Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care, Wave 3 Research Report

Outcomes for young people leaving care in Victoria

June 2019

Stewart Muir, Kelly Hand, Megan Carroll

Download Research report

Overview

Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care was commissioned by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to increase understanding of young people's experiences of leaving out-of-home care (OOHC). The study's central component was a three-wave online Survey of Young People who had an OOHC experience in Victoria. This survey explored the young people's in-care experiences, sources of income, education, health and wellbeing, social and family relationships and access to services. The survey of young people from OOHC was supplemented by qualitative interviews with care leavers, surveys of OOHC sector workers, surveys of kinship and foster carers and analysis of data from the DHHS Client Relationship Information System (CRIS).

This report focuses on findings from Wave 3 of the Survey of Young People - completed by 126 care leavers - and from 54 qualitative interviews with care leavers that were completed concurrently to the Wave 3 survey. The report explores key aspects of study participants' post-care lives and their views on the key barriers and enablers for achieving better life outcomes.

This is the third and final research report for Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care (hereafter referred to as 'Beyond 18'). It describes the key findings from the third wave of the Beyond 18 Survey of Young People and from 86 qualitative interviews with care leavers undertaken between 2016 and 2018.

This report builds on the previous Beyond 18 reports, which explored young people's preparations for leaving out-of-home care (OOHC) (see Muir & Hand, 2018) and their experiences of transition and post-care life (see Purtell, Muir, & Carroll, 2019) by examining care leavers' life outcomes in terms of financial security, accommodation, education and health. This report also focuses more specifically on young people's accounts of life after OOHC and their thoughts on the key barriers or enablers for achieving better post-care outcomes.

1.1 About the Beyond 18 study

The Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)1 commissioned the Beyond 18 study in 2012 with the aim of improving understanding of the critical factors associated with successful transitions from OOHC. The Beyond 18 study aimed to do this by exploring young people's preparations for leaving OOHC, their experiences of transition from OOHC and their post-OOHC outcomes. This third wave of Beyond 18 data collection particularly aimed to address the following research questions:

- What are young people's outcomes after leaving care?

- What are young people's main needs when transitioning from OOHC and after they leave care?

- How do young people's post-OOHC outcomes vary according to care experiences or demographic characteristics?

- How do they compare with appropriate benchmarks including community norms?

- What are the main contributors to young people's post-OOHC outcomes?

- What are the main barriers to young people having positive post-OOHC outcomes?

Research methods

The Beyond 18 study as a whole had four components:

- the Survey of Young People (from OOHC)

- three waves of qualitative interviews with participants in the Survey of Young People

- two online surveys of carers and caseworkers

- analysis of a data extract from the DHHS Client Relationship Information System (CRIS) database.

The Survey of Young People was Beyond 18's central component and main data source. It consisted of three waves of an annual online survey of young people who had spent time in statutory OOHC in Victoria after their 15th birthday. This age criterion was designed to capture young people's experiences of preparing to leave OOHC. The first wave of young people were aged 16-19 at the time they entered the study. Most were recruited into the study via their carers or caseworkers. The survey was also promoted via social media and through community sector organisations and peak bodies. Each wave of data collection began immediately after closure of the previous wave. The first wave of online data collection started in June 2015 and closed in June 2016, Wave 2 commenced in July 2016 and closed in June 2017. Wave 3 had a shorter data collection period, due to the impending closure of the study, with data collection between July 2017 and March 2018. Participants in each wave of the online survey received a $50 gift card as compensation for their time and effort.

In Waves 2 and 3 of Beyond 18, new participants were allowed to enter the study in order to mitigate the expected high attrition rate of this highly mobile group of young people. This also allowed any eligible, and interested, young person to participate and express their views. Continuing participants entered the survey via a personalised link sent to them via email or text message. New participants entered the study through the study website or an open link contained in the study's promotional materials.

The Wave 3 Survey of Young People was delivered in two closely related versions: one for continuing participants (who had completed one or both of the previous Beyond 18 surveys) and another for new participants. The survey for new entrants was the same as that completed by continuing participants but also included a small number of additional questions, taken from the Wave 1 survey, that collected baseline data.

Beyond 18's second key element was a series of qualitative interviews with a subset of participants from the Survey of Young People. The interviews took place concurrently with the online surveys. A sample of participants were contacted following their completion of a Wave 2 or Wave 3 survey and invited to participate in a qualitative interview. The sample of participants who were invited to complete an interview included a range of participant characteristics and care variables such as care placement type and geographic location. Because the Wave 2 interviews were still in progress at the time of the previous Beyond 18 report, this report draws on the interviews undertaken for both Waves 2 and 3. These interviews were undertaken over the course of 2017 and 2018. (See section 2.2 for details of the participants in the qualitative interviews.)

The interviews aimed to get a more nuanced understanding of young people's experiences of OOHC and post-transition life. They were also an important way in which young people with OOHC experience could tell their stories and voice their opinions about the OOHC and leaving care systems. Some participants also hoped that their participation in Beyond 18 would help other care leavers and improve the OOHC system:

I really hope that the information will help other kids in foster care. Because it's not nice, even if you get through it, it's not nice seeing the only people that you can sort of relate to going through everything and not being able to get past it all … getting into things like alcohol or drugs or getting into bad situations themselves. You know, becoming unwell and really falling off the rails, you know. So … I really hope it does help. Help the system improve and help other kids in the future. (Foster care leaver, female, 22, Wave 3)

The interviews were semi-structured and undertaken by telephone, and lasted between 20 minutes and an hour. Telephone interviews gave participants a high degree of privacy when discussing sensitive subjects and enabled them to fit the interviews into their personal schedule. Interview participants received a $20 gift card in compensation for their time and effort. Thematic analysis of the interview responses and interviewer notes, was undertaken to identify key themes and patterns.

Beyond 18 also included two online surveys of carers (including foster carers, kinship carers and permanent carers) and OOHC and leaving care workers. These surveys were primarily intended to gather additional contextual information to supplement the Survey of Young People. The first of these surveys was run concurrently with Wave 1 of the Survey of Young People; the second opened with Wave 2 of the Survey of Young People and was closed at the same time as Wave 3. This wave of the survey was kept open for the duration of the final two waves. Due to the low number of participants completing these surveys, the study has primarily focused on results from the Survey of Young People.

As part of the Beyond 18 study, an extract of de-identified unit data from the DHHS CRIS database was analysed. This analysis allowed the researchers to discern some key characteristics of the wider cohort of young people in OOHC at the same time as Beyond 18 participants. The results of this analysis are described in section 1.2 and in Appendix A.

Key findings from Wave 1 and Wave 2 of Beyond 18

In this report we will refer back to some of the findings of the previous Beyond 18 research reports and note key areas of continuity and difference. However, to contextualise the discussion of the current report's findings, some of the key findings from those reports are summarised here.

The first Beyond 18 report (Muir & Hand, 2018) drew on data from Wave 1 of the Survey of Young people and from the Surveys of OOHC workers and OOHC carers. These surveys collected baseline information about young people's in-care experiences and explored young people's preparations for leaving OOHC. Transition planning, in particular, was a key focus because of the extensive Australian and international research suggesting that young people can have (relatively) smooth transitions into post-care life when their transition planning is thorough, timely and properly resourced (see Mendes, Johnson, & Moslehuddin, 2011; Stein, 2008, 2012).

However, the findings from Wave 1 of Beyond 18 suggested that best practice guidelines about transition planning were not always followed and that young people in OOHC were frequently not engaged in formal, structured planning about their future. Some of the inconsistency around transition planning appeared to be related to caseworkers' focus on meeting young people's most urgent needs - in particular, on finding transitional housing - rather than other important but less pressing forms of transition preparation.

