Court Outcomes Project

October 2015

Download Research report

Overivew

This report presents the findings of the Court Outcomes Project, which forms part of the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments research program that was commissioned and funded by the Australian Government's Attorney-General's Department (AGD).

Executive summary

This report presents the findings of the Court Outcomes Project, which forms part of the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments research program that was commissioned and funded by the Australian Government's Attorney-General's Department (AGD).

The relevant amendments to the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), which came substantially into effect on 7 June 2012, were intended to support increased disclosure of concerns about family violence and child abuse, and to support changed approaches to making parenting arrangements where these issues are pertinent to ensuring safer parenting arrangements for children. The Court Outcomes Project examined the effects of these 2012 reforms on court filings, patterns in court-based parenting matters and the judicial interpretation of key legislative provisions introduced by the amendments.

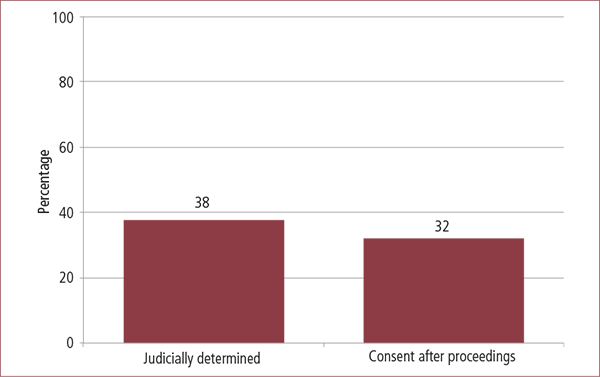

The project has three parts. The first part of the project (the Court Administrative Data Study) involves an analysis of administrative data obtained from the Family Court of Australia (FCoA), the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (FCC) and the Family Court of Western Australia (FCoWA). The data enable assessments of patterns in filings in parenting matters, together with other relevant issues, including filings in relation to Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk, the number of memoranda or reports provided by family consultants and the number of matters in which orders for Independent Children's Lawyers (ICLs) were made. The second part of the Court Outcomes Project (the Court Files Study) involves an analysis of quantitative data collected from pre- and post-2012 family violence amendments samples of family law court files in three categories: those where orders are made following a judicial determination (n = 613); those where consent orders were made after proceedings had been issued (n = 774); and those where applications for consent orders are made without litigation (n = 505). The study examines patterns in orders for parental responsibility and care time, together with a range of other relevant issues, including the prevalence in the files of allegations about family violence and child abuse. The third part of the project (the Published Judgments Study) is an analysis of published judgments that examines how the legislative amendments are being applied in court decision making.

Together, the three studies comprising the Court Outcomes Project provide empirical data on the extent to which changes reflecting the aims of the 2012 family violence amendments are evident in court-based matters. These data provide insight into the extent to which family violence and child abuse concerns were raised in court proceedings before and after the 2012 reforms, and the extent to which any changes were evident in patterns in court orders. These data also identified patterns in filings for court applications and associated documents, including those intended to alert courts to the presence of risks and the application of the amendments that were intended to influence court-based decision making.

This Court Outcomes Project complements the other two elements of the evaluation research program: a study of separated parents' experiences (Experiences of Separated Parents Study [ESPS], incorporating the Survey of Recently Separated Parents (SRSP) conducted in 2012 and 2014), and a study of practices and experiences among family law professional practices (Responding to Family Violence Study [RFV]).

Main findings

Patterns in applications and orders for parenting arrangements

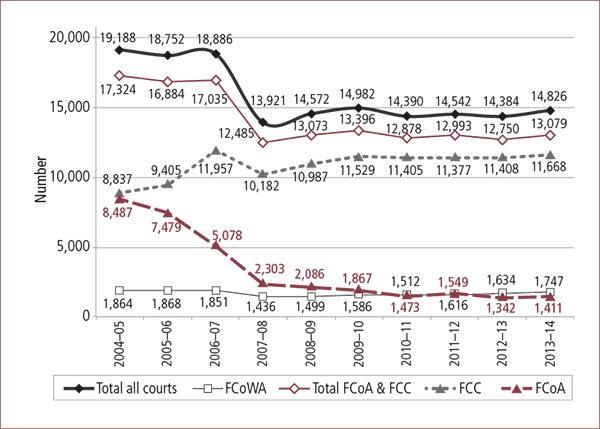

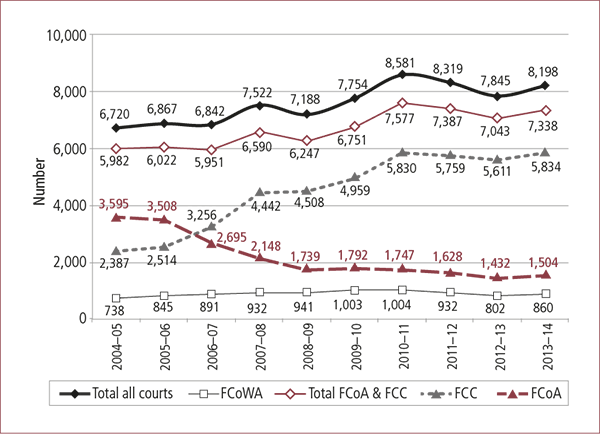

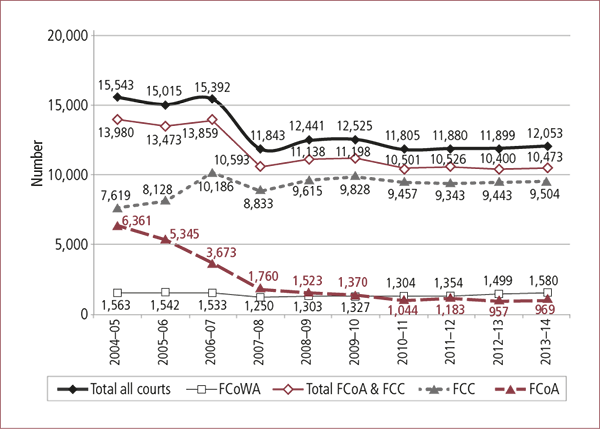

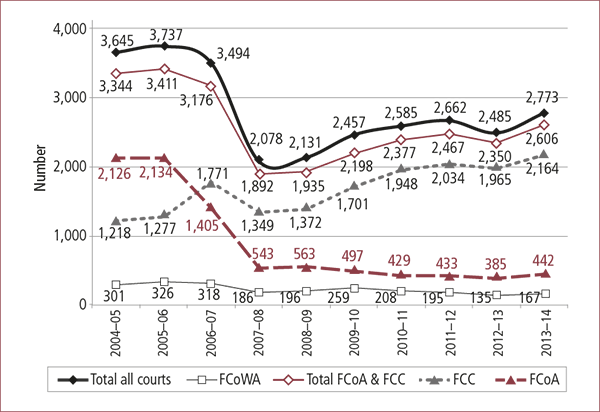

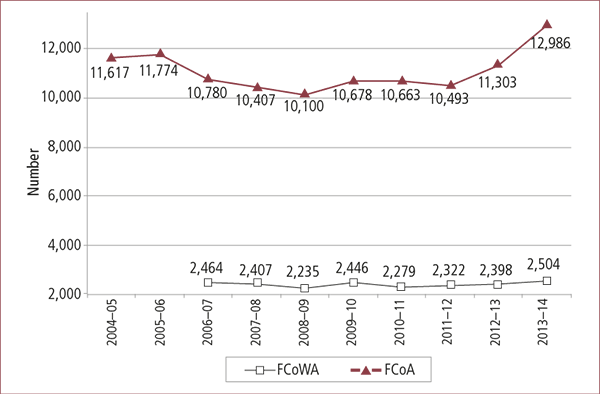

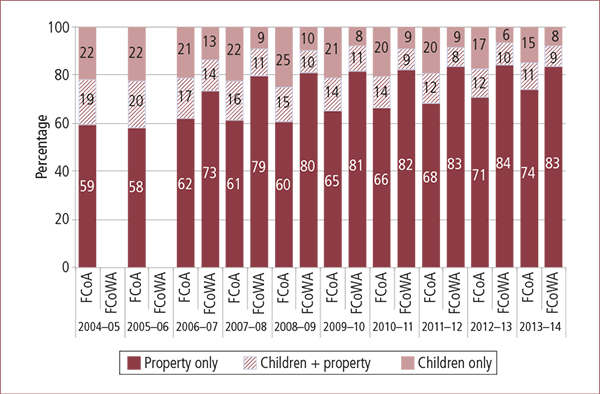

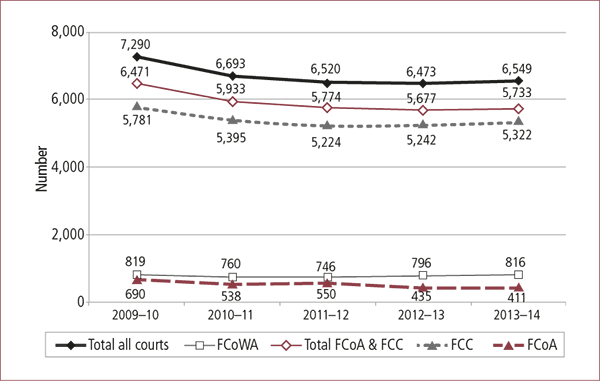

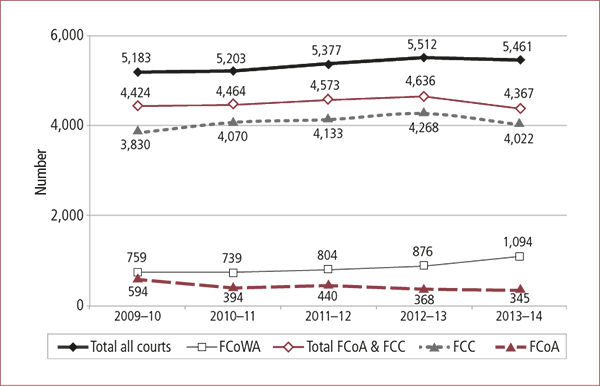

Overall, the Court Outcomes data suggest subtle shifts in patterns of parenting applications and outcomes since the 2012 family violence amendments. The administrative data provided by the FCoA, FCC and FCoWA as part of the Court Administrative Data Study indicate small increases in applications for final orders in matters involving children in the 2013-14 period when compared with prior periods. From 2012-13 to 2013-14, filings increased by 442 to 14,826 applications for final children's orders. Most of this shift was associated with filings in the children-plus-property categories. Increases were also reflected in filings for applications for consent orders in the FCoA and the FCoWA, particularly in the FCoA, rising by 2,493 (to 12,986) since 2011-12. However, much of this increase also appeared to be associated with changing dynamics relating to property matters.

