Unfit mothers ... unjust practices?

Key issues from Australian research on the impact of past adoption practices

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

April 2011

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Although reliable figures are not available, in the decades prior to the mid-1970s, it was common in Australia for babies of unwed mothers to be adopted. There is a wealth of material on adoption in Australia—including individual historical records, analyses of historical practices, case studies, expert opinions, personal testimony provided to two parliamentary inquiries—but limited empirical research on the issue of past adoption practices and its impact on those involved.

Although reliable figures are not available, in the decades prior to the mid-1970s, it was common in Australia for babies of unwed mothers to be adopted. There is a wealth of material on adoption in Australia—including individual historical records, analyses of historical practices, case studies, expert opinions, personal testimony provided to two parliamentary inquiries—but limited empirical research on the issue of past adoption practices and its impact on those involved.

Over the past century, adoption practices in Australia—and society’s responses to unwed pregnancies and single motherhood—have undergone considerable changes. Until a range of social, legal and economic changes in the 1970s, it was common for babies of unwed mothers to be adopted.1 The adoption practices at the time had the potential for lifelong consequences for the lives of these women and their children, as well as others, such as their families, the father, the adoptive parents and their families. Commentators, professional experts, researchers and parliamentary committees have all accepted that past adoption practices were far from ideal, had the potential to do damage, and often did (see Box 1).

Many authors talk about the “adoptive triangle”: (a) the adopted child; (b) the birth, or “relinquishing”, mother; and (c) the adoptive parents. Each of these “parties” to the events may bring a different perspective. The primary focus of this review is to look at research literature on the adoption of the babies of unwed mothers, and the impact on these mothers of the surrounding experiences. There is a much wider body of research looking at both the experience of adopted children, and the experiences and needs of adoptive parents; however, it is beyond the scope of this brief review to give detailed consideration to these perspectives.

There is limited research available in Australia on the issue of past adoption practices.2 Finding relevant literature to review in this field is problematic, as it is difficult to identify research that examines the issues of consent and the contested nature of what “voluntary” relinquishment would look like, given the social attitudes, historical social work/child welfare practices and financial pressures at the time (such as views about single mothers, ex-nuptial children, and illegitimacy). A search of the literature on adoptions that addresses historical perspectives provides the closest alignment to this issue. There appears to be a dearth of literature published in peer review outlets, so the issue of critiquing the validity of the claims is an important one—separating out anecdotes, case studies, historical critiques and solid empirical data on the impact of past practices.3

A new national research study on the service response to past adoption practices

On 4 June 2010, the Community and Disability Services Ministers’ Conference (CDSMC) announced that Ministers had agreed to a joint national research study into past adoption practices, to be conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS). The focus of this study will be on understanding current needs and information to support improved service responses. It is anticipated that this will be the largest study on the impact of past adoption practices ever conducted in this country. The aim of the research study is to utilise and build on existing research and evidence about the extent and impact of past adoption practices to strengthen the evidence available to governments to address the current needs of individuals affected by past adoption practices.

Information will be collected using an online survey, hard-copy surveys and in-depth interviews, integrating results from across the different elements of the study.

The study will commence in mid-2011, to be completed by mid-2012.

This study will complement the work of the History of Adoption Project at Monash University, which is focused on “explaining the historical factors driving the changing place, meaning and significance of adoption”, particularly through its collection of oral histories. See: <arts.monash.edu.au/historyofadoption>.

Box 1: Past adoption practices

Until the early 1970s in Australia, unwed (single) women who were pregnant were encouraged—or forced—to “relinquish” their babies for adoption. The shame and silence that surrounded pregnancy out of wedlock meant that these women were seen as “unfit” mothers. The practice of “closed adoption” was seen as the solution—where the birth identities of adopted children were effectively erased to allow the children’s identification with their new adopted family. Mothers were not informed about the adoptive families, and the very fact of their adoption was usually kept secret from the children (see Swain & Howe, 1995).

Terms used to describe past adoption practices

A range of different terms is used in the literature to refer to both adoption practices and the women affected by them. Some of the terms are perceived as “value-laden”, either because of their acceptance of a particular point of view (e.g., “stolen” implies illegal practices), or because their attempt at neutrality (e.g., “relinquishing mothers”) potentially hides what are alleged as immoral or illegal practices. These terms include:

- relinquishing mothers;

- parents who relinquished a child to adoption;

- birth mothers;

- natural mothers;

- genetic parents;

- adoption of ex-nuptial children;

- mothers affected by past adoption practices;

- mothers of the “stolen white generation” (analogous to the Stolen Generations of Aboriginal children removed from their parents, which occurred at roughly the same time period);

- real parents;

- losing a child to adoption;

- reunited mother of child/ren lost to adoption;

- separation from babies by adoption; and

- “rapid adoption”—the practice of telling a single mother her baby was stillborn, and the baby then being adopted by a married couple.

