What promotes social and emotional wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children?

Lessons in measurement from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children

May 2018

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Though social and emotional wellbeing is an important outcome for policy makers in health and education, it is not adequately reflected by mainstream mental health assessment tools - in particular for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. This article aims to identify the early childhood factors associated with later social and emotional wellbeing when the child is ready to start school, and to develop a new indicator that could capture a more holistic view of wellbeing. It draws on data from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children to look at selected individual and family factors during pregnancy and up to 2 years of age compared to children’s prosocial behaviour, mental health, connectedness, and other surrogate proxies for social and emotional wellbeing at school commencement. Though the authors were unable to create a single index of social and emotional wellbeing, the findings highlight the need to apply caution in applying Western biomedical health and wellbeing measures to Indigenous concepts and states.

Social and emotional development and school readiness

In the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC - also known as Footprints in Time) parents' most commonly reported hope for their children was a good education (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, 2009), meaning at least school completion to Year 12, the final year of high school (Department of Social Services, 2011). A smooth transition to school predicts school completion (Huffman et al., 2000), and social and emotional development, which together with cognition and general knowledge, language development and physical wellbeing, is an important factor in children's readiness to participate in school-based learning experiences (Dockett, Perry, & Kearney, 2010).

The Australian Government's Better Start to Life approach invests in maternal, child and family health programs that support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families to ensure children are ready to learn when they start school. To guide programs such as these, it is important to understand the nature and determinants of social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Measuring children's social and emotional wellbeing

Social and emotional wellbeing is central to the holistic view of health held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Department of Health and Ageing, 2013). A broader concept than Western understandings of mental health and wellbeing, the SEWB of an individual is:

… intimately associated with collective wellbeing. It involves harmony in social relationships, in spiritual relationships and in the fundamental relationship with the land and other aspects of the physical environment. (Haswell, Blignault, Fitzpatrick, & Jackson Pulver, 2013, p. 24)

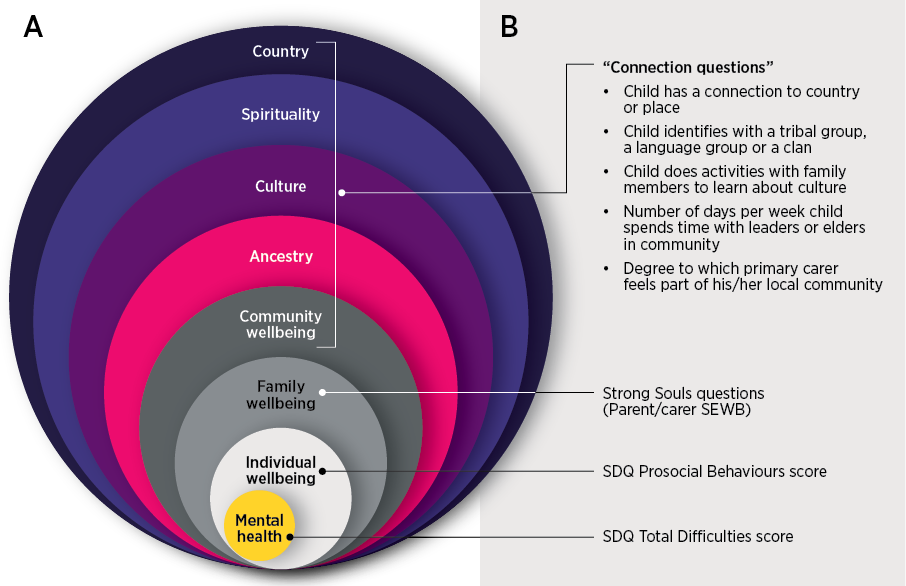

The absence of mental ill health is necessary but not sufficient for SEWB, a positive concept that values relationships (Henderson et al., 2007). The SEWB of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child is dependent upon family and community wellbeing and connection to ancestry, culture, spirituality and country. Mental health is important but not central to the child's SEWB (Figure 1A). Limited quantitative studies indicate that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have significantly higher rates of social and emotional difficulties, mental health problems and psychological distress than non-Indigenous children (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009; Priest, Baxter, & Hayes, 2012; Zubrick et al., 2005).

Figure 1: (A) Conceptual framework for social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children; and (B) variables from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children chosen as outcome measures to operationalise this concept

Note: SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

This disparity is apparent by 3 years of age (Baxter, 2014). Identifying interventions and approaches that promote SEWB will guide policy makers and program managers - particularly those working in the area of maternal and child health.

The Total Difficulties score of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) has been used as a measure of SEWB in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (Li, Jacklyn, Carson, Guthridge, & Measey, 2006; Priest, Baxter, & Hayes, 2012; Priest, Paradies, Gunthorpe, Cairney, & Sayers, 2011; Skelton, 2015; Zubrick et al., 2005). This 25-item questionnaire was designed to assess the "psychological adjustment" of children and adolescents (Goodman, 2001). The SDQ consists of five scales that score emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, peer problems and prosocial behaviour. The first four scales are summed to generate a Total Difficulties score, with a higher score indicating more difficulty. The fifth scale is summed to generate a Prosocial Behaviours score, with a higher score indicating better behaviours. The items and their groupings were selected based on their relationship to categories of mental disorders (Goodman, 2001).

However, mainstream mental health assessment tools such as the SDQ do not adequately reflect SEWB (Henderson et al., 2007). Normal behaviour is culturally constructed and these tools may not account for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societal norms or language (Dingwall & Cairney, 2010). Parents, researchers, youth workers and health workers in Aboriginal communities in Sydney who participated in a study by Williamson and colleagues (2010) indicated that the prosocial scale of the SDQ provides information about an Aboriginal child's relationship with their family that is central to SEWB. These participants indicated that the standard SDQ was acceptable as a measure of mental health but does not assess "connection to or relationship with extended family, Aboriginal identity, feeling that you are accepted by and belong to an Aboriginal community, and the impact and experience of racism" (Williamson et al., 2010, p. 897).

Research aims

In this study, we aimed primarily to identify factors, in utero to 2 years of age, associated with SEWB in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children at the time of starting school. It is at the antenatal stage and in the first two years of life that families generally have the most contact with maternal and child health services, as this is when the majority of immunisations and health and development checks are delivered. A secondary aim was to explore the possibility of developing a new indicator that could capture the holistic concept of SEWB.