Patterns across the three samples of pre- and post-reform data collected for the Court Files study indicated largely consistent levels in the proportions of orders for shared parental responsibility in the consent after proceedings and consent without litigation samples. Pre-reform, around nine out of ten consent files involved orders for equal shared parental responsibility, but after the reforms such an outcome was less common in the judicial determination sample (51% pre-reform and 40% post-reform).

Different patterns were also evident in orders for equal shared parental responsibility and care time according to whether (a) allegations of either family violence or child abuse were raised; (b) both of these allegations were raised; or (c) neither of these allegations were raised. These court file data suggest subtle shifts in these areas, in a direction consistent with the intention of the 2012 family violence amendments to improve the appropriateness of parenting orders by giving greater weight to protection from harm. Post-reform, children in the judicial determination sample were less likely to be subject to orders for shared parental responsibility in cases involving allegations of family violence and/or child abuse, and less likely to be subject to orders for shared care time (35-65% of nights shared between parents) where these cases involved allegations of both family violence and child abuse, when compared to the pre-reform period. Changes in relation to orders for equal shared parental responsibility were more marked than for care time in the judicial determination sample, while changes for care time were more marked than for parental responsibility in the consent after proceedings sample (which only decreased in cases where neither allegation were raised).

More specifically, shared care-time arrangements were largely stable in the judicial determination sample, applying to 8% post-reform where both family violence and child abuse were raised, compared with 9% pre-reform. In the corresponding consent after proceedings sample, shared care time fell to a statistically significant extent, from 25% to 12%. Shared parental responsibility outcomes were relevant for 54% of the pre-reform judicial determination files involving allegations of both family violence and child abuse, and were significantly lower after the reforms (32%). For consent after proceedings children, shared parental responsibility was ordered for 83% pre-reform and 88% post-reform. In cases where only one of these allegations was raised, the most noteworthy change was in relation to shared parental responsibility orders in the judicial determination sample, which fell by 11 percentage points to 34%. For shared care-time arrangements in this category there was an increase post-reform of 3 percentage points. In the consent after proceedings sample, there appears to be a trend towards shared care-time outcomes post-reform being marginally lower (19% cf. 15%) and shared parental responsibility outcomes being marginally higher (93% cf. 96%), but neither were statistically significant. Where neither allegation was raised, patterns in orders for parental responsibility and care time were largely stable, save for orders for shared care time in the consent after proceedings sample, which decreased to a statistically significant extent from 29% to 13%. Orders involving no face-to-face time between children and one of their parents remained rare in both the pre- and post reform file samples (fathers: 2% pre-reform, 3% post-reform; mothers: < 1% both pre- and post-reform).

In relation to the judicial determination file sample, these data suggest that in the period since the 2012 family violence amendments, courts were more likely to make decisions against shared parental responsibility, but this did not translate into a substantial shift in approaches to care-time arrangements. In relation to consent after proceedings matters, orders for parental responsibility did not change substantially after the reforms, but orders for shared care-time were less frequent, and for mother majority time more frequent. For arrangements reached by consent without litigation, patterns in shared parental responsibility orders did not change substantially, but patterns in shared care-time orders recorded a subtle increase.

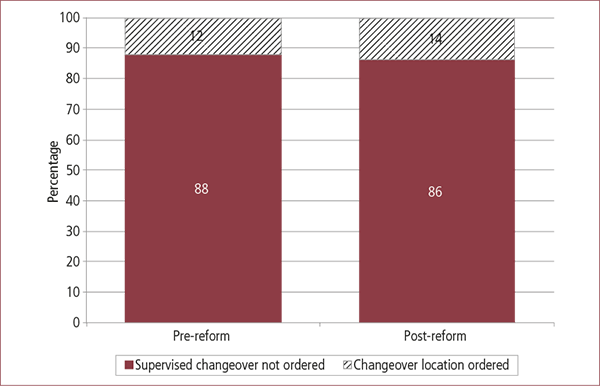

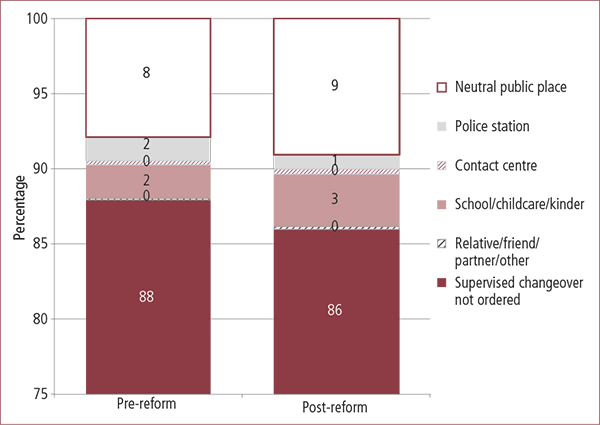

Changes were negligible in the extent to which orders provided for no time with one parent, or reflected arrangements for supervised time, or changeovers to be supervised or at a neutral place.

Disclosure of family violence and child abuse concerns

The Court Outcomes Project data indicate that allegations of family violence and child abuse were raised more frequently in court-based matters post-reform. The proportion of cases in the Court Files Study in which allegations were raised increased from 29% in the pre-reform sample to 41% in the post-reform sample. The proportion of cases in which both family violence and child abuse allegations were raised increased from 8% to 17%, and where child abuse only was raised the proportion increased from 3% to 5%. Where family violence was raised in the absence of child abuse, the proportion of cases remained relatively stable, increasing from 18% to 19%. In both areas, an increase in mutual allegations was evident, but the dynamics behind this increase were unclear.

Overall, the Court Files Study data show that the increase in allegations about family violence and child abuse was just as, if not more evident, in files where allegations of physical abuse and physical violence were made, compared with allegations of emotional abuse and emotional violence. This would tend to suggest that of the two relevant aspects of the reforms - the wider s 4AB and s 4(1) definitions and the various changes intended to support disclosure - it is the latter changes that are more influential in producing these shifts. The data, which show an increase in the number of post-reform files where families had engaged with prescribed child welfare authorities and personal protection order systems, also suggest a positive effect of the reforms in this context. The extent to which children were alleged to have been exposed to family violence increased (although not to a statistically significant extent) from 48% to 58%, but the rate at which allegations were made that children were victims of family violence remained relatively stable (39% to 40%). Increases in the raising of concerns about family violence and child abuse were particularly evident in the judicial determination sample, with increases in the proportion of matters involving these kinds of allegations of between 11 and 14 percentage points. Together, these findings indicate very limited change in the extent to which concerns about children and family violence are raised, suggesting the recognition of children's exposure to family violence in s 4AB(3) has thus far had limited effects.

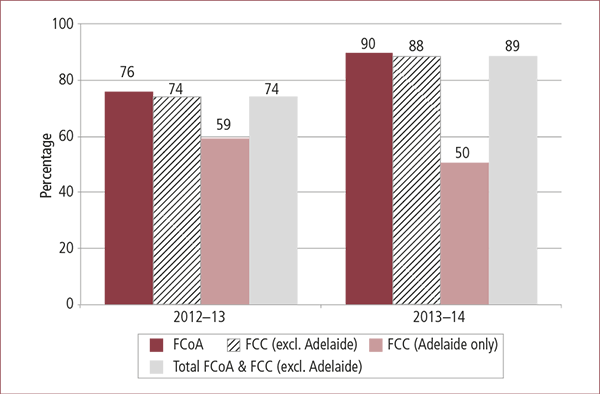

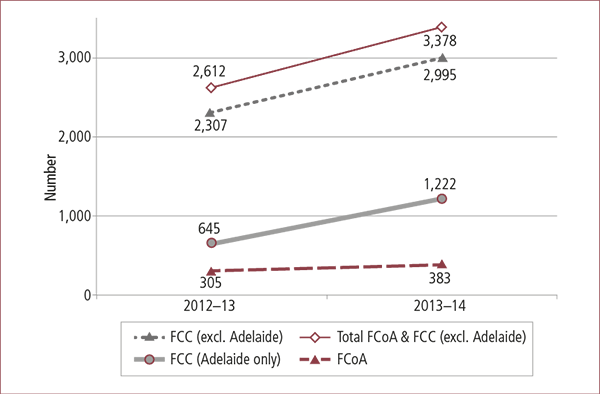

The findings from the Court Administrative Data Study regarding the filing of Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk also supports a conclusion that concerns have been raised more often since the 2012 family violence amendments. Excluding the figures for the Adelaide Registry of the FCC to account for the effect of a pilot program in that registry, the number of Notices of Risk filed nationally increased from 2,229 in 2011-12 to 4,437 in 2013-14. Most of this increase reflects changes in the FCC, with the FCoA and FCoWA having much smaller increases. Data collected since the implementation of the 2012 family violence amendments also indicate an increase in the proportion of Notices of Risk being referred to prescribed child welfare authorities. Increases in both the FCoA (2013-14: 90%; 2012-3: 76%) and in the FCC (excluding Adelaide) (2013-14: 88%; 2012-13: 74%) were identified.

