Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children

Up and running

December 2014

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSiC) has now produced five waves of data, helping us explore how the early lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children can affect later outcomes. This article provides an overview of the study, including design and data collection methods, sample recruitment and retention, topics and measures, use of the participants' own words, and selected findings. The article also includes sections from Professor Maggie Walter, summarising her keynote speech from the 2013 LSAC/LSIC conference, and Sharon Barnes, who currently manages the interviewers and has been with the study since its inception.

Five waves of data from Footprints in Time became available in April 2014. This article provides an overview of the study including: the Indigenous area-based interviewers; high retention rates; and the study's repeating and changing content. There is also information about the release of participants' own words, whereby data users and readers can see quotes from study children and their families in response to some questions. The article includes features from Professor Maggie Walter, who summarises the keynote speech she delivered at the LSAC/LSIC conference in November 2013, and Sharon Barnes, who currently manages the interviewers and has been with the study since its inception. There are key findings from the study relating to school attendance, English reading, child health, languages, life events, and social and emotional wellbeing.

What is Footprints in Time?

There are now five waves of Footprints in Time data available, with the next two waves on their way (see Table 1). The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (also known as LSIC and Footprints in Time) is an Australian government-funded survey managed by the Department of Social Services (DSS, formerly FaHCSIA); the study was established to help us understand how the early lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children affect later outcomes. Footprints in Time explores the different development pathways Indigenous children travel to determine what contributes to positive and healthy social, emotional, educational and developmental outcomes.

| Born in | 2008 Wave 1 | 2009 Wave 2 | 2010 Wave 3 | 2011 Wave 4 | 2012 Wave 5 | 2013 Wave 6 | 2014 Wave 7 | 2015 Wave 8 | 2016 Wave 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cohort | 2006 | 6 months- 2 years | 1½-3 years | 2½-4 years | 3½-5 years | 4½-6 years | 5½-7 years | 6½-8 years | 7½-9 years | 8½-10 years |

| 2007 | ||||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||||

| K cohort | 2003 | 3½-5 years | 4½-6 years | 5½-7 years | 6½-8 years | 7½-9 years | 8½-10 years | 9½-11 years | 10½-12 years | 11½-13 years |

| 2004 | ||||||||||

| 2005 |

Footprints in Time is guided by a Steering Committee of experts in the fields of Indigenous research, early childhood, education and health. The committee has been chaired by Professor Mick Dodson AM since 2003.

In 2008, the first wave of the study, two groups of more than 1,600 families across remote, regional and urban Australia, were interviewed about their Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander babies (the B cohort, n = 954) or 3-4 year olds (the K cohort, n = 717). Now the Footprints in Time children are all in primary school and Wave 7 interviews are being conducted. It is a privilege and a joy to watch the children grow, learn and thrive, and sad to see how much life stress many families are coping with. Sharon Barnes, who has worked with the study for ten years, has written a personal account of life with Footprints in Time, which can be read later in this article.

A brief overview of the Footprints in Time design follows. Further information about the study's community consultation, design, development and sampling can be found in the LSIC Wave 1 and 2 reports (FaHCSIA, 2009, 2011), in the article "Footprints in Time: A guide for the uninitiated" (Dodson et al., 2012) and in the cohort profile by Thurber, Banks, and Banwell (2014). This article concentrates on what makes Footprints in Time a unique and valuable source of data for Indigenous research.

The Footprints in Time study has four key research questions, formulated under the guidance of the Steering Committee. These are:

- What do Indigenous children need to have the best start in life and to grow up strong?

- What helps Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to stay on track or get them back on track to become healthier, more positive and strong?

- How are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children raised?

- What is the importance of family, extended family and community in the early years of life and when growing up?

Also of interest is the role that service use and support plays in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children:

- How can services and other types of support make a difference to the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children?

Study design and data collection methods

LSIC was designed to follow two age cohorts of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children, a group aged 6 months to 2 years (Baby or B cohort) and a group aged from 3 years and 6 months to 5 years (Kindergarten or K cohort) in Wave 1. In following two such groups, five waves of data provide information about children aged between 6 months and 9 years. From Wave 4, the ages of the two cohorts overlap allowing data users to combine the overlapping ages, enabling greater numbers of children to be analysed at that age range, and improving the statistical power of the data.

Each year, or wave, Indigenous interviewers, known as Research Administration Officers (RAOs), return to families to conduct a face-to-face computer-assisted personal interview with a primary carer known as Parent 1 (usually Mum), the study child themselves and, if possible, a "Parent 2" (Waves 1 and 2) or "Dad" (Waves 4 and 5). In Waves 1 and 2 the "Parent 2" survey could be completed by any family member who spent a lot of time with the study child, such as a grandparent or aunty but as the majority of responses were from fathers, it was redesigned as a "Dad" interview from Wave 4 (see Table 2).