Method

We selected a sample of children from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) who were aged 2 years or under at Wave 1, or who entered in Wave 2 aged 3 years or under. The LSIC team have collected data yearly since 2008 (Wave 1). Important features of LSIC include extensive and ongoing community engagement and consultation, and leadership from a steering committee with a majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members (Thurber, Banks, & Banwell, 2015).

There is no instrument available that adequately measures SEWB. As a proxy, we used the two SDQ subscale scores to represent children's prosocial behaviour and mental health. Scores were taken from Wave 6, around the time the children in the sample started school, and were based on the assessment of the primary carer. If these scores were missing, scores obtained from the child's teacher assessment at Wave 5 were used.

We selected early life exposure1 variables from Waves 1 or 2 based on factors found by previous studies to be associated with SDQ scores, factors that have a biologically or socially plausible link to SDQ scores, and factors that reflect the activities or intended outcomes of maternal and child health services (Table 1). We incorporated exposures and potential confounders with a p value of 0.25 or less from univariable analyses into linear regression models. Models were adjusted for the geographic clustering in the LSIC sample.

To address the secondary research aim, we first developed a conceptual framework to represent SEWB in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. This framework guided our selection of variables most closely reflecting the facets of SEWB (Figure 1B). The selected variables were also from around the time of starting school. We used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce these outcome measures to a new index of SEWB. A successful PCA results in a handful of components to which "common sense meanings" can be assigned (Navarro Silvera et al., 2011). Principal components are continuous variables that can be used in analyses in place of the many variables that were used to create them (Navarro Silvera et al., 2011).

All analyses were conducted using StataSE version 13. This research was approved by the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee.

| Variable | LSIC interview question wording or description |

|---|---|

| Mother received first antenatal visit < 20 weeks gestation | How far along [in weeks] [were you/was she] in [your/her] pregnancy when [you/she] had [your/her] first check-up? |

| Mother did not drink alcohol during pregnancy | After finding out you were pregnant with [child's name] did you drink any alcohol during the pregnancy? |

| Mother did not smoke during pregnancy | After finding out you were pregnant with [child's name] did you smoke any cigarettes during the pregnancy? |

| Mother did not use any substances during pregnancy | We aren't after any details here, but after finding out you were pregnant with [child's name] did you use any other substances like smoking marijuana, drinking kava, sniffing petrol, or taking any illicit drugs during the pregnancy? |

| Low birth weight | Can you read out the birth weight from the record book? How much did [child's name] weigh at birth? If primary carer has the baby health book they are asked to read the weight from the book, otherwise they are asked to recall the birth weight. |

| Global health measure | In general, would you say [child's name]'s health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? |

| Not hospitalised in last 12 months | In the last 12 months, did [child's name] stay in hospital because [he/she] was sick, injured or required surgery? |

| Child never had any ear problems | Has [child's name] ever had runny ears/perforated eardrum/hearing loss (total/partial/one ear)/other ear problem? |

| Attends child care, day care or family day care | Does [child's name] go to child care, day care or family day care? |

| Primary carer is employed | Do you have a job? |

| Highest qualification of the primary carer | What was the highest qualification that you have completed? |

| Parental warmth measure (primary carer) | When answering, please say whether you Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, or Never do each thing I ask about:

|

| Stolen Generations | Were you or any of your (or your partner's) relatives removed from your family by welfare or the government or taken away to a mission? |

| Frequency with which family experiences racisma | How often does your family experience racism, discrimination or prejudice? |

| Total number of people living in household | Derived from household survey question: What are the first and last names of all the people who live in this household, starting with you? |

| Number of major life events in previous year | I'd like to ask you about any big things that have happened to you, your family or [child's name] in the last year … [list possible events][maximum 15 events] |

| Number of homes child has lived in since birth | How many homes has [child's name] lived in since he/she was born? |

| Family financial stress | Which words best describe your family's money situation: [1] We run out of money before payday. [2] We are spending more money than we get. [3] We have just enough money to get us through to the next pay. [4] There's some money left over each week but we just spend it. [5] We can save a bit every now and then. [6] We can save a lot. |

| Index of Relative Indigenous Socio-economic Outcomes (IRISEO) | Based on Indigenous Area of child's residential address: 1 = most favourable outcome; 10 = least favourable outcome |

| Level of Relative Isolation (LORI) | Based on geocoding of child's residential address. |

Note: aWave 3 data used.

Source: DSS, 2016

Our research standpoint

Licensed users of LSIC data are required to openly acknowledge their research standpoint (DSS, 2013). We are non-Indigenous Australians with middle-class backgrounds. Following Pyett, Waples-Crowe, and van der Sterren (2008), we have approached the research problem and attempted to interpret the data through a strengths-based lens, and to challenge the deficit model of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Also, by recognising and favouring Indigenous understandings of SEWB, we have used a decolonising approach.

Results

Characteristics of children in the study sample

A total of 950 children from the LSIC cohort met the age eligibility criteria but only 726 of these (76%) had a SDQ Prosocial Behaviours score at endpoint and were included in the sample. Excluded children were more likely to be low birth weight, have a younger and unemployed primary carer, have a mother who smoked while pregnant, and live in a remote or very remote area (Table 2).

Principal components of SEWB

The PCA of the outcome variables (Figure 1B) included data for 444 children (Table 3). Three principal components emerged.2 The first, "Child's connection", comprised variables representing the child's connection to community and country. The second, "Child's helping, sharing and mental health", was constructed from the child's two SDQ scores; while the third, "Primary carer's SEWB factors", was mostly loaded by the primary carer's SEWB score and connection to community. Higher component scores respectively indicate: a stronger connection; greater helping, sharing and mental health; and greater connection and SEWB of the carer.

