Parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2004

Diana Smart

Download Research report

Overview

Alcohol use is widespread among Australian adolescents, and high risk use is a serious and growing problem.

A range of individual, family, peer, school and community characteristics have been shown to be risk factors for the development of adolescent alcohol use and misuse.

This report reviews and synthesises the research and interventions concerning the impact of parenting factors on adolescent alcohol use. It focuses particularly on recent Australian research and research with Indigenous and other cultural sub-groups, but also includes influential research conducted in other countries. It concludes with discussion of implications for research and policy, highlighting key conclusions that may be drawn from the findings reviewed.

Foreward

While there is widespread acknowledgement of the problem of adolescent abuse of alcohol, the pathways to it remain contentious. The influence of parents on these pathways has been unclear. This report, Parenting Influences on Adolescent Alcohol Use, provides invaluable new insights into the influences that parents exert on adolescent alcohol use.

The report's messages have an elegant clarity and answer a number of key questions. Among these are: Should parents delay adolescents' introduction to alcohol? What role do parents play in guiding responsible alcohol use? How do parents exert an influence? What other sources of influence are there - for example, from peers, the wider culture and the media? Which interventions have been demonstrated to work, and how widely available are these in Australia?

This report provides answers to these questions. For example, it demonstrates the long-term benefits of delaying adolescents' uptake of alcohol. It also shows the ways in which parents can guide patterns of use once adolescents have started consuming alcohol. It explodes a popular myth that parents have little impact in this area by showing that they can and do influence their offspring's alcohol use, especially through their supervision and monitoring behaviours, the closeness of their relationships with their children, and through positive behaviour management practices. While parents have a greater influence than many would admit, the peer group, cultural norms, and the law also play substantial roles. Successful modification of the patterns of teenage drinking will need to target all these spheres of influence.

While there is very little Australian research and very few intervention programs with proven success, this report shows some productive ways forward, both through investment in research and evaluation, and the implementation of evidence-based interventions.

The Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing is to be congratulated for this most valuable investment in addressing an issue of such widespread community concern. The authors of the report, Louise Hayes, Diana Smart, John Toumbourou and Ann Sanson, are to be especially commended on completing a significant and groundbreaking report.

This volume should provide an excellent resource for policy makers, practitioners, and researchers, to work together to address a social issue of urgent priority. I am delighted that the Australian Institute of Family Studies could contribute to such a productive collaboration and look forward to its impacts on policy and practice.

Professor Alan Hayes

Director

Australian Institute of Family Studies

Executive summary

This report is the fulfilment of a contract between the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and the Australian Institute of Family Studies. Alcohol use is widespread among Australian adolescents, and high risk use is a serious and growing problem. A range of individual, family, peer, school and community characteristics have been shown to be risk factors for the development of adolescent alcohol use and misuse. This report aims to review and synthesise the research and interventions concerning the impact of parenting factors on adolescent alcohol use.

To set the scene for the review, the patterns of alcohol use among Australian adolescents are described. Alcohol use is shown to be common among young Australians, with many experimenting with alcohol by the age of 14-15 years. Once adolescents begin drinking, most become regular consumers of alcohol. The evidence suggests that delaying the onset of drinking reduces long-term consumption levels into adulthood. A large proportion of Australian adolescents obtain alcohol from their parents.

Two theoretical models are used to provide a framework in which to understand the research on parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use. First, the Social Interactional model is used to describe the impact of parenting behaviours and skills such as monitoring, parental behaviour management, parent-adolescent relationship quality, and parenting norms, goals and values. Second, the Social Development model is used to understand the importance of broader environmental influences on adolescents and parents. Thus, parental consumption of alcohol, parental alcohol abuse and dependence, family structure, and family socio-economic background, the role of differing cultural norms and legal systems, and findings regarding Indigenous adolescents are examined.

Parental monitoring

Parental monitoring has been defined as parental awareness of the child's activities, and communication to the child that the parent is concerned about, and aware of, the child's activities (Dishion and McMahon 1998). The review demonstrates that adolescents who are poorly monitored begin alcohol consumption at an earlier age, tend to drink more, and are more likely to develop problematic drinking patterns. Australian parents are likely to be unaware of, or to underestimate, their adolescent's alcohol consumption and are more concerned about illicit drug use than alcohol use. Australian parents may feel pressured to accept alcohol use by adolescents as "normal". It appears that for many parents, knowing the "right age" to permit their adolescents to consume alcohol, or indeed if they should permit alcohol consumption at all, is a critical question that they feel ill equipped to answer.

Parental behaviour management

Parental behaviour management encompasses positive practices such as the use of incentives, positive reinforcement, setting limits for appropriate behaviour, providing consequences for misbehaviour, and negotiating boundaries and rules for appropriate behaviour, as well as less effective strategies such harsh and punitive discipline, high conflict, and lax, inconsistent or over-permissive approaches. Family standards and rules, rewards for good behaviour, and well developed negotiation skills were associated with lower initiation of alcohol use in early adolescence, and lower rates of alcohol abuse and dependence in early adulthood. Harsh discipline and high conflict were associated with higher rates of alcohol use. When parents were openly permissive toward adolescent alcohol use, adolescents tended to drink more.

Relationship quality

Parent-adolescent relationship quality underpins all aspects of parenting, and is the product of an ongoing interplay between parents and adolescents. For example, without a warm relationship, adolescents are more likely to resist monitoring, while authoritative parenting may contribute to and enhance strong parent-adolescent relationships. Warm and supportive parent-adolescent relationships were associated with lower levels of adolescent alcohol use, as well as lower rates of problematic use and misuse.

Parental norms

Parenting norms, values and goals reflect parents' belief systems, attitudes and conceptions concerning adolescent behaviour. Parental norms, attitudes, and beliefs with regard to adolescent alcohol use have an important influence on adolescent alcohol consumption. When parents show disapproval, their adolescents are less likely to drink, and conversely, when parents are tolerant or permissive, their adolescents are likely to drink more. Australian parents and adolescents differ in their perceptions of the appropriate age that adolescents should be permitted to consume alcohol, with studies showing that many parents believe 17 years is the appropriate age for adolescents to begin consuming alcohol at home, and many adolescents tending to believe this should occur earlier, at approximately 16 years.

Parental, family and broader environmental influences

Parents' own use of alcohol was found to increase the likelihood that adolescents would also consume alcohol. Biological links between parental alcohol dependence and adolescent alcohol use were evident. Adolescents from intact families were found to less often engage in heavy alcohol use, while adolescents from sole parent families were more often involved in heavy drinking.

In addition, social laws and norms were shown to exert a considerable influence on adolescent alcohol consumption, and parental attitudes toward adolescent alcohol use. International research has found that changes to policy or laws can influence adolescent consumption patterns.

Parenting and peer influences compared

The effect of peers was shown to mediate the influence of parenting on adolescents' alcohol use. Peer effects become particularly powerful when parent-adolescent relationships are of poorer quality. The influence of peers is thought to occur through peer modelling, peer pressure, or association with alcohol using peers. However, direct connections between parental monitoring and adolescent alcohol use remained after peer influences were taken into account.

Gaps and deficiencies in the research

There are a number of gaps and deficiencies in the literature. First, the research coverage is incomplete, Second, there is very little Australian data on this issue, and international research was relied upon to a large extent. When considering parent-adolescent relationships and parenting behaviours in general, international research reveals similar findings to Australian research. However, there are important social and cultural differences which may influence parenting behaviours and attitudes concerning adolescent alcohol use in differing countries. Third, much of the research has sought the views of adolescents only, and the findings need to be confirmed by parents and/or other informants. Fourth, while there was considerable consistency in the findings, on one important area - parental supply of alcohol - inconsistent findings were found. Finally, the possibility of gender differences has often been overlooked.

