Children in Australia

Harms and hopes

June 2015

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

In addressing child abuse and neglect in Australia, this article asks us to consider also the wider, broader harms that children are exposed to in our modern society - as part of the "packaged" nature of the problems in many troubled families. It discusses the need for child protection reform, the need for collaboration, population-based reform, and the contribution of children. This article is an edited transcript of the author's keynote address given at the 13th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference, 2014.

There are many harms to which children in Australia are exposed today. Many of us here would be concerned about harms such as children growing up in poverty; children of asylum seekers being held in detention; children being bullied at school; and, in some communities, children being poisoned by lead.

The harms that I will be exploring today are closer to home - child abuse and neglect - but I want us to take those other, broader harms with us in our thinking as we explore the "packaged" nature of the problems in many troubled families.

Historical background of child protection

Child abuse and neglect is not new, it's been known across cultures and across time, but in Western society, it was in the 19th century that a societal response emerged in relation to this issue (Scott & Swain, 2002).

Scott and Swain (2002) described how this was the time of the first child cruelty legislation in Australia, but long before this, children had been in institutional care in this country. Child cruelty was the term used for child physical abuse by "the child savers" - as they called themselves - in the child rescue movement. They also knew about child sexual abuse. However, the vast majority of the children they encountered suffered from neglect and destitution in the context of extreme poverty. This is why most of the children entered institutional state care or, more likely, especially in Victoria, entered institutions run by churches. The state was actually a most reluctant guardian as it was not seen as the role of the state to violate the privacy of the family or to assume responsibility for children when parents were unwilling or unable to do so.

By the mid-20th century it was very different. There was a welfare safety net that prevented the type of destitution that had occurred in the greatest economic depression of this nation in the 1890s. The 1960s saw the beginning of the de-institutionalisation of child welfare by some of the churches. This was also the time of the discovery - in fact, it was the rediscovery - of child physical abuse. Radiological surveys identified previously undetected fractures in young children, and the term "the battered baby syndrome" emerged to describe child physical abuse by parents. By the late 1970s, in the wake of second-wave feminism, child sexual abuse was rediscovered. And in this era a massive growth in the role of the state occurred, not just as the guardian of children but also as the investigator of children who might be at risk. This was a broad and vague notion. And as time has gone on, the breadth of issues around which children we think might be at risk has grown exponentially (Scott & Swain, 2002).

We know a lot more about child abuse and neglect now than we knew even a generation ago. It remains true that "maltreatment is one of the biggest paediatric public health challenges, yet any research activity is dwarfed by work on more established childhood ills" (Horton, 2003, p. 443). We know a lot more about the prevalence, incidence and etiology of child abuse and neglect, but we still know little about prevention. That is beginning to change.

We also have a framework of values to guide us, which we once did not have. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child enshrines a child's right to provision in terms of the basic necessities of life, protection from exploitation and abuse, and participation. The right to participation usually refers to children and young people being involved in decisions affecting them, but as I will argue later, the right to participation can and should go far beyond that.

From an historical perspective, there have been two grand ideas - two inspiring ideas - unfolding and gathering momentum over a century. One is the notion of the child as a holder of human rights. The other is the notion of the child as an emotional being. This has led to the recognition of the risk of psychological harm that might be caused by a broad range of situations that were once not deemed as child abuse or neglect. Examples of this are children witnessing family violence, the use of harsh physical discipline, and young children being left in the care of an older child. These two grand ideas have paradoxically brought our statutory child protection systems to breaking point in many Western societies.

Child maltreatment in Australia today

We need to change our response to the problem of child abuse and neglect for four important reasons. The first reason is because child maltreatment is a high prevalence and high incidence problem. The second reason is because it causes intense suffering to children and may cause serious long-term harm. The third reason is because our current child protection systems are overwhelmed. And the fourth reason, rarely acknowledged, is because our current systems have the capacity to harm vulnerable children.

Let us briefly explore each of these reasons for reform.

Prevalence and incidence of child abuse

The Australian prevalence estimates, based on a range of studies summarised by Price-Robertson, Bromfield, and Vassallo (2010), are deeply concerning:

- child physical abuse: 5-10% of adults;

- penetrative child sexual abuse: 4-8% of males and 7-12% of females; and

- witnessing domestic violence: 12-23% of children.