Source: Higgins (2010)

History of adoption laws and policies

In-depth analysis of past laws and institutional policies in Australia, and the changes that have occurred over time have been addressed in detail in a couple of major books, particularly Swain and Howe (1995) and Marshall and McDonald (2001). Some of the key events, as described by these authors, are outlined in Box 2 (on page 58). Since these legislative changes, adoption practices have reflected this shift away from secrecy to open adoptions. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), which publishes national statistical information on adoptions in Australia, noted that in 2007–08:

Agreements made at the time of adoption indicate that the majority of local adoptions are now “open” (77%)—only 23% of birth parents requested “no contact or information exchange”. (AIHW, 2009, p. 20)

Box 2: Legal and policy milestones regarding adoption and single mothers in Australia

- Legislation on adoption commenced in Western Australia in 1896, with similar legislation in other jurisdictions following.

- Before the introduction of state legislation on adoption, “baby farming”* and infanticide was not uncommon.

- Legislative changes emerged from the 1960s that enshrined the concept of adoption secrecy and the ideal of having a “clean break” from the birth mother.

- The Council of the Single Mother and her Children (CSMC) was set up in 1969, which set out to challenge the stigma of adoption and to support single and relinquishing mothers.

- The Commonwealth Government introduced the Supporting Mother’s Benefit in 1973, coinciding with a rapid decline in adoptions from the peak of 1971–72.

- The status of “illegitimacy” disappeared in the early 1970s, starting with a Status of Children Act in both Victoria and Tasmania in 1974 (in which the status was changed to “ex-nuptial”).

- Abortion became allowable in most states from the early 1970s (the 1969 Menhennitt judgement in Victoria and 1971 Levine judgement in NSW).

- Further legislative reforms started to overturn the blanket of secrecy surrounding adoption (up until changes in the 1980s, information on birth parents was not made available to adopted children/adults).

- Beginning with NSW (in 1976), registers were established for those wishing to make contact (both for parents and adopted children).

- In 1984, Victoria implemented legislation granting adopted persons over 18 the right to access their birth certificate (subject to mandatory counselling). Similar changes followed in other states (e.g., NSW introduced the Adoption Information Act in 1990).

- By the early 1990s, legislative changes in most states ensured that consent for adoption had to come from both birth mothers and fathers.

* “Baby farming” refers to the provision of private board and lodging for babies or young children at commercial rates, a practice that was often abused for financial gain, including cases of serious neglect and infanticide (see Marshall & McDonald, 2001, p. 21).

Prevalence estimates

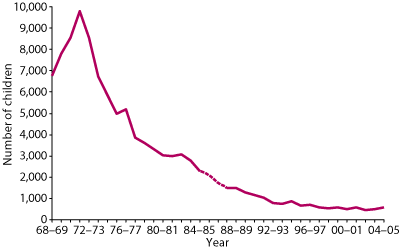

With national statistics only compiled from 1969–70 onwards, it is not possible to reliably calculate the total (cumulative) number of past adoptions across Australia. Since 1969, rates of adoption of Australian-born children by non-related persons (i.e., excluding overseas adoptions, and adoption by step-parents, etc.) were highest in the early 1970s (with the highest being 9,798 for 1971–72). From then, there was a rapid decline through to the early 1990s, since when it has remained relatively stable at around 400 to 600 children per year—around 5% of the annual number of adoptions in the early 1970s (see Figure 1). There are a number of reasons for the considerable decline in adoptions to the current levels, despite the fact that a larger proportion of children are now born outside registered marriages. These include:

- an overall decline in fertility rates;

- greater availability and acceptance of birth control methods;

- the establishment of family planning centres;

- greater social acceptance of single parenthood and of children raised in de facto relationships; and

- the availability of welfare payments and social supports for single parents (AIHW, 2009).

Figure 1 Number of children legally adopted in Australia, 1968–69 to 2004–05

Note: National data were not collected between 1985–86 and 1986–87.

Source: AIHW, 2005

Understanding the true extent of past practices, or its ongoing effects, is problematic. Winkler and van Keppel (1984) estimated that there were 35,000 non-relative adoptions during the 12 years from July 1968 to June 1980. In terms of lifetime prevalence—considering both past and more recent rates of adoptions—Winkler, Brown, van Keppel, and Blanchard (1988) estimated that “one in 50 women in Western countries in 1988 have placed a child for adoption (traditional, closed adoption) since the beginning of the twentieth century” (p. 48). Although not based on verifiable data, it highlights the issue that, as they accumulate over a number of decades, the number of adoptions in total is likely to be significant. Winkler et al. also estimated that 1 in 15 people are affected by adoption (including birth parents, adoptive parents and the adoptee). Inglis (1984) claimed that, in Australia, more than 250,000 women have relinquished a baby for adoption since the late 1920s. Although she did not describe the basis for this calculation, it is one that has since been widely cited. In sum, there are no accurate data on the number of Australians who have been affected.