Respondents to the Survey of Workers in OOHC indicated that gaps in the service network could hinder their ability to provide essential services to young people when they needed them. In particular, workers identified a range of barriers, including restrictive eligibility requirements and long waiting lists, to their ability to connect young people to leaving care and mental health services. Young people in Wave 1 of Beyond 18 also indicated that there could be issues with accessing, or even knowing about, appropriate services. Few had significant contact with leaving care services before leaving care and over a third of young people had been unable to access necessary services, especially mental health services, when in OOHC.

The education outcomes of young people in Wave 1 of Beyond 18 were often poor. At the time of Wave 1, more than half the young participants were still in school. However, only a quarter of those who had left school had completed Year 12 and a quarter had not completed Year 10. Young people in Wave 1 appeared to be relatively confident about their independent living skills and this was an area where carers and caseworkers indicated that they had been able to provide support. However, the findings on young people's emotional and interpersonal skills were less positive. Although most young people responded positively to questions about their sense of belonging, or of having someone in their life who cared about them, their response to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) suggested that many had significant emotional and peer relationship problems.

By the time of Wave 2 of the Survey of Young People, the majority of participants had left OOHC. Hence, the second Beyond 18 report focused on OOHC transition issues and outcomes (Purtell et al., 2019). On the whole, the study found that care leavers in Beyond 18 had poorer mental health, employment and education outcomes than other young people their age. They also reported high rates of self-harm, suicidality and financial stress. Many young people in the study described periods of housing instability that were associated with limited financial resources, inappropriate housing options and relationship breakdowns with parents, friends or partners.

Previous research by Stein (2005) and Johnson and colleagues (2010) has described distinct care leaver trajectories. Stein's influential work, for example, describes care leavers as tending to fall into one of three categories: those who have a relatively smooth transition and are 'moving on'; the 'survivors', who experience some challenges but whose outcomes can improve or decline according to circumstances (and the support they receive); and the 'strugglers', who experience a difficult transition often including homelessness, substance abuse and mental illness.

Analysis of the Wave 2 Beyond 18 survey data did not reveal such distinct trajectories or discrete groups; rather, life challenges appeared to be distributed across much of the study's population rather than clustering in a particular segment of the study population. A large proportion of the study population had experienced at least some major challenges or had indicators of poor social, emotional or financial wellbeing.

However, the qualitative interviews undertaken in Wave 1 and 2 did suggest that a small group of young people had experienced a relatively 'smooth' transition (Johnson et al., 2010) or were 'moving on' (Stein, 2005). This small group of young people described an early transition into safe and stable housing, positive social relationships and relatively good educational attainment. Although they did not constitute a statistically distinct group in the survey, their interview accounts suggested they were currently doing relatively well and, in most (but not all) instances, did so with the support of family or former foster, kinship or permanent carers.

The qualitative interviews also suggested that some young people had experienced multiple and interacting life challenges, such as homelessness combined with substance abuse and/or contact with the justice system. No clearly discernible factors were found to explain why this group appeared to be struggling more than others. Young people who had exited residential care did exhibit higher levels of financial and psychological distress than young people from foster care or kinship care but their employment and education outcomes were not noticeably worse than the rest of the study population.

1.2 Study limitations and sampling issues

As was noted in the previous Beyond 18 reports (see Muir & Hand, 2018; Purtell et al., 2019), Beyond 18 was a relatively small study with a small sample and this limited our ability to meaningfully explore the experiences of specific subgroups or to disentangle all of the characteristics associated with care leavers' outcomes. The latter, in particular, would require a much larger study with a much larger sample, to allow fine-grained analysis of care leaver histories and characteristics.

The lack of a sampling frame from which to identify and recruit participants, and the study's subsequent reliance on carers, care workers or youth and community sector organisation (CSO) workers to recruit young people into the study, also meant that the researchers were unable to control the composition of the study sample. This resulted in a sample in which certain groups were over-represented; in particular, female participants and young people who had been in residential care or foster care placement at the time of entering the survey or prior to leaving OOHC. Young people living in kinship care were significantly under-represented in the study while young people with a permanent care placement were also under-represented. See chapter 2 for an overview of participant characteristics and Appendix 1 for discussion of the analysis of CRIS data and the study sample's representativeness.

Because young people from kinship care and permanent care were so under-represented in the study, the focus of Beyond 18 was largely on young people in residential care and in foster care. As noted in previous reports, the over-sampling of young people from residential care allowed us to explore the needs of a group of care leavers who are often considered especially vulnerable. However, it also limited the study's ability to explore the experiences of young people from kinship care or permanent care and/or those who had less contact with services (and were thus less likely to be recruited into the study). The low numbers of young people from a kinship care placement meant that, in most of the analyses run for this study, the categories of kinship care and permanent care were collapsed into a larger 'home-based care' category that included foster care.

The high rate of attrition was also a challenge and potential limitation. As reported in the Wave 2 report (Purtell et al., 2019), 57% of participants dropped out of the study between Wave 1 and Wave 2. The attrition rate in Wave 3 was approximately 30%. High attrition rates were anticipated and are a common feature of research with vulnerable and highly mobile populations (see Johnson et al., 2010; Moore, McArthur, Roche, Death, & Tilbury, 2016). Nonetheless, high attrition presents a challenge because it reduces overall sample size and potentially introduces sample bias when continuing (or new) participants differ markedly from those who dropped out. In Beyond 18 there were few observable differences between continuing, new or lost participants (see chapter 2). However, it is possible that the young people who left Beyond 18 had characteristics that were invisible to the researchers but that made their experiences or outcomes significantly different from those young people still in the study.

It should also be noted that some of the young people in Beyond 18 left care several years before completing the Wave 3 survey. Hence, their experiences may not necessarily reflect those of young people leaving OOHC at the time of writing this report nor will they necessarily track the effects of recent policy reforms or program initiatives designed to improve leaving care.

1 Formerly the Department of Human Services (DHS).

This chapter outlines the demographic characteristics of care leavers who took part in the Wave 3 survey and the second and third wave of qualitative interviews.

2.1 Profile of young people in Beyond 18

Of the 126 care leavers who completed the third Beyond 18 Survey of Young People, 88 had completed one or more of the previous Beyond 18 surveys and 38 had entered the study for the first time (see Table 2.1). Sixty-one people completed all three Beyond 18 survey waves. An additional 10 people still in OOHC completed the Wave 3 Beyond 18 survey; however, the data from these surveys were not included in the analysis or this report because of the small number of such participants and the focus of this phase of the study on post-care outcomes.

The relatively high attrition rates from the Wave 1 and 2 surveys do not appear to have substantially altered the study population's demographic profile, with most demographic categories, or OHHC experience categories (such as placement type), remaining relatively unchanged. Because the study population had aged a year, the Wave 3 study population had a higher average age than in previous survey waves, although this was moderated to some extent by the younger average age of new participants (see Table 2.1). The split between metropolitan and regional representation in Wave 3 was also similar to that of previous waves, with half of all respondents living in metropolitan areas and slightly less than half in regional Victoria. The main difference from previous waves of the survey was the reduction in missing data about participant location.

New study participants were also broadly similar to continuing participants; however, new participants were slightly more likely to have been in a residential placement prior to leaving OHHC.

2.2 Qualitative interview participants

A total of 86 qualitative interviews were undertaken across the three waves of Beyond 18: 32 in Wave 1, 29 in Wave 2 and 25 in Wave 3. This report draws on data from both the Wave 2 and Wave 3 interviews.

