Workplace support, breastfeeding and health

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2013

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Though breastfeeding is important to both maternal and child health, few Australian infants are breastfeed as recommended - particularly among employed new mothers. This study aimed to identify the key barriers to and supports for combining breastfeeding with employment in workplaces. Based on survey data from 304 women from 62 different workplaces - who had returned to work after initiating breastfeeding - the study examined the associations between employment, leave and workplace factors, and exclusive breastfeeding at six months. Maternal work absenteeism and mother and child health were also examined. The study found that greater workplace support for breastfeeding through part time work, adjustable working hours, and perceived workplace support was significantly associated with exclusively breastfeeding at six months. Furthermore, not exclusively breastfeeding was associated with more frequent infant hospitalisations and time off work caring for a sick infant.

This paper aims to identify best-practice strategies for breastfeeding support in the Australian workplace. It uses data from Australian employers and their female employees who had initiated breastfeeding and returned to work. Our aims were to (a) identify key barriers to and enablers of combining breastfeeding with employment, including employment arrangements and workplace factors linked with exclusively breastfeeding for six months; and (b) explore the implications for maternal/child health and absenteeism of infant feeding practices among employed women.

Breastfeeding, health and employment

Breastfeeding is important to both maternal and child health. The World Health Organization (WHO; 2003) recommends six months of exclusive breastfeeding and continued breastfeeding to two years and beyond. However, the most recent national survey of infant feeding practices in Australia, conducted in 2010, showed that just 2% of Australian infants are exclusively breastfed for six months, with only 15% to six months (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2011). The effects of premature weaning on maternal and child health, and child cognitive development are now well-established (Büchner, Hoekstra, & van Rossum, 2007; Horta, Bahl, Martinez, & Victora, 2007; Ip et al., 2007; Kramer et al., 2008). Low breastfeeding rates translate directly into higher illness and disease, with substantial health system cost effects (Bartick & Reinhold, 2010; Renfrew et al., 2012; Smith & Harvey, 2011; Smith, Thompson, & Ellwood, 2002).

In Australia, as in many industrialised countries, exclusive and sustained breastfeeding has become a public health priority (European Commission Directorate Public Health and Risk Assessment, 2008; National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC], 2003; National Breastfeeding Advisory Committee of New Zealand, 2009; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). In 2010, national health ministers endorsed an Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy to increase breastfeeding, including among employed mothers (Australian Health Ministers' Conference [AHMC], 2009). This followed a federal parliamentary inquiry that investigated links between premature weaning, illness and chronic disease, and the sustainability of Australia's health system (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Aging, 2007).

Lack of accommodation of women's needs in employment results in lower national productivity growth because this source of highly educated labour - in scarce supply - is underused (Toohey, Colosimo, & Boak, 2009). Poor maternal or child health may also affect employers through parental absenteeism if breastfeeding is not catered for (Cohen, Mrtek, & Mrtek, 1995). As Sex Discrimination Commissioner Elizabeth Broderick (2012) has pointed out, if national productivity growth is to be maintained, there is a need to recognise the different life cycles of men and women and apply that knowledge to develop good policy solutions and business practices:

[In 2012], there is still a fundamental mismatch between unpaid caring work and workplace structures and cultures. If we continue to refuse to recognise that workplaces are part of the social context in which individuals make their decisions on work and family, we will struggle to achieve significant progress. Our seemingly "private" decisions are in fact shaped by the public context in which they are made. (p. 207)

For over a decade, increased public attention has been given to helping employees balance work and family, though this has not been evenly spread throughout the economy (Earle, 2002). Analysis and documentation of "best practice" breastfeeding support in workplaces provides a potentially useful tool. Such documentation can inform workplaces and managers on the extent and nature of effective supports currently available, shaping community expectations and encouraging a wider adoption of such practices. It is also important to identify any potential payoffs to employers and the health system from such measures, to ensure family-friendly strategies become embedded in business practices and public policy.

Breastfeeding, employment and workplace support: Policy and research context

Workforce participation rates among new mothers have risen in Australia in recent years (Eldridge & Croker, 2005), with the proportion of mothers of infants who are employed rising from 30% in 1991 to 41% in 2011 (Baxter, 2013). Around one-fifth of Australian mothers return to work by six months (Baxter, 2008). International research has shown lower rates of breastfeeding among employed than non-employed mothers, especially those returning before breastfeeding is established or to full-time employment (self-employment and part-time work hours affect breastfeeding less) (Berger, Hill, & Waldfogel, 2005; Chatterji & Frick, 2003; Fein & Roe, 1998; Gielen, Faden, O'Campo, Brown, & Paige, 1991; Guendelman et al., 2009; Hawkins, Griffiths, & Dezateux, 2007; Kurinij, Ezrine, & Rhoads, 1989; Lindberg, 1996; Roe, Whittington, Fein, & Teisl, 1999; Ryan, Zhou, & Arensberg, 2005; Thulier & Mercer, 2009; Visness & Kennedy, 1997; Winicoff & Castle, 1988). In the United States, a lack of post-partum leave leads to early cessation of breastfeeding, especially among women who are non-managerial employees, lack job flexibility or are experiencing high psychosocial distress (Guendelman et al., 2009).

In Australia, similarly, mothers returning to work before six months are less likely to be breastfeeding at six months than mothers who are not employed (Baxter, Cooklin, & Smith, 2009; Cooklin, Donath, & Amir, 2008). A study of breastfeeding and employment using data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children showed that mothers of infants aged 4-12 months who worked 15 hours or more had considerably lower breastfeeding rates than not-employed mothers, after controlling for background characteristics (Baxter, 2008). Job characteristics such as working flexible hours were also associated with higher breastfeeding rates (Baxter, 2008). Occupational status was not a significant determinant of breastfeeding at six months in Australia. Self-employed Australian mothers were more likely to be breastfeeding than employees, as was found in the UK (Hawkins et al., 2007).

In 2010, the Australian Infant Feeding Survey found that while 60% of all infants were breastfed at age six months, fewer (52%) were breastfed if the mother had been employed at any time since the birth of the child (AIHW, 2011). Likewise, 42% of all 7-12 month olds were breastfed, but only 34% were breastfed if the mother was employed. Mothers who wish to breastfeed may delay returning to work if their workplaces do not provide a supportive environment (Mandal, Roe, & Fein, 2012).