Promising intervention programs

Using randomised controlled trials as the "gold standard" for intervention programs, a small number of interventions conducted in other countries, which targeted changing parenting behaviours and parental education, have shown long term reductions in adolescent alcohol use. Several promising Australian interventions are currently underway, including PACE, Teen Triple P, and ABCD. However, Australian research using rigorous methodology and thorough evaluations is needed.

Synthesis of findings

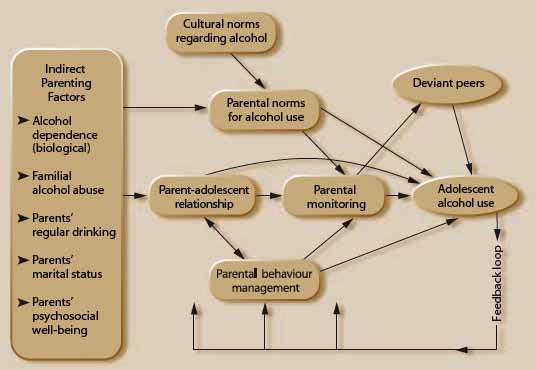

To summarise the research reviewed, a conceptual model of parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use was developed. This model suggested that parental monitoring, parental norms for adolescent use, and parental behaviour management skills all have direct links to adolescent alcohol use. Parent-adolescent relationship quality has an overall effect on these parenting behaviours, as well as direct connections to alcohol use. Parental characteristics have an indirect effect on alcohol use, by way of their influence on the parenting behaviours described above. The parental characteristics depicted as having an indirect effect include parental alcohol use or abuse, as well as family factors, and broader cultural norms regarding alcohol use.

Conclusions

The evidence demonstrates that there is now a reasonable understanding of the processes by which parents influence adolescent alcohol use. In addition, there is also intervention evidence suggesting these principles can be translated into effective programs. Several specific conclusions are presented which highlight strategies to assist parents to more effectively guide adolescents towards responsible alcohol use.

Conclusion 1

Parents should be provided with information concerning the advantages of delaying the age at which young people begin using alcohol.

Based on the available research, there appear to be clear advantages in delaying the age at which young people begin using alcohol. Among these are the reduced likelihood of risky alcohol use and abuse in adulthood, averting the adverse impacts of alcohol on the developing adolescent body and brain, and avoiding the immediate risks to health and wellbeing conveyed by "normal" patterns of adolescent alcohol use (which are often at risky or high risk levels). It is unclear that parents are aware of this evidence, and efforts to publicise this information would appear highly worthwhile.

Conclusion 2

Parents should be provided with educative guidelines on the influence of parental attitudes and norms on adolescent alcohol use, as well as guidance in managing the social pressure they feel to allow their adolescents to consume alcohol.

Parents report feeling adverse social pressure and not having the confidence to assist children and adolescents to delay the initiation of alcohol use. However, the research evidence suggests that parental attitudes and norms can play a considerable role. Parents should be made aware of this research, and may also benefit from more information about the extent of high risk alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents, and distinctions between safe and risky levels of alcohol use. Additionally, knowledge that many Australian parents believe late adolescence to be the appropriate age at which adolescents should be introduced to alcohol might assist parents to resist pressure to permit their adolescent to commence use at an earlier age.

Conclusion 3

Once adolescents have commenced alcohol use, parents should be provided with educative guidelines which enable them to guide their adolescents in responsible alcohol use.

Once adolescents have commenced drinking, enhanced monitoring appears to be a key component of efforts to minimise harmful alcohol use. However, this first requires attention to the parent-adolescent relationship, and simply advising parents to ask more questions may have a detrimental effect in some families. Once a high quality parent-child relationship is in place, parents can then be educated on the importance of clear and consistent rules regarding alcohol use, setting age appropriate limits, and maintaining open communication about adolescents' use of free time.

Conclusion 4

Parent education and family intervention programs should be supported in Australia to assist parents to gain skills for encouraging their adolescents to delay initiation to alcohol use and to adopt less harmful patterns of use. Intervention and prevention programs should receive best practice evaluations.

Interventions that have shown promise in the North American context should be adapted, implemented and evaluated in Australia. Existing Australian interventions should also be evaluated for their potential to encourage a delayed age of first alcohol use and more moderate patterns of use. Prior to encouraging wider dissemination, evaluation funding should be provided to enable gold standard evaluations including randomised control trial designs and long-term follow-up evaluations. These best practice programs should promote the parent-adolescent relationship as a key starting point. As was demonstrated by this review, this aspect of parenting underpins the other elements shown to be important, for example monitoring and positive behavioural management techniques.

Conclusion 5

Given that broader social norms exert a considerable influence on adolescent alcohol use, strategies to reduce favourable cultural attitudes towards under-age alcohol consumption will be needed to support parental efforts.

An extensive educative effort, aimed at changing favourable societal attitudes towards adolescent alcohol use, appears necessary to assist parental efforts to delay adolescents' initiation of alcohol use and to guide responsible subsequent use. It will also be necessary to target broader adolescent attitudes regarding alcohol.

Conclusion 6

More Australian research is needed to promote understanding of the developmental processes and pathways to adolescent alcohol use. In particular, research on the development of adolescent alcohol use in Indigenous communities is seriously lacking.

At present, there is a critical lack of Australian data on the pathways to differing patterns of alcohol use, and the role that parents play. There is also a lack of Australian research evaluating promising intervention initiatives. Thus, the international research, and particularly the U.S. research, is relied upon to a large extent. Yet there are important differences, particularly relating to cultural norms and attitudes, which may dilute the transferability of the international research to the Australian context. In particular, there is almost no research on Indigenous communities on this issue. A greater investment in research in this area would appear to be vital.

1. Introduction

Alcohol use is widespread among Australian adolescents. The 2001 National Drug Strategy Household Survey, for example, found that two-thirds of 14-17 year olds had recently consumed alcohol, with approximately one-fifth reporting regular alcohol use. Similarly, longitudinal data from the Australian Temperament Project showed that 25 per cent of 13-14 year old adolescents had consumed alcohol within the past month, and noted a sharp escalation in alcohol use across adolescence, with 60 per cent of these adolescents consuming alcohol in the past month at 15-16 years and 85 per cent at 17-18 years (Smart, Vassallo, Sanson, Richardson, Dussuyer et al. 2003).

Adolescent alcohol misuse is a serious and growing problem. Although many adolescents experience no alcohol-related problems (Bonomo, Coffey, Wolfe, Lynskey, Bowes and Patton 2001), a large sub-group engage in risky drinking. For example, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW 2003) found that 35 per cent of Australian adolescents aged 14-17 years and 64 per cent of those aged 18-24 years were reported to drink at risky or high-risk levels in the short term. The incidence of risky alcohol use is reported to be even higher among Indigenous youth (AIHW 2003).

Numerous individual, family, school and community characteristics have been identified as risk factors for the development of adolescent alcohol use and misuse1 (Hawkins, Catalano and Miller 1992). This report aims to review and synthesise the research concerning the impact of parenting factors on adolescent alcohol use. It is anticipated that a better understanding of parenting influences on adolescents' uptake of alcohol and risky alcohol use will provide valuable guidance for prevention and intervention initiatives, enabling the provision of more effective family support services.

This report is in fulfilment of a contract between the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and the Australian Institute of Family Studies. The report aims to:

- Review and summarise the literature concerning parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use, focusing particularly on recent Australian research and research with Indigenous and other cultural sub-groups; but also including influential research conducted in other countries.

- Analyse the current body of knowledge concerning parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use, identifying gaps and weaknesses and detailing how such deficiencies might weaken the strength of conclusions that may be drawn and that may impact upon intervention strategies.

- Elucidate the implications emerging from the research findings for the development of policies and prevention/intervention initiatives directed towards adolescent alcohol use and alcohol harm minimisation, highlighting the ways in which parents can be assisted to guide adolescents more effectively in responsible alcohol use.

