Children in poverty

Can public policy alleviate the consequences?

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

April 2011

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Child poverty is persistent throughout the world; even in many wealthy countries. Among Western industrialised countries, the United States has high child poverty rates (about 20% in 2009) as well as high income inequality. In recent years, two US policies to address child poverty have received support: early intervention to improve the health and development of young children, and employment-based financial incentives and work supports for low-income parents. Both types of policy are well-supported by high-quality research, a welcome trend toward evidence-based policy. But, they are not enough. In this paper, I argue that two features of the predominant theory of change in US poverty policy limit our ability to tackle the problem. First, we define poverty narrowly as lack of income or economic hardship; by contrast, the European Union and Australia consider social exclusion/inclusion to be the core problem to be addressed by policy. Second, we focus primarily on changing individual behaviour rather than also changing the economic and social structural conditions that lead to high rates of child poverty.

I begin by considering what we mean by poverty and assumptions about the causes of poverty. I then discuss current knowledge about early childhood intervention and employment-based incentives for parents as examples of well-documented, evidence-based policies designed to reduce poverty or its effects. Finally, I consider the implications of theories of change for future policies as well as for future directions in research.

Defining poverty

Low income

Absolute definitions

Annual income is the most common guidepost for assessing poverty within and across nations. The United States uses an absolute definition. The federal poverty threshold is an estimate of the minimum income needed by an individual or family to avoid serious material hardship. It originated in 1963 from estimates of the minimum food budget required for adequate nutrition, using the assumption that food constituted about one-third of a family’s expenditure. It varies depending on family size and is adjusted annually for inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (see Schiller, 2008, for a detailed explanation). In 2009, the threshold for a family of four people was $22,050. The measure has a number of faults, including the fact that it is not adjusted for regional differences in cost of living or for in-kind benefits received as part of public assistance (Citro & Michael, 1995), but it does allow comparisons of trends over time for individuals and for groups of people. The US government is currently publishing a revised version of the poverty definition in an effort to correct some of these flaws, but it continues to be an absolute threshold based on annual income.

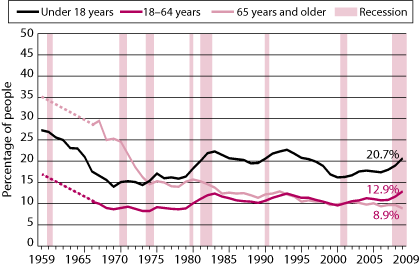

In Figure 1, the trends for poverty among US children and adults from 1959 to 2008, using the federal definition, are shown. The percentage of children living in families with incomes below the poverty line declined until 1969, rose to high levels in the 1980s and again in the 1990s; in 2009, 21% of US children lived in poor families (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2010). Income is volatile by this definition, with many families moving in and out of poverty over their children’s lifetimes, but some families remaining in chronic poverty over many years. Single-mother households and families of colour (both African-American and Latino) are disproportionately represented among the poor, especially the chronically poor (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2010).

Figure 1 Proportion of individuals living below the US poverty threshold, 1959–2009

Notes: The data points are placed at the midpoints of the respective years. Data for people aged 18–64 and 65 and older are not available from 1960 to 1965.

Source: US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 1960 to 2010 Annual Social Economic Supplements. Reproduced from DeNavas-Walt et al. (2010).

Relative definitions

In contrast to the absolute definition of poverty used in the United States, the OECD and most European countries use a relative definition based on some percentage of the median income in the country. This relative index generates a higher poverty rate in the US than does the absolute index. Cross-national comparisons of income poverty in 2000 in 24 OECD countries, defined as family income lower than 50% of the median income, showed that the lowest rates are in Denmark and Finland (less than 3%) and the highest rate is in the United States (22%). The rates for Australia and the United Kingdom were 12% and 17% respectively. In 17 of the 24 developed countries, however, child poverty increased from 1990 to 2000 (UNICEF, 2005). During the period from 1998 to 2008, the rates of child poverty in the UK declined substantially (Waldfogel, 2010).

Social exclusion

People living in income poverty often suffer a broad range of disadvantages that are summarised in the concept of social exclusion. In 1984, the then European Economic Community (1985) adopted an expanded definition of poverty that informed the idea of social exclusion: “For the purposes of this Decision ‘the poor’ shall be taken to mean persons, families and groups of persons whose resources (material, cultural and social) are so limited as to exclude them from the minimum acceptable way of life in the Member States in which they live” (Article 1.2). Scholars have struggled to produce a precise definition of social exclusion. One such effort by Kahn and Kamerman (2002) seems to capture its many facets: “[inequalities in] basic living; family economic participation; housing; health; education; public space; social participation; as well as the subjective experience of social exclusion” (p. 27). Reducing social exclusion became integral to the policy goals of the United Kingdom and Australia as well as those in other member states of the European Union, but the term is almost never used in United States policy discussions. Although many components of social exclusion may be affected by increased income alone, striving to reduce social exclusion leads to a broader range of policy strategies addressing the cultural and social conditions associated with poverty, as well as individuals’ perceptions of inclusion. For example, governments must address ethnic, gender and racial bases of social exclusion that go well beyond income.

The focus on social exclusion has also led governments to address child wellbeing broadly; considering the whole web of conditions that are often a consequence of (as well as being determined by) income poverty (Huston & Bentley, 2010). For example, in its 2007 report, the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre went well beyond material deprivation to examine five additional areas of child wellbeing: health and safety, educational wellbeing, family and peer relationships, behaviours and risks, and subjective wellbeing. The United States and the United Kingdom ranked lowest among 21 OECD countries on the overall index of child wellbeing. As the data were based on the years from 1990 to 2000, they did not reflect the possible effects of the Labour Party’s program to reduce child poverty in the UK. Australia was not included in the analysis (UNICEF, 2007).