Policy concerns and responses

Achieving public health policy goals and maintaining national productivity will require identifying and addressing employment and workplace barriers to exclusive and sustained breastfeeding. Alongside the leave offered by Australia's new Paid Parental Leave scheme, ensuring adequate workplace support for breastfeeding is another option. For example, a study analysing the 2005 Parental Leave in Australia Study found that while needs were diverse, women (especially full-time employees) saw better breastfeeding facilities as a work-family policy that would help after the birth of a child, while work-based child care was also cited in relation to assisting breastfeeding (Renda, Baxter, & Alexander, 2009).

Governments around the world have responded to the potential conflict of maternal paid employment and breastfeeding in three main ways. Firstly, since at least 1919, they have regulated employment conditions to provide maternity protection, such as through requiring employers to provide maternity leave (Brodribb, 2012). Secondly, anti-discrimination legislation imposes responsibilities on employers to accommodate lactation and breastfeeding by their employees. The third approach has been through promoting best practice in breastfeeding support, such as by educating and supporting interested employers.

The most recent International Labour Organization (ILO) convention regarding maternity protection (C183) contains minimum standards for lactation breaks and paid maternity leave (ILO, 2000). It recommends a right for women to have a minimum of 14 weeks' paid maternity leave and one or more daily lactation breaks or a daily reduction of hours of work to breastfeed. It also recommends the establishment of facilities for nursing under adequate hygienic conditions at or near the workplace. In some countries, such as Norway, generous maternity leave means women face less financial pressure to return to employment while they are still breastfeeding, and around 40% still breastfeed at 12 months (Grovslien & Gronn, 2009).

Australian public health policy since the mid-1990s has explicitly promoted exclusive and sustained breastfeeding to six months (NHMRC, 2003), and was recently strengthened by the endorsement of a National Breastfeeding Strategy by all Australian Health Ministers (AHMC, 2009). However, national legislation on employment conditions and workplace protection for breastfeeding has been lagging, and Australia is yet to ratify the ILO Convention 183 regarding lactation breaks. There is no nationally legislated entitlement to lactation breaks in Australia, though some state government awards now include paid lactation break provisions. However, from January 2011, following public inquiries by the Commonwealth Parliament (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Aging, 2007) and the Productivity Commission (2009), a publicly funded Paid Parental Leave scheme provides eligible employees with up to 18 weeks of paid parental leave at the national minimum wage rate. The new federal government elected in September 2013 is promising to introduce a more generous employer-funded scheme that provides 26 weeks of paid leave to eligible employees. National Employment Standards also reflect the long-established entitlement of most employees to unpaid maternity leave of 12 months, and now include the right to request a further 12 months of leave (Fair Work Australia, 2009).

Anti-discrimination law is a second policy tool that has provided some protection for breastfeeding employees in Australia since the early 1980s. Courts in Australia have generally viewed breastfeeding as a condition associated with pregnancy or gender, and therefore broadly covered by provisions regarding discrimination on these grounds. Sex discrimination legislation has existed at both federal and state level since 1984 (Brodribb, 2012). In 1999, a Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) report into discrimination in pregnancy recommended that breastfeeding be specifically included as grounds for unlawful discrimination in federal legislation (Recommendation 43). Commonwealth legislation to this effect was finally passed in May 2011 (HREOC, 2011).1 The amendments widened the scope of protection against direct discrimination against employees on the grounds of family responsibilities, and also for the first time specifically addressed direct and indirect discrimination on the grounds of breastfeeding in employment. Employers must now reasonably accommodate the needs of breastfeeding women in the workplace. A recent study found that some breastfeeding women have experienced lack of support in child care services in Australia that could now be considered unlawful discrimination (Smith et al., 2013).

Australia has been at the forefront of a third approach, using community-based efforts to help mothers combine breastfeeding and paid work since the early 1980s (Eldridge & Croker, 2005). At that time, the Australian Breastfeeding Association (ABA), then known as the Nursing Mothers' Association, identified the need to support the growing number of women returning to paid employment, and developed the Mother Friendly Workplace Award (MFWA) program to encourage employers to provide facilities that supported their breastfeeding employees. The one-off awards were presented to workplaces that provided lactation breaks and facilities enabling women to express breast milk in private. The association developed evidence-based guidelines for employers on achieving a "breastfeeding-friendly" workplace in the mid-1990s (Horton, 1995; Nursing Mothers' Association of Australia & Department of Industrial Relations, 1995). To facilitate ongoing partnerships between the association and employers, the ABA replaced its MFWA program with Breastfeeding Friendly Workplace (BFW) accreditation from 2002.

In the late 1990s the Australian Government initiated a health promotion campaign targeting employers and employed mothers as part of a three-year National Breastfeeding Strategy. This developed a widely distributed information resource on combining breastfeeding and work to employers and women. Evaluation showed that more than two-thirds of the 202 employers surveyed found the kit provided useful solutions to combining breastfeeding and work (McIntyre, Pisaniello, Gun, Sanders, & Frith, 2002)

These initiatives have contributed substantially to a change in workplace culture and made breastfeeding support part of workplace best practice in Australia. Employers anticipate cost savings from supporting their staff to combine work and breastfeeding, and a number of high-profile private and public employers have sought accreditation under the ABA's BFW program (Eldridge & Croker, 2005). ABA experience has been that employers value the improved retention of female employees after maternity leave, which reduces the loss of skilled staff and costs associated with recruitment and retraining or replacement. Improved health of mother and baby and increased staff loyalty from this family-friendly intervention are also seen to provide benefits, including reduced absenteeism and staff turnover. Businesses also value the benefits to their corporate image from the public promotion and media recognition of BFW employers (Eldridge & Croker, 2005).

Most recently, responding to the issues identified in a parliamentary inquiry into breastfeeding, a 2007 Australian parliamentary report recommended increasing the number of workplaces that met the particular needs of mothers combining breastfeeding and work, by funding and extending the BFW accreditation program (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Aging, 2007). The Committee on Health and Ageing (2007) commented that:

Female employees have needs related to pregnancy, birth and lactation which need to be recognised. There is a real risk that if women are not supported, returning to employment can be an obstacle to breastfeeding to the point of affecting the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding, or even to the degree of weaning their infants (p. 78).

The committee's (2007) recommendation has not yet been acted upon, though the parliament accepted it should be "showing leadership in the area of breastfeeding and work" (p. 81) and achieved accreditation for workplaces at Parliament House under the BFW program in 2008. Provisions to support breastfeeding employees, including lactation breaks, also have been introduced within a growing number of workplaces in Australia. For example, reflecting public health strategies to protect and support breastfeeding in the Public Service in New South Wales and in Queensland, employees are entitled to take up to 60 minutes a day for expressing milk or breastfeeding.