The child physical abuse and the penetrative child sexual abuse prevalence estimates come from adults responding to surveys seeking information on their childhood experiences. The estimates on children witnessing family violence come from parents responding to questions about recent events in their households.

The incidence data are also deeply concerning. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW; 2014) reports that in the year 2012-13, Australian statutory child protection services recorded a total of 53,666 substantiated cases involving over 40,000 children. This represents a 29% increase in two years. Four primary abuse types were identified in these data (see Table 1).

| Primary abuse type | Reports (%) |

|---|---|

| Note: Percentages do not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding. Source: AIHW (2014), p.10 | |

| Emotional abuse | 38 |

| Neglect | 28 |

| Physical abuse | 20 |

| Sexual abuse | 13 |

It should be noted that these were the primary abuse types identified, but very often different types of child maltreatment co-exist. Furthermore, they should not be taken as a reflection of the prevalence of these problems in the community. Incidence data (that is, on reported cases) are often very different from prevalence data (the actual extent of a problem in the community, whether reported or not).

Effects of child abuse and neglect

We know that the long-term effects of child maltreatment can be profound. And while a lot of media attention is given to acts of commission, such as child physical abuse and sexual abuse, it is important to recognise the effects of problems such as severe neglect or witnessing family violence. There is now powerful research on the association between childhood adversity (including abuse and neglect) and long-term adult physical health and mental health problems, especially problems such as alcoholism and attempted suicide. Felitti and Anda (2010) noted that such childhood experiences include:

- parental substance abuse;

- parental separation/divorce;

- parental mental illness;

- battered mother;

- parental criminal behaviour;

- psychological, physical or sexual abuse; and

- emotional or physical neglect.

As the number of these factors in a child's life increases, the risk of poor adult physical and mental health increases dramatically. Felitti and Anda (2010) concluded that "these findings provide a credible basis for a new paradigm of medical, public health and social services practice. Many of our most intractable public health problems are the result of compensatory behaviours such as smoking, over-eating and alcohol and drug use, which provide partial relief from the emotional problems caused by traumatic childhood experiences" (p. 86).

Overwhelmed child protection systems

By the age of 18, 1 in 4.2 children in Queensland (and 1 in 1.6 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children) are "known to child protection"; that is, have been reported to child protection authorities (Carmody, 2013). In New South Wales, more than 1 in 4 children are known to child protection authorities by the age of 18 (Zhou, 2010). The projection for Victoria is that 1 in 4 children born in 2011 will be notified to the Child Protection Service by the time they end adolescence (Cummins, Scott, & Scales, 2012). There is no child protection system in the world that can respond to demand pressures of this magnitude.

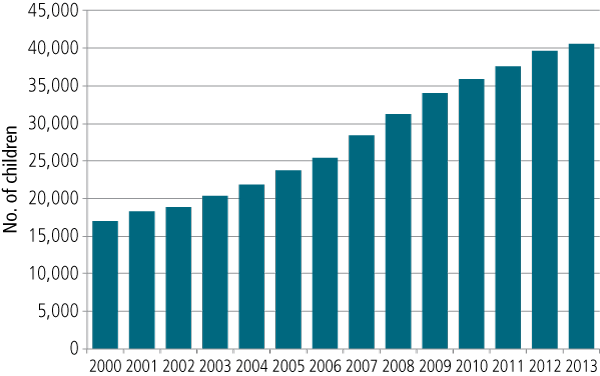

This is the result of three decades of policies based on the mantra "identify and notify". It is not just the number of reports of suspected child maltreatment. The number of children in out-of-home care has also increased markedly. Figure 1 shows the number of children in care on 30 June in the years 2000 to 2013. The total number of children in care in any given year is greater than that on 30 June and is not known.

Figure 1: Number of children in out-of-home care on 30 June each year from 2000 to 2013

Note: These data have been compiled from a range of sources from the AIHW.

As can be seen, in a decade, the number of children in out-of-home care has doubled. There were over 40,000 in state care on 30 June 2013, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children more than ten times over-represented. The major reason for this increase is not that we are bringing more children into care each year than are leaving care - the major drivers are that children are coming into care at a much younger age than previously and staying in care longer.

