Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care, Wave 2 Research Report

Transitioning to post‑care life

Download Research report

This report contains key findings from the second wave of data collection for Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care. The report provides a snapshot of how young people in Beyond 18 are faring after leaving out-of-home care (OOHC) in Victoria and focuses on some key aspects of their transition to adult life. The findings in this report are drawn from Wave 2 of the online Survey of Young People and from qualitative interviews with young people participating in Beyond 18.

This report contains key findings from the second wave of data collection for Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care. The report provides a snapshot of how young people in Beyond 18 are faring after leaving out-of-home care (OOHC) in Victoria and focuses on some key aspects of their transition to adult life. The findings in this report are drawn from Wave 2 of the online Survey of Young People and from qualitative interviews with young people participating in Beyond 18.

The study found that care leavers participating in the Beyond 18 study had generally poorer mental health, employment and education outcomes than other young people their age. They were also more likely to have children of their own. Data analysis did not reveal a specific subgroup of young people who were doing better or worse on most or all indicators; rather, most of the study population faced at least some life challenges. A small group of young people appeared to have had a relatively 'smooth' transition, with an early transition into safe and stable housing, good social relationships and relatively good educational attainment; however, this group was too small for the analysis to detect common characteristics associated with good outcomes.

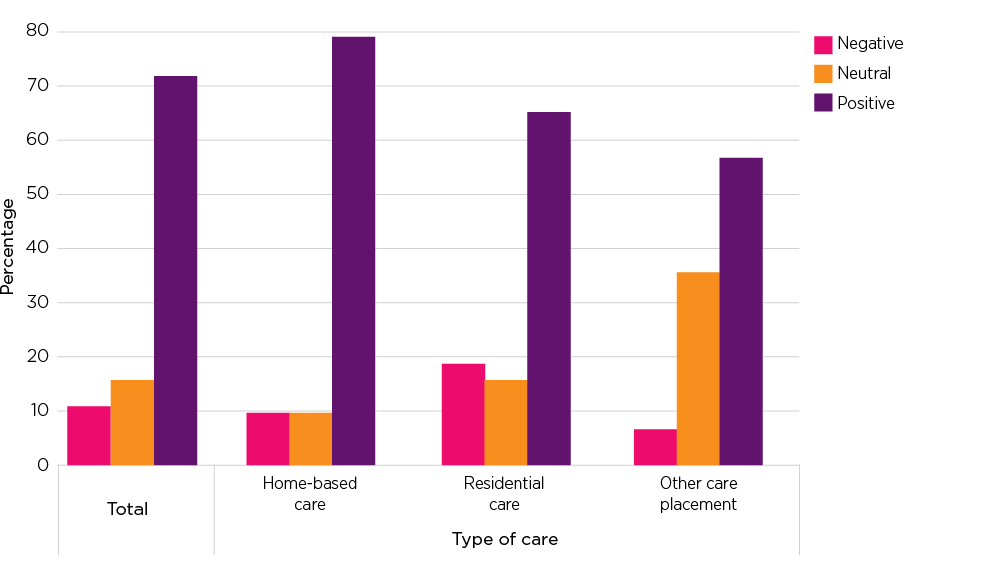

Young people exiting residential care had poorer outcomes on some measures than young people from home-based care placements such as kinship care or foster care. Specifically, although young people exiting residential care had similar employment and education outcomes to the rest of the study population, they reported higher levels of financial stress, greater psychological distress and a reduced sense of control over their lives. The qualitative interviews also indicated that young people from residential care could have difficulty maintaining social relationships while living in OOHC and could transition with smaller social networks. However, residential care leavers were also more likely than other care leavers to maintain contact with support services and former workers after leaving care. The qualitative interviews also indicated that some residential care leavers had been able to effectively use the supports available to them and had moved into stable and secure housing and/or had explored educational opportunities.

This is the second of three research reports on the Beyond 18 study. The first report included findings from the first wave of the Beyond 18 Survey of Young People and the surveys of carers and caseworkers and focused on the key elements of young people's preparations for leaving OOHC, such as formal transition planning and the development of independent living skills. This report focuses more explicitly on young people's lives and outcomes after leaving OOHC. Further exploration of the factors associated with better or worse transition outcomes will be undertaken in Wave 3 and included in the third and final Beyond 18 research report.

Key findings

This report contains findings from the second wave of data collection for Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care (hereafter referred to as 'Beyond 18'). The report focuses on some key aspects of young people's transitions to adult life after leaving out-of-home care (OOHC) in Victoria. The previous Beyond 18 research report (see Muir & Hand, 2018) described the circumstances of young people in the period before leaving care. In this report, we provide a snapshot of study participants' post-OOHC circumstances and explore some of their transition experiences. In particular, this report addresses some of the key domains of post-OOHC life such as accommodation, employment and income as well as health and wellbeing topics such as life satisfaction, suicide, self-harm, psychological wellbeing and mental health.

At the time of writing, more than three quarters (77%, n = 97) of the young people still in the Beyond 18 study had left OOHC. This report focuses on this cohort of care leavers. However, where relevant, the report also includes findings from the participants still in an OOHC placement.

As well as being used to describe young people's post-OOHC lives at the time of Wave 2, data from the Wave 2 surveys were analysed to explore possible associations between young people's post-OOHC outcomes and in-care experiences, such as in-care placement type, and/or personal characteristics, such as gender and location. Where meaningful associations or differences were found, they have been included in this report. Results that were not statistically meaningful and/or where the cell sizes were too small to allow for meaningful conclusions are generally not reported here but may be further explored in the final (Wave 3) Beyond 18 report. The final report will also explore associations between in-care experiences and post-OOHC outcomes in further detail.

1.1 About the Beyond 18 study

Young people leaving OOHC face a number of life challenges. Although there are few comprehensive studies on care leavers' longer-term life outcomes, existing research suggests that care leavers have higher than average risks of homelessness, substance abuse and contact with the criminal justice system. They also commonly have poorer health, education and employment outcomes than the non-care population (Mendes, Johnson, & Moslehuddin, 2011). However, the lack of systematically collected and/or published data on young people after they leave care means that there is limited empirical evidence about post-OOHC pathways or outcomes.

The Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)1 commissioned the Beyond 18 study in 2012 with the aim of improving understanding of the critical factors associated with successful transitions from care. The study aims to do this by exploring young people's preparations for leaving care and their outcomes following transition. The current phase of the study aims to address the following research questions:

- What are young people's main needs when transitioning from OOHC and after they leave care?

- What are young people's outcomes after leaving care?

- How do young people's post-OOHC outcomes vary according to care experiences or demographic characteristics?

- How do they compare with appropriate benchmarks including community norms?

- What are the main contributors to young people's post-OOHC outcomes?

- What are the main barriers to young people having positive post-OOHC outcomes?

1.2 Research methods

The Beyond 18 study has three main components:

- a longitudinal survey of young people

- annual online surveys of carers and caseworkers

- analysis of an extract of anonymised DHHS Client Relationship Information System (CRIS) data.

These components of the Beyond 18 study were outlined in the previous Beyond 18 research report (Muir & Hand, 2018). This research report focuses solely on the first of the three components: the Longitudinal Survey of Young People. The current surveys of carers and caseworkers and the results of the CRIS data analysis will be discussed in the final 2019 research report.

The Survey of Young People consists of three waves of annual data collection from young people who have spent time in statutory care in Victoria after they turned 15 years old. Data are collected through an annual online survey and through qualitative interviews with a subset of survey participants. The first wave of the survey recruited young people aged 16-19 years at the time they entered the study. Most young people were recruited into the study via their carers or caseworkers with their responses collected via an online survey.

The key focus of this report is Wave 2 of the Survey of Young People. This wave focused on participant outcomes and the transition into post-OOHC life. It included questions about young people's accommodation, health and wellbeing, education and sources of income. These items were designed to track participant outcomes over time.

The Wave 2 Survey of Young People was delivered in two closely related versions: one for continuing participants (who had completed the Wave 1 survey) and another survey for new participants. The survey for new entrants was based on the original Wave 1 survey - in order to collect the same baseline data of new participants as had previously been collected of continuing participants - but it also included many of the core elements of the Wave 2 survey for continuing participants. However, to reduce the burden on new entrants, they were not asked the most sensitive Wave 2 questions concerning self-harm and suicide or contact with their biological family. In most instances in this report, the data from the two surveys were combined; where this is not the case, this is indicated in the text.

