Do Australian teenagers contribute to household work?

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

September 2010

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Do Australian teenagers contribute to housework and child care? How do their contributions relate to the time use of their mothers and fathers and the tasks that need to get done? How do young people's notions of duty and entitlement affect social divisions of labour, the viability of particular demographic strategies, and theorisations of what counts as "work" more generally? Large and sophisticated time use surveys, such as those conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in 1992, 1997 and 2006, provide an invaluable source of quantitative information regarding these issues. In this paper, we present some of the findings they provide about three samples of 15-19 year olds living in single-family households. These Australian time use surveys have provided material for many excellent studies of the distribution of domestic and caring labour between adults. Research on the distribution of work between parents and teenagers is more difficult to find. As far as we know, this paper represents the first systematic attempt to explore the relevance of Australian time use surveys to studying teenagers as domestic workers and carers over time.

Do children work?

This study is set in a larger context of emphasising young people as actors in their own right, and renewing the focus on children and work in industrialised countries. It is now routinely acknowledged that over the last three decades, youth labour markets have been radically reshaped. The most marked trend has been the disappearance of full-time positions for school leavers, and a steady growth of part-time and casual jobs, often filled by those who still attend school. As a corollary of these developments, a larger proportion of young people participate in educational activities for longer periods of time, and transitions from education to paid employment have become more complex and diverse. Among the studies dealing with changing patterns of growing up, those documenting the extent of children's participation in paid work have proved particularly important. However, as we discuss later in this paper, much less attention has been given to those aspects of socially useful labour that are not paid (such as housework and care work), but which many commentators argue should also be included in definitions of what counts as "work".

Recently, young people's usefulness has become the focus of significant research activity. In 2001, a Victorian report (Industrial Relations Victoria, 2001) found that the formal workforce participation rate of 15-year-olds attending school increased from around 10% in 1966 to 39% in 2001. Among students who were also part-time workers, one in five was employed for more than 16 hours a week. The following year, the Textile, Clothing & Footwear Union of Australia (TCFUA) Victoria estimated that there were 36,000 children involved in outwork in Victoria (TCFUA Victoria, 2002). Some children assisted directly with sewing and finishing; others took over tasks that would otherwise be done by adults. By 2005, noting that "little is known about the work experience of children aged 15 years or younger" (Fattore, 2005, p. 1), the New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People commissioned a survey of young people and work and published a comprehensive report on Children at Work (Fattore, 2005). As in the report on outwork, the Commission adopted a wide definition of "work",1 showing that over 56% of the 11,000 children between 12 and 16 years who took part in the study had worked at a broad range of paid and unpaid tasks other than schoolwork and routine housework in the previous 12 months. Such work participation increased with age, and was more prevalent among females than males. Children living in the least disadvantaged areas were twice as likely to work as those in the most disadvantaged ones; teenagers in rural and regional areas were twice as likely to participate in such work as those in metropolitan areas. Finally, children from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds were half as likely to take part in tasks other than schoolwork and routine housework compared to those of Anglo-Australian background.

Focusing on children in low-income families, other scholars (e.g., Dodson & Dickert, 2004; Ridge, 2007) have documented the extensive physical work, care-giving and domestic management responsibilities critical to family survival that children - and girls in particular - provide for their households. In recent years, another eminently useful group of teenagers - those caring for ill or disabled family members - came into public and policy focus. Spread through the socio-economic spectrum, these young carers are estimated to constitute between 6% and 10% of the Australian youth population (Noble-Carr, 2002).