Summary

In the developed world, poverty is typically defined by a family’s current income compared to an absolute standard designed to represent the amount needed for a minimally adequate standard of living (absolute poverty) or to the median incomes of people in the same country (relative poverty). Although income poverty is correlated with material hardship (e.g., food insufficiency, inadequate housing, lack of access to medical care), it is not a perfect index of such hardship (Mayer & Jencks, 1989).

Defining poverty as “relative” assumes that poverty is more than material deprivation—that it reflects a person’s economic situation relative to the expectations and norms of her or his society. The focus on social exclusion rather than income per se expands both theoretical and policy concerns to the web of personal and institutional barriers that are correlated with low incomes in modern industrialised societies. Understanding how poverty affects children’s development and how policies may alleviate some of those effects requires consideration of the material, social and institutional conditions associated with poverty.

Causes of poverty

Theories about the causes of poverty fall into two broad classes: social selection and social causation (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). According to the social selection hypothesis, individuals succeed or fail to climb the economic ladder largely because of individual characteristics, including ability, skills, motivation, and mental and physical health. Children born into poor families are disadvantaged by having parents with low levels of the qualities needed for acquiring income, and the children in turn have relatively poor intellectual and social skills as a result of both genetic and environmental influences provided by their parents. Some version of this theory informs politically conservative views that the poor should be able to help themselves and that providing assistance without requiring behaviour change perpetuates poverty.

Most poverty policies in the United States are based on social selection—they are designed to change the skills and behaviour of individuals who are poor or who are likely to become poor. In Table 1, some illustrations of such policies are shown. Poverty and welfare policies directed at adults are intended to: increase individuals’ employment through improving their skills, motivation and effort; reduce “dependence” on welfare; and promote marriage and financial responsibility for children. Some of the major policies for young children are designed to improve early developmental competencies and promote “school readiness”.

| Targets of policies | Sample policies |

|---|---|

| For adults | |

| Job skills and abilities | Job training |

| Work motivation and behaviour | Sanctions and work requirements for welfare |

| "Dependence" on welfare | Time limits on eligibility |

| Marriage | Healthy marriage promotion programs |

| Parental responsibility | Child support enforcement |

| For children | |

| Early development | Home visiting programs |

| School readiness: literacy and number skills | Early childhood education programs |

| Behaviour problems | Parent training programs |

According to the social causation hypothesis, economic and social institutions and structures offer opportunities and barriers that lead to poverty or affluence. The availability or lack of jobs paying high wages or requiring particular skills, for example, can have a strong impact on the likelihood that individuals will be poor. Some version of this view informs politically liberal views that emphasise such policies as living wage and anti-discrimination laws. Examples of such policies are shown in Table 2. They include those designed to: improve work opportunities and job availability, assure adequate wages for work, prevent race and gender discrimination, and assure developmental and educational opportunities for children and adults.

| Targets of policies | Sample policies |

|---|---|

| For adults | |

| Opportunities for work, job availability | Job creation |

| Low wages | Minimum or living wage requirements, wage supplements |

| Race and gender discrimination | Anti-discrimination policies |

| Child care availability | Subsidies and publicly supported child care |

| Educational opportunities | Grants for education |

| For children | |

| Quality of child care | Quality initiatives and support |

| Educational opportunity | "Ready" schools |

| Neighbourhood resources | Parks, safety measures |

Conger & Donnellan (2007) argued for an interactionist view incorporating both social selection and social structure; that is, the recognition that individuals are limited by the social and institutional opportunities available to them, but that people’s own abilities and personal characteristics also influence the ways in which they use (or do not use) those opportunities.

I turn now to examples of two US policies that are evidence-based and widely accepted as effective: early childhood intervention and employment-based welfare for low-income parents. I chose these examples because my long-time involvement in research on these topics has led me to think extensively about their strengths and weaknesses. For both policies, there is good empirical evidence that they produce socially significant improvements in children’s lives, but the gains are not sufficient to overcome the substantial inequalities between the poor and the “not poor” in the US.

Early childhood interventions

Over the past fifty years, policy-makers and scholars studying children have increasingly come to recognise the importance of experiences in the first few years of life, including the prenatal period, for children’s long-term health and development. The neurological architecture of the brain is formed in the first two or three years through a complex set of interactions between genes and experience. “Genes provide the initial blueprint for building brain architecture, environmental influences affect how the neural circuitry actually gets wired, and reciprocal interactions among genetic predispositions and early experiences affect the extent to which the foundations of learning, behavior, and both physical and mental health will be strong or weak” (Shonkoff, 2010, p. 357).

Early developmental lags

In the 1960s, policy-makers and the public became aware that children living in poverty entered school at age 5 with fewer skills than their more affluent counterparts. But we now know that developmental differences associated with family income begin much earlier than age 5. In the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), data were collected on a representative sample of 11,000 children born in 2001 in the United States. The Bayley Cognitive Assessment, a measure of overall developmental level, was administered at 9 months and again at 24 months. The comparisons of average scores of children from families with low incomes (less than 200% of the poverty threshold) to those of children from higher income families are shown in Figure 2. The zero point on the graph represents the average for children from non-poor families. At 9 months, children in low-income families were slightly behind; by 24 months, the difference was much larger—over half of a standard deviation (Halle et al., 2009). That is, only about 30% of the children in low-income families scored at or above the average for those from more affluent families. Less pronounced but significant disparities also appeared for children’s health and positive social behaviour. Although there are undoubtedly many reasons for these differences, the important point is that they exist; children in low-income families are already at a considerable developmental disadvantage by the time they reach their second birthdays.