Early life exposures associated with SEWB components

"Child's connection" component score

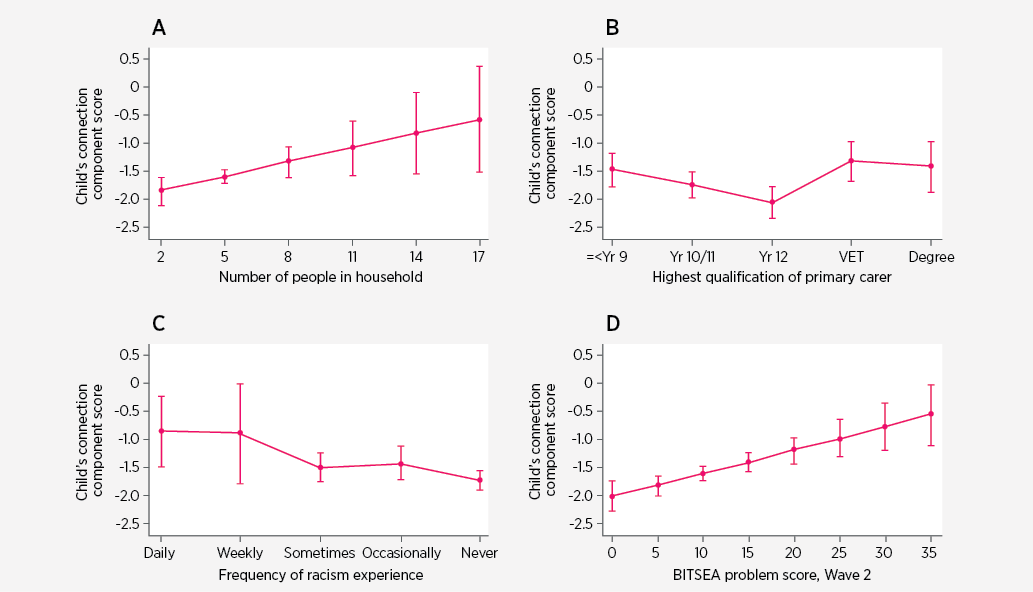

None of the early life exposures were strongly associated with a "Child's connection" component score (Table 4). The regression model predicted a slightly better score for children:

- living in households with 11 or more people, compared with those in two-person households (Figure 2A);

- whose primary carer had less than a Year 10 education, compared with a Year 12 education (Figure 2B; and

- of families that never or hardly ever experienced racism, compared with daily experiences of racism (Figure 2C).

Although experiencing a greater number of major life events was statistically associated with greater connection, the effect was mild. Poorer social and emotional wellbeing at Wave 2 (measured using the Brief Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment [BITSEA] Problem score), which was included in the model as a potential confounder, was also modestly associated with a better score for this component (Figure 2D). A post hoc analysis conducted to check the relationship between this component and SDQ Total Difficulties score showed a moderate positive correlation between these two variables (Spearman's rho = 0.55, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.61, p = 0.00).

| Characteristica | Included in sample % | Excluded from sampleb % | p value for difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 49.6 | 49.1 | 0.90 |

| Low birth weight | 8.0 | 15.1 | 0.01 |

| Mother did not smoke after discovering she was pregnant | 50.9 | 41.1 | 0.02 |

| Mother did not drink alcohol after discovering she was pregnant | 78.7 | 74.1 | 0.17 |

| Very good or excellent general health | 79.5 | 76.2 | 0.30 |

| Primary carer aged < 20 years | 7.0 | 13.0 | < 0.01 |

| Primary carer completed Year 12 | 41.0 | 33.0 | 0.74 |

| Primary carer employed | 30.2 | 17.9 | 0.00 |

| Primary carer parental warmth score (mean, 95% CI) | 4.8 | 4.7 | 0.18 |

| Lived in remote or very remote area | 33.4 | 49.1 | 0.00 |

Notes: a Characteristics with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between groups are shown in bold. b Children of eligible age at baseline were excluded if SDQ Prosocial Behaviours score was missing for Waves 5 and 6.

| Assigned component name | Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child's connection | Child's helping, sharing and mental health | Primary carer's SEWB factors | |

| Eigenvalue | 2.62 | 1.64 | 1.04 |

| Proportion of variance explained | 32% | 18% | 16% |

| Variable loadingsa | |||

| SDQ Prosocial Behaviours score | 0.73 | ||

| SDQ Total Difficulties score | -0.64 | ||

| Child has a connection to country or place | 0.55 | ||

| Child identifies with a tribal group, a language group or a clan | 0.53 | ||

| Child does activities with family members to learn about culture | 0.46 | ||

| Number of days per week child spends time with leaders or elders in community | 0.39 | ||

| Degree to which primary carer feels part of his/her local community | 0.70 | ||

| SEWB of primary carer | 0.65 | ||

| Component scores | |||

| Minimum-maximum | -4.0-2.2 | -13.7-11.6 | 0.6-17.9 |

| Mean (standard deviation) | -1.5 (1.1) | 2.7 (5.0) | 13.3 (3.3) |

Note: a Only loadings greater than 0.2 or less than -0.2 are shown.

Figure 2: Predicted "Child's connection" component scores (with 95% CIs) from linear regression for (A) number of people in the household; (B) highest qualification of the primary carer; (C) frequency with which the family experiences racism; and (D) BITSEA problem score at Wave 2

Note: A higher component score indicates a greater degree of connection.

| Exposurea, b | Adjusted effect size (n = 230) c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Mother did not drink alcohol during pregnancy | -0.22 | -0.55-0.11 | 0.19 | |

| Mother did not smoke during pregnancy | -0.06 | -0.39-0.27 | 0.71 | |

| Mother did not use other substances during pregnancy | 0.19 | -0.35-0.72 | 0.49 | |

| Child never had any ear problems | -0.14 | -0.44-0.15 | 0.33 | |

| Attends child care, day care or family day care | 0.08 | -0.26-0.42 | 0.66 | |

| Primary carer is employed | 0.18 | -0.19-0.55 | 0.34 | |

| Stolen Generations | 0.09 | -0.18-0.35 | 0.51 | |

| Highest qualification of the primary carer | Less than Year 10 Year 10/11 Year 12 VET qualification Bachelor degree or higher | ref. -0.27 -0.56 0.16 0.06 | - -0.61-0.07 -1.02- -0.10 -0.30-0.60 -0.53-0.66 | - 0.12 0.02 0.50 0.83 |

| Parental warmth measure (primary carer) | -0.05 | -0.61-0.52 | 0.87 | |

| Number of people in the household | 0.09 | 0.01-0.16 | 0.03 | |

| Number of major life events in previous year | 0.06 | 0.00-0.12 | <0.05 | |

| Number of homes child has lived in since birth | 0.03 | -0.11-0.16 | 0.71 | |

| Frequency with which family experiences racism | Every day Every week Sometimes Only occasionally Never or hardly ever | ref. -0.03 -0.62 -0.55 -0.86 | - -0.96-0.90 -1.25-0.003 -1.29-0.20 -1.53- -0.18 | - 0.95 0.05 0.15 0.01 |

