In the driver's seat II

Beyond the early driving years

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

April 2010

Suzanne Vassallo, Diana Smart

Download Research report

Executive summary

In the Driver's Seat II: Beyond the Early Driving Years is the second report from the collaborative partnership between the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Transport Accident Commission of Victoria and the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria. It further explores the driving experiences and practices of young Victorian drivers, drawing upon data collected as part of a unique Australian study - the Australian Temperament Project (ATP). The ATP is a longitudinal community study that has followed the development and wellbeing of a large group of Victorian children over the first 24 years of life. Starting in 1983, fourteen waves of information have been collected from parents, teachers and young people via mail surveys. Information on young people's driving histories and practices has been collected at 19-20 and 23-24 years of age. The first report, In the Driver's Seat: Understanding Young Adults' Driving Behaviour (Smart & Vassallo, 2005), focused on young people's experiences while learning to drive and their driving practices during their first years of licensure, as well as identifying child and adolescent antecedents of differing problematic driving behaviours, reported at age 19-20.

This second report focuses on young people's driving behaviours at 23-24 years, as reported by 1,000 study members, with six main issues addressed:

- young people's driving behaviours, with comparisons of males and females, and of young people in differing occupations, with differing levels of educational attainment and from urban or rural areas;

- the consistency of driving behaviours from 19-20 to 23-24 years;

- links between drink-driving and other types of risky driving, and between risky driving and substance use;

- overlaps between crash involvement, high-level speeding and fatigued driving;

- the influence of parents on young people's car purchases; and

- links between young people's personal characteristics and their driving behaviours.

Driving behaviours of young people in their mid-20s

Overall trends

Almost all young people (97%) had obtained a driver's licence by 23-24 years of age, with the average length of licensure being almost 6 years. About 7% had experienced a licence cancellation or suspension since first gaining their licence. Approximately half had been detected speeding during their driving careers, and 60% had been involved in a crash while driving since gaining their licence. Crashes resulting in property damage were the most common, while crashes resulting in injury or death were very rare. Most driving took place during the daytime on weekdays, with the average time spent driving at these times being five hours per week. Young people spent less time driving at night or at weekends. Risky driving was relatively common. For example, on one or more of their ten most recent driving trips, close to half had exceeded the speed limit by 11-25 km/h, about two-thirds had driven when very tired, two-thirds had used a mobile phone function (such as receiving or sending an SMS), and around half had talked on a mobile phone. One in five 23-24 year-olds had driven when near or over the legal alcohol limit during the previous month. Over 40% had friends who engaged in drink-driving, and about one in eight had a partner who had driven when over the legal limit. Two-thirds of young people “always” made plans to avoid drink-driving, and about three-quarters of those who made plans did not subsequently engage in drink-driving. The most common strategies used to avoid drink-driving were to plan ahead and arrange alternate transport to their destination (e.g., have someone else drive, take a taxi or ride on public transport), or to alter their drinking habits (e.g., not drink at all, or reduce the amount of alcohol consumed).

Gender differences

Young men and women significantly differed on many aspects of driving. Young men had more often had their licence cancelled or suspended, and while there were no differences in the occurrence of crashes, young men had more often been apprehended for a driving-related offence. Additionally, they tended to engage more frequently in a range of unsafe driving practices (e.g., high-level speeding, driving when affected by alcohol). On the other hand, young women had more often driven when fatigued. Young men were also more likely to be among the small group who rarely made plans to avoid drink-driving, and to more often end up drink-driving if they had made such plans. There were also gender differences in the strategies used to avoid drink-driving, with young men being more likely to alter their drinking habits (drinking less, counting or spacing their drinks, or drinking low-alcohol beer), and young women more often abstaining from drinking altogether.

Occupational status

Young people were divided into groups according to their occupational status as classified on the ANU-4 Occupation Status scale (Jones & McMillan, 2001). Low, average and high status groups were formed (25%, 51% and 24% of the sample respectively). Very few differences were found in the three groups' driving histories and behaviours, for example in their licensing history, driving patterns, crash involvement or rate of apprehension for driving-related offences.

Educational attainment

Three groups were formed on the basis of the highest level of education that young people had completed: Year 12 or less (30%), post-secondary education but not university (26%), and university (44%). Most differences centred on the university-educated group. These young people had less often been detected speeding, were less likely to have had their licence cancelled or suspended, were less likely to have friends who were drink-drivers, more often used forward planning when making plans to avoid drink-driving, and were less likely to drink-drive after making these plans.

Residence locality

Young people living in metropolitan (68%) and non-metropolitan (31%) areas were compared using the Australian Bureau of Statistics “met” and “ex-met” categories (capital city statistical division vs the rest of the state). As a group, those from metropolitan areas had more often been involved in a crash, and had been involved in a higher number of crashes. Additionally, rates of hands-free mobile use when driving were higher among young people from metropolitan areas, whereas non-metropolitan drivers were more likely to have not worn a seatbelt when driving. While there were no significant differences in the occurrence of drink-driving, differences were found in the strategies used to avoid it. Whereas non-metropolitan drivers were more likely to leave their car behind and find an alternate way home (e.g., be driven home, take a taxi or public transport, find another way home), metropolitan drivers were more likely to alter their drinking habits (e.g., drink less, count or space drinks, or drink more water or soft drinks).

Consistency of driving behaviours from 19-20 to 23-24 years

Driving trends across the whole sample were examined to determine whether young people's driving tendencies remained similar or had changed as they gained more experience on the road. There was a slight decrease in high-level speeding and driving without a seatbelt from 19-20 to 23-24 years among the ATP sample; however, rates of other types of risky driving tended to increase or remain stable. Driving when fatigued remained very prevalent, and driving when affected by alcohol increased substantially. Thus, when 23-24 year olds did engage in risky driving, they did so almost as frequently as did 19-20 year olds. This suggests that (when present) risky driving is as serious an issue in the mid-20s as in the late teens, and points to the importance of sustaining road safety efforts into the twenties. Young people identified as showing high, moderate and low levels of risky driving at 19-20 years were followed forward to determine whether they would continue to show similar driving patterns at 23-24 years. High stability was found among those with low levels of risky driving, but less stability was found among those showing moderate and high levels, the majority of whom were less problematic at 23-24 years. The benefits of young people not engaging in risky driving in the early years of their driving careers were highlighted, since very few subsequently became high-level risky drivers. Encouragingly, the findings demonstrated that young problem drivers were not destined to continue posing a road safety risk as they grew older, with improvement found to be common.

