Gambling activity in Australia

Findings from wave 15 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey

Download Research report

Executive Summary

This report provides an overview of gambling activity in Australia in 2015, with respect to participation, expenditure, and problems among regular gamblers. The report follows a format and style common to gambling prevalence studies conducted in Australia and elsewhere.

As with those studies, the report is intended as a reference document. It is written primarily for researchers and government officials who have an interest in Australian gambling statistics. This report makes a unique contribution to knowledge of gambling in Australia, since Australia has no prior history of surveying and reporting on gambling activity among regular gamblers at the national level.

The content consists primarily of descriptive statistics with a focus on population estimates. The statistics were obtained from cross-sectional analysis of Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey data, wave 15, which is the first wave to include gambling questions. The HILDA Survey was designed so that participants' responses (17,606 participants in wave 15) could be generalised to the Australian adult population.

The participation statistics include population-representative estimates of the proportion and number of Australians who spent money on up to ten common gambling activities (lotteries, instant scratch tickets, electronic gaming machines, race betting, sports betting, keno, casino table games, bingo, private betting and poker) in a typical month of 2015. The report refers almost entirely to these gamblers, which we refer to as regular gamblers.

Chapter 1 of this report provides the background to the study and details regarding study design and methodology. Chapters 2 and 3 respectively provide statistics regarding typical gambling participation and expenditure. Chapters 4 and 5 address participation and expenditure among adults who experienced gambling-related problems. In Chapter 6 gambling expenditure is positioned within the household budgets of low, middle and high-income households. As well, rates of financial stress are compared between households that contain members with and without gambling problems. Additional tables, including a comparison of the HILDA Survey gambling statistics with recent state/territory and national prevalence data and industry revenue data, can be found in the Appendices.

The report identifies an estimated 6.8 million regular gamblers in 2015, among whom lottery participation was very common (76%). Instant scratch tickets (22%) and electronic gaming machines (EGMs; 21%) followed, attracting 1.4 to 1.5 million gamblers. Less than a million gambled regularly on anything else, including racing (14%), sports betting (8%), keno (8%), casino table games (3%), bingo (3%), private betting (2%) and poker (2%). It was common for people to participate either solely in lotteries (59%), or a combination of lotteries and up to two additional activities.

While lotteries and instant scratch tickets were the most popular activities, individual gamblers spent comparatively little on these activities in a typical month, and therefore over the entirety of the year ($695 and $248 per year on average). Those who gambled on Electronic Gaming Machines spent a great deal more per year ($1,292 on average). So too did those who regularly gambled on races ($1,308), sports ($1,032), casino table games ($1,369), and particularly poker ($1,758).

Regular gamblers, viewed by activity, have quite different profiles. For example, compared to the Australian population:

- lottery participants were over-represented among older couples living without children;

- EGM participants were over-represented among people for whom welfare payments formed their main source of income;

- bingo participants were over-represented among retired women living alone;

- regular race or sports bettors were over-represented among men on higher incomes, yet the race bettors were more likely to be older and live in outer regional/remote areas; and

- sports bettors were more likely to be younger and live in an inner-regional area or major city.

Gambling problems are indicated in the HILDA Survey by endorsing one or more items on the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI). According to the standard use of the PGSI, 1.1 million regular gamblers were estimated to have behaved in ways that caused or put them at risk of gambling-related problems.

Among this subset of regular gamblers, there were more sociodemographic similarities than differences. Those who experienced problems were generally more likely to be young, single, unemployed or not employed (excluding retirees and full-time students), Indigenous, men, living in rental accommodation, in a low socioeconomic area, and were more likely to draw their income from welfare payments than those who had no problems.

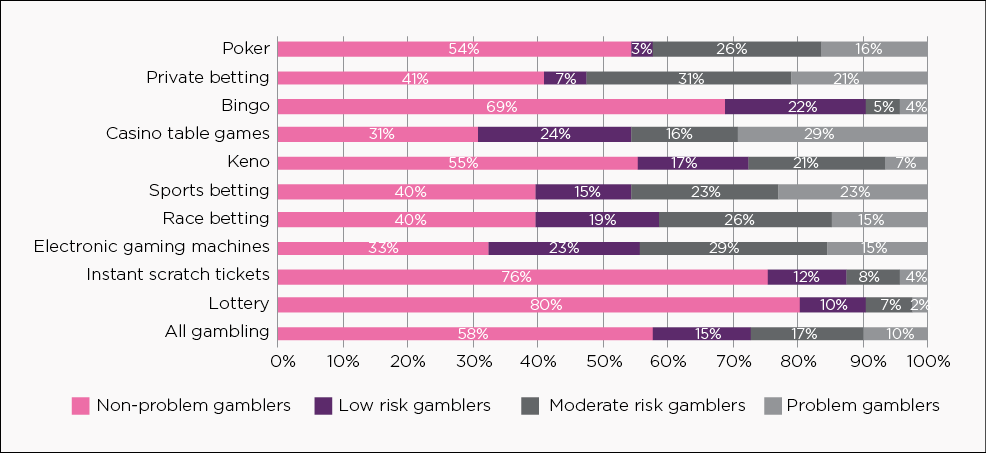

Those with problems were also more likely to participate regularly in certain activities. This led to rates of problems being particularly high among participants in six activities (EGMs, race betting, sports betting, casino table games, private betting, and poker) with almost 1-in-2 gamblers on any of these activities experiencing one or more issues.

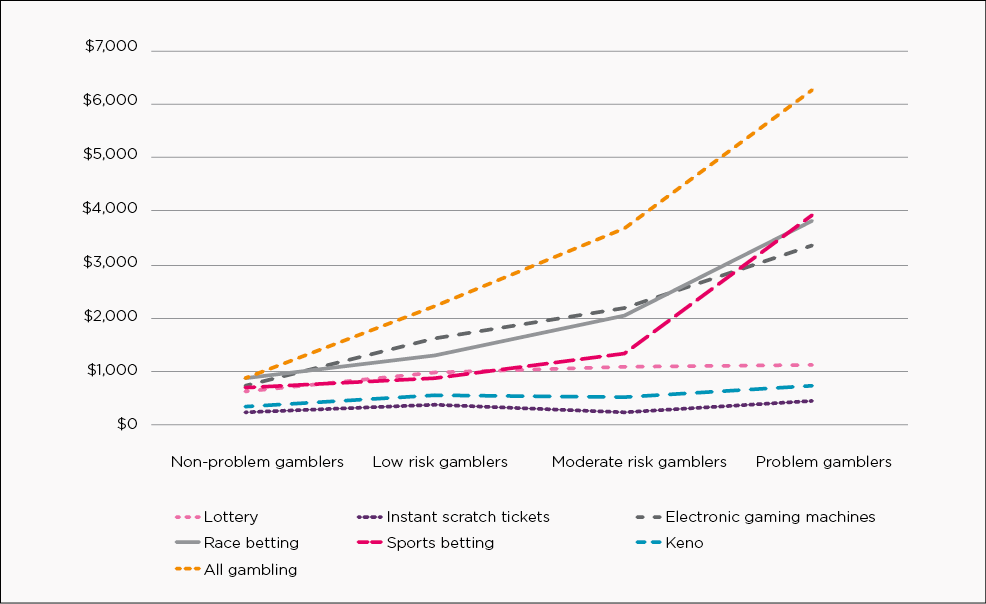

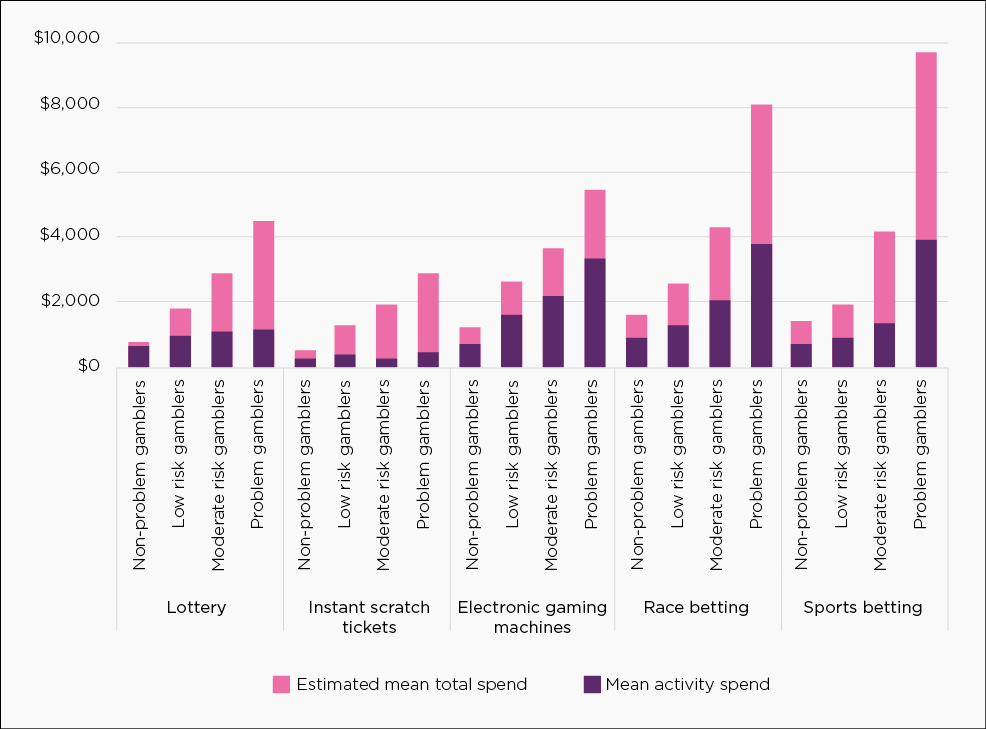

Another thing those with problems had in common was higher than average spending on gambling. This was particularly so among EGM, race and sports betting participants. Those experiencing the greatest problems spent more than four times as much on these activities, and on gambling overall, as those without problems. Well over half of all expenditure by regular gamblers on these activities came from people who had problems.

Overall, more than forty percent of gambling expenditure by regular gamblers, aggregated across all activities, was accounted for by the 17% who experienced problems.

