Family trends

A woman's place? Work hour preferences revisited

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Nearly a decade has passed since the report by Glezer and Wolcott on mothers' work hours preferences was published (Work and family values, preferences and practice, 1997). In this article the authors look at whether mothers' preferences have changed during this time. They found that employment rates of mothers with young children have increased, along with a preference for longer hours among those working minimal hours.

Nearly a decade has elapsed since the report by Glezer and Wolcott on mothers' work hours preferences. LIXIA QU AND RUTH WESTON look at whether mothers' preferences changed during this time.

Mid-day Sunday roasts, the "wirelesses", then black-and-white televisions, Elvis, men's "six o'clock swill", fathers as sole providers and mothers as house-proud housewives - these are but a few of the icons of 1950s and 1960s. Fast-forwarding to the 21st Century, Australian family lifestyles are extraordinarily different.

The period of the 1950s and 1960s is often compared with the present era. However, in many ways those earlier decades represent a historical anomaly, with their prosperity, high and secure employment, economic and political stability, early and near universal marriages, and baby boom. Nevertheless, many aspects of family life today are unique in Australia's history. Women's large-scale participation in higher school grades and tertiary education is one example of revolutionary change. Another is the widespread and still expanding work-force participation of mothers, regardless of socio-economic status.

However, it is important to point out that many employed mothers with young children work part-time (fewer than 35 hours per week). Indeed, the most common arrangement for partnered parents with children under the age of 15 years is for fathers to work full-time (35 or more hours per week) and for mothers to work part-time, while the second most common arrangement is the traditional "male breadwinner - female home-maker" model of family life, where the father has a full-time paid job and the mother cares for the family full-time (Wooden 2003).

Of course, the work-hour arrangements of parents that are the most prevalent are not necessarily those considered ideal by their adherents, or those to which others aspire. The arrangements adopted by some parents may represent trade-offs between many forces that may be embraced happily or viewed with mixed feelings. Research by Glezer and Wolcott (1997) suggested that, in the mid-1990s, most mothers with children of pre-school or primary school age preferred to work part-time.

The policy relevance of understanding mothers' work preferences is highlighted by the continuing attention that the Glezer and Wolcott report has received. Most recently, it has been used in the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission's Discussion Paper Striking the Balance (Goward, Milhailuk, Moyle et al. 2005) and in several submissions made to the 2005 House of Representatives Family and Human Services Committee's Inquiry into Balancing Work and Family Life (for example, submissions of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Australian Council of Trade Unions, and the Australian Psychological Society).1

However, almost a decade has elapsed since the survey on which the Glezer and Wolcott report was conducted - the Australian Institute of Family Studies' Australian Life Course Study (ALCS), undertaken in 1996. In the meantime, employment rates of mothers with young children have increased, despite some fluctuations from year to year. For example, between 1996 and 2005, the employment rate of partnered mothers with a child under five years old increased from 46 per cent to 52 per cent, while that of sole mothers with children of this age increased from 26 per cent to 30 per cent. Where the youngest child was five to nine years, the proportions of partnered and sole mothers in paid work increased from 65 per cent to 70 per cent and from 47 to 58 per cent respectively (ABS 2005).

On the other hand, the work hours of employed mothers appear to have declined slightly over this period, although some of these changes may reflect small fluctuating trends. Of employed sole mothers with a child aged under five years, the proportion who worked part-time (rather than full-time) increased from 63 per cent to 72 per cent. There was only a marginal increase in the part-time rate of employed partnered mothers with children of this age (from 67 per cent to 70 per cent) and a slight decrease in the part-time rate of employed mothers whose youngest child was five to nine years (from 62 to 58 per cent for sole mothers, and from 61 per cent to 58 per cent for partnered mothers) (ABS 2005).

Changes in employment rates and work hours may both reflect and influence parents' views about the appropriateness of their seeking paid work, the number of hours that they might work, and their related aspirations. That is, broad community-level changes in lifestyles and attitudes can set the stage for changes in the lifestyles and attitudes of individuals and vice versa.

