Past Adoption Experiences

National Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

August 2012

Download Research report

Overview

This report presents the findings of the National Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices.

The aim of the study was to strengthen the evidence available to governments to address the current service needs of individuals affected by past adoption practices, including the need for information, counselling and reunion services.

In particular, the study has targeted a wide group of those affected by past practices, including mothers, fathers, adoptees, adoptive parents (and wider family members); and professionals currently working with affected individuals.

Findings from the Senate Inquiry into the Commonwealth Contribution to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices were also taken into account.

Key messages

-

The key needs identified by the study included: acknowledgement, recognition and increased community awareness of and education about past adoption practices and their subsequent effects;

-

specialised workforce training and development for health and welfare professionals to appropriately respond to the needs of those affected;

-

review of the current search and contact service systems, with a commitment to develop improved service models;

-

improved access to information through the joining of state and territory databases, governed by a single statutory body

Executive summary

The practices in Australia around the permanent transfer of parental legal rights and responsibilities from a child's birth parent(s) to adoptive parent(s) have varied over time. The Australian Senate noted in their report on the Commonwealth Contribution to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices (Senate Community Affairs References Committee, 2012; "the Senate Inquiry") that "adoption as it is now understood is a peculiarly twentieth century phenomenon" (p. 3).

Not only have adoption practices in Australia undergone considerable change, so too have society's responses to pregnancies outside of marriage and single motherhood. Until a range of social, legal and economic changes in the 1970s, unwed (single) women who were pregnant were encouraged - or forced - to "give up" their babies for adoption. The shame and silence that surrounded pregnancy out of wedlock meant that these women were seen as "unfit" mothers. The practices at the time, called "closed adoption", were seen as the solution. "Closed adoption" was where an adopted child's original birth certificate was sealed forever and an amended birth certificate issued that established the child's new identity and relationship with their adoptive family.

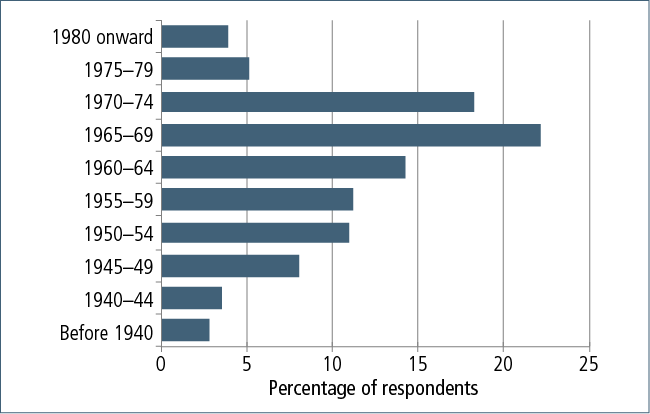

Given the prevalence of adoption in Australia in the second half of the twentieth century - particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s - a significant proportion of the population has had some experience of or exposure to issues relating to adoption.

The rationale for conducting the current study - the National Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices - is to improve the adequacy of the evidence base for understanding the issues and the needs of those affected.

Despite there being a wealth of primary material, there has been little systematic research on the experience of past adoption practices in Australia. The focus has also been on mothers' experiences of "forced adoption" and the experiences of adoptees, with less focus on fathers, adoptive parents and other family members.

The Department of Families, Housing Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) commissioned the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) to undertake the current study on behalf of the Community and Disability Services Ministers' Conference (CDSMC). It complements the Senate Community Affairs References Committee (2012) inquiry into the Commonwealth Contribution to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices. The Senate committee was charged with inquiring into the role, if any, of the Commonwealth Government in forced adoption practices, and its potential role in developing a national framework to address the consequences for mothers, their families and children who were subjected to forced adoption policies. Although our study includes participants with experiences of forced adoption, it includes perspectives from all people potentially affected by past adoption practices (adopted persons, mothers, fathers, adoptive parents, other family members) and service providers, and relates to the full range of adoption circumstances, not just experiences of force/coercion.

Although the Senate Inquiry's terms of reference were focused on the experience of forced adoption and the role of the Commonwealth in these practices, the report of the Senate Inquiry (2012) also provided a number of insights into the experience of trauma, and how those affected can best be served. The report highlighted the "ongoing nature of the trauma caused by forced adoption, and the consequent need for counselling" (p. 219). Due to the complexity of grief, a consistent theme was the need for specific counselling services by well-trained and experienced professionals. In particular, the Senate Inquiry acknowledged that it was "not aware of any research comparing the effectiveness of trauma counselling by trained professionals and the support provided by members of peer support groups" (p. 232). One of the strengths of the current study is its systematic examination of the kinds of support and professional services received by affected individuals, and the identification of those that were seen as being the most helpful.

Aim

The key focus of the study is to improve knowledge about the extent and effects of past adoption practices, and to strengthen the evidence available to governments to address the current needs of individuals affected by past adoption practices, including information, counselling, search and contact services, and other supports.

The main objectives for this study are to:

- examine experiences of past adoption practices as they relate to the current support and service needs of affected individuals;

- consider the extent to which affected individuals have sought support and services, and the types of support and services that have been sought;

- produce best estimates of the number of mothers and children currently living in Australia who were affected by past adoption practices; and

- analyse the findings and present information from the study that could be used in the development of appropriate service responses, including best practice models or practice guidelines for the delivery of supports and services for individuals affected by past adoption practices (such as "what works" to assist with the reunion process).

Method

The methodology of the study was to conduct a series of large-scale quantitative surveys and in-depth qualitative interviews with those affected by closed adoption in Australia, as well as to engage with representative bodies, service providers and relevant professionals, including psychologists, counsellors and social workers.

The study has targeted a wide group of those with past adoption experiences, including: mothers and fathers separated from a child by adoption, children who were adopted, adoptive parents, wider family members (to look at the "ripple effects"), and those servicing their current needs (counsellors, psychiatrists, psychotherapists, psychologists and other professionals).

It has incorporated a mixed-methods approach comprising online surveys and reply-paid hard copy surveys, followed by in-depth interviews and focus groups with a sub-component of the survey respondents. Results were integrated across the two data collection methods, and build on existing research and evidence about the extent and effects of past adoption experiences.

Participants

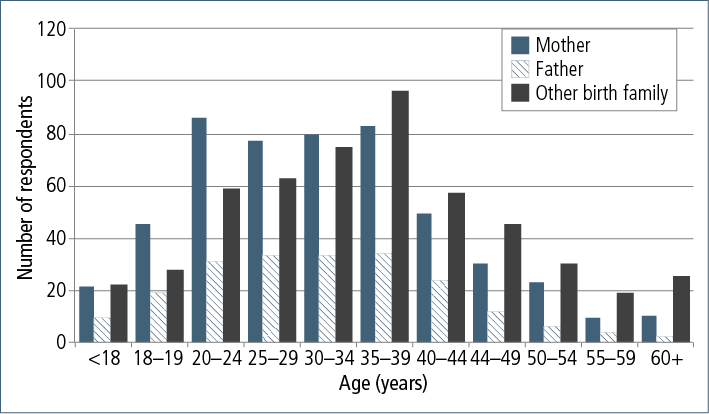

Survey respondents (n = 1,528) comprised:a

- 823 adopted individuals;

- 505 mothers;

- 94 adoptive parents;

- 94 other family members; and

- 12 fathers.

In addition, we surveyed 58 service providers about their views on the current needs and service provision models for those affected by past adoption practices.

Follow-up individual interviews and focus groups included over 300 participants, in 19 locations, across all states and territories.

Key findings

Most participants in this study were adamant about the need to provide as much information as possible about their past experiences in order for us to adequately understand their current service and support needs. This is reflected in our decision to present the findings using a narrative approach to describe the journeys undertaken by participants, thereby providing appropriate context and meaning to the study's conclusions.

Mothers

The experiences of the mothers who participated in this study would suggest that the long-term effects of past adoption practices cannot be understated. Mothers described a range of areas where practices relating to their experience of adoption continue to affect them now, including:

- the birth process;

- differential treatment from married mothers;

- experiences of abuse or negligence by hospital and/or maternity home staff;

- administration of drugs that impaired their capacity;

- lack of the ability to give or revoke consent;

- not being listened to about their preferences; and

- being made to feel unworthy or incapable of parenting, particularly from authority figures.

These experiences have left many feeling they were the victims of a systematic approach to recruiting "undeserving mothers" for the service of deserving married couples. There were very few birth mothers in the study who felt that the adoption was their choice.