While there is some evidence that policy measures such as those outlined above will enable more new mothers to establish and maintain breastfeeding (Baker & Milligan, 2008; Guendelman et al., 2009), there is little research identifying the full range of breastfeeding support strategies that are used by employers, workplaces and employees. There is also a lack of population-level studies identifying the measures that are most crucial for helping employed women maintain breastfeeding as recommended during the first year. While case studies in the US have shown potential benefits through reduced staff illness and absenteeism for breastfeeding-friendly employers (Cohen et al., 1995), there remains a dearth of studies evaluating effects of these strategies across a sample population of employers or workplaces.

This paper redresses that gap. Using data from Australian employers and their female employees who had initiated breastfeeding, we investigated:

- the employment arrangements and workplace factors that were linked with exclusively breastfeeding for six months;

- whether maternal and child health outcomes and work absences differed for employees who exclusively breastfed for the first six months, among those who returned to work during the first year; and

- what helped or hindered women who returned to paid work before six months to achieve their intentions about breastfeeding.

Method

Design and implementation

The workplace study took place between November 2010 and April 2011. It was a mixed-method design, and comprised two surveys: one targeted at employers and another targeted at their female employees with children aged two years or younger.2 The employer survey aimed to collect information from employers on the perceived costs and benefits of family-friendly and breastfeeding-friendly workplace policies and practices. The employee survey aimed to obtain information from female employees with young children about the main barriers to and enablers of breastfeeding experienced after return to work, and the potential effects of these on the health and wellbeing of their infant/young child and themselves.

The study sample of employees was drawn from 207 employing organisations, including 73 that had received BFW accreditation, 25 that had applied for accreditation, and 109 that had neither received nor applied for accreditation. These latter 109 organisations were participants at the 2010 Australian Human Resources Institute (AHRI) Convention in Melbourne, which had provided contact details to the ABA at a session on work and family issues. AHRI is the national association representing human resource and people management professionals in Australia. The employer questionnaire collected information about the organisation, such as industry characteristics, size, and public or private ownership.

Employers were requested to publicise an employee survey to their female employees with children aged less than two years. The employee questionnaire comprised 69 questions asking for information on demographic characteristics, infant feeding practices, and employment, job quality and workplace variables known to influence breastfeeding by employees. It also collected information on maternal and child health and wellbeing outcomes. The questionnaires could be completed either online or on paper and were pre-tested for validity and reliability.

Measures

Socio-demographic characteristics, employment and workplace factors

Key socio-demographic and employee factors considered relevant to infant feeding practices were maternal age, occupation, education level and family income. Employer factors included the industry, ownership and size of the company in which the employee worked.

To identify which employment arrangements, job quality and workplace factors were associated with exclusive breastfeeding at six months, we used variables including full- or part-time employment status, job quality and other workplace support indicators. Job quality was measured by job control ("freedom over how I work", "good deal of say in work decisions"), perceived security (difficult to get a comparable job, risk losing job if breastfeeding), flexibility, and access to paid family-related leave (Strazdins, Shipley, Clements, Obrien, & Broom, 2010). Workplace support was measured by a range of variables, including having a breastfeeding policy; supervisor and colleague attitudes to breastfeeding workers; having time flexibility (such as through lactation breaks, flexibility in hours worked or start and finish times, or being able to still attend mothers' groups or maternal child health clinics); type of job (standard hours versus weekends or shiftwork); being able to work at home; and having access to suitable facilities for expressing or storing milk.

These variables were identified from previous academic research on workplace support for breastfeeding, as well as from documentation of Australian experiences with programs such as the ABA's BFW accreditation program (Bar-Yam, 1998a, 1998b; Dabritz, Hinton, & Babb, 2009; Eldridge & Croker, 2005; Heinig, 2007; Horton, 1995; McIntyre et al., 2002).

Child health, and maternal health and wellbeing

We also examined whether employee mothers and their infants who had exclusively breastfed at six months reported different health and wellbeing outcomes to those who had not exclusively breastfed at six months. Child health status was measured by mothers' reports of the infant's general health status, and episodes up to infant age 12 months of several common childhood illnesses or conditions. For example, the mothers reported whether their infant had experienced hearing problems, eye problems, eczema, ear infections or other infections, diarrhoea or colitis, food/digestive allergies or asthma.

Maternal health and wellbeing was indicated by self-reported health status and measures of psychological distress. Mothers' health was measured from their reports of whether their health was "excellent", "very good", "good", "fair" or "poor". Maternal psychological distress was measured with items from the Kessler K6 screening scale (Kessler et al., 2002). Mothers reported how often they experienced symptoms of depression (six items, e.g., "Did you feel hopeless?") in five response categories, ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time).

Qualitative data collected from the 304 employee participants were thematically analysed to explore experiences, identify themes, and illustrate key barriers to and enablers of breastfeeding, as experienced by employed mothers of infants. A preliminary review identified descriptive categories from the patterns of employee responses to open-ended questions about barriers to and enablers of their continuing breastfeeding. Up to three barriers or enablers were identified from each of the responses. After review by investigators with expertise in breastfeeding and work issues, data were organised under themes, including mother- and baby-related factors (attitude, knowledge, preferences), employment hours or leave access, and workplace factors (including time flexibility, supervisor support for breastfeeding, and facilities for expressing and storing milk at the workplace), as well as social support available for combining breastfeeding and work (e.g., partner, ABA, child care, health professionals). Comments that illustrated the quantitative variables and the potential maternal and child health and wellbeing effects were identified.

Productivity implications

Individual workplace productivity and health system cost implications of exclusive breastfeeding were measured through mothers' reports of the number of infant-related work absences (Cohen et al., 1995), and the number of times the infant had been hospitalised since birth for reasons other than accident or injury (Smith et al., 2002).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented on how return-to-work influenced infant feeding practices and infant feeding outcomes for mothers who returned to work within two years of their child's birth (n = 304). Data for two subgroups, those who returned to work before six months (n = 92), and those who returned to work between 7 and 12 months (181), are also presented. The ages at which formula and solids were introduced, and the age at which breastfeeding ceased were also measured retrospectively by self-report.

