Social polarisation and housing careers

Exploring the interrelationship of labour and housing markets in Australia

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

March 1998

Download Research report

Overview

Since the turn of the twentieth century, the institutional design of the ‘wage earners welfare state’ in Australia has included broad access to, and state subsidies for, home ownership (Castles 1997). Private saving for home ownership over the life course led to low housing costs in retirement and an increased likelihood of avoiding poverty (Henderson et al. 1970). Reduced poverty in retirement and the broad social base to home ownership in Australia have, overall, meant greater economic equality (Whiteford and Kennedy 1995). Thus, home ownership has ameliorated inequalities arising from the labour market. Through the 1980s and 1990s, however, significant social and demographic changes have prompted debate about an emerging social polarisation (Saunders 1994). This paper draws upon data, from a 1996 survey of a national random sample of 25–70 year olds, to examine access to home ownership in the context of changing labour market opportunities. By exploring the interrelationship of labour and housing markets, the paper investigates whether home ownership in Australia continues to play a role in social redistribution.

Introduction

Whereas the Great American Dream is of rags-to-riches millionaires, the Great Australian Dream, somewhat more modestly, is of owning a detached house on a fenced block of land. Home ownership(1) as a key cultural icon in Australia is well understood (Hayward 1986; Kemeny 1981, 1983; Winter 1994). Entry to home ownership has been the defining moment in the housing careers of nearly 70 per cent of households at any one point in time since the 1960s (Bourassa, Greig and Troy 1995:83). Nearly 90 per cent of households become home owners at some stage of their lives (Neutze and Kendig 1991:8).

Yet, more recently it has been proposed that the home ownership rate could be falling. Chris Maher (The Sunday Age, 7 April 1996: Property 2) stated, 'The greater number of households moving out of rather than into home ownership challenges a long tradition of households achieving home ownership at a relatively young age after a period of renting, and then remaining owners for life'.

If fewer households are gaining access to home ownership, this would signal a watershed in the lives of many Australian households and, indeed, in the 'Australian way of life'. Entry to home ownership has been the trigger for many couples to commence having children. As Richards suggests, it's almost as though renting is a contraceptive (1990:130-131). As families move through life, home ownership has been seen as a key way of providing a secure and stable home environment. At the end of the life cycle, home ownership has been a way families can leave a substantial inheritance to their children (Badcock 1995).

Moreover, it has been argued that home ownership is a social institution that narrows economic inequalities arising from the job market's uneven distribution of rewards (Stretton 1987). Home ownership is said to raise the living standard of those who would otherwise be worse off. In one important way, this happens through a horizontal redistribution of income from working years to retirement years. The diversion of income, during working years, to purchasing an asset that appreciates in value reduces housing costs in retirement, and establishes a store of wealth that can be drawn on.

Mitchell (1995) has calculated that the owner occupation rate among household heads aged over 55 is 76 per cent in Australia. The value of this owner occupation to low income households is estimated to be equivalent to 20 per cent of cash disposable income in the lowest two income deciles (Whiteford and Kennedy 1995:84). A further way home ownership may redistribute the patterns of inequality arising from the labour market is through access to differential rates of capital gain. Debate has centred on whether working class home owners could enjoy higher rates of capital gain from home ownership than middle class home owners due to the spatially uneven way in which the housing market can perform (see discussion of the housing classes debate below). Thus, it is possible that home ownership can shape the degree of equality between individuals at any one point in time, and across the life course.

However, a falling home ownership rate would mean fewer households could gain access to this redistributive mechanism. This paper, therefore, examines who gains access to home ownership in contemporary Australia and who does not. The increasing evidence of income polarisation in Australia (Borland 1992; Gregory 1993; Saunders 1994) provides an important clue as to which social groups are most likely to be disadvantaged. With an increasing number of high income households clustered at the top end of the income distribution, and an increasing number of low income households clustered at the bottom end, the shape of the social structure is said to be shifting from an egg to an hourglass (Pahl 1988). If this polarised income structure were reflected in the housing market, we would find a clustering of high income households in the sought after (but possibly shrinking) home ownership sector, and a clustering of low income households in the less desirable rental tenures. Such a pattern is described as socio-tenurial polarisation(2) (Hamnett 1984; Robinson and O'Sullivan 1983; Somerville 1986) where different housing tenures reflect and reinforce inequalities arising out of the labour market.

Despite the apparent 'economic rationality' of housing circumstances reflecting labour market positions, such outcomes would be a change from the past in Australia where low-income earners used public and private renting as stepping stones to home ownership. The non-preferred and less advantaged rental tenures were not regarded as permanent housing options and, therefore, did not act as an impermeable barrier of social segregation. State regulation of interest rates, generous terms of house purchase for public tenants, and assistance programs such as the First Home Owners Scheme, combined to ease access to home ownership. This provided a broad social base to home ownership and, thus, the means for the housing market to ameliorate some of the inequalities arising from the labour market.

Does home ownership continue to play this role despite increasing income polarisation? Or will those who do badly out of the labour market be unable to gain access to the preferred positions in the housing market? This paper addresses these questions. It investigates the extent of socio-tenurial polarisation in Australia; that is, the extent to which the social distribution of housing tenures, and their associated advantages and disadvantages, accord with the patterns of inequality arising from the labour market.

Indicators of housing outcomes other than tenure (for example, dwelling quality), could also be used to investigate the link between labour market position and housing market outcomes. Similarly, social processes other than the labour market (for example, family inheritance), can impact upon housing outcomes. While each of these is worthy of investigation, they are not the concern of this paper. Here, the analysis focuses only upon labour market position and housing tenure outcomes.

In answering the questions stated above, the paper has four aims. First, to extend empirical investigation of socio-tenurial polarisation in an Australian context. Second, to use the findings from that empirical investigation to inform theoretical debate about the interrelationship of labour and housing markets. Third, to bring contemporary information on changes in the nature of housing consumption to bear on housing policy debates; the outcomes of which are, in fact, a part of the reshaping of housing consumption. Fourth, to continue to connect housing research that is policy relevant to broader debates in social theory from an Australian perspective.

Section one of the paper details how, historically, home ownership has been a social institution of considerable importance in Australia. Section two examines how the interrelationship of housing and labour markets has been conceptualised and understood in social scientific debates. It examines the housing classes debate and the globalisation and social polarisation thesis. Section three draws together recent evidence of the changing nature of housing consumption and, in particular, its backdrop of shifting priorities in Australian housing policy. Section four explores the changing interrelationship of labour and housing markets in Australia by analysing cross-sectional and retrospective housing careers data from the Australian Life Course Survey. Section five draws together the argument and evidence in relation to the four key aims stated above.

The Great Australian Dream

The icon status and social significance of home ownership in Australia is multi faceted and comprises economic, political and cultural dimensions (Winter 1994). Home ownership has an economic cachet due to the potential capital gains that can occur through house price inflation (Burbidge 1997). The nation's homes are also its second (to land) most valuable asset at $437 billion (The Age, 27 March 1997:A5).

The political cachet of home ownership rests with the State's guarantee of private property rights. Property rights differentiate the lives of home owners from renters who endure very limited private property rights. Home owners, for example, enjoy rights of control and security over the dwelling far beyond those of renters (Winter 1994:35-36). These rights, and the defence thereof, provide the basis for increased levels of local political activism (Saunders 1979; Cox 1989; Davis 1990; De Leon 1992; Winter 1990). Political attitudes of a conservative nature and an allegiance to conservative parties in voting behaviour have also been linked to home ownership (Dunleavy 1979; McAllister 1984).

Home ownership also has cultural cachet in that being a home owner conveys status upon its incumbents. Perin (1977) argues the social standing of home owners derives from being able to raise credit finance from a respected social institution such as a bank. In today's deregulated financial regimes this seems a little quaint, but home owners are able to use their homes as a frame for, and as a container of, the material trappings of status (Winter 1994).