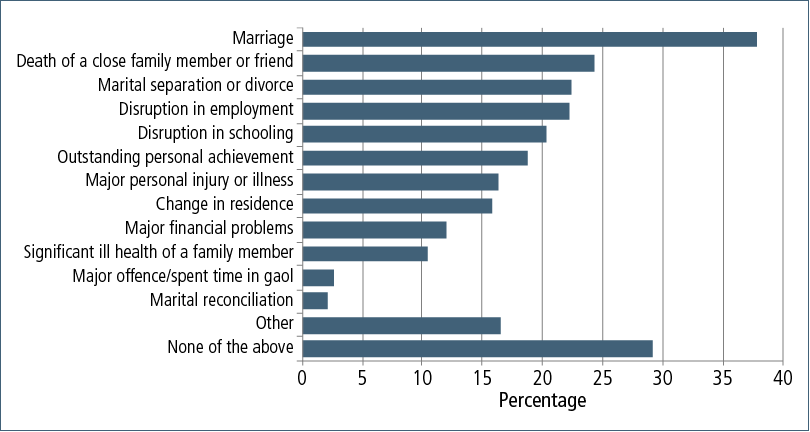

The most commonly identified contributing factors to their child's ultimate adoption were family pressure and/or lack of family support, and mothers often talked about emotions such as grief, loss, shame and secrecy surrounding their experiences.

Mental health and wellbeing measures used in the survey indicate a higher than average likelihood of these mothers suffering from a mental health disorder compared to the general population, with close to one-third of the mothers showing a likelihood of having a severe mental disorder at the time of survey completion.b Mothers rated lower quality of life satisfaction than the Australian norm, and over half had symptoms that indicate the likelihood of having post-traumatic stress disorder. These findings have significant implications for the workforce development requirements of those likely to be in contact with mothers affected by past adoptions, including primary health providers and those working in the mental health field, such as psychologists, psychiatrists and psychotherapists.

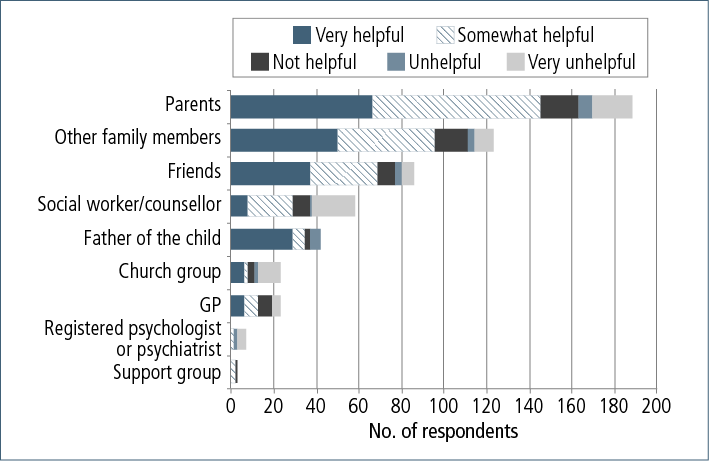

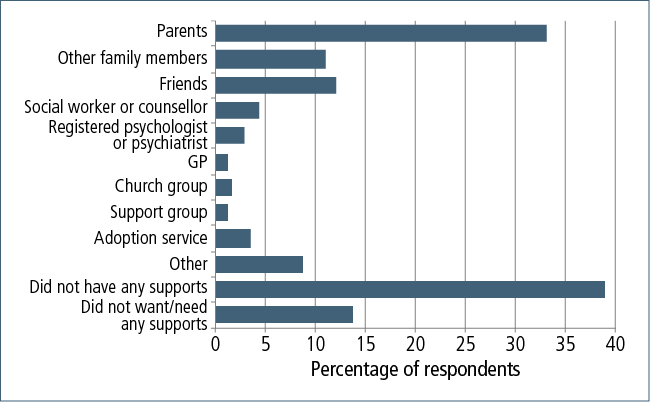

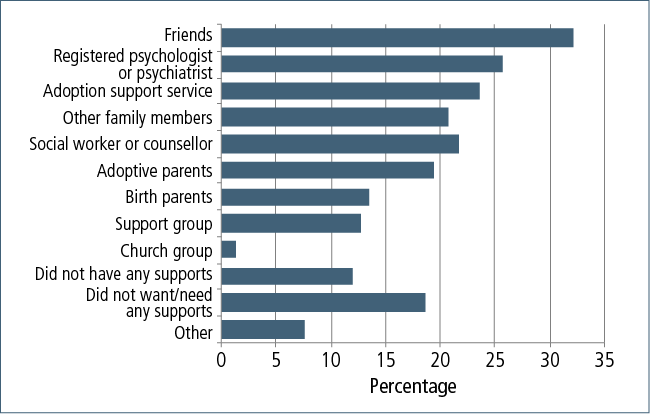

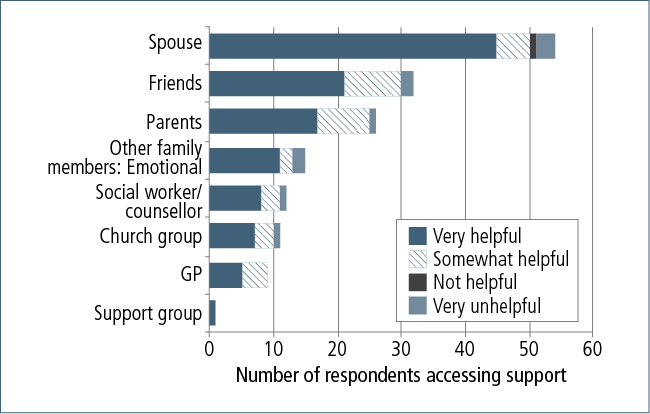

Around one-quarter of the mothers said that they had not had any supports to help them deal with the separation from their child, or with the process of search and contact. Mothers identified that the most common form of support they had received in relation to their experiences was from their friends; however, support from professionals/services was also commonly received by mothers, from psychologists or psychiatrists, support groups, social workers or counsellors, and registered search/support organisations. These supports were most commonly viewed as being helpful.

Mothers commonly identified the effective and enabling characteristics of such services as being:

- accessibility;

- affordability;

- flexibility in the modality of services provided;

- sensitivity to the particular needs of mothers separated from children by adoption; and

- staffing by trained professionals with an in-depth understanding and level of experience in trauma and other related issues commonly experienced by the mothers.

The majority of mothers (85%) had had some form of contact with their son/daughter from whom they were separated, and almost two-thirds of these respondents indicated that they had been able to establish an ongoing relationship. For some, their needs had been met simply through the connection with their son/daughter. Qualitative accounts, however, emphasised the difficulties associated with the establishment of new relationships and the need for ongoing assistance for both themselves and their son/daughter to more effectively manage this evolving and complex connection.

Mothers consistently identified six key areas that reflect their current service and support needs:

- validation of their experiences - that what happened to them happened;

- acknowledgement of their experiences through broader community and professional education and awareness;

- restitution through acknowledgement of the truth;

- access to information;

- access to services both for mental and physical health, and for search and contact; and

- a "never again" approach so that society will learn from its mistakes from past practices around closed adoption in Australia.

These themes are consistent with the findings of the Senate Inquiry.

Persons who were adopted

As the largest proportion of participants in this study, the views and experiences of persons who were adopted have provided some key understandings as to their current service and support needs. The findings indicate that the complexities of the issues identified by this respondent group require careful consideration within the context of the service and support options that are currently available. The longer term effects of adoption (both positive and negative) are significant for many adoptees in this study, reflected no more clearly than through their levels of participation in the research.

One of the most significant findings within this respondent group appears to be that, regardless of whether they had a positive or more challenging experience growing up within their adoptive family (roughly equal proportions of each participated in this study), most participants identified issues relating to problems with attachment, identity, abandonment and the parenting of their own children.

Compared to Australian population estimates, adoptees responding to our survey had lower levels of wellbeing and higher levels of psychological distress, and almost 70% of adoptee survey respondents agreed that being adopted had resulted in some level of negative effect on their health, behaviours or wellbeing while growing up. These negative effects included:

- hurt from secrecy and lies surrounding their adoption and subsequent sense of betrayal;

- identity problems;

- feelings of abandonment;

- feeling obligated to show gratitude throughout their lives;

- low levels of self-worth; and

- difficulties in forming attachments to others.

Some of these issues became more poignant when the adoptee had his/her own children, which in itself is an area for consideration in relation to the focus of current support needs.

For those study participants who were subjected to abuse and neglect by their adoptive families, the mental and physical health issues that result from such traumas may require urgent access to intensive, specialised and ongoing supportive interventions.