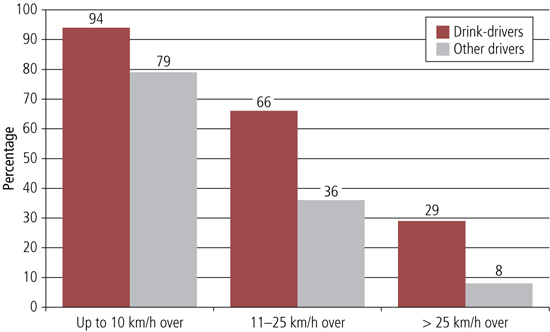

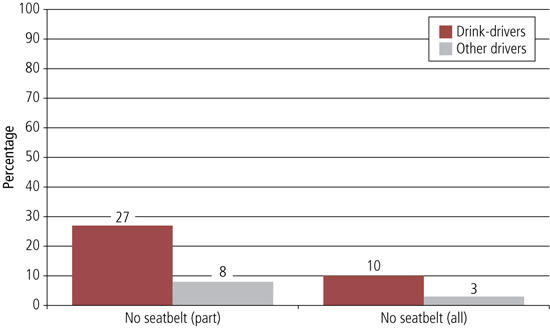

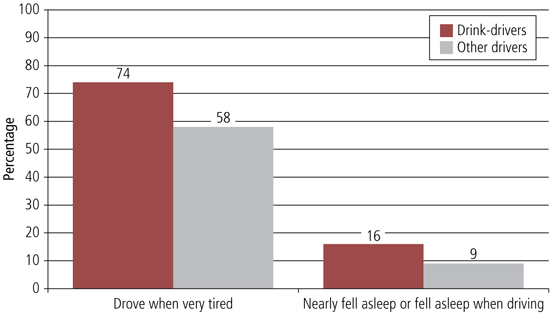

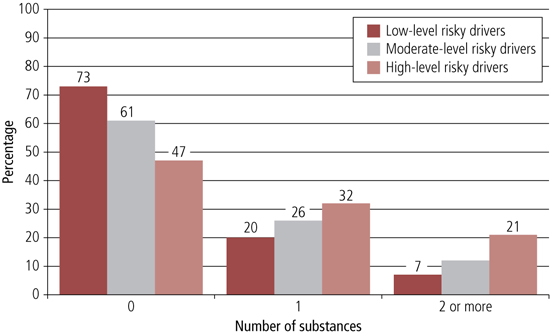

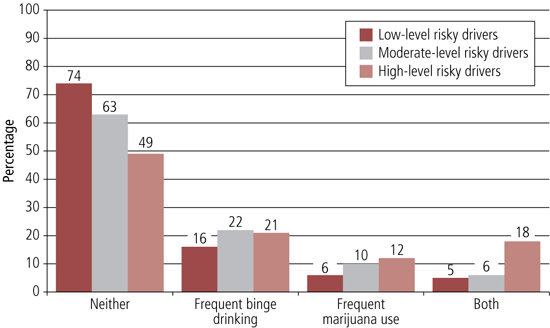

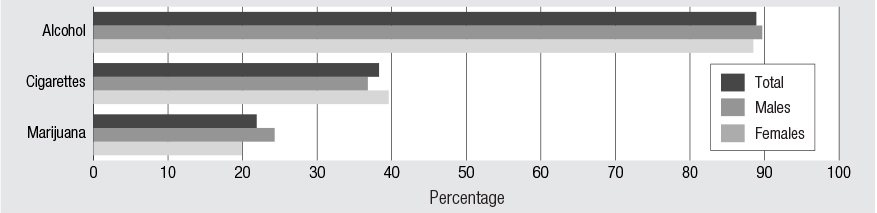

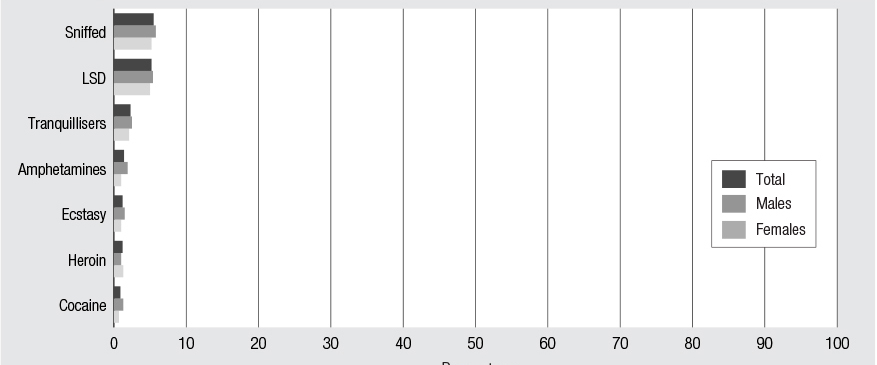

Risky driving and substance use

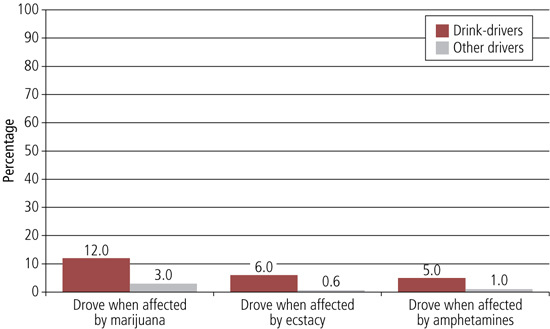

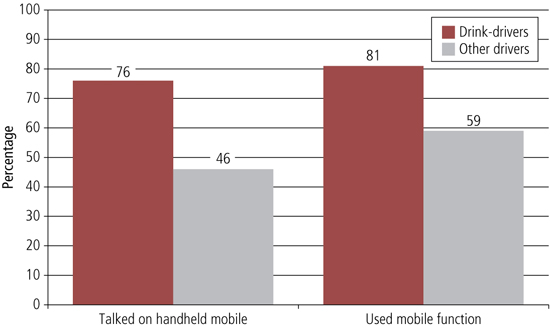

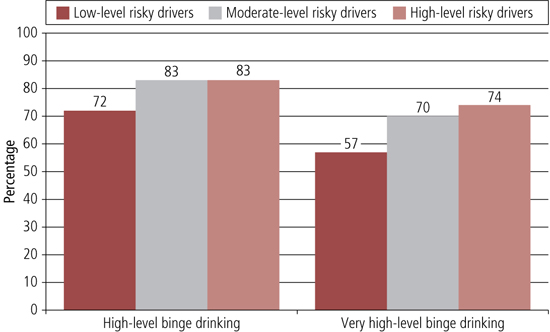

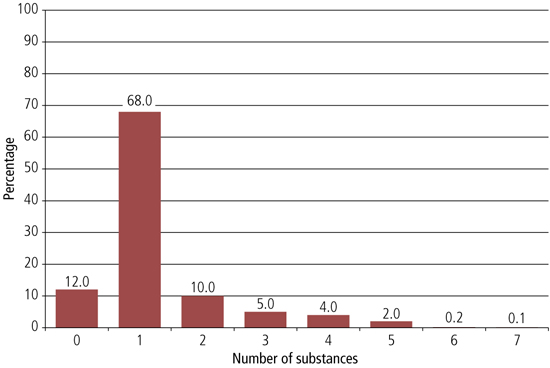

Early adulthood can be a period of considerable risk-taking: the prevalence of substance use reaches a life-time high (Spooner, Hall, & Lynskey, 2001), while other forms of risk-taking common at this age include antisocial behaviour, gambling and risky driving. Little is known about the degree to which risk-taking co-occurs among young people in their mid-20s. Accordingly, the co-occurrence of risky driving and substance use was investigated. Two main questions were explored. First, we investigated whether young people who engaged in drink-driving were more likely to engage in other types of risky driving. This was found to be the case, with speeding, and driving without a seatbelt, when fatigued, under the influence of an illegal drug or when using a mobile phone, all being considerably more common among young drink-drivers than among other young drivers. Second, young people who showed high, moderate and low levels of risky driving were compared on their engagement in substance use. Binge drinking, and marijuana, ecstasy and amphetamine use were all significantly higher among high- and moderate-level risky drivers, with the strongest differences being found on binge drinking and marijuana use. Further, high- and moderate-level risky drivers were more likely to engage in multi-substance use, and did so more frequently than low-level risky drivers. Risky driving appeared to be one element of a risk-taking lifestyle for a number of young people. Thus, young risky drivers would likely benefit from interventions that not only target their behaviour on the road, but also other aspects of their lives, suggesting a role for more broad-based “common solutions” approaches in addition to targeted approaches to road safety.

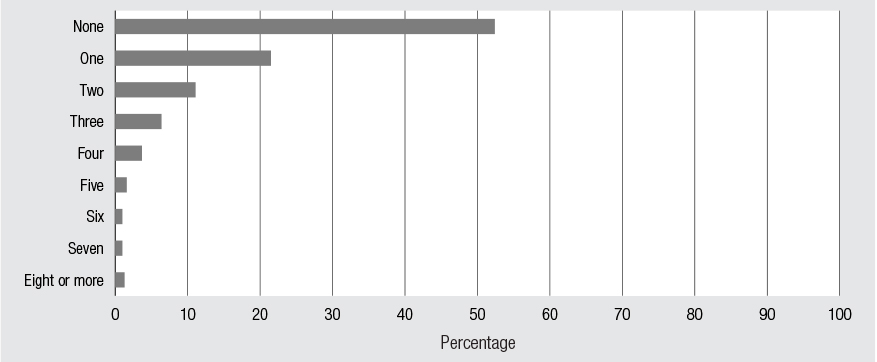

Crash involvement, speeding, fatigue and other aspects of road safety

As well as looking at whether risky driving co-occurred with substance use, the overlap of differing types of road safety behaviours themselves was explored. Inter-connections between three problematic driving outcomes - crash involvement, high-level speeding and fatigued driving - were investigated. Considerable similarity was found in the driver histories and behaviours of young people who had been involved in multiple crashes as drivers, had recently engaged in high-level speeding (more than 25 km/h over the limit), or had recently driven when very tired. Thus, higher rates of apprehension for driving-related offences and engagement in a wide range of other risky driving practices were evident. Further, 57% of those who had experienced multiple crashes since starting to drive, 72% of high-level speeders, and 45% of fatigued young drivers had engaged in another of these three problematic driving outcomes. These findings suggest that problematic driving does not occur in isolation, and may reflect a risk-taking approach to driving among some young drivers.

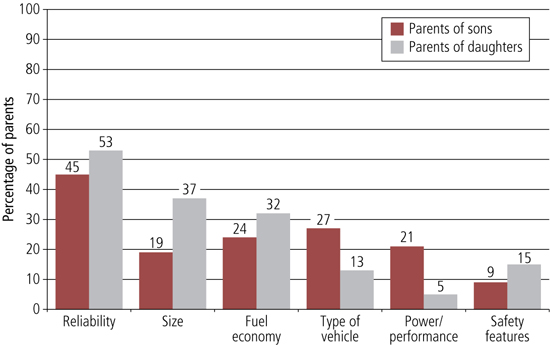

Parents' influence on young people's car purchase

Parents can play an important role in the driving behaviour and attitudes of young people. One way in which this may occur is through the advice and support they provide when young people are purchasing a car. Approximately 80% of 23-24 year olds had purchased a car since gaining their licence, and close to two-thirds of their parents had helped with the choice of a vehicle. Of these parents, almost 90% thought they had influenced their son's/daughter's choice to some degree, with about 30% feeling they had had a large influence. Parents were more likely to have had an influence if the relationships between the young people and their parents were close. Parents are not often considered in road safety efforts targeted at young drivers. However, there may be scope to make greater use of their influence, most obviously in relation to young people's purchase of a vehicle, but also more generally in relation to young people's driving behaviour and attitudes.

Personal characteristics

Links were explored between young people's propensity for risky driving and their personal strengths (social skills, temperament style) and lifestyle factors (employment, relationships, “settling down”). Individuals who drove in a law-abiding manner tended to show greater empathy, responsibility and perspective-taking than other drivers, as well as closer connections to parents and more tolerant attitudes. These findings are a reminder that what an individual is like as a person impacts on his/her behaviour behind the wheel. They point to the value of helping young people gain an understanding of their personal style and how this might affect their approach to driving.

Conclusions

The findings of this second report build upon those from the first report to increase our understanding of the road safety behaviours of young Victorians at an age that has often been overlooked - the mid-20s. The report provides an examination of the degree to which young people engage in risky driving practices once they have become experienced drivers, as well as the continuity of risky driving beyond the novice driving years. The findings provide significant Victorian evidence that can inform intervention and prevention efforts aimed at reducing risky driving among young people.

1. Introduction

This is the second report from the collaborative partnership between the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Transport Accident Commission of Victoria and the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria. The collaboration began in 2002 when the Institute was commissioned to collect and analyse data on the driving experiences and practices of young Victorians, using data from the Australian Temperament Project (ATP) research study. The first report, In the Driver's Seat: Understanding Young Adults' Driving Behaviour, was prepared by Smart and Vassallo in 2005.

The Australian Temperament Project is a longitudinal study which has followed the development of a cohort of Victorian children from infancy to young adulthood, with the aim of tracing pathways to psychosocial adjustment and maladjustment across the lifespan (Prior, Sanson, Smart, & Oberklaid, 2000). The initial sample comprised 2,443, 4-8 month old infants and their parents, who were representative of the Victorian population when recruited in 1983. Fourteen waves of data have been collected thus far, using mail surveys, with the young people aged 23-24 years at the last collection in 2006. Parents, teachers and the young people themselves have responded to the study at various stages of the young people's development.

1.1 Major findings from the first report

The first report from the collaborative partnership (Smart & Vassallo, 2005) examined three broad issues:

- the learner driver experiences and driving behaviours of 19-20 year olds:

- precursors and correlates of three problematic driving outcomes (risky driving, crash involvement and speeding offences): and

- connections between risky driving at 19-20 years and other problem behaviours (substance use and antisocial behaviour).

Learner driver experiences and driving behaviours

Eighty-six per cent of the young people had obtained a probationary car driver's licence by 19-20 years of age. While there was considerable diversity in the number of professional driving lessons young people had undertaken, most commonly this was between one and five and seldom more than ten. About 80% had practised driving on at least a weekly basis when learning to drive; typically with their parents. While some stress or conflict was common during practice sessions with parents, this was generally minor.

