"I expect my baby to grow up to be a responsible and caring citizen"

What are expectant parents' hopes, dreams and expectations for their unborn children?

October 2014

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

This article explores the hopes and dreams of expectant parents in New Zealand. It presents findings from a sub-sample of 1,000 pregnant women and 644 partners in the Growing Up in New Zealand longitudinal study, on parents' early hopes, dreams, and expectations for their unborn children. Overall, the parents' hopes and expectations were overwhelmingly positive and fitted well within the six levels of Maslow's hierarchy of needs. The most predominant needs were both the lower level "physiological" needs and the higher level "self-actualisation" needs, suggesting that both the basic physical necessities of life and their child's ability to be able to fulfil his or her individual potential were particularly important. This qualitative exploration lays important groundwork for future analyses and insights into the changing hopes and dreams of New Zealand parents for their children over time.

Even before a child is born, parents have hopes, dreams and expectations for their child. These are shaped by the parents' beliefs, morals, rules, values and ways of thinking, which are transmitted to children through their parents' behaviour toward them, shaping the child's development and future in potentially important ways (Edwards, Knoche, Aukrust, Kumru, & Kim, 2006; Suizzo, 2007; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2007). For example, children whose parents have high educational expectations tend to demonstrate better academic performance at all ages (Benner & Mistry, 2007; Kaplan, Liu, & Kaplan, 2001), stay at school longer (Choy, Horn, Nuez, & Chen, 2000; Ensminger & Slusarcick, 1992), be more engaged with learning, and have high educational aspirations themselves (Choy et al., 2000; Jacobs & Harvey, 2005).

Cultural differences in parental beliefs have been explored. For example, collectivist cultures often place more value on relating well to others, fitting in and interdependence, whereas individualist cultures place more emphasis on independence and expressions of uniqueness (Gambrel & Cianci, 2003; Hofstede, 1984; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Shek & Chan, 1999; Suizzo, 2007; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2007).

Many approaches have been used to understand parents' hopes, dreams and expectations for their children. Most of the research has focused on quite specific domains of interest, such as parental aspirations for their child's academic success (e.g., Jacobs & Harvey, 2005), values (e.g., Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Tudge, Hogan, Snezhkova, Kulakova, & Etz, 2000), morals (e.g., Reese, Balzano, Gallimore, & Goldenberg, 1995), the characteristics of an "ideal child" (e.g., Paguio, Skeen, & Robinson, 1989), or how to parent (e.g., Chan & Koo, 2011).

Other researchers have taken a more theoretically driven approach (e.g., Burton, 1990; Edwards et al., 2006; Maslow, 1943; Max-Neef, Elizalde, & Hopenhayn, 1991; Rosenberg, 2003). Probably the most well-known work on human needs or requirements for the optimal development of individuals is that of Abraham Maslow (1943), who identified five basic needs for well-adjusted individuals. These needs are typically understood to be hierarchical, with lower, more basic needs (physiological, safety, and belonging) having to be at least relatively satisfied before the higher needs (self-esteem and self-actualisation) can be acquired or activated (Feist & Feist, 2006). Although the ordering of Maslow's "needs" has been criticised, in part due to variations across cultures, the values themselves are argued to be relatively universal (Gambrel & Cianci, 2003; Hofstede, 1984; Tay & Diener, 2011).

Beliefs about what children require to develop into thriving individuals and citizens are evident within families, cultures, theory and policy. However, to date, researchers have not often asked parents to freely state what they perceive their hopes, dreams and expectations for their children to be, and this question has certainly not been asked before their children are born. Given the potentially self-fulfilling nature of parental wishes for their children (e.g., Fan & Chen, 2001; Tudge et al., 2000; Wood, Kaplan, & McLoyd, 2007), it is important to document these beliefs as early in the child's life as possible, in order to be able to subsequently explore whether and how these beliefs play out and the extent to which they change.

Method

Participants

A random sub-sample of 15% of the pregnant women enrolled in Growing Up in New Zealand was selected for this analysis (Morton et al., 2012). Where the women had partners enrolled in the study (almost always identified as the baby's biological father), their data were also included. This procedure resulted in a sub-sample of 1,013 pregnant women and 648 partners. Thirteen women and four partners had not responded to the relevant question and were excluded, giving a final sub-sample of 1,000 mothers and 644 partners (see Table 1 for demographic information).