Seeking information about themselves and family members from whom they were separated was a strong feature in this study for adopted individuals, particularly as this process relates to the formation of identity. Over 60% of participants had had some form of contact with their mother, and 45% of those participants described a relationship that was ongoing; however, only around one-quarter of participants had had contact with their father (around half of whom said they had an ongoing relationship).

Barriers to finding information about families of origin included:

- navigation of complex systems that hold identifying information, particularly for those living in a different state to where they were born;

- costs associated with accessing information;

- inconsistent and sometimes unreliable information provided by departments/institutions;

- feelings of divided loyalties and subsequent guilt for initiating the search process; and

- contact and information vetoes having been placed by birth parents.

Further complexities arise for those who do not discover that they are adopted until late in their lives, as well as for those whose adoptions were not formalised (such as a private arrangement where the child was placed with another family without any legal processes). These individuals are often faced with having absolutely no information about themselves and where they have come from. Late-discovery adoptees may experience significant emotional damage as they find themselves contemplating a life that has been based on lies and deception, no matter how well-intentioned their adoptive families may have been in keeping the adoption secret.

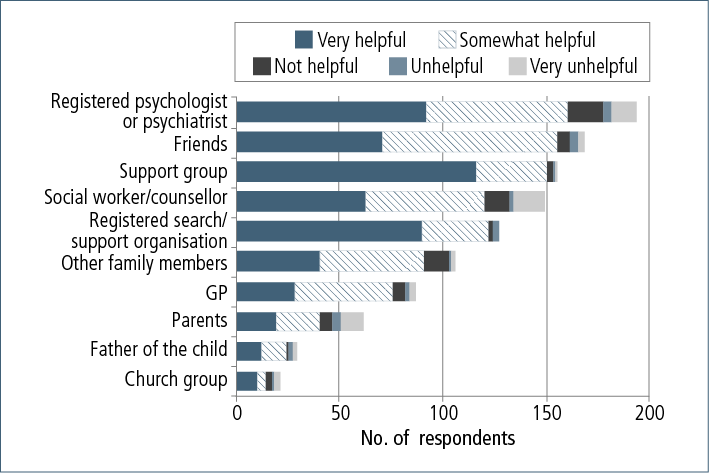

Service utilisation was common among adoptees in the study; in most instances they used psychologists or psychiatrists, adoption support services, or social workers or counsellors. Emotional support was the most frequently sought type of support by adoptees, and more than half of those who had utilised such services had found them to be helpful.

Key service needs identified by adoptees who participated in our study related to the provision of:

- free access to information - original birth certificates and medical/genetic histories (irrespective of contact and information veto status in this instance);

- search and information policies, processes and systems that are uniform across states/territories, preferably managed through a national, centralised system;

- acknowledgement and recognition of the effects of adoption as the living examples of past policies and practices;

- public awareness and education about the effects of adoption, including among broader health and welfare professionals;

- support (and financial assistance) for search and contact, such as Find and Connect services; and

- ongoing counselling and wellbeing support, which recognises that the effects of adoption can be lifelong and may be triggered at any time.

Adopted persons in the study identified the characteristics of services (including those offering search and contact as well as psychological/emotional support) that would enhance their utilisation as being:

- accessibility;

- affordability;

- ease of navigation;

- provision of ongoing (including follow-up) services;

- offering a variety of options to suit differing needs (such as a range of peer support groups and more intensive one-to-one support interventions);

- staffing by professionals with specific training and experience in working with those affected by adoption; and

- availability of mediators/case managers to facilitate the process of search, potential contact and the subsequent outcomes.

Fathers

The limited level of participation by fathers separated from a child by adoption (n = 12) in the current study is in itself, an indication of the need for further and more targeted research with this respondent group. As a particularly hard-to-reach population, specific and assisted recruitment strategies are necessary to further our knowledge and understanding of the broader effects of past adoption practices on fathers, particularly given that the research conducted to date indicates that this group already feels as though they are rarely considered in the broader discourse associated with past adoption practices in Australia (see Coles, 2009; Passmore & Coles, 2008).

Fathers who did participate in the research, however, provided substantial insight into their experiences, which are perhaps reflective of what many other fathers would have also experienced. Unfortunately, such a small number of respondents in this study does not allow us to generalise any of the findings.

These study participants told us that they were never asked or had no rights or say in the decision for their son/daughter to be adopted. However, they said that they had wanted to have a say in what happened with regard to adoption, and many wanted to keep the baby. Very few of them had support at the time of the pregnancy and birth, and very few have had support since.

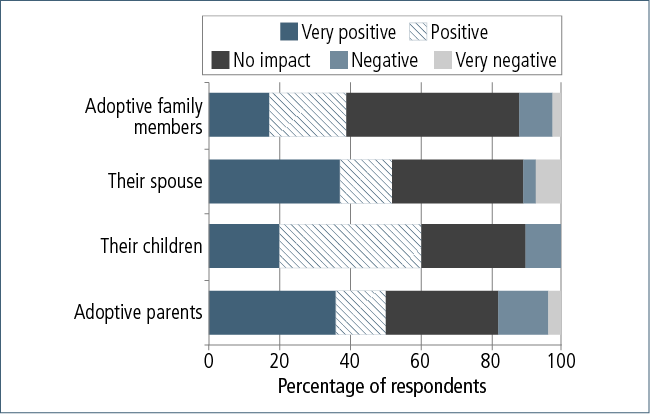

Most of these fathers had actively sought contact with their child (n = 9), and 10 had had contact (one father was contacted by their child). Of these, most had an ongoing relationship with their son/daughter, which in general appears to have had a positive effect on both themselves and their families.

An interesting and important finding within this sample is that one-third were likely to have a mental health issue, and almost all of them showed some symptoms of post-traumatic stress. This is an area that requires further investigation to establish the ongoing mental health needs of fathers separated from a child by adoption.

Fathers in this study identified their current needs as being centred on:

- having increased information and understanding within the broader community of what happened and why; that is, past adoption practices and fathers' ultimate lack of inclusion/control over any decision-making processes relating to the adoption of their child; and

- the availability of specialised support for all people who have been damaged by what has happened and, specifically, services that are targeted at identifying and encouraging utilisation by fathers who are as yet to speak of their experiences and associated impacts.

Adoptive parents

Many of the comments from the adoptive parents in the study reflect the broader society's attitudes towards adoption in the 1960s and 1970s, which "encouraged" adoption as a way of addressing infertility (Higgins, 2010). Many stated that they were giving a loving home to a child who would have otherwise been left to institutional care, that the adoption of their son or daughter addressed their need and the need of the mother to have someone take her child. In contrast to the mother's experience of the adoption, most adoptive parents were completely satisfied with the adoption process at the time.

Service utilisation was low within this sample, with many more likely to rely upon the support of their spouses and friends for any issues relating to their adoption experience. Mental health and wellbeing measures used in the study show that the adoptive parents who participated are faring well compared to other respondent groups (particularly adoptees and mothers), and these results are within general population norms. However, many of the adopted individuals (and some mothers) who participated in the study indicated that support for the adoptive parents was in fact a current area of need. The areas of support adoptees suggested ranged from acknowledging the grief suffered by adoptive parents as a consequence of their infertility, to developing better strategies for managing the complexities of their child's contact with the families of origin.

Adoptive parents had mixed views about their sons/daughters attempting to make contact with birth parents. The issue of divided loyalties, as it relates to the adoptees' search and contact process, in many ways contrasted with the views held by the adoptive parents. Some adoptive parents felt that their son/daughter's contact with birth family members had contributed to the demise of their relationship with their child, whereas others felt that it had enriched their lives through the expansion of their family unit.

There were few current service needs identified by the adoptive parents in this study. They did not consistently identify needs for themselves, but rather were focused on search and contact services for their sons/daughters, as well as assistance for them in finding out information, such as medical histories.

Other family members

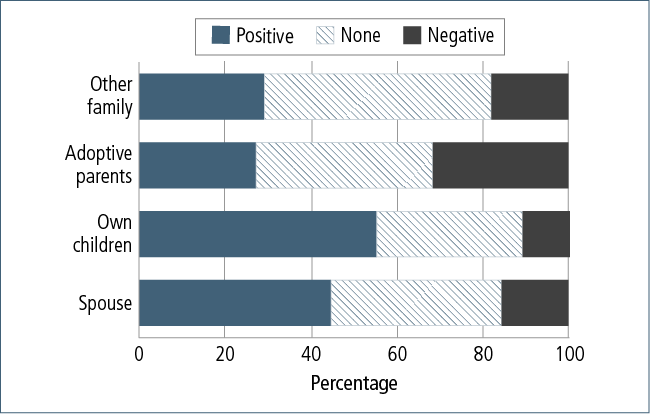

The ripple effects through families are indeed evident from the information provided by the study respondents. A diverse range of relatives completed the survey for those affected by the adoption experiences of a relative (including siblings of the persons adopted, spouses of mothers, and subsequent children of mothers). There was also a range of experiences with the search, contact and reunion with their relative and the family of origin, some of which resulted in a positive effect on relationships, while others were negative.