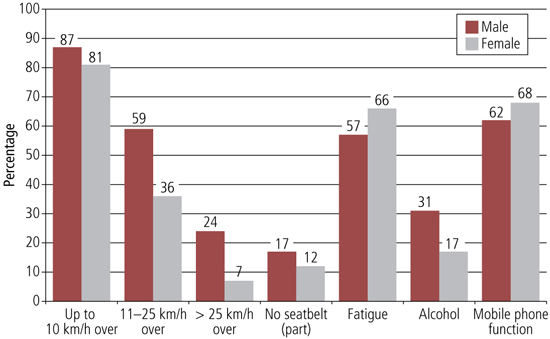

In terms of young people's more recent driving patterns, there was considerable variability in the number of hours that young people spent driving at different times of the day and week. However, on average, young people spent a total of 5 hours on weekdays and 3 hours on weekends driving during daylight hours. Night-time driving was less frequent, occurring, on average, for 2½ hours during the week, and 2 hours on weekends.

Forty-three per cent of young drivers had been involved in a crash since gaining their licence, while approximately 30% had been detected speeding by police at least once.

Speeding was the most common unsafe driving behaviour reported by this 19-20 year old cohort. Driving when fatigued was also relatively common. Other unsafe driving behaviours, such as failing to wear a seatbelt and driving when affected by alcohol or illegal drugs were less prevalent. Young men engaged in unsafe driving behaviours more often than young women (particularly speeding, driving when affected by alcohol, and non-seatbelt use), and were also more likely to have been detected speeding by police.

Precursors and correlates of risky driving, crash involvement and speeding

The precursors and correlates of three problematic driving outcomes - risky driving, crash involvement and speeding - were investigated. Groups exhibiting low, moderate and high levels of each outcome were identified. The precursors and correlates of each outcome type were then investigated by comparing the resultant groups on a wide range of characteristics assessed at 19-20 years or earlier in life.

Young adults in the groups exhibiting high-level risky driving, multiple crashes and/or multiple speeding violations differed from other drivers on a wide range of domains. They tended to be more aggressive; engage more frequently in antisocial acts (for example, property offences or violence); have a less persistent temperament style (have difficulty in seeing tasks through to completion); use more legal and illegal substances; and have friendships with peers who tended to be involved in antisocial activities. In addition, young people in the high-level risky driving and/or multiple speeding violations groups tended to be more hyperactive, less cooperative, and had experienced more school adjustment difficulties than other drivers.

Common precursors shared by the high-level risky driving and multiple crashes groups were a more difficult parent-child relationship and a tendency to use less adaptive coping strategies. There were also some personal attributes and environmental characteristics that were uniquely associated with each driving outcome.

Group differences tended to be more powerful, more consistent and emerge earlier (in mid- to late childhood) among the risky driving and speeding violation groups than among the crash involvement groups (which emerged in mid- to late adolescence).

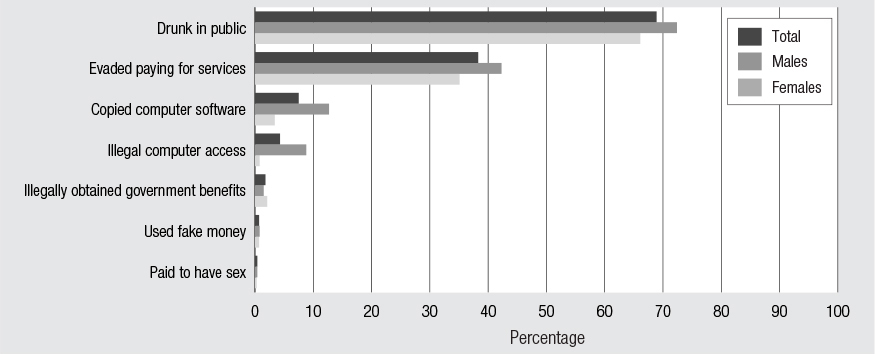

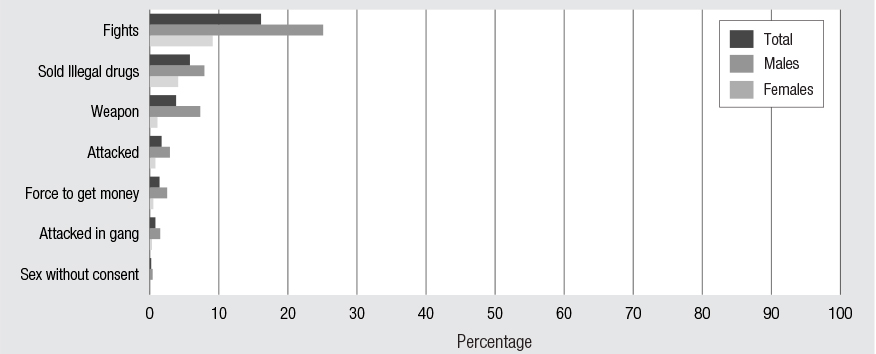

Relationship between risky driving and other problem behaviours

The degree of overlap of different types of problem behaviours was explored in two ways. Firstly, in order to identify common and unique risk factors, the longitudinal precursors of risky driving in early adulthood, adolescent antisocial behaviour, and adolescent multi-substance use were compared. Some overlap was evident, with aspects of temperament style, behaviour problems, school adjustment and interpersonal relationships predicting all three types of problem behaviour. Secondly, levels of antisocial behaviour and substance use among 19-20 year old low-, moderate- and high-level risky drivers were examined. High-level risky drivers engaged more often in antisocial behaviour and used alcohol, marijuana or both substances more frequently than less risky drivers. Furthermore, looking back in time, high-level risky drivers had displayed higher levels of antisocial behaviour and substance use during adolescence.

1.2 The second report

Considerable attention has been devoted to understanding the driving behaviours and characteristics of young, novice drivers. This focus is understandable, given the evidence that novice drivers are approximately three to four times at greater risk of being involved in a crash resulting in injury or death than older drivers (Cavallo & Triggs, 1996; Clarke, Ward, & Truman, 2002)

However, much less attention has been given to the on-the-road behaviours of young drivers past the early years of their driving careers to see how their driving patterns and behaviours change as they mature and gain driving experience.

The collection of a second wave of road safety data among the ATP cohort at 23-24 years, provided a valuable opportunity to examine the driving practices and experiences of this cohort of young Victorians at a later stage of their driving careers. Thus, the collaborative partnership between the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria and the Transport Accident Commission of Victoria was extended, enabling an exploration of issues such as the stability or change in young people's approach to driving from the pre- to mid-20s, as well as a more detailed focus on specific road safety issues that are of particular concern at this life stage (such as drink-driving).

This second report focuses on six broad issues that can further increase understanding of the driving behaviour of young Victorians. These are:

- the driving behaviours and experiences of young people in their mid-20s;

- the consistency of driving behaviour over time (between the ages of 19-20 to 23-24 years);

- links between drink-driving and other forms of risky driving, and between risky driving and alcohol or other substance use;

- connections between crash involvement, high-level speeding, fatigued driving and other aspects of road safety;

- the influence of families on young people's car purchases; and

- links between 23-24 year olds' personal characteristics and their driving behaviours.

2. Australian Temperament Project

The Australian Temperament Project is an ongoing longitudinal study that has followed the development of a large group of young people born in the state of Victoria, Australia, from infancy onwards (for a fuller account see Prior et al., 2000, or visit the ATP website <www.aifs.gov.au/atp>). The project is a collaboration between researchers from the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Royal Children's Hospital, the University of Melbourne and Deakin University. It is led and managed by the Australian Institute of Family Studies and is supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council. The research presented in this report was supported by the Transport Accident Commission of Victoria and the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria.

2.1 Survey methodology

The ATP commenced in 1983 with a representative sample of 2,443 infants and families from rural and urban areas of Victoria. Participants were recruited from a subset of Victorian local government areas selected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics to provide a representative sample of the state's population in terms of parental education level, occupational status and ethnic background. All parents with an infant aged between 4 and 8 months who visited their local Infant Welfare Centre1 in the chosen local government areas during the first two weeks of May 1983 were invited to participate in the project. At that time, Infant Welfare Centres were very widely used, making contact with roughly 94% of all live births. As a final step in the recruitment process, comparison of the recruited sample to Census data confirmed that the sample was representative of the state's population (Sanson, Prior, & Oberklaid, 1985).

Fourteen waves of data have been collected via mail questionnaires to date. The first four waves of data were collected at annual intervals from infancy to 3-4 years of age. From the commencement of primary school up to 19-20 years, the data collections were conducted at two-yearly intervals, with an additional assessment completed during the first year of secondary school in order to track children's adjustment and wellbeing over this important developmental transition. More recently, there was a four-year gap between the survey waves at 19-20 years and 23-24 years.

The questionnaires have assessed many aspects of the young peoples' lives, including their temperament, health, social skills, behavioural and emotional problems, risk-taking behaviours, educational and occupational progress, and peer and family relationships, as well as family functioning, parenting practices and socio-demographic background.

At every survey wave, parents have completed questionnaires about aspects of family life and their child's functioning. School teachers also reported on the child's school and social progress, personal adjustment, and temperament style at the preparatory grade, Grade 2 and Grade 6 survey waves. From the age of 11 onwards, the young people themselves have completed questionnaires regarding a range of topics, including relationships with others, attitudes and beliefs, and personal adjustment. The availability of data from multiple informants for most domains and at most survey waves has provided researchers with a rich and reliable account of this cohort as they have progressed from infancy to early adulthood.

Approximately two-thirds of the original cohort is still participating in the study after 24 years. A higher proportion of the families no longer participating are from lower socio-demographic backgrounds or include parents born outside Australia. Nevertheless, there are no significant differences between the retained and no-longer-participating subsamples on any infancy characteristics.

The findings presented in this report are based on a sample of 1,000 young adults (61% female), who participated in the most recent survey at 23-24 years. This represents a response rate of 67% of those who were still involved in the study at this stage.

