Conference Keynote. What can early interventions really achieve, and how will we know?

April 2017

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

In this article, based on his keynote address given at the 16th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference, Professor John Lynch considers evidence-based policy-making from the perspective of an epidemiologist. Professor Lynch describes recent evaluations of several early childhood programs from Australia and overseas, and concludes with recommendations for getting "good-enough" evidence. Considering that less than 50% of the research on early childhood programs can be regarded as of moderate or high quality, better evidence must be produced to justify public expenditure on interventions.

The call for "evidence-based" policymaking has become common. This has been attributed to the confluence of a better-educated public, a rapid rise in research capacity, and vastly expanded information technology. Overall, there is a drive for more accountability in public spending that moves with the political times and the ability to demonstrate better outcomes with less waste.

From the perspective of an epidemiologist, my discussion in this paper will be about better understanding the evidence base for several prominent early childhood programs overseas and in Australia, and determining some key messages about the quality of evidence informing early childhood intervention programs. And what it may mean for evidence-based policymaking in 21st-century Australia.

I speak of 21st-century Australia deliberately, because what worked in other places decades ago may not be appropriate for the current concerns and conditions in Australia. Obviously, we will need to learn lessons from the best available information, but where answers are not available or not appropriate, we will also need to innovate within our own cultural context and existing network of support services. This ought to be liberating for those of us wishing to improve the lives of disadvantaged children and families. Recognition that magic bullets are in short supply ought to drive pragmatic and useful research-policy-practice partnerships to build a base of effective evidence relevant to 21st-century Australia. It will require innovation and commitment at the local, state and federal levels within government and non-government sectors. It will need co-design partnerships with academic researchers and coordinated efforts within and across public and private research funding agencies.

What is evidence?

It is widely accepted that not all research evidence is created equal. Or in plain language, don't accept everything that academics claim. There are many evidence reviews in the field of child health and development, and they are of variable quality and accuracy. Accuracy of overall assessments about evidence is fundamentally dependent on the quality of review of individual studies.

Reviewing scientific evidence is not a trivial or necessarily straightforward activity that any newly minted PhD can take on. In the end, it requires returning to the original studies and forensically examining how individual studies were conducted and reported. This can be assisted by using checklists and risk of bias tools but it fundamentally requires experienced, critical, scientific insight. It has been increasingly recognised over the last 20 years that, unfortunately, the design, implementation and interpretation of some scientific studies is not optimal. This is not limited to studies relevant to child health and development, and applies to many branches of science including health and medical care. Those who use evidence to inform policy and practice innovation need to begin by understanding that just because a study is published in a scientific journal, by people holding PhDs, does not mean the study has been well done and that the findings are valid.

The definition of "evidence" is interesting. The Oxford English dictionary defines it as "the available body of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or valid." That seems a strict definition that probably aligns well with the idea of research evidence. But in addition to that, there's also a more flexible notion that evidence is signs or indications of something. It's interesting to contemplate how evidence is used in different fields, whether it's "research evidence" in our field or the way evidence is used in legal settings.

It would be naive not to recognise that policy- makers and service delivery practitioners must not only take account of research evidence but also signs and indications from prevailing culture, values, social opinions, influential individuals and organisations, politics and the distribution of power. It is within that framework that I discuss research evidence. Research evidence is only one component of what can actually drive public policy and practice.

Nevertheless, we are living in an increasingly evidence-based society requiring publicly funded programs to justify what they do on the basis of evidence. There are countless types of documents used to inform evidence for programs, including individual studies, reviews, frameworks and evaluations. As a result, we've developed a "research evidence industry" involving lots of activities designed to generate the evidence we seek. All these activities, in various ways, distil down to an attempt to summarise what we know about what works.

Epidemiology is a field of science that is about describing health states in populations; what causes those health states, and how to intervene to improve them. Epidemiology is explicitly about causation and has played an important role in the enormously successful rise in evidence-based medicine over the last 25 years. Given significant public expenditure on health, it is important to treat people safely, effectively and cost-efficiently. Accordingly, health and medical research has developed increasingly well-defined ways to reliably conduct and report the science behind providing health and medical care. In health and medical research, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are a central pillar. There are over 1000 RCTs reported each year in health and medical care. It is well known that RCTs are not appropriate or applicable for every situation where we need evidence, but in many circumstances they will generate the best evidence because they can give more reliable understanding of the causal effects of programs on outcomes.

