Towards COVID normal: The early release of superannuation, through a family lens

Families in Australia Survey report

September 2021

Diana Warren

Download Research report

Overview

To support people whose finances were adversely impacted by COVID-19, the Federal Government allowed people to access up to $10,000 of their superannuation between 20 April and 30 June 2020, and a further $10,000 in the second application period from 1 July to 31 December 2020. Over the duration of the early release of superannuation program, a total of 3.5 million initial applications and 1.4 million repeat applications were approved, with an average value of $7,638 per application and a total value of $36.4 billion (Australian Prudential Regulation Association [APRA], 2021).

Key messages

-

Most respondents who accessed superannuation through the early release program used the money to assist their family with the financial impacts of COVID, as was intended when the scheme was introduced.

-

Respondents in households where someone had accessed their superannuation early were more likely to report having taken other financial actions, such as cutting down on essential and non-essential spending. This suggests that most people who accessed their superannuation did so because of an immediate financial need.

-

Those who accessed their superannuation were more likely to report feelings of concern about their family's current financial situation, as well as their future financial situation. For some, concerns about the future were related to the impact that drawing down their superannuation savings would have on their income in retirement.

Introduction

To support people whose finances were adversely impacted by COVID-19, the Federal Government allowed people to access up to $10,000 of their superannuation between 20 April and 30 June 2020, and a further $10,000 in the second application period from 1 July to 31 December 2020. Over the duration of the early release of superannuation program, a total of 3.5 million initial applications and 1.4 million repeat applications were approved, with an average value of $7,638 per application and a total value of $36.4 billion (Australian Prudential Regulation Association [APRA], 2021).

Box 1: Requirements for early release of superannuation

To apply for early release of superannuation, individuals had to satisfy one or more of the following requirements:

- They were unemployed.

- They were eligible to receive a JobSeeker payment, youth allowance for jobseekers, parenting payment, special benefit or farm household allowance.

- On or after 1 January 2020, they were made redundant; their working hours were reduced by 20% or more; or if they were a sole trader, their business was suspended or there was a reduction to their turnover of 20% or more. (Treasury, 2020a)

The official guidance from the Australian Taxation Office was that 'to be eligible to withdraw an amount under the COVID-19 early release of super, the money released must be used to assist you to deal with the adverse economic effects of COVID-19' (Australian Taxation Office [ATO], 2021b).

The interim report on early release of superannuation (ATO, 2021a) showed that among those who applied in the 2019-20 financial year, 56% of approved applications were from male applicants, 87% were from Australian residents and 78% of approved applications were from people living in New South Wales, Victoria or Queensland. The most common request category for accessing superannuation was a reduction in working hours, making up 42% of approved applications in the first round. A further 17% were in the unemployed request category and 17% were receiving income support.

Evidence from surveys conducted while the early release of superannuation program was operating suggests that while most people who accessed their superannuation early had used, or planned to use, the money to assist their family to deal with the economic impacts of COVID, for some, the money accessed from superannuation was used for precautionary saving; that is, saving because of uncertainty about future income. In the Household Impacts of COVID-19 survey, run by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in May 2020, 57% of those who had applied for early access to their superannuation said that they had used, or planned to use, the money to pay household bills, mortgage, rent or other debts; and 36% said they had added it, or planned to add it, to savings (ABS, 2020). Preliminary findings from the 2020-21 Survey of Income and Housing indicate that the most common uses of these funds were either paying the mortgage or rent (29%) or for household bills (27%), while 15% of people used it to pay credit cards or personal debt, 13% added it to savings and 6% bought or paid off a vehicle (ABS, 2021). A survey of CBUS fund members who accessed their superannuation found that the decision to access superannuation funds was mainly motivated by a sense of need, but also a desire for financial security - the main reasons members gave for accessing superannuation were immediate financial need (59%) and concerns for future expenditure (27%), with those who had not experienced reduced working hours more likely to withdraw for future concerns or to protect their savings (Bateman et al., 2020).

In this report, data from the first and second AIFS Families in Australia Surveys are used to provide a snapshot of how Australian families made use of the early release of superannuation program, providing new insights into the characteristics of individuals and families who made use of this early access. The main contribution to the research is the family perspective on this analysis. While early access to superannuation was dependent on individual circumstances (see Box 1), it would be expected that decisions about accessing this superannuation and the uses of it would have been made in consideration of family circumstances.