Although the majority of the relatives had support, most believed that there needs to be facilitated access to support (counselling and therapy) for themselves and their relatives regarding the issues arising from adoption. Other needs include assistance with contact/reconciliation with the "lost" relative, a provision of the facts regarding the adoption, and improved access to information about the family of origin (such as medical histories).

In general, other family members had been adversely affected by the adoption experience (although a few did express positive experiences). Most talked about the ways in which they would benefit from access to support to deal with issues arising from past adoption experiences, including obtaining information, making contact, having peer support, and expanding community awareness, understanding and contrition.

Service providers

The feedback from the service providers corroborated what mothers and adoptees told us about their experiences of accessing services. The predominant issue was that there were not enough services, and when they were available, the professionals were often not knowledgeable about adoption-specific issues. Furthermore, many clients were not aware of the services available, and those who were aware often found that the cost of the services made long-term involvement prohibitive.

The strongest message from the service providers was the need for support for counselling - financial support to assist people affected by past adoption experiences to afford counselling, as well as training support to assist in the development and cost of training counsellors in adoption-specific issues. One respondent suggested implementing a model similar to Find and Connect, which is a service developed to address the needs of people who have been in out-of-home care as children, whether as Forgotten Australiansc or child migrants,d and which has a special search unit for difficult cases.

Respondents supported the development of a system-wide network that can connect clients with services, and support services with other related services. Furthermore, search and reunion organisations advocated for a better relationship with government agencies to assist in the sharing of information.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A significant limitation of the study is that the data were collected from a self-selected sample as there is no identified database or other sampling frame from which to randomly invite people to participate. Therefore, we cannot say with confidence that our findings are representative of all people who have experienced closed adoption in Australia, particularly for the findings about fathers, given the very small numbers (n = 12) who participated in the study.

One of the original aims of the study was to attempt to produce the best possible estimates of the number of parents, adoptees and adoptive parents/family currently living in Australia who are affected by past adoption practices. However, the self-selected sample of study participants and lack of available sources from which to extract such information has prevented us from producing a reliable estimate. From the information that we do have from the Housing, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, we can conclude that the number of affected people is a significant proportion of the Australian population (around 200,000).

Nevertheless, there are numerous strengths to the present study that mean the data will be a reliable source of information on the experiences and current needs of Australians affected by past adoption practices - most particularly the large number of respondents (n = 1,528), representing a small, but still significant, proportion of Australians currently alive who are likely to have been affected by closed adoption that took place from the mid- to late 20th century.

Our hope is that the rich detail provided of individuals' journeys through the period of closed adoption in Australia, the issues they now face, and how services and supports could be better targeted, is reflective of the variety of perspectives that were shared with us.

Summary of key conclusions

Key needs and priority actions

Across the various respondent groups, despite the range of views and issues raised, there are some important areas where the majority of participants aligned in identifying the needs and priority actions for responding to the ways in which closed adoption has affected their lives. These included:

- acknowledgement and recognition of past adoption practices (including the role of apologies and financial resources to address current service and support needs);

- raising community awareness of and education about past adoption practices and their subsequent effects;

- specialised workforce training and development for primary health carers, mental and broader health and welfare professionals to appropriately respond to the needs of those affected;

- review of the current search and contact service systems, with a commitment to develop improved service models;

- improved access to information through the joining of state and territory databases, governed by a single statutory body;

- improved access to and assistance with costs for mental, behavioural and physical health services; and

- ensuring that lessons from past adoption practices are learned from and translated where appropriate into current child welfare policies, and that adoption-specific services are created or enhanced to respond to the consequences of past practices.

Specific service and support options

Direct services and supports

Direct services and supports relate to a continuum of care that recognises the importance of appropriate and targeted responses at all levels of engagement; from the first point of information-seeking, to the lifelong need by some people to "move in and out of" varying levels of support. The service options identified, based on the experiences and expressed needs of participants in this study, include:

- 24-hour access to advice, support, information and referral services;

- availability of peer support groups, featuring a diversity of options for delivery;

- adoption-specific support services (post-adoption support), offering a "one-stop shop" for accessing information, search, contact and ongoing support/referral to appropriate professionals;

- availability of professional one-to-one support/counselling/therapeutic interventions, delivered by psychiatrists, psychologists, psychotherapists and other professionals who have had specialised training or experience in adoption-related issues, such as trauma, relational interactions, attachment and abandonment;

- priority access to medical, psychiatric and psychological services to address the physical and psychological health consequences of their adoption experience;

- availability of professionals to support other family members; and

- availability of primary and allied health services professionals who are trained to understand the potential effects of adoption on their service users as it relates to accurate and appropriate diagnosis and referral to appropriate support interventions.

Information and resources

Information and resources identified by study respondents that would help facilitate broader public and professional awareness include:

- publications that explain the history of adoption, the common reasons for adoption and the common emotional outcomes;

- a series of short, easy-to-read and well-presented fact sheets on key aspects of the issue (such as the mothers' experiences, the adopted persons' experiences, the adoptive parents experiences, other family members' experiences, how to find information about your birth family, and so on);

- information resources for wider family members, with advice on how to best support their loved one who is affected by adoption;

- a booklet that contains stories of people affected by past adoptions - in their own words - that gives insight into a variety of experiences, and that could be distributed widely in doctors' waiting rooms and the like; and

- a comprehensive website about adoption.

Key features of good practice

Our study suggests that "good practice" should involve implementing improvements to service provision through information delivery, search and contact services, and other professional and informal counselling and supports.

- Good information services (including identifying information and access to personal records):

- are delivered by trained staff;

- are provided through websites, moderated interactive sites ("chat rooms") and/or 24-hour phone lines;

- are provided with sensitivity to the needs of those seeking it (confidentiality, discretion, language used, etc.);

- are relevant to the "stage of the journey" of individuals; and

- have a range of support levels (e.g., access to support person onsite and in follow-up).

- Good search and contact services:

- enable access to counselling and ongoing support during the search and contact journey;

- use an independent mediator to facilitate searching for information and exchanging information; and

- address expectations before contact is made and provide ongoing support afterwards.

- Good professional and informal supports:

- incorporate adoption-related supports into existing services (such as services funded by the Australian Government's Family Support Program, Medicare-funded psychological services or other state/territory-funded programs);

- provide options for both professional and peer supports; and

- address trauma, loss, grief and identity issues.

a Terminology used to describe study participants is discussed in detail in Chapter 2. For the purposes of this report, the terms "mother" and "father" refer to the biological parents except where clarity is needed to distinguish between both sets of parents. In this instance, the terms "birth" and "adoptive" parents are used; however, we acknowledge the sensitivities relating to the use of this language.

b As with all cross-sectional research, our methods do not allow us to determine whether these higher rates of mental health problems can be attributed to their adoption experience, or to other factors.

c Forgotten Australians are adults who spent a period of their childhood or youth in children's homes, orphanages and other forms of out-of-home care, up to 1989. At least 500,000 children grew up or spent long periods in this institutional care system in the 20th century, which was the standard form of out-of-home care in Australia at the time.

d Former child migrants are adults who were sent to Australia as children as part of inter-governmental child migration schemes in the period following World War II (up to the 1970s), and who were subsequently placed in homes, orphanages and other forms of out-of-home care. It is estimated that around 7,000 children were sent to Australia from the United Kingdom and Malta under these schemes, of which about 6,700 were from the United Kingdom.