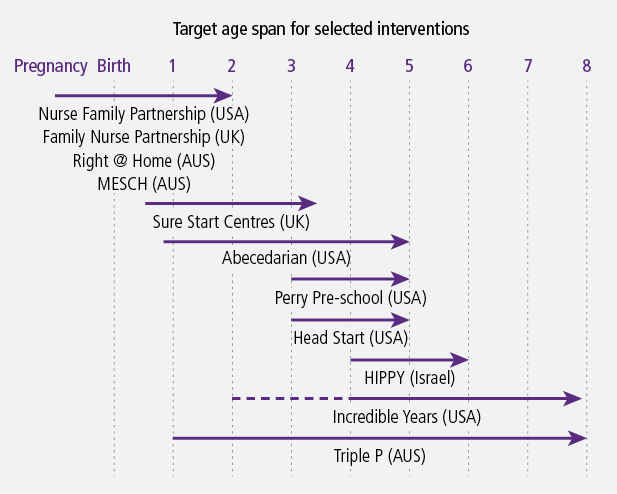

Let's begin by looking at some of the most well-known randomised and quasi-experimental studies contributing to the evidence base supporting child health and development programs in early life (Figure 1). Quasi-experimental studies are when an intervention is given to a group but that group is not randomly assigned to receive the intervention. Because intervention and comparison groups are not randomly assigned it makes it more difficult to create a comparison. This is of course also true of RCTs where baseline imbalances between intervention and comparison groups are almost always present, but these differences result from random rather than potentially systemic differences, as is common in quasi-experimental studies.

Figure 1: Selected interventions with randomised and quasi-experimental evidence

Selected interventions

Nurse Family Partnership (USA)

Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) is a US program that has been run in several other countries, including the UK (where it's called Family Nurse Partnership) and Australia. It is a parenting support program primarily for low-income, first-time mothers who are supported by intensive nurse home visits.

The first randomised control study of the NFP started in 1978 at Elmira in New York (n = 100/116/184), with subsequent studies in 1990 in Memphis (n = 228/515) and 1994 in Denver (n = 235/245/255). These studies showed the effectiveness of having a nurse support mothers in pregnancy until the child was 2 years old. The program typically provides up to 33 home visits for mothers (lasting 75-90 minutes) pre- and post-birth until the child is 2 years old. As an indication of its cost, the 1994 program in Denver cost an average of US$11,000 per child.

This series of studies resulted in different effects in the different locations and at different ages of the child, so I will focus only on consistent effects across the sites in the whole sample up to age 15. The consistent effects across the trials were increased maternal antenatal health care and children's school readiness, greater birth intervals and maternal employment, and decreased subsequent pregnancies, welfare dependency and children's injuries (used as a proxy for child maltreatment). These improvements are impressive but it should also be remembered that there were a greater number of outcomes that NFP did not improve. This is not a criticism of NFP, rather it is making the point that there is little evidence that such programs are magic solutions to fix all the problems we are concerned about. We need clear program logic linking the "active ingredients" of any interventions to the outcomes we expect them to improve. For instance, despite being some of the highest quality studies, NFP only positively affected about 15% of the primary and secondary outcomes studied across the three RCTs.

At the Elmira site, the program initially focused on high-risk groups - for example, women who were smoking in pregnancy. But over time, the NFP increasingly focused on poor, unmarried teens (which was about 23% of the Elmira population), where the positive effects were larger. This analysis later focused on sub-groups of those with "low psycho-social resources", low IQ, mental health problems and low self-efficacy. Many of the strongest NFP effects have been reported among these participants.

However, the trials were not large enough to examine these subgroup effects rigorously - they were never "powered" in a research sense. Again, that is not a criticism of NFP but it should be considered when we design new RCTs of these sorts of programs. This also needs to be considered when assessing the evidence for NFP. The focus on participants with low psycho-social resources has continued in other nurse home-visiting studies, such as MESCH mentioned below.

Lesson no. 1: Power trials properly

This leads to my first message - RCTs are really expensive to run well, so researchers and research funders in the 21st century had better power them properly. That means having large enough sample sizes so that we can reliably estimate the effects we think our program will achieve, and to measure those effects for the sub-groups we believe may benefit most.

