Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children

An overview

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2012

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

What is Footprints in Time?

Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) is an Australian Government-funded survey managed by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA). It is guided by a steering committee of experts in the fields of early childhood, education and health, which has been chaired by Professor Mick Dodson AM since 2003. LSIC was established to help us understand how what happens to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in early childhood affects their later life. The study looks at the different developmental pathways Indigenous children take to see what contributes to improved social, emotional, educational and developmental outcomes.

Footprints in Time began with two years of consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and service providers to shape the study design. These consultations were followed by community trials and then pilot studies, with the assistance of the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).1

The consultations emphasised the need to work collaboratively with communities and ensure that Indigenous people were involved in the research (Penman, 2006). This was done by having a steering committee with a majority of Indigenous members guide the research, by surveying people according to particular geographical areas, and by employing Indigenous people to work on the study, including conducting the interviews. The study involves extensive and continuing engagement with Indigenous communities, organisations and service providers. The LSIC Indigenous research administration officers usually conduct interviews and engage with the community in the same general area in which they live.

Agreement with and approval for the study was sought from Elders and communities in each geographical area, and ethics clearance was obtained at both jurisdictional and national levels. The Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing ethics committee was chosen as the primary human research ethics committee for LSIC.

Drawing on the consultations, Footprints in Time focuses on positive outcomes, highlights strengths, and collects data that are relevant and useful and can lead to positive change. LSIC is committed to providing feedback to families and communities, and this is done in a variety of formats, including site feedback sheets, DVDs and community booklets.

Further information about the study's design, development and key research questions can be found in the LSIC Wave 1 Report (FaHCSIA, 2009).

Study design

Surveys began in March 2008 and are conducted annually, in "waves". When this article goes to press, LSIC will have three waves of data available to users, as well as Wave 5 in the field and Wave 6 in design. The annual interviews help interviewers to develop relationships with participants, find a highly mobile population, and manage missing data from respondents who may need to skip a wave.

Like Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), LSIC employs an accelerated cross-sequential design involving two cohorts: one aged from 6 months to 2 years (Baby or B cohort) and one aged from 3 years and 6 months to 5 years (Kindergarten or K cohort) in Wave 1 (Table 1). The design allows data covering the first 9 or 10 years of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children's lives to be collected in 6 years. Additionally, from Wave 4, the ages of the two cohorts overlap, allowing for greater numbers of children to be analysed at that age range, and improving the statistical power of results. Of the study children, 88% are Aboriginal, 6% are Torres Strait Islanders and 6% are both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

| Year born | 2008 Wave 1 | 2009 Wave 2 | 2010 Wave 3 | 2011 Wave 4 | 2012 Wave 5 | 2013 Wave 6 | 2014 Wave 7 | 2015 Wave 8 | 2016 Wave 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cohort | 2006-08 | 6 months- 2 years | 1½-3 years | 2½-4 years | 3½-5 years | 4½-6 years | 5½-7 years | 6½-8 years | 7½-9 years | 8½-10 years |

| K cohort | 2003-05 | 3½-5 years | 4½-6 years | 5½-7 years | 6½-8 years | 7½-9 years | 8½-10 years | 9½-11 years | 10½-12 years | 11½-13 years |

Data are collected using face-to-face computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI). The primary respondent is the study child's primary parent or carer (usually their mother). Direct assessments of the study children are undertaken, including vocabulary and school readiness measures, height and weight. Where possible, interviews are also conducted with another primary carer of the study child. (In Waves 1 and 2, this could include grandmothers, aunts and other significant carers. However, as fathers were the usual respondents, the interview for the second primary carer was developed specifically for fathers from Wave 4 onwards).

In Wave 4, a touch-screen computer was introduced so that the children in the study could select their own answers for assessments such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children and Progressive Achievement Test - Reading. As the study children grow up, they are asked more questions and will eventually do a computer-assisted self-interview. In Wave 5, the computer asks some questions in English, Kriol, Torres Strait Creole or Djambarrpuyngu, one of the languages spoken in Galiwin'ku. An annual survey is also sent, with parent/carer permission, to the primary teacher/child care teacher of the child, and this may be completed on paper or online.