| Mother | Partner | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Age groups (years) | ||||

| < 20 years | 59 | 5.9 | 14 | 2.2 |

| 20-29 years | 383 | 38.3 | 169 | 26.2 |

| 30-39 years | 503 | 50.3 | 363 | 56.4 |

| 40+ years | 55 | 5.5 | 98 | 15.2 |

| Self-prioritised ethnicitya | ||||

| European | 546 | 54.7 | 384 | 59.7 |

| Māori | 139 | 13.9 | 57 | 8.9 |

| Pacific Peoples | 125 | 12.5 | 72 | 11.2 |

| Asian | 156 | 15.6 | 98 | 15.2 |

| New Zealander | 10 | 1.0 | 15 | 2.3 |

| Other | 23 | 2.3 | 17 | 2.7 |

| Planned/unplanned pregnancy | ||||

| Planned | 574 | 57.7 | NA | |

| Unplanned | 421 | 42.3 | ||

| Child birth order | ||||

| First child | 438 | 43.8 | NA | |

| Subsequent child | 561 | 56.2 | ||

| Education | ||||

| No secondary education | 66 | 6.6 | 44 | 6.8 |

| Secondary education | 218 | 21.9 | 134 | 20.8 |

| Tertiary education | 715 | 71.6 | 466 | 72.4 |

| Household income | ||||

| Low (< $70,001) | 515 | 51.5 | 260 | 40.4 |

| Medium ($70,001-100,000) | 181 | 18.1 | 125 | 19.4 |

| High (> $100,000) | 304 | 30.4 | 259 | 40.2 |

| Household New Zealand Deprivation Index 2006 b | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 174 | 17.4 | 130 | 20.2 |

| Quintile 2 | 171 | 17.1 | 121 | 18.8 |

| Quintile 3 | 176 | 17.6 | 116 | 18.0 |

| Quintile 4 | 222 | 22.2 | 143 | 22.2 |

| Quintile 5 | 257 | 25.7 | 134 | 20.8 |

| Total number of observations | 1,000 | 644 | ||

Notes: Where the stated frequencies do not sum to the total number of women or partners in the sample, this is due to missing data. a Parents were asked to identify their own ethnicity or ethnicities at the most detailed level possible (commonly Level 3 Statistics New Zealand hierarchy [Statistics New Zealand, 2005]) and they were then asked to identify their main (self-prioritised) ethnic group. For Table 1 this has been coded at Level 1, with the New Zealander category also included. Level 1 "European" includes New Zealand European. b The New Zealand Deprivation Index combines nine socio-economic variables from the 2006 Census, capturing eight dimensions of deprivation at the small area level. In this table the original deprivation scores (measured in deciles) have been collapsed into quintiles, each quintile is the sum of two sequential deciles, so deciles 1 and 2 form quintile 1, deciles 3 and 4 form quintile 2, etc. Decile 1 represents the least deprived geographic areas and 10 represents the most deprived areas (Salmond, Crampton, & Atkinson, 2007).

Procedure

At the end of a 90-minute antenatal maternal interview and a 45-minute antenatal partner interview, both the pregnant women and their partners were separately and independently asked an open-ended question: "Please give us one or two sentences about the hopes, dreams and expectations you have for your baby". Interviewers entered the respondents' responses verbatim into a laptop computer, and were instructed not to probe beyond asking the above question.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis approach was used (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Initially, the data were analysed inductively (allowing the content of the data to direct the coding and theme development), and then deductively, using existing concepts or ideas to shape analysis.

Initial free coding

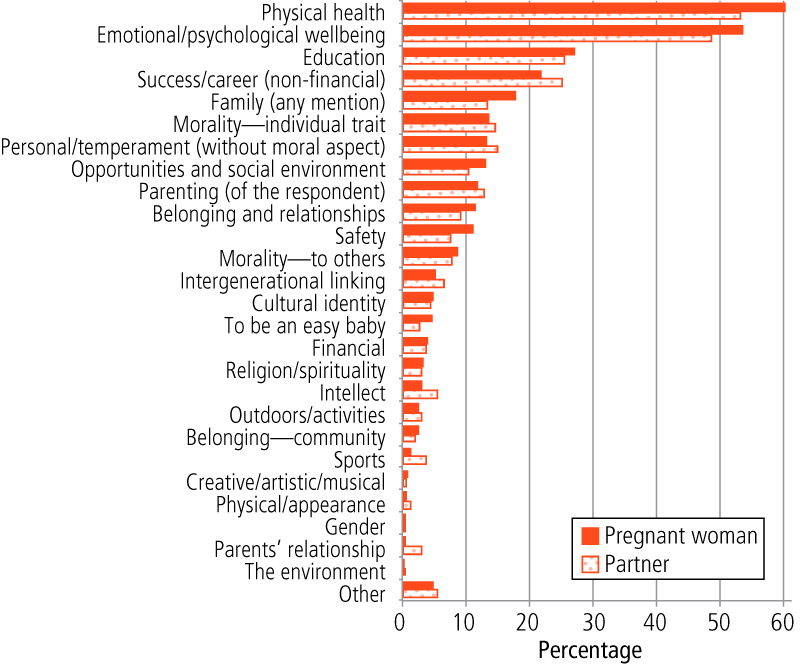

The full dataset of parental hopes, dreams and expectations was read. The first three authors then worked with randomly selected responses from 100 women and 100 partners to develop a coding scheme. Twenty-seven codes were inductively generated (Figure 1). Ten per cent of the data were then independently coded in order to establish reliability of at least 80% between each pair of coders. Once achieved, the second author coded the remainder of the sub-sample.