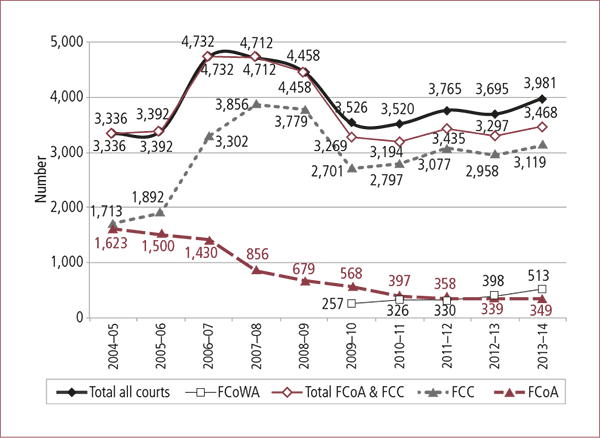

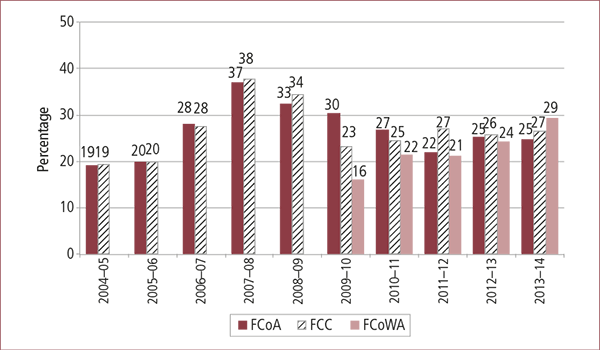

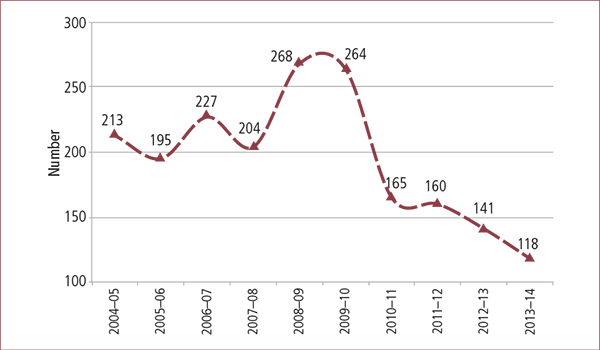

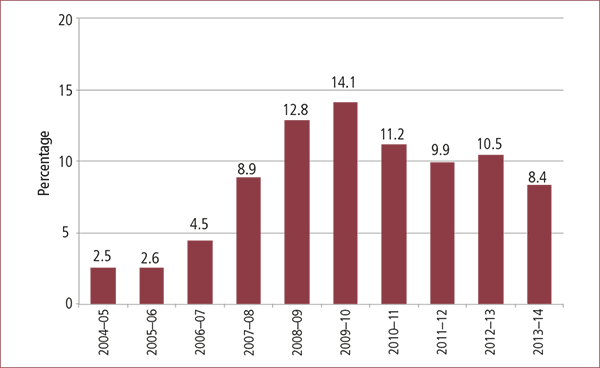

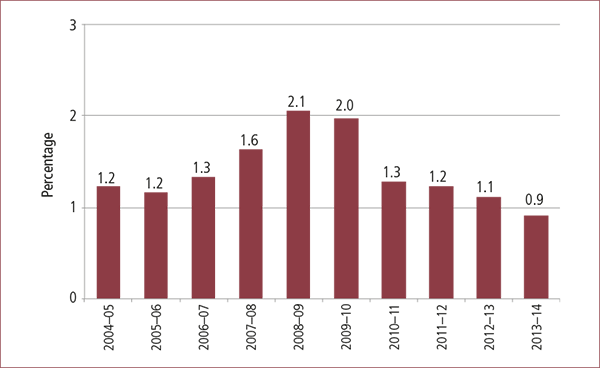

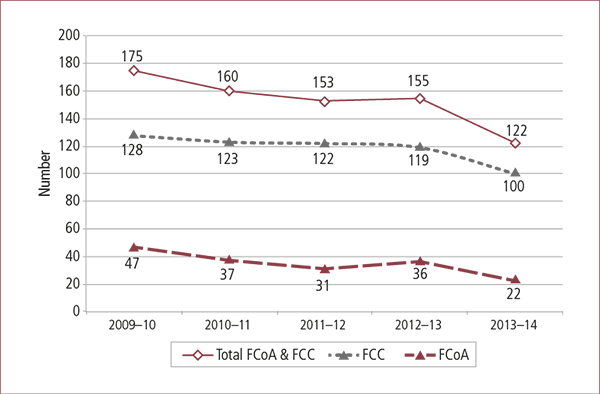

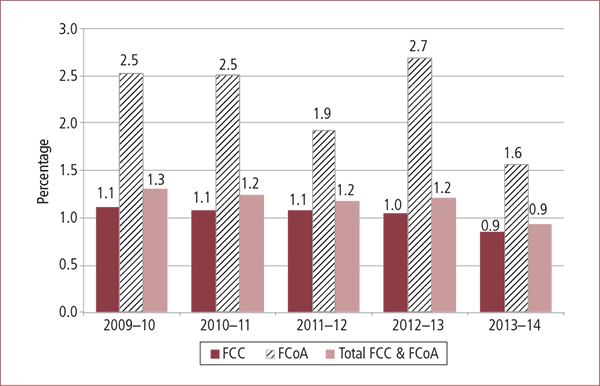

Risk assessments and evidentiary profiles

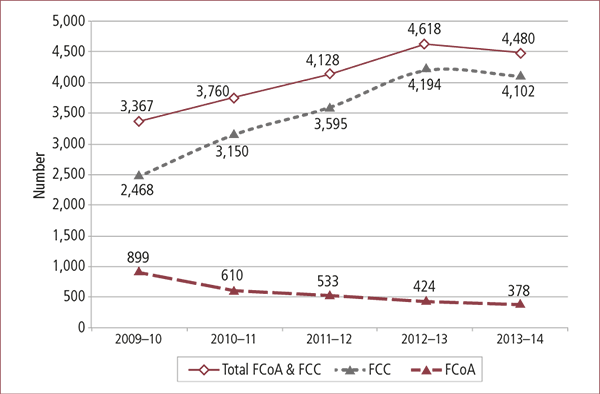

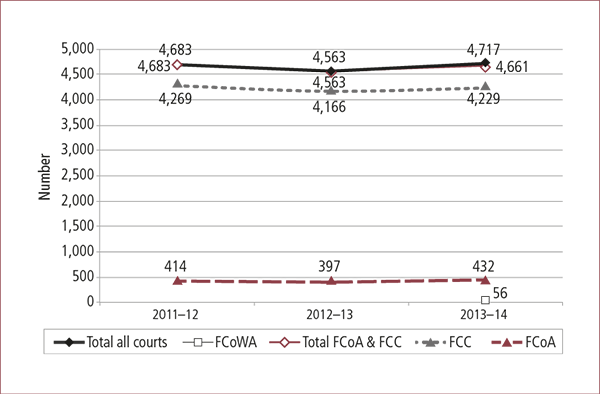

The Court Administrative Data Study indicated a slight decrease in the number of family consultant memoranda (i.e., brief reports) ordered in family law matters following the implementation of the 2012 family violence amendments in the FCoA and the FCC. Following a peak in the number of family consultant memoranda ordered in 2012-13 (n = 4,618), there was a small decline for the most recent period (2013-14) of 138. In contrast, the number of family consultant reports (i.e., longer reports) ordered across all three courts has been relatively steady since 2011-12, when 4,683 Family Reports were ordered. The court administrative data also indicate an increase in the number of matters for which ICL involvement was ordered following the 2012 family violence amendments. In 2013-14, 3,981 orders for ICL involvement were made, compared with 3,695 in 2012-13, with a higher degree of increase in such orders for the FCoWA. While there has been some fluctuation since 2004-05 in the proportion of matters where an ICL has been ordered, the proportion of matters with such orders for 2013-14 were 25% in the FCoA, 27% in the FCC, and 29% in the FCoWA. On the other hand, the number of cases dealt with in the FCoA's Magellan list has declined since the 2012 family violence amendments. After peaking at 268 cases in 2008-09, the number dropped markedly to 165 in 2010-11, followed by a more gradual decline, with 118 cases in 2013-14.

The proportion of files in the Court Files Study samples with evidence in relation to a need to protect children from abuse was present for 22% of the total sample, compared with 11% pre-reform, which represents a statistically significant increase. Family Reports were more likely to be generated in cases involving allegations of family violence and/or child abuse after the reforms (53%) than before (33%). Explicit discussion of risk assessment was more evident in Family Reports after the reforms (31%) than before (22%). Risk was explicitly identified as being present in 28% of the post-reform reports and not present in 29%. The Family Reports indicate that a view either way could not be formulated in 43% of cases. More files included evidence relating to personal protection orders after the reforms (25%) than before (17%), and evidence of engagement with prescribed child welfare authorities was also evident to a significantly greater extent after the reforms (7% before cf. 13% after). Two other areas that were receiving greater emphasis (to a statistically significant extent) in post-reform files were the child's right to meaningful involvement with each parent after separation (11% cf. 7% pre-reform) and evidence referring to the possibility that children's views were influenced (7% cf. 4% pre-reform).