"First do no further harm …"

There is no Australian research to date that identifies the effects on children of coming into state care. Given the ethical and legal issues involved, this is not a field in which randomised control trials can be conducted. There is US research, however, which raises deep concerns about the potential of child protection intervention to cause significant harm to children. In a data linkage study of 45,000 Illinois child protection cases, school-aged children at similar risk levels were compared in regard to whether they had been placed in foster care or allowed to remain with their families. Children on the "margin of placement" who remained at home had lower adult arrest rates, lower teen pregnancy rates and better employment than children of similar risk levels placed in foster care (Doyle, 2007).

Why might coming into care and/or being in care be harmful? One reason is the level of placement instability to which they are exposed. Rubin, O'Reilly, Luan, and Localio (2007) followed 729 children for the first 18 months in foster care and found a high level of placement instability. This was strongly associated with a child's behavioural problems at 18 months, regardless of the level of behavioural problems on entering care. High levels of placement instability pose a serious risk of iatrogenic emotional abuse and psychological harm.

The most recent Australian data on placement instability are worrying. They come from the recent Queensland Child Protection Commission of Inquiry and show that this serious problem is getting worse. There is no reason to believe that placement instability is different in other Australian jurisdictions. In Queensland, of those children exiting care after five or more years between 2004 and 2012:

- those having six or more placements increased from 27% to 34%;

- those having three to five placements increased from 29% to 36%; and

- those having one to two placements decreased from 44% to 31% (Carmody, 2013).

I would like you to think about a child you love and imagine what three or four or five or six placements would do to that child. I have seen children corroded to the very core of their being as a result of multiple placements. Their capacity to trust, their capacity to love, their capacity to be loved - the very essence of their humanity - is deeply damaged, often forever. This is iatrogenic emotional abuse on a massive scale, for every day in this country hundreds of children experience a change in their placement.

We need to do all we can to prevent children coming into care. We need to do all we can to return children safely to their families after being in care. Where that is not possible, we need to do all we can to ensure a permanent arrangement, ideally within the child's extended family, but if not, a permanent family environment beyond the extended family.

The history of child welfare is paved with the pain of children and parents; the Stolen Generations, the Forgotten Australians, the British child migrants, and those affected by forced adoption policies. Why is it always a generation later that we begin to hear of that? Perhaps placement instability is the greatest harm to which children are currently being exposed.

From harms to hopes

To transform the way in which we respond to child abuse and neglect, we need to have a shared understanding of the problem:

The challenge of ending child abuse is the challenge of breaking the link between adults' problems and children's pain. (UNICEF, 2008)

What are these adult problems that cause children's pain? Delfabbro, Kettler, McCormick, and Fernandez (2012) presented the following data on the characteristics of parents of children entering state care for the first time in 2005:

- parental substance abuse, 69%;

- domestic violence, 65%; and

- parental mental health problems, 63%.

They add up to more than 100% because they often co-exist. It is these "packaged problems" of parents that are causing children's pain. They are not just "personal problems". Such problems occur mostly, but certainly not always, in a context of economic and social disadvantage. And in the context of growing social inequality, we need to confront this.

In the Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry that Justice Philip Cummins, Mr Bill Scales and I conducted in Victoria in 2011, we found strong data on the correlation between three factors: local government areas with high levels of social disadvantage; high numbers of child protection reports and substantiated cases; and the number of children identified as vulnerable on one or more domains of the Australian Early Development Index.

Across Australian jurisdictions there are highly fragmented and "siloed" service systems that can't respond easily to "packaged problems". It is largely organised around single input services based on categorical funding such that families with multiple and complex needs end up involved with a large number of organisations, and a revolving door of referrals. This is very alienating to families, it is very costly and it is largely ineffective.