Figure 2 Disparities on the Bayley Cognitive Assessment for infants from high- and low-income families, by age of child

Source: Halle et al. (2009)

Relationship between low family income and later functioning

The environments experienced by children in poverty affect not only early developmental progress, but also have lasting impacts on intellectual development. The early years are a “sensitive period” for environmental influences; that is, experiences in these years have particularly strong and lasting effects. Poverty or low family income during the first five years of life is more deleterious for intellectual development than is poverty later in childhood or adolescence. In one large longitudinal study, family poverty during early childhood predicted low achievement test performance in the school years (ages 6–12); once early childhood income was taken into account, family income during the school years was not related to achievement (Votruba-Drzal, 2006). Even longer lasting effects were established in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a longitudinal study that has been following families since 1968. Poverty during the first five years of life predicted poor school performance throughout the school years as well as low adult educational attainment; family income in later periods of childhood and adolescence did not add predictive power (Duncan, Ziol-Guest, & Kalil, 2010).

Although poverty in the early years also influences social behaviour—both positive and problem behaviour—there is less evidence that its effect occurs during a sensitive period. For example, income in both the early years (ages 0–5) and middle childhood (ages 6–12) had cumulative effects on behaviour problems at ages 7–12 (Votruba-Duzal, 2006). Similarly, in the PSID, poverty in adolescence predicted adult psychological distress, arrests and non-marital child bearing, even with earlier poverty controlled (Duncan et al., 2010).

The mechanisms by which low-income environments affect early development are just beginning to be understood. Shonkoff (2010) proposed a developmental model incorporating three types of early environments—human relationships; physical, chemical and built environments; and nutrition—that interact with genes to produce biological “memories” with long-term consequences for adaptive behaviour and responses to stress. The model reflects the fact that we have finally discarded simplistic nature vs nurture concepts, as investigators demonstrate some of the biological mechanisms by which genes are translated into observable characteristics through complex interactions of biological and environmental influences.

Early interventions

In the US and the UK, early intervention has been one policy response to the evidence regarding the importance of early childhood experiences. In the US, Head Start was launched in 1965 as a large federal program to enrich the experiences of children about to enter school, and it continues 45 years later. During the same time period, a number of demonstration programs, primarily for children in the 3–5 year old age range, were undertaken to gain better understanding of what types of intervention might be effective. In many cases, the evaluations of these programs were random or quasi-random assignment experiments, allowing comparisons of children who had access to the interventions with comparable children who did not.

I cannot do justice to the large body of research investigating the effects of these preschool interventions, but two generalisations emerge. First, carefully designed intensive interventions can produce improvements in school achievement and social behaviour. Across 20 studies reviewed by Karoly, Kilburn, and Cannon (2005), school achievement for children in the intervention programs was superior to achievement by control group children. The average difference was about one-third of a standard deviation. Two of the most carefully studied programs, the Perry Preschool Project and the North Carolina Abecedarian Program, had lasting effects on educational attainment, labour market participation and, in one case, reduced crime, well into adulthood (Karoly et al., 2005). Economic analyses of these interventions consistently show long-term positive cost–benefit ratios (Heckman, 2006; Karoly et al., 2005).

Large-scale national programs such as Head Start produce more modest positive effects, and there is considerable debate about the duration of the initial advantages produced by the program. In the National Head Start Evaluation Study, applicants for Head Start were randomly assigned to be admitted to a Head Start program or to be in a control group. By the end of the year, children in the Head Start group (especially 3-year-olds) had better language and literacy skills, fewer behaviour problems and better health, and received less harsh parenting than control group children (Administration for Children and Families [ACF], 2005), but most of the differences were no longer evident by the end of first grade (ACF, 2010). Some commentators interpret these findings as evidence that Head Start in its current form is ineffective, but others point out that the study design was corrupted by the fact that many children in the control group attended preschool programs, including Head Start programs that were not part of the study.

Perhaps age 3 is too late to begin. One of the most effective demonstration programs was the Abecedarian study in North Carolina, in which children were given high-quality full-time child care from the age of six weeks to kindergarten entry (Campbell et al., 2008). Large-scale interventions using combinations of parent education and preschool programs for children from birth to 3 can produce positive effects, particularly for children’s health and social-emotional wellbeing. Sure Start is a community-based intervention in the UK providing a broad range of services to low-income families. The most recent evaluation shows that 3-year-olds in Sure Start communities displayed more positive social behaviour and independence, and their parents exhibited more positive parenting practices and provided more stimulating home environments than was the case in comparison communities (Melhuish, Belsky, Leyland, & Barnes, 2010). The Early Head Start program in the US offers a similar mixture of services. An early evaluation indicated positive effects on children’s development and the quality of the family environment, but only in communities where the program was fully implemented (Love et al., 2005). Finally, nurse home visiting programs offering services during pregnancy and after birth to high-risk parents can also produce improvements in child health and development (Olds, Sadler, & Kitzman, 2007).

Summary

Scholars and policy-makers have been persuaded by this evidence that early interventions are a good societal investment because they reduce the disadvantages associated with poverty during the first five years of life. James Heckman (2006) summarised the argument: “Investing in disadvantaged young children is a rare public policy initiative that promotes fairness and social justice and at the same time promotes productivity in the economy and in society at large. Early interventions targeted toward disadvantaged children have much higher returns than later interventions such as reduced pupil-teacher ratios, public job training, convict rehabilitation programs, tuition subsidies, or expenditure on police” (p. 1902). Nonetheless, early interventions alone do not and probably cannot solve many of the problems associated with poverty. They are not designed to reduce poverty in the short run, but to eliminate some of its effects on children’s intellectual, behavioural and health problems, with the aim of reducing the likelihood of poverty in the next generation.