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent 1 | 1,671 | 1,523 | 1,404 | 1,283 | 1,258 |

| Study child | 1,480 | 1,486 | 1,394 | 1,269 | 1,244 |

| Parent 2/Dads | 257 | 269 | - | 213 | 180 |

| Teacher/carer | 45 | 163 | 329 | 442 | 473 |

With Parent 1's permission, RAOs also liaise with schools, so that teachers may complete a paper-based or online questionnaire about the study child and school. RAOs are usually permanent DSS employees located where many of their interviews are conducted. They interview parents, carers and children, and engage with communities from February to December each year.

From Wave 4, a touch-screen computer was introduced so that the children in the study could select their own answers for assessments such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children and a variation of the Progressive Achievement Test - Reading (ACER, 2008). As the study children grow up, they are asked more of the questions and may eventually do a computer-assisted self-interview. From Wave 5, the computer has some questions recorded in English, Kriol, Torres Strait Creole and Djambarrpuyngu, one of the languages spoken in Galiwin'ku. In Wave 6, a variation of the Progressive Achievement Test - Mathematics (ACER, 2011) was introduced, and children could choose to hear the questions in their choice of one of the four recorded languages.

Where is Footprints in Time?

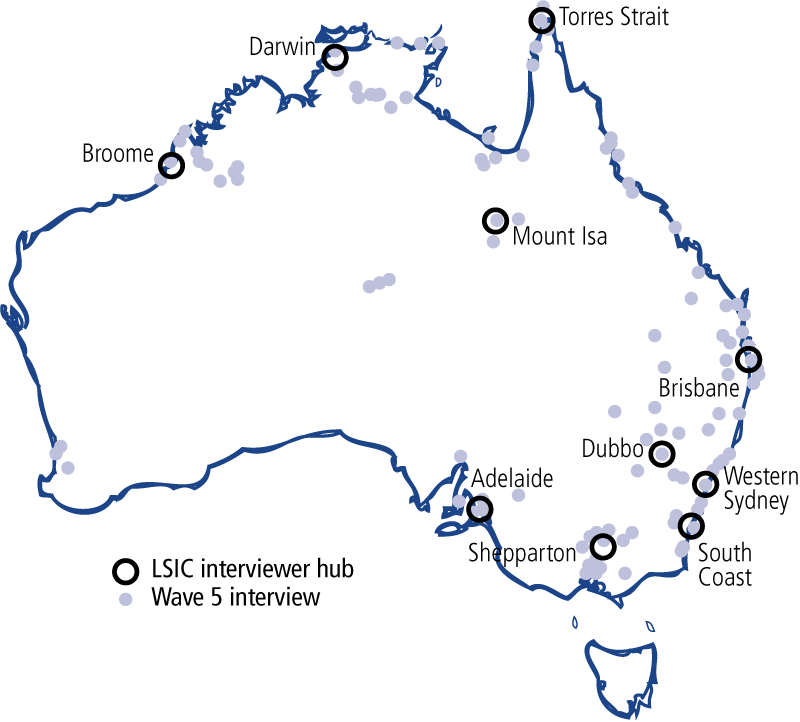

Figure 1 shows LSIC interviewer worksites as open circles and additional interviewing as dots. Although only 11 sites were chosen for the study, they mirror the distribution of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population across Australia reasonably well (Bennetts Kneebone, Christelow, Neuendorf, & Skelton, 2012).

Figure 1: Footprints in Time interviewing locations at Wave 5

Note: Alice Springs was an original site and Katherine was included later in the Wave 1 fieldwork period; neither have sufficient sample for a permanent interviewer but together they account for one site.

A study child (with her brother) growing up with Footprints in Time.

Sample recruitment and retention

The LSIC sample consists of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children born in 2006, 2007 and 2008 (B cohort) and 2003, 2004 and 2005 (K cohort) in selected sites. The majority of families in the study were recruited using addresses provided by Medicare Australia. Other informal means of contact, such as word of mouth, local knowledge and study promotion, were also used to supplement the number of children in the study (DSS, 2014).

More than 1,200 parents and carers have been interviewed in each wave of LSIC conducted to date. The initial LSIC Wave 1 sample consisted of 1671 Parent 1s, and an additional 88 joined the sample in Wave 2, so the total number of LSIC study children is 1,759 children. Table 3 shows that the study has had retention rates above 80% for the first five waves of the study. Data users may be interested in a balanced panel, or those who have been interviewed in every wave. There are 909 children whose Parent 1 has been interviewed in each of the first five waves. Not all respondents participate in every year of the study but many are keen to come back after skipping a wave or two.

| Wave | Total interviews | Previous wave respondents a | Additional interviews | Percentage of total sample (n = 1,759) | Retention from previous wave (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | 1,671 | ||||

| W2 | 1,523 | 1,435 | 88 b | 86.6 | 85.9 |

| W3 | 1,404 | 1,312 | 92 c | 79.8 | 86.2 |

| W4 | 1,283 | 1,150 | 133 c | 72.9 | 81.9 |

| W5 | 1,258 | 1,097 | 161 c | 71.5 | 85.5 |

Notes: a People interviewed in current wave who were also interviewed in the previous wave. b New entrants in Wave 2. c Interviewed in earlier wave but not the previous wave.

