Once bitten twice shy?

Attitudes to repartnering after marriage breakdown

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

August 1991

Abstract

To what extent does marriage breakdown deter parents from wanting to live with a partner? After separation, are people preferring their independence or do they remain predisposed towards those values that led to their first marriage? The author examines the extent of repartnering and views about remarriage in the Institute's follow-up study of divorced people, the Parents and Children after Marriage Breakdown Survey.

To what extent does marriage breakdown deter parents from wanting to live with a partner? After separation, are people preferring their independence or do they remain predisposed towards those values that led to their first marriage? Ruth Weston, AIFS Research Fellow, examines the extent of repartnering and views about remarriage in the Institute's follow-up study of divorced people.

For most people, marriage breakdown is a devastating experience - a process that might seem impossible just before the wedding day, despite the statistics on divorce rates, but perhaps not so the next time around.

The Institute's follow-up study of 523 parents who divorced in 1981 and 1983 in the Melbourne Registry of the Family Court of Australia, highlighted the unhappiness of respondents during the last year of marriage and upon separation. All parents had been married five to 14 years and had two children of this (their first) marriage. The surveys were conducted in 1984, some three to five years after separation, and in 1987.

Parents' average ratings of satisfaction with life before and after separation, and in 1984 and 1987 were reported in a previous issue of Family Matters (Weston 1990). The 1984 survey included questions on how respondents felt in the year before and just after they separated. The overall picture was one of markedly low morale towards the end of the marriage and upon separation, followed by marked improvement by 1984 and little change thereafter.

The difficulties experienced by some respondents around the time of separation are best captured by their comments made in the first interview:

'It's a shattering experience. It's the worst experience I've gone through.' (man)

'I wanted to die originally - my world came to an end.' (man)

'It made me feel more shocked and lonely than I ever imagined anyone could feel.' (woman)

'It was the greatest tragedy of my life.' (woman)

'Divorce is like death but the body is not disposed of.' (man)

'He told me to leave. I was devastated. I had a nervous breakdown.' (woman)

Nevertheless, descriptions of the experience were not always negative. Some found relief in separation, while others focused entirely upon their newfound happiness:

'The divorce has been marvellous because the strain of violence and uncertainty has been removed. Everybody is so much happier now.' (woman)

'I got rid of a lot of hassles. He used to drink a lot.' (woman)

'I've never been happier. I feel like a prisoner let out of prison.' (woman)

'I hung around for ten years until the kids were older. Now life is beautiful.' (man)

Respondents recalled anxieties brought about by the separation, including handling the reactions of children, the former spouse and other relatives, coping with the legal process, difficulties with friendships, the social stigma attached to being separated, and uncertainty about the future. Other disruptions concerned changed living arrangements, loss of a partner and being a lone parent:

'The divorce has forced me to go back now to live with my elderly mother. This is not a satisfactory arrangement, with three generations under one roof.' (woman)

'Although my ex-husband hadn't a lot to do with the discipline of the children, he supported me in all these things. I missed that badly.' (woman)

'The one who remains with the children always lives with the broken marriage.' (woman)

'I still hanker after her in a way, and I find it difficult to accept she has gone for good.' (man)

'It's not having anyone to do anything with that I miss ... someone to share life's experiences with.' (woman)

'I still can't come to grips with not coming home to my children.' (man)

For women, separation often meant drastic falls in financial living standards, for they had lost the main income earning asset of the household (their ex-husband's career) and received relatively little in the way of maintenance payments for children (Harrison and McDonald 1988; Weston 1989).

Whatever the experience, separation or divorce called for great readjustment. As one woman explained:

'It's like someone puts your life in a glass, shakes it up and tips it out on the table. You've got to try to put all the little pieces together and start again.'

In starting again, to what extent was repartnering - and in particular, remarriage - rejected after the difficulties experienced? For many sole mothers, for example, repartnering enables escape from poverty; the difficulties experienced before and immediately after separation may pale into insignificance as some of these sole mothers try to 'make ends meet'.

Repartnering Trends

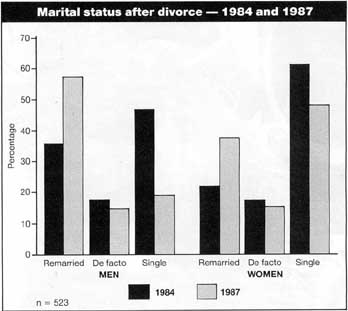

The accompanying Figure shows the marital status of respondents during the two surveys. By 1984, 36 per cent of fathers and 22 per cent of mothers had remarried, while around 17 per cent of parents were living in de facto relationships. In total, more than half the men and nearly 40 per cent of the women were cohabiting in one form or another.

By 1987, 57 per cent of fathers and 38 per cent of mothers had remarried, and another 14 per cent of each group were living in de facto relationships. In other words, 71 per cent of fathers and 52 per cent of mothers were cohabiting. In addition, 9 per cent of fathers and 17 per cent of mothers had an intimate relationship but were not living with this person. Thus, the majority of parents had partners of some sort (80 per cent of men and 69 per cent of women).