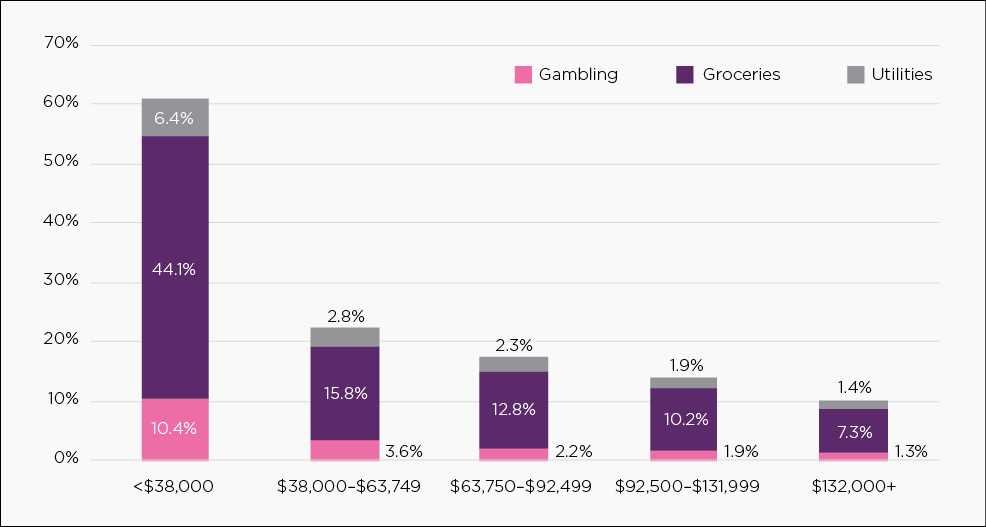

Gambling expenditure has significant financial ramifications for low-income households, particularly among households where gamblers experienced problems. Gamblers living in low-income households spent a much greater proportion of their household's total disposable income on gambling than high-income households (10% vs 1% on average) - this despite spending less in actual dollar terms ($1,662 vs $2,387).

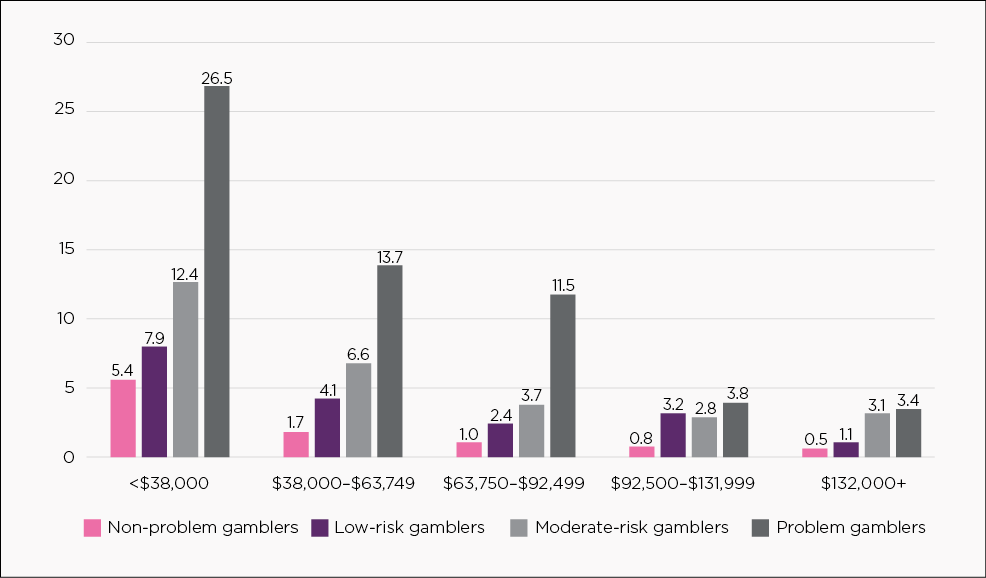

Gamblers who had problems spent much more of their households' income on gambling than other regular gamblers, with those experiencing severe problems in low-income households spending an average 27% of their disposable household income on gambling - equivalent to four times their yearly household utility bills, or more than half the grocery bills for that income group.

Consistent with these patterns of expenditure, the households of those with gambling problems had a much greater proportion of stressful financial events. Inability to pay electricity, gas or telephone bills on time, and needing to ask friends or family for financial help, were common occurrences.

Future waves of the HILDA Survey will provide nationally representative longitudinal data with which to measure changes in gambling activity and effects on individuals and their households.

Glossary

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Bingo | A game in which players mark off numbers on cards as the numbers are drawn randomly, the winner being the first person to mark off all their numbers. |

| Casino table games | Casino games played at a table including roulette, craps and card games such as black jack and baccarat. Tables games usually involve a dealer and participants wager on the outcome of the game. |

| Expenditure (participant net loss / operator gross profit) | The net amount spent/lost or, in other words, the amount wagered less the amount won, by people who gamble. Conversely, by definition, it is gross profit (or gross winnings) due to the operators of each particular gambling activity. |

| Electronic Gaming Machines (EGMs) | Also known as "slots', "pokies', "poker machines" and "fruit machines'. EGMs usually have three or more computer-simulated reels which "spin" when a button is pushed. When winning symbols line up a prize is awarded. |

| Equivalised household disposable income | The total income of a household, after personal income tax and Medicare levy deductions, that is available for spending or saving, divided by the number of household members converted into equalised adults using the OECD equivalence scale. |

| Household composition | Single adult household (one adult aged 15 or more); Couple only household (2 persons aged 15+ who identify as a couple), Household with children (one or more adults aged 15+ living with one or more children aged less than 15); Multiple adult household (2 or more persons aged 15+, excluding couple only households). |

| Household income quintile | Households grouped according to total household income, from lowest to highest, with approximately 20% of households in each group. |

| Gambling | The placement of a wager or bet on the outcome of a future uncertain event. Participation may occur online or offline. The statistics presented in this publication include but are not limited to legalised regulated gambling activities operated by Australian businesses. They include for instance, private betting and in-play sports betting on offshore sites. |

| Gambling problems | Gambling problems are indicated by endorsing one or more items on the Problem Gambling Severity Index. The items include gambling behaviours that either caused or put people at risk of problems. |

| Grocery expenditure | Total household expenditure on food, cleaning products, pet food and personal care products. Does not include alcohol or tobacco. |

| Instant scratch tickets | Commonly known as "scratchies", where a player scratches a coating off the ticket to identify whether the ticket is a winner. |

| Keno | Keno is a rapid-draw game where a player gambles that their chosen numbers match any of the 20 numbers randomly selected from a group of 80 numbers via a computer system or a ball-draw device. |

| Lotto or lottery games | Common lotto or lottery games include Tattslotto, Gold Lotto, Lotto, X-Lotto and Powerball. Lotto is a game where a player selects any six numbers from 1 to 45 in anticipation that those numbers will be among eight numbered balls, randomly drawn from a ball-draw device containing 45 balls numbered from 1 to 45. The first six of the eight balls drawn are known as the "winning numbers" and the last two balls are called "supplementary numbers". Lotteries may also include less defined activities which broadly involve the purchase of a ticket, a draw and a prize. |

| Private betting | This may include unregulated informal betting on games such as cards or mah-jong, or other agreed-upon outcomes, often with friends or family. |

| Poker | Poker refers to a group of card games in which the winner of each hand is determined according to the combinations of players' cards, at least some of which remain hidden until the end of the hand. |

| Race betting | Wagering on the outcome of horse and greyhound races, excluding all sweeps. |

| Regular gamblers | Adults who spent money on one or more gambling activities in a typical month of 2015. |

| SEIFA | Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) ranks areas in Australia according to relative socio-economic advantage and disadvantage. The indexes are based on information from the five-yearly Census. |

| Sports betting | Wagering on local, national or international sporting activities (other than horse and greyhound racing). |

| Significant difference (statistical) | A difference that is highly unlikely due to chance. |

| Utility expenditure | Total household expenditure on electricity bills, gas bills and other heating fuel such as firewood and heating oil. Does not include water, telephone or internet bills. |

| Weighted data | Data collected from survey participants are adjusted to represent the population from which the sample was drawn. For instance, data from the 17,606 wave 15 HILDA Survey participants are adjusted so that together they represent the total population of Australia. |

Key Findings

Chapter 2: Participation

- According to population estimates from the HILDA Survey, 6.8 million or 39% of Australian adults gambled in a typical month of 2015. They are referred to here as regular gamblers.

- Among the 6.8 million gamblers, participation in lotteries was most common (76%), followed by instant scratch tickets (22%) and electronic gaming machines (EGMs) (21%).

- Compared to the Australian adult population, regular gambling participants were substantially over-represented among males (i.e., 54% of gamblers were males versus 49% of Australian adults), people aged 50 and older, those who had ten years or less schooling or had completed a certificate/diploma, people who were retired, who lived alone or with their partner and no others, who lived outside a major city, and those who drew on welfare as their main source of income.

- There were wide-ranging sociodemographic differences between those who gambled regularly on each activity and the Australian adult population.

Chapter 3: Expenditure

- Typical monthly expenditure by the 6.8 million regular gamblers amounted to an estimated $8.6 billion dollars nationally for 2015. Lotteries (42%), EGMs (21%) and race betting (15%) accounted for most of this.

- Regular gamblers' average past-year expenditure was an estimated $1,272. Poker participants recorded the highest mean product expenditure ($1,785) and instant scratch tickets the lowest ($248).

- Gamblers generally spent around half their overall gambling outlay on a single product. Lotteries (79%) and keno (32%) were exceptions, accounting for substantially more and less of their respective participants' overall outlays.

- Mean expenditure was significantly higher than average among gamblers who were male, had completed schooling no further than year 10, were employed full-time, single, and lived with multiple adults. It was lower among gamblers who had a university degree, and lived in a house with children.

Chapter 4: Gambling problems and participation

- As measured using the PGSI, an estimated 7.9% or 1.39 million Australian adults had experienced one or more gambling-related problems in 2015. That is, their gambling behaviour caused or put them at risk of gambling problems. This included 1% or 193,000 who could be classified as "problem gamblers" - the most severe category.

- 80% of those who had experienced problems in the past year had gambled in a typical month of 2015

(i.e., regularly). - Much higher proportions of low-risk, moderate-risk and problem gamblers participated in EGMs, race betting, and sports betting, compared to non-problem gamblers. Problem gamblers also had much higher participation rates than any other group in casino table games (20%), poker (20%), and private betting (13%).

- Compared to non-problem gamblers, those who experienced problems were over-represented among people who were male, aged 18 to 29, Indigenous, were unemployed, or not employed (excluding students and retirees), single, renting, lived in a low socioeconomic area, had a low income, and drew their main source of income from welfare payments. They were under-represented among those who owned their own home, retirees, university graduates, and those who drew their main source of income from superannuation or investments.

Chapter 5: Gambling problems and expenditure

- Gamblers who had problems (i.e., the combined low-risk, moderate-risk and problem gamblers), representing 17% of regular gamblers, accounted for nearly half of all expenditure by regular gamblers in 2015 ($3.63b or 42%), and more than half of all expenditure by regular gamblers across EGMs, race betting, sports betting, casino table games and private betting (59-69%).