While retention becomes an issue of major importance to all longitudinal studies, loss of sample will inevitably occur, especially in early waves. Although Footprints in Time does not have a sample that is representative of Australian Indigenous children, it is still important to examine how the overall characteristics of the sample may be changing. Table 4 compares the proportions of Parent 1s and children with selected characteristics in Waves 1 and/or 2 with Wave 5. There is a relatively high level of participation among all groups but retention has been higher for children who, in Wave 1, lived in urban areas than for those living in moderate to extremely isolated areas. Parent 1s were more likely to be reinterviewed if they were partnered, had an education beyond Year 10 and/or were non-Indigenous.

| Characteristics | Entry wave a (%) | Wave 5 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Study child's Indigenous status | ||

| Aboriginal | 87.3 | 87.2 |

| Torres Strait Islander | 6.7 | 7.2 |

| Both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 6.0 | 5.6 |

| Child's sex | ||

| Male | 50.4 | 50.6 |

| Female | 49.6 | 49.4 |

| Child's mean age by cohort (Wave 1 only) | ||

| Younger cohort mean age in years | 1.3 | 5.1 |

| Older cohort mean age in years | 4.2 | 8 |

| Parent 1 is Indigenous | 85.8 | 82.5 |

| Parent 1 relationship to study child | ||

| Mother | 92.9 | 92.4 |

| Father | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Other relationship (step-parent, grandparent, other) | 5.0 | 5.4 |

| Parent 1 has a partner in the household | 55.5 | 59.3 |

| Parent 1 is employed | 29.8 | 39.6 |

| Household size: Mean number of people in the household | 5.0 | 5.1 |

| Parent 1 has post Year 10 education (Wave 2 and Wave 5) | 56.7 | 74.4 |

| Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) b | ||

| Lowest decile of relative advantage and disadvantage | 39.3 | 40.6 |

| Highest decile of relative advantage and disadvantage | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Index of Relative Indigenous Socio-Economic Outcomes (IRISEO) c | ||

| Lowest decile IRISEO | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Highest decile IRISEO | 3.4 | 4.8 |

| Level of relative isolation (LORI) | ||

| None (urban) | 24.6 | 28.4 |

| Low | 48.2 | 48.7 |

| Moderate/high/extreme | 27.2 | 23.0 |

| Number responding (1,671 W1 + 88 W2) | 1,759 | 1,258 |

Notes: a Includes both Waves 1 and 2 unless specified. b LSIC unit record data contains information for each of the four 2006 SEIFAs; however, the commonly used index of relative disadvantage included Indigeneity as one of the variables (ABS, 2006), so the index of relative advantage and disadvantage has been used here. c Compares only Indigenous people's socio-economic outcomes. Like SEIFA, the lower the decile, the greater the level of disadvantage (Biddle, 2009).

A wealth of data

As well as tracking developmental pathways and measuring change, longitudinal cohort data is valuable for building comprehensive information about each child, their families, their schools and their communities. Some Footprints in Time data is collected every year, such as life events, household composition, mobility, parent employment and child height and weight. Other measures, such as vocabulary, change as the children grow older and new areas of focus become relevant. For example, the Renfrew Word Finding Vocabulary Test (Renfrew, 1998) is asked in three consecutive waves and is then superseded by an adaptation of the Progressive Achievement Tests - (PAT) Reading (ACER, 2008), which increase in difficulty with the children's ages and deliver a scaled score that can be compared across waves. Some information is collected in one or two waves, such as the Stolen Generations questions, some is collected every second or third wave, such as social and emotional wellbeing and child support.

Building data about the same child over time allows a rich array of material to be considered; more than can be collected in cross-sectional interviews. Table 5 shows the variety of topics covered in each wave of the survey. The cumulative wealth of data allows disparate topics to be examined about the same group of children. So it is possible to look at financial stress and its impact on nutrition and dental health, for example, as well as considering parent education levels, birth weight, parent and child health conditions, whether the family eats dinner together and whether the child has eaten bush tucker the previous day.

| Domain | Topics | Waves asked |

|---|---|---|

| Household | Household demographics including sex, age, Indigenous status, relationship to Parent 1 | All waves |

| Maternal & child health | Antenatal health and care; alcohol, tobacco & substance use in pregnancy; birth, post-natal depression & treatment, breast feeding & weaning, home visits | Waves 1 & 2 |

| Child health (cont.) | Eaten yesterday; dental health; health conditions; hospitalisation; child's sleeping patterns; injury | All waves |

| Parent health | Health conditions; social and emotional wellbeing; parents living elsewhere | All waves |

| Parent wellbeing | Stolen Generations; social, personal, cultural resilience; smoking & alcohol; life satisfaction; gambling; parent values; parents' relationship | Some waves |

| Child wellbeing | Social and emotional development; parent concerns about language and development; physical abilities; child temperament | Most waves |

