The golden years?

Social isolation among retired men and women in Australia

October 2009

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Social contact beyond partners and co-residents is vital for wellbeing in old age. Besides the obvious benefit to life quality, broader contact with family and friends who live outside the household provides support beyond that available in one’s own household, particularly in circumstances of relationship breakdown or death of a spouse. However, broader social contacts are likely to be disrupted by retirement. Retirement is difficult to define, incorporating aspects such as ending work and gaining more free time for socialising; defining oneself as “retired” and more leisured; and entering a particular “retirement age” where contact with work colleagues is reduced (particularly among men), and more time is spent with partners and peers who are also retired (particularly among women). This paper uses data from the Australian General Social Survey, 2006, and the Australian Time Use Survey, 2006 and finds that retired men spend less time with family and friends outside of the household than men who are not retired. For retired women, the opposite pattern emerges, as they report spending more time with family and friends who live outside of the household compared to women who are not retired.

Social contact in older age is vital for wellbeing. Social isolation is a known risk factor for poor physical health outcomes (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003) and depression (Hawthorne, 2008), and has been directly linked to ageing, in recognition that ageing presents increased risks of ending up alone through death of a spouse (Edelbrock et al., 2001). Certainly, sharing a household with a partner (or other relative/person) in old age greatly reduces the risk of social isolation, as partners and family living in the household are obvious sources of support.

However, links to the broader community of family and friends who live outside the household are important as well. Contact with family and friends outside the household provides additional support beyond that available in the household, and support for times when relationships inside the household are under strain (such as through separation or death of a spouse). Broader social contact, and the key events throughout the life course that disrupt it, are under-studied components of social isolation. One such event is retirement.

Intuitively, the act of retirement represents one of the most important social dislocations in the life course. The Queensland Government Department of Communities (QGDOC, 2007) interim report on reducing social isolation among older people describes retirement as a critical life event in inducing social isolation, and suggests the current focus of retirement preparation on financial planning should be broadened to address social issues. There are, however, no quantitative Australian studies to date that examine the specific effects of retirement on social contact.

A further complicating issue in examining retirement and social contact is the influence of gender. Some reviews (e.g., Russell, 2007) describe the social disadvantages faced by ageing women, while others suggest that it is older men who are more likely to be isolated in Australia (Findlay & Cartwright, 2002; QGDOC, 2007). An important issue in understanding disparities in findings is recognising the different ways of conceiving social isolation (as a feeling or an actual state) and different ways of measuring it, such as recording frequency of social contact (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2007) or duration of time spent with others (Robinson & Godbey, 1997).

This paper will compare retired and non-retired men and women in Australia, in terms of the frequency and duration of social contact with people outside their household.

Social isolation: Retirement, gender and "frequency" versus "duration" of contact

There is a well-established distinction in the literature on social isolation between actual lack of contact with others and social and "emotional" loneliness, which refers to a subjectively perceived lack of contact (Flood, 2005; Green, Richardson, Lago, & Schatten-Jones, 2001; Hawthorne, 2008; Howatt, Iredell, Grenade, Nedwetzky, & Collins, 2004; Van Baarsen, Snijders, Smit, & Duijin, 2001; Weiss, 1982). Many of the recent Australian studies on social isolation have examined perceptions (e.g., Flood, 2005; Hawthorne, 2008). Few studies have examined the actual lack of social contact in Australia beyond basic descriptive analyses (e.g., ABS, 2007), and none in relation to retirement.

Retirement is complex. Smeeding and Quinn (1997) listed several possible definitions, including the end of labour supply, receipt of retirement income, and self-description, but ultimately suggested that retirement should be defined according to the use that is to be made of the term. Others concerned with measuring retirement (e.g., Bowlby, 2007) have agreed that defining it is complex, but have asserted that any definition must capture people of an older age who have generally ceased work.

In a comprehensive review, Weiss (2005) suggested that retirement can be defined according to three approaches. The first two overlap with those suggested by Bowlby (2007): an economic definition, where an older person has ceased work; and a sociological definition, where someone has finished a career and occupies a social niche in which it is socially acceptable to not be working, which can be equated with old age. Weiss also suggested a third definition: psychological, where the person self-identifies as retired. Weiss noted problems with each definition. People who are economically retired may still work part-time or desire further work. Those who are sociologically retired will usually be accepted as such on the basis of age, thereby excluding younger retirees. And those who are psychologically retired may have retired from one job but started another, or continue to work in an informal capacity.

