The national evaluation of the Communities for Children initiative

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

May 2010

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

This paper considers place-based approaches to support families and facilitate the development of their children, by summarising the findings from the evaluation of Communities for Children (CfC), an initiative under the Australian Government’s Stronger Familles and Communities Strategy (SFCS). The model evaluated has at its heart the coordination of the delivery of services provided by agencies that have contact with children who live in areas at considerably higher risk of disadvantage. The key role in achieving a coordinated approach to service delivery in each of the 45 sites funded under the CfC initiative was assigned to a non-government (not-for-profit) organisation (the “facilitating partner”). For the first time in Australia, the evaluation provided clear evidence of the early impacts of a large-scale, place-based approach to early intervention that is focused on families with young children. In addition to presenting the results of the impact analyses, the authors explore the key elements contributing to the success of CfC.

This article summarises the key findings of the national evaluation of the Communities for Children (CfC) initiative. The evaluation of the CfC was undertaken as part of an evaluation of several area-based interventions known as the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy (SFCS). The study was undertaken by the Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC), University of New South Wales (UNSW), and the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) for the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. More detailed information on the evaluation is provided in the original reports (Edwards et al., 2009; Muir et al., 2009).

Concerns about the impact of the geographic concentration of disadvantage on the wellbeing of children and their future life chances has led to the implementation of place-based or area-based initiatives in a number of countries (e.g., the Sure Start Local Programs in the United Kingdom; see Belsky et al., 2006).

A major Australian area-based intervention is the Communities for Children initiative. CfC is designed to enhance the development of children in 45 disadvantaged community sites around Australia. The initiative aims to improve coordination of services for children 0-5 years old and their families, identify and provide services to address unmet needs, build community capacity to engage in service delivery and improve the community context in which children grow up.

Under the initiative, non-government organisations are being funded as Facilitating Partners to develop and implement a strategic and sustainable whole-of-community approach to early childhood development in consultation with local stakeholders. In implementing their local initiatives, Facilitating Partners establish CfC committees with broad representation from stakeholders in their communities. The Facilitating Partners oversee the development of community strategic plans and annual service delivery plans with the CfC committees and manage the overall funding allocations for the communities. Most of the funding is allocated to local service providers, known as Community Partners, who deliver the activities specified in their community strategic plans and service delivery plans.

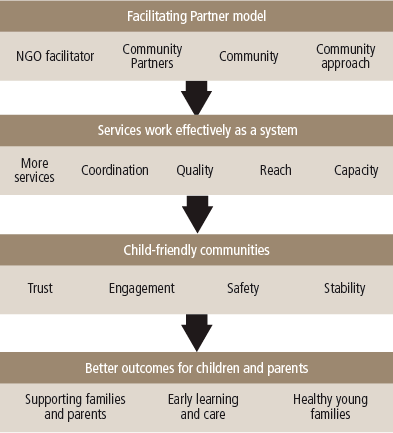

The logic of the CfC model is that service effectiveness is dependent not only on the nature and number of services, but also on coordinated service delivery (see Figure 1). This lead agency approach, where a non-government organisation acts as a broker in engaging the community in the establishment and implementation of CfC, differs from traditional funding models in which governments directly contract service providers. The explicit focus on funded service coordination and cooperation in communities is a unique and important aspect of the initiative.

Figure 1: CfC logic model

The types of services delivered are decided by local committees and based on community needs. Some of the services delivered include home visiting, programs on early learning and literacy, parenting and family support, child nutrition and community events. By improving the coordination of services within geographic areas, the intervention is intended to benefit all children and families in the area, not only those who actually use CfC-funded services.

Initially, funding for the CfC initiative was over $100 million for 45 sites over four financial years (2004-05 to 2007-08). The majority of this investment was spent on service delivery, with Community Partners receiving 60% of the funding, Facilitating Partners receiving 7% of the funding and local evaluation receiving 3%. The remaining 30% was for community resource funding (development, implementation, project management and community development).

