Families Then & Now: Income and wealth

August 2020

Diana Warren

Download Research report

Many changes have occurred in Australia since the establishment of the Australian Institute of Family Studies in 1980. This snapshot outlines some of the significant changes in household incomes, household wealth and also the amount of household debt over the last forty years

Key trends

The trends in income and wealth

With increases in overall rates of female labour force participation and more women working full-time, average household incomes have increased substantially over the past few decades. Household wealth has also increased, with the average net worth of Australian households passing one million dollars in the 2017/18 financial year.

Gender pay gap narrows - but not by much

Women, on average, earn considerably less than men. Even among those who work full-time, there is a significant difference in earnings. Several factors contribute to this difference, including gender discrimination, occupational segregation, part-time work and time out of the labour force due to caring responsibilities.

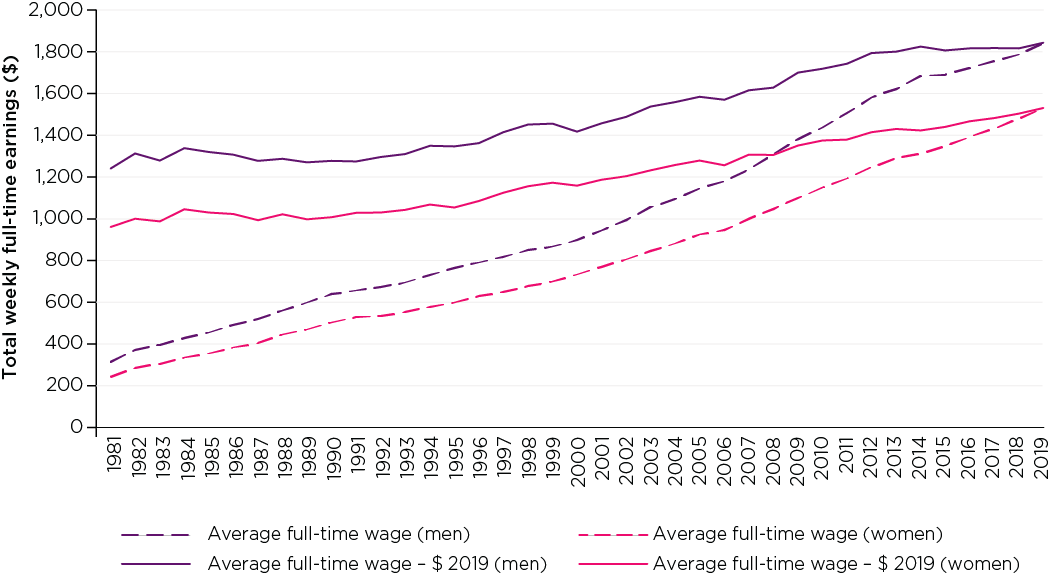

The gender pay gap has narrowed somewhat over the last 40 years. In 1981, average weekly earnings for a man working full-time was $311 (the equivalent of $1,238 in 2019), compared to $241 ($959 in 2019) for a woman who worked full-time. This equates to a gender pay gap of 23% (Figure 1). In 2019, men who worked full-time earned $1,842 per week, on average, compared to $1,529 for women who worked full-time, leaving a gender pay gap of 17%.

Figure 1: Average weekly full-time earnings, men and women, 1981-2019

Note: The dotted lines represent nominal earnings (actual earnings at the time). The solid lines represent earnings adjusted for inflation to 2019 dollars.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2020a)

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2020

Household incomes

Even with the gender pay gap and many women working part-time, household incomes have, on average, increased considerably over the last two decades. In the 2017/18 financial year, the average weekly household income, before tax, was $2,242, up from $1,361 in 1995/96 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average weekly household income (before tax), by household type, 1995/96 to 2017/18

Note: Adjusted for inflation to 2017/18 dollars. Data for 2001/02 were not available. To maintain the two-year intervals, data for 2000/01 and 2002/03 were averaged as an estimate for 2001/02.

Source: ABS (various years - 1996 to 2019)

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2020

Of course, average incomes for couple households will be higher than those of single-parent and single-person households, as many couple households are dual-earner households. Similarly, the average incomes of couples with dependent children are higher than those for couple-only households, as couple-only households have a higher proportion of retirees, while couples with dependent children are more likely to be of working age. This is also the case for single-person households, compared to single-parent households.