People were not slow to remarry - indeed, some may well have initiated the separation in order to marry someone else. Khoo (1989) showed that fathers remarried more quickly than mothers, and that for both sexes, rates of remarriage were highest in the first year after divorce and second highest in the second year. These periods, then, mark the most likely time in which remarriage will take place. Nevertheless, small numbers remarried each year after this.

Khoo also found that those divorced before the age of 35 were more likely to repartner than older divorcees, a trend that was particularly marked for women. Further, those who did not participate in the decision to separate were less likely to have repartnered.

Although less than 20 per cent were in de facto relationships at the time of each survey, 78 per cent of those who had remarried by 1987 said they had lived with their partner before marriage (for an average of 14 months). These living arrangements can have important implications for level of commitment made and for the way the family functions.

For instance, in both surveys, remarried respondents were more likely than those living in de facto relationships to report that they and their partner combined most of their incomes and shared equally in financial decisions concerning large purchases - expressions of commitment that were even more commonly reported for the stage of remarriage investigated than for the period before separation from their former spouse.

Consistent with these behaviours, Peter McDonald, AIFS Deputy Director, Research, wrote in a previous issue of Family Matters (McDonald 1989) that most of those who eventually married the partners with whom they had been living took this step for emotional and symbolic reasons rather than for practical reasons associated with organising finances or because of social pressure.

Most of these men and women considered the traditional view - that marriage represents the symbol of love and commitment to each other - to be a very important reason for their having married their partners. The second most common reason was the security provided by marriage, which more women than men considered very important.

Respondents in de facto relationships or with an intimate relationship but not cohabiting were also asked whether they expected to remarry. McDonald (1989) noted that those in a de facto relationship were more likely than the others to expect to marry, and the de facto people were also more likely to believe that they would marry their current partner.

Those in a relationship who did not expect to marry their current partner (54 per cent of the de facto group and 80 per cent of the non- cohabitating groups) were given a list of possible reasons for not marrying their current partner.

As McDonald explained, the most common reasons were rejection of, wariness or caution about marriage, and the desire to maintain some degree of independence. Compared with the non-cohabiting group, the de facto group was more likely to endorse the first of these reasons and less likely to endorse the second. The respondents who rejected or were cautious of marriage represented only one third of all unmarried respondents with partners.

Finally, most of those without a partner at all said that they would like to marry or at least have an intimate relationship with a new partner (64 per cent). Thirteen per cent said they were uncertain about this, while 23 per cent said they did not wish to repartner at all. Much the same proportions of men and women wanted to remarry or repartner, and much the same proportions expressed uncertainty. The respondents who rejected or were cautious of marriage represented only one-third of all unmarried respondents with partners.

In short, repartnering was the preferred alternative and had been adopted by the majority, with marriage being the most common of the three forms of repartnering examined, typically after some earlier period in a de facto relationship.

Those who lived together before their marriage were likely to view their marriage as a symbol of love and commitment. This was reflected in a greater tendency for married people than those in de facto relationships to combine incomes and share equally in financial decisions.

Although remarriage was the favoured living arrangement, a decrease in rates of marriage and remarriage has been observed in Australia (McDonald 1990) and the United States (Norton & Moorman 1987). McDonald referred to research suggesting that, while people are more inclined to live together and delay marriage, the greater incidence of de facto relationships does not fully account for the decline in the proportion of time people were married between the ages of 20 to 25 years. Further, he showed that the decrease in remarriage rates was apparent with the divorce boom in the 1970s and the downward trend has continued through the 1980s.

One common argument for these trends is that, along with other traditional functions such as economic security and status, marriage is no longer adequately meeting its emotional/procreative function. Some authors, Gove, Style and Hughes (1990) for example, disagree, citing research suggesting that the married tend to be happier than other marital status groups. The relationship between marital status and wellbeing will be examined in a subsequent issue of Family Matters.

References

- Gove, W.R., Style, C.B., and Hughes, M. (1990), 'The effect of marriage on the wellbeing of adults: a theoretical analysis', Journal of Family Issues, Vol.11, pp.4-35.

- Harrison, M. and McDonald, P. (1988), 'Payment of child maintenance in Australia: the current position, research findings and reform proposals' International Journal of Law and the Family, Vol.1, pp.92-132.

- Khoo, S-E. (1989), Repartnering after divorce: the formation of second families. Australian Institute of Family Studies, Child Support Scheme Evaluation Study, Report No.4.

- McDonald, P. (1989), 'The second time around?', Family Matters, No.24, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, August.

- McDonald, P. (1990), 'The 1980s: social and economic change', Family Matters, No.26, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, April.

- Norton, A.J. and Moorman, J.E. (1987), 'Current trends in marriage and divorce among American women', Journal of Marriage and the Family, Vol.49, pp. 3-14.

- Weston, R. (1989), 'Income circumstances of men and women after marriage breakdown: A longitudinal study'. Paper presented at the Australian Institute of Family Studies' Third Australian Family Research Conference, Ballarat College of Advanced Education, 26-29 November.

- Weston, R. (1990), 'How is it going to affect the kids?: parents' views of their children's wellbeing after marriage breakdown', Family Matters, No.27, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, November.