Driver behaviour measures

At the 2006 data collection wave, at 23-24 years of age, study members completed a series of questions about their driving experiences and behaviours. Parents provided parallel information on these topics. The measures used to assess these issues are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Statistical analysis strategy

Throughout this report, a number of statistical tests are reported in relation to each topic under investigation. When multiple statistical tests are undertaken, the likelihood of Type 1 error (a finding of significant differences when there is no such difference) is increased. To reduce this risk, an adjusted significance level of p < .01 is used. For reader interest, results that are significant at the conventional p < .05 level are reported as trends, but are not interpreted.

For categorical data, Pearson chi-square and logistic regression analyses were undertaken, with inspection of standardised residuals used to identify cells in which there was a significant departure from chance. For continuous data, t tests and analyses of variance were undertaken, with post-hoc tests used to investigate specific group differences.

| Question | Response categories |

|---|---|

| Type of licence held | None, learner, car, and/or motorbike ("ever held" at 23-24 years) |

| Type of licence held now | None, learner, car, and/or motorbike |

| Length of time since first gained licence | Years and months |

| Ever had licence cancelled or suspended | Yes, no |

| In a normal week, how much time spent driving a car or riding a motorbike on Monday-Friday in daylight hours | Number of hours |

| In a normal week, how much time spent driving a car or riding a motorbike on Monday-Friday in night-time hours | Number of hours |

| In a normal week, how much time spent driving a car or riding a motorbike on Saturday-Sunday in daylight hours | Number of hours |

| In a normal week, how much time spent driving a car or riding a motorbike on Saturday-Sunday in night-time hours | Number of hours |

| Experience of crash/accident when s/he was the driver | Yes, no |

| Number of crashes/accidents when s/he was the driver | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: driving alone, damage but no personal injury | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: carrying passengers, damage but no personal injury | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: driving alone, personal injury or death | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: carrying passengers, personal injury or death | Number of times |

| How many crashes resulted in study member being fined or charged | Number of times |

| Number of times caught for speeding | Number of times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove up to 10 km/h over the limit | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove between 11 & 25 km/h over the limit | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove more than 25 km/h over the limit | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times did not wear a seatbelt (helmet if motorbike) at all | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times forgot seatbelt (helmet if motorbike) for part of the trip | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove when very tired | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times nearly fell asleep or fell asleep when driving | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove when affected by alcohol | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove when affected by marijuana/cannabis/THC | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove when affected by ecstasy (XTC, E, X, MDMA, eccies, etc.) | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times drove when affected by amphetamines (speed, uppers, fast, etc.) | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times talked on hands-free mobile phone when driving | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times talked on handheld mobile phone when driving | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| In last 10 driving trips, how many times used mobile phone function (e.g., received or sent an SMS) while driving | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 times |

| How often make plans to avoid drinking and driving | Always, most of the time, sometimes, rarely, never |

| How often drink-drive after making plans to avoid it | Always, most of the time, sometimes, rarely, never |

| Actions taken to avoid drink-driving | Planned ahead & got someone else to drive, planned ahead & took taxi/public transport, planned ahead & found another way there, didn't drink alcohol, cut down on the amount drunk, counted/spaced drinks, drank low-alcohol beer, drank more water/soft drink, limited money spent on alcohol, left car there & was driven home by another, left car there & got taxi/public transport, left car there & found another way home, used breath-test machine, stayed overnight, slept in car, did nothing |

| In past month, drove when near or over the alcohol limit | No, yes, don't know |

| In past month, how many days drove when near or over the alcohol limit | Number of days |

| In past year, how many times been in contact with police for a driving-related offence | Never, 1-2 times, 3-4 times, 5-6 times, 7-9 times, 10+ times |

| Friends drive when they have had too much to drink | None, a few, most, don't know |

| Boyfriend/girlfriend/partner drives when they have had too much to drink | Not true, somewhat true, definitely true, don't know |

| Question | Response categories |

|---|---|

| Type of licence held by young adult | None, learner, car, and/or motorbike |

| Has ATP young adult bought a car since getting licence | Yes, no |

| Did parent help ATP young adult select the vehicle | Yes, no |

| What should have been the 3 most important factors in choosing car | Size, safety features, power/performance, fuel economy, price, comfort, vehicle type, manufacturer, reliability, special features, style/image/appearance, other |

| How influential parent was in vehicle choice | Very influential, somewhat influential, not very influential, not at all influential |

| What were the 3 most important factors in choosing car | Size, safety features, power/performance, fuel economy, price, comfort, vehicle type, manufacturer, reliability, special features, style/image/appearance, other |

| Has ATP young adult ever had licence cancelled or suspended | Yes, no |

| Young adult's experience of crash/accident when s/he was the driver | Yes, no |

| Number of crashes/accidents when s/he was the driver | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: driving alone, damage but no personal injury | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: carrying passengers, damage but no personal injury | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: driving alone, personal injury or death | Number of times |

| Crash circumstances and result: carrying passengers, personal injury or death | Number of times |

| Did a crash result in ATP young adult being fined or charged | Yes, no, don't know |

| Has ATP young adult been caught for speeding | Yes, no, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he drive up to 10 km/h over the limit | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he drive between 11 & 25 km/h over the limit | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he drive more than 25 km/h over the limit | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he drive when probably affected by alcohol | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he not wear a seatbelt/(helmet if motorbike) | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he drive when very tired | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he drive when probably affected by an illegal drug | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

| In general, how often does s/he use a handheld mobile phone while driving | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, don't know |

1 These are now called Maternal and Child Health Centres.

3. Driving behaviour trends at 23-24 years of age

This chapter provides a description of the driving behaviour of the 23-24 year-olds participating in the ATP study, with a particular focus on their typical driving behaviours, their history of crash involvement and driving-related offences, and their engagement in a range of risky driving behaviours, including drink-driving. This is followed by an examination of trends for:

- young men and women:

- young people living in metropolitan and non-metropolitan localities;

- young people employed in low-, average- and high-status occupations; and

- young people with differing levels of education.

3.1 Total sample trends

Licensing

Young people were asked whether they had ever held a car or motorbike licence. As shown in Table 3, almost all 23-24 year olds (97%) had held a car licence, but only 6% had ever held a motorbike licence. Very few were learner drivers or had never held a licence or permit to drive a car or motorbike.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Has held a car licence | 942 | 96.9 |

| Has held a motorbike licence | 62 | 6.4 |

| Has a learner's permit | 25 | 2.6 |

| Has never held a licence or permit | 27 | 2.7 |

Note: Percentages do not add to 100% as some individuals fit more than one category (e.g., has held both a motorbike and car licence).

The following discussion focuses on all study members except those who had never held a licence or permit (n = 974, 97%).2

Of those who had ever held a car or motorbike licence or permit, the vast majority reported holding a full licence (Table 4). Less than 1% were currently without a licence, and very few currently held a probationary licence or a learner's permit (about 3% in each category).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| No licence | 6 | 0.6 |

| Learner's permit | 31 | 3.2 |

| Probationary licence | 27 | 2.8 |

| Full licence | 910 | 94.0 |

Note: Percentages add to slightly more than 100% as respondents could select more than one response (e.g., holds both a full car licence and a probationary motorbike licence).

There was considerable diversity in the length of time licences had been held, with the average being 71.2 months (SD = 15.5), which equates to almost 6 years. Seven per cent (n = 67) had experienced the cancellation or suspension of their licence at some time.

Time spent driving

Weekday driving during daylight hours was the most common form of driving reported by young people, with the average length of time spent driving at these times being approximately 5 hours per week. Considerably less driving was undertaken at other times, with night-time driving at weekends being the least common type of driving (Table 5).

| Time of week | Time of day | n | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday to Friday | daylight hours | 936 | 4.9 | 5.4 |

| night-time hours | 869 | 2.1 | 3.2 | |

| Saturday and Sunday | daylight hours | 919 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| night-time hours | 863 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

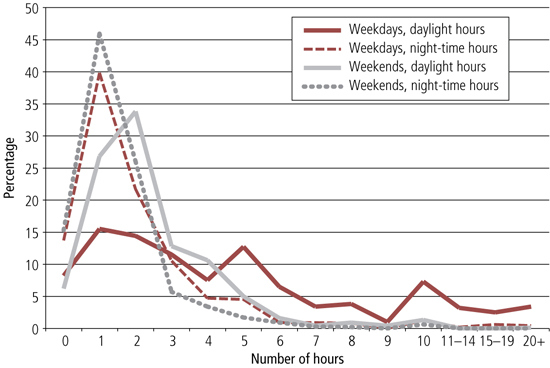

Nevertheless, there was considerable variability in the number of hours young people spent behind the wheel at different times of the day (daylight vs night-time hours) and week (weekdays vs weekends), as displayed in Figure 1. For instance, while half the sample spent three hours or less in weekday daytime driving, about 16% said that they usually drove for ten or more hours at these times. Similarly, while the majority drove for one hour or less at night on weekends (about 60%), a very small number (2%) spent six or more hours driving at this time. The range of driving hours was quite broad, ranging from 0 to 20 hours for night-time weekend driving, and from 0 to 60 hours at all other times.

Figure 1. Number of hours typically spent driving per week, at weekdays and weekends and during daylight and night-time hours, at 23-24 years

Crash involvement

Sixty per cent of young people (n = 576) had been involved in a crash when driving since gaining their licence. Table 6 shows the percentage of respondents who had been involved in differing numbers of crashes during their driving careers.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 crashes | 392 | 40.3 |

| 1 crash | 285 | 29.3 |

| 2 crashes | 182 | 18.7 |

| 3 crashes | 48 | 4.9 |

| 4 or more crashes | 29 | 3.0 |

Note: Percentages do not add to 100% as some individuals who indicated that they had been involved in a crash did not provide information on the number of crashes in which they had been involved.

Close to a third of all drivers had been involved in only one crash, while one in five had been involved in two. Relatively few young drivers (less than 8%) had been involved in more than two crashes over the course of their driving careers, with the highest number reported being six crashes. The average number of crashes reported was 1.0 (SD = 1.1).

Young people were also asked about the circumstances in which the crash(es) had occurred, (e.g., whether or not passengers were present) and about crash outcomes (e.g., whether the crash had resulted in property damage only, or someone being injured or killed).3 About half (48%) of all drivers had been involved in a crash resulting in property damage when driving alone. Property damage crashes when young people were carrying passengers were also quite common, with more than one in five (22%) having been involved in a crash of this type. Very few had been involved in a crash in which someone had been injured or killed, irrespective of whether they had been driving alone (3%) or when passengers were present (less than 1%).