Figure 1: Percentage of pregnant women and partner responses according to initial inductive codes

Each parental statement was broken into idea units. An idea unit was a single statement (e.g., belief, desire, thought) that could be meaningfully coded into one category. Individual categories were only allocated once to each idea unit. Figure 1 shows response percentages alignment between the pregnant women and their partners for the 27 inducted codes.

The inductive process was used to get an initial understanding of the respondents' views, but many of the categories had too little data to allow for meaningful subsequent analysis using multiple respondent characteristics. Therefore, other frameworks were considered to allow deductive coding with fewer categories. Maslow's widely used hierarchy of needs framework fit best with the existing 27 codes, in contrast to other frameworks such as Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Model (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Only four of the original inductive categories - To be an easy baby, Gender, Intergenerational linking, and Other - all of which contained little data, were excluded from this analysis due to poor fit with Maslow's hierarchy.

Coding with Maslow's hierarchy of needs

To develop this coding scheme, we used Maslow's (1943) five-tiered hierarchy and Koltko-Rivera's (2006) review of Maslow, which importantly adds the category of Self-transcendence that Maslow later developed to account for individuals who "identify with something greater than the purely individual self" (Koltko-Rivera, 2006, p. 306). Introducing this sixth tier allowed for better accommodation of responses such as "hoping that the child would have a religious or spiritual dimension to their lives".

In addition, Gorman's use of Koltko-Rivera's work (Gorman, 2010) provided a useful template for further understanding Maslow's schema. Table 2 shows how Koltko-Rivera's and Gorman's descriptions map on to Maslow's original explanations.

| Maslow (1943) | Koltko-Rivera (2006) | Gorman (2010) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological | Bodily needs | Basic necessities of life | Survival needs met, confident they will continue to be met |

| Safety needs | Predictable, orderly and organised world, justice, protection, financial and employment security | Security through order and law | Feels safe, and confident they will not be harmed |

| Belongingness and love needs | Affection, a place in a group, both giving and receiving love | Affiliation with a group | Is confident in their relationships/ability to form caring relationships. Is able to identify with a group or groups |

| Esteem needs | Self-respect/self-esteem, achievement, confidence, independence/freedom, esteem and respect of others, reputation and prestige | Esteem through recognition or achievement | Has realistic positive opinions of themselves and their ability to gain respect and recognition from others |

| Self-actualisation | Doing what they were fitted for, self-fulfilment, realising potential | Fulfilment of personal potential | Has a sense of their ability to achieve further goals and a sense of what they want to strive for |

| Self-transcendence a | Furthering a cause beyond the self and experiencing communion beyond boundaries of the self through a peak experience | Is concerned about others and strives to contribute to the good of the community either locally or globally |

Notes: a The self-transcendence category was added to Maslow's 1943 five-tiered model after a review of Maslow's work by Koltko-Rivera in 2006. This review took into account later works by Maslow where he describes individuals who "identify with something greater than the purely individual self" (Koltko-Rivera, 2006, p. 306).

As with the initial coding, each statement was broken down into idea units and each unit assigned to one of Maslow's categories, with a code being applied only once to each statement. Ten per cent of the sub-sample was then independently coded into the six Maslow categories, and a seventh Other category was used for data that did not fit. All idea units were assessed on the basis of the context in which they were mentioned. Once 80% reliability was reached across all three coders, one author then coded the remainder of the sub-sample. Consensus among all coders on disagreements was reached through discussion.