| Family wellbeing | Parental warmth, monitoring and consistency; parenting empowerment and efficacy; major life events | Some waves |

| Socio-demographics | Parental language, culture and religion; identity, racism, passing on culture; parent studying, education, work; paid parental leave; financial stress & income; if income managed; child support; housing repairs needed; mobility & why; community safety; homelessness | Some waves |

| Child care & education | Playgroup, child care, preschool & school attendance; how child gets to school & with whom, school liking & avoidance, being teased or picked on; peers & friends; parent assessment of literacy and numeracy skills; homework, tutoring, parent engagement with school | Most waves |

| Activities | Activities with whom & if in language: including reading, telling stories, art, housework, playing in & outdoors, television watching and rules, computers, electronic games, swimming, camping, religious services | Most waves |

| Open-ended questions | What the study child likes doing; parent & study child aspirations; cultural strengths. What is a good education for your child? What do you hope your child will learn or do next year? How will you teach your child how to deal with racism? | Some waves |

Working on Footprints in Time

Sharon Barnes is an Assistant Director with the Footprints in Time Community Engagement and Study Management team.

Sharon Barnes with an LSIC study child.

I have been with the study for just over 10 years. My role has changed many times over the years. In the first few years, I was liaising with our Elders, service providers, communities and other government departments to get advice on how to do a study like this. Then I moved into planning, testing, piloting, and recruiting Indigenous staff to implement the study. My role now is managing the fieldwork and the Indigenous staff that are employed in it. The Research Administration Officers (RAOs) are all outposted into the areas we live and work in; most of us are the only Indigenous staff located in our offices and, in one instance, the only person in an office. We travel extensively and usually alone for up to three weeks at a time. Some of us might only get a few days at home before we move onto the next location, enough time to get the mail, pay bills, and mow the lawn.

The study wouldn’t have succeeded without the commitment and dedication of all our staff, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. At the start we had a very small team of four; we covered all of Australia conducting Community meetings to work out how we could do this. We soon grew to 32 staff, mostly Indigenous, to be able to find the sample and complete Wave 1. This was great to see but was soon reduced to nine permanent Indigenous staff in the field, one Indigenous person located in National Office who roves around Australia and a contract Indigenous floating RAO, plus a team of non-Indigenous administration staff.

A trainer once said, “I love training LSIC because it is like coming home to family, everyone here, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, are like family.” His reference to this is that a lot of the staff have been with LSIC for years and so there is a strong bond between the staff. He stated, “This is why it works, many others have failed but LSIC is strong, family is strong.” Like most families we don’t always agree, but usually we find a way!

Most of us field workers have seen “interesting” things over the years. I love the fact that I have seen some families go from having nothing—just a near empty house and new-born baby—to now, 7 years on, they have a few more children, furniture, TV and even a lounge to sit on. On the flip side to this is the families that still have nothing, barely enough to feed their family and still so much disadvantage. Our hearts cry for these families and this is why we continue to stay strong, so our children, grandchildren and future families will hopefully not need to live the lives that so many of us have before this all started.

We try our best to have the same RAO visit the same family each year and that all interviews are conducted by us—the Indigenous staff. For the past three years all of the interviews have been completed by the Indigenous team. We have seen lots of tears and tantrums over the years and, for me personally, it is sometimes our LSIC families that pick us up and get us going again. I had one mum who was so worried about me that she made me a Koori guardian angel for my car. This hangs proudly off the rear vision mirror and I listen to her words when I am getting tired or lost in the despair that I sometimes see.

I have been asked to write about what my life is like, being a RAO—walking in two worlds—I changed this to walking in many worlds—I am Aboriginal, I am mother, I am Grandmother, I am daughter, I am sister, I am Auntie, I am Public Servant, I am “boss”, I am friend, I am community person, I am at times pulled across many, many different paths and it is hard to find which way at times, but we always need to “find our way” to hopefully make change, so our future generations can have better opportunities. This is why I do this; this is why I have stayed for so long, as I believe this study can make a change for the future.

A study child growing up with Footprints in Time.

Privileging the voices

Professors Karen Martin and Lester-Irabinna Rigney stress the need to privilege the voices, experiences and lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Martin, 2003). Footprints in Time data is collected from parents, carers and the children in structured interviews that include some verbatim or "free text" responses. These "free text" answers are confidentialised and released to data users who can use coding frames to look for themes in the responses or quote the responses themselves in publications, thereby ensuring Footprints in Time respondents have a voice in the research findings. References to places, individuals, employers, clans, family names and languages are suppressed to maintain confidentiality. Truncated versions are present in the data releases but full versions of confidentialised responses are available in Excel on request. Examples of free text questions are: What is it about Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander culture that will help (your child) grow up strong?; What do you do to cope with stress?; and What's the best thing about being the study child's Dad?

Box 1 shows some of the Parent 1 responses to "Are there family rules about television?". Parents and carers frequently mentioned their children are restricted to watching children's programmes only, have time limits or specific times for television watching or have to finish chores and homework before watching television.