- Identify related issues that may affect the relationship between parenting and adolescent alcohol consumption.

Prior to the review of relevant research, an account of the study's search strategies is provided, and some of the critical methodological issues are discussed; these are covered in Section 2. Material is presented in Section 3 on the prevalence of alcohol use by Australian adolescents to provide a picture of the extent of normative and problematic alcohol use.

Discussion of the parenting factors linked to adolescent alcohol use is organised according to the parenting model developed by Dishion and McMahon (1998) (referred to as the "Parenting model" throughout). This model is nested within the Social Development Model developed by Catalano and Hawkins (1996), which was used to highlight the broader ecological framework in which parenting and parent-adolescent interactions take place. (For a broader discussion of parenting itself and the factors which influence parenting, the report Parenting Information Project: Volume Two: Literature Review, published by the Australian Government Department of Family and Community Services in 2004, provides a comprehensive review.)

Using these theoretical guides, a review of the parenting behaviours and beliefs that have been shown to influence adolescent alcohol use is provided in Section 4. These include: parental monitoring; parental behaviour management; parent-adolescent relationship factors; and parental norms, values and goals.

An emphasis has been placed on longitudinal research, although cross-sectional and clinical studies are also included, particularly those of importance to the Australian context. Cross-sectional studies examine connections between predictors and outcomes which are both measured at the same point in time, whereas longitudinal studies follow the progress of a particular sample over an extended period of time, exploring across-time connections between predictors and outcomes. Additionally, previously unpublished research findings from the Australian Temperament Project are included to augment the Australian database.

Section 5 provides a discussion of some specific parental characteristics, such as parental use of alcohol, the biological transmission of alcohol dependence, and other ecological and environmental factors which affect parents and their parenting practices. The implications of broader cultural norms and laws for adolescent alcohol use are discussed and a review of research conducted with Indigenous adolescents is also provided in Section 5.

The contrasting roles of parents and peers are examined in Section 6. Some gaps and deficiencies in the literature are discussed in Section 7.

Following the analysis of relevant research findings, Section 8 presents intervention research that has attempted to manipulate parenting factors to reduce adolescent alcohol initiation or consumption. These experimental studies play a pivotal role in understanding the importance of parenting for adolescent alcohol use, as they provide the most direct evidence of "cause and effect" relationships.

A synthesis of the findings is presented in Section 9, and the review concludes with a discussion, in Section 10, of implications for research and policy, highlighting key conclusions that may be drawn from the findings reviewed.

1. The term "adolescent" is used here to describe young people aged from 11 to 21 years, covering the age span from the onset of puberty to the early adulthood stage of development.

2. Literature review methodology

This section outlines the search strategy and selection criteria adopted for this review, and provides descriptions of the types of studies reviewed. The methodological foundations upon which the reviewed research rest are then discussed.

Search strategy

Relevant research concerning parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use was identified by searching the biomedical and social sciences databases for primary research material. A total of 18 research databases were searched for publications from 1990 through to the present (2004), with key articles obtained primarily from PsychINFO, MEDLINE, ERIC, and The Cochrane Library. A complete list of the databases searched is included in Appendix 1.

In order to ensure that relevant studies were not missed, the search terms remained broad. These were "parenting or family", plus "adolescent or youth", plus "alcohol" anywhere in the title or abstract. No language restrictions were employed. Studies were eligible for consideration in this review if: (a) the focus of the study was adolescent alcohol use, or substance use (providing alcohol use was measured separately); and (b) there was at least one parenting variable measured.

To capture unpublished Australian research, personal contact was made with key researchers at universities and research institutions across Australia. This included key personnel at the Australian Drug Foundation, the National Drug Research Institute, the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, and other research organisations. A complete list of the organisations contacted is included in Appendix 2.

Finally, a comprehensive search was made of Internet resources in Australia and internationally. A number of sites were searched, although the primary sites used were the Australian Drug Foundation's Drug Information Clearinghouse and the United States National Clearinghouse for Drug and Alcohol information. A complete list of the websites searched is provided in Appendix 3.

Selection criteria

The next step was a detailed examination of papers, and at this point studies were excluded if the parenting or adolescent measures were insufficiently described, or alcohol use was only a minor variable in the study, and therefore the study did not contribute important information to this review.

For the studies investigating direct associations between parenting and adolescent alcohol use, the review includes all peer reviewed longitudinal studies investigating parenting and adolescent alcohol use. Longitudinal studies were seen as a particularly valuable resource as they facilitate the testing of relationships between early events or characteristics and later outcomes, and enable the identification of developmental sequences and pathways, as well as the construction of theoretical models which can then be validated in future research. Cross-sectional studies which used large samples and methodologically sound research designs were also retained. Studies with methodological weaknesses arising from small convenience samples, few factors measured, or weak data analysis, were included only when they provided insights not available from more rigorous studies. For the qualitative studies, those studies that contributed new information or covered areas that had not been fully explored in quantitative studies were included. Due to the limited volume of Australian published studies, Australian quantitative and qualitative studies were included wherever possible.

For the review of intervention research, studies were retained if: they employed "control" or "no-treatment" groups; participants were randomly assigned to treatment and non-treatment groups; and the studies included pre-intervention measures as well as post-intervention or follow-up measures.

Study descriptions

As with much research in the area of parenting, the majority of studies were correlational - that is, they investigated statistical relationships between parenting factors and adolescent alcohol use, and interpreted the associations found as showing a direct impact of parenting on adolescent behaviour. The possibility of "mediated" effects, in which parenting impacts on adolescent alcohol use through the influence of an intervening variable (for example, peer influence), has been infrequently investigated. Thus, while most studies have investigated direct associations only, it should be noted that the findings reported may mask more complex relationships.

Overall, 26 cross-sectional and 30 longitudinal studies were included in this review. A small number of qualitative Australian studies were found, and these have been included in the text alongside the discussion of findings emerging from the quantitative studies. Only two intervention programs were found that met the eligibility criteria, that is, they had a treatment and control group; pre-test, posttest and follow-up stages; and positive outcomes. The results of these intervention studies follow the review of research studies. Due to the limited number of intervention studies available, a brief review of promising work has also been included.

Finally, this report includes data from the Australian Temperament Project. This is a large, longitudinal study which has followed children's psychosocial development from infancy into adulthood, investigating the contribution of personal, familial and broader environmental factors to adjustment and wellbeing. This project is one of very few large scale Australian longitudinal studies that contains data on parenting and adolescent alcohol use.2

Methodological considerations

Regarding the methodological foundations upon which the reviewed research rest, there are at least five key issues which must be kept in mind when considering the research outcomes. These are: (a) the nature of correlational research; (b) the measurement of parenting and adolescent variables; (c) the importance of considering the differing levels of alcohol use amongst adolescents; (d) the timing of data collections; and (e) the comparability of cross-cultural findings.

First, as noted previously, the majority of the research is correlational, and cannot therefore determine "cause and effect" relationships. To be confident about causal connections, research would require experimental manipulation of parenting factors under tightly controlled conditions - an approach not feasible in social research. Nevertheless, the correlational research is able to demonstrate significant statistical associations between adolescent alcohol use and parenting factors. Furthermore, the longitudinal studies are able to demonstrate the importance of parenting factors over time, and their weight and sheer volume make it clear that there are indeed significant across-time relationships between parenting behaviours and adolescent alcohol use. With regard to parent and adolescent programs designed to prevent adolescent alcohol use, a change in parental and/or adolescent behaviour patterns is considered essential to demonstrate program effectiveness.

