Pathways of Care

Longitudinal study on children and young people in out-of-home care in New South Wales

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

October 2014

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Pathways of Care is a longitudinal study on the wellbeing of children and young people placed in out-of-home care in New South Wales and the factors that influence their wellbeing. It will provide a strong evidence base to inform policy and practice, and in turn improve decision making about how best to support children and young people who have experienced abuse and neglect. Data collection commenced in May 2011 and will be completed by June 2016. This article introduces the study and describes its research objectives, sample frame, retention strategies, and methodology.

Out-of-home care (OOHC) is alternative care for children and young people under 18 years of age who are unable to live with their parents. Children and young people enter OOHC for a variety of reasons, including exposure to significant risk of harm from physical, sexual or emotional abuse and neglect, or because their parents' ability to care for them has been severely compromised by factors such as poor mental health, drug and alcohol misuse or domestic violence. The NSW Standards for Statutory OOHC are that children and young people are safe, developing well in a stable and positive environment matched to their needs and, where possible, successfully restored to their family. The standards stipulate that children's and young people's rights are a primary focus for their care; they have a positive sense of identity and connections with family and significant people; they contribute to decisions relating to their lives; and carers are supported to raise children and young people (NSW Office of the Children's Guardian, 2013).

In NSW, 18,300 children and young people were in OOHC at 30 June 2013 (NSW Department of Family and Community Services [FACS], 2014). The main placement types were relative/kinship care (53%) and foster care (39%); only a small number of children and young people were in residential care (3%) (NSW FACS, 2014). Aboriginal children and young people are over-represented in OOHC in NSW and at 30 June 2013 made up 35% of the OOHC population (NSW FACS, 2014). For some children, OOHC is a long-term arrangement, but for others, it is short-term and they are returned home. The Children's Court and child protection system are empowered to make critical decisions about parental responsibility and the care plan for children and young people who have been abused or neglected. These decisions are intended to improve the long-term safety and wellbeing of children and young people and be evidence-informed.

Research overseas and in Australia has found that children and young people in OOHC fare poorly in comparison with their peers in terms of their physical health, socio-emotional wellbeing and cognitive/learning ability (e.g., Nathanson & Tzioumi, 2007; Octoman, McLean & Sleep. 2014; Sawyer, Carbone, Searle, & Robinson, 2007; Tarren-Sweeny & Hazell, 2006). In the past decade, several research audits have been undertaken on OOHC in Australia (Bromfield, Higgins, Osborn, Panozzo, & Richardson, 2005; Bromfield & Osborn, 2007; Cashmore & Ainsworth, 2004; McDonald, Higgins, valentine, & Lamont, 2011; Osborn & Bromfield, 2007). While these audits indicate that individual studies are of a high quality and provide important insights for policy and practice, more research is needed to provide a reliable evidence base, and one that allows for a proper exploration of the linkages between children's developmental status at entry to care, their experiences in care, and their later developmental outcomes. Existing research is limited by cross-sectional designs, single sites, low response rates, small sample sizes and a lack of validated measures. There is a clear need for a large-scale prospective longitudinal study of children and young people in OOHC, to examine developmental trajectories over time, in order to identify factors that improve wellbeing.

Taplin's (2005) review of the literature on methodological issues in OOHC research outlines the benefits of longitudinal designs over other study designs. While cross-sectional data allow the investigation of differences between individuals, a longitudinal study using repeated measures can examine change within individuals, as well as between individuals, from one data point to the next (Farrington, 1991; Hunter et al., 2002). Prospective studies can document the developmental changes that occur as children and young people grow and change from early childhood through to young adult years, as well as examine possible risk and protective factors in greater detail. Collecting data prospectively also avoids the problems of recall bias that occur in retrospective studies. Large-scale prospective longitudinal studies can help answer such questions as: "Under what circumstances do children in care do well?" Longitudinal studies also allow inferences about causal linkages and associations between multiple factors related to children's backgrounds and experiences before they enter care, their experiences in care, the services they receive, and their longer term outcomes. This is not possible with cross-sectional designs.

The Pathways of Care longitudinal study

The Pathways of Care longitudinal study (POCLS) is a new prospective longitudinal study designed to address the methodological limitations of previous research. The overall aim of this longitudinal study of children and young people in OOHC is to collect detailed information about the wellbeing of children placed in OOHC in NSW and the factors that influence their wellbeing. It will provide a strong evidence base to inform policy and practice, and in turn improve decision making about how best to support children and young people who have experienced abuse and neglect.

This five-year study, which commenced in March 2011, differs from previous Australian research in OOHC because the population cohort is all children and young people entering OOHC for the first time and includes children of all ages as well as all geographic locations in NSW. It also collects information from multiple sources, including carers, children and young people, caseworkers, teachers and administrative data through record linkage. The study has a broad scope and collects detailed information about the characteristics and circumstances of children and young people on entry to OOHC, the experiences of children and young people in OOHC, and their developmental pathways in order to identify the factors that influence their outcomes. The developmental domains of interest are the children's physical health, social-emotional wellbeing and cognitive/learning ability. POCLS will follow children and young people regardless of their pathways through OOHC (e.g., placement changes, restoration, adoption or ageing out) to examine the factors that predispose children and young people to poorer outcomes and what factors are protective (see Box 1).