FaHCSIA publishes a key summary report of findings from each wave, which can be found at <www.fahcsia.gov.au/lsic>.

Response rates are encouragingly high. By Wave 2, of the 1,671 primary carers in the sample from Wave 1, 1,523 remained (86% retention) (see Table 2). Only 42 did not want a Wave 2 interview, 45 had moved to places too far away for our interviewers to travel and a further 61 were not able to be contacted for an interview. There were 88 new entrants in Wave 2 - these were people to whom the interviewers could not travel during the Wave 1 fieldwork period. In Wave 3, there were 1,404 primary-carer respondents, giving an 86% retention rate despite high mobility within sites. By Wave 4, the retention rate was 82%, with 1,283 primary carers interviewed.

| Total number | Previous wave respondents a | Additional interviews | Percentage of total sample (n = 1,759) | Retention from previous wave (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | 1,671 | ||||

| Wave 2 | 1,523 | 1,435 | 88 b | 86.58 | 85.88 |

| Wave 3 | 1,404 | 1,312 | 92 c | 79.82 | 86.15 |

| Wave 4 | 1,283 | 1,150 | 133 c | 72.94 | 81.91 |

Notes: a People interviewed in current wave who were also interviewed in the previous wave. b New entrants in Wave 2. c Interviewed in earlier wave but not the previous wave.

Where is Footprints in Time?

