Families, life events and family service delivery

A literature review

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Download Research report

Overview

This report reviews the literature on life events experienced by families and ways in which they prepare for and/or deal with them.

It covers factors or triggers that lead families to navigate successfully or unsuccessfully through life events, and then addresses the ways in which such events affect families who have been functioning well and those who were already struggling prior to the event occurring.

Finally, the report provides an assessment of service delivery models that aim to support those negotiating a range of life events.

Key messages

-

In considering life events, a focus on family functioning and family processes is more useful than a focus on family structure.

-

Well functioning family processes are likely to ameliorate the negative impacts of life events, while poor family processes are likely to exacerbate these impact.

-

Individual, community and societal supports promote good family processes when life events occur.

-

Social inclusion is a positive mediating and moderating influence on the outcome of life events.

-

Vulnerability and resilience are variable in nature; that is, both these states vary between persons and across the lifespan.

Executive summary

The Australian Institute of Family Studies (the Institute; AIFS) has completed this literature review on life events at the request of the Portfolio Department of Human Services (the Department; DHS).

Life events or transitions are understood to be circumstances that have an unsettling element for individuals (and from a systemic perspective, for family members also). Life events or transitions, even when pursued and ultimately beneficial, usually require adjustment on one or more fronts and relinquishment of at least some areas of familiarity. Examples of life events include: births, establishing a new relationship, moving house, entering the education system, starting a new job, experiencing a physical or mental illness, deaths, and so on.

The review broadly covers four topics:

- life events experienced by families and ways in which families prepare for and/or deal with them;

- causal factors or triggers that lead families to navigate through life events successfully or unsuccessfully;

- the ways in which life events affect those families who have been functioning well and those who were already struggling prior to experiencing the event; and

- an assessment of service delivery models to support those negotiating a range of life events.

The content and structure of the review has been shaped by the available literature. The following ideas underpin the review:

- life events can have both positive and negative effects that can be fleeting or span the rest of life and even across generations;

- some life events are expected while others are quite unpredictable and, whether expected or not, they have the potential to change lives substantially;

- life events tend to involve loss of some kind, including those that are ultimately beneficial;

- the capabilities of individuals to manage the events that occur in life vary;

- some events occur at the individual level, while other events are shared and therefore typically have wider effects, especially in times of natural disaster;

- managing the effects of life events is not just a matter of personal vulnerability or resilience, but is also affected by the supports available in one's family, friendship group, neighbourhood, community and the wider society;

- understanding the origins, effects and longer term influences of life events is of fundamental relevance to the framing of policies and the development of programs to provide the supports that can be deployed to assist people to negotiate them and to enhance the chances of positive, as opposed to negative, outcomes in the short-, medium- and/or longer term; and

- the potential strength of the life events concept lies in focusing attention on "What is happening?" rather than exclusively on personal problems, pathology or other characteristics, thereby shifting the focus from "What is wrong?" to "What does this family, faced with this particular event, need in order to effect a positive transition at this particular stage of its development?"

Organised in five chapters, the review begins with an overview of contemporary Australian families, and considers the changing patterns of partnership formation, parenting, separation and divorce. The social context of family functioning is highlighted, as are some of the barriers to partnering, including when:

- opportunities to form relationships are limited, such as in early adulthood (as young people may be pre-occupied with education and/or establishing a career);

- the emotional toll of a previous relationship breakdown limits the capacity to embark on another;

- responsibility for children impedes re-partnering; and

- social, emotional and/or behavioural characteristics make establishing and sustaining a relationship difficult.

The chapter also explores factors that lead to the fragility of relationships, including young age, pregnancy, low income, non-traditional family values, and mental illness. The chapter ends with a brief consideration of traditional and emerging family forms. As such, the discussion sets the scene for consideration of the family contexts within which life events occur and have their consequences, for good or ill.

The next chapter focuses on the concept of life events and the life transitions that give rise to circumstances that may be unsettling for individuals. The effects of life events may flow to their family, neighbourhood and wider community. Whether expected or unexpected, or positive or negative, the subjective experiences will be unique. In addition, how an event or transition is experienced and understood will have a considerable effect on one's sense of wellbeing.

The various models of understanding that have grown out of the life events research literature share a focus on "stress". Constructions of health and illness are also linked to the idea of successful life transitions - especially the idea that health is more than a mere absence of illness. These constructions include a focus on positive psychological health and one's overall sense of wellbeing and life satisfaction, purpose and meaning, along with a capacity for growth, mastery, competence, positive interpersonal relationships, and a sense of belonging to the community. Stressful life events are also more likely to be encountered by some people than others. Social address markedly influences the load of risk factors, and those from disadvantaged households generally have both a much higher average number of risks and an increased likelihood of experiencing negative life events. In turn, negative life events can lead to social exclusion and limit opportunity.

The third chapter focuses on developmental and family influences on life events. As the backdrop for exploring individual responses to loss, it focuses first on individual identity development and a range of available responses that individuals can have to life events. The influence of families is framed in terms of the ways in which changes in social norms related to marriage, childbearing, educational attainment, and women's employment have reshaped families. These make residential family membership much less continuous over the life course, which in turn affects the continuity of available supports. The increasing complexity of family living arrangements makes a life course perspective essential for understanding families and their responses to life events.

The fourth chapter opens with a consideration of life event scales and observes that the majority of events - especially those that attract high "life change units" (LCUs) - involve the experience of loss. For events such as the death of a spouse or loved one, divorce, or foreclosure on a mortgage, the nature of the loss is instantly recognisable. Other categories of events may not be constructed in the first instance as a loss; for example, the consequences of a major illness or injury to a close family member might not be automatically seen in these terms. While most categories in life event scales have largely negative aspects to them, some (such as reconciliation or changing residency) are far less likely to be in this category. Events in both categories, however, represent significant changes in the life of an individual and his or her family, and are therefore likely to be associated with varying periods of vulnerability.

The factors that distinguish successful from unsuccessful navigation of these events include the availability of external resources (such as income and adequate services) and internal resources (such as robust and committed family relationships and a realistically optimistic outlook). Of course, these factors interact. A family with a realistically optimistic outlook is likely to seek appropriate support and services in anticipation of an event (such as the birth of a baby) or in response to an unanticipated event (such as being involved in a car accident). A family that is already stressed by financial issues or by interpersonal conflict is less likely to have planned adequately for the arrival of a baby and more likely to have difficulties responding effectively to a major unexpected event such as a car accident.

The factors that maximise the chances that a family will successfully navigate adverse events are essentially those related to family resilience; that is, their belief systems, organisational patterns, and communication/problem-solving capacities, among others. Strong families are able to adapt to changing circumstances and have a positive attitude towards the challenges of family life. They deal with these challenges by communicating effectively (talking things through with each other and supporting each other in times of need), seeking outside support (when it is beyond the family's capability to deal with the situation), and "pulling together" (to form a united front and find solutions). On the reverse side, the areas that sap the strength of families and contribute to difficulties in negotiating life events continue to be those such as family violence, child abuse, mental health issues and substance misuse.

The chapter ends with consideration of two life events that affect the vast majority of families: the transition to parenthood and the transition to school. The examples show that, once an event is teased out, a considerable number of issues arise that are capable of enhancing or challenging the ways in which a family copes.

The fifth chapter provides a brief overview of issues for service delivery, observing at the outset that most "family" services, whether offered face-to-face or via an increasingly sophisticated range of information systems, are delivered to individuals. That said, the effect of life events on individuals can also have a profound influence on family dynamics. In other words, effects are always reciprocal - whether these concern, for example, a couple during the transition to parenthood, or an entire family and its support networks when one member becomes seriously ill. Dealing with more than one individual - such as a couple, family or extended family - presents a broad range of logistical and training challenges. Service systems are increasingly adopting a "no wrong door" approach, whereby clients are not the ones to shoulder the burden of having to match their need with the "correct" service. Such a shift requires intensive and ongoing practitioner training, as well as paying close attention to the risk of worker "burnout" in the face of the greater complexity that such a system brings. Information systems have the potential to provide access to significantly increased resources for both service providers and their clients.

The final chapter presents concluding remarks.

Review findings

The review points to the following findings:

- Forms of families have diversified over the decades, though it is more useful to focus on family functioning and family processes than on family structure.

- Life events present challenges that are more likely to be ameliorated in already well-functioning families and exacerbated in those that are less well-functioning at the outset.

- Events related to family formation, dissolution or re-formation present particular challenges that may result in positive and/or negative outcomes for individuals and their families, depending on the resources and supports that are available.

