Marriage, cohabitation and mental health

June 2015

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Research consistently shows that married people have better mental health than single people do. However, the research is unclear on whether marriage causes improvements in mental health or whether people with better mental health are more likely to marry, and whether the benefits of marriage extend equally to wives and husbands and also to non-marital relationships such as cohabitation. This article looks at findings from a new U.S. study that seeks to explore these questions: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health).

Research consistently shows that married people have better mental health, on average, than do single people. This general conclusion applies to a range of outcomes, including depression (Brown, 2000; Ross, 1995), happiness (Zimmerman & Easterlin, 2006), life satisfaction (Williams, 2003), psychological wellbeing (Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005) and mortality from suicide (Rogers, 1995). Moreover, the marriage advantage has been demonstrated in a variety of countries and regions, including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Europe and Asia (Diener, Gohm, Suh, & Oishi, 2000; Lee & Ono, 2012; Soons & Kalmijn, 2009).

Compelling reasons exist for why marriage might be good for people's mental health. First, marriage is an important source of companionship, intimacy and social support (Waite & Gallagher, 2000). Marriage also connects spouses with one another's social networks, thus expanding the number of people who can be drawn on for assistance. Second, people benefit from the institutional nature of marriage (Cherlin, 2004). Marriage involves social norms and expectations that clarify spouses' rights and responsibilities toward one another and reduce relationship ambiguity. Moreover, through marriage, people achieve a positively valued social status that other people respect and support. And because marriage is institutionalised, spouses acquire many legal benefits. In the United States, for example, these benefits include access to the spouse's health insurance, tax deductions for one's spouse, the option to file joint tax returns and the right to make medical decisions for one's spouse. Third, the long-term commitment implied by marriage reduces relationship insecurity, and the gradual accumulation of a shared history with one's spouse is a source of meaning and identity to many people. Fourth, marriage provides financial advantages over singlehood, including economies of scale and the ability to pool income and accumulate wealth more rapidly.

Despite the consistency of research findings, several points of ambiguity remain in this research literature. It is not clear whether:

- the association between marriage and mental health is causal or due to the self-selection of healthier people into marriage;

- the benefits of marriage persist indefinitely or fade over time;

- the benefits of marriage extend equally to wives and husbands; and

- the benefits of marriage apply to other types of romantic relationships, such as non-marital cohabitation.

These ambiguities in the research literature led me to initiate a program of research on the effects of marriage and other relationship transitions on people's mental and physical health. The research described in this article involves one part of that larger program. The current report draws on a large, longitudinal dataset in the United States - the National Survey of Adolescent to Adult Health - and addresses how the transition to cohabitation and marriage affects men's and women's reports of depressive symptoms and thoughts of suicide.

Does marriage cause changes in mental health?

Because people do not marry at random, it is difficult to determine whether marriage improves people's mental health (a causal hypothesis), or whether people with better mental health are more likely to marry (a selection hypothesis). Given the impossibility of conducting experiments, fixed effects models are arguably the best available method to control for selection effects when using correlational, longitudinal data (Allison, 2009). An advantage of fixed effects models is that they control for all unmeasured, time-invariant features of people, such as race and ethnicity, stable personality traits, cognitive ability, family of origin characteristics and many genetic factors. Because fixed effects models involve only within-person variation, each person serves as his or her own "control". Applied to the current topic, this method answers the question: Does people's mental health improve after they marry?

Four studies have used fixed effects models to estimate the effects of marriage on health. Zimmerman and Easterlin (2006) found that marriage was followed by an increase in life satisfaction in a 20-year longitudinal German dataset. They observed a similar but weaker effect for non-marital cohabitation. Although life satisfaction declined modestly after the first year of marriage, it remained higher than it had been during the single years. Soons, Liefbroer, and Kalmijn (2009) reached nearly identical conclusions using an 18-year longitudinal dataset from the Netherlands. In the United States, Musick and Bumpass (2012) found that transitions into marriage between the first two waves of the National Survey of Families and Households were associated with increases in happiness and declines in depression, provided that couples did not divorce. These changes were modest in magnitude, however, and tended to dissipate over time. In contrast, Wu and Hart (2002) did not find that marriage between the first two waves of the Canadian National Population Health Survey was associated with changes in depression. They did note, however, that the longer people stayed married, the more depressed they became.

