided because negotiations about parenting arrangements were conducted with children’s interests as the foremost consideration. This theme emerged in approximately one-quarter of responses. For example:

Our daughter is priority for both of us—my partner’s and my feelings come second to [our] daughter’s. (Non-resident father)

When we are angry we are still able to see what is in [our child’s] best interest. I think it’s too disruptive shunting them between homes. [A] 50/50 [arrangement] is not good; sharing half a week each ... can be harmful. (Resident mother)

Responses were also judged to be child-focused if they suggested that the child’s preference was taken into account, or if the child made the decision about the arrangements. Resident mothers tending to cite such reasons more than non-resident fathers.

We just agree I suppose [it’s] just what the kids want. If they wanted to go live with him, they know they can. (Resident mother)

I’ve always said they can ring; they can see him as much as they or he wants. (Resident mother)

Child-focused responses also included responses that indicated that arrangements were not disputed because the non-resident parent was less able to parent the child, for reasons including mental and physical illness, substance use and work commitments.

My former partner wanted to care for [our child] full-time, which suits me as I suffer from panic attacks and my health is not really that good. (Non-resident father)

He has drug and domestic violence convictions against him and he knows he can’t have her full-time. (Resident mother)

When this all happened, I was on my own. There was no way in the world I could have had the kids [be]cause of my work hours, [so there was] no argument about who was going to have the kids. (Non-resident father)

Another one-quarter of parents seemed to suggest that disputes were avoided because one parent determined arrangements without negotiation with the other parent. Usually this reflected a lack or marginalisation of involvement of the non-resident father, either in the care arrangements or negotiations about arrangements. Many responses of this nature included those by resident mothers who suggested that their former partner was disengaged from parenting and so did not care or was uninterested in seeing the child.

It is something that has to be done. He wants limited contact so that’s what has been agreed. [My former partner] dictates whether he wishes to see the children and I abide by that. (Resident mother)

He didn’t want to be involved, [so] it was very easy. (Resident mother)

He’s only wanted limited contact with the children and both of us have agreed to that. (Resident mother)

Other unilateral responses suggested that the non-resident parent did not have contact with the child; however, it was not indicated whether this was by choice.

We just don’t see him, [so] we’ve just not had any disputes. (Resident mother)

Unilateral responses also included those that suggested that one of the parents had been excluded from decisions about arrangements or made concessions during negotiations about arrangements. Generally, this seemed to result in the resident parent being the ultimate decision-maker in arrangements.

[We] had no discussion. Since [the child] has been born I have had no say in the matter at all. (Non-resident father)

[We] haven’t had a chance to [have] disputes. I’ve had no say at all. (Non-resident father)

I just put my foot down and say “no”. (Resident mother)

Some responses suggested that disputes had not occurred because of an intervention or other measures (9%). These responses seemed to reflect more tenuous parental relationships that needed further support to make contact work without dispute. For instance, some parents said the arrangements had not varied from the parenting agreement or court order. Some of these responses suggest that there may have been a dispute at an earlier stage of the separation. In these cases it would appear that the agreement had been instrumental in preventing further disputes. Interestingly, non-resident fathers tended to have these beliefs more than resident mothers.

I don’t ask anything from him over and above the court order. (Resident mother)

We fought about it at the beginning and agreed. We’ve got consent orders and a parenting plan and property divided up, so it’s been all organised since we separated. (Shared-time father)

... The court ordered 50/50 shared care and we have both abided by it. (Shared-care father)

Other measures that were also introduced to prevent disputes occurring in more tenuous parenting arrangements included parents not having any contact with each other,14 or parents involving extended family to reduce any tension.

No communication between us—[it] reduces the chance of conflict. (Resident father)

[We communicate] through his parents. I was at the stage where I wouldn’t talk to him because he was rude, so I went through his mum. (Resident mother)

Finally, some parents suggested that disputes were avoided because the distance between the non-resident parent and child restricted arrangements and presumably claims for different arrangements.

Living in Australia, he can’t say “can I have them [on] the weekend?” because we’re here [and he is not]. If he was here in Australia, we could organise something like that. (Resident mother)

Summary

The most common theme to emerge from parents’ response as to how disputes were avoided related to some degree of parental cooperation. Such responses seemed to indicate the importance of compromise, flexibility and communication in negotiations about arrangements. For some, this was made easy due to the good relationship between them or similar views of parenting; for some, the arrangements just worked for both. A child-focused theme also emerged, in which responses suggested that parents who focused on the interests and preferences of their children were able to avoid disputes.