- Individual, family, community and societal factors can either smooth the negotiation of life events or make the path more difficult to traverse.

- The effects of life events, whether expected or unexpected, can vary greatly as a result of the levels of stress they engender.

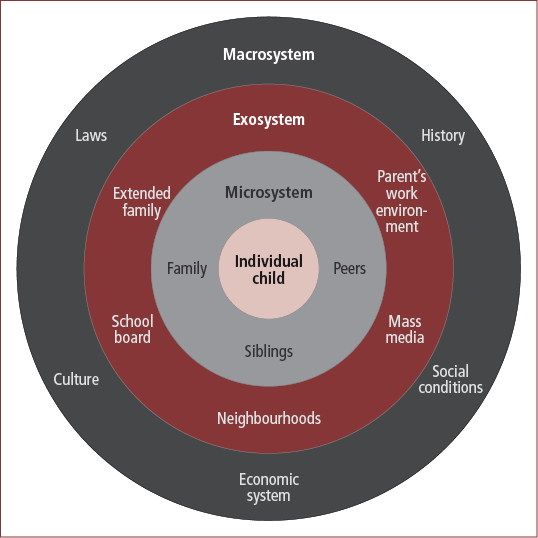

- The literature on life event scales classifies the extent of potential perturbation that can flow from life events and the way in which persons are affected by their contexts. It also looks at the sources of influence and support that surround the individual and the family that might ameliorate or exacerbate their responses.

- A sense of loss is a key dimension of many life events, and may have enduring effects.

- Another key dimension of life events is the degree of stress that they engender, and the associated and possibly cumulative effects on the health and wellbeing of those who experience them.

- Success in coping with stress is influenced by the extent of vulnerability or resilience that the person and the family exhibit at that time. Importantly, vulnerability and resilience are states, not traits, which will show variation between persons and variability across a lifetime.

- Factors related to the extent of social inclusion or exclusion are increasingly recognised as mediating and moderating the effects of life events.

- Service responses need to be framed to recognise both variations in life events and the different susceptibility of individuals to their negative effects, depending on their backgrounds, including their history of other stressful events, their vulnerabilities and the extent of available supports.

- A life events focus on service delivery requires significant shifts in approach from service providers around assessing needs from client descriptions of events and around service facilitation.

- In addition to direct service provision, easily accessible life events information portals are likely to significantly enhance the capacity of individuals and families to deal with stressful life events.

1. Families in Australia

1.1 Defining family

One of the most potentially oppressive prerogatives is the ability to define others, to establish the nature of reality, to characterise identities, and to identify desirable statuses, which include some and exclude others. (Hartman, 2003, p. 637)

Lodge, Moloney, and Robinson (2011) have suggested that, in simple terms, "family" is probably most commonly thought of in terms of a sense of belonging - usually, though not always, linked by biological and/or marital relationships. Consistent with this idea, McGoldrick and Carter (2003) argued that "families comprise persons who have a shared history and a shared future" (p. 376).

For statistical purposes, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2011b) considers "family" a little more narrowly:

- couples with or without resident children of any age;

- lone parents with resident children of any age; or

- other families of related adults, such as brothers or sisters living together, where no couple or parent-child relationship exists. (Summary of Findings, Families section, para. 2)

Although the ABS view of family is probably broad enough to deal with a large majority of those in need of family-related services, it does not include individuals (such as long-term carers), who may have no biological or marital relationship to any member of the household, but who may legitimately regard themselves as a family member.

Considered from a service delivery perspective, it is important for a workable definition of family to include those individuals who, in the words of the Child Support Agency's (2011) The Guide, are "fulfilling the function of family" (section 6.10.1). In this respect, the concept of a "domestic relationship", as defined in the NSW Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 s5 (see Box 1), has much to offer from a service delivery perspective.1

Box 1: Domestic relationships

A person has a "domestic relationship" with another person if the person:

(a) is or has been married to the other person, or

(b) has or has had a de facto relationship, within the meaning of the Property (Relationships) Act 1984, with the other person, or

(c) has or has had an intimate personal relationship with the other person, whether or not the intimate relationship involves or has involved a relationship of a sexual nature, or

(d) is living or has lived in the same household as the other person, or

(e) is living or has lived as a long-term resident in the same residential facility as the other person and at the same time as the other person (not being a facility that is a correctional centre within the meaning of the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999 or a detention centre within the meaning of the Children (Detention Centres) Act 1987), or

(f) has or has had a relationship involving his or her dependence on the ongoing paid or unpaid care of the other person, or

(g) is or has been a relative of the other person, or

(h) in the case of an Aboriginal person or a Torres Strait Islander, is or has been part of the extended family or kin of the other person according to the Indigenous kinship system of the person's culture.

Source: Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW) s5

Details of the many ways in which Australian families form, define and dissolve themselves are considered in section 1.3. Before addressing this, it is useful to reflect briefly on notions of family "normality".

1.2 Families and "normality"

Reflecting on "changing families in a changing world", Walsh (2003a) cited the oft-quoted observation from Tolstoy that while "all happy families are alike, every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way" (p.3). Walsh interpreted this statement to mean that for Tolstoy, family happiness and the successful raising of children was achieved at the cost of social conformity.

Walsh (2003a) also cited a less well-known observation of Nabokov that appears to turn Tolstoy's reflection on its head. According to Nabokov, "all happy families are more or less dissimilar; all unhappy families are more or less alike" (p. 3). Reflecting on 21 years of research into "normal" family processes, Walsh suggested that over this period, families have become increasingly complex. She noted that, "despite the dire predictions of family demise by single model advocates, it appears that Nabokov got it right" (p. 3).

Consistent with this observation, Epstein, Ryan, Bishop, Miller, and Keitner (2003) suggested that:

to attempt to arrive at a definition of a healthy or normal family may seem to be - or may actually be - a fool's errand [because] when we attempt to describe a normal family, the variables to consider multiply by quantum leaps. (p. 581)

This may be why a systematic search for definitions of the normal family by Epstein and his colleagues (2003) revealed a pattern not of inclusive statements but of exclusionary criteria. In other words, Epstein et al. found that "normal" families were those that were "not reconstituted", "not alcoholic" etc. In similar vein, Walsh (2003a) examined the assumptions behind definitions of "normal" families and the limitations that these assumptions imply. She suggested that normal families are variously seen as: asymptomatic, typical, average, ideal, or having pre-defined and agreed-upon "healthy" transactions and processes.

According to Walsh (2003a, 2003b), each of these categories of normality reflects a particular tradition that has been grafted on to analyses of family functioning. Thus, the idea that a normal family is one that is "asymptomatic" has its origins in the medical/psychiatric sphere.2 But the literature would suggest that only a minority of families fall into this category. Kleinman (1988), for example, found that at any given time, 75% of individuals are experiencing at least some symptoms of physical or psychological distress; while pioneering family therapist Minuchin (1974) suggested that no family is problem-free. Walsh's key point here was that are obvious dangers in equating family normality merely with an absence of problems or symptoms (Walsh, 2003b).

Walsh (2003b) also suggested that the concepts of a "typical" or "average" family derive mainly from (and perhaps serve the needs of) social science researchers and statisticians. In this model, families deviating significantly from the mid-range of a normal distribution are, of course, statistically aberrant. Walsh suggested, however, that it is not uncommon for this "deviance" to take on a more personalised meaning and to become conflated with the pathologising of difference.

One mechanism for the pathologising of difference can be the conflation between "typical/average" and "ideal" families. Walsh (2003a) was especially concerned with what she saw as a tendency to derive healthy (idealised) standards in families "from clinical theory based on inference from disturbed cases" (p. 6).

If, as Walsh (2003a) proposed, Nabokov was correct in suggesting that all happy families are more or less dissimilar, is it nonetheless possible to identify what is "normal"? There is considerable consensus in the literature that a good indicator of healthy families is their capacity to negotiate transitions and that a good framework for understanding how families negotiate their transitions across life events is a systemic one.