In contrast to the extensive research documenting young people's "usefulness", a number of qualitative studies of teenagers' resistance to housework - as well as a voluminous advice literature dealing with conflicts between parents and children - focus on their notions of entitlement to the work of others and their apparent "uselessness".2 Goodnow and Lawrence (2001), for example, noted that most Australian parents justify requests for housework in terms of preparation for the future, rather than in terms of equitable division of work that must be done now. Their sceptical offspring, in contrast, according to an international overview study, "do not consider their involvement in household chores as an opportunity to learn valuable skills ... feel little responsibility for home chores, and experience parental requests ... as harassment" (Lee, Schneider, & Waite, 2003, p. 110). In Australia, teenagers were found to drive a hard bargain for washing the dishes or making a bed, and to refuse to do any more housework if they felt they were not getting an appropriate rate for the job (Gill, 1998). A study completed in 2007 found that Melbourne teenagers strenuously resisted mothers' and fathers' attempts to get them to do domestic tasks (Carter, 2007). In most of the families surveyed, children as well as men claimed an entitlement to be someone who has domestic work done for them, rather than someone who must do such work for others. Among those who could afford it, women too claimed this status; the most affluent families tended to understand domestic labour in terms of a hierarchy based on relations of class rather than those of gender, and employed others to take care of it (Carter, 2007).

Time use surveys and family relations

One approach to the widely divergent portrayals of young people noted above would be to argue that, on balance, one side is more accurate and appropriate than the other. This paper proposes an alternative strategy. Statistically representative surveys, we suggest, can be used to map a diversity of young lives. Rather than ask whether teenagers work (given conflicting definitions of what "work" entails), it is more informative to map all the activities respondents undertake during a typical day. Rather than deal with individuals in isolation (given the capacity for children and adults to substitute for each other in the performance of many necessary and time-consuming tasks), it is better to deal with whole households, and examine the distribution of tasks among co-resident family members (Williams, Bridge, & Pocock, 2009). In this context, it is significant that time use surveys, which provide particularly useful material for such projects, tend to be used in markedly different ways by researchers focusing on adults and on children.

Influenced by feminist debates, studies of time use among adults have contributed to a fine-grained understanding of the gender division of labour, with its complex inequalities, compromises and relations of power (Folbre & Bittman, 2004). A recent overview of the 2006 ABS time use survey, for example, concluded that even though men's average contribution to unpaid work has grown by about an hour and a half a week over the last decade, women in Australia still undertake twice the amount of housework of their male counterparts (ABS, 2009). As in other countries, women's increased participation in the paid workforce has had more effect on decreasing the time they themselves spend on housework rather than increasing the contribution of men (Craig, 2006). Since Australian men contribute about twice as many hours to paid work than do women, the total weekly workload of women and men, measured in terms of their main activity, is almost the same, at just over 50 hours (ABS, 2009). However, when concurrent secondary activities are taken into account, in households in which there is a youngest child below school age, mothers have a workday that is between three and five hours longer than fathers in the same family configuration (Craig & Bittman, 2008).

In contrast to emphases on equitable relations between women and men, researchers dealing with children and teenagers tend to focus on factors such as individual health status and the development of intellectual skills, or else on the distribution of time between activities such as television viewing, computer use, school-related activities and part-time work, and their possible relation to valued personal attributes such as educational achievement and successful transition to work (Larson & Verma, 1999). Where a relational approach to age relations is adopted, it most often deals with the effect of children on adults' time use and living standards, while regarding children as undifferentiated care-consuming units (Craig, 2007; Craig & Bittman, 2008). Frequently, the data leave researchers no choice in the matter. The ABS time use surveys count the number of household members under 15 years of age but do not record what these children do with their time. They thus allow researchers to estimate the differential demands for housework in households with different numbers of children, but do not make it possible to assess the way in which children's self-care and housework substitutes for parents' care work and vice versa.

In addition to inspiring different analytical emphases, sensitivities regarding "child labour" affect the collection of data, and in turn limit the questions that can be answered. Eurostat (2004) recommended that "persons of 10 years and older are included in the Time Use surveys" (p. 8). Finland, Norway, Sweden, Austria and Japan have followed these recommendations; Belgium, Germany, Hungary, New Zealand and Netherlands survey those aged 11 or 12 years and over. While several Australian panel surveys have begun to track the time use of babies, parents and carers,3 the national time use survey conducted by the ABS in 2006 only dealt with those aged 15 years and over.