Combined, these economic, political and cultural aspects of home ownership make it a central plank in Australian society, the strength of which has been witnessed most recently in the public furore over the Government's attempt to introduce accommodation bonds for entry to nursing homes. As Ross Gittins commented in The Age (12 November 1997:A19), 'The central attack on the alleged unfairness of the nursing home changes was that they might require some old people to do the unthinkable: sell the family home. Once the opponents of the changes succeeded in linking them to the sale of the family home in the minds of the wider public, the Government was dead meat'.

Why home ownership should have come to play such a central role in Australian society is, in part, explained by its position as a cornerstone of the welfare state. In identifying the institutional design elements of the Australian welfare state, Castles (1997:33-34) points to the key role that home ownership plays: 'it is impossible to understand the adequacy of Australian income support provision...without some consideration of the role of home ownership....In Australia, where the prevailing social policy strategy has involved the modification of the primary income distribution via wage control, but state welfare expenditure is relatively low, horizontal redistribution becomes primarily a responsibility of the individual rather than the State. Individuals must save enough from their current wages to meet future eventualities, by far the most significant of which is the need for adequate income support in old age. Under these circumstances, therefore, home ownership and occupational welfare become the major guarantees of horizontal distribution for most families'.

The Australian emphasis on payment of a 'living wage' carried with it the responsibility to save to provide for oneself in old age. The age pension has always been set at a modest rate and claimants have been income and asset tested. So the key way Australians have managed to save for retirement is through purchasing owner occupied housing. The process of home purchase enables forced savings to accumulate as the asset value of the house transfers to the owner occupier through mortgage repayments. Typically, at retirement, the house is fully owned by the occupier; thus, minimising housing costs and the amount of income support needed in retirement. This more individualistic and private saving for retirement through home ownership contrasts with the collective saving for social security provision that typifies many European welfare states (Castles 1985).

The recent introduction of compulsory superannuation has added a further dimension to the retirement savings environment in Australia. The extent to which this will replace home ownership as an effective means of retirement saving is unknown. Among those who have direct interests in the housing industry (for example the Real Estate Institute of Australia), there is considerable concern that the need to make compulsory superannuation payments is harming the savings capacity of young households and compromising their ability to enter home ownership (Real Estate Institute of Australia 1997).

With the Australian welfare state structured as it is, access to home ownership becomes crucial. If fewer households are able to enter home ownership, fewer households will be able to redistribute their income through to their retirement years. In this scenario, long-term horizontal redistribution (the level of equality for individuals across the life cycle), would be negatively affected. In turn, this will impact upon vertical distribution (the level of equality between individuals at any one point in time), as a larger group of older people are rendered poorer by not having access to the economic benefits of home ownership.

This section has spelt out some of the advantages of home ownership that have set it apart as a preferred tenure form in Australia. These advantages are the bases of difference and inequality among housing consumers. Whether these inequalities ameliorate or exacerbate the inequalities arising from the world of work is a point of continuing debate.

Labour markets, housing markets and inequality

This section considers how social scientists have sought to understand the inter relationship between the housing and labour markets. It also provides a basis for conceptualising the empirical links between the two markets throughout the paper.

The housing classes debate

Sociological analysis of the role of the housing market in social inequality began with Rex and Moore's (1967) pioneering work in the UK. It highlighted the scarcity of key urban resources, such as desired housing, and the inevitable competition for such resources flowing from this. Housing tenure thus emerged as one aspect of a housing hierarchy that urban dwellers were competing for, with home ownership at the top and lodging houses at the bottom. By relating housing to an individual's life chances, Rex and Moore linked urban sociology with the mainstream sociological concerns of sources of inequality and class conflict.

Rex and Moore's work launched the housing classes debate, which many commentators would say is still unresolved despite a 30-year history. The debate focuses on the extent of inequality between individuals at a point in time (referred to above as the vertical distribution).

The Weberian school (Saunders 1978, 1984, 1990; Pratt 1982, 1986) has maintained that the housing market generates inequalities and social groups that cross-cut those of the labour market. In this scenario, the working class labourer enters home ownership, receives substantial capital gains and ends up with wealth equivalent to that of middle class office worker who, because of the vagaries of the housing market, has not received the same magnitude of capital gain. The Marxist school (Gray 1982; Harloe 1984; Edel 1982; Thorns 1981) prefers to conceptualise housing market inequalities as derivative of those in the labour market - while it's possible for the working class labourer to increase their wealth through home ownership, the middle class office worker will reap larger capital gains because they are able to buy into a 'better' slice of the housing market.

From these entrenched positions, determined largely a priori by theoretical reasoning, the terms of the debate broadened to examine the ways production based inequalities (for example, the job market) interrelated (or not) with consumption-based inequalities (for example, the housing market). In the context of a welfare state crisis (Offe 1984), Saunders (1982:1-2) proposed that '...social and economic divisions arising out of ownership of key means of consumption such as housing are now coming to represent a new major fault line in British society, that reprivatisation of welfare provisions is intensifying this cleavage to the point where sectoral alignments in regard to consumption may come to outweigh class alignments in respect of production, and that housing tenure remains the most important single aspect of such alignment because of the accumulative potential of house ownership and the significance of private housing as an expression of personal identity and as a source of ontological security'.

Theoretical contributions to this debate from Australia, including the quintessential Weberian-Marxist divide can be found in the work of Winter (1994) and Berry (1986). A greater volume of Australian work has been of an empirical nature. It has investigated the extent of capital gains available through the housing market, and the social, spatial and temporal variability in these gains (Badcock 1989, 1992ab, 1994; King 1987; Burbidge 1997). With accessible property value databases available in Australia, this considerable body of work has established that home owners enjoy significant economic advantages relative to renters. These advantages stem from the availability of capital gains, the favourable tax treatment of capital gains and imputed rent, mortgage repayments that get devalued by inflation, and financial assistance to first home owners.

The second key area of analysis has explored the extent to which the housing market financially rewards some home owners but not others. The key concern has been to ascertain whether those receiving the most in terms of capital gains are those who also benefit most from the labour market. That is, does the housing market reproduce or cross-cut inequalities arising from the labour market?

The answer to this question has 'to-ed' and 'fro-ed' as more and more sophisticated analyses have emerged. Badcock (1994: abstract 546) concludes '...returns to investment on (a) particular dwelling are much more closely related to location and synchronicity with the property cycle than to the class position occupied at the time by the household. However, when the cumulative experience of households during the course of the housing 'career' is examined, a much stronger relationship emerges between labour histories and housing mobility and wealth'.

If Badcock is right, the contemporary process of income polarisation in Australia will, in the long term, result in a polarised housing market which will, in turn, reinforce the polarisation emerging from the labour market.

Globalisation and socio-tenurial polarisation

The flagging theoretical discourse, a paucity of empirical material and the British housing market crash of the early 1990s combined to stymie the housing classes debate. Recently, however, it is possible to see signs of it reemerging although in a different guise. Hamnett (1994) 'Social polarisation in global cities...' and Murie and Musterd (1996) 'Social segregation, housing tenure and social change...', refocus our attention on housing market and labour market inequalities by pointing to the polarised income and occupational structures associated with processes of globalisation.(3)

As Hamnett (1991:193) states, 'The general thesis is, therefore, that changes in the spatial division of labour are linked to changes in the urban hierarchy, and that in the global financial cities at the top of the hierarchy, there is a sharp polarisation in occupational and income composition which is linked to a polarisation in the housing market and social segregation, but that the precise forms of these changes are locally contingent'.

