Think Family

A new approach to families at risk

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

April 2011

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

This paper outlines a new framework 'Think Family', which includes a coordinated support system, a focus on the needs of all family members, building on family strengths, and the provision of tailored support. In her brief account of a short history of public service reforms in Britain, she stresses that a minority tend to miss out, despite the fact that each reform has benefited many people's lives. More importantly, the minority who have missed out have had difficulties that are increasingly complex and experienced on multiple fronts. She suggests that disadvantages tend to ?clump together? and interact with each other, and thus often lead to poor outcomes for children. While society has become more prosperous, the gap between the top and bottom of the social gradient has widened. Without policy intervention, disadvantaged families would fall further behind; thus, Eisenstadt argues that social policies need ?a more nuanced approach? and maintains that good policy practices tend to focus on a particular group and have a lead professional working with each family. This means that such professionals must have a small case load to enable them to concentrate on and build a strong and continuing relationship with just a few families. While developing such practices may entail higher costs, not doing so will result in even higher social cost through poor outcomes for children across generations. In promoting the Think Family approach, Eisenstadt stresses the importance of cooperation and information sharing between services, which is critical in the climate of reduced public spending.

The United Kingdom’s Families at Risk Review was commissioned in 2007 by then Prime Minister Tony Blair. Having set up the Social Exclusion Unit early on in Labour’s first term, the Prime Minister was disappointed that many of the deep-seated and complex problems facing the most disadvantaged families had not yet been tackled. While much progress had been made, there was still much to do. The review was established to find out:

- Who are the most excluded families?

- How many are there?

- What are their problems?

- What can be done about them?

The context for the work can be seen as part of a very long history of social progress. A series of social reforms in Britain from the 19th century onwards had a huge impact on the quality of life for the many. However, with each wave of reforms, the difficulties of those few not helped became more and more complex and intractable. Clean water in the 19th century dramatically improved the health of the nation. In the 20th century, free state education and the establishment of the National Health Service were again universal services that initially not only shifted the curve, making life better for the vast majority of the population, but also narrowed the gap between the top and bottom, thus reducing inequality and reducing abject poverty. It could be argued that the major reform of the 21st century in Britain has been the child care revolution. Universal preschool education has been made available for all, and flexible co-funding arrangements for child care for working parents have transformed the employment prospects for women, and significantly reduced child poverty in Britain.

All these reforms have been successful for the many, but a minority have still missed out, and the gap between that minority and the rest has significantly widened, particularly in the last thirty years, when incomes at the very top have risen very steeply. Hence, things have gotten better for the many, significantly better for the few at the very top, and significantly worse for the few at the very bottom. Most people in Britain are healthier, wealthier and probably wiser than thirty years ago. There have been significant improvements for the many as the wealth of the nation has increased, public services have improved, and public health campaigns, particularly on smoking, have had real impact. However, no public policy works for all. The numbers for whom these changes have failed to work are relatively small, but the persistence and complexity of their problems is costly to themselves and to the state. They cost the state through increased spending on special education, social welfare benefits, health services and the criminal justice system. They cost families themselves through high levels of stress and poor outcomes for children across generations.

The lesson is not that public policy has failed, but that it has succeeded for the many and failed for the few. This means a more nuanced approach is needed in the debate about universal or targeted services. The private sector response to the dilemma of who is not buying a particular product is market segmentation—consumer research informs private companies as to who is more or less likely to buy a product. We need a similar approach to the complex issues of deep disadvantage. We need to understand why policies don’t work for particular groups, and then to consult with those groups and individuals to figure out what would work.

The nature of the problem

Public health data consistently tells us two key facts:

- Inequalities interact with each other. Poor mental or physical health in early childhood leads to poor educational outcomes; poor educational outcomes reduce the chances of gainful employment for adults; and workless adults are more likely to be unwell, both physically and emotionally.

- For virtually all disadvantages there is a clear gradient across social classes. This means that while families in the lowest quintile are likely to have the most severe problems, families in the other quintiles also have problems. By concentrating only on the poorest, much need is left unmet. But the highly complex and multiply disadvantaged families tend also to be among the poorest.