In summary, three of the four studies that have used fixed effects models suggest that marriage has a positive, causal effect on several dimensions of mental health, including satisfaction with life, self-reported happiness and depressive symptoms, although the Canadian study provides a contrary result. Moreover, all four studies suggest that wellbeing declines after the first year of marriage, although the amount of decline varies across studies. None of the four studies found consistent evidence of gender differences. Given the small number of studies that have used fixed effects models, however, additional research is necessary to establish the broader generality of these findings.

Marriage versus non-marital cohabitation

Non-marital cohabitation, like marriage, provides people with companionship, intimacy and everyday assistance. And like married couples, cohabiting couples benefit financially from economies of scale. For these reasons, living together may protect people's mental health in ways comparable to marriage. Of course, cohabitation is less institutionalised than marriage, and cohabiting partners do not have the same long-term time horizon as married couples. Moreover, cohabiting individuals report less relationship happiness and commitment to their partners than do married individuals (Brown, 2000; Brown & Booth, 1996; Nock, 1995). Consistent with these trends, cohabiting relationships (that do not transition to marriage) are less stable than marriages (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008). This is true not only in the United States, but also in other countries, including the Scandinavian countries (Kennedy & Thomson, 2010) and Australia (Wilkins & Warren, 2012).

These considerations suggest that with respect to mental health, cohabiting individuals may be better off than single individuals, on average, but not as well off as married individuals - a conclusion supported by cross-sectional (Brown & Booth, 1996; Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005) as well as longitudinal studies (Soons et al., 2009; Zimmerman & Easterlin, 2006). Comparative studies also show, however, that the magnitude of the marriage advantage depends on a variety of contextual characteristics. In particular, the gap in wellbeing between married and cohabiting individuals is larger in countries where non-marital cohabitation is relatively uncommon and low in social acceptance (Soons & Kalmijn, 2009), traditional gender roles persist and religiosity is high (Lee & Ono, 2012), and the culture emphasises collectivism rather than individualism (Diener et al., 2000). Given that the advantage of marriage over cohabitation may be socially and historically specific, additional research that compares the effects of cohabitation and marriage on mental health in different times and places is warranted.

Wives as well as husbands?

Scholars writing in the 1970s (e.g., Bernard, 1972; Gove & Tudor, 1973) often assumed that marriage is less advantageous for wives than for husbands. In the past, many women quit their paid jobs when they married (or became mothers) and sacrificed their autonomy for their relationships. Moreover, wives who worked at home, compared with husbands, had less power, engaged in less satisfying work, and performed work that was valued less by society. And wives who did continue in the labour force often found that they were forced to do a second shift when they got home (Hochschild & Machung, 1989). According to this view, marriage in the past improved the mental health of husbands but had no effect, or even a detrimental effect, on the mental health of wives.

Of course, the roles of husbands and wives have changed a great deal in the last 40 years. And although marriages in an earlier era may have been less beneficial for wives than husbands, more recent studies have found few gender differences in the estimated effect of marriage on mental health and general psychological wellbeing (Musick & Bumpass, 2012; Ross, 1995; Soons et al., 2009; Williams, 2003; Zimmerman & Easterlin, 2006). Despite the lack of support for gender differences in this area, persistent concerns about gender inequality suggest that it would be premature to abandon the search for gender differences in marriage and other close relationships. Moreover, cohabiting relationships tend to be more equal than marriages, at least with respect to the household division of labor (Baxter, 2001). This observation raises the possibility that cohabitation may be a better arrangement than marriage for some women's mental health.

The current study

My current research draws on the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) to understand how the transition to marriage affects mental health. Add Health is well suited to assessing the effects of marriage because it follows respondents from adolescence through to their early 30s - the period when most people marry for the first time. The dataset also includes two excellent indicators of mental health: depression and suicide ideation. The current study relies on fixed effects models, which control for all stable (time-invariant) personal characteristics of individuals. Although fixed effects models control for all stable individual traits, they do not control for traits that change over time. For this reason, the current analysis includes controls for age (and age squared to account for non-linearity), years of education, hours of employment and whether respondents have biological children.