Overall, the Published Judgments Study demonstrated that the constellation of facts and evidence in any given case could determine how particular provisions, including s 4AB, were applied in the context of the given case. The issues relevant to parenting order outcomes highlighted in the Published Judgment analysis included the nature and severity of family violence, the nature of the child's relationship with each parent, and the conclusion formed by the court about whether the family violence was of a level of severity sufficient to justify orders ceasing or restricting parent-child relationships in the context of the behaviour of each parent and the court's conclusion about the nature of the child's relationship with each parent. In some judgments, the validity of a parent's behaviour in raising concerns about family violence and child abuse received significant scrutiny in court decision making, and a variety of approaches, including changing the parent with whom a child spends most time, were applied in situations in which a court concluded that such concerns were unreasonably raised. The Published Judgments Study also considered varying approaches emerging in relation to the application of s 60CC(2A), which explicitly prioritises the primary consideration in s 60CC(2)(b), which relates to "the need to protect children from physical or psychological harm arising from being subjected to, or exposed to abuse, neglect or family violence". The approaches emerging in the analysed judgments included the interpretation of s 60CC(2A) as shifting the balance but not altering the need to consider the evidence as a whole; the operation of s 60CC(2A) acts as a "tie-breaker" (Rhoades, Sheehan, & Dewar, 2013) and the consideration of s 60CC(2A) in the context of applying the unacceptable risk test. A further approach emerging involved judgments reflecting the application of a combination of these approaches to the interpretation and application of s 60CC(2A). The analysis in the Published Judgment Study reinforced the point that family law matters frequently raise very complex factual and evidential issues, giving rise to real challenges when litigating in an adversarial context.

Patterns of service use

There was little indication in the evidence arising in the Court Outcomes data of any significant changes in the patterns of service use following the reforms. As noted above, the analysis of the Court Administrative data identified a national increase of 442 to 14,826 applications for final orders in matters involving children. This increase occurred mostly in relation to applications involving both children and property, suggesting that dynamics more associated with property than children may be relevant in this context. In relation to the use of family dispute resolution (FDR) prior to the issuing of proceedings, the Court Administrative Data indicate that the "certificate" route (where parties attended FDR but were issued with a s 60I certificate) was more common than the "exception" route (where it was determined that parties were not required to attempt FDR). There was a small increase in the former and a similarly small decrease in the latter pathway in 2013-14 compared to the previous year. Overall, however, there was a trend towards the narrowing of the numbers using each of these pathways.

The demographic profiles of the parties in the pre- and post-reform Court Files Study samples were very similar, suggesting little change in the nature of the groups who used the courts before and after the reforms. There was one area where change of a potentially significant nature was evident, and this related to the gender mix of fathers and mothers as applicants and respondents in court proceedings. In the post-reform period, the proportions of fathers as applicants increased (50% pre-reform cf. 44% post-reform) and the proportion of mothers as applicants decreased (53% cf. 47%). It is also noteworthy that the resolution time for judicial determination of parenting matters increased substantially, from 5 to 8 months. This cannot be attributed solely to the 2012 family violence amendments in the absence of evidence about other pertinent issues, including the sampling method applied and the amount of judicial resources available to hear matters.

Summary: Influence of the 2012 family violence amendments

Each component of the Court Outcomes Study identified shifts consistent with the intention of the 2012 family violence amendments, which included measures aimed at improving the disclosure and identification of, and response to, family violence and child abuse in family law matters.

The findings relating to increases in the prevalence of allegations of family violence and child abuse, the filing of Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk and disclosure of engagement with family violence and child protection systems are all consistent with these aims of the 2012 amendments. Also consistent with the intention of the reforms to support safer parenting arrangements for children where there are concerns about family violence and child abuse, are the data indicating shifts in patterns for orders for shared parental responsibility and shared care time in circumstances where allegations of family violence and child abuse are raised. In relation to the judicial determination file sample, these data suggest that in the period since the 2012 family violence amendments, courts were more likely to make decisions against shared parental responsibility, but this did not translate into a substantial shift in approaches to care-time arrangements. In relation to consent after proceedings files, orders for parental responsibility were no less common after the reforms, but orders for shared care time were less frequent, and orders for mother majority time were more frequent.

These patterns suggest that the 2012 family violence amendments have had limited effect on the overall pattern of judicial determination outcomes for care-time arrangements, despite the fact that evidence raising protective concerns was adduced more often than it was before the reforms, and that matters where this evidence was adduced were less likely to resolve without judicial determination than previously. In contrast, in the analysis of the consent after proceedings files, the 2012 family violence amendments were not associated with a downward shift in parental responsibility arrangements, but a correlation was identified between the reforms and changes in orders for the shared care time. It may be that matters that are settled after proceedings are issued are more clear-cut from a factual and evidentiary perspective than those proceeding to judicial determination, such that one party is in a substantially stronger bargaining position from a forensic perspective. The disjunction in the patterns between the two samples nevertheless gives rise to questions about the operation of the legislative framework, particularly given that factual issues raising protective concerns were more common in the judicial determination files than in the consent after proceedings files. It should also be acknowledged, however, that to some extent, the greater prevalence of shared parental responsibility in the consent after proceedings sample may reflect the bargaining dynamics and trade-offs pertinent to negotiation in these contexts.

The analysis of published judgments informs the making of observations about the extent to which the legislative factors influence the patterns described above.

First, given that the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility is not applicable (or is treated in practice as rebuttable) where there are concerns about family violence or child abuse, a reduction in orders for equal shared parental responsibility orders is consistent with an increase in the raising of concerns about family violence and child abuse in court proceedings to a greater extent than before the 2012 amendments, together with a greater willingness on the part of judicial officers to make orders for sole parental responsibility in these circumstances.

Second, less significant shifts in care-time arrangements where concerns about family violence and child abuse were raised invite consideration of why the 2012 family violence amendments have influenced parental responsibility outcomes to a greater extent than care-time outcomes in the judicial determination files, particularly in light of the inclusion of s 60CC(2A). The analysis of published judgments suggests that a range of considerations influence judicial decision making in matters involving family violence and child abuse concerns in the context of the overall decision framework set out in Part VII of the FLA. It highlights the point that judicial determinations involving orders for sole parental responsibility and limited or no care- time arrangements arise in cases where a very severe history of family violence is established and the behaviour of one parent is clearly deficient compared to the behaviour of the other. In cases where courts are persuaded that the situation, including the behaviour of each parent, is less clear cut than this, particularly where the parents' motivation for raising allegations of family violence or child abuse comes into question, then care-time decisions are likely to favour arrangements that maintain relationships with both parents. The data relating to the prevalence of relevant factual issues show that arguments that a parent is undermining the other parent's relationship have been raised more frequently since the reforms, as have been arguments about family violence and child abuse. The question of one parent's capacity to support the child's relationship with the other remains a live issue in court proceedings, especially in the context of the continuing strong philosophy that it is in a child's best interests to maintain relationships with both parents after separation.

1. Introduction

This report sets out the findings of the Court Outcomes Project, which contributes to the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments Project by focusing on the effects of the legislative amendments on parenting matters dealt with in the family law courts by consent or judicial determination. The Court Outcomes Project has three parts. The first part (the Court Administrative Data Study) is an analysis of administrative data obtained from the three family law courts, which assesses patterns in filings in parenting matters and other relevant issues, including filings in relation to Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk, the number of memoranda or reports provided by family consultants (long or short) and the number of matters in which orders for Independent Children's Lawyers (ICLs) were made. The second part (the Court Files Study) is an analysis of court files, which is based on quantitative data collected from family law court files involving matters resolved by judicial determination and consent. The analysis is based on samples of matters resolved before and after the 2012 reforms, allowing a rigorous comparison of outcomes in these two time periods. It examines patterns in orders for parental responsibility and care time, and a range of other relevant issues, including the prevalence in the files of allegations about family violence and child abuse. The third element (the Published Judgments Study) is an analysis of published judgments that examines how the legislative amendments are being applied in court decision making.

The Court Outcomes Project complements the other two elements of the Evaluation Research Program: a study of separated parents' experiences (Experiences of Separated Parents Study [ESPS], incorporating the Survey of Separated Parents [SRSP] conducted in 2012 and 2014), and a study of family law professional practices (Responding to Family Violence Study [RFV]). The research program was commissioned and funded by the Australian Government's Attorney-General's Department (AGD).

1.1 Background

The Family Law Legislation Amendment (Family Violence and Other Measures) Act 2011 (Cth), which came substantially into effect on 7 June 2012, was introduced to support improvements in the family law system's identification of and response to family violence. In particular, it aims to better support the disclosure of concerns about family violence, child abuse and child safety by parents engaged with the family law system, and to encourage professionals to respond to these disclosures in a manner that prioritises protection from harm. These amendments to the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (FLA)1 respond to the findings and recommendations of three reports, namely the Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms (Kaspiew et al., 2009), the Family Courts Violence Review (Chisholm, 2009), and Improving Responses to Family Violence in the Family Law System (Family Law Council, 2009).