1. Introduction

"Adoption" is a word that elicits mixed responses from people. The definition of adoption that was relied upon by the Australian Senate's report on the Commonwealth Contribution to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices (Senate Community Affairs References Committee, 2012; "the Senate Inquiry"; see pp. 5-6) was that of the New South Wales Law Reform Commission (1993), and is also the definition used in this report:

Adoption is a legal process by which a person becomes, in law, a child of the adopting parents and ceases to be a child of the birth parents. All the legal consequences of parenthood are transferred from the birth parents to the adoptive parents. The adopted child obtains a new birth certificate showing the adopters as the parents, and acquires rights of support and rights of inheritance from the adopting parents. The adopting parents acquire rights to guardianship and custody of the child. Normally the child takes the adopters' surname. The birth parents cease to have any legal obligations towards the child and lose their rights to custody and guardianship. Inheritance rights between the child and the birth parents also disappear. (para. 2.1)

The practices in Australia around the permanent transfer of parental legal rights and responsibilities from a child's birth parent(s) to adoptive parent(s) have varied over time. The Senate Inquiry (2012) noted in their report that "adoption as it is now understood is a peculiarly twentieth century phenomenon" (p. 3).

Not only have adoption practices in Australia undergone considerable change, so too have society's responses to pregnancies outside of marriage and single motherhood. Until a range of social, legal and economic changes in the 1970s, unwed (single) women who were pregnant were expected to "give up" their babies for adoption. The shame and silence that surrounded pregnancy out of wedlock meant that these women were seen as "unfit" mothers. The practices at the time, called "closed adoption", were seen as the solution. "Closed adoption" was where an adopted child's original birth certificate was sealed forever and an amended birth certificate was issued that established the child's new identity and relationship with their adoptive family.1 Mothers were not informed about the adoptive families, and the very fact of their adoption was usually kept secret from the children (see Swain & Howe, 1995); though changes in legislation now allow access to information if no veto from the other party was put in place.

Given the prevalence of adoption in Australia in the second half of the twentieth century - particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s - a significant proportion of the population has had some experience of or exposure to issues relating to adoption. Therefore, it is important to have an adequate evidence base for understanding the issues, and the needs of those affected. However, understanding the true extent of past practices, or its ongoing effects, is problematic. There are no accurate data on the number of Australians who have been affected (Higgins, 2010, 2011a) and there is a wide range of people who may be affected by past adoption practices, including:

- mothers;

- adopted individuals;

- fathers;

- the mothers' and fathers' families;

- subsequent partners of the mothers and fathers;

- subsequent partners and children of adopted individuals;

- siblings;

- adoptive families;2 and

- professionals, such as nursing staff and social workers, involved in the practices of the time.

The range of people involved therefore suggests the potential for wide-ranging impacts, including the possibility of the effects of past adoption practices on these individuals in turn "rippling" through to others, including other children and family members. Furthermore, the effect of past adoption practices affects the next generation - the children of adopted persons. Commentators, professional experts, researchers and parliamentary committees have all accepted that past adoption practices were problematic, had the potential to do damage, and often did.

In its report, the Senate Inquiry noted an earlier review of the available literature regarding past adoption practices that was conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS; Higgins, 2010). In that report, the conclusion about the state of the evidence base was that:

There is a wealth of material on the topic of past adoption practices, including individual historical records, analyses of historical practices, case studies, expert opinions, parliamentary inquiries, unpublished reports (e.g., university theses), as well as published empirical research studies. They include analyses of both quantitative and qualitative data, gathered through methods such as surveys or interviews.

Despite this breadth of material, there is little reliable empirical research. To have an evidence base on which to build a policy response, research is needed that is representative, and systematically analyses and draws out common themes, or makes relevant comparisons with other groups (e.g., unwed mothers who did not relinquish babies, or married mothers who gave birth at the same time, etc.). (p. 3)

Despite there being a wealth of primary material, there has been little systematic research on the experience of past adoption practices in Australia. The focus has also been on mothers' experiences of forced adoption, with less focus on fathers (where they are aware that they were responsible for a pregnancy, and that the child was adopted), adoptees, adoptive parents, and other family members.

Although Higgins (2010) concluded that there was not a reliable evidence base for understanding the extent of past practices, the number of Australians who were affected, or its long-term effects, key issues evident from the available information included:

- the wide range of people involved, and therefore the wide-ranging impacts and "ripple effects" of adoption beyond mothers and the children who were adopted;

- the role not only of grief and loss, but the usefulness of understanding past adoption practices as "trauma", and seeing the effects through a "trauma lens";

- the ways in which past adoption practices drew together society's responses to illegitimacy, infertility and impoverishment;

- anecdotal evidence of the variability in adoption practices;

- the role of choice and coercion, secrecy and silence, blame and responsibility, the views of broader society, and the attitudes and specific behaviours of organisations and individuals;

- the ongoing effects of past adoption practices, including the process of reunion between mothers and their now adult children, and the degree to which it is seen as a "success" or not; and

- the need for information, counselling and support for those affected by past adoption practices (for a detailed review of the available literature in Australia on the effects of closed adoption, see Higgins, 2010).

As past adoption practices cannot be "undone", one of the steps in the journey for parents and their now adult children separated by adoption is the choice around making contact and potentially being reunited. The existing literature in Australia on this process is mostly from case studies and (auto)biographies, showing a significant variety of pathways and responses. Given this variability of experiences and outcomes, and the absence of any systematic empirical evidence, this is an area where further research would be of particular value. Services attempting to support those affected - including professional counsellors, agencies and support groups - would all benefit from a greater understanding of typical pathways through the contact and reunion process, estimates of the number of reunions that have occurred, the perspectives of those involved, and factors that are associated with positive and negative reunion experiences.

Apart from these issues relating to information, contact and/or reunion, there are other ongoing issues for those affected by past adoption practices, including their sense of self, relationships with others, and experience of mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (Higgins, 2010, 2011a, 2011b).

Although there is a significant body of literature on the experiences of adoptees, little attention has been paid to the specific experiences of adoptees whose parent(s) experienced force or coercion during the adoption. Likewise, there has been little research that separates out experiences from the period of closed adoption from the more recent open adoption paradigm now operating in Australia (see section 2.2).

The current feelings and experiences of adoptive parents from the period of closed adoption have also not been a focus of the empirical literature. For example, there was no focus in the Senate Inquiry (2012) report on adoptive parents, or ways in which adoptive parents think and feel in response to societal shifts in attitudes and support for single parents, and changes in adoptive practices.3

Similarly, the voice of service providers has not been heard, nor their perspectives on the current needs of those affected by past experiences and their professional opinions about what works best in delivering effective services to clients.

1.1 Objectives of this study

On 4 June 2010, the Community and Disability Services Ministers' Conference (CDSMC)4 announced that Ministers had agreed to a joint national research study into "closed adoption" and its effects, to be conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The aim of the current study, commissioned by the Department of Families, Housing Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) on behalf of CDSMC - the National Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices - is to utilise and build on existing research and evidence about the extent and effects of past adoption practices in order to strengthen the evidence available to governments for addressing the current needs of individuals affected by past adoption practices.

The key focus of the study is on current needs for services and supports, and it was designed to produce evidence that can assist with improving service responses to those affected by past practices - including information, counselling, search and contact services and other supports.

In conducting the National Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices, AIFS engaged with persons directly affected by past adoption practices, as well as with representative bodies, service providers and relevant professionals.

The main objectives for this study are to:

- examine experiences of past adoption practices as they relate to the current support and service needs of affected individuals;

- consider the extent to which affected individuals have sought support and services, and the types of support and services that have been sought;

- produce best estimates of the number of mothers and children currently living in Australia who were affected by past adoption practices; and

- analyse the findings and present information from the study that could be used in the development of appropriate service responses, including best practice models or practice guidelines for the delivery of supports and services for individuals affected by past adoption practices (such as "what works" to assist with the reunion process).

Our research incorporated a mixed-methods approach comprising online surveys and reply-paid hard-copy surveys, followed by in-depth interviews and focus groups. The results were integrated from across the different elements of the study, utilising and building on existing research and evidence about the extent and effects of past adoption experiences.

The study targeted a wide group of those with past adoption experiences, including: mothers and fathers separated from a child by adoption, individuals who were adopted, adoptive parents, wider family members (to look at "ripple effects"), and those servicing their current needs (counsellors, psychologists and other professionals).

To assist with recruitment, we developed and implemented a recruitment strategy and communications plan, including a study web page with information about the study and through which the online survey was accessed.

This study complements the Senate Inquiry into the role of the Commonwealth in former forced adoptions. The Senate Community Affairs References Committee was charged with examining the role, if any, of the Commonwealth Government in forced adoption practices, and its potential role in developing a national framework to address the consequences for mothers, families and children who were subjected to forced adoption policies. It also complements the work of the History of Adoption Project at Monash University, which is focused on "explaining the historical factors driving the changing place, meaning and significance of adoption", particularly through its collection of oral histories.5

In this report, we:

- analyse information on the long-term effects of past adoption practices as they relate to current support and service needs of affected individuals, including the need for information, counselling and search and contact services;

- examine the extent to which affected individuals have previously sought support and services, and the types of services and support that were sought; and

- analyse the findings and present information from the study that could be used in the development of best-practice models or practice guidelines for the delivery of supports and services for individuals affected by past adoption practices.