Box 1: Research objectives and key research questions

POCLS objectives are to:

- describe the characteristics, child protection history, development and wellbeing of children and young people at the time they enter OOHC on Children's Court orders for the first time;

- describe the services, interventions and pathways for children and young people in OOHC, post-restoration, post-adoption and on leaving care at 18 years;

- describe children's and young people's experiences while growing up in OOHC, post-restoration, post-adoption and on leaving care at 18 years;

- understand the factors that influence the outcomes for children and young people who grow up in OOHC and are restored, are adopted or leave care at 18 years; and

- inform policy and practice to strengthen the OOHC service system in NSW and improve the outcomes for children and young people in OOHC.

POCLS will answer the following key research questions:

On entry to OOHC:

1. What are the backgrounds and characteristics of the children and young people entering OOHC, including their demographics, child protection history, reasons for entering care and duration of the legal order?

2. What is the physical health, socio-emotional wellbeing and cognitive/learning ability of the children and young people entering OOHC compared with other children in the community?

3. How are the Aboriginal Child Placement Principles used in placement decision-making for Aboriginal children and young people entering OOHC?

During OOHC:

4. What are the placement, service intervention and case planning pathways for the children and young people during their time in OOHC?

5. What are the developmental pathways of the children and young people during their time in OOHC, post-restoration, post-adoption and on leaving care at 18 years?

6. How safe are the children and young people during their time in OOHC, post-restoration, post-adoption and on leaving care?

7. How prepared are children and young people for restoration, adoption or the transition out of care at 18 years?

Outcomes from OOHC:

8. What are the placement characteristics and placement stability of the children and young people, and how do these influence their outcomes?

9. In what ways are service interventions related to the outcomes for the children and young people, and how is this affected by their developmental status when they entered care?

10. In what ways do the characteristics of the child, carer, home/family and community affect the children's and young people's developmental pathways, and how do these differ from similarly situated children in the general population?

11. How does contact between the children and young people in OOHC and their birth parents, siblings and/or extended family influence their outcomes?

12. How well do the administrative data capture relevant information about the process and quality of care for assessments, case planning and permanency planning, and how can it be improved?

The NSW Department of Family and Community Services (FACS) is funding and leading the study, and has contracted a team of experts to provide advice on the study design and undertake data collection and longitudinal analysis. These experts are:

- a consortium of Australian researchers led by Dr Daryl Higgins and Ms Diana Smart at the Australian Institute of Family Studies. The research consortium includes:

- Associate Professor Judy Cashmore, Socio-Legal Research and Policy, Law School, University of Sydney;

- Associate Professor Paul Delfabbro, School of Psychology, University of Adelaide; and

- Professor Ilan Katz, Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales;

- Dr Fred Wulczyn, Director, Center for State Child Welfare Data, Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago; and

- Mr Andy Cubie, I-view, an independent social research data collection agency.

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee.

POCLS sample frame

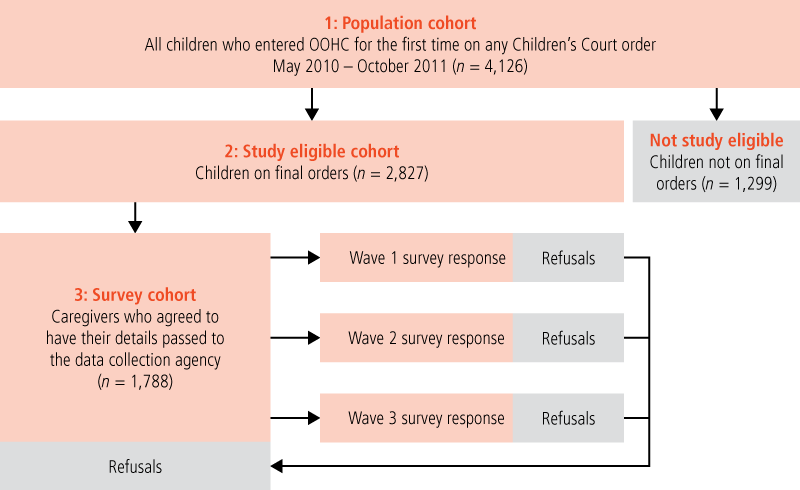

There are three groups of children and young people within the POCLS sample as described below and illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: POCLS sample flow chart

1. Population cohort (n = 4,126)

The sample frame for POCLS is all children and young people aged 0-17 years entering OOHC for the first time under the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998 across New South Wales within an 18-month period between May 2010 and October 2011 (n = 4,126). For the purpose of this study, OOHC commences from the day the child or young person is legally removed from the guardianship of their parent(s) and a care and protection order is enforced. In the population cohort, there are children and young people on interim orders who are assessed as being able to return to their parents' care, with appropriate services and supports; as well as those who stay in OOHC on final Children's Court orders.

This sample frame of first-time entries into OOHC provides the opportunity to understand the developmental pathways of children placed in OOHC, while preventing the confounding influence of past OOHC experiences.

Children and young people were selected for this cohort using FACS administrative data stored in the Key Information Directory System (KiDS). Record linkage is the key data source for this cohort.

2. Study eligible cohort (n = 2,827)

A subset of the population cohort is the study eligible cohort (n = 2,827), which includes children and young people who went on to receive final Children's Court orders allocating parental responsibility to another party. Primary data collection is the key data source for this cohort and, over the five years of the study, will include several placement and legal pathways, such as long-term OOHC, restoration, adoption and leaving care (18 years and older).