Box 1: "Are there family rules about television?"

Selected parent/carer responses, Wave 4

- Take in turns on what they watch.

- Only that it goes off at 8.30.

- Yeah, dad drives the remote at all times.

- Has to go off at dinnertime.

- Only kids programs.

- No TV in the morning.

- Yes, the amount of hours is monitored, and they're not allowed to watch violence.

- Kids do not tell the adults what to watch.

- Can only watch an hour a day.

- Ask first.

- They can watch kids programs, then they do their homework.

Some researchers may wish to use the free text data by itself; others may find that combining coded answers with quantitative contextual information is valuable. By including some of the quantitative data, it is possible to further explore topics such as whether family rules about television vary by sex or age of the child, or even whether families in more remote areas have different types of rules to those in more urban areas.

Box 2 contains selected responses from teachers about how attendance is encouraged. Teachers frequently mentioned rewards and awards, making the classroom a fun place to be and the importance of good relationships with children's families.

Box 2: "What strategies do you or your school use to promote attendance?"

Selected teacher responses, Wave 4

- Creating a fun, welcoming, stimulating and SAFE environment. Talking to and making family connections.

- Certificates and home visits.

- Attendance records, follow up on children who are absent for three days in a row, use of attendance officer.

- Strong routines, engaging term-long themes (dinosaurs, space, minibeasts, etc.). Lots of hands on visual learning.

- A child who has poor attendance, I make in charge of feeding the pet.

- None needed.

- Having a fun, loving, caring classroom.

Professor Maggie Walter: LSIC/LSAC Conference keynote summary

Telling the stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families

My name is Maggie Walter, I am a descendant of the Trawlwoolway/Prelunnener people of Tebrekuna country in Tasmania. I am also a Professor of Sociology at the University of Tasmania. I joined the LSIC Steering Committee when the study was an unformed ambition. Now it is ground-breaking research. I tell my perspective of the journey from then till now in two integrally interlinked stories: the story of how LSIC does Indigenous research; and what LSIC is telling us about the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, and their families, across Australia.

Story 1: How LSIC undertakes Indigenous research

My first Steering Committee meeting was in August 2004, and a critical event took place at this meeting that has shaped LSIC from then till now. The Steering Committee, led by its Indigenous members, requested a redraft of the proposed study’s research questions. These new questions, we argued, needed to more directly reflect Indigenous realities and perspectives as well as the feedback from the community consultations, and to more clearly articulate the benefit of the study to the children and their families. This request and the Department’s willingness to listen and respond are what make LSIC unique in the long history of Aboriginal research in Australia. It encapsulates that at LSIC’s centre sits a purposive, ambitious and collaboratively built Indigenous research framework. This framework permeates LSIC’s research questions, design, data collection and analysis practices. Most critically, it links to the essential trust of our families that LSIC is research manifestly in the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people—because this trust is LSIC’s heart and soul.

This framework is evident in other key events. The Department’s initial data collection timeline was short. Again, the Steering Committee requested otherwise, arguing we could not proceed without the full engagement of families and their communities. The building of trust had to conform to what our families and communities regarded as the appropriate way to build such relationships. The minimal informing and consent processes common for non-Indigenous participant survey research were inconsistent with Indigenous values, and their deployment would likely render the research ineffective. LSIC required repeated community visits, ongoing contact with our families, the employment of local Indigenous interviewing staff, and a start date for data collection that built in these requirements. Again, the Department trusted the Steering Committee.

Story 2: What LSIC tells us about Indigenous families

LSIC is not a probability sample but collects data from families resident in 11 original sites. This means the data cannot be readily compared with that of non-Indigenous children but this is not a negative; dichotomous comparisons are not required to give them substance. What the LSIC cumulative data are revealing is a compelling, previously hidden, portrait of how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people “be” family and “do” raising children.

What is emerging confirms some of what we already know. Overwhelming evidence already shows that Indigenous children’s life circumstances are replete with hazards. And this is evident in the LSIC data. Our families and children are overburdened with life stressor events, attending way too many funerals, and experiencing too high levels of housing problems and financial stress. Our families also face accumulated intergenerational disadvantage. More than one third of LSIC primary parents have a Stolen Generations family member, and this factor is correlated with lower socio-economic and health outcomes for these families. Our families also continue to experience racism. In Wave 5, around 40% of the children’s Parent 1s from urban and regional areas reported experiencing a racist event in the past year. And 6% of the Parent 1s of K cohort children in Grades 2 and 3 reported that they know that their child has been bullied because they are Indigenous.

Yet, despite this adversity, our families do not see themselves, in the words of our Deputy Chair Karen Martin, on how Indigenous people are frequently portrayed in Australia, as “helpless, hopeless or useless”. The data reflect that our parents believe that they are doing a good job and have hope for their children’s future. LSIC families have clear value systems, rating tolerance and respect, followed by independence and responsibility, as the most important qualities children need to learn from home. Pride in identity, family history and showing respect are all considered to be key cultural aspects that need to be passed on to the child, by parents across urban, regional and remote areas.