Few 23-24 year olds (n = 26, 3% of all drivers) had been fined or charged as a result of a crash. Most of these drivers (n = 24, 92%) had been fined or charged once. The remaining 8% (n = 2) had been fined or charged twice.

Detection for speeding and police contact for driving-related offences

Table 7 shows the number of times 23-24 year old study members had been detected speeding over their driving careers, according to self-reports.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 times | 403 | 42.2 |

| 1 time | 208 | 21.8 |

| 2 times | 126 | 13.2 |

| 3 times | 101 | 10.6 |

| 4 times | 50 | 5.2 |

| 5 times | 30 | 3.1 |

| 6 or more times | 38 | 3.9 |

While 42% had never been detected speeding, about one in five had been detected once, and over a third had been detected multiple times, with the highest number being 15. The average number of times of being detected speeding among all drivers was 1.5 (SD = 2.3).

Young drivers were also asked how often in the past 12 months they had been in contact with police for a driving-related offence. While the great majority (n = 862, 86%) reported no contact, 12% (n = 122) had been in contact with police for a driving offence on one or two occasions in the past year. Only 1% (n = 13) reported this type of police contact on more than 2 occasions.

Risky driving

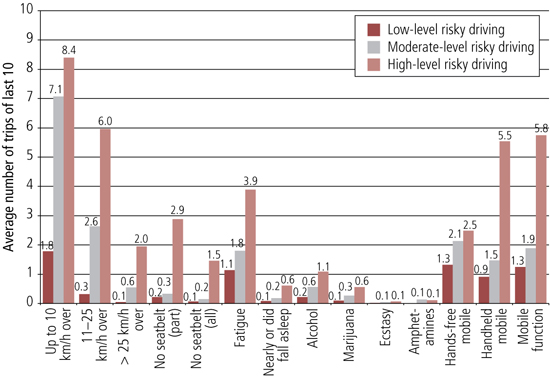

The percentage of 23-24 year olds who had engaged in differing unsafe driving practices during their last ten trips is shown in Table 8. Risky driving behaviours include speeding, driving without a seatbelt (or helmet if on a motorbike), driving when very tired, driving while under the influence of alcohol or illegal drugs, and using a mobile phone while driving. The average number of trips in which this sample of young people had engaged in each type of risky driving is also is shown.

| n | % | Average no. of trips | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speeding | ||||

| Drove up to 10 km/h over the limit | 801 | 83.4 | 3.7 | 3.2 |

| Drove between 11 and 25 km/h over the limit | 430 | 44.8 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

| Drove more than 25 km/h over the limit | 131 | 13.7 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| Seatbelt/helmet use | ||||

| Did not wear a seatbelt/helmet for part of the trip | 130 | 13.5 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Did not wear a seatbelt/helmet at all | 50 | 5.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Fatigue | ||||

| Drove when very tired | 602 | 62.5 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Nearly fell asleep or fell asleep when driving | 104 | 10.8 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Alcohol and other drug use | ||||

| Drove when affected by alcohol | 218 | 22.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| Drove when affected by marijuana | 50 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Drove when affected by ecstasy | 19 | 2.0 | < 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Drove when affected by amphetamines | 22 | 2.3 | < 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Mobile phone use when driving | ||||

| Talked on a hands-free mobile phone | 420 | 43.7 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| Talked on a handheld mobile phone | 526 | 54.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| Used a mobile function (e.g., received or sent an SMS message) | 630 | 65.5 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

The most common type of risky driving was speeding by up to 10 km/h over the speed limit, with more than four out of five young people having done so at least once during their last ten trips. This behaviour had occurred on about a third of the past ten trips. Driving between 11 and 25 km/h over the limit was also quite common, with about 45% exceeding the speed limit by this margin at least once during their past ten trips. Across the sample, the average number of recent trips during which young people had exceeded the speed limit by 11 to 25 km/h was 1.3 (i.e., 13% of trips). Considerably fewer (14%) had exceeded the speed limit by more than 25 km/h. As might be expected, higher levels of speeding were less common than less extreme forms of speeding.

Mobile phone use while driving was also common. Two-thirds had used a mobile phone function (e.g., receiving or sending an SMS message) during at least one of their past ten driving trips, while over half had spoken on a handheld mobile phone on at least one trip. These behaviours occurred on about 15% of driving trips. More than four in ten young people (44%) had also spoken on a hands-free mobile phone while driving. On average, talking on a hands-free mobile phone occurred on about 16% of the last 10 trips.

Another common risky driving behaviour was driving when very tired, with close to two-thirds reporting this had occurred at least once in the past ten trips. On average, young people reported driving when tired on about 15% of their most recent trips. About one in ten 23-24 year olds had been so tired that they had fallen asleep or come close to falling asleep while driving. However, such instances were very infrequent, occurring on 2% of trips.

More than one in five 23-24 year olds had driven when affected by alcohol on at least one of their ten most recent trips. However, very few had driven while under the influence of marijuana (5%), ecstasy (2%) or amphetamines (2%). The average number of trips on which young people drove when affected by alcohol or other drugs was very low (ranging from less than 1% to 4% of trips).

Only 14% reported failing to wear a seatbelt or helmet for part of a trip, and very few (5%) reported failing to wear a seatbelt or helmet altogether. Such behaviours also tended to occur very infrequently (on less than 5% of trips).

Drink-driving

Occurrence of drink-driving

Young people were asked whether they had driven when they were near or over the legal alcohol limit during the past month, and on how many days this had occurred.

Twenty per cent of all drivers (n = 193) had driven when near or over the limit in the past month. For 13%, this had occurred on one day, for 4%, on two, while 3% had engaged in this behaviour on three or more days in the past month (Table 9). The highest number of days a young person had driven when near or over the legal limit was 15.

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 days | 780 | 80.0 |

| 1 day | 126 | 13.0 |

| 2 days | 42 | 4.3 |

| 3 days | 16 | 1.6 |

| 4 or more days | 9 | 0.9 |

Drink-driving behaviours of friends and romantic partners

Questions were also included about the drink-driving tendencies of friends and romantic partners (if in a romantic relationship).

Trends are shown in Table 10 and Table 11. While the majority reported that none of their friends engaged in drink-driving, a sizeable minority (39%) reported that they had a few friends who did. Very few (less than 2%) reported that most of their friends were drink-drivers.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| None | 563 | 58.3 |

| A few | 374 | 38.7 |

| Most | 16 | 1.7 |

| Don't know | 13 | 1.3 |

Young drivers were asked a similar question about partners (boyfriend, girlfriend, or spouse). Close to two-thirds (65%) were in a romantic relationship, and of this group, very few thought their partner drove after having too much to drink, although this was "somewhat true" for 12% (Table 11).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Not true | 551 | 86.1 |

| Somewhat true | 77 | 12.0 |

| Definitely true | 7 | 1.1 |

| Don't know | 5 | 0.8 |

Actions taken to avoid drink-driving

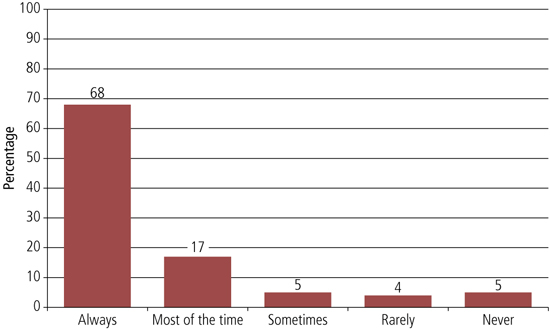

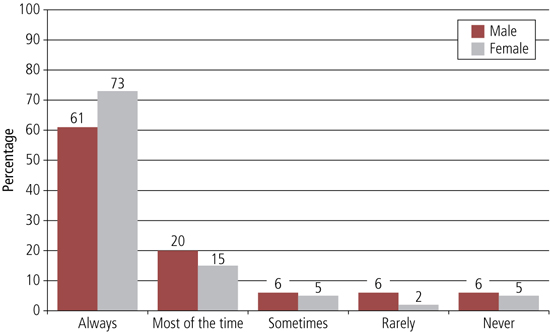

Young people were asked how often they made plans to avoid drinking and driving. More than two-thirds "always" planned ahead to avoid drink-driving, while a further 17% made such plans "most of the time" (Figure 2). However, almost one in ten 23-24 year-olds (9%) "rarely" or "never" made plans to avoid drink-driving.

Figure 2. Frequency of making plans to avoid drink-driving, at 23-24 years

Those who made plans to avoid drink-driving (all except those who responded "never" in Figure 2) were then asked how often they ended up drink-driving anyway (Figure 3). Approximately 1% reported drink-driving anyway on a frequent basis (e.g., "most of the time" or "always"). The vast majority (76%) never engaged in drink-driving. However, almost one-quarter had gone on to drink and drive on rare occasions.

Figure 3. Frequency of drink-driving after making plans to avoid it, at 23-24 years

All 23-24 year old study members were also asked whether they had used various strategies to avoid drink-driving within the past month. Table 12 displays the number and percentage of young people who reported having taken each action to avoid drink-driving (listed in order from most common to least common).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Planned ahead and got someone else to drive there | 665 | 68.4 |

| Planned ahead and took a taxi or public transport there | 571 | 58.7 |

| Didn't drink alcohol | 513 | 52.8 |

| Cut down the amount I drank | 376 | 38.7 |

| Planned ahead and found another way to get there | 292 | 29.2 |

| Stayed overnight | 281 | 28.9 |

| Counted or spaced my drinks | 256 | 26.3 |

| Drank more water or soft drink | 248 | 25.5 |

| Left my car there and arranged to be driven by someone else | 195 | 20.1 |

| Left my car there and used a taxi or public transport | 188 | 19.3 |

| Left my car there and found another way to get home | 125 | 12.9 |

| Drank low-alcohol beer | 103 | 10.6 |

| Limited the money I spent on alcohol | 78 | 8.0 |

| Used a breath-testing machine to check my level | 39 | 4.0 |

| Did nothing | 37 | 3.8 |

| Slept in my car | 18 | 1.9 |

| Never drink alcohol (teetotaller)a | 15 | 1.5 |

Note: Percentages do not add to 100% as respondents were able to select multiple options. a While this was not one of the response options listed for this question, a number of individuals (n = 15) indicated that they did not need to use any of the listed strategies, as they did not drink alcohol.