With increased rates of unemployment and underemployment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many households have experienced a substantial reduction in income in 2020. Between mid-March to mid-April 2020, 31% of Australians reported that their household finances had worsened due to COVID-19 (ABS, 2020b). The coronavirus supplement for JobSeeker recipients and the introduction of the JobKeeper Allowance have provided a temporary financial buffer for families who have experienced a reduction in income; softening the full impact of COVID-19 on household incomes in 2020.

With increased rates of unemployment and underemployment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many households have experienced a substantial reduction in income in 2020. Between mid-March to mid-April 2020, 31% of Australians reported that their household finances had worsened due to COVID-19 (ABS, 2020b). The coronavirus supplement for JobSeeker recipients and the introduction of the JobKeeper Allowance have provided a temporary financial buffer for families who have experienced a reduction in income; softening the full impact of COVID-19 on household incomes in 2020.

Household net worth increases

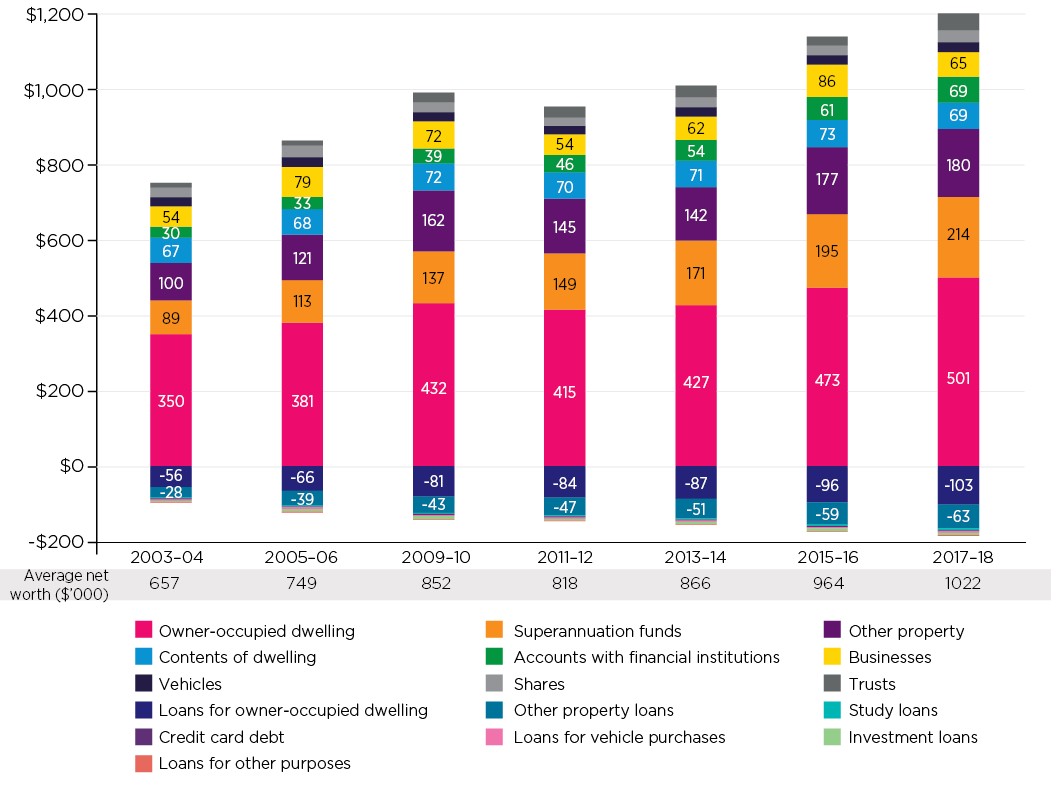

Increases in property values and superannuation savings over the past two decades have meant that household wealth in Australia has increased considerably. Average household net worth has increased from $657,000 in 2003/04 (in 2017/18 dollars) to over one million dollars in 2017/18 (Figure 3).