There is an emerging literature in general science about how underpowered many scientific studies are, and have been for decades. For instance, a recent review of the neuroscience literature showed only about 30% of studies were adequately powered. In our current desire for better evidence, conducting underpowered studies is both a waste of research resources and is unethical.

Lesson no. 2: Understand the context of the trial

In regard to understanding the relatively modest longer-term NFP effects, it is important to look at the broader social context of the program. In the case of the Elmira site in 1980, it was rated the worst metro area in the US for economic conditions. From 1980 to 2010, its population fell 21%, with unemployment running at around 12%. Elmira's current median income is about 30% below the national average.

What does this mean? That local context can severely constrain early intervention effects on long-term outcomes. Why would we think that a program operating from pregnancy through to age 2 is going to have a long-term effect when those kids go on to poor child care, poor preschools, underfunded schools and then into an employment environment that's severely constrained?

So my second message is - we need to understand the context and the ongoing resources and interventions that are required to keep those early effects going.

MESCH (Australia)

Like NFP, The Miller Early Childhood Sustained Home Visiting program (MESCH) involves intensive home visits by a nurse up to the first two years of a child's life. Conducted from 2003-05 (n = 111/97), the study included participants that had a combination of risk factors including being under 19 years old, scoring high on the Edinburgh depression scale, and a lack of social support. About 80% of the participants had one or two of these risk factors. The program resulted in about 16 nurse visits (about half of the NFP) to the home. This lower number of visits was due to about half of the participants dropping out by the time the child was 1 year old.

The study examined about 20 outcomes in children at age 2. The only main effects were related to parenting responsiveness of the mother, and a very large effect on breastfeeding duration (on average, eight weeks longer).

Lesson no. 3: Don't over-rely on sub-group analysis

By doing several sub-group analyses the study also presented evidence that effects were greater among those with low psycho-social resources. However, the trial was never powered to do rigorous sub-group analysis and, consequently, the researchers highlighted only selected positive effects to present in the results. A full assessment of the evidence showed the overall sub-group patterns were quite mixed.

It's important to note that positive effects in studies like these can be modest in scope and size despite what is sometimes claimed from sub-group analyses. This leads to my next message - do not rely heavily on sub-group analysis. Although it doesn't mean that the finding is wrong, it means that they will be unreliably estimated, and potentially not reproducible. If we have compelling a priori sub-group questions, then power the study to answer them.

The Abecedarian Project (USA)

Conducted in 1972-77 and based in North Carolina, the Abecedarian project administered virtually full-time, high-quality educational interventions in a child care setting in a small sample of children from about 9 months of age through to 5 years old, with a subset going to age 8 (n = 57/54). Children were randomly assigned to either the intervention or to a control group. The program was intensive - eight hours a day, five days a week, for 50 weeks, and included home visits, curriculum packets, medical and nutrition advice). It cost about US$70,000 per child.

The study had a small sample size of about 60 in the intervention group and was targeting very low income African-Americans. One example of what they did find was that up until children were 21 years, there were increases in IQ, academic achievement and test scores. Another unique finding was that by the time the participants were 40 years old, a big effect was found in the reduction of blood pressure of 17mL of mercury. The importance of this finding is the project seemingly generated an effect almost twice as large as the effect of the best currently available medical treatments. That effect is hard to understand. But again, it's coming from a very small study and when you have small samples you may generate random large effects.

It is interesting to note current guidelines for staffing ratios in the Australian education and care system are not that different from the Abecedarian intervention. So, in 21st-century Australia we already have aspects of usual care that are approaching in some ways the interventions that were trialled in the US 40 years ago. It is another reminder that it's important to be aware of the context and "control conditions" within which effects were tested.

High Scope/Perry Pre-School (USA)

The High Scope/Perry Pre-school program was implemented in Ypsilanti, Michigan, from 1962 to 1967. The program randomly assigned a small number (n = 58/65) of children aged 3-4 who were born into poverty with low IQs into the intervention or control groups. The program group received a high-quality preschool program based on Paigetian principles of participatory learning. The participants received the program two and a half hours per day, five days a week, 30 weeks a year, with an additional one and a half hour home visit up to age 5. Again, there was a low child-teacher ratio with highly trained practitioners. It cost about US$18,000 per child.