This work arises from a concern with the urban implications of global economic restructuring. Sassen's (1991) thesis of the rise of global cities suggests a degree of convergence among those cities playing a key role in the new international division of labour. London, New York, Tokyo, '...because of their particular industrial structure which is dominated by financial and business services...rather than by manufacturing...are said to be characterised by a growing : 'polarisation' in their occupational and income structures' (Hamnett 1994:401). The implication of this for the housing market is that 'This polarisation is linked to changes in housing demand leading to a gentrification of parts of the inner city and to a concentration of the less skilled in the less desirable parts of the housing market. Thus, occupational polarisation is accompanied by growing social, tenurial and ethnic segregation' (Hamnett 1994:401).

In Britain this process of tenurial segregation has manifest itself as a loss of social mix, and an increasing concentration of the poorest sections of the population in the social rented sector. It is referred to as socio-tenurial polarisation or the residualisation of council housing (Murie and Musterd 1996:496).

As more and more data about the widespread extent of social polarisation have become available, the analytical focus has moved beyond the confines of global cities to reveal national differences in the extent of social polarisation. Silver (1993), Hamnett (1996) and Murie and Musterd (1996) have pointed to the importance of national differences in key institutions such as the welfare state, the housing market and housing policy in differentiating the impact of global economic change. On this basis, Murie and Musterd (1996:495) argue that 'Socio-tenurial polarisation and social segregation are not as marked in the Netherlands as in Britain and are not changing as fast'. They point to the crucial role of the organisation of the housing system and the size and operation of the social rented sector in the Netherlands as key aspects that have limited the links between poverty and housing market position, be it measured by tenure, type or location (Murie and Musterd 1996: 509-510).

This developing critique of the globalisation thesis, emphasising the integrity of national institutional processes in the face of global pressures for change, is a line of theoretical inquiry that has characterised Australian urban and regional research for the past 20 years. Berry and Rees (1994:550) point out that the theoretical significance of the national level was, for a time, striking to those engaged with international convergences associated with processes of globalisation. If North American and British authors failed to address the national specificity of processes of urban and regional change, 'In contrast, urban and regional research in Australia has consistently given due analytical weight to the specificities which arise out of the country's colonial legacy and its consequently dependent location within the international economy, historically highly focused on the export of primary products and with a relatively underdeveloped manufacturing sector' (Berry and Rees 1994:550).

Thus, it is within the general tradition of Australian urban and regional research that this paper explores the significance of the particularities of the Australian housing market and household tenure structure to understand the interrelationship of contemporary labour and housing market inequalities.

The extent of socio-spatial inequality in Australia, rather than socio-tenurial polarisation, has been documented by examining the distribution in urban space of particular social groups. Various authors (Baum and Hassan 1992; Stilwell 1980, 1989; Forster 1986, 1990; Fagan 1986; Tait and Gibson 1987; O'Connor and Stimson 1994; Forrest 1995; Burnley and Forrest 1995; Gregory and Hunter 1995) have found, though not unanimously (Houghton 1987a), an increase in socio-spatial inequality through the 1970s and 1980s. This is said to constitute increasing concentrations of the unemployed, low income households and recent migrants into the poorer areas of Australian cities, typically in the outer-suburbs. 'There is a significant increase in the geographic polarisation of household income across Australia. The poor are increasingly living together in one set of neighbourhoods and the rich in another set. The economic gap is widening' (Gregory and Hunter 1995:4). However, as Murphy and Watson (1994:585) point out, the Australian experience differs from that of US cities as the socio spatial differences do not amount to a qualitative re-definition of urban space.

Baum's (1997:1899) recent paper also usefully links Australian evidence of social polarisation to the global cities debate. Examining 1991 Census data for Sydney, Baum concludes: '...an occupational structure has emerged which is characterised by dynamic growth in certain occupations and decline in others. These changes are commensurate with those occurring in other global cities. It has been suggested that, at face value, these changes could be linked to changes in income polarisation, and therefore provide at least partial support for the global city - social polarisation thesis.

It would seem clear that processes of social polarisation are under way in Australia. However, Australian evidence of links between income and occupational polarisation and the housing market have, as yet, not come to light. The widening economic gap between rich and poor has not been related to housing consumption processes to ascertain the extent of socio-tenurial polarisation in Australia.

Housing policy and tenure restructuring: Toward socio-tenurial polarisation in Australia?

Evidence of socio-tenurial polarisation in Britain is presented against a backdrop of significant change in tenure ratios. 'Great Britain has changed from being a nation of tenants (over 90 per cent of households were the tenants of private landlords in 1914) to a nation of home owners (some 66 per cent in 1989)' (Murie 1991:351). As home ownership in Britain expanded throughout the century, the sector became increasingly heterogeneous. In contrast, the public rental sector has borne the most recent reduction in size as Conservative governments provided substantial financial inducements to tenants to take up their 'right to buy'. As wealthier tenants have done this in substantial numbers, the proportion of public tenants has fallen and the concentration of poorer tenants increased (Forrest and Murie 1994).

The British situation clearly illustrates the ways in which public policy can effect a restructuring of housing tenure ratios. Though in Australia a significantly changing tenure ratio does not characterise the recent history of the housing market, recent changes in public policy have played a key role in the shifting nature of housing consumption in Australia (Kemeny 1981; Bourassa, Greig and Troy 1995). As Yates states, 'From the post-war period through to the 1980s, Australia's housing system was dominated by tenure-based policies directed towards home ownership and the provision of public housing. Private tenants were virtually excluded from housing assistance of any form. The 1990s, however, have seen an apparent U-turn in housing policies with elimination of explicit home ownership policies, the withdrawal from direct involvement in public housing funding and a rapid expansion of rental assistance for private tenants' (Yates 1997:265). Below we highlight the role of public policy in tenure restructuring by exploring how socio-tenurial polarisation may relate to changes in housing policy.

The home ownership rate in Australia has been around the 70 per cent mark since the early 1960s (Bourassa, Greig and Troy 1995). The private rental sector has housed approximately 20 per cent of households since the mid-1960s and, similarly, the proportion of public tenants has been around 6 per cent since that time (Yates 1994:28). However, this overarching tenure ratio obscures some evidence of the changing nature of housing consumption in Australia. For example, the home ownership rate has been sustained, despite a decline in affordability, due to the rise of the two-income household. Through the 1970s and 1980s real house prices, on average, rose more rapidly than average earnings. Consequently, it became necessary for a household to have two income earners to gain access to home ownership (Wulff 1982). 'In Australia, the vast majority of single income households have been gradually priced out of the market since the 1970s by rising interest rates and rising unemployment' (Yates 1997:274). As single income households are more likely to be on lower incomes than dual income households, this is an initial indication that a trend toward socio-tenurial polarisation could be under way.

Even setting aside the reasons for the rapid increase in real house prices, the causes of the changed nature of housing consumption, or tenure restructuring, are multi-faceted.(4) Changes in public policy have been instrumental. Direct assistance to home owners, through the First Home Owners Scheme, has collapsed from $290 million in 1984-85 to $5.9 million in 1993-94 (Dalton and Maher 1996:9). This changing ethos of housing policy occurred against a backdrop of economic restructuring of the labour market which saw an increasing rate of female labour force participation. This assisted the growth of the two-income household that has sustained the home ownership rate in recent times. This economic change, though, cannot be separated from cultural changes associated with the feminist movement that demanded greater equality for women and better access to the labour market. Demographic change has also played a role through the increasing number of smaller families, thus enabling women to stay in the work force longer or to return to the work force more quickly.

A second element of tenure restructuring is the dramatic shift in the ratio of purchaser owners to outright owners (Yates 1994). From 1961 (the high point of the home ownership rate so far this century) to 1976, the ratio of purchaser owners to outright owners steadily increased. In 1976, 36 per cent of households were purchaser owners compared with 32 per cent who were outright owners. Ever since 1976, this pattern has been in reversal so by 1991, 27 per cent of households were purchasers compared with 40 per cent who were outright owners (Yates 1994:27). The decreased affordability of home ownership, the rise in unemployment, delay in marriage and child-bearing, and the demographic ageing of the population all contribute to a trend that contains contradictory evidence of socio-tenurial polarisation. On the one hand, if the increased proportion of outright owners tend to be in retirement and on lower incomes, this change will reduce the extent of socio-tenurial polarisation as the increased numbers of home owners would be at the bottom end of the income spectrum. On the other hand, if the remaining purchaser owners are more likely to be on higher incomes, this will accentuate any trend toward socio-tenurial polarisation.

