Experiences of Separated Parents Study

October 2015

Rae Kaspiew, Rachel Carson, Jessie Dunstan, John De Maio, Sharnee Moore, Diana Smart, Lixia Qu

Download Research report

Overview

This report compares the experiences of parents who had separated either before or after the 2012 family violence amendment reforms were introduced. It uses findings from the Experiences of Separated Parents Study.

This report presents the findings of a core element of the Evaluation the 2012 Family Violence Amendments project - the Experiences of Separated Parents Study (ESPS). The research, commissioned and funded by the Australian Government's Attorney-General's Department (AGD), is based on a comparison of two nationally representative samples of the Survey of Recently Separated Parents (SRSP): the SRSP 2012 cohort of parents, who had separated between 1 July 2010 and 31 December 2011 (n = 6,119); and the SRSP 2014 cohort of parents, who had separated between 1 July 2012 and 31 December 2013 (n = 6,079). The family violence amendments introduced by the Family Law Legislation Amendment (Family Violence and Other Measures) Act 2011 came substantially into effect on 7 June 2012 and, as such, the SRSP 2012 survey represents parents' pre-reform experience of the family law system, and the SRSP 2014 represents parents' post-reform experience of the system.

The samples for the two surveys were derived from the Department of Human Services - Child Support (DHS-CS) database and substantially replicate the approach applied in the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families (LSSF). The LSSF research program involved a national, longitudinal study of parents who had at least one child under 19 years of age, who separated after the 2006 reforms to the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (FLA), and who were registered with the DHS-CS. Data collection for the LSSF took place in 2008 (Wave 1), 2009 (Wave 2) and 2012 (Wave 3). Together, these studies allow an understanding of the experiences of separated families over a substantial period of time.

The core focus of the SRSP 2012 and 2014 studies were on investigating parents' experiences of family violence and safety concerns (including children's exposure to family violence) and their experiences in disclosing family violence and safety concerns to family law system professionals. The research also explored parents' use of services, patterns in parenting arrangements, child support arrangements and parent and child wellbeing. The data collected informed conclusions about the effect of the 2012 family violence amendments and further developed the evidence base established in the LSSF research program.

Main findings

Family violence and safety concerns

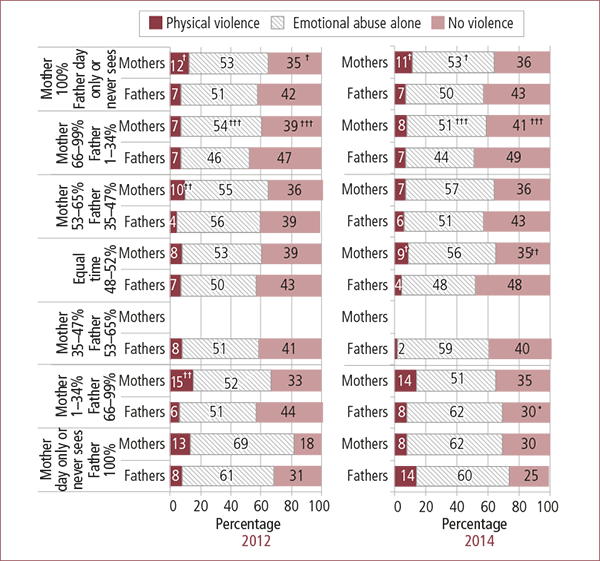

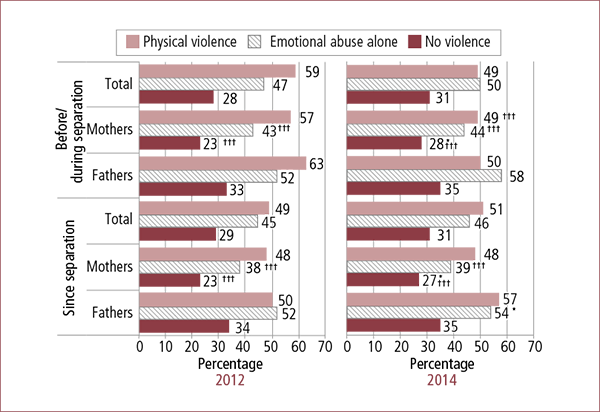

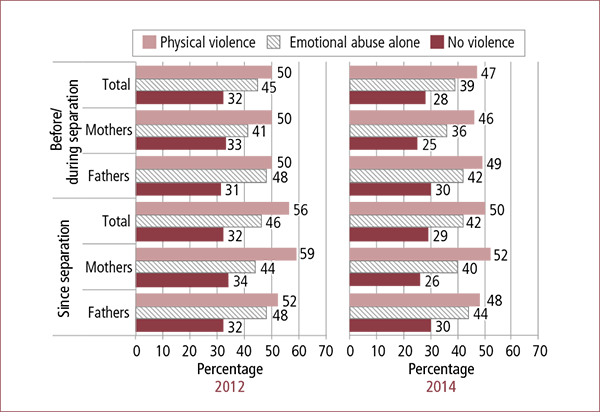

The SRSP 2012 and 2014 data indicate that family violence is a common experience among separated parents, with a majority of participating parents in both cohorts reporting either physical or emotional abuse. Overall, the findings indicate similar profiles in the nature and frequency of family violence and safety concerns in the 2012 and 2014 samples.

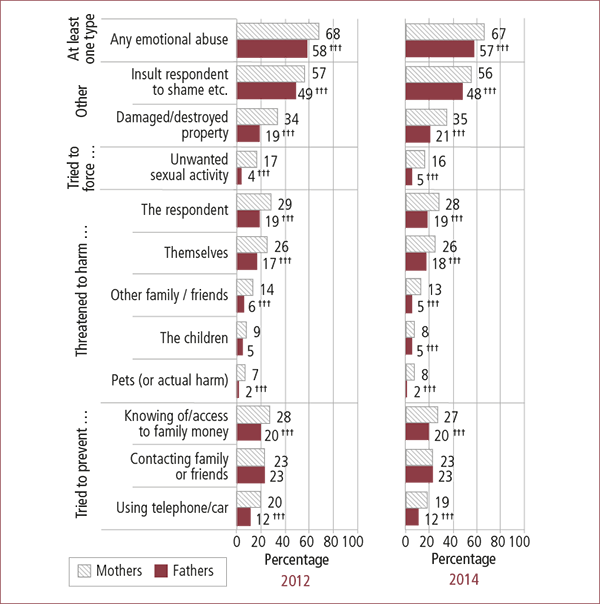

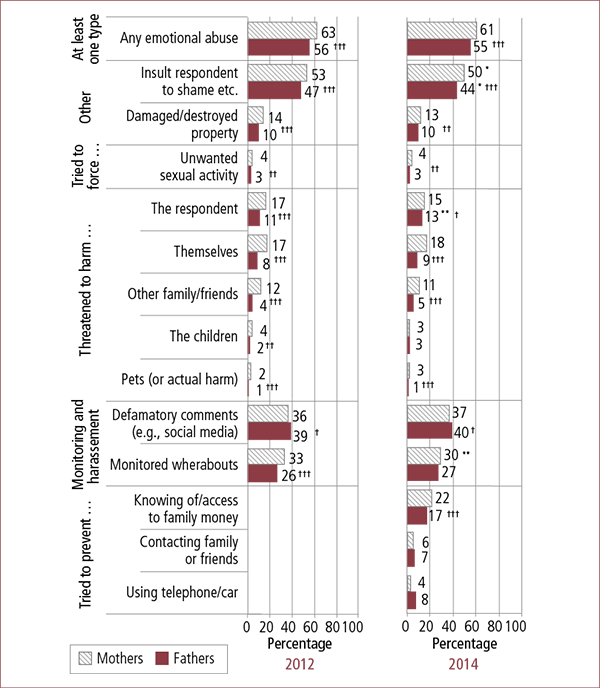

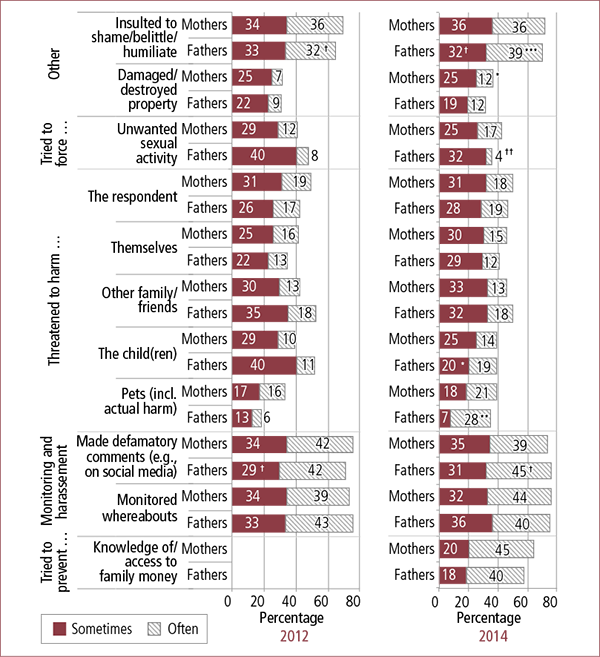

Most parents reported experiencing a least one type of emotional abuse before/during or since separation. Overall, mothers reported experiencing emotional abuse in greater proportions than fathers, both in the before/during separation time period (2012: 68% cf. 58%; 2014: 67% cf. 57%) and in the post-separation period (2012: 63% cf. 56%; 2014: 61% cf. 55%). While there were no statistically significant differences between the 2012 and 2014 cohorts in relation to reports of experiencing emotional abuse before separation, a small but statistically significant decrease in the post-separation time period was reflected in the 2014 cohort's reports of the most commonly reported form of emotional abuse - insults with the intent to shame, belittle or humiliate.

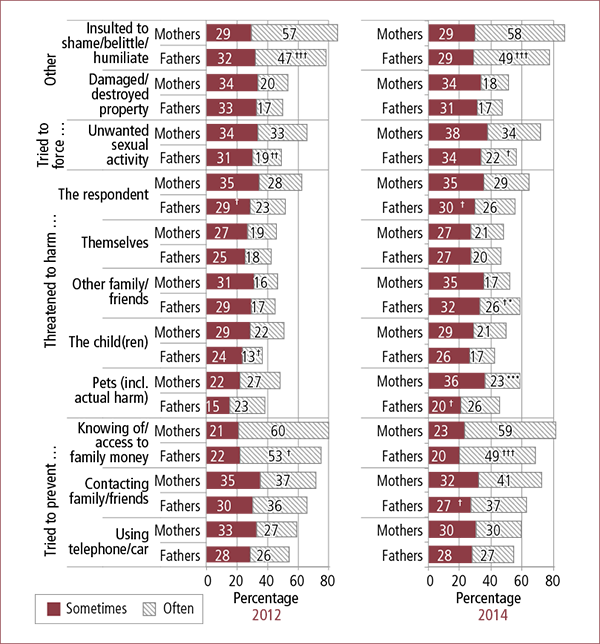

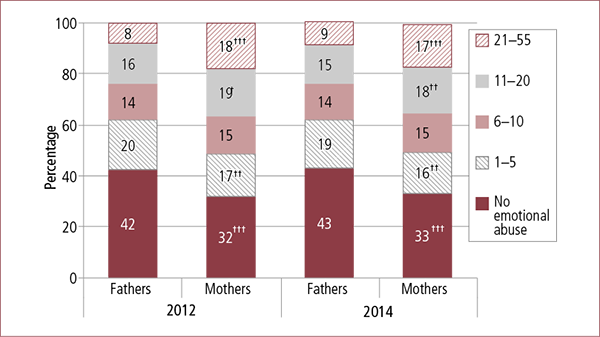

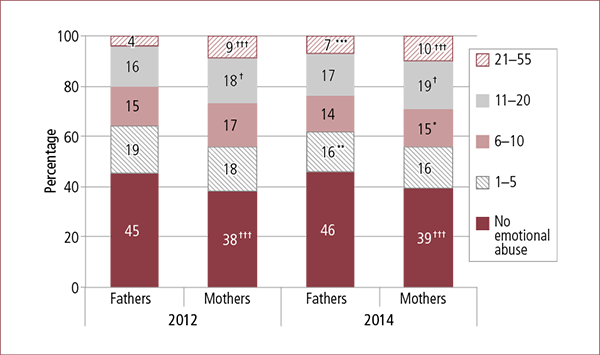

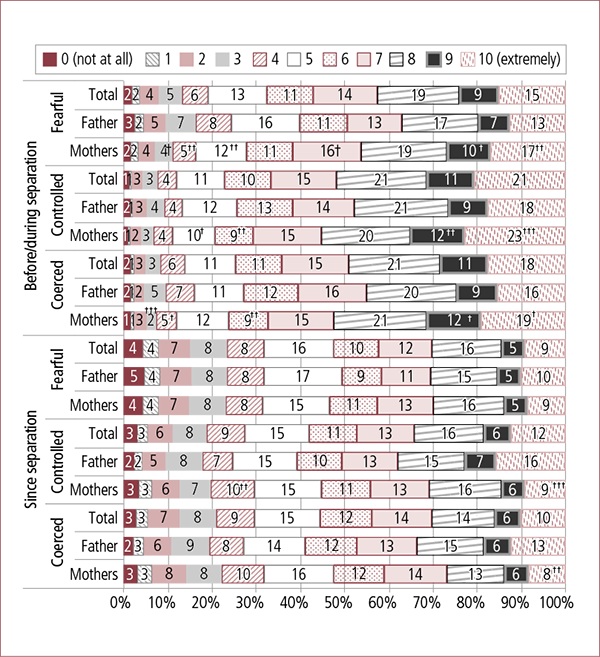

Overall, mothers in both cohorts reported experiencing most of the nominated emotional abuse items more frequently than participating fathers. In relation to the intensity of the emotional abuse experienced, a substantial proportion of parents' reports (and predominantly mothers' reports) in each cohort recorded the highest level of reported intensity, which reflected very frequent experience of at least five emotional abuse items (2012: fathers: 8%, mothers 18%; 2014: fathers: 9%, mothers: 17%).

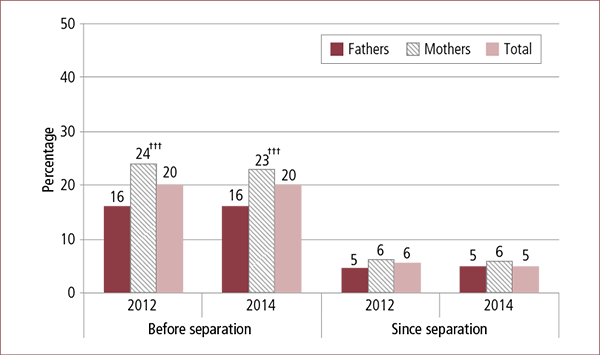

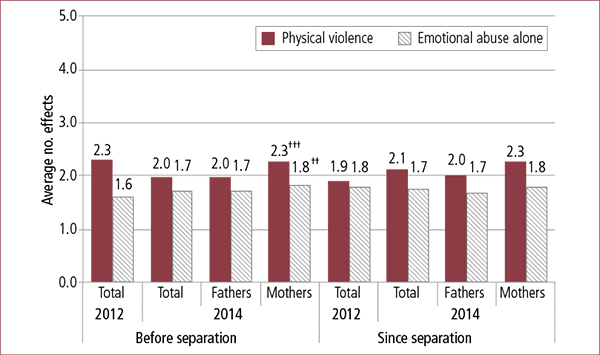

A substantial minority of parents in both the 2012 and 2014 cohorts reported experiencing physical hurt before/during separation (20%), with mothers reporting these experiences in greater proportions than fathers in both cohorts (2012: 24% cf. 16%; 2014: 23% cf. 16%). The reported incidence of physical hurt after separation declined to 5% for fathers and 6% for mothers in the post-separation period for both cohorts. Differences between the 2012 and 2014 cohorts emerged in relation to the effects of physical hurt, with higher post-separation affirmative responses from parents in the 2014 cohort with respect to the categories of "bruises and scratches", "fractured or broken bones", "gunshot, stab wounds or burns" and "other injury".