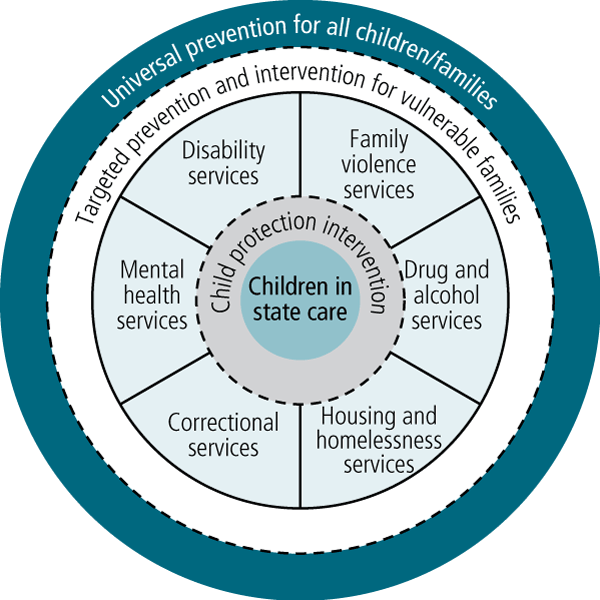

Some progress has been made toward the vision of a more integrated service system, as depicted in Figure 2. We have broadened and deepened the capacity of some of our universal services - maternal and child health nurses, midwives, early childhood education and care, and some schools - to be more responsive to vulnerable children and their families. A big challenge remains in relation to general practitioners. Moreover, we now have much better targeted services for vulnerable children and their families, and initiatives like the Australian Government's Communities for Children,1 which can strengthen that infrastructure.

But still, far too often, in order to get the services that families need, families with multiple and complex needs have to go through the highly stigmatising, humiliating and fear-inducing door of statutory child protection. We must not make families go through that door to get the services they require.

Figure 2: Toward a more integrated service system for vulnerable families

However, we need to go further than reconfiguring our children's services. We need to bring on board the services that can address the adult problems that cause the children's pain. Some of these services are named in Figure 2 - adult disability (mostly relating to parental intellectual disability), family violence, drug and alcohol, housing and homelessness, correctional, and mental health services.

There are others that could have been added, such as problem gambling services, veterans' affairs (especially for recent ex-servicemen and women with post-traumatic stress disorders), and refugee resettlement services. There are, indeed, many adult specialist services that need to be able to bring into their thinking and service delivery the needs of children and whole families.

The encouraging development is that in every one of those sectors, we have some excellent exemplars of adult specialist services broadening their focus so that they are inclusive of children and the whole family. The problem is that so often they are isolated and unsustainable exemplars.

The key implications of this analysis are that we need to broaden service provider roles so that they can offer relationship-based, evidence-informed, comprehensive and family-centred responses to a much broader range of needs in families. We need to provide the workforce development and secondary consultation to equip those service providers to do that. And we need to improve inter-agency collaboration and effective referrals where, and only where, multiple services are really required.

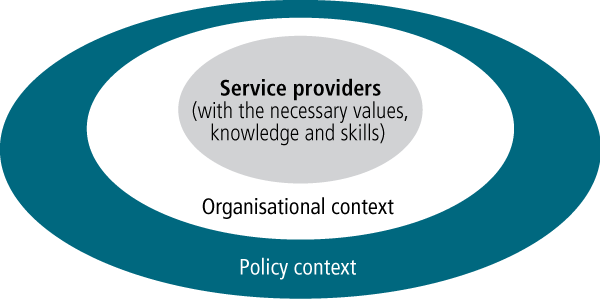

This is a three-level reform agenda (see Figure 3). It can't be done solely through workforce development by trying to equip the service providers to work with vulnerable families. It can only be done if it is embedded within an organisational context in which the culture, the climate and the leadership mandates it; otherwise it will die as soon as that service provider ceases to work. The culture is critical - it needs organisations that are committed to something more than their own survival, to a vision that is bigger than themselves. This is becoming harder to find, even among not-for-profit organisations that are ostensibly "mission-led".

Figure 3: The three levels of service reform required by service providers

Similarly, it can only be embedded within organisations when they are supported by policy settings, performance indicators and funding models that authorise and facilitate integrated responses to families with multiple and complex needs.

Some promising approaches

We have some really promising approaches. At the program level is Parents Under Pressure,2 developed by Paul Harnett and Sharon Dawe, psychologists from the University of Queensland and Griffith University respectively. It has a very distinctive combination of elements: evidence-informed, family-centred, home-based, and addressing parental substance misuse and mental health, as well as child development and the parent-child relationship. In the UK, it is now subject to a large randomised controlled trial and it is one of the very few programs subject to a randomised controlled trial here in Australia.

At the inter-organisational level, a promising approach is Services Connect,3 an initiative of the Department of Health and Human Services in Victoria, which uses one key worker to work with families whose needs cut across the parts of that department around housing, disability and child welfare.