Welfare and employment policies

A second major policy approach is designed to reduce poverty in today’s families by increasing parents’ employment. Policy-makers in the US and other developed countries have confronted three basic facts over the 20th century: (a) earnings are the principal source of income for the great majority of families everywhere; (b) single-parent families, especially those headed by single mothers, are much more vulnerable to poverty than are two-parent families; and (c) the demands of employment conflict with child-rearing responsibilities, making it difficult for a parent to do both. In most of the 20th century, policy responses to this information typically involved providing income and in-kind assistance (e.g., housing, medical care) that was intended to allow single mothers to care for their children at home. In the United States (and elsewhere), this approach became less viable over time, in part because it typically did not raise single-mother families out of poverty and in part because mothers of young children from all economic groups were entering the labour market in larger and larger numbers. At the same time, “welfare” became more politically unpopular, as the majority of its recipients shifted from being widows to being divorced and never-married mothers who were portrayed to the public as lazy and undeserving. Race also played a role. Although the majority of recipients were white, the public image was an urban African-American woman with numerous children born out of wedlock (Quadagno, 1994).

Work as the goal

Ultimately, the emphasis of US welfare policy moved away from offering meagre support to parents who were not working towards encouraging employment. In the 1990s, both carrots, in the form of earnings supplements, and sticks, in the form of sanctions and time limits on benefits, were instituted to promote this goal. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) was expanded following then President Clinton’s campaign slogan that policy should “make work pay”. In 1996, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) made major changes in federal welfare policy, emphasising employment and limiting welfare benefits to a total of five years in a parent’s lifetime. The label for the welfare legislation—”personal responsibility”—clearly reflected the underlying theory of change; the goals were to change the employment, marital and parenting behaviour of poor individuals. A number of European countries, particularly the United Kingdom, also shifted their policies towards encouraging employment, though the policy tools were more generous and less punitive than were those in the US (Knijn, Martin, & Millar, 2007).

As the winds of policy change began to blow in the 1980s, a number of large, random-assignment studies were initiated to test the types of policies being discussed in the US. Initially, the major questions concerned the possible impacts of policy changes on parents’ employment, earnings and use of welfare (see Gueron & Pauly, 1991), but eventually attention turned to asking about the effects on children, who were, of course, the intended beneficiaries of public assistance for low-income parents.

The Next Generation Project

The Next Generation Project was a collaborative effort that took advantage of the variation in the policies tested in different experiments to compare the impacts of different policy features on children’s development. The policy features examined included mandatory vs voluntary participation in job search, job training, time limits on eligibility for cash benefits, earnings supplements and enhanced child care assistance. These studies showed consistently that simply moving from welfare to a job did not increase family income on average; hence, work alone did not move families out of poverty (Bloom & Michalopoulos, 2001). Programs that offered earnings supplements, however, did raise family income, and these were the programs that also led to improvements in children’s school performance, especially for children who were in the preschool years when their parents entered the program (Morris, Duncan, & Clark-Kauffman, 2005). Similarly, policies that offered enhanced child care assistance increased children’s enrolment in centre-based child care, which in turn led to better school achievement and to reductions in externalising problem behaviour once they entered school (Crosby, Dowsett, Gennetian, & Huston, 2010; Morris, Gennetian, Duncan, & Huston, 2009).

In the original conceptual model guiding the Next Generation studies, we expected changes in parents’ sense of wellbeing to be an important pathway for effects on children. A large body of non-experimental literature supports the hypothesis that the negative effects of poverty or income loss on children’s psychological wellbeing are mediated by parents’ stress (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; McLoyd, Aikens, & Burton, 2006). In the policy experiments, parents’ wellbeing depended on the ages of their children—parents who had preschool-aged children reported increased depressive symptoms when they were in programs requiring employment, especially when they were expected to move quickly into a job. Those whose children were school-aged, on the other hand, reported lower levels of depressive symptoms, and their children’s social behaviour also improved (Morris, 2008; Walker, Huston, & Imes, 2010). People with preschool children probably encountered more difficulties in reorganising family routines and arranging satisfactory child care, especially at short notice, than did those with school-aged children.

These welfare and employment experiments are consistent with the longitudinal studies described above in suggesting that the effects on children vary by child age. The most positive long-term effects of increased income and centre-based child care on later achievement and intellectual development occurred for children in the preschool years (3–5 years old). Positive effects on children’s social behaviour also occurred in middle childhood (roughly ages 6–11 years). For adolescents, however, mothers’ entry into required employment led to somewhat negative impacts on staying in school and behaviour problems (Gennetian, Duncan, Knox, Vargas, & Clark-Kauffman, 2004).

New Hope: A different philosophy

New Hope was one of the experiments in the Next Generation group of studies, but it differed from the welfare studies in goals and philosophy. It was a community-initiated poverty-reduction demonstration program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, based on the assumption that poor people want to work and that public policy should provide work supports enabling them to do so. The founders viewed employment as the route out of poverty for most people and argued that, “if you work, you should not be poor”. The underlying theory of the causes of poverty was more interactionist than those of most welfare programs, attributing poverty at least partially to the economic and structural conditions that lead to low wages.