It is therefore important to monitor both behavioural and attitudinal trends to better inform policies directed towards helping parents to achieve the "balance" between their various parenting responsibilities, including breadwinning, that best suits their own and their children's needs. The third wave of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, conducted in 2003, provides an excellent opportunity for achieving this end.2 The present analysis compares work hours preferences of mothers in wave 3 of the HILDA Survey with those of mothers in the ALCS as reported by Glezer and Wolcott (1997) - surveys that were conducted seven years apart. In addition, the patterns of work hour preferences of partnered mothers and sole mothers who participated in HILDA are compared. (There were too few sole mothers in the ALCS to enable this analysis.)

For simplicity, the ALCS and wave 3 HILDA surveys are henceforth called the "1996 survey" and "2003 survey" respectively. The 1996 survey included 278 mothers with a child under five years old and 305 mothers whose youngest child was five to twelve years, while the 2003 survey included 877 and 974 mothers whose youngest child was under five years and five to twelve years respectively.

The work-hour categories used in the present analysis are the same as those adopted in the Glezer and Wolcott report: 1-14 hours (here called "minimal-hour jobs"); 15-29 hours ("half-time jobs"); 30-34 ("reduced full-time jobs"), and 35 or more hours ("full-time jobs"). These work hours refer to total weekly hours worked across all jobs.

It is important to note at the outset that the 1996 and 2003 surveys differed in terms of both the interview method adopted (telephone interviews were conducted in 1996; face-to-face interviews in 2003) and the questions asked regarding work hours and work hour preferences (see accompanying box on page 74 for details about the different question wording). While such variations may have had some effect on the results outlined below, it seems unlikely that they would fully explain those differences between the 1996 and 2003 results that appeared to be particularly substantial.

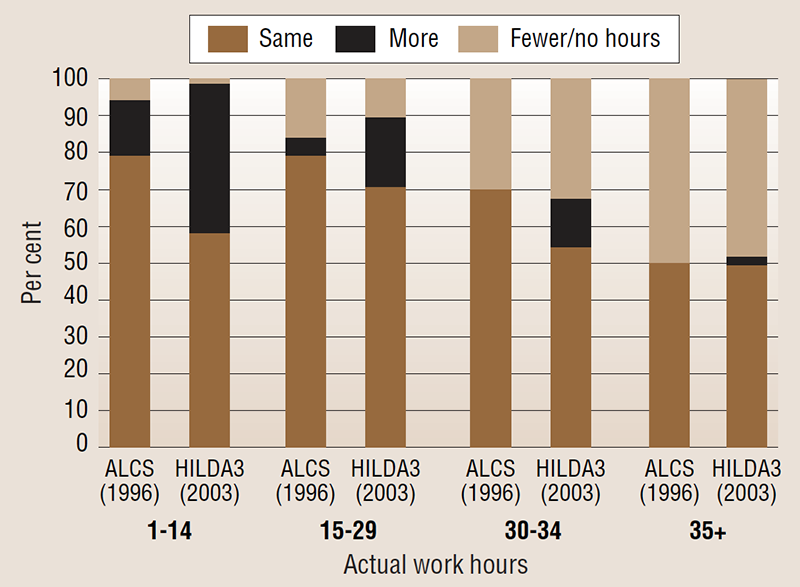

Figure 1. Employed mothers with a child aged 0-4 years: Actual work hours versus preferred work hours

Employed mothers with children under 5 years old: work hour preferences

Figure 1 refers to employed mothers whose youngest child was aged up to four years old. In both survey periods, the mothers who were working less than full-time were the most likely to report that they were happy with their work hours (the question asked in the 1996 survey) or would not choose to change their work hours (the question asked in the 2003 survey) if they were working less than full-time. In both surveys, roughly half the mothers who were working full-time seemed content to continue working these hours, while the other half wanted to work fewer than 35 hours.

On the other hand, the proportion of mothers working 1-14 hours who wanted to work "longer hours" appears to have increased substantially: in 1996, only 15 per cent of mothers who worked these minimal hours said that they would like to increase their work hours, while in 2003, 40 per cent of such mothers indicated this preference. This difference in the proportion of mothers working minimal hours who wanted "longer hours" is unlikely to be fully explained by the variation between the two surveys in the wording of questions tapping work hours and work-hour preferences.

There may have also been a shift towards a desire for "longer hours" amongst mothers who were working 15-29 hours, although such preferences were not commonly expressed in either survey (applying to only 5 per cent in 1996 and 19 per cent in 2003). Of the mothers who worked 30-34 hours, none of those in the 1996 survey and 13 per cent of those in the 2003 survey indicated a desire for more hours of work. It is possible, however, that these differences in results arise from variations in the wording of questions in the two surveys. (As would be expected, few mothers in either survey who worked 35 or more hours expressed any desire for working "longer hours".)