The interview participant sample was drawn from the Survey of Young People and generally shared the demographic characteristics of the larger survey population, with an over-representation of female participants and care leavers who had been in foster care or residential care (see Table 2.2). There were three Aboriginal participants in the Wave 2 interviews and four in Wave 3. In Wave 2, 20 participants were living in metropolitan locations with eight in regional Victoria. For the Wave 3 interviews, a particular effort was made to interview young people in regional areas in order to explore their specific experiences. As a result, in the final round of interviews there were 14 participants living in regional Victoria and 12 in metropolitan areas.

| Characteristics | Continuing participants n(%) | New participants n(%) | Total Wave 3 n(%) | Total Wave 2 n(%) | Total Wave 1 n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 88(100) | 38(100) | 126(100)a | 126(100) | 202(100) |

| Age | |||||

| <18 | 2(2) | 1(3) | 3(2) | 39(31) | 93(46) |

| 18 | 22(25) | 20(53) | 42(33) | 36(29) | 53(26) |

| 19 | 23(26) | 9(24) | 32(25) | 25(20) | 38(19) |

| 20 | 20(23) | 4(11) | 24(19) | 18(14) | 0(0) |

| 20+ | 21(24) | 4(11) | 25(20) | 8(6) | 0(0) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 63(72) | 24(63) | 87(69) | 90(71) | 132(65) |

| Male | 24(27) | 11(29) | 25(28) | 35(28) | 66(33) |

| Other | 1(1) | 3(8) | 4(3) | 1(1) | 2(1) |

| Indigenous identity | |||||

| Not Indigenous | 77(88) | 32(84) | 111(89) | 111(88) | 170(84) |

| Indigenous | 10(11) | 4(11) | 14(11) | 14(11) | 24(12) |

| Prefer not to say | 1(1) | 2(5) | 3(2) | 1(1) | 8(4) |

| Location | |||||

| Major city | 42(48) | 21(55) | 63(50) | 61(48) | 85(42) |

| Regional | 41(47) | 16(42) | 57(45) | 46(37) | 73(36) |

| Other/unknown | 5(6) | 1(3) | 6(5) | 6(5) | 44(22) |

| Care placement type (most recent) | |||||

| Home-based care | 43(49) | 12(32) | 55(44) | 56(44) | 78(39) |

| Residential care | 32 (36) | 19(50) | 51(40) | 52(41) | 87(43) |

| Other/unknown | 25(28) | 7(18) | 32(25) | 18(14) | 37(18) |

Notes: Percentages may not total exactly 100% due to rounding and/or missing data. a The 10 survey respondents still in OOHC have been excluded from this table and all subsequent analyses.

| Kinship care | Permanent care | Foster care | Res. care/ lead tenant | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 2 | |||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 10 |

| Female | 2 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 19 |

| Total | 3 | 2 | 10 | 14 | 29 |

| Wave 3 | |||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| Female | 5 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 17 |

| Total | 6 | 2 | 8 | 9 | 25 |

Income and financial security are key life domains that can have a major influence on a range of other life experiences and outcomes. In this chapter, we explore Beyond 18 participants' incomes and employment outcomes and discuss changes in their financial situation since the previous Beyond 18 survey. This chapter also includes study participants' accounts of what it was like to look for work as a care leaver and their descriptions of what helped or hindered them in their quest for secure employment and financial security.

3.1 Income and employment outcomes

At the time of the Wave 3 survey, less than half (40%, n = 50) of all study participants were receiving income from employment. More than two thirds of Beyond 18 participants stated that they received some form of government benefit (see Table 3.1). Three young people reported that they had no income at all. Of the 50 participants who earnt some wage income, 38% (n = 19) were also in receipt of at least one form of government benefit. Youth allowance - a form of benefit available to those in education, training or seeking work - was the main source of government benefit for all care leavers: 44% of all care leavers received youth allowance and 22% (n = 11) of care leavers earning some income from employment also received this form of benefit. Disability payments were also important sources of income and received by a larger proportion of the study population (18%) than is received in the general population; for example, in 2015, less than 2% of Australians aged 15-24 received a disability support pension or payment (AIHW, 2015).

| Total n(%) | |

|---|---|

| Any government benefits | 86 |

| Government benefit types | |

| Youth Allowance | 53(62) |

| Rent Assistance | 22(26) |

| Parenting payments | 11(13) |

| Disability or Youth disability | 13(18) |

| Other government benefits | 13 |

Note: Columns and rows do not add up to 100% because participants could receive more than one type of benefit.

Of the 48 young people receiving income from employment (who also reported their working hours), the majority worked part-time and nearly half 42% (n = 20) worked less than 20 hours per week. A similar proportion of participants (42%, n = 20) worked full-time or close to full-time hours (usually defined as 35 hours per week). The generally low number of young people in employment, and the relatively high proportion working part-time, is broadly consistent with wider community norms.

Young people in the general population are more likely than older adults to not be employed or to be in casual or part-time employment than older adults, in part because they are more likely to be in school or undertaking further education or training (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2017). Indeed, 43% (n = 12) of all part-time workers in the study were also undertaking some form of study, although the majority (73%, n = 22) of those in part-time work also expressed a desire for increased working hours, which can be an indicator of underemployment.

The analysis of participant data on income and employment also revealed that approximately half of the study population were not in employment, education or training (NEET). This was a considerably higher proportion of NEET youth than in the general Australian youth population. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD; 2018), for example, lists the proportion of NEET 15-19 year olds as 5% (in 2016) and the proportion of NEET 20-24 year olds at around 12%. This form of non-participation in education or employment has been linked to future unemployment, low incomes and subsequent social and economic disadvantage and exclusion (Pech, McNevin, & Nelms, 2009).

Further, this group of Beyond 18 participants also showed signs of having a wider range of poor outcomes across other life domains, such as housing, life satisfaction and mental health, than participants who were working and/or studying. Although this group had only slightly higher levels of financial stress than the study population as a whole (see section 3.2), the wider range of general life challenges that they faced indicated ongoing vulnerability. We will come back to this group of young people in the chapters that follow.

The predominance of part-time work and/or reliance on government benefits also had an effect on care leavers' incomes, with more than 70% of participants reporting that they earned significantly less than the poverty level for a single, non-working adult.2 See Table 3.2 for care leaver incomes.