| Family financial stress | Run out of money before payday Spending more money than we get Have just enough money to get us through to next pay day Some money left over each week but we just spend it Can save a bit every now and then Can save a lot | ref. 0.25 0.27 0.10 0.02 0.22 | - -0.29-1.19 -0.18-0.73 -0.64-0.84 -0.55-0.57 -0.60-1.03 | - 0.59 0.24 0.79 0.96 0.60 |

| IRISEO | -0.04 | -0.11-0.02 | 0.19 | |

| Level of Relative Isolation | None Low Moderate High/Extreme | ref. 0.12 0.51 0.70 | - -0.18-0.43 -0.05-1.07 -0.67-2.07 | - 0.43 0.07 0.31 |

| Brief Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) Competency scored | -0.03 | -0.11-0.05 | 0.50 | |

| BITSEA Problem scored | 0.04 | 0.02-0.06 | 0.00 | |

| Global health measure at time of SDQ assessmentd | Poor/Fair Good/Very good/Excellent | ref. -0.25 | - -0.96-0.46 | - 0.49 |

Notes: CI = Confidence interval. ref. = Reference group. a Variables with p ≤ 0.25 from univariable analysis were included in the regression model.

b Results with p < 0.05 are shown in bold. c Adjusted for 95 clusters. d Potential confounding factor.

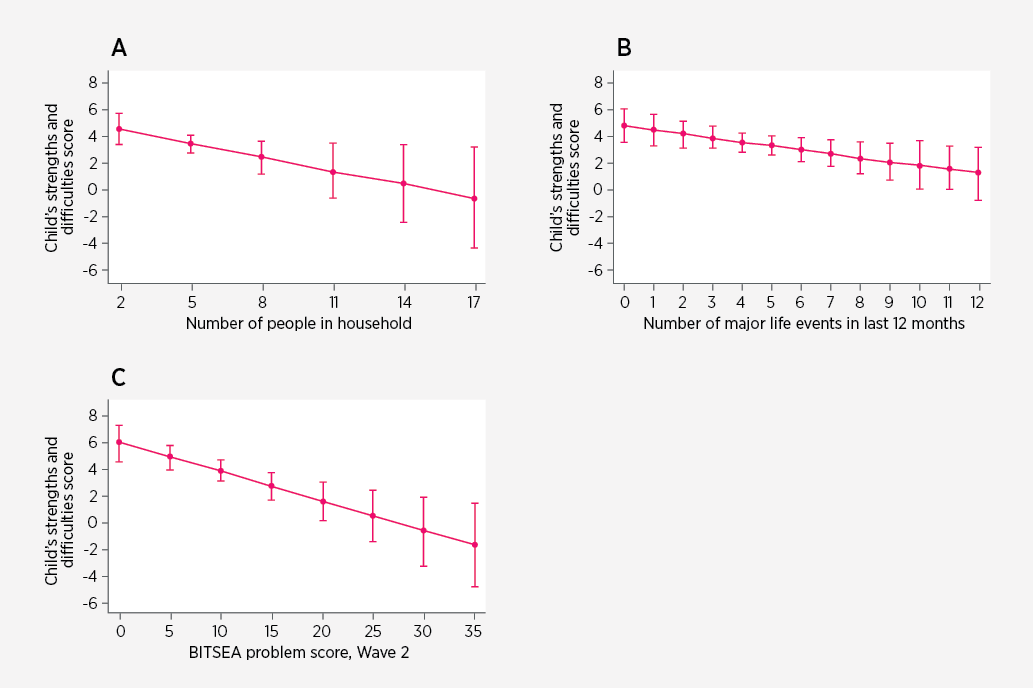

"Child's helping, sharing and mental health" component score

The regression model predicted better scores for children (Table 5):

- living in a household of two people, compared with 11 or more people (Figure 3A); and

- who experienced no major life events, compared with 10 or more events (Figure 3B).

Children with better BITSEA Problem scores at Wave 2 also had slightly better scores for this component (Figure 3C).

| Exposurea, b | Adjusted effect size (n = 230) c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Mother did not drink alcohol during pregnancy | 0.03 | -1.66-1.71 | 0.98 | |

| Mother did not smoke during pregnancy | 1.20 | -0.46-2.86 | 0.15 | |

| Mother did not use other substances during pregnancy | -0.59 | -0.43-1.24 | 0.52 | |

| Low birth weight | -0.90 | -3.08-1.28 | 0.41 | |

| Child not hospitalised in the past 12 months | -0.20 | -1.77-1.37 | 0.80 | |

| Attends child care, day care or family day care | -0.15 | -1.65-1.36 | 0.85 | |

| Excellent, very good or good global health | -1.00 | -6.93-4.92 | 0.74 | |

| Primary carer is employed | -0.27 | -1.87-1.33 | 0.74 | |

| Stolen Generations | -0.11 | -1.56-1.34 | 0.88 | |

| Highest qualification of the primary carer | Less than Year 10 Year 10/11 Year 12 VET qualification Bachelor degree or higher | ref. 1.00 1.81 0.72 1.02 | - -1.45-3.45 -0.55-4.18 -1.77-0.28 -2.72-4.75 | - 0.42 0.13 0.57 0.59 |

| Parental warmth measure (primary carer) | -0.40 | -2.37-1.58 | 0.69 | |

| Number of people in household | -0.33 | -0.63- -0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Number of major life events in previous year | -0.29 | -0.54- -0.04 | 0.02 | |

| Number of homes child has lived in since birth | -0.24 | -0.87-0.35 | 0.45 | |

| IRISEO | -0.16 | -0.45-0.14 | 0.29 | |

| Level of Relative Isolation | None Low Moderate High/Extreme | ref. 0.04 -0.53 -2.27 | - -1.48-0.56 -2.02-1.84 -4.71-0.17 | - 0.96 0.66 0.07 |

| BITSEA Competency scored | 0.12 | -0.20-0.44 | 0.47 | |

| BITSEA Problem scored | -0.22 | -0.34- -0.10 | <0.01 | |

| Femaled | 0.44 | -0.94-1.81 | 0.53 | |

| Age at time of SDQ assessmentd | 0.03 | -0.11-0.16 | 0.81 | |

| Global health measure at time of SDQ assessmentd | Poor/Fair Good/Very good/Excellent | ref. 6.7 | - -0.71-13.25 | - 0.08 |

Notes: CI = Confidence interval, ref. = Reference group. a Variables with p ≤ 0.25 from univariable analysis were included in the regression model. b Results with p < 0.05 are shown in bold. c Adjusted for 95 clusters. d Potential confounding factor.