At the policy level is Child Aware,4 an initiative funded by the Department of Social Services under the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children, being led by Families Australia and the Australian Centre for Child Protection. It is working in sites of high social disadvantage to bring together adult specialist services and children services, and builds on the capacity of all of those services to "think child, think family". This is further developing what was previously done by the Australian Centre for Child Protection in 12 sites across Australia under the Protecting and Nurturing Children Program: Building Capacity, Building Bridges.

Lastly, and on a larger level, is Collective Impact,5 a US-based approach now being implemented in several places in Australia, which uses strong collaborative approaches by key stakeholders to deal with deep and complex social problems. Essential elements in this approach are the shared use of agreed measures to assess progress, and processes that facilitate collaboration.

The need for collaboration

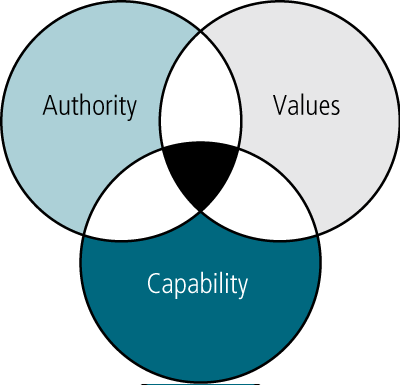

Collaboration across professional, organisational and sectoral boundaries remains a major challenge. What do we need for collaboration to happen? The recent work of White and Winkworth (2012) is particularly helpful in this regard (see Figure 4). There are three categories of pre-conditions for effective and sustainable collaboration: the authorising environment (the mandate to collaborate, or "what we may do"), a shared vision and values ("what we should do" together), and organisational capability (the practical capacity to do it, or "what we can do").

Figure 4: White and Winkworth's rubric for inter-agency collaboration

Source: White & Winkworth (2012)

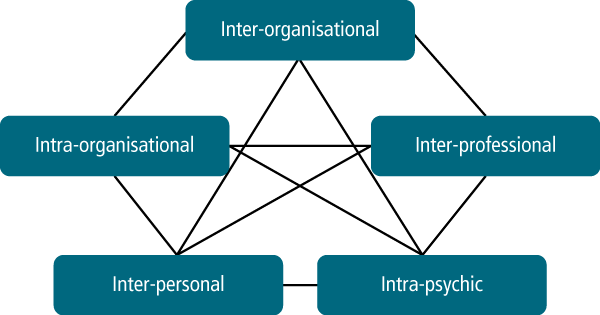

We also need to understand what brings collaboration undone. In my child protection research I found that there were five different but interrelated possible sources of conflict that can occur across organisational boundaries (see Figure 5). The levels of analysis of inter-agency conflict range from the inter-organisational or the structural (e.g., tensions that result from demand pressures and resulting "gatekeeping") right through to the intra-psychic. In the latter, defence mechanisms such as projection and displacement occur when service providers falsely see other organisations as having the magic wand to protect a child, which they lack. Unless we diagnose these sources of inter-agency conflict, we will not be able to address them. Conflict that has its primary source at one level of analysis - for example, at the inter-organisational level - can lead to problems at another level, such as the interpersonal. A negative feedback loop thus creates a narrative of inter-agency conflict that often endures.

Figure 5: The five sources of conflict between service organisations

Source: Scott (2005)

Population-based reform

Complex social problems cannot be solved solely by services or the reconfiguration of service systems. They require population-based measures that tackle the key risk and protective factors associated with child and family wellbeing. The common risk factors and the common protective factors cut across a range of problems, from low birth weight to school failure, to child abuse and neglect, to juvenile crime.

Let us use one risk factor and one protective factor to illustrate. Parental alcohol misuse is a key risk factor, associated with approximately 70% of children entering out-of-home care. Perhaps most concerning is the inter-generational effects of foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, leading to greatly impaired parenting capacity due to poor impulse control and cognitive deficits.

The evidence is strong - measures such as volumetric taxing, minimum pricing, restrictive advertising and licensing reform can reduce alcohol misuse at a population level (Australian National Council on Drugs [ANCD], 2013). Given the vested interests that oppose such measures, we will need to mobilise the community to support reform on "Big Booze", as was done in relation to "Big Tobacco".

Would it be possible to tackle a key protective factor in a population-based preventive strategy? The evidence is not as strong as with alcohol abuse, but perhaps the arguably most powerful protective factor of all - a parent's deep attachment to their child - is modifiable. Most of us, without thinking, would lay down our lives for our children. In fact, many adults instinctively do this for children who are complete strangers to them.