| Income per fortnight | n = 113 |

|---|---|

| Overall income | |

| Care leaver - mean income | $758 |

| Care leaver - median income | $550 |

| Care leavers earning < $832 (the Henderson poverty line) | 80(71%) |

| Care leaver income by work status | |

| Part-time employed - mean income | $860 |

| Part-time employed - median income | $800 |

| Full-time employed - mean income | $1,401 |

| Full-time employed - median income | $1,200 |

| Not working - median income | $460 |

| Not working - mean income | $540 |

3.2 Financial stress

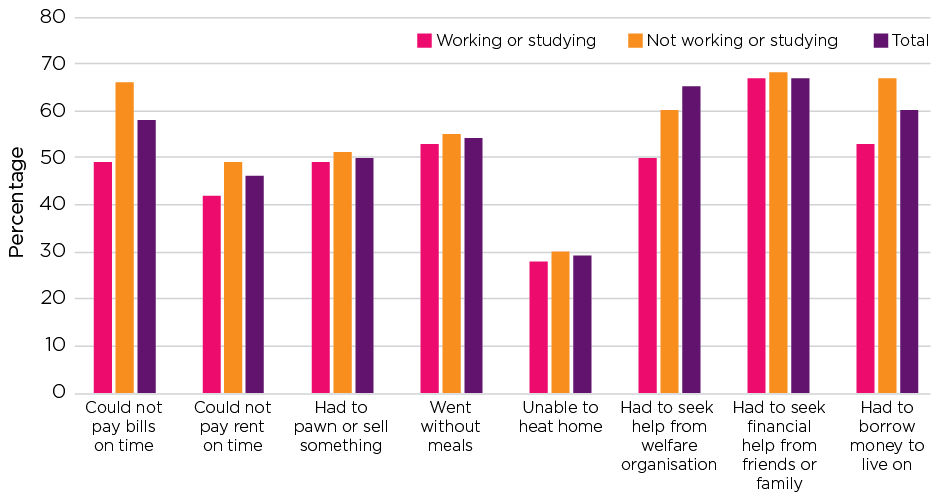

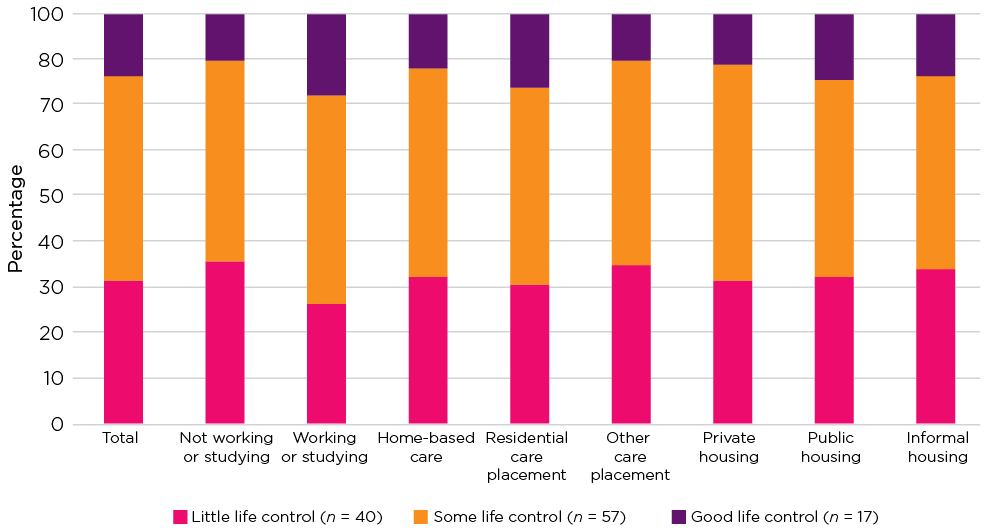

Care leavers' low incomes were associated with high levels of financial stress. In Wave 3, indicators of financial stress were evident across the study cohort, with 84% (n = 98) of participants reporting at least one indicator of financial stress and 57% (n = 67) reporting four or more indicators. Financial stress was distributed across the study population and so there was little meaningful difference between subgroups within the cohort; for example, financial stress did not vary significantly according to placement type. Although young people who were not in employment or education reported slightly higher levels of stress on most indicators than the rest of the study population, the differences were not statistically significant. See Figure 3.1 for a breakdown of financial stress indicators.

Because financial stress measures tend to focus on households, there is a lack of publicly available data for this age group in the general Australian population. This makes it difficult to compare Beyond 18 participants' levels of financial stress with those of other young people. However, participant reports of financial stress experiences were very high when compared to low income households in the general population. For example, 58% (n = 61) of care leavers reported that they were unable to pay their bills and 54% (n = 62) reported going without a meal. In comparison, only 14% of the lowest household income quintile - in the ABS (2016) household expenditure survey - reported that they were unable to pay their bills on time and 6% went without meals.3 Further, only 17% (n = 19) of all Beyond 18 respondents reported that they would be able to raise $1,000 in a week in an emergency; in contrast, 73% of households in the lowest household income quintile reported that they could raise $2,000 in a week if required.

Figure 3.1: Indicators of financial stress in previous 12 months, by work/study status

Although the focus of the ABS survey is on households rather than individuals and means that these statistics are not directly comparable, the Beyond 18 findings suggest that rates of financial hardship among young people in Beyond 18 are very high. Furthermore, participants in the qualitative interviews described ongoing financial stress and financial insecurity as a common feature of post-care life and as a significant negative influence on housing security (see chapter 4) and participation in education (see chapter 5).

3.3 Barriers and enablers for achieving employment and/or financial security

The qualitative interviews provided further insights into care leavers' experiences of employment and job searching. Interview participants described a number of barriers and enablers to their ability to achieve either employment or financial security.

The majority of care leavers expressed a strong desire to be employed or to stay in work and many aspired to work in youth or social services. Of the care leavers who were working at the time of Wave 3, most reported that they had found employment through relatively conventional means such as online searches, leaving their résumés at businesses and drawing on their networks of relatives and friends. In common with other young people in the general population, care leavers who were studying tended to work part-time, most often in hospitality, because these jobs were relatively easy to obtain and fit well with the requirements of their study.

However, many care leavers had struggled to find even part-time work and they described a range of barriers to job seeking (or to keeping a job) such as low educational attainment, lack of stable housing, struggles to meet the cost of travel to work or to job service offices, health issues (including mental illness) and disability. A small number of care leavers with health issues suggested that they were dissuaded from even seeking work by the fear that, even if they found a job, their health issues would make the work too difficult, or their employers would not understand their needs, and they would lose their job. Previous in-care experiences, such as placement instability or the time restrictions associated with being in residential care, were also described as hindering young people's ability to accumulate valuable work experience.

I came home one day from just being out on a weekend just seeing a friend … and they said get your stuff out of the house. I was like, 'You guys are joking, right? I've got school, I've got two jobs right next to this place.' (Residential care leaver, male, 18, Wave 2)

An especially prominent theme in care leaver accounts was the absence of social or family resources. In particular, care leavers described their awareness that, unlike many young people in the general population, they did not have family members or extended social networks that they could ask for job search advice, who could provide them with references or who could use their personal networks to find them a job. As a result, what support they did have came from Centrelink-associated job services and Disability Employment Service (DES) providers.

Although such services could be helpful, care leavers who gained employment through these services often did so in roles that were subsidised by the job service for a fixed period. This meant that the job could end when the subsidy stopped. Care leavers subsequently described anxiety about the stability of such work and the possible need to seek work again in a few months. Care leavers also reported that dealing with mainstream job services could be challenging. In particular, mainstream job search agencies were described as lacking empathy or understanding of care leavers' need for additional support or of their physical and mental health needs.

I was with another employment, you know, job search provider, whatever they're called. But I really didn't find it helpful. Like, it didn't matter what my circumstances were … you'd sort of get the bare minimum help from them. (Foster care leaver, female, 22, Wave 3)

In contrast, specialist services such as DES or targeted care leaver supports such as the Victorian government's Springboard program were potentially important sources of support.4 For example, one kinship care leaver described how her participation in Springboard had helped her to find full-time employment in a workplace that could also further her aspiration to become a youth justice worker. For this participant, the most important enabler to her finding work was the emotional and practical support and encouragement provided by her Springboard caseworker. It was this relationship that had enabled her to get away from 'the wrong crowd' and realise her potential.

She was very, very supportive. Like she kind of expected things of me that I've never really thought people would expect out of me, and it made me wake up a little bit, like it made me realise I can do things … And she, because I told her what I wanted to do, I got two job interviews to corporate receptionist and they gave me the job straight away, so I was happy. And ever since I got my job, my life's been pretty much on track. (Kinship care leaver, female, 19, Wave 3)

More generally, the quality of social relationships was described as key to young people's experiences of seeking, finding and losing work. Social relationships can be an important part of many people's experiences of work but, as has been described in previous Beyond 18 reports, many care leavers had complex or challenging relationships with peers and/or authority figures and many also longed for more secure or close relationships. Consequently, the social side of work could assume particular importance and have a strong influence on whether care leavers enjoyed, and thus stayed, in work. When participants were happy in their employment, they often spoke about liking their workmates or getting along well with their bosses or customers. Finding a positive and supportive work environment was an important enabler for staying in a job and developing a strong work history.

It's just you know, I get up and I enjoy coming to work … like, I don't mind spending my day doing the boring stuff, surrounded by people that are pretty great. So yeah, it just makes it enjoyable, good environment … like coming from such a big workplace like [national supermarket chain], and where I am now, it's just a little family business. So, it's kind of, the environment's different, it's a lot more cosy, which I like … And they're a lot more understanding, like if you've got personal stuff or whatever, they understand. (Foster care leaver, female, 20, Wave 3)

In contrast, many care leavers described conflict at work or a lack of employer understanding of their specific circumstances or needs for additional support. This could then lead to care leavers frequently changing jobs or leaving employment altogether.