Whatever the precise reasons, in comparison to the wealth of statistically based studies dealing with gender divisions of labour among adults, research on the distribution of work between parents and teenagers is more difficult to find. The existing literature has shown that, on average, young people in developed countries do little around the house, and create more mess and bother than they clean (e.g., Alsaker & Flammer, 1999; Gauthier & Furstenberg, 2000; Hofferth & Sandberg, 2001; Larson & Verma, 1999). One typical European study, for example, estimated that in families with the youngest child aged between 7 and 15 years, teenagers contributed less than a third of the total work they created, and in families with the youngest child aged over 15, teenagers' supply of housework still equalled only 38% of their total demand for it (Bonke, 1999). Throughout, boys were shown to constitute a greater drain on their parents' time and resources than girls. In a thought-provoking analysis about a three-way division of domestic labour between mothers, fathers and children in the US, Goldscheider and White (1991) concluded that in white, two-parent families, teenage boys hardly lifted a finger, but teenage girls performed a substantial proportion of the domestic work. Their innovation was to point out that mothers' increased education and participation in the paid workforce, particularly when combined with the higher education of their partners, tended to make marriages somewhat more egalitarian. As far as mothers were concerned, however, little had changed with respect to the total housework they performed, because children decreased their share of the work proportionately to the increase in housework performed by their fathers.

Australian time use surveys and teenagers' housework

Our project uses existing Australian time use surveys, despite their emphasis on adults, to illuminate some of the issues regarding the age relationships mentioned above. Even though the national time use surveys for 1992, 1997 and 2006 only recorded the activities of those 15 years and over, they do provide invaluable insight into the changing distribution of tasks between the generations. To anticipate, as in other industrialised countries, Australian teenagers are making a small - and decreasing - contribution to housework. When Bittman (1991) summarised the results of the 1987 Australian Pilot Survey of Time Use (which only dealt with those 15 years and older in the Sydney Statistical Division), he noted that the most notable feature of children's contribution was:

just how small it is. The average [mean] time spent in unpaid work around the house by these progeny is a meagre 7 hours 6 minutes per week [or just over one hour a day]. Beside this Lilliputian contribution even husbands' contributions begin to look giant. (pp. 23-25)

In the 2006 ABS survey, teenagers' mean contribution to housework and child care combined had shrunk to 43 minutes per day; their contribution to domestic chores alone had diminished to 37 minutes per day.

There were 7,056 respondents in the 1992 survey, 7,260 in 1997, and 6,902 in 2006.4 Our analysis was restricted to teenagers who were 15-19 years old and lived in single-family households with their parents. Teenagers were excluded where no parental time use data were available. In all, there were 522 teenagers meeting the above criteria in the 1992 sample, 511 in 1996 and 486 in 2006. Around 70% of the young people were from families where only one teenager reported, almost 30% from families where two teenagers reported, and around 2% from households where three did so. In each survey, respondents were asked to record all their primary and secondary activities in five-minute intervals over two days. Our analysis only deals with the primary activities recorded by respondents. In Table 1, we present a summary of the results, arranged in the nine major ABS Time Use Activity categories. Other than in Table 1, we combine categories 4 and 5 into one general category of "domestic and child care" activities. The figures are derived from the total time reported for each activity per person divided by the number of diary days (almost always two) supplied by that person.5 Where we relate the time use of parents and teenagers, we refer to co-resident family members rather than the full sample of adult respondents. This makes for a parent sample of 772 in 1992, 717 in 1996 and 678 in 2006. It is important to note that the number of parents cannot simply be divided by two to obtain the number of households: some teenagers were from single-parent families; other parents were in the sample more than once because they were linked to more than one reporting teenager.

| Means | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | Father | Daughter | Son | |||||||||

| 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | |

| No activity | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 15 |

| Personal | 607 | 640 | 653 | 600 | 622 | 628 | 645 | 699 | 716 | 647 | 695 | 683 |

| Employment | 182 | 188 | 196 | 373 | 380 | 332 | 81 | 93 | 86 | 117 | 104 | 103 |

| Education | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 217 | 193 | 175 | 189 | 155 | 197 |

| Domestic | 236 | 226 | 218 | 108 | 96 | 125 | 59 | 52 | 43 | 41 | 33 | 31 |

| Child care | 29 | 29 | 33 | 9 | 11 | 15 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Purchasing | 59 | 62 | 66 | 32 | 36 | 37 | 41 | 38 | 48 | 27 | 24 | 23 |