Figure 3: Predicted "Child's helping, sharing and mental health" component scores from linear regression for (A) number of people in the household; (B) number of major life events in previous year; and (C) BITSEA problem score at Wave 2

Note: A higher component score indicates a greater degree of helping, sharing and mental health.

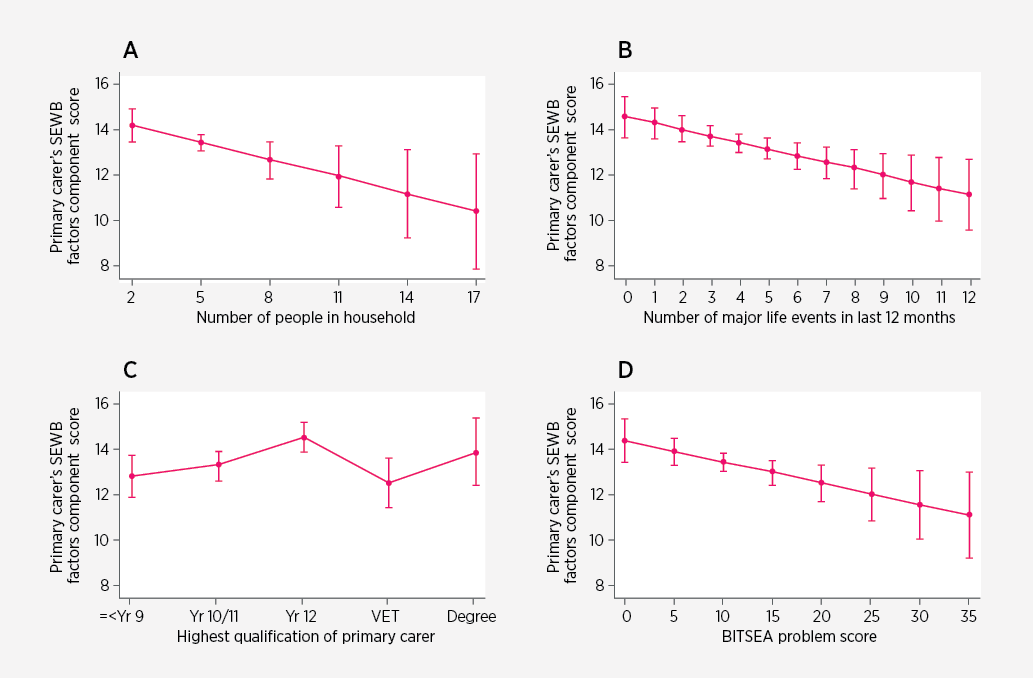

"Primary carer's SEWB factors" component score

Similar results were generated from the regression model for the "Primary carer's SEWB factors" component (Table 6). The model predicted a better component score for children:

- living in a household of two people, compared with 11 or more people (Figure 4A);

- who experienced no major life events, compared with five or more events (Figure 4B; and

- whose primary carer completed Year 12, compared with carer's Year 10 completion (Figure 4C).

Again, the child's BITSEA Problem score at Wave 2 also had a negligible negative correlation with the score (Figure 4D).

| Exposurea, b | Adjusted effect size (n = 230) c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Mother did not drink alcohol during pregnancy | 0.71 | -0.41-1.81 | 0.21 | |

| Mother did not smoke during pregnancy | 0.68 | -0.34-1.70 | 0.19 | |

| Child not hospitalised in the past 12 months | 0.31 | -0.77-1.39 | 0.57 | |

| Primary carer is employed | -0.50 | -1.60-0.59 | 0.36 | |

| Stolen Generations | -0.29 | -1.07-0.49 | 0.46 | |

| Highest qualification of the primary carer | Less than Year 10 Year 10/11 Year 12 VET qualification Bachelor degree or higher | ref. 0.48 1.68 -0.31 1.04 | - -0.53-1.49 0.39-2.97 -1.59-0.98 -0.67-2.75 | - 0.35 0.01 0.64 0.23 |

| Parental warmth measure (primary carer) | 0.31 | -1.11-1.74 | 0.66 | |

| Frequency with which family experiences racism | Every day Every week Sometimes Only occasionally Never or hardly ever | ref. -1.77 1.40 0.41 0.70 | - -3.71-3.35 -1.22-4.02 -2.34-3.16 -1.96-3.35 | - 0.92 0.29 0.77 0.60 |

| Number of people in household | -0.26 | -0.47- -0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Number of major life events in previous year | -0.28 | -0.47- -0.10 | <0.01 | |

| Number of homes child has lived in since birth | -0.002 | -0.40-0.40 | 0.99 | |

| Family financial stress | Run out of money before payday Spending more money than we get Have just enough money to get us through to next payday Some money left over each week but we just spend it Can save a bit every now and then Can save a lot | ref. -1.20 -0.50 -0.41 -0.23 -1.16 | - -3.71-1.31 -1.73-0.73 -2.38-1.55 -1.70-1.25 -3.58-1.25 | - 0.35 0.42 0.68 0.76 0.34 |

| IRISEO | 0.04 | -0.13-0.21 | 0.64 | |

| BITSEA Competency scored | 0.01 | -0.23-0.25 | 0.93 | |

| BITSEA Problem scored | -0.09 | -0.17- -0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Age at time of SDQ assessmentd | -0.05 | -0.14-0.04 | 0.24 | |

| Global health measure at time of SDQ assessmentd | Poor/Fair Good/Very good/Excellent | ref. 2.09 | - 0.03-4.15 | - 0.05 |

Notes: CI = Confidence interval. ref. = Reference group. a Variables with p ≤ 0.25 from univariable analysis were included in the regression model. b Results with p < 0.05 are shown in bold. c Adjusted for 95 clusters. d Potential confounding factor.

Figure 4: Predicted "Primary carer's SEWB factors" component scores from linear regression for (A) number of people in the household; (B) number of major life events in previous 12 months; (C) highest qualification of the primary carer; and (D) BITSEA problem score at Wave 2

Note: A higher component score indicates a greater degree of the primary carer's SEWB.

All regression models were statistically significant overall and did not violate regression assumptions (data not shown). The models explained 20% of the variability in the "Child's connection" component scores, 12% of the variability in the "Child's helping, sharing and mental health" scores, and 18% of the variability in the "Primary carer's SEWB factors" scores.