My research also considers whether the estimated effects of marriage decline over time. Although several studies suggest that the benefits of marriage fade after several years, long-term marriages may still be preferable to singlehood. The current study also considers whether non-marital cohabitation is followed by improvements in mental health. Despite the fact that cohabitating relationships tend to be less happy and stable than marriages, prior research suggests that both types of relationships are good for people's life satisfaction and mental health. Finally, the present study focuses on gender differences in how marriage and cohabitation affect mental health. Although some prior research suggests that both women and men benefit from being in close relationships, the persistence of marital inequality suggests that marriage may still be a more beneficial arrangement for husbands than wives.

Method

Data came from Waves 1, 3 and 4 of the Add Health dataset. Add Health started as a nationally representative survey of 20,745 adolescents in Grades 7 through 12 in the United States in 1994-95. In the first wave, data were collected through in-home interviews with adolescents and one of their parents. Youth were interviewed a second time in 1996, a third time in 2001-02, and a fourth time in 2007-08. (I did not use the second wave because it followed the first wave by only one year.) The final sample included 18,924 respondents for whom at least two waves of data were available; that is, Waves 1 and 3, Waves 1 and 4, or Waves 1, 3 and 4. (Some respondents who missed Wave 3 were tracked and interviewed in Wave 4.)

Table 1 includes descriptive information about the sample by survey wave (weighted). The mean age (in years) increased from a little over 16 in Wave 1, to 29 in Wave 4. (The oldest respondents were 34 at the final wave.) At the time of the first interview, the average adolescent had completed between 9 and 10 years of education. The corresponding figure for Wave 4 was about 14 years. Mean weekly hours of employment increased from about eight during adolescence to over 41 in Wave 4. Only 2% of adolescents had become biological parents by the time of the first interview, although this figure increased to over half of the sample in Wave 4.

| Wave 1 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Add Health | |||

| Age | 16.19 | 22.48 | 29.01 |

| Years education | 9.70 | 13.22 | 14.28 |

| Hours employed | 7.75 | 28.26 | 41.59 |

| Have children | .02 | .26 | .51 |

| Marriage | .00 | .18 | .43 |

| Cohabitation | .00 | .15 | .18 |

| Depression | -.05 | -.06 | .08 |

| Suicide ideation | .13 | .07 | .07 |

Table 1 also shows information on relationship status at the time of the survey. By Wave 3, 18% were married, and 43% by Wave 4. Correspondingly, 15% of youths were cohabiting (but unmarried) by Wave 3 and 18% by Wave 4. Note that these figures underestimate the percentage of respondents who ever married or cohabited, because relationship status is coded at the time of the survey. Respondents who married or cohabited and broke up between surveys are not included in these figures. This qualification is especially relevant to cohabitations, which generally last only a year or two in the United States before breaking up or transitioning into marriage. Although not shown in the table, the mean duration of marriage for married respondents was 2.2 years in Wave 3 and 4.7 years in Wave 4. Correspondingly, the mean duration of cohabitation was 1.9 years in Wave 3 and 3.1 years in Wave 4. (A handful of adolescents were married or cohabiting in Wave 1; these cases were dropped from the analysis because no information on mental health was available prior to relationship formation.)

A measure of depression was based on nine items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. These items were worded identically in all survey waves, and the mean alpha reliability across all waves was .81. Items were added and the total score was standardised across waves to improve interpretability (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1). Table 1 shows that the mean level of depression was relatively stable across all three waves. The second measure of mental health was a question about suicide: "During the last six months, did you ever think seriously about committing suicide?" The proportion of people responding positively to this question declined slightly between adolescence and early adulthood.

Results

Table 2 shows the results from regressing depression scores on marriage and cohabitation. Although not shown, age, age squared, years of education, weekly work hours and having biological children were included as control variables in the models. Separate models were estimated for men and women. For both genders, the transition to marriage was associated with a decline in symptoms of depression. Moreover, the magnitude of the decline was the same for men (-.15) and women (-.15).

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Notes: Models include controls for age, age squared, years of education, weekly work hours and having children. Significance tests are based on robust, clustered standard errors. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 (two-tailed). Source: Add Health | ||

| Marriage | -.15 *** | -.15 ** |

| Duration | .00 | .02 ** |

| Cohabitation | -.14 *** | -.16 ** |

| Duration | .01 | .02 * |

| N cases | 8,086 | 8,731 |

| N observations | 21,476 | 23,706 |

These results are consistent with the assumption that marriage is good for people's mental health. The table also shows, however, that transitions to non-marital cohabitation were followed by similar declines in symptoms of depression for men (-.16) and women (-.14). Moreover, the estimated effects of marriage and cohabitation were not significantly different from one another. So it appears that living with a partner, rather than marriage per se, was responsible for improvements in depression. Relationship duration (marriage or cohabitation) was not related to depressive symptoms among men. Among women, however, depression was positively related to the duration of both marriage (.02) and cohabitation (.02).