Second, most research on parenting influences has used parent or adolescent reports, collected via self-completion questionnaires. A minority of studies have used observations to assess parenting behaviours. Parental reports reflect parental perceptions, and hence may provide only a partially accurate portrayal of parental behaviours, as they are affected by self-enhancing biases and social desirability. Thus, studies which include parental reports and observational measures often report relatively low rates of agreement between these two sources of information (for example, Smart, Sanson, Toumbourou, Prior and Oberklaid 2000). Equally, adolescent reports are affected by adolescents' perceptions, and research has demonstrated that adolescents generally have a more negative view of their families than do their parents, and they see their families as less cohesive (Noller 1994). Thus, in this review of mainly self-report studies, results should be tempered by the notion that parents tend to have a positive bias, while adolescents have a negative bias.

Few studies have collected parent and adolescent data together. Information from multiple informants can provide a more complete picture, although again, there may be relatively low rates of agreement between the differing respondents. It can be valuable to obtain information from both parents and adolescents because they generally do not report the same level of problems in their interactions and the views of one may counterbalance those of the other. The few studies that have gathered data from both parties suggest that the concordance between adolescent and parent reports tends to be quite low, even when using identical measures. There is also evidence that concordance between parent and adolescent reports decreases as adolescent age increases. Therefore, younger adolescents are likely to report greater parental involvement and more agreement with parents.

Third, it is also likely that if adolescent alcohol use reaches problem levels, adolescents' self-reports of parenting behaviours will be influenced by negative attributions in family interactions and these adolescents are likely to report that their parents are less involved. Thus, it is possible that a somewhat biased view of parental behaviours might be obtained from adolescents with entrenched patterns of risky alcohol use. The research looks at adolescent alcohol use at several levels, including initiation of use, the age at first use, the pattern of regular use, and high risk alcohol use and misuse. Where the level of adolescent alcohol use has been measured alongside a parenting factor, it has been highlighted in this report.

Fourth, it is not always clear in the research when the data were collected, but the timing of data collections, particularly of adolescent self-reports of alcohol use, may have an important bearing on the results. For example, in Australia the fourth term of the school year coincides with end-of-year parties and summer celebrations. It is highly likely that adolescents at this time of the year would report a greater use of alcohol than they would during other parts of the year. Unfortunately the timing of data collection is generally not included in the research studies.

Finally, this review aimed to summarise both the Australian and international literature, although because of the limited number of Australian studies which possess both parenting and adolescent alcohol use data, the international research was relied on quite heavily. Studies included in this review were conducted in Canada (for example, Williams, McDermitt and Bertrand 2003), New Zealand (for example, Ferguson, Horwood and Lynskey 1995), and Scandinavian countries (for example, Bjarnason et al. 2002), although research conducted in the United States predominates.

There are two key issues to consider when comparing Australian and United States research: first, whether adolescents in Australia display similar patterns of alcohol use when compared with adolescents in the United States and, second, the comparability of Australian and United States populations in terms of the mechanisms of parenting, the ways in which parents influence their adolescents, and parental and cultural norms concerning adolescent alcohol use. These issues are discussed further in Section 4 and Section 7.

2. The Australian Temperament Project (ATP), involving a representative sample of over 2400 Victorian families, commenced in 1983 at a child age of four to eight months. A total of 13 waves of data have been collected by mail surveys over the first 20 years of the children's lives, with information provided by parents, maternal and child health nurses, teachers and, from the age of 12 years onwards, the children themselves. The study has focused primarily on the children's development and wellbeing. From early adolescence onwards, adolescents have reported on their recent use of substances, along with many other aspects of life.

3. Alcohol: Age of initiation, levels of use, and risky use

Before proceeding with a discussion of parenting influences, it is necessary to set the scene by discussing rates and levels of alcohol use among Australian adolescents. This section provides an overview of information about: the age at which Australian adolescents commence drinking; levels of adolescent alcohol consumption, distinguishing between "moderate" and "risky" levels of use; the risks associated with alcohol consumption; adolescents' views of alcohol and their reasons for drinking; their source of access to alcohol; and the settings in which adolescent alcohol use takes place. The section ends with a brief comparison of Australian and United States trends in adolescent alcohol use.

Initiation and consumption levels

Alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents before the legal age of 18 years is the norm, rather than the exception. The Australian School Students' Alcohol and Drug Survey (hereinafter ASSAD) has provided repeated population-based data on the alcohol consumption patterns of Australian adolescents (White and Hayman, in press). The most recent survey on 24,403 secondary students aged 12-17 years shows that by the age of 14 years 90 per cent of Australian adolescents have tried a full glass of alcohol, and 95 per cent of 17 year olds have tried a full glass (White and Hayman, in press).

The 2001 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (hereinafter NDSHS) conducted by Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found that young people aged 14-24 years reported that their first glass of alcohol was consumed at around 14.6 years for males, and 14.8 years for females (AIHW 2003a). Other large surveys have also found that for the majority of adolescents, their first full glass of alcohol is consumed somewhere between their 14th and 15th year (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003). Therefore it seems that most adolescents begin experimenting with alcohol at approximately 14-15 years of age.

Once their first glass of alcohol is consumed, a sizeable proportion of adolescents appear to progress to regular drinking. With regard to repeated consumption, the NDSHS showed that 20 per cent of males and 17 per cent of females aged 14-17 years were classified as regular weekly drinkers (AIHW 2003a), and two-thirds of adolescents aged 14-17 years had consumed a full glass of alcohol in the past 12-months.

As shown in Table 1, there are differences in adolescent consumption between the NDSHS and ASSAD data. The rates of regular drinking are considerably higher in the ASSAD data which show that 34 per cent of adolescents had consumed alcohol in the past week, with the rates being slightly higher rates for males (37 per cent) than females (31 per cent). These differences are likely to be attributable to survey content and methodology. For example, there were differences between the two studies in the phrasing of the questions, the age of respondents, and the place where the data were collected (at home versus at school).

| NDSHS survey 2001: 14-17 years | Males % | Females % |

|---|---|---|

| Regular (weekly) | 19.8 | 17.1 |

| Occasional (past year) | 44.3 | 51.6 |

| Ex-drinker | 6.6 | 4.3 |

| Never a full glass of alcohol | 29.2 | 27.0 |

| ASSAD survey 2002: 12-17 years | Males % | Females % |

| In past week | 37 | 31 |

| In past month | 15 | 16 |

| In past year | 23 | 25 |

| Never | 11 | 13 |

Source: AIHW (2003a); White and Hayman (in press).

Comparisons between the 1999 and 2002 ASSAD survey data show that there was no significant change in adolescent alcohol use in the past three years. Longer-term comparisons show that while consumption among 12-15 year olds was similar in 2002 and 1999, these rates were significantly higher than in 1996 and 1993. For the 16-17 year age group, the proportion of drinkers in 2002 was slightly lower than in 1999, but overall the rate has remained relatively stable since the early 1990s (White and Hayman, in press). In both age groups (12-15 and 16-17 years), the proportion of adolescents who drank at risky levels remained relatively stable from the 1990s survey period through to the current 2002 survey wave (White and Hayman, in press).

Delayed onset

There is some evidence to suggest that the later adolescents delay their first alcoholic drink, the less likely they are to become regular consumers. Adolescents who start later are more likely to report that they are light or occasional drinkers, and they are less likely to binge (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003). In the United States, the National Longitudinal Epidemiologic Survey of 27,616 young people (cited in Spoth, Lopez Reyes, Redmond, and Shin 1999) shows that the lifetime alcohol dependence rates of those people who initiate alcohol use by age 14 are four times as high as those who start at age 20 years or older. Furthermore, the odds of dependence decrease by 14 per cent with each additional year of delayed initiation (cited in Spoth et al. 1999).

Longitudinal data from New Zealand also demonstrate that the commencement of alcohol use in early adolescence increases the likelihood of the subsequent development of high risk use, independent of other influences (Fergusson, Horwood and Lynskey 1995). Young people who begin using alcohol at a younger age are more likely to progress to regular use in adolescence (Fergusson, Lynskey and Horwood 1994). Australian longitudinal studies have demonstrated that regular drinking in adolescence is an important risk factor for the development of abusive, dependent (Bonomo et al. 2001) and risky (Toumbourou Williams, White et al. 2004) patterns of use in young adulthood.