It therefore makes sense to adopt a definition of retirement that incorporates each of these facets of retirement - ending work, reaching a socially acceptable retirement age and perceiving of oneself as retired - so as to include the most appropriate people in the definition. This is discussed in greater detail in the methods section below.

Gender is implicit in many studies of ageing and social isolation. Internationally, Ogg (2005) found that social exclusion, incorporating measures of social isolation, is more prevalent among older women in a range of European countries. Arber, Davidson, & Ginn (2003) found that older UK men have fewer friends, are more socially isolated, are lonelier, and are less likely to have confidantes than older women.

In Australia, women in general perceive that they have greater levels of support, have more friends to confide in, have more contact with family and friends (ABS, 2007) and are less lonely than men (Flood, 2005). Findlay and Cartwright (2002) found a consistent pattern of older men being at greater risk of social isolation, while in a community-based study, Berry, Rodgers, and Dear (2007) found that older women have significantly more contact with friends and extended family than older men. There has been some contradictory evidence, however, with NSW Department of Health data revealing that older men are more likely to visit neighbours at least once a week than older women, consistent across a range of age bands (Centre for Epidemiology and Research, 2006). This highlights the issue of measurement; are measures of frequency of contact sufficient?

Time is an under-used measure of social contact, with no Australian study to date looking explicitly at social contact time among older persons or retirees, and with international studies producing mixed results. Robinson and Godbey (1997) found that older people spend less of their free time socialising, but did not provide details of how they defined "old", whether being "old" is relevant to retirement age and how ageing interacts with gender. Gauthier and Smeeding (2001) examined data from the US, the UK and the Netherlands, and found that after retirement older people re-orient themselves from work to passive activities (watching TV, reading books and similar activities) and not to socialising. Patulny (2007), in comparing socialising time across nine countries, found that being old and being female both negatively predict socialising time in regression analysis. There are limitations with these studies, however. Most use older data (from the 1980s and 1990s) and do not control for the effects of other variables upon social time.

It is also important to look at the effects of marital status in this mix. Single parenthood and relationship breakdown has been associated with increased incidence of perceived social isolation (Flood, 2005) and social exclusion (Saunders, Naidoo, & Griffiths, 2007) in Australia. However, Robinson and Godbey (1997) found that social contact time is less common among persons who are married and parents of young children. More specific examinations of ageing and marital status suggest that those who are old-aged and single are more likely to be socially isolated (Green et al., 2001; Howatt et al., 2004) and socially excluded (Saunders et al., 2007) and less likely to volunteer (Warburton & Cordingley, 2004). Most of these studies focus on women and ageing; there are no Australian quantitative studies into the effects of retirement upon social contact among men of different marital status.

There is a need then to look at recent recall and time use data to examine the links between gender, retirement and social contact. In this paper, regression analysis is used to elucidate how gender and retirement predict social contact (both separately and in interaction), with the results presented by marital status.

Data and methods

Data

Two national datasets were used in this study: the 2006 Australian General Social Survey (GSS) and the 2006 Australian Time Use Survey (TUS), both conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The former asked questions about recalled frequency of contact with others, the latter about duration of time spent in the presence of others.

Operationalising the concept of retirement proved difficult because of the problems noted above in using only one of the definitions provided by Weiss (2005). Defining retirement economically as simply being unemployed or not employed (or not in the labour force, NILF) would result in defining younger people not involved in formal work, such as full-time carers and housewives, as retired when intuitively they are not. Defining retirement sociologically as being part of a retired older (65+ years) community would exclude early retirees and include those who continue to work (formally) past retirement age. And defining retirement psychologically according to respondents' own perceptions was subject to definitional problems. The GSS defined anyone not working or looking for work as "retired", thus conflating psychological and economic definitions. The TUS definition excluded a range of main daily activities: formal work, informal care and housework, and community participation and voluntary activities. It was thus essentially "leisure-centric", and excluded anyone involved in useful or social activities that could characterise retirement in a certain age or the sociologically retired.

In light of these issues, for this study, "retirement" was coded to incorporate aspects of all three definitions. The differences between the GSS and TUS definitions of retirement limited the scope to compare completely integrated definitions, but a comparison based on integrating economic and sociological definitions was possible. Retirement was defined in the GSS (model 1) and the TUS (model 2) as: Anyone aged 65 and over who was not in the labour force. This enabled comparison between these two datasets and their different measures.

In addition, analysis was undertaken on a more complete definition of retirement, established in the TUS (model 3), that integrated all three aspects: Anyone aged 65 and over who was not in the labour force or anyone under the age of 65 who self-defined their main daily activity as "retired".