It is estimated that $840 was spent on each 0-5 year old child living in the CfC communities between 2004-05 and 2007-08 (based on the number of 0-5 year olds in each CfC site in 2006). This works out to be $210 per child per year.1

In 2009, the focus of the CfC initiative was extended to families with children up to 12 years of age, and funding for the 45 CfC sites was extended until 30 June 2012.

This article provides an overview of the results of the recent evaluation of the CfC initiative. The evaluation outcomes are based on short-run impacts for families and children (12 months after the full implementation of the program) and qualitative and quantitative data collected from service providers over a two-year period. This article describes the impact of CfC on services, children and families. It then discusses elements of the CfC model that contributed to its success and/or presented challenges.

Evaluation methodology

The evaluation of the CfC initiative involved the collection of data from a number of sources using a range of methodologies. This section provides an overview of the key features of the evaluation methodology. A detailed description of the evaluation methodology is provided in the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy: National Evaluation Framework (SPRC & AIFS, 2005) and in the full evaluation reports (Edwards et al., 2009; Muir et al., 2009).

The key challenge in evaluating the impact of area-based initiatives such as the CfC is estimating what the outcomes would have been for children and their families in the absence of the intervention (that is, the counterfactual). There are a number of different approaches that can be used to construct the counterfactual. The approach used to evaluate the impact of CfC is to compare the outcomes, and how they change, for children and their families living in geographic areas in which the CfC has been implemented (CfC sites) with those for children and their families in areas that are similar to the CfC areas but in which CfC has not been implemented (contrast or control sites). Using the Stronger Families in Australia (SFIA) evaluation study (see Box 1), information was collected from the same group of families prior to the implementation of CfC (baseline data) and around 12 months after implementation in both CfC and non-CfC sites.

The logic of the design assumed that the outcomes in CfC and contrast sites would have been the same had CfC not been implemented. Therefore, any differences between the CfC sites and the contrast sites that occurred after the intervention could be attributed to CfC.

The evaluation also collected data on the number of services (all services, not just CfC services) being provided (via a reporting template), and qualitative and quantitative information from service providers on the extent to which services cooperated and were coordinated and whether this had changed following the implementation of CfC.

Interviews were conducted in 2006 and 2007 with 222 CfC stakeholders (97 and 125 respectively) working in the ten selected CfC sites. The stakeholders included Facilitating Partners, service providers, government officers, other relevant agency stakeholders and community members.

In addition to the interviews, a large sample of service providers working for agencies providing CfC services in 41 of the 45 CfC sites completed a survey in 2006 and 2008. There were 442 respondents in 2006 and 302 in 2008. The survey excluded the four remote Indigenous communities because of the cultural inappropriateness of the method. Further details of the survey methodology can be found in Muir et al. (2009).

The work of particular CfC-funded programs was also highlighted using the Promising Practices Profiles process (Soriano, Clark & Wise, 2008). Within the human services sector, practice profiles are used to share information about practices and programs that are of interest to others in the field. Practice profiles assist service providers, community members, and policy-makers to better understand what practices work, how they work, in what contexts, and with whom.

Box 1: The Stronger Families in Australia evaluation study

The SFIA evaluation study involved collecting data from young children and their families in 10 CfC sites and 5 contrast sites. The contrast sites were selected to be comparable to CfC communities in terms of socio-economic status. The study collected data from families with a child aged 2 years in 2006 (Wave 1). Further waves of data were collected in 2007 (Wave 2) and 2008 (Wave 3). The children were around 4 years of age at Wave 3. There were 2,202 families in the study at the first wave and 1,836 in the third wave. There is no evidence of selective attrition; that is, families with particular characteristics did not drop out of the study at higher rates in the CfC sites compared to contrast sites, at least with respect to the outcomes for children and their families at Wave 1.