Risky adolescent alcohol use

The 2001 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines for alcohol use recommend that males should, on average, drink no more than four standard drinks per day and on any particular day, no more than six standard drinks; females should drink no more than two standard drinks per day on average, and four standard drinks on any one day. As well, this level of use should occur on no more than three days per week. Definitions are also provided of "risky" and "high risk" patterns of alcohol use, which are further separated into short-term and long-term harms (see Table 2 for description).

| Type of risk | Risky alcohol use | High risk alcohol use |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term harms | ||

| Males | 7-10 drinks on any one day | 11+ drinks on any one day |

| Females | 5-6 drinks on any one day | 7+ drinks on any one day |

| Long-term harms - Males | ||

| - on an average day | 5-6 drinks per day | 7+ drinks per day |

| - overall weekly level | 29-42 drinks per week | 43+ drinks per week |

| Long-term harms - Females | ||

| - on an average day | 3-4 drinks per day | 5+ drinks per day |

| - overall weekly level | 15-28 drinks per week | 29+ drinks per week |

Source: NHMRC (2001).

It is important to note that these Australian guidelines were developed for healthy adults, not adolescents. In fact, adolescents' physical immaturity (for example, smaller body size), and inexperience with alcohol make young people more susceptible to the harmful effects of alcohol than adults. Thus, for the same dose of alcohol, more harm can result for an adolescent than an adult.

The NDSHS reports that for the Australian population as a whole, alcohol is the second greatest cause of drug-related deaths and hospitalisations (AIHW 2002). Amongst adolescents, one-third (34.4 per cent, or 387,400) of 14-17 year olds had put themselves at risk of alcohol-related harm in the past 12 months on at least one occasion, and this is similar to the overall population rate of 34.4 per cent (AIHW 2002).

According to a recent report from the National Drug Research Institute on drinking patterns among 14-17 year olds, 85 per cent of adolescent alcohol consumption is consumed at a risky or high-risk level for acute harm (Chikritzhs, Catalano, Stockwell, Donath, Ngo, Young and Matthews 2003). These findings suggest that when Australian adolescents consume alcohol, most do so at risky levels. Furthermore, this risk of harm occurs regularly, with 18 per cent of young people reporting drinking at levels of risk for short-term harms on a weekly basis (increased from 15 per cent in 2002), and 50 per cent drinking at these levels on a monthly basis (as compared with 42 per cent in 2002) (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003).

The rate of long-term risky alcohol consumption has recently increased among females aged 14-17 years, rising from 1 per cent in 1998 to 9 per cent in 2001 (Chikritzhs et al. 2003). However, the rate of risky long-term alcohol use among males aged 18-24 years has decreased, falling from 9 per cent in 1998 to 6 per cent in 2001. These findings might reflect fluctuations rather than long-term trends, and it will be important to continue measuring consumption trends to establish whether more enduring shifts in alcohol use are taking place.

Harms associated with adolescent alcohol use

Binge drinking can cause bowel, central nervous system, and psychological problems, and is also related to a high risk of injury, assault, road accidents, fights, other violence, sexual assault, and unprotected sex (AIHW 2003a). Serious binge drinking may result in alcohol poisoning, and can lead to coma or death (AIHW 2003a). While under the influence of alcohol, 26 per cent of young people reported verbally abusing someone, 13 per cent had driven a car, and 12 per cent had created a public disturbance (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003). In this Victorian survey, 41 per cent of young people reported being abused by someone under the influence of alcohol, while 20 per cent had been fearful of a person who was under the influence of alcohol (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003).

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW 2002), alcohol-induced memory lapses, where alcohol was consumed and events were unremembered afterwards, were more prevalent in adolescents aged 15-19 years than in adults. The NDSHS found that 4.4 per cent of adolescents reported alcohol-induced memory lapses occurred at least weekly, and 10.9 per cent reported this occurred at least monthly. The comparison rates for adults are considerably lower, with adults aged 20-29 years at 3.6 per cent for weekly rates and 7.7 per cent monthly. The prevalence of memory lapses following alcohol abuse continues to decline further with age (AIHW 2002). It has also been suggested that risky levels of alcohol use during adolescence can have deleterious effects on the developing brain (Scott and Grice 1997), and this is exacerbated by faster absorption rates and a less efficient metabolic system during this stage of development.

The ASSAD report shows that in both age groups (12-15 and 16-17 years) the proportion of adolescents who drink at high risk levels has remained relatively stable from the surveys conducted in the 1990s through to the current 2002 data collection wave (White and Hayman in press).

Adolescents' reasons for drinking

Alcohol remains a socially acceptable drug in Australia. The report produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, entitled Australia's Young People: Their Health and Wellbeing (AIHW 2003a) shows that young Australians aged 14-24 years perceive that heroin and cannabis are problem drugs, but that alcohol, amphetamines, tobacco and ecstasy are not. Among young Victorians aged 16-17 years, 26 per cent describe alcohol use as "not wrong at all" for them, and 48 per cent described it as "a little bit wrong" (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003).

Of concern are recent survey results showing that adolescents' expectations of alcohol consumption are different from adults'. According to the Victorian Drug and Alcohol use survey of 6052 young people aged 18-24 years, 20 per cent of young people intended to get drunk when they drink (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003). Further, Chikritzhs et al. (2003) suggest the percentage of adolescents who intend to get drunk might in fact be considerably higher than these rates.

Where do adolescents consume alcohol? Where do they obtain it?

The location of adolescent consumption of alcohol is shown in Table 3, which again displays NSDHS and ASSAD data. The NSDHS data show that for adolescents aged 14-19 years who had consumed alcohol in the past 12 months, the most common location was private parties (males 67.8 per cent, females 70.2 per cent), followed by friends' homes (males 62.9 per cent, and females 63.9 per cent), or their own homes (males 61.5 per cent, females 61.1 per cent). The ASSAD data, which describes adolescent alcohol consumption within the past week, shows a similar pattern of consumption at home or parties, although consumption at friends' homes or in public places is lower. The relatively high rate of consumption in public places and in cars shown in the NSDHS data is of concern. (AIHW 2002)

These data do not clarify the social milieu in which alcohol is consumed. For example, when alcohol is consumed at home, it is probable (but not certain) that parents are present, but it remains unknown whether parents actively supervise their adolescent's alcohol consumption. Likewise, when alcohol is consumed outside the home, presumably this occurs in social settings with peers and may, or may not, involve adult supervision. These are important considerations, but generally, this information has not been supplied.

The legal age for purchasing alcohol in retail outlets in Australia is 18 years, yet the majority of adolescents begin drinking before this. The ASSAD survey of 24,403 students in Years 7-12, found that parents were the most common source of alcohol, with 38 per cent of students reporting their parents gave them their last drink (White and Hayman, in press). Furthermore, this survey found that it was more likely that parents would provide alcohol to younger rather than older students, with rates of 42 per cent in the 12-15 year group compared with 32 per cent in 16-17 year group. It appears that older students may be able to obtain alcohol from other sources.

| NSDHS 2001 14-19 years (in past year) | ASSAD 2002 12-17 years (in past week) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Males % | Females % | Males % | Females % |

| In my home | 61.5 | 61.1 | 36 | 34 |

| At friend's house | 62.9 | 63.9 | 14 | 15 |

| At private parties | 67.8 | 70.2 | 29 | 32 |

| At rave/dance parties | 22.9 | 24.5 | ||

| At restaurants/cafes | 22.4 | 25.5 | ||

| At licensed premises | 37.1 | 38.8 | ||

| At school/TAFE/Uni | 6.2 | 3.4 | ||

| At workplace | 5.8 | 2.7 | ||

| In public places | 14.1 | 10.6 | 4 | 4 |

| In a car | 12.2 | 7.0 | ||

| Somewhere else | 8.3 | 7.2 | ||

Source: AIHW (2002);White and Hayman (in press).