3. Survey cohort (n = 1,788)

The survey cohort consists of children and young people from the study eligible cohort whose carers agreed to have their contact details passed from FACS to the data collection agency and then were invited to participate in a face-to-face interview at each wave of data collection. POCLS sample recruitment was a three-step process:

- Step 1: OOHC regional staff were asked to verify the children's and young people's demographic details, legal status and contact information before they were invited to participate in POCLS.

- Step 2: FACS researchers contacted carers by a pre-approach letter and phone call to ask for their consent for their contact details to be securely passed from FACS to the independent data collection agency.

- Step 3: At every wave of data collection, the data collection agency contacts the carers via telephone to invite them to participate in a face-to-face interview. If at subsequent waves the children and young people have changed placement or been restored, Step 2 is repeated so the child or young person can continue to participate in the study. Out of 2,827 children and young people in the study eligible cohort, 1,788 (63%) agreed to have their details passed to the data collection agency.

Carers who did not agree to have their details passed to the data collection agency will not be contacted for participation in any of the waves of data collection. These carers gave the following reasons for not agreeing: carers' busy schedules, they did not want the child to be seen as different to others in the household, or they just did not want to be in this research study.

Wave 1 survey cohort

At Wave 1, 1,597 of the 1,788 children and young people in the survey cohort were placed with foster carers, with relative/kinship carers or in residential care; and 191 had been restored to their birth parents. The 191 who were restored were not invited to participate in a Wave 1 interview for pragmatic and ethical reasons, but will be invited to participate in all subsequent waves of interviews.

The Wave 1 survey sample was drawn from 1,597 children and young people placed with carers at the time of the Wave 1 interview. Carers of 1,285 of the children and young people completed a Wave 1 survey. Many carers had more than one child in POCLS in their care, so the number of households who took part in the Wave 1 survey totalled 899. Carers gave written informed consent to participate prior to the face-to-face interview. Children and young people over 7 years of age also gave written informed consent. The overall response rate for the Wave 1 survey was 56% (1,285/2,312; see Table 1). At the time of the Wave 1 survey, 50% of the children and young people were in foster care, 48% in relative/kinship care and 2% in residential care. These distributions are similar to the placements of children and young people in OOHC within NSW (39% foster care, 52% kinship care and 3% residential care; NSW FACS, 2014).

Table 1 provides an overview of the POCLS sample characteristics, including age at entry to OOHC, sex of child, Aboriginality, and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (CALD) of the children and young people. Of those whose carers completed a Wave 1 face-to-face interview, more than half were aged under 3 years at the time of entry to OOHC. The sample was evenly divided into female and male, and just under 10% were CALD. One-third were Aboriginal, similar to the 35% of the overall proportion of Aboriginal children and young people in OOHC in NSW (NSW FACS, 2014).

Sample retention

As with any longitudinal study, a key issue for POCLS will be to maximise sample recruitment and retention rates over the life of the research. A low and/or biased pattern of sample recruitment into a study combined with high or differential attrition rates can affect the generalisability of the data. For children and young people who remain in OOHC, FACS client data (KiDS) will be the source of up-to-date contact details; it will be more difficult, however, to keep track of the children and young people who are restored, adopted or aged out of OOHC.

The study uses a number of strategies to enhance sample recruitment, retention and engagement:

- an engaging study logo, which is based on artwork by a young person who grew up in care;

- POCLS brochures, a POCLS DVD for children and young people, and a POCLS DVD for adult stakeholders;

- a gift card given to interviewees to the value of $50 per carer interview, $30 per young person (12-17 years) interview, $20 per child (7-11 years) interview, and a picture book for children aged 3-6 years, in recognition of their time and contribution;

- a Certificate of Research Appreciation for the children and young people;

- feedback about the study results given to participants via newsletters;

- trained interviewers and a continuity of interviewers across waves where possible;

- newsletter articles and briefings provided for FACS and other staff; and

- a POCLS webpage and an 1800 freecall telephone number.

Study questions and measures

Questionnaire modules for carers, children and young people were selected and developed based on the information required in order to answer the key research questions of the study. Where possible, existing standardised measures and validated questions were selected so that the POCLS sample could be compared with other Australian general population studies, such as the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) and the Australian Temperament Project; and international longitudinal studies involving OOHC populations, such as LONGSCAN and NSCAW in the United States. The appendix to this article provides a summary of the questions and measures used in POCLS face-to-face interviews to assess the wellbeing of children and young people and characteristics of the carer and the placement.

The domains of child physical health, socio-emotional development and cognitive/learning are the key outcomes of interest to the study, so considerable effort has been made to ensure questions and measures have good psychometric properties (where possible), have norms or comparison groups available, are suitable to OOHC populations, and are acceptable to carers.