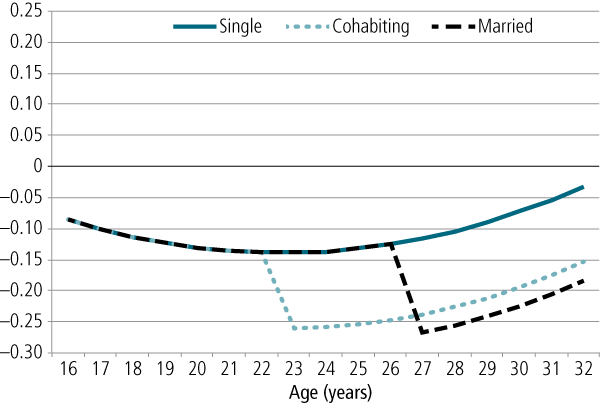

Figure 1 shows the trajectory of depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood (derived from the regression model) for men. The solid line shows the mean depression scores for single men. The line is slightly curvilinear, with a modest rise after the mid-20s. The dotted line shows the mean depression scores for men who shifted into cohabiting relationships at age 23 - the mean age at first cohabitation for men in the sample - and then remained in these relationships without breaking up or marrying. This transition was accompanied by a decline in symptoms. Correspondingly, the broken line shows the mean depression scores for men who shifted into marriage at age 27 - the mean age at first marriage for men in the sample. Marriage, like cohabitation, was accompanied by a decline in symptoms. For cohabiting men as well as married men, levels of depression rose during the late 20s and early 30s, but the gap in depression between single men and partnered men (cohabiting or married) remained constant over time.

Figure 1: Depression z scores by age and relationship status for men

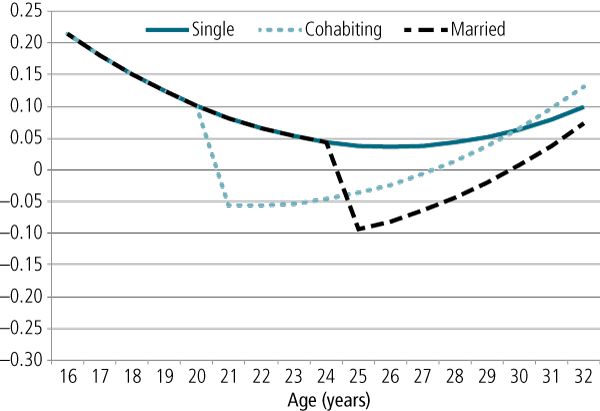

Figure 2 shows the overall trajectory of depressive symptoms for women. Comparing Figure 2 with Figure 1 reveals that depression scores, overall, were higher for women than men. The solid line in Figure 2 shows the mean depression scores for single women. The line is curvilinear, with a decline from adolescence to the mid-20s, followed by a slight increase after that. The dotted line shows the mean depression scores for women who shifted into cohabiting relationships at age 21 - the mean age at first cohabitation for women in the sample. This transition was accompanied by a decline in symptoms. Correspondingly, the broken line shows the mean depression scores for women who shifted into marriage at age 25 - the mean age at first marriage for women in the sample. Marriage, like cohabitation, was accompanied by a decline in symptoms. For cohabiting as well as married women, levels of depression rose during the late 20s and early 30s. Contrary to the pattern for men, the gap in depression between single women and partnered women (cohabiting or married) closed during this time. In other words, the benefit of having a residential partner dissipated after several years.