Themes also emerged that indicated that the absence of a reported dispute does not necessarily reflect an amicable or cooperative parental relationship or mutual satisfaction with the parenting arrangements. For instance, some parents indicated that disputes had not occurred because of a lack or marginalisation of involvement of one parent—typically the non-resident father—either in the care arrangements or negotiations about arrangements. Other responses suggested the arrangements were not disputed because of earlier interventions such as parenting agreements or court orders. Absence of contact between parents was also one way of avoiding disputes.

Differences in the responses of non-resident fathers and resident mothers were evident. Specifically, non-resident fathers were more likely than resident mothers to believe that compromise, flexibility and communication in negotiations were instrumental in avoiding disputes. They also were more likely to indicate that a dispute had not occurred because the resident parent decided arrangements without their involvement. In contrast, resident mothers were more likely to indicate that they had avoided disputes because the arrangements were decided upon by the child, or the non-resident father did not care the outcome, or was uninvolved with the child.

4 This study was developed and managed by Bruce Smyth, with support from Ruth Weston, Catherine Caruana, Anna Ferro and Nick Richardson.

5 Random digit dialling has a number of benefits over other approaches, including the ability to make contact with unlisted numbers. The proportion of unlisted numbers has increased markedly in recent years, adding bias to samples drawn from the electronic telephone databases.

6 Using data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (1998), the fieldwork company estimated that 15% of households contacted would meet the sample selection criteria.

7 In the callback from Wave 2, 123 respondents were not included for a range of reasons, including that the target child had turned 18, respondents declined further contact after Wave 2, etc.

8 See Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey—Annual Report 2006 (2007).

9 c2 (2) = 23.8, p < .001.

10 c2 (2) = 24.3, p < .001

11 c2 (2) = 6.5, p < .05

12 In the case of shared time, this is the male parent.

13 t(390) = 8.95, p < .001

14 Further examination revealed that contact between the non-resident parent and the child had occurred on a fairly frequent basis (i.e., at least once every 3 months), despite there being no contact between parents.

3. Practitioners' experiences of parenting disputes

This chapter draws on qualitative data derived from a series of focus groups conducted by AIFS with professionals working in the wider family law system (including mediators, counsellors, family therapists and family lawyers). This component was designed to provide a different methodological vantage point—the views of professionals—from which to understand post-separation parenting disputes. Focus groups provide a greater opportunity to explore the more complex conceptual and process-oriented issues likely to be at play in disputes about contact.

Participants

Participants were recruited by way of a formal approach: letters were sent to organisations, inviting the participation of professionals who work with families in dispute after separation. Each organisation was provided with an overview of the nature and aims of the project. Participation of individual workers was voluntary and all participants signed consent forms.

Six focus groups with industry professionals were conducted. Each focus group comprised 5–10 members. The composition of focus groups was along professional and organisational lines:

- Four focus groups were conducted with professionals employed in services that provide family dispute resolution services (mostly comprising clinical psychologists, social workers and family therapists).

- One focus group was conducted with family lawyers who engage in publicly funded and private practice.

- One focus group was conducted with staff of the Child Support Agency (CSA)—the government agency that aims to support separated parents in the transfer of payments for the benefit of their children.

The total sample consisted of 48 individuals, of whom 31 were female, which reflects the gendered nature of professions working with families in disputes.

Question guide

A structured group interview guide was used, comprising 12 questions. Questions were developed through an extensive work-shopping process with AIFS researchers. Focus-group interviews typically have a particular logic, where questions are guided by a funnel design. Relatively broad, easy to answer, non-threatening questions are initially asked to promote group cohesion, rapport and trust. As far as practical, the same questions are asked of all of the groups so that points of similarity and disparity can be explored both across and within the groups (Smyth, 2004). By and large, all questions were asked of the group as a whole (rather than of individuals).

Procedure

Focus groups were conducted in May and June 2005 on the premises of the targeted services. They were audio-recorded with the participants' permission, and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Focus-group interviews ran for approximately 90 minutes. Each group had a moderator and a moderator's assistant.