Results and discussion

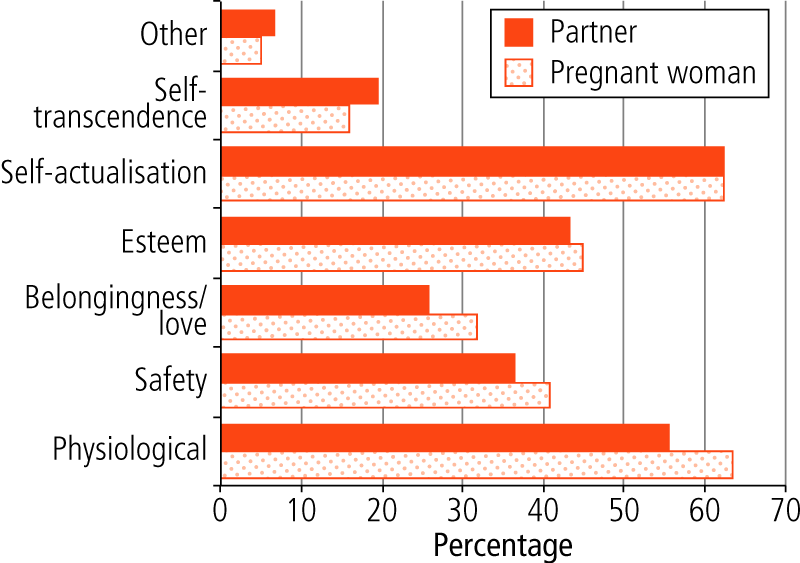

Figure 2 shows the proportion of pregnant women and partners who commented on each of the Maslow categories. Both parents prioritised these categories in much the same way. The most notable differences were in the likelihood of commenting on the physiological tier (64% women vs 56% partners) and on belongingness/love (32% women vs 26% partners).

Figure 2: Percentage of pregnant women and partner responses according to Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Fit with Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Physiological

The physiological category was one of the two most prevalent categories mentioned across the sample, and the most prevalent for the pregnant women. The most common statement in this category was simply a hope that the child be "healthy". In some instances, this was more detailed; for example, "no developmental concerns"; that they "grow old"; the hope that "she has ten fingers and ten toes"; or that the baby will "eat and sleep and grow well". This category may have been more commonly mentioned by prospective mothers due to the mental and physical investment pregnant women have in supporting their unborn child. The focus on physical health across a large proportion of our sample stands in contrast to LeVine's (1988) suggestion that a focus on the physical health of a child is more common in non-industrialised societies. Our result may be because we asked during pregnancy, when the manifestation of the child is almost exclusively physical. Parental concerns and their hopes and dreams may change once the child is born, something that Growing Up in New Zealand has the capacity to assess.

We also included within the physiological category responses desiring that the child be active or spend time outdoors; for example, "a love for the outdoors"; that they grow up "healthy in a natural place and doing a lot of outdoor activities"; or that they "be active in sports". At times this was mentioned specifically in relation to New Zealand; for example, to have "access to the more outdoor lifestyle in New Zealand".

A few parents described their child's health as something they were responsible for as parents, either once the child was born: "I would like to raise healthy, confident and successful children"; or because of something the parent had already done: "I hope that my baby is healthy - because of my smoking - I have had a hard time dealing with that".

Safety

Parenthood is associated with increased concern about dangers and heightened awareness of risks in the environment, especially for first-time parents (Eibach, Libby, & Gilovich, 2003). A large proportion of the parents who mentioned safety did so in general terms, wanting the child "to be safe" or to have a "safe environment". Some were more specific, many wishing that their child live in a safe community or neighbourhood, home or house ("To be brought up in a safe community like this - that was the reason we moved here"; "That we are able to provide him with a safe home"), while others broadened their scope to a safe country or world. For other parents, the wish for safety was articulated in relation to aspects of the child, not the environment; for example, that the child not be discriminated against ("I don't want him/her to be disadvantaged because of his/her race"). Others wished that their child be safe from specific forms of violence: "I don't want to have violence in the family"; for their child to "not be picked on or anything like that".

Safety also often encompassed the hope that the child have their needs met ("to live comfortably and not to struggle"); that they be financially secure ("to be financially better than what I am doing"); and that they have the employment necessary to ensure material security ("get a good education, get a good job, own his own home"). Related to this was the notion of the child having a "fortunate life", expressed in comments like: "I would like this baby to have everything". In some instances, this was articulated as a comparison with the parent's life, whether it should be similar ("I hope they will have the same upbringing I had, i.e., safe, tightknit family values, safety and security, access to good education, interest in sports, and a really good Kiwi upbringing, not dominated by the Internet"); or different, in that the child's life should be more fortunate than the parent's ("I hope he has a better childhood than I had"); or that the child would make better life choices than the parent ("I don't want her to make the same mistakes I did").

In other cases, hopes for the child to have a specific type of childhood seemed to be couched in the parent's underlying wish to be a "good" parent, and hence able to support and nurture the child and provide them with "safe" parenting. They wanted to be supportive parents (hoping to "be able to support them both emotionally, physically and financially"); to have time for their child (hoping "I could have the time to spend with my child and as a family"); to provide the child with a good foundation for the rest of their lives ("I hope to provide them with all the opportunities they need to be the best person they can be and to instil in them values and tools for their journey in life"); or to provide better parenting than they received ("I'm looking forward to being a mum and spending time with him and being a better parent than I had"). The hope to be a "good" parent was also often articulated as the wish to be able to provide for their child. As well as hoping to be supportive parents, they also expressed the desire that their child be supported by others, either specific people (to receive "love and support, as I have had, from family and friends") or, less often, in a wider social sense (that the child is "supported throughout its life").