The first wave of data was collected during the consultation and partnership-building phase of the CfC initiative, and this provided a baseline of data with which impacts of the CfC initiative were identified. Wave 3 was conducted approximately one year after CfC activities were underway.

The impact of CfC was estimated using statistical techniques that allowed child, family and community outcomes in the CfC sites to be compared to what they would have been in the absence of the CfC intervention (using outcomes in the contrast sites). Detailed information on the statistical methods used is provided in Edwards et. al. (2009).

Impact of the CfC initiative on local services

The CfC initiative has had a significant impact on the number, types and capacity of services available in the communities in which it has been based. Service coordination and collaboration also has improved between services within CfC communities.

A significant number of activities have been delivered as part of the CfC initiative. By December 2007, CfC had delivered 641 funded activities throughout Australia - an average of 14.2 activities per site. It is estimated that the total number of services (CfC and other services) in the CfC sites increased by 12% between 2006 and 2008.

The CfC-funded activities delivered within communities have been very diverse and reflect the four priority areas of the 2006 National Agenda for Early Childhood. These include projects to facilitate and promote healthy young families, early learning and care, support for families and parents and the creation of child-friendly communities. While many projects could be categorised across more than one area, reports from Facilitating Partners suggest that projects most commonly focus on creating child-friendly communities.

Service capacity has also improved in some CfC communities by addressing some service gaps. This includes, for example, establishing preventative services, and trialling innovative programs. The increases in service provision and capacity have been accompanied by an improvement in the recruitment and engagement of families who have previously been disengaged from early childhood services. Engagement has also increased among families from groups considered hard-to-reach, such as socio-economically disadvantaged families and children, those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (CALD) and/or Indigenous Australians.

CfC programs and recruitment methods have been specifically developed, modified and/or expanded to increase the engagement of families from hard-to-reach target groups. For example, using "soft entry" approaches, which take traditionally formal services into familiar, non-threatening locations where families congregate, has been one successful strategy. Practical support, like transportation and active referrals, along with networking and coordination between service providers, has also increased service reach. Employing staff and outreach workers with local connections, where at least one worker was of similar background to the target group, has also been effective. Finally, service research has been facilitated because non-government organisations are perceived as being less threatening to families than government departments (based on the fear that governments may try to remove children).

Table 1 provides examples of a the types of CfC activities that have been implemented.

| Program | Description |

|---|---|

| New South Wales | |

| Early Childhood Coordinators | Two Early Childhood Coordinator positions (one Indigenous) were created to engage, connect and support (mainly Indigenous) children, families and other service providers in the Dubbo, Naromine and Wellington area. They conduct various community activities aimed at addressing the lack of knowledge among families about services and the lack of appropriate services, as well as increasing awareness of and collaboration with other service providers working in the area. |

| Engaging Fathers Project | The project uses a holistic team approach to delivering services by improving the workers' and key stakeholders' capacity to engage fathers (and grandfathers and male carers) in children's services and increase awareness about different approaches to parenting and fatherhood. The project works with other CfC partners as an "expert" consultant, assisting and supporting the partners to engage fathers and maximising outcomes for fathers across the entire CfC initiative. |

| Fairfield Refugee Nutrition Project | The project focuses on food insecurity among refugee families who have settled recently in the Fairfield local government area (LGA). The project aimed to increase the knowledge and capacity of refugee families around healthy eating and at the same time enhance the capacity of community, health workers and settlement services to identify and address nutrition and food security issues among refugee families in the area. |

| Our Family is Starting School: Tracks to the Big School (TTBS) | TTBS works with children, their families, preschools, playgroups and local schools before children begin kindergarten. An Assistant Princwpal was appointed to engage families living in Fairfield LGA (a large multicultural community) to engage parents who have not accessed school services previously due to cultural, economic or other reasons. |