Descriptive statistical analysis (Pearson's χ2) was used to explore the unadjusted relationships between maternal socio-demographic, employment and workplace factors, and exclusively breastfeeding at six months.3 The relationships between exclusive breastfeeding and child health and maternal health and wellbeing outcomes were also compared. Comparative analysis of means using two-tailed t-tests and chi-squared tests assessed whether there were differences in work days lost and hospitalisations for employees who had exclusively breastfed at six months and those who had not. Statistical significance was set at the .05 α-level.

Results

Participants

Employer characteristics

A total of 64 of the 207 employers participated in the employer survey, giving a response rate of 31%. Among the employer respondents, 34 organisations (or 55%) were accredited, 3 organisations had applied for accreditation and 25 organisations (40%) were not accredited. Accredited organisations had a higher response rate (47%) than either non-accredited organisations (23%) or those which had only applied for accreditation (12%). A summary of key characteristics of these employers is in Appendix Table A1.

Employee characteristics

A total of 356 employees from these organisations participated in the employee survey. Those who had not initiated breastfeeding and had not returned to work at the time of the survey were excluded from this analysis; the remaining 304 had breastfed and were in paid employment by the time their child was 2 years old, and are the focus of the analyses below.

A total of 273 employees had returned to work within 12 months. Of these, 92 had returned to work by the time the infant was six months old, and 181 between 7 and 12 months. Key socio-demographic characteristics are summarised in Appendix Table A2.

There was also no significant relationship between the proportion of employees exclusively breastfeeding at six months and whether the employer was a small/medium or large employer, whether the employer was privately or publicly owned, and whether the industry in which the mother was employed was gender-segregated (male- or female-dominated or inclined).

Among mothers who returned to work within six months (n = 92), there was no apparent relationship between exclusive breastfeeding at six months, and whether the employee was in a professional occupation, or in a sales, clerical, administrative, community or personal services occupation. There were also no statistically significant relationships between socio-demographic characteristics such as age, education or income, and exclusive breastfeeding at six months. However, a higher proportion of those with post-secondary education exclusively breastfed to six months (53%), compared to those with lower education (30%), and this difference approached significance (p = .071).

Breastfeeding intentions and outcomes

Table 1 presents data on the age of the infant at maternal return to work, alongside mothers' breastfeeding intentions and outcomes. It compares stated intentions for breastfeeding and key breastfeeding indicators for those who returned to work when their infant was six months or younger, those back at work within 7 to 12 months, and for the group as a whole.

| Mothers returning to work by 6 months (n = 92) | Mothers returning to work at 7-12 months (n = 181) | All mothers (n = 304) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age of baby when mother returned to work (months) | 4 | 9 | 8 |

| Breastfeeding intentions (%) | |||

| As long as possible | 23 | 19 | 20 |

| 6 months | 19 | 20 | 18 |

| At least 12 months | 51 | 57 | 55 |

| Breastfeeding practice | |||

| Exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months (%) | 48 | 54 | 54 |

| Breastfeeding at 12 months (%) | 29 | 45 | 45 |

| Return to work influenced: (%) | |||

| Breastfeeding initiation | 13 | 4 | 7 |

| Reducing or stopping breastfeeding | 58 | 47 | 48 |

| Would have returned to work sooner if breastfeeding supported | 8 | 5 | 6 |

For those who returned at six months or earlier, the age of the infants when the women returned to work averaged four months, compared to nine months for those returning between seven and 12 months. A higher proportion of mothers returning to work at six months or earlier (compared to those who returned at 7-12 months) reported they had planned to breastfeed "as long as possible" rather than specifying a duration, suggesting they had been less confident of their breastfeeding plans. A lower proportion reported that they had intended breastfeeding to at least 12 months, showing that they expected a shorter duration of breastfeeding than those women returning to work between 7 and 12 months.

Among those returning to work at six months or earlier (n = 92), a lower proportion than those who returned at 7-12 months (29% vs 45%) were exclusively breastfeeding at six months. Likewise a lower proportion (48% vs 54%) continued any breastfeeding to 12 months.

Mothers' views/intentions about breastfeeding also interacted with return-to-work plans. Among mothers returning to work at six months or earlier, 13% reported that returning to work influenced breastfeeding initiation, 58% reported reducing or stopping breastfeeding to return to work, and 8% reported that they would have returned to work earlier if breastfeeding had been supported. Among those returning to work after six months, somewhat fewer reported such compromises between returning to work and breastfeeding.

Employment effects on breastfeeding

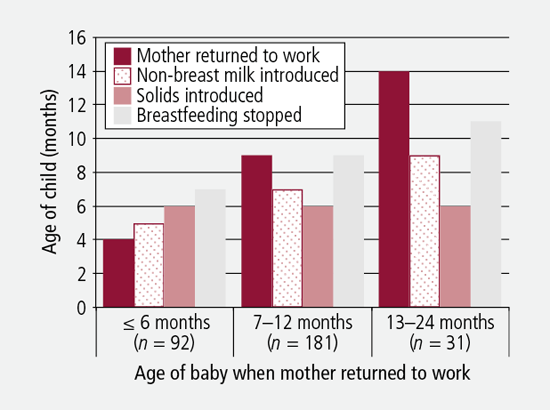

Figure 1 compares infant feeding milestones reported by employees who returned to work at six months or earlier compared to those back at work within 7 to 12 months, or by 2 years.

Figure 1: Infant feeding milestones by average age of baby when mother returned to work

Figure 1 shows solids were introduced at a similar infant age for the three groups, at around six months. However, the later the mother returned to work, the later the child ceased breastfeeding. In particular, those returning to work at six months or earlier introduced formula two months sooner and discontinued breastfeeding around two months sooner than those returning to work in the second half of the first year, differences that were statistically significant (p = .009 and p = .007 respectively). This may be because breastfeeding was not fully established for the mothers who returned within the first 12 weeks or so, so that maintaining milk supply was more difficult in later months. Alternatively, employees returning at six months or earlier may have found maintaining exclusive breastfeeding too time-intensive, as exclusive breastfeeding takes around 17 hours a week at 6 months of age (Smith & Forrester, 2013), and providing expressed breast milk for someone else to feed the baby is likely to take the mother at least a comparable amount of time overall.

Return to work, maternity leave arrangements

The relationships between returning to work and maternity leave factors, and exclusive breastfeeding at six months, were analysed for those returning to work by six months, (n = 92). This showed that, on average, mothers who returned to work before six months would have preferred leave of around 40-46 weeks, rather than the 21-22 weeks actually taken. No statistically significant relationship was found between the likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding at six months and whether the employee took <= 18 weeks or 19+ weeks of leave, or whether the employee preferred leave that was <= 18 weeks or 19+ weeks, though among those preferring <= 18 weeks leave, 78% (versus 49% among those preferring 19+ weeks) did not exclusively breastfeed to 6 months. The analysis also found no statistically significant relationship between exclusive breastfeeding and actual leave taken, and whether a gradual/flexible return to work was available to the employee.