There is a wide range of people who may be affected by past adoption practices, including:

- mothers;

- the adopted children;

- fathers (anecdotal evidence from case studies suggests that often mothers knew who the fathers were, including boyfriends and even husbands);

- the mother’s family (who may have failed to provide support or actively demanded relinquishment, silence and censure);

- subsequent partners of the mothers;

- siblings; and

- the adoptive family.

The range of people involved suggests therefore the potential for wide-ranging impacts, including the possibility of the effects of past adoption practices on these individuals in turn “rippling” through to others, including other children and family members.

There are also a number of organisational contributors, including:

- management/leaders of the organisations involved with adoption at the time (hospital administrators, leaders of churches or religious orders);4

- individuals within these health, charitable and religious organisations (social workers, nurses, doctors, nuns); and

- doctors treating infertile couples, who created demand for babies to be given up for adoption.

Societal factors

From the 1940s, it was seen as desirable for unwed mothers to relinquish their children as early as possible—straight after birth. Women’s magazines became fierce advocates for adoption. Waiting lists of prospective adoptive parents began to emerge in 1940s and 1950s. As demand outstripped supply, the pressure to relinquish was particularly high in maternity homes where matrons and social workers were often personally acquainted with the prospective adoptive parents (see Marshall & McDonald, 2001; Swain & Howe, 1995).

Some of the key social factors that have played a role in developing and maintaining adoption practices included:

- the enactment of child welfare legislation, development and administration of policies, the operation of statutory welfare departments, and the funding/regulation of other non-government organisations to operate adoption services in each state/territory;

- the absence or inadequacy of political and social structures available to support single mothers;

- psychological and social work theories that were used by proponents to support various aspects of the adoption practices, including support for the idea that an adopted child should have a “clean break” from the “relinquishing” mother; and

- broader societal attitudes in areas such as the role of women, sex and illegitimacy, poverty and the capacity of single women to effectively parent and raise good citizens, the silence that descended on pregnancy outside of marriage, and the “closed” nature of adoption prior to the 1970s.

Solving three social problems: Illegitimacy, infertility and impoverishment

Common themes relating to the dominant social views, and the consequent treatment of single pregnant women include:

- shame;

- silence;

- blame (fear of passing on delinquency through bad parenting; seeing pregnancy as being the effect of “sin”); and

- discriminatory behaviour (compared to the treatment of married mothers in hospitals).

According to Harkness (1991), both the adoptive mother and the “relinquishing” mother can be seen as products—or victims—of “a punitive and patronizing society anxious to graft newborn babies on to ‘good’ (married) mothers as quickly as possible” (p. 2). Consequently, in the period up to the early 1970s, many saw adoption as being explicitly (or implicitly) the solution to the intertwined problems of: illegitimate babies, the risk of impoverishment (and consequent neglect) for single mothers, and the needs of infertile couples.

Without adequate support from families or social support services for single mothers, a pregnant single woman risked a life of poverty. Swain and Howe (1995) argued that the success of adoption was built upon the grim prophecies that depicted single women raising their children as being condemned to living in poverty and despair, leaving little hope for the child to have a successful and happy life (p. 151). They argued that by rendering a child legitimate, adoption aimed to eliminate the disadvantages of illegitimacy; however, it created another level of secrecy and deception, making the problems it sought to solve more complicated.

Society saw “adoption of ex nuptial children as a means of protecting children from their single mothers, who were often thought to be unfit parents, and also as a means of punishing their mothers” (Jones, 2000, p. 51). For example, Lawson (1960), an obstetrician, paid little or no heed to the possible impact of adoption on the mother. Advice to his medical colleagues to deal with the “big problem” of “single girls who become pregnant” instead promoted the presumed positive benefits for the child, with no mention of the mother:

The prospect of the unmarried girl or of her family adequately caring for a child and giving it a normal environment and upbringing is so small that I believe for practical purposes it can be ignored. I believe that in all such cases the obstetrician should urge that the child be adopted. In recommending that a particular child is fit for adoption, we tend to err on the side of overcautiousness. “When in doubt, don’t” is part of the wisdom of living; but over adoptions I would suggest that “when in doubt, do”, should be the rule. (p. 165)

S. Swain (1992) argued that “community hostility towards single mothers and fears about the ‘quality’ of their offspring resulted in secrecy becoming central to Australian adoption practice” (p. 2). Based on an analysis of historical documents from NSW, Jones (2000) argued:

It was thought that removal of illegitimate children, children at risk of neglect or moral contamination and children from hard-core problem families would give the family a second chance to heal itself just as single mothers would be able “to live happy and useful lives” after relinquishment, for in those days before grief counselling, mothers were expected to “get on with life” instead of confronting their grief and loss. (pp. 52–53)

Choice and coercion

Commentators acknowledge that there were limited choices for these women, and “coercive social forces” led many women to sign consents for adoption up until legislative reform in the 70s and 80s (Marshall & McDonald, 2001). A number of different contributors to the inquiry held by the NSW Legislative Council Standing Committee on Social Issues (2000) identified the lack of choice experienced by single pregnant women in the past, including the lack of availability of contraception and abortion, and the lack of awareness and respect for the rights of women (e.g., to see the child, to revoke the initial decision, or to choose between relinquishment or keeping the baby). One mother interviewed by Swain and Howe (1995) stated: “They said to me ‘the decision is yours’ … But it was mine without any help anywhere” (p. 145).

Across the various types of literature reviewed, a consistent theme was that the mothers whose babies were adopted reported less social support from their family than single mothers who kept their babies. There was a lack of pre-relinquishment information or post-relinquishment emotional support and advice about options. From an autobiographical perspective, Frame (1999) described the situation for his birth mother after she relinquished him:

Like many girls in a similar position, she was advised to forget about the child and continue with life as though nothing had happened. No mention was made of the trauma and grief associated with relinquishing a child. There was no offer of any continuing spiritual or psychological care. None existed. (p. 29)

It is important to also consider the role of the parents of the young unwed mothers affected by past adoption practices. For example, one of the women from Kate Inglis’ (1984) groundbreaking Australian compilation of personal testimonies, “Joy”, described her emotional reaction when she thinks back on the actions of her own mother: “The longer I’m a mother the more amazed I am about what she [my mother] did to me. I mean after what you go through with kids you’d fight for them, wouldn’t you?” (p. 31).

Secrecy and silence

Secrecy and silence began with the experience of teenage/single pregnancy, and continued through the experience of adoption and the future lives of the women subjected to these past practices. Swain and Howe (1995) provided data suggesting that between World War II and 1975, approximately 30–40% of women who became pregnant out of wedlock spent time in an institution to conceal their pregnancy (i.e., they became invisible). However, the invisibility did not stop with the birth and the adoption; the silence continued. According to accounts of the mothers, their experience of adoption was “a particular kind of hell we weren’t allowed to talk about” (Harkness, 1991, p. 4). Case studies provide evidence that women kept the secret, often not sharing the information with friends, partners or subsequent children until much later—if at all. Silence can be seen as part of the “punishment” for the single woman who became pregnant: “Her pregnancy hidden … she was compelled to collude in her own punishment by maintaining her silence” (Swain & Howe, 1995, p. 11).

Secrecy was the main priority in adoption legislation prior to the 1980s. Ley (1992) argued that “it was believed that by obliterating a child’s birth identity it was possible to create for an adopted child a new identity which would ensure the genealogical history of the adoptive parents was now that of the adopted child” (p. 101). However, this assumption underlying the legislation at the time—that the “relinquishing mother” wanted her identity to remain a secret to her child—is not necessarily correct (Winkler & van Keppel, 1984).

Silence resonates through the lives not only of the mothers, but also of their adopted children. As one adoptee stated:

I think one of the worst things about “closed adoption” is the silence—the social covering up of the visceral, emotional, psychological, genetic and historical connections to the original mother and the denial of loss for all. (Durey, 1998, p. 104)

In attempting to explain the ongoing detrimental effects of adoption that their study uncovered, Winkler and van Keppel (1984) argued that the silence that surrounded “relinquishment” significantly contributed to the harmful effects experienced by many of the women involved. The authors briefly reviewed the research on bereavement experiences for mothers whose child died during or shortly after childbirth. The key element associated with a positive adjustment for bereaved mothers was communication; yet for mothers who “relinquished” a baby to adoption, the secrecy and silence compounded the difficulties they experienced.

Reunion experiences

Since the changes in Australian legislation during the 1970s and 1980s that provided access to birth records, and the establishment of services to assist with making contact, significant numbers of adoptees and birth mothers have exchanged information or made contact. The protection of privacy that has been put in place allows for either the parent or the child to place a veto on being contacted by the other party.