Belongingness/love

Frequently mentioned in this category were hopes that children feel part of the family, get on with their siblings, and feel loved in a general sense (that the child "be loved", be a "loving" person, or grow up in a "loving environment"). Love was also mentioned specifically in relation to the parents themselves ("to also know that her parents love her and that her parents will always be there for her when she needs them"). Personal connectedness was also expressed in the desire that the child be friendly or have good friends (to "get on well with his friends"; to "have lots of mates and be outgoing"). At times, the desire for the child to have relationships with others extended to both family and friends (to "grow up feeling loved, nurtured, encouraged and inspired by an extended network of family and friends"). Overall, more pregnant women than partners mentioned the belongingness/love category.

Based on previous cross-cultural research, we also expected that the ways in which respondents talked about being part of a family would vary by cultural background. That is, within collectivist cultures, family generally constitutes the fundamental unit of belongingness, especially within East Asian, Pacific and Māori cultures (Durie, 1998; Ngan-Woo, 1985; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2007). In Growing Up in New Zealand, participants were asked to list all their ethnicities and then to specify the one with which they most identify. We used this "self-prioritised ethnicity" as a proxy for the cultural background to which the participant was most likely to be affiliated.

The desire that children adhere to group norms by respecting their parents or families (e.g., a Pacific woman commented: "I hope that she is respectful to her parents") was predominantly expressed by those who self-prioritised within Level 1 Asian and Pacific ethnicities; to a lesser extent, Māori parents; and notably less so by those who primarily identified as European or New Zealander. Similarly, the wish that their offspring should care for them when they were older was more commonly expressed by Asian parents (e.g., "He should look after us when he grows up, and support us"); to a lesser extent by Pacific women; and rarely by European, New Zealander, or Māori parents.

We understood belongingness to include a desire that the child be part of an ethnic or cultural group. Piontkowski, Florack, Hoelker, and Obdrzálek (2000) noted that the more individuals have a sense of belonging and identity with a particular cultural group, the more likely they are to see that culture as an important and distinct part of who they are, and to strive to protect that distinctive social identity. We found that parents who prioritised their ethnic identity as Māori, Pacific or Asian were more likely to talk about the child's cultural belonging; for example, "to keep our own culture while in New Zealand" (Asian woman); or "I expect him to grow up with a strong cultural background" (Pacific woman). Some Māori parents specifically focused on culture in relation to language; for example, "my main goal is for my child to be a fluent Māori speaker" (Māori partner). In some instances, those who mentioned culture were part of the groups who primarily identified as New Zealander or European. These individuals specifically mentioned non-New Zealand cultures, while sometimes also simultaneously expressing the desire for their child to feel part of New Zealand culture; for example, "I want her to feel that New Zealand is her home, but still to remember the Romanian culture".

Within our sub-sample, church membership (as opposed to religion, which was coded as part of self-transcendence) was exclusively mentioned in relation to belonging by pregnant Pacific women (although it was not mentioned by any of the Pacific partners), a finding which likely relates to the relative centrality of religion to Pacific cultures within New Zealand (Bedford & Didham, 2001).

Esteem

This category was most commonly mentioned in relation to education. These comments were very general, hoping the child would have a "good education" or "do well in school". Very few parents mentioned a specific level of education; if they did, it was just to finish school, rather than specifying tertiary/higher education. Some parents also mentioned education in a functional sense ("good health and good education, because I think when you have those two, you can achieve anything else"; "that they achieve at school, because I know that helps with money and work"). Only a very few parents explicitly talked about education as an integral good; for example, wanting their child to "know that education is important".

The predominance of education-related comments in the esteem category is relevant given the importance of early success or failure at school for the development of an individual's belief about their capabilities (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 2001; Pajares & Schunk, 2002).

Within this category, we also included the desire for the child to have attributes that would indicate self-esteem or self-respect: independence ("I would like him to stand on his own two feet and to be a responsible man and independent"); confidence ("to be confident in what he wants to be when he grows up, and not to be pushed around by other people"); non-physical strength ("I hope that she will grow into a strong independent woman and accomplish her dreams"); self-esteem ("she needs to be proud of who she is"); and the general wish that the child can "be themselves" or be "true" to themselves. We also included the desire for characteristics that would lead them to gain the esteem of others, including that they be well-behaved ("I hope it is quiet, well-behaved and healthy"; "that she is a good little girl and is active and not shy or naughty") or law-abiding; that they be a "good person"; that they be a conscientious employee ("I want him to be a hard worker"); that they be "well rounded"; and that they be physically attractive ("I hope that she has lots of hair like mine, curly"; "has its mum's nose"). These esteem characteristics also included being talented, either generally ("I want my child to find and know what their talents and giftings are and use those"), or more specifically, such as in sports ("that they are an All Black - no pressure!")1 or music ("I want to make the baby an Indian singer if they have the God-gifted quality"). Finally, this category also included the more general desire that the child be successful ("for him to become someone"), or that they become "a leader".