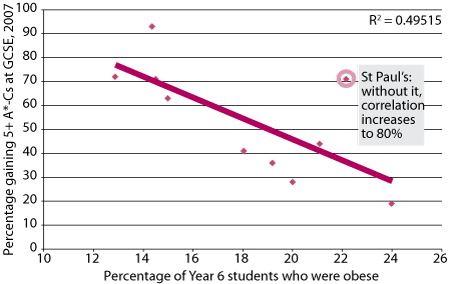

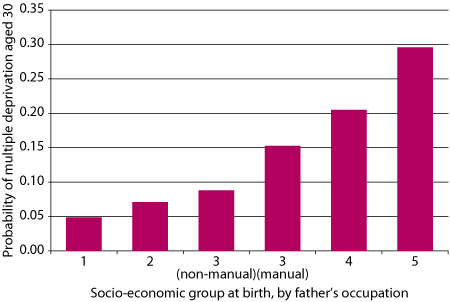

The two diagrams in Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the point. Figure 1 shows the relationship between poor educational attainment and obesity in a local authority in southeast England. It shows a clear correlation between higher results at tests for sixteen-year-olds and lower obesity rates in secondary schools. Interestingly, the outlying school, St Paul’s, has a catchment from throughout the authority, so a much more mixed intake, hence both good exam results and high obesity rates. Figure 2 shows the likelihood of multiple deprivation in adulthood based on social class at birth. While nearly one in three of adults born into the bottom quintile will be deprived in adulthood, one in twenty adults born into the top quintile will also be deprived at age thirty.

Figure 1 Relationship between poor educational attainment and obesity, southeast England, 2007

Note: The General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) is an academic qualification undertaken by students aged 14–16 in secondary education in Great Britain. Students at age 16 must achieve five or more A*-C GCSE grades in order to be considered to have passed for the purposes of employment or advancement to exams for university entrance.

Source: Reproduced from Milton Keynes Primary Care Trust, 2007

Figure 2 The likelihood of multiple deprivation of adults at 30 years, by socio-economic group at birth, England, 1970 cohort study, 2007

Note: Socio-economic group (SEG) 1: professional; SEG 2: Managerial/technical; SEG 3 (non-manual): skilled non-manual; SEG 3 (manual): skilled manual; SEG 4: partly skilled; SEG 5: unskilled.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Feinstein, Hearn, Renton, Abrahams, & MacLeod (2007), p. 12.

Risks to children come from their parents

Most of the factors that are risky for children are concerned with the state of their parents. Long-term worklessness, poor housing, poor maternal mental health, or having a parent in prison are all key factors in determining poor outcomes for children. In Britain, we have made major reforms of children’s services but have had a much more difficult challenge in ensuring that adult services understand the needs of parents. Adult psychiatric services rarely take account of the needs of children in determining treatments for their patients who coincidentally happen to be mothers or fathers. Boys with a father in prison have a very high risk of winding up in the criminal justice system. Overcrowded housing makes it harder to find a quiet place to do homework, or even have friends to visit after school. It is self-evident that the key problems that affect children are not problems that can be solved by working solely with children. We need a more systematic approach that recognises the complexity and interrelated nature of family problems.

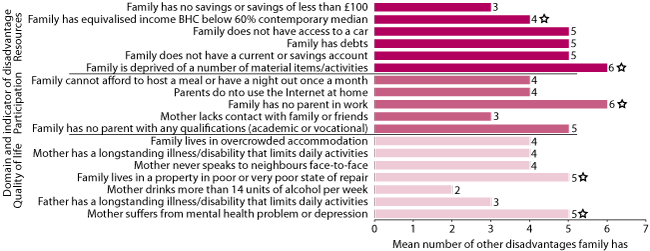

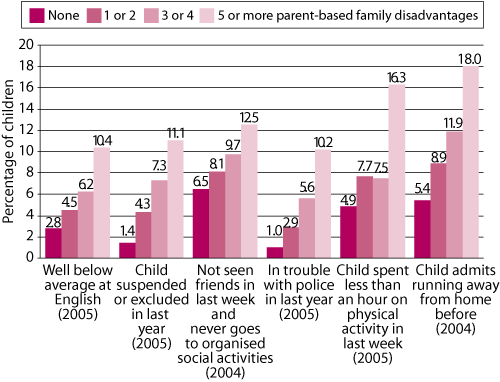

Moreover, particular risks seem to clump together. The starred bars in the graph in Figure 3 show how particular disadvantages tend to occur together, like poor housing, worklessness and mental health problems. These then have a particularly harsh impact on children living in families with these sets of disadvantages. In Britain, we know that a relatively small number of families have a large number of these problems. Indeed, just over half of Britain’s families have one or no serious disadvantages, while 2% have ten or more. But the impact on children living in these families is a highly elevated risk of having poor outcomes. Figure 4 (on page 40) illustrates the risks to children associated with the number of problems faced by parents in the family.