Regarding the number of vetoes placed on contact between adoptive children and their birth parents, AIHW (2010) noted:

As in previous years, in 2008–09 the number of applications for information far exceeded the number of vetoes lodged against contact or the release of identifying information—3,607 compared with 52. (p. 32)

In choosing to attempt reunion, one of the main motivations for mothers is to know about their child’s welfare; however, this is tempered with concern about how such an approach would be received:

While wanting to know that their children are alive and well, [mothers] are often reluctant to intrude into their lives or worry about upsetting their relationships with the adoptive parents. (Harkness, 1991, p. 149)

Another common motivation is that birth mothers want their child to know that they belonged and were loved/wanted. In one of the testimonies presented by Harkness (1991), “Gayle” reflected on her daughter, and what she hoped the adoptive parents would do:

I thought of her often. Just wondering and hoping that she was happy. I also hoped when she got older that her parents would be kind about me. That they would tell her that I loved her. (p. 78)

Harkness (1991) referred to the following phases in reunion:

There’s the anticipation and excitement as the search nears conclusion, the euphoria of the first meeting, the honeymoon period, the “let-down”, transition, and finally, resolution. (p. 204)

In the absence of other information, many adoptees assume that they were unloved and unwanted. Reunion, or some form of information exchange or contact, can help with communicating the mothers’ circumstances and the reasons surrounding the adoption, including feelings such as having no option, being coerced or feeling vulnerable. Reunion can bring relief or a sense of connection; however, the experience is not always positive. Feelings associated with reunion can include renewed guilt for the past “relinquishment” and fear of rejection by the child, and if the outcome is not positive, contact may cease (e.g., see Farrar, 2000).

There is a limited body of research on reunion experiences, and the evidence appears mixed as to the degree to which this process is uniformly beneficial for all those involved (NSW Legislative Council Standing Committee on Social Issues, 2000).

Traumatising aspects of past practices

Gaps in research relating to ongoing trauma

It has also been noted that there are “gaps” in the traditional research literature where particular issues of relevance for affected mothers are not considered, many of which relate to the issue of consent and coercion, and the theme of ongoing trauma (Higgins, 2010). These issues include:

- administration of high levels of drugs to the mother in the perinatal period (including pain relief medication, sedatives and a hormone that suppresses lactation) that were believed to affect their capacity to consent;

- not allowing the mother to see the baby (active shielding with a sheet or other physical barrier during birth, or removing the baby from the ward immediately after birth);

- withholding information about the baby (e.g., gender, health information, or even whether the baby was a live birth);

- discouraging the mother from naming the baby;

- bullying behaviour by consent takers (seen as the “bastions of morality” who are protecting “good families”);

- failure to advise the mother of her right to rescind the decision to relinquish;

- failure to adequately obtain consent from the mother (being too young to be able to give consent; interactions with other issues raised above that impaired the mother’s ability to give fully informed consent; consent given while under the influence of drugs; not being fully informed of rights, etc.);

- treating the mothers differently from married women;5

- abandonment by their own mothers/families;

- the closed nature of past adoption practices (secrecy, and the “clean break” theory; see Iwanek, 1997);

- assumption of a married couple’s entitlement to a child (adoption was a mechanism for dealing with infertility; see Harper, 1992), with the joint “problem” of illegitimacy and infertility (see Frame, 1999); and

- experimentation on newborn babies with drugs, with children dying or being adopted without any follow-up of these experiments (see Parliament of Australia Senate Community Affairs Committee, 2004).

These kinds of traumatising experiences were recounted by a number of women in submissions to two different state parliamentary inquiries (NSW Legislative Council Standing Committee on Social Issues, 2000; Parliament of Tasmania Joint Select Committee, 1999). According to the final reports from both of these inquiries, the evidence was seen as equivocal. It would take some significant historical research using archival material to determine the extent to which these practices were widespread and different to the treatment of single mothers who kept their babies or of married mothers.

One issue of particular importance is the trauma of the separation of mother and child. Mothers—particularly those who have not had any contact—continue to be traumatised by the thought that their child grew up thinking that they were not wanted. In the words of one mother: “It wasn’t the children who were not wanted. Mothers weren’t wanted because they were unmarried” (cited in Higgins, 2010, p. 13).

The grief and trauma is seen as “unresolved”, due to the silence surrounding “closed” adoption that prevented the mother from being able to mourn her loss (Goodwach, 2001; Rickarby, 1998). For mothers, the ongoing silence means knowing that her child is out there, wondering how they are, and knowing that there is a possibility of reunion—not the “severed bond” as promised by the clean break theory that shrouded the event in silence (Iwanek, 1997). In describing the grief and trauma, many authors have drawn on related bodies of research, using recent infant–mother attachment research to support their contention that separation causes emotional damage to both mother and child (e.g., Cole, 2009). It is somewhat ironic that earlier research in this same field (e.g., Bowlby, 1969) was used to justify the practices of the time (i.e., not allowing the child to bond with the birth mother so as to provide a “clean break” that encourages bonding with the new adoptive parents).