Physical health is measured by carer-rated questions to determine the health condition of the children and young people (including disabilities), services and supports for health conditions, changes in health conditions over time, and questions about diet, sleep and weight. The carer-rated Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ3; Squires & Bricker, 2009) is also used to measure gross and fine motor skills (as well as communication, problem-solving and personal-social domains) in children aged up to 60 months.

| Population cohort (All children entering OOHC on any Children's Court order) | Study eligible cohort (Children on final orders) | Survey cohort (Caregivers who agreed to have their details passed to the data collection agency) | Wave 1 survey response b | Wave 1 response rate c | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with carers a | Children restored to birth parents a | Total | Children with carers a | Children restored to birth parents a | Total | Children with carers | Children with carers | ||||||||||

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | % | |

| Age of child at first entry to OOHC | |||||||||||||||||

| 0-35 months | 1,652 | 40.0 | 1,131 | 48.9 | 222 | 43.1 | 1,353 | 47.9 | 843 | 52.8 | 84 | 44.0 | 927 | 51.8 | 708 | 55.1 | 62.6 |

| 3-6 years | 946 | 22.9 | 566 | 24.5 | 121 | 23.5 | 687 | 24.3 | 388 | 24.3 | 44 | 23.0 | 432 | 24.2 | 299 | 23.3 | 52.8 |

| 7-11 years | 835 | 20.2 | 417 | 18.0 | 117 | 22.7 | 534 | 18.9 | 256 | 16.0 | 42 | 22.0 | 298 | 16.7 | 205 | 16.0 | 49.2 |

| 12-17 years | 693 | 16.8 | 198 | 8.6 | 55 | 10.7 | 253 | 8.9 | 110 | 6.9 | 21 | 11.0 | 131 | 7.3 | 73 | 5.7 | 36.9 |

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 2,060 | 49.9 | 1,184 | 51.2 | 268 | 52.0 | 1,452 | 51.4 | 793 | 49.7 | 88 | 46.1 | 881 | 49.3 | 637 | 49.6 | 53.8 |

| Female | 2,066 | 50.1 | 1,128 | 48.8 | 247 | 48.0 | 1,375 | 48.6 | 804 | 50.3 | 103 | 53.9 | 907 | 50.7 | 648 | 50.4 | 57.4 |

| Cultural background d | |||||||||||||||||

| Aboriginal | 1,346 | 32.6 | 837 | 36.2 | 121 | 23.5 | 958 | 33.9 | 592 | 37.1 | 40 | 20.9 | 632 | 35.3 | 453 | 35.3 | 54.1 |

| CALD | 429 | 10.4 | 233 | 10.1 | 65 | 12.6 | 298 | 10.5 | 142 | 8.9 | 29 | 15.2 | 171 | 9.6 | 114 | 8.9 | 48.9 |

| All other children | 2,351 | 57.0 | 1,242 | 53.7 | 329 | 63.9 | 1,571 | 55.6 | 863 | 54.0 | 122 | 63.9 | 985 | 55.1 | 718 | 55.9 | 57.8 |

| Total | 4,126 | 100.0 | 2,312 | 100.0 | 515 | 100.0 | 2,827 | 100.0 | 1,597 | 100.0 | 191 | 100.0 | 1,788 | 100.0 | 1,285 | 100.0 | 55.6 |

Notes: a At the time of recruitment to the study.

b At Wave 1, only children living with carers were interviewed. Children restored and adopted in the survey cohort will be invited to participate in an interview at Waves 2 and 3.

c Participation rate for the carer sample at Wave 1 was calculated as the number of survey responses/study eligible cohort.

d If cultural background was unspecified in KiDS, the cases are included in the "All other children" category.

Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: FACS KiDS

To measure socio-emotional outcomes according to carers' report, two standardised measures were used at Wave 1:

- The Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA; Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel, & Cicchetti, 2004) was used for ages 1-2 years, to assess social-emotional/behavioural problems and social-emotional competencies.

- The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used for carers of children aged 1.5-5 years (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) and aged 6-18 years (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The CBCL was selected because it is a widely used and comprehensive measure of externalising and internalising behaviour problems and interpersonal competencies. The CBCL has also been used in previous studies of children in OOHC in Australia (Sawyer et al., 2007; Tarren-Sweeney & Hazell, 2006), so will allow comparisons with those samples.

Information was also collected on services and supports for mental health problems, behaviour problems in the school environment, and whether or not the child or young person was prescribed psychotropic medication for their behaviour. Children and young people aged 7 and over were asked questions about their socio-emotional wellbeing, peer relationships, friendships, school, health, carers and caseworkers. To assess conduct problems, the Self-report Delinquency Scale (Moffitt & Silva, 1988) was used from 10 years, and to assess emotional wellbeing, school engagement and problems at school, three scales were used from 12 years (see the appendix).

To examine children's cognitive/learning outcomes, several language measures and a measure of non-verbal reasoning were selected:

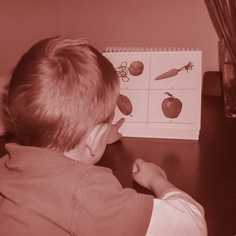

- To assess receptive language skills, the widely used Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th Edition (PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 2007) was administered by interviewers to children aged 3 years and older.

- Three additional carer-rated measures of language were used, depending on the age of the child, for children aged 1-2 years (see the appendix).

- To assess non-verbal reasoning, the Matrix Reasoning Test from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC; Wechsler, 2003) was administered by interviewers to children and young people aged 6-17 years. These measures have norms that enable comparisons to children and young people in the general population. Educational outcomes were also examined through questions about school performance (such as grades attained).

Questions and measures were also selected to assess characteristics of the carer and the placement, including: carer mental health; parenting practices, parenting style and difficult behaviour self-efficacy; satisfaction with support from services; carer socio-demographic characteristics; relationship with partner; carer experience and training; support network; and physical health (see the appendix).

Sources of information and data collection methods

1. Survey of carers, children and young people

For those agreeing to participate in the survey, POCLS involves three waves of face-to-face interviews with carers, children and young people; and activities to measure the child's language development, non-verbal reasoning and felt security (see Table 2).