Self-actualisation

The most commonly mentioned aspect within this category was that the child be happy. Usually this was expressed in a very general sense ("I just hope that she is going to be healthy and happy"), but sometimes it was expanded on in particular ways; for example, "that they will do something meaningful and productive with their life that makes them happy". Related to this was the desire that the child enjoy life ("hope she enjoys life while she can"), and that they have a "good life" or a "good future" in a non-specific sense. These findings align with research on students in 42 countries who reported that happiness and life satisfaction were very important to them, with students from Westernised countries assigning happiness to be of greater importance. This prominence is suggested because as people fulfil their basic material needs, their happiness and subjective wellbeing become increasingly important (Diener, 2000).

The next most commonly mentioned wish in this category was that the child have opportunities, either provided by the parents ("I hope to provide them with all the opportunities they need to be the best person that they can be"), or in a more general sense ("I want my son to have the opportunity to do whatever he wants and not to struggle"; "that it has the best opportunities that life can offer"). The hope that the child should be able to utilise these opportunities was mentioned by a few; for example, "that she takes as many opportunities as she is given to experience the great things in her life". Related to this was the hope that children try their best ("I want her to achieve her goals and strive for what she wants"; "for her to never give up on anything"), and actively follow their dreams ("hopefully she will go for her dreams and let nothing stop her").

We also included in this category, dependent on context, parents' wishes that their children have good jobs or careers. While most references to future employment were coded in the safety category, on the basis that they referred to financial security, in some instances it was clear that the respondent was talking about a career as being rewarding in a personal rather than a remunerative sense ("that they end up doing a career that they love").

Self-transcendence

Building on Maslow, Koltko-Rivera (2006) defined self-transcendence in two ways: to further a cause beyond the self, and to experience a "communion" beyond the self, sometimes through a "peak experience" (p. 303). We understood Koltko-Rivera's definition to have a spiritual aspect to it, and to include religious aspects when these were of a spiritual nature (rather than membership of a church); for example, "that he will be raised as a Catholic and keep the faith"; "I want her to be a godly woman and to love God is the most important thing". Within this category, the likelihood of mentioning self-transcendence as related to a religious experience was again patterned on the basis of self-prioritised ethnicity, with Pacific women considerably more likely than any other group to mention this category in relation to spirituality.

Gorman (2010) expanded on Koltko-Rivera's first definition by suggesting that self-transcendence includes a concern about others, and a desire to contribute to the good of community, in either an immediate or a global sense. We thus included parental wishes that their children be thoughtful towards others, that they be respectful (outside of the family context), honest, compassionate and caring, and polite. Within this, we also included the desire to have a child with morals and good values, and that the child contribute to society (on whatever scale), or be a good citizen, "to be able to be of service to the community".

In keeping with the idea that self-transcendence incorporates an understanding of others, we also included any mention of wanting a child who was tolerant of difference ("to grow up with the belief in itself that we are all different and it's OK to be who we are"), or who was aware of and respected cultural diversity (as opposed to being part of a culture); for example, "to be aware of other cultures wherever they are in the world". Interestingly, while belonging in a cultural sense was almost exclusively mentioned by non-European women, the idea of respecting cultural difference was almost exclusively mentioned by European women (which includes New Zealand European), seldom by Asian women, and not at all by those who identified as Māori, Pacific or New Zealander.

Conclusions and limitations

Overall, our findings suggest that Maslow's theory continues to have relevance to expectant parents in New Zealand today, and provides a useful framework for thinking about human needs and desires. In general, parents in this sample had positive hopes, dreams and expectations for their unborn child and they expressed aspirations for their child at all levels of the hierarchy. Hence, while infants primarily need their lower level (physiological and safety) needs met, this is not the sole focus of the parents' aspirations. Instead, many parents aspired to have their child's higher level needs met, needs that are typically associated with later development (belonging, esteem, self-actualisation and self-transcendence). It is possible that the needs identified by the parents for their as yet unborn children are, in fact, the current needs and feelings that motivate these parents (see, e.g., Kaplan et al., 2001). These needs may also vary by socio-economic status and other demographic variables, reflecting parental concerns and perceived needs. Having established a useful framework in this initial sub-sample analysis and described the different categories of responses, data from the full Growing Up in New Zealand sample will be able to be explored further quantitatively, and subsequent longitudinal analysis will allow us to see how needs change or play out over time.

The most common categories of hopes and dreams in this sample are for physiological and self-actualisation needs to be met, reflecting the dominance of the desire to have a healthy and happy baby. While Maslow (1970, cited in Feist & Feist, 2006) estimated that the average person would have only 10% of their self-actualisation needs met, it seems this is a desire for over 60% of our parents. Awareness of these perceived higher level needs has policy implications. As Feist and Feist (2006) pointed out, many societies emphasise the lower level needs and base their educational and political systems on meeting those needs, disregarding the higher level needs that many people strive for. Yet, there is also a move towards higher level indices of wellbeing or happiness to measure a country's progress (alongside the more common measures of gross domestic product); for example, in the United Kingdom there have been attempts to measure subjective wellbeing (Waldron & Office for National Statistics, 2010). This points to the increasing importance of finding out what helps people feel that their needs and the needs of their children are being met.