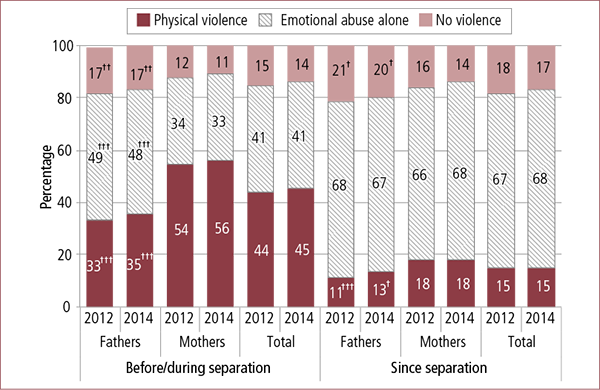

In the context of a generally stable pattern in reports of experiences of three categories of family violence measured in the SRSP (emotional abuse, physical hurt and attempts to force unwanted sexual activity), some areas of difference were evident between mothers and fathers. That is, a higher proportion of mothers than fathers reported experiencing each type of violence measured, while a higher proportion of fathers reported that they had not experienced any of the three violent and abusive behaviours before/during separation in either cohort (2012: 41%; 2014: 42%) compared with mothers' reported experiences (2012: 31%; 2014: 32%).

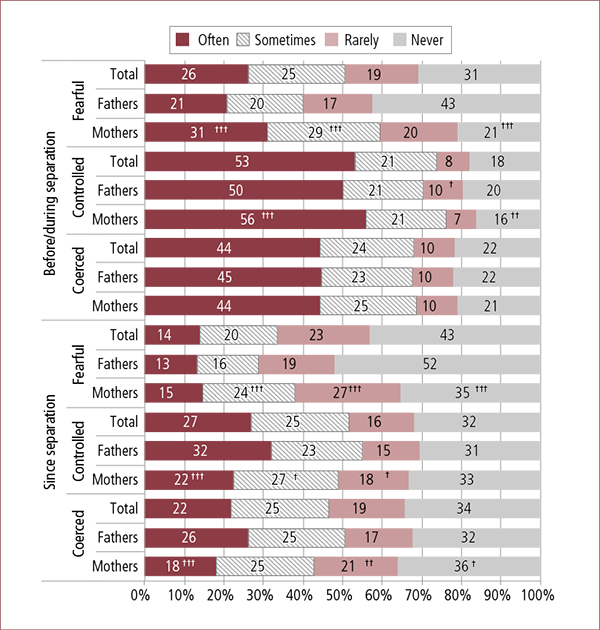

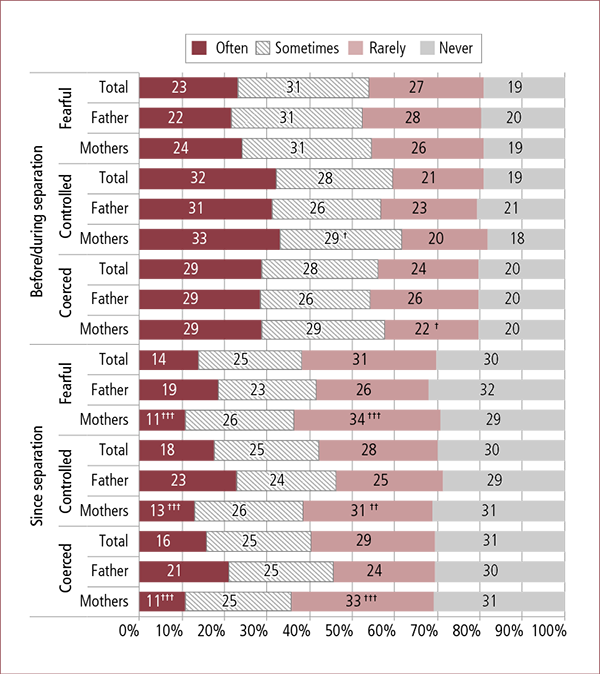

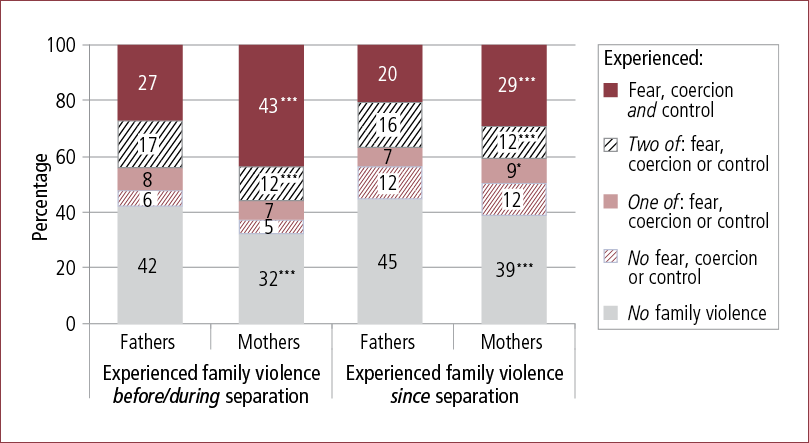

In view of the 2012 amendment to the definition of family violence in FLA s 4AB to encompass "violent, threatening or other behaviour by a person that coerces or controls a member of the person's family (the family member), or causes the family member to be fearful", new questions were included in the SRSP 2014 to capture parents' experiences in this regard. In the before/during separation time period, participating mothers were more likely than fathers to report that the behaviour of the other parent had caused them to feel fearful, coerced or controlled, although these reports were more evenly dispersed between parents in relation to feelings of coercion and control. In the post-separation period, mothers were again more likely to report that they felt fearful, while fathers reported in greater proportions than mothers that they "often" felt coerced or controlled in this time period.

Overall, feelings of fear, coercion and control were more commonly reported by parents who had experienced physical hurt and/or attempted unwanted sexual activity as opposed to emotional abuse. Differences of statistical significance were identified between mothers and fathers who reported feeling fearful, coerced or controlled and experiencing either form of family violence, with these differences emerging both before/during and since separation. Mothers' reports of their feelings of fear, coercion and control were also substantially higher than those made by fathers (see Appendix Figures B10 & B11).

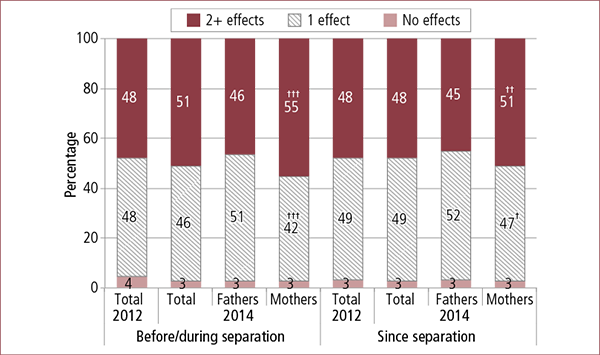

The most commonly reported effects on day-to-day activities made by parents who had reported experiencing family violence in the 2012 and 2014 cohorts related to mental health, with statistically significant increases in the reported experiences of mental health issues emerging between the cohorts both before/during separation (2012: 52% cf. 2014: 66%) and since separation (2012: 52% cf. 2014: 60%). Mothers reported experiencing most of the nominated effects in greater proportions than fathers, and mothers also reported experiencing two or more effects in greater proportions than fathers.

Children witnessing family violence

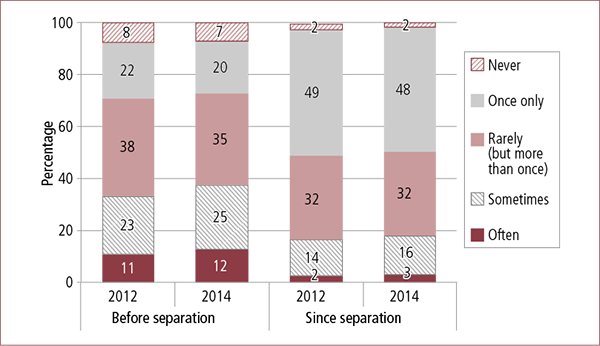

Parents in both the 2012 and 2014 cohorts indicated that their children had witnessed reported emotional abuse or physical hurt in similar proportions, with a greater proportion of mothers than fathers reporting that their children witnessed the family violence before/during separation (mothers - 2012 and 2014: 64% cf. fathers - 2012: 53% and 2014: 54%), and since separation (mothers - 2012: 64% and 2014: 50% cf. fathers - 2012: 53% and 2014: 43%). The decrease in reported post-separation exposure to family violence may reflect greater awareness of the harm caused to children by such exposure, through their interaction with family law system professionals in the post-reform context. When considering parents' reports of the forms of family violence to which their children had been exposed, a higher proportion of mothers than fathers also reported that their children witnessed physical violence compared to emotional abuse alone, with these affirmative reports being particularly pronounced in the post-separation context.

Children's exposure to family violence that resulted in feeling fear, coercion or control was an issue that was also specifically examined in the 2014 survey, given that the definition of abuse in relation to a child in FLA s 4(1) was amended by the 2012 family violence reforms to include exposure to family violence (as defined in s 4AB) that causes serious psychological harm. The SRSP data indicate that the majority of children whose parents reported family violence causing feelings of fear, coercion or control had some exposure to this behaviour. Although the post-separation exposure was lower than in the before/during separation period, the data indicate that most children were nevertheless exposed to behaviour causing these effects, and that fathers' reports were higher than mothers' in this time period, reaching a level of statistical significance.

Safety concerns

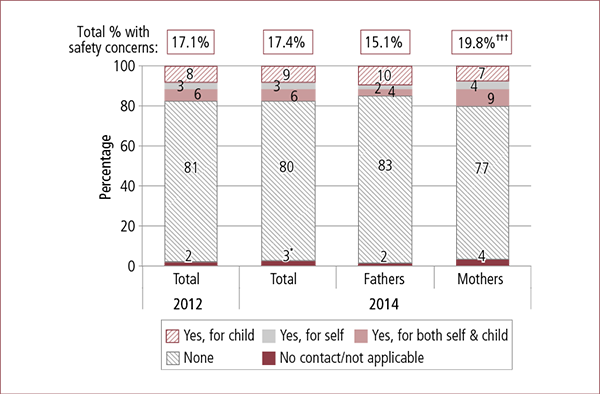

Overall, most parents in both cohorts reported that they did not hold safety concerns for themselves or their child arising from ongoing contact with the other parent. However, around one in six parents (17%) in both cohorts did report holding these safety concerns for themselves and/or their children, with an increased proportion of parents in the 2014 cohort reporting that they tried to stop or limit contact because of these safety concerns (2012: 49% cf. 2014: 52%), though this increase did not reach a level of statistical significance.

Among parents who held safety concerns, significantly more mothers than fathers in both cohorts reported trying to stop or limit contact with the focus parent (mothers - 2012: 62% and 2014: 63% cf. fathers - 2012: 28% and 2014: 36%), though the proportion of fathers attempting to limit contact in 2014 increased significantly in 2014.