Discussion

Main findings

Early life exposures associated with surrogate measures of SEWB at school commencement were household size and number of major life events experienced. Larger households and larger numbers of events were associated with reduced sharing, helping and mental health in the child, and poorer wellbeing in the primary carer. Conversely, more people in the household and exposure to more events were weakly associated with greater connection of the child to community, culture and country.

We were unable to create a single index of SEWB using PCA of LSIC data. Surprisingly, post hoc analysis revealed that measures of connectedness and relationship were positively correlated with poorer mental health, as measured by the SDQ Total Difficulties score. This suggests that the score is a poor proxy for SEWB. Those seeking evidence to support SEWB policy development, program planning and evaluation must be cautious in applying Western biomedical health and wellbeing measures to Indigenous concepts and states.

Comparison with other studies - what does this study add?

Exposure to a greater number of major life events in the early years appeared to be mildly detrimental to "Child's helping, sharing and mental health" component scores. In a study of the older LSIC cohort at Wave 4, when the children were aged around 7 years, Skelton and Kikkawa (2013) found a similar strength of association between SDQ Total Difficulties score and exposure to major life events in the previous 12 months. In a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey (WAACHS) for children aged 4-17 years, Zubrick and colleagues (2005) found that exposure to more than seven major life events in the preceding year increased by over fivefold the likelihood of a child being at high risk of clinically significant difficulties (SDQ Total Difficulties score >17), compared with children who experienced two or fewer events.

In the present study, however, experiencing a greater number of events was also associated with greater connectedness to elders, culture and country. It is important to note that, unlike in the WAACHS, not all of the events reported in LSIC are inherently negative. Two of the four most commonly reported events in this sample were pregnancy or a new baby in the household and one of the child's carers returning to work or study. Large, strong family and community networks increase the likelihood of major life events. For example, the larger the network, the more likely friends and relatives will die, the more likely the child will move between households, and the more likely friends and family will give birth.

In this study, having more people living in the household had a negligible positive association with better "Child's connection" component scores. However, an opposite and stronger effect of this exposure was observed for the two other component scores. Similarly, children in the WAACHS living with high household occupancy levels were half as likely to have a high risk SDQ Total Difficulties score, compared with those living with low occupancy. Zubrick and colleagues (2005, p. 144) suggest this "may relate to more help being available within the household, greater flexibility in managing stresses, and greater buffering of risk exposures."

It is not possible to infer household crowding (and related stress) from the number of people reported as living in the household. The LSIC survey question simply asks for the names of "all the people who live in the household" (DSS, 2008), with no clarification about temporary or regular visitors, or people who may sleep elsewhere but use the kitchen and bathroom facilities of the home. In contrast to the WAACHS analysis (Zubrick et al., 2005), we did not calculate household occupancy from the number of bedrooms as well as the number of people who lived in the home. The international standard measure for household utilisation also takes into account the age, sex and relationship status (couples or singles) of occupants (Memmott et al., 2012). However, as Memmott and colleagues (2012) note, it is important to distinguish between a high density of household occupants and household crowding. They argue that crowding is a perception of spatial inadequacy, influenced by a range of factors including the physical setting, an individual's experience and expectations, their relationship to other occupants, and the occupants' activities and behaviour. Crowding is an experience that is culturally defined and, for some families and communities, "[high] density may be an expression of proper intimacy with kin and others, which in fact reduces stress" (Memmott et al., 2012, p. 268).

Previous cross-sectional studies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children of similar ages have found associations between lower SDQ Total Difficulties scores and better general health (Armstrong et al., 2012; Skelton & Kikkawa, 2013); ear health (Zubrick et al., 2005); higher qualification of the primary carer; living in an area of less socio-economic disadvantage (Armstrong et al., 2012) or greater geographic isolation (Zubrick et al., 2005); lower household financial stress (Kikkawa, 2015); having a primary carer who was employed; and living in fewer than four (Williamson et al., 2016) or five homes (Zubrick et al., 2005). In the only published examination of the determinants of better SDQ Prosocial Behaviours score in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, Armstrong and colleagues' (2012) study of the older LSIC cohort found negligible positive effects at Wave 3 for the children who lived in an area of less socio-economic disadvantage at Wave 2. However, none of these factors, occurring in early life, were significant at school entry in this longitudinal study.

The challenge of measuring social and emotional wellbeing

The concept of SEWB cannot be captured using only the SDQ Total Difficulties subscale, the most commonly used measure of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child mental health in large studies. By generating strengths-based outcome measures we have joined Goldfeld, Kvalsvig, Incledon, and O'Connor (2016) in challenging the common assumption that child mental health is the same as the absence of mental illness. These authors argue for a dual continuum model in which mental health is seen as correlated to, but distinct from, mental disorder. However, measuring these two states only will still fail to capture the Indigenous concept of SEWB.

For operationalising SEWB, perhaps what is needed is a "triple continuum model", which includes a domain of relational health of community, culture and country. We could not achieve this by adding the "connection questions" available for this sample of LSIC children, which prima facie cannot quantify a concept that encompasses a rich web of relationships between flourishing individuals, families, language, culture, spirituality and land and sea country.

Taylor (2008, p. 116) names the intersection between Indigenous culture and government reporting frameworks the "recognition space" (Figure 5). This space is:

… where policy makers and Indigenous people can seek to build meaningful engagement and measurement. This is the area that allows for a necessarily reductionist translation of Indigenous people's own perceptions of their wellbeing into measurable indices sought by government. What is captured in this space is obviously far from the totality of Indigenous understandings of wellbeing.

Figure 5: The “recognition space” for indicators of Indigenous wellbeing

Source: (Taylor, 2008)

| Wellbeing themes | Potential indicators |

|---|---|

| Family, identity and relatedness |

|

| Community |

|

| Connection to country |

|

| Connection to culture |

|

| Safety and respect |

|

| Standard of living |

|

| Rights and recognition |

|

| Health |

|

Source: Yap & Yu, 2016

We may feel that by choosing standard measures we are ensuring objectivity. However, Prout (2012) warns that reducing Indigenous notions to narrow conventional indicators is a political exercise. In so doing, this "invisibilises many of the positive, enduring and protective factors associated with Indigenous ways of life which are not amenable to this kind of analysis and reporting" (Prout, 2012, p. 320). Our own values and world views also influence our interpretation of these indicators and may be in conflict with Indigenous perceptions of wellbeing. Prout argues, by using non-Indigenous populations as the reference group we are assuming that equity based on these flawed indicators is the ambition for Indigenous populations.