Maslow believed that everyone has the potential to reach the higher levels of his hierarchy and become self-actualised (Feist & Feist, 2006), but that not everyone does so. Feist and Feist noted that people are often not given opportunities to develop at the higher levels due to being deprived of lower level needs - whether it be food, safety, love or esteem - and hence find it difficult to move towards being self-actualised individuals. As our sample of nearly 7,000 New Zealand children grow up, we will be able to explore the extent to which their parents' early hopes and dreams become realities and what factors may enable the children to flourish.

The data have a few important limitations. Firstly, these data were responses to an open-ended question asked at the end of an interview and, as such, may have been affected by respondent fatigue. There is also a potential bias towards those who are more articulate, with longer responses potentially resulting in more categories being coded from their data. It is, however, likely that the issues of fatigue were randomly spread across the cohort, reducing specific bias. Future quantitative analysis of the full dataset will also allow for more detailed assessment of demographic differences in the frequency of idea units and the number of Maslow's categories mentioned by the participants to be identified. Despite these limitations, this study provides an important snapshot of parents' hopes and dreams for their unborn children's futures, and lays the groundwork for future longitudinal quantitative analysis on whether parents' early hopes and dreams for their children are realised, and how these hopes change over time.

Endnotes

1 The All Blacks are New Zealand's national rugby team.

References

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G.V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children's aspirations and career trajectories. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(1), 187-206.

- Bedford, R., & Didham, R. (2001). Who are the "Pacific Peoples"? Ethnic identification and the New Zealand Census. In C. Macpherson, P. Spoonley & M. Anae (Eds.), Tangata o te moana nui: The evolving identities of Pacific peoples in Aotearoa/New Zealand (pp. 21-43). Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

- Benner, A. D., & Mistry, R. S. (2007). Congruence of mother and teacher education expectations and low-income youth's academic competence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 140-153.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513-531.

- Burton, J. W. (1990). Conflict: Human Needs Theory. New York: St Martin's Press.

- Chan, T. W., & Koo, A. (2011). Parenting style and youth outcomes in the U.K. European Sociological Review, 27(3), 385-399.

- Choy, S. P., Horn, L. J., Nuez, A. M., & Chen, X. (2000). Transition to college: What helps at-risk students and students whose parents did not attend college. New Direction for Institutional Research, 27(3), 45-63.

- Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113(3), 487-496.

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34-43.

- Durie, M. (1998). Whaiora: Māori health development (2nd ed.). Auckland: Oxford University Press.

- Edwards, C. P., Knoche, L., Aukrust, V., Kumru, A., & Kim, M. (2006). Parental ethnotheories of child development: Looking beyond independence and individualism in American belief systems. In U. Kim, K. Yang & K. Hwang (Eds.), Indigenous and cultural psychology: Understanding people in context (pp. 141-162). New York: Springer.

- Eibach, R. P., Libby, L. K., & Gilovich, T. D. (2003). When change in self is mistaken for change in the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 917-931.

- Ensminger, M. E., & Slusarcick, A. L. (1992). Paths to high school graduation or dropout: A longitudinal study of a first-grade cohort. Sociology of Education, 65(2), 95-113.

- Fan, S., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students' academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 1-22.

- Feist, J., & Feist, G.J. (2006). Theories of personality. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Gambrel, P. A., & Cianci, R. (2003). Maslow's hierarchy of needs: Does it apply in a collectivist culture. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship. 8(2), 143-161.

- Gorman, D. (2010). Maslow's hierarchy and social and emotional wellbeing. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 34(1), 27-29.

- Hofstede, G. (1984). The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept. Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 389-398.

- Jacobs, N., & Harvey, D. (2005). Do parents make a difference to children's academic achievement? Differences between parents of higher and lower achieving students. Educational Studies, 31(4), 431-448.

- Kaplan, D. S., Liu, X., & Kaplan, H. B. (2001). Influence of parents' self-feelings and expectations on children's academic performance. The Journal of Educational Research, 94(6), 360-370.

- Koltko-Rivera, M. E. (2006). Rediscovering the later version of Maslow's hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology, 10(4), 302-317.

- LeVine, R. A. (1988). Human parental care: Universal goals, cultural strategies, individual behavior. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 40, 3-12.

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

- Max-Neef, M. A., Elizalde, A., & Hopenhayn, M. (1991). Development of human needs. In M.A. Max-Neef (Ed.), Human scale development: Conception, application, and further reflections. New York: The Apex Press.