A study by Boukydis (2006) suggests it is worth trying. Using an ultrasound consultation with a pregnant couple on a routine antenatal visit to help them individualise their unborn child resulted in stronger parental attachment post-birth. If further studies supported such a finding, might we teach midwives and obstetricians to add this psycho-educational intervention of a few minutes' duration to routine ultrasound consultations?

And what would it look like if we avoided threats to maternal and paternal attachment during pregnancy and immediately after birth? Have we considered whether the now increasingly common pre-birth notifications to child protection could possibly raise the level of cortisol in a pregnant woman's bloodstream and directly affect her unborn child? Have we considered that the mother's fear of the child being removed at birth may inhibit her attachment to her unborn child? What if some of our current practices, in the name of protecting children, are actually diminishing parental attachment? To introduce such policies as pre-birth notifications and not undertake research on their intended and possible unintended consequences is unethical.

Another study by Strathearn, Mamum, Najman, and O'Callaghan (2009) in Queensland found breastfeeding was a protective factor in relation to substantiated physical abuse by mothers. If further research supported this, might this too be an area for primary prevention of child abuse?

Children as contributors

What might it look like if we took a public health strategy to addressing the full range of risk factors and protective factors at a population level? Can we think about prevention in ways that go beyond modifying parental behaviour? Is there anything that we might do on a population basis that could directly affect children's resilience? That is, can we go beyond talking about children as objects of concern in our child protection dialogue and consider children as active agents?

There is a body of well-established research on the importance of required helpfulness in increasing childhood resilience that has been virtually ignored, despite the fact that we now have a whole industry on resilience-based practice. Elder's (1974) classic sociology work, Children of the Great Depression, provided a re-analysis of the data from the early landmark longitudinal studies of the 1920s in the USA. Elder found that older children (adolescents) were not adversely affected by their families losing more than a third of their income. He explained this in terms of the older children and adolescents acquiring roles that made them contributors in their family. Elder's much later 1995 study on the Iowa farm crisis in the 1980s and 1990s had a similar finding. The children who adjusted well, compared with those who did not, were "contributors" in their families.

The Werner and Smith (1992) classic study, Overcoming the Odds, identified the key factors relating to resilience among children growing up in adversity. One was an active engagement in acts of developmentally appropriate "required helpfulness" in middle childhood and adolescence.

Why have we ignored such research? Is it because as a society, we have reduced children to being consumers and clients and have ceased to consider them as contributors? Think about your own family over three generations. In most families, especially working-class families, children were contributors.

I believe that understanding the role of children as contributors, and how it might relate to their sense of efficacy and agency and their sense of belonging, is an untapped resource.

There are many unanswered questions. We don't even know the extent of children's current contribution to the wellbeing of others in their families, in their schools and in their communities. We don't know how gender, class and culture might shape their role as contributors. Nor do we know how it changes in the transition into adolescence. Nor the degree to which intrinsic or extrinsic rewards might shape such behaviour. We don't know how being a contributor might work, especially for children who are not prosocial.

There is so much we do not know, but across this country there are many wonderful exemplars of children doing things for others and being valued for that. For example, in my semi-rural community there are primary school-aged children working to save an endangered species, the Helmeted Honeyeater, the avian emblem of Victoria. I observe the children deriving great joy and satisfaction from doing this.

Rutter (1983), the eminent child psychiatrist, said that it seems:

desirable that we foster personality development in such a way that our children are cooperative and prosocial … not because they feel they have to be so, but rather because they get pleasure from being so. (p. 38)

What if we were to start with a national study, with children as co-investigators, on what children do that is contributing to their families, their schools and their communities, and what they enjoy about doing this? And what if children in every community were to present this to their parents, their teachers and communities? And what if the aggregate findings, were to be presented to the prime minister? That way we could hear children's vision of Australia and their place in it, based not on the cliché that they are the citizens of tomorrow but because they are the citizens of today.

Adam Phillips, the British psychoanalyst, and Barbara Taylor, historian, in their beautiful little book called On Kindness (2009) said:

The child needs the adult and his wider society to help him keep faith with his kindness. That is to help him discover and enjoy the pleasures of caring for others. The child who has failed in this regard is robbed of one of the greatest sources of human happiness. (pp. 9-12)

Are we robbing our children of one of the greatest sources of human happiness, and possibly one of the greatest sources of resilience?