1.2 Process

The study commenced with the development of a communications strategy, including the creation of a website and online method for registering interest in participating in the survey. We convened a technical advisory group, and led consultations with stakeholder advisory groups convened by FaHCSIA.

Through the technical advisory group of 10 people - comprising academic experts, representatives from key family support agencies, and representatives of FaHCSIA and the Community and Disability Services Ministers' Advisory Council (CDSMAC) (see Attachment A1 for details) - the Institute ensured that the research was of the highest possible standard for testing the conclusions about the nature of support needed for those affected by past adoption practices. The technical advisory group also provided feedback on this report. The terms of reference for this group are included in Attachment A2.

The value of obtaining input from stakeholder advisory groups representing those affected by past adoption experiences cannot be understated. Our engagement involved consultation with representatives from support groups for mothers, individual mothers, fathers, adopted individuals and adoptive family representatives. One part of this process included conducting two stakeholder advisory group teleconferences, with predominantly mothers separated from children by adoption. Further contact and input was also received from individuals both from these groups and from the wider affected community. The main purpose of this contact was to provide feedback on the proposed content areas for the surveys and assist with recruitment of people into the surveys.

Based on feedback from the technical and stakeholder advisory groups, we refined the content of the online surveys. Approval from the AIFS Human Research Ethics Committee was obtained on 8 July 2011 for both the quantitative and qualitative data collection components for this study.

With input from the technical and stakeholder advisory groups, we developed a list of agencies/individuals to be targeted by the various strategies and implemented an ongoing communication strategy to publicise the study and maximise response rates (see section 3.4 for more detail).

1.3 Terminology

A range of different terms is used in the literature to refer to both adoption practices and those affected by them. In relation to mothers, these include:

- relinquishing mothers;

- parents who relinquished a child to adoption;

- birth mothers;

- biological mothers;

- natural mothers;

- genetic parents;

- adoption of ex-nuptial children;

- mothers affected by past adoption practices;

- mothers of the stolen white generation (analogous to the Stolen Generations of Aboriginal children removed from their parents, which occurred at roughly the same time period) (Cole, 2008);

- real parents (Grafen & Lawson, 1996).

In terms of the process, many affected individuals reject the term "adoption", as their personal experience was one of force, coercion or other illegal behaviour. Terms such as "relinquishment", while occurring often in the early literature, connote a sense of agency and choice that many deny having. Some other terms that have been used in the literature include:

- losing a child to adoption (McGuire, 1998);

- reunited mother of child/ren lost to adoption (Farrar, 1998);

- separation from babies by adoption (Lindsay, 1998); and

- rapid adoption (the practice of telling a single mother her baby was stillborn, and the baby being adopted by a married couple).

It is acknowledged that some of the terms are perceived as being "value-laden", either because of their acceptance of a particular point of view (e.g., "stolen" implies illegal practices), or because their attempt at neutrality (e.g., "relinquishing mothers") potentially hides what are alleged as immoral or illegal practices. For the purposes of the current document, where possible, the terms used by the respondents are used to describe their experiences.

Similarly, there are some sensitivities around the terms used to describe the child who was adopted. These people adopted during the period of closed adoption in Australia are now well into adulthood and are themselves often parents or sometimes even grandparents. Referring to them as "children" is therefore problematic, and many prefer being called a "son/daughter", or simply an "adoptee".

Another term in the literature that is often used is "reunion", referring to the process of a parent and their adopted son or daughter making contact. However, it is important to distinguish between the process of exchanging details, communicating, or even meeting - and the longer term aim of effecting a "reunion"; therefore, it should be seen as a process from making contact through to possible reunion.

1 According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW; 2012), all states and territories now have a level of "openness" - or the option of openness - in adoption. This can involve gaining access to information or contact between birth and adoptive families. Parties to an adoption can apply for access to information that is either "identifying" or "non-identifying". In some jurisdictions, open adoption is available on request; in others, it is the standard practice for all adoptions (see AIHW, 2012, pp. 70-72).

2 In section 1.3, the issue of terminology is discussed in detail. For the purposes of this report, we try to reflect the language that participants used, as well as terms that the technical advisory group and stakeholder advisory groups identified as being preferable.

3 There was no mention of adoptive families in the motion that established the Senate Inquiry (2012, see p. 1) and, to the best of our knowledge, there is no direct reference in the report to the experiences of adoptive parents and their current needs.

4 CDSMC has since been renamed as the Council of Australian Governments Standing Council on Community, Housing and Disability Services (SCCHDS).

5 See the History of Adoption Project website at <arts.monash.edu.au/historyofadoption>.

2. Background

This chapter provides a summary of the ways in which adoption currently operates in Australia, past adoption practices, and the potential effects that adoption has on those involved. Some of the key legal and policy milestones regarding adoption and single mothers in Australia are outlined in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1 Legal and policy milestones regarding adoption and single mothers in Australia

- Legislation on adoption commenced in Western Australia in 1896, with similar legislation in other jurisdictions following (but not until the 1920s in most instances).

- Before the introduction of state/territory legislation on adoption, "baby farming"* and infanticide were not uncommon.

- Legislative changes that emerged in the 1950s and consolidated in the 1960s enshrined the concept of adoption secrecy and the ideal of having a "clean break" from the birth mother.

- State/territory councils, and eventually a national Council of the Single Mother and Her Children, were established in the early 1970s, which set out to challenge the stigma of adoption and to support single and relinquishing mothers.

- The Commonwealth Government introduced the Supporting Mother's Benefit in 1973, which contributed to a rapid decline in adoptions after a peak in 1971-72.

- The status of "illegitimacy" disappeared in the early 1970s, starting with a Status of Children Act in both Victoria and Tasmania in 1974 (in which the status was changed to "ex-nuptial").

- Abortion became allowable in most states/territory from the early 1970s (the 1969 Menhennitt judgement in Victoria and 1971 Levine judgement in NSW).

- Further legislative reforms started to overturn the blanket of secrecy surrounding adoption (up until changes in the 1980s, information on birth parents was not made available to adopted children/adults).

- Beginning with NSW (in 1976), registers were established for those wishing to make contact (both for parents and adopted children).

- In 1984, Victoria implemented legislation granting adopted persons over 18 the right to access their birth certificate (subject to mandatory counselling). Similar changes followed in other states (e.g., NSW introduced the Adoption Information Act in 1990).

- By the early 1990s, legislative changes in most states/territories ensured that consent for adoption had to come from both birth mothers and fathers.

- The majority of local adoptions (those of children born or permanently residing in Australia) are now "open".

* "Baby farming" refers to the provision of private board and lodging for babies or young children at commercial rates, a practice that has been criticised for being focused on financial gain, including cases of serious neglect and infanticide; however, it was also part of the system for protecting children who were at risk from infanticide or neglect by their family.

Source: Higgins (2011a)

2.1 Current adoption practices in Australia

There are three types of adoption currently operating in Australia:

- Intercountry adoptions are of children from other countries who are usually unknown to the adoptive parent(s). Since 1999-2000, most adoptions in Australia have been intercountry adoptions. In 2010-11, there were 215, representing 56% of all adoptions.

- Local adoptions are those of children born or permanently residing in Australia, but who generally have had no previous contact or relationship with the adoptive parents. In 2010-11, there were 45 local adoptions, representing 12% of all adoptions.

- "Known" child adoptions are of children born or permanently residing in Australia who have a pre-existing relationship with the adoptive parent(s), such as step-parents, other relatives and carers. In 2010-11, there were 124 "known" child adoptions, representing 32% of all adoptions (AIHW, 2012).

Despite the large growth in the number of Australian children in out-of-home care over the last two decades, adoption of these children is rare. This is because there is a strong push for them to be restored to - or maintain active contact with - their parents. In addition, most state/territory child protection statutory authorities have the capacity to: (a) make permanent care orders (which provide security of placement with a foster/kinship carer); and/or (b) have policies relating to the creation of permanency plans6 when there is no foreseeable likelihood of children being able to safely return to the care of their parents. Unlike adoption, these foster/kinship care arrangements do not formally extend past a child turning 18 years of age and the birth certificate is not altered.