This definition is still not wholly adequate. It excludes older persons who are psychologically or sociologically retired but work a few hours a week,1 and younger retirees who do not self-define as retired. However, it was the best option available for capturing all the relevant aspects of retirement in this analysis.

An age-restricted subsample was selected for this study. Since the focus of this study is on comparing men and women approaching or passing retirement age, it made sense to remove younger persons (< 45 years), who have very different patterns of social contact from the sample. It also made sense to remove very old people (75+ years) from the sample, to avoid the confounding effects of women outliving men and engaging in greater social contact by default or compensation. Full and age-restricted sample sizes, as well as the number of retired persons by definition, are displayed in Table 1, which shows sufficient sample numbers for the conduct of this study.

The GSS variable used in this study was clearly associated with having face-to-face contact with others: How often have you had face-to-face contact with family or friends that live outside the household?

The variables used from the TUS were constructed from time diaries combining time, presence of others (co-presence) and activity data. The average daily amount of time spent with various others was calculated in minutes, and the main variable calculated in this manner from the TUS was: Time spent with friends/family from outside the household.2

Further variables were calculated to produce, in combination with time spent with family/friends outside the household, a complete set of categories that capture all possible combinations of co-presence. The categories record time spent:

- alone;

- with non-family/friends (colleagues, neighbours, housemates, other people's children);

- with household family (partners, children, relatives); and

- with household family and others (friends, family outside the household, non-family/friends).

| Sample | Dataset | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | GSS (no. of people) | 6,250 | 7,125 | 13,375 |

| TUS (no. of days) | 6,385 | 7,232 | 13,617 | |

| Subsample aged 45-74 years | GSS (no. of people) | 2,763 | 3,070 | 5,833 |

| TUS (no. of days) | 2,845 | 3,114 | 5,959 | |

| Subsample aged 45-74 years, retired persons by definition (models 1-3) | GSS (no. of people) (1) | 443 | 598 | 1,041 |

| TUS (no. of days) (2) | 556 | 713 | 1,269 | |

| TUS (no. of days) (3) | 762 | 861 | 1,623 |

Methods

As an initial examination, weighted frequencies and means for variables are provided in the results section. A series of ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regressions were also conducted on the key variable of contact with family/friends outside the household.3 4

The main independent variables were sex and retirement status, with binary (dummy) variables coded for being male and being retired. Other dummy variable controls were created to allow for the influence of socio-economic/demographic factors. Notable increases in isolation have been identified in specific contexts of social exclusion, such as among those who are socio-economically disadvantaged on the basis of income, employment and education (Hughes & Black, 2002; Saunders et al., 2007; Stone, Gray, & Hughes, 2003). Controls were thus created for level of education, English-speaking ability, disability, income (personal weekly income), unemployment status, and the presence of dependent children still living at home.

Controls for marital status were essential, and were created to separate partnered persons (married or de facto) from those who were living as single, and those who were separated, divorced or widowed. Both these latter groups are likely to differ from partnered persons in terms of greater reliance on social networks outside the household, though those who have experienced separation may suffer a greater likelihood of insufficiency in their social networks, depending on how recent the separation occurred. Categories were omitted to create a reference category representative of an average, middle-class woman - a middle-income, middle-educated, English-speaking female who was married with dependent children living at home, not disabled, not retired, and not unemployed.

In addition to these controls, interaction effects between retirement status and gender were also tested. An interaction effect examines whether two independent variables such as retirement status and gender have a different effect in combination upon the dependent variable (family/friends social time) than they do separately (Jaccard & Turrisi, 2003).5 For example, the presence of an interaction effect between gender (say, being male) and retirement would suggest that being male changes the way in which retirement influences social time in a way that being female does not. In other words, being male and retired has a distinct effect upon social time that cannot be picked up just by controlling for being male or being retired separately.

Results

Descriptive data presents an immediately accessible picture of social contact, and is useful to examine before jumping straight to regression analysis with controls. Weighted frequencies and means for all variables were calculated and are displayed in the tables below.