Employers aren't the most sympathetic to that stuff … and with my IBS [irritable bowel syndrome] being stress related, it worries me about when I'm working, getting stressed out and then it stresses me out more thinking about if it will happen and I'll have to take time off. It ends up making it worse. And yeah, there's no real help from employers in those situations. (Kinship care leaver, male, 21, Wave 3)

3.4 Discussion

The approximately 12-month interval between Wave 2 and Wave 3 of Beyond 18 saw relatively little change in the study population's levels of employment or their levels of financial stress. In both waves, less than half the population was in any kind of employment, and reliance on government benefits was high. The number of care leavers reporting experiences of financial stress also stayed high. Income levels were not measured in Wave 2 but the questions about income in Wave 3 suggested that most of the study population was on a low or very low income. More positively, the number of care leavers in full-time, or close to full-time, employment increased from only six people in Wave 2 to 20 in Wave 3.

It can be difficult to interpret statistics on youth incomes, employment levels and work hours. Young adults, in general, often undertake a complex range of work and study arrangements in which studies may be combined with part-time or casual work. Other full-time students may not work at all and not be actively looking for work. Subsequently, young people tend to work fewer hours than older adults, when they work at all, and have lower incomes.

Because young people tend to have less work experience than older adults, they are also more likely to be unemployed or to work in lower-paid part-time, casual or entry-level roles. Youth unemployment figures for the general population are often high relative to that of the total adult population. For example, in 2017, the average Australian youth unemployment figure of 13% was more than double the overall unemployment rate (ABS, 2017). This complicates comparisons between Beyond 18 participant outcomes and those of the general population.

However, the large proportion of Beyond 18 participants who were NEET suggests that financial insecurity is an even more pressing issue for many care leavers than it is for the general youth population. Further, it is worth noting that although many young people in the general population have relatively low incomes, they also commonly receive financial support (including a place to live) from their family. The assumption that young people will receive family support and/or have fewer needs than older adults is reflected in the lower rates of youth wages and Youth Allowance benefits.

However, care leavers do not always have reliable family support with which they can supplement their low incomes. As a result, unemployment or a low income can have serious consequences for their ability to maintain secure and stable housing, to engage in further education or to maintain their physical or mental health. As was evident in some care leavers' accounts of job searching, the lack of support from family or extended social networks could also hinder their ability to find employment and achieve greater financial stability.

2 For a single, non-working adult, as of September 2017 (two months after the Wave 3 survey of young people opened), the poverty level was $832.14 per fortnight (Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, 2017).

3 The ABS household expenditure survey uses indicators of both 'financial stress experiences' and 'missing out experiences' such as being unable to afford holidays or a night out, to measure overall financial stress. However, other surveys such as HILDA and Beyond 18 use only 'financial stress experiences'. The 'missing out experiences' indicator of financial stress was not used in the Beyond 18 study due its limited relevance to the lives of care leavers and to reduce participant burden.

4 Springboard is a Victorian government program that provides medium- to long-term intensive case management support for young people after leaving OOHC and helps care leavers access funding for education and training.

In this chapter, we examine care leavers' housing situations after leaving care. We also explore care leavers' accounts of finding and keeping post-care accommodation and their thoughts on what most helped or hindered their quest to find safe and secure accommodation.

4.1 Types of accommodation and post-care housing mobility

In Wave 3 of Beyond 18, almost equal numbers of young people lived in private housing (defined here as private rentals and home ownership) and in 'informal' arrangements (i.e. living in a non-contractual arrangement with friends, family or former carers). A slightly smaller group lived in transitional or public housing (here grouped together as 'supported housing'). See Table 4.1 for a breakdown of care leaver housing types.

Care leavers who had previously lived in residential care were notably more likely to live in some form of transitional or public housing than young people who had exited other care types. Young people who had exited home-based care were the most likely to live in 'informal housing'. In part, these differences reflected the different kinds of supports available to those leaving different OOHC placements. That is, young people from residential care were less likely than young people from home-based placements to have former carers they could live with.

Housing type was not in itself an indicator of housing suitability or better or worse housing outcomes. Nonetheless, living in supported housing was associated with low incomes and 44% (n = 26) of care leavers who were NEET lived in this form of accommodation. In contrast, only 13% (n = 8) of care leavers who were working or studying lived in supported housing; nearly half of this group (49%, n = 30) lived in informal arrangements with partners or former carers or partners.

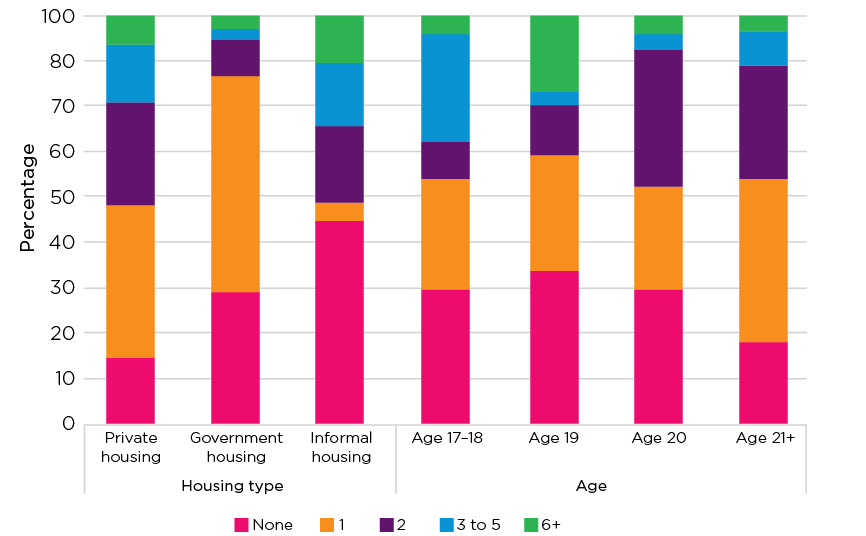

Consistent with previous research on care leavers (e.g. see Johnson et al., 2010; Moslehuddin, 2011), the care leavers in Beyond 18 reported relatively high rates of housing mobility. In Wave 3, more than a third (39%, n = 49) had moved house at least twice in the previous 12 months and 21% (n = 26) had moved three times or more (see Figure 4.1). Individual housing moves can be explained by a range of factors, both positive and negative, but frequent moves in a relatively short time period can be an indicator of housing instability; this, in turn, can be an indicator of relationship breakdowns, financial insecurity or inappropriate housing options. Care leavers' accounts of why they had moved house in the last year suggested that all of these were factors - in particular, conflict with family, friends or housemates - were commonly cited as prompting a change of accommodation.

Housing instability was a potential source of financial stress and care leavers described how they could struggle to pay moving costs, utility reconnection fees and housing bonds. Housing instability could also affect care leavers' access to services, education or employment. The difficulties that unstable housing could have on all aspects of life were evident in the account of one residential care leaver who was formally homeless at the time of Wave 3. This young man described how his lack of stable housing, and inability to find housing in a suitable location, had made it difficult for him to stay in work.