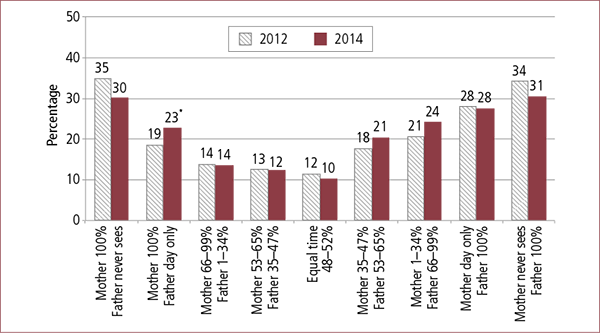

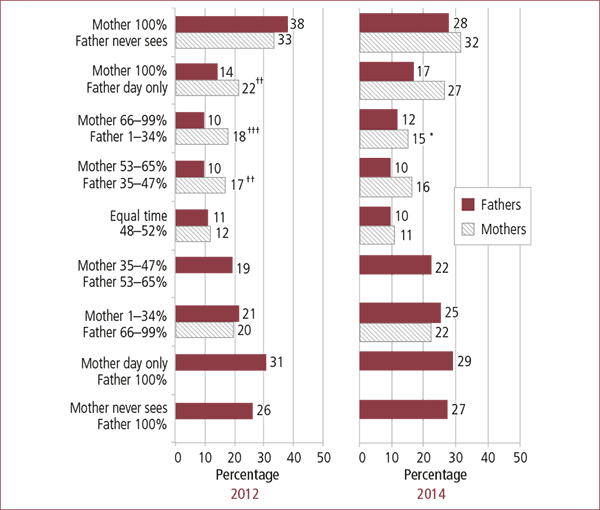

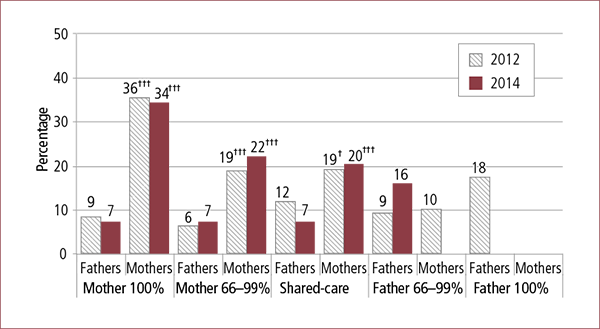

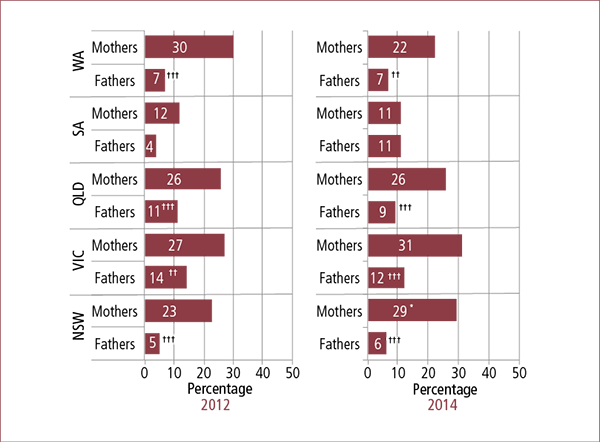

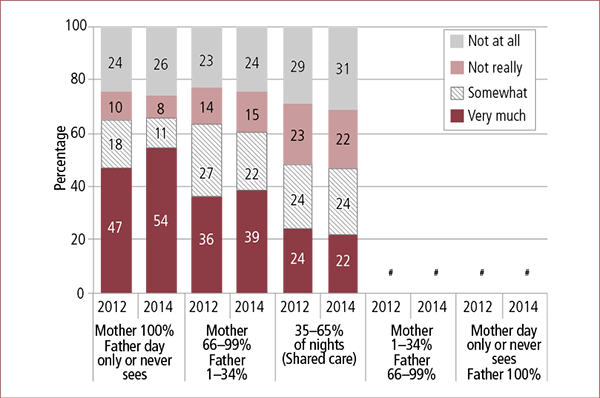

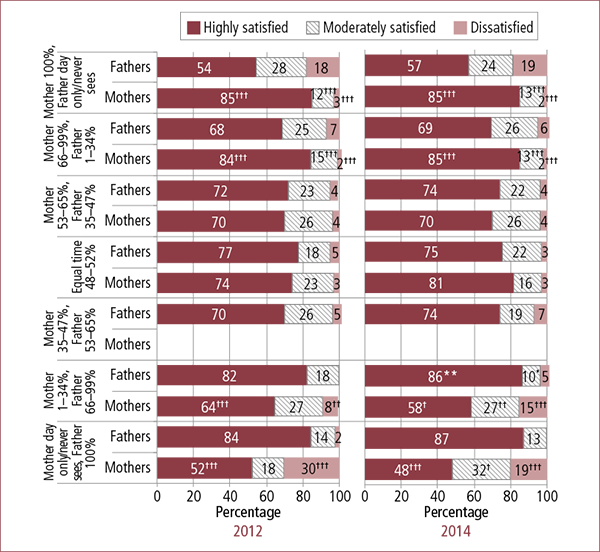

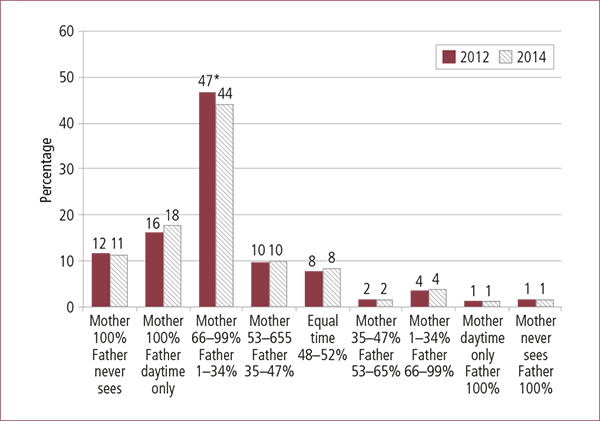

Care-time arrangements

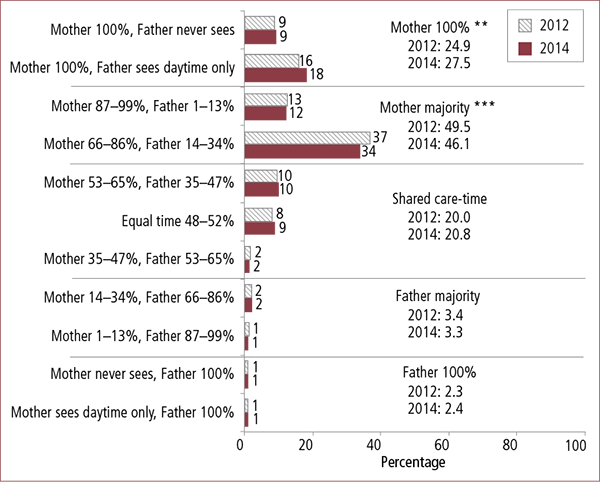

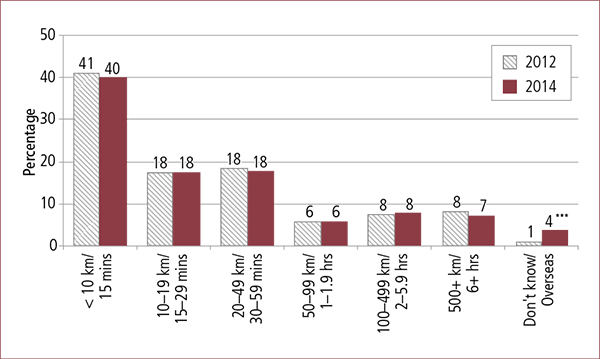

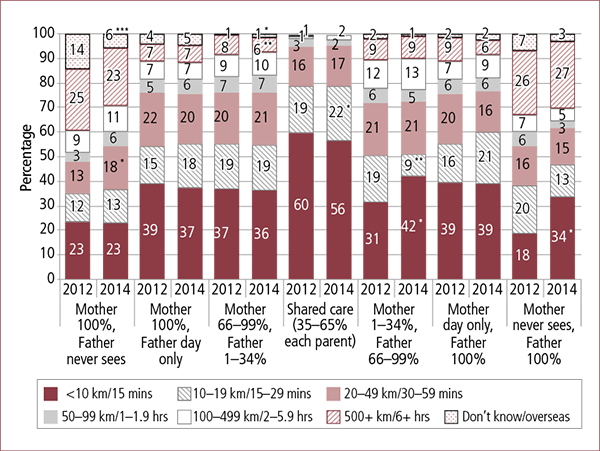

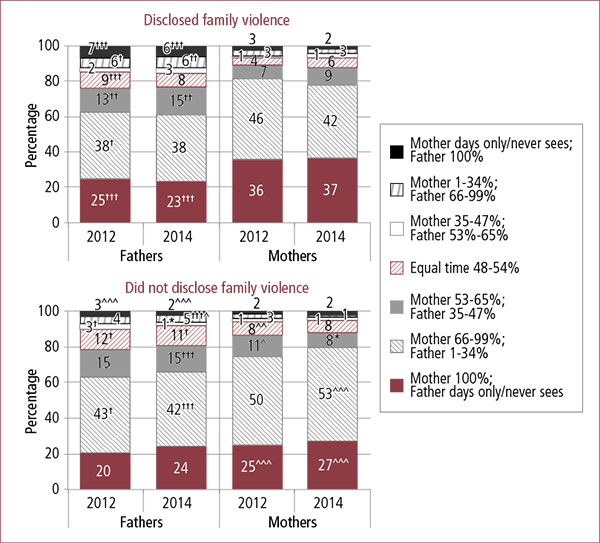

Similar patterns in the distribution of care-time arrangements emerged in the SRSP 2012 and 2014, which were also similar to those evident in the Wave 3 of LSSF. Where the 2014 SRSP cohort differed, these differences were subtle but statistically significant and, as in the previous section, consistent with the objectives of the 2012 family violence reforms. Most children in both cohorts were reported to be living in majority mother care-time arrangements (where the child spends up to 34% of nights with the father) (2012: 50%; 2014: 46%). There was a statistically significant increase in parenting arrangements involving children spending 100% of nights with the mother and time with the father during the daytime only, from 25% in 2012 to 28% in 2014, and a decrease in majority mother care-time, from 50% in 2012 to 46% in 2014.

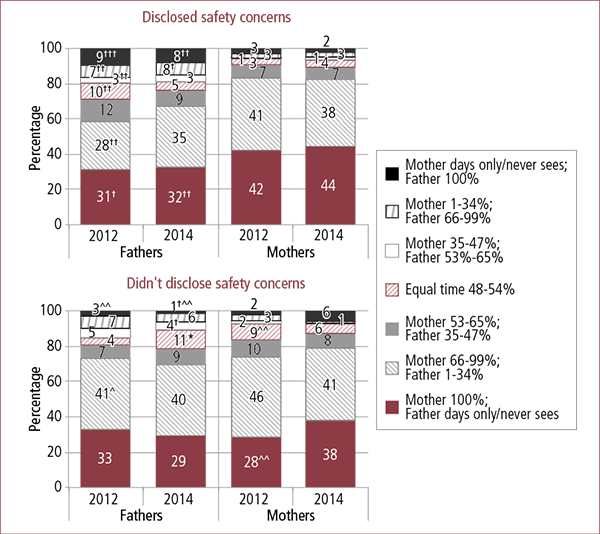

Analyses that focused specifically on the patterns evident among parents with family violence and safety concerns indicated that there was a statistically significant increase in 2014 of care-time arrangements involving children of such parents spending 100% of nights with the mother and no nights with the father. Overall, the change emerging in the 2014 data reflected a shift for such children to have daytime contact only rather than toward arrangements involving no time at all with the father. In circumstances where safety concerns were reported, the findings indicate that 23% of children were in arrangements involving daytime contact only with the father in 2014, compared with 19% in 2012. Decreases in reports of some shared care arrangements (where the child spends 53-65% of their time with the mother and 35-47% of their time with the father) and equal time arrangements were also identified in relation to parents reporting safety concerns, though these were not statistically significant decreases.

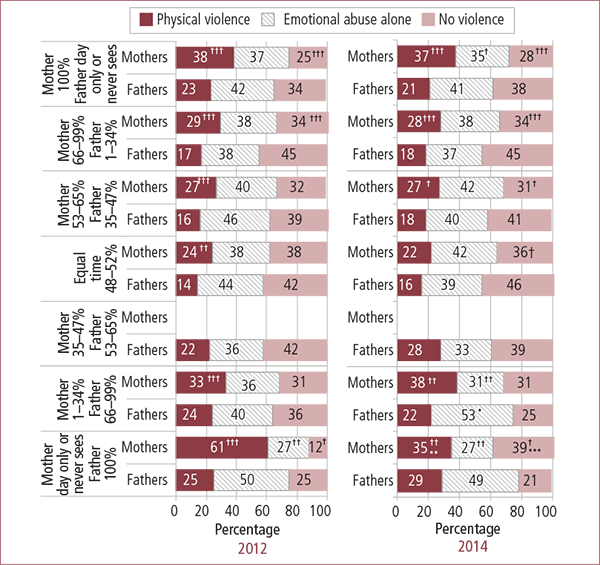

Generally, mothers reported safety concerns in greater proportions than fathers in the context of care-time arrangements ranging from 100% mother care time through to equal time, whereas fathers reported safety concerns in greater proportions than mothers where care-time arrangements ranged from 100% father care time through to shared care arrangements where the father was the primary carer. In relation to the varying forms of family violence, the data also show that experiences of physical violence were reported in circumstances where either parent had majority or 100% care time of the focus child, while emotional abuse alone or no violence showed no discernable pattern among the different care-time arrangements.

Experiences with the family law system: Patterns in service use

The 2012 family violence amendments were not intended to directly influence parents' use of family law system services and, overall, the findings on service use suggest minimal change between the 2012 and 2014 cohorts in this regard. Where change is evident, it is in a direction consistent with the intention of the 2012 family violence amendments.

The overall pattern of service use among the 2012 and 2014 cohorts indicated a greater tendency for the 2014 cohort to make no use of services or supports, and where services were used, the 2014 cohort reported less use of counselling, relationships and family dispute resolution (FDR) services, lawyers, and legal services at the time of separation. This change in patterns of service use reflect the lower use of services reported by parents not affected by family violence, because the patterns in service use by parents affected by physical hurt or emotional abuse remained largely stable between the two cohorts. The only statistically significant change in service use patterns between the two cohorts among parents affected by physical violence since separation was a decrease in the use of counselling/mediation/FDR services by parents who had experienced physical hurt, with 71% of these parents using one of these services in 2014, compared to 77% in 2012.

Data relating to the parents' reported progress in sorting out their parenting arrangements indicate that compared to the 2012 cohort, the 2014 cohort was less likely (to a statistically significant extent) to have sorted out their parenting arrangements (2012: 74% cf. 2014: 71%). In particular, the reforms have not been associated with parenting arrangements having shorter resolution time frames for some parents affected by family violence. While parents in both cohorts affected by physical hurt (and to a lesser extent emotional abuse) were more likely than parents not affected by these issues to report that their parenting arrangements had not been sorted out, majorities of parents in each category in each cohort (save for fathers in the 2014 cohort reporting physical violence since separation) indicated that their parenting arrangements had been sorted out.

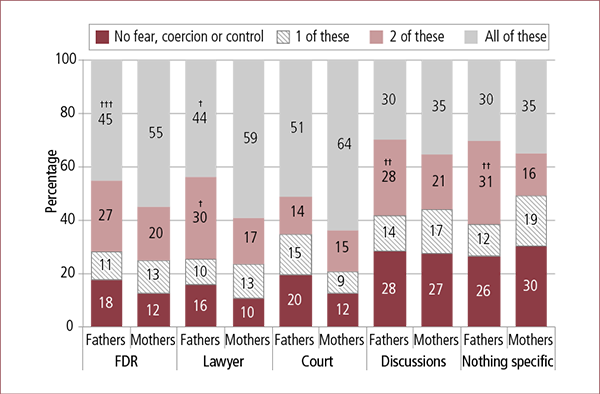

Overall, parents' reports of the pathways that they used to sort out their parenting arrangements were similar among the SRSP cohorts, with most parents (69% in 2012 and 2014) reporting "discussions" as their main pathway. Approximately 10% of the parents reported using counselling/mediation/FDR, with lawyers used by 6-7% of participating parents and courts by 3%. Of those using FDR, a greater proportion of parents in the 2014 cohort (41%) reported reaching an agreement when compared to parents in the 2012 cohort (36%), with this difference reaching a level of statistical significance. The highest rates of agreement via FDR in both cohorts were parents who reported no violence before/during separation (2012: 44%; 2014: 53%). Agreement rates were marginally higher for parents in the 2014 cohort where emotional abuse before/during separation was reported (2012: 36% cf. 2014: 39%). Where physical violence before/during separation had been reported, the agreement rates were substantially higher for parents in the 2014 cohort (38%) than in 2012 (30%), to a statistically significant extent. While patterns remained relatively stable in relation to the use of legal services and courts to reach agreement, where parents used the court system, consistent with the objectives of the 2012 family violence amendments, parents (and mothers in particular) who had experienced physical violence before/during separation in the 2014 cohort were more likely than parents in the 2012 cohort to bring safety issues to court hearings, with this increase reaching a level of statistical significance (2012: 44% cf. 2014: 54%).

Disclosure of family violence and safety concerns

The 2012 family violence amendments included strategies aimed at supporting better identification of family violence and safety concerns by family law system professionals and encouraging parents to disclose these issues. Accordingly, parents' experiences of being asked about (and of disclosing) family violence and child safety concerns were an important focus in the SRSP 2012 and 2014 surveys.

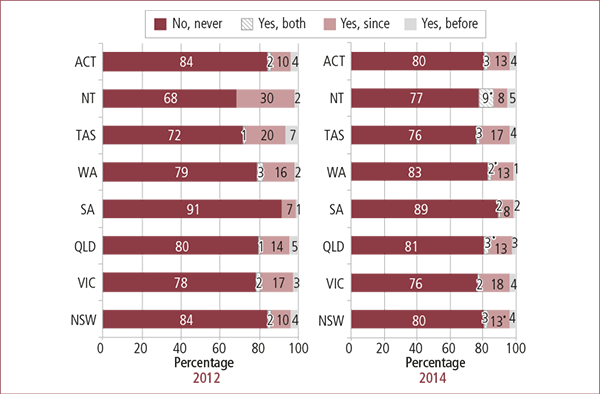

Overall, examination of the 2012 and 2014 SRSP data relating to professionals asking about and parents disclosing family violence and safety concerns suggests subtle positive improvement, consistent with the intention of the 2012 family violence reforms.

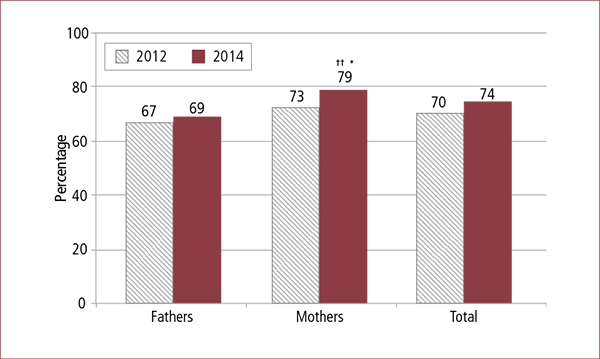

Statistically significant increases were evident in the proportions of parents who reported being asked about family violence and safety concerns when using a formal pathway as the main means of resolving their parenting arrangements. Increases were evident among parents who used the three formal pathways (FDR/mediation, lawyers and courts), but particularly evident for those using lawyers and courts, with increases of approximately 10 percentage points in the proportions who reported being asked about family violence and safety concerns. Notably, however, close to 30% of parents in the 2014 cohort reported having never been asked about either of these issues in each formal pathway, indicating that the implementation of consistent screening approaches has some way to go.

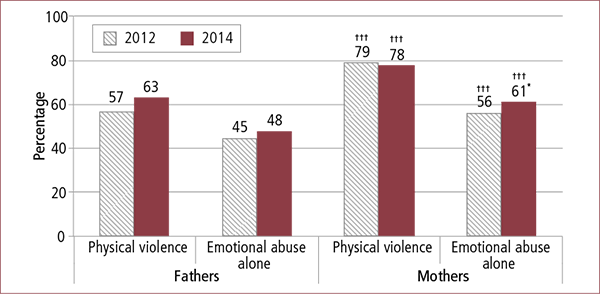

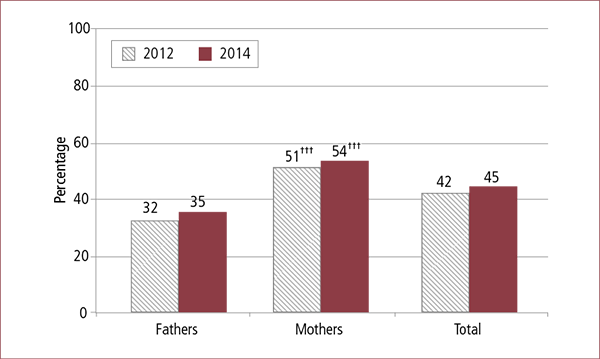

In addition to the increases in parents' reporting that they were asked about family violence and safety concerns, the findings also suggest small increases in the proportion of parents who disclosed concerns. A small but statistically significant increase in the proportion of parents who reported experiencing family violence before/during or after separation to one of a range of possible services and organisations (not confined to the family law system) was evident (2012: 53% cf. 2014: 56%), with mothers in 2014 being more likely to report violence than fathers (63% cf. 49%). Physical hurt was more likely to be reported in 2014 than emotional abuse, and the most common service reported to was police (25%). Of note, just over 40% parents did not report family violence to any service in 2014.