| Volunteering and adult care | 20 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 |

| Social and community interaction | 102 | 49 | 50 | 81 | 42 | 47 | 153 | 65 | 60 | 140 | 54 | 63 |

| Recreation and leisure | 199 | 218 | 195 | 222 | 235 | 231 | 224 | 284 | 282 | 268 | 362 | 321 |

| Productive activities* | 529 | 526 | 538 | 534 | 538 | 525 | 415 | 386 | 366 | 383 | 321 | 358 |

| Median | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Father | Daughter | Son | |||||||||

| 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | 1992 | 1997 | 2006 | |

| No activity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Personal | 600 | 629 | 648 | 595 | 620 | 620 | 648 | 690 | 710 | 640 | 696 | 675 |

| Employment | 53 | 43 | 123 | 385 | 403 | 330 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Education | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 130 | 105 | 63 | 28 | 19 | 95 |

| Domestic | 228 | 208 | 203 | 73 | 65 | 95 | 40 | 35 | 28 | 20 | 15 | 10 |

| Child care | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purchasing | 45 | 48 | 53 | 13 | 18 | 15 | 23 | 15 | 25 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Volunteering and adult care | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Social and community interaction | 75 | 28 | 28 | 35 | 15 | 13 | 103 | 33 | 30 | 90 | 20 | 15 |

| Recreation and leisure | 180 | 201 | 170 | 190 | 203 | 210 | 200 | 263 | 273 | 248 | 341 | 305 |

| Productive activities* | 529 | 515 | 545 | 561 | 553 | 555 | 434 | 390 | 373 | 420 | 313 | 365 |

Notes: Data is restricted to single-family households containing parents and co-resident teenage children aged between 15 and 19 years. Time spent is given in terms of main activities, not concurrent secondary activities. * Productive activities comprise the categories: employment, education, domestic, child care, voluntary and adult care, and purchasing.

Source: ABS 1992, 1997a, 2006a

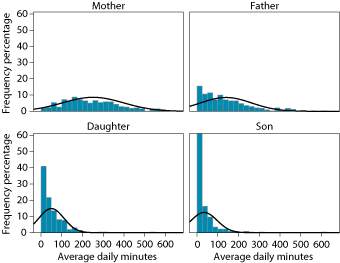

There is a range of technical problems with reporting the results of our analysis of this data. The most significant one is the fact that family members' housework and child care activities are not normally distributed. As shown in Figure 1, while the activities of mothers resemble a hat-shaped normal curve, those of fathers, daughters and sons look like an increasingly precipitous slide, with ever-greater proportions registering no domestic and child care activities at all. As a result, the mean daily minutes of family members' contributions present a more favourable and equitable picture of family life than medians do.6 For this reason, we report both in Table 1.

Figure 1: Frequency distributions of daily minutes spent in domestic and child care activities, by family member, 2006

Note: Data is restricted to single-family households containing parents and co-resident teenage children aged between 15 and 19 years. Time spent is given in terms of main activities, not concurrent secondary activities.

Source: ABS 2006

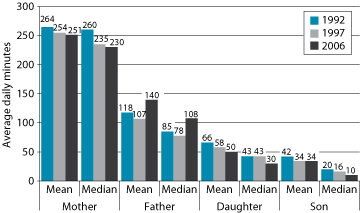

At first glance, the data suggest that young people are increasingly "domestically useless". Figure 2 depicts the shrinking teenage contributions to housework and child care, particularly when compared to those of their parents. Figure 1 and Table 3 both show the growing proportion of young people who reported doing no domestic or child care tasks whatever on either of the two days on which their time diaries were completed. In the 2006 sample, 118 of the 486 teenagers were in this category; 65 others did between one and less than ten minutes daily on average. As can be seen in Table 1, the median daily minutes for teenage sons were overwhelmingly taken up by personal activities and recreation and leisure. In the 2006 sample, half or more of this group reported no employment, purchasing and voluntary and adult care activities; their medians for social and community interaction and for domestic work, were fifteen and ten minutes respectively. The median time use of teenage daughters was more varied. They spent some time shopping, twice as much time in social and community interaction than sons, and contributed almost three times the domestic work of their brothers. The fact remains, however, that the daughters' median contribution to housework was less than a third of their fathers'.