Descriptive data analysis

Frequency of contact

Table 2 shows the proportion of people in the Australian population aged 45-74 years who engaged in contact with family/friends outside the household on a daily, weekly, or monthly or less basis, from the GSS data. There were only minor differences between retirees and non-retirees in face-to-face contact, with around 17% of persons in either case having face-to-face contact on a daily basis. The main divide was by gender, with a higher proportion of women (18-19%) involved in social contact on a daily basis than men (around 16%).6 This initial glimpse suggests that gender is the more important factor in determining frequency of social contact.

| Non-retirees | Retireesa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | All non-retirees | Male | Female | All retirees | |

| Daily | 15.6 | 18.8 | 17.1 | 16.4 | 17.6 | 17.1 |

| Weekly | 58.1 | 60.7 | 59.3 | 59.7 | 62.5 | 61.3 |

| Monthly or less | 26.3 | 20.4 | 23.6 | 23.9 | 20.0 | 21.6 |

Note: aRetirees are defined as those aged 65+ years and NILF. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Duration of contact

Table 3 shows the average minutes per day spent with family/friends outside the household and with people in other categories, from TUS data. An interaction between gender and retirement in duration of social contact is visible. Men and women spent fairly similar amounts of time with family/friends outside the household before retirement (70 vs 75 minutes per day), but retired men recorded much less time with family/friends outside the household (53 minutes), while retired women recorded much more (103 minutes).

Looking at the remaining categories of co-presence helps explain how the patterns of time spent with family and friends change. Part of the time went to activities that are necessarily not "social", such as committed personal time (e.g., sleeping) and time devoted to care or housework. Despite this, there was still substantial variation in different categories of co-present time between retirees and non-retirees. It would seem that when they retire, men free up time previously devoted to work and spend almost the same amount of time with non-family/friends as retired women (51 vs 45 minutes), while non-retired men spend much more time with non-family/friends (such as work colleagues) than women (3.5 vs 2.5 hours). Given that they work less, retired men should have more free time to spend socially with family/friends outside the household. Instead, retired men reported spending more time with the family with whom they live (wives/partners - an increase from 13 to 15.7 hours); a finding strangely at odds with what women report. There was a very large increase in time spent alone for women who were retired (from 4.2 to 6.4 hours), and while non-retired women spent more time with family members in the household (13.5 hours) than non-retired men (13 hours), this reverses in retirement, with retired men spending a lot more time with family members in the household (15.7 hours) than retired women (12.8 hours).

Thus, retired men report a shift towards spending more time with partners, while at the same time retired women report a shift away from time with partners, and towards spending more time alone and with family/friends outside the household.

| Time spent with (co-presence) | Non-retirees Minutes per dayb | Retireesa Minutes per dayb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | All non-retirees | Male | Female | All retirees | |

| Friends/family outside the household | 70.2 | 75.0 | 72.6 | 53.3 | 102.6 | 79.6 |

| Alone s | 251.9 | 254.1 | 253.0 | 255.5 | 381.4 | 322.6 |

| Non-family/friends (colleagues, neighbours, housemates, other's kids) | 209.0 | 148.6 | 178.8 | 51.3 | 45.1 | 48.0 |

| Household family | 777.6 | 812.7 | 795.1 | 944.1 | 770.3 | 851.5 |

| Household family together with others (friends/family outside the household, non-family/friends) | 111.9 | 137.4 | 124.6 | 123.1 | 124.4 | 123.8 |

Notes: aRetirees are defined as those aged 65+ years and NILF. bEstimates of time spent in co-presence do not add up to 1,440 minutes per day (24 hours) due to the small amount of miscoded or unavailable co-presence data.

Regression analysis

Next we looked at how these results change in regression analysis when controlling for gender and retirement simultaneously. Seven models were run in all, predicting face-to-face contact (models 1-3), and time with family/friends outside the household (models 4-6) with retirement defined just as 65+ and NILF, and an additional TUS regression (model 7) for retirement defined to include under-65 and self-defined. The results of the regression can be seen in Appendix 1.

Frequency of contact

With regards to predicting frequency of face-to-face contact with family/friends outside the household (model 1), being male significantly predicted a reduction in frequency of contact of 0.12 points (on a scale from 1 = none to 6 = daily). There was no change when the interaction term between being male and being retired was introduced (model 2) or when socio-economic/demographic controls were introduced (model 3), although retirement became significant and positive. There were clear and strong effects on social contact of controls associated with disadvantage (income, unemployment) and marital status (separated, divorced, widowed), but these did not change the gender and retirement results.