Where requested, the data collection agency arranges for interpreters and Aboriginal interviewers.

At each wave, the study child or young person has to have lived with the carer for a minimum of one month before data collection takes place to ensure carers have sufficient knowledge about the child or young person. The study will continue to follow up children and young people restored to parents, adopted or aged out of OOHC.

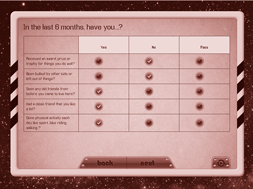

The interviews are conducted in the carer's home or at an alternative location that the carer selects. Children aged 7 years and older watch the POCLS DVD before they are interviewed and sign an agreement form to ensure that they understand they are voluntarily participating in a research study. From ages 3 years and up, study children are involved in one or more interviewer-administered measures. The interview for children aged 7 years and older is programmed into an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). The ACASI contains questions about their views and experiences of being in OOHC. Children are assisted by a trained interviewer if needed.

| Language development assessment for ages 3-17 years This child is completing the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn, 2007) with a trained interviewer. The child was asked to point to the "leaf". |

| Non-verbal reasoning assessment for ages 6-16 years This young person is completing the Matrix Reasoning Test from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Wechsler, 2003) with a trained interviewer. The young person is asked to point to the picture that completes the sequence of patterns. |

| Felt security activity for ages 7-17 years This child is completing the activity to show who they feel close to, including members of the household where they are currently living and also family members with whom they are not currently living (adapted from the Kvebaek Family Sculpture Technique; Cromwell, Fournier, & Kvebaek, 1980). A trained interviewer instructs the child how to use the checkerboard and figurines to complete the activity. |

| Face-to-face interview for ages 7-11 years This child is completing a computer-assisted personal interview with a trained interviewer. This is a short questionnaire with both qualitative and quantitative questions about school, friends, feelings, behaviour, casework, support and where they are living. The interviewer asks the child if there is anything else they would like to say. |

| Self-complete interview for ages 12-17 years This young person is completing an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) on an iPad, with the voice recording done by Sammy Verma, who grew up in care. ACASI allows the young person to answer the questionnaire in a confidential setting. |

| This picture shows the I-view custom-designed ACASI survey, which has a space theme to make the experience more engaging. Questions are asked about school, work, friends, health and wellbeing, behaviour, casework, support, where they are living, leaving care and living skills. There is a text box for recording other thoughts. |

| The I-view ACASI self-interview allows for privacy and standardisation in the interview. A "play" button allows the questions to be repeated. ACASI benefits young people who have difficulty reading and understanding written concepts without additional aids. There are also games on the iPad for the young people to play when they have completed the questionnaire. |

Most of the carer face-to-face interview questions are programmed into a computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) system. Due to the sensitivity of some of the questions, and the possible discomfort a carer may feel in answering these questions in the presence of the interviewer (or other family member), a computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) section has been programmed into the middle of the face-to-face interview.

The CASI section contains questions regarding the carer's physical health, their relationship with their partner, and their level of psychological distress (using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [K10]; Kessler et al., 2003). The CASI section also serves to break up the long interview (between 90-120 minutes). If the carer is uncomfortable or unable to complete the CASI section on their own, the interviewer assists them. This information is then recorded by the interviewer at the end of the CASI section.

Interviewer ratings are completed after interviews with carers, children and young people. The ratings allow the interviewers to record information about the environment; for example, carers needing to manage several children and being distracted by interruptions. Ratings are also completed on the home environment itself. In addition, the interviewers record useful information for subsequent waves of data collection, such as whether the carer is planning to move house or location.

2. Survey of child care workers and teachers

For the Wave 2 survey with carers, the data collection agency is seeking carers' consent to contact the child's child care worker, preschool or school teacher to complete an Internet-based survey about the child or young person. Child care workers and teachers can provide an important independent perspective about risk and protective factors that are likely to be predictive of the child's or young person's educational outcomes and socio-emotional development. Emotional and behavioural problems may occur in one context only (home only or school only) or across contexts, so it is important to obtain this information. The survey will include the Child Behaviour Checklist Teacher Report Form (TRF) for school-age children and the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form (C-TRF) for children at child care and preschool (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). This will enable educators to report on children's socio-emotional wellbeing in the child care/preschool/school context, using the same measure that is used by carers. Teachers will also report on children's educational attainment, peer relationships, OOHC education plans and carer's level of involvement in the child care centre, preschool or school.

3. Survey of caseworkers

In Wave 2, a caseworker Internet-based survey is being administered to the study eligible cohort (n = 2,827). The aim of this survey is to gain the views of OOHC caseworkers, and to obtain information about the child and the placement that cannot be extracted from FACS administrative data (KiDS) or any other sources. Caseworkers provide an important perspective that complements the data obtained from carers, children and young people. The scope of the data collected includes: caseworkers' views on the children's or young people's placement; the children's or young people's development and wellbeing; family contact arrangements; the level of casework with the children or young people and their birth families; the case plan goal, including restoration and adoption if relevant; and the level of support provided to caseworkers.

4. Record linkage

Record linkage provides a rich source of data for the POCLS population cohort (n = 4,126) to learn about the child's life before, during and, in many cases, after children and young people have left OOHC. Record linkage brings together information that relates to the same individual from different administrative data sources. To ensure privacy requirements are met, record linkage will be performed by an authorised linking agency - the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL). Access to health, education and juvenile offending data, can give a broader range of outcome measures than is possible when using only FACS administrative data on child protection and OOHC.