New participants were allowed to enter the study to mitigate some of the expected high attrition rates of this highly mobile group of young people as well as to allow eligible young people interested in the study to participate even after Wave 1 had closed.

Continuing participants entered the survey via a personalised link sent to them via email or text message. New participants entered the study through the study website or open link contained in the study's promotional materials. The majority were alerted to the study by their leaving care or OOHC workers or by promotional materials distributed to relevant community organisations. The Wave 2 survey opened at the beginning of July 2016 and closed in July 2017.

In-between each wave of the online survey, a selection of study participants has been invited to complete a short qualitative interview. These interviews are intended to supplement the main survey data collection. Although such interviews were not a part of the original study design, they were added to the study to collect additional contextual information and to allow young people to speak, in their own words, about their care experiences and preparation for adult life.

For the first round of interviews, respondents to the Wave 1 online survey were asked to indicate their willingness to participate in an interview. Subsequently, 32 young people participated in a semi-structured telephone interview about their in-care experiences, experiences with case workers, service use, social supports and post-OOHC accommodation (where relevant). Thematic analysis of the interview responses and interviewer notes was undertaken to identify key themes and patterns in participant accounts.

The second round of interviews commenced after the Wave 2 survey. At the time of writing 14 interviews had been completed. The target sample for this round of interviews is 30 care leavers and the sampling strategy aims to include a range of experiences and participant characteristics including care placement type and geographic location. These interviews have focused on post-OOHC outcomes such as accommodation and young people's perceptions of their readiness to leave care. Where relevant, findings from the first two rounds of interviews are included in this report to provide some context for the survey findings. The qualitative data can provide a deeper understanding of individual experiences of transition, and post-transition life, and will be discussed in greater detail in the final Beyond 18 report. However, because the second round of qualitative interviews were still in progress at the time of writing, the interview data have yet to be systematically analysed and thus form a relatively minor part of this report.

1.3 Study limitations and sampling issues

Beyond 18 is a relatively small study with a small sample. As such, there is a limited opportunity to meaningfully explore the experiences of specific subgroups within the survey data. As we noted in the previous Beyond 18 report (see Muir & Hand, 2018), the lack of a sampling frame from which to identify and recruit participants has also meant that the study relied on young people to self-select into the study; most did so after hearing about the study from carers, care workers or youth and community sector organisation (CSO) workers. Subsequently, the researchers were unable to control the composition of the study sample and it is notably skewed; for example, towards female participants (71% of the Wave 2 study population).

Because sector workers and CSOs were crucial in promoting Beyond 18, it is also likely that the study over-sampled young people with relatively high levels of contact with service providers, such as those living in residential care or those in contact with Leaving Care or youth services. This specific form of over-sampling benefits the study because it allows for the comparison of the especially vulnerable population of residential care leavers with the numerically larger population of young people from home-based placements (i.e. foster care and kinship care). However, it is probable that the study has under-recruited young people from kinship care placements and from the hard-to-reach population of young people who have lost contact with all services. More generally, the lack of available statistics about the broader cohort of care leavers born between 1996 and 2000 makes it difficult to know how representative the study is or how study respondents differ from non-respondents. Subsequently, generalising from the survey respondents to the larger population of care leavers should be done with care.

An additional limitation of the Wave 2 study was the high rates of attrition among continuing participants: 87 out of the original 202 young participants (43%) completed a Wave 2 survey. The risk of high attrition was anticipated so the researchers undertook top-up recruitment of new participants to increase the size of the sample. Strenuous efforts to keep in contact with participants between surveys was also undertaken, and young people who did not complete a Wave 2 survey will still be invited to complete Wave 3. Nonetheless, high attrition presents a challenge to longitudinal studies because it reduces the sample size and can introduce bias into the sample when continuing participants differ markedly from those who drop out of the study.

In this instance, the sample was significantly reduced in size but the effect was somewhat mitigated by the recruitment of 39 new participants into the study. The demographic characteristics of continuing participants were also broadly similar to those of the total population of Wave 1 participants in terms of the key study variables of gender, age distribution and type of care placement (see chapter 2 for discussion). An exception was the reduction in the number of Indigenous participants, with only a quarter of the original 24 Indigenous participants completing a Wave 2 survey; however, an additional eight Indigenous young people completed a survey for new participants.

It is possible that the lost sample differed from the continuing population in ways that were not visible to the researchers. For example, participants may have elected not to participate, or been unreachable, due to issues known to be associated with difficult transitions from OOHC such as problems with physical or mental health, homelessness, substance abuse or contact with the criminal justice system. It is not possible to know whether there was any such hidden sample bias or what influence it may have had on the study findings.

Overall, the Beyond 18 sample was sufficiently large and diverse to allow for the analysis of correlations between key participant characteristics, such as most recent placement type, and post-OOHC outcomes, such as accommodation. Other recent studies of care leavers have experienced similar or even more severe challenges in recruiting young care leavers (see e.g. McDowall, 2016; Mendes, Saunders, & Baidawi, 2016; Moore, McArthur, Roche, Death, & Tilbury, 2016). The difficulty of recruiting care leavers, or young people in OOHC, in these studies was the result of the absence of a sample frame of care leaver details, high mobility and the rapid life changes (and subsequent lack of availability to participate in research) that many young people experience as they enter adulthood and/or leave state care. Thus, despite its small overall size, the Beyond 18 Survey of Young People remains the largest study of its type undertaken in Victoria.

It should also be noted that some of the young people in Beyond 18 left care several years before completing the Wave 2 survey. Hence, their experiences may not necessarily reflect those of young people leaving OHHC at the time of writing this report.

Just under half (43%, n = 87) of the 202 young people who completed the first Beyond 18 survey participated in Wave 2. An additional 39 young people entered the study during Wave 2. This made a total Wave 2 sample of 126.

In most respects, the demographic characteristics of the Wave 1 population and the combined (new and continuing) Wave 2 population are broadly similar. This suggests that neither attrition between Waves 1 and 2 nor the recruitment of new participants has noticeably altered or biased the Beyond 18 sample (see Table 2.1). Female participants remain over-represented in the study at 71% (n = 90). The proportion of young people from residential care (and/or lead tenant placements) also remains high (41%, n = 52). Given the wealth of previous research suggesting that young people leaving residential care have worse outcomes than other care leavers (e.g. see Del Valle, Lázaro-Visa, López, & Bravo, 2011; Stein, 2008; Vinnerljung & Sallnas, 2008), this means that the Beyond 18 sample can provide valuable information about the outcomes of this especially vulnerable group of young people. The split between metropolitan and regional representation in Wave 2 is also similar to that of Wave 1; just under half (48%, n = 61) of Wave 2 respondents (who told us where they lived) were located in metropolitan areas and 37% (n = 46) lived in regional Victoria.

Some of the main features of the two participant groups are outlined in the sections that follow.

2.1 Continuing participants in Wave 2

The main difference in sample characteristics between the Wave 1 and Wave 2 surveys was due to the aging of the study population. The majority (82%, n = 71) of continuing participants were over 18 years old at the time of the second survey; only 16 young people were aged under 18 and of these only 11 were still in care. The proportion of young people who had left care also increased from 53% (n = 107) in Wave 1 to 87% (n = 76) in Wave 2.

The main noticeable difference between continuing participants in Waves 1 and 2 was the loss of many of the Indigenous participants. Only 7% (n = 6) of continuing participants were Indigenous; this limits the scope of the study to comment on longer-term outcomes for Indigenous care leavers. Wave 2 did, however, retain 28 (32%) young people from regional areas, which provided a sufficient sample to consider differences in experience (such as service access) across regional and metropolitan areas.

2.2 New participants

New participants to the study were broadly similar to those who entered the study at Wave 1. New participants were generally younger than continuing participants at the time of Wave 2 and subsequently there was a higher proportion who were still in care at the time of the survey; the percentage of new participants still in OOHC at the time of the second survey was 46% (n = 18).

Most new participants identified as female, with only 21% (n = 8) of new respondents identifying as male. New participants were slightly more likely than continuing participants to live in regional areas, although only 8% (n = 3) lived in outer regional areas. As was the case with the original Wave 1 participants, young people from residential care comprised just under half of the total sample.