Most 23-24 year olds had taken at least one action to avoid drink-driving within the past month, with only 4% reporting that they had done nothing at all. The most common actions taken were to plan ahead and arrange alternative transport to one's destination, or to alter drinking habits when at a location where alcohol was served. For instance, over two-thirds had arranged for someone to drive them to their destination to avoid drink-driving, while close to 60% had taken a taxi or public transport to their destination, and about 30% found an alternative way to get there.

Furthermore, more than half had abstained from drinking alcohol within the past month to avoid drink-driving, 40% had limited the amount of alcohol they had consumed, and about a quarter had counted or spaced their drinks, or consumed more water or soft drink. Staying overnight was another common strategy (29%). Between 13% and 20% had left their car behind and found alternative transport home, and about one in ten had consumed low-alcohol beer. Only 8% had limited the amount spent on alcohol and very few (less than 5%) had tested their alcohol level using a breath-testing machine or slept in a car.

Almost all young people (97%) had obtained their car licence by 23-24 years of age. The average length of time that licences had been held was 6 years. About 3% had had their licence cancelled or suspended since gaining their licence.

Turning to patterns of driving, most driving took place during the week, in daytime hours. The average time spent driving each week at such times was five hours. Considerably less driving was undertaken at night or at weekends, with night-time weekend driving being least common (an average of about 1½ hours per week).

Sixty per cent of the young people had been involved in a crash while driving a car or motorcycle since gaining their licence. Crashes resulting in property damage were the most common. Almost half of all drivers had experienced a crash of this type when driving alone (48%), and about one in five when carrying passengers (22%). Crashes resulting in injury or death were very uncommon.

More than half had been detected speeding during their driving careers, and about one in seven had come into police contact for a driving-related offence in the past 12 months.

Risky driving was common. Over 80% of 23-24 year-olds had exceeded the speed limit by up to 10 km/h on at least one of their ten most recent driving trips, and close to half by 11-25 km/h on at least one occasion. About two-thirds had driven when very tired or used a mobile phone function (such as receiving or sending an SMS) when driving, and around half had talked on a handheld (55%) or hands-free mobile (44%) when driving. Approximately one in five had driven when affected by alcohol on at least one of their ten most recent trips. Other types of risky driving, such as driving without a seatbelt (or helmet if on a motorbike) or driving when affected by illegal drugs, were less common and ranged in incidence from 2% to 14%.

Looking at drink-driving, one in five 23-24 year-olds had driven when near or over the legal limit during the previous month. Over 40% had friends who engaged in drink-driving, and about one in eight had a partner who had driven when over the legal limit. Two-thirds of young people reported that they "always" made plans to avoid drink-driving, and the majority who made plans to avoid drink-driving, "never" engaged in this behaviour. The most common strategies young people used to avoid drink-driving were to plan ahead and arrange alternative transport to their destination (e.g., getting someone else to drive, taking a taxi or public transport) or to alter their drinking habits when at a venue at which alcohol was served (e.g., not drinking, reducing the amount of alcohol consumed). Staying overnight was another common strategy used to avoid drink-driving. Very few (less than 5%) reported testing their alcohol level with a breath-testing machine or sleeping in their car in order to avoid drink-driving.

3.2 Gender differences

The young men (n = 390, 39%) and young women (n = 610, 61%) in this study significantly differed on many aspects of driving behaviour.

Licensing

Although there were no gender differences in the percentage who held a car licence, perhaps unsurprisingly, more males (13%) than females (2%) had obtained a motorbike licence.4 Males were also significantly more likely than females to have had their car or motorbike licence cancelled or suspended (13% compared with 3%, respectively).5

However, young men and women did not significantly differ in the types of licences currently held (no licence, learner's permit, probationary licence, or full licence) or the length of time they had held their licences.

Time spent driving

Young men tended to spend slightly more time behind the wheel than young women: a total of 11.5 hours (SD = 10.1) driving over the course of a week, of which 5.4 hours (SD = 6.0) was spent in weekday daytime driving. By comparison, females spent on average 10.0 hours (SD = 8.0) driving each week, and 4.6 hours (SD = 5.0) during weekday daytime hours. However, while there was a trend for differences, this did not reach the adjusted significance level.6

Males and females did not significantly differ in the amount of time spent driving at night (both on weekdays and weekends) or during daytime hours on weekends.

Crash involvement

No significant gender differences were found on any aspects of crash involvement (percentage involved in a crash when driving, number of crashes, crash characteristics, number fined/charged as a result of a crash).

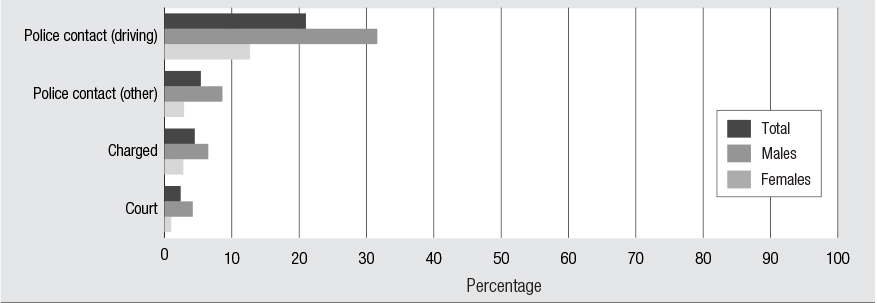

Detection for speeding and police contact for driving-related offences

Males had been apprehended for driving-related offences significantly more often than females. Thus, males had been detected speeding 2.1 times (SD = 3.0) in their driving career on average, while females had been detected 1.2 times on average (SD = 1.6).7 Additionally, significantly more males (21%) than females (9%) had been in contact with the police for a driving-related offence in the past 12 months.8

Risky driving

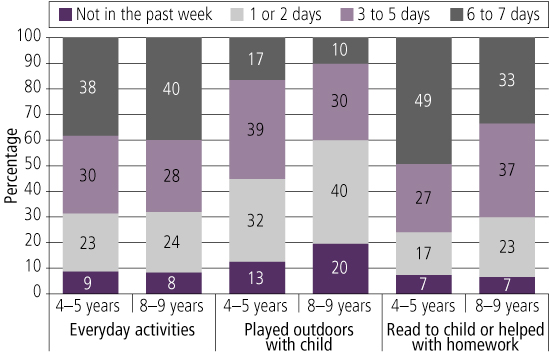

Gender differences were also evident on risky driving (Figure 4). Males were more likely than females to have engaged in moderate- and high-level speeding (11-25 km/h and > 25 km/h over the limit) at least once during their ten most recent driving trips and to have driven when affected by alcohol.9 There were also trends for more young men than young women to have driven up to 10 km/h over the limit and to have not worn a seatbelt for part of the trip.10

Figure 4. Engagement in risky driving during previous ten trips, males and females, at 23-24 years

Females, on the other hand, were more likely to have driven when very tired on at least one of their ten most recent trips.11 There was also a trend for them to have more often used a mobile phone function while driving.12

Drink-driving

Significantly more males than females reported drink-driving during the past month.13 Close to a third of young men (31%) had driven when over or near the limit, compared with 14% of young women.

While young men and young women had driven when over the limit on relatively few days in the past month, males had done so more often than females (males: M = 0.6 days, SD = 1.3; females: M = 0.2 days, SD = 0.5). 14

Significantly more males (51%) than females (34%) had friends who were drink-drivers, but females were significantly more likely to have a partner who drove after drinking (18% vs 6%).15

Gender differences were also found in the frequency with which young men and women made plans to avoid drink-driving (Figure 5).16

Figure 5. Frequency of plans being made to avoid drink-driving, males and females, at 23-24 years

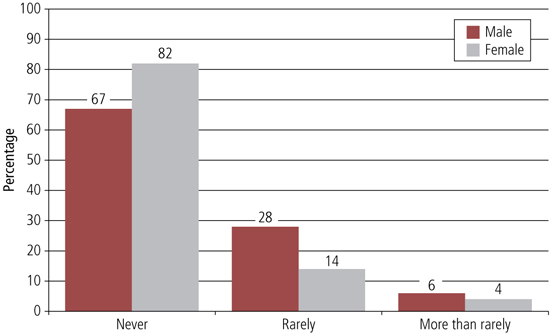

Of the young people who made plans to avoid drink-driving (Figure 6), young men were more likely to drink-drive on rare occasions (28% vs 14%).17 In contrast, a higher percentage of young women "never" engaged in drink-driving after making such plans (82% vs 67%).

Figure 6. Frequency of engaging in drink-driving after making plans to avoid it, males and females, at 23-24 years

Differences were also found in the types of strategies that young men and women used to avoid drink-driving (Figure 7). Young men were more likely than young women to have: (a) reduced the amount of alcohol they had consumed, (b) counted or spaced their drinks, and (c) consumed low-alcohol beer.18 There was also a trend for them to leave their car behind and be driven home by others, or to stay overnight. Young women were more likely to report that they had abstained from drinking alcohol altogether as a strategy to avoid drink-driving.19

Figure 7. Strategies used to avoid drink-driving, males and females, at 23-24 years

Young men and women significantly differed on many aspects of driving behaviour. Unsurprisingly, more young men than women had held a motorcycle licence at some stage during their driving careers. Young men were also more likely to have had their car or motorbike licence cancelled or suspended.

There were no significant gender differences in the occurrence, circumstances or outcomes of crashes. However, young men were more likely to have been apprehended for a driving-related offence than young women. Additionally, young men were more likely to engage in several unsafe driving practices than young women (moderate- and high-level speeding, driving when affected by alcohol). Females, on the other hand, were more likely to have driven when fatigued.

Consistent with these findings, a higher percentage of young men than young women had driven when near or over the legal alcohol limit during the previous month, and had friends who engaged in drink-driving. Females, on the other hand, were more likely to have a romantic partner who drove after drinking.

While most young people reported regularly making plans to avoid drink-driving, young men were more likely than young women to be among the small group that rarely did so. Young men were also more likely than young women to report that on rare occasions they had ended up drink-driving despite making plans to avoid doing so.

Significant differences were also evident in the strategies that young men and women used to avoid drink-driving. Whereas young women more often abstained from drinking altogether, young men were more likely to alter their drinking habits (e.g., drink less, count or space their drinks, or drink low-alcohol beer).