The main elements of the 2012 family violence reforms involved:

- introducing wider definitions of "family violence" and "abuse" (s 4AB and s 4(1));

- clarifying that in determining the best interests of the child, greater weight is to be given to the protection of children from harm where this conflicts with the benefit to the child of having a meaningful relationship with both parents after separation (s 60CC(2A));

- strengthening the emphasis placed on protecting children from harm by imposing obligations on advisers2 to inform parents/parties that post-separation decision making about parenting should reflect this priority and that they should regard the best interests of the child as the paramount consideration (s 60D);

- imposing a legislative obligation on an "interested person" (including parties to proceedings and ICLs) to file a Form 4 Notice/Notice of Risk when making an allegation of family violence or risk of family violence (s 67ZBA);

- extending the obligation to file a Form 4 Notice/Notice of Risk when making an allegation to "interested persons" (including ICLs) as well as parties to proceedings that a child has been abused or is at risk of being abused (s 67Z);

- imposing obligations on parties to proceedings to inform the courts about whether the child in the matter or another child in the family has been the subject of the attention of prescribed child welfare authorities (s 60CI);

- imposing a duty on the court to actively enquire about whether the party considers that the child has been, or is at risk of being, subjected or exposed to family violence, child abuse or neglect (s 69ZQ(1)(aa)(i)), and whether the party considers that he or she, or another party to the proceedings, has been, or is at risk of being, subjected to family violence (s 69ZQ(1)(aa)(ii));

- setting out the court's obligation to take prompt action in relation to a Form 4 Notice/Notice of Risk filed in relation to allegations of child abuse or family violence (s 67ZBB);

- amending the additional best interests consideration relating to family violence orders (s 60CC(3)(k)); and

- amending or repealing provisions that might have discouraged disclosure of concerns about child abuse and family violence.

The AVERT Family Violence: Collaborative Responses in the Family Law System (AGD, 2010) and the Detection of Overall Risk Screen (DOORS; McIntosh & Ralfs, 2012) are two further initiatives implemented in recent years with the intention of improving practices in relation to identifying, assessing and responding to risks and harm factors in the family law system context.

1.2 The operation of Part VII of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth): An overview

The legal framework relevant to the resolution of parenting matters is substantively set out in Part VII of the FLA, although relevant definitions are also contained in s 4(1) (abuse in relation to a child) and s 4AB (family violence). There are two sets of provisions that play a critical role in informing decision making in children's matters. One set of provisions provides the infrastructure for consideration of the "best interests" principle, and the other set relates to parental responsibility and care time.

The best interests principle is at the core of both sets, but in different ways. The main provisions that provide guidance for the application of the best interests principle are the Objects and Principles (s 60B), which inform the application of the Part VII framework in a philosophical sense, the principle specifying that the child's best interests are paramount (s 60CA), and the s 60CC enumeration of primary and additional factors that guide the exercise of the best interests discretion. The s 60CC(2) factors are the "primary considerations" relating to the benefit to the child of having a "meaningful relationship" with both parents after separation, and the "need to protect the child from physical or psychological harm from being subjected to, or exposed to, abuse, neglect or family violence". Since the 2012 family violence reforms, the so-called "tie-breaker" provision (Rhoades, Lewers, Dewar, & Holland, 2014), s 60CC(2A), specifies that greater weight is to be given to the latter factor where a conflict occurs between the two factors in any given case. The "additional" s 60CC(3) factors comprise 13 separate provisions, together with a "catch-all" provision that allows the court to take into account "any other fact or circumstance". As part of the 2012 family violence amendments, these provisions were changed so that the court may consider and draw inferences from "any" family violence order (s 60CC(3)(k)), not just those made on a final or contested basis. A provision requiring courts to have regard to the extent to which one parent had facilitated the child's relationship with the other parent was also removed.

The presumption in favour of "equal shared parental responsibility" (ESPR) is at the core of the provisions related to parental responsibility and care time (s 61DA). The presumption in favour of ESPR is not applicable where there are reasonable grounds to consider that a party has engaged in family violence or child abuse (s 61DA(2)). The presumption is also rebuttable on grounds that its application would not be in a child's best interests (s 61DA(3)). Where orders for ESPR are made pursuant to the presumption, courts are obligated to consider making orders for children to spend equal or substantial and significant time with each parent where this is held to be reasonably practicable and in a child's best interests (s 65DAA(1)). Where decision making occurs pursuant to these provisions, the child's best interests remain paramount and the s 60CC(3) factors are also relevant.

In circumstances where the presumption is not applied or rebutted, decision making in relation to parental responsibility and care time are determined by reference to the child's best interests (s 60CA), requiring consideration of the Objects, the Principles (s 60B) and s 60CC. Case law decided since the 2006 shared parenting amendments to the FLA has set out a decision-making pathway that requires orders for ESPR and equal shared care time to be considered as part of the best interests consideration, regardless of whether the ESPR presumption is applied or not (Goode and Goode [2006] FamCA 1346). The High Court has reinforced the necessity for judges to adhere to the legislative decision-making pathway in s 65DAA in order for court orders to be predicated on a valid exercise of legislative power (MRR v GR [2010] 240 CLR 461). This means that the court must be satisfied that orders for equal or substantial and significant care time are in a child's best interests and reasonably practicable.

In the context of the exercise of the best interests discretion (s 60CA), concerns about family violence and child abuse may be relevant at several different points. In addition to the protection from harm consideration in s 60CC(2)(b), two other provisions in s 60CC draw the court's attention to family violence. One raises as a consideration "any family violence involving the child or a member of the child's family" (s 60CC(3)(j)). The other, as noted earlier, requires the court to consider any family violence order. Where findings are made about these issues, they may result in the non-application or rebuttal of the s 61DA presumption and, depending on the severity of them and the significance placed on them in the context of other factors in the exercise of judicial discretion, they may influence the orders for parental responsibility and care time in a variety of different ways, as explained further in Chapter 4. A further relevant provision is s 60CG, which is placed in a section of Part VII that deals with family violence and specifies that orders "should not expose a person to an unacceptable risk of family violence". The patterns in orders for parental responsibility and care time described in Chapter 4 reflect the exercise of discretion under these provisions in the context of factual conclusions in relation to the judicial determination sample. In relation to matters determined by consent, application of the s 60CC "primary" and "additional considerations" is discretionary (s 60CC(5)), although such orders remain subject to the paramountcy of the best-interests principle.

Previous research established that most court orders (whether made by consent or judicial determination) provided for shared parental responsibility after the 2006 family law reforms (Kaspiew et al., 2009). Although shared time is considerably less common in court-determined arrangements than shared parental responsibility, research has also demonstrated that orders involving minimal or no time with one parent are made only where the evidence in support of such an outcome is strong (Kaspiew, 2005a; Moloney et al., 2007), illustrating the longstanding approach that children benefit from involvement with both parents except in cases where dysfunction, including that arising from family violence and child abuse, warrants an outcome inconsistent with this view.

In considering the findings set out in this report, it is important to appreciate that they reflect a legal environment in which there has been limited appellate authority on the interpretation and application of the 2012 family amendments. The discretionary nature of decision making at first instance is evident in the way the new provisions are applied and interpreted in the context of a legislative framework in which discretion determines how particular facts and circumstances will influence the end result. In this context, the discussion based on quantitative data gathered from court files provides evidence on an aggregate basis on the change in patterns for parental responsibility and care time that were evident before and after the reforms. It also demonstrates shifts in the nature and frequency with which particular issues - including family violence and child abuse concerns - are raised in family law court proceedings.

It should also be noted that the legislative pathway set out in Part VII has been described in judicial comment (Marvel v Marvel [2010] FamCAFC 101, [87]; Zabini v Zabini [2010] FamCA 10), practitioner comment (O'Brien, 2010), research (Rhoades et al., 2014) and academic analysis (Fehlberg, Kaspiew, Millbank, Kelly, & Behrens, 2014) as complex, convoluted and not readily understood, especially by lay people.

1.3 Courts, processes and terms

1.3.1 Courts and the legal process

Jurisdiction under the FLA is exercised by three main courts in Australia: the Family Court of Australia (FCoA), the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (FCC; previously the Federal Magistrates Court of Australia [FMCA]) and the Family Court of Western Australia (FCoWA).3 Each of these three courts exercises first-instance jurisdiction under the FLA, and the FCoWA also exercises non-federal jurisdiction under Western Australia's own legislative framework governing the resolution of disputes involving non-married couples (Family Court Act 1997 (WA)). 4 The FCoA has appellate jurisdiction from first-instance judgments of all three family law courts.

In the past decade, significant shifts have occurred in court caseloads, as described in the Family Law Court Filings 2004-05 to 2012-13 report (Kaspiew, Moloney, Dunstan, & De Maio, 2015). One of these shifts has seen a growth in the expansion of the FCC caseload and a contraction in the FCoA caseload, particularly in children's matters, such that the FCC share of filings represents some 86% of the total caseload distribution between the FCC and the FCoA (p. 22).

A further shift, attributable to the increased support for family dispute resolution (FDR) provided as part of the 2006 family law reforms, has resulted in a 25% drop in court filings in parenting matters (Kaspiew, Moloney et al., 2015, p. 7). Under FLA s 60I(6) (which came into full effect from 1 July 2008), parents are required to attempt FDR before lodging an application for parenting matters. In cases involving family violence and safety concerns (or other limited circumstances, including urgency), the matter may be brought directly to court, pursuant to the exceptions to s 60I(9) (the exception route). These concerns may also result in a certificate being issued by an FDR practitioner where a matter is considered unsuitable for FDR (see section 2.2).

The third shift arises from the de facto property reforms in 2008 that saw matters involving post-separation property and financial disputes previously dealt with in the state and territory systems brought into the federal sphere through the referral of powers from the states and territories (except in WA) and amendments to the FLA. Kaspiew, Moloney et al. (2015) noted that between 2008 and 2013-13, the number of applications involving property disputes in the FCoA and the FCC increased by 17% (p. 12).

In light of the aim of the 2012 family violence amendments to better identify matters involving family violence and concerns about children's safety, an element of the Evaluation Research Program (presented here as part of the Court Outcomes Project) was to examine court administrative data to assess patterns in court caseloads and consider issues surrounding the identification of matters involving risk. It should be noted that resource constraints, rather than a lack of need or demand, may be an influence on the findings reported in the forthcoming sections, particularly in relation to family consultant engagement, orders for ICL involvement and the number of matters handled in the Magellan list.