| Northern Territory | |

| Families and Schools Together (FAST) | FAST is an 8-week early intervention/prevention program designed to strengthen family functioning and targets the whole family. Multifamily meetings are usually held in the school and families are provided with positive interactional experiences facilitated by a collaborative leadership team comprising a parent partner, a school partner, a community-based agency partner and a community-based partner. |

| Queensland | |

| Parent Education and Relationship Living Skills (PEARLS) | PEARLS comprises parent education, parent-child relationship development and parental support activities to parents living in the Northern Gold Coast area, which is one of the fastest population growth areas in Australia, comprising six widely dispersed and largely unconnected and isolated areas. |

| South Australia | |

| Around About | Around About is a specialised program based at Seaton Central in the western suburbs of Adelaide. Families accessing the program have high needs relating to all aspects of social disadvantage and children have little or no access to preschool or kindergarten. Around About addresses concerns about the high number of children entering school with speech delays and challenging behaviours as a result of little or no exposure to preschool services. |

| FamilyZone Ingle Farm Hub | FamilyZone Ingle Farm Hub provides a parent-friendly environment to facilitate improved parent-child interaction as well as access to peer and staff support. The hub attracts users from many cultures (a significant contingent of African and Afghan families) and offers activities such as supported playgroups for general or culture-specific groups, home visiting, craft and cooking groups, parenting courses, mothers and babies groups, parent support groups, music and movement groups, post-natal groups and English classes. The FamilyZone is co-located with other services to allow for a seamless transition between services and located at the Ingle Farm Primary School. |

| Intensive Supported Playgroup Program: Little Engines | Little Engines provides free intensive support playgroup sessions for children aged 0-5 years and their families. Through the program, the families become aware of services in the community and supportive relationships are fostered between families and local services. The program also involves skills transfer via collaborative partnerships with agencies whose work involves supporting families in the region. |

| Onkaparinga Community Connections Project (OCCP) | Onkaparinga Community Connections Project is a partnership between a community centre and two primary schools. The project builds community capacity and develops the personal skills in the communities of Noarlunga Downs, Hackham West and Huntfield Heights, which are areas of significant disadvantage. Community capacity-building activities include: social events and parent activities; provision of crisis support and brief counselling; involving parents in decision-making about activities; peer support programs for parents; training opportunities for mentors and participants; and other activities that promote economic self-reliance. |

| Parent Advisory Group Extraordinaire (PAGE) | PAGE is an inclusive, volunteer group of parents of young children who are working together to create a more family-friendly city. Port Augusta has a large transient population, is culturally diverse, with a high number of Indigenous communities (27 clans). Through PAGE, an innovative model was developed for active community involvement and a more child- and family-friendly community. |

| Playgroups on the Move (PGOTM) | PGOTM provides support to 37 existing playgroups by providing sustainable resources, training and mentoring support to playgroup leaders, improving linkages (personal, community and service-based) and establishing innovative collaborative partnerships between playgroups and wider community services. |

| Tasmania | |

| Bridges for African Men and Families | Bridges for African Men and Families builds understanding among community-based services of issues faced by newly arrived African communities in Tasmania in order to develop culturally appropriate programs, as well as to promote service coordination and collaboration. A monthly dialogue meeting is conducted with service providers and community members, which is the springboard for responsive services to emerging African communities. |

Source: Soriano, Clark & Wise (2008, Table 5)

Not only have services increased in number, type and capacity, but increases in service coordination have also occurred in CfC communities. According to the CfC reporting data, between July 2006 and December 2007, 89% of CfC-funded activities were conducted in partnerships consisting of two or more organisations or groups.

The service coordination survey also found highly significant increases in collaboration between staff from different agencies in CfC communities. In 2006, 34% of agencies worked closely together most of the time; by 2008 this had increased to 66%.

Services have worked together by referring clients, exchanging information and holding interagency meetings. Between 2006 and 2008, there were significant increases in the proportion of agencies referring clients and conducting interagency staff training (from 86% to 92% and 57% to 73% respectively).