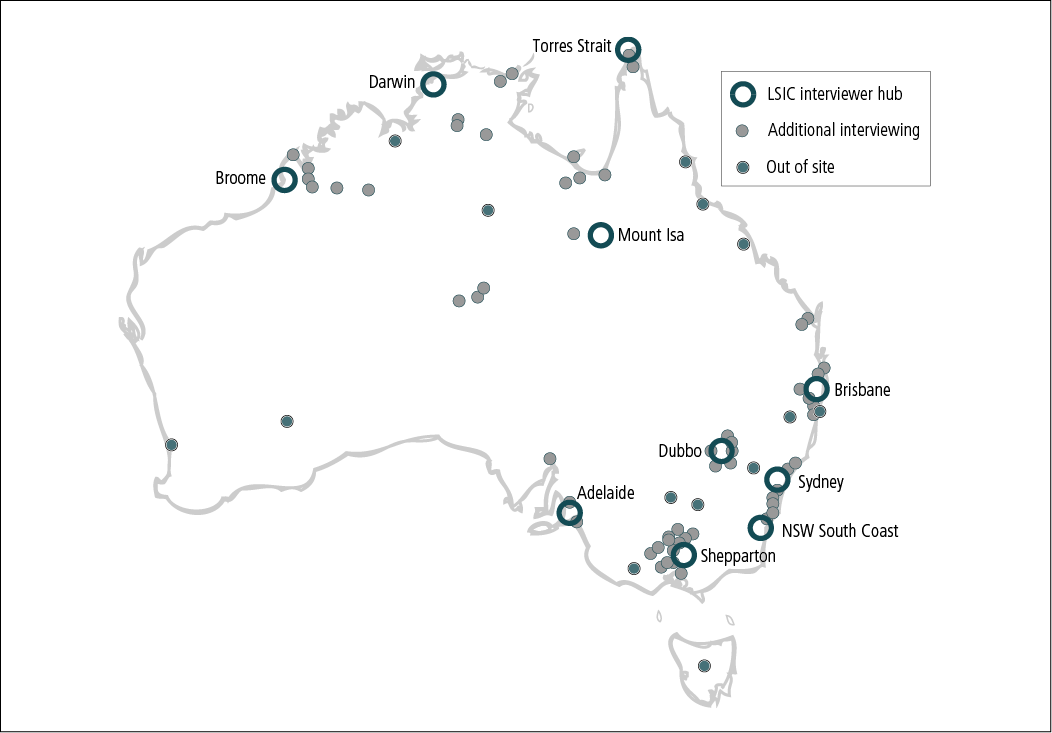

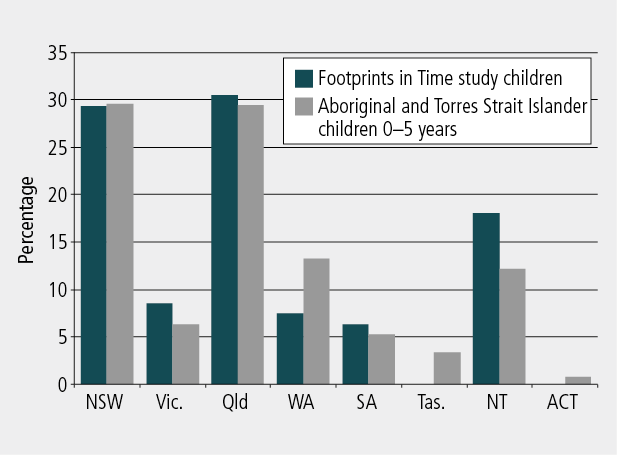

The map in Figure 1 shows LSIC interviewer worksites as open circles and additional interviewing as grey dots. Although only 11 sites were chosen for the study, they mirror the distribution of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population reasonably well, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Footprints in Time interviewing locations for Wave 3

Note: Alice Springs was an original site and Katherine was included during the Wave 1 fieldwork period. Neither have sufficient sample for a permanent interviewer.

Figure 2: Percentage of Indigenous children aged 0-5 years by total state population and Footprints in Time state population, Wave 1

Source: Data sourced from unpublished experimental Indigenous estimated residential population, June 2006 (ABS, 2006; ABS data available on request).

Footprints in Time sites were chosen to:

- ensure approximately equal representation of urban, regional and remote areas to enable some geographical comparison;

- represent the concentration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across Australia's states and territories; and

- have a substantial Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population both within the sites and in the surrounding areas.

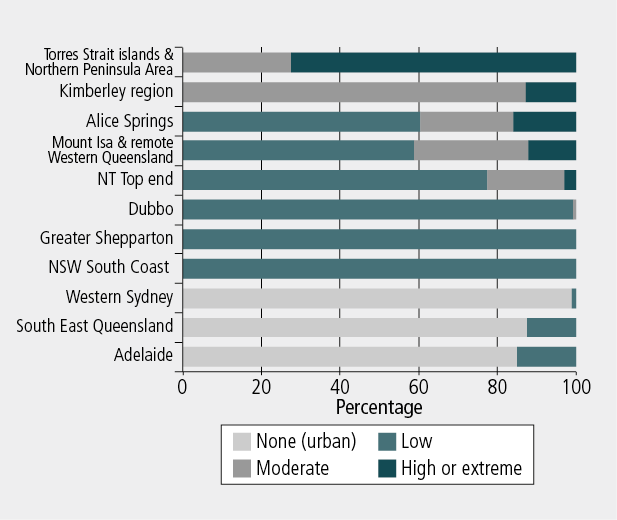

Footprints in Time data use a classification system of remoteness known as the Level of Relative Isolation (LORI) (Zubrick et al., 2005), indicating the relative distance of localities from population centres of various sizes. LORI has been designed to take account of Indigenous language and other culturally specific geographic characteristics, as well as distance from services. Figure 3 shows how the LSIC sites fit into the LORI classifications.

Figure 3: Level of Relative Isolation for LSIC sites in Wave 1

While quantitative data are a rich source of information, they can only describe events and circumstances within a narrow range of responses. To help further understand the richness and diversity of people's lives, LSIC collects and releases responses to open questions, as well as asking for any options not included in pre-set response lists. LSIC is committed to ensuring that the voice of the respondents is heard and that they have the opportunity to express themselves in their own words. LSIC includes an "other" option in many of the questions and respondents are asked to specify their response in this category. There are also a number of "free text" questions for which interviewers type responses verbatim. These qualitative data are made available to researchers in a de-identified format. It is important for these data to be considered alongside the quantitative data. Some of the responses to questions are included in Box 1 and Box 2.