3.3 Metropolitan and non-metropolitan differences

Young people's residence locality was classified into "met" and "ex-met" categories (capital city statistical division vs rest of state) using Australian Bureau of Statistics criteria. A number of significant differences were found in the driving experiences and behaviours of young people living in metropolitan (n = 682, 68% of sample) and non-metropolitan areas (n = 312, 31%).

Licensing

Young people living in metropolitan and non-metropolitan localities did not significantly differ in the types and lengths of time licences had been held, or rates of suspension or cancellation of a licence.

Time spent driving

While there were trends for young people living in metropolitan areas to spend a little longer on the road on weekdays (both during daytime and night-time hours) and more hours driving in total, these did not reach the adjusted significance level.20 There were no differences in the amount of time spent driving on weekends (during daytime and night-time hours).

Crash involvement

More 23-24 year old drivers living in metropolitan areas had been involved in a crash when driving than those living in non-metropolitan areas (63% vs 52%).21 Metropolitan drivers had also been involved in more crashes on average (1.08 vs 0.79 crashes) and more crashes that resulted in property damage when driving alone (0.86 vs 0.55 crashes), while there was a trend for them to have been involved in these type of crashes when they were also carrying passengers.22 However, there were no significant differences on rates of crashes that resulted in injury or death, or the proportion who had been fined or charged as a result of a crash.

Detection for speeding and police contact for driving-related offences

There were no differences between young people from metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas on the number of times they had been detected speeding, or had police contact for driving-related offences.

Risky driving

Several differences were found between metropolitan and non-metropolitan drivers in their engagement in risky driving. A higher percentage of metropolitan drivers had talked on a hands-free mobile while driving on at least one of their ten most recent trips (49% vs 31%), whereas non-metropolitan drivers were more likely to have not worn a seatbelt or helmet for a part of a recent trip (18% vs 11%). There was also a similar trend for differences on failure to wear a seatbelt for the whole of a trip.23

Drink-driving

Similar numbers of 23-24 year olds from metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas had engaged in drink-driving at least once in the past month. There was a trend for young people from non-metropolitan areas to drink-drive on more days than their metropolitan counterparts (non-metropolitan: M = 0.5 days, SD = 1.2; metropolitan: M = 0.3 days, SD = 0.7), but this did not reach the adjusted significance level.24 There was also a trend for more young drivers living in non-metropolitan areas to have friends who engaged in drink-driving (46% vs 38%), but again, this did not reach the adjusted significance level.25 Metropolitan and non-metropolitan drivers did not significantly differ in their likelihood of having a partner who drove after having too much to drink.

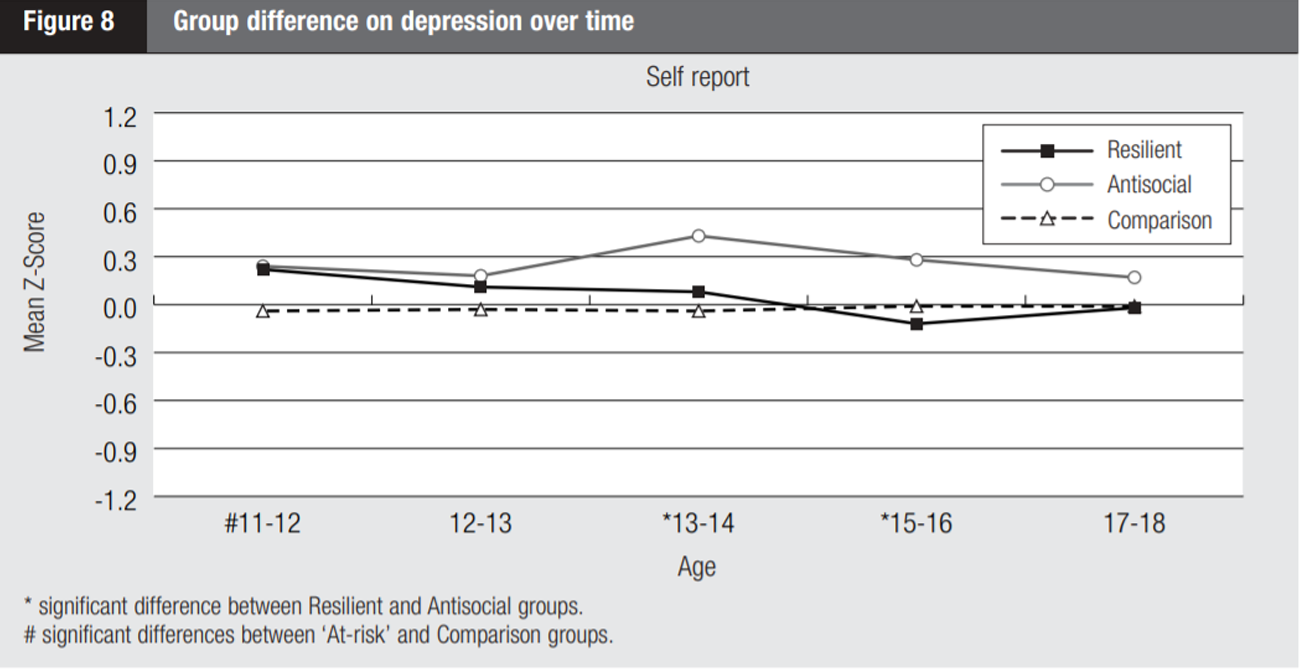

No significant differences were found between metropolitan and non-metropolitan young drivers on making plans to avoid drink-driving, or the frequency of drink-driving after making plans to avoid doing so. However, a number of significant differences were found in the types of strategies used to avoid drink-driving. As shown in Figure 8, non-metropolitan drivers were more likely to report that, to avoid drink-driving, they had left their car behind and (a) been driven home, (b) taken a taxi or public transport, and/or (c) found another way home.26 In contrast, metropolitan drivers were more likely to report that they had (a) reduced the amount of alcohol they had consumed, (b) counted or spaced their drinks, or (c) consumed more water or soft drink.27 Thus, young people from metropolitan areas were more likely to change their drinking habits to avoid drink-driving, while their counterparts from non-metropolitan areas were more likely to leave their car behind and arrange another way to get home.

Figure 8. Strategies used to avoid drink-driving, metropolitan and non-metropolitan young drivers, at 23-24 years

Young people from metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas significantly differed on a number of aspects of their driving behaviour.

Those from metropolitan areas had more often been involved in a crash, and had experienced more crashes on average than non-metropolitan 23-24 year olds (particularly those resulting in property damage when driving alone).

The two groups did not significantly differ in their licensing status or the amount of contact they had with police for driving-related offences. However, they did differ on several aspects of risky driving. Rates of hands-free mobile phone use when driving were higher among young people residing in metropolitan areas, while non-metropolitan drivers were more likely to report that they had not worn a seatbelt (or helmet) when driving for part of a trip.

While there were no significant differences on rates of drink-driving, differences were found in the strategies the two groups used to avoid drink-driving. While non-metropolitan drivers were more likely to leave their car behind and find an alternative way home (e.g., be driven home, take a taxi or public transport, find another way home), metropolitan drivers were more likely to alter their drinking habits (e.g., drink less, count or space drinks, or drink more water or soft drink).

3.4 Occupational status differences

The ANU-4 Occupation Status scale (Jones & McMillan, 2001) was used to rank young people's occupations in order of relative prestige. The scale assigns a score, ranging from 0 to 100, to an individual's occupation. In devising the ranking, the ANU-4 takes into account the occupation's ranking on the Australian Bureau of Statistics' Classification of Occupations, and relationships between the occupation and Australian population educational attainment and income levels.

Young people were divided into three groups on the basis of their occupation status. These were:

- a low occupational status group (n = 220, the lowest 25% of the ATP sample in terms of occupational status);

- an average occupational status group (n = 449, the middle 51% of the ATP sample in terms of the status of their occupation); and

- a high occupational status group (n = 212, the highest 24% of the ATP sample in terms of their occupational status).

Licensing

Young people employed in low-, average- and high-status occupations did not significantly differ in the types and lengths of time licences had been held, or whether a licence had been cancelled or suspended.

Time spent driving

The three occupational status groups did not significantly differ in the amount of time spent driving each week (in total, during weekdays and weekends, or during daytime or night-time hours).

Crash involvement

Young people employed in low-, average- and high-status occupations did not significantly differ in their likelihood of involvement in a crash, the number and types of crashes experienced, or their receipt of a fine or charge as a result of a crash.

Detection for speeding and police contact for driving-related offences

No significant differences were found between the three occupational status groups in the number of times they had been detected speeding, or their level of police contact for driving-related offences.

Risky driving

A similar proportion of young people employed in low-, average- and high-status occupations had engaged in each type of risky driving behaviour.

Drink-driving

Young drivers in the low, average and high occupational status groups did not significantly differ in their likelihood of engaging in drink-driving, or the frequency with which they had driven when near or over the alcohol limit during the past month.

There were no significant differences in the drink-driving behaviour of their friends and romantic partners.

There were also no significant differences in how often young people in the three groups made plans to avoid drink-driving. However, those in the high occupational status group were less likely to engage in drink-driving after making such plans than other drivers (Figure 9).28

Figure 9. Frequency of drink-driving after making plans to avoid it, low-, average- and high-status occupations, at 23-24 years

[[{"fid":"2846","view_mode":"full","fields":{"format":"full","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Figure 9 graph of frequency of drink-driving after making plans to avoid it, by occupation, described in text\"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":""},"type":"media","attributes":{"alt":"Figure 9 graph of frequency of drink-driving after making plans to avoid it, by occupation, described in text"","class":"media-element file-full"}}]]

There were trends for differences in the types of strategies used to avoid drink-driving. For example, those in the low occupational status group were more likely to limit the amount of money spent on alcohol (low: 12%; average: 7%; high: 7%), and less likely to plan ahead and take a taxi or public transport to their destination (low: 52%; average: 63%; high: 64%), but these did not reach the adjusted significance level.29

Overall, young people employed in low-, average- and high-status occupations did not differ in their driving behaviour. Thus, no significant differences were found in their licensing status, driving patterns, level of crash involvement or rate of apprehension for driving-related offences. The only difference found was on how often these groups engaged in drink-driving after making plans to avoid doing so (this was less likely to have occurred among those in high-status occupations).

3.5 Education level differences

Young people were classified into groups on the basis of the highest level of education they had completed. These were:

- secondary (n = 296, 30%): those who had completed some or all of their secondary education, but not engaged in any post-secondary education;

- other post-secondary (n = 258, 26%): those who had completed some form of post-secondary education other than a university degree (e.g., a TAFE diploma/certificate, an apprenticeship); and

- university (n = 440, 44%): those who had completed a university degree.