The Wave 2 survey for new participants attracted a slightly higher percentage of Indigenous young people than did the first wave of the first survey (see Table 2.1); however, the total number of Indigenous participants (even when new and continuing participants are considered together) is still too small for meaningful statistical analysis.

| Characteristics | Continuing participants n(%) | New participants n(%) | Total Wave 2 n(%) | Total Wave 1 n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 87(100) | 39(100) | 126(100) | 202(100) |

| Age | ||||

| <18 | 16(18) | 23(59) | 39(31) | 93(46) |

| 18 | 22(25) | 14(36) | 36(29) | 53(26) |

| 19 | 23(26) | 2(5) | 25(20) | 38(19) |

| 20+ | 26(30) | 0 | 26(21) | 0 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 59(68) | 31(79) | 90(71) | 132(65) |

| Male | 27(31) | 8(21) | 35(28) | 66(33) |

| Other | 1(1) | 0 | 1(1) | 2(1) |

| Indigenous identity | ||||

| Not Indigenous | 80(92) | 31(79) | 111(88) | 170(84) |

| Indigenous | 6(7) | 8(21) | 14(11) | 24(12) |

| Prefer not to say | 1(1) | 0(0) | 1(1) | 8(4) |

| Location | ||||

| Major city | 43(49) | 18(46) | 61(48) | 85(42) |

| Regional | 28(32) | 18(46) | 46(37) | 73(36) |

| Other/unknown | 3(3) | 3(8) | 6(5) | 44(22) |

| Care status | ||||

| Left care | 76(87) | 21(54) | 97(77) | 107(53) |

| Still in care | 11(13) | 18(46) | 29(23) | 85(42) |

| Care placement type (current or most recent) | ||||

| Home-based care | 39(45) | 17(44) | 56(44) | 78(39) |

| Residential care | 36(41) | 16(41) | 52(41) | 87(43) |

| Other/unknown | 12(14) | 6(15) | 18(14) | 37(18) |

Note: Percentages may not total exactly 100% due to rounding and/or missing data.

The Wave 2 survey and interviews focused on post-care outcomes.2 Nonetheless, some of the domains of transition planning and preparation that influence post-OOHC outcomes were explored in the Wave 2 data collection and data analysis, albeit in less detail than in Wave 1. In this section, three key domains of transition preparation are explored; where possible, the implications for post-OOHC outcomes are also outlined. The leaving care preparations covered in this section are:

- leaving care ('transition') plans

- independent living skills (such as self-care, budgeting or cooking)

- contact with leaving care services.

3.1 Leaving care plans

State and national policies for care leavers often emphasise the importance of formal transition planning. In Victoria, state guidelines describe transition planning as an 'essential component' of statutory case plans and stipulate that planning should formally commence when young people are 15 years of age and at least 12 months prior to their discharge from care (Department of Human Services [DHS], 2012, p. 4). There is also research to suggest that young people with a transition plan (also commonly described as a 'leaving care plan') tend to have more stable post-OOHC housing and better engagement with education (see Johnson et al., 2010; McDowall, 2016; Purtell, Mendes, Baidawi, & Inder, 2016). The small scale of most leaving care studies means that the causal relationship between possession of a leaving care plan and post-OOHC outcomes is unclear. Johnson and colleagues (2010) suggest that the quality of leaving care plans is the most important issue and that simply completing a plan is not sufficient to influence outcomes. In particular, they suggest that plans that include specific provision for safe and affordable accommodation are more likely to contribute to 'smooth' transitions; those that do not are less likely to be of value.

Despite the generally accepted importance of formal transition planning, past research suggests that planning is often inconsistent in practice and young people are frequently unaware of whether or not they have a transition plan (Beauchamp, 2016; McDowall, 2009, 2016). Few of the young people in Wave 1 of Beyond 18 were obviously engaged in their transition planning. Only 46% of care leavers and 22% of young people still in OOHC reported that they had a transition plan. Participants entering the Beyond 18 study at Wave 2 appeared to have similarly low levels of engagement in formal transition planning; only 22% of young people still in care (n = 4), and 33% of care leavers (n = 11), said that they had a transition plan. Young people's self-reported lack of a formal transition plan did not necessarily mean that they did not have one; rather, it meant that they did not know if they had a plan. However, lack of knowledge about transition plans can be a strong indicator of a lack of meaningful engagement with the planning process and of poor transition preparation (Hall, 2012).

Because so few Beyond 18 respondents knew if they had a transition plan, there was limited scope in the Wave 2 data analysis for exploring what effect, if any, formal plans had on young people's post-OOHC outcomes. Analysis of the Wave 2 data did not find clear correlations between possession of a plan and better (or worse outcomes) in physical or mental health, education or employment but there was a possible connection between formal planning and post-OOHC housing outcomes. Those who had a leaving care plan appeared to be slightly more likely to move into government housing immediately after leaving care than those who did not have a plan or did not know if they had a plan. Young people without a plan were also somewhat more likely to move into informal living arrangements such as living with a carer, friend or relative. However, this result was not statistically significant (p = 0.082) so it is not possible to draw further inferences or to know if this reflects a real difference in outcomes. See chapter 4 for a discussion of post-OOHC accommodation outcomes.

3.2 Independent living skills

For young people in OOHC, assistance with the development of 'life skills', such as self-care, budgeting and cooking, has been identified as international best practice in transition planning and as one of the 'pillars' of successful transition from state care (Reid, 2007). The acquisition of living skills can be particularly important for care leavers because they often lack the family supports or help with independent living enjoyed by many other young people their age.

In Wave 1, young people expressed a generally high degree of confidence in their independent living skills, especially in terms of self-care, but they were somewhat less confident about their ability to budget or manage their finances. In Wave 2, continuing participants were asked different questions about their perceived need for help with living skills (before and after transition) but they again indicated that they wanted more assistance with budgeting and dealing with general community services such as Medicare and banks (see Figure 3.1). Nearly half (45%) of the continuing participants in Wave 2 also indicated that they had wanted more help in finding accommodation. This is broadly consistent with the opinions of the OOHC workers (described in the previous Beyond 18 report) that it can be difficult for care leavers to find safe and affordable accommodation (see Muir & Hand, 2018).

Figure 3.1: Perceived need for help with independent living skills

Note: Figure applies to continuing participants only.

The small number of continuing participants still in OOHC at the time of Wave 2 makes it difficult to confidently compare their results to the much larger number of care leavers. However, young people still in care did appear noticeably more concerned about dealing with general community services, such as Medicare (73%), and completing formal paperwork (55%) than those who had left care and were possibly already accessing such services or having to complete paperwork for benefits. In contrast, young people still in OOHC expressed less need for assistance in learning about cooking and finding work than did care leavers; this difference again possibly reflects a difference in life experience pre- and post-OOHC, with care leavers having a greater need to know how to cook than young people still in care.

As we noted in the Wave 1 Beyond 18 report (Muir & Hand, 2018), it is not possible to determine how much young people's confidence in their life skills reflects their objective level of skill, their need for additional training or the quality of any training they received. The qualitative interviews with young people suggested that there was significant variation in the skills training that young people received. Young people were often ambivalent about the value of their life skills preparation. One care leaver, for example, suggested that his skills training had focused too much on cooking and cleaning and not enough on money management. Others, however, suggested that they had little life skills training at all. One young female care leaver stated that she was told what skills she needed for post-OOHC life but was given little opportunity to learn or practise them.

Their way of preparing me was just telling me, 'You're gonna move out and it's going to be really hard. You're gonna have to learn how to cook and you're gonna have to learn how to do this.' But there was no actual preparation. Like they didn't actually teach me how to cook or teach me, 'Hey so when you get your money from Centrelink you're not gonna get it for another two weeks so don't blow it all.' (Residential care leaver, female, Wave 2)

Residential care leavers, in particular, suggested that even when they had some training in living skills, they were often not able to put their skills into practice because most tasks in their care unit were performed by residential care staff. As a result, adjusting to independent living could be challenging.