Box 1: Study children's responses to the question, "What would you like to be when you grow up?"

- A scientist, one that works with bugs.

- A vet - give animals treats when they have been good with their needles.

- Um, a cop, or a robber.

- Astronaut, then Prime Minister of Australia.

- Zoo-keeper of pandas.

- A girl captain - they look to see who is going to crash boats.

- Work in the community being a policeman.

- Receptionist at the council office.

Box 2: Wave 2 parent/carer responses to the request, "Tell me something that's happened to [child's name] since last year"

- She started up at preschool and has built her confidence up interacting with children her own age.

- Talking more, independent, helps clean up, tries to help washing up.

- Just developed a cheeky personality.

- Started prep, moved house closer to family.

- Grown a lot, went on first plane trip.

- Had a haircut and walking.

- She attends preschool three days a week and likes it very much, loves to sing.

- Learning to read and write, word and sound recognition, showing his feelings, has become helpful, knows the difference between right and wrong when being disciplined.

- Moved house, talking more in sentences, more active, loves sports.

- He's talking more, and seems more confident.

- Started school, he learnt to tie his shoe laces.

- He said his first word on Friday - he said "hello"; he was on the train and saying hello to people.

- Got grommets in her ears, has a baby brother now.

- Learnt how to be very careful with puppies, learning to be toilet trained.

- He is talking heaps, very forward for his age, kicking the football around and has good eye and hand coordination.

- Speaks more language, likes to dance to the Michael Jackson DVD.

How can you use Footprints in Time data?

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are one of the most studied groups in Australia, little information is collected about the experiences of early childhood and how they lead to later outcomes. LSIC fills this gap, following children as they move through the various stages of childhood.

One of LSIC's great strengths is the opportunity it presents to understand the substantial diversity within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities - cultural values, parenting, stress loads, attitudes to services, life circumstances and aspirations vary enormously. LSIC data can help unpack some of the variation in Indigenous children's stories, for the celebration of successes and resilience and for targeting areas for support.

LSIC data include much of the same content as LSAC. Researchers wishing to examine the effects of child care or preschool, social and emotional wellbeing or gender differences can use LSIC data to explore these issues for Indigenous children. They can also examine issues that are more specific to Indigenous children and their families: cultural values and activities, learning languages, the effects of racism and the stolen generations, how parents cope with stress, what parents and carers want for their children and what can help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to "grow up strong".

Researchers using the datasets honour the commitment to ensure that their research is available to study participants by registering their publications in FaHCSIA's Longitudinal Surveys Electronic Research repository (known as FLoSse).2

An example of published work using LSIC is the report commissioned by FaHCSIA in 2011 titled An Exploratory Analysis of the Longitudinal Survey of Indigenous Children, completed by Dr Nicholas Biddle. Dr Biddle found, among other things, that going to cultural events and identifying with a tribal group, language group or clan were associated with higher rates of participation in preschool, whereas children of participants who had experienced discrimination were significantly less likely to attend preschool. In addition, children who had lived in two or more homes since birth were less likely to attend preschool in comparison with those who had lived in the same home since birth.

LSIC research discussed at the 2011 Growing Up in Australia and Footprints in Time: The LSAC and LSIC Research Conference included:

- Learning Language, Learning Culture, by Laura Bennetts Kneebone;

- A Study of Indigenous Children's Developmental Outcomes: The Impact of Child, Family and Socio-Economic Characteristics, by Killian Mullan and Gerry Redmond;

- The Assessment of Temperament in 4- to 5-Year-Old Indigenous Children, by Keriann Little, Stephen Zubrick and Ann Sanson;

- Preschool Participation Among Indigenous Children, by Belinda Hewitt and Maggie Walter;

- Nutrition and Development, by Katherine Thurber; and

- Resilience and Educational Outcomes in Footprints in Time, by Annette Neuendorf, Fiona Skelton and Laura Hidderley.