Time (does not) heal all wounds

Contrary to the popular myth that “time heals all wounds”, one theme that was fairly consistent across the different studies and methodologies reviewed here was the notion that the pain and distress of mothers’ experiences of adoption did not just “go away” with the passage of time. In his qualitative study of women recruited through a support group for relinquishing mothers, Condon (1986) found that “the majority of these women reported no diminution of their sadness, anger and guilt over the considerable number of years which had elapsed since their relinquishment” (p. 118). However, the healing effect of time is exactly what practitioners expected during that period.

Reinforcing the notion that the feelings do not just “go away”, on the basis of his data from adoption information service users, P. Swain (1992) claimed that most birth mothers “go on wondering and worrying about their child for the rest of their lives. For almost all, the contact with their child brings immense relief” (p. 32).

In a recent qualitative study with a limited, non-representative sample, Gair (2008) observed the feelings of powerlessness, low self-worth, depression and suicidal feelings/behaviours in people affected by past adoption practices in Australia, including adoptees, birth mothers, a birth father and an adoptive mother. However, the extent of such effects in a representative sample has not been measured.

Conclusion

In this brief review of past adoption practices, the focus has been on gathering evidence from the research literature that can be used to assist with understanding their impact, in order to develop appropriate responses to the needs of those who are affected.

The available information highlights the following themes:

- the wide range of people involved, and therefore the wide-ranging impacts and “ripple effects” of adoption beyond mothers and the children that were adopted;

- the grief and loss associated with past adoption practices, but also the usefulness of understanding past adoption practices as “trauma”, and seeing the impact through a “trauma lens”;

- the ways in which past adoption practices drew together society’s responses to illegitimacy, infertility and impoverishment;

- anecdotal evidence of the diversity of practices and lack of uniformity of experience;

- the role of choice and coercion, secrecy and silence, blame and responsibility, the views of broader society, and the attitudes and specific behaviours of organisations and individuals;

- the ongoing impacts of past adoption practices, including the process of reunion between mothers and their now-adult children, and the degree to which the reunion is seen as a “success” or not; and

- the need for information, counselling and support for those affected by past adoption practices.

A common theme across all of the research is the pervasiveness of the silence and shame, and the effect this has had in terms of isolation, lack of support and specific services. Marshall and McDonald (2001) argued that long-term pain for relinquishing mothers could have been relieved if they had had help in dealing with the relinquishment, accompanied by support and the opportunity to know something about the child (p. 73).

Based on her advocacy work with mothers who have been separated from their babies by adoption, Lindsay (1998) identified what she saw as being essential for the healing process, and for which society—rather than individuals—are responsible:

- availability of ongoing counselling with highly skilled psychologists;

- provision of trauma counselling services pertaining to mothers and children traumatised by adoption separation;

- establishment of advertising campaigns encouraging mothers to speak out;

- provision of education programs for GPs and other health services providers; and

- avoidance of statements that are likely to re-traumatise (e.g., referring to “unwanted babies”, “your decision”, “birth mother”, “think about how the adoptive parent feels”).

At the conclusion of their groundbreaking Australian empirical study, Winkler and van Keppel (1984) recommended that two things were most needed for these women:

- counselling and support; and

- increased information.

The efficacy of these various services or actions have not been empirically tested in relation to the specific population group; however, they are consistent with the broader theoretical and empirical literature on other forms of trauma, such as the field of child abuse and neglect or adult sexual assault (Connor & Higgins, 2008; van der Kolk & McFarlane, 1996). As with other groups who have experienced pain and trauma, having society recognise what has occurred (i.e., naming it, and understanding how it occurred and its impact) is an important element in coping with and adjusting to the deep hurt they have experienced.

As past adoption practices cannot be “undone”, one of the steps in the journey for both mothers and children given up for adoption is the choice around reunion. Given the variability in responses provided in the case study literature, and the absence of any systematic empirical evidence, this is an area where further research would be of particular value. Services attempting to support those affected—including professional counsellors, agencies and support groups—would all benefit from a greater understanding of typical pathways through the reunion process, estimates of the number of reunions that have occurred, the perspectives of those involved, and factors that are associated with positive and negative reunion experiences.

Apart from these issues relating to reunion, there are other ongoing issues for mothers affected by past adoption practices, including problems with:

- personal identity (the concept of “motherhood” and self-identity as a good mother);

- relationships with others, including husbands/partners, subsequent children;

- connectedness with others (problematic attachments); and

- ongoing anxiety, depression and trauma (Higgins, 2010).