The study found that up to 40 years of age, participants had better test scores, less criminal activity, more earnings, less welfare payments, and less smoking and alcohol. It found large effects on participant IQ but these results faded by age 7. That result - good life outcomes but fading IQ results by 7 years - is something many researchers have tried to interpret. One interpretation is that participants' life success could be a result of what have been called "non-cognitive skills". These refer to self-regulatory abilities, resilience, grit, attention, perseverance etc. These kinds of characteristics are seen as skills, in contrast to cognitive ability, and it is commonsense that they are also related to greater success in later life.

Duncan and Magnussen systematically reviewed the evidence for US programs (including Abecedarian and Perry Pre-school) and noted a general decline in program effects over 40 years. It is clear from their review that both Abecedarian and Perry Pre-school programs were exceptional in the size of the effects they generated on cognitive and academic achievement outcomes, compared to other programs operating in the 1960s and 1970s in the USA. One plausible explanation for the decline in program effects is that the control conditions changed over time. As society becomes more oriented to greater social justice, and we start to have better services to support disadvantaged people, the safety nets start to get better and the control conditions change, making it more difficult to observe large effects of intensive programs to support disadvantaged families and children.

Family Nurse Partnership (FNP; UK)

The RCT of the FNP in the United Kingdom was large, including 823 women receiving the intervention and 822 in usual care. In a very high quality study published in 2016, the researchers found no effects of FNP over usual care. They concluded that, "program continuation is not justified on the basis of this evidence, but could be reconsidered should supportive long-term evidence emerge." Despite this, the FNP is apparently still being rolled out in the UK.

Most importantly, this recent UK research highlights that control or comparison conditions matter. In this case, the 21st-century UK usual care for individuals includes a large network of existing health and support services. It may be very hard to find effects of specific interventions against that background.

In reviewing several of these programs, other key messages become clear. First is that the reporting of some intervention studies in this field can be below the accepted standards for the best health and medical research. Second is the issue of overstated evidence, whereby programs administered to small samples are somewhat selectively reported and used as examples of potential large-scale population effects.

Triple P (Australia)

Triple P is a well known and widely disseminated graded program of family and parent support. At its lowest "dose" level (Level 1), it is a population-wide media communications strategy (intended to reach 100% of the population). At its higher levels, it provides more intensive services. For example, Level 4 is more intensive services intended to reach about 10% of the population, while Level 5 is family therapeutic interventions that are intended for about 2% of the population.

A review published in 2012 concluded that there was little evidence to support effects of Triple P across the whole population, nor that effects were maintained over time. In 2014, a review published by the originators of Triple P examined 101 studies, which somewhat curiously combined findings from both experimental and observational designs. Of these 101 studies, 76 were experimental or quasi-experimental with an average intervention level of 3.8 in the five-level Triple P system. Of these studies, 75% had sample sizes smaller than 120, or in other words 60 participants in the intervention group at baseline.

While the number of RCTs investigating Triple P is large, the vast majority are small-sample studies (like Abecedarian and Perry Pre-School). Accordingly, there are concerns about the studies' power and convenience samples. It has been reliably verified in health and medical research that small, under-powered RCTs generally over-estimate effect sizes, which are not confirmed when large RCTs are subsequently performed.

There are only four large population-based studies of Triple P. Two of those are quasi-experimental designs of communities (n = 2 and n = 20) in Australia whose results are difficult to interpret because the observed baseline differences between these communities made it hard to derive valid comparisons.

The third population-based study, originally published in 2009, was a cluster RCT of 18 counties in South Carolina in the USA. This study was subsequently subject to some methodological criticism, which has been recently addressed in a 2016 re-analysis. The original results stand in the re-analysis and show that comparison communities had higher levels of child maltreatment reports, whereas the Triple P communities did not have an increase after the two-year intervention. While this evidence seems solid, it is regrettable it took seven years to obtain a methodologically reliable analysis of the RCT.

The fourth large study (n = 1675 participants in a 56 school cluster RCT) of Triple P that was implemented in Zurich demonstrated little positive effect. In fact, the participants showed lower competence in conflict resolution than the control groups.