Full abstracts for these papers are available at <www.aifs.gov.au/growingup/conf/2011/program.html>. The work of Laura Bennetts Kneebone, summarised briefly below, provides a good illustration of the relationships that can be explored using the LSIC data.

One of the outcomes tracked in LSIC is early language acquisition. This is measured through the MacArthur-Bates Short Form Vocabulary Checklist,3 a parent-rated list of words spoken by the study child, which gives a score out of 100.

A range of factors had significant associations with higher vocabulary scores in 2 and 3 year-olds, such as primary carer education level, child's social and emotional difficulties, and history of ear problems. Encouragingly, the data show that there is a lot that families can do to make a difference to their children's English vocabulary development.

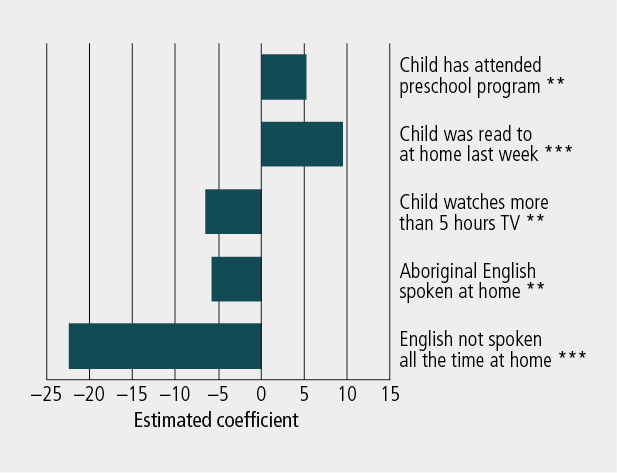

Figure 4 highlights some of the significant changes in a multivariate regression analysis, controlling for age, gender, parent education, child social and emotional difficulties, ear problems, Index of Relative Indigenous Socio-economic Outcomes (IRISEO),4 presence of a household wage and financial hardship. The analysis showed that children who were sent to preschool or a preschool program at a child care centre or had someone in the family read to them had significantly higher vocabulary scores, with a 5 and 9 point increase respectively. On the other hand, watching five or more hours of television a day led to an average decrease in scores of 7 points. Area-level socio-economic outcomes, household wage and financial hardship had no significant effect on toddlers' vocabulary. The association between preschool attendance and vocabulary, while not necessarily causal, provides support for the government's initiative to increase Indigenous children's preschool attendance under "closing the gap" measures.

Speaking Aboriginal English in the home had a negative effect on toddler English vocabulary scores (6 point decrease), as did being in homes where English was not spoken frequently (22 point decrease). It is important that the effects of language background on English development are understood by early educators so that these children can receive extra assistance as speakers of English as a second language, rather than being categorised as slow learners.

Figure 4: Relationship between selected child and family characteristics and change in MacArthur-Bates vocabulary score for Indigenous children, Wave 3

Notes: ** Statistically significant at the 5% level of significance only. *** Statistically significant at the 1% level of significance.

Development of LSIC data and future research

As the children in the study are getting older, LSIC is collecting a more diversified pool of both outcome measures and predictors. This is a tremendous resource for researchers interested in conducting ground-breaking analyses about what works for Indigenous children, on a proportionately large sample drawn from across Australia, including urban, regional and remote areas. With LSIC data, Indigenous children's and families' pathways can be tracked from the child's first year of life through preschool, primary school and beyond.

Outcome measures available now with Wave 3 data, or soon to be available with Wave 4, include vocabulary development, drawing and writing, reading and maths, cognitive reasoning (pattern recognition), children's strengths and difficulties, height, weight and general health. Future linkages to the Australian Early Development Index and National Assessment Program - Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) scores will provide detailed data on school readiness and school-based learning outcomes.