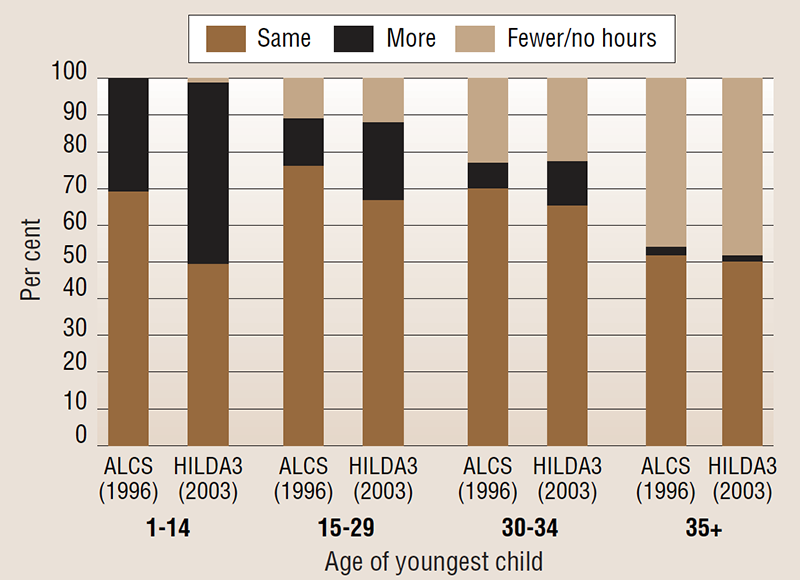

Employed mothers whose youngest child was 5-12 years old

The direction of differences between the two surveys in patterns of work-hour preferences of mothers whose youngest child was five to twelve years (shown in Figure 2) was generally similar to that noted above for mothers with younger children. For most groups with less than full-time work, the proportion expressing a preference for working "longer hours" was higher in the 2003 survey than in the 1996 survey, with the difference being most marked for those working minimal hours (1-14 hours). Of the latter group, 31 per cent in 1996 and 50 per cent in 2003 indicated a preference for "longer hours", while virtually all others with minimal hours wanted to retain their current hours (applying to just over two-thirds of these mothers in 1996 and half in 2003).

Of those working half-time (15-29 hours), the proportion expressing a preference for "longer hours" rose from 13 per cent to 21 per cent, while the proportion wishing to retain their current hours fell from 77 per cent in 1996 to 67 per cent in 2003. Again, such differences amongst mothers working 15-29 seem moderate only and could be due to variations between the two surveys in question wording.

Questions asked about actual and preferred work hours in the two surveys

In relation to actual work hours, respondents in the 1996 ALSC survey were asked to indicate (a) the number of hours they usually worked in an average week in their main job, and (b) the number of hours they worked in any other paid jobs. The 2003 (HILDA) survey adopted the following question: "Including any paid or unpaid overtime, how many hours per week do you usually work in all your jobs?" Those who indicated that their hours of work varied were asked to estimate the average hours they worked.

Specific mention of "overtime" (paid or unpaid) was therefore made in the 2003 survey only. Nevertheless, it appears that paid or unpaid overtime is much more common among full-time workers than others (ABS 2003), and respondents who were working full-time (35 or more hours per week) are represented as a single group in the present analysis. Furthermore, the hours of work reported by part-time workers who take on regular overtime may well include this time, especially if it is paid. Thus, any substantial differences in the broad patterns of results of these two surveys are unlikely to be explained by their different question wording regarding the number of hours worked.

Respondents in the 1996 survey who were asked whether they were "happy" with their hours of work or whether they would prefer to work more hours a week, fewer hours a week, or not at all. In the 2003 survey, respondents in paid work were asked: "If you could choose the number of hours you could work each week, and taking into account how that would affect your income, would you prefer to work fewer hours than you do now, about the same number of hours, or more hours than you do now?"

On the other hand, there was only a very small difference in the proportions of mothers working 30-34 hours who wanted "longer hours" (7 per cent and 12 per cent in the 1996 and 2003 surveys respectively). Similar to the mothers with younger children, roughly half the mothers in each survey who had full-time jobs and a youngest child aged five to twelve years preferred to reduce their work time.