For most Australian households, property and superannuation are the largest components of household wealth. In 2017/18, the average value of an owner-occupied property was just over $500,000, compared to $350,000 in 2003/04. The number of Australians who owned a rental property has also increased, from 1.4 million in 2003/04 to 2.2 million in 2016/17 (Australian Taxation Office (ATO), 2019). This increase is reflected in the household wealth figures, with the average value of household wealth held as properties other than the principal residence more than doubling between 2003/04 and 2017/18. With the introduction of compulsory employer superannuation contributions in 1992, household-level superannuation savings have also increased, from $100,000 in 1994/95 (adjusted for inflation to 2017/18 dollars) to $180,000 in 2017/18.

Figure 3: Household assets and liabilities, 2003/04 to 2017/18 ($'000)

Note: Adjusted for inflation to 2017/18 dollars.

Source: ABS (2019) 6523.0 - Household Income and Wealth, Australia, 2017-18

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2020

While the value of our assets has increased, our debts have increased too. For most Australian households, the majority of debt is made up of loans for owner-occupied dwellings and investment properties. On average, credit card debt and loans for purposes other than purchasing property make up only a small component of overall household debt. While the average amount of household debt for study loans increased from (the 2017/18 equivalent of) $1,700 in 2003/04 to $5,000 in 2017/18, average household-level credit card debt increased only slightly - from $2,600 in 2003/04 to $3,000 in 2017/18.

There is a considerable amount of uncertainty around household finances as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many Australians have experienced a drop in the value of their superannuation savings as a result of the economic downturn from COVID-19; and some experts are predicting a fall in property values when JobKeeper Allowance, and the six-month deferral of home loan repayments, has ended. Furthermore, over one million Australians have drawn down on their superannuation savings, as part of the temporary early release of superannuation scheme (ASFA, 2020), which is likely to have a long-term impact on retirement savings and living standards in retirement, particularly for younger people.

Men still have more super than women do

Even though superannuation savings at the household level have increased substantially over the last two decades, the gender gap in superannuation savings still remains. Although superannuation has existed in Australia since 1862, it was quite uncommon until the 1970s, when it began to be included in industrial awards. By 1974, 32% of wage and salary earners had some superannuation - 41% of males, but only 17% of females (Warren, 2015).

In the 1970s, superannuation was still concentrated among a minority of employees - generally higher paid white-collar staff in large corporations, employees in the finance sector, public servants and members of the Defence Force. It was not until the introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee in 1992 that superannuation became a major component of Australia's retirement system.

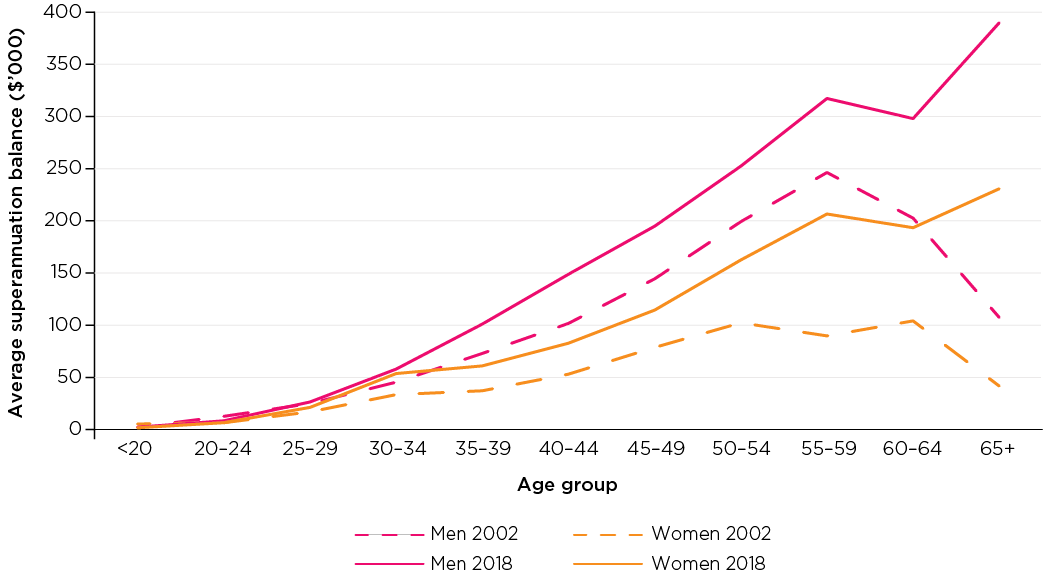

With the maturation of the superannuation guarantee system, average superannuation balances in 2018 are considerably higher than they were in 2002 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average superannuation balances, men and women (not retired), 2002 and 2018

Note: 2002 values adjusted for inflation (reported in $ 2018).

Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, Waves 2 and 18. Sample restricted to people who are not retired and excludes those who have never been employed.

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2020

Before the introduction of compulsory superannuation, women were more likely to be in jobs where their employer did not contribute to a superannuation fund on their behalf. Even with the introduction of compulsory superannuation, women tend to receive lower employer contributions because they are usually based on a percentage of total salary and, on average, women earn less than men. Women are more likely to work part-time and to experience periods of career interruption because of caring responsibilities. These broken work patterns mean that women are often not in the work force for long enough periods to accumulate sufficient superannuation savings. Even when women re-enter the workforce later in life, their superannuation savings accumulate at a slower rate than those who have had an unbroken career path, as they miss out on the benefits of the long-term compounding effect of returns on superannuation savings.

In 2002, the gender gap in superannuation savings became evident at age 30-34. But in 2018, average superannuation savings were quite similar for men and women at age 30-34, with the gap appearing for 35-39 year olds. This is partly due to more women participating in further education and delaying having their first child until a later age, and staying in full-time work longer into their early thirties. Still, even in 2018, the gender gap in superannuation savings was substantial. Among those aged 55-59, men had average balances of almost $318,000, compared to $207,000 for women.

As long as compulsory superannuation is based on income, the gender gap in superannuation savings will continue to exist. However, this does not necessarily mean that women will suffer worse outcomes in retirement. Most Australians approaching retirement are living with a spouse or partner, and for people in couple households the overall level of savings of the couple, in combination with a full or part pension, are generally enough to maintain a reasonable standard of living in retirement (Warren, 2015). In fact, recent research has shown that retirees today feel more comfortable financially than younger Australians who are still working (Daley et al., 2018).

However, financial difficulties can often arise when a relationship ends or when a partner dies. Single-person households, particularly those of single women, have the lowest capacity for self-funding in retirement and are most likely to rely almost entirely on the age pension as their main source of retirement income (Warren, 2015). While the majority of retirees own their home outright, the percentage of retirees who are renting or paying off a mortgage is considerably higher among single women, and it is likely that housing stress will become more of a problem for retirees in decades to come. Estimates by REST Industry Super (2011) indicate that by 2036 one in four retirees will be renters rather than homeowners. With more than one million Australians drawing down on their superannuation savings early to assist with the financial consequences of COVID-19, this is likely to be an even more important issue for single women in the years to come.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1996-2019). Household income and wealth, Australia, 2017-18 (Cat. No. 6523.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020a) Average weekly earnings - States and Australia, 1981-2019 (Cat. No. 6302.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020b). Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, 14-17 Apr 2020 (Cat. No 4940.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO). (2019). Taxation statistics 2016-17. Canberra: ATO. Retrieved from data.gov.au/data/dataset/taxation-statistics-2016-17/resource/ddf6b851-1a59-4b4f-a2f1-802d26b26db2?view_id=a0def95b-9a41-4d8c-ab74-3e277d855d2d

- Daley, J., Coates, B., Wiltshire, T., Emslie, O., Nolan, J., & Chen, T. (2018). Money in retirement: More than enough. Melbourne: Grattan Institute. Retrieved from grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/912-Money-in-retirement-re-issue-1.pdf

- REST Industry Super. (2011). Home ownership and superannuation white paper. Parramatta, NSW: REST Industry Super. Retrieved from www.rest.com.au/getdoc/e9d1fffa-5e49-4979-9546-b7600040b33d/REST-Industry-Super-Home-Ownership-and-Superannuation.

- The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA). (2020). Super funds deliver $9.4 billion in early release financial hardship payments. Sydney: ASFA. www.superannuation.asn.au/media/media-releases/2020/media-release-8-may-2020

- Warren, D. (2015). Historical development and recent reforms in the super challenge of retirement income policy. Melbourne: Centre for Economic Development of Australia. Retrieved from www.ceda.com.au/Research-and-policy/All-CEDA-research/Research-catalogue/The-super-challenge-of-retirement-income-policy

The HILDA project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. The findings and views based on these data are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

Featured image: © GettyImages/Asadnz