Parents self-selected into non-disclosure for a varied range of reasons, including that the family violence or safety concerns were not serious enough to report (2012: 43%; 2014: 38%) or that they could deal with the issue themselves. These findings mean that for a substantial number of people, a history of family violence has not been documented or corroborated, which may or may not have significant implications, given that non-disclosure does not necessarily equate to family violence at the lower end of the spectrum of severity.

More specifically, the proportion of parents who reported disclosing family violence or safety concerns to family law services increased by about 3 percentage points between 2012 and 2014, with the change reaching a level of statistical significance. The findings on the proportions of parents who reported disclosing family violence or safety concerns in the context of making parenting arrangements when using particular pathways demonstrates that increasing increments of parents reported disclosing each type of concern across each pathway in both 2012 and 2014, although reports of disclosure were lowest for parents who used FDR and highest for parents who used courts. Notably, where participating parents reported in the survey either having current safety concerns or having experienced family violence, safety concerns were more likely to be disclosed than family violence.

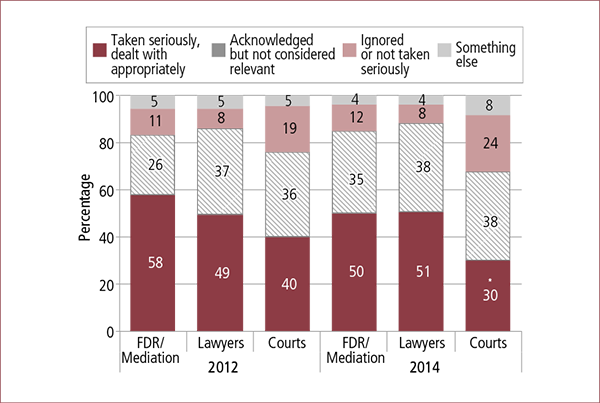

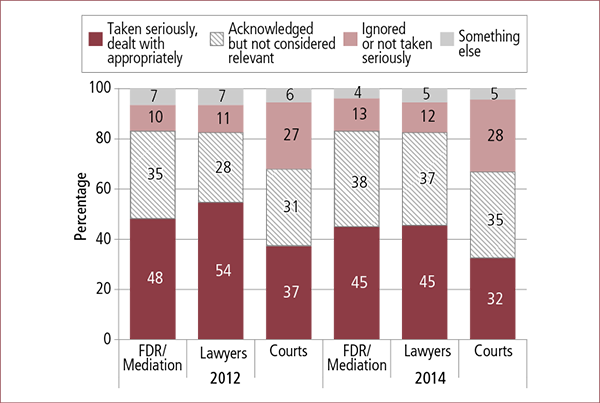

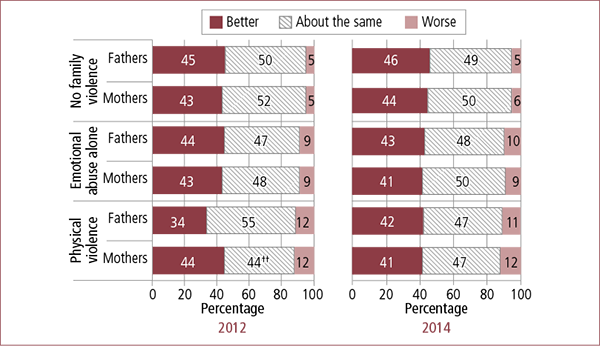

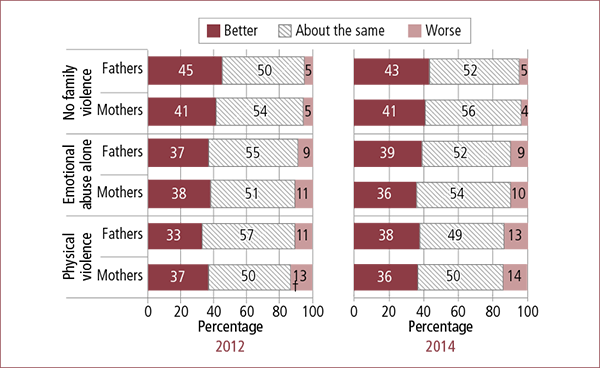

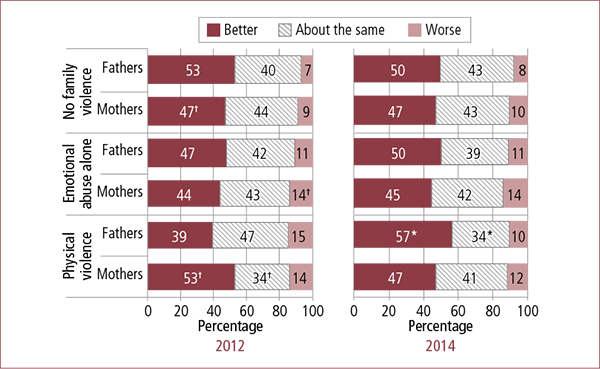

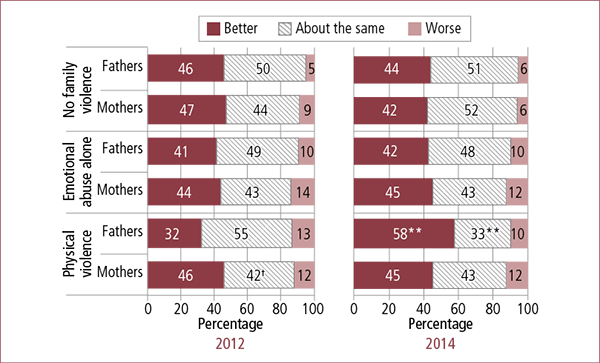

Mixed findings emerged from the examination of the consequences of disclosure of concerns when assessed against the objectives of the 2012 family violence reforms. Reports of experiences with different pathways varied among participating mothers and fathers, but there were small shifts, and these were mostly evident in a negative direction for parents with family violence and safety concerns for both genders, using all formal pathways (FDR, lawyers, courts). The exception to this was in relation to lawyers and family violence: positive responses among mothers were stable and increased among fathers. Other aspects of the examination of the consequences of disclosing family violence or safety concerns based on parents' reports of what occurred indicate that there were limited short-term effects, though there was some evidence of an increase in referrals to other services and marginally greater use of personal protection orders (relating to safety concerns only) and safety planning.

Parents' views on the efficacy of the family law system

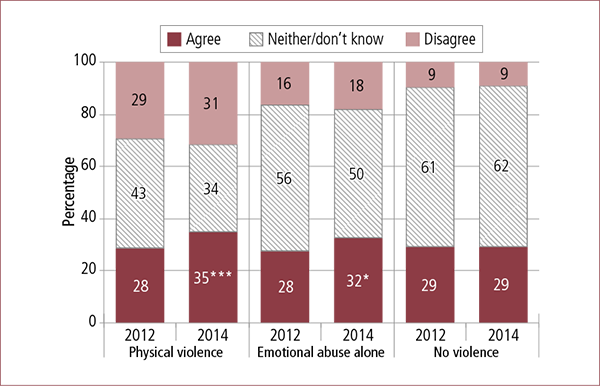

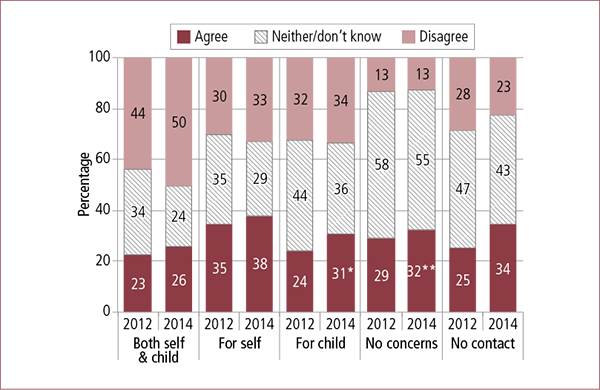

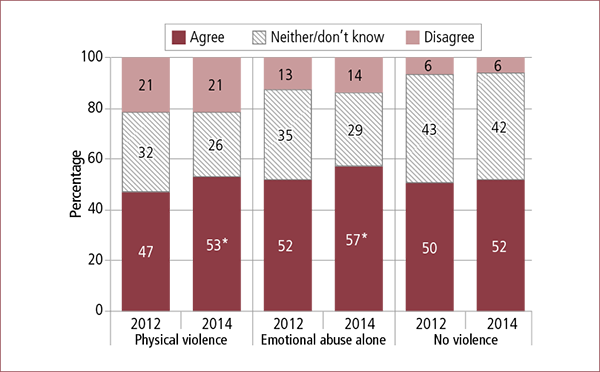

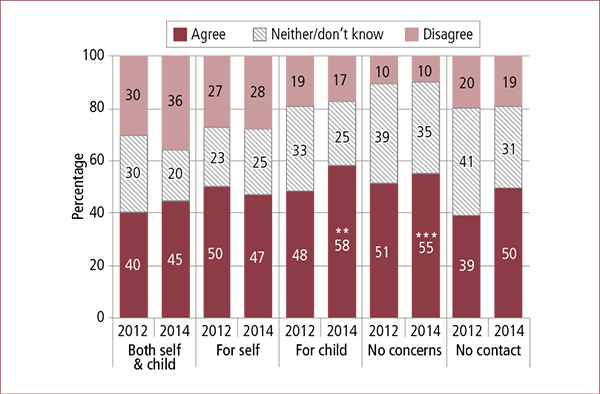

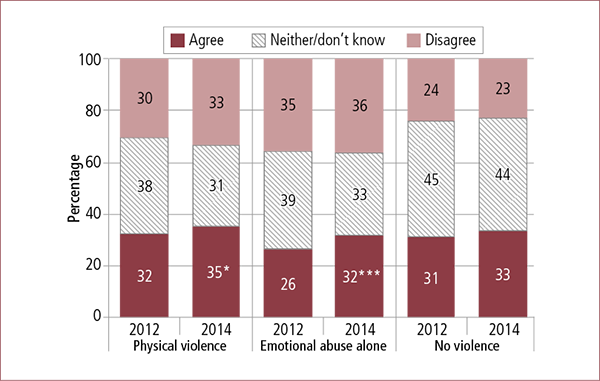

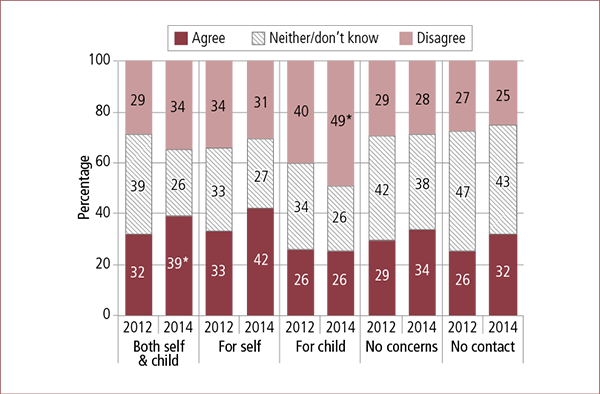

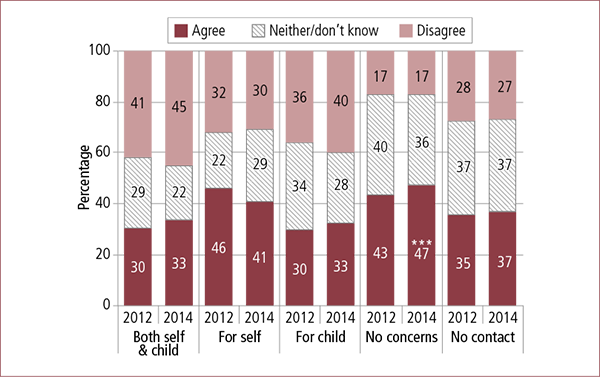

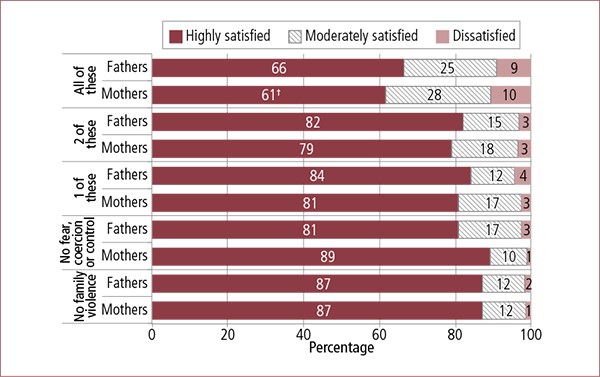

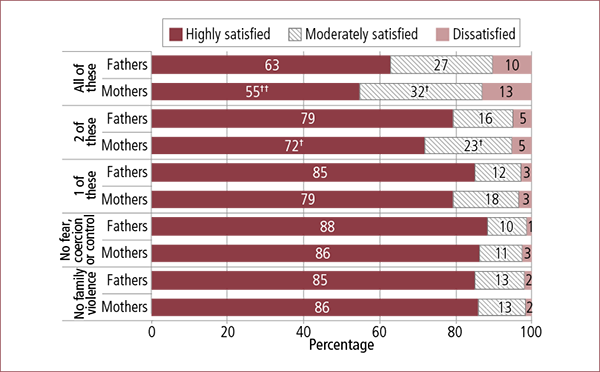

Overall, the views reported by parents participating in each cohort regarding the efficacy of the family law system suggest some positive changes in directions consistent with the intention of the 2012 family violence amendments.