And while NAPLAN results suggest many LSIC children may fall academically behind, our parents rate getting a good education as their number one aspiration for their child. Wave 5 data indicates around half of LSIC parents predict their child will go on to a post-school qualification, with a third predicting university completion. Other data show that the K cohort, now in the early primary school years, overwhelmingly like school and the reading, writing and numeracy that school brings. The quest of LSIC is to identify those factors, circumstances, services, interventions and investments that will allow this early hopefulness to be fulfilled.

Key findings from Footprints in Time

School attendance

Using Wave 3 of the Footprints in Time data, Biddle (2014) found that some of the variation in school attendance may be explained by the student's own view of school and the child's gender and health.

Indigenous vocabulary

Farrant, Shepherd, Walker, & Pearson (2014) has found that children who are told Indigenous oral stories have larger Indigenous language vocabularies than those who are learning language but did not hear a story in language in the week prior to interview.

English literacy

In multivariate models for both Waves 4 and 5 higher English reading scores were associated (p < .01) with strong vocabulary scores at the start of school, being a girl, being a Torres Strait Islander and living in urban areas or areas of low isolation (Skelton, Kikkawa, Balch, Bell, & Zubrick, 2013). Reading scores were also higher in Waves 4 and 5 for children who had a Parent 1 in the workforce (p < .05). Having rules about watching television was a predictor of better reading skills in Wave 5 (p < .05) but not in Wave 4.

Identity

LSIC children whose Parent 1s felt strongly about their Indigenous identity had fewer social, emotional and behavioural difficulties than the children of Parent 1s who did not have such strong Indigenous identities (Armstrong et al., 2012).

Health

Around two thirds (69%) of Parent 1s indicated that they had sleeping routines for their children (FaHCSIA, 2013). Children with bedtime routines tended to score higher on tests of readiness for school, reading and socio-emotional state.

Housing conditions such as need for repairs, housing problems and overcrowding were related to increased incidences of ear problems, skin infections and other health problems (FaHCSIA, 2013).

Indigenous languages

Around a quarter of the LSIC children are multilingual (compared with around one-eighth of LSAC children), and around 8% of the Footprints in Time children speak a traditional Indigenous language that has been classified as endangered or even extinct (Kikkawa, 2014). There is strong support from Parent 1s for the study children to learn Indigenous languages at school (McLeod, Verdon, & Bennetts Kneebone, 2014). More than 90% of Footprints in Time parents would like their child to learn an Indigenous language in school (DSS, in press).

Employment

Thompson and Tetley (2013) found that less educated Footprints in Time mothers were more likely to work if their partners were employed and/or better educated. More educated mothers were less likely to work if their partners did not work or/were less educated.

Racism

Parent 1s who experienced racism, discrimination or prejudice "every day", "every week" or "sometimes" (32% in total) were more likely to rate their general health as being lower than those who "only occasionally", or "never or hardly ever" experienced it and were more likely to experience depression (FaHCSIA, 2012).

Looking at teacher-rated literacy scores and Parent 1s' responses to the questions on racism shows that children in families who had experienced racism had an average literacy score that was five points lower (of a total possible score of 50) than those whose families had not experienced it (FaHCSIA, 2012).

Relationships and resilience

Footprints in Time Parent 1s with strong, supportive relationships and personal resilience have better social and emotional wellbeing scores than the Parent 1s who do not have such strong personal, social and cultural resilience. High Parent 1 resilience scores are also related to higher English reading scores for the children and to reduced social, emotional and behavioural difficulties (Skelton, 2014).

Disadvantage

Most indicators of disadvantage (such as low parent education, living in a jobless household, or living with a lone parent) are not significantly associated with increased social and emotional difficulties for Footprints in Time children; whereas they are for non-Indigenous children. (DSS, in press).