Workplace support

Table 2 shows the relationships between various kinds of workplace support or job quality factors, and exclusively breastfeeding at six months, for those returning to work by six months.

| Workplace support factors | Exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months (%) | Not exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current work status | |||

| Part-time | 62 | 38 | .030 * |

| Full-time | 38 | 63 | |

| I have a say over how many hours worked | |||

| Agree | 56 | 44 | .067 |

| Disagree | 43 | 57 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 18 | 82 | |

| I can adjust hours to accommodate need to breastfeed or express milk | |||

| Agree | 65 | 35 | < .001 ** |

| Disagree | 43 | 57 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14 | 86 | |

| I have a say over start and finish times | |||

| Agree | 56 | 44 | .052 |

| Disagree | 24 | 77 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 38 | 63 | |

| Able to take long enough, or frequent enough, lactation breaks | |||

| Yes | 70 | 30 | .077 |

| No | 36 | 64 | |

| Does your organisation have a written policy of supporting mothers who express breast milk or breastfeed at work? | |||

| Yes | 61 | 40 | .016 * |

| No/unsure | 34 | 66 | |

| I would have returned to work sooner if my workplace was supportive of breastfeeding | |||

| Agree | 0 | 100 | .027 * |

| Disagree | 57 | 43 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 39 | 62 | |

| My manager/supervisor and colleagues think more poorly of workers who express breast milk or breastfeed at work | |||

| Agree | 43 | 57 | .075 |

| Disagree | 57 | 43 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29 | 71 | |

| A mother risked losing her job if breastfeeding or expressing milk in this workplace | |||

| Agree | 0 | 100 | .045 * |

| Disagree | 54 | 46 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25 | 75 | |

Notes: χ2 test of independence: ** p < .001, two-tailed test; * p < .05, two-tailed test.

A higher proportion of mothers who worked part-time were exclusively breastfeeding at six months than those working full time (p = .030). Among those who reported working part time, 38% were not exclusively breastfeeding at six months, compared to 63% of those working full time. Women who agreed/strongly agreed that they could adjust working hours for breastfeeding or expressing milk were more likely (65% vs 35%) to have exclusively breastfed at six months (p < .001). Likewise, those who had a say over start and finish times were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at six months (56% vs 44%) (p = .052). Being able to take lactation breaks also approached significance (p = .077), as did having a say over hours worked (p = .067).

A supportive workplace culture was also associated with higher proportions of employees having exclusively breastfed at six months, and vice versa. Among those who agreed they would have returned to work sooner if their workplace had been more supportive, none had exclusively breastfed (p = .028). Likewise, among those who agreed that "a mother risked losing her job if breastfeeding or expressing milk in this workplace", none exclusively breastfed (p = .045). Whether managers and work colleagues were perceived to think more poorly of workers expressing milk or breastfeeding at work also showed a negative trend relationship with exclusive breastfeeding at six months (p = .075). On the other hand, being aware of a workplace policy supporting breastfeeding was significantly associated with higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding. For example, in workplaces where mothers knew there was a breastfeeding policy, 61% exclusively breastfed at six months. In workplaces where the employees were unsure or knew there was no such policy, only 34% had exclusively breastfed (p = .016).

Other workplace or job quality factors were not significantly different between the two feeding groups, among mothers returning to work before six months. For example, there were no significant differences in responses on the following variables: whether standard hours worked, having the opportunity to work at home, never having enough time to get job done, freedom over how to do work, having a say in work decisions, perceived difficulty of getting another job with the same pay and hours, and being able to attend maternal child health services and community support groups' activities. There were also no significant differences on whether suitable facilities would be available at work for breastfeeding or expressing milk.

Maternal and child health outcomes

Previous research has suggested that infant health influences employee productivity through absenteeism (Cohen et al., 1995). Such effects could occur directly, for example, due to children being unwell (therefore perhaps being excluded from their child care service), or hospitalised (and requiring parental attendance), as well as because of employees experiencing stress related to their family responsibilities, which could indirectly affect their productivity in the workplace. Hospitalisation of an infant, for example, is likely to be a major problem for a mother at work, and could detract substantially from productivity.

Analysis of health indicators for exclusively breastfed infants compared with those not exclusively breastfed showed no statistically significant differences, though there was a slight trend towards better health in the exclusively breastfed group (p = .15). Among those returning to work at six months or earlier, 90% of those who had exclusively breastfed at six months reported their child's health as excellent or very good, and the other 10% as good, whereas among those not exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months, 9% reported their child's health as fair/poor.

Regarding differences in hospitalisation and maternal days off work, among women returning to work at between 7-12 months, the number of days off work spent caring for a sick infant was around four days for both feeding groups. For those returning at six months or earlier, among the exclusively breastfeeding group, an average of four days had been lost from work due to infant illness since the child had been born, compared to seven days among those who did not exclusively breastfeed at six months. This difference was in the expected direction and approached but did not reach statistical significance (p = .075).

There was a statistically significant difference (p = .022) in child hospital admissions since birth between the exclusively breastfeeding and not exclusively breastfeeding groups of mothers returning to work at 7-12 months. Among those who had not exclusively breastfed infants at six months, 22% reported one or more hospitalisations of the child, compared to only 9% of those who had exclusively breastfed to 6 months. Statistical testing (two-tailed t-tests) showed no significant difference in hospitalisation rates were found by age of the infants who were exclusively breastfed at 6 months compared to those not exclusively breastfed. While, as noted above, the overall health of the children was similar, we are unable to exclude reverse causation; that is, hospitalisation of the infant may have resulted in rather than been caused by not exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months.

Self-reported health of the mother was little different in the proportions reporting they had excellent/very good health between the feeding groups for mothers who returned to work before 12 months (not shown). Likewise, maternal psychological stress showed only a weak relationship to feeding category; among those returning to work at 7-12 months, a higher proportion of the non-exclusively breastfeeding mothers (22% vs 12%) reported that "everything was an effort" (p = .063). Notably, though, around two-thirds of all mothers (65-71%) who had returned to work by 12 months reported feeling rushed or pressured all or most of the time (not shown).