The number and strength of networks increased, as did trust and respect between service providers, which helped to break down some previous silos. This coordination and collaboration helped service providers to solve problems, increase their skills and capacity, identify the best providers for different services and minimise duplication.

Impact of CfC on children and their families

As outlined in the previous section, the impact of CfC on families and children was estimated using data from the Stronger Families in Australia study. The outcome measures related to four areas:

- healthy young families - child injuries requiring medical attention, child and parent physical health, children's experiences of emotional and behavioural problems, children's prosocial behaviour, children being overweight, and parents' mental health;

- supporting families and parents - harsh parenting, parenting self-efficacy or self-confidence, parent relationship conflict, and living in a jobless household;

- early learning and care - children's receptive vocabulary achievement and verbal ability, and the quality of the home learning environment; and

- child-friendly communities - parents' involvement in community service activities, the level of support parents receive from others to raise children, the quality of the neighbourhood as a place to raise children, parents' sense of community social cohesion, their perception of the quality of facilities in the community, and the level of unmet service needs.

Overall, there was evidence that CfC has had positive impacts. The positive impacts were that:

- fewer children were living in a jobless household;

- parents reported less hostile or harsh parenting practices; and

- parents felt more effective in their roles as parents.

The CfC initiative was associated with parents reporting lower levels of child physical functioning. However, it is unclear whether this reflects an actual deterioration in child and parent health in CfC sites compared to children and parents in non-CfC sites. It is possible, for example, that exposure to CfC programs and activities brought parents and their children to the attention of professionals and others who may have recognised undiagnosed health conditions, or that CfC programs and services in some other way increased parents' understanding of their own and their children's actual health needs. Other studies do suggest that parents from lower socio-economic backgrounds have more difficulties recognising health problems (Berra et al., 2009) and are more likely to believe that child health problems will improve on their own (Pescosolido et al., 2008).

For many of the outcome measures, the estimated impact of CfC was not statistically significant, which is not surprising given that any effects were likely to be small in the short run. Depending on the statistical model estimated, between two-thirds and three-quarters of the outcome variables indicated a positive, although not necessarily statistically significant, effect. Although non-significance means that it is not possible to say with a high level of confidence that the individual effect was not different from zero, the skewed pattern of results towards positive effects provides support for the conclusion that CfC has had some positive impacts in the short run.

The SFIA evaluation study also estimated whether the CfC intervention had different impacts for three groups that are at particular risk for poor child outcomes and who have been shown in some studies to be less likely to benefit from area-based interventions. The groups are:

- hard-to-reach households with at least one of the following characteristics: no father present, mother not employed and father not working/not present, low household income, maternal education Year 10 or less, a parent born overseas, and child is of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin;

- households with low incomes ($485 a week or less); and

- households with mothers with low education levels (Year 10 or less).

These groups were defined according to their characteristics pre-intervention (that is, at the time of the Wave 1 interview). The evaluation provided evidence that the CfC intervention had a positive effect for at least some of the measures of wellbeing among low-income, low maternal education and generally hard-to-reach households.

Positive and statistically significant findings in relation to these hard-to-reach groups included:

- higher levels of receptive vocabulary and verbal ability among children of mothers with Year 10 education or less;

- less hostile/harsh parenting among hard-to-reach parents;

- higher involvement in community service activities among parents in households with lower income;

- higher involvement in community service activities in households comprising mothers with Year 10 education or less;

- fewer children in jobless households across all three subgroups; and

- increased parental perception of community social cohesion reported in lower income households at the p < .07 level of statistical significance.

Consistent with the estimates for the population as whole, there were also some negative findings from the CfC intervention on health outcomes for the hard-to-reach, low-education and low-income groups. They were:

- decreased reported mental health of mothers with Year 10 education or less;

- decreased reported general health of mothers in relatively lower income households; and

- decreased reported child physical functioning among children in all three subgroups.