- Regular gamblers' mean expenditure was higher among adults in higher risk groups. Non-problem gamblers averaged $883 over the year whereas problem gamblers averaged $6,241.

- The strength of the relationship between expenditure and gambler risk status varied markedly across products. Lottery, keno and instant scratch ticket expenditure had the weakest connection. Race betting, EGMs and particularly sports betting expenditure had the strongest.

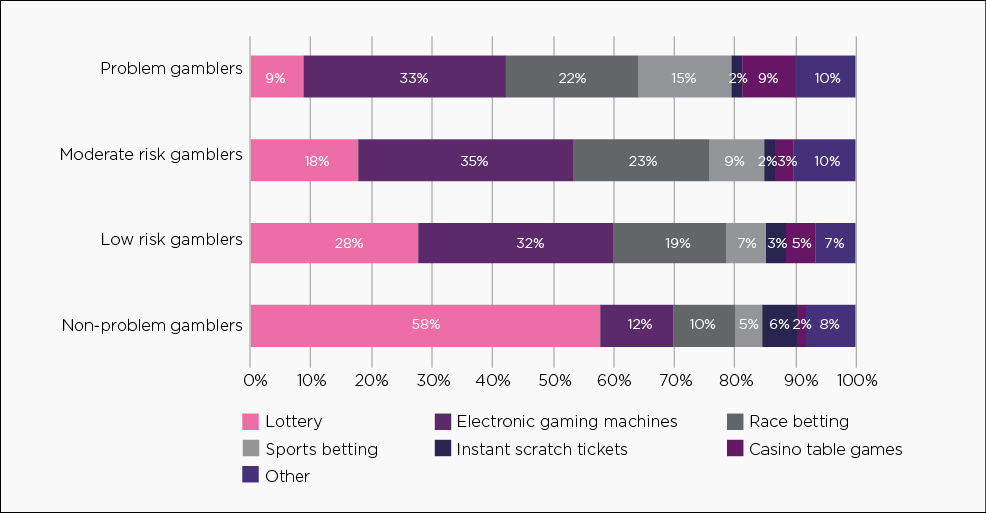

- Higher risk gamblers were likely to spend more on gambling overall, and spread their outlay over a range of activities rather than a single activity. Lower risk gamblers spent less overall and on fewer products.

Chapter 6: Gambling and the household budget

- Gamblers living in low-income households spent, on average, a much greater proportion of their household's total disposable income on gambling than high-income households (10% vs 1%) - this despite spending less in actual dollar terms ($1,662 vs $2,387).

- Higher risk gamblers spent greater proportions of their household's disposable income on gambling. Problem gamblers in low income households spent the greatest proportion (27%) - equivalent to four times the average yearly household utility bills, and more than half the grocery bills, of that income group.

- Households containing higher risk gamblers experienced a much larger proportion of stressful financial events than those containing non-problem gamblers. The most common were an inability to pay electricity, gas or telephone bills on time, and needing to ask friends or family for financial help.

1. Introduction

Background

Gambling is a common activity in Australia. Most adults participate at least once a year. The most recent gambling surveys put the national annual participation rate at around 64% (Dowling et al., 2016; Hing et al., 2014) and between 55-74% across the states and territories (Office of Economic and Statistical Research, 2012; Davidson et al., 2016; The Social Research Centre, 2013; Stevens et al., 2017; Sproston et al., 2012; ACIL Allen Consulting et al., 2014; Hare, 2015).

The gambling activities that Australians prefer are changing. Compared to two decades ago, far fewer now participate in activities that emphasise chance, including lotteries, scratch tickets, keno and Electronic Gaming Machines (EGMs). Much greater numbers now participate in activities that emphasise skill and experience in predicting the outcome, including some casino table games, horse and dog racing and especially sports (Armstrong et al. 2017).

The amount spent is substantial. In 2014/15, Australians gambled $191 billion and lost $22.7 billion across the range of available activities. This equates to $1,242 spent for every person aged 18 and over (Queensland Government Statistician's Office, 2016).

It means that, per capita, Australian adults are the largest spenders on gambling in the world, at around double the average of other Western countries (The Economist online, 2014, 2011, 2017).

Many see and experience gambling as a form of leisure and recreation. However, gambling can have serious repercussions for individuals, their families and society as a whole (Abbott et al., 2015). Between 5-12% of Australians are estimated to experience one or more gambling problems annually (Dowling et al., 2015; Hing et al., 2014), with rates ranging similarly widely across the states and territories (Office of Economic and Statistical Research, 2012; Davidson et al., 2016; The Social Research Centre, 2013; Stevens et al., 2017; Sproston et al., 2012; ACIL Allen Consulting et al., 2014; Hare, 2015). The burden of harm associated with these problems has been estimated to be of a similar magnitude to depressive disorder and alcohol misuse and dependence (Browne et al., 2016).

While numerous cross-sectional state/territory and some national gambling surveys have been performed, there was until recently no ongoing population-level survey of Australian gambling activity and the socio-economic characteristics of gamblers and their families. Longitudinal data with which to measure change over time in gambling activity and effects on individuals and families was similarly absent.

Inclusion of a gambling activity module within the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (HILDA) is intended to address this need. HILDA is a nationally representative longitudinal panel study of Australian households which commenced in 2001. It provides data on a wide range of aspects of life around family dynamics, economic and subjective well-being and labour market dynamics.

Gambling questions were included for the first time in wave 15, connecting gambling activity in 2015 to these broad areas of life. The module comprises two components. The first measures the amount of expenditure on 10 different gambling activities during a "typical month"1. The focus on a "typical month" ensures the focus is on regular gambling, and thus effectively excludes the occasional or once-off expenditure.

The second component comprises the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI; Ferris & Wynne, 2001) This includes nine questions used to identify people whose gambling behaviour caused them problems or put them at risk of problems, on a continuum of increasing severity.

The 12th annual statistical report of the HILDA Survey (Wooden and Wilkens, 2017) presented some initial findings in the chapter dedicated to gambling. They found that 39% of Australian adults participated in gambling activities in a typical month, with an average expenditure of $115 per month. As with previous studies, the HILDA Survey shows males are not only more likely to gamble, but they spend more on average and are more likely to experience gambling-related problems. While lottery was the most common activity, problem gambling is more common among participants in poker, electronic gaming machine users, and race and sports bettors. Most notably, while higher income and full-time employment were significant indicators of participation in gambling and of higher expenditure, it is the unemployed who are at greatest risk of developing problem gambling behaviours.

The intention of this report is to build on this work and provide a more detailed overview of gambling activity in Australia in 2015, in terms of participation, expenditure, and gambling problems among regular gamblers, as drawn from the HILDA self-report survey. The report follows a format and style common to gambling prevalence studies conducted in Australia and elsewhere. As with those studies, the report is intended as a reference document. It is written primarily for researchers and government officials who have an interest in Australian gambling statistics.

Overview of study design

Sample and response

The HILDA Survey commenced in 2001 with a nationally-representative sample of Australian households (residents in private dwellings).2 Wave 1 included 11,693 households, sampled from 488 areas across Australia, with members of 7,682 households, or 13,969 individuals, completing interviews. In wave 11 (2011), the sample was topped up with an additional 2,153 households (5,477 individuals) to address the issue of recent arrivals to Australia being under-represented in the HILDA sample.

This report focuses on data from the wave 15 survey which included a gambling question module for the first time. The fieldwork for wave 15 occurred between 28 July 2015 and 7 February 2016, with 98% of fieldwork completed by 31 December 2015. Wave 15 comprised 8,865 fully responding or 9,631 fully and partially responding households, comprising 17,606 responding individuals.

The gambling module formed part of the Self-Completion Questionnaire (SCQ), a paper form administered to every member of each household aged 15 years and over. The SCQ includes questions the respondents may prefer to not disclose in the presence of an interviewer or other household members. The response rate for these was 88%, with 15,245 persons responding to the gambling module.3

Gambling module

The gambling module consisted of two components relating to participation and problems. Participants were first asked whether they spent money on 10 gambling activities in a typical month, and roughly how much on average they spent on each (Table 1.1). Respondents were considered to be "activity participants" if they responded "yes" to the question of whether they spent money on the activity, even if their expenditure estimate was missing. However, only those with valid expenditure responses were included in expenditure calculations. Missing responses for "any expenditure in a typical month" on a given activity were coded to "no" for those participants who had replied "yes" to other activities. Participants with missing responses on all gambling expenditure questions were excluded from analysis.

In a typical month, roughly how much do you spend on the following activities? This includes money spent on-line (on a computer, mobile/smart phone, iPad etc.). If you are unsure, please make your best guess.

| Any expenditure on a typical month? | How much per month? (On average) | |

|---|---|---|

| Instant scratch tickets ("scratchies") | No/Yes | $ |

| Bingo | No/Yes | $ |

| Lotto or lottery games, like Powerball or Oz Lotto | No/Yes | $ |

| Keno | No/Yes | $ |

| Private betting (e.g., playing cards or mah-jong with friends and family) | No/Yes | $ |

| Poker | No/Yes | $ |

| Casino table games (e.g., blackjack, roulette) | No/Yes | $ |

| Poker machines ("pokies") or slot machines | No/Yes | $ |

| Betting on horse or dog races (but not sweeps) | No/Yes | $ |

| Betting on sports | No/Yes | $ |

The second component consisted of the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI; Ferris and Wynne 2001). The PGSI consists of nine items that capture problematic gambling behaviour in the past 12 months, and the adverse consequences of gambling experienced in the past 12 months4. These items are shown in Table 1.2. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, where 0 = Never and 3 = Almost always. Responses are summed to give a score between 0 and 27. The higher the score, the greater the problems or likelihood of problems.

Now thinking about the last 12 months …

| (Cross X one box on each line) | Never | Sometimes | Most of the time | Almost always |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you bet more than you could really afford to lose? | ||||

| Have you needed to gamble with larger amounts of money to get the same feeling of excitement? | ||||

| When you gambled, did you go back another day to try and win back the money you lost? | ||||

| Have you borrowed money or sold anything to get money to gamble? | ||||

| Have you felt that you might have a problem with gambling? | ||||

| Has gambling caused you any health problems, including stress or anxiety? | ||||

| Have people criticized your betting or told you that you had a gambling problem, regardless of whether or not you thought it was true? | ||||

| Has your gambling caused any financial problems for you or your household? | ||||

| Have you felt guilty about the way you gamble or what happens when you gamble? |

All HILDA Survey participants were administered the PGSI, irrespective of whether they had gambled in a typical month. Each participant was assigned a gambling risk state according to the following risk thresholds:

| PGSI Score | Risk category |

|---|---|

| 0 | Non-problem gambler |

| 1-2 | Low-risk gambler |

| 3-7 | Moderate risk gambler |

| 8 or over | Problem gambler |

Non-problem gamblers were those who did not engage in problematic gambling behaviour or experience adverse consequences in the past 12 months from gambling. Low-risk and moderate-risk gamblers were those who reported low or moderate level problematic behaviour and/or consequences. They are considered as being at low to moderate risk of becoming problem gamblers. Problem gamblers were those who reported high level problematic behaviour and/or consequences.