Mothers who were not in paid work

Respondents in the 1996 survey who were not in paid work were asked whether, if given the choice, they would prefer to work full-time, part-time, or not at all. In the 2003 survey, respondents without a job were first asked whether they were looking for paid work and, if they were not doing so, whether they would like a job (response options were "yes", "no", and "maybe"). This variation in question wording for the two surveys may explain patterns of results that are outlined below. Nevertheless, the patterns seem worth recording.

Of the mothers without paid work whose youngest child was under five years old, much the same proportions in the 1996 and 2003 surveys indicated a preference for not working (53-55 per cent). However, the proportion of mothers with older children who indicated such a preference was lower in the 1996 than 2003 survey (35 per cent compared with 43 per cent). Although the response option "maybe" was provided in the 2003 survey, few mothers expressed such uncertainty about their work preferences (that is, 3 per cent of those with children under five years and 7 per cent of those whose youngest child was five to twelve years selected the "maybe" response option). In addition, few mothers in either survey who were not in paid work and whose youngest child was under five or five to twelve years indicated a desire for a full-time job (about 5 per cent in the 1996 survey and 8-10 per cent in the 2003 survey).

Partnered mothers and sole mothers

Given that families headed by sole mothers are amongst the most financially disadvantaged groups in society (McNamara, Lloyd, Toohey and Harding 2004), it might be expected that these mothers would be more likely than partnered mothers to prefer full-time or reduced full-time hours. Paid work may also provide sought-after breaks from caring for the children.

On the other hand, the combination of paid and unpaid work appears to create stronger time pressures for sole mothers than partnered mothers. Bittman (2004) found this to be the case even though the total combination of time sole mothers spent performing both paid (breadwinning) and non-paid aspects of parenting and home-making was less than that reported by partnered mothers. This is understandable, given that sole mothers who do not live with other adults would tend to have little respite from their parenting responsibilities outside any work and school hours - a point noted by Bittman.

The following analysis is based on data from the 2003 (HILDA) survey only because only a small number of sole mothers were represented in the 1996 survey. To increase the size of the sole-mother sample in this analysis, the data for mothers whose youngest child was under five years or five to twelve years were combined. Of this total sample of mothers with a child under thirteen years old, 19 per cent were sole mothers (n=352).

In total, 35 per cent of partnered mothers in this combined sample worked full-time compared with 40 per cent of sole mothers. This pattern is somewhat different from that suggested by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) regarding the work hours of employed mothers (although the trends provided refer to mothers with a child under ten years rather than under thirteen years). According to the ABS (2005), sole mothers with children under ten years were less likely than partnered mothers with children of this age to work full-time in 2003.

Figure 2. Employed mothers whose youngest child was 5-12 years: Actual work hours versus preferred work hours

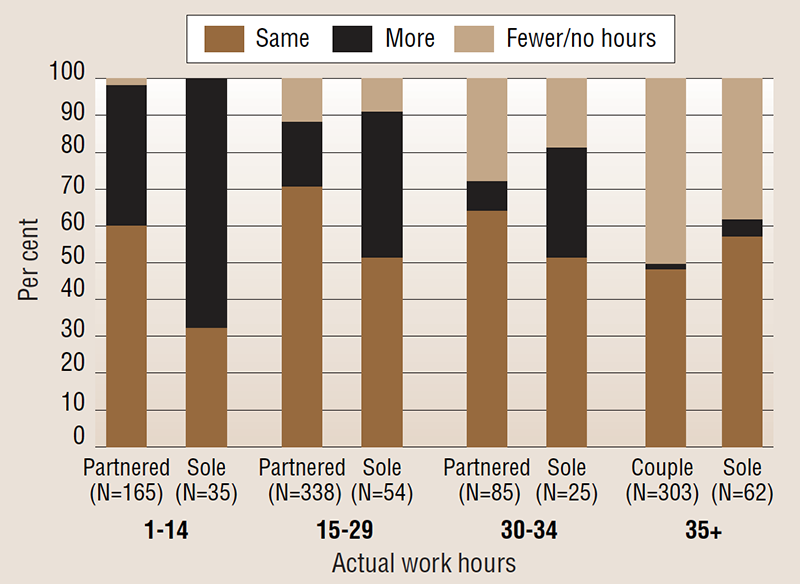

Figure 3. Employed partnered mothers and sole mothers with a child aged under 13 years: actual work hours versus preferred work hours

In the 2003 (HILDA) survey, employed partnered mothers were more likely than sole mothers to work 15-29 hours (that is, "half time": 38 per cent compared with 27 per cent), while similar percentages of employed partnered and sole mothers worked fewer than 15 hours (that is, "minimal hours": 18-21 per cent) or 30-34 hours (that is, "reduced full-time" hours: 10-12 per cent).