The focus of the current literature review has been on the young women who relinquished babies to adoption and the effect of this on their lives, and to a lesser extent, the adopted children (particularly in relation to reunions). However, it is important to also consider the perspectives of biological fathers and other family members, such as children, partners, siblings, grandparents and the adoptive parents. In particular, there is little research to help understand the experience of men—both those who were adopted, and those who were biological fathers of children “relinquished” to adoption (Coles, 2009; Frame, 1999; Marshall & McDonald, 2001).

This review has shown that past adoption practices can have lifelong consequences. Although there is a wealth of historical records that could be examined, there is little systematic research on adoption experiences in Australia up to the key changes in the 1970s. In assessing the value of the research literature in understanding the context and impact of past adoption practices, it is important to acknowledge that we are viewing past behaviour and judging it by the standards of today, with the benefit of hindsight. This does not discount the impact of these practices on those affected. Views about the moral correctness of past practices, or even the contributions of individuals or institutions are evident in the literature, and while this material is distinguished from research, its significance is still acknowledged. For example, while acknowledging the pain and suffering of those affected by these past practices, the Parliament of Tasmania Joint Select Committee (1999) aptly summed up what the body of literature also shows:

In hindsight, it is believed that if knowledge of the emotional effects on people was available during the period concerned, then parents may not have pushed for adoption to take place and birthmothers may not have, willingly or unwillingly, relinquished their children. Witnesses and respondents [to the Inquiry], who include some adopted children, would not therefore be experiencing the pain and suffering which continues to influence their lives. (p. 11).

Commentators, experts, researchers and parliamentary committees have all accepted that past adoption practices were far from ideal, had the potential to do damage, and often did. What is often left unspoken is the issue of responsibility. It is implicit in discussions around the adequacy of consent (and the allegation of widespread immoral and illegal behaviours, such as failing to advise about rights of revocation, administration of high levels of drugs that could affect decision-making ability, etc.). In addition to the choice and volition of the woman involved (however impeded or affected), questions remain about how these past events occurred, and the current needs of those affected. Taking the time to understand the full extent of the impact of past practices is needed in order to be able to tailor appropriate service responses to meet the needs of those affected.

Endnotes

1 For example, Commonwealth financial support for unwed mothers was not routinely available until the introduction of the Supporting Mother’s Benefit in 1973.

2 Although the focus of this paper is Australian research on past adoption practices, limited references are made to overseas literature where relevant — particularly that of New Zealand — and where documents were easily accessible.

3 Empirical research refers to studies where researchers base their conclusions on data collected systematically via a direct or indirect method, and utilising recognised methods of analysis to synthesise the information or test hypotheses. In this brief review, I have focused on empirical qualitative and quantitative studies (for a full summary, see Higgins, 2010, Appendix A).

4 It is important to note that during the decades when great numbers of women were surrendering children for adoption (including the 1970s), the major social institutions of government, church and the law were governed almost entirely by men (Marshall & McDonald, 2001, p. 80).

5 Discriminatory practices were exemplified by the use of file markers such as “UB” (short for “Unmarried—Baby for adoption”), which determined the social work and nursing practices (Farrar, 1998). Such practices have been understood by some writers to be punishment for the “moral failure” of the women, with activities being carried out unsympathetically by staff.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2010). Adoptions Australia 2008–09 (PDF 475 KB) (Child Welfare Series No. 48; Cat. No. CWS 36). Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from <www.aihw.gov.au/publications/>.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment: Vol. 1. Attachment and loss. London: Hogarth.

- Cole, C. A. (2009). The thin end of the wedge: Are past draconian adoptive practices re-emerging in the 21st century? Public submission to the National Human Rights Consultation (PDF 96 KB). Retrieved from <www.humanrightsconsultation.gov.au/www/nhrcc/submissions.nsf/list/298F895A0A1C6D37CA2576240003405F/$file/Christine%20Cole_AGWW-7T29E8.pdf>.

- Coles, G. (2009). Why birth fathers matter. Australian Journal of Adoption, 1(2). Retrieved from <www.nla.gov.au/openpublish/index.php/aja/article/view/1542/1847>.

- Condon, J. T. (1986). Psychological disability in women who relinquish a baby for adoption. Medical Journal of Australia, 144, 117–119.

- Connor, P. K., & Higgins, D. J. (2008). The “HEALTH” Model: Part 1. Treatment program guidelines for complex PTSD. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 23(4), 293–303.

- Durey, J. (1998). Loss, adoption and desire. In Separation, reunion, reconciliation: Proceedings of the Sixth Australian Conference on Adoption, Brisbane, June 1997 (pp. 101–115). Stones Corner, Qld: J. Benson for Committee of the Conference.

- Farrar, P. D. (1998). “What we did to those poor girls!” The hospital culture that promoted adoption. In Separation, reunion, reconciliation: Proceedings of the Sixth Australian Conference on Adoption, Brisbane, June 1997 (pp. 116–127). Stones Corner, Qld: J. Benson for Committee of the Conference.