Figure 2: Median and mean daily minutes spent in domestic and child care activities, by family member and year

Note: Data is restricted to single-family households containing parents and co-resident teenage children aged between 15 and 19 years. Time spent is given in terms of main activities, not concurrent secondary activities.

Source: ABS 2006

Yet the same data can also be used to document considerable polarisation among young people, and the existence of a substantial minority of eminently "useful" teenagers. In Table 1, this is already visible in the much higher mean figures for domestic and care activities compared to medians. Among sons, for example, the 1992 mean of domestic minutes was more than double their median; in 2006, it was three times greater. When the mean daily minutes of domestic, child care and voluntary work and adult care are combined, daughters are shown to perform 77 minutes of such work in 1992 and 57 minutes in 2006. The corresponding figures for sons are 50 minutes in 1992 and 35 minutes in 2006. On their own, however, these figures too can give a misleading impression of what "average" teenagers do. As shown in Table 2, the most industrious tenth of teenagers in the 2006 sample reported an average of three hours spent on domestic or child care tasks daily - the same as their equally helpful fathers. In the families of these most "domestically useful" young people, the combined contribution of fathers and teenagers exceeded that of mothers by an hour and a quarter a day (assuming there was only one such teenager in the house). In contrast, in households of the fifth of teenagers who contributed nothing, mothers spent nearly twice the amount of time on household and child care tasks than did fathers. In all, the overall mean contribution of 43 minutes of housework and child care per day was obtained by averaging the activities of a small group of young people who shouldered a major share of household work, and a much larger group who contributed little or nothing. The same pattern is depicted in Figure 1: while most teenage sons are bunched up at the "domestically useless" end of the scale, some outliers performed 2, 3 or even 5 hours of domestic and child care work each day. Polarisation among teenage girls was less marked but still substantial. Fewer teenage daughters (but still over a fifth) reported little or no tangible contribution to the domestic work and child care in their household. But while their median contribution to such work amounted to 30 minutes a day, a significant minority of outliers contributed three or more hours a day.

| Top teen decile | Top teen quintile | Bottom teen quintile | Overall | Total no. of observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teenagers | 177 | 131 | 0 | 43 | 486 |

| Mothers | 282 | 279 | 234 | 252 | 464 |

| Fathers | 178 | 162 | 131 | 138 | 382 |

Note: Data is restricted to single-family households containing parents and co-resident teenage children aged between 15 and 19 years. Time spent is given in terms of main activities, not concurrent secondary activities.

Source: ABS 2006a

| 1992 % | 1997 % | 2006 % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Fathers | 9.5 | 7.3 | 5.2 |

| Daughters | 5.6 | 12.0 | 15.8 |

| Sons | 27.3 | 26.2 | 33.9 |

Note: Data is restricted to single-family households containing parents and co-resident teenage children aged between 15 and 19 years. Time spent is given in terms of main activities, not concurrent secondary activities.

Source: ABS 1992, 1997a, 2006a

Studies of adults' time use have shown significant changes over time, and a modest narrowing of gender inequality. We too have found significant long-term changes in gender and age-based divisions of labour. As shown in Figure 2, gender inequality in the distribution of caring and domestic work among the adults in our sample (comprising parents of co-resident teenagers) decreased slightly between 1992 and 2006. The mothers still performed more than twice as much of this work as fathers, but while mothers gradually decreased their large contribution, fathers first decreased and then substantially increased theirs. During the same period, not only did the time teenagers spend in domestic and child care activities gradually decline, it also decreased as a proportion of the average parent contribution. One measure of this pattern can be seen in Table 3, which shows the relative proportion of fathers, daughters and sons who reported doing no housework or child care. In 1992, 9.5% of fathers were in this category, 5.6% of daughters and 27.3% of sons. By 2006, the proportion of housework-free fathers was nearly half that of 1992, but the proportion of daughters almost tripled to 15.8%, and that of sons rose to 33.9%.