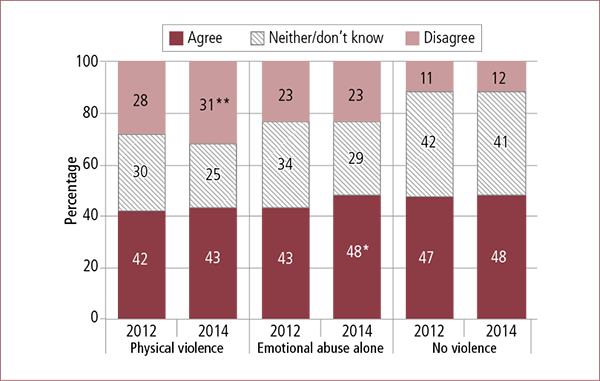

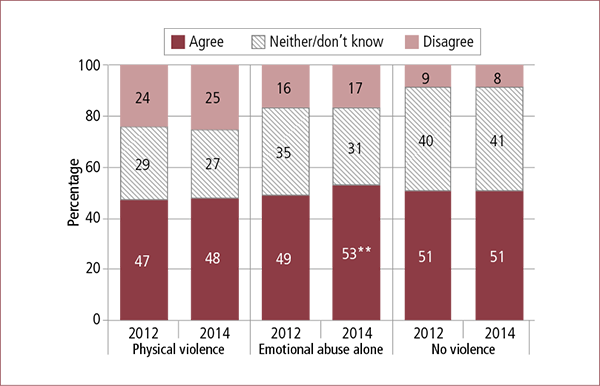

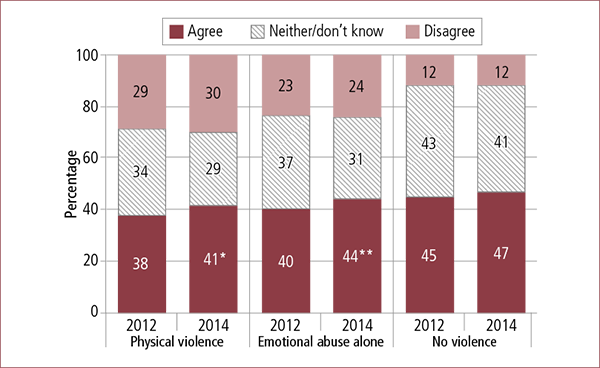

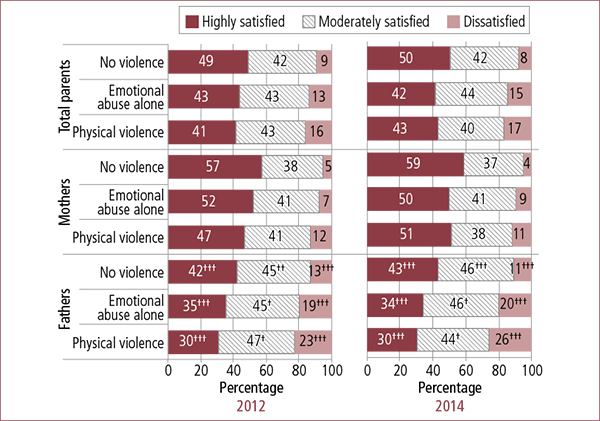

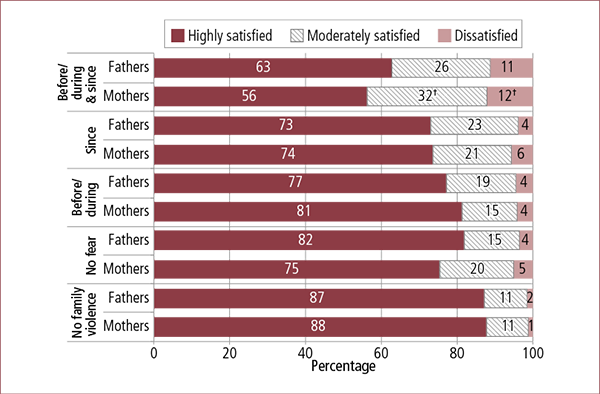

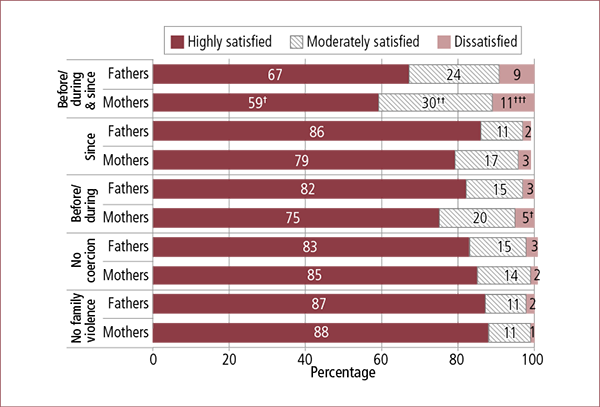

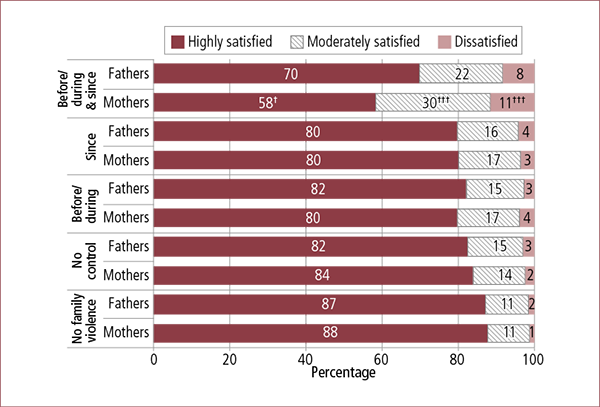

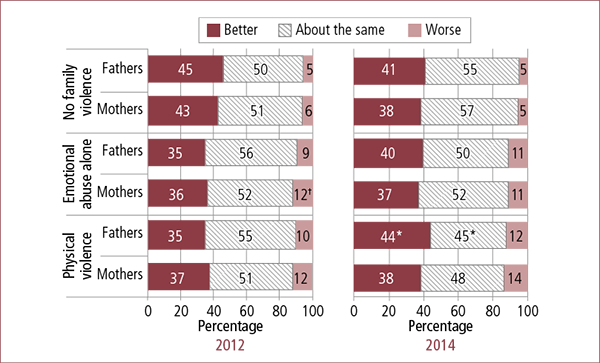

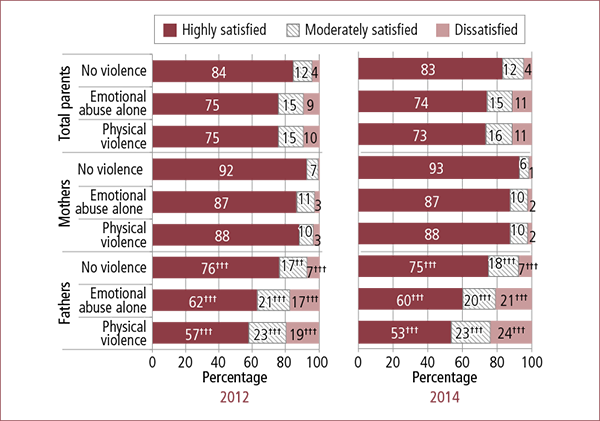

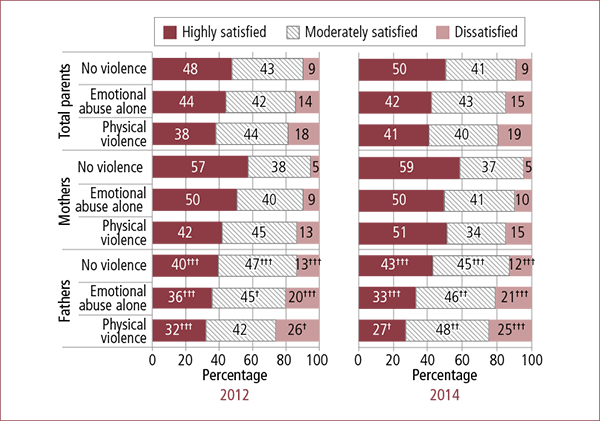

From the perspective of gender, positive views in most areas on measures of efficacy increased incrementally among both mothers and fathers, but among mothers to a greater extent than fathers. Fathers in both cohorts were less satisfied with the family law system than mothers, but this disparity had not widened.

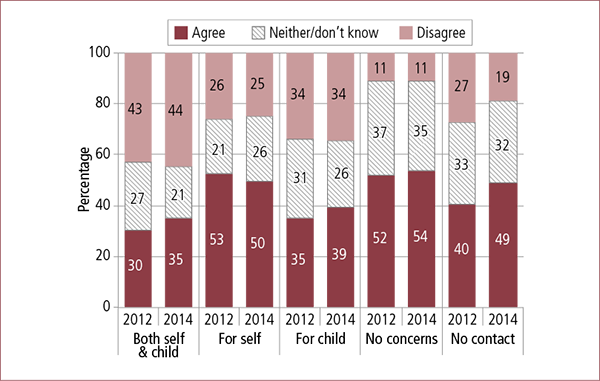

In relation to the experiences of parents reporting family violence, the data suggest a marginal improvement in the views of parents affected by family violence, although this was true to a greater or lesser extent according to the measure and whether the experience involved was physical hurt or emotional abuse. Differences among these groups were evident in different areas, suggesting uneven effects of the reforms, consistent with findings reported in relation to service use. Less positive findings emerged in relation to the family law system protecting children's safety, with agreement among parents with safety concerns for themselves and/or their child in some areas changing little if at all, and with negative shifts for some sub-groups. These findings suggest a particularly mixed set of views and experiences among parents.

Mixed and uneven experiences were also reflected in data relating to nominated pathways. In relation to pathways involving lawyers and courts, there were no clear or consistent statistically significant findings. There was some evidence that the reforms supported the resolution of parenting matters in agreement-based pathways, specifically "discussions" and mediation/FDR.

Finally, in relation to reported awareness of the 2012 family violence amendments, the data indicate a marginal increase among parents in the 2014 cohort, with fathers affected by physical violence and mothers affected by physical violence and/or emotional abuse being more likely to have specific knowledge of the changes in 2014 compared with 2012. Nevertheless, the vast majority of parents (95%) were unaware of the 2012 family violence amendments.

Summary

The findings of this report are based on data from two separate samples, each of over 6,000 separated parents, who had separated either before or after the 2012 family violence amendments. Overall, the findings described in this report suggest some positive shifts in a direction consistent with the intention of the reforms in some areas, and limited or mixed effects in other areas. Consistent with the intention of the reforms, there is evidence of increased emphasis on identifying family violence and child safety concerns across the system, but particularly among lawyers and courts. More parents who used formal services reported being asked about these issues, and increases in parents reporting disclosing were also evident, particularly in relation to safety concerns. There is also evidence that parents with safety concerns were more likely to seek support from family law system services to stop or limit contact than they were before the reforms.

The evidence on parents' experiences of professionals' responses to disclosures of family violence and safety concerns suggest the reforms have had limited effects in this area, particularly for parents who reported using lawyers and courts as their main pathway for parenting arrangements. In contrast, the reforms appear to have supported the resolution of parenting arrangements through agreement-based pathways ("discussions" and FDR/mediation) for parents who had and had not been affected by family violence. The aspect of the reforms likely to be linked to these outcomes are the clarification of advisors' obligations in s 60D, which requires lawyers, FDR practitioners and other professionals to inform parents that the most important issue in making parenting arrangements is their children's best interests. This obligation, together with an obligation to inform parents that where there is a conflict between protecting children from harm and maintaining their relationship with each parent after separation, protection should be given greater weight, were added to the existing obligation to inform parents that they may consider equal or substantial and significant time arrangements.

There was some evidence of an increased emphasis on measures designed to support safety. There was also a subtle shift towards making more arrangements for children to live with their mothers and have daytime-only contact with their fathers where there had been family violence, with a corresponding decrease in arrangements involving overnight stays in these circumstances. Where parents relied on lawyers and courts for making parenting arrangements against a background of family violence or safety concerns, they were, on average, just as likely to indicate they did not consider the professionals' responses to their concerns were adequate, especially in relation to safety concerns, after the reforms.

This report sets out the findings of a core element of the Evaluation the 2012 Family Violence Amendments project - the Experiences of Separated Parents Study (ESPS). This element is based on a comparison of data from two cross-sectional samples of the Survey of Recently Separated Parents (SRSP): the 6,119 parents surveyed in the SRSP 2012, who used family law system services in 2011; and the 6,079 parents surveyed in the SRSP 2014, who experienced the system in 2013. The family violence amendments introduced by the Family Law Legislation Amendment (Family Violence and Other Measures) Act 2011 came substantially into effect on 7 June 2012, meaning the SRSP 2012 survey represents parents' pre-reform experiences and the SRSP 2014 their post-reform experiences. This research was commissioned and funded by the Australian Government's Attorney-General's Department (AGD) and conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS).

Together, the SRSP 2012 and 2014 studies provide insights into any changes in the ways in which parents have experienced the family law system as a result of the 2012 family violence amendments. These amendments were intended to improve the identification of and response to matters involving family violence and safety concerns. A consistent approach to survey questions, the sampling approach and fieldwork methodology for the SRSP 2012 and 2014 was applied, meaning that statistically rigorous analyses comparing pre- and post-reform patterns in the responses to the survey questions are reported. The samples for the two surveys were derived from the Department of Human Services - Child Support (DHS-CS) database, substantially repeating the approach applied in the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families (LSSF), which was part of the 2009 Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms. As such, it has continued beyond that research program to allow understanding of the experiences of separated families over the longer term.

Through its focus on the pre- and post-reform experiences of two large, nationally representative and comparable samples of separated parents, the ESPS forms a central plank in the three-part research program comprising the overall evidence base for the Evaluation the 2012 Family Violence Amendments project. The first part, the Responding to Family Violence study, focused on practitioner views and experiences, the findings of which were presented to the AGD in the Responding to Family Violence: A Survey of Family Law Practices and Experiences report on 19 December 2014 (Kaspiew, Carson, Coulson, Dunstan, & Moore, 2014). This current document, analysing the SRSP 2012 and 2014 data, reports on the second part of the evaluation (the ESPS), while the findings from the Court Outcomes Project comprise the third. Together, the three parts of the evaluation research program address a series of research questions, ensuring that the critical questions can be addressed on the basis of more than one source of data. Each of these parts supports a nuanced interpretation of findings across the evaluation, supporting robust conclusions based on triangulation of data sources. A synthesis report based on all three parts of the research program is due for delivery to the AGD on 31 August 2015.

In light of consistent evidence and analyses showing that family violence and child safety concerns are pertinent to substantial numbers of separated families (e.g., Kaspiew et al., 2009; Qu, Weston, Moloney, Kaspiew, & Dunstan, 2014) and highlighting a need for improved responses (Australian Law Reform Commission [ALRC] & NSW Law Reform Commission [NSWLRC], 2010; Chisholm, 2009; Family Law Council, 2009), the 2012 family violence amendments sought to improve rates of disclosure of family violence and safety concerns, and to support better responses by professionals to such disclosures. In addition to obligations concerning disclosure being placed on professionals and parties (s 69ZQ(1)(aa), s 67ZBA, s 67ZBB, s 69Z and s 60CI), the legislative amendments specified that where the legislative principles concerning protection from harm were in conflict with those recognising the child's right to meaningful involvement with each parent after separation, greater weight should be accorded to protection from harm by advisers1 (s 60D(1)(b)(ii)) and court settings (s 60CC(2A)). Further important changes were the widening of the definition of "family violence" and explicit acknowledgement in the legislation that exposing children to family violence amounts to child abuse where it causes serious psychological harm (s 4AB, s 4(1)).

Accordingly, a core focus of the SRSP 2012 and 2014 studies was parents' experiences in disclosing concerns about family violence and safety and the way in which family law system professionals responded to such disclosures. Parents' experiences of family violence and safety concerns were also examined in detail, as was exposure of children to family violence. The research also maintained a focus on parents' use of services, patterns in parenting arrangements, child support arrangements, and parent and child wellbeing to further support conclusions about the consequences of the 2012 family violence amendments, and to continue developing the evidence base established in the LSSF research program. The research questions for the evaluation of the 2012 family violence amendments are considered in section 1.1 and are set out in full in Appendix 1.

The SRSP 2014 represents the third comparable dataset in a series commencing with the LSSF Wave 1 (2008) and continuing with the SRSP 2012. Each of these datasets describes the features and experiences of discrete annual cohorts of separated parents. Together, they shed light on what can be seen to be the consistent features of each annual cohort of separated parents, including the extent to which family violence and safety concerns were relevant to these cohorts, patterns in parenting arrangements and patterns in service use.

1.1 Research design

The SRSP 2014 is based on a methodology that compares the pre- and post-reform experiences of two nationally representative and comparable samples of separated parents with children under the age of 18 years. The pre-reform survey data collection (SRSP 2012) examined the experiences of parents who had separated between 1 July 2010 and 31 December 2011. The experiences of this cohort of separated parents reflected the way in which the system operated in the two-year period prior to the operation of the 2012 family violence reforms. The post-reform survey data collection (SRSP 2014) took place from 7 August to 30 September 2014 and involved a sample of parents whose separations took place between 1 July 2012 and 31 December 2013. The experiences of this second cohort of separated parents reflected the operation of the family law system in the 12- to 18-month period following the introduction of the 2012 family violence reforms.

Data from the SRSP 2014 builds on those of SRSP 2012 to form the basis for the analysis undertaken in the Experiences of Separated Parents Study. Together with the Responding to Family Violence: A Survey of Family Law Practices and Experiences study and Court Outcomes project, the three studies comprise the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments, and the research questions for this evaluation reflect the aims of the amendments. They encompass a series of broad-level research questions, together with a series of more specific research questions shaping each of the separate studies contributing to the evaluation.