It sounds really silly but the biggest thing was the fact you had to do dishes. I couldn't wrap my head around it. Like in resi [residential care], whatever you use you put in the dish thingy and you walk away and go to bed and come back and they're done … but when you live on your own you have to do it yourself. And it's hard, if you don't do it right you get sick, which I got sick quite a lot. Like you had to learn how to cook food really well or you get sick, which I learnt really badly. Little things like that, like life skills … It is like baby-sitting: they don't teach you how to cook, they don't teach you how to do things. It is like an institution, like a prison. (Lead tenant care leaver, female, Wave 1)

This apparent variation in skills training is potentially related to the generally low priority given to skills training by the care workers participating in Wave 1 of Beyond 18, although most also indicated that their organisation did offer such training. In their 2016 evaluation of the 'Stand by Me' case management program, Purtell and colleagues (2016) also found that there were a number of barriers to OOHC staff effectively addressing life skills. These included the need to deal with other pressing issues such as health, substance use and education and the tendency for young people to over-estimate their skill levels and subsequently refuse skill development opportunities.

3.3 Leaving Care services

Leaving Care services in Victoria consist of statewide, DHHS-funded programs providing information, referral and limited case management support as well as access to brokerage for the purchase of items that assist young people to establish independent lives. This support, as well as mentoring programs and the Leaving Care Hotline, were established following the inclusion of provision for care leavers in the Children Youth and Families Act 2005. These services are operated on behalf of DHHS by a range of community service organisations and there can be considerable variance in the ways in which services are offered. Subsequently, although care leavers potentially have a number of support services available to them, accessing services can mean navigating a complex service system.

On the whole, young people in both waves of Beyond 18 exhibited relatively low levels of knowledge about the supports available to them. In particular, they reported low levels of access to dedicated Leaving Care services. Young people's accounts in the qualitative interviews indicated that when they did access Leaving Care-related services, it was not always timely.

My youth refuge worker put me in touch with [not-for-profit service provider] and springboard … I didn't even know such things existed until I got put into a youth refuge. (Residential care leaver, female, Wave 1)

Just under half (47%) of care leavers reported that they had had contact with Leaving Care services while just over half (51%) reported that they had received Leaving Care funding such as the Transition to Independent Living Allowance (TILA) and/or brokerage funding. Of those who did not receive funding, nearly two-thirds (62%) thought they had needed financial assistance with costs associated with setting up house, such as buying furniture or paying rental bonds, but had been unable to get it or did not know it was available. The reasons for this inconsistent service access - beyond the system's complexity - are unclear but in the previous wave of Beyond 18 surveys, OOHC and leaving care workers reported that Leaving Care services, and other relevant community services such as mental health support, were often concentrated in metropolitan areas and over-subscribed and had long waiting lists or had restrictive eligibility requirements that excluded clients with high needs.

The Wave 1 and 2 qualitative interviews showed a similarly mixed picture of service access and knowledge about services. Some young people, for example, reported that their OOHC case workers, or Leaving Care workers, had been able to use their professional networks or sector knowledge to refer them to services that mostly met their needs:

I've got connected to [Leaving Care agency] when I left, and … pretty much any time I've needed something essential, they've been able to help me out with that. (Foster care leaver, female, Wave 2)

Other young people, however, had not been referred to Leaving Care services, or had little contact with them. Nor did they always have the contact with other services, such as mental health supports, that they felt they needed. Although the OOHC workers in Wave 1 of Beyond 18 suggested that there could be a range of barriers to accessing appropriate services, it is not clear why the young people in this study had such inconsistent experiences of support. However, a recurring theme in the Waves 1 and 2 interviews with young people was the effect of staff turnover on care experiences. In particular, participants suggested that newly assigned caseworkers could have limited knowledge of the young person's needs or of previous arrangements for support. As a result, some young people stated that they had to start over again in explaining their needs and that this could result in delays in accessing services. New workers were also sometimes described as lacking knowledge of available services, particularly if the worker came from a different geographic area or service context.

[The worker] just seemed lost and like she didn't know what she was doing. I think she was new to the area and didn't know where to go to find services. (Foster care leaver, female, Wave 2)

Helping young people find (and maintain) safe and secure housing after they leave care is perhaps the most pressing issue in leaving care research, policy and practice. Research on housing outcomes suggests that stable post-OOHC housing can help provide care leavers with a stable base for obtaining social supports and for exploring education, training or employment options (Forbes, Inder, & Raman, 2006). However, there is also a lot of Australian and international research that indicates that care leavers' commonly experience housing instability in the first few years after transition and that they are at high risk of homelessness due to limited financial resources, high rates of mental illness, substance abuse and a lack of family or social supports (Dworsky, Napolitano, & Courtney, 2013; Johnson & Chamberlain, 2008; Johnson et al., 2010; Mendes, Johnson, & Moslehuddin, 2011). Although there are no official statistics for the numbers of care leavers who become homeless, a recent Australian study of young people who had experienced homelessness found that 63% of respondents had spent time in OOHC. Young people from residential care were also the most likely to become homeless (Flatau, Thielking, MacKenzie, & Steen, 2015; also see Ritson, 2016).

Consistent with this research, concerns about housing have been evident in all waves of Beyond 18. In the first Beyond 18 Survey of OOHC and Leaving Care Workers, respondents identified 'finding accommodation' as the most important task for young people leaving care and for the people supporting them. Workers also expressed concerns about the apparent shortage of safe and affordable housing options such as secure public housing and long-term supported housing. Housing and accommodation again emerged as key issues in the Waves 1 and 2 qualitative interviews and the Wave 2 survey. These findings are discussed below.

4.1 Where care leavers live: types of accommodation

The young people in Wave 2 moved into a range of accommodation types after leaving OOHC (see Table 2.1). Nearly a third (30%, n = 21) of continuing participants had their first post-care placement in some form of supported or public housing (not including emergency or crisis accommodation) while close to half (46%, n = 32) moved into 'informal housing'. This category of housing includes all forms of housing where the young people did not have a formal housing contract but instead stayed with their parents, friends or partners, other family members or former carers. The largest proportion of this group lived with kinship or foster carers immediately after the end of their care order (38%, n = 12). Seven respondents (13%) reported that they had lived in crisis accommodation or had no fixed residence after first leaving OOHC; as such they met widely used criteria for homelessness (Chamberlin & MacKenzie, 2008).3

Placement type was the clearest predictor of what kind of housing young people would move into when they left care. Almost two-thirds (62%) of young people from home-based care placements (such as kin or foster care) reported living in informal housing immediately after the end of their order. In contrast, young people from residential care were less likely to move into an informal arrangement and more likely to rely on public or supported housing (see Table 4.1).

| Care type | Private housing n(%) | Public/supported housing n(%) | Informal housing n(%) | Total* n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 16(23) | 21(30) | 32(46) | 69(100) |

| Home-based care | 6(21) | 5(17) | 18(62) | 29(100) |

| Residential care | 8(26) | 14(45) | 9(29) | 31(100) |

| Other/unknown | 2(22) | 2(22) | 5(56) | 9(100) |

Note: Table refers only to continuing participants. Excludes claimed primary homelessness and emergency and crisis accommodation. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

There is insufficient data to explain the different housing trajectories of the two groups or what this means for longer-term housing stability. The findings may reflect the differing availability of options for post-OOHC housing. That is, residential care leavers may be more likely to rely on the support of workers or Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) to find housing, in part, because they are less likely to have the option of staying with a foster or kinship carer (see chapter 6 for a discussion of social relationships; also see AIHW, 2016a). However, the difference does not necessarily translate to better or worse outcomes for either group of young people. Secure public or supported housing can, for example, promote a form of life stability that enables young people to focus on other areas of their lives (Johnson et al., 2010). Informal arrangements can also be stable, with a handful of respondents to the qualitative interviews indicating that they had stayed on with their carers after transition as members of an extended 'family'.

However, the Wave 1 interviews indicated that not all such informal arrangements were permanent and that some young people were 'couch surfing' because they lacked other options. Similarly, although private rentals are often the first choice of housing for young people in the general community, they can be difficult to maintain for young people with limited life skills, low income and few social supports (see chapter 5 for a discussion of young people's finances). Hence, the housing type, as such, was not an indicator of suitability or stability; rather, as Stein (2012) suggests, what matters is that housing is affordable, stable, safe, close to services and existing supports, and has access to transport, education, training and employment opportunities. Some of these qualities of suitable housing, and its importance for other aspects of care leavers' lives, are evident in the case study below.

Case study: Finding secure supported housing

For the few months before she left care, Rose* lived in a Lead Tenant arrangement. Rose's Lead Tenant case manager was concerned that Rose had nowhere to go when she turned 18 and would be 'turned out on the streets'. As a result, her case manager used her sector knowledge, and network of contacts, to find Rose somewhere to live.