Record linkage, along with the primary data collections for this study, will allow the researchers to build a chronological sequence of life events to better understand the outcomes of children and young people. Record linkage will also allow the study to have more comparison groups, which will strengthen the findings and usefulness of the study. Record linkage will allow researchers to compare outcomes with aggregated data at the local government area (LGA) level (pending large enough samples so no child/young person can be identified) rather than relying on population norms, which may not be typical of the child or young person's geographic area.

FACS aims to link four external data sources to the POCLS database, in addition to FACS administrative data on child protection and OOHC:

- The Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) Checklist conducted in 2009 and 2012 measures five areas of early childhood development in the first year of school (teacher-completed checklist), including physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills, communication skills and general knowledge (Commonwealth Department of Education).

- Education records for all Australian students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 collected via the National Assessment Program: Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) tests. Proficiency levels, reported as a band, in reading, writing, language conventions (spelling, grammar and punctuation) and numeracy at the unit-record level (NSW Department of Education and Communities).

- Health records, including those regarding gestational age, birth weight, APGAR scores and neonatal intensive care, mental health diagnosis, hospital admissions and emergency department visits, mother's age and mother's postcode at child's birth date, antenatal care, smoking during pregnancy and birth order (NSW Ministry of Health).

- Youth offending data, including the number of offences, most serious offence, and penalty severity (Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research).

The sources of administrative data summarised above will provide critical information for the POCLS Population Cohort, which will strengthen the findings and usefulness of the study by providing strong population-based comparison groups.

Comparison groups

There are a number of comparison groups within the Population Cohort (see Figure 1) that enable additional research questions to be asked of the data. Record linkage will enable a comparison of children and young people with similar abuse and neglect backgrounds who entered OOHC on interim orders only with those who stayed in OOHC on final orders. This will shed light on decision-making by child protection workers and the Children's Court, and the outcomes of those decisions for the wellbeing of children and young people. Children in OOHC have poorer outcomes compared to those in the community, and the degree to which this is due to abuse and neglect versus the OOHC experience (e.g., placement breakdown) is not well understood. Record linkage will help answer this question.

The standardised measures and questions used by other studies, such as LSAC, will allow researchers to compare the POCLS sample with the general population, as will measures that have norms available.

Record linkage enables researchers to examine the representativeness of the Study Eligible Cohort, which will assist with the interpretation of the results of the primary data collection.

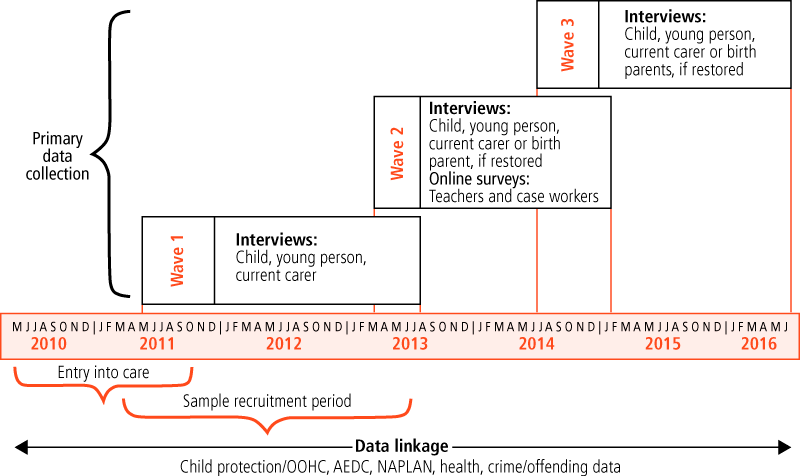

POCLS data collection timeline

Figure 2 shows the primary data collection and record linkage that will allow researchers to build a person period file to view the child's life at different stages - pre-care, in care, and post-care. The population cohort (n = 4,126) entered OOHC on any Children's Court order between May 2010 and October 2011. When a final Children's Court order was issued, the child was recruited to the study to participate in a survey of caregivers, children and young people. During February 2011 to June 2013, FACS undertook sample recruitment that resulted in 1,788 carers, children and young people agreeing to be in the POCLS survey cohort. April 2013 was the last date for the child or young person to receive final orders (leaving two months for FACS to recruit them). This timeframe gave every child and young person entering OOHC at least 18 months to receive final orders.

Figure 2: POCLS data sources timeline

Primary data collection commenced in May 2011 and will be completed by June 2016. In this five-year period there are three waves of data collection at 18-month intervals. The Wave 1 survey cut-off date was August 2013 and resulted in 1,285 survey responses. Wave 2 is currently in progress. Wave 3 will take place from July 2014 until June 2016.

Record linkage will be refreshed before the end of Wave 3, providing retrospective longitudinal data on the population cohort.

Data analysis and reporting

A series of research reports and policy papers will be published as the data become available after each wave of data collection.

For more information about the study, visit the study web page <www.community.nsw.gov.au/pathways>.

References

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families.

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families.

- Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., Pickles, A., Winder, F., & Silver, D. (1995). The development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5, 237-249.

- Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Carter, A. S., Irwin, J. R., Wachtel, K., & Cicchetti, D. V. (2004). The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: Screening for social-emotional problems and delays in competence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 29(2), 143-155.