1.3.2 Explanation of terms

A range of terms related to court matters and processes are used in presenting the findings discussed in this report. The explanation for terms that may not be readily understood by non-lawyers is set out in this section.

Family dispute resolution and FLA s 60I

Under s 60I of the FLA, parties are required to attempt FDR prior to lodging a court application for parenting orders (s 60I(1)). Certain exceptions to this requirement apply, including circumstances involving urgency, and matters where there are reasonable grounds to believe there has been, or is a risk of, family violence or child abuse by one of the parties to the proceedings (s 60I(9)). Where these grounds are established, a court may hear a matter without an s 60I certificate being lodged (s 60I(7)). Under s 60I(8), FDR practitioners may issue certificates on the basis that:

- the party did not attend FDR due to the refusal or failure of the other party or parties to attend (s 60I(8)(a));

- the FDR practitioner made an assessment that the matter was not appropriate for FDR (s 60I(8)(aa));

- the parties attended FDR and made a genuine effort to resolve the dispute without success (s 60I(8)(b));

- FDR was attempted but one or both parties did not make a genuine effort to resolve the dispute (s 60I(8)(c)); or

- the parties began FDR, but the FDR practitioner decided it was not appropriate to continue, having regard to the circumstances of the matter (s 60I(8)(d)).

These matters are referred to as being heard as a result of an s 60I certificate being lodged.

FDR and the operation of the exceptions have been extensively examined by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) in a range of reports including: Kaspiew et al. (2009); Qu, and Weston (2014); Kaspiew, De Maio, Deblaquiere, and Horsfall (2012); De Maio, Kaspiew, Smart, Dunstan, and Moore (2013); Moloney, Kaspiew, De Maio, Deblaquiere, Hand, and Horsfall (2011); Qu, Weston, Moloney, Kaspiew, and Dunstan (2014); Kaspiew, Carson, Dunstan, De Maio et al. (2015); and Kaspiew, Carson, Coulson, Dunstan, and Moore (2015).

Independent Children's Lawyers

ICLs are specially trained legal practitioners appointed by legal aid commissions in each state and territory, which also administer the funding for them. They are appointed to represent the best interests of children in particularly complex cases, including those involving serious allegations of family violence and child abuse. Recent research by AIFS has examined the role and efficacy of ICLs (see Kaspiew, Carson, Moore, De Maio, Deblaquiere, & Horsfall, 2014).

Form 4 Notice/Notice of Risk concerning family violence and child abuse

A Form 4 Notice/Notice of Risk is the form that courts require litigants (and other interested persons) to file with an application to alert the courts to cases involving concerns about family violence and child abuse. In the period covered by this research, court practices concerning notices of family violence and child abuse changed, as explained in section 2.3. Other AIFS research relevant to courts and family violence and child abuse includes: Kaspiew et al. (2009), Kaspiew et al. (2014), Higgins (2007), and Moloney et al. (2007).

Magellan

This is a special case management program operated in the FCoA. It is designed to deal expeditiously with parenting matters in the FCoA that involve allegations of sexual abuse or serious physical abuse of children (see Higgins, 2007). It involves collaboration between the FCoA, state and territory prescribed child welfare authorities, police and state/territory legal aid commissions to support an intensively case-managed approach to a limited number of serious matters.

Family consultants

Family consultants5 are psychologists or social workers who work with the family law courts and provide expert clinical assessments to the courts about families involved in court proceedings.6 The family consultant role is set out in FLA Part III. Child Dispute Services,7 which is the service within the FCoA and the FCC that coordinates family consultant activities, employs about 80 internal family consultants, with a further group engaged as sub-contractors pursuant to Regulation 7 of the Family Law Regulations 1984. Family consultants may provide brief reports to the court to inform decision making at an interim stage (s 11F memoranda), or longer reports as proceedings develop (Family Reports, s 62G). All of their dealings with families are reportable to the courts (s 11C). The case management approaches of the FCoA, the FCC and the FCoWA are different, and this means that family consultants operate in a slightly different way in each court (see section 2.4). In the FCoA, the Child Responsive Program is part of the case-management pathway and involves family consultants in several steps, commencing with an intake and assessment interview when a matter begins.8 In the FCC, family consultant engagement occurs where judges make orders for s 11F or s 62G reports. In the FCoWA, in addition to preparing s 11F or s 62G reports, family consultants provide information about child protection and criminal justice engagement where this is relevant to the court the first time a matter is listed for hearing. In 2015, family consultants in the Melbourne and Brisbane registries were conducting a trial of a behaviourally based family violence screening questionnaire to be completed by each party prior to their interview with the allocated family consultant, with the trial expected to be completed in late 2015 (FCoA & FCC, 2015, p. 15).

Consent orders

Arrangements for children and property matters may be made by agreement with or without court involvement. Agreement may occur after an application for final orders has been lodged to initiate legal proceedings. It may also occur as a result of an agreement negotiated in FDR, with or without the assistance of lawyers. Courts make orders by consent in such circumstances, and the agreement then becomes legally binding. Where legal proceedings are not already on foot, they may file an application for consent orders pursuant to the Family Law Rules 1984, Rule 10.15. The FCoA and FCoWA have special forms and processes for this (FCoA: Application for Consent Orders, and FCoWA: Form 11 Application for Consent Orders).

1.4 The evaluation methodology

1.4.1 Overview

The methodology for the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments was based on a mixed-method research program designed to examine the effects of the reforms using several different quantitative datasets. This allowed pre- and post-reform comparisons of patterns in court orders and of the views and experiences of parents and professionals. Unlike the 2006 family law reforms, which were based on a range of policy, legislative and service system changes, the 2012 family violence reforms were primarily based on amendments to the legislation.

The Court Outcomes Project makes an important contribution to the overall Evaluation Research Program as it examines the effects of the legislative changes on parenting arrangements that are reached either through litigation pathways (by judicial determination or by consent after proceedings have been initiated) or through presentation to courts for endorsement as consent orders. A particular focus of the analysis is the extent to which the dynamics involved in litigation in matters where there are concerns about family violence and child abuse have shifted in a direction consistent with the intent of the reforms. The elements based on the Court Administrative Data and Published Judgments Studies support the interpretation of the Court Files Study findings, as well making an independent contribution to examining the wider systemic implications (court filing patterns) and narrower decision-making implications (outcomes in individual cases through the application of the legislation) of the amendments.

1.4.2 Research questions

The overall Evaluation Research Program was guided by a set of research questions. The evidence from the Court Outcomes Project component aims to assess the following aspects of those questions:

1. To what extent have patterns in arrangements for post-separation parenting changed since the introduction of the family violence amendments, and to what extent is this consistent with the intent of the reforms?

The file analysis in the Court Files Study addresses this question by providing quantitative empirical evidence on orders for parental responsibility and care time reached by consent, judicial determination, or consent after proceedings have been initiated. The evidence allows differences in outcomes in matters that do and do not involve family violence and safety concerns to be assessed. The Court Administrative Data Study provides insight into some issues pertinent to the assessment of matters involving family violence and child safety at a systemic level. The Published Judgments Study supports understanding of how the application of the amendments in individual cases contribute to the patterns evident in the file analysis data. (See also question 4.)

2. Are more parents disclosing concerns about family violence and child safety to family law system professionals?

The Court Files Study data provide evidence on the number of cases that involved allegations of family violence and child safety before and after the reforms. The Court Administrative Data Study also sheds light on this question through analysing patterns in the filing of Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk before and after the reforms.

3. Are there any changes in the patterns of service use following the family violence amendments?

The Court Administrative Data Study examines filings in matters involving children across the three courts, providing evidence on patterns in court use.

4. What is the size and nature of any changes in the following areas and to what extent are any such changes consistent with the intent of the reforms?

- Court-endorsed outcomes (consent orders) and court-ordered outcomes (judicially determined orders):

- The Court Files Study addresses this point by providing evidence on patterns in orders for parental responsibility and care time in matters resolved through judicial determination, consent after proceedings have been initiated and matters resolved by consent without an application for final orders being lodged.

- Court-based practices, as reflected in the manner in which practitioners and judges fulfil their obligations under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth):

- The analysis of Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk in the Court Administrative Data Study evidences the extent to which parties and practitioners are meeting their obligations in drawing concerns about family violence and child safety to the attention of courts. The Court Files Study data also examine this issue through analysis of data on the prevalence of allegations of child abuse and family violence and the provision of information about engagement with child protection and personal protection orders systems.

5. Does the evidence suggest that the legislative changes have influenced the patterns apparent in questions 1-4 above?

The analyses in the Court Files and the Published Judgments Studies address this question.

6. Have the family violence amendments had any unintended consequences, positive or negative?

The analyses in the Court Files and the Published Judgments Studies address this question.

1.4.3 Court Administrative Data Study: Methodology

This research involved obtaining and analysing administrative data held by the three courts through submission of a research proposal to each of the court's research and ethics committees. These data were extracted by court personnel from the respective courts' CaseTrack systems. Data for each financial year from 2009-10 to 2013-14 were provided by each court, covering CaseTrack numbers for the following:

- applications for final orders, categorised by children only, property and children, and property only cases;

- matters involving self-represented litigants (data available for FCoA and FCC only);9

- application for consent orders, categorised by children only, property and children, and property only cases (data available for FCoA and FCoWA only);

- matters with a Form 4 Notice/Notice of Risk filed;

- Family Reports and s 11F memoranda prepared;

- orders for the appointment of an ICL; and

- matters involving relocation orders.

An analysis combining these data with those previously provided to AIFS for the years 2004-05 to 2009-10 was then conducted.