The broad-level research questions are:

- To what extent have patterns in arrangements for post-separation parenting changed since the introduction of the family violence amendments, and to what extent is this consistent with the intent of the reforms?

- Are more parents disclosing concerns about family violence and child safety to family law system professionals?

- Are there any changes in the patterns of service use following the family violence amendments?

- What is the size and nature of any changes to practices among family law professionals and to court-based practices and to what extent are any such changes consistent with the intent of the reforms?

- Does the evidence suggest that the legislative changes have influenced the patterns apparent in questions 1-4 above?

- Have the family violence amendments had any unintended consequences, positive or negative?

The SRSP 2014 makes a further contribution to the existing evidence base on the operation of the family law system. Key aspects of the design and sampling strategies of the SRSP 2012 and the LSSF Waves 1, 2 and 3 were used to maintain the comparability of this new cohort of separated parents with the experiences of parents participating in LSSF who (mostly) separated in 2007 and experienced the family law system soon after the 2006 reforms, as well as those of the SRSP 2012 parents, who engaged with the family law system some four years later. The experiences of the SRSP 2014 cohort not only provide further evidence about the operation of the post-2006 system, but also enable comparison against the benchmarks established by the SRSP 2012, which together provide a context in which to examine the effects of the 2012 family violence reforms.

Consistent with the methodology adopted for the LSSF and the SRSP 2012, data collection was undertaken for the SRSP 2014 via surveys administered using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI), and the sampling frame used was the DHS-CS database.

The key areas investigated in the SRSP 2014 were in large part consistent with the SRSP 2012 and similar to Wave 1 of the LSSF, and included:

- the separation pathways and parenting arrangements of participating parents; and

- the nature and strength of any connections between the co-parental relationship and other aspects of parental involvement in the children's lives after family separation.

Consistent with the evaluation research questions and with the SRSP 2012, areas of examination also included:

- the nature (severity and frequency) of family violence experiences, whether family violence and/or safety concerns had been reported to family law and non-family law professionals, and the response of professionals where family violence and/or safety concerns had been reported;

- whether any concerns relating to family violence and/or safety concerns had been raised during the negotiation of parenting arrangements and, if not raised, reasons for not doing so; and

- if family violence and/or safety concerns had been raised, whether such concerns had been considered when negotiating parenting arrangements, and the effects of any such considerations on the nature of parenting arrangements made.

Consistent with SRSP 2012, all parents were again asked whether they knew about the family violence amendments that substantially commenced on 7 June 2012, and to provide their views on the efficacy of the family law system in handling matters involving family violence and safety concerns, and the extent to which the system meets the needs of mothers, fathers and children.

1.2 Data collection

The SRSP 2014 was a survey of 6,079 parents with children aged under 18 years old who (a) separated between 1 July 2012 and 31 December 2013, (b) registered with DHS-CS during 2013, and (c) were still separated from the other parent (known as the "focus parent") at the time of interviewing.

The interviews were carried out using CATI between 7 August and 30 September 2014, with the average interview being 36.8 minutes in duration. Consistent with SRSP 2012, parents participating in SRSP 2014 were asked demographic questions about themselves, their former partner ("the focus parent"), and the eldest child from their union listed in the DHS-CS database (the "focus child"). Once again, the substantive questions asked related to the parenting arrangements that had been made since separation, the quality of their inter-parental relationships, their separation pathways (including any contact with family law system professionals), their experiences of family violence and safety concerns, the wellbeing of their children, and the payment or receipt of child support.

1.2.1 Sample extraction and preparation

In line with Wave 1 of the LSSF and with SRSP 2012, the sample for the SRSP 2014 was drawn from the DHS-CS database, as this database is the most comprehensive and viable data source from which to obtain a representative sample of recently separated parents. This approach was also intended to maximise comparability between the LSSF and SRSP datasets.

As with the LSSF and SRSP 2012, the sample extraction for SRSP 2014 was based on the date on which cases were registered with DHS-CS. For SRSP 2014, registration was to have taken place between 1 January and 31 December 2013, with separation dates from 1 July 2012, where specified. As noted in SRSP 2012, the date of registration for child support is considered to be a good proxy for the date of separation, as most parents register within the three-month period following separation. The sample extraction requirements also provided that a case registered with DHS-CS included both the parent who was the payer of child support and the parent who was the payee, and (consistent with LSSF and SRSP 2012) the first listed child of that relationship (the focus child).

The sample list provided by DHS-CS on 1 May 2014 nominated 35,837 cases. Of the 71,674 individual parents included in the extracted sample, 22,630 of these parents were excluded from the final sample because: they had opted out of the project (n = 2,712), there were missing data in the sample extract file for the other parent (n = 18,219), there was no contact phone number listed for the parent (n = 1,163), they had been included in the SRSP 2012 sample (n = 100), or the parent had featured in "mirror cases" (n = 436). Mirror cases arose in the sample where the same two ex-partners appeared as two separately listed cases, showing one as a payer of child support and the other as a payee. In each instance where mirror cases arose, one of the ex-partners was randomly removed from the sample. A number of discrepancies emerged between the sample extraction requirements and the sample that DHS-CS provided to the fieldwork agency contracted by AIFS to undertake the data collection. A higher than anticipated proportion of the sample extracted was provided without a separation date (n = 12,667 cases; n = 25,334 individual parents), residential addresses were not always provided, not all cases in the sample included payer and payee details, and the details from one parent were missing in the 18,418 cases.

The Department of Human Services mailed letters to the extracted sample of potential participants that provided information about the SRSP 2014 and included an opportunity for them to opt out of the research. Those opting out of the research prior to 3 April 2014 were removed from the sample provided to the fieldwork agency. The main survey sample comprised 28,513 individuals to be approached for participation in the main survey, with this sample distributed across the eight Australian states and territories. This figure was identified as being the required number of individuals to be approached in order to achieve the target sample of 6,000 interviews, assuming a response rate of 21%, based on the experience from conducting the SRSP 2012.

Once again, consistent with SRSP 2012, the SRSP 2014 sample was stratified by state/territory, gender and payer/payee status. In some strata, all potential participants in the sample were selected (e.g., all female payer cases were selected), while in other strata random selection of potential participants were selected (e.g., a proportion of male payer cases were randomly selected). This was done to achieve a geographically proportional sample.

For call outcome statistics for the responding sample, see Appendix 2.

1.2.2 Ethical considerations

The AIFS Human Research Ethics Committee provided ethical review and approval of the SRSP 2014, covering all aspects of the methodology, survey instrument, participant materials and data collection protocols. Fieldwork for the SRSP 2014 was contracted to the same third-party fieldwork agency (with the same management team) that had been retained to undertake the data collection for SRSP 2012. Thorough training sessions and manuals were provided to the CATI interviewers, including training to deal with participant distress and the handling of disclosures of harm and safety concerns. In addition, the SRSP 2014 survey instrument was pilot tested, with these issues among the considerations monitored, and an intensive level of supervision and debriefing employed throughout the fieldwork period. Detailed duty-of-care protocols (devised in accordance with the AIFS Child-Safe Research Policy, requirements for ethics clearance, and legal obligations, as was employed for SRSP 2012) were put in place to facilitate appropriate responses in cases arising during data collection that involved the disclosure of information that could potentially trigger a mandatory reporting obligation (i.e., in cases where there was a risk of family violence or child abuse). Although the duty-of-care protocols were applied to participants in all states and territories, given the specific mandatory reporting requirements in the Northern Territory, only a select team of experienced interviewers conducted interviews with these participants. The Northern Territory survey also included a more specific introduction script that informed potential participants of the mandatory reporting obligations, whereby any disclosures by participants to interviewers of immediate "threats or serious risk of family violence or cases of child abuse" could be required to be reported to the relevant authorities. Participants were also informed that they could refrain from answering any questions that they did not wish to answer. Only five reports were made to the relevant state or territory authorities (with four reports made to the relevant prescribed child welfare authority and one report to the family violence unit of the relevant police department), with these reports being made by senior research staff at the fieldwork agency, in consultation with AIFS.

In addition to the measures noted above, a number of prompts were programmed at relevant intervals in the survey to remind interviewers to offer participants referral numbers to support services if/when it was necessary. At the end of each survey, interviewers recorded whether they had offered referral numbers and whether participants had accepted them. Of the 3,645 offers made to participants (60% of all interviews), 31% (n = 1,122) accepted the referrals that were provided at the time of the interview or, upon the participants' request, at a later date (through email, postal mailout, or by follow-up phone call).

1.2.3 Participant recruitment and data collection

As noted at section 1.2.1, all potential participants listed in the sample were mailed a letter providing them with the opportunity to opt out of future research. All opt-outs received within the specified timeframe (n = 2,712) were removed from the database prior to the sample being released to the fieldwork agency contracted to undertake the data collection.

All potential participants (n = 28,513) were mailed personalised primary approach letters, together with an information brochure prepared by the fieldwork agency on AIFS' behalf, in the week prior to their record being loaded into the survey sample for initial telephone approach. The pre-approach letter and brochure outlined the SRSP 2014 and provided information about participant privacy and confidentiality, together with contact information for both AIFS and the fieldwork agency for further information on the research. The letter also provided a project-specific toll-free 1800 number and email address (maintained by the fieldwork agency's research supervisors) for any participants or potential participants who wished to find out more about the study, change their contact details, make an appointment for an interview, or opt out prior to or during the fieldwork period.

As noted in section 1.2.2, all interviewers were provided with training by the fieldwork agency via a briefing session and an interviewer manual prior to commencing fieldwork. The project employed 107 interviewers and 16 supervisors, who were briefed at four interviewer briefing sessions held between 5 and 14 August 2014. The briefing sessions covered the background to the study, a detailed explanation of the questionnaire and sample, participant confidentiality, response maximisation techniques, complaint handling, dealing with interviewer and participant distress (including when to offer referrals to relevant national and state-based support services), and duty-of-care issues and protocols (including mandatory reporting requirements in the Northern Territory). Together with the interviewer manual, interviewers were also provided with briefing packs that included copies of the opt-out and primary approach letters, the participant information brochure, a copy of a fact sheet titled Changes to the Family Law from 7 June 2012, and a list of national and state telephone support services together with the protocols regarding referrals to these support services.

Consistent with SRSP 2012, all participant information, including details of the focus parent and focus child, were kept in password-protected files on a secure server with restricted access at the offices of the fieldwork agency. Interviewers and their supervisors did not have access to any identifiable participant information except as provided to them within each individual survey. All identifiable details were removed from the data file of completed interviews provided to AIFS for analysis.

1.2.4 Data collection issues

Thorough testing of the survey was carried out by both the fieldwork agency undertaking the data collection and by AIFS prior to commencement of the main data collection. An interim dataset was also provided to AIFS for review part way through the data collection period.

A new survey module was introduced to SRSP 2014 as part of the parent component of the Responding to Family Violence: A Survey of Family Law Practices and Experiences study. This module was placed just after the family violence disclosure module of the SRSP 2014 questionnaire and immediately before the family law system outcomes module (discussed in this chapter). This placement was considered the most appropriate for the SRSP instrument as it caused the least disruption to the flow of the interview (given that the topic of that module was about similar services and experiences to those that had just been discussed in the existing SRSP questionnaire). However, at the beginning of this module, parents were advised to let the interviewer know if they felt a question did not apply to their situation. Although this approach was considered appropriate (given that many aspects of services would not apply for some parents due to limited contact), it resulted in the SRSP 2014 cohort of parents responding more frequently with "Not applicable" to the subsequent SRSP module (family law system outcomes and experiences). As "not applicable" wasn't a valid response for questions in this module, interviewers used appropriate probing methods to encourage parents to select a valid response (e.g., "agree" or "disagree"). Although this interviewing approach was consistent with the interviewing methods in SRSP 2012, the analysis shows that in 2014, where parents did not "agree" or "disagree", they tended to respond with "don't know" rather than "neither agree nor disagree". In contrast, notably higher proportions of parents in SRSP 2012 than 2014 nominated "neither agree nor disagree" when probed (though "don't know" was still more common than "neither" in 2012). Further examination showed higher proportions of "neither agree nor disagree" in 2012 compared with 2014, but higher proportions of "don't know" in 2014 than in 2012. However, when the two responses ("don't know" and "neither") were combined, the proportions were very similar.2

We speculate that this discrepancy between the two cohorts may be associated with the introduction and placement of the Responding to Family Violence: A Survey of Family Law Practices and Experiences module in 2014, and that for this cohort, parents who initially responded to the SRSP questions with "not applicable", when probed, selected "don't know" rather than "neither agree nor disagree" as the most appropriate response. Although for all other sections of the report we have excluded "don't know" responses, analysis of the section on family law system outcomes and experiences reveals that a significant minority of parents did not feel they were able to answer these questions definitively (by either agreeing or disagreeing with the statements). For this reason, we have included the "don't know" and "neither agree nor disagree" responses (combined for succinctness) in the analysis of the family law system outcomes module.

1.2.5 Analytical approach

Consistent with SRSP 2012, the analysis presented in this report is based on weighted data. The sample data for parents was first weighted to take into account the unequal probability of sample selection of participants with different characteristics. The variables used to develop the weights were the same as those used in Wave 1 of the LSSF and in SRSP 2012.3

Data were analysed using STATA MP Version 13, and data items were further analysed by participants' gender and, where relevant, by their experiences of family violence. For the majority of the data items reported here, the proportions of "don't know" or "refused" responses were less than 2% of the combined total in most cases. As such, the "don't know" and "refused" responses have been excluded from most of the reported analyses, except in a small number of tables and figures as marked.

Statistical significance testing was undertaken where indicated in relation to comparisons between SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014. With respect to SRSP 2014 data analysed in isolation, statistical significance testing was conducted only for selected items (where indicated), so any differences in reported data that do not indicate statistical significance should be interpreted with this in mind.

1.2.6 Limitations

This research represents one component of the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Reforms. The main findings of the overall research program are set out in the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments: Synthesis Report (Kaspiew, Carson, Dunstan et al., 2015). The findings in this report are critical to assessing the effects of the reforms and should be considered in the context of other evidence from the evaluation research program.

In some respects, the findings in this report should be considered as evidence of emerging effects of the reforms rather than conclusions, as the experiences of the post-reform sample of parents reflect the operation of the reforms in their first two years.

An area where particular challenges arise for research based on population-level quantitative survey methods is in relation to experiences of family violence (see, for example, Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2013). Although this research builds significantly on the existing evidence base in this area through examining experiences and patterns across two separate, cross-sectional datasets of separated parents, and in more detail than has occurred in Australia previously, there are several aspects of the experience of family violence that the methodology applied in this context cannot illuminate. The measures applied in the ESPS study go some way towards establishing prevalence and intensity of family violence in post-separation parenting contexts, but they do not shed light on a range of important questions. These include the dynamics of aggression and defence, which research in clinical samples from the US has shown are important in understanding family violence experiences from the perspective of gender (Hamberger & Larsen, 2015) or on the subjective construction of the experiences, which previous research has indicated vary according to gender (Bagshaw et al., 2010; Hergarty, 2007, p. 11). Hamberger and Larsen (2015) identified gender differences in relation to both physical and emotional violence, including that women appeared to use physical violence in response to violence initiated against them (p. 715).

The SRSP was nevertheless able to capture variations between the effects of physical violence perpetrated by men and women (see, for example, Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) and in patterns in the forms of emotional abuse employed by men and women (Hamberger & Larson, 2015).

1.3 Approach and structure of this report

This report compares the findings of the SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014, particularly highlighting areas where changes in response patterns are evident. The findings of the Court Outcomes Project will provide further insight into the effects of the reforms on parenting arrangement outcomes in court orders by consent or judicial determination. The insights into the experiences of the small proportion of parents nominating court as the main pathway for reaching parenting arrangements in SRSP 2014 will be augmented by the data available from the file analysis in the Court Outcomes Project to provide a more focused view of the effects that the legislative changes have had.