The New Hope program was designed to offer benefits that would lift full-time workers’ incomes above the poverty threshold and would provide the basic work supports needed to sustain employment—specifically, child care and health care. For people who worked full-time (30 hours a week), it offered earnings supplements that would bring their income above the poverty threshold, child care subsidies, and health care subsidies. Project representatives provided respectful assistance to help people find jobs, organise child care, and the like. If a participant could not find a full-time job, the program offered access to community service jobs that paid the minimum wage and entitled the individual to New Hope benefits.

The organisers of New Hope intended it to be a model policy that could be adopted on a large scale. To make their case, they contracted an independent research organisation, MDRC in New York, to undertake an evaluation using the most stringent research method—random assignment. To qualify for New Hope, applicants had to be at least 18 years old, have earnings below 150% of the poverty threshold, live in the target areas in Milwaukee, and be willing to work full-time. Both men and women were eligible, whether or not they had children. Applicants who met these criteria were assigned by lottery to be in either the New Hope group that could access the program services, or in a control group that could not. Both groups could use other services in the community.

Of the 1,356 adult participants in the New Hope study, 745 had at least one child aged 1–10 years at random assignment. Our research team studied the progress of those children over eight years after random assignment. The New Hope benefits were available for three years, so our evaluation tested effects on children during and after the treatment group had access to those benefits. As well as examining parents’ economic and emotional wellbeing and parenting behaviour, we assessed the children’s academic achievement, socio-emotional wellbeing, non-parental care, and extracurricular activities. Thomas Weisner, an anthropologist who was part of the New Hope team, directed an ethnographic study that gathered repeated intensive qualitative interviews and observations among a randomly selected subset of 44 program and control group families in order to provide a complement to the large-scale quantitative assessments.

The results have been presented in detail in several articles and in two books, Higher Ground: New Hope for Working Poor Families and their Children (Duncan, Huston, & Weisner, 2007) and Making It Work: Low Wage Employment, Family Life, and Child Development (Yoskikawa, Weisner, & Lowe, 2006). Two years after random assignment, children in New Hope families, compared to those in control families, had better achievement, higher levels of positive social behaviour (i.e., social skills, compliance, autonomy), and fewer behaviour problems (both externalising and internalising problems) according to their teachers (Huston et al., 2001). Many of these differences were maintained after the New Hope program ended (Huston et al., 2005; Miller, Huston, Duncan, McLoyd, & Weisner, 2008).

New Hope was an intervention with adults; why did it affect their children? Two pathways are supported in our analyses. First, New Hope produced modest improvements in family incomes, reducing the likelihood that the family would be officially “poor”. Reduced poverty would be expected to increase resources for children and enhance their developmental opportunities. Second, the program increased parents’ use of centre-based child care for younger children, and out-of-school structured activities for older children, providing care environments with better potential to promote positive development than the informal and unsupervised settings experienced by the control group children. Our qualitative data suggested a third vital component—respectful and useful services provided by staff, who were called “project representatives”. Participants talked frequently about the supportive environment in the New Hope offices, noting that representatives returned phone calls, offered useful information, and were available. One person said that the staff wanted you to succeed, contrasting them with the welfare office where they wanted you to fail. Parents’ access to social support and improved psychological wellbeing would be expected to carry over into their home lives and into warm and supportive interactions with their children.

Conclusions from work-based programs

Advocates for children and policy-makers were understandably alarmed about potential dangers for children if their single mothers were required to get and maintain employment. Advocates for welfare “reform” asserted that parents’ employment would not only better the economic position of the family, but would allow them to join the American mainstream and provide good models for children. Both were partially right and partially wrong. Overall, the experiments that tested policies requiring employment, even without additional income or centre-based care, showed very few deleterious effects on children. The worst fears of the naysayers were not realised, though we should be concerned that the policies did nothing to improve poor children’s wellbeing. At same time, these experiments demonstrated that employment-based policies can improve children’s lives if the family moves out of poverty, children have good child care and opportunities for structured out-of-school activities, the mother has time to arrange for the changes in family responsibilities when she starts work, and case workers provide respectful support.

There are two important caveats to these generalisations. First, the studies took place during a period of relatively low unemployment, raising questions about additional barriers faced by single mothers whose low levels of education and skills make them non-competitive in an economy with fewer available jobs. Second, children of different ages responded differently to parents’ participation in employment-related programs. Positive effects on achievement in elementary school were most consistent for children in their preschool years (aged 3–5 years old when their mothers entered the programs). Positive effects on social behaviour were most likely for children in the early school years at program entry. Negative effects on achievement and minor delinquent behaviour occurred for those in early adolescence (between about 11 and 13 years) at program entry (Morris et al., 2005). We have little information about the effects of these programs on infants and very young children under the age of 3 years.

As the results of these experiments were emerging during the 1990s, policy changes were already occurring. From 1995 to 2000, rates of employment among single mothers increased, the number of people receiving cash assistance (Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC] or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF]) declined markedly, and poverty among single mothers declined (Haskins, Primus, & Sawhill, 2002). Although some commentators attributed these patterns to changes in the welfare laws, several conditions coincided, making it difficult to single out one cause. First, unemployment rates were low, and jobs were fairly easy to find in most places. Second, during the same period that the welfare law was revised, work supports for low-income parents were expanded. The maximum benefit available from the federal EITC grew by 25%, from $3,110 in 1995 to $3,888 in 2000, and a number of states offered additional earnings tax credits within their state income tax systems. For example, the state of Wisconsin, where the New Hope study was conducted, offered a benefit that added approximately 25% of the federal benefit, depending on family size. Federal investments in child care and early education programs for children from low-income families doubled during the 1990s, extending child care assistance to many more children, albeit still not funding the majority of eligible children (Fuller, Kagan, Caspary, & Gauthier, 2002).