Barriers to and enablers of breastfeeding

Employees who had returned to work before their child was 2 years old (n = 304) reported on factors that helped them to achieve their breastfeeding intentions, including:

- support for ongoing breastfeeding from workplaces and supervisors;

- workplace facilities for expressing or storing milk;

- hours of work and flexible schedules; and

- maternal or infant preferences to breastfeed.

Mothers reported, for example, being helped by "having support from my manager, having a dedicated quiet room at work with proper facilities, fridge, sink and storage cupboard". Another stated that "a good breast pump" helped her achieve her intentions. "Flexibility to manage work and take breaks" was reported as being helpful. For another, what helped was "knowing it's the best thing for my child".

On the other hand, employee intentions to breastfeed were mainly hindered by time pressures and mother-infant separation arising from returning to work. Many experienced difficulties expressing sufficient milk and maintaining their milk supply, with problems maintaining breastfeeding reported to arise from separation during the work day. For example, "baby had breast refusal. [I] expressed for 2 months, but eventually dried up", "returning to work forced me to feed expressed milk in a bottle which both my children became [sic] to prefer to the breast", or "kids tend to wean themselves when their breast milk comes in a bottle. I had to work, I couldn't arrange leave to go and feed my baby, ergo he weaned himself". Another mother reported that:

although I still breastfeed, I have had to reduce the frequency. I do not breastfeed during the day due to lack of support from the workplace, unable to fit in milk expression with time constraints and lack of facilities (a private room and storage facility).

Mothers also cited lack of access to lactation breaks, having nowhere suitable to breastfeed, and lack of support from co-workers or managers as being barriers to their breastfeeding intention. One mother starkly illustrated the difficulties and adverse health consequences of an unsupportive workplace with her comment that:

Management is not agreeable to breaks being taken to express so I have been not expressing at work. This has led to mastitis and pain due to engorgement of my breasts and a reduction in the amount of milk I am able to produce. In essence, I am limited in my access to breaks and facilities which has led to detrimental health issues and a reduction in my ability to breastfeed my child.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to identify important workplace supports for exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months, and the potential implications for workplace productivity.

It has previously been shown that part-time work and flexible hours are important for employed mothers to maintain any breastfeeding (Baxter et al., 2009; Cooklin et al., 2008). Our qualitative and quantitative analysis shows that part-time work is also important for mothers to sustain exclusive breastfeeding to six months.

Other key findings are:

- breastfeeding reality was often less than breastfeeding intention, and mothers would have preferred longer leave;

- returning to work at or before six months meant formula started two months earlier and breastfeeding stopped two months earlier;

- where employees reported more workplace support for breastfeeding, more had exclusively breastfed at six months;

- a trend for employees who had exclusively breastfed for six months to have fewer days off work to care for a sick baby; and

- those who exclusively breastfed for six months and returned to work at between 7 and 12 months reported fewer hospitalisations of their infant.

This study also adds new understandings of how workplaces support breastfeeding, and how specifically accommodating the physiological needs of breastfeeding employees benefits employers as well as families. A comparative strength of our study is the relatively large and diverse sample of employees who initiated breastfeeding and returned to work within the first 12 months. Data for mothers returning in the first six months show that flexibility in start and finish times, work hours and timing of breaks to accommodate the employee expressing milk or breastfeeding are particularly important for exclusive breastfeeding. Workplace attitudes and job security also mattered: mothers who perceived they could lose their job for breastfeeding were less likely to exclusively breastfeed at six months.

Workplaces that have been accredited as being breastfeeding-friendly are overrepresented in workplaces from which the sample employees were recruited. Further analysis is needed to evaluate whether the findings reflect selection factors that influence employees' responses regarding infant feeding practices and workplace support. Our findings regarding infant health consequences for absenteeism are important, and corroborate the results of a previous small-scale study (Cohen et al., 1995). We found lower absenteeism among employees who exclusively breastfed for six months. However, our study was not sufficiently powered to reliably identify differences in the incidence of infant illness between feeding groups; there remains a need for analysis using larger, representative datasets of employed women and their infants that collect more comprehensive health data, as well as information on infant feeding status.

It is important to note that the infants in this sample were all initially breastfed, and our comparison is with exclusive breastfeeding at six months compared with not-exclusive breastfeeding at six months. Some of the latter group will be partially breastfeeding at six months; hence the outcomes are a conservative reflection of the difference between exclusively breastfed infants and those who are fully weaned from breastfeeding.

It should also be noted that "reverse causation" may explain the relationships between infant ill health and exclusively breastfeeding at six months, where poor infant health may be a cause of not establishing or maintaining exclusive breastfeeding. For example this could occur if breastfeeding was disrupted by infant disability or illness, resulting in early hospitalisation. Likewise, it has been suggested in the United States that breastfeeding mothers may differ from not breastfeeding mothers in their propensity to take their ill child to hospital (Bauchner, Leventhal, & Shapiro, 1986; Kovar, Serdula, Marks, & Fraser, 1984), though it is not clear if this applies in the Australian setting.

A study limitation is that the organisations from which the mothers were recruited self-selected into the study. It is likely that these organisations over-represent organisations that attend to human resource management and work and family balance issues. Their employees also self-selected into the survey, so may not be fully representative of all employed new mothers, and may also cluster within the sampling units. However, it is difficult to recruit employees within organisations as was necessary for this study.

Conclusion

This paper has used quantitative and qualitative data from 304 employed new mothers drawn from 62 different workplaces to explore and assess the relationship between exclusive breastfeeding and workplace support or job quality factors, which address key barriers to breastfeeding. It has also examined health and productivity implications of exclusive breastfeeding for infants and mothers who return to work in the first post-natal 12 months.

The analyses showed that most female employees with infants required various time accommodations, including part-time and adjustable hours and lactation breaks, in order to maintain exclusive breastfeeding to six months. Extending paid parental leave to 26 weeks would help redress this tension between employment commitments and breastfeeding.

As well as part-time work opportunities and flexibility in start and finish times, specific workplace accommodations for breastfeeding are also linked to women being able to maintain exclusive breastfeeding to six months. In this regard, the 2011 amendments to federal discrimination legislation regarding breastfeeding are of considerable potential importance, and their application in workplaces as well as child care should be monitored.

Finally the analysis shows potential links between exclusively breastfeeding and reduced absenteeism, suggesting that employers as well as the health system and families may benefit from specific workplace accommodation of the needs of breastfeeding employees. Breastfeeding-friendly workplace policy initiatives could therefore be cost-effective for employers as well as governments, and may support an earlier return from maternity leave by some employees.