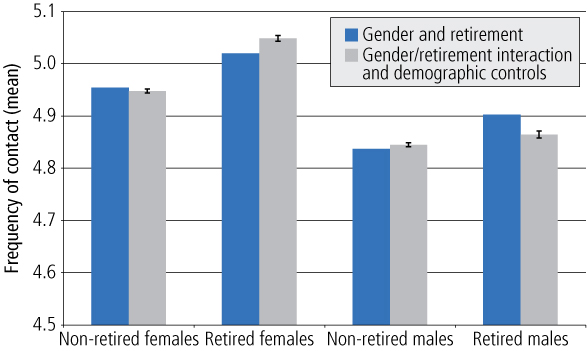

The strong but separate effects of gender (primarily) and retirement status (no interaction) can be seen in Figure 1, which displays mean scores for face-to-face contact predicted from the model. Error bars for each sub-population are included to indicate significant differences, which occur wherever any mean (top of coloured bar) does not overlap with the error bar of any other sub-population.

Figure 1 Face-to-face contact with family/friends outside the household, by gender and retirement, GSS

Notes: Frequency of contact scale: 1 = none, 6 = daily. Retirement is defined as age 65+ years and NILF.

The separate (non-interactive) effects of each variable can be seen in the way that consistent differences in social contact remained between the two genders, and between retirees and non-retirees, even after allowing each of the gender statuses (men and women) to interact with retirement separately in predicting social contact time. In other words, women were always predicted to have more social contact than men, regardless of retirement status, and although the differences between retired and non-retired persons were not as pronounced, retired men and women still had more contact than non-retired men and women respectively. The consistency of these differences is most apparent when only gender and retirement status were controlled for (blue columns), and they remain, despite the differences narrowing, after gender/retirement interaction effects and controls are introduced (grey columns).

Duration of contact

The TUS regressions revealed the strong effect of marital status upon duration of social contact outside the household (discussed further below), but in contrast to the GSS results, an interaction effect between gender and retirement was also present.

Looking just at gender and retirement (model 4), the coefficient for being male predicted a significant decline of 14 minutes per day in time spent with family/friends outside the household, while being retired had no effect in itself; a result similar to the frequency of face-to-face contact regression. However, adding the interaction term (model 5) rendered gender non-significant, while the interaction predicted a significant decrease of over half an hour per day (35 minutes) in social contact. These effects held up when other demographics were controlled for (model 6), although retirement status was no longer significant.

The interaction effect can be seen in Figure 2, where mean scores (and error bars) for time spent with family/friends outside the household are displayed. Before interaction and controls were included (blue columns), there were obvious separate gender and retirement effects similar to those recorded for the GSS analysis above, with men spending less time with family/friends outside the household than women, and retired men and women spending more time than non-retired men and women respectively. However, after interaction and demographics were controlled for (grey columns), substantial differences opened up between retired/non-retired women and retired/non-retired men; retirement affects each gender's social time differently. Retired women recorded a big increase in time spent with family/friends outside the household, while retired men recorded a decrease. The gap between non-retired men and women narrowed considerably (but remained significant).

Figure 2 Amount of time spent with family/friends outside the household, by gender and retirement, TUS

Note: Retirement is defined as age 65+ years and NILF.

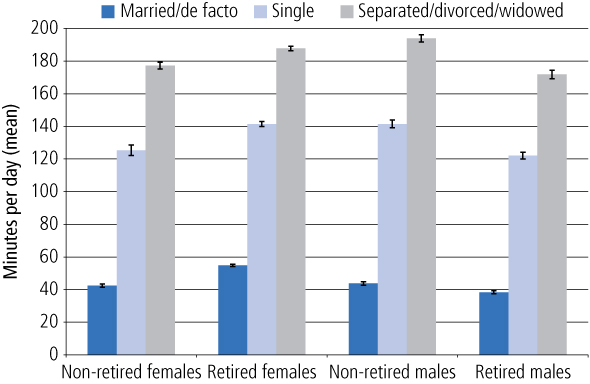

Marital status also had a substantial impact on amount of social contact time. Figure 3 shows mean scores according to whether the respondent was partnered, single, or separated/divorced/widowed. With this analysis limited to the TUS, calculations were made using the full definition of retirement status, including self-defined retirees. Partnered persons spent substantially less time in social contact with family/friends outside the household, while single persons spent considerably more, and separated/divorced/widowed persons spent the most. This is in keeping with the relatively greater support needs associated with not having a partner. A comforting observation is the resilience of those who were separated/divorced/widowed; they showed no sign of lessened social contact with family/friends outside the household in comparison to other groups.

Figure 3 Amount of time spent with family/friends outside the household, by marital status, TUS

Notes: Retirement is defined as age 65+ years and NILF, and < 65 years and self-defined.