Theories of change

The two types of anti-poverty policies I have described here—early intervention and work-based programs for adults with low incomes—are among those considered most successful by scholars and policy-makers alike. Both are supported by extensive and methodologically strong policy research that documents their positive effects on children’s development as well as their positive cost–benefit ratios. Yet, both have produced only modest successes. Quality early interventions improve school performance by about one-third of a standard deviation, a result that is impressive but does not close the poverty gap. Large-scale programs—for example, Head Start—reduce the income gap in performance on pre-reading skills by about 45% (ACF, 2005), but much of this gain is not sustained. New Hope produced about one-fourth of a standard deviation improvement in school achievement, but gains gradually faded.

We can do a better job of creating effective policies by clarifying our theories of change; that is, the conceptual frameworks describing the causes of poverty, and the very definition of poverty itself. Such theories are typically not well articulated by policy-makers (or by anyone else), although they are implicit in the rhetoric and discussions of policy goals and choices.

Causes of poverty

Most of the US social policies that I have described are based on a social selection model. Both early interventions and welfare-to-work policies are intended to change the skills, motivations and behaviour of individuals. Early intervention programs are typically couched in language about increasing school readiness in the short run, and improving human capital and economic productivity in the long run.

The welfare law passed in 1996 also targets individual change. Its stated goals were to increase employment, reduce welfare “dependence”, and encourage marriage and parental responsibility. It was not explicitly designed to reduce poverty (Greenberg et al., 2002). Virtually all of the provisions in the law target the behaviour of individual adults—getting parents into jobs, removing the guarantee of cash supports, and requiring parents to assume financial responsibility for their children. There are no provisions for community service jobs or publicly supported work, nor are there any provisions for job creation or wage supports.

An interactionist theory of change is suggested by data from these experiments showing differential effectiveness for different groups of people and providing some information about how individual characteristics interact with available opportunities. In the New Hope study, the families who were most likely to increase work and income were those who began with just one barrier to employment (e.g., having preschool children, a low education, or a criminal record) (Duncan et al., 2007). Across all of the Next Generation studies, children in families with moderate levels of disadvantage, but not those with relatively high or low levels of disadvantage, showed increased school achievement and participation in centre-based child care as a result of parents’ participation in the employment-based programs (Alderson, Gennetian, Dowsett, Imes, & Huston, 2008).

Definitions of poverty based on social exclusion

Defining the problems of poverty as social exclusion rather than solely as deprivation of resources leads to a theory of change with a different balance of social causation and social selection as causes of poverty, to expanded targets of social policy, and to a broader range of goals for policy effects on children. Social exclusion is central to the discussions of poverty in the European Union and is articulated in poverty policy goals in the UK and Australia, among others. Often citing social exclusion, the British “war on poverty”, launched by the Labour government in the late 1990s, had three goals: promote work and make work pay; increase financial support for families; and support the early health, education and development of children (Waldfogel, 2010). Two of these—work promotion and early childhood development—are similar to the targets of US policies, but increased financial support for families distinguishes the UK goals from those in the US

The social exclusion approach also leads to an expanded scope of policy targets and approaches. It is concerned with basic material wellbeing and promoting employment as the principal avenue for families to move out of poverty, as well as improving current and future human capital. But a social exclusion perspective also leads to policy goals designed to reduce inequality and increase social participation and perceptions of belonging to the mainstream. Grouping a range of policy targets under one rubric—social exclusion—may facilitate the formation of integrated policies that cross the usual silo lines (e.g., across housing, education and health).

Implications for research

Poverty research rarely includes individuals’ perceptions of social exclusion or inclusion, but there is suggestive evidence that such perceptions may affect children’s responses to living in poverty. The modest improvements in income for New Hope families not only eased the pressures to provide basic material needs, but also contributed to parents’ and children’s feelings of social inclusion. In the ethnographic interviews, New Hope parents were asked how they used the increases in income provided by the program. They talked about meeting basic needs, but also of being able to provide a few “extras”. They felt good about being able to take their children for a fast food meal, buy a child a birthday present, or shop for new clothes instead of going to the thrift shop. One parent spent several hundred dollars on professional photographs of her son’s high school graduation, reflecting the importance of that milestone for her and her family. Being able to buy these “extras” made both parents and children feel part of the American mainstream—being like everyone else. And, it was this aspect of income that predicted improvements in children’s positive behaviour as well, possibly because it gave them a sense of belonging (Mistry, Lowe, Benner, & Chien, 2008). Our understanding of the processes underlying the effects of poverty could be enriched by more research that incorporates individuals’ perceptions of social inclusion.

Defining poverty as social exclusion leads to research investigating child wellbeing and rights as well as human capital goals for children. The objectives of early interventions are typically phrased as some version of school readiness—assuring that children have the skills needed to succeed when they enter “regular” school in kindergarten or first grade. The research and evaluation literature is rife with the term “child outcomes”. The ultimate justification for early interventions in the US is largely economic—raising children to be economically productive, tax-paying adults who will stay out of prison. It is not enough to show that a policy produces a safe, stimulating, loving environment; evaluators are required to show some lasting change in the child’s skills or behaviour. There is no doubt that economic productivity is an important goal in any society, but this orientation sometimes leads us to think about children primarily as economic products rather than as citizens with the right to a decent life and wellbeing, now as well as in the future.