Endnotes

1 Laws regarding discrimination on the grounds of breastfeeding previously varied between states. In some states, breastfeeding was specifically included as grounds for discrimination in employment while in others, such as Queensland, discrimination on the grounds of breastfeeding was only prohibited for the goods and services area, not for work and work-related areas.

2 Ethics approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Australian National University (ANU Human Ethics Protocol 2010/159, 22/04/2010).

3 Analysis was undertaken using SPSS Statistics version 19. Analyses did not take account of the clustering of individual employees within workplaces.

References

- Australian Health Ministers' Conference. (2009). Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy 2010-2015. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2011). 2010 Australian National Infant Feeding Survey: Indicator results. Canberra: AIHW.

- Baker, M., & Milligan, K. (2008). Maternal employment, breastfeeding, and health: Evidence from maternity leave mandates. Journal of Health Economics, 27(4), 871-887.

- Bar-Yam, N. B. (1998a). Workplace lactation support: Part I. A return-to-work breastfeeding assessment tool. Journal of Human Lactation, 14(3), 249-254. doi:10.1177/089033449801400319

- Bar-Yam, N. B. (1998b). Workplace lactation support: Part II. Working with the Workplace. J Hum Lact, 14(4), 321-325. doi:10.1177/089033449801400424

- Bartick, M., & Reinhold, A. (2010). The burden of suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: A pediatric cost analysis. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1048-1056.

- Bauchner, H., Leventhal, J. M., & Shapiro, E. D. (1986). Studies of breast-feeding and infections. How good is the evidence? Jama, 256(7), 887-892.

- Baxter, J. (2008). Breastfeeding, employment and leave: An analysis of mothers in Growing Up in Australia. Family Matters, 80, 17-26.

- Baxter, J. (2013). Parents working out work (Australian Family Trends No. 1). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Baxter, J., Cooklin, A., & Smith, J. P. (2009). Which mothers wean their babies prematurely from full breastfeeding? An Australian cohort study. Acta Paediatrica, 98, 1274-1277.

- Berger, L. M., Hill, J., & Waldfogel, J. (2005). Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the US. Economic Journal, 115(501), F29-47.

- Broderick, E. (2012). Women in the workplace. Australian Economic Review, 45(2), 204-210.

- Brodribb, W. (Ed.) (2012). Breastfeeding management in Australia (4th ed.). East Malvern, Vic.: Australian Breastfeeding Association.

- Büchner, F. L., Hoekstra, J., & van Rossum, C. T. M. (2007). Health gain and economic evaluation of breastfeeding policies: Model simulation (RIVM Report No. 350040002/2007). Bilthoven, Netherlands: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu.

- Chatterji, P., & Frick, K. (2003). Does returning to work after childbirth affect breastfeeding practices? Review of the Economics of the Household, 3(3), 315-335.

- Cohen, R., Mrtek, M. B., & Mrtek, R. G. (1995). Comparison of maternal absenteeism and infant illness rates among breastfeeding and formula feeding women in two corporations. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(2), 148-153.

- Cooklin, A. R., Donath, S. M., & Amir, L. H. (2008). Maternal employment and breastfeeding: Results from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Acta Paediatr, 97(5), 620-623.

- Dabritz, H. A., Hinton, B. G., & Babb, J. (2009). Evaluation of lactation support in the workplace or school environment on 6-month breastfeeding outcomes in Yolo County, California. Journal of Human Lactation, 25(2), 182-193. doi:10.1177/0890334408328222

- Earle, J. (2002). Family-friendly workplaces. Family matters, 61, 12-17.

- Eldridge, S., & Croker, A. (2005). Breastfeeding friendly workplace accreditation: Creating supportive workplaces for breastfeeding women. Breastfeeding Review, 13(2), 17-22.

- European Commission Directorate Public Health and Risk Assessment. (2008). EU Project on Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe: Protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding in Europe. A blueprint for action (revised). Luxembourg: European Commission Directorate Public Health and Risk Assessment.

- Fair Work Australia. (2009). Fair Work Act 2009. Retrieved from <www.fwc.gov.au/index.cfm?pagename=legislationfwact>.

- Fein, S. B., & Roe, B. (1998). The effect of work status on initiation and duration of breast-feeding. American Journal of Public Health, 88(7), 1042-1046.

- Gielen, A. C., Faden, R. R., O'Campo, P., Brown, C. H., & Paige, D. M. (1991). Maternal employment during the early postpartum period: Effects on initiation and continuation of breast-feeding. Pediatrics, 87(3), 298-305.

- Grovslien, A. H., & Gronn, M. (2009). Donor milk banking and breastfeeding in Norway. Journal of Human Lactation, 25(2), 206-210.

- Guendelman, S., Kosa, J. L., Pearl, M., Graham, S., Goodman, J., & Kharrazi, M. (2009). Juggling work and breastfeeding: Effects of maternity leave and occupational characteristics. Pediatrics, 123(1), e38-46. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2244

- Hawkins, S. S., Griffiths, L. J., & Dezateux, C. (2007). The impact of maternal employment on breast-feeding duration in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Public Health Nutrition, 10(9), 891-896.

- Heinig, M. J. (2007). Using organizational theory to promote breastfeeding accommodation in the workplace. Journal of Human Lactation, 23(2), 141-142.

- Horta, B. L., Bahl, R., Martinez, J. C., & Victora, C. G. (2007). Evidence on the long term effects of breastfeeding: Systematic review and meta analyses. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Horton, B. (1995). The needs of breastfeeding mothers in the paid workforce: A literature review. Canberra: Nursing Mothers' Association of Australia and Department of Industrial Relations.

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Aging. (2007). The best start: Report on the Inquiry Into the Health Benefits of Breastfeeding. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. (1999). Pregnant and productive: It's a right not a privilege to work while pregnant. Report of the National Pregnancy and Work Inquiry. Sydney: HREOC.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. (2011). Federal discrimination law 2011. Canberra: HREOC. Retrieved from <www.hreoc.gov.au/legal/FDL/index.html>.

- International Labour Organization. (2000). C183 Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183): Convention concerning the revision of the Maternity Protection Convention (revised), 1952 (entry into force: 07 Feb 2002). Geneva: ILO. Retrieved from <www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C183>.

- Ip, S., Chung, M. Raman, G., Chew, P., Magula, N., DeVine, D. et al. (2007). Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries (Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 153). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved from <www.breastfeedingmadesimple.com/ahrq_bf_mat_inf_health.pdf>.