I was working but without stable housing that makes it a little bit complicated ... It makes it very hard. I had to travel five hours day for a 9 to 5 shift, Monday till Friday for about five months at [supermarket], and I couldn't find stable housing because of the instabilities in my life. (Residential care leaver, male, 21, Wave 2)

| Private housing n(%) | Supported housing n(%) | Informal housing n(%) | Total n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 43(36) | 34(28) | 44(36) | 121 |

| Age | ||||

| 17-18 | 11(26) | 17(40) | 14(33) | 42 |

| 19 | 10(32) | 7(23) | 14(45) | 31 |

| 20 | 11(46) | 4(17) | 9(38) | 24 |

| 21+ | 11(46) | 6(25) | 7(29) | 24 |

| Last care placement type | ||||

| In-home care | 18(33) | 8(15) | 27(49) | 55 |

| Residential care | 18(35) | 23(45) | 9(18) | 51 |

| Other/unknown | 7(35) | 3(15) | 10(40) | 20 |

| Location - remoteness (excludes missing n = 115) | ||||

| Major city | 16(26) | 20(32) | 26(42) | 62 |

| Regional | 24(45) | 13(25) | 16(30) | 53 |

Note: Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

No specific group of care leavers was significantly more mobile than the study population as a whole. Age did appear to be a possible factor in housing stability, with participants aged 18 or under moving slightly more frequently than older participants but the differences were slight and not statistically significant (see Figure 4.1). There were more noticeable differences in patterns of mobility between the groupings of care leavers living in different types of housing but there was also a great deal of variation within these groups.

Supported housing proved to be a relatively stable form of accommodation: few care leavers in supported housing had moved more than once in the year preceding the survey. Interviews with care leavers in transitional or public housing suggested that at least some had secured long-term (up to two-year) lease agreements in specialist housing for young people at risk of homelessness and this had resulted in increased housing stability. However, it is also likely that some of the stability in supported housing was the result of care leavers' low incomes, or other life issues such as mental health, preventing them from securing a property in the private rental market and moving on from supported housing.

Young people living in private rental accommodation and informal housing arrangements had more variable patterns of housing mobility. Half (n = 22) of the care leavers living in informal arrangements had not moved at all in the previous 12 months; however, 27% (n = 12) had moved three times or more. Data from all three waves of Beyond 18 interviews suggested that this variability was in part related to the varying quality of care leavers' personal relationships.

Stability, for example, could be associated with strong bonds with kinship carers, former foster carers or partners. Some care leavers from foster care placements, for example, indicated that their relationships with their former carers resembled those of biological 'family' and that they had expectations of ongoing support and accommodation. Other care leavers, however, did not have such close relationships or described conflict and relationship breakdowns that led to them having to move out (including moving out into homelessness). Even when relationships with carers were ongoing and perceived to be positive, some care leavers indicated that they could not rely on unlimited support or hope to stay with carers in the longer term.

You know, to be looked after by family you know, it doesn't really work that way when you're a foster kid. So, you're sort of on your own for the most part you know, if you're really lucky you might have a bit of support from your foster family. But you know, most of the time you've really got to try and get things for yourself. (Foster care leaver, female, 22, Wave 3)

Figure 4.1: Housing moves in last 12 months by housing type and age

4.2 Barriers and enablers: finding and keeping safe and stable housing

Housing, and housing stability, has been a prominent topic in all waves of Beyond 18 data collection. In the Wave 2 and 3 interviews, care leavers again described complex post-OOHC housing trajectories, with multiple moves between different places, and different types of housing, prompted by conflict, lack of money or lack of suitable housing options. Care leavers also described several routes to housing stability and, conversely, several reasons why that could be difficult to achieve.

For some young people, stable housing could be achieved through supported housing, particularly when this housing was available in the medium to longer term. For example, Youth Foyers - a form of supported housing available to young people intending to work or study - could offer care leavers 24-month housing agreements, a longer period than is customary for private rental agreements. For some care leavers, this stability, and the relative freedom from anxiety it could offer, was important because it allowed them to focus on other parts of their lives and/or to learn to live independently.

I think living in those sort of housing things that I lived in, it's really good … I guess transition might be the best way to put it because it's good for giving yourself a bit of time to get your stuff sorted … I needed that two years to get my stuff together and learn how to be independent and learn how to do it on my own ... think it's good, like, for people to have that sort of break … going from where you don't have to do anything … you don't have any responsibilities, you just do what you want to do and you know there'll be a meal, and there'll be a made bed and sort of those sort of things. To then go straight into private rental, that would be like a total big shock and I don't think, I think that's where a lot of young people struggle. (Residential care leaver, female, 19, Wave 3)

Some forms of supported housing could also allow care leavers to live alone while in a relatively supported environment in which help was available. This was important for those who wanted greater independence or to avoid potentially difficult social relationships.

For many care leavers, however, stable housing was most closely associated with stable relationships. As noted above, some care leavers were able to stay on with former carers after the end of their formal order. This could mean additional financial strain for former carers, as not all were able to get support after the end of a child protection order. However, some care leavers and/or their former carers were able to source financial support from elsewhere and this could help foster carers provide extended post-transition support. For example, one young man who had been in permanent care described how his carers had secured funding from a non-government organisation to install a unit in their backyard for him to live in. This, he believed, would give him the stability he needed to pursue his education.

I think it'll be a lot better for my studies, yeah, a lot quieter place. It'll give me a bit more of an experience with managing my own area … otherwise I think for my family it'll be really good because everyone else in the family will benefit from the extra space. Less petty arguments and stuff like that. (Permanent care leaver, male, 18, Wave 2)

However, not all care leavers had the option of staying with former carers, while others wanted to assert their independence by moving out. Although some young people found relative stability by moving in with a partner, others were challenged by the move into private rental accommodation or into informal arrangements with friends or the family of partners. Care leavers without supported housing could rarely afford to live alone. However, young people's complex social relationships, and the high prevalence of emotional issues or mental illness (see chapter 6), meant that many young people found living with other people, including friends, partners or partner's families, to be challenging. Previous negative experiences of group living and peer relationships, especially for care leavers from residential care, and issues with mental health meant that some care leavers experienced anxiety at the prospect of moving in with strangers.

I get really anxious meeting new people, so I think moving into a house full of new people would be really stressful. (Foster care leaver, female, 19, Wave 3)

Even when living with friends, or with the family of partners, many care leavers described ongoing tensions or social conflict that led to relationship breakdowns and subsequent housing instability.

[The] joys of living with friends is, [there] tends to be a falling out when you start living with them or you know, difficult situations. So, that's kind of where they broke down. (Foster care leaver, female, 20, Wave 3)

The end of partner relationships could also lead to housing instability, particularly because, in many cases, the remaining partner could not afford to pay rent when the other left.

I spent the entire month applying for like four or five houses a day, and never got anywhere. It was either move in with family or have nowhere to go ... I feel like I'm a burden … because all their kids have grown up and left home and are having kids of their own and now I'm there. (Foster care leaver, female, 19, Wave 3)

Even when care leavers had achieved relatively stable housing, they could still worry about their ability to afford or maintain their housing in the longer term. One care leaver, who had moved into a private rental - following a long search - with her partner, described her anxiety about keeping their house clean and paying bills on time, and contrasted this with her partner's relative unconcern. She attributed this difference to her awareness that she had no-one to rely on, whereas her partner, who had not been in OOHC, had never experienced the same instability.

I'm always, you know, had a sense of having to pay money and knowing how important it is to keep a roof over your head and how hard it is when you don't have that and how to get it. And so, for me it's just an absolute priority that my partner who's always, up until his mid 20s when he moved in with me, he's always had it all paid for him … so I don't think he always understands … how hard it can be not having a roof over your head. (Foster care leaver, female, 22, Wave 3)

For at least one care leaver, it was the experience of instability in OOHC that had ultimately led to his post-care struggles to find stable housing; for this young man, instability had been a constant feature of his life.

I've never stayed in the one place for longer than six weeks. I mean three months has been the longest I've probably ever stayed in, like, a refuge. And that was it. (Residential care leaver, male, 22, Wave 3)

4.3 Discussion

Australian and international research and practice literature has consistently highlighted care leavers' high risk of becoming homeless or subject to ongoing housing instability. Care leavers' struggles with finding housing are due to their common lack of family supports or supportive social networks, limited financial resources and high rates of mental illness and/or behavioural issues related to past trauma (Dworsky, Napolitano, & Courtney, 2013; Flatau, Thielking, MacKenzie, & Steen, 2015; Mendes et al., 2011). These factors are exacerbated by a commonly reported lack of secure, long-term and well-maintained public housing (Forbes, Inder, & Raman, 2006; Johnson et al., 2010; Stein, 2012). The previous Beyond 18 report was largely consistent with this research and described how many care leavers had complex housing trajectories and high rates of mobility in the first 1-2 years after leaving care (Purtell et al., 2019).