Carr (2006) defined a "system" as:

a complex rule-governed organisation of interacting parts, the properties of which transcend the sum of the properties of the parts, and which is surrounded by a boundary that regulates the flow of information and energy in and out of the system. Family systems are complex rule-governed organisations of family members and their interrelationships. The properties of a family cannot be predicted from information about each of the family members only [emphasis added]. Family relationships are central to the overall functioning of a family. (p. 73)

A systemic approach to understanding family functioning was first articulated by professionals (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers and counsellors, among others) who, in the 1950s, were struggling both to make sense of and have a positive impact on deviant behaviour in children. The virtually unchallenged view prior to the 1950s was that behavioural problems were essentially manifestations of individual disorders and therefore required individual therapeutic intervention. The core insight that shifted professionals towards the framing of problems in family systemic terms was recognition that at the heart of many family problems were interpersonal rather than intrapersonal difficulties. This insight had its origins in pioneering work by therapists such as John Bell in the United States and John Bowlby (better known for his work on attachment theory) in the United Kingdom. Carr (2006) described John Bell's original description of a boy expelled from school as follows:

In the face of strong resistance from established practice and the parents of the boy, who saw the difficulties as intrinsic to the child, Bell conducted a series of family sessions. From these he found that the boy, an adopted child, had developed behaviour problems as his parents' relationship had gradually deteriorated. The deterioration occurred when the father developed an alcohol problem and this in turn because of the father's disappointment in the difficulty his wife had in caring for the child. She was perfectionist and harboured strong feelings of hostility towards the boy because of his failure to meet her perfectionist standards. Bell's therapy focused on ameliorating the family's relationship problems, not in interpreting the boy's intra-psychic fantasies, the standard approach that would have been taken in the late 1950s. (p. 49)

Several mainstream models of family therapy have emerged since that time, but the interpersonal emphasis has largely remained. Rather than assume that the primary cause of behaviour lies within an individual, systemic family therapists focus on interactions and "feedback loops" between family members and between families and the "outside world". Importantly from a systemic perspective, the significance of family structure lies not in the structure itself, but in the impacts the structure may be having on intra-familial relationships and on how well or how poorly the structure permits engagement with the outside world.

Thus, the fact that there are two children of comparable age in a blended family is not of special interest in itself. But it becomes of interest if, for example, it contributes to strained relations or confusion between the children themselves or their siblings or the parents. In addition, different family types present themselves to, and are perceived by, external systems such as other families, schools or services in different ways. In sending an invitation to a concert to "mothers and fathers", for example, a school might inadvertently exclude a child who is being parented by grandparents or by lesbian mothers. Or a service might not be available to a family because their child's non-biological parent is not listed on their birth certificate.

This brings us back to the definition of "family" and the determination of what is "normal". It is important for professionals and for others who interact with families to appreciate the structural aspects of how families form, sustain, dissolve and re-form themselves and hand over to the next generation. The significance of this understanding lies not in the fact that one structure is inherently superior to or more "normal" than another. Rather, some family structures, such as blended families and separated families, have the potential to offer significant support to their members over the life course; but they may be more vulnerable in other areas such as financial survival, which may in turn exacerbate any interpersonal difficulties.

The way in which different family structures interact with one another and with institutions such as schools, government and services will open up or diminish opportunities; again, this may affect internal family relationships.

Family type is an important barometer of social and technological change; it both signals and influences changing social mores; and it both responds to and frequently demands more of developing technologies, such as advances in in-vitro fertilisation.

The next section examines how partnerships and families are formed, dissolved and re-formed in Australia. These data form an important backdrop for understanding how contemporary families negotiate life events.

1.3 Family formation, dissolution and re-formation in Australia

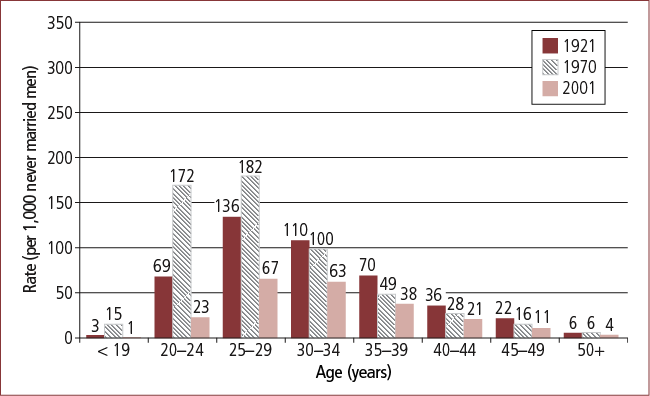

Marked changes have occurred in rates of first-time marriages for different age groups (i.e., the number of people who marry for the first time per 1,000 never-married people of the same age). Marriage rates increased gradually in the first 70 years of the 20th century, while age at first marriage fell, except during the Great Depression of the 1930s when marriage was often postponed (ABS, 2000b, 2002b, 2005). The steepest decline in age at marriage occurred from World War II to the 1970s. These trends are evident in Figures 1a and 1b, which depict first marriage rates per 1,000 never-married men and women in different age groups in 1921, 1970 and 2001.3

Figure 1a: Age at first marriage, men, 1921, 1970 and 2001

Source: ABS (2000b, 2002b, 2005)

Figure 1b: Age at first marriage, women, 1921, 1970 and 2001

Source: ABS (2000b, 2002b, 2005)

In 1921, women were most likely to marry for the first time when in their early and late twenties (applying to 128 and 139 women per 1,000 never-married women in these respective age groups), and men were most likely to marry when in their late twenties and early thirties (applying to 136 and 110 per 1,000 never-married men in these respective age groups). By 1970, the proportion of men and women marrying when in their early twenties had increased substantially, with women being considerably more likely to marry at this age than when in their late twenties (290 and 188 per 1,000 respectively), and with the first marriage rate for men in their early twenties being almost as high as that for men in their late twenties (172 and 182 per 1,000 respectively). By 2001, men and women were most commonly first getting married when in their late twenties or early thirties, with similar proportions of men marrying during these two ages (67 and 63 per 1,000 respectively), but with women being more likely to enter marriage when in their late twenties than early thirties (83 and 65 per 1,000 respectively).

Thus, marrying before the age of 25 is now fairly uncommon for both men and women. Furthermore, the timing of marriage is now more diverse than in the earlier periods, as reflected in the relatively "flat" pattern of age-related marriage rates for 2001, apparent in Figures 1a and 1b.

Finally, it can be seen that the first-time marriage rates across all ages are lower for 2001 than for the other periods shown. The fall in first marriage was the most striking for men and women aged 20-24 years, followed by those aged 25-29 years. While Figures 1a and 1b show a snapshot of first marriage rates at different times, the overall decline in the marriage rate has been persistent over the three decades to 2001. In other words, the proportion of people of all ages who had never been married in 2001 was higher than it was not only during the "marriage boom" period, but also in 1921.

The relatively early and high rate of marriage in the mid-20th century has been attributed to the booming post-World War II economy, along with increasing social pressure for marriage. Such pressure was fed by the marriage boom itself, which strengthened norms to not only get married but also to marry young. This was coupled with a continuing disapproval of extramarital sex and unmarried mothers (Gilding, 2001; McDonald, 1984, 1995). In addition, the introduction of the contraceptive pill in 1961, and its subsequent cost-reducing inclusion on the Pharmaceutical Benefits List in 1972, initially supported early marriages, because almost totally reliable contraception gave couples much greater opportunities than in the past to disconnect the decision to marry (and thus be sexually active without censure) from the decision to have children. Women could therefore continue working after marriage - as long as their employer accepted married women. As Carmichael (1984) explained: "the pill rendered marriage more a licence for cohabitation and less a declaration of intent to become parents" (p. 127).

1.3.1 The rise in cohabitation

A logical extension of Carmichael's (1984) observation is that the contraceptive pill also provided couples with opportunities to live together without marrying. As increasing numbers of couples followed this pathway, the strong social condemnation about premarital sexual relationships gradually weakened (de Vaus, 1997), thereby encouraging the more conventional to follow suit.4

Despite this, even today, the vast majority of couples who live together are married to each other. Of all heterosexual couples living together, the proportion who cohabit appear to have increased from less than 1% in 1971 to nearly 6% in 1986, and 15% in 2006 (ABS, 1995a, 2007a; Carmichael, 1995; Santow & Bracher, 1994). Therefore, although marriage has been losing its accuracy as an indicator of the prevalence of partnerships, nearly nine in ten couples are nevertheless married to each other.