Figure 2: Depression z scores by age and relationship status for women

Table 3 shows the results of regressing suicide ideation on marriage and cohabitation. For both genders, the transition to marriage was associated with a decline in suicide ideation. Moreover, the magnitude of the decline was similar for men (-.64) and women (-.69). Similar to the results for depression, these results are consistent with the assumption that marriage is good for people's mental health. The table also shows that transitions to cohabitation were followed by similar declines in suicide ideation for men (-.46) and women (-.56). Although the coefficients for cohabitation were somewhat smaller than the corresponding coefficients for marriage, the differences between them were not statistically significant. Once again, it appears that living with a partner, rather than marriage per se, was responsible for improvements in mental health. Relationship duration (marriage or cohabitation) was not related to suicide ideation among men. Among women, however, marriage duration was positively related to suicide ideation (.07). The corresponding duration trend was positive but not statistically significant for cohabitation. (Note that the number of cases is lower in Table 3 than in Table 2. This is because fixed effects models omit cases that do not change on the dependent variable between waves. So these results are based only on cases that reported thoughts of suicide in one wave and not in another.)

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Notes: Models include controls for age, age squared, years of education, weekly work hours and children. Significance tests are based on robust standard errors. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 (two-tailed). Source: Add Health | ||

| Marriage | -.69 *** | -.64 *** |

| Duration | .04 | .07 ** |

| Cohabitation | -.56 ** | -.46 ** |

| Duration | .04 | .02 |

| N cases | 1,255 | 1,868 |

| N observations | 3,420 | 5,190 |

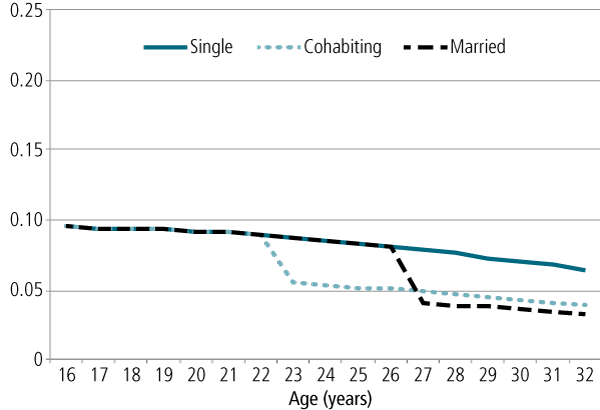

Figure 3 shows the probability of suicide ideation from adolescence to adulthood (derived from the regression model) for men. The solid line for single men reveals a modest decline in the probability during this period. The figure also shows that transitions into cohabitation and marriage were associated with declines in thoughts of suicide. Moreover, the gaps between single men and partnered men did not change over time.

Figure 3: Probability of suicide ideation by age and relationship status for men

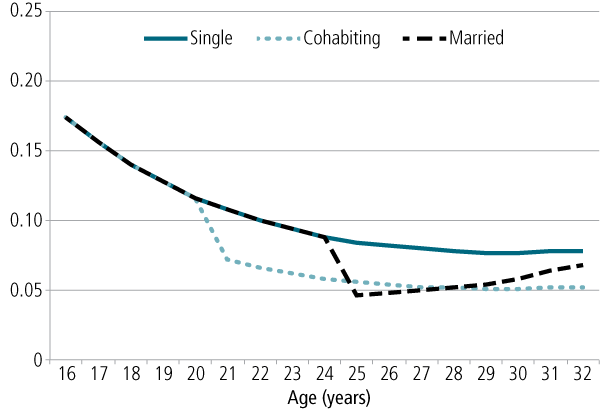

Figure 4 shows the probability of suicide ideation for women. The solid line shows the probability of suicide ideation scores for single women. The trend line for single women reveals a prominent decline between adolescence and the mid-20s. Comparing Figures 3 and 4 reveals that women were more likely to report thoughts of suicide during adolescence than were men, although the probabilities for the two genders were roughly similar in adulthood. Figure 4 also shows that cohabitation and marriage were followed by declines in the suicide ideation. The probability increased again after the first year of marriage, however, and the gap between single and married women had largely closed within a few years. Consistent with the results for depression, the benefit of marriage for women's mental health proved to be temporary.

Figure 4: Probability of suicide ideation by age and relationship status for women

Discussion

Many studies have found that married people are happier and healthier than single people. But does this mean that marriage is good for people, or does this reflect something about the type of people who get and stay married? Several studies have attempted to answer this question by using fixed effects statistical models. This approach is useful because it controls for all stable characteristics of people. And because this method compares individuals with themselves at different points in time, it is possible to see if marriage is followed by significant improvements in people's health. Only a handful of studies have used this approach to study marriage, and the results of these studies have not been consistent. Moreover, it is not clear from previous work if non-marital cohabitation has the same benefits as marriage, if the benefits of marriage (and cohabitation) are temporary or long-term, or if the benefits of marriage (and cohabitation) apply equally to men and women.