- Bromfield, L., & Osborn, A. (2007) Getting the big picture: A synopsis and critique of Australian out-of-home care research. Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse.

- Bromfield, L., Higgins, D., Osborn, A., Panozzo, S., & Richardson, N. (2005). Out-of-home care in Australia: Messages from research. Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse.

- Cashmore, J., & Ainsworth, F. (2004). Audit of Australian out-of-home care research. Sydney, NSW: Child and Family Welfare Association of Australia; Association of Child Welfare Agencies.

- Cashmore, J., & Parkinson, P. (2008). The voice of a child in family law disputes. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Cromwell, R. E., Fournier, D., & Kvebaek, D. (1980). The Kvebaek Family Sculpture Technique: A diagnostic and research tool in family therapy. Jonesborough, TN: Pilgrimage.

- Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (4th ed.). Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson.

- Farrington, D. P. (1991). Longitudinal research strategies: Advantages, problems, and prospects. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(3), 369-374.

- Fenson, L., Marchman, V. A., Thal, D. J., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., & Bates, E., (2007). MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User's guide and technical manual (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Fenson, L., Pethick, S., Renda, C., Cox, J. L., Dale, P. S., & Reznick, J. S. (2000). Short-form versions of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics, 21(1), 95-116.

- Fullard, W., McDevitt, S. C., & Carey, W. B. (1984). Assessing temperament in one- to three-year old children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 9(2), 205-217.

- Goldberg, C. J., Spoth, R., Meek, J., & Moolgard, V. (2001). The Capable Families and Youth Project: Extension-university-community partnerships. Journal of Extension, 39(3). Retrieved from <www.joe.org/joe/2001june/a6.php>.

- Hastings, R. P., & Brown, T. (2002). Behavioural knowledge, causal beliefs, and self-efficacy as predictors of special educators' emotional reactions to challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 46, 144-150.

- Hunter, W. M., Cox, C. E., Teagle, S., Johnson, R. M., Mathew, R., Knight, E. D. et al. (2002). Measures for assessment of functioning and outcomes in longitudinal research on child abuse: Volume 2. Middle childhood. Chapel Hill, NC: LONGSCAN Coordinating Centre: University of North Carolina.

- Institut de la Statistique du Québec. (2000). Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Québec (ÉLDEQ 1998-2002): 5-month-old infants, parenting and family relations, Volume 1, Number 10. Québec, Canada: l'Institut de la Statistique du Québec.

- Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, J. C., Hiripi, E. et al. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 184-189.

- McClowry, S. G., Halverson, C. F., & Sanson, A. (2003). A re-examination of the validity and reliability of the School-Age Temperament Inventory. Nursing Research, 52(3), 176-182.

- McDonald, M., Higgins, D., valentine, k., & Lamont, A. (2011). Protecting Australia's Children Research Audit (1995-2010): Final report. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies & Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales.

- Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1988). Self-reported delinquency, neuropsychological deficit, and history of attention deficit disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16(5), 553-569.

- Nathanson, D., & Tzioumi, D, (2007). Health needs of Australian children living in out-of-home care. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 43(10), 695-699.

- NSW Department of Family and Community Services. (2014). Family and Community Services: Annual report 2012-13. Sydney: NSW FACS.

- NSW Office of the Children's Guardian. (2013). NSW standards for statutory out-of-home care. Sydney: NSW Office of the Children's Guardian.

- Octoman, O., McLean, S., & Sleep, J. (2014). Children in foster care: What behaviours do carers find challenging? Clinical Psychologist, 18(1), 10-20.

- O'Donnell, J., Hawkins, J. D., & Abbott, R. D. (1995). Predicting serious delinquency and substance use among aggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 529-537.

- Osborn, A., & Bromfield, L., (2007). Outcomes for children and young people in care. Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Paterson, G., & Sanson, A. (1999). The association of behavioural adjustment to temperament, parenting and family characteristics among 5 year-old children. Social Development, 8(3), 293-309.

- Prior, M., Sanson, A., Smart, D., & Oberklaid, F. (2000). Pathways from infancy to adolescence: Australian Temperament Project 1983-2000. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighbourhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918-924.

- Sawyer, M. G., Carbone, J. A., Searle, A. K., & Robinson, P. (2007) The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home based foster care, Medical Journal of Australia, 186(4), 181-184

- Squires, J., & Bricker, D. (2009). Ages & Stages Questionnaire (ASQ-3): A parent-completed child monitoring system (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Stockdale, D. F., Crase, S. J., Lekies, K. S., Yates, A. M., & Gillis-Arnold, R. (1997). Manual for foster parent research measures: Motivations for foster parenting inventory, attitudes towards foster parenting inventory, and satisfaction with foster parenting inventory. Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

- Taplin, S. (2005). Methodological design issues in longitudinal studies of children and young people in out-of-home care: Literature review. Sydney: NSW Centre for Parenting and Research, Funding and Business Analysis, NSW Department of Community Services.

- Tarren-Sweeney, M., & Hazell, P. (2006). The mental health of children in foster and kinship care in New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 42(3), 91-99.

- Wechsler, D. (2003). WISC-IV technical and interpretive manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

- Wetherby, A. M., & Prizant, B. M. (2003). CSBS DP: Infant-Toddler Checklist and Easy-Score user's guide. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

- Whenan, R., Oxlad, M., & Lushington, K. (2009). Factors associated with foster carer wellbeing, satisfaction and intention to continue providing out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(7), 752-760.