2.2 History of adoption

Adoption rates

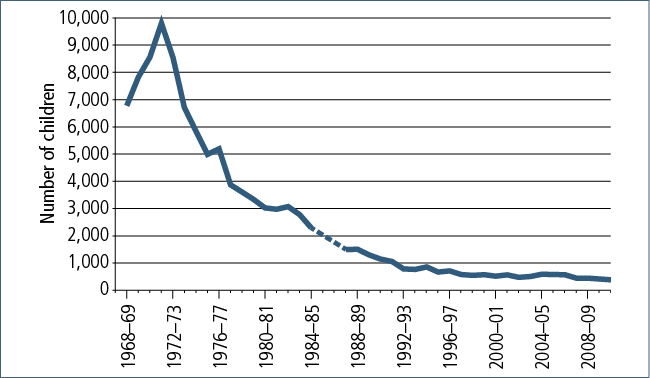

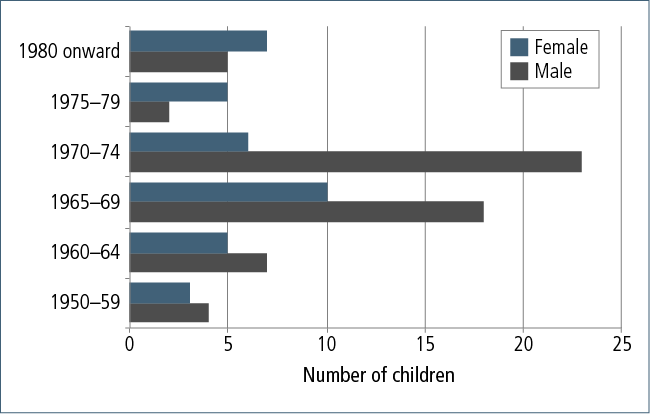

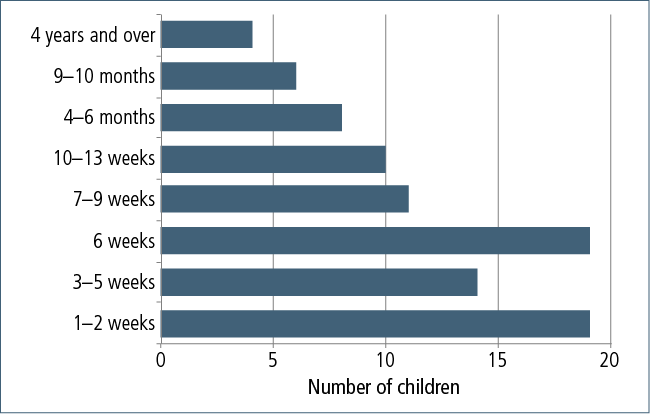

The first legislation on adoption in Australia was enacted in Western Australia in 1896, with similar legislation following in other jurisdictions, mostly from the 1920s. In the decades prior to the mid-1970s, it was common in Australia for babies of unwed mothers to be adopted. At its peak in 1971-72, there were almost 10,000 adoptions (see Figure 2.1). Since then, rates of adoption dropped significantly, and over the last two decades have remained relatively stable at around 400-600 children per year (e.g., there were 384 adoptions in 2010-11; AIHW, 2012).

Figure 2.1: Number of adoptions in Australia from 1968-69 to 2010-11

Note: National data were not collected between 1985-86 and 1986-87.

Source: AIHW (2009; 2012)

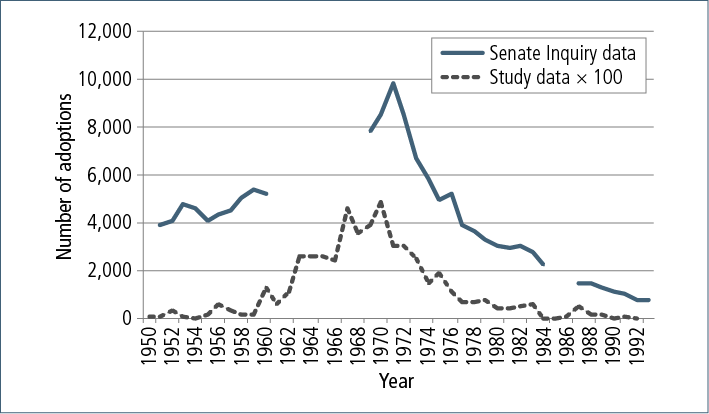

Similarly, there was a rise in adoptions from the early 1950s, with a peak in 1970-72, and declining rapidly though to the mid-1980s (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Number of adoptions in Australia from 1951-52 to 1984-85

Note: National data were not collected between 1961-62 and 1968-69

Source: Senate Community Affairs References Committee (2012)

This significant change in adoption rates coincided with a range of legislative, social and economic factors, such as:

- greater social acceptance of raising children outside registered marriage, accompanied by an increasing proportion of children being born outside marriage;7

- increased levels of support being available to lone parents (e.g., the Supporting Mother's Benefit, introduced in 1973) (see Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 1988);

- increased availability and effectiveness of birth control;8 and

- declining birth rates.

Inglis (1984) claimed that more than 250,000 Australian women had "relinquished" a baby for adoption since the late 1920s, but without describing the basis for this calculation. Nonetheless, it is a claim that has been widely cited since.

In any case, what is not known is the proportion of these adoptions that involved force, coercion, or other immoral or illegal behaviours.

Closed adoption

From the mid-20th century, adoption practice in Australia reflected the concept of secrecy and the ideal of having a "clean break" from the birth parents. Closed adoption is where an adopted child's original birth certificate is sealed and an amended birth certificate issued that establishes the child's new identity and relationship with their adoptive family. Legislative changes in the 1960s tightened these secrecy provisions, ensuring that neither party saw each other's names.

The experience of closed adoption included people being subjected to unauthorised separation from their child, which then resulted in what has been called "forced adoption". From the 1940s, adoption advocates saw it as desirable for the child to be separated from the mother as soon as possible, preferably straight after birth.9

From the 1970s, advocacy led to legislative reforms that overturned the secrecy within adoption, such as mothers receiving identifying information. However, it was not until further changes were made in the 1980s (or 1990s in some Australian jurisdictions) that information on (birth) parents was made available to adopted children/adults.

Beginning with NSW in 1976, state/territory-based registers were established for both birth parents and adopted children who wished to make contact. In 1984, Victoria implemented legislation granting adopted persons over the age of 18 the right to access their birth certificate (subject to mandatory counselling). Similar changes followed in other states/territories (e.g., NSW introduced the Adoption Information Act in 1990). Support groups such as Jigsaw, also established their own registers.

Contact/reunion services are now part of the ways in which governments and agencies are trying to address the negative effects of past adoption practices and separation on (birth) parents and children.

Open adoption

The practice of closed adoption changed gradually across each of the states and territories in Australia from the late 1970s through the 1980s and 1990s.

With the implementation of legislative changes, adoption practices shifted away from secrecy. Now, the vast majority (84% in 2010-11) of local adoptions (but not intercountry adoptions) are "open", where the identities of birth parent(s) can be known to adoptees and adoptive families and there are access arrangements. However, the birth certificate is still changed to record the names of the adoptive parents. Among local adoptions, only 16% of birth parents in 2010-11 signed a consent involving no contact or exchange of information with the adoptive family (AIHW, 2012).

Improvements in adoption practices include:

- more accountable processes for obtaining consent from (birth) parents;

- a requirement for consent to be provided by both (birth) parents (or the need for a parent's consent to be dispensed with by a court for a child's adoption to proceed); and

- higher quality assessments and benchmarks for assessing the suitability of prospective adopters.

2.3 Effects of past adoption experiences

There is limited research available in Australia on the issue of adoption practices during and following the period of closed adoption in Australia.

There was a range of people involved, and therefore the impacts and "ripple effects" of adoption reach beyond mothers and the children who were adopted, to include fathers, spouses and other family members. The available information highlights a number of important issues, many of which relate to the experience of trauma.

One issue of particular importance is the trauma of the separation of mother and child, and the resulting experience of grief and loss. Mothers - particularly those who have not had any contact - continue to be traumatised by the thought that their child grew up thinking that they were not wanted. For example, one adoptee, after meeting her mother late in life, said of her mother: "There has hardly been a day in her life that she hasn't wondered where I was or had (I) ever survived" (cited in Swain & Swain, 1992, p. 47). In the words of one mother: "It wasn't the children who were not wanted; mothers weren't wanted because they were unmarried" (cited in Higgins, 2010, p. 13, emphasis added).

As noted by Connor and Higgins (2008), many people who experience potentially overwhelming or horrific life events appear to adapt and survive without developing a psychiatric disorder or other disability. But despite this capacity that humans have, "traumatic experiences" can so profoundly affect people that "the memory of one particular event comes to taint all other experiences" (van der Kolk & McFarlane, 1996, p. 4).