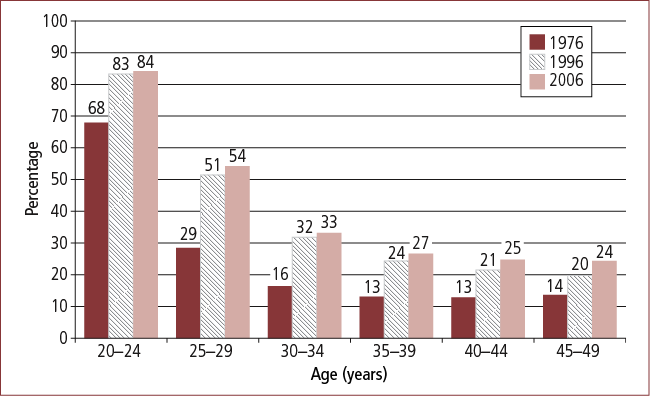

At the same time, as Figure 2 demonstrates, the prevalence of marriage is not a useful indicator of the prevalence of partnerships among those in younger age groups. While the vast majority of men and women under 25 years old do not have partners, those who do are more likely to be cohabiting than married (82% vs 18% of partnered individuals under 20 years old, and 61% vs 39% of those aged 20-24 years). As age increases beyond 25 years, marriage increasingly dominates.

Figure 2: Persons living with a partner, cohabiting or married, by age, 2006

Note: Based on place of usual residence.

Source: ABS (2007a)

1.3.2 Changing patterns of partnership formation

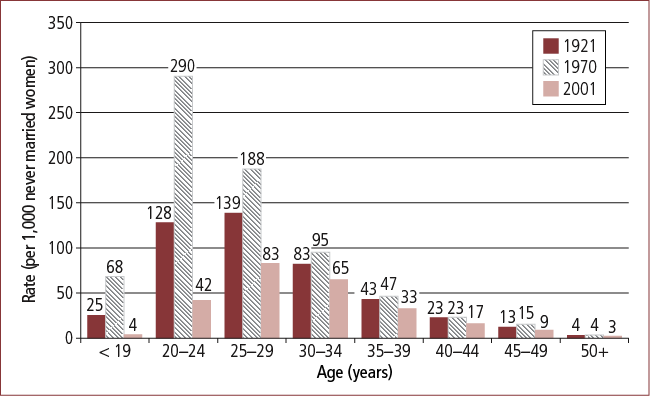

Figure 3, which focuses on trends for women, shows that first unions have increasingly commenced with cohabitation rather than marriage. Almost all of the women who were born before 1942 married at the outset, and for those born in 1952-61, marriage was still the more common mode of commencing a union (applying to 60%). However, cohabitation was the more common gateway to union formation for women who were born in 1962-1971 (56%), while for the most recent cohort (born from 1972 onwards), unions commencing with cohabitation were more than twice as likely as unions commencing with marriage (69% vs 31%).

Figure 3: First couple relationships, women, commenced with marriage or cohabitation, by year of birth

Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA), Negotiating the Life Course (ANU), Australian Life Course Survey (AIFS)5

In addition, cohabitation is now the most common pathway to marriage, applying to 79% of people who married in 2010, compared with only 16% in 1975 (ABS, 1995b, 2011c). Consistent with this trend, a national Australian survey conducted in the late 1980s suggested that around half the population recommended that couples should live together before they married, but few recommended cohabitation in the absence of any intention to marry (McDonald, 1995).

1.3.3 Barriers to partnering

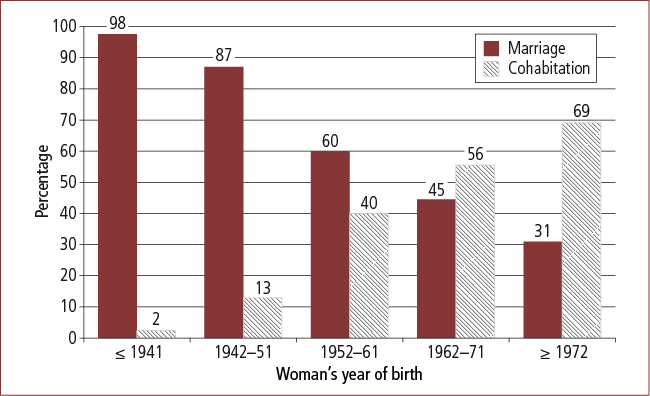

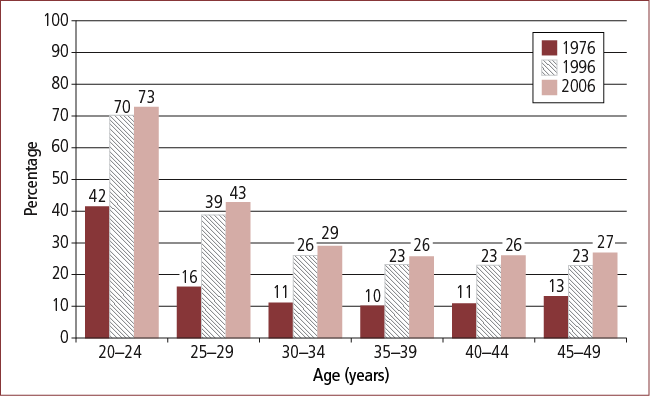

Figures 4a and 4b suggest that, across all five-year age groups between 20 and 49 years, the proportion of unpartnered people increased between 1976 and 2006. That is, the increase in the rate of cohabitation has not been large enough to compensate for the decrease in the marriage rate. (While the increase in the unpartnered rates between 1976 and 1996 appears to be greater than the increase that occurred between 1996 and 2006, note that the first period spans twenty years while the second period spans ten years.)

Figure 4a: Proportion of men living without a partner, by age, 1976, 1996 and 2006

Sources: 1976, 1996 and 2006 Census

Figure 4b: Proportion of women living without a partner, by age, 1976, 1996 and 2006

Sources: 1976, 1996 and 2006 Census

These trends appear to be closely linked with changes in the labour market and economy. In the 1980s and 1990s, the demands for a skilled workforce increased. Low-skilled yet relatively highly paid and secure jobs available to early school leavers virtually disappeared and were replaced by jobs entailing fixed-term contracts and part-time or casual hours, thereby providing limited economic security (McDonald, 2000; Saunders, 2001). McDonald (2001) argued that this era of job insecurity was accompanied by a strong economic cycle of "booms and busts" and rising or fluctuating house prices, which combined to encourage young people to invest in education. Such trends result in delays in partnership formation.

Birrell et al. (2004) concluded that these forces created a growing divide between the "haves" and the "have-nots". Their analysis suggests that much of the decline in overall partnering has occurred among those with no post-school qualifications, as such people have poor job prospects.

In addition, women's increased participation in tertiary education has increased their chances of achieving financial self-sufficiency and self-fulfillment outside any partnership. Although young people may prefer to be partnered, they may be more cautious about taking this step, wishing to explore other options before committing to a partnership, and/or they may prefer to have no relationship rather than one that fails to meet their emotional needs (see, for example, Qu & Soriano, 2004).

Qu and Soriano (2004) identified several barriers to partnership formation. Consistent with arguments in the literature suggesting an increased emphasis on the quality of relationships (Clulow, 1995; Giddens, 1992; McDonald, 1984), the explanations provided by young adults often highlighted the difficulty of finding a partner who could meet their emotional needs. The widespread fragility of relationships also led them to exercise caution, while time pressures linked with study and/or work, including career development, were also commonly mentioned reasons behind limited opportunities to find a partner. Other problems highlighted were the scarcity of suitable places for meeting people, particularly for those living in rural areas, and, for lone mothers, the difficulties of having children on their own, which meant that their parenting responsibilities limited their opportunities to meet people and some of them worried about the impact of partnering on their children.

As discussed in section 1.3.4, most lone mothers have, at some stage, lived with the father of their child. This highlights the fact that the prevalence of unpartnered people in any single year (shown in Figures 4a and 4b) only represents a snapshot that does not take account of any past transitions in and out of relationships.

1.3.4 Separation and divorce

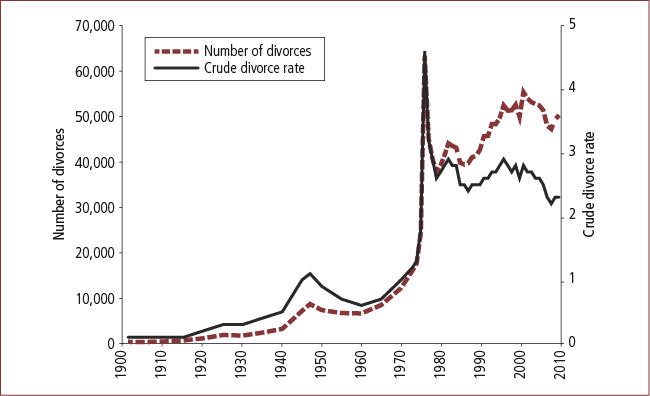

The increase in the divorce rate over the last 40 years represents one of the most spectacular family-related trends of the 20th century. Radical changes in divorce legislation and other social changes played important roles in this development (see Carmichael & McDonald, 1987; Nicholson & Harrison, 2000; Parker, Parkinson & Behrens, 1999).