Figure 3 Grouping of disadvantages among families, UK, 2009

Note: The starred bars indicate how particular disadvantages tend to occur together.

Source: Reproduced from Oroyemi, Damioli, Barnes, & Crosier (2009), p. 16.

Figure 4 Child outcomes by number of parent-based family disadvantages, UK, 2004–05

Source: Families and Children Survey (2004 and 2005; 8 disadvantages measured for this study). Reproduced from Social Exclusion Task Force (2008)

What can government do?

The UK government has developed a wide range of policies to support families. They fall under three broad strategies.

First, a range of policies are designed to reduce pressure on families. These tend to be anti-poverty measures like financial support through tax credits, flexible child care and targeted benefits. Also included in this category are improved maternity and paternity leave arrangements and rights and legal protection for parents.

Second, the government has played a role in enhancing the capabilities of parents. These tend to be more service-oriented activities such as parenting programs, information and guidance, and mainstream universal services like health visiting.

The third and most difficult is the role that government plays in safeguarding children from harm. This responsibility is sometimes in tension with the second strategy of support and enhancing capabilities. Government always struggles with judgements as to whether in extreme circumstances children are better off without their parents; that is, in substitute care provided by the state. In Britain, as in other countries, the record of the state as a substitute parent has been poor. Children in the care system generally do not do as well as their peers; however, it is always difficult to know to what extent this is a result of negative life experiences before the decision to put children into care, or a result of failures of the care system itself. In my view, it is often a combination of the two. Great efforts have been made in Britain in the last ten years to improve the care system, some of which have met with success. While much of the attention has been on safeguarding children from non-accidental harm, other safeguards include accidental harm, such as baby seats in cars, the provision through children’s centres of home safety equipment and, in many areas, the fire service has been providing and installing free smoke alarms. Indeed, injuries and deaths of children due to accidental events have a similar social gradient to other poverty-related disadvantages. Children in poor housing are considerably more likely to die from fires or road traffic accidents than their peers in better quality accommodation.

Despite what may look like a coherent set of strategies above, The government in the UK has a somewhat confused attitude towards parents. For issues like school choice, the government sees parents as consumers of a public service over which they should have choice. When it comes to issues of child neglect or abuse, parents are clients, and often government agencies treat parents as pupils who need to learn how best to be a parent through courses and parenting programs. Moreover, there is a difficulty in the use of the term “parents”, when usually the mindset is “mothers”. Men are sometimes seen as “benefits cheats” or “deadbeat dads” unwilling to support their children. In other circumstances, where fathers are absent, men are seen as substitute role models. This last vision of male role model somehow implies that children with an absent father need a male role model—a reasonable substitute for the person with whom they may have had a warm relationship with before the breakdown in the relationship with their mother. Moreover, many lone mothers will be in contact with their own fathers, brothers or male friends. It is hard to imagine anyone suggesting that a child without a mother needs a female role model.

Think Family

In considering issues of complex disadvantage, the UK Cabinet Office Social Exclusion Task Force came up with the Think Family framework to meet the needs of children in families whose members have complex and entrenched problems. The framework includes four key features:

- no wrong door—contact with any service offers an open door into a system of joined-up support;

- look at the whole family—services must assess the needs of all members of the family, working with both adult and children’s services;

- build on family strengths—successful programs always work on the basis that the family has some skill base or inherent strengths on which jointly developed plan of action can be built; and

- provide tailored support to need—families with complex problems need support that is specially designed around a number of needs across different members of the family.