My research shows that marriage is indeed followed by significant improvements in people's mental health. Following marriage, people report fewer symptoms of depression and are less likely to think about suicide. Moreover, the benefits of marriage (at least in the first year) are comparable for husbands and wives. These findings are consistent with two other studies that also used fixed effects models (Soons & Kalmijn, 2009; Zimmerman & Easterlin, 2006). So the general notion that marriage is good for you appears to contain some truth. My analysis also suggests, however, that non-marital cohabitation has the same protective effects on men and women's mental health as does marriage. Moreover, although some previous research has suggested that marriage is more beneficial than cohabitation, my research indicates that the two statuses are equally beneficial. According to the current study, it does not matter whether people are legally married; shifting into any type of intimate, co-residential relationship is followed by improvements in mental health.

This finding casts light on why marriage might be good for people. Some scholars have argued that marriage is beneficial because of its institutional nature. In most Western countries, marriage (a) is defined by laws and social norms that clarify spouses' rights and obligations to one another, (b) is a highly valued status, and (c) provides a variety of legal and social benefits to spouses. But even though cohabitation is not institutionalised to the same degree as marriage, cohabitation involves similar improvements in people's mental health. These findings suggest that it is the social support provided by marriage, rather than the institutional nature of marriage, that is beneficial for emotional wellbeing. After all, one doesn't need to be legally married to a residential partner to enjoy companionship, intimacy and everyday assistance. Moreover, living together and marriage provide the same economies of scale, which can reduce people's feelings of economic stress.

Before we assume that marriage and cohabitation are interchangeable, however, we should consider the fact that cohabitations are less stable than marriages. In the United States, for example, most cohabitating unions either transition to marriage or break up within two years (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008). Cohabitating relationships tend to be less stable than marriages in most other Western countries as well, including the Scandinavian countries (Kennedy & Thomson, 2010) and Australia (Wilkins & Warren, 2012). For most people, marriage is the arrangement of choice for long-term relationships.

These considerations lead to the question of whether the benefits of marriage and cohabitation persist indefinitely or decline with time. The current analysis indicates that the benefits of intimate residential relationships persisted indefinitely for men. Because the Add Health sample consists of young adults, the mean duration of marriage in Wave 4 was less than five years, and few marriages were longer than 10 years. It is not possible, therefore, to say whether the benefits of marriage and cohabitation persisted longer than a decade for men in the current study. For women, however, the benefits of intimate residential unions began to decline after the first year. This was true for marriage (with respect to depressive symptoms and suicide ideation) and cohabitation (with respect to depressive symptoms). So the answer to the question about long-term benefits appears to depend on gender.

Why might the benefits of marriage for women be short-lived? Early family scholars argued that marriage is an unequal arrangement that benefits husbands more than wives (e.g., Bernard, 1972). So the temporary advantage of marriage for wives may be a reflection of gender inequality. Of course, marriages are more equal today than they were a generation ago (Amato, Booth, Johnson, & Rogers, 2007). Moreover, the benefits of cohabitation also fade for women over time, despite the fact that cohabiting relationships tend to be more egalitarian than marriages (Baxter, 2001). Another explanation involves the notion that women are more attuned to relationship quality than are men. That is, women tend to monitor and think about relationships more than men do, and they tend to become aware of relationship problems more quickly (Thompson & Walker, 1990). In fact, research consistently shows that women are less satisfied than men with their marriages and romantic relationships (Amato et al., 2007). Consequently, it is probable that the decline in mental health following the transition to marriage (or cohabitation) reflects women's growing awareness of and sensitivity to relationship problems.

Keep in mind that the changes in mental health following marriage and cohabitation shown in Figures 2 and 4 reflect statistical averages and do not apply to all women. Presumably, mental health following marriage or cohabitation remains high for women who continue to be happy with their relationships. Nevertheless, this trend is of concern, especially in households with children, because a general deterioration in mental health has implications for the quality of parenting and children's wellbeing. Research consistently shows that depression among mothers (and fathers) is associated with problematic parenting behaviours - coercion, lack of affection, disengagement - and an enhanced risk of psychosocial problems among children (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, 2000).