Before the Matrimonial Causes Act 1959 (Cth) came into operation in 1961, divorce legislation was the responsibility of the state and territory governments. The grounds for divorce were almost exclusively "fault-based", but varied across the states and territories, with offences being added over the years. Desertion was the most frequently used ground for divorce, followed by adultery (Coughlan, 1957).

With the establishment of uniform legislation in 1961, it was still necessary to prove fault in order to obtain a divorce, or to prove a separation of at least five years. As before, desertion remained the most commonly used ground for divorce, followed by adultery. Separation became the third most commonly used ground, suggesting that most unhappily married people who wished to divorce opted for a process that required them to prove fault, rather than wait for five years.

However, the federal government came under increasing social pressure to introduce divorce legislation that was not fault-based. This pressure led to the introduction of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), which came into force in 1976. The Act allowed divorce to be based on just one ground - "irretrievable breakdown" - as measured by at least 12 months' separation.

In addition, the Child Support Scheme, phased in over 1988 and 1989, substantially increased the amount, regularity and predictability of financial support from non-resident parents (typically fathers) to the children. These factors, along with real increases in social security payments and allowances (Harding & Szukalska, 2000) and a rise in the workforce participation of mothers, have led to higher living standards for lone mothers and their children, providing greater scope for many more mothers who were unhappy with their marriages to proceed with divorce.

The impact of these legislative and other changes on divorce (and thus remarriage) has been dramatic, as shown in Figure 5. The crude divorce rate (that is, the number of divorces per 1,000 resident population) was very low for most of the 20th century. There was a slight rise after World War II, partly reflecting the instability of hasty wartime marriages and the disruptive effects of the war on marriage (Carmichael & McDonald, 1987; Coughlan, 1957). The divorce rate then fell for several years and began rising again in the late 1960s.

Figure 5: Crude divorce rate and number of divorces, 1901-2010

Sources: ABS. (various years). Marriages and divorces (Cat. No. 3310.0)

A spectacular rise in the divorce rate occurred in 1976, as the backlog of long-term separations was formalised and some divorces were brought forward. Not surprisingly, the rate then subsided, but has remained much higher than it was before the Act came into operation. Between 2007 and 2010, the crude divorce rate has remained at 2.2 to 2.3 - the lowest rate since the Act came into operation, having fluctuated at a higher rate (2.5 to 2.9) between 1978 and 2006.

The crude divorce rate is based on the entire population, including those who are too young to marry. Another measure of the divorce rate is the number of divorces per 1,000 married women. Since 1976, rates were lower in the late 1980s (between 10.6 and 10.9), but then climbed fairly steadily from 11.8 in 1991 to 13.2 in 1996. Between 1997 and 2006, they fluctuated between 12.0 and 13.5 (ABS, 2007b).6

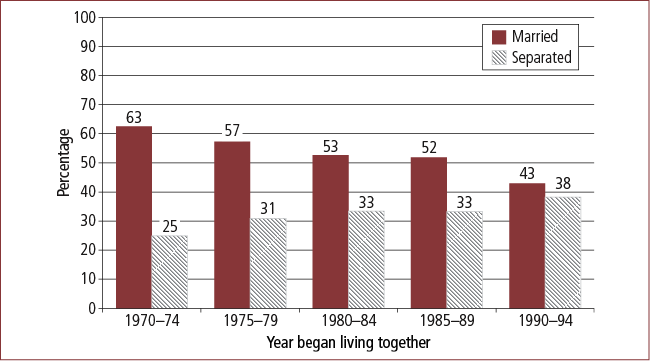

What proportion of marriages seem likely to end in divorce? The answer to this question depends on the estimation method adopted. Based on current levels of marriage, divorce, remarriage, widowing and mortality, the ABS estimates that one-third of marriages are likely to end in divorce (ABS, 2001b). However, as noted above, the divorce rate by definition fails to capture outcomes of cohabitation. Cohabitation tends to be short-term; for example, only 9% of those whose cohabitation commenced in the early 1990s were still cohabiting with the same partner by 2001 (7-11 years later) (de Vaus, 2004). This raises an important question: To what extent is the short duration of cohabitation explained by the above-noted change in the pathway to marriage? That is, what proportion of cohabitations end in marriage rather than separation?

Figure 6 shows the proportions of first relationships that began with cohabitation and ended in marriage or separation for those who began cohabiting during different years. Of those whose first unions commenced in the early 1970s, 63% had married within five years and 25% had separated. But in more recent times, the probability of cohabitation converting to marriage has fallen progressively, and the probability of the relationship ending in separation has increased. Of those who commenced cohabiting in the early 1990s, the probabilities of separation or marriage occurring within five years were almost equal. These statistics highlight the fact that, just as the marriage rate is no longer a reasonable proxy for the rate of unions (most particularly for the union rate among young adults), divorce statistics have become progressively less useful as a reflection of relationship breakdown trends.

Figure 6: Outcomes of cohabitation after five years, by year first began cohabiting

Note: Cohabitation as a first union for one or both partners.

Source: Weston, Qu, & de Vaus (2008), based on HILDA Survey, Wave 1

1.3.5 Re-partnering

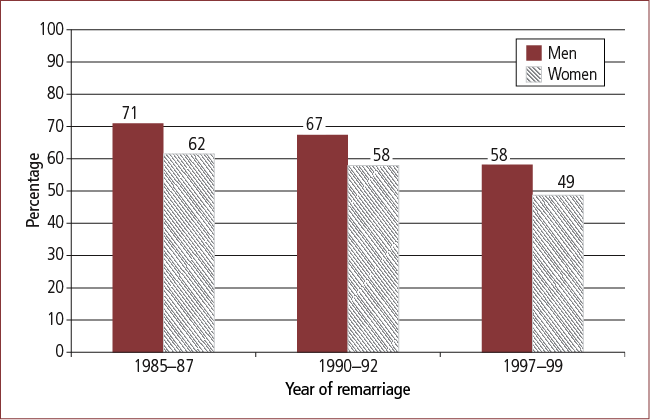

For the first half of the 20th century, re-partnering almost exclusively involved remarriage following widowhood and were fairly uncommon. For instance, in 1911 and 1920, only 10-11% of marriages represented a remarriage for one or both parties - a trend that increased to only 17% in the mid-1950s. By 1980, on the other hand, 32% of marriages represented a remarriage for the bride and/or groom, with the majority of one or both parties being divorcees. This is not surprising given that the size of the divorced population had increased with the introduction of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (as discussed above). The proportion of marriages where at least one party was previously married has declined slightly since 1980 (29% in 2002, compared with 32% in 1980).

Consistent with recent trends for first-marriage rates, remarriage rates following divorce have fallen for both men and women (Figure 7). Based on the remarriage rates, the proportion of divorced men who would remarry fell from 71% in the late 1980s to 58% in the late 1990s. For women, the proportion fell from 62% to 49% over the same period (ABS, 2001b).

Figure 7: Proportion of divorcees remarrying, by gender

Source: ABS (2001b)

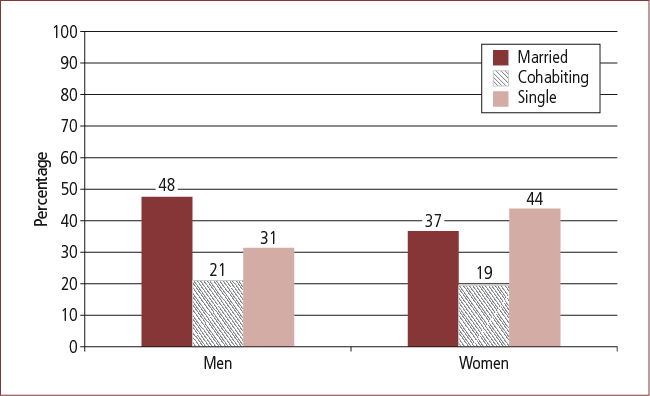

The remarriage rate fails to capture the complete picture of post-divorce union formation, for substantial numbers of divorced men and women go on to cohabit instead. Figure 8 suggests that about one in five divorced men and women less than 55 years old were cohabiting in 2009.