Though trying to assess the reasons for tenure restructuring is extraordinarily complex, it is possible to eliminate any explanation of the changing demographic make-up of home ownership that imputes a cultural preference for this tenure among a certain section of the population. Dual income or high income households do not express a stronger preference for home ownership than low income households. The array of housing and tenure preference studies completed in Australia shows an overwhelming preference for home ownership among all sections of the population (Wulff 1993).

A third element of tenure restructuring relates to the private rental sector. The private rental sector had been neglected by housing researchers and this led to a widespread acceptance of certain assumptions about its nature; in particular, that its primary role was as a short-term transitional housing tenure. More recently, it has become clear this is not the case and, indeed, may not have been so for a considerable period of time. Some 40 per cent of households in the private rental sector have rented continuously for more than ten years (Wulff 1997), and a high proportion of households in this tenure suffer affordability problems with considerable amounts of available income devoted to meeting rent payments (Yates 1997:269). These two points suggest a large number of households are trapped in the private rental sector by the weight of their rent payments and consequent inability to save the deposit needed for entry to home ownership. The long-term entrapment of poorer households in this less desired form of tenure again points to an emergent trend of socio-tenurial polarisation in Australia.

As a measure of the extent of the growing affordability problem within the private rental sector and the changing nature of its demographic make-up, there has been a sevenfold increase in budget outlays on private rent assistance over the past decade from just over $200 million in 1985 to $1.6 billion in 1995 (Yates 1997:269). Yates (1997:276), linking this change to aspects of social polarisation, points out that this increased rent assistance is long overdue and represents a delayed response to economic, technological and social changes. These changes have resulted in a widening of inequality in the distribution of earnings and higher rates of unemployment. This has particularly affected those in low skilled jobs and who, in turn, are those most likely to be in the private rental sector long term.

The systemic interlinking of housing tenures means changes in one tenure have a flow-on effect in another. The increasing affordability problem in the private rental sector can be, in part, attributed to the increasing difficulty of accessing home ownership, and to an increased targeting of public housing toward those with the greatest assessed need in Australia.

In Australia the public rental sector has, in comparison with Britain, always been a minority tenure. Australian governments have been reluctant landlords (Hayward 1996), with currently 6 per cent of national housing stock in this tenure form, though there are significant State variations. However, despite the small size of the public rental sector, since the 1978 Commonwealth State Housing Agreement and the introduction of market rents, public housing has increasingly become welfare housing (Paris, Williams and Stimson 1985). This is a fifth element of tenure restructuring in Australia. This process has comprised a reduction in the social mix of public tenants so today 86 per cent of public tenant families are Department of Social Security recipients (Council of Australian Governments, press release, 14 June 1996). The role of, and changes in, housing policy in tenure restructuring is again to the fore. These changes to home ownership and public renting restricted entry to each tenure and placed increased demand upon the private rental housing available. This has led to low vacancy rates and increased rentals.

The broad thrust of these elements of tenure restructuring and indicators of socio tenurial polarisation is home ownership is increasingly becoming the preserve of households with two incomes, while the rental tenures host those who are poorer, have an uncertain labour market position, and often economically dependent upon DSS payments. Such trends provide initial evidence of socio-tenurial polarisation in Australia. However, because approximately 70 per cent of all households are in home ownership, the evidence is ultimately inconclusive. With such apparent wide access to home ownership, the housing market continues to have a broad, bulging middle that is inclusive of a wide range of income groups rather than being closed to those of lower income or occupational status. The precise distribution of occupation or income groups across housing tenures is examined in the following section through analyses of the Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS).

An empirical investigation of socio-tenurial polarisation in Australia

The ALCS is a national random telephone survey conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies during the final part of 1996. A total of 2685 respondents participated in the survey, aged mainly between 25 and 70 years old. A small number of persons under 25 years old who had one or more children were also included in the survey (1 per cent of the sample).(5)

The data analysis explores the distribution of households across housing tenures and their occupational and income characteristics. Evidence of socio-tenurial polarisation would be a clustering of high skilled and high income households in the more preferred housing tenure of home ownership, and a corresponding concentration of low skilled and low income households in the non-preferred housing tenures. The tenure divisions of the housing market would be reflecting the occupation and income divisions of the labour market.

Determining whether socio-tenurial polarisation has occurred in recent years in Australia is limited by the quality of the available data. A key difficulty is people's current housing circumstances will, in many cases, reflect a past earning capacity and/or an accumulation of wealth over a lifetime rather than their current income as is typically measured in surveys, including in ALCS. As a result, cross sectional analyses may not account accurately for the distribution of people across housing tenures, and does not account for the dynamic relationship between contemporary household characteristics and housing consumption (Pickles and Davies 1985). Therefore, longitudinal analyses are needed to accurately map the extent to which housing markets are, or are becoming, polarised.

With no longitudinal Australian housing data available, the ALCS, with its cross sectional and retrospective data on housing histories or housing careers, offers some starting points for answers to questions about socio-tenurial polarisation in two ways. While neither of these alone provides definitive answers to questions about socio-tenurial polarisation, each provides some guidance about what kind of changes may be taking place in contemporary Australia. First, cross-sectional analyses of housing tenure by variables of occupation and income are presented. Second, housing careers data and data from various surveys conducted at different points in time are presented to assess the change in the extent of socio-tenurial polarisation over time. At this point, a definition of key terms is necessary.

The economically active

In an attempt to control, at least in part, for the fact that current housing tenure may not reflect current earnings nor current employment, those households with no one participating in the labour market are excluded, and only the 'economically active' included in the analysis.(6) These include all respondents who are in paid work, on leave from paid work, or looking for paid work. Those respondents who may not be in paid work but who have a partner they are currently living with who is in paid work, on leave from paid work, or looking for paid work are also included. The economically active group used for the analysis are presented by tenure, with the total group of respondents in the ALCS sample, in Table 1.

| Tenure | |

|---|---|

| Economically active | Total sample |

| Outright owners | 34.6 |

| Purchaser owners | 43 |

| Public tenants | 2.6 |

| Private tenants | 16 |

| Other | 3.8 |

| Total | 100 |

| Outright owners | 40.2 |

| Purchaser owners | 37.5 |

| Public tenants | 3.4 |

| Private tenants | 15.2 |

| Other | 3.6 |

| Total | 100 |

Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996.

Tenure hierarchies

Central to the discussion of socio-tenurial polarisation is the concept of a tenure rank order or hierarchy that recognises some tenures convey greater advantages than others and are consequently more eagerly sought. If there were no perceived and/or real differences in housing consumption by different tenure positions, the notion of socio-tenurial polarisation would be void. The analysis presented uses a 'simple tenure hierarchy' that prioritises and clusters tenures according to: the property rights they afford; whether or not there is mortgage debt on the property, and; whether the householder has chosen this form of housing consumption or, due to lack of affordable alternatives, has been 'forced' to reside there, see Table 2.

In this way, respondent households are classified into one of three categories. In the 'high' tenure category are 'owner investors' who have full property rights of use, control and disposal on their own properties plus landlord rights to a second (or more) property/ies; 'owner occupiers', who have full property rights of use, control and disposal to the house that they live in; and 'purchaser investors' who carry mortgage debt on the property they live in but also have landlord rights to a second (or more) property/ies.