Statistical analysis

The bulk of the report presents basic descriptive statistics, such as means and percentage distributions. Tables are based on the responding sample for each individual question (i.e., item non-response is excluded), and as such baseline numbers may vary slightly between tables. The sample sizes for each of the gambling activities, and for the categories derived from the PGSI are presented in Appendix B.

Unless otherwise stated, analysis is conducted at an individual responding person level (rather than household) and based on individual's responses. As monetised gambling is illegal under the age of 18, respondents aged 15-17 were excluded from analysis. The exception to this approach is Chapter 6, which addresses gambling expenditure as part of the wider household budget and therefore uses variables constructed from all household members' responses, and includes some analysis conducted at a household level.

Gambling participation and expenditure is analysed according to a set of demographic variables that are expected to be related to gambling behaviours. Some demographic variable percentages may not add to 100% as those which had small categories which did not readily collapse into broader categories are not presented (e.g., participants born outside of Australia, Asia or Europe) but were retained while calculating percentages. For further detail regarding the construction of individual variables for analysis, see Appendix C.

To reduce the impact of outliers on estimates of gambling expenditure, estimates were Winsorised whereby values were capped at the top and bottom 1%. An individual's overall expenditure was calculated by summing the individually capped expenditure values from each of the ten activities.

Standard errors of statistics are not presented in this report, instead estimates which have a relative standard error of between 30% and 50% are marked with # to indicate unreliable estimates and where caution is required when interpreting these estimates. Estimates with a standard error >50% were suppressed, with np (not presented) appearing in place of the estimate.

Confidence intervals for means were calculated at the 95% level, using weighted standard errors. Tests of statistical significance used survey weighted chi-square and t-tests. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA v14.2.

Weighting

In order to generalise findings to the Australian population, HILDA Survey data was weighted to reflect the probability of households and individuals being selected in the complex-cross sectional survey. This report uses the Self-Completion Questionnaire (SCQ) weighting values provided in the HILDA Survey dataset. Details about the weighting process can be found elsewhere (Watson 2012). Throughout the report, these population weights were attached to the 14,453 SCQ respondents aged 18 or above to derive estimates of the proportion and number of adults in the population within each group of interest. Standard errors for weighted data were calculated using the delete-a-group Jackknife method, using replicate weights provided in the HILDA Survey dataset. Details are available elsewhere (Hayes 2008).

Comparison of HILDA data to other gambling statistics

Appendix A provides comparisons of the estimates produced from the HILDA data to estimates produced from other national and state/territory sources. There is considerable variation across data sources in respect to estimates of gambling participation and gambling expenditure. The key contributing factor to those differences is the focus on gambling "in a typical month" in HILDA, and so excluding less regular participation and expenditure. There is also considerable variation in rates of gambling problems. This is because the HILDA Survey administered the PGSI to a population representative sample, whereas gambling studies have only administered it to people who gambled in the past year.

1 The design of these gambling questions was undertaken in collaboration with the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research at the University of Melbourne and Australian Government Department of Social Services.

2 The survey was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Melbourne (1647030).

3 Further details on the structure of the HILDA Survey sample, including complete questionnaires, are available online: <https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda>.

4 Whereas PGSI behavioural items refer to actions in the past twelve months, the adverse consequences reported in the past twelve months may be the legacy of prior problematic gambling behaviours. E.g., gambling-related financial hardship experienced in the past 12 months may be a consequence of gambling behaviour in prior years.

2. Gambling participation

Introduction

This chapter presents estimates of the prevalence of Australian adults (aged 18 years or over) who participated in one or more of 10 gambling activities in a typical month of 2015. People were considered to have participated, and to have been regular gamblers, if they spent money on a given activity in a typical month during the year. The report refers almost entirely to these gamblers. Less frequent gambling participation was not asked about in the HILDA survey. Estimates of the amounts spent on the 10 activities are the focus of Chapter 3.

The 10 activities include lotteries, instant scratch tickets, electronic gaming machines (EGMs), race betting, sports, keno, casino table games, bingo, private betting and poker.

Also estimated is the number of activities in which people typically participated, and the proportions of participants who engaged in each combination of activities.

Finally, participants in each activity are profiled and compared to the Australian adult population on a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics.

Key findings

- An estimated 39% of Australian adults - 6.8 million people - gambled in a typical month of 2015 (i.e., regularly).

- Among these 6.8 million regular gamblers, participation in lotteries was most common (76%), followed by instant scratch tickets (22%) and electronic gaming machines (21%).

- Approximately one third (38%) of gamblers participated in multiple activities.

- Compared to the Australian adult population, regular gambling participants were substantially over-represented among males (i.e., 54% of gamblers were males versus 49% of Australian adults), people aged 50 and older, those who had 10 years or less schooling or a certificate or diploma, people who were retired, who lived alone or with another adult, who lived outside a major city, and those who drew their main source of income from welfare payments.

- There were wide-ranging sociodemographic differences between those who gambled regularly on each activity and the Australian adult population.

Gambling participation

In a typical month of 2015, population weighted HILDA Survey estimates indicate that 39% of Australian adults gambled on one or more of the 10 activities listed in Table 2.1. Among these "regular gamblers", lottery participation was most common (76%). Other commonly reported activities were the regular purchase of instant scratch tickets (22%) and playing of electronic gaming machines (EGMs; 21%). Least likely to be a typical monthly event were casino table gambling, bingo, private betting and poker, with participation rates of 2-3% among those who gambled.

| Activity | Estimated number | Australian population | Regular gambling population |

|---|---|---|---|

| '000 | % | % | |

| Lottery | 5,186 | 29.6 | 76.2 |

| Instant scratch tickets | 1,495 | 8.5 | 22.0 |

| EGMs | 1,418 | 8.1 | 20.8 |

| Race betting | 975 | 5.6 | 14.3 |

| Sports betting | 574 | 3.3 | 8.4 |

| Keno | 549 | 3.1 | 8.1 |

| Casino table games | 192 | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| Bingo | 186 | 1.1 | 2.7 |

| Private betting | 155 | 0.9 | 2.3 |

| Poker | 132 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| Any gambling | 6,809 | 38.9 | 100.0 |

Notes: Percentages based on weighted data. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Number of gambling activities

Table 2.2 shows the proportion of adults who participated in one or more of the 10 gambling activities in a typical month.

The survey found that almost one quarter (24%) of Australian adults spent money on a single activity in a typical month, while 15% participated in multiple activities. Among those who gambled, 38% spent money on more than one activity.

| Australian population | Regular gambling population | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of activities | % | % |

| 0 | 61.7 | - |

| 1 | 23.6 | 61.6 |

| 2 | 9.3 | 24.2 |

| 3 | 3.7 | 9.8 |

| 4+ | 1.7 | 4.4 |

Notes: Statistics based on weighted data. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Tables 2.3 and 2.4 show the proportion of gamblers who participated in each single activity, the mean number of activities that participants in each activity engaged in, and the proportion who engaged in additional activities. In these tables, the most common activity combinations in a typical month can be seen.

Most lottery participants (59%) gambled solely on that activity in a typical month. Gamblers who participated in any other activity usually participated in one or two additional activities (2.3 to 3.4 on average), and included lottery in the mix. For instance, as shown in Table 2.3, keno participants very rarely spent money on that activity alone (only 10% did). They usually spent money on three activities (2.9 on average). As shown in Table 2.4, the additional activities were most commonly the lotteries, which two thirds of keno players participated in regularly (67%), and EGMs, which half played regularly (48%).

| Participants in… | This activity only (%) | Mean number of activities |

|---|---|---|

| Lottery | 59.3 | 1.63 |

| Instant scratch tickets | 19.0 | 2.32 |

| EGMs | 25.4 | 2.46 |

| Race betting | 17.5 | 2.65 |

| Sports betting | 17.4 | 2.82 |

| Keno | 10.2 | 2.90 |

| Casino table games | 20.4 | 3.05 |

| Bingo | 28.0 | 2.71 |

| Private betting | 20.1 | 3.36 |

| Poker | 19.9 | 3.21 |

| Any gambling | 61.6 | 1.59 |

Notes: Statistics based on weighted data. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

| Participation rate in other activities (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lottery | Instant scratch tickets | EGMs | Race betting | Sports betting | Keno | Casino table games | Bingo | Private betting | Poker | |

| Lottery | - | 20.6 | 14.6 | 10.1 | 5.1 | 7.1 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Instant scratch tickets | 71.5 | - | 24.7 | 10.3 | 6.9 | 9.6 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| EGMs | 53.3 | 26.1 | - | 20.1 | 10.8 | 18.7 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Race betting | 53.6 | 15.8 | 29.2 | - | 33.4 | 15.4 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 2.9 |

| Sports betting | 46.0 | 17.9 | 26.6 | 56.7 | - | 12.3 | 7.6 | 2.3 | 7.9 | 5.0 |

| Keno | 67.2 | 26.1 | 48.2 | 27.3 | 12.8 | - | 3.7 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 4.7 |

| Casino table games | 39.6 | 18.2 | 39.7 | 29.7 | 22.9 | 10.7 | - | 9.1 | 18.6 | 16.2 |

| Bingo | 50.8 | 24.2 | 36.7 | 16.7 | 7.1 | 13.6 | 9.4 | - | 9.2 | 2.9 |

| Private betting | 51.2 | 20.7 | 29.2 | 32.8 | 29.1 | 14.0 | 23.0 | 11.0 | - | 25.4 |

| Poker | 47.6 | 17.4 | 36.0 | 21.8 | 21.8 | 19.7 | 23.7 | 4.1 | 30.0 | - |

Notes: Percentages based on weighted data. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding

Sociodemographic characteristics of regular gamblers

Table 2.5 shows the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of regular gamblers in 2015. Their characteristics are compared to the Australian adult population.

Compared to the Australian adult population, a significantly higher proportion of regular gamblers were male. That is, 49% of Australian adults were male whereas 54% of regular gamblers were male. Regular gamblers were further over-represented among people aged 50 and older, those born in Europe, those who had 10 years or less schooling, or had certificate or diploma, people who were retired, who lived alone or with only their partner, who lived outside a major city, and those who drew their main source of income from welfare payments.