Figure 8: Current relationship status of divorced men and women aged under 55 years, 2009

Source: HILDA, Wave 9 (2009)

Taken together, the above sets of trends suggest that marriage rates can no longer be relied upon to gauge partnership rates, especially among younger Australians and the divorced population, due to the significant increase in cohabitation among these groups. Not only have marriage rates fallen in recent decades, but there is also greater variation in the timing of first marriages today than in the past, and the average age of first marriage is now higher than it was throughout the twentieth century. Finally, rates of cohabitation have now overtaken marriage rates among those under the age of 25 years.

1.3.6 Relationship fragility

A number of interacting factors have contributed to the apparent increase in the fragility of relationships. Some of these relate to the weakening of constraints on separation, including the introduction of 12 months' separation as the only grounds needed for divorce, and improvements in the living standards of lone mothers (noted above), along with the diminished stigma attached to divorce and lone parenting (see, for example, de Vaus, 1997).

Several authors have also argued that in societies that provide opportunities for pursuing productive, enjoyable lives outside of marriage, the continuation of a marriage is largely contingent on the strength of the emotional bond between the spouses. According to this view, individuals tend to expect their relationships to provide them with considerable intimacy, mutuality, happiness and self-fulfillment (see Wolcott & Hughes, 1999). As Wolcott and Hughes pointed out, the achievement of such expectations can be difficult to maintain as the reality of everyday life unfolds (with wives being more likely to initiate separation than husbands). As these authors explain, other structural factors, including intensified work pressures and increased employment insecurity, may also contribute to marriage breakdown.

A number of other factors appear to increase the chance of divorce, including young age at marriage, premarital pregnancy, premarital cohabitation,7 low income, non-traditional family values, and mental illness (see Wolcott & Hughes, 1999). Some of these are closely connected (e.g., early marriage and low income). Not surprisingly, however, Wolcott and Hughes found that the most common reasons people give for their marriage breakdown relate to the quality of the relationship itself or emotional/personality factors that affect the relationship (e.g., communication difficulties, loss of love, "drifting apart" and growing incompatibility, conflict, infidelity, and emotional/personality problems or mental illness).

Researchers have paid far less attention to factors linked with the increased fragility of cohabiting relationships. One possibility for this is that couples have started living together at an earlier stage in their relationship than in the past. Allied with this issue is that "cohabitation" can have a variety of meanings, including: a trial marriage, a period before an intended marriage, an arrangement that may continue indefinitely but would convert to marriage if and when each partner wanted a child, a "no-strings-attached" relationship, or a relationship with no clear plans (where the parties are just "taking it one day at a time"). Partners may differ in their interpretation of the relationship, and their interpretation may well change. To the extent that cohabitation is treated as a trial marriage, the partners may consider subsequent separation (or marriage) as a reflection that their cohabiting experience had achieved its purposes.

However, it has also been argued that some couples who perceive problems in the cohabiting relationship may decide to marry to "save" their relationship (e.g., Schoen, 1992; Weston, Qu & de Vaus 2005a). In other words, the cohabitating experience may systematically lead to self-selection into marriage of some unsuitable matches (although the extent to which this response to problematic relationships occurs is unknown). But why would people decide to "save" an unhappy relationship? Possible reasons include the already long-term investment in the cohabiting relationship and difficulty of leaving, a desire to attain the status of marriage or to have children in marriage, and age-related concerns about fertility loss and the narrowing marriage market.

In Australia, Weston, Qu and de Vaus (2005b) examined the pathways of cohabiting couples over a two-year period,8 involving three waves of survey data. Consistent with previous research on factors contributing to divorce, this analysis suggested that cohabiting couples had an increased chance of separation if they had a low combined income and if the woman or both partners was not entirely satisfied with the relationship. In addition, the risk of separation increased if one partner wanted to have a child and the other did not - especially if it was the male partner who wanted the child. The probability of marriage, on the other hand, increased where the male partner alone had a university degree, where both partners expressed high satisfaction with the relationship, or where a pregnancy or birth had taken place during the previous two years.

These trends need to be considered tentative, for no single study is definitive. A large-scale longitudinal study of relationships that includes couples who are cohabiting is needed to throw light on the meaning of cohabitation for each partner, the ways in which these meanings may change, and the various factors (including couple dynamics) that interact to influence outcomes of cohabitation.

Various models have been developed to explain the processes linked with relationship breakdown. For example, Karney and Bradbury (1995) argued that the personal vulnerabilities and resources, including personality traits, of each partner interact with stressful events and "adaptive processes" (modes of handling conflict, communication styles, level of supportiveness, etc.). According to this model, adaptive processes in turn influence the way in which the relationship is evaluated, which then helps shape "the next step". Although Karney and Bradbury focused on divorce, their model is relevant to cohabitation, where "the next step" may be marriage, separation, or continuation of the cohabitation.

Finally, a framework for understanding relationship breakdown can be found in social exchange theory, which considers the stability of the relationship to be strongly influenced by a monitoring process involving the weighing up of the costs and benefits of the relationship, barriers to leaving, and the presence of any attractive alternatives (see, for example, Levinger, 1979).

1.3.7 Partnership trends and fertility

Trends in partnership formation and dissolution have implications for other aspects of family life. For example, the total fertility rate9 was lower in 2004 than it was during the Great Depression of the 1930s (1.77 in 2004, compared with 2.11 in 1934), with the lowest rate recorded being in 2001 (1.73).10 Although partnership trends were not the only reasons behind this decline, they were clearly important contributors.

While the proportion of babies born outside marriage has increased, particularly in the last three decades (from 12% in 1980 to 34% in 2008-10), babies born outside marriage are more likely to be born to women who are living with the baby's father rather than apart (ABS, 1982, 2011a).11 The importance of partnership status for fertility is reflected in the fact that the "baby boom", which began after World War II, was really a "marriage boom", as fertility rates within marriage changed little (Ruzicka & Caldwell, 1982). By 1961, the total fertility rate was the highest for the 20th century (3.55), but 15 years later, it had for the first time fallen below replacement level (currently 2.06).

While the fall in fertility in the 1920s and early 1930s applied to virtually all age groups of women, the fall in recent decades has been restricted to those under the age of 30 years, with the most spectacular rise, then fall, occurring for women in their early 20s. The proportion of women in their 30s giving birth to a child has increased in recent decades, although women in their late 30s are still less likely to have had a child compared with women of this age in the 1920s (ABS, 2011a).12

However, women who currently give birth when at least 30 years old are increasingly likely to be new mothers (42% in 2008, compared with 28% in 1993) (Laws, Li, & Sullivan, 2010; ABS, 2001a). In other words, as Jain and McDonald (1997) noted, women's total childbearing period has shortened.

Instability of relationships not only contributes to delays in childbearing and increases the risk of childlessness but may also cut short the time women with partners have for bearing children. The relationship between partnership status and stability and fertility intentions is suggested in a study spanning 10 years, conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (Qu, Weston, & Kilmartin, 2000).13 Fifty-seven per cent of those who reported in Wave 1 of the study that they intended to have children had become parents within the following 10 years, compared with 35-36% of those who did not intend to have children or who expressed uncertainty about this issue. Those who had separated from their partner between waves were the most likely to have changed their mind and to no longer intend having children, followed by those who had been continuously single. Nevertheless, such reversals of intention for the continuously single was more likely for the older than younger sample members. Intentions not to have children were more likely to be reversed by single respondents who subsequently re-partnered than by respondents who remained with the same partner over the decade. Thus, the evidence suggests that an overall increase in partnership break-ups is likely to increase the rate of childlessness. Therefore, it is likely that intervention strategies that successfully enhance the quality of relationships, and thereby decrease separation rates of both married and cohabiting couples, may have the added advantage of helping couples who want a child or more children to achieve their aims.

Although not so closely linked with partnership patterns, it is worth noting that in the Australian Temperament Project, 77% of 17-18 year olds indicated that they wanted to have children, while 18% indicated that they had not thought about this matter. Only 5% reported no desire to become a parent (Smart, 2002). Overall, however, the likelihood of childlessness has increased. For example, the ABS (2002a) projected that 24% of women who were in their childbearing years in 2002 would never have children.14

1.4 Mainstream and emerging family structures

1.4.1 Overview

Trends in partnership formation and stability, along with associated trends in the fertility rate, have contributed to the changing profile of Australian households and families. Although families may clearly extend across households, for the purposes of monitoring family types, the ABS (2010) defines families as "two or more persons, one of whom is at least 15 years of age, who are related by blood, marriage (registered or de facto), adoption, step or fostering, and who are usually resident in the same household". As Hugo (2001) pointed out, trends in family types can only be captured for recent decades, when Census data were collated on the basis of the family unit.