1.4.4 Court Files Study: Methodology

Data sourced from court files provide direct evidence about the effects of the legislative amendments on patterns in orders for parental responsibility and care time. The aim of the Court Files Study was to collect and analyse systematic quantitative data from family law court files to allow an assessment of the effects of the 2012 family violence amendments. More specifically, this component of the evaluation involved examining data sourced from files in parenting matters that were finalised by:

- judicial determination (i.e., where parties could not agree and the legal proceedings continued to the final conclusion, with a judge determining the outcome); or

- consent (i.e., where the two parties had reached an agreement during their legal proceedings or by filing an application for consent orders pursuant to the Family Law Rules 1984, Rule 10.15).

The sample was drawn from two time points to enable a comparison of patterns emerging in cases prior to and following the implementation of the 2012 family violence amendments:

- pre-reform: matters initiated after 1 July 2009 and finalised by 1 July 2010; and

- post-reform: matters initiated after 1 July 2012 and finalised by 30 November 2014.10

The study focused on collecting and analysing data relevant to patterns in orders for parental responsibility and care-time arrangements, with an emphasis on comparing outcomes in matters that did and did not involve family violence and child safety concerns.

Data collection

The data collection instrument used in this study was a project-specific instrument developed using FileMaker Pro database software and adapted from the pre-existing database used for the corresponding Court Files component in the Legislation and Courts Project forming part of the AIFS Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms (Kaspiew et al., 2009). This FileMaker Pro instrument enabled quantitative data to be coded into a range of pre-determined fields and related to the following broad categories:

- basic demographic data of applicants and respondents - age, gender, occupation, citizenship, and dates of cohabitation, marriage, separation and divorce;

- information on whether the parties were legally represented and whether an FDR certificate was presented (and the reasons nominated if an FDR certificate was not presented);

- basic demographic data relating to children - age, gender, their relationship to the applicant and respondent, and who the child lives with;

- nature of the proceedings - including the application type, the orders sought by the applicant/respondent for parenting time, supervised parenting time, parental responsibility and relocation;

- factual issues in the case - including allegations concerning family violence and child safety concerns;

- evidence (by type) of family violence and/or child safety concerns submitted to the court;

- whether a Family Report was ordered, whether a risk assessment was conducted by the Family Report writer, the outcome of that risk assessment and recommendations made by way of parenting orders;

- the orders made by the court in the relevant family law proceedings (including family violence orders), together with current or past state personal protection orders; and

- findings made about family violence and/or child abuse in the judgment (if available on file).

Data collection for the Court Files Study commenced on 20 January 2015 and concluded on 30 April 2015. Senior year law students were employed by AIFS as data collectors, working under the supervision of AIFS Family Law Evaluation Team members. Recruitment of the data collectors involved a careful vetting process, and only those with appropriate academic records and experience were employed. As AIFS employees, all data collectors were bound by the same confidentiality and security requirements as members of the AIFS Family Law Evaluation Team.

Following intensive training undertaken by Family Law Evaluation Team members, the data collectors reviewed the sample case files and recorded the incidence of key data items. The initial training and ongoing supervision ensured that the data collectors were equipped with the practical skills to operate the FileMaker Pro database, together with the knowledge to understand the material contained in the court files, the data collection instrument and the coding frame applied.

Ethical considerations

The AIFS Human Research Ethics Committee and the research and ethics committees of the FCoA, the FCC and the FCoWA provided ethical review and approval of the Court Files Study, covering all aspects of the methodology and data collection protocols. Access to identifiable court records occurred only onsite at the courts under supervision of relevant court staff. As noted above, all AIFS staff (including the data collectors) who accessed court records were bound by strict confidentiality agreements and complied with Police Checks and (in applicable states) with Working With Children Checks.

For this study, access to the court files was granted by the Attorney-General under Rule 2.08 of the Federal Circuit Court Rules 2001and Rule 24.13 of the Family Law Rules 2004. Consent was not sought from the families whose files were reviewed as part of this study as it was considered impracticable to obtain informed consent from all individuals who are parties in court records. Court records are developed and maintained for legal purposes and, although they are public documents, they are subject to certain restrictions, including the prohibition of publishing information on parties to, or children subject to, litigation under s 121 of the FLA.

Sufficient privacy and confidentiality protections were put in place throughout the study to mitigate any risks arising from not seeking the consent of families whose files were being reviewed and to ensure that no breach of s 121 of the FLA occurred. All information collected from the court records was de-identified at first reading and no personal data were collected. The data were stored in password-protected encrypted files, which were also used to send regular backups to AIFS via Australia Post's Express Post service during the fieldwork period. The computers and USBs used in the data collection process were also password-protected.

To enable further checking of a file where queries arose during the data collection and verification phase of the study, data were re-identifiable, with court identification numbers substituted by an artificial research number for each case. An identification key was developed for this substitution process and only re-identifiable information was held by AIFS. The identification key was kept in a secure area at the court locations and also in a locked filing cabinet at AIFS. At the completion of the data collection, verification and analysis phase, the identification key was destroyed, at which point the data became non-identifiable.

The data collection for the Court Files Study involved subject matter of a sensitive nature. Family law matters involve issues associated with relationship breakdown, and those before the courts often involve particularly difficult issues, such as family violence, child abuse, substance addiction and mental illness. As such, comprehensive duty-of-care protocols were established to ensure appropriate support and guidance for data collectors employed in the study. These protocols included providing data collectors with telephone access to a Family Law Evaluation Team member at all times, together with opportunities to de-brief with a supervisor and to access support via the AIFS Employee Assistance Program or an AIFS-employed psychologist.

Sample

The sampling strategy employed for the Court Files Study was based on the approach used in the Legislation and Courts Project in the AIFS Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms (Kaspiew et al., 2009). The sample was based on court files drawn from the FCoA and FCC registries in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane and from the FCoWA. The Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane registries handle the majority of all applications filed nationally in these courts and, as such, the resulting samples are representative of a majority of FCoA and FCC cases. Consistent with the Legislation and Courts Project, a sample of pre-reform court files and a sample of post-reform court files from each of these registries were selected via a random sampling strategy.

The rationale for the inclusion of a pre-2012 family violence reform sample, instead of re-using the post-2006 sample obtained for the Legislation and Courts Project, was that this more recent sub-sample was based on cases finalised in an environment that had already been changed by the 2006 amendments. In terms of legal understandings and practice, this environment was anticipated to be significantly different from the one in which the data for the post-2006 reforms sample were collected. Conventional wisdom suggests that it takes time for settled understandings of new legislation to occur, as appellate jurisprudence refines interpretations of the amended law and, as such, a more recent pre-2012 family violence reform sample was needed.

The sampling strategy was devised to achieve a target number of judicial determination files and consent files in each registry. Consistent with the Legislation and Courts Project, these target numbers were based on the courts' filing statistics, the number of files available in each registry and on the Court Files Study budgetary constraints. These target numbers, together with the sample numbers achieved in each category, are outlined in Table 1.1 (pre-reform) and Table 1.2 (post-reform). In relation to the pre-reform period, the sample found to be in scope (see Tables 1.3 and 1.4) was 895, which was 83% of the target sample of 1,076. In relation to the post-reform period, the in-scope sample of 997 was 84% of the target sample of 1,189. More specifically, in relation to the Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane registries, the aim was to achieve a combined total of 100 judicial determination files in each of the FCoA and FCC registries, and a combined total of 180 consent files in each of the FCoA and FCC registries, consisting of both consent after proceedings and application for consent order cases. In relation to the FCoWA, the aim was to achieve a total of 100 judicial determination files and 180 consent files.

| File determination | Court | Location | Population (n) | Target sample (n) | Achieved Sample (n) | In-scope rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: a For FCoWA, it was not possible to differentiate "judicial determination" files and "consent after proceedings" files prior to analysis as the "consent after proceedings" files were treated as "judicial determination" files in the FCoWA sample extraction. | ||||||

| Judicial determination | FCoA | Sydney | 15 | 8 | 8 | 100 |

| Melbourne | 34 | 10 | 10 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 21 | 12 | 8 | 67 | ||

| FCC | Sydney | 102 | 34 | 32 | 94 | |

| Melbourne | 339 | 88 | 85 | 97 | ||

| Brisbane | 225 | 111 | 88 | 79 | ||

| FCoWA a | Perth | 298 | 128 | 72 | 56 | |

| Subtotal | 1,034 | 391 | 303 | 77 | ||

| Consent after proceedings | FCoA | Sydney | 74 | 37 | 36 | 97 |

| Melbourne | 94 | 24 | 24 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 31 | 13 | 11 | 85 | ||

| FCC | Sydney | 223 | 88 | 78 | 89 | |

| Melbourne | 765 | 92 | 92 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 539 | 116 | 104 | 90 | ||

| Subtotal | 1,726 | 370 | 345 | 93 | ||

| Consent | FCoA | Sydney | 428 | 70 | 64 | 91 |

| Melbourne | 636 | 58 | 58 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 973 | 72 | 65 | 90 | ||

| FCoWA | Perth | 398 | 115 | 60 | 52 | |

| Subtotal | 2,435 | 315 | 247 | 78 | ||

| Total | 5,195 | 1,076 | 895 | 83 | ||

| File determination | Court | Location | Population (n) | Target sample (n) | Achieved Sample (n) | In-scope rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: a For FCoWA, it was not possible to differentiate "judicial determination" files and "consent after proceedings" files prior to analysis as the "consent after proceedings" files were treated as "judicial determination" files in the FCoWA sample extraction. | ||||||

| Judicial determination | FCoA | Sydney | 71 | 33 | 29 | 88 |

| Melbourne | 122 | 42 | 41 | 98 | ||

| Brisbane | 75 | 53 | 43 | 81 | ||

| FCC | Sydney | 383 | 70 | 69 | 99 | |

| Melbourne | 1,079 | 52 | 52 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 936 | 67 | 60 | 90 | ||

| FCoWA a | Perth | 991 | 167 | 72 | 43 | |

| Subtotal | 3,657 | 484 | 366 | 76 | ||

| Consent after proceedings | FCoA | Sydney | 202 | 34 | 33 | 97 |

| Melbourne | 230 | 23 | 23 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 107 | 41 | 33 | 80 | ||

| FCC | Sydney | 862 | 113 | 93 | 82 | |

| Melbourne | 2,605 | 96 | 96 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 2,192 | 112 | 95 | 85 | ||

| Subtotal | 6,198 | 419 | 373 | 89 | ||

| Consent | FCoA | Sydney | 1,177 | 67 | 62 | 93 |

| Melbourne | 1,371 | 60 | 60 | 100 | ||

| Brisbane | 2,129 | 69 | 58 | 84 | ||

| FCoWA | Perth | 699 | 90 | 78 | 87 | |

| Subtotal | 5,376 | 286 | 258 | 90 | ||

| Total | 15,231 | 1,189 | 997 | 84 | ||

Table 1.3 shows that 1,415 pre-reform and 1,434 post-reform case records were collected, and 512 and 409 files were deemed to be out of scope in each time period, respectively.