- Farrar, P. D. (2000).Relinquishment and abjection: A semanalysis of the meaning of losing a baby to adoption. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Technology, Sydney. Retrieved from <www.nla.gov.au/openpublish/index.php/aja/article/viewFile/1179/1448>.

- Frame, T. (1999). Binding ties: An experience of adoption and reunion in Australia. Alexandria, NSW: Hale & Iremonger.

- Gair, S. (2008). The psychic disequilibrium of adoption: Stories exploring links between adoption and suicidal thoughts and actions. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 7(3), 1–10.

- Goodwach, R. (2001). Does reunion cure adoption? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 73–79.

- Harkness, L. (1991). Looking for Lisa. Sydney: Random House Australia.

- Harper, J. (1992). From secrecy to surrogacy: Attitudes toward adoption in Australian women’s journals 1947–1987. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 27(1), 3–16.

- Higgins, D. J. (2010).Impact of past adoption practices: Summary of key issues from Australian research. Final Report to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Retrieved from </www.fahcsia.gov.au/our-responsibilities/families-and-children/publications-articles/impact-of-past-adoption-practices-summary-of-key-issues-from-australian-research>.

- Inglis, K. (1984). Living mistakes: Mothers who consented to adoption. North Sydney, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Iwanek, M. (1997). Healing history: The story of adoption in New Zealand. Social Work Now, 8, 13–17.

- Jones, C. (2000). Adoption: A study of post-war child removal in New South Wales. Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 86(1), 51–64.

- Lawson, D. F. (1960). The R. H. Fetherston Memorial Lecture: The anxieties of pregnancy. The Medical Journal of Australia, 30 July, 164–166.

- Ley, P. (1992). Reproductive technology: What can we learn from adoption experience? In P. Swain & S. Swain (Eds.), The search of self: The experience of access to adoption information (pp. 100–111). Sydney: Federation Press.

- Lindsay, V. (1998). Adoption trauma syndrome: Honouring the survivors. In Separation, reunion, reconciliation: Proceedings of the Sixth Australian Conference on Adoption, Brisbane, June 1997 (pp. 239–254). Stones Corner, Qld: J. Benson for Committee of the Conference.

- Marshall, A., & McDonald, M. (2001). The many-sided triangle: Adoption in Australia. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press.

- NSW Legislative Council Standing Committee on Social Issues. (2000).Releasing the past: Adoption practices 1950–1998. Final Report. Sydney: Government Printers. Retrieved from <www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/parlment/committee.nsf/0/56E4E53DFA16A023CA256CFD002A63BC>.

- Parliament of Australia Senate Community Affairs Committee. (2004). Forgotten Australians: A report on Australians who experienced institutional or out-of-home care as children. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from <www.aph.gov.au/senate/committee/clac_ctte/completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/report/index.htm>.

- Parliament of Tasmania Joint Select Committee. (1999). Adoption and related services 1950–1988 (PDF 213 KB). Retrieved from <www.parliament.tas.gov.au/Ctee/reports/adopt.pdf>.

- Rickarby, G. (1998). Adoption grief: Irresolvable aspects. In Separation, reunion, reconciliation: Proceedings of the Sixth Australian Conference on Adoption, Brisbane, June 1997 (pp. 54–58). Stones Corner, Qld: J. Benson for Committee of the Conference.

- Swain, P. (1992). Adoption information services: Myths and realities. In P. Swain & S. Swain (Eds.), The search of self: The experience of access to adoption information (pp. 25–37). Sydney: Federation Press.

- Swain, S. (1992). Adoption: Was it ever thus? In P. Swain & S. Swain (Eds.), The search of self: The experience of access to adoption information (pp. 2–16). Sydney: Federation Press.

- Swain, S., & Howe, R. (1995). Single mothers and their children: Disposal, punishment and survival in Australia. Oakleigh, Vic: Cambridge University Press.

- van der Kolk, B. A., & McFarlane, A. C. (1996). The black hole of trauma. In B. A. van der Kolk, A. C. McFarlen & L. Weisaeth (Eds.), Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body, & society (pp. 3–23). New York: Guildford.

- Winkler, R., & van Keppel, M. (1984). Relinquishing mothers in adoption: Their long-term adjustment (Monograph No. 3). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Winkler, R., Brown, D. W., van Keppel, M., & Blanchard, A. (1988). Clinical practice in adoption (Psychology Practitioner Guideline Books). Oxford: Pergamon.

Higgins, D. (2011). Unfit mothers … unjust practices? Key issues from Australian research on the impact of past adoption practices. Family Matters, 87, 56-68.