Note that the proportions provided in Table 2.5 can be used to estimate the national gambling participation rates for each demographic group, such as the percentage of Australians who were male gamblers. For example, we know that 38.9% of Australians were regular gamblers (Table 2.1), of whom 54.2% were male (Table 2.5). Therefore, 21% (54.2% of 38.9%) of Australians were male gamblers in 2015.

| Australian adults | Regular gamblers | |

|---|---|---|

| Subpopulation categories | % | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 49.0 | 54.2↑ |

| Female | 51.0 | 45.8↓ |

| Age group | ||

| 18-29 | 22.5 | 11.9↓ |

| 30-49 | 34.9 | 34.0 |

| 50-64 | 24.1 | 30.4↑ |

| 65+ | 18.6 | 23.8↑ |

| Indigenous Status | ||

| Non-Indigenous | 97.7 | 97.6 |

| Indigenous | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Region of birth a | ||

| Australia | 69.7 | 71.9↑ |

| Europe | 10.8 | 11.9↑ |

| Asia | 10.7 | 7.3↓ |

| First Language spoken | ||

| English | 85.6 | 90.3↑ |

| Other | 14.4 | 9.7↓ |

| Highest education Level | ||

| Below year 10 | 8.1 | 9.2↑ |

| Completed year 10 | 15.3 | 19.0↑ |

| Completed year 12 | 15.8 | 13.0↓ |

| Certificate or diploma | 33.1 | 37.9↑ |

| Bachelors or higher | 27.7 | 20.9↓ |

| Employment | ||

| Employed full-time | 43.6 | 47.4↑ |

| Employed part-time | 20.1 | 16.3↓ |

| Unemployed-looking for work | 3.2 | 2.3↓ |

| Retired | 19.7 | 25.0↑ |

| Full-time student | 3.4 | 1.2↓ |

| Other not employed-not looking for work | 9.9 | 7.9↓ |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married/in a de facto relationship | 54.6 | 59.5↑ |

| Single | 45.4 | 40.5↓ |

| Household composition | ||

| Single adult household | 12.3 | 14.1↑ |

| Couple only household | 24.4 | 28.6↑ |

| Household with children | 30.3 | 25.6↓ |

| Multiple adult household | 33.0 | 31.7 |

| Housing tenure | ||

| Own outright | 17.3 | 18.3 |

| Own with mortgage | 52.7 | 53.3 |

| Rent | 27.7 | 26.0 |

| Remoteness | ||

| Major city | 72.5 | 69.1↓ |

| Inner regional | 18.2 | 20.0↑ |

| Outer regional/remote | 9.3 | 11.0↑ |

| SEIFA quintile b | ||

| Lowest | 19.6 | 19.7 |

| 2 | 18.2 | 19.6↑ |

| Middle | 19.3 | 19.8 |

| 4 | 20.6 | 20.0 |

| Highest | 22.4 | 21.0↓ |

| Equivalised disposable household income c | ||

| <$29,500 | 19.8 | 19.3 |

| $29,500-$41,499 | 20.4 | 19.4 |

| $41,500-$53,999 | 19.4 | 20.2 |

| $54,000-$73,499 | 20.2 | 20.8 |

| $73,500+ | 20.2 | 20.3 |

| Main source of household income | ||

| Wages/salary/business | 73.5 | 70.3↓ |

| Govt. pension/allowance/benefit | 18.2 | 20.7↑ |

| Superannuation/annuity/investment | 8.1 | 8.7 |

Notes: Percentages based on weighted data. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding or non-response.

a Only region of origins representing >10% of the population are presented. b Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas 2011. c Household income after tax, weighted for size and composition of household. ↑ and ↓ are used to indicate values significantly above or below the general Australian population at p<.05.

Sociodemographic characteristics of regular gamblers by activity

Table 2.6 provides a sociodemographic breakdown of participants in each of the 10 activities. Their characteristics are compared to the Australian adult population.

As shown in the table, there were many significant sociodemographic differences between the activity participants and the Australian population. Given the large number of significant differences, only those which were considered substantial are described below.5

Lotteries. Compared to the Australian adult population, a substantially higher proportion of lottery participants were aged 50 and over. That is, while 43% of Australian adults were aged 50 and over, a much larger percentage (58%) of lottery players were aged 50 and over. A substantially higher proportion were also born in Europe, had 10 years or less of schooling or had completed a certificate or diploma, were retired, married/in a de facto relationship, and lived with only their partner.

Instant scratch tickets. A substantially higher proportion of participants were aged 50 and older, had 10 years or less of schooling, were retired, lived alone or with only their partner, and lived outside of a major city.

Electronic gaming machines. EGM players were substantially over-represented among those aged 50 and older, people who identified as Indigenous, who had 10 years or less of schooling or had completed a certificate or diploma, were retired, lived alone or with only their partner, lived in an inner regional area, those who had lowest incomes, and those who drew their main source of income from welfare payments.

Race betting. A substantially higher proportion of race bettors were male, aged between 50 and 64, born in Australia, had 10 years of schooling or had completed a certificate or diploma, were employed full-time, lived alone or with only their partner, and lived in an outer regional or remote area. Race bettors were further over-represented among those with the highest incomes.

Sports betting. Relative to the Australian adult population, a substantially higher proportion were male, younger than 50, Indigenous, born in Australia, had 12 years of schooling, were employed full-time, single, had the highest incomes, and drew their main source of income from employment.

Keno. Participants were substantially over-represented among males, people aged 30 and older, those who identified as Indigenous, had 10 years or less of schooling or had completed a certificate or diploma, were retired, lived alone, lived outside a major city, lived in a low socioeconomic area, and those who drew their main source of income from welfare payments.

Casino table games. A substantially higher proportion of participants were male, younger than 30, Indigenous, had 12 years of schooling, were employed full-time, single, lived with multiple adults, lived in a major city, lived in a high socioeconomic area, and drew their main source of income from employment.

Bingo. Compared to the Australian population, a substantially higher proportion of participants were female, aged 65 and over, had 10 years or less of schooling, were retired or not employed and not looking for work, lived alone, lived in the lowest socioeconomic areas, had the lowest incomes, and drew their main source of income from welfare payments.

Private betting. Participants were substantially over-represented among males, people born in Asia, and those who owned their own home with a mortgage.

Poker participants. Relative to the Australian adult population, a substantially higher proportion of poker players were male, did not have a university degree, were employed full-time, lived with multiple adults, and drew their main source of income from employment.

Note that the proportions provided in Table 2.6 can be used to estimate national regular gambling participation rates for each demographic group. For example, we know that 3.3% of Australians were regular sport bettors (Table 2.1), of whom 88% were male (Table 2.6). Therefore, 2.9% (88% of 3.3%) of Australians were male sports bettors and 0.4% (12% of 3.3%) of Australians were female sports bettors.

The table can also be viewed on pages 16–18 of the PDF.

| Australian adults | Lottery | Instant scratch tickets | EGMs | Race betting | Sports betting | Keno | Casino table games | Bingo | Private betting | Poker | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subpopulation Categories | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 49.0 | 52.8↑ | 45.3↓ | 54.3↑ | 80.9↑ | 88.0↑ | 60.2↑ | 76.6↑ | 19.3↓ | 62.9↑ | 65.8↑ |

| Female | 51.0 | 47.2↓ | 54.7↑ | 45.7↓ | 19.1↓ | 12.0↓ | 39.8↓ | 23.4↓ | 80.7↑ | 37.1↓ | 34.2↓ |

| Age group | |||||||||||

| 18-29 | 22.5 | 6.2↓ | 12.5↓ | 16.1↓ | 15.5↓ | 32.7↑ | 10.0↓ | 46.2↑ | 8.0#↓ | 22.5 | 30.2 |

| 30-49 | 34.9 | 35.8 | 30.5↓ | 25.3↓ | 34.9 | 42.4↑ | 39.7 | 30.8 | 23.6 | 44.0 | 41.2 |

| 50-64 | 24.1 | 33.4↑ | 33.2↑ | 29.6↑ | 31.4↑ | 18.6 | 28.1 | 16.3 | 29.5 | 15.0 | 18.3 |

| 65+ | 18.6 | 24.6↑ | 23.8↑ | 29.0↑ | 18.2 | 6.3↓ | 22.1 | np | 38.9↑ | 18.5# | 10.3# |

| Indigenous status | |||||||||||

| Non-Indigenous | 97.7 | 98.1 | 96.9 | 95.1↓ | 96.4 | 95.4↓ | 94.5↓ | 95.0↓ | 95.0 | 97.1 | 95.5 |

| Indigenous | 2.3 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 4.9↑ | 3.6 | 4.6↑ | 5.5↑ | 5.0#↑ | 5.0# | np | np |

| Region of birth a | |||||||||||

| Australia | 69.7 | 69.7 | 72.8 | 78.1↑ | 80.7↑ | 82.0↑ | 78.8↑ | 68.6 | 65.2 | 59.0 | 63.3 |

| Europe | 10.8 | 13.3↑ | 10.0 | 12.2 | 8.8 | 6.0↓ | 11.9 | 4.0 | 14.6 | 8.4# | 10.3# |

| Asia | 10.7 | 8.0↓ | 6.3↓ | 3.8↓ | 3.6↓ | 3.1#↓ | 3.7↓ | 13.9 | 9.3 | 23.1#↑ | 14.9 |

| First language spoken | |||||||||||

| English | 85.6 | 89.3↑ | 91.2↑ | 94.2↑ | 95.0↑ | 96.6↑ | 95.4↑ | 82.4 | 82.4 | 77.6 | 77.4 |

| Other | 14.4 | 10.7↓ | 8.8↓ | 5.8↓ | 5.0#↓ | 3.4#↓ | 4.6#↓ | 17.6# | 17.6 | 22.4# | 22.6# |

| Highest education level | |||||||||||

| Below year 10 | 8.1 | 9.5↑ | 9.4 | 12.0↑ | 6.2 | 3.4#↓ | 12.5↑ | np | 23.9↑ | 12.8# | 7.6# |

| Completed year 10 | 15.3 | 19.0↑ | 20.4↑ | 21.6↑ | 20.2↑ | 14.7 | 22.1↑ | 14.8 | 29.3↑ | 11.6# | 18.7 |

| Completed year 12 | 15.8 | 11.1↓ | 11.9↓ | 16.5 | 15.8 | 22.0↑ | 13.4 | 27.6↑ | 8.3↓ | 9.8# | 13.3# |

| Certificate or Diploma | 33.1 | 39.1↑ | 36.6 | 38.9↑ | 40.5↑ | 33.3 | 42.3↑ | 34.6 | 28.7 | 36.5 | 45.0 |

| Bachelors or higher | 27.7 | 21.3↓ | 21.7↓ | 11.0↓ | 17.4↓ | 26.6 | 9.8↓ | 20.7 | np | 29.3 | 15.3↓ |