In the 'middle' tenure category are: 'purchaser occupiers' who have entered the ownership market but carry mortgage debt; 'private renter investors' who choose to rent in the private rental sector and have landlord rights to one or more properties, and those who choose to rent in the private rental sector. In the 'low' tenure category are those households who feel 'forced' to rent in the private rental sector as they cannot afford a preferred option, and who endure limited use rights and little control or security; and public tenants who also endure limited property rights as the security of tenure provided by the government provided is now dissipating.

| Tenure hierarchy classifications | % |

|---|---|

| Tenure hierarchy | |

| Outright owners | 34.6 |

| Purchaser owners | 43 |

| Public tenants | 2.6 |

| Private tenants | 16 |

| Other | 3.8 |

| Simple tenure hierarchy | |

| ‘High’ Owner investors Owner occupiers Purchaser investors | 41.6 |

| ‘Middle’ Purchaser occupiers Private renter investors Private tenant by choice | 45.1 |

| ‘Low’ Private tenants (non-choice) Public tenants | 13.3 |

Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996

Note: Figures calculated using only economically active households.

The cross-sectional analysis

Using the simple tenure hierarchy, socio-tenurial polarisation is examined through cross-sectional analysis, in the first instance, to determine how current occupational and income circumstances relate to a person's housing tenure.(7) Compared to the proportion of managers/administrators in the sample overall, Table 3 suggests there is an overrepresentation of managers/administrators in the 'high' tenure category. With only 30 per cent of plant/machine operators in the 'high' tenure category, this occupational group is underrepresented. The remaining occupational groups are evenly represented in the 'high' tenure category. For example, 37 per cent of labourers (at the bottom of the occupational hierarchy), are in the 'high' tenure category, and 39 per cent of professionals (at the upper end of the occupational hierarchy) are also in the 'high' tenure category.

The table can also be viewed on page 13 of the PDF.

| Tenure | Labourers | - Plant/ Machine Operators | Personal Service Workers | Clerks | Trades people | Para-professionals | Professionals | Managers & Admin | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 37 | 30 | 34 | 36 | 36 | 38 | 39 | 54 | 41 |

| Middle | 31 | 51 | 41 | 49 | 51 | 50 | 51 | 40 | 46 |

| Low | 32 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 13 |

Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996.

Notes: Figures calculated using only economically active households.

Totals may not equal 100 due to rounding.

ABS 1992 Australian Standard Classification of Occupations, Catalogue No. 1229.0.

Within the 'middle' tenure ranking, the representation of groups across the occupational spectrum is quite even. No one occupational group is substantially overrepresented and only one (labourers) is considerably underrepresented. In the 'low' tenure category, we see an underrepresentation of managers/administrators and a substantial overrepresentation of the less skilled occupational groups of personal service workers, plant/machine operators and labourers.(8) This represents a clustering of less skilled workers in the 'low' tenure category, but appears to be the only significant cluster within the table.

We do not find a substantial under representation of the less skilled in the 'high' tenure category. Nor is there the clustering of higher skilled occupational groups in the 'high' tenure category and corresponding underrepresentation of these groups in the 'low' tenure category that would be expected in a pattern of socio-tenurial polarisation. Rather, the pattern tends toward one of 'marginalisation'. There is a strong clustering at the 'low' tenure hierarchy but even spreads across the 'middle' and 'high' tenure categories. A polarised tenure structure would have clusters top and bottom - this structure appears only to have a cluster at the bottom.

The median incomes of the 'high', 'middle' and 'low' tenure categories, generally reflect this same pattern of marginalisation at the bottom. The 'high' and 'middle' tenure groups each have a median household income of approximately $4,200 per month; considerably higher than the 'low' tenure group with a median monthly household income of $2,500. The largest hurdle in the tenure hierarchy is between the bottom and the middle. Once a household has made it to the 'middle', the hierarchy is reasonably flat, suggesting again that in Australia the relationship between the labour market and the housing market is one of socio-tenurial marginalisation rather than polarisation.

Analysis of the distribution of income deciles across the tenure groups shows a very similar pattern to occupational distribution (Table 4). In the 'high' tenure group, it is only the highest (10th) income decile that has any considerable overrepresentation. All other income deciles, including the lowest, are well represented in this 'high' tenure category. It should be noted the analysis is based only on households that are economically active. In the 'middle' tenure group, the lowest income decile is considerably underrepresented and income deciles 2 and 3 are somewhat underrepresented. Income deciles 4 to 9 have similar levels of representation that are close to the percentage (46 per cent) of all households in this tenure group. The highest income decile is underrepresented in the 'middle' tenure group. The 'low' tenure group again shows the strongest pattern of clustering. There is overrepresentation from income deciles 1 to 5, then a fall down to a pattern of underrepresentation among income deciles 6 to 10. The overrepresentation is considerable among deciles 1 and 2 and the underrepresentation considerable among deciles 9 and 10.

| Tenure hierarchy | Income deciles | Total % | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest | Highest | ||||||||||

| High | 35 | 36 | 41 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 40 | 39 | 42 | 57 | 40 |

| Middle | 30 | 40 | 42 | 49 | 45 | 55 | 51 | 55 | 54 | 39 | 46 |

| Low | 35 | 23 | 17 | 15 | 17 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 14 |

Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996

Notes: Figures calculated using only economically active households.

Totals may not equal 100 due to rounding.

As with the data for occupation, while there is evidence of a cluster of low income deciles in the 'low' tenure group and an underrepresentation of high income deciles, the reverse pattern does not hold for the 'high' tenure group (Table 4). There is not a significant clustering of the high income deciles and significant underrepresentation of the low income deciles in the 'high' tenure category. The pattern, with a stronger clustering at the bottom of the tenure hierarchy than at the top, and a broad even middle of representation extending a long way through the occupational and income hierarchies, is one of marginalisation. The less skilled and low paid are concentrated in the 'low' tenure category, but significant proportions of these households are still able to access the 'middle' and 'high' tenure categories.

The extent to which a permanent barrier to the 'middle' and 'high' tenure categories is emerging for less skilled and low paid workers is of key importance. If the 'low' tenure categories are temporary stepping stones to the more preferred tenures, and less skilled and low paid households leave the low tenure category (as typically happened in post-war Australia) then such overrepresentation, assuming it is temporary for any one household, is of less concern. If, however, less skilled and low paid households are effectively locked out of the more preferred tenure options, it is clear the housing market will be working to marginalise these groups in the same way the labour market is. The extent to which this is happening is the focus of analysis in the next section.

Socio-tenurial marginalisation: Change over time?

While the cross-sectional analysis suggests Australia may be experiencing socio tenurial marginalisation rather than polarisation, cross-sectional analysis of labour and housing market position is, in some ways, problematic. Current housing tenure may often reflect past earnings and/or employment. To further examine whether socio-tenurial marginalisation is occurring in Australia, the second stage of empirical inquiry presented here looks at change over time and is primarily concerned with the following question: Are fewer households entering home ownership? And, if so, to which occupational and income groups do they belong? Answers to these questions will help us understand whether the observed socio tenurial marginalisation is likely to represent a permanent 'lock-out' from home ownership for the low paid and less skilled. They will also give an indication as to whether such marginalisation could, over time, develop into socio-tenurial polarisation.

Two points indicative of a 'lock out' from home ownership for the low skilled and low paid are that, whereas from the 1950s to the 1970s the public rental sector acted as a stepping stone to home ownership, households that now enter the public rental sector seldom leave it. 'That public rental is a final destination tenure (the last stage of a housing career) is suggested by the minuscule scale of home purchase or private renters drawn from the public rental sector. Only 2.5 per cent of purchasers and 2 per cent of private renters were formerly public tenants' (Wulff and Newton 1995:12). Second, as already stated, the proportion of private tenants who remain in the sector long term (more than ten years) was 40 per cent in 1994 (Wulff 1997). It will be important to monitor this figure over the coming years.