Policy implications

Policies might be more effective if they were based on interactionist assumptions about causality—that individuals’ attributes interact with the economic and social context that they confront. Some of the employment-based policies tested in experiments addressed structural as well as individual barriers to generating income. Earnings supplements, for example, are designed to correct for wage inadequacies in the marketplace and the impact of tax policies that penalise low-wage workers. But work incentives and job training might be more effective if they were coordinated with job creation. In addition, policies to increase children’s school readiness might have more lasting effects if they were coordinated with schools’ readiness to build on the skills they bring.

In the United States, we do not have a coordinated or integrated child or family policy. Defining poverty more broadly to include the many facets of experience with which it is correlated might lead to more coherent and less piecemeal policies. Even within early childhood intervention, for example, policies for prenatal and postnatal health, home visiting, child care and early childhood education are fragmented, leading one group of investigators to suggest developing a “system of care” to encompass them (Astuto & Allen, 2009).

Because children are often left out of policy discussions, even when they are likely to be affected directly, some version of the European Union’s “mainstreaming” process might make children’s welfare more salient. “Mainstreaming” would require any new policy proposal to evaluate its impact on children—a Child Impact review. Mainstreaming would put children’s welfare into conversations about policies for such topics as housing and transportation, as well as the more obvious areas of education and public assistance. The need for such a policy was especially evident in many of the debates about changing the US welfare system, in which the arguments revolved around adult work and welfare receipt. Policy-makers sometimes cited the reduced numbers of welfare recipients as evidence of “success” after 1996, without considering the consequences for children who are, of course, the intended beneficiaries of financial support for parents.

Conclusion

Child poverty is a persistent problem in the developed world, particularly the United States, even though we have a standard of material wellbeing that is unprecedented in history. Poverty is typically defined as a lack of income or material resources, but social exclusion represents a different lens that leads to a broader range of policy solutions. Recent research has provided strong support for the effectiveness of early interventions in reducing or ameliorating some of the consequences of poverty for children by providing more stimulating and supportive environments, both at home and in early care and education settings. On another front, employment-based policies for parents that provide work supports in the form of wage supplements, child care and health care assistance can also lead to improved school performance and behaviour of children.

Despite their successes, these policies have not eliminated poverty or its consequences for children. I argue here that we can do a better job by examining the implicit and explicit theories of change underlying poverty policies. Policies aimed at income poverty, at least in the US, are designed primarily to change individuals by improving their skills, increasing their motivation and ability to be “self-sufficient” and adding to their human capital. Work supports for adults often use public funds to compensate for the inequities in the marketplace rather than changing the conditions that produce those inequities (e.g., low-wage jobs, discrimination). Defining poverty as social exclusion leads to a relatively stronger emphasis on policies designed to address the societal and institutional causes of poverty, and correspondingly less emphasis on changing individuals. In both cases, we should take seriously the point that social causation and selection based on individual attributes interact; individuals with different skills and personal characteristics use and respond to economic and social opportunities differently. Policies directed to both causal agents in the society and to changing individuals might be more successful than either alone.

The ultimate goal of US policies for children is often couched in human capital terms—increasing their readiness to profit from school and to become economically productive adults—partly because the underlying theory of change emphasises social selection and partly because these goals are persuasive to a broad range of citizens. A theory of change derived from social exclusion leads to goals for children that include not only human capital, but assurance of basic rights and wellbeing. The choice of goals goes beyond social science to underlying values of the society. Most developed societies, including the US, profess a strong belief in the importance of children’s wellbeing. Our policy evaluation criteria should reflect that belief.

References

- Administration for Children and Families. (2005). Head Start impact study: First year findings. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Administration for Children and Families. (2010). Head Start impact study: Final report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Alderson, D. P., Gennetian, L. A., Dowsett, C. J., Imes, A., & Huston, A. C. (2008). Effects of employment-based programs on families by prior levels of disadvantage. Social Service Review, 82(3), 361–394.

- Astuto, J., & Allen, L. (2009). Home visitation and young children: An approach worth investing in? Social Policy Report, 23(4), 1–22.

- Bloom, D., & Michalopoulos, C. (2001). How welfare and work policies affect employment and income: A synthesis of research. New York: Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation.

- Campbell, F. A., Wasik, B. H., Pungello, E., Burchinal, M., Barbarin, O., Kainz, K., et al. (2008). Young adult outcomes of the Abecedarian and CARE early childhood educational interventions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(4), 452–466.

- Citro, C. F., & Michael, R. T. (1995). Measuring poverty: A new approach. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- Conger, R. D., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175–199.

- Crosby, D. A., Dowsett, C. J., Gennetian, L. A., & Huston, A. C. (2010). A tale of two methods: Comparing regression and instrumental variables estimates of the effects of preschool child care type on the subsequent externalizing behavior of children in low-income families. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1030–1048.

- DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C. (2010). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009 (Current Population Reports No. P60-238). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

- Duncan, G. J., Huston, A. C., & Weisner, T. S. (2007). Higher ground: New Hope for the working poor and their children. New York: Russell Sage.

- Duncan, G. J., Ziol-Guest, K. M., & Kalil, A. (2010). Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health. Child Development, 81, 306–325.

- European Economic Community. (1985). 85/8/EEC: Council decision of 19 December 1984 on specific Community action to combat poverty. Official Journal, L002, 24–25. Retrieved from <http://tinyurl.com/4dw6p4k>.

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2010). America’s children in brief: Key national indicators of well-being, 2010. Washington, DC: Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics.

- Fuller, B., Kagan, S. L., Caspary, G., & Gauthier, C. A. (2002). Welfare reform and child care options for low-income families. Future of Children, 12(1), 97–119.