Despite the powerful influence of marital status on social contact time, the interaction effect between retirement and gender remained. In all instances, retired men had less time with family/friends outside the household than non-retired men, while retired women had more time with family/friends outside the household than non-retired women. Retired men also had significantly less time with family/friends outside the household, for all marital status groups. The few prominent differences based on marital status were that among those with partners, retired women spent much more time with family/friends outside the household than anyone else; among singles, retired women had similar levels of contact to non-retired men; and among those who were separated/divorced/widowed, non-retired men had the most contact with family/friends outside the household.

This suggests that men rely substantially more than women upon their work-based networks for social contact outside the home, and that retirement has an impact upon this kind of social isolation among men, regardless of their marital status. However, the impact is likely to be more detrimental for single and separated/divorced/widowed men because of their lack of support from partners, family and friends in the household relative to other men and women of similar marital status.

Conclusion

This study set out to examine the levels of social contact among Australian men and women in retirement, comparing frequency and duration of social contact. In looking at frequency of social contact, gender seems to be a more important factor than retirement, in that descriptive and regression analyses show men having less frequent social contact and a greater risk of social isolation than women, whether comparing retired men and women or non-retired men and women.

However, in looking at time spent in contact with family/friends outside the household, the interaction between being male and retired had a greater impact on social time than either variable did separately. Descriptive means show more solitary time spent among retired men and women, more social time spent with family/friends outside the household for retired women, but less social time for retired men. Regressions controlling for the male/retired interaction - or allowing one gender (male) to change the way retirement influences social time differently from the other gender (female) - confirms this pattern, indicating that retired men had less social time than non-retired men, while retired women had more social time than non-retired women. In addition, despite marital status having the largest impact on contact with family/friends outside the household, the negative effect on social contact of the interaction between being male and retired still remains.

Discussion and policy implications

There are certain methodological limitations to this study. The disparity in men's and women's recorded diary time with each other may relate to inaccuracies in recording time, since women show a propensity for better completion of time diaries (Egerton, Fisher, Gershuny, Pollmann, & Torres, 2004). However, this would indicate that men are reporting time spent alone as time spent with family/partner in the household; retired men would therefore still clearly be less social. Another potential problem is the conflation between retirement and age, in that effects attributable to the act of retiring here may simply be a result of getting older; however, the TUS sample does contain some early retirees, and both samples exclude older workers, so the sample here is certainly not synonymous with old age.

A more serious limitation is "omitted variables", or the models not controlling for all appropriate covariates.7 One particular set of controls that are missing are indicators of birth/generational cohort, in that behaviours may be attributable to generational differences (i.e., there may be an antisocial cohort of men), rather than ageing or retirement per se. One way to test this - and to test the actual effect of retiring over time, as opposed to comparing groups of retired and non-retired persons - is to use panel data. However, all Australian time use data is cross-sectional, and cannot observe changes, make causal inferences or control for omitted variables through fixed effects models; such panel studies are beyond the scope of this paper.

Other limitations stem from the definition of retirement. Analyses relating to the GSS exclude all early retirees (under 65), analyses relating to the TUS exclude early retirees who do not self-define as retired, and all analyses exclude retirees over 65 who work a few hours a week or are looking for work. Excluding early retirees and "late workers" may depress the social activity of the retired sample, in that early retirees are more likely to have retired for lifestyle (social) reasons, while late workers will retain social contacts with colleagues. On the other hand, however, early retirees may miss out on socialising with a "retired community", and late workers may lose time for socialising with continued involvement in work. These limitations cannot be tested with the present data.

Regardless of causal and definitional issues, however, the present findings suggest substantive issues exist concerning social isolation and exclusion among older, non-working, retired men. A brief review of the intervention literature suggests possible responses. Findlay and Cartwright (2002) noted that early intervention support groups and structured group interventions have had some success in reducing social isolation, along with linking young families and isolated older persons, setting up community-based common projects, "gate-keeper" projects to identify at-risk older people, and old-young home-share programs. In a review of interventions evaluated using control-group methods, Cattan, White, Bond, and Learmouth (2005) found that programs such as education, counselling, self-help and hobby (self-activation) groups in community centres produced significant improvements in social contact. Mentoring, volunteering, education on social isolation on health, targeted activity groups, transport and centralising service delivery have also been suggested as important techniques in reducing social isolation (QGDOC, 2007). These and similar initiatives should be considered with regard to their specific application to men post-retirement in Australia.