Appendix

| Domain | Questions and standardised measures | Carer-rated, child-rated or interviewer administered | Study age range | Used in other studies/ norms available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children's wellbeing | ||||

| Physical health and development | Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ3; Squires & Bricker, 2009) | Carer | 9 months-5 years | US Norms |

| Additional questions about health conditions, services received, immunisation, diet, weight, sleep | Carer | All | Project developed and used by other studies such as LSAC, ATP | |

| Child socio-emotional development | Short Temperament Scale for Infants, Toddlers and Children (STSI; Fullard, McDevitt, & Carey,1984) | Carer | 9 months-7 years | LSAC, ATP |

| School Aged Temperament Inventory (SATI; McClowry, Halverson, & Sanson, 2003) short form | Carer | 8-17 years | LSAC, ATP | |

| Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment BITSEA; Briggs-Gowan et al., 2004) | Carer | 12-35 months | LSAC, US Norms | |

| Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) | Carer | 3-17 years | NSCAW, LONGSCAN, US & Australian Norms | |

| Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ3; Squires & Bricker, 2009) | Carer | 9 months-5 years | US Norms | |

| School Problems Scale (Prior, Sanson, Smart, & Oberklaid, 2000) | Young person | 12-17 years | ATP | |

| School Bonding Scale (O'Donnell, Hawkins, & Abbott, 1995) | Young person | 12-17 years | ATP, Seattle Social Development Project | |

| Short Mood & Feeling Questionnaire 13-item scale (Angold et al., 1995) and additional questions on health and behaviour. | Young person | 12-17 years | LSAC, ATP, ASSAD | |

| Self Report Delinquency Scale 10-item scale adapted from (Moffitt & Silva,1988). | Young person | 10-17 years | ATP | |

| Felt Security activity to show who they feel close to (adapted from the Kvebaek Family Sculpture Technique; Cromwell, Fournier, & Kvebaek, 1980). | Child/young person | 7 years plus | Cashmore & Parkinson (2008) in family law study | |

| Additional questions for carers about services and supports for child emotional and behavioural problems, problems at school, child psychotropic medication | Carer | All | Project developed and used by other studies such as LSAC, ATP | |

| Additional questions for children and young people about peer relationships, friendships, school, health, carers and caseworkers | Child/young person | 7 years plus | Project developed and used by other studies such as LSAC, ATP | |

| Cognitive and language development | Communication and Symbolic Behaviour Scale Infant and Toddler Checklist (CSBS ITC; Wetherby & Prizant, 2003) | Carer | 9-23 months | LSAC, US Norms |

| MacArthur-Bates Communicative Developmental Inventories (MCDI-III; Fenson et al., 2007) | Carer | 30-35 months | LSAC, US Norms | |

| MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories - short form (Fenson et al., 2000) | Carer | 24-29 months | US Norms | |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-IV; Dunn & Dunn, 2007) | Interviewer administered | 3-17 years | Many studies, US Norms | |

| Matrix Reasoning Test from Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003) | Interviewer administered | 6-16 years | LSAC | |

| Additional questions about current schooling (usual grades at school, changes in schools, repeated years, school problems). For children aged 15 and older, questions on work and further education, life skills and plans for leaving care. | Carer | All | Project developed and used by other studies such as LSAC, ATP | |

| Carer and placement characteristics | ||||

| Carer psychological distress | Kessler K10 (Kessler et al., 2003) | Carer | All | LSAC, NSW Health Survey, Aus. Norms |

| Social cohesion | Social Cohesion and Trust Scale (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997) | Carer | All | LSAC |

| Parenting practices/ style/self-efficacy | Parenting - Warmth (Paterson & Sanson, 1999). | Carer | All | LSAC |

| Parenting - Hostility (Institut de la Statistique du Québec, 2000) | Carer | All | LSAC | |

| Parenting - Monitoring (Goldberg, Spoth, Meek, & Moolgard, 2001) | Carer | 12-17 years | LSAC | |

| Difficult Behaviour Self-Efficacy Scale (DBSES; Hastings & Brown, 2002) | Carer | All | Study by Whenan, Oxlad, & Lushington (2009) | |

| Additional questions for child about relationship with carer. | Child/young person | All | Project developed and used by other studies such as LSAC, ATP | |

| Satisfaction with support from services | Satisfaction with Foster Parenting Inventory (SFPI), Social Service Support Satisfaction Scale (Stockdale, Crase, Lekies, Yakes, & Gillis-Arnold, 1997) | Carer | All | - |

| Additional questions for carer about socio-demographic characteristics; relationship with partner; relationship with study child; carer experience and training; family activities; support network; carer physical health; cultural background and cultural activities. | Carer | All | Project developed and used by other studies such as LSAC, ATP | |

Notes: ASSAD - Australian Secondary Students' Alcohol and Drug Survey; ATP - Australian Temperament Project; LSAC - Longitudinal Study of Australian Children; LONGSCAN - Longitudinal Studies of Abuse and Neglect (US); NSCAW - National Survey of Child and Adolescent Wellbeing (US). These data will be supplemented with administrative data; for example, risk of harm reports and number of placements.

Paxman, M., Tully, L., Burke, S., & Watson, J. (2014). Pathways of Care: Longitudinal study on children and young people in out-of-home care in New South Wales. Family Matters, 94, 15-28.