She'd been around and she'd worked in a lot of services and knew a lot of people and could say, 'if you go to this person … they can help you with this'.

After a period of searching, Rose's case manager found her a place in a supported housing program that provided self-contained units to young people who had agreed to stay in education, employment or training. At the time of her interview, Rose had been in the accommodation for nearly a year. Rose observed that on her office-of-housing forms she was listed as 'homeless or at risk of homelessness' because she lived in supported housing and was part of a program to address homelessness. However, she also said that her lease in the unit was for two years. This, she thought, meant that she was better off than if she was in a private rental. The agreement to stay in education suited Rose because, after an earlier period of not attending school, she had realised, 'I really appreciated school … I love education.' Rose's two-year lease offered her stability and the safety and relative quiet of her unit allowed her to focus on her studies, complete Year 12 and enrol in university.

*This is a pseudonym

However, although residential care leavers' higher rates of reliance on supported or government housing did not necessarily indicate poorer housing outcomes, they did seem to be reliant on such housing for longer periods than other young people. Overall, older care leavers were more likely to live in private housing options (e.g. private rental or owning their own house) than their younger peers: 45% (n = 22) of care leavers aged over 19 were in private housing at the time of the Wave 2 survey compared to only 23% of 18 year olds (see Table 4.2). However, government or supported accommodation remained a common form of housing for residential care leavers regardless of their age. This is suggestive of a more extended reliance on government or CSO supports that is most likely due to continuing low income and/or continuing difficulties finding or maintaining other forms of housing.

There was also some (albeit not statistically significant) difference between the housing types of regional and metropolitan respondents, with regional respondents less likely to live in supported housing and more likely to be in private or informal housing arrangements. The small numbers make it difficult to interpret this difference but if it does indicate a real difference in the broader cohort, it could be explained by lower private rental costs and a lack of public or supported housing in regional areas.

| Private housing n(%) | Public/supported housing n(%) | Informal housing n(%) | Total n(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 31(35) | 25(28) | 33(37) | 89(100) |

| Age | ||||

| <18 | 2(22) | 1(11) | 6(67) | 9(100) |

| 18 | 7(23) | 12(39) | 12(39) | 31(100) |

| 19+ | 22(45) | 12(24) | 15(31) | 49(100) |

| Last care placement type | ||||

| Home-based care | 12(33) | 7(19) | 17(47) | 36(100) |

| Residential care | 17(40) | 16(38) | 9(21) | 42(100) |

| Other/unknown | 2(18) | 2(18) | 7(64) | 11(100) |

| Location | ||||

| Major city | 11(26) | 16(37) | 16(37) | 43(100) |

| Regional | 13(42) | 5(16) | 13(42) | 31(100) |

Note: Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

4.2 Housing stability and mobility

Simply finding accommodation after leaving care is not the only concern for care leavers. Housing stability after leaving care is important for young people's ability to start building an independent life and to enter education or employment. Although moving house is not in itself an indicator of housing instability, frequent moves can indicate instability and subsequent life disruptions. Moves can also incur a financial cost, as young people have to move belongings and reconnect utilities, as well as potentially move young people away from existing services and/or education and employment opportunities.

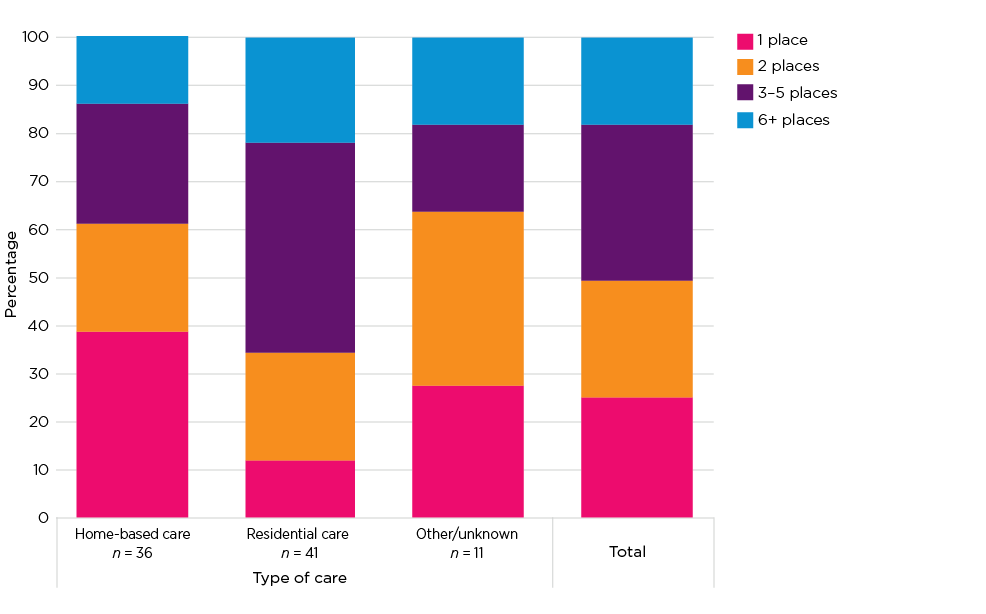

Consistent with most research on Australian care leavers (e.g. see Moslehuddin, 2011), the Wave 2 survey found high levels of housing mobility after the transition from care, with a quarter (26%, n = 20) of care leavers (continuing participants only) moving three or more times in the year preceding the survey (see Figure 4.1). Young people leaving residential care again appeared to have a different post-OOHC accommodation trajectory to young people from other placement types; in particular, they were appreciably more mobile. Two thirds (66%, n = 27) of young people leaving residential care had experienced more than two housing moves since leaving care, compared to 39% (n = 14) of young people who transitioned from home-based care placements.

Figure 4.1: Number of places lived since leaving care (by last care placement type)

The specific factors underlying this cohort's accommodation trajectories are not yet clear. However, young people participating in the qualitative interviews often described complex housing trajectories, with high rates of mobility in the first few years after leaving care and attributed this to lack of money for rent, living in short-term accommodation and relationship challenges. A lack of available long-term housing, for example, could mean that young people were frequently placed in temporary accommodation. One residential care leaver told us she and newborn baby had been placed in serviced apartments for several months while she waited for a social housing place to become available. Others moved on because the housing was too far from supports or was in poor repair and they subsequently moved into temporary or emergency housing while waiting for more suitable options.

Personal relationships could also play an important role in care leavers' housing trajectories. The Wave 1 survey identified peer problems as a significant issue for many young people in Beyond 18 and participants in the Wave 1 and 2 interviews described conflict or relationship breakdowns with housemates as a cause for changing accommodation. Care leavers' frequently complex relationships with their biological family could also affect their housing stability. Although some young people elected to move in with family after transition, these arrangements did not always last (see also Purtell et al., 2016). One care leaver, for example, described moving back and forth between her parents' and boyfriends' houses as her personal relationships ruptured and were repaired.

Left care to go back to my parents, lasted a few months, got kicked out and moved in with my boyfriend for a few months. Then I went back to parents' house, lasted about six months before being kicked out again. Stayed with my boyfriend, the current one not the old one, for about six months before moving back in with my parents. I've been here for about a year.

Overall, the Wave 2 research findings did not identify any particular group of young people, or cluster of respondent characteristics, that were strongly associated with housing stability (or instability). Placement type appeared to be correlated with mobility in the period immediately before the Wave 2 survey but it is not yet clear if this mobility was necessarily a result of housing instability. Similarly, although some young people in the Wave 2 survey and qualitative interviews described a relatively stable transition into post-OOHC housing (i.e. where they immediately moved into, or stayed in, long-term housing), the relatively small size of this group hindered the identification of any distinguishing characteristics.

More information on young people's housing trajectories, including their mobility between survey waves, is being collected in the Wave 3 survey and will be analysed for the final Beyond 18 report. This will provide additional data that could further illuminate the factors underlying housing stability and its relationship to other life circumstances or experiences.

3 There is no universal definition of homelessness. One of the more widely used comes from Chamberlain and Mackenzie's (2008) five groups of housing outside the minimum community standard. These are Marginally housed: people in housing situations close to the minimum standard; Tertiary homelessness: people living in single rooms in private boarding houses without their own bathroom, kitchen or security of tenure; Secondary homelessness: people moving between various forms of temporary shelter including friends, emergency accommodation, youth refuges, hostels and boarding houses; Primary homelessness: people without conventional accommodation (living in the streets, in deserted buildings, improvised dwellings, under bridges, in parks, etc.); and Culturally recognised exceptions: where it is inappropriate to apply the minimum standard, e.g. seminaries, gaols, student residences.