In examining access to home ownership as a further indicator of socio-tenurial polarisation or marginalisation, Yates (1994) compares Australian survey findings at two points in time to demonstrate that while home ownership remains the preferred housing tenure in Australia, entry into home ownership is becoming increasingly difficult for some sectors of the community (Tables 6, 7 and 8 in endnotes).(9) Yates compares access to home ownership between 1975-76 (Table 6) and 1991 (Table 7) by examining the proportion of each survey sample who were outright owners or purchaser owners at each time period in terms of age and income of respondents. In 1975-76, 4 per cent of low income under 30 year olds were outright owners, and 19 per cent of the same group were purchaser owners. Yates shows that by 1991 these figures had fallen so that 3 per cent of low income under 30 year olds owned their home outright, and the proportion of this group who were purchaser owners fell by over 50 per cent to only 8 per cent. The comparison indicates that, between 1975-76 and 1991, those increasingly less likely to be found entering home ownership are the youngest age groups in the lowest two-thirds of the income distribution (Yates 1994).

Using the ALCS data to replicate the Yates analysis (see Table 8 in endnotes) confirms that in 1996, only small percentages of low income young people are able to enter home ownership.

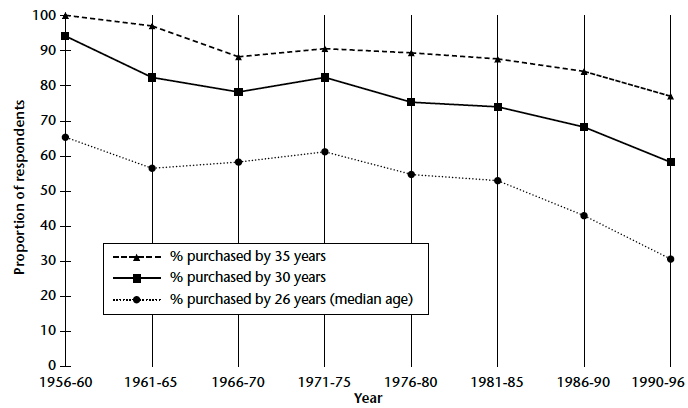

Given that the rate of entry into home ownership for young people appears to be decreasing, the question raised is whether these households are simply delaying entry to home ownership, or are permanently locked out of home ownership. A longitudinal data set of housing careers is ideally required to resolve this issue. In the absence of such a data set in Australia, Figure 1 uses retrospective housing careers data from the 1996 ALCS to show the proportion of respondents who entered home ownership for the first time (as purchaser or outright owner) between 1956 and 1996, by the median age of entry into home ownership for the sample as a whole (26 years), by age 30 years, and by age 35 years.(10) The downward trend of each line clearly illustrates that the percentage of households entering home ownership at a young age is decreasing.(11)

Figure 1. Percentage of current home owners who entered home ownership by 26 years (median age), 30 years and 35 years, by year of purchase

Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996.

Of those home owners who bought in 1990-1996, only 31 per cent were of the median age of entry to home ownership (26 years). This compares with a figure of 66 per cent for those home owners who bought in 1956-1960. Of those who entered home ownership in 1956-1960, all had done so by the age of 35. In 1990-1996, only 78 per cent of those who entered home ownership had done so by age 35, leaving just over a fifth to make their first entry to home ownership after age 35.

An analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics of those households delaying their entry to home ownership until after age 35, between 1981 and 1996, reveals they come from a range of occupational and income circumstances.12 Interestingly, this informs us that the low skilled and low paid do not dominate late entrants to home ownership. It appears increasingly likely that if the low skilled and low paid do not enter home ownership prior to age 35, they never gain entry.

Furthermore, the latest Census displays a continuing fall in the overall home ownership rate (Table 5). The 1996 figure of 66.4 per cent (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1997:1) is the lowest since 1954 and marks 15 years of decline in the home ownership rate in Australia. This again suggests the plausibility of the fact that low income groups are being locked out of home ownership; some permanently, others for at least decades.

| 1954 | 1961 | 1966 | 1971 | 1976 | 1981 | 1986 | 1991 | 1996 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner/ purchaser 63.3 | 70.3 | 71.4 | 68.8 | 68.4 | 70.1 | 69.1 | 67.3 | 66.4 |

Sources: Bourassa, Greig and Troy 1995: 85; and Australian Bureau of Statistics 1997:1.

The cross-sectional analysis of the ALCS demonstrates a pattern of socio-tenurial marginalisation; that is, a clustering of low skilled and low paid households in less preferred tenure forms. The second step in the analysis then explored whether such marginalisation was permanent or temporary, effectively asking whether the rental tenures were still acting as stepping stones to home ownership as they had done in Australia from the 1950s to the 1970s. Though the analysis is not conclusive, due to a lack of accurate longitudinal data, the trend would appear to be that young, low income households are entering home ownership in very small percentages and they do not appear to be catching up in later years. This suggests the rental tenures are no longer stepping stones, but that many households spend significant parts of their housing careers in these sectors, especially if they are low skilled and low paid. The continuing decline in the home ownership rate also indicates some households are being locked out of home ownership permanently.

Conclusion

The paper set out with four aims. The first was to extend empirical investigation of socio-tenurial polarisation in an Australian context. On the basis of a cross sectional analysis of data from the 1996 Australian Life Course Survey, this empirical investigation found little evidence of socio-tenurial polarisation but concluded there was evidence of socio-tenurial marginalisation. Polarisation demands a clustering at both the top and bottom of the tenure hierarchy; that is, a cluster of high skilled and high income households at the top of the tenure hierarchy and a cluster of low skilled and low paid households at the bottom of the tenure hierarchy. The empirical evidence in this paper found only a cluster of low skilled and low paid households at the bottom of the tenure hierarchy and we refer to this as socio-tenurial marginalisation.

The extent to which socio-tenurial marginalisation should be a focus of policy concern, we argue, depends upon the duration of the experience of this marginalisation. Socio-tenurial marginalisation is particularly problematic if the housing market is now operating as a permanent barrier of social disadvantage. This was not the case in Australia from the 1950s to the 1970s when the rental tenures acted as stepping stones through to home ownership. Thus, the second component of the empirical investigation undertaken was to ascertain whether socio-tenurial marginalisation is becoming a more permanent aspect of the Australian labour-housing market nexus, rather than a temporary starting point of a housing career.

The evidence at the bottom of the tenure hierarchy is that those households who enter the public rental sector seldom leave (Wulff and Newton 1995). The public sector is then no longer a stepping stone to home ownership. Evidence from the private rental sector is that 40 per cent of tenants have been in the sector for more than ten years (Wulff 1997). For this group of households, the private rental sector is clearly not a stepping stone to home ownership. These households may eventually leave the private rental sector, but many occupy it for a considerable period of time. Home ownership is increasingly difficult to enter for low income, young households, and fewer and fewer are doing it. Only a small number appear to be able to 'catch up' after the age of 35. The declining overall home ownership rate also indicates many such households may never enter home ownership.

The second aim of this paper was to use the findings from our empirical investigation to inform theoretical debate about the interrelationship of production and consumption-based inequalities. The literature trail that informs upon the production-consumption interrelationship took us from the housing classes debate through to the globalisation and social polarisation thesis.

In the empirical investigation referred to above, the variables of occupation and income were used in the paper to represent production-based inequalities. The variable of housing tenure was used to represent consumption-based inequalities. Our empirical findings lead us to conclude that the housing market appears to be acting to ameliorate rather than exacerbate those inequalities arising from the labour market. The housing consumption prize in Australia is home ownership. The analysis above shows, that, in terms of housing tenure (but not housing quality, location or type) low skilled and low paid households are attaining the key prize of home ownership in proportions near equal to those in higher occupational and income groups. There is only a slight underrepresentation of low skilled and low paid households at the top of the tenure hierarchy. Consumption based inequalities, such as housing tenure, are then not determined by production based inequalities.