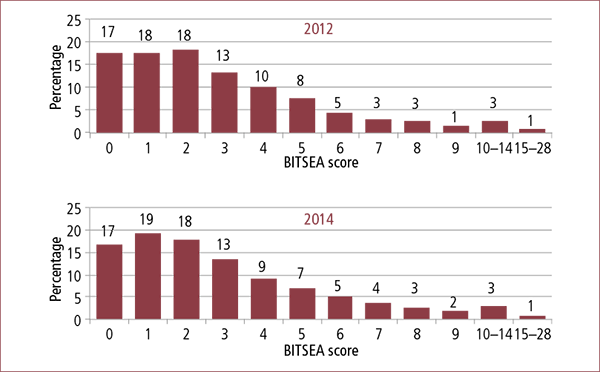

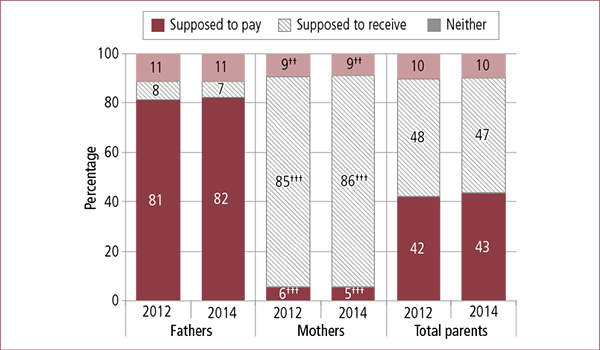

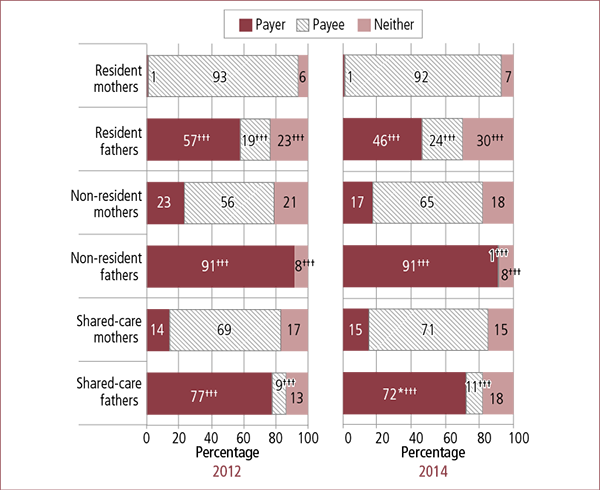

This report has eight further chapters and three appendices. In each chapter, where the findings reported are of statistical significance, this will be identified in the accompanying text. Other data reported, while not reaching a level of statistical significance, are nevertheless important in demonstrating consistencies between the 2012 and 2014 SRSP cohorts, and similarities between gender groups were relevant. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the socio-economic, demographic and family composition characteristics of parents participating in the SRSP 2014. It also includes an examination of parents' relationship dynamics and parenting arrangements in the post-separation context, and an overview of the incidence of family violence among the SRSP 2014 cohort in comparison with the SRSP 2012 and LSSF Wave 1 samples. Chapter 3 focuses on family violence and safety concerns, and examines the incidence, frequency and effects of family violence and safety concerns, both before/during and since separation. The discussion also examines parenting arrangements made by parents who were reporting family violence and ongoing safety concerns. The analysis in Chapter 4 examines patterns in service use by families that have or have not been affected by family violence and ongoing safety concerns. Particular attention is given to the patterns emerging in relation to FDR, legal services and courts. The discussion also considers the status of and pathways engaged in resolving parenting arrangements. Chapter 5 presents findings on parents' reports of disclosure of family violence and safety concerns, and family law system responses. Chapter 6 considers parents' evaluations of the effectiveness of the family law system, and Chapter 7 presents data relating to child and parent wellbeing, with a particular emphasis on the connection between wellbeing and family violence and safety concerns. Chapter 8 presents data relating to child support arrangements as reported by parents in both SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014, including liability for and compliance with paying or receiving child support, together with parents' perceptions about the fairness of their child support arrangements. Chapter 9 summarises the main findings of Chapters 2 to 8.

1 s 60D(2) of the FLA provides that an adviser is: (a) a legal practitioner; or (b) a family counsellor; or (c) a family dispute resolution practitioner; or (d) a family consultant.

2 For example, parents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement: "The family law system addresses family violence". While the distribution of agree and disagree responses were similar between the two cohorts, 19% of parents in 2012 responded with "neither agree nor disagree" and 36% responded with "don't know" (a total of 55% when combined), compared with 4% of parents in 2014 responding with "neither agree nor disagree" and 46% "don't know" (50% when combined).

3 Weighting variables used were participant gender, age group, income, and child support payer type.

This chapter presents the key demographic and family composition characteristics of the parents interviewed for both SRSP 2012 and the SRSP 2014. The discussion first outlines the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of participating mothers and fathers in each cohort. This is followed by a summary of family characteristics prior to separation (e.g., duration of relationship and number of children) and after separation (relationship status, living arrangements). The final section in this chapter provides a summary of post-separation parenting arrangements and reports of participating parents regarding the quality of their family relationships (both with the focus parent and their children).

2.1 Key demographic characteristics of parents

In both the SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014, the samples were primarily comprised of opposite-sex separating couples, with 17 fathers and 31 mothers in the 2014 cohort, and 14 mothers in the 2012 cohort reporting that they had separated from same-sex partners (data not shown).

Table 2.1 shows that the average age of participating parents was 36 years in both the 2012 and the 2014 cohorts, with the average age in the 2014 cohort being 37 years for fathers (cf. 2012: 38 years) and 34 years for mothers (cf. 2012: 35 years). Consistent with the SRSP 2012, the most common age range for separated parents in the SRSP 2014 was 35-44 years, with 38% of participating parents reporting to be in this category, although there were significantly fewer parents in this age range in 2014 compared to 2012 (40%). As noted in the SRSP 2012 final report (De Maio, Kaspiew, Smart, Dunstan, & Moore, 2013, p. 8), this contrasts with the Wave 1 LSSF cohort, where 25-34 years was the most commonly reported age range (Kaspiew et al., 2009, Table 2.1, p. 25).

| Demographic characteristics of participant | Total | Fathers | Mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2014 | 2012 | 2014 | 2012 | 2014 | |

| Notes: Data have been weighted. a Percentages may not total 100.0% due to rounding b Percentages do not sum to 100.0% as multiple responses could be selected. Statistically significant differences between 2012 and 2014 within a given population are noted: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Statistically significant differences between mothers and fathers within a given population (years) are noted: † p < .05; †† p < .01; ††† p < .001. | ||||||

| Age a | ||||||

| Years | Years | Years | Years | Years | Years | |

| Mean age | 36 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 35 | 34 |

| Median age | 36 | 35 | 38 | 37 | 35 | 34 |

| SD | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 8.1 |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| 18-24 years | 10.0 | 11.8 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 12.7 ††† | 14.8 *††† |

| 25-34 years | 33.4 | 34.7 | 30.5 | 32.1 | 36.1 ††† | 37.3 ††† |

| 35-44 years | 40.2 | 37.7 ** | 40.5 | 39.1 | 40.0 | 36.3 **† |

| 45+ years | 16.4 | 15.8 | 21.8 | 20.1 | 11.2 ††† | 11.6 ††† |

| Country of birth a | ||||||

| Australia | 80.4 | 80.2 | 80.0 | 79.3 | 80.8 | 81.1 |

| Other country | 19.6 | 19.8 | 20.0 | 20.7 | 19.2 | 19.2 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status a | ||||||

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 2.7 | 3.5 ** | 2.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.8 |

| Neither | 97.2 | 96.5 | 97.7 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.2 |

| Education a | ||||||

| Bachelor's degree or above | 22.0 | 22.1 | 20.7 | 21.1 | 23.2 † | 23.2 † |

| Other post-secondary qualification (incl. trades etc.) | 29.6 | 31.5 | 30.4 | 30.8 | 28.7 | 32.3 ** |

| Year 12 (no post-secondary qualification) | 21.5 | 20.5 | 20.3 | 19.8 | 22.6 † | 21.3 |

| Year 11 or below | 27.0 | 25.8 | 28.7 | 28.3 | 25.4 †† | 23.2 ††† |

| Employment a | ||||||

| Full-time employed | 47.0 | 46.2 | 75.8 | 73.6 | 20.1 ††† | 19.3 ††† |

| Part-time employed | 24.8 | 24.3 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 39.1 ††† | 38.7 ††† |

| Not employed | 28.2 | 29.5 | 14.7 | 15.7 | 40.8 ††† | 43.0 ††† |

| Current relationship status a | ||||||

| Re-partnered (cohabiting) | 11.0 | 9.6 * | 15.6 | 13.4 * | 6.6 ††† | 5.9 ††† |

| Re-partnered (not cohabiting) | 13.9 | 15.1 | 14.7 | 17.1 * | 13.2 | 13.1 ††† |

| Not partnered | 75.1 | 75.4 | 69.7 | 69.6 | 80.2 ††† | 81.0 ††† |

| Housing tenure a | ||||||

| Own or purchasing | 28.9 | 27.5 | 28.6 | 28.8 | 29.2 | 26.3 **† |

| Private rental | 57.6 | 57.5 | 54.6 | 53.7 | 60.4 ††† | 61.2 ††† |

| Living with family | 7.7 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 6.2 | 7.7 ††† |

| Paying board | 3.9 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 2.8 ††† |

| Other | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| Financial stress since separation b | ||||||

| No financial difficulties | 30.6 | 31.7 | 38.2 | 37.4 | 23.4 ††† | 26.1 *††† |

| Unable to pay bills on time | 38.7 | 36.8 * | 32.5 | 32.8 | 44.5 ††† | 40.8 **††† |

| Unable to pay car registration/insurance on time | 24.2 | 23.9 | 22.9 | 23.3 | 25.6 † | 24.5 |

| Unable to make rent/mortgage payments on time | 22.2 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 21.5 | 23.1 | 20.6 * |

| Unable to heat the home | 11.3 | 10.8 | 9.5 | 8.6 | 13.1 ††† | 12.8 ††† |

| Went without meals | 12.7 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 11.5 †† |

| Had to sell something | 26.4 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 27.3 | 26.1 | 26.4 |

| Sought financial assistance welfare/community group | 19.2 | 19.8 | 11.0 | 12.2 | 27.1 ††† | 27.4 ††† |

| Sought financial assistance from family/friends | 50.0 | 50.1 | 41.6 | 44.2 | 57.9 ††† | 56.0 ††† |

| Experienced periods of homelessness | 7.7 | 7.7 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 6.3 ††† | 6.0 ††† |

| $ | $ | $ | $ | $ | $ | |

| Annual personal income | ||||||

| Mean ($1,000s) | 52.9 | 52.2 | 67.0 | 65.9 | 39.8 ††† | 39.1 ††† |

| Median ($1,000s) | 41.6 | 40.0 | 55.0 | 55.0 | 33.8 ††† | 33.8 ††† |

| SD | 688 | 773 | 1,230 | 1,345 | 580 | 719 |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| Mean ($1,000s) | 61.4 | 57.8 ** | 79.1 | 72.9 ** | 45.9 ††† | 43.1 **††† |

| Median ($1,000s) | 45.0 | 42.8 | 65.0 | 58.0 ** | 36.4 ††† | 35.0 ††† |

| SD | 823 | 914 | 1,436 | 1,605 | 766 | 799 |

| No. of observations | 6,119 | 6,079 | 2,853 | 2,817 | 3,266 | 3,262 |

Four per cent of the 2014 parents reported that they were of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background, in contrast with 3% in the 2012 cohort. This increase was statistically significant.

In relation to educational attainment, 54% of the 2014 parents reported holding a post-secondary qualification (tertiary degree or trade) (cf. 52% in SRSP 2012), with a higher proportion of mothers in the 2014 cohort reporting a non-tertiary degree post-secondary qualification than mothers participating in the SRSP 2012, with this difference also reaching a level of statistical significance.

Table 2.1 also indicates a decrease in parents' reports of full-time and part-time employment, from 72% in the 2012 cohort to 71% in the 2014 cohort, and a consequential increase in reports of unemployment. While a statistically significant higher proportion of fathers were in full-time employment than were mothers (74% cf. 19%), Table 2.1 shows that in the 2014 cohort, the decrease in mothers' reports of employment was greater than that of fathers, compared to the 2012 cohort.

Statistically significant decreases were also identified in parents' reports of cohabiting with their new partners (2012: 11% cf. 2014: 10%), with Table 2.1 showing a more pronounced decrease emerging in fathers' reports on this issue, from 16% in the 2012 cohort to 13% in the 2014 cohort.

Housing tenure was relatively similar across both the 2012 and 2014 cohorts for mothers and fathers. However, there were statistically significant differences between mothers and fathers in housing tenure for almost all categories in 2014 (but not 2012), with private rental being the most common housing arrangement (58% of all parents in 2012 and 2014; 2012 - fathers: 55% and mothers: 60% cf. 2014 - fathers: 54% and mothers: 61%). Parents' reports of owning or purchasing their home remained at less than 30% of participants in the 2014 cohort. A decrease was, however, identified in mothers' reports (2012: 29% cf. 2014: 26%). This remains substantially lower than parents in the general population, with the most recent 2011 Census data indicating that 67% of homes were owned outright or were being purchased (ABS, 2012a). A statistically significant increase in the 2014 (but not 2012) cohort was also identified in reports of parents living with family members (2012 - fathers: 9% and mothers: 6% cf. 2014 - fathers: 11% and mothers: 8%).

Table 2.1 also depicts parents' reports of financial stress since separation and indicates that a majority of parents reported experiencing such hardship. Similar to the 2012 cohort, 32% of parents in the 2014 cohort reported experiencing "no financial difficulties" since separation. While mothers' reports of having "no financial difficulties" increased between 2012 and 2014 to a statistically significant extent (2012: 23% cf. 2014: 26%), the data indicate that mothers' experiences of financial hardship across four of the nine indicators were statistically significantly higher than those of fathers in the 2014 cohort. These four indicators include the inability to pay bills; the inability to heat the home; and the need to seek financial assistance from welfare/community groups, or from family/friends. However, mothers' reports in the 2014 cohort of an inability to pay their bills on time was reduced to a statistically significant extent when compared with mothers' reports in the 2012 cohort (2012: 45% cf. 2014: 24%). Consistent with the SRSP 2012, fathers in the 2014 cohort reported statistically significant higher levels of homelessness (9%) than mothers (6%) Fathers within the 2014 cohort also reported going without meals at a statistically significantly higher rate than mothers.

In relation to reports of annual personal income, fathers in the 2014 cohort reported a statistically significantly higher mean personal income ($65,900) than mothers ($39,100), with this difference being similar to the difference seen in the SRSP 2012, which was also statistically significant. This difference was also reflected in a statistically significant difference between fathers' and mothers' reports of their mean annual household incomes. Overall, however, there was a reduction in the mean annual household income for parents in the 2014 cohort (2012: $61,400 cf. 2014: $57,800). Once again, as noted in the SRSP 2012 final report (De Maio et al., 2013, p. 8), when compared with the most recently available income data based on ABS estimates in 2009-10 (ABS, 2011), the annual household income of parents participating in the SRSP 2014 was lower than the average household income of families with dependent children (including both two-parent and one-parent families), with the latter being $113,200.

Table 2.2 presents the family-level characteristics of separated parents participating in the SRSP 2012 and the SRSP 2014. The data indicate that, consistent with the 2012 cohort, on average, parents in the 2014 cohort had been separated for 17 months at the time of interview. While the majority of parents in the 2014 cohort reported that they had been married at the time of separation (63%), this represented a statistically significant reduction in parents in the 2012 cohort who reported that they had been married (70%). There was, correspondingly, a statistically significant increase in reports of separation from couples who had been in a de facto/cohabitation relationship (2012: 29% cf. 2014: 34%). Consistent with the SRSP 2012, the majority of separated parents in the 2014 cohort reported having one or two children from their relationship.