Figure 3 suggests that, of the employed, sole mothers were more likely than partnered mothers to prefer to increase their hours of work. This was especially the case for those who were working fewer than 15 hours (68 per cent compared with 38 per cent). Almost all others working minimal hours preferred to retain their current work arrangements. In other words, most sole mothers working these minimal hours wanted to increase their work hours, while most partnered mothers working such hours wanted to retain them.

Of those working half-time (15-29 hours per week), just over half the sole mothers and 71 per cent of the partnered mothers preferred to continue working these hours, while 40 per cent of sole mothers and only 18 per cent of partnered mothers wanted an increase in work hours. And while a sizeable proportion of mothers who worked reduced full-time hours (30-34 hours) wanted to cut down their work hours, this was less the case for sole mothers than for partnered mothers (19 per cent compared with 28 per cent). Thirty per cent of sole mothers and only 8 per cent of partnered mothers who worked reduced full-time hours wanted to increase their work hours, while the sole mothers in this group were less likely than the partnered mothers to wish to retain their current work hours (51 per cent compared with 64 per cent).

In fact, sole mothers were only more likely than partnered mothers to prefer to retain their current work hours if they held full-time jobs (57 per cent compared with 48 per cent indicated this preference). Half the partnered mothers and only 38 per cent of the sole mothers in full-time jobs wanted to cut down their work hours.

The patterns of preferences of sole and partnered mothers who did not have a paid job were consistent with the above trends for mothers in paid work. Sole mothers without paid work were more likely than partnered mothers in this situation to report that they wanted a paid job (66 per cent compared with 38 per cent). Few mothers in either group were uncertain about whether they wanted a job (6 per cent of sole and partnered mothers taken separately selected the "maybe" response option). Furthermore, a higher proportion of sole mothers than partnered mothers without a job wanted to work full-time (17 per cent compared with 7 per cent).

In short, compared with partnered mothers, sole mothers were more likely to want a job if they were not in paid work, or to increase their work hours if they worked part-time.

Summary and conclusions

Glezer and Wolcott (1997) concluded that most mothers whose youngest child is aged under five years or five to twelve years want some paid work (preferably part-time) and that roughly half of those who were working full-time want to work "shorter hours". These conclusions also appeared to hold in 2003 - seven years after the survey on which Glezer and Wolcott's analysis was based (1996). Nevertheless, there seems to have been a marked increase since the 1996 survey in the proportion of mothers working minimal (1-14) hours who want "longer hours" of work, and possibly some increase in the proportion of mothers working half-time (15-29 hours) who hold this preference.

The trends outlined in this article must be considered tentative given the differences between the 1996 and 2003 surveys in mode of data collection and question wording. Nevertheless, they are consistent with a general drive towards increased workforce participation of mothers and, other things being equal, suggest that demands for access to affordable and high quality child care will continue to increase. Overall, the 2003 survey indicated that nearly three quarters of mothers with a child aged under thirteen years would want to be in paid work regardless of their current employment status.

The increased employment rate of mothers, and the apparent shift towards a preference for "longer hours" among those working minimal hours does not necessarily mean that mothers are increasingly embracing such circumstances whole-heartedly. Preferences are often trade-offs. For example, some mothers may wish to enter paid work or increase their current hours of work because doing so is the lesser of two evils, the other being exposing their family to financial difficulties or restricting their children's life chances in other ways. Other mothers who want the same outcomes for their family may derive intrinsic pleasure from the nature of their paid work and/or from the social life it offers.