Information about early access to superannuation by respondents and their partners allows us to get a better picture of the types of families who accessed superannuation early, which household members drew down their superannuation, and how the money was used. Examining the other financial actions taken and levels of concern about the family's financial situation in households where someone had drawn down their superannuation provides a clearer picture of the ways that families coped financially with the economic impacts of COVID and the impact of having accessed superannuation on families' financial wellbeing.

Data

Life during COVID-19 was the first survey in Families in Australia (AIFS' flagship survey series). The survey ran from 1 May to 9 June 2020, during the COVID19 (coronavirus) pandemic. Towards COVID Normal - the second survey in the Families in Australia series - ran from 19 November to 23 December 2020, when restrictions were no longer in place in most parts of Australia. All Australians aged 18 and over were eligible to participate, with participants recruited via paid and unpaid social media advertisements containing a weblink directing them to the survey. In the first survey, there were 7,306 respondents, of which 6,435 completed all survey questions. In the second survey, 4,866 participants responded, and 3,627 completed all survey questions.

The surveys captured information about changes in the employment, working hours and income of individuals and their partners, and the types of actions that families had taken in response to the financial impact of COVID-19 - including accessing superannuation early. Respondents were also asked to rate their levels of concern about their family's current and future financial situation. Open-text questions about how income and financial wellbeing were affected provided additional insights about how families coped financially during this period.

In the second survey, respondents who said that they, or a household member, had applied for early access to superannuation were asked which household member(s) had accessed their superannuation, how much money was drawn down, and what those funds were used for.1 This is the main source of data used in this research. In most cases, when reporting on access to early superannuation within the household, respondents have reported on this access by themself or an immediate family member - a partner or spouse, or an adult child, for example. Some have reported on housemates, with this particularly applying to young people in the sample.

The Families in Australia Survey is a non-probability sample and, as such, it is not representative of the Australian population. Compared to the Australian population, the second survey sample over-represents individuals who are: female, middle-aged, tertiary educated and those living with a spouse or partner. Residents of Victoria, the ACT and Tasmania were also over-represented. In the analysis presented in this report, post-stratification weights are used to compensate for bias resulting from over-representation of respondents with certain socio-demographic characteristics.2

Given the majority of respondents were women, the information provided by respondents about the experiences of their spouse or partner provides valuable additional insights, allowing us to better understand how families have made use of the early release of superannuation program. When examining respondent as well as partner data, the analysis is based on a reconstructed dataset that combines respondent and partner data into one file, effectively treating information provided by respondents about their spouse or partner as an additional observation in the data. This is used, for example, to examine age and gender differences in the amounts of superannuation accessed. Throughout this report, where information provided by respondents about their partners is used in this way, the results are described in terms of Families in Australia Survey participants.

1 For further details about the Families in Australia Survey sample, please refer to Carroll, Budinski, Warren, Baxter, and Harvey (2021).

2 Weights were derived using a raking approach (Kolenikov, 2014), using five demographic factors - age, gender, education level, state of residence and whether the respondent speaks a language other than English.

Early access to superannuation funds

In the first Families in Australia survey (May-June 2020), 11% of respondents said that they, or someone in their household, had accessed their superannuation. By the second survey (November-December 2020), almost a quarter of respondents (24%) said that they, or another household member, had accessed their superannuation in the last six months.3