An alternative approach is offered by the Indigenous quantitative methodologies described by Walter and Andersen (2013). In these methodologies, power is returned to communities by framing research through lenses of Indigenous values, ways of being and of knowing. A recent relevant example is the project auspiced by the Kimberley Institute to develop culturally relevant measures of wellbeing for the Yawuru people, who live in and around Broome (Yap & Yu, 2016). In this qualitative project, Yawuru men and women described their concept of wellbeing and selected relevant indicators to develop gender-specific and collective wellbeing frameworks. Although this example was developed for adults in a specific community, the indicators for collective wellbeing listed in Table 7 highlight the complexity of the wellbeing concept and contrast with the much narrower constructs measured by the SDQ scales.

Strengths of this study

While recognising our world view and social position, we have attempted to use an Indigenous quantitative methodology for this study. Walter and Andersen (2013, p. 83) define this methodology as one in which "the practices and processes of research are conceived and framed through an Indigenous standpoint". We were fortunate to have access to the LSIC data - data that were collected using protocols that exemplify this methodology (Walter & Andersen, 2013). We have also taken advantage of the power of the longitudinal LSIC design.

Limitations of this study

The non-random purposive sampling technique used for LSIC means generalisation of the results of this study to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children requires caution. The characteristics of the children excluded from the sample suggest that we may have underestimated the effects of low birth weight, primary carer employment, remote living and maternal smoking. Similarly, missing exposure data reduced sample size for the regression models, possibly lessening the effect of factors significant in univariable analyses.

Only a little of the variation in outcomes is explained by the regression models presented here. This means either there is a great deal of random variation in the outcome measures chosen or there are other factors that we did not include or consider that determine these outcomes. We were constrained in selection of both outcome and exposure variables by the waves in which certain questions were asked by the LSIC team. Furthermore, as there are no clinical measures or clinical record review in LSIC data collection, there may be considerable measurement error for questions about the child's health and birth weight, depending on the primary carers' recall and health literacy.

Implications

We have been unable to provide strong evidence to guide policy makers on interventions and approaches regarding intrauterine exposures, characteristics of the primary carer, parenting and care arrangements, or macro-level socio-economic indicators that will promote SEWB in children about to start school. However, our findings are consistent with the social determinants theory of SEWB (Henderson et al., 2007) and supportive of holistic, trans-portfolio approaches. The results also provide some evidence for screening and management of infants and toddlers with social and emotional difficulties for prevention of mental health problems later in childhood.

Measuring SEWB of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children for the purposes of policy development, program planning or evaluation is not straightforward. If mainstream measures of mental health are used to plan and evaluate programs, their limitations must be acknowledged. Ideally, communities would be supported to develop their own measures of wellbeing. This presents a challenge: striking a balance between the need to privilege Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies and the governments' requirement to demonstrate investment accountability using indicators that can be applied throughout jurisdictions cost-effectively.

References

Armstrong, S., Buckley, S., Lonsdale, M., Milgate, G., Kneebone, L. B., Cook, L., & Skelton, F. (2012). Starting school: A strengths-based approach towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Canberra: Australian Council for Educational Research. Retrieved from <research.acer.edu.au/indigenous_education/27/>.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2009). A picture of Australia's children 2009. Cat. no. PHE 112. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from <www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=6442459928>.

Baxter, J. (2014). The family circumstances and wellbeing of Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children annual statistical report 2012. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <growingupinaustralia.gov.au/pubs/asr/2012/ch10asr2012.pdf>.

Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2009). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Key summary report from Wave 1. Canberra: FaHCSIA. Retrieved from <dss.gov.au/national-centre-for-longitudinal-data/footprints-in-time-the-longitudinal-study-of-indigenous-children-lsic/key-summary-report-from-wave-1-2009?HTML>.

Department of Health and Ageing. (2013). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-2023. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved from <www.health.gov.au/natsihp>.

Department of Social Services (DSS). (2008). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children - Parent 1 - Wave 1, 2008 Marked-up Questionnaire. Canberra: DSS. Retrieved from <dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/about-fahcsia/publication-articles/footprints/teacher-carer-wave1-questionnaire.pdf>.

DSS. (2011). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Report from Wave 2. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/about-the-department/publications-articles/research-publications/longitudinal-data-initiatives/footprints-in-time-the-longitudinal-study-of-indigenous-children-lsic/key-summary-report-from-wave-2>.

DSS. (2013). Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children data protocols. Canberra: DSS. Retrieved from <dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/09_2016/fact_sheet_6_longitudinal_study_of_indigenous_children_data_protocols_-_accessible_version.pdf>.

DSS. (2016). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children - Data User Guide, Release 7.0. Canberra: DSS. Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/04_2016/data_user_guide_-_release_7.0.pdf>.

Dingwall, K. M., & Cairney, S. (2010). Psychological and cognitive assessment of Indigenous Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(1), 20-30. Retrieved from <journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00048670903393670>.

Dockett S., Perry, B., & Kearney, E. (2010). School readiness: What does it mean for Indigenous children, families, schools and communities? Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from <www.aihw.gov.au/uploadedFiles/ClosingTheGap/Content/Publications/2010/ctg-ip02.pdf>.

Goldfeld, S., Kvalsvig, A., Incledon, E., & O'Connor, M. (2017). Epidemiology of positive mental health in a national census of children at school entry. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(3), 225-231. Retrieved from <jech.bmj.com/content/71/3/225>

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337-1345. Retrieved from <www.jaacap.com/article/S0890-8567%2809%2960543-8/abstract>.

Haswell, M., Blignault, I., Fitzpatrick, S., & Jackson Pulver, L. (2013). The social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous youth: Reviewing and extending the evidence and examining its implications for policy and practice. Sydney: University of NSW. Retrieved from <www2.aifs.gov.au/cfca/knowledgecircle/discussions/children-and-young-people/social-and-emotional-wellbeing-indigenous>.

Henderson, G., Robson, C., Cox, L., Dukes, C., Tsey, K., & Haswell, M. (2007). Social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the broader context of the social determinants of health. In I. Anderson, F. Baum, & M. Bentley (Eds.), Beyond Bandaids: Exploring the underlying social determinants of Aboriginal health (pp. 136-164). Casuarina, NT: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved from <researchonline.jcu.edu.au/2977/>.