| No. of cases | Inclusion in weighting | Inclusion in analysis | Estimated case population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: There was one case where the coder did not continue due to the target sample being reached. | ||||

| Pre-reform | ||||

| In scope with essential data available | 895 | Yes | Yes | 3,747 |

| Out of scope | 512 | Yes | No | 1,448 |

| Subtotal | 1,407 | 5,195 | ||

| File not located | 4 | No | No | - |

| Duplicate case | 4 | No | No | - |

| Subtotal | 8 | - | ||

| Total | 1,415 | 5,195 | ||

| Post-reform | ||||

| In scope with essential data available | 997 | Yes | Yes | 12,023 |

| Out of scope | 409 | Yes | No | 3,208 |

| Subtotal | 1,406 | 15,231 | ||

| File not located | 9 | No | No | - |

| Duplicate case | 19 | No | No | - |

| Sub-total | 28 | - | ||

| Total | 1,434 | 15,231 | ||

The process of weighting corrects for bias that arises from the different proportions of the population being sampled in each strata or group. Consistent with the Legislation and Courts Project, the following formula was employed to calculate an estimation weight for each sampling group:

weight = population size / collected sample

It was estimated on this basis that for the pre-reform period, 1,448 case files on the sampling frame were out of scope, resulting in 3,747 files being available for analysis. For the post-reform period, 3,208 were estimated as being out of scope, with 12,023 files available for analysis.

Table 1.4 details the reasons for court file records being determined as out of scope in both the pre- and post-reform samples of the Court Files Study. The most substantial proportion of out-of-scope files related to the absence of a final order within the time period allocated to the case via the sampling frame, followed closely by the absence of a substantive Part VII FLA (parenting) matter in the relevant file. The "other reasons" category also represented a substantial proportion of out-of-scope files and included reasons such as the file being related to adoption proceedings, not containing orders consistent with their categorisation by the relevant court, or being unavailable for the data collectors to access during the data collection period.

| Reasons | Pre-reform | Post-reform |

|---|---|---|

| No children's matter (no parenting orders) | 160 | 103 |

| Application not in reference period | 28 | 30 |

| Final order not in reference period | 162 | 127 |

| Combination of 2+ reasons above | 24 | 24 |

| Other reasons | 138 | 125 |

| Total | 512 | 409 |

Data cleaning and analysis

At the conclusion of fieldwork, a number of tasks were undertaken to correct errors and resolve inconsistencies prior to commencing data analysis. Where error messages remained in case records entered in the FileMaker Pro data collection instrument - such as where fields had been left empty by the data collectors and "not applicable" or another similar code should have been entered - these records were inspected and rectified. Serious errors occurred in 225 case records, rendering these data unusable. Where data in case records were incomplete or inconsistent, amendments were made to the case records that reflected the correct entry where this could be ascertained, using codes entered in other fields and/or the detailed notes provided by the data collectors in the notes tool in the FileMaker Pro instrument.

Data were analysed using STATA MP Version 13.

The resulting sample of pre- and post-reform case files in each registry are reported in Tables 1.5 and 1.6. Due to the variations in file numbers for the judicial determination samples in each registry, data were not comparable between registries.

| Court | Sydney | Melbourne | Brisbane | Perth | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-reform | |||||

| FCoA | 108 | 92 | 84 | - | 284 |

| FCC | 110 | 177 | 192 | - | 479 |

| FCoWA | - | - | - | 132 | 132 |

| Total | 218 | 269 | 276 | 132 | 895 |

| Post-reform | |||||

| FCoA | 124 | 124 | 134 | - | 382 |

| FCC | 162 | 148 | 155 | - | 465 |

| FCoWA | - | - | - | 150 | 150 |

| Total | 286 | 272 | 289 | 150 | 997 |

| Court | Judicial determination | Consent after proceedings | Consent | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: a For FCoWA, consent after proceedings files were identified from data collectors file conclusion notes. | ||||

| Pre-reform | ||||

| FCoA | 26 | 71 | 187 | 284 |

| FCC | 205 | 274 | - | 479 |

| FCoWA a | 42 | 30 | 60 | 132 |

| Total | 273 | 375 | 247 | 895 |

| Post-reform | ||||

| FCoA | 113 | 89 | 180 | 382 |

| FCC | 181 | 284 | - | 465 |

| FCoWA a | 46 | 26 | 78 | 150 |

| Total | 340 | 399 | 258 | 997 |

1.4.5 Published Judgments Study: Methodology

The Published Judgments Study involved a systematic analysis of published appeal and first instance court judgments applying the new provisions introduced by the 2012 family violence amendments. The judgments are from the FCoA, the FCC (formerly the Federal Magistrates Court of Australia [FMC]) and the FCoWA, and relate to family law proceedings that commenced after the amendments came into effect in 2012.

A purposive sampling approach was applied in compiling the database of published judgments for this study. This approach involved the review of Full Court (Appeals) judgments and first instance judgments available on the FCoA website, and judgments available on the FCC website and the FCoWA website up to the time of writing. Judgments containing consideration and/or application of the provisions introduced or amended by the 2012 family violence amendments were selected for inclusion in the judgment database for this study.

Searches were also conducted of the relevant Austlii Commonwealth and Western Australian databases: Family Court of Australia - Full Court 2008- ; Family Court of Australia 1982- ; Federal Circuit Court of Australia 2013- ; Federal Magistrates Court of Australia - Family Law 2000-13; Family Court of Western Australia 2004- ; and Family Court of Western Australia - Magistrates Decisions 2008- . Key terms, including "4AB", "60CC(2A)", and "violence" and "abuse", were applied to the "this phrase" search on each of these Austlii databases, and relevant judgments were identified and included in the judgment database.

Summaries were made of relevant judgments for closer analysis and inclusion in this report.

1.4.6 Limitations

The findings presented in this report reflect one component of the Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments, namely those involving some level of family law court intervention. Data collected from the Experiences of Separated Parents Study provides insight into the experiences of recently separated parents accessing non-legal family law services or no formal services, while the Responding to Family Violence study also provides insight into both legal and non-legal professionals' out-of-court experiences, thus providing well-rounded insights when all components of the evaluation are considered together as a whole.

The evaluation methodology is predicated on assessing the implications of the reforms for parenting matters generally, rather than specific types of cases, such as those involving relocation. Further, some of the issues examined in this report involve discussion of data that provides limited insight into the intersection between the federal family law system and state- and territory-based systems involving child protection and personal protection orders. The extent to which these issues are explored is limited by the scope of the evaluation and further research would be needed to understand the broader implications of the issues raised in this report, particularly in relation to the implications for prescribed child welfare authorities of the greater number of referrals of Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk since the reforms.

Time and budgetary constraints also influenced the methodology applied in the Court Files Study and Published Judgments Study components of this Court Outcomes Project. In relation to the Court Files Study, a shorter data collection period was available and an abbreviated data collection instrument (compared to that implemented in the Legislation and Courts Project in the AIFS Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms; Kaspiew et al., 2009) was applied to enable comparison of core categories of data and the collection and analysis of data specific to the post-2012 amendments context. The cases in the post-reform sample reflect applications lodged and determined within two years and four months of the amendments taking effect, in an environment where appellate consideration of the amendments was (and remained) limited. This may mean that further effects of the amendments have yet to unfold. The findings should thus be considered to be indicative of the emerging effects of the reforms rather than being conclusive.

In relation to the Published Judgments Study, time and resource allocation supported limited analysis of judgments from the relevant post-2012 amendment period for the purpose of supporting understanding of the quantitative data in the Court Files Study. Other limitations arising in relation to the Court Administrative Data study related to the reporting of the available data, with data being available from some but not every court on certain issues or in relation to certain time periods, including, for example, data relating to the referral of Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk to prescribed child welfare authorities.

1.5 Structure of this report

This report has three further parts. The first two parts are based on data from before and after the 2012 family violence amendments.

The first part is based on data provided by all three courts in the Court Administrative Data Study. It provides evidence on how the 2012 reforms have affected court procedures, outcomes and caseloads, including analyses of court administrative data on:

- patterns in applications for parenting, property, and parenting and property matters;

- non-FDR cases, dealt with under the exceptions of s 60I or lodged with a s 60I certificate;

- Form 4 Notices/Notices of Risk filed;

- family consultant reports;

- orders for ICLs;

- matters heard in the FCoA's Magellan list; and

- relocation orders.

The second part presents the analysis of data gathered from the files of all three courts as part of the Court Files Study. It includes:

- demographic profiles of the parties and their children;

- an overview of matters that involve allegations of family violence and/or child abuse;

- the evidence on file to address those claims;

- the extent of engagement with child protection and personal protection order systems; and