As a diagnostic category, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) "created an organized framework for understanding how people's biology, conceptions of the world, and personalities are shaped by experience" (van der Kolk & McFarlane, 1996, p. 4). PTSD was used as a way of recognising the effects of trauma on the veterans of the Vietnam War, but there is growing recognition that similar stress reactions can be seen in response to other traumatic experiences, including childhood sexual abuse and adult rape.

There are similar parallels in relation to some people's experience of past adoption practices. Much of the research and case studies have focused on the issues of grief and loss experienced by these mothers, but their experiences may be better understood through this lens of "trauma".10 For example, Higgins (2010) noted that issues relating to consent and coercion (including illegal and/or discriminatory actions) point to some of the reasons why trauma may be evident. These issues include:

- administration of high levels of drugs to the mother in the perinatal period (including pain relief medication, sedatives and a hormone that suppresses lactation) that may have affected their capacity to consent;

- not allowing the mother to see the baby (such as active shielding with a sheet or other physical barrier during birth, or removing the baby or the mother from the ward immediately after birth);

- withholding information about the baby (e.g., gender, health information, or even whether the baby was a live birth);

- lying that the baby had died;

- not allowing the mother to hold or feed the baby;

- discouraging the mother from naming the baby;

- discouraging the mother from naming the father;

- bullying behaviour by consent-takers (seen as the "bastions of morality" who are protecting "good families");

- failing to advise the mother of her right to rescind the decision to relinquish, and the effective procedures to do so;

- failing to correctly obtain consent from the mother (e.g., the mother being too young to give consent; interactions with other issues raised above that prevent informed consent; consent being given while under the influence of drugs; mother not being informed of her rights, etc.);

- treating the mothers differently from married women (e.g., social workers and medical/nursing staff making assumptions that all unwed, pregnant mothers' babies would be adopted);

- being abandoned by their own mothers/families;

- the closed nature of past adoption practices (secrecy, and the "clean break" theory);

- the assumption of a married couple's entitlement to a child (adoption was a mechanism for dealing with infertility), with the joint "problem" of illegitimacy and infertility); and

- conducting experiments on newborn babies with drugs, with the children dying or being adopted without any follow-up of these experiments.

The grief and trauma is seen as "unresolvable", due to the silence surrounding closed adoption that prevents the mother from being able to mourn her loss (Goodwach, 2001; Rickarby, 1998). For mothers, the ongoing silence means knowing that their child is out there, wondering how they are, and knowing that there is a possibility of reunion - not the "severed bond" as promised by the clean break theory that shrouded the event in silence (Iwanek, 1997).

In describing the grief and trauma, many authors have drawn on related bodies of research, using infant-mother attachment research to support their contention that separation causes emotional damage to both mother and child (e.g., Cole, 2009). It is somewhat ironic that earlier research in this same field (e.g., Bowlby, 1969) was used to justify the practices of the time (i.e., not allowing the child to bond with the birth mother so as to provide a "clean break" that encourages bonding with the new adoptive parents).

As past adoption practices cannot be "undone", one of the steps in the journey for both parents and adoptees is that of making contact, and potentially being reunited. Given the variability in responses provided in the case study literature, and the absence of any systematic empirical evidence, this is an area where further research would be of particular value. Services attempting to support those affected - including professional counsellors, agencies and support groups - would all benefit from a greater understanding of typical pathways through the reunion process, estimates of the number of reunions that have occurred, the perspectives of those involved, and factors that are associated with positive and negative reunion experiences, and longer term outcomes.

Apart from these issues relating to contact and reunion, there are other ongoing issues for those affected by past adoption practices - particularly for mothers who experienced forced adoption - including problems with:

- personal identity (the concept of "motherhood" and self-identity as a good mother; the concept of family, identity and "belonging");

- relationships with others, including husbands/partners, subsequent children;

- connectedness with others (problematic attachments); and

- ongoing anxiety, depression and trauma (Higgins, 2011a).

The needs identified by writers in this field are consistent with the broader theoretical and empirical literature on other forms of trauma, such as the field of child abuse and neglect or adult sexual assault (Connor & Higgins, 2008; van der Kolk & McFarlane, 1996). As with other groups who have experienced pain and trauma, having society recognise what has occurred (i.e., naming it, and understanding how it occurred and its effects) is an important element in coping with and adjusting to the deep hurt they have experienced (Higgins, 2011a).

There is anecdotal evidence of the variability in adoption practices, ranging from women feeling that they were supported in making an informed decision, to reports of unjust, cruel and unlawful behaviours towards unmarried women during their pregnancy and birth experience.

Past adoption practices continue to affect the daily lives of many people, including the process of making contact between the mothers and fathers and adoptees (their now adult children), and the degree to which contact is seen as a "success" or not, and whether it leads to a long-term reunion.

From these identified issues, it is evident that there is a need for better information, counselling and support for those affected by past adoption practices. Additionally, more research is needed about the current views of fathers (whether they were - or are now - aware that they fathered a child who was adopted), adoptive families and their experiences of closed adoption, as well as the experiences of adoptees (including their perspectives on search and contact services, and their experiences of attempting to find out information and/or make contact).11

In the current study, we aim to address all these aspects, examining the degree to which a wide-ranging sample of Australians affected by past closed adoption practices have experienced different aspects, how this has affected them, and their current service needs. Although we attempt to provide detailed insight into all the specific categories of study participants, the weight of focus has been dependent on the levels of participation within each respondent group.

2.4 Senate Inquiry

The Senate Community Affairs References Committee (2012) concluded that having a range of psychological and psychiatric services was vital to addressing the needs of those affected by former forced adoption practices:

It is clear that there is a real need to make counselling and support services available to all the parties affected by adoption. These services can provide opportunities for people to talk about their experiences to explore inner pain and find a capacity for inner healing, which may help improve their quality of life. (p. 222)

Although the Senate Inquiry's (2012) terms of reference were focused on the experience of forced adoption, and examining the role of the Commonwealth, the report provides a number of insights into the experience of trauma, and how those affected can best be served. The report highlighted the "ongoing nature of the trauma caused by forced adoption, and the consequent need for counselling" (p. 219). Due to the complexity of the grief, a consistent theme was the need for specific counselling services by well-trained and experienced professionals.

The committee also noted the positive benefits of peer support:

Peer support groups play a role in assisting with post adoption support. Some members find validation and acceptance in the company of others with a similar experience, and benefit from "healing" relationships forged within these groups. (p. 231)

Although people who have had a common experience - such as parents and children separated through adoption - can benefit from peer support, there are some serious limitations. Consultations with a range of stakeholders as part of the current study would suggest that there are limits to the ability of peer support groups to adequately address all of the needs of people affected by adoption, with many articulating dissatisfaction with their experience of such groups. The Senate Inquiry (2012) report, for example, provided evidence from one submission that the unresolved trauma from forced adoption can be the very factor that limits the ability of mixed-group peer support processes to be effective:

Many adoptees have left groups because mothers have become frustrated and angry with them, which I believe is the result of the mother's inability to cope with their own unresolved issues of guilt and shame plus fears of possible abuses to their own child. (Ms Kerri Saint, Chair, White Australian Stolen Heritage) (p. 221)

In particular, the Senate Inquiry (2012) acknowledged that it was "not aware of any research comparing the effectiveness of trauma counselling by trained professionals and the support provided by members of peer support groups" (p. 232). One of the benefits of the AIFS study is its systematic examination of all kinds of support and professional services received, and which ones were most helpful.

The Senate Inquiry (2012) identified the role that counselling and peer support groups can provide in assisting with:

- the healing process;

- addressing specific mental health issues; and

- reconnecting with family members, which requires sensitivity, as well as specific knowledge of adoption processes and the experience of attempting to reconnect.

In its report, the Senate Inquiry (2012) emphasised the importance of services being affordable and accessible. It also identified the need for specialist training services for mental health care workers to meet the needs of people affected by past adoption experiences. The committee noted that "counselling to people affected by former forced adoption practices is a niche skill that cannot be developed without adequate exposure or training" (p. 226). Although such work could be carried out by a variety of mental health and social services, the Inquiry also acknowledged that there may be sensitivities among mothers over the role that social services, particularly social welfare agencies and/or religious organisations, had in historic practices.

6 "Permanency planning" refers to making decisions about alternative long-term foster/kinship care placements for children in out-of-home care as early as possible, to avoid the negative consequences of continuing to have failed attempts to restore children with birth parents.