Young people's experiences of education are a key part of their preparation for adult life and a major contributing factor to their later employment outcomes. The previous Beyond 18 survey found that a significant proportion of young people in the study had left school before completing Year 12 (see Muir & Hand, 2018). Failure to complete school can have a significant effect on young people's later life outcomes. Early school leavers tend to have poorer employment outcomes, and worse physical and mental health, than those who complete Year 12. Completing Year 12 while at secondary school has also been associated with better employment, health and wellbeing outcomes than finishing Year 12 later (e.g. at TAFE) (Lamb, Jackson, Walstab, & Huo, 2015).

In this section, we revisit young people's educational attainment to see if there have been changes in the overall picture since the Wave 1 survey. This section also looks at young people's employment outcomes, sources of financial support and their perceptions of financial security.

5.1 Education

Harvey, McNamara, and Andrewartha (2016) note that many children and young people entering OOHC are already educationally disadvantaged by demographic factors such as low socio-economic status and regional and/or Indigenous backgrounds. This background can be exacerbated by later in-care experiences such as placement instability or lack of support for completing education. A recent pilot study of the delivery of an accredited Education Employment Training (EET) program found that young people in residential care, in particular, were difficult to recruit and keep in the program because of their aversion to filling out enrolment paperwork, the prevalence of residential unit incidents and difficulties with family relationships. Peer group social norms (within the unit) that disparaged the value of education and encouraged risk-taking behaviour were also cited as a factor (Hart, Borlagdan, & Mallett, 2017).

As a result of these challenges, young people from OOHC often have poor education outcomes. A recent AIHW report found that children on OOHC orders had poorer results than the Australian average on national reading and numeracy benchmarks (AIHW, 2017). Care leavers are also significantly under-represented in higher education and thus generally miss out on the 'lifetime advantages' conveyed by higher education (Harvey et al., 2016, p. 94).

The educational challenges faced by young people from OOHC were evident in the Wave 1 Survey of Young People. School leavers had low rates of school completion to Year 12 (25% of school leavers) and a high proportion (26%) had not completed Year 10. These educational outcomes were largely repeated in Wave 2 (see Table 5.1).

| Level when left school | Continuing n(%) | New n(%) | Total (n = 126) n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed school | 17(20) | 2(5) | 19(15) |

| Left school before completed | 40(46) | 13(33) | 53(42) |

| Still in school | 25(29) | 21(54) | 46(37) |

| Prefer not to say | 5(6) | 3(8) | 8(6) |

Notes: Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Rates of school completion did not improve between Wave 1 and Wave 2. Only 15% of new and continuing participants (25% of school leavers) had completed Year 12 (at school) at the time of the survey and 29% (n = 22) of school leavers had not completed Year 10.4 As we noted in the previous report, this finding suggests that a high proportion of young people in OOHC are not meeting the Victorian government's minimum school-leaving age of 17 or the mandatory requirement that all students complete Year 10.

However, there were significant rates of re-engagement with education and more than half of respondents (54%, n = 68) had at least started further study at the time of Wave 2. Although only five respondents had undertaken university study, more than a third (36%, n = 25) of young people had worked towards a Certificate III or IV at a TAFE college. Several young people (15%, n = 10) undertaking further education also reported that they were either currently undertaking or had previously completed Years 11 or 12 after leaving school (e.g. through VCAL or VET courses at TAFE). The reasons why young people re-engage with education, or the common features of young people who undertake further education, were not evident in the Wave 2 data. However, more information about education and completion rates will be collected in Wave 3.

5.2 Income and employment

Because many of the young people in Beyond 18 are still at school or in further education it is not yet possible to meaningfully explore the influence of educational attainment on income or employment outcomes. However, it was possible to explore young people's sources of income and to compare these to the general population. Overall, we found that very few young people were in employment of any sort. Just over a third (37%, n = 43) of participants received any income from wages or salary.5 Among continuing participants who received income from employment, only six (21%) worked full-time (>35 hours a week) while 61% (n = 17) worked less than 20 hours a week.6 Because the number of young people earning wages or salary was so small it was not possible to determine if there were any specific characteristics associated with employment.

The majority of young people in Beyond 18, including those receiving income from employment, received some form of government benefits (see Table 5.2). Youth allowance was the most commonly received benefit across the study population but rent assistance and parenting payments were also important sources of income.

Youth unemployment figures for the general population are usually high relative to that of the total adult population. For example, Australian youth unemployment for 2017 up until August was 13%; this was more than double the overall unemployment rate (ABS, 2017). However, the Beyond 18 results suggest extremely high levels of unemployment and/or under employment even in comparison to the general youth population.

| In care (n = 27) n(%) | Left care (n = 89) n(%) | Total (n = 116) n(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any government benefits | 13(48) | 65(73) | 78(67) |

| Type of benefit (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Youth Allowance | 9(33) | 46(52) | 55(47) |

| Rent Assistance | 1(4) | 17(19) | 18(16) |

| Parenting payments | 1(4) | 12(13) | 13(11) |

| Disability or Youth disability | 0(0) | 7(8) | 7(6) |

| Other government benefits | 1(4) | 8(9) | 9(8) |

The Wave 3 survey will allow for limited exploration of changes over time in young people's employment, income and working hours but their longer-term employment outcomes will not become clear for several years. However, the generally poor levels of educational attainment described in the previous section suggest that many of care leavers in this study will face challenges in entering or staying in paid employment.

Young people's reliance on Youth Allowance, or on youth wages, are also likely to affect their current quality of life, accommodation options and levels of financial stress (see the discussion below). Youth Allowance, for example, is significantly lower than the adult rate of Newstart. A single young person with no children can receive a maximum of $570.50 per fortnight in Youth Allowance and Rent Assistance; this is nearly $100 less than they would receive on the Newstart allowance and significantly less than the $832.14 per fortnight that the Melbourne Institute had defined as the poverty level for a single, non-working adult at the time of writing this report (Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, 2017).

Similarly, because the majority of young people in Beyond 18 are under 21 (see Table 2.1), many of those receiving income from employment are likely to be on 'junior pay rates' under Australian employment regulations (see Fair Work Australia, 2017). Although young people's incomes are generally expected to be lower than those of older adults, care leavers often do not have the financial support of family that many other young people rely on to supplement the lower incomes they receive when on junior pay rates or Youth Allowance. Subsequently, care leavers are at a higher risk of financial stress and/or hardship than other young people.

5.3 Financial stress

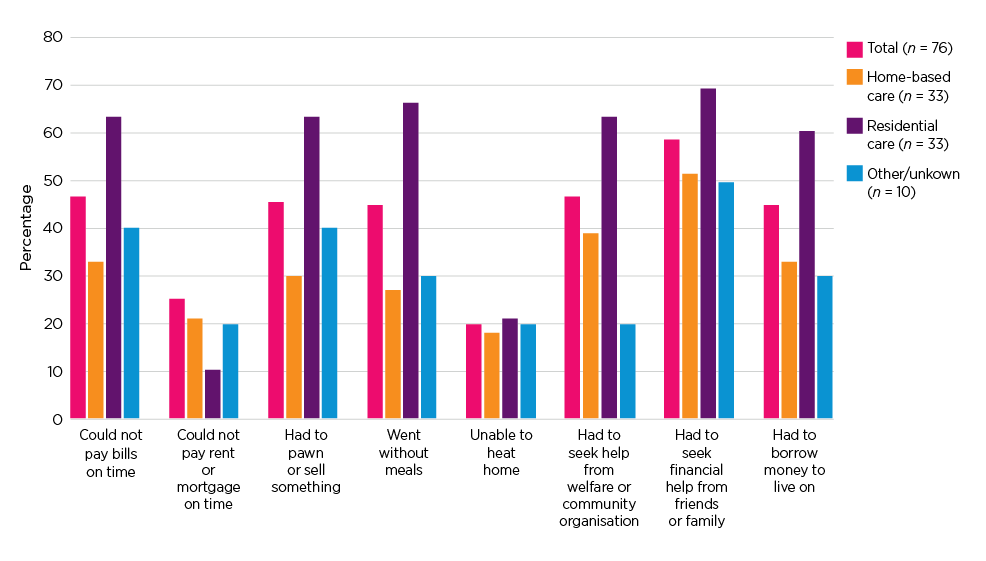

The low levels of employment, and high levels of housing mobility, were also reflected in continuing care leavers' responses to questions about financial stress. Overall, they reported very high levels of financial stress (see Figure 5.1). In particular, just under half of respondents reported that they had been:

- unable to pay bills on time (47%)

- gone without meals (45%)

- had to borrow money just to survive (45%).