Were teenagers perhaps increasingly preoccupied by other productive endeavours? In Table 1 we combined employment, education, domestic, child care, voluntary and adult care and purchasing into one approximate category of "productive activities". On this measure of primary activity, the mean contribution of fathers in our sample slightly decreased and the contribution of mothers slightly increased over the 14 years, but was roughly the same at almost nine hours per day. The mean contribution of sons fell by 25 minutes per day between 1992 and 2006 to just under 6 hours. In proportional terms, it was the mean contribution of daughters that changed most markedly: it fell by 49 minutes a day to just over 6 hours a day. It is likely that counting both primary and secondary concurrent activities, as Craig and Bittman (2008) did, would add further complexity to the findings, and in particular enhance the contribution of mothers.

We have conducted a number of statistical tests to see whether there are any factors that could explain the huge variability in the teenagers' usefulness. There are numerous methodological difficulties in modelling teenagers' domestic and child care work and, without going into great detail, these are associated with the large number reporting no contribution and the associated skewness of the distribution (as shown in Figure 1). We divided teenagers into quintiles and performed an ordinal logistic regression to try to identify variables that increased the likelihood of a teenager being in a higher quintile. In a model that combined samples from all years, we found that the odds of daughters being in a higher domestic and child care quintile were 2.5 that of sons (p < .01), while other variables (mentioned below) were held constant. Teenagers from the 1992 sample had odds of being in a higher quintile 1.7 times greater than those from 2006 (p < .01). while the odds of teenagers from 1997 being in a higher quintile were 1.5 times that of those from the 2006 sample (p < .01). Having one or more family members with a disability increased the odds 1.4 times (p < .01). For each diary day that was a weekend, the odds of a teenager being in a higher quintile increased 1.4 times (p < .01). Teenagers not residing in a major city were 1.3 times more likely to be in a higher domestic and child care quintile (p < .05).7 Parent's highest level of education achieved, their single/partnered status, income, and their daily minutes of paid work had no statistically significant influence on the domestic and child care contributions of their teenage children. Similarly, the presence of a child under 14 in the household and a teenager's status as either being "independent" or "a dependent student" had no bearing on their location in quintiles of average daily minutes of domestic and child care activities contributed.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the three national ABS time use surveys found that young people's contributions to their households varied significantly, with some doing a great deal and others little or nothing. Against this diversity, teenagers' aggregate contributions to household and caring work were small and falling. Increasing gender equality among 15-19 year olds living with their parents was manifested in girls becoming more "domestically useless", like their brothers, rather than in boys doing more. If paid and unpaid work as well as education are included in overall productive activity, the disparity between parents and teenagers lessens significantly. Yet, here again, daughters are becoming more like sons, rather than retaining an intermediate status as "useful housechildren".

These findings are significant for a number of reasons. Given the considerable disparity in teenagers' contributions to household and caring work, they suggest that the ABS should follow the Eurostat (2004) recommendation to include those aged 10 years and over in future time use surveys. For the same reason, schemes designed to plot transitions between school and "work" (such as Vickers, Lamb, & Hinkley, 2003), need to take account of young people's differing participation in unpaid productive activities. Finally, the findings suggest that time use studies should more often examine both gender and generational dynamics of household divisions of labour and resources.

Despite their significance, statistical analyses cannot answer many important questions regarding children and work. Even the definition of what constitutes "work", or productive activity more generally, is highly contested; it is not simply a matter of researchers clarifying assumptions and tightening definitions. For example, "hygiene" and "communication associated with recreation and leisure" are classified under the broader categories of "personal care" and "recreation and leisure" respectively, but some young people would regard self-fashioning and creating and maintaining social networks as essential and productive cultural activities. Similarly, as every parent knows, who should cook the dinner and who should be entitled to have their clothes washed and ironed cannot be settled once and for all, but is subject to constant negotiation and contestation. Finally, even robust statistical findings on the extent of time spent on particular tasks are not sufficient in illuminating household relations of power and meanings of work, and indicating whether a teenager cleaned the bathroom under duress or of their own initiative (Solberg, 1997). For these reasons alone, our findings need to be set in the context of research from several academic disciplines, using a range of methodological approaches, and drawing on both qualitative and quantitative sources of evidence.