Thus, the overall evidence on Triple P is mixed, especially among larger RCTs. It also remains difficult to understand how the more intensive versions of the Triple P system (with a limited population reach of 10% or less), could generate protective effects in the whole population. A recent report from a small cluster RCT of Triple P in Sweden reported poor uptake of the Level 2 and 3 sessions of Triple P, where, of those who agreed to participate in the RCT, 71% failed to attend any Triple P sessions. This study showed no effects of Triple P.

The need for better research evidence

Further support for some of the views expressed above can be found in recent high-quality evidence reviews that have reached qualitatively similar conclusions that the overall evidence under-pinning practice in early child health and development would benefit from revitalisation. I will mention one such review here: the US Department of Health and Human Services' Home Visiting Programs Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) review (2016).1

Home Visiting Programs Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE; USA)

As part of ObamaCare, the US Department of Health and Human Services invested significant funding in home-visiting programs. HomVEE provides an assessment of the evidence of effectiveness for home-visiting programs that target families with pregnant women and children from birth to kindergarten entry. Basically HomVEE is trying to drive public funding into effective interventions, essentially saying: "Here's one way of doing something, here's another way, let's figure out what the best one is and we'll pay for that one."

The HomVEE results are informative. The review found 19 "supported" programs and 25 "not supported" programs (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation [OPRE], 2016). First, that means only 43% of available programs are supported by moderate to high quality evidence. Furthermore, of the 231 eligible studies, only 42% of those research studies were moderate to high quality. The supported programs included: NFP (supported by 21 studies), Healthy Families America (19 studies), Durham Connects, HIPPY and MESCH. Triple P home visiting was not supported.

This begs the question - why is it that less than 50% of the research evidence involving home visiting programs is moderate to high quality? That is a clear challenge for researchers and research funding through public sources. We need to do better than that.

In my own research team, we've just completed a systematic review of studies of non-cognitive skills in children under 8 years. The term non-cognitive skills was introduced 40 years ago by US economists Bowles and Gintis to cover all those attributes beyond IQ and academic achievement that build success in life, such as perseverance, attention and social skills. We found 375 studies were eligible for review. We rated the evidence rigorously but fairly, and concluded that only 38% of those 375 studies could be considered better quality evidence.

So, about two-thirds of all the eligible publications ever written on this topic have little to say in terms of contributing to the research evidence on the quantitative effects of non-cognitive skills in children. That seems an enormous waste of effort. Researchers simply have to do better.

The Harvard Centre on the Developing Child (2016) suggests:

The widespread preference for evidence-based programs, many of which have produced small effects on random categories of outcomes, that have not been replicated, seriously limits the ability of achieving increasingly large impacts at scale over time. (p. 8)

Summary

So in considering the evidence and its applicability to inform policy, practice and service delivery in 21st-century Australia, my key messages around outcome or impact assessments are:

- Encourage RCTs for our most promising new programs but we design and power them appropriately. That's especially true if theory suggests effects in particular groups. It would be even better if these RCTs were pragmatic in that they could be conducted within existing service systems and in real-world conditions.

- In assessing evidence, always consider the local context of programs - positive effects found in studies conducted decades ago and in other countries where control conditions or usual care are vastly different to those in 21st-century Australia ought to be carefully scrutinised.

- Be aware of large beneficial effects found from sub-group analysis.

- Exceptions are not rules. Even some of the most promising programs such as Abecedarian may be exceptional given all the other programs that were being researched at the same time. The reasons for apparent exceptions need to be understood.

- Question overstated evidence claims. Most of the research in this field generates modest effects at best - generally with effect sizes of the order 0.2-0.3 SD units. Promises of transformative programs that will solve wicked, complicated problems ought to be viewed sceptically because there are precious few research examples of that happening.

We can do much better in the way we conduct and report outcome effectiveness research in this field. Less than 50% of the research on outcome effects of early childhood programs we currently have available can be regarded as of moderate to high quality. That's a big gap and it is disappointing that so much research effort is unable to shed much light on the questions of importance to policy and practice. Of course it depends heavily on adequate research funding, but this is nevertheless a challenge to researchers, research funders, reviewers and journal editors. In the health and medical care sector, researchers are responding to this challenge by applying consistent principles from evidence-based medicine. Perhaps such experience could be helpful in building a better evidence base for interventions in this field.