Wave 3 of Beyond 18 saw relatively little change to participants' housing patterns. A relatively large proportion of care leavers lived in transitional or public housing and many of these young people were not engaged in employment or education. Nor were care leavers, as a whole, notably more stable than they had been in Wave 2.

Previous research on care leaver housing trajectories suggests that housing instability is often highest in the first 12-24 months after transition, before becoming relatively more stable over time (Mendes et al., 2011). However, this relative increase in stability was not evident for all participants in Beyond 18. Rather, there was a great deal of variability within the sample, with some care leavers finding relative stability, particularly those in supported housing or living with former carers, while others continued to experience considerable volatility. Several participants in the qualitative interviews also described how they had continued to bounce between houses and housing types. Some of the movement was the result of care leaver's low incomes and subsequent inability to afford rent or to access appropriate housing. However, general life instability and challenging social relationships also emerged as a barrier to stable housing.

Although some care leavers had been able to find stability with former carers, partners or the family of partners, others struggled with maintaining stable social relationships with their family, partners or housemates and this often led to them moving from one place to another as social relationships ruptured. In some cases, these relationships were repaired, and the care leavers was able to move back in with friends, partners or former carers, but these relationships were still frequently fragile and prone to breakdown and further housing instability. This ongoing housing insecurity could make it difficult for young people to advance in other areas of their lives; in particular, insecure or unstable housing could make it difficult to find or maintain paid employment or to engage with education (see chapter 5).

This chapter describes care leavers' educational attainments and explores changes since the Wave 1 and 2 Beyond 18 surveys. The chapter also looks at the numbers of care leavers who have gone on to further education, shares some of their experiences of education and describes some of what care leavers said about why they had or had not engaged in education.

5.1 Formal education outcomes

Care leavers in Beyond 18 had generally lower than average school attainment levels. At the time of Wave 3, just over a quarter of school leavers had completed Year 12 (either at school or in a post-school qualification such as VCAL or VET; see Table 5.1). This school completion rate is very low relative to the general Victorian Year 12 completion rate of 77% (see Lamb, Jackson, Walstab, & Huo, 2015). It also showed little change from previous waves of Beyond 18, which had seen similarly low rates of school completion.

In Wave 3, around 10% of care leavers also indicated that they had left school before completing Year 10. This represented a slight improvement on the 26% of school leavers who had not completed Year 10 at the time of the previous Wave 2 Beyond 18 survey (see Purtell et al., 2019). This change was partially explained by a small number of former study participants, who had especially low levels of educational attainment, dropping out of the study before Wave 3 but was also affected by some study participants returning to education (and gaining a Year 10 equivalent qualification). Regardless of the slight improvement in Year 10 completions since previous surveys, the Wave 3 results still indicate that at least some care leavers had failed to meet the Victorian government's requirement that all young people complete Year 10.

Although study participants on the whole had poorer than average levels of school attainment, nearly half of the study population (53%, n = 66) had undertaken at least some form of further education and 27% (n = 34) were currently studying. Certificate III or IV courses at a TAFE college were the most common (47%, n = 31) forms of further education undertaken. This replicated the results of the previous Beyond 18 surveys. The number of young people in the study who were attending university was small (n = 8; 6% of the total study population and 8% of known school leavers) but represented a slight increase on the five participants in university at the time of Wave 2.

Analysis of the survey data did not reveal any association between observable participant characteristics and either educational attainment at school or subsequent re-engagement with education. Nor was there a strong association between participants' level of educational attainment (i.e. their highest completed educational qualification) and their employment outcomes. This lack of correspondence was partially due to the generally low employment levels in the study population as a whole but was also influenced by some care leavers not having yet entered the labour market (because they were still studying).

However, there was some association between employment and undertaking study towards a post-school qualification (which was not necessarily completed by the time of Wave 3). Around half of the young people in full-time work (55%, n = 11), and a similar proportion of those in part-time work (50%, n = 28), were either currently studying or had competed a course of further education.

In contrast, a substantial proportion of study participants (54% of all school leavers, n = 42) were not engaged in either employment or education (also see chapter 3). This lack of engagement means that this group was at greater risk of longer-term unemployment or the inability to enter the labour force. As we describe in the chapters that follow, this group also had generally poor psychological wellbeing and/or levels of mental illness.

| Continuing n(%) | New n(%) | Total n(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed school to Year 12 | 23(26) | 12(32) | 35(28) |

| Completed school to Year 10 | 38(43) | 14(37) | 52(41) |

| Left school before Year 10 | 7(8) | 6(16) | 13(10) |

| Still in school | 9(10) | 5(13) | 14(11) |

| Prefer not to say | 11(13) | 1(3) | 12(10) |

| Total | 88 | 38 | 126 |

Note: Completion rates include qualifications completed outside of secondary school (e.g. at TAFE)

5.2 Barriers and enablers: engaging with education

For most young people (including those in the general population) completing high school, undertaking an apprenticeship or traineeship or continuing in further or higher education are essential pathways to good employment prospects and future wellbeing. The qualitative data made it clear that many of the participants in Beyond 18 were clearly aware of the value of further education, or of completing their previously unfinished education, and they commonly indicated a desire to gain useable qualifications.

Like their peers in the general population, study participants were motivated by a range of reasons for wanting to study beyond high school. Some expressed an interest in a particular career type and/or a desire to 'make a difference'. For example, many care leavers wanted to work in the youth or community sector and had undertaken certificate level courses to further this ambition. Others were motivated by the perceived higher income, status and stability that further education would bring. Finally, for many, especially those undertaking certificate and diploma level qualifications, engagement with education (or a desire to undertake further education) was strongly driven by the desire to escape unemployment.

Although many care leavers were able to articulate their aspirations for further education, and many had undertaken study, neither the Beyond 18 survey data nor the qualitative interviews revealed many definite enablers for engaging with school or further education, or personal characteristics associated with educational success. Care leavers' descriptions of educational 'success' tended to focus on how they had to carefully manage the many barriers to their education so that they could 'push through' and move to a new phase in their lives.

However, there were some accounts of useful supports that had enabled care leavers to complete or further their education. For example, a handful of care leavers had experience of alternative education settings and, on the whole, they felt that such schools were better able to provide a more supportive, welcoming and understanding environment than mainstream schools.

There was a one-on-one teacher instead of one teacher with heaps of other kids so you didn't feel the pressure was on you and there was no reason to get hot-headed, like, they understood when you were getting hot-headed. (Residential care leaver, female, 19, Wave 2)

More generally, care leavers in the qualitative interviews also spoke of the importance of life stability as an enabler of education; in particular, having somewhere safe and affordable to live - most often with family, carers or partners but also in supported housing - and having access to social and financial support. Programs such as Springboard were also described as providing some assistance to successfully completing education. Springboard caseworkers, in particular, were seen by many care leavers as positive supports whose help and encouragement could help young people enter or stay in education and foster self-belief.

More often, however, care leavers focused on the barriers to engaging with and completing their education. Consistent in these accounts were the difficulties faced while still at school and how these early experiences had affected care leavers' ability to complete school, find work or re-enter education. An especially common theme in these accounts was the difficulty of managing school when experiencing placement instability or just generally complex home lives (both in and out of care).