Parents or carers are also asked about children's temperament, development of motor skills, dental health, sleep and nutrition. Use of playgroup and child care, entry to school, parent involvement and attitudes to school and learning form a central part of the study. Context is provided through linking to indices showing Level of Relative Isolation, socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA) and Indigenous socio-economic outcomes, as well as by asking demographic questions about family finances, work, education, housing, mobility and child support.

Specifically sourced or designed questions attempt to provide answers about the role of culture. Family composition, involvement and activities form a major focus every year. Indigenous languages, activities with different family members, participation in cultural activities, access to cultural leave from work, values, and connection to country have all been included in interviews tailored specifically to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.

Specific research projects could focus on parent social and emotional wellbeing, parenting style, smoking, housing, service use, pregnancy and birth and much more.

Under the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, governments across Australia have committed to closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous life circumstances and overcoming Indigenous disadvantage. LSIC can inform most of the Closing the Gap building blocks, from healthy homes to schooling. As Professor Dodson says, "I hope that you will be inspired to take up the challenge and apply this information to improve policy responses for the benefit of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples" (FaHCSIA, 2011).

Accessing LSIC data

To apply for access to LSIC data, available in SAS, STATA and PASW formats, please log on to <www.fahcsia.gov.au/lsic>. Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers are encouraged to apply for the datasets. FaHCSIA encourages potential data users to draw on the strengths of an interdisciplinary approach, in partnership with Indigenous collaborators.

Further information about LSIC can be obtained from the LSIC website at <www.fahcsia.gov.au/lsic>. General inquiries can be emailed to <[email protected]>; data enquiries can be emailed to <[email protected]>.

Endnotes

1 Reports from the consultations, a commissioned literature review and qualitative research from the trials are available at <www.fahcsia.gov.au/lsic>.

2 See <flosse.fahcsia.gov.au>.

3 MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (CDIs) (Fenson et al., 2007) measure vocabulary growth over time and this measure was administered in Waves 1, 2 and 3 to parents of the Baby cohort. Parents were asked to identify the words that their child currently understands from lists of words that a growing child might be expected to say. Parents were able to respond that their child understood but did not say the words, or that the child understood and said these words in either English or another language. The MacArthur-Bates Short Form Vocabulary Checklist and other child measures are discussed in more detail in the appendix of the Key Summary Report from Wave 2 available from <www.fahcsia.gov.au/lsic>.

4 IRISEO uses nine measures of socio-economic outcomes across employment, education, income and housing from the 2006 Census to create a single index for 37 Indigenous regions and 531 Indigenous areas. As with SEIFA, the lower the decile, the greater the level of disadvantage (Biddle, 2009).

References

- Biddle, N. (2009). Ranking regions: Revisiting an index of relative Indigenous socio-economic outcomes(CAEPR Working Paper No. 49). Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR), Australian National University. Retrieved from <caepr.anu.edu.au/Publications/WP/2009WP50.php>.

- Biddle, N. (2011). An exploratory analysis of the Longitudinal Survey of Indigenous Children (CAEPR Working Paper No. 77/2011). Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR), Australian National University. Retrieved from <caepr.anu.edu.au/Publications/WP/2011WP77.php>.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2009). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Key summary report from Wave 1. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2011). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Key summary report from Wave 2. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Fenson, L., Marchman, V. A., Thal, D. J., Dale, P. S., & Reznick, S. (2007). The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User's guide and technical manual (2nd Ed.). Baltimore: Brookes.

- Penman, R. (2006). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander views on research in their communities (Occasional Paper No. 16). Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Zubrick, S., Silburn, S., Lawrence, D., Mitrou, F., Dalby, R., Blair, E. et al. (2005). The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal children and young people. Perth: Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research.

Bennetts Kneebone, L., Christelow, J., Neuendorf, A., & Skelton, F. (2012). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. An overview, Family Matters, 91, 62-68.