One in four participants also reported that they had been unable to pay their rent or mortgage on time. The lower response rate on this measure was indicative of the high proportion of young people in subsidised or supported housing, some of whom do not pay rent and thus did not answer the question. However, the slightly lower levels of stress on this measure (even with the lower response) is suggestive of young people prioritising their housing over other needs.

Again, young people from residential care appeared to have poorer outcomes, suggestive of more challenging transitions, than other care leavers in that they reported significantly higher levels of financial stress on all indicators.

Figure 5.1: Indicators of financial distress

Note: Measure of financial distress only asked of care leavers.

It is difficult to find age comparable data for financial stress among young people in the general community. Although similar measures of financial stress are used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), and the Household Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) survey, statistics on hardship by age group are not publicly available because such measures usually focus on households rather than age groups. However, the recent ABS household expenditure survey (2016) indicated that 14.1% of the lowest household income quintile were unable to pay their bills on time and 6.1% went without meals. This suggests that the rates of financial hardship among young people in Beyond 18, especially residential care leavers, are very high even when compared to less advantaged households in the general population.

4 'Completing high school' in this study - as in other equivalent research - refers to completion of VCE subjects at school. However, school leavers can later acquire equivalent VCAL or VET qualifications through completion of Certificates I and II in a range of vocational training options. These certificate-level qualifications can be completed in further education settings such as Registered Training Organisations and TAFE and may provide pathways to completing Certificate IV, diploma and degree-level qualifications.

5 Three care leavers reported having no income from any source.

6 New participants were not asked about their working hours.

The existing Australian and international research describes at length the generally poorer-than-average health outcomes, and high rates of substance abuse and mental illness, among care leavers and young people in OOHC (e.g. Dworsky et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2011). The Australian Department of Health has similarly identified young people with OOHC experience as 'vulnerable' to poor health because of their previous experiences of trauma or neglect and their frequently inadequate access to health care. They have also characterised young people in OOHC as having a 'notably higher' risk of mental health issues than the general community (Department of Health, 2012, p. 18).

Young people in care also face a range of barriers to accessing appropriate health care, which can be a causal or exacerbating factor for poor health. Barriers to obtaining appropriate care can include carers under-reporting heath concerns until problems become acute and inconsistencies in the transfer of medical records when children change care placement (Department of Health, 2011). Young people's health and access to medical services can also be poor after leaving care. The poor educational attainment, low income, financial stress and insecure housing described earlier in this report are all associated with poor health outcomes, high rates of mental illness and substance abuse (also see Cashmore & Paxman, 2007; Courtney et al., 2011).

In this section, we summarise some of the key findings from Wave 2 survey questions about young people's physical health, their access to health services and their mental and emotional wellbeing.

6.1 General health indicators

The use of mainstream health services by young people in Beyond 18 was relatively high but the use of emergency services or specialist drug and alcohol services was relatively low. Most (84%, n = 106) had seen a doctor at least once in the preceding year and two-thirds (68%, n = 85) had seen a dentist. Self-reported general health was also typically good, with close to half (49%, n = 62) of participants rating their health as very good or excellent and only 10% (n = 12) reporting poor health. Such self-reports, however, do not necessarily indicate high levels of good health. Further, a quarter (23%, n = 29) of respondents also reported a physical disability or chronic health issue and 19% (n = 24) reported an intellectual disability or learning difficulty.

Respondents to other studies of care leavers have also commonly rated their health positively, despite other indicators showing poor access to services or unhealthy lifestyles (e.g. see McDowall, 2009, 2013). This reflects the relative nature of such self-reports; health can be reported as 'good' because it is better than at a previous time or when compared to other people's even poorer health status.

Participants' reported legal and illicit substance use rates did not generally indicate significant differences from the general population. Although it is possible that illicit substance use may have been under-reported, reported usage rates were comparable with other young people in the general population. Alcohol consumption among participants was lower than the Australian average. In comparison to the 14-20% of young people in the general population who have reported drinking alcohol at risky levels (see AIHW, 2017), only one in six participants reported regular alcohol consumption and a quarter (26%) reported that they never drank alcohol at all. However, smoking rates among young people in Beyond 18 were very high: 41% (n = 52) of participants reported regular cigarette use compared with just 13% of 18-24 year olds in the broader Australian population (AIHW, 2016b).

6.2 Mental health and psychological wellbeing

Wave 1 of the Survey of Young People indicated that a substantial proportion of respondents had mental health issues. Over 40% of respondents showed 'very high' levels of difficulties with peers and with emotions on the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) when compared to Australian norms. Because mental health issues among care leavers have frequently been linked with housing instability, unemployment, poor general health and substance abuse (Johnson et al., 2010; Mendes et al., 2011; Stein, 2008), this finding suggested that many of the young people in Beyond 18 were likely to experience significant life challenges.

In Wave 2, two measures were used to explore (continuing) participants' psychological wellbeing: the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6) and the Pearlin Mastery Scale. The K6 measure is a widely used validated scale that can be used to screen for serious non-specific psychological distress and to assess the severity of mental health problems. It contains six questions that ask respondents to rate how often they experienced specific psychological states in the previous 28 days. The Pearlin Mastery Scale is used to assess 'the extent to which one regards one's life chances as being under one's own control in contrast to being fatalistically ruled' (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978, p. 5).7 As such, high levels of 'mastery' can be an important indicator of mental and physical wellbeing and of resilience in the face of hardship or persistent life stresses (see Pearlin & Schooler, 1978; Pudrovska, Schieman, Pearlin, & Nguyen, 2005).

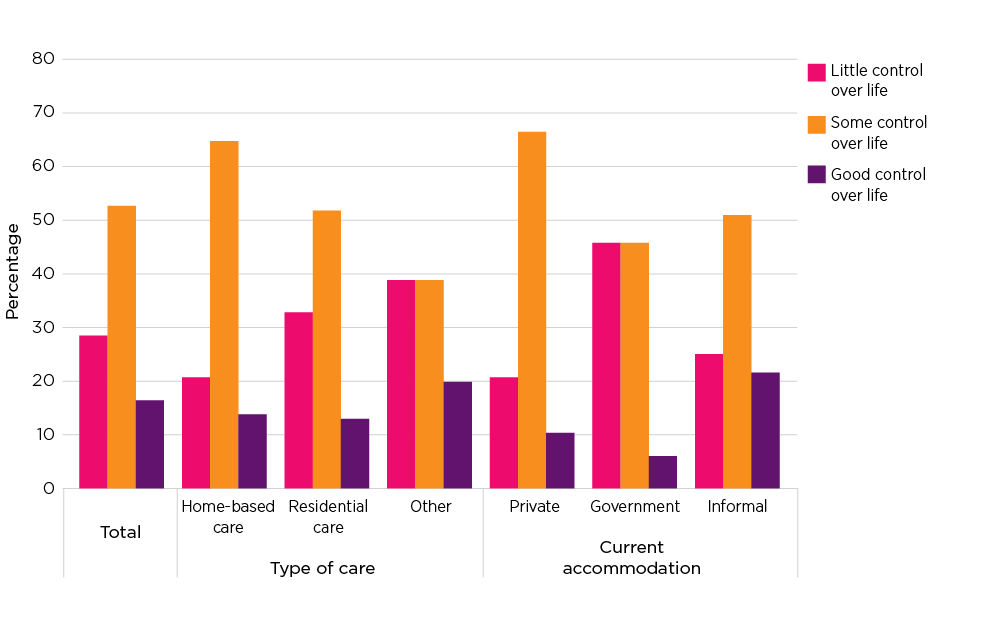

Beyond 18 participant responses to the K6 indicated high levels of psychological distress, with a quarter of participants (26%, n = 23) showing psychological distress at a level that indicates probable mental illness such as depression or an anxiety disorder. Young people's responses to the Pearlin Mastery Scale also indicated relatively poor psychological wellbeing, with less than 20% of respondents reporting that they had a sense of 'good control' over their life and circumstances (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1: Sense of life mastery by care placement type and current accommodation type

A low sense of self-mastery is commonly associated with financial difficulty and with the other life challenges explored in earlier sections of this report (Pudrovska et al., 2005). The qualitative interviews also suggested that the experience of being in OOHC could also contribute to young people's sense that they had little control over their life circumstances. This perception was related to young people's removal from their biological families in the first place and to a subsequent inability to direct important aspects of their lives such as contact with friends, where they lived, where they went to school or the nature and timing of contact with biological family. One young care leaver suggested that:

Kids in foster care haven't been able to control their lives. Because if they could it would be that they want to live with their parents even if it's an unhealthy environment. They want to have that control and they want to be able to not feel like they're going to be forced into life they don't want to. (Foster care leaver, female, Wave 2)

Young people who had transitioned from residential care placements had poorer outcomes on the Pearlin Mastery scale than young people from home-based care placements. Just over a third 34% (n = 11) of young people from residential care reported that they felt 'little' sense of control over their lives. These findings were echoed in the responses of young people living in government or supported housing - the category of housing in which more than a third of young people from residential care lived - who reported marginally lower levels of control than young people living in informal or private housing.