I wasn't the fastest kid because I wasn't thinking about school work. It wasn't my priority. Obviously, I wanted to be good and I wanted to be smart. I didn't want to be seen as the dumb kid or the slow kid or the naughty kid because I wasn't paying attention. But it wasn't because I was naughty, I just had more important things to think about. Like what are my sisters going to eat, is Mum going to be ok when I get home, is she going to be drunk, am I going to get to sleep on time tonight or am I going to be doing homework until late. Am I even going to be able to do my homework? I can barely read. And that was basically all through primary school. (Foster care leaver, female, 20, Wave 3)

When [life] goes wrong it's just … school's just another thing to stress about. (Residential care leaver, female, 18, Wave 2)

Even those young people who had been academically successful could report struggles juggling their school life, home life and other life anxieties. In particular, care leavers spoke of their anxiety about leaving care, and how this had interfered with their study and made it hard to focus. For the relatively small number of study participants who stayed in school until Year 12, preparation for final exams could coincide with the transition from care. This could lead to feelings of anxiety about the future that negatively affected young people's ability to focus.

Other recurring themes in care leaver accounts were feelings of shame and embarrassment related to being in care, experiences of bullying - especially when young people's care status was known by their peers - and the low educational expectations of carers, other students and school staff. Because so many young people had complex life issues, some felt that teachers and the mainstream schooling system were ill-equipped to cope with their high needs.

If anything, people are constantly, there's the feeling that everyone expects you to fail … You just see it all the time, even just how kids will react when they find out you're in foster care. Like it's just, you're almost pitied or something and then of course there is a lot of abuse and what not … And I feel like that's the sort of thing that holds people back from succeeding. (Permanent care leaver, male, 20, Wave 3)

I finished high school. I was living with someone quite abusive at the time so it was a bit difficult because I had to go home and deal with her most of the time … they [the school] were understanding, somewhat, but I don't feel like they were very accommodating towards my situation … teachers in general were sort of swamped by the system themselves, just the entire education system wasn't accommodating and couldn't give me the leeway in terms of my situation and it was quite disheartening. (Kinship care leaver, female, 21, Wave 3)

Problems at school could ultimately have a cumulative effect that made later re-engagement more difficult, especially if the young person had been excluded from school or had ongoing peer issues.

When I was in school I was just struggling because I was a really angry kid, like, and the way I would outburst was always angry, like, so if anything would frustrate or upset me or anything like that I was angry and it was the reason why I was kind of kicked out of school. (Kinship care leaver, female, 18, Wave 3)

Being in residential care and having carers and stuff, like we couldn't always guarantee that I would be at school on time and stuff, so that's why they didn't want to accept me [back at participant's previous school]. And then I think mainly after that the reason why I didn't want to go and give another school a go was just … there was people there that I knew. (Residential care leaver, male, 20, Wave 2)

In addition to their past negative experiences of school, care leavers also outlined some barriers to entering further education, many of which related to the challenges of living independently after leaving OOHC. Even when young people harboured desires for re-entering education, life challenges concerning housing instability, disability, mental health issues and financial insecurity could take priority or even hinder their ability to think about starting education or training.

So maybe some time, when the time's right and I've settled into the job and I'm feeling better health wise, I might look into doing some more study … My main focus has been getting a job and getting myself well enough physically to be able to cope with a job so that I can support myself better first. It's really no good getting into a course and you haven't got enough money when you come to pay the rent or pay the bills and things like that and to support doing the course. So yeah, it's always been my main priority to get a job first so that it doesn't matter what happens, I've at least got an income coming in that I can support myself and, you know, find housing easier and things like that. (Foster care leaver, female, 22, Wave 3)

The financial barriers to completing, continuing or re-engaging in education were especially prominent in care leaver accounts. Training-related fees, the cost of materials, transport costs and the cost of forgoing employment in order to undertake education could dissuade care leavers from further study or make their study life difficult. Transport, for example, was described as essential for education pathways but several care leavers reported that they could not afford the hours of driving practice needed to obtain a driving license or the high registration and insurance costs for drivers under 25.

These education-related expenses could create or exacerbate financial stress. Although some care leavers tried to manage such costs by getting more shifts or taking on additional part-time work, this could also make study difficult and/or create additional life stress. Trying to manage all of their work and study commitments and financial concerns caused a great deal of stress and anxiety, which could exacerbate existing health conditions.

I'm juggling three casual jobs at the moment and still kind of struggling to pay for everything. And with a full-time study load. (Kinship care leaver, Female, 20, Wave 3)

Assistance with meeting education or training costs (e.g. via post-care support payments) was thus potentially valuable and could increase care leavers' ability to engage with education. For example, one foster care leaver undertaking an apprenticeship described how leaving care services had helped him with the cost of tools and this had been an essential form of support. However, not all study participants knew of such supports or how they could access them.

5.3 Discussion

Australian and international research has pointed to the educational deficits that children and young people often bring into OOHC and how these can be exacerbated by their care experiences. Harvey, McNamara, and Andrewartha (2016), for example, have observed that many young people entering OOHC have experiences or demographic characteristics associated with low levels of educational attainment, such as biological parents with a low socio-economic status or low levels of education, an Indigenous identity and being located in a regional area. These pre-existing factors are often combined with, or compounded by, experiences of trauma or neglect, disability, mental illness, placement instability, housing instability, social or familial conflict and peer cultures within OOHC that disparage the value of education (Cashmore, Paxman, & Townsend, 2007; Hart, Borlagdan, & Mallett, 2017). As a result, care leavers commonly have lower levels of educational attainment than their peers in the general population (see Cashmore et al., 2007; Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; McDowall, 2016). This cannot only affect their ability to find stable employment but can also be associated with future poor mental and physical health, low levels of socio-economic wellbeing and reduced resilience (Rutter, Giller, & Hagell, 1998).

All three waves of Beyond 18 have echoed these research findings. School attainment within the study population has remained poor and there is limited evidence of significant improvement over time. Although some young people in Wave 2 had indicated that they were undertaking further education in order to complete Year 12, this did not translate into a notably increased number of Year 12 completions by the time of Wave 3. The number of study participants who left school without completing Year 10 also remained worryingly high in all three waves of Beyond 18, although Wave 3 did see a slight rise in the number (and proportion) of participants who had at least attained this level of achievement.

Also consistent with previous research were Beyond 18 participants' descriptions of the many challenges they faced in staying engaged with school when they had lives complicated by trauma, mental illness, peer problems and general life instability. These challenges had not only made it difficult for participants to complete school but could dissuade them from re-entering education in later life.

Despite these challenges, over half of the school leavers in Wave 3 had entered further education and most were still undertaking some form of study at the time of the survey. Although many of these young people still faced significant life challenges, care leavers who were in education (or employment) were generally doing slightly better across most life domains than young people who were neither in education nor employment. Participant accounts of their lives after care suggest that this lack of educational engagement (or ability to stay employed) was in part the result of some life challenges, especially mental illness, low income and unstable housing, making re-engagement with education a relatively low priority compared to their need to achieve general life stability.

This chapter summarises the key findings in Wave 3 about care leavers' health and their access to health services. In particular, the findings and discussion focus on study participants' generally lower than average levels of psychological and emotional wellbeing. The chapter also explores care leaver accounts of the long-term effects of OOHC experiences and the stresses of life after leaving care on their health and wellbeing.

6.1 General health indicators and disability

In Wave 3 of Beyond 18, participants generally described themselves as being in relatively good health (see Table 6.1). Despite this, they also reported relatively high rates of physical disability or chronic health issues (22%, n = 27), intellectual disability or learning difficulty (17%, n = 21) or both chronic illness or disability and an intellectual disability or learning difficulty (9%, n = 11). Participant responses also indicated that young people were not always obtaining the support they needed for these health issues, with 37% (n = 10) of those with a physical disability or chronic health issue and 57% (n = 12) of those with an intellectual disability or learning difficulty reporting that they had little or no support in living with these health issues. There was a very slight association with young people having a reported long-term health condition and/or intellectual disability and not being in work or education - with 15% (n = 9) of those not in work receiving a disability benefit - but this was not statistically significant.