- Morton, S. M. B., Atatoa Carr, P. E., Grant, C. C., Robinson, E.M., Bandara, D.K., Bird, A., Wall, C.R. (2012). Cohort profile: Growing Up in New Zealand. International Journal of Epidemiology. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr206.

- Ngan-Woo, F. E. (1985). FaaSamoa: The world of Samoans. Auckland: Office of the Race Relations Conciliator.

- Paguio, L. P., Skeen, P., & Robinson, B. E. (1989). Difference in perceptions of the ideal child among American and Filipino parents. Early Child Development and Care, 50(1), 67-74.

- Pajares, F., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Self and self-belief in psychology and education: An historical perspective. In J.M. Arsonson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement (pp. 1-31). New York: Academic Press.

- Piontkowski, U., Florack, A., Hoelker, P., & Obdrzálek, P. (2000). Predicting acculturation attitudes of dominant and non-dominant groups. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 24(1), 1-26.

- Reese, L., Balzano, S., Gallimore, R., & Goldenberg, C. (1995). The concept of education: Latino family values and American schooling. International Journal of Educational Research, 23(1), 57-81.

- Rosenberg, M. D. (2003). Non-violent communication: A language of life. Ecinintas CA: Puddle Dancer Press.

- Salmond, C., Crampton, P., & Atkinson, J. (2007). NZDep 2006 Index of Deprivation (Dept of Public Health, Trans.). Wellington: University of Otago.

- Shek, D. T. L., & Chan, L. K. (1999). Hong Kong Chinese parent's perceptions of the ideal child. The Journal of Psychology, 133(3), 291-302.

- Statistics New Zealand. (2005). The Statistical Standard for Ethnicity 2005. Statistics New Zealand: Wellington.

- Suizzo, M. A. (2007). Parent's goals and value for children: Dimensions of independent and interdependence across four U.S. ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(4), 506-530.

- Tamis-LeMonda, C., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kahana Kalman, R., & Niwa, E. Y. (2007). Parent's goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17(1), 183-209.

- Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354-365.

- Tudge, J. R. H., Hogan, T. P., Snezhkova, I. A., Kulakova, N. N., & Etz, K. E. (2000). Parents' child-rearing values and beliefs in the United States and Russia: The impact of culture and social class. Infant and Child Development, 9(2), 105-121.

- Waldron, S., & Office for National Statistics. (2010). Measuring subjective wellbeing in the UK: Working paper. Newport, South Wales: Office for National Statistics.

- Wood, D., Kaplan, R., & McLoyd, V. (2007). Gender differences in the educational expectations of urban, low-income African American youth: The role of parents and the school. Journal of Youth and Adolesence, 36(4), 417-427.

Elizabeth R. Petersen is employed in the School of Psychology, University of Auckland. Johanna Schmidt is part of the School of Social Sciences, University of Waikato, Hamilton. Elizabeth R. Peterson and Johanna Schmidt contributed equally to this work. Elaine Reese is employed in the Department of Psychology, University of Otago, Dunedin. Arier C. Lee and Cameron C. Grant are employed in the Department of Paediatrics: Child and Youth Health, University of Auckland, and Cameron C. Grant also works at the Starship Children's Hospital, Auckland District Health Board. Susan M. B. Morton is employed in the School of Population Health, University of Auckland. Arier C. Lee, Polly Atatoa Carr, Cameron C. Grant and Susan M. B. Morton are all part of the Centre for Longitudinal Research - He Ara ki Mua, University of Auckland.

The authors acknowledge the children and the families who are part of the Growing Up in New Zealand study. Their collective information provides us with the record of what it is like to grow up in New Zealand today, and the project would not exist without them. We thank Dinusha Bandara, Jan Pryor, Elizabeth Robinson and Karen Waldie for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript, and we acknowledge all members of the Growing Up in New Zealand team. We would also like to acknowledge the initial funders of the Growing Up in New Zealand study; in particular, the New Zealand Ministry of Social Development. The Ministry of Health and the University of Auckland (with Auckland UniServices Limited) have also contributed considerable funding and support and we acknowledge other agencies who have provided funding and support to the study including the Ministries of Education, Justice, Science and Innovation, Women's Affairs and Pacific Island Affairs, the Departments of Labour and Corrections, Te Puni Kokiri (Ministry of Māori Affairs), the Families Commission, New Zealand Police, Sport and Recreation New Zealand, Housing New Zealand and the Mental Health Commission.

Peterson, E. R., Schmidt, J., Reese, E., Lee, A. C., Atatoa Carr, P., Grant, C. C., & Morton, S. M. B. (2014). "I expect my baby to grow up to be a responsible and caring citizen": What are expectant parents' hopes, dreams and expectations for their unborn children? Family Matters, 94, 35-44.