The key way in which production-based inequalities appear to shape consumption-based inequalities is in relation to the clustering of low skilled and low paid households at the bottom of the tenure hierarchy. Further work is needed, however, to more clearly ascertain the extent to which this is a phenomenon of recent labour market restructuring, or whether the labour-housing market nexus has produced such outcomes for a number of decades.

The third aim of this paper was to bring contemporary information on changes in the nature of housing consumption to bear on policy debates that are a part of the reshaping of housing consumption in Australia. Section three recalled recent changes in housing policy, and the well-documented part these reforms have played in reshaping the nature of Australian housing consumption. By connecting policy change to tenure restructuring, and then exploring its interrelationship with a restructuring labour market, our intention was to make clear the broader social outcomes of an all too often, narrowly-focused housing policy discourse. Though it is not possible to make definitive claims for the empirical findings presented above, not even the least generous interpretation of the data could suggest that the drift of time sees an improvement in the nature of the housing careers of Australian families. The indications are that for particular low skilled and low paid social groups, their housing consumption is increasingly likely to become a further element of permanent disadvantage. This was not the case 15 years ago in Australia.

The fourth aim of this paper was to continue to connect housing research that is policy relevant to broader debates in social theory from an Australian perspective. The paper is purposefully structured to enable discussion and integration of issues that are of central importance to contemporary housing policy. In this way, it allows contemporary empirical information to be interpreted within a social theoretical framework. Such a theoretical framework directs our attention to understanding the role and significance of housing within a broader social setting; in this paper, in relation to the labour market and, more particularly, the Australian labour market. This adds to the wealth of American and European empirical information available, and adds to our theoretical understanding of the interaction of labour and housing markets.

Endnotes

- The term home ownership/home owners includes both purchaser owners and outright owners.

- Analyses of 'socio-tenurial polarisation' typically examine the interrelationship of economic variables such as occupation and income with housing tenure. Use of the concept 'socio' to refer to these economic variables lacks precision, though the term is in sufficient wide use for us to continue using it in this paper.

- Interestingly the origins of this work are less in the housing classes debate of urban sociology and more within urban geography. Despite the common concerns of the two literatures, they have rarely spoken to one another.

- Isolating the causal factors in tenure restructuring, though analytically appealing, is empirically complex. The range of factors at work is apparent but not their relative strengths. Nonetheless, valiant attempts to disentangle the causal web continue. Paris agues '...that demographic components of social change appear to have a relative autonomy from other processes of change, although inter-causality between demographic and other factors must always be recognised' (1995:1641). This delicate balancing act presumably allows for the demographic factors to be autonomous 'in the last instance'. See also Bourassa, Greig and Troy (1995: 84) who argue for a priority of economic change over the political through the 1980s, echoing the debate between Kemeny (1981) and Berry (1988) about the cause of the growth of home ownership after World War II.

- Due to the specific age range of respondents to the Australian Life Course Survey (generally between 25 and 70 years), results of the survey differ from national estimates in a number of ways. Comparisons of the tenure distribution between the ALCS and ABS (1994) Australian Housing Survey indicate that the main differences between the ALCS sample and national estimates are that purchaser owners are overrepresented in the ALCS sample (37.5 per cent compared with national estimates of 28.3 per cent); public tenants are underrepresented (3.5 per cent compared with 6.2 per cent); and private tenants are underrepresented (15.2 per cent compared with 19.0 per cent). Despite these age-related differences, comparison of tenure by age indicates that, for the main age ranges included in the ALCS survey (25 to 70 years), the distribution of tenure groups by age compares well with national estimates (Mills 1997).

- For the purposes of defining labour market and income groups throughout this analysis, 'household' refers to the labour market or income status of the survey respondent and/or partner of the respondent.

- Household occupation was defined by the highest occupation in the household. It is assumed that the ASCO classification does represent a hierarchy of occupational positions.

- The same pattern is found in a cross-tabulation where a more expanded version of the tenure hierarchy is examined by occupation, though the table is not included here as cell numbers become low in some of the smaller tenures.

Table 6. Outright owners and purchaser owners by household income and age 1975–76 Household income Tenure Age of respondent < 30 30–44 45–64 65 + Total % Low (<$140 pw) Outright owner 4 23 52 73 50 Purchaser owner 19 36 18 5 16 Medium ($140–$260) Outright owner 5 15 49 83 27 Purchaser owner 40 57 32 7 41 High ($260+) Outright owner 4 16 37 71 24 Purchaser owner 47 61 48 15 51 Total Outright owner 4 17 45 74 33 Purchaser owner 39 55 34 6 37 Source: 1975–75 HES, ABS Cat. No. 6517.0, in Yates 1994, p. 29.

Table 7. Outright owners and purchaser owners by household income and age 1991 Household income Tenure Age of respondent < 30 30–44 45–64 65 + Total % Low (<$400 pw) Outright owner 3 17 60 81 58 Purchaser owner 8 21 8 4 8 Medium ($400–$800) Outright owner 7 23 63 84 40 Purchaser owner 22 44 21 6 29 High ($800+) Outright owner 6 23 61 90 38 Purchaser owner 34 56 30 3 40 Total Outright owner 6 22 61 82 45 Purchaser owner 25 47 22 4 27 Source: HALCS unit record data, in Yates 1994, p. 30.

Table 8. Outright owners and purchaser owners by household income and age 1996 Household income Tenure Age of respondent < 30 30–44 45–64 65 + Total % Low (<625 pw) Outright owner 3 25 61 76 43 Purchaser owner 8 21 9 2 12 Medium ($625–$1,038) Outright owner 8 28 64 97 39 Purchaser owner 34 42 18 3 32 High ($1038+) Outright owner 5 26 65 94 40 Purchaser owner 47 55 26 6 42 Total Outright owner 6 27 64 82 42 Purchaser owner 29 41 18 2 28 Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996.

Notes: Figures in Tables 6, 7 and 8 are calculated using only economically active households, using data weighted by tenure to ABS 1994 Australian Housing Survey, Cat. No. 4182.0, primarily to correct an overrepresentation of purchaser owners in the sample.

Totals may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Clearly, using different sources of data for the different time periods (1975–76, 1991 and 1996) raises a number of statistical concerns about the accuracy and comparability of results. Rather than focusing upon actual percentage figures, 1996 data are presented here to provide an indication of support or otherwise for the trend in home ownership identified by Yates, and must be interpreted as such.- While the cross-sectional analyses presented above includes economically active respondents only, for the purposes of examining historical housing trends, the time-based analyses presented here include the total ALCS sample.

- That older survey respondents have had the opportunity to enter home ownership at a relatively late age (for example, during the 1980s or 1990s) as compared with other age groups who have not, may act to steepen the slope seen in this graph. However, the trend toward delayed entry into home ownership remains clear.

Table 9. Occupations of respondents who entered home ownership after age 35, between 1981–1996 Occupation % Administrators & managers 23 Professionals 23 Para-professionals 9 Tradespersons 15 Clerks 12 Personal service workers 10 Plant/machine operators 5 Labourers 5 Total 100 Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996.

Notes: Figures calculated using all households.

Totals may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Includes previous occupations of retirees.Table 10. Household income deciles of respondents who purchased after age 35, between 1981–1996 Income Decile % Decile 1: Highest 10 % income 10 Decile 2 11 Decile 3 9 Decile 4 11 Decile 5 6 Decile 6 10 Decile 7 11 Decile 8 9 Decile 9 11 Decile 10: Lowest 10 % income 12 Total 100 Source: Australian Life Course Survey, Australian Institute of Family Studies 1996.

Notes: Figures calculated using all households.

Totals may not equal 100 due to rounding.

References

- ABS (1992), Australian Standard Classification of Occupations (ASCO): Keyword Index to Occupation Definitions, Catalogue No. 1229.0.