- Gennetian, L. A., Duncan, G., Knox, V., Vargas, W. G., & Clark-Kauffman, E. (2004). How welfare and work policies for parents affect adolescents: A synthesis of research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14, 399–423.

- Greenberg, M. T., Levin-Epstein, J., Hutson, R. Q., Ooms, T. J., Schumacher, R., Turetsky, V., et al. (2002). The 1996 welfare law: Key elements and reauthorization issues affecting children. Future of Children, 12(1), 27–57.

- Gueron, J. M., & Pauly, E. (1991). From welfare to work. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Halle, T., Forry, N., Hair, E., Perper, K., Wandner, L., Wessel, J., et al. (2009). Disparities in early learning and development: Lessons from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort (ECLS-B). Washington, DC: Child Trends.

- Haskins, R., Primus, W., & Sawhill, I. (2002). Welfare reform and poverty. In R. Haskins, & I. Sawhill (Eds.), Welfare reform and beyond (pp. 59–70). Washington, DC: Brookings.

- Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312, 1900–1902.

- Huston, A. C., & Bentley, A. C. (2010). Human development in societal context. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(7), 7.1–7.27.

- Huston, A. C., Duncan, G. J., Crosby, D. A., Ripke, M. R., Weisner, T. S., & Eldred, C. A. (2005). Impacts on children of a policy to promote employment and reduce poverty for low-income parents: New Hope after five years. Developmental Psychology, 41, 902–918.

- Huston, A. C., Duncan, G. J., Granger, R., Bos, J., McLoyd, V. C., Mistry, R., et al. (2001). Work-based anti-poverty programs for parents can enhance the school performance and social behavior of children. Child Development, 72, 318–336.

- Kahn, A. J., & Kamerman, S. B. (2002). Social exclusion: A better way to think about childhood deprivation? In A. J. Kahn, & S. B. Kamerman (Eds.), Beyond child poverty: The social exclusion of children (pp. 11–36). New York: Institute for Child and Family Policy at Columbia University.

- Karoly, L. A., Kilburn, M. R., & Cannon, J. S. (2005). Early childhood interventions: Proven results, future promise. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

- Knijn, T., Martin, C., & Millar, J. (2007). Activation as a common framework for social policies towards lone parents. Social Policy & Administration, 41, 638–652.

- Love, J. M., Kisker, E. E., Ross, C., Raikes, H., Constantine, J., Boller, K., et al. (2005). The effectiveness of early head start for 3-year-old children and their parents: Lessons for policy and programs. Developmental Psychology, 41(6), 885–901.

- Mayer, S., & Jencks, C. (1989). Poverty and the distribution of material hardship. Journal of Human Resources, 24(1), 88–114.

- McLoyd, V. C., Aikens, N. L., & Burton, L. M. (2006). Childhood poverty, policy, and practice. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Series Eds.), A. Renniger & I. Sigel (Volume Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Child psychology in practice (6th ed., pp. 700–775). New York: Wiley.

- Melhuish, E., Belsky, J., Leyland, A. H., & Barnes, J. (2008). Effects of fully-established Sure Start Local Programmes on 3-year-old children and their families living in England: A quasi-experimental observational study. The Lancet, 372(9650), 1641–1647.

- Miller, C., Huston, A. C., Duncan, G. J., McLoyd, V. C., & Weisner, T. S. (2008). New Hope for the working poor: Effects after eight years for families and children. New York: MDRC.

- Mistry, R. S., Lowe, E. D., Benner, A. D., & Chien, N. (2008). Expanding the family economic stress model: Insights from a mixed-methods approach. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 196–209.

- Morris, P. (2008). Welfare program implementation and parents’ depression. Social Services Review, 82, 579–614.

- Morris, P. A., Duncan, G. J., & Clark-Kauffman, E. (2005). Child well-being in an era of welfare reform: The sensitivity of transition in development to policy change. Developmental Psychology, 41, 919–932.

- Morris, P. A., Gennetian, L. A., Duncan, G. J., & Huston, A. C. (2009). How welfare policies affect child and adolescent school performance: Investigating pathways of influence with experimental data. In J. Ziliak (Ed.), Welfare reform and its long-term consequences for America’s poor (pp. 255–289). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Olds, D. L., Sadler, L., & Kitzman, H. (2007). Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 355–391.

- Quadagno, J. (1994). The color of welfare: How racism undermined the war on poverty. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schiller, B. R. (2008). The economics of poverty and discrimination (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

- Shonkoff, J. P. (2010). Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Development, 81, 357–367.

- UNICEF. (2005). Child poverty in rich countries (Innocenti Report Card 6). Florence, Italy: Innocenti Research Centre.

- UNICEF. (2007). Child poverty in perspective: An overview of child well-being in rich countries (Innocenti Report Card 7). Florence, Italy: Innocenti Research Centre.

- Votruba-Drzal, E. (2006). Economic disparities in middle childhood development: Does income matter? Developmental Psychology, 42, 1154–1167.

- Waldfogel, J. (2010). Britain’s war on poverty. New York: Russell Sage.

- Walker, J. T., Huston, A. C., & Imes, A. E. (2010). Developmental differences in the effects of welfare and employment policies on children’s social behavior: Is family stress a pathway? Unpublished manuscript, University of Texas at Austin.

- Yoshikawa, H., Weisner, T. S., & Lowe, E. D. (Eds.). (2006). Making it work: Low-wage employment, family life, and child development. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Huston, A. C. (2011). Children in poverty: Can public policy alleviate the consequences? Family Matters, 87, 13-26.