Endnotes

1. It was possible to include more of these people by adopting a "minimum" number of hours worked per week as an indicator of non-attachment to the workforce (and retirement). However, choosing a "minimum" cut-off was problematic, and exclusion of these few persons for the sake of definitional simplicity seemed a better option.

2. Friends/family outside the household only, with no household family or non-family/friends present.

3. OLS regression was the most appropriate method, given that the dependent variable in each instance was measured on a continuous, interval metric. The GSS variable was a limited range scale from 1 to 6 points, but the distribution was close to normal, making OLS an appropriate method. OLS was also used instead of Tobit for the TUS data because it is considered to be more appropriate in any instance where the "zeros" - that is, no social activity recorded that day - are meaningful data (Gershuny & Egerton, 2006). The lack of any social time is relevant to this study, because the focus was on examining the average duration of daily social contact across the whole age-specific population.

4. The TUS analysis also corrected for clustering of people within the sample, as each person completed two days' worth of diaries.

5. Interaction effects test the compound effect of two differences on the dependent variable; in this case, the difference in time spent with family/friends between men and women who are retired (difference 1), and the difference in time spent with family/friends between men and women who are not retired (difference 2); or the effect of switching from being neither male nor retired to being both male and retired.

6. Rates of contact were also calculated for non-face-to-face contact - through email, phone, mail - and for total contact with family and friends outside the household. Although rates of this type of contact were higher, a matching pattern across gender and retirement appeared for these alternative measures.

7. The models generally have low r-square values, suggesting limited explanatory power and potentially numerous omitted variables. However, the inclusion of the most appropriate controls to impact on social contact time suggests that additional controls are unlikely to change the observed relationship between retirement, gender and social contact.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). General Social Survey: Summary of results, 2006 (Cat. No. 4159.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Arber, S., Davidson, K., & Ginn, J. (2003). Changing approaches to gender and later life. In S. Arber, K. Davidson, & J. Ginn (Eds.), Gender and ageing: Changing roles and relationships (pp. 1-4). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Berry, H., Rodgers, B., & Dear, K. B. G. (2007). Preliminary development and validation of an Australian community participation questionnaire: Types of participation and associations with distress in a coastal community. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 1719-1737.

- Bowlby, G. (2007). Defining retirement (Perspectives on Labour and Income, Vol. 8, No. 2; Cat. No. 75-001-XIE). Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2003). Social isolation and health. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46.3(Suppl.), S39-S52.

- Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., & Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: A systematic review of health promotion interventions. Aging and Society, 25, 41-67.

- Centre for Epidemiology and Research. (2006). New South Wales Population Health Survey: 2005 report on adult health. Sydney: Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health.

- Edelbrock, D., Buys, L. R., Waite, L. M., Grayson, D. D., Broe, A. G., & Creasey, H. (2001). Characteristics of social support in a community-living sample of older people: The Sydney Older Persons Study. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 20(4), 173-178.

- Egerton, M., Fisher, K., Gershuny, J., Pollmann, A., & Torres, N. (2005). US historical time use data file production: Report on activities, February to October 2004. Report to the Glaser Progress Foundation. Essex: Institute for Social and Economic Research.

- Findlay, R., & Cartwright, C. (2002). Social isolation & older people: A literature review. Brisbane: Australasian Centre on Ageing, University of Queensland.

- Flood, M. (2005). Mapping loneliness in Australia (Discussion Paper No. 76). Canberra: The Australia Institute

- Gauthier, A. H., & Smeeding, T.(2001). Historical trends in the patterns of time use of older adults. Paris: OECD. Retrieved 10 March 2009, from <www.oecd.org/dataoecd/21/5/2430978.pdf>.

- Gershuny, J., & Egerton, M. (2006, 16-18 August). Evidence on participation and participants' time from day- and week-long diaries: Implications for modelling time use. Paper presented at the 28th International Association of Time Use Researchers Conference, Copenhagen.

- Green, L. R., Richardson, D. S., Lago, T., & Schatten-Jones, E. C. (2001). Network correlates of social and emotional loneliness in young and older adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(3), 281-288.

- Hawthorne, G. (2008). Perceived social isolation in a community sample: Its prevalence and correlates with aspects of peoples' lives. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(2), 140-150.

- Howatt, P., Iredell, H., Grenade, L., Nedwetzky, A., & Collins, J. (2004). Reducing social isolation amongst older people: Implications for health professionals. Geriaction, 22(1), 13-20.

- Hughes, P., & Black, A. (2002). The impact of various personal and social characteristics on volunteering. Australian Journal of Volunteering, 7, 59-69.