So what is our shared vision? Can we go beyond 19th century "child rescue", 20th century "child welfare", and early 21st century "child protection"? Can we commit ourselves to a child wellbeing movement based on a public health understanding of prevention, and on an understanding of children's rights that includes the right to participate as contributors?

Endnotes

1 For more information, see the Department of Social Services Family and Children's Services web page at: <www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/families-and-children/programs-services/family-support-program/family-and-children-s-services>.

2 For more information, see the Parents Under Pressure website: <www.pupprogram.net.au>.

3 For more information, see the Victorian Department of Human Services website: <www.dhs.vic.gov.au>.

4 For more information, see the Families Australia website: <www.familiesaustralia.org.au>

5 For more information, see the website for Collective Impact at: <www.collectiveimpactaustralia.com>.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2014). Child protection Australia. Canberra: AIHW.

- Australian National Council on Drugs. (2013). Alcohol Action Plan issues paper. Canberra: ANCD.

- Boukydis. Z. (2006). Ultrasound consultation to reduce risk and increase resilience in pregnancy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 268-271.

- Cummins, P., Scott, D., & Scales, W. (2012). Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry report. Melbourne: Department of Premier and Cabinet, Victoria.

- Dawe, S., Frye, S., Best, D., Moss, D., Atkinson, J., Evans, C., et al. (2006). Drug use in the family: Impacts and implications for children. Canberra: Australian National Council on Drugs.

- Delfabbro, P., Kettler, L., McCormick, J., & Fernandez, E. (2012, 26 July). The nature and predictors of reunification in Australian out-of-home care. Paper presented at the 12th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference: Family transitions and trajectories, Melbourne.

- Doyle, J. J. Jr. (2007). Child protection and child outcomes: Measuring the effects of foster care. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1583-1610.

- Elder, G. H. Jr. (1974). Children of the Great Depression: Social change in life experiences. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Elder, G. H. Jr. (1995). Life trajectories in changing societies. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in changing societies (pp. 46-68). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

- Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2010). The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health, well-being, social functioning and healthcare. In R. Lanius, & E. Vermetten (Eds.), The hidden epidemic: The impact of early life trauma on health and disease. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Horton, R. (2003). The neglect of child neglect: Editorial. The Lancet, 361, 443.

- Phillips, A., & Taylor, B. (2009). On kindness. London: Penguin

- Price-Robertson, R., Bromfield, L., & Vassallo, S. (2010, 7-9 July). What is the prevalence of child abuse and neglect in Australia? A review of the evidence. Paper presented at the 11th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference, Melbourne.

- Rubin, D., O'Reilly, A., Luan, X., & Localio, R. (2007). The impact of placement instability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics, 119, 336-344.

- Rutter, M. (1983). A measure of our values: Goals and dilemmas in the upbringing of children (Swarthmore Lecture). London: Quaker Home Service.

- Scott, D., & Swain, S. (2002) Confronting cruelty: Historical perspectives on child protection. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Scott, D. (2005). Inter-organisational collaboration: A framework for analysis and action. Australian Social Work, 58(2), 132-141.

- Strathearn, L., Mamum, A., Najman, J., & O'Callaghan, M. (2009). Does breastfeeding protect against substantiated child abuse and neglect? A 15 year study. Pediatrics, 123, 483-493.

- UNICEF. (2008). A league table of child maltreatment deaths in rich nations. Florence: UNICEF.

- Werner, E., & Smith, R. (1992). Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

- White, M., & Winkworth. G. (2012). A rubric for building effective collaboration: Creating and sustaining multi-service partnerships to improve outcomes for clients. Concepts paper. Melbourne: Australian Catholic University.

- Zhou, A. (2010). Estimate of NSW children involved in the child welfare system. Sydney: NSW Department of Community Services.

Professor Dorothy Scott OAM is Emeritus Professor at the Australian Centre for Child Protection, University of South Australia, and Director of Bracton Consulting Services. This is an edited transcript of her keynote address at the 13th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference: Families in a Rapidly Changing World, Melbourne, 31 July 2014.

Scott, D. (2015). Children in Australia: Harms and hopes. Family Matters, 96, 14-22.