Huffman, L. C., Mehlinger, S. L., Kerivan, A. S., Cavanaugh, D. A., Lippitt, J., & Moyo, O. (2000). Off to a good start: Research on the risk factors for early school problems and selected federal policies affecting children's social and emotional development and their readiness for school. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. Retrieved from <eric.ed.gov/?id=ED476378>.

Kikkawa, D. (2015). The impact of multiple disadvantage on children's social and emotional difficulties. Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Report from Wave 5. Canberra: DSS. Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/02_2015/impact_multi_disadvantage_children_social_emotional_difficulties.pdf>.

Li, S., Jacklyn, S., Carson, B., Guthridge, S., & Measey, M.-A. (2006). Growing up in the Territory: Social-emotional wellbeing and learning outcomes. Darwin: Department of Health and Community Services. Retrieved from <digitallibrary.health.nt.gov.au/dspace/bitstream/10137/37/1/growing_up_social_emotional_wellbeing.pdf>.

Memmott, P., Greenop, K., Clarke, A., Go-Sam, C., Birdsall-Jones, C., Harvey-Jones, W., et al. (2012). NATSISS crowding data: What does it assume and how can we challenge the orthodoxy? In B. Hunter & N. Biddle (Eds.), Survey analysis for Indigenous policy in Australia: Social science perspectives (Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy and Research Monograph no. 32). Canberra: ANU E Press. Retrieved from <press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p206931/pdf/ch121.pdf>.

Navarro Silvera, S. A., Mayne, S. T., Risch, H. A., Gammon, M. D., Vaughan, T., Chow, W.-H., et al. (2011). Principal Component Analysis of dietary and lifestyle patterns in relation to risk of subtypes of esophageal and gastric cancer. Annals of Epidemiology<, 21(7), 543-550. Retrieved from <dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.11.019>.

Priest, N., Baxter, J., & Hayes, L. (2012). Social and emotional outcomes of Australian children from Indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36(2), 183-190. Retrieved from <dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00803.x>.

Priest, N. C., Paradies, Y. C., Gunthorpe, W., Cairney, S. J., & Sayers, S. M. (2011). Racism as a determinant of social and emotional wellbeing for Aboriginal Australian youth. Medical Journal of Australia, 194(10), 546-550. Retrieved from <www.mja.com.au/journal/2011/194/10/racism-determinant-social-and-emotional-wellbeing-aboriginal-australian-youth?0=ip_login_no_cache%3D77718273466c3513038934283e645679>.

Prout, S. (2012). Indigenous wellbeing frameworks in Australia and the quest for quantification. Social Indicators Research, 109(2), 317-336. Retrieved from <link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-011-9905-7>.

Pyett, P., Waples-Crowe, P., & van der Sterren, A. (2008). Challenging our own practices in Indigenous health promotion and research. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 19(3), 179-183. Retrieved from <www.publish.csiro.au/he/HE08179>.

Skelton, F. (2015). The effect of maternal age at first birth on vocabulary and social and emotional outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children - Report from Wave 5. Canberra: Department of Social Services. Retrieved from <dss.gov.au/national-centre-for-longitudinal-data/footprints-in-time-the-longitudinal-study-of-indigenous-children-lsic/key-summary-report-from-wave-5>.

Skelton, F., & Kikkawa, D. (2013). Social and emotional wellbeing and learning to read English. Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children - Report from Wave 4. Canberra: DSS. Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/about-the-department/publications-articles/research-publications/longitudinal-data-initiatives/footprints-in-time-the-longitudinal-study-of-indigenous-children-lsic/key-summary-report-from-wave-4>.

Taylor, J. (2008). Indigenous peoples and indicators of wellbeing: Australian perspectives on United Nations global frameworks. Social Indicators Research, 87(1), 111-126. Retrieved from <link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-007-9161-z>.

Thurber, K., Banks, E., & Banwell C. (2015). Cohort profile: Footprints in Time, the Australian Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(3), 1-12. Retrieved from <www.academic.oup.com/ije/article/44/3/789/629102>.

Walter, M., & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press.

Williamson, A., D'Este, C. A., Clapham, K. F., Redman, S., Manton, T., Eades, S., et al. (2016). What are the factors associated with good social and emotional wellbeing amongst Aboriginal children in urban New South Wales, Australia? Phase I findings from the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH). BMJ Open, 6(e011182). Retrieved from <bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/7/e011182?cpetoc=&utm_source=TrendMD&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=BMJOp_TrendMD-1>.

Williamson, A., Redman, S., Dadds, M., Daniels, J., D'Este, C., Raphael, B., et al. (2010). Acceptability of an emotional and behavioural screening tool for children in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services in urban NSW. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(10), 894-900. Retrieved from <journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00048674.2010.489505>.

Yap, M., & Yu, E. (2016). Operationalising the capability approach: Developing culturally relevant indicators of Indigenous wellbeing - an Australian example. Oxford Development Studies, 44(3), 315-331. Retrieved from <www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13600818.2016.1178223>.

Zubrick, S., Silburn, S., Lawrence, D., Mitrou, F., Dalby, R., Blair, E., et al. (2005). The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal children and young people. Perth: Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research. Retrieved from <aboriginal.telethonkids.org.au/kulunga-research-network/waachs/waachs-volume-2>.

Alexandra Marmor is a Master of Philosophy (Applied Epidemiology) Scholar at the National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University and Indigenous Health Division, Australian Government Department of Health. Associate Professor David Harley is Deputy Director, Queensland Centre for Intellectual and Developmental Disability (QCIDD), MRI-UQ, University of Queensland, as well as Visiting Fellow, National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University.

Disclaimer

This article uses unit record data from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC). LSIC was initiated and is funded and managed by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to DSS or the Indigenous people and their communities involved in the study.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families who participated in LSIC. We also thank: Dr Annie Dullow, who posed the policy question that led to this research; Dr Katherine Thurber, who gave advice about using LSIC data; Dr Alice Richardson, who gave statistical advice; Dr Liana Leach, who gave advice about the study design; and Fiona Skelton, Laura Bennetts Kneebone and Debora Kikkawa, DSS, who provided helpful feedback on the data analysis plan.

Alexandra Marmor completed this work while she was a Master of Philosophy (Applied Epidemiology) Scholar on placement at the Australian Government Department of Health, and supported by an Australian Government Research Training Scholarship.