- ABS (1994), Australian Housing Survey Selected Findings, Catalogue No. 4181.0.

- ABS (1996), Social and Housing Characteristics, Australia, Catalogue No. 2015.0.

- ABS (1997), Housing Occupancy and Costs, Commonwealth of Australia, Catalogue No. 4130.0.

- Badcock, B. (1989), 'Home ownership and the accumulation of real wealth', Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 69-92.

- Badcock, B. (1992a), 'Adelaide's heart transplant, 1970-88:1. Creation, transfer, and capture of 'value' within the built environment', Environment and Planning A, vol. 24, pp. 215-241.

- Badcock, B. (1992b), 'Adelaide's heart transplant, 1970-88: 2. The 'transfer' of value within the housing market', Environment and Planning A, vol. 24, pp. 323-339.

- Badcock, B. (1994), 'Snakes or ladders? The housing market and wealth distribution in Australia', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 609-627.

- Badcock, B. (1995), 'The 'family home' and transfers of wealth in Australia', in R. Forrest and A. Murie (eds) Housing and Family Wealth: comparative international perspectives, Routledge, London.

- Badcock, B. and Browett, M. (1992c), 'Adelaide's heart transplant, 1970-88: 3. The deployment of capital in the renovation and redevelopment submarkets', Environment and Planning A, vol. 24, pp. 1167-1190.

- Baum, S. (1997), 'Sydney, Australia: a global city? Testing the social polarisation thesis', Urban Studies, vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 1181-1901.

- Baum, S. and Hassan, R. (1992), 'Economic restructuring and spatial equity: A case study of Adelaide', Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 151-172.

- Berry, M. (1986), 'Housing provision and class relations under capitalism', Housing Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 109-121.

- Berry, M. (1988), 'To buy or rent? The demise of a dual tenure housing policy in Australia, 1945-60', in R. Howe (ed.) New Homes For Old, Ministry of Housing and Construction, Victoria.

- Berry, M. and Rees, G. (1994) 'Australian urban and regional research: an introduction', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 49-54.

- Borland, J. (1992), Wage Inequality in Australia, National Bureau of Economic Research, Boston.

- Bourassa, S., Greig, A. and Troy, P. (1995), 'The limits of housing policy: home ownership in Australia', Housing Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 83-104.

- Burbidge, A. (1997), Capital Gains and Economic Inequality, SPRC Conference University of NSW, Sydney 16-18 July 1997.

- Burnley, I. and Forrest, J. (1995), 'Social impacts of economic restructuring on immigrant groups', Australian Quarterly, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 69-84.

- Castles, F. (1985), The Working Class and Welfare, Allen and Unwin, Sydney.

- Castles, F. (1997), 'The institutional design of the Australian Welfare State', International Social Security Review, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 25-41.

- Cox, K. (1989), 'The politics of turf and the question of class', in M. Dear and J. Wolch (eds) The Power of Geography, Unwin Hyman, London.

- Dalton, T. and Maher, C. (1996), 'Private renting: Changing context and policy directions', Just Policy, 7, pp. 5-14.

- Davis, M. (1990), City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, Verso, London.

- De Leon, R. (1992), Left Coast City: Progressive Politics in San Francisco, 1975-1991, University Press of Kansas, USA.

- Dunleavy, P. (1979), 'The urban basis of political alignment: social class, domestic property ownership and state intervention in consumption processes', British Journal of Political Science, 9, pp. 409-443.

- Edel, M. (1982), 'Home ownership and working class unity', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 6, pp. 205-222.

- Fagan, B. (1986), 'Industrial restructuring and the metropolitan fringe: growth and disadvantage in western Sydney', Australian Planner, 24, pp. 11-17.

- Forrest, J. (1995), 'Social impacts of economic restructuring in Australia', Australian Quarterly, vol, 67, no. 2, pp. 43-53.

- Forrest, R. and Murie, A. (1994) The Resale of Former Council Homes, HMSO, London.

- Forster, C. (1986), 'Economic restructuring, urban policy and patterns of deprivation in Adelaide', Australian Planner, 24, pp. 6-10.

- Forster, C. (1990), Residential Differentiation, Inequality and Social Issues for Metropolitan Planning, Paper commissioned by the Adelaide Planning review, November.

- Gray, F. (1982), 'Owner occupation and social relations', in S. Merrett with F. Gray Owner Occupation in Britain, Routledge Kegan Paul, London.

- Gregory, R. (1993), 'Aspects of Australian living standards: the disappointing decades 1970-90', Economic Record, vol. 69, no. 204, pp. 61-76.

- Gregory, R. and Hunter, B. (1995), The Macro Economy and the Growth of Ghettos and Urban Poverty. Paper to accompany the Telecom Address at the National Press Club (draft, mimeo).

- Hamnett, C. (1984), 'Housing the two nations: Socio-tenurial polarisation in England and Wales, 1961-81', Urban Studies, 43, pp. 389-405.

- Hamnett, C. (1991), 'Labour markets, housing markets and social restructuring in a global city: the case of London', chapter 7 in J. Allen and C. Hamnett (eds) Housing and Labour Markets: Building the Connections, Unwin Hyman, London.

- Hamnett, C. (1994), 'Social polarisation in global cities: Theory and evidence',Urban Studies, 31, pp. 401-424.

- Hamnett, C. (1996), 'Social polarisation, economic restructuring and welfare state regime', Urban Studies, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 1407-1430.

- Harloe, M. (1984), 'Sector and class: A critical comment', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 228-237.

- Hayward, D. (1986), The Great Australian Dream reconsidered, Housing Studies, vol 1, p. 213.

- Hayward, D. 1(996), 'The reluctant landlords? A history of public housing in Australia' Urban Policy and Research, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 5-36.

- Henderson, R., Harcourt, A. and Harper, R. (1970) People in Poverty: a Melbourne Survey, Cheshire, Melbourne.

- Houghton, S. (1987a), 'Social change and residential differentiation: Perth 1971-1981', Australian Geographical Studies, vol 25, pp. 57-66.

- Kemeny, J. (1981), The Myth of Home Ownership, Routledge Kegan Paul, London.

- King, R. (1987), 'Monopoly rent, residential differentiation and the second global crisis of capitalism: The case of Melbourne', Progress in Planning, vol. 28, pp. 195-298.

- Maher, C. (1996), 'The private rental market: Implications of restructuring and housing reform', National Housing Action, December, pp. 15-22.

- McAllister, I. (1984), 'Housing tenure and party choice in Australia, Britain and the United States', British Journal of Political Science, vol. 14, pp. 509-522.

- Mills, E. (1997), Life Course Fieldwork Report, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Mitchell, D. (1995) 'International comparisons of income inequality' in J. Nevile (ed.) As the Rich Get Richer: Changes in Income Distribution in Australia, Committee for Economic Development of Australia, Sydney

- Murie, A. (1991), 'Divisions of home ownership: Housing tenure and social change', Environment and Planning A, vol . 23, pp. 349-370.

- Murie, A. and Musterd, S. (1996), Social segregation, housing tenure and social change in Dutch cities in the late 1980s', Urban Studies, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 495-516.

- Murphy, P. and Watson, S. (1994), 'Social polarisation and Australian cities', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 573-590.

- NHS (National Housing Strategy) (1991), Australian Housing: The Demographic, Economic and Social Environment, Issues Paper 1, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

- Neutze, M. and Kendig, H. (1991), 'Achievement of home ownership among post-war Australian cohorts', Housing Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 3-14.

- O'Connor, K. and Stimson, R. (1994), 'Economic change and the fortunes of Australian cities', Urban Futures, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 1-12.

- Offe, C. (1984), Contradictions of the Welfare State, Hutchinson, London.

- Pahl, R. (1988), 'Some remarks on informal work, social polarisation and the social structure', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 247-267.