Figure 9 shows that couples with dependent children have lost their dominance. In 1976, almost half the households were couple families with dependent children (48%) and only 28% were couples living with no children (dependent or otherwise), but in 2006, these two types of families were represented in equal proportions (37%). In addition, the proportion of one-parent families with dependent children had increased from 7% to 11%, while the proportion of couples living with non-dependent children had decreased from 11% to 8%.

Figure 9: Distribution of family types, 1976-2006

Note: "Other families" includes one-parent families with non-dependent children, and non-classifiable families, such as brothers and sisters.

Source: ABS (2001c, 2007a)

According to ABS (2004) projections, couple families living without children will become more prevalent than those with children, with the former accounting for 41-49% of all families in 2026, and couples with children representing 30-42%. Such trends can be explained in terms of the large group of "baby boomers" who will no longer be living with their children and the increase in the number of couples who remain childless.

In addition, it should be noted that the traditional approach to studying household families does not capture the fact that some households contain more than two generations and/or siblings, aunts or uncles of the parents, or cousins of one of the generations. For instance, a grandparent may live with an adult child, or in a "granny flat" on the property of their adult child, while in other cases a lone-parent family may move to live with the children's grandparents.15 In each of three surveys conducted by the ABS in 1997, 2003 and 2006-07, multi-family households - including extended households - accounted for 3-4% of all family households (ABS, 2008). Cultures also can define families in very different ways, as Morphy (2006) has shown in considering Indigenous Australians' family relationship systems.

1.4.2 Grandparent families

The term "grandparent families" refers to families in which grandparents are the guardians or main carers of their grandchildren aged less than 18 years who are living with them. Such families represented only 0.2% of all families in 2006-07, with the number during this period being lower than in 2003 (14,000 vs 23,000) (ABS, 2008). However, the often tragic circumstances that led to such situations (e.g., mental health problems or substance abuse by the children's parents) and the multi-faceted difficulties that are often experienced within these families, has resulted in increased attention being paid to the needs of these families (e.g., Dunne & Kettler, 2008; Fitzpatrick & Reeve, 2003; Ochiltree, 2006).

1.4.3 Step- and blended families

Among families with children aged under 18 years old in 2006-07, 4% were step-families and 3% were blended families. Here, a step-family is formed when a parent re-partners and there is at least one child who is a step-child to one of the partners and there are no children born of, or adopted by, the couple. Blended families, on the other hand, include at least one step-child and at least one child born of, or adopted by, the couple. The representation of such families appears to have changed little since at least 1997 (ABS, 2008).

It is beyond the scope of this document to explore the issue of step-parenting in any depth. However, there is ample evidence that the introduction of step-parents creates many challenges that vary according to such factors as: the duration of separation; the amount of time a partner had been single; the timing of separation and re-partnering in the child's life; and, the gender "match" of the child and step-parent. Remarriages tend to be more fragile than first marriages, and some overseas studies suggest that: (a) this can largely be explained by the existence of step-children (see Coleman, Ganong & Fine, 2000); and (b) the more changes in their resident parents' relationship status, the greater is the chance of negative outcomes for the children, in terms of psychosocial adjustment, academic achievement and relationship stability in adulthood (Cherlin, 2008; Crowder & Teachman, 2004).

1.4.4 Families with children born through surrogacy or donated sperm/eggs

Advances in reproductive technologies have assisted in the creation of family arrangements that would have been far less usual and in some cases impossible in the past. Gilding (2001) argued that such technological developments will continue, as in the past, to help shape the scale and scope of family change. Reproductive technologies have opened up considerably more options for a range of individuals, such as aspiring same-sex parents (see below) and parents with fertility problems. But it is difficult to predict what impact arrangements that result from reproductive technology will have on the maturational and transitional tasks of family members and on the identity formation of the children in particular. Perhaps the quality of the relationships and the services and systems that support this will remain the key issue. In that sense, families formed as a result of reproductive technologies may be of less relevance as a family "type" than, say, separated families, or families with a "fly in-fly out" work arrangement, in which relationships are inevitably put under time and other constraints.

On the other hand, and somewhat paradoxically, as medical technology advances in other areas, it may be increasingly important to have access to our own genetic history, something not precluded by reproductive technology, but something not always given priority in the past.

1.4.5 Same-sex couples

Little is known about the prevalence of same-sex relationships and individuals with a homosexual orientation in Australia. In the 2006 Census, fewer than 1% of couples (0.6%) were identified as being in a same-sex relationship (ABS, 2007a). However, this may represent a considerable underestimate of the prevalence of sample-sex couples, given that such couples may be reluctant to disclose the nature of their relationship. The 2001 Census showed slightly more same-sex male than female couples (de Vaus, 2004), and this trend is also reflected in the 2006 Census data.

Compared with those in heterosexual relationships, individuals in same-sex relationships appear to be younger and better educated, seem more likely to hold professional occupations and to have no religious affiliation (de Vaus, 2004). However, it is possible that such apparent differences may result at least partly from a greater willingness of those who share such characteristics to disclose their relationship, compared with others in same-sex relationships. As a number of researchers have noted (e.g., McNair, Dempsey, Wise, & Perlesz, 2002; Perlesz et al., 2006), the meagre research so far conducted tends to be based on small, unrepresentative samples, but highlights the diversity of processes within these families and the greater importance of family process than form on the wellbeing of family members.

1.4.6 Living apart together

Another form of couple relationship, called "living apart together" (LAT), has been observed by social scientists in recent decades. Definitional variations suggest that LAT is a "fuzzy" and difficult to identify family form. For example, definitions vary in terms of whether the couple may be married, with Strohm, Seltzer, Cochran, and Mays (2009) defining these relationships as:

Intimate relationships between unmarried partners who live in separate households but identify themselves as part of a couple. These relationships are sometimes referred to as "non-residential partnerships". (p. 178)

Levin and Trost (1999), on the other hand, treated married couples living in two households as being in LAT relationships. In addition, each partner may have different ideas about whether they are living in the same home as the other partner, in two homes, or in the home in which the other partner does not live.

Such different ideas may stem from having different reasons for living apart together in the first place. For example, some couples in an intimate relationship may not yet feel ready emotionally or financially to move in together, and some couples may live in separate households to pursue employment in different locations or to maintain greater autonomy than would otherwise be possible. One partner may move to a new location in order to gain employment, with the other partner following if and when the leaver has become established and is certain that the decision to move is appropriate. The reasons tend to vary according to the age of the partners (e.g., young people who are still living in the parental home, compared with older widowed or divorced individuals who have already established their separate dwellings) (Strohm et al., 2009).

Wave 5 of the HILDA survey suggests that, in 2005, 1% of married people under 65 years and 19% of unmarried people of this age who were in an intimate, ongoing relationship spent less than half the time living with their spouse or partner.

1.4.7 Living alone

Finally, although the focus in this review is on trends that are obviously "family-related", it is important to recognise that the transition to and from living alone is a common family-related transition - an issue that is well demonstrated by Australian research conducted by de Vaus and Qu (2011). Their research, which investigated reasons for living alone, appears to be unique from an international perspective. They showed that, except for elderly people who are widowed, living alone tends to be a short-term arrangement and that across all age groups, living alone does not usually mean "being alone". The evidence is that family is an important factor in the world of most people who live alone.

De Vaus and Qu's (2011) research highlighted the fact that families exist across household boundaries - an issue that is also reflected in research on: (a) the nature and direction of support that occurs between older people and their adult children (e.g., Hayes, Qu, Weston & Baxter, 2011); and (b) families in which the parents have separated (e.g., Qu & Weston, 2010).

1 The NSW Department of Family and Community Services (FACS, 2011) adopted this definition in an overview of its Domestic and Family Violence Services Program.

2 This clinically based construction of normality tends to be loaded in the direction of pathology. Consider in this context the experience of Fischer (1985), who described how the psychological assessment manuals she was required to use when working as a young psychologist, contained no references to positive psychological functioning.

3 Age-specific first marriage rates for men and women are not available for the years since 2001. Crude marriage has exhibited a slight upward trend in the last decade, from 5.3 marriages per 1,000 resident population in 2001 to 5.4 marriages in 2010. Nevertheless, age at first marriage for men and women has continued to rise, with the median age at first marriage increasing from 28.7 years in 2001 to 29.6 years in 2010 for men and from 26.9 years to 27.9 years for women (ABS, 2002a, 2011b).

4 It should be noted that cohabitation is by no means a new phenomenon in Australia; it was also particularly prevalent among the working classes during the convict era (Carmichael, 1995).