Other surveys also report that a considerable number of adolescents obtain alcohol through their parents. The 2003 Victorian Youth Alcohol and Drug Survey found that parents had purchased alcohol for half of the adolescents who had drunk alcohol and were under 18 years (51 per cent) (Premier's Drug Prevention Council 2003). The NSDHS data showed that just over two-thirds of persons aged 14-17 years obtained their alcohol through a friend or relative (69.2 per cent) (AIHW 2002). Similarly, Taylor and Carroll (2001) found that 29 per cent of adolescents aged 15-17 years reported that their parents had provided alcohol. These surveys show that between 30 per cent and 50 per cent of adolescents who drink obtain their alcohol from their parents.

Australian and United States trends compared

One methodological issue noted earlier was whether Australian patterns of adolescent alcohol use are similar to those of the United States. Epidemiological research has shown that at a population level, alcohol consumption patterns in Australia and the United States are not dissimilar, but there can be some variation in use. International comparisons of alcohol consumption for the total population (adults, adolescents and children) reveal that Australians consume more alcohol, with consumption rates of 7.8 litres per capita, compared with the United States at 6.7 litres, Canada at 6.6, and the United Kingdom at 8.4 (AIHW 2003b). Assessing behavioural differences between young people in the different countries is more complicated.

A major source of data concerning American trends in youth substance use is the Monitoring the Future (MTF) youth survey. This study has provided annual estimates of high school student substance use since 1975. Additionally, the MTF survey was extended in 1995 and 1999 to countries in Europe. In general, rates of alcohol and tobacco use were considerably higher for European students than students in the United States, while rates of illicit drug use were higher in the United States (Hibell et al. 2000).

In one of the few matched studies comparing Australia and America, Beyers and colleagues (2004) reported clear differences across the two countries in students' levels of substance use. At the same age, there were markedly higher levels of youth alcohol and tobacco use in the Victorian sample and slightly higher marijuana and other illicit drug use among the United States sample. Similar inter-country differences were reported in the early 1990s in a comparison presented by Makkai (1994). Similarly, Toumbourou (2004) presented findings from carefully matched large state surveys conducted in 2002 which compared students in Victoria and Washington State. This comparison revealed, once again, a pattern of markedly higher rates of alcohol use for students in Victoria relative to Washington State in Grade 5 (primary school) and Years 7 and 9 (secondary school).

Comparative studies in older age groups have also tended to show higher rates of alcohol use in Australia relative to the United States (Makkai 1994), however there has been at least one comparison inconsistent with this trend. A comparison of alcohol use for young people aged 14-17 years responding to the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing Survey (NSMHWB) and the United States Youth Risk Behaviour Survey on which the Australian survey was modelled, revealed differences in consumption for adolescent females but not for males. For adolescent males the lifetime prevalence of alcohol use was 73 per cent for Australians, and this was similar to the United States rate of 79 per cent. However, there was a significant difference for females, with prevalence of lifetime alcohol use for Australian female adolescents at 70.6 per cent, compared with American females at 80.7 per cent (Pirkis, Irwin, Brindis, Patton and Sawyer 2003).

Despite this apparent similarity between adolescent alcohol use in Australia and the United States, Pirkis and colleagues (2003) cautioned that errors can occur when cross-cultural comparisons are based on survey data that had not been matched in content and context. To demonstrate the errors that can occur with these comparisons, Pirkis et al. compared the prevalence rates as shown on the Australian NSMHWB, with the American Youth Risk Behaviour Survey, and the American NHSDA survey. They found that when the NHSDA survey data was used, the rates of alcohol use appeared much lower in the United States than Australia whereas, as described earlier, results were quite similar when the Australian NSMHWB trends were compared to the American Youth Risk Behaviour Survey data (Pirkis et al. 2003). Therefore, for the cross-cultural comparisons, caution is always required.

There has been limited investigation of inter-country differences in the harms associated with alcohol use and findings are mixed. Jernigan (2001) presented inter-country comparisons across a range of indicators that are known to be influenced by youth alcohol use. With respect to mortality related to motor vehicle crashes, the death rates for people aged under 25 in 1997 were higher in the United States (5.79 per 100,000) than in Australia (3.92 per 100,000). However, suicide rates were higher in Australia (3.14 per 100,000) than in the United States (2.06 per 100,000).

Summary

This brief overview has shown that alcohol use is common among young Australians, and that most begin experimenting with alcohol by the age of 14-15 years. Once they begin drinking, a large proportion become regular consumers of alcohol. The evidence suggests that delaying the onset of drinking reduces longterm consumption levels into adulthood. Adolescents reported that they tended to drink to get drunk, and that they put themselves at considerable risk when they drank. Adolescents tend to drink at home, at parties, or at friends' homes. Finally, it was shown that a considerable proportion of adolescents (up to one half) obtain their alcohol from parents.

With regard to cross-national comparisons, the available evidence suggests that school age adolescents in the United States have lower rates of alcohol and tobacco use but higher illicit drug use by comparison with youth of similar ages in Australia and the majority of Europe. Although differences in the young adult age group may be less pronounced at a population level, alcohol consumption rates appear lower in the United States. One would expect that cultural and social norms might contribute to consumption patterns, and these differences should be considered when interpreting overseas studies within an Australian context.

4. Parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use

It is widely believed that parents have little influence on adolescents' alcohol use, and there has been a common assumption that the influence of peers is more important than parental influence (Johnson and Johnson 2000). The research to be reviewed here does not support this notion. The findings reviewed are consistent with those of many other studies which have investigated associations between parenting behaviours or parental characteristics and a range of child and adolescent problems, and have shown links between several parenting factors and internalising and externalising behaviour problems in children and adolescents.

Framework for reviewing parenting literature

The purpose of this review is to identify the particular parenting factors that are linked to adolescent alcohol use. To do this, a theoretical model of parental influence developed by Dishion and McMahon (1998) will be used. This is a Social Interactional model of parenting and it provides a framework to demonstrate the relevance of parenting characteristics to adolescent behaviours. This conceptual model of parenting is developed from a large body of research, which has shown that several key parenting factors influence child and adolescent behaviour (for example the body of work in the Oregon Youth study, Patterson, Reid and Dishion 1992).

The Social Interactional model is shown in Figure 1. At the centre of the model is the parent-child relationship, which forms the foundation of effective parenting. Therefore, research that considers how parents may influence adolescent alcohol use should consider the contribution of quality of parent-adolescent relationships. The apex of this model is represented by a parent's motivations, and this is a compilation of parental beliefs, norms, values, and goals. It has been shown that parent's expectations of parenting, along with their expectations of their child, are critical to parenting behaviours (Patterson 1982). Finally, the social interactional model of parenting depicts the role of parental monitoring and parents' management of adolescent behaviour, but they are interrelated with parent-adolescent relationship quality and parental motivation, goals, values and beliefs. Using this framework, it becomes evident that parenting factors are dynamically interrelated, for example, parental values are likely to influence parenting behaviour management skills.

While Dishion and McMahon's model is used as a tool to organise the diverse array of findings, it should be noted that relationships are dynamic, and the importance of examining parent-adolescent interactions within a bi-directional paradigm should also be considered. Research has shown that parents influence the behaviour of their adolescents, but the reverse also occurs, with adolescents exerting influence that changes the behaviour of their parents. The longitudinal body of work by Capaldi (2003), Capaldi and Patterson (1989), Dishion, Capaldi, Spracklen, and Fuzhong (1995), Patterson et al. (1992), and Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber (1984), over an 11-year period, provides substantial evidence of the multi-faceted nature of parenting, and the bi-directionality of influences. Other researchers have also demonstrated the bi-directional nature of parent-adolescent relationships (Brody 2003), and more recently this has also been demonstrated in intervention work using rigorous experimental methodology (Dishion, Nelson and Kavanagh 2003).