| Employment | |||||||||||

| Employed full-time | 43.6 | 48.7↑ | 43.4 | 38.9↓ | 55.5↑ | 70.4↑ | 47.7 | 59.9↑ | 24.1↓ | 56.7 | 64.7↑ |

| Employed part-time | 20.1 | 15.9↓ | 17.7 | 17.1↓ | 15.3↓ | 14.1↓ | 18.3 | 20.6 | 8.4#↓ | 16.8# | 12.6# |

| Unemployed-looking for work | 3.2 | 2.0↓ | 2.4 | 4.2 | 2.8# | 2.0# | 4.0 | 3.4# | 2.5# | np | np |

| Retired | 19.7 | 25.3↑ | 25.5↑ | 31.0↑ | 19.8 | 7.3↓ | 23.6↑ | np | 46.7↑ | 13.3# | 6.4#↓ |

| Full-time student | 3.4 | 0.4↓ | 1.6#↓ | 1.3#↓ | np | 2.6# | np | 4.7# | np | 5.0# | np |

| Other not employed-not looking for work | 9.9 | 7.6↓ | 9.4 | 7.5↓ | 4.5↓ | 3.5#↓ | 6.2↓ | np | 17.8↑ | np | np |

| Relationship status | |||||||||||

| Married/in a de facto relationship | 54.6 | 64.4↑ | 56.7 | 50.1↓ | 54.0 | 44.5↓ | 51.9 | 39.9↓ | 52.3 | 53.4 | 44.1 |

| Single | 45.4 | 35.6↓ | 43.3 | 49.9↑ | 46.0 | 55.5↑ | 48.1 | 60.1↑ | 47.7 | 46.6 | 55.9 |

| Household composition | |||||||||||

| Single adult household | 12.3 | 13.4↑ | 14.5↑ | 14.9↑ | 15.0↑ | 13.4 | 15.3↑ | 7.6↓ | 23.0↑ | 13.0 | 14.5 |

| Couple-only household | 24.4 | 29.9↑ | 28.4↑ | 30.5↑ | 29.5↑ | 24.0 | 27.0 | 10.9#↓ | 29.4 | 16.8 | 12.3↓ |

| Household with children | 30.3 | 26.3↓ | 22.4↓ | 16.4↓ | 25.1↓ | 24.4 | 20.7↓ | 22.3 | 20.2 | 31.3 | 25.4 |

| Multiple adult household | 33.0 | 30.5↓ | 34.7 | 38.3 | 30.4 | 38.3 | 37.0 | 59.2↑ | 27.4 | 38.8 | 47.9↑ |

| Housing tenure | |||||||||||

| Own outright | 17.3 | 19.0↑ | 18.5 | 19.5 | 19.0 | 15.4 | 16.4 | 14.2# | 12.2 | 10.7# | 9.9# |

| Own with mortgage | 52.7 | 55.1↑ | 50.6 | 49.6 | 53.5 | 54.9 | 52.2 | 61.7 | 50.4 | 68.3↑ | 57.0 |

| Rent | 27.7 | 23.5↓ | 28.4 | 28.4 | 25.6 | 28.7 | 27.7 | 23.8 | 32.1 | 19.7 | 31.1 |

| Remoteness | |||||||||||

| Major city | 72.5 | 69.7↓ | 65↓ | 64.8↓ | 66.8↓ | 77.1 | 53.5↓ | 86.0↑ | 66.2 | 75.9 | 79.7 |

| Inner regional | 18.2 | 19.2 | 21.8↑ | 24.3↑ | 19.8 | 16.8 | 28.4↑ | 7.5↓ | 23.6 | np | 14.8 |

| Outer regional/remote | 9.3 | 11.0↑ | 13.2↑ | 10.9 | 13.4↑ | 6.1↓ | 18.1↑ | 6.6# | 10.2 | 13.5 | 5.5# |

| SEIFA quintileb | |||||||||||

| Lowest | 19.6 | 19.0 | 21.8 | 27.6↑ | 22.2 | 19.6 | 32.3↑ | 10.3↓ | 41.2↑ | 18.0 | 14.6 |

| 2 | 18.2 | 19.8↑ | 18.3 | 20.3 | 19.6 | 14.8 | 23.8#↑ | 24.4 | 19.9 | 18.3 | 19.9 |

| Middle | 19.3 | 20.0 | 18.5 | 19.8 | 14.8↓ | 14.7↓ | 19.8# | 7.6↓ | 17.8 | 14.8 | 20.4# |

| 4 | 20.6 | 19.8 | 20.2 | 17.1↓ | 23.2 | 24.8 | 13.0↓ | 25.0 | 10.2↓ | 21.4 | 22.6 |

| Highest | 22.4 | 21.5 | 21.2 | 15.2↓ | 20.3 | 26.2 | 11.0↓ | 32.7 | np | 27.6 | 22.6# |

| Equivalised disposable household incomec | |||||||||||

| <$29,500 | 19.8 | 18.4↓ | 20.0 | 25.2↑ | 17.5 | 10.1↓ | 21.7 | 10.3 | 42.4↑ | 17.3 | 12.8 |

| $29,500-$41,499 | 20.4 | 19.4 | 18.9 | 19.6 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 14.2 | 16.0 | 18.1 | 21.1 |

| $41,500-$53,999 | 19.4 | 20.2 | 22.4 | 21.8 | 20.8 | 17.6 | 22.5 | 16.1 | 15.3 | 12.4 | 24.9 |

| $54,000-$73,499 | 20.2 | 21.0 | 20.2 | 19.4 | 19.2 | 23.4 | 21.7 | 33.8 | 17.4 | 25.0 | 23.5 |

| $73,500+ | 20.2 | 20.1 | 18.6 | 14.0↓ | 25.0↑ | 31.4↑ | 15.5 | 25.6 | 9.0 | 27.3 | 17.7 |

| Main source of household income | |||||||||||

| Wages/salary/business | 73.5 | 71.3↓ | 70.7 | 61.3↓ | 75.6 | 89.1↑ | 70.1 | 93.6↑ | 43.8↓ | 83.3↑ | 88.3↑ |

| Govt. pension/ allowance/ benefit | 18.2 | 19.6↑ | 20.7↑ | 29.3↑ | 17.2 | 7.2↓ | 22.4↑ | np | 50.6↑ | 13.8 | 11.7 |

| Superannuation/annuity/ investment | 8.1 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 3.5↓ | 7.3 | np | 5.6# | np | np |

Notes: Percentages based on weighted data. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding or non-response. a Only region of births representing >10% of the population are presented. b Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas 2011. c Household income after tax, weighted for size and composition of household. # RSE between 30% and 50%. np - data not presented due to insufficient responses or RSE >50% ↑ and ↓ are used to indicate values significantly above or below the general Australian population at p<.05.

5 Differences of around twenty percent or greater between the proportion of Australians and proportion of gambling participants represented by a sociodemographic characteristic were considered substantial.

3. Gambling expenditure

Introduction

This chapter presents HILDA survey-based estimates of typical past-year expenditure by regular gamblers in 2015, derived from self-reported, typical monthly spends. This information is presented in two ways. First, estimates of national expenditure by all regular gamblers in Australia are presented, which takes into account the estimated number of people participating in each gambling activity, and their spending on those activities. The national estimates are presented for overall spending on gambling as well as for each activity. These estimates are also presented in terms of what proportion of spending is accounted for by each sociodemographic group. The other perspective shown here is the average expenditure among those who report spending on gambling overall, and on particular activities. This analysis also compares average spending across sociodemographic groups.

Mean expenditure estimates for the five most common activities (lotteries, instant scratch tickets, EGMs, race betting, sports betting) are further provided for each sociodemographic group (e.g. average expenditure on sports betting by male participants). Due to sample size limitations, this level of detail could not be accurately estimated for the remaining five activities (keno, casino table games, bingo, private betting, poker).

All estimates of past-year expenditure were calculated by multiplying regular gamblers' self-reported typical monthly spend by 12. The estimates therefore do not represent total gambling expenditure for the year, which would include amounts from high and low spend months, and expenditure on activities where participation was less than monthly.6

See Appendix A for a comparison between the HILDA survey-based estimates of regular gamblers' typical expenditure presented in this chapter, and total gambling expenditure reported by the Australian gambling industry.

Key findings

- Typical monthly expenditure by the 6.8 million regular gamblers amounted to an estimated $8.6 billion dollars nationally for 2015. Lotteries (42%), EGMs (21%) and race betting (15%) accounted for most of this.

- The majority of national gambling expenditure by regular gamblers was accounted for by participants who were male, aged 30-64, born in Australia, spoke English as a first language, had completed no more than 10 years of schooling, were employed full-time, married/in a de facto relationship, lived in a major city, had a high income, and drew their main source of income from employment.

- Typical past-year expenditure on gambling was an estimated average of $1,272 per regular participant. In terms of particular activities, poker recorded the highest average spend per participant ($1,785) and instant scratch tickets the lowest ($248).

- Gamblers generally spent around half of their overall gambling outlay on a single product. Lotteries (79%) and keno (32%) were exceptions, accounting for substantially more and less of their respective participants' overall outlays.

- Mean expenditure was significantly higher than average among gamblers who were male, had completed schooling no further than year 10, were employed full-time, single, and lived with multiple adults. It was lower among gamblers who had a university degree, and lived in a house with children.

- Mean expenditure was otherwise similar between gamblers with different sociodemographic characteristics, including those with low and high incomes and those whose main source of income was either a wage or welfare payment.

National gambling expenditure

Table 3.1 shows HILDA survey-based estimates of national past-year gambling expenditure by regular participants on each activity.

Typical monthly gambling expenditure by the 6.8 million regular gamblers amounted to approximately $8.6 billion dollars over 2015. Lotteries (42%), EGMs (21%) and race betting (15%) together accounted for around three quarters of this amount. Seven activities accounted for the remaining quarter.

| National expenditure | Proportion of national expenditure | |

|---|---|---|

| Activity | $M | % |

| Lottery | 3,577 | 41.6 |

| Instant scratch tickets | 368 | 4.3 |

| EGMs | 1,820 | 21.1 |

| Race betting | 1,265 | 14.7 |

| Sports betting | 579 | 6.7 |

| Keno | 226 | 2.6 |

| Casino table games | 256 | 3.0 |

| Bingo | 156 | 1.8 |

| Private betting | 134 | 1.6 |

| Poker | 228 | 2.7 |

| 8,609 | 100.0 |

Notes: Values are based on weighted data and capped expenditure. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. Expenditure calculations exclude those who reported they had participated in an activity in a typical month, but who did not report a dollar amount when prompted for the expenditure. See Appendix A for a comparison between these survey-based estimates and actual 'known' expenditure reported by industry

National gambling expenditure by sociodemographic characteristics

Table 3.2 shows HILDA survey-based estimates of national gambling expenditure, by regular gamblers, for each sociodemographic group.