Programmes like Family Intervention Projects and Nurse Family Partnerships are good examples of interventions that contain all the above features. They also tend to be highly targeted: Nurse Family Partnerships at first-time teen mothers, and Family Intervention Projects at particularly disruptive families who cause such distress within neighbourhoods that they are often threatened with eviction. Both interventions include another important characteristic: they rely on a lead professional having a particularly strong and persistent relationship with the family. Such lead professionals have small case loads and work intensively with families. Plans are agreed with the families and milestones carefully tracked to ensure progress. Typical of such plans is agreement on what behaviour changes are expected from each family member and what additional support the lead professional can deliver, including often quite practical support: transport, improved housing conditions, or free access to laundry facilities. It is often the highly practical support that delivers engagement with often intransigent and historically non-compliant service users. Delivery of such practical help builds trust and engenders a feeling of being heard, which is often missing in the relationship between very disadvantaged families and the service providers meant to work with them.

Challenges to the implementation of Think Family

Critical to the Think Family approach is the ability of the lead professional to ensure relevant local agencies will deliver on additional services. The lead professional cannot personally deliver every service needed, and so must have the authority to get such families ahead in the queue for drug and alcohol services, adult mental health services, housing and the range of other services that may be needed. Very often in families with a range of complex problems, an individual may fall just beneath the entry threshold for a service; for example, they might not quite be depressed enough. The impact on families of high thresholds, particularly in adult services, can be severe and needs to be addressed for Think Family to work. This means adult services, particularly mental health services, must take into account that a patient or client is also a mother or father. This requires changes in service protocols as well as service cultures.

Workforce issues are also key. Taking a whole-family approach requires different professionals to understand and respect each others’ roles, and be willing to share expertise and data. Most families would prefer to deal with fewer professionals; that is, one person who can do three or four things, rather than three or four individuals with whom there are separate records, multiple appointments and multiple journeys. Complex lines of accountability across agencies and different professions make service integration at the front line extremely difficult. It requires considerable cooperation, and some managed risk-taking.

Furthermore, there are sometimes genuine tensions about what is best for different members of a family. An anti-poverty strategy would recommend full-time work for mothers of children at any age; and yet evidence suggests that group care for babies under one carries some risks. Men who have served time in prison are less likely to re-offend if they maintain contact with their family. Is family contact always the best thing for the children of offenders if it means the family stays within a criminal community?

A strong feature of family policy generally, and Think Family interventions specifically, has been an emphasis on measurable outcomes. Measurement poses another significant challenge. While small-scale interventions usually build in measurement, expanding such programs to larger scales poses real problems in data collection. It can become very bureaucratic and burdensome, for professionals and families alike. Moreover, many outcomes are not evident for some years post-intervention. When can we know if it did or did not work, and for whom?

Finally, the three issues most often evident in deep disadvantage are poor housing, long-term worklessness and poor maternal mental health. All of these issues are very expensive to deal with. One might argue that they would be even more expensive if left alone, but costs in the here and now are always more pressing than the hopes of future cost savings. Unlike the last ten years, in Britain we are now in times of significant fiscal constraint. When money is tight there is much more to be gained by collaboration and reducing duplication, but also much more resistance to shared budgets. We are facing very tough times ahead, and holding on to the gains both in practice and in thinking from the last ten years is going to be very tough. But there are also some hopeful signs, and much to play for.

References and further reading

- Milton Keynes Primary Care Trust. (2007). Public health annual report 2007. Eaglestone, Milton Keynes: Milton Keynes Primary Care Trust and Milton Keynes Council. Retrieved from <www.miltonkeynes.nhs.uk/default.asp?ContentID=1529>.

- Feinstein, L., Hearn, B., Renton, Z., Abrahams, C., & MacLeod, M. (2007). Reducing inequalities: Realising the talents of all. London: National Children’s Bureau.

- Oroyemi, P., Damioli, G., Barnes, M., & Crosier, T. (2009). Understanding the risks of social exclusion across the life course: Families with children. A research report for the Social Exclusion Task Force, Cabinet Office. London: Social Exclusion Task Force, Cabinet Office.

- Social Exclusion Task Force. (2006). Reaching out: An action plan on social exclusion. London: Social Exclusion Task Force, Cabinet Office.

- Social Exclusion Task Force. (2007). Reaching out: Think Family, analysis and themes from the Families at Risk Review. London: Social Exclusion Task Force, Cabinet Office.

- Social Exclusion Task Force. (2008). Think Family: Improving the life chances of families at risk. London: Social Exclusion Task Force, Cabinet Office.

Eisenstadt, N. (2011). Think Family: A new approach to Families at Risk. Family Matters, 87, 37-42.