In addition to the bi-directional nature of parent-adolescent relationships, the ecology of the family is also crucial, and the Social Development model (Hawkins, Catalano and Miller 1992) is used as a framework for understanding broader family and environmental influences.

This model is a general theoretical model of behaviour which integrates social learning theories and control theory, and has been developed to provide a framework for understanding the role of family, peers, and community in the development of various adolescent behaviour problems (Catalano and Hawkins 1996; Hawkins et al. 1992). Thus, the model proposes that adolescents who are poorly attached to families, schools and community, but are more strongly attached to antisocial peers, are more likely to engage in problem behaviours such as substance use and antisocial behaviour.

This model has been used to measure positive and negative influences using a risk and protective conceptual framework. Therefore, throughout this review, where parenting factors are examined, there is an underlying assumption that adolescents can and do change the behaviour and attitudes of their parents, and that the ecology surrounding the adolescent and parent exerts further influence.

Figure 1. Social interactional parenting model

Source: Dishion and McMahon (1998)

Summary

Two theoretical models are used to provide a framework in which to understand parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use.

First, the Social Interactional model of Dishion and McMahon (1998) is used to understand the importance of a range of parenting skills and behaviours, in particular parent-adolescent relationship quality, parental monitoring, parents' management of adolescent behaviour, and parents' norms, goals and values.

Second, the Social Development model of Catalano and Hawkins (1996) is used to highlight the ecological context surrounding the parent and adolescent, focusing on broader aspects of family environment and the influence of peers.

Overview of findings

Tables 4 and 5 summarise the findings regarding the most consistent associations found between aspects of parenting and adolescent alcohol use. Other findings which emerged less frequently are described in the text, rather than displayed. Table 4 displays the results emerging from the cross-sectional studies, and Table 5 the results from the longitudinal studies. These tables present an overview of the results, and each parenting factor is discussed subsequently in this review.

In the tables, the arrows depict the effect that the parenting factor was shown to have on adolescent alcohol use. For example, in the parental monitoring column, the downward arrows indicate that high levels of this factor are associated with lower adolescent alcohol use. The final column in each table denotes whether the study was conducted with Australian participants, and reveals that there has been little Australian research on this issue to date. Following the Dishion and MacMahon (1998) model, the review begins with a discussion of the findings concerning parental monitoring, which is followed by a review of findings relating to parents' behaviour management, parent-adolescent relationship quality, and parental norms and attitudes. Broader aspects of the family environment are then reviewed, such as parental alcohol use and abuse, family structure, and family socio-economic background. The impact of cultural norms and laws, and findings emerging from indigenous samples, are described. Parenting influences are compared with peer influences, and gaps and deficiencies in the research are discussed. Finally, the results of intervention studies are reviewed.

The table can also be viewed on page 34 of the PDF.

| Cross-sectional studies | Biological history of alcoholism | Familial alcohol abuse | Parents regular drinkers | Parents disapprove or negative norms | Parents provide alcohol | Higher parental monitoring | Parents permissive | Good parent-child relationship | Positive behaviour management | Harsh parenting or high conflict | Mother and father together | Responder | Australian participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. (1999) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Beck,Boyle & Boekeloo (2003) | ? | ? f | A | ||||||||||

| Beck, Ko & Scaffa (1997) | ? | P | |||||||||||

| Bjarnason et al. (2002) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Bonomo et al. (2001) | ? | A | 3 | ||||||||||

| Borawski, et al. (2003) | ? | ? | ? | A | |||||||||

| Brown et al. (1999) | ? | ? | AP | ||||||||||

| Chassin et al. (1993) | ? | ? | AP | ||||||||||

| DiClemente et al. (2001) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Epstein, Botvin & Spoth (2003) | ? g | A | |||||||||||

| Flannery, Vazsonyi, Torquati & Fridrich (1994) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Hawthorne (1996) | ? | A | 3 | ||||||||||

| C. Jackson (2002) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Keefe (1994) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Letcher et al. (in press) | ? | ns | AP | 3 | |||||||||

| X. Li, Feigelman & Stanton (2000) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Neighbors, Clark, Donovan & Brody (2000) | ? ? g | AP | |||||||||||

| Quine & Stephenson (1990) | ? | A | 3 | ||||||||||

| Rai et al. (2003) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Sale, Sambrano, Springer & Turner (2003) | ? | ? | A | ||||||||||

| Smith & Rosenthal (1995) | ? | A | 3 | ||||||||||

| Svensson (2000) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Vicary, Snyder & Henry (2000) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| White & Hayman (in press) | ? | A | 3 | ||||||||||

| P.S. Williams & Hine (2002) | ? | ? | ? | A | 3 | ||||||||

| Wood, Read,Mitchell & Brand (2004) | ? | ? | ? ? | A | |||||||||

| J.Yu (2003) | ns | ? | A | ||||||||||

| Note: ? or ? = direct predictive effect of parenting variable, ? or ? = indirect (mediational) effect of parenting variable, ? ? or ? ? = variable has direct effect and also an indirect effect by interacting with another factor (moderator). g = gender differences, a = age effects, f = father only, m = mother only, ns = not significant, P = Parent respondent, A = Adolescent respondent, 3 = Australian sample | |||||||||||||

The table can also be viewed on page 35 of the PDF.

| Longitudinal studies | Biological history of alcoholism | Familial alcohol abuse | Parents regular drinkers | Parents disapprove or negative norms | Parents provide alcohol | Higher parental monitoring | Parents permissive | Good parent-child relationship | Positive behaviour management | Harsh parenting or high conflict | Mother and father together | Responder | Australian participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ary, Duncan, Biglan et al. (1999) | ? ? | ? | ? | AP | |||||||||

| Ary, Duncan, Duncan & Hops (1999) | ? ? | ? | ? | AP | |||||||||

| Barnes & Farrell (1992) | ? | ? | ? | ? | AP | ||||||||

| Barnes, Reifman, Farrell & Dintcheff (2000) | ? | ? | ? | A | |||||||||

| Baumrind (1991) | ? | ? | AP | ||||||||||

| Bray, Adams, Getz & Baer (2001) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Bray, Adams, Getz & Stovall (2001) | ? ? | ? ? | ? ? | A | |||||||||

| Brody, Ge, Katz & Ileana (2000) | ? | AP | |||||||||||

| Brody & Ge (2001) | ? | ? | ? | AP | |||||||||

| Chilcoat & Anthony (1996) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Dishion, Capaldi & Yoerger (1999) | ? | ns | ? | AP | |||||||||

| Duncan, Duncan, Biglan & Ary (1998) | ? | ? | A | ||||||||||

| Ennett, Bauman, Foshee et al. (2001) | ? | AP | |||||||||||

| Guo, Hawkins, Hill & Abbott (2001) | ? | ? | ns | A | |||||||||

| Jackson, Henriksen & Dickinson (1999) | ? | ? | A | ||||||||||

| Kosterman, Hawkins, Guo, Catalano & Abbott (2000) | ? | ? | ? | A | |||||||||

| F. Li, Duncan & Hops (2001) | ? | ? | A | ||||||||||

| C. Li, Pentz & Chih-Ping (2002) | ? ? | A | |||||||||||

| X. Li, Stanton & Feigelman (2000) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Ouellette, Gerrard, Gibbons & Reis-Bergan (1999) | ? | ? | AP | ||||||||||

| Oxford, Harachi, Catalano & Abbott (2001) | ? | ? | A | ||||||||||

| Pedersen (1995) | ns | ? | ? g | A | |||||||||

| Prior, Sanson, Smart & Oberklaid (2000) | ? | AP | 3 | ||||||||||

| Reifman, Barnes, Dintcheff et al. (1998) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Rodgers-Farmer (2000) | ? ? | A | |||||||||||

| Steinberg, Fletcher & Darling (1994) | ? | A | |||||||||||

| Stice, Barrara & Chassin (1998) | ? | ? | ns | ? | ns | AP | |||||||

| Thomas, Reifman, Barnes & Farrell (2000) | ? | ? | A | ||||||||||

| Webb, Bray, Getz & Adams (2002) | ? g | A | |||||||||||

| B. Williams, Sanson, Toumbourou & Smart (2000) | ? | ? | AP | 3 | |||||||||

| Note: ? or ? = direct predictive effect of parenting variable, ? or ? = indirect (mediational) effect of parenting variable, ? ? or ? ? = variable has direct effect and also an indirect effect by interacting with another factor (moderator). g = gender differences, a = age effects, f = father only, m = mother only, ns = not significant, P = Parent respondent, A = Adolescent respondent, 3 = Australian sample | |||||||||||||