The sociodemographic groups responsible for the highest proportion of gambling expenditure were males, those aged 50-64, those born in Australia, those who spoke English as a first language, who had a certificate or diploma, were employed full-time, were married/in a de facto relationship, lived in a multiple adult household with no children, owned their home with a mortgage, lived in a major city, those who had higher incomes, and drew their main source of income from employment.

| Total spend | Proportion of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Subpopulation categories | $M | % |

| Overall | ||

| All gamblers | 8,609 | 100.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5,509 | 64.0 |

| Female | 3,100 | 36.0 |

| Age group | ||

| 18-29 | 1,079 | 12.5 |

| 30-49 | 2,648 | 30.8 |

| 50-64 | 2,837 | 33.0 |

| 65+ | 2,046 | 23.8 |

| Indigenous status | ||

| Non-Indigenous | 8,366 | 97.2 |

| Indigenous | 243 | 2.8 |

| Region of birth a | ||

| Australia | 6,145 | 71.4 |

| Europe | 1,000 | 11.6 |

| Asia | 605 | 7.0 |

| First language spoken | ||

| English | 7,467 | 86.7 |

| Other | 923 | 10.7 |

| Highest education Level | ||

| Below year 10 | 769 | 8.9 |

| Completed year 10 | 1,813 | 21.1 |

| Completed year 12 | 1,172 | 13.6 |

| Certificate or diploma | 3,512 | 40.9 |

| Bachelors or higher | 1,328 | 15.5 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed full-time | 4,351 | 50.5 |

| Employed part-time | 1,226 | 14.2 |

| Unemployed-looking for work | 243 | 2.8 |

| Retired | 2,060 | 23.9 |

| Full-time student | np | - |

| Not employed-not looking for work | 629 | 7.3 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married/in a de facto relationship | 4,818 | 56.0 |

| Single | 3,791 | 44.0 |

| Household composition | ||

| Single adult household | 1,311 | 15.2 |

| Couple only household | 2,471 | 28.7 |

| Household with children | 1,741 | 20.2 |

| Multiple adult household | 3,087 | 35.9 |

| Housing tenure | ||

| Own outright | 1,610 | 18.7 |

| Own with mortgage | 4,613 | 53.6 |

| Rent | 2,172 | 25.2 |

| Remoteness | ||

| Major city | 6,054 | 70.3 |

| Inner regional | 1,618 | 18.8 |

| Outer regional/remote | 937 | 10.9 |

| SEIFA quintile b | ||

| Lowest | 1,863 | 21.6 |

| 2 | 1,759 | 20.4 |

| Middle | 1,573 | 18.3 |

| 4 | 1,655 | 19.2 |

| Highest | 1,761 | 20.5 |

| Equivalised disposable household income c | ||

| <$29,500 | 1,579 | 18.3 |

| $29,500-$41,499 | 1,500 | 17.4 |

| $41,500-$53,999 | 1,770 | 20.6 |

| $54,000-$73,499 | 1,881 | 21.8 |

| $73,500+ | 1,879 | 21.8 |

| Main source of household income | ||

| Wages/salary/business | 6,103 | 70.9 |

| Govt. pension/allowance/benefit | 1,782 | 20.7 |

| Superannuation/annuity/investment | 708 | 8.2 |

Notes: Values are based on weighted data and capped expenditure. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding or non-response. Expenditure calculations exclude those who reported they had participated in an activity in a typical month, but who did not report a dollar amount when prompted for the expenditure. a Only regions of birth representing >10% of the population are presented. b Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas 2011. c Household income after tax, weighted for size and composition of household.

National gambling expenditure on each activity by sociodemographic characteristics

Table 3.3 shows past-year expenditure on the five most common activities by regular gamblers in each sociodemographic group.

The sociodemographic groups that spent the most on each of the five activities were the same as those for overall expenditure, with a few exceptions:

- Females spent more than males on instant scratch tickets.

- People in lower income groups spent more on instant scratch tickets and EGMs than those with higher incomes.

- Those aged 18-29 spent more on sports betting compared to other age groups.

- Single people spent more on EGMs and sports betting than those who were married/in a de facto relationship.

The table can also be viewed on pages 23–24 of the PDF.

| Lottery | Instant scratch tickets | EGMs | Race betting | Sports betting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subpopulation categories | $M | % | $M | % | $M | % | $M | % | $M | % |

| Overall | ||||||||||

| All activity participants | 3,577 | 100.0 | 368 | 100.0 | 1,820 | 100.0 | 1,265 | 100.0 | 579 | 100.0 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 2,132 | 59.6 | 176 | 47.8 | 1,009 | 55.4 | 1,129 | 89.2 | 512 | 88.4 |

| Female | 1,445 | 40.4 | 192 | 52.2 | 812 | 44.6 | 137 | 10.8 | 67# | 11.6 |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 18-29 | 125 | 3.5 | 37 | 10.1 | 216 | 11.9 | 191 | 15.1 | 229 | 39.6 |

| 30-49 | 1,138 | 31.8 | 107 | 29.1 | 467 | 25.7 | 393 | 31.1 | 223 | 38.5 |

| 50-64 | 1,322 | 37.0 | 131 | 35.6 | 606 | 33.3 | 457 | 36.1 | 82 | 14.2 |

| 65+ | 992 | 27.7 | 92 | 25.0 | 531 | 29.2 | 225 | 17.8 | np | - |

| Indigenous status | ||||||||||

| Non-Indigenous | 3,515 | 98.3 | 354 | 96.2 | 1,756 | 96.5 | 1,232 | 97.4 | 556 | 96.0 |

| Indigenous | 62 | 1.7 | 13# | 3.5 | 64 | 3.5 | 34# | 2.7 | 23# | 4.0 |

| Region of birtha | ||||||||||

| Australia | 2,491 | 69.6 | 267 | 72.6 | 1,299 | 71.4 | 1,025 | 81.0 | 432 | 74.6 |

| Europe | 483 | 13.5 | 31 | 8.4 | 253 | 13.9 | 128# | 10.1 | 30# | 5.2 |

| Asia | 248 | 6.9 | 29# | 7.9 | 133 | 7.3 | 23# | 1.8 | np | - |

| First language spoken | ||||||||||

| English | 3,125 | 87.4 | 317 | 86.1 | 1,609 | 88.4 | 1,199 | 94.8 | 520 | 89.8 |

| Other | 356 | 10.0 | 40# | 10.9 | 175# | 9.6 | 58# | 4.6 | np | - |

| Highest education level | ||||||||||

| Below year 10 | 315 | 8.8 | 42 | 11.6 | 234 | 12.9 | 52 | 4.2 | np | - |

| Completed year 10 | 737 | 20.6 | 77 | 21.0 | 441 | 24.2 | 247 | 19.6 | 99 | 17.2 |

| Completed year 12 | 406 | 11.4 | 31 | 8.6 | 260 | 14.3 | 201 | 16.0 | 107 | 18.5 |

| Certificate or Diploma | 1,498 | 42.0 | 152 | 41.5 | 685 | 37.6 | 544 | 43.1 | 214 | 36.9 |

| Bachelors or higher | 614 | 17.2 | 63 | 17.3 | 200 | 11.0 | 216 | 17.1 | 120 | 20.8 |

| Employment | ||||||||||

| Employed full-time | 1,760 | 49.2 | 162 | 44.1 | 766 | 42.1 | 762 | 60.2 | 360 | 62.1 |

| Employed part-time | 533 | 14.9 | 49 | 13.4 | 252 | 13.8 | 145 | 11.5 | 91# | 15.8 |

| Unemployed- looking for work | 53 | 1.5 | 7 | 2.0 | 79# | 4.3 | np | - | np | - |

| Retired | 975 | 27.3 | 100 | 27.2 | 537 | 29.5 | 229 | 18.1 | np | - |

| Full-time student | np | - | np | - | 8# | 0.4 | np | - | np | - |

| Not employed-not looking for work | 245 | 6.9 | 39 | 10.6 | 177 | 9.7 | np | - | 10# | 1.7 |

| Relationship status | ||||||||||

| Married/in a de facto relationship | 2,300 | 64.3 | 217 | 59.0 | 871 | 47.9 | 655 | 51.8 | 236 | 40.8 |

| Single | 1,278 | 35.7 | 151 | 41.0 | 950 | 52.2 | 610 | 48.2 | 343 | 59.2 |

| Household composition | ||||||||||

| Single adult household | 513 | 14.3 | 46 | 12.5 | 342 | 18.8 | 219 | 17.3 | 60 | 10.4 |

| Couple only household | 1,149 | 32.1 | 110 | 29.9 | 525 | 28.8 | 381 | 30.1 | 147 | 25.4 |

| Household with children | 776 | 21.7 | 81 | 22.0 | 290 | 15.9 | 240 | 19.0 | 104 | 18.0 |

| Multiple adult household | 1,139 | 31.8 | 130 | 35.4 | 664 | 36.5 | 426 | 33.6 | 268 | 46.3 |

| Housing tenure | ||||||||||

| Own outright | 732 | 20.5 | 61 | 16.6 | 333 | 18.3 | 263 | 20.8 | 136 | 23.5 |

| Own with mortgage | 1,973 | 55.2 | 188 | 51.1 | 934 | 51.3 | 645 | 51.0 | 274 | 47.3 |

| Rent | 765 | 21.4 | 112 | 30.4 | 525 | 28.8 | 308 | 24.3 | 160# | 27.6 |

| Remoteness | ||||||||||

| Major city | 2,445 | 68.4 | 236 | 64.1 | 1,286 | 70.7 | 867 | 68.5 | 480 | 82.9 |

| Inner regional | 726 | 20.3 | 78 | 21.2 | 364 | 20.0 | 230 | 18.2 | 62 | 10.7 |

| Outer regional/remote | 406 | 11.4 | 53 | 14.4 | 170 | 9.3 | 169 | 13.4 | 37# | 6.4 |

| SEIFA quintile b | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 712 | 19.9 | 92 | 25.0 | 482 | 26.5 | 265 | 20.9 | 67 | 11.6 |

| 2 | 775 | 21.7 | 71 | 19.3 | 359 | 19.7 | 276 | 21.8 | 73# | 12.6 |

| Middle | 677 | 18.9 | 66 | 17.9 | 360 | 19.8 | 161 | 12.7 | 84# | 14.5 |

| 4 | 731 | 20.4 | 75 | 20.4 | 294 | 16.2 | 260 | 20.6 | 156 | 26.9 |

| Highest | 682 | 19.1 | 64 | 17.4 | 326 | 17.9 | 304 | 24.0 | 199 | 34.4 |

| Equivalised disposable household income c | ||||||||||

| <$29,500 | 674 | 18.8 | 70 | 19.0 | 424 | 23.3 | 181 | 14.3 | 57# | 9.8 |

| $29,500-$41,499 | 644 | 18.0 | 76 | 20.7 | 296 | 16.3 | 239 | 18.9 | 109# | 18.8 |

| $41,500-$53,999 | 679 | 19.0 | 101 | 27.4 | 440 | 24.2 | 205 | 16.2 | 85# | 14.7 |

| $54,000-$73,499 | 758 | 21.2 | 63 | 17.1 | 403 | 22.1 | 268 | 21.2 | 152 | 26.3 |

| $73,500+ | 823 | 23.0 | 57 | 15.5 | 257 | 14.1 | 373 | 29.5 | 176 | 30.4 |

| Main source of household income | ||||||||||

| Wages/salary/business | 2,527 | 70.6 | 253 | 68.8 | 1,115 | 61.3 | 914 | 72.3 | 488 | 84.3 |

| Govt. pension/allowance/benefit | 744 | 20.8 | 89 | 24.2 | 539 | 29.6 | 212 | 16.8 | np | - |

| Superannuation/annuity/investment | 297 | 8.3 | 24 | 6.5 | 160 | 8.8 | 139 | 11.0 | np | - |