5 Data from these three surveys were combined. The HILDA survey is a large-scale, national household panel survey that commenced in 2001. It was initiated and is funded by the Australian Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. The findings and views in this report, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either FaHCSIA or the Melbourne Institute. The HILDA survey involves face-to-face interviews and self-complete questionnaires. Data from Wave 1 (2001) were used in this analysis. The Negotiating the Life Course survey is a longitudinal survey undertaken by the Australian National University and University of Queensland. Data from Wave 1 (1996) were used in this analysis. The Australian Life Course Survey was a one-off survey conducted in 2006 by the Australian Institute of Family Studies..

6 The divorce rates for the married population since 2006 are not yet available.

7 However, most studies that compare differences in the stability of direct marriages and marriages preceded by cohabitation focus only on the length of the marriage rather than the length of the period of living together (see de Vaus, Qu & Weston, 2003).

8 This analysis was based on Waves 1 to 3 of the HILDA survey.

9 Here, the "total fertility rate" refers to the number of babies a woman can expect to have in her lifetime, given the age-specific birth rates prevailing at the time.

10 The recent increase in the total fertility rate since 2001 is due to increases in rates for those aged 30 or more years. The rate in 2008 was 1.96 (the highest for 30 years), which then subsided (1.90 in 2009 and 1.89 in 2010) (ABS, 2011a).

11 de Vaus (2004) cited figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) suggesting that 12% of babies born in 2000 were to women not living with the father, while 16% were born to cohabiting couples. Note that ABS and AIHW use difference data sources and the proportion of ex-nuptial births published by the two organisations may not be consistent.

12 For instance, in 1921, 102 babies for every 1,000 women were born to women aged in their late 30s, compared with only 70 per 1,000 in 2010. Although much media attention is currently given to women in their 40s having babies, the number of babies born per 1,000 women in their early 40s was three times higher in 1921 than in 2010 (44 versus 15).

13 This study was based a national sample of men and women who were initially randomly selected for interview in 1981 (when aged 18-34 years). Ten years later, 58% of the 2,500 respondents were traced and agreed to participate in a second wave.

14 This proportion is lower than that for women in the early part of the 20th century, with Census data showing that lifetime childlessness was at its highest level for women born between 1901 and 1905 (31%), due to the Great Depression (ABS, 2002b).

15 These arrangements differ from the category known as "grandparent families" noted in section 1.4.2.

3. Developmental and family templates as influences on life events

The first section of this chapter is concerned with individual identity development. The assumption behind this section is that the range of available responses of individuals to life events is influenced by their own psychosocial development. The second section is concerned with responses to loss. It will be argued in Chapter 4 that, while some life events and the transitions they induce represent an element of potential gain, they also entail an element of loss. Sometimes the loss is profound; sometimes it is barely in focus. However, understanding the dynamic of human loss is also an important factor in understanding our capacity to respond to life events. The third section summarises the normal tasks of successful family functioning.

3.1 Individual psychosocial development

Erikson (1959) has provided the most widely used model of individual identity development. Erikson's model attempted to pinpoint personal dilemmas that must be resolved at various stages of development. Resolution of these dilemmas affects an individual's capacity to make effective transitions at both a personal level and within the family. The model is summarised in modified form (see Newman & Newman, 2003) in Table 1.

| Stage (years) | Dilemma (main process) | Virtue (positive self-description) | Pathology (negative self-description) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy (0-2) | Trust vs mistrust (mutuality with caregiver) | Hope (I can attain my wishes) | Detachment (I will not trust others) |

| Early childhood (2-4) | Autonomy vs shame & doubt (limitation) | Will (I can control events) | Compulsion (I will repeat this act to undo the mess that I have made and I doubt that I can control events, and I am ashamed of this) |

| Middle childhood (4-6) | Initiative vs guilt (identification) | Purpose (I can plan and achieve goals) | Inhibition (I can't plan or achieve goals, so I don't act) |

| Late childhood (7-11) | Industry vs inferiority (education) | Competence (I can use skills to achieve goals) | Inertia (I have no skills, so I won't try) |

| Early adolescence (12-18) | Group identity vs alienation (peer pressure) * | Affiliation (I can be loyal to the group) | Isolation (I cannot be accepted into a group) |

| Adolescence (19-22) | Identity vs role confusion (role experimentation) | Fidelity (I can be true to my values) | Confusion (I don't know what my role is or what my values are) |

| Young adulthood (23-34) | Intimacy vs isolation (mutuality with peers) | Love (I can be intimate with another) | Exclusivity (I have no time for others, so I will shut them out) |

| Middle age (34-60) | Productivity vs stagnation (person-environment fit and creativity) | Care (I am committed to making the world a better place) | Rejectivity (I do not care about the future of others, only my own future) |

| Old age (60-75) | Integrity vs despair (introspection) | Wisdom (I am committed to life but I know I will die soon) | Despair (I am disgusted at my frailty and my failures) |

| Very old age (75-death) | Immortality vs extinction (social support) * | Confidence (I know that my life has meaning) | Diffidence (I can find no meaning in my life, so I doubt that I can act) |

Note: * Additions to Erikson's original model suggested by Newman & Newman (2003).

Source: Adapted from Erikson (1959) and Newman & Newman (2003)

3.2 The human experience of loss

The well-researched process of responding to unambiguous loss has been summarised by Carr (2006) (see Table 2). These reactions to bereavement and terminal illness - probably the most extreme forms of loss - have parallels in the reactions to many social readjustments. The processes are clearly evident, for example, in responses to separation and divorce (Power, 1996). Frequently, however, they have echoes in other standard transitions, such as retirement or a child leaving home. Even "happy events", such as the birth of a child, can precipitate grief-like reactions linked to such issues as the loss of independence and loss of income.

| Grief process | Bereavement | Terminal illness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying theme | Adjustment problems | Underlying theme | Adjustment problems | |

| Shock | I am stunned by the loss of this person. | Complete lack of affect and difficulty engaging emotionally with others; poor concentration | I am stunned by my prognosis and loss of health. | Complete lack of affect and difficulty engaging emotionally with others; poor concentration |

| Denial | The person is not dead. | Reporting seeing or hearing the deceased; carrying on conversations with the deceased | I am not terminally ill. | Non-compliance with medication regime |

| Yearning and searching | I must find the deceased. | Wandering or running away; phoning relatives | I will find a miracle cure. | Experimentation with alternative medicine |

| Sadness | I am sad, hopeless and lonely because I have lost someone on whom I depended. | Persistent low mood, tearfulness, low energy and lack of activity; appetite and sleep disruption; poor concentration and poor work | I am sad and hopeless because I know I will die. | Giving up the fight against illness; persistent low mood, tearfulness, low energy and lack of activity; appetite and sleep disruption; poor concentration and poor work |

| Anger | I am angry because the person I needed has abandoned me. | Aggression; conflict with family members and others; drug or alcohol abuse; poor concentration | I am angry because it's not fair. I should be allowed to live. | Non-compliance with medication regime; aggression; conflict with medical staff, family members and peers; drug or alcohol abuse; poor concentration |

| Anxiety | I am frightened that the deceased will punish me for causing their death or being angry with them. I am afraid that I too may die of an illness or fatal accident. | Separation anxiety; agoraphobia and panic; somatic complaints and hypochondriasis; poor concentration. | I am frightened that death will be painful or terrifying. | Separation anxiety and regressed behaviour; agoraphobia and panic |

| Guilt and bargaining | It is my fault that the person died so I should die. | Suicidal behaviour | I will be good if I am allowed to live. | Over-compliance with medication regime |

Source: Carr (2006, p. 24)

As key researchers, such as Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe, and Schut (2001), have continually pointed out, reactions to the experience of loss rarely follow the sequence outlined in Table 2. Thus, for some, shock can quickly express itself as anger; for others, the shock can (at least for a time) be cushioned by denial. The relevance of this body of research to the life events literature is that human transitions are mediated by psychological processes of adjustment that are frequently linked to a sense of loss, and that these processes take time (Carr, 2006; Power, 1996; Stroebe et al., 2001). The grief process linked to bereavement, for example, may take years. But the grief associated with, say, a redundancy, may also take a considerable amount of time to resolve itself. This may be one reason why an accumulation of events, especially in a relatively short space of time, increases the chances that an individual or a family may be overwhelmed. It also reinforces the observation, noted in Chapter 5, that clients seeking assistance from government departments are frequently in quite a vulnerable state.