Similar to the overall pattern for the population as a whole, the overall pattern of significant and non-significant estimates was consistent with the interpretation that there was some evidence of CfC having a positive impact. Specifically:

- 69-78% of the outcomes at Wave 3 for low-income households reflected a positive impact of the CfC initiative;

- 50-64% of the outcomes at Wave 3 for households where the mother had low levels of education suggested positive impacts of the CfC initiative; and

- 60-65% of outcomes at Wave 3 for hard-to-reach households suggested positive impacts of the CfC initiative.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that the CfC initiative had some success in improving outcomes among the most vulnerable children and families in relation to children's early receptive vocabulary and verbal ability, parental joblessness rates and mothers' involvement in community activities.

Which elements of the CfC model contributed to its success and what were the challenges?

The evaluation identified several features of the CfC model that were particularly important in contributing to the positive impacts on service provision and children and their families, at least in the short term. These factors - the Facilitating Partner model, funding and the community focus - are discussed in this section.

The Facilitating Partners model

The Facilitating Partners have been essential to the development and implementation of CfC. The role played by Facilitating Partners in asset mapping, community development, program establishment, facilitation, coordination, implementation and support has been a major strength of the CfC initiative. The Facilitating Partner model has given community organisations a sense of ownership, and small agencies have had an opportunity to attain funding, develop networks and build capacity. For example, training in relation to funding applications and program implementation and reporting has been undertaken.

Facilitating Partners have been most effective when the non-government organisations they represent have been well-known in the community, when they have had administrative support and when they could build on pre-existing interagency collaborations. Another key element of the successful operation of a Facilitating Partner has been when it has provided clear and regular information to other stakeholders, established transparent and equitable decision-making processes and set up structures in addition to the CfC committee. The success of the CfC model has also been highly dependent on the qualifications, skills, experience and personalities of the project manager, staff and volunteers. Facilitating Partner project managers, for example, have needed good communication, organisational, facilitation, contract management and conflict resolution skills.

Facilitating Partners have been challenged when the above circumstances have not been in place. Furthermore, the high-level demands on project managers have resulted in recruitment difficulties (especially in rural and remote areas) and some CfC sites have struggled with high staff turnover. In some sites, other local non-government organisations have resented the leadership role of the Facilitating Partner organisation.

Funding

Funding has been critical to all aspects of the CfC initiative, including for the work of the Facilitating Partner, the coordination of services, and the provision of community-based projects, programs and activities. It has been essential to the establishment and implementation of the initiative, and for assessing its assets, strengthening existing service networks, filling service gaps, helping address unmet community needs, developing innovative programs and increasing service access.

Funding has also been critical to improvements in service coordination. The 10 SFIA CfC sites spent $1.5 million or 9% of their service activity funding on activities related to coordination. In the interviews, CfC service providers reported that they preferred the CfC funding model to direct funding because it was community-based, allowed for flexibility and built on local connections.

Despite the positive aspects of the funding model, there have been some challenges. These include having to provide budgets for the entire program early in the establishment of CfC. There has also been a perception that funding could not be adjusted over the three-year period, and the accountability requirements have put substantial burdens on Facilitating Partners, especially since they have also had to assist many CfC service providers with their reporting. In addition, competitive tendering has caused tensions in some CfC sites and funding for Facilitating Partners has not always been sufficient to fund the workload adequately.

Community focus

Having a community focus has enabled service delivery to be flexible to meet the needs of the community in the context of the capacity of the services. The asset-mapping component of CfC has helped communities to tailor CfC programs, activities and services. Community consultations have helped CfC stakeholders understand the needs or aspirations of community members, fund and design programs and services to support these needs, increase awareness of programs, and help engage families. This has been critical in communities with a high proportion of Indigenous Australians. Involving other local agencies in the CfC initiative has enabled existing community organisations to deliver services based on their expertise and skill sets, and to build capacity.