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L. et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959-976.

- Kovar, M. G., Serdula, M. K., Marks, J. S., & Fraser, D. W. (1984). Review of the epidemiologic evidence for an association between infant feeding and infant health. Pediatrics, 74(4, Pt 2), 615-638.

- Kramer, M. S., Aboud, F., Mironova, E., Vanilovich, I., Platt, R. W., Matush, L et al. (2008). Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: New evidence from a large randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 578-584.

- Kurinij, N, S. P., Ezrine, S. F., Rhoads, G. G. (1989). Does maternal employment affect breast-feeding? American Journal of Public Health, 79, 1247-1250.

- Lindberg, L. (1996). Trends in the relationship between breastfeeding and postpartum employment in the United States. Social Biology, 43(3-4), 191-202.

- Mandal, B., Roe, B. E., & Fein, S. B. (2012). Work and breastfeeding decisions are jointly determined for higher socioeconomic status US mothers. Review of Economics of the Household, 28 July, 1-21. doi:10.1007/s11150-012-9152-y

- McIntyre, E., Pisaniello, D., Gun, R., Sanders, C., & Frith, D. (2002). Balancing breastfeeding and paid employment: A project targeting employers, women and workplaces. Health Promotion International, 17(3), 215-222. doi:10.1093/heapro/17.3.215

- National Breastfeeding Advisory Committee of New Zealand. (2009). National Strategic Plan of Action for Breastfeeding 2008-2012: National Breastfeeding Advisory Committee of New Zealand's advice to the Director-General of Health. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2003). Dietary guidelines for children and adolescents in Australia incorporating the Infant Feeding Guidelines for Health Workers. Canberra: NHMRC.

- Nursing Mothers' Association of Australia, & Department of Industrial Relations. (1995). Workplace guidelines to support breastfeeding mothers in the workplace. Canberra: Department of Industrial Relations.

- Productivity Commission. (2009). Paid parental leave: Support for parents with newborn children. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Renda, J., Baxter, J., & Alexander, M. (2009). Exploring the work-family policies mothers say would help after the birth of a child. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 12(1), 65-87.

- Renfrew, M. J., Pokhrel, S., Quigley, M., McCormick, F., Fox-Rushby, J., Dodds, R. et al. (2012). Preventing disease and saving resources: The potential contribution of increasing breastfeeding rates in the UK. London: UNICEF UK.

- Roe, B., Whittington, L. A., Fein, S. B., & Teisl, M. F. (1999). Is there competition between breast-feeding and maternal employment? Demography, 36(2), 157-171.

- Ryan, A. S., Zhou, W., & Arensberg, M. B. (2005). The effect of employment status on breastfeeding in the United States. Women's Health Issues, 16(5), 243-251.

- Smith, J. P., & Forrester, R. (2013). Who pays for the health benefits of exclusive breastfeeding? An analysis of maternal time costs. Journal of Human Lactation, 29(4), 547-555. doi:10.1177/0890334413495450

- Smith, J. P., & Harvey, P. J. (2011). Chronic disease and infant nutrition: Is it significant to public health? Public Health Nutrition, 14(02), 279-289. doi:10.1017/S1368980010001953

- Smith, J. P., Javanparast, S., McIntyre, E., Craig, L., Mortensen, K., & Koh, C. (2013). Discrimination against breastfeeding mothers in childcare. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 16(1), 65-90.

- Smith, J. P., Thompson, J. F., & Ellwood, D. A. (2002). Hospital system costs of artificial infant feeding: Estimates for the Australian Capital Territory. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 26(6), 543-551.

- Strazdins, L., Shipley, M., Clements, M., Obrien, L. V., & Broom, D. H. (2010). Job quality and inequality: Parents' jobs and children's emotional and behavioural difficulties. Social Science and Medicine, 70(12), 2052-2060.

- Thulier, D., & Mercer, J. (2009). Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 38(3), 259-268.

- Toohey, T., Colosimo, D., & Boak, A. (2009). Australia's hidden resource: The economic case for increasing female participation. Melbourne: Goldman Sachs JBWere.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2011). The Surgeon General's call to action to support breastfeeding. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General.

- Visness, C. M., & Kennedy, K. I. (1997). Maternal employment and breast-feeding: Findings from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 87(6), 945-950.

- World Health Organization. (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: WHO.

- Winicoff, B., & Castle, M. A. (1988). The influence of maternal employment on infant feeding. In B. Winicoff, M. A. Castle, & V. H. Laukaran (Eds.), Feeding infants in four societies: Causes and consequences of mothers' choices (pp. 121-145). New York: Population Council/Greenwood Press.

Appendix

| % of all workplaces ( n = 64) | |

|---|---|

| Size | |

| Small (< 20 staff) | 13 |

| Medium (20-200 staff) | 39 |

| Large (> 200 staff) | 48 |

| Ownership | |

| Public | 43 |

| Private | 57 |

| Industry | |

| Government administration and defence | 30 |

| Education, health and community services | 28 |

| Property and business services | 14 |

| Finance and insurance | 11 |

| Communication, electricity, gas and water supply | 6 |

| Manufacturing | 6 |

| Cultural and recreational services | 5 |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Returned by 6 months (%) ( n = 92) | Returned at 7-12 months (%) ( n = 181) | Returned at 13-24 months (%) ( n = 31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age groups | |||

| <= 29 years | 19 | 15 | 7 |

| 30-34 years | 50 | 49 | 45 |

| 35-39 years | 24 | 28 | 36 |

| = 40 years >= 40 years | 7 | 7 | 13 |

| Mother's education post-secondary | 77 | 77 | 77 |

| Family income | |||

| <= $599 weekly ($31,199 p. a.) | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| $600-999 weekly ($31,200-51,999 p. a.) | 7 | 5 | 3 |

| $1000-1,499 weekly ($52,000-77,999 p. a.) | 23 | 9 | 14 |

| $1,500-2,199 weekly ($78,000-114,399 p. a.) | 29 | 38 | 24 |

| = $2,200 weekly (>= $114,400 p. a.) >= $2,200 weekly (>= $114,400 p. a.) | 36 | 47 | 59 |

| Maternal occupation | |||

| Manager/professional | 66 | 63 | 58 |

| Clerical/administrative, community/personal services, sales workers | 34 | 37 | 42 |

Smith, J. P., McIntyre, E., Craig, L., Javanparast, S., Strazdins, L., & Mortensen, K. (2013). Workplace support, breastfeeding and health. Family Matters, 93, 58-73.