Major life events and LSIC children's wellbeing

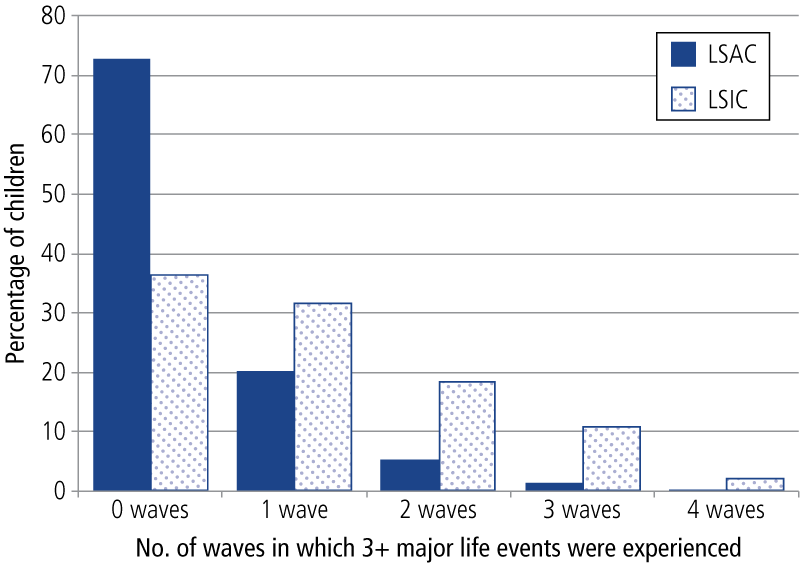

In both LSIC and LSAC participants were asked about the occurence of 12 types of life events in the 12 months prior to their interviews. Kikkawa, Bell, Shin, Rogers, and Skelton (2013) matched the results on these major life events and in both studies, children who experienced greater numbers of major life events had higher average social, emotional and behavioural difficulties scores, as measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionaire (SDQ) (DSS in press; for information about the SDQ see Goodman, 2012). The higher difficulties scores of the LSIC children when compared to the LSAC children seem to be largely explained by the experience of many more life events. Figure 2 shows the percentage of children in both studies whose families experienced three or more major life events in each of four waves.

Figure 2: Children experiencing three or more major life events in each of four waves

Major life events were associated with statistically significant changes in Parent 1s' social and emotional wellbeing between Waves 1 and 2 for 12 out of 15 events (Biddle, 2011). Having serious worries about money had the greatest negative association, followed by family split-ups and children being worried by family arguments.

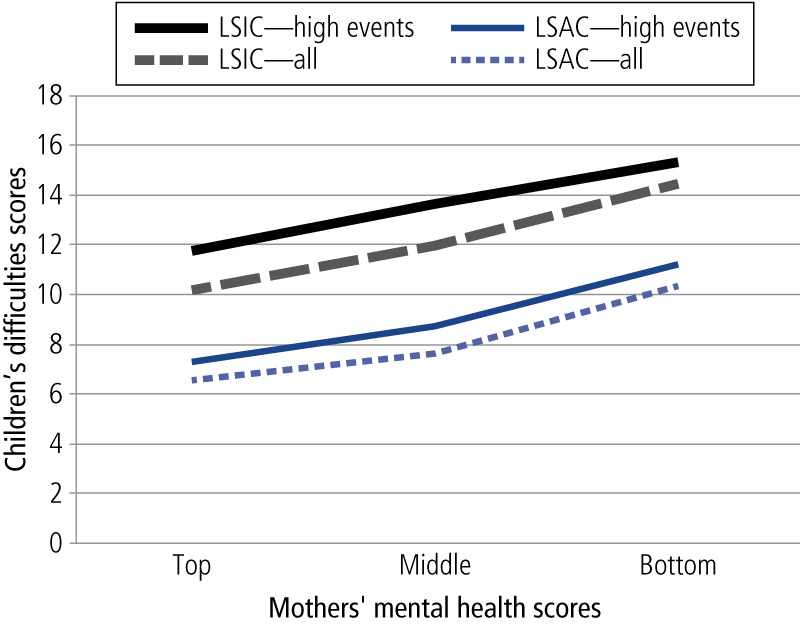

Figure 3 shows Parent 1s' mental health seems to be a protective factor for children's social and emotional development and acts as a buffer for those children experiencing multiple major life events (Kikkawa et al., 2013). Although good mental health by itself cannot overcome the negative effect of experiences or disadvantage, safeguarding parental mental health may provide a significant contribution to ensuring better social and emotional development outcomes for the child.

Figure 3: The effect of Parent 1s' mental health on children's SDQ difficulties scores

LSIC research administration officers 2012

Can LSIC data contribute to Indigenous children growing up strong?

At June 2014, five waves of Footprints in Time data were available to data users, Wave 6 data was in preparation, Wave 7 was in the field and Wave 8 in design. LSIC data is publically available to researchers and each release includes all waves of data from all respondents in STATA, SPSS or SAS along with a comprehensive data user guide, data dictionary and tabulation of frequencies for all variables. Prospective users can apply through an organisational or an individual license, both of which require data users to sign a deed of confidentiality, Footprints in Time data integrity statement, and to acknowledge their cultural standpoint.

LSIC and LSAC data users also deposit research in the Australian Government's Department of Social Services (DSS) longitudinal surveys electronic research archive, otherwise known as FLoSse (pronounced Flossie). FLoSse contains bibliographic details and often direct links or advice about how to obtain copies of publications and presentations <flosse.dss.gov.au>.

To find out how to join more than 160 researchers from government and academic backgrounds who have used or are using LSIC data go to <dss.gov.au/lsic>. DSS also publishes a report of findings from each wave and a community feedback booklet and site feedback sheets on this site. The reports provide an overview of the wave and feature articles about specific topics, including from contributing authors such as Katherine Thurber, who is published elsewhere in this journal.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA): Technical paper. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from <www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/2039.0.55.0012006?OpenDocument>.

- Australian Council for Educational Research. (2008). Progressive Achievement Tests in Reading (PAT-R) (4th Ed.) Melbourne: ACER Press.