Community consultation is a time-consuming process and funding provided by CfC has enabled wider consultations. This has also been assisted when a community development officer has been employed.

It has been difficult to build a comprehensive picture of local needs, existing services and service gaps in the areas of the CfC sites. In some instances, needs were later discovered that had not been apparent during the early phase of the initiative. Some of the smaller non-government organisations have struggled with contractual requirements and with recruiting appropriate staff. Moreover, it has been difficult to achieve widespread, effective community consultation with Indigenous Australians in the three- to four-year funding period.

CfC committees, which are comprised of community members, have also played an important role in planning and implementing the local CfC initiative. In some cases, they have also worked as a local management committee. This has been the case when committee membership has been diverse, meetings have been held regularly, decisions have been made collaboratively and there has been a proactive Facilitating Partner leading the group. However, CfC committees have also generally been unsuccessful in recruiting smaller service providers, business representatives, and parents of young children. There has also been some disengagement of community members as CfC has progressed and there has been a shift in focus from initial community consultation to project management of CfC services. The committees that have prevented stalled momentum and attrition have refocused their remit after the distribution of funding.

Challenges

Those providing CfC programs have faced several challenges. These have been particularly around the time frame and geographic locations of the CfC sites.

CfC has struggled with the three- to four-year time frame. The time frame has been inadequate for very disadvantaged communities and for those with limited pre-existing infrastructure or networks. Implementing an innovative model such as CfC without a longer term commitment has also risked raising false expectations and damaging the trust of community members. This has particularly been the case in very disadvantaged sites.

Geographic issues have also hampered some CfC sites. For example, arbitrary administrative boundaries have impeded service delivery, and service coordination in some sites has included several distinct suburbs, regions and/or government areas. It has also been very difficult to establish and implement the CfC initiative in remote areas because of limited infrastructure, high costs, relatively short time frames, difficulty in the recruitment and retention of staff, and extreme seasonal weather.

Conclusion

The national evaluation of the CfC initiative found that the early stage of the implementation of the CfC service model has been modestly successful, particularly when seen in light of findings from the Sure Start initiative (the comparable intervention in the UK), and given that children who participated in the SFIA study only received services from approximately 3 years of age. As the CfC programs continue to operate and improve in terms of access, outreach and effectiveness, one might expect even larger differences between children and families exposed to the initiative and those who are not (as was demonstrated by Sure Start and other similar programs).

The CfC initiative involved essentially three new innovations to services for children in their early years and their families:

- a greater number of services based on the needs of the community;

- better coordination of services; and

- a focus on improving community "child-friendliness" (that is, community "embeddedness", or social capital).

A legitimate question to be asked would be whether the extra expenditure on service coordination and community development has been justified or, to put it another way, whether it would have been more effective to spend the resources on more direct services. The fact that the effect sizes of CfC were comparable to, if not greater than, many programs that provide direct services, and that these effects were evident for children in the CfC communities irrespective of whether they had actually received services, seems to point towards an additional effect over and above the provision of new services. Indeed, positive change in relation to parental involvement in community activities, joblessness and social cohesion supports the idea that "community embededness" may have an additional effect on children and families, and that provision of increased services on their own would not have achieved this aim.

While this early evaluation produced positive results, the whole-of-community early childhood intervention model is highly unstructured and unstandardised; thus, the integrity and quality of the design and implementation of the CfC model has most likely affected the outcomes achieved. Which key design and program elements are most efficacious is a critical question that deserves further empirical inquiry (see discussion in the national evaluation report, Muir et al., 2009).

The evaluation suggests that the CfC model can make an important contribution to the family and community contexts in which disadvantaged children grow up, and in terms of their wellbeing. Whether the CfC is a strategy that can sustain benefits in the long term, and whether longer exposure to the CfC initiative at a later stage in operation can produce greater benefits is, as yet, unclear.