- Jaccard, J. J., & Turrisi, R. (2003). Interaction effects in multiple regression (2nd Ed.) (Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences No. 07-072). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ogg, J. (2005). Social exclusion and insecurity among older Europeans: The influence of welfare regimes. Ageing & Society, 25, 69-90.

- Patulny, R. (2007). Society building: Welfare, time and social capital. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

- Queensland Government Department of Communities. (2007). Cross government project to reduce social isolation of older people: Interim Report. Project Phases One to Three. Brisbane: QGDOC.

- Robinson, J. P., & Godbey, G. (1997). Time for life: The surprising ways Americans use their time. University Park: Pennsylvania State University.

- Russell, C. (2007). Gender and ageing. In A. Borowski, S. Encel, & E. Ozanne (Eds.), Longevity and social change in Australia (pp. 99-116). Sydney: UNSW Press.

- Saunders, P., Naidoo, Y., & Griffiths, M. (2007). Towards new indicators of disadvantage: Deprivation and social exclusion in Australia (SPRC Report No. 12/07). Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre.

- Smeeding, T. M., & Quinn, J. F. (1997, 15-17 June). Cross-national patterns of labor force withdrawal. Paper presented at the Fourth International Research Seminar of the Foundation for International Studies on Social Security, Sigtuna, Sweden.

- Stone, W., Gray, M., & Hughes, J. (2003). Social capital at work: How family, friends and civic ties relate to labour market outcomes (Research Paper No. 31). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Van Baarsen, B., Snijders, T. A. B., Smit, J. H., & Duijn, M. A. J. (2001). Lonely but not alone: Emotional isolation and social isolation as two distinct dimensions of loneliness in older people. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(1), 119-135.

- Warburton, J., & Cordingley, S. (2004). The contemporary challenges of volunteering in an ageing Australia. Australian Journal on Volunteering, 9(2), 67-74.

- Weiss, R. S. (1982). Issues in the study of loneliness. In L. Peplua, & D. Perlmen (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons

- Weiss, R. S. (2005). The experience of retirement. New York: Cornell University Press.

Appendix

| DV=> | Face-to-face contact with friends/family outside the household (scale 1-6) | Time spent with friends/family outside the household (min./day) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65+ and NILF retiree | 65+ and NILF retiree | Self-defined retiree | |||||

| Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Adj R2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .001 | .003 | .090 | .070 |

| Intercept | 4.95*** (0.02) | 4.95*** (0.02) | 4.82*** (0.05) | 78.12*** (4.69) | 74.09*** (4.94) | 3.92 (11.00) | -6.39 (13.09) |

| Male | -0.12*** (0.02) | -0.10*** (0.02) | -0.11*** (0.02) | -13.89** (6.32) | -5.63 (7.10) | 6.36 (7.14) | 2.82 (8.07) |

| Retired | 0.07* (0.03) | 0.10** (0.04) | 0.09* (0.04) | 8.15 (7.96) | 25.75** (11.72) | 1.37 (11.19) | 10.36 (11.02) |

| Male and retired (interaction) | -0.08 (0.05) | -0.05 (0.05) | -39.24** (15.57) | -26.49* (14.69) | -28.22** (13.84) | ||

| Post-Year 12 education | -0.06 (0.04) | 2.78 (4.05) | 11.88 (9.53) | ||||

| Less than Year 12 education | -0.03 (0.04) | -4.32 (3.97) | 5.08 (9.39) | ||||

| English | 0.05 (0.03) | 10.02 (10.36) | 3.59 (11.04) | ||||

| Disability | 0.04 (0.02) | -7.00 (6.34) | -4.22 (6.58) | ||||

| Single | -0.04 (0.04) | 80.03*** (19.21) | 68.51*** (17.43) | ||||

| Separated, divorced or widowed | 0.08** (0.02) | 135.44*** (12.28) | 103.45*** (11.20) | ||||

| Lowest three income deciles | -0.07*** (0.02) | 1.36 (4.20) | 1.96 (7.67) | ||||

| Highest three income deciles | 0.07*** (0.02) | -2.52 (4.22) | 4.55 (8.51) | ||||

| Unemployed | -0.21** (0.08) | 46.22 (42.19) | 49.58 (45.77) | ||||

| No children living at home | 0.12*** (0.03) | 44.51*** (6.00) | 50.80*** (6.54) | ||||

Notes: * p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Roger Patulny, R. (2009). The golden years? Social isolation among retired men and women in Australia. Family Matters, 83, 39-47.