What are some policy implications of this study? Current debates regarding citizen's equitable participation in public life emphasise that the distribution of domestic and caring work needs to be addressed if adult women are to contribute to their full potential. Among the range of possible solutions to easing women's "double burden" of paid and unpaid work is the creation of family-friendly workplaces; shared parenting and household work; provision of social services, maternity and parental leave; purchase of meals and cleaning services; and the employment of nannies and housekeepers. The same range of policies and strategies, it is increasingly argued, is at the heart of maintaining sustainable birth rates. The distribution of responsibilities and entitlements between the generations too is profoundly influenced by policy- and market-related issues. The length of the school day and year; the setting of homework; the structure, funding and costs of education systems; youth labour markets; and the extent to which youth cultures are mediated through consumer purchases, are all significant. But so too is the way in which young people and their parents understand and divide chores and responsibilities at home. Just as there are households where couples practice different gender distributions of work and responsibility, so there are ones where different models of age relations apply. Some are more conducive to mothers' and fathers' participation in public life and feasible childrearing, others are not.

Endnotes

1 In that study, the definition of "work" included any jobs or work activities identified as such by participants, with the exception of routine household tasks and schoolwork. This broad definition was intended to capture both conventional work arrangements and work that was one-off, temporary or short-term. It did not exclude work on the basis of who the work was done for, or whether it received financial remuneration. The survey thus captured "conventional" paid employment, regular part-time work, casual work, one-off jobs, work for the family (excluding routine household tasks) - such as helping out in a family business or on a family farm, helping parents do their work from home, or looking after a sibling while parents are at work - and work for neighbours or community-based organisations, including volunteer activities (Fattore, 2005).

2 The contrast between "useful" and "priceless but useless" children is elaborated in Zelizer's (1985) influential book, Pricing the Priceless Child.

3 See, for example, the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) study - funded by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research <www.melbourneinstitute.com/hilda>; and Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) - conducted in partnership between FaHCSIA, the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the ABS, <www.aifs.org.au/growingup>.

4 The Confidentialised Unit Record Files (CURFs) from the expanded time use surveys 1992, 1997 and 2006 (ABS, 1992, 1997a, 1997b, 2006a, 2006b) consist of unidentified individual statistical records containing information on variables including, but not limited to, household items and services used, age of youngest child in household, state (partially aggregated), Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) (relative disadvantage), capital city and rest-of-state identifiers, age (in five-yearly intervals), sex, marital status, birthplace, birthplace of parents, labour force details, occupation, student status, educational achievement, details of income and source of income, disability, carer status, use of child care in the household, quarter of year, day of week, start and finish time of activity episodes, length of episode, primary and secondary activities, location of activity episode, mode of transport, and social context and for whom activity is done. To give an example of the scope of the survey, the 2006 sample contained 6,902 people from 3,626 households who reported 381,355 episodes from 13,617 person days.

5 The categories and other details of the surveys are described in the relevant Users' Guides (ABS, 1997b, 2006b).

6 "Median" refers to the amount contributed by the person in the middle of the whole group when its members are ranked by the size of their contributions. "Mean" refers to the total amount of contributions divided by the number of people in the sample.

7 We also ran the model with the amount of time spent in education and employment as variables to control for their influence on domestic and child care activities over the years. While they had a significant effect on teenagers' domestic and child care work (to be expected as they are mutually exclusive as primary activities), they did not temper the effects of the year in which the sample was drawn from.

References

- Alsaker, F. D., & Flammer, A. (Eds.). (1999). The adolescent experience in twelve nations: European and American adolescence in the nineties. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1992). Time use survey 1992: Basic CURF (CD No. 1831). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1997a). Time use survey 1997: Expanded CURF, RADL (CD No. 1830). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1997b). Time use survey, Australia: Users' guide 1997 (Cat. No. 4150.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006a). Time use survey 2006: Expanded CURF, RADL (CD No. 2522). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006b). Time use survey, Australia: Users' guide 2006 (Cat. No. 4150.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2009). Australian social trends, March 2009 (Cat. No. 4102.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Bittman, M. (1991). Juggling time: How Australian families use time. Canberra: Office of the Status of Women, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Bonke, J. (1999, October). Children's household work: Is there a difference between girls and boys? Paper presented to the IATUR Conference: The State of Time Use Research at the End of the Century, University of Essex, Colchester, UK.