- Australian Council for Educational Research. (2011). Progressive Achievement Tests in Mathematics Plus (PATMaths Plus). Melbourne: ACER Press.

- Armstrong, S., Buckley, S., Lonsdale, M., Milgate, G., Bennetts Kneebone, L., Cook, L. et al. (2012). Starting school: A strengths-based approach towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research. Retrieved from <research.acer.edu.au/indigenous_education/27/>.

- Bennetts Kneebone, L., Christelow, J., Neuendorf, A., & Skelton, F. (2012). Footprints in Time: The longitudinal study of Indigenous children: An overview. Family Matters, 91, 62-68.

- Biddle, N. (2009). Ranking regions: Revisiting an index of relative Indigenous socio-economic outcomes (CAEPR Working Paper No. 49). Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University. Retrieved from <caepr.anu.edu.au/Publications/WP/2009WP50.php>.

- Biddle, N. (2011). An exploratory analysis of the Longitudinal Survey of Indigenous Children (CAEPR, Working Paper No. 77). Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University. Retrieved from <caepr.anu.edu.au/Publications/WP/2011WP77.php>.

- Biddle, N. (2014). Developing a behavioural model of school attendance: Policy implications for Indigenous children and youth (CAEPR Working Paper No. 94) Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University. Retrieved from <caepr.anu.edu.au/Publications/WP/2014WP94.php>.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2009). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Key summary report from Wave 1. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2011). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Key summary report from Wave 2. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2012). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Key summary report from Wave 3. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2013). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Report from Wave 4. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Department of Social Services. (2014). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Wave 5 data user guide. Canberra: DSS.

- Department of Social Services. (in press). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Report from Wave 5. Canberra: DSS.

- Dodson, M., Hunter, B., & McKay, M. (2012). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children: A guide for the uninitiated. Family Matters, 91, 69-82.

- Farrant, B., Shepherd, C., Walker, R., & Pearson, G. (2014). Early vocabulary development of Australian Indigenous children: Identifying strengths. Child Development Research, 2014, Article ID 942817. Retrieved from <www.hindawi.com/journals/cdr/2014/942817/>.

- Goodman, R. (2012). SDQ: Scoring the SDQ. YouthinMind. Retrieved from <www.sdqinfo.org/py/sdqinfo/c0.py>

- Kikkawa, D. (2014, March). Turning back the tide of Indigenous language loss: Children to the rescue. Paper presented at the Breaking Barriers in Indigenous Research and Thinking: 50 Years On, National Indigenous Studies Conference, Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra.

- Kikkawa, D., Bell, S., Shin, H., Rogers, H., & Skelton, F. (2013, November). The impact of multiple major life events on children's social and emotional wellbeing. Paper presented at the Growing Up in Australia and Footprints in Time: LSAC and LSIC Research Conference, Melbourne.

- Martin, Karen L. (2003). Ways of knowing, ways of being and ways of doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous re-search and Indigenist research. Voicing Dissent, New Talents 21C: Next Generation Australian Studies. Journal of Australian Studies, 76, 203-214.

- McLeod, S., Verdon, S., & Bennetts Kneebone, L. (2014). Celebrating Indigenous Australian children's speech and language competence. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(2), 118-131.

- Renfrew, C. (1998). The Renfrew Language Scale: Word finding vocabulary test. Milton Keynes: Speechmark.

- Skelton, F. (2014, March). Strong relationships lead to better social and emotional wellbeing and learning outcomes in Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Paper presented at the Breaking Barriers in Indigenous Research and Thinking: 50 Years On, National Indigenous Studies Conference, Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra.

- Skelton, F., Kikkawa, D., Balch, S., Bell, S., & Zubrick, S. (2013, November). Learning to read English: What can we learn from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who are doing well? Paper presented at the Growing Up in Australia and Footprints in Time: LSAC and LSIC Research Conference, Melbourne.

- Thompson, J., & Tetley, F. (2013, November). Footprints in the Workplace: Indigenous mothers' employment. Paper presented at the Growing Up in Australia and Footprints in Time: LSAC and LSIC Research Conference, Melbourne.

- Thurber, K. A., Banks, E., & Banwell C. (2014). Cohort profile: Footprints in Time, the Australian Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. International Journal of Epidemiology, 1-12. Retrieved from <ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/07/09/ije.dyu122>.

Sharon Barnes is a Ngunnawal woman who has worked on Footprints in Time since its inception. Fiona Skelton and Deborah Kikkawa are non-Indigenous members of the Footprints in Time Data and Design team at the Department of Social Services (DSS). Maggie Walter is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Tasmania.

The photographs of children in this article are used with permission of parents and carers of the Footprints in Time children.

This paper uses unit record data from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC). LSIC was initiated and is funded and managed by the Australian Government Department of Social Services. The findings and views reported in this article, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to DSS or the Indigenous people and their communities involved in the study.

Skelton, F., Barnes, S., Kikkawa, D., & Walter, M. (2014). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children: Up and running. Family Matters, 95, 30-40.