Table 2.2 also shows that in over one-half of the separated families in both the SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014 cohorts, the father was the parent to leave the family home at the time of separation (2012: 53% and 2014: 52%), while 40% of the mothers left the family home at separation in both cohorts. The remaining sample included 5% where both parents left the family home, and 3% where other arrangements (such as both parents living under the same roof or alternating the family home residence for the children) were made. A statistically significant increase in the reports of these other types of arrangements was seen between the 2012 and 2014 cohorts (2% cf. 3%).

| Family characteristics of participant | 2012 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|

| Notes: Data have been weighted. The "don't know" and "refused" responses for some characteristics were excluded from this analysis (less than 1% each). In cases where both parents of a focus child participated (2012: n = 539; 2014: n = 523), data from one parent were randomly selected for inclusion. a The question was only asked of parents who were married or had lived together before separating (2014: fathers, n = 2,776; mothers, n = 3,198). Percentages may not total 100.0% due to rounding. Statistically significant differences between 2012 and 2014 within a given population are noted: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. | ||

| Duration of separation from focus parent | ||

| Number of months (mean) | 17 | 17 |

| % | % | |

| Marital status at separation | ||

| Married | 69.5 | 63.3 *** |

| Cohabiting | 28.7 | 34.4 *** |

| Not living together | 1.8 | 2.3 |

| Number of children from union | ||

| One | 37.6 | 42.0 |

| Two | 42.3 | 40.7 |

| Three or more | 20.0 | 17.4 *** |

| Who left the house a | ||

| Mother left | 39.9 | 39.8 |

| Father left | 53.4 | 52.2 |

| Both parents left | 5.2 | 5.3 |

| Other arrangement | 1.5 | 2.7 *** |

Table 2.3 presents data on issues that participating parents reported as being pertinent prior to their separation from the focus parent. For each of the issues, a significantly higher proportion of mothers than fathers reported that the issue was relevant to their separation. More than one-third of parents in the 2012 cohort (35%) and the 2014 cohort (39%) reported mental health problems, 25% of parents in both cohorts reported difficulties associated with drug and alcohol use, and almost one-quarter (2012: 23% and 2014: 24%) indicated problems with Internet and social media use. In both cohorts, 10% reported issues with pornography while 7% indicated concerns about gambling.

| 2012 | 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | Total (%) | Fathers (%) | Mothers (%) | |

| Notes: Data have been weighted. Statistically significant differences between 2012 and 2014 within a given population are noted: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Statistically significant differences between mothers and fathers within a given population (years) are noted: † p < .05; †† p < .01; ††† p < .001. | ||||

| Mental health | 35.0 | 39.2 *** | 35.0 | 43.3 ††† |

| Alcohol/drug use | 25.1 | 25.2 | 17.2 | 33.0 ††† |

| Internet/social media use | 23.3 | 24.3 | 22.3 | 26.2 ††† |

| Pornography | 9.6 | 9.5 | 4.4 | 14.4 ††† |

| Gambling | 6.6 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 9.3 ††† |

| No. of observations | 6,119 | 6,079 | 2,817 | 3,262 |

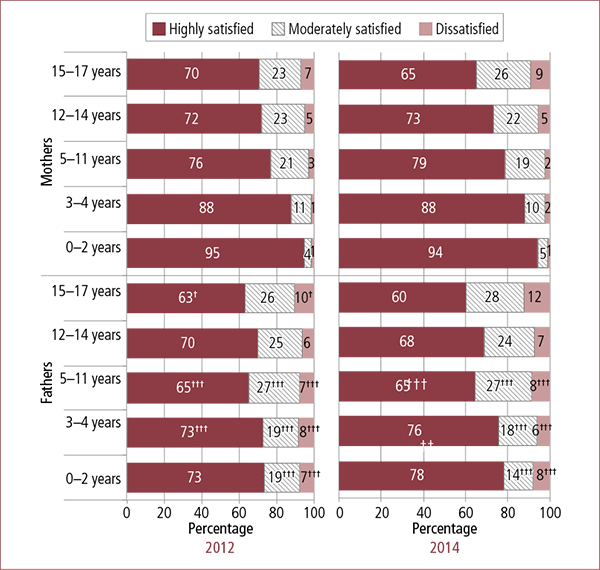

2.1.1 Key characteristics of focus children

Table 2.4 presents data relating to the age and gender of the focus children for both the SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014. In both cohorts, the 5-11 year age group was the largest (2012: 39% cf. 2014: 38%), although the combined 0-2 years and 3-4 years age groups were also substantial (2012: 38% cf. 2014: 42%). The average age of the focus children in both the SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014 was 7 years, and there was a relatively even distribution of boys and girls in both samples (boys - 2012: 51% and 2014: 52%; girls - 2012: 49% and 2014: 48%).

| Characteristics of focus child | 2012 | 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notes: Data have been weighted. In cases where both parents of a focus child participated (2012: n = 539; 2014: n = 523), data from one parent were randomly selected for inclusion. Percentages may not total 100.0% due to rounding. Statistically significant differences between 2012 and 2014 were not found. | ||||

| Age | Years | Years | ||

| Mean age | 7 | 7 | ||

| Median age | 6 | 6 | ||

| N | % | N | % | |

| 0-2 years | 903 | 21.1 | 1,071 | 24.0 |

| 3-4 years | 837 | 17.3 | 869 | 17.7 |

| 5-11 years | 2,223 | 38.6 | 2,184 | 37.7 |

| 12-14 years | 741 | 11.0 | 674 | 10.1 |

| 15-17 years | 876 | 12.0 | 758 | 10.6 |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | 2,880 | 51.2 | 2,859 | 51.9 |

| Girls | 2,700 | 48.8 | 2,697 | 48.1 |

| No. of observations | 5,580 | 100.0 | 5,556 | 100.0 |

2.2 Relationship dynamics and parenting arrangements

This section examines the dynamics of parents' relationships before/during and since separation. It also considers post-separation parenting arrangements relating to both the division of care time and decision-making about the children.

2.2.1 Experience of family violence

By way of context, Table 2.5 presents a comparison between parents' reports of family violence before/during separation from the LSSF Wave 1, SRSP 2012 and SRSP 2014. The data show similar experiences in all three samples of parents, with around 1 in 5 parents reporting physical hurt by their former partner (LSSF: 21%; SRSP 2012 & 2014: 20%), and almost 2 in 5 parents experiencing emotional abuse alone (LSSF: 38%; SRSP 2012: 39%; SRSP 2014: 38%). Parents' reports of experiencing family violence and safety concerns are considered in detail in Chapter 3. In relation to each category of family violence, mothers' reports were higher than those of fathers in all three cohorts.

| LSSF Wave 1 (%) | SRSP 2012 (%) | SRSP 2014 (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | Mothers | Total | Fathers | Mothers | Total | Fathers | Mothers | Total | |

| Notes: Data have been weighted. a Physical hurt includes those who experienced both physical hurt and emotional abuse, given that the majority of parents who experienced physical violence also experienced emotional abuse. For the purposes of comparability between the SRSP and LSSF, experiences of "unwanted sexual activity" have been excluded from the analysis, as this was not asked in LSSF Wave 1. Percentages may not total 100.0% due to rounding. Statistically significant differences between mothers and fathers for each type of violence (SRSP only) are noted: † p < .05; †† p < .01; ††† p < .001. | |||||||||

| Physical hurt a | 16.5 | 25.7 | 21.1 | 15.7 | 23.5 ††† | 19.8 | 16.0 | 22.7 ††† | 19.6 |

| Emotional abuse alone | 36.4 | 39.1 | 37.7 | 40.5 | 37.3 † | 38.9 | 39.7 | 36.9 † | 38.3 |

| No family violence reported | 47.1 | 35.3 | 41.2 | 43.8 | 39.2 ††† | 41.4 | 44.3 | 40.4 †† | 42.4 |

| No. of observations | 4,983 | 5,019 | 10,002 | 2,853 | 3,266 | 6,119 | 2,817 | 3,262 | 6,079 |

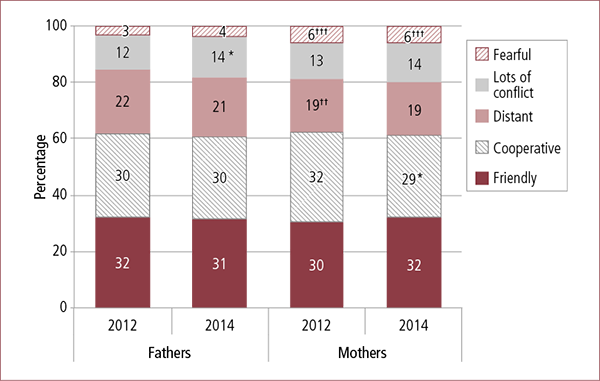

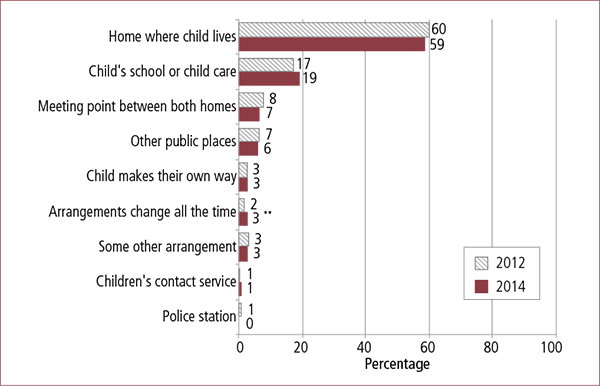

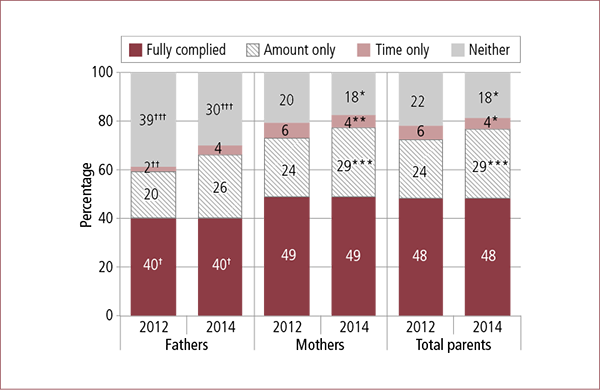

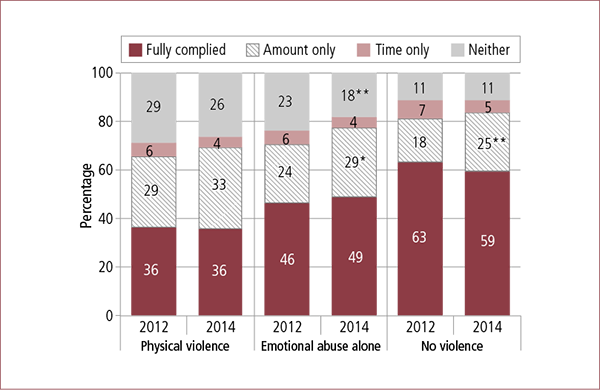

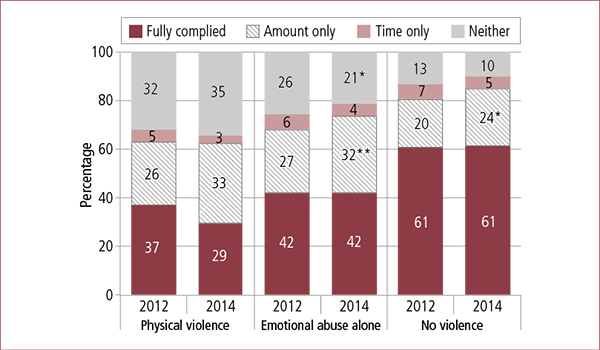

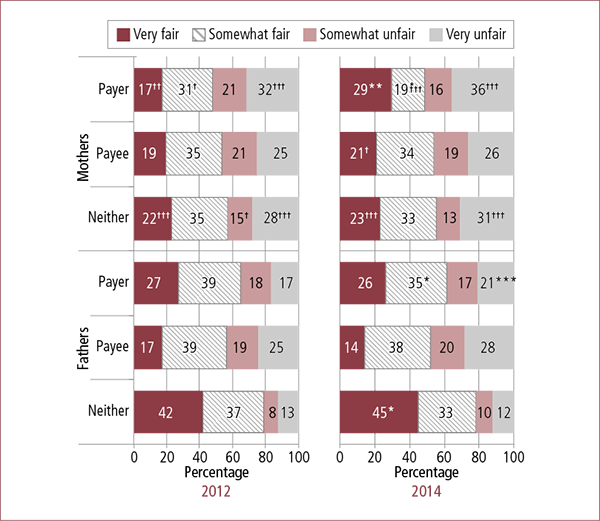

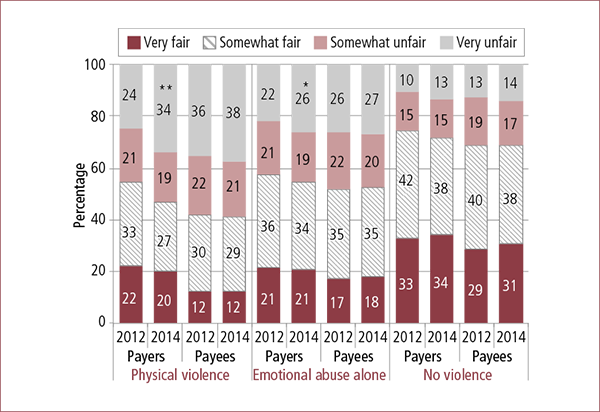

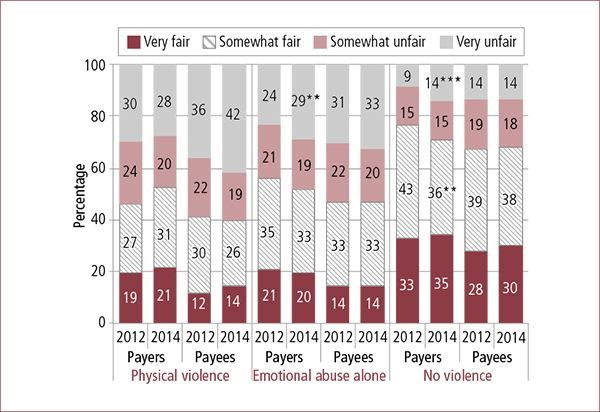

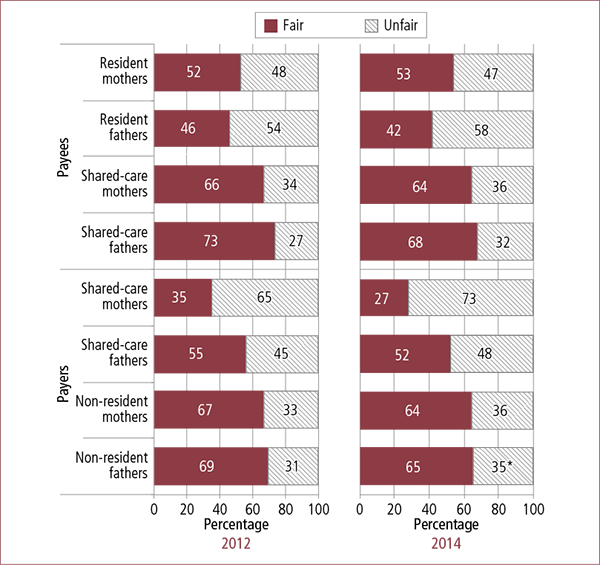

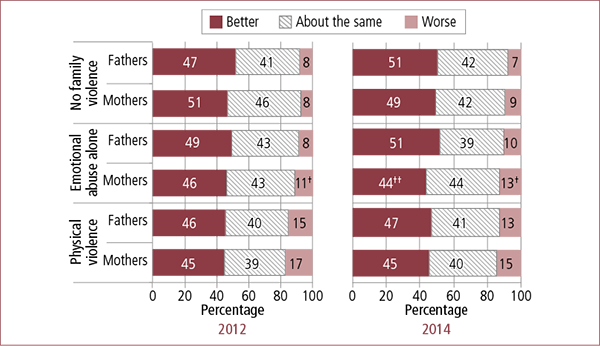

2.2.2 Quality of inter-parental relationship