- Carter, M. (2007). Who cares anyway: Negotiating domestic labour in families with teenage kids. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Swinburne Institute of Technology, Melbourne.

- Craig, L. (2006). Children and the revolution: A time-diary analysis of the impact of motherhood on daily workload. Journal of Sociology, 42(2), 125-143.

- Craig, L. (2007). Contemporary motherhood: The impact of children on adult time. Hampshire: Ashgate.

- Craig, L., & Bittman, M. (2008). The incremental time costs of children: An analysis of children's impact on adult time use in Australia. Feminist Economics, 14(2), 59-88.

- Dodson, L., & Dickert, J. (2004). Girls' family labor in low-income households: A decade of qualitative research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(2), 318-332.

- Eurostat. (2004). Guidelines on harmonised European time use surveys (Working Papers and Studies). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Fattore, T. (2005). Children at work. Sydney: New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People.

- Folbre, N., & Bittman, M. (Eds.). (2004). Family time: The social organization of care. London: Routledge.

- Gauthier, A. H., & Furstenberg Jr, F. F. (2000). Inequalities in the use of time by teenagers and young adults. In K. Vleminckx, & T. M. Smeeding (Eds.), Child well-being, child poverty and child policy in modern nations (pp. 175-197). Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Gill, G. K. (1998). The strategic involvement of children in housework: An Australian case of two-income families. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 39(3), 301-315.

- Goldscheider, F. K., & White, L. J. (1991). New families, no families? The transformation of the American home. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Goodnow, J. J., & Lawrence, J. A. (2001). Work contributions to the family: Developing a conceptual and research framework. In A. J. Fuligni (Eds.), Family obligations and assistance during adolescence (pp. 5-22). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Hofferth, S. L., & Sandberg, J. F. (2001). How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 295-308.

- Industrial Relations Victoria. (2001). Children at work? The protection of children engaged in work activities. Policy challenges and choices for Victoria. (Victorian Issues Paper). Melbourne: Industrial Relations Victoria.

- Larson, R. W., & Verma, S. (1999). How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 701-736.

- Lee, Y-S., Schneider, B., & Waite, L. J. (2003). Children and housework: Some unanswered questions. In K. B. Rosier (Ed.), Sociological studies of children and youth: Vol. 9 (pp. 105-125). Stamford, CN: JAI Press Inc./ Ablex Publishing Corp.

- Noble-Carr, D. (2002). Young carers research project: Final report. Canberra: Department of Family and Community Services. Retrieved from <www.fahcsia.gov.au/sa/carers/pubs/YoungCarersReport/Pages/default.aspx>.

- Ridge, T. (2007). It's a family affair: Low-income children's perspectives on maternal work. Journal of Social Policy, 36, 399-416.

- Solberg, A. (1997). Negotiating childhood: Changing constructions of age for Norwegian children. In A. James, & A. Prout.(Eds.), Constructing and reconstructing childhood (2nd Ed.). London: Falmer Press.

- Textile, Clothing & Footwear Union of Australia Victoria. (2002). Submission to the Senate Employment Workplace Relations and Education Legislation Committee Inquiry into provisions of the Workplace Relations Amendment (Improved Protection for Victorian Workers) Bill 2002. Melbourne: TCFUA Victoria.

- Vickers M., Lamb, S., & Hinkley, J. (2003). Student workers in high school and beyond: The effects of part-time employment on participation in education, training and work (LSAY Research Report No. 30). Melbourne: ACER.

- Williams, P., Bridge, K., & Pocock, B. (2009). Kids lives in adult space and time: How home, community, school and adult work affect opportunities for teenagers in suburban Australia. Health Sociology Review, 18(1), 79-93.

- Zelizer, V. A. (1985). Pricing the priceless child. New York: Basic Books.

Miller, P., & Bowd, J. (2010). Do Australian teenagers contribute to household work? Family Matters, 85, 68-76.