Of course it is necessary to have research and formative evaluations that show feasibility, acceptability and uptake of interventions. However, while that is a necessary component of any future outcome evaluation, it may not be sufficient evidence to justify public expenditure on early childhood interventions. We will need both formative and implementation evaluations, including assessments of the impacts on intended outcomes.

There is no doubt we need to develop new programs in this area and that will take a lot of hard work. And we've got to test programs in well-designed, adequately powered pragmatic RCTS. It is hard to imagine how we'd deliver resource-intensive programs, such as the ones mentioned above, in standard service delivery without good evidence.

Unquestionably, we need to have a conversation about what intervention "dose" is required to achieve improvement and how that can be delivered at a large scale.

Additionally, there needs to be integration with existing services and information systems across the health, child care, preschool, education and child protection sectors. There needs to be a discussion about the use of existing administrative data. We collect lots of administrative data, but we're not using it optimally for service improvement when we could.

More importantly, we need to develop well-planned, well-resourced and well-integrated iterative enhancements to existing services. Innovation is going on every day. Practitioners are changing the way they work and we need to leverage the innovation happening within service delivery. These are enhancements to usual care that potentially can be evaluated in a routine, rapid and cost-effective way. We need practitioners to think about practice-based evidence and how to partner with academia from the start to evaluate their innovations.

Getting "good-enough" evidence

We don't need an RCT of everything. What we need is "good enough" evidence, and that means understanding how close our quasi-experiments can get to randomised conditions, and creating good-enough comparison groups from population-wide databases. That will provide good-enough evidence, especially if it's located within existing service systems. The quasi-experimental study of the New Zealand Family Start Home Visiting Programme (Ministry of Social Development, 2016) was entirely created using administrative data. That's an example of "good enough" evidence. It's cheap and it leverages off already funded information systems.

I lead the EMPOWER Centre for Research Excellence in South Australia, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. This is an interdisciplinary collaboration across health service delivery and researchers. It involves pragmatic RCTs, co-creating natural experiments and significant amounts of administrative data linkage. We currently hold extensive data on about 300,000 South Australian children born from 1999 onward. This is an important platform for delivering cost-effective, good-enough evidence.

To support this sort of evidence-building agenda, research-funding agencies need to be much better at actively managing their research portfolios. Currently, it's a case of "let a thousand flowers bloom". One year, something pops up and the pretty ones get funded and then a couple of years later, a very similar thing pops up and it gets funded as well. Unfortunately, there appears to be little corporate memory around these investments or an explicit strategy of managing a portfolio of integrated research investments to progressively build an evidence base for early intervention in 21st-century Australia. Program commissioners who buy interventions also need to be more savvy about what we mean by better quality evidence and what standards of evidence are needed.

I will conclude with a quote from Ed Zigler (2003), who is widely known as the father of Head Start - the iconic US kindergarten program begun as part of the President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty in the mid-1960s.

Are we sure there's no magic potion that will push poor children into the ranks of the middle class? Only if the potion contains health care, child care, good housing, sufficient income for every family, child rearing environments free of drugs and violence, support for all parents in their roles and equal education for all students in schools - without these necessities, only magic will make that happen. (p. 10)

Endnote

1 Other recent social policy evidence reviews have been conducted by the Early Intervention Foundation in the UK, and the Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit (Superu) in New Zealand.

References

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2016). From best practices to breakthrough impacts: A science-based approach to building a more promising future for young children and families. Cambridge, MA: Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Retrieved from <www.developingchild.harvard.edu>.

- Ministry of Social Development. (2016). The impact of the Family Start Home Visiting Programme on outcomes for mothers and children: A quasi-experimental study. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Social Development. Retrieved from <www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/evaluation/family-start-outcomes-study/family-start-impact-study-report.pdf>.

- Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation (OPRE). (2016). Home visiting programs: Reviewing evidence of effectiveness. Washington DC: Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from <homvee.acf.hhs.gov/HomVEE_Brief_2016_B508.pdf>.

- Zigler, E. (2003). Forty years of believing in magic is enough. Social Policy Report, 17(1).

John Lynch is Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at the University of Adelaide, South Australia. He also leads an NHMRC funded Centre for Research Excellence (2015-2020) called EMPOWER: Health systems, disadvantage and child-wellbeing. This article is based on the keynote address given by John Lynch at the 16th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference: Research to results - Using evidence to improve outcomes for families, Melbourne, 6 July 2016.