Notes: Values are based on weighted data and capped expenditure. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding or non-response. a Only regions of birth representing >10% of the population are presented.

b Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas 2011. c Household income after tax, weighted for size and composition of household. # RSE between 30% and 50%. np - data not presented due to insufficient responses or RSE >50%. Expenditure calculations exclude those who reported they had participated in an activity in a typical month, but who did not report a dollar amount when prompted for the expenditure.

Mean gambling expenditure

Table 3.4 presents mean expenditure on each activity by regular gamblers in 2015. The estimated amount activity participants spent across all regular gambling activities is included in the second column. The third column shows the mean proportion of their total typical gambling expenditure that the activity in question constituted. The annual dollar values reflect mean typical monthly expenditure multiplied by twelve.

The mean typical expenditure per gambler was $1,272 for 2015. Poker saw the highest mean spend per participant, followed by casino table games, race betting, EGMs and sports betting, all of which exceeded $1000.

Lottery participants spent most of their average gambling outlay for the year on this single activity (79%; a mean lottery spend of $695 would equate to a total gambling outlay of $878), whereas keno participants spent only one third of their gambling money on this activity. All other activities attracted somewhere around half of respective participants' average gambling outlay for the year, with private betting being the lowest of these (43%) and EGMs the highest (60%).

| Mean spend on activity | 95% CI | Estimated average total gambling expenditure | Proportion of total gambling spend accounted for by activity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | $ | $ | $ | % |

| Lottery | 695 | 658-733 | 878 | 79.2 |

| Instant scratch tickets | 248 | 215-281 | 622 | 39.9 |

| EGMs | 1,292 | 1,150-1,433 | 2,146 | 60.2 |

| Race betting | 1,308 | 1,140-1,477 | 2,502 | 52.3 |

| Sports betting | 1,032 | 767-1,296 | 2,305 | 44.8 |

| Keno | 425 | 354-497 | 1,310 | 32.4 |

| Casino table games | 1,369 | 962-1,776 | 2,566 | 53.4 |

| Bingo | 863 | 676-1,050 | 1,568 | 55.1 |

| Private betting | 898 | 633-1,163 | 2,080 | 43.2 |

| Poker # | 1,758 | 505-3,065 | 3,674 | 47.9 |

| All gamblers | 1,272 | 1,183-1,361 | - | 100.0 |

Notes: Values are based on weighted data and capped expenditure. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. Expenditure calculations exclude those who reported they had participated in an activity in a typical month, but who did not report a dollar amount when prompted for the expenditure. # RSE between 30% and 50%

Mean gambling expenditure by sociodemographic characteristics

Table 3.5 shows mean past-year gambling expenditure by participants in each sociodemographic group.

For the most part, mean gambling expenditure did not differ significantly across sociodemographic groups. Similar amounts were spent by people of different age, Indigenous status, country of birth, language spoken at home, housing tenure, remoteness, area economic advantage, income and source of income.

Gambling expenditure was significantly higher than average among male gamblers, those who had completed schooling no further than year 10, were employed full-time, single and lived with multiple adults.

Expenditure was lower than average among females, those aged 30-49, those who had a university degree, and lived in a household with children.

| Mean spend | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Subpopulation categories | $ | $ |

| Overall | ||

| All gamblers | 1,272 | 1,183-1,361 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1,499↑ | 1,374-1,625 |

| Female | 1003↓ | 922-1,083 |

| Age group | ||

| 18-29 | 1,341 | 963-1,720 |

| 30-49 | 1,148↓ | 1,009-1,286 |

| 50-64 | 1,381 | 1,204-1,557 |

| 65+ | 1,278 | 1,144-1,412 |

| Indigenous status | ||

| Non-Indigenous | 1,267 | 1,178-1,355 |

| Indigenous | 1,496 | 934-2,057 |

| Region of birth a | ||

| Australia | 1,262 | 1,182-1,342 |

| Europe | 1,242 | 982-1,503 |

| Asia | 1,218 | 765-1,671 |

| First language spoken | ||

| English | 1,245 | 1,176-1,314 |

| Other | 1,440 | 845-2,035 |

| Highest education Level | ||

| Below year 10 | 1,250 | 1,030-1,469 |

| Completed year 10 | 1,417↑ | 1,257-1,577 |

| Completed ear 12 | 1,336 | 988-1,685 |

| Certificate or diploma | 1,367 | 1,205-1,529 |

| Bachelor or higher | 942↓ | 791-1,093 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed full-time | 1,353↑ | 1,221-1,486 |

| Employed part-time | 1,117 | 966-1,268 |

| Unemployed-looking for work | 1,588 | 883-2,292 |

| Retired | 1,222 | 1,099-1,345 |

| Full-time student | 1,207 | 30-2,385 |

| Not employed-not looking for work | 1,190 | 824-1,556 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married/in a de facto relationship | 1,195↓ | 1,087-1,302 |

| Single | 1,387↑ | 1,248-1,525 |

| Household composition | ||

| Single adult household | 1,372 | 1,199-1,545 |

| Couple only household | 1,278 | 1,140-1,417 |

| Household with children | 1,002↓ | 860-1,143 |

| Multiple adult household | 1,442↑ | 1,239-1,645 |

| Housing Tenure | ||

| Own outright | 1,298 | 1,116-1,480 |

| Own with mortgage | 1,282 | 1,181-1,382 |

| Rent | 1,237 | 1,079-1,394 |

| Remoteness | ||

| Major city | 1,294 | 1,167-1,421 |

| Inner regional | 1,202 | 1,094-1,311 |

| Outer regional/remote | 1,262 | 1,067-1,457 |

| SEIFA quintile b | ||

| Lowest | 1,400 | 1,221-1,580 |

| 2 | 1,327 | 1,163-1,491 |

| Middle | 1,178 | 989-1,366 |

| 4 | 1,224 | 1,087-1,361 |

| Highest | 1,236 | 1,029-1,443 |

| Equivalised disposable household income c | ||

| <$29,500 | 1,218 | 1,073-1,363 |

| $29,500-$41,499 | 1,142 | 998-1,287 |

| $41,500-$53,999 | 1,293 | 1,107-1,480 |

| $54,000-$73,499 | 1,331 | 1,150-1,512 |

| $73,500+ | 1,366 | 1,179-1,553 |

| Main source of household income | ||

| Wages/salary/business | 1,280 | 1,176-1,385 |

| Govt. pension/allowance/benefit | 1,280 | 1,124-1,437 |

| Superannuation/annuity/investment | 1,203 | 936-1,471 |

Notes: Values based on weighted data and capped expenditure. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding or non-response. a Only regions of birth representing >10% of the population are presented. b Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas 2011. c Household income after tax, weighted for size and composition of household. ↑ and ↓ are used to indicate values significantly above or below overall mean spend at p<.05. Expenditure calculations exclude those who reported they had participated in an activity in a typical month, but who did not report a dollar amount when prompted for the expenditure.

Mean activity-level gambling expenditure by sociodemographic characteristics

Table 3.6 shows mean expenditure on the five most common activities by participant sociodemographic characteristics for 2015. Within each activity, mean expenditure by sociodemographic characteristic was compared to the overall activity mean expenditure. Participant sample sizes were too small to provide this level of detail reliably for the five remaining activities (keno, casino table games, bingo, private betting, poker).

Lottery expenditure was significantly higher than the mean spend of $695 among people who were male, aged 50 and over, and lived with their partner.

The mean spending on instant scratch ticket expenditure varied little across sociodemographic groups, with a yearly mean spend of $248overall.

Electronic gaming machine expenditure was significantly higher than the mean spend of $1,292 among people who lived alone, and lived in a major city.

Race betting expenditure was significantly higher than the mean spend of $1,308among people who were male. The yearly average for males on this activity ($1,442) was around double that for females ($741).

Among sports betting participants (with a mean spend of $1,032), differences by sociodemographic characteristics were largely not statistically significant, although there was some variation apparent for the socio-economic status of the region, and household income.

Overall, variation in spending was much greater across activities than across sociodemographic characteristics.

| Lottery | Instant scratch tickets | EGMs | Race betting | Sports betting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subpopulation categories | $ | $ | $ | $ | $ |

| Overall | |||||

| All activity participants | 695 | 248 | 1,292 | 1,308 | 1,032 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 782↑ | 261 | 1,311 | 1,442↑ | 1,034 |

| Female | 598↓ | 237 | 1,268 | 741↓ | 1,017# |

| Age group | |||||

| 18-29 | 395↓ | 199 | 951↓ | 1,263 | 1,238 |

| 30-49 | 615↓ | 235 | 1,306 | 1,159 | 932 |

| 50-64 | 767↑ | 267 | 1,452 | 1,505 | 804 |

| 65+ | 790↑ | 263 | 1,305 | 1,293 | np |

| Indigenous status | |||||

| Non-Indigenous | 696 | 247 | 1,311 | 1,321 | 1,041 |

| Indigenous | 634 | 286 | 926 | 969 | 850 |

| Region of birth a | |||||

| Australia | 695 | 246 | 1,179↓ | 1,310 | 940 |

| Europe | 709 | 209 | 1,459 | 1,553 | 859 |

| Asia | 599 | 318 | 2,577 | 662#↓ | np |