For continuing participants, there was also a strong association between SDQ scores in Wave 1 and mental health outcomes at Wave 2. In particular, young people reporting emotional or peer difficulties in the SDQ were significantly more likely to show psychological distress consistent with mental illness in Wave 2 (on the K6 measure). They were also less likely to report feeling a good sense of control over their lives on the Pearlin Mastery scale. These findings suggest that mental health is an ongoing concern for a significant subset of this population.

A poor sense of life control was also higher among care leavers who reported that they had felt unprepared to leave care. Nearly half (45%) of those who reported feeling 'little' sense of life mastery reported that they had felt 'not at all prepared' to leave care. Psychological distress was also higher among those who reported feeling unprepared to leave care. The nature of the data makes it difficult to determine the direction of this relationship; that is, whether poor mental wellbeing led to feelings of unpreparedness or whether poor preparation for leaving care resulted in poorer mental health outcomes. It could also be a combination of both. Regardless, although this group did not show significant differences from the rest of the study population on other life outcomes, such as employment or education, the findings suggest that they are potentially vulnerable to a range of life challenges in the longer term.

6.3 Suicide and self-harm

There are general concerns about the rates of suicide attempts and self-harm among Australian youth. Lawrence and colleagues' (2015) national study of mental health among children and adolescents found 'particularly worrying' (p. iii) rates of self-harm, depression and suicidal ideation: 11.2% of 16-17 year olds had seriously considered suicide in the last 12 months, 7.8% had made a suicide plan, and 3.8% reported a suicide attempt (Lawrence et al., 2015). Recent results from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) also indicate high rates of self-harm and suicidal behaviours among Australian youth, with one in ten 14-15 year olds self-harming in the last 12 months and 5% attempting suicide (Daraganova, 2017). Among the risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviours are poor mental health, socio-emotional problems (e.g. those measured by the SDQ), past childhood trauma, dysfunctional family relationships and difficult peer relationships (Daraganova, 2017; also see Cash & Bridge, 2009).

Due to the high prevalence of these risk factors in the OOHC population, care leavers are particularly at risk of suicidal behaviours (Department of Health, 2012). This risk was evident in the high rates of suicidal ideation and self-harm among Wave 2 participants (see Table 6.1).8 Among continuing Beyond 18 participants, one in three reported that they had thought about self-harm in the previous 12 months and one in four had hurt themselves on purpose. In comparison, 11.6% of 16-17 year olds in the Department of Health's national study of Australian youth had self-harmed in the previous 12 months (Lawrence et al., 2015). Suicidal ideation was also very high among Beyond 18 participants, with 23% reporting that they had seriously considered suicide, 18% that they had made a suicide plan and 13% that they had attempted suicide in the previous 12 months. Two-thirds of Beyond 18 participants who had made a suicide attempt reported that it was serious enough to receive medical attention.

| In care n(%) | Left care n(%) | Total n(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 11(100) | 76(100) | 87(100) |

| In the last 12 months, have you … | |||

| Thought about hurting yourself on purpose | 2(18) | 29(38) | 31(36) |

| Hurt yourself on purpose | 3(27) | 17(22) | 20(23) |

| Seriously considered suicide | 3(27) | 18(24) | 21(24) |

| Made a suicide plan | 2(18) | 14(18) | 16(18) |

| Attempted suicide | 1(9) | 10(13) | 11(13) |

| Received medical attention for a suicide attempt | 1(9) | 6(8) | 7(8) |

Note: Table refers only to continuing participants.

The rates of self-harm and suicidal ideation among Beyond 18 participants were two to three times higher than those recorded for the general population of 16-17 year olds (Lawrence et al., 2015). Although the differences in age and in sample sizes mean that the Beyond 18 results are not directly comparable to those of Lawrence and colleagues (2015) or LSAC, the Beyond 18 findings clearly show that many study participants are struggling with life challenges and may require significant mental health support.

6.4 Youth justice

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2016b) has observed that Child Protection and Youth Justice services often work with the same population. During 2014-15, 6.3% of young people in OOHC were involved with youth justice services and 5.5% of young people in the Australian child protection system were under youth justice supervision; that is '14 times the rate of youth justice supervision for the general population' with males and Indigenous young people especially over-represented in this dual-order client group (AIHW, 2016b, p. 8).

The overrepresentation of young people from OOHC in the justice system can be attributed to a range of factors, including the association of past abuse or neglect with an elevated risk of engaging in criminal activity (Hart et al., 2017). Young peoples' contacts with police, before they enter OOHC, can also trigger child protection services' involvement with their family and subsequent entry into OOHC. Many such young people will then go on to have more contact with the youth justice system (Victoria Legal Aid [VLA], 2016). Victoria Legal Aid (2016) also suggest that young people in residential care commonly have contact with youth justice because residential unit staff commonly call the police when confronted with challenging behaviours that in other contexts (such as young people living with their parents) would rarely involve the police. This, VLA suggest, can escalate conflict and result in a 'cycle of involvement with the criminal justice system' (2016, p. 2).

The Beyond 18 survey showed similarly high levels of crossover between child protection and youth justice. When reporting on their contacts with youth justice before turning 18, more than half (60%, n = 75) of all participants reported contact of some kind with police or the youth justice system, 32% (n = 40) had been found guilty of a criminal offence and 12% (n = 14) had spent time in a youth justice facility after sentencing. Results were similar for all genders although males were slightly more likely to have been found guilty of a criminal offence (45% vs 28%); this difference was not statistically significant.

Young people's contact with the justice system after they turned 18 remained high but was lower than it had been before they reached adulthood. Over a quarter (27%, n = 19) of continuing participants reported contact with police after they turned 18 and 11% (n = 8) had been found guilty of an offence since becoming an adult. Because the current study was unable to recruit people currently in youth or adult detention, it is possible these figures under-represent youth justice involvement among young people with an OOHC experience.

7 The Pearlin Mastery Scale uses a seven-item scale comprising five negatively worded items and two positively worded items. The negatively worded items require reverse coding prior to scoring, resulting in a score range of 7 to 28, with higher scores indicating greater levels of mastery.

8 Only continuing participants were asked about self-harm and suicide, as this was deemed to be too sensitive and burdensome for new entrants to the study (who were already completing a longer version of the survey).

Many of the challenges associated with transition from OOHC are related to care leavers' lack of social or familial support. Young people in the general community often live with their parents well into young adulthood. For example, at the time of the 2011 Census, over 40% of 22 year olds and one quarter of 25 year olds were still living with their parents (ABS, 2013). Even when young people leave home, they often rely on ongoing family support for an extended period. Not all care leavers lack family or other social supports. This study's findings on accommodation suggested that many care leavers stayed with family, friends or former carers after leaving formal care, even if only couch surfing. Nonetheless, many young people transition into post-OOHC life with limited levels of social support or with complex, and sometimes unsupportive, social and family relationships. This can be a significant causal or exacerbating factor in the financial stress, mental illness and housing instability described in previous sections.

This section explores the findings on young people's relationships with biological family, friends and workers and their sense of felt security. Data on young people's experience of becoming parents themselves is also summarised.

7.1 Contact with biological family