States and communities may be able to ameliorate some of these problems by providing resources to strengthen spousal and partner relationships. In the United States, marriage and relationship education has been shown to enhance relationship quality and stability (Hawkins, Blanchard, Baldwin, & Fawcett, 2008), although the benefits of these programs for low-income populations are less clear (Amato, 2014). Similarly, community mental health services for distressed parents and their children have become a feature of modern life in many countries, although disadvantaged populations continue to be under-served (World Health Organization, 2007). Close relationships may be good for people's mental health, but these relationships do not exist in a vacuum, and supportive policies and services are needed to ensure that strong and health-promoting relationships will form and be sustained for many years.

References

- Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Amato, P. R. (2014). Does social and economic disadvantage moderate the effects of relationship education on unwed couples? An analysis of data from the 15-month Building Strong Families evaluation. Family Relations, 63(3), 343-355.

- Amato, P. R., Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., & Rogers, S. J. (2007). Alone together: How marriage in America is changing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Baxter, J. (2001). Marital status and the division of household labour. Family Matters, 58, 16-21.

- Bernard, J. (1972). The future of marriage. New York: Bantam Books.

- Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States (Vital and Health Statistics, Series23, No. 22). Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics.

- Brown, S. L. (2000). The effect of union type on psychological wellbeing: Depression among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(3), 241-255.

- Brown, S. L., & Booth A. (1996). Cohabitation versus marriage: A comparison of relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(3), 668-678.

- Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(4),848-861.

- Diener, E., Gohm, C. L., Suh, E. M., & Oishi, S. (2000). Similarity of relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 31(4), 419-436.

- Gove, W. R., & Tudor, J. F. (1973). Adult sex roles and mental illness. American Journal of Sociology, 78,812-835.

- Hawkins, A. J., Blanchard, V. L., Baldwin, S. A., & Fawcett, E. B. (2008). Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 76, 723-734.

- Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking Press.

- Kamp Dush, C., & Amato, P. R. (2005). Relationship happiness, psychological well-being, and the continuum of commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 607-628.

- Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. (2008). Cohabitation and children's living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663-1692.

- Kennedy, S., & Thomson, E. (2010). Children's experiences of family disruption in Sweden: Differential by parent education over three decades. Demographic Research, 23,479-507.

- Lee, K. S., & Ono, H. (2012). Marriage, cohabitation, and happiness: A cross-national analysis of 27 countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 953-972.

- Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. A., O'Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5), 561-592.

- Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Reexamining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: Reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 527-539.

- Musick, K., & Bumpass, L. (2012). Reexamining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 1-18.

- Nock, S. L. (1995). A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 16(1),53-76.

- Rogers, R. G. (1995). Marriage, sex, and mortality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(2), 515-526.

- Ross, C. E. (1995). Reconceptualizing marital status as a continuum of attachment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(1), 129-140.

- Soons, J. P. M., & Kalmijn, M. (2009). Is marriage more than cohabitation? Well-being differences in 30 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(5), 1141-1157.

- Soons, J. P. M., Liefbroer, A. C., & Kalmijn, M. (2009). The long-term consequences of relationship formation for subjective well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(5), 1254-1270.

- Thompson, L., & Walker, A. J. (1990). Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 51(4), 845-871.

- Waite, L., & Gallagher, M. (2000). The case for marriage. New York: Doubleday.

- Wilkins, R., & Warren, D. (2012). Families, incomes, and jobs: Vol. 7. A statistical report on Waves 1 to 9 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

- World Health Organization. (2007). Community mental health services will lessen social exclusion [media release]. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved from <www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2007/np25/en/>.

- Williams, K. (2003). Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage, and psychological well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(4), 470-487.

- Wu, Z., & Hart, R. (2002). The effects of marital and non-marital union transition on health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 420-432.

- Zimmerman, A. C., & Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Happily ever after? Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and happiness in Germany. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 511-528.

Professor Paul R. Amato is Arnold and Bette Hoffman Professor of Family Sociology and Demography at the Pennsylvania State University, USA. This article is based on the keynote address given by Paul Amato at the 13th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference: Families in a Rapidly Changing World, Melbourne, 1 August 2014.

Acknowledgements: This publication uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other US federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgement is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. No direct support was received from grant P01HD31921 for the current analysis. The Penn State Population Research Institute supported the research described in this publication under award number R24HD041025 from the National Institutes of Health.

Amato, P. R. (2015). Marriage, cohabitation and mental health. Family Matters, 96, 5-13.