The impact of breadwinning on families is complex. On the one hand, the more time that is spent in paid work, the less is the time available for "hands on" responsibilities around the home and general interaction with other family members (often called "family life"). As Christiansen and Palkovitz (2001) have noted, the provider role is an essential form of parental involvement in family life, but one that is typically understood as an outcome of the work role rather than as a manifestation of parenting. While these authors restricted their attention to fathers, their arguments apply equally well to mothers in paid work. Indeed, the concept of "balancing work and family life" seems at odds with the notion that both breadwinning and unpaid aspects of parenting are, by definition, essential ingredients of family life. (Of course, not all paid work may be undertaken for the sake of the family, but the same applies to some of the time spent in the home.)

Mothers' entrance into the world of paid work is by no means the only change in family life since the 1950s and 1960s or even before that so-called "golden era". Like other aspects of family life and associated values, such as those concerning pathways to couple formation and parenting, mothers' patterns of work hours and related preferences will continue to evolve. Further increases in their employment rate and work hours seem especially likely given the need for maintaining a sufficient labour supply to support the burgeoning retired population. As McDonald (2004) has noted, the workforce itself is ageing, leaving a strong need for younger workers - in part because of their adeptness in mastering rapidly advancing technology. Women in their late twenties and early thirties (the most common current ages for childbearing) are part of this pool.

However, the key means of curtailing the ageing of the population in the longer term involves boosting the total fertility rate. At present, the average number of children that men and women of childbearing age want is above the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman, while the current fertility rate is below this level (Weston, Qu, Parker and Alexander 2004).

One avenue to help couples to achieve these ambitions and to help mothers participate in paid work without jeopardising non-financial aspects of their children's wellbeing involves fathers taking on a greater share of "hands on", non-discretionary aspects of parenting. Another avenue involves the continuation of adjustments within the workplace and community to accommodate workers with parenting responsibilities, including the provision of increased access to high quality and affordable child care, flexible work hours, and part-time work that does not jeopardise the chance of promotion.

Endnotes

1 Submissions to the 2005 House of Representatives Family and Human Services Committee's Inquiry into Balancing Work and Family Life are available online at www.aph. gov.au/house/committee/fhs/workandfamily/subs.htm.

2 The HILDA survey was initiated, and is being funded, by the Australian Government through the Department of Family and Community Services. It is managed by a consortium led by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne. Other partners in the group are the Australian Council for Educational Research and the Australian Institute of Family Studies. For details of the survey, see HILDA User's Manual - Release 3.0 online at www.melbourneinstitute.com/hilda/doc.html.

References

ABS (2003), Australian Social Trends, Catalogue No. 4102.0, Australia Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

ABS (2005), Labour Force, Australia: Labour Force Status and Other Characteristics of Families (Electronic Delivery), Catalogue No. 6224.0.55.001. Australia Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

Bittman, M. (2004), "Parenting and employment", in N. Folbre and M. Bittman (eds), Family Time: The Social Organisation of Care, Routledge, London.

Christiansen, S. & Palkovitz, R. (2001), "Why the 'Good Provider' role still matters": Providing as a form of paternal involvement, Journal of Family Issues, vol. 22, pp. 84-106.

Glezer, H. & Wolcott, I. (1997), Work and family values, preferences and practice, Australian Family Briefing no. 4, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

Goward, P., Milhailuk, T., Moyle. S., O'Connell, L., de Silva, S. & Tilly, J. (2005), Striking the balance: Women, men, work and family, Discussion Paper, Sex Discrimination Unit, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Canberra.

McDonald, P. (2004), "Implications of low fertility for population futures and related policy options", Paper presented at the Regional Family Policy Forum, Singapore, 25 November.

McNamara, J., Lloyd, R., Toohey, M. & Harding, A. (2004), Prosperity for all? How low-income families have fared in the boom times, Report for the Australian Council of Social Service, Canberra.

Weston, R., Qu, L., Parker, R. & Alexander, M. (2004), "It's not for lack of wanting kids": A report on the Fertility Decision Making Project, Research Report No. 11, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

Wooden, M. (2003), "Balancing work and family at the start of the 21st Century: Evidence from wave 1 of the HILDA survey", Paper presented at the Pursuing Opportunity and Prosperity: the 2003 Melbourne Institute of Economic and Social Outlook Conference, Melbourne, 13-14 November.

Lixia Qu is Demographic Trends Analyst, and Ruth Weston is a Principal Research Fellow and General Manager (Research) at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.