The effect sizes of the CfC impacts on all outcomes were small, but can be considered positive relative to what was observed in the early phase of Sure Start. The current results were also comparable in size to those found in the later impacts evaluation of Sure Start, where 3-year-old children were exposed to more developed programs from birth (Melhuish, Belsky, Leyland, Barnes, & National Evaluation of Sure Start Research Team, 2008).

An important question, however, is the extent to which these effects compare with alternative early childhood interventions that target specific client groups and seek to enhance child outcomes through other processes, such as centre-based programs, home visiting programs, case management interventions and parenting programs. Reviews of the effectiveness of early childhood interventions found that most studies reported effect sizes on parenting and child outcomes that were small to moderate (Karoly, Kilburn & Cannon, 2005; Wise, da Silva, Webster, & Sanson, 2005). It should also be noted that most of these evaluations measured outcomes for children who were directly enrolled in the program, whereas CfC is aimed at improving outcomes for children in the whole community.

The fact that the effect sizes of CfC were comparable to many alternative early childhood interventions, and that these effects were evident irrespective of whether parents and children in the CfC communities had actually received services, seems to point towards an additional effect over and above the provision of new, standalone services, possibly as the result of a better coordinated local system of early childhood services and/or other enhancements to the community context in which children develop.

Endnotes

1 These estimates are based only on the CfC sites that were part of the Stronger Families in Australia evaluation study (see Box 1).

References

- Belsky, J., Melhuish, E., Barnes, J., Leyland, A. H., Romaniuk, H., & National Evaluation of Sure Start Research Team. (2006). Effects of Sure Start local programmes on children and families: Early findings from a quasi-experimental, cross sectional study. British Medical Journal, 332, 1,476-1,482.

- Berra, S., Tebe, C., Erhart, M., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Auquier, P., Detmar, S. et al. (2009). The European KIDSCREEN group: Correlates of use of health care services by children and adolescents from 11 European countries. Medical Care, 47, 161-167.

- Edwards, B., Wise, S., Gray, M., Hayes, A., Katz, I., Misson, S. et al. (2009). Stronger Families in Australia study: The impact of Communities for Children (Occasional Paper No. 25). Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Karoly, L. A., Kilburn, M. R., & Cannon, J. S. (2005). Early childhood interventions: Proven results, future promise. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Melhuish, E., Belsky, J., Leyland, A. H., Barnes, J., & National Evaluation of Sure Start Research Team. (2008). Effects of fully established Sure Start Local Programmes on 3-year old children and their families in England: A quasi-experimental observational study. The Lancet, 372, 1,641-1,647.

- Muir, K., Katz, I., Purcal, C., Patulny, R., Flaxman, S., Abello, D. et al. (2009). National evaluation (2004-2008) of the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy 2004-2009 (Occasional Paper No. 24). Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Pescosolido, B. A., Jensen, P. S., Martin, J. K., Perry, B. L., Olafsdottir, S., & Fettes, D. (2008). Public knowledge and assessment of child mental health problems: Findings from the National Stigma Study-Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 339-349.

- Social Policy Research Centre, & Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2005). Stronger Families and Communities Strategy: National evaluation framework. Sydney: SPRC & AIFS. Retrieved 28 January 2010, from <www.aifs.gov.au/cafca/evaluation/pubs/framework.html>.

- Soriano, G., Clark, H., & Wise, S. (2008). Promising Practice Profiles: Final report. A report prepared for the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs as part of the National Evaluation Consortium (Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW and the Australian Institute of Family Studies). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Wise, S., da Silva, L., Webster, B., Sanson, A. (2005). Efficacy of early childhood interventions (Research Report No. 14). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Muir, K., Katz, I., Edwards, B., Gray, M., Wise, S., Hayes AM, Professor A. & the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy evaluation team. (2010). The national evaluation of the Communities for Children initiative. Family Matters, 84, 35-42.