Comparisons of these groups revealed a number of significant differences.

Licensing

Some significant differences in the licensing status of the three educational attainment groups were found. As shown in Figure 10, fewer of those with secondary education held a driver's licence (90%) and more held a learner's permit (6%) than those in the other post-secondary group (98% of whom held a driver's licence and 1% a learner's permit).30

Figure 10. Type of licence held by secondary, other post-secondary and university groups, at 23-24 years

Young people with a university qualification were less likely to have had their licence cancelled or suspended than those in the other post-secondary group (secondary: 9%; other post-secondary: 10%; university: 3%).31

Time spent driving

The group who had completed other post-secondary education spent close to 12 hours a week driving on average (M = 11.8, SD = 9.9), whereas those in the secondary education group spent about ten-and-a-half hours driving (M = 10.4, SD = 8.7), and those with a university degree, almost 10 hours per week behind the wheel (M = 9.9, SD = 8.4). While this represents a trend for differences, these did not reach the adjusted significance level.32 The three educational attainment groups did not significantly differ in the amount of time they spent driving at different times of the day (daytime, night-time) or week (weekdays, weekends).

Crash involvement

The three groups did not significantly differ in whether or not they had been involved in a crash, the total number of crashes experienced, or the type of property crashes experienced. However, there was a trend for those in the other post-secondary group to have been involved in more injury crashes when driving alone (M = 0.09, SD = 0.4) than those in the secondary (M = 0.03, SD = 0.2) and university (M = 0.03, SD = 0.2) groups (but note that rates of these types of crash were very low overall).33

Young people with a secondary education had more often been fined or charged as a result of a crash than those with a university degree (secondary: M = 0.07, SD = 0.3; other post-secondary: M = 0.03, SD = 0.2; university: M = 0.01; SD = 0.1), although again it should be noted that this very rarely occurred in the ATP sample.34

Detection for speeding and police contact for driving-related offences

Young people with a university degree had been detected speeding on fewer occasions (M = 1.2, SD = 1.6) than those with secondary (M = 1.7, SD = 2.1) and other post-secondary education (M = 1.8, SD = 3.2).35

While those with a university degree were somewhat less likely to have been in contact with police for a driving-related offence than other drivers (11% vs 14% of the secondary and 18% of the other post-secondary groups), the differences found did not reach the adjusted significance level.36

Risky driving

The three educational attainment groups did not significantly differ on their engagement in different risky driving behaviours, although there were some trends for differences (e.g., those with a university degree had less often been involved in moderate-level speeding (11-25 km/h over) or driven without a seatbelt or helmet for all or part of a recent driving trip).37

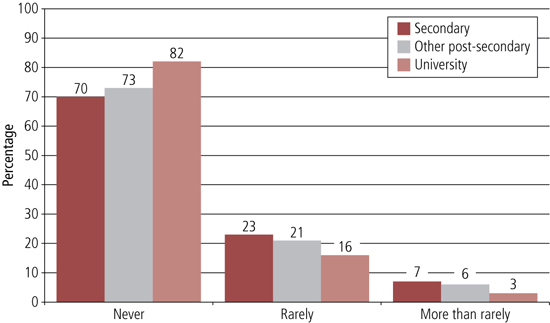

Drink-driving

There were no differences between the secondary, other post-secondary and university groups in the proportion of young people who had engaged in drink-driving, or the number of days on which drink-driving had occurred.

Young people with a university degree were significantly less likely than those with a secondary education to have friends who engaged in drink-driving (secondary: 48%; other post-secondary: 43%; university: 35%).38 However, the three groups did not significantly differ on the proportion whose partners were drink-drivers.

There were also no differences in the frequency with which the three groups made plans to avoid drink-driving. However, of the subset of young people who made plans to avoid drink-driving, fewer of the university group ended up drink-driving anyway (Figure 11).39

Figure 11. Frequency of drink-driving after making plans to avoid it, secondary, other post-secondary and university groups, at 23-24 years

Several significant differences were found in the strategies that young people with differing levels of education used to avoid drink-driving (Figure 12). Those in the other post-secondary group were more likely to have abstained from drinking,40 while young people with a university degree were significantly more likely than those in the secondary group to have planned ahead and been driven to their destination or taken a taxi or public transport, as a strategy to avoid drink-driving.41 Some other trends were also noted (e.g., those with a secondary education were more likely than those with a university degree to use a breath-testing machine or sleep in their car,42 and the other post-secondary group were more likely to drink water or soft drink than the secondary group).

Figure 12. Actions taken to avoid drink-driving, secondary, other post-secondary and university groups, at 23-24 years

Young people with differing levels of education significantly differed in several aspects of their driving experiences and behaviours. For instance, 23-24 year-olds who had completed some or all of their secondary education but had no post-secondary education were more likely to hold a learner's permit, and less likely to hold a car licence than their counterparts with a university or other post-secondary qualification. Those with a university degree were less likely to have had their licence cancelled or suspended than those with another type of post-secondary education qualification.

No differences were evident on typical driving patterns and crash involvement. However, those with only secondary education were more likely to have been fined or charged as a result of involvement in a crash, although this was very rare overall.

Turning now to apprehension for driving-related offences, young people with a university degree had been detected speeding on fewer occasions.

Young people with a university degree were also less likely to have friends who were drink-drivers, and were less likely themselves to drink-drive after making plans to avoid doing so.

The three educational attainment groups differed somewhat in the strategies they used to avoid drink-driving. Those in the other post-secondary group were more likely to abstain from drinking, while young people in the university group were more likely to plan ahead and arrange alternative transport to their destination (e.g., be driven there, or take a taxi or public transport).

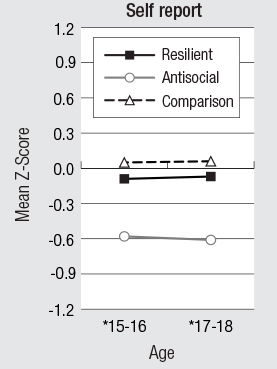

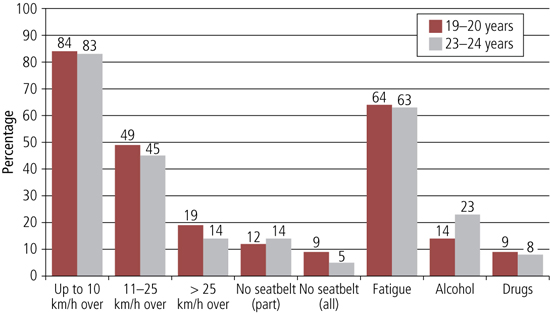

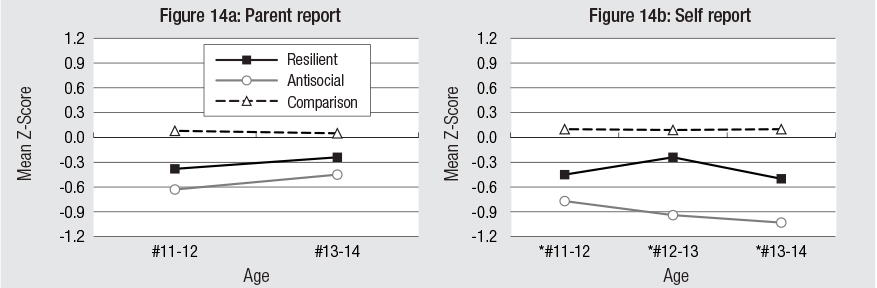

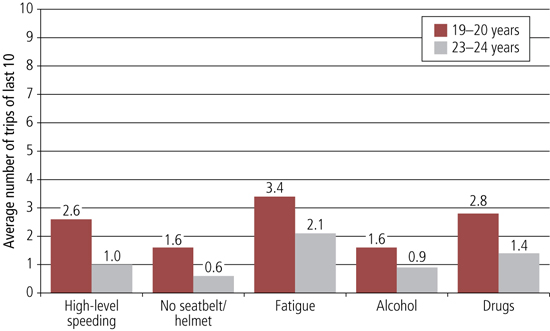

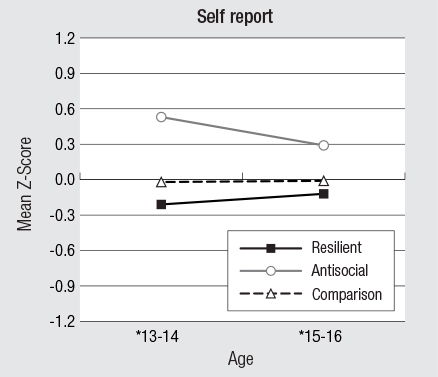

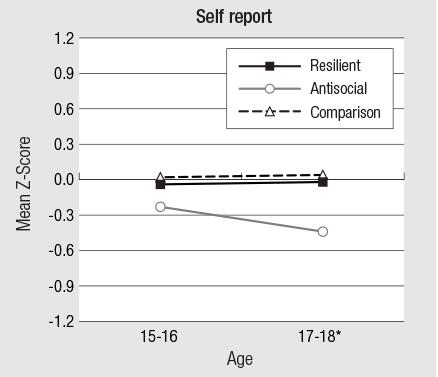

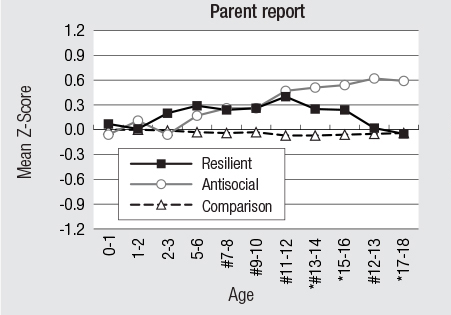

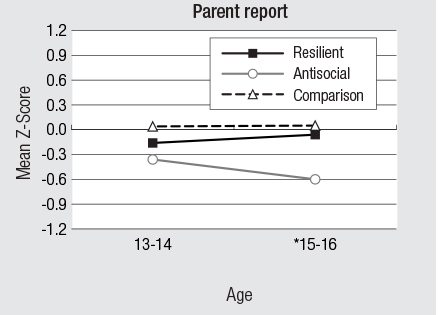

2 Due to a small amount of missing data, the n varies very slightly across the items.>