Parental monitoring

The most widely accepted definition of parental monitoring is: parental awareness of the child's activities, and communication to the child that the parent is concerned about, and aware of, the child's activities (Dishion and McMahon 1998). Thus, the term "parental monitoring" describes parental efforts to influence adolescents' independent use of free time via the establishment of boundaries for appropriate behaviour and communications with adolescents about their activities when away from parents.

More recently the definition of monitoring has been fiercely debated in the literature with two opposing views presented. This debate centres on the direction of effects, and whether the greatest influence in monitoring is driven by parenting behaviours, or by adolescent willingness to be monitored. However, the complexities of this debate are beyond the scope of this present report (see Hayes, 2003 for a review), and the Dishion and McMahon view has been used because it provides a sound definition with an influential research base.

There are numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies linking poor parental monitoring with adolescent alcohol and substance use. Thus, 14 of the 26 cross-sectional studies, and 17 of the 30 longitudinal studies reported connections between parental monitoring and adolescent alcohol use. A recent review of 113 studies where parental monitoring was a key variable (Hayes 2004) revealed that lower monitoring has been correlated with externalising problem behaviours in adolescents, including antisocial behaviour, "deviant" peer associations3, substance use, and sexual risk-taking. Internalising problems and related behaviours have also been linked to poor monitoring, including psychological maladjustment, lowered self-esteem, and poor academic achievement. Furthermore, in studies of family functioning, poor monitoring is associated with parent-adolescent relationship difficulties, family dysfunction, and social disadvantage (Dishion and McMahon 1998, Patterson et al. 1992). The following studies have the most rigorous and relevant findings in relation to adolescent alcohol use and the role of parental monitoring.

The relationship between increased adolescent alcohol use and lower parental monitoring has been demonstrated consistently in several large longitudinal studies (Barnes and Farrell 1992; Barnes et al. 2000; Guo et al. 2001; Reifman et al. 1998; Thomas et al. 2000). Barnes and colleagues (2000) found high parental monitoring was associated with lower alcohol use across a 6-wave longitudinal study of randomly sampled adolescents, commencing with measures taken at 13 years of age. They also found higher monitoring reduced the upward trajectory of alcohol misuse across adolescence. Guo et al. (2001) followed 755 adolescents from age 10-21 years, and found high monitoring, as well as clearly defined rules at ten years of age, predicted lower alcohol abuse and dependence at 21 years. In this study higher monitoring was associated with lower rates of alcohol abuse (odds ratio of 0.78) using odd ratios4 adjusted for internalising and externalising behaviours at age ten years (Guo et al. 2001).

DiClemente et al. (2001) reported female adolescents, aged 14-18 years, with poor parental monitoring were 1.4 times more likely those who received closer monitoring to have a history of alcohol use. They also found lower parental monitoring increased the risk of alcohol use in the past 30 days by 1.9 times. In a cross-sectional analysis of the Australian Temperament Project dataset, Letcher and colleagues (Letcher, Toumbourou, Sanson, Prior, Smart and Oberklaid, in press) investigated the separate and combined influence of differing facets of temperament style and types of parenting behaviours in the prediction of adolescent problem behaviours.

With regard to multi-substance use, adolescents who were temperamentally low in persistence or high in negative reactivity were found to be at a greater risk if monitoring was low, indicating that low monitoring was particularly influential for those who were temperamentally at-risk. However, even when optimal parenting was evident (for example, high monitoring), prevalence of behaviour problems was generally higher among those at greatest temperamental "risk" or vulnerability (such as high volatility, reactivity, intensity). However, for adolescents with an easier temperament style, optimal compared with adequate parenting seemed to have little impact and "good enough" parenting appeared to suffice. These findings suggest that it was particularly important for monitoring to be of high quality rather than merely adequate for more difficult adolescents, whereas the presence of high versus adequate monitoring was not so crucial for less difficult adolescents.

A four-year longitudinal study with a sample of 926 children of eight to ten years of age, used survival analysis to test the sustained impact of monitoring over time (Chilcoat and Anthony 1996). (Survival analysis investigates the time that elapses between the first point of measurement and the occurrence of a subsequent event, and allows an exploration of the factors that might influence the timing of the subsequent event). Estimates from this research indicated that children in the lowest quartile of monitoring began alcohol use at a younger age than children in the higher quartiles of monitoring. Children receiving the poorest monitoring were found to be two years ahead in terms of the commencement of alcohol use (Chilcoat and Anthony 1996). This study provided strong evidence that effective monitoring of pre-adolescents can delay the onset of alcohol initiation.

In a series of longitudinal studies, parental monitoring was shown to have a direct effect on problem behaviours (including alcohol use), but also to have an important indirect effect through deviant peers (Ary, Duncan, Biglan et al. 1999; Ary, Duncan, Duncan and Hops 1999). Duncan and colleagues (1998) used sophisticated modelling techniques (multivariate latent growth curve modelling) in a two-year longitudinal study to examine the relationship between monitoring, peer associations, and problem behaviours. They found that high levels of parent-child conflict and low levels of parental monitoring were associated with deviant peer relationships and a greater likelihood of adolescent substance use. In these studies the use of substances was found to co-vary, so that an increase in one substance over time also increased the likelihood of other substance use. Individuals who experienced increasing levels of conflict with parents over an 18- month period had faster acceleration of substance use. Additionally, increases in deviant peer associations over the two-year period were associated with faster increases in substance use. Other researchers have also found the interplay between monitoring and peer association is important (Baker et al. 1999; Dishion et al. 1999; Rai et al. 2003), and this research will be examined in detail later.

Parental awareness of adolescent alcohol use

While much of the research into parental monitoring has focused on parents' knowledge of their child/adolescent's whereabouts and activities, another important aspect of monitoring in relation to adolescent alcohol use is parental awareness of their adolescent's alcohol consumption. Findings regarding parental awareness of alcohol use are now reviewed.

Research has shown that adolescents tend to spend less time with their family than when they were children, and therefore there is a greater opportunity for them to consume alcohol without parental knowledge. From age of 10 to 18 years there is a dramatic drop in the time adolescents spend in family activities, with time typically decreasing from 35 per cent to 14 per cent across this age span (Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, and Duckett 1996).

It appears that parents do not always know the level of alcohol consumed by their adolescent children; parents also consistently underestimate their children's level of alcohol use, and they tend to underestimate adolescents' smoking and other problem behaviours too. Data from the Australian Temperament Project on this issue are shown in Figure 2. These reveal that most parents (53.6 per cent) were very sure that their 17-18 year old children had not used alcohol to excess in the past month, there were 12.6 per cent of parents who were very sure their adolescent had drunk to excess, and 11.8 per cent who were somewhat sure they had.