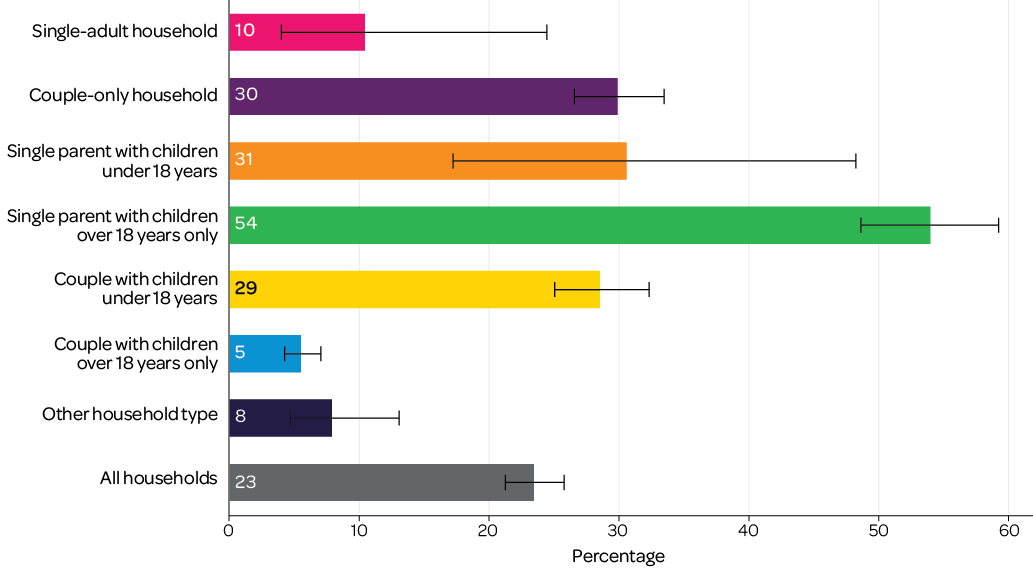

Among respondents in November-December 2020, reports of a household member having accessed their superannuation were most common among those in single-parent households with adult children (54%), compared to around 30% of respondents in couple-only households and single or couple parent households with children under 18 (Figure 1). Access to superannuation was less common in households made up of couples with adult children, and single-adult households (10%).

Figure 1: Someone in the household accessed their superannuation, by household composition

Notes: Other household types include single people or couples living with unrelated adults and single people or couples living with other relatives, including their parents, siblings or grandparents. For these household types, the number of observations was too small for reliable estimates.

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal. Weighted data used (n = 3,677). 95% confidence interval shown.

While access to superannuation was more common in households consisting of a single parent with adult children than for other household types, this household type makes up a relatively small proportion of the overall population. Data from the 2016 Census indicate that 38% of Australian households were couple-only households, and a further 45% of households were couple households with (dependent or non-dependent) children (Qu, 2020).

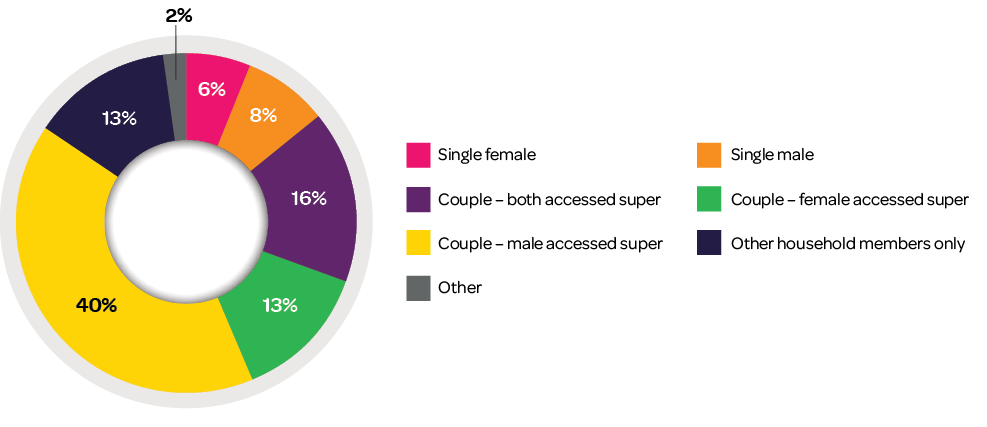

Among respondents of the second Families in Australia survey in households where someone had accessed superannuation, 37% were in couple-only households, 31% were in couple households with children under 18, 13% were single-parent households with children over 18 and almost one in 10 (9%) were single parents with children under 18. In couple households where someone had accessed their superannuation, the most common arrangement was that only the male had drawn down their superannuation (Figure 2).4 Still, one in six (16%) households where someone accessed superannuation were couples who had both drawn down their superannuation.

Figure 2: Which household members accessed their superannuation early?

Notes: The 'Other' category includes all other combinations of respondent, partner and other household members (this was almost always either the respondent or their partner, and another household member - only one respondent said that they, their partner and another household member had accessed their superannuation. Where household members other than the respondent or partner had accessed their superannuation, the household member was usually either an adult child of the respondent (57%) or an unrelated adult (28%).

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal. Respondents who reported that they or another household member accessed superannuation. Weighted data used (n = 499).

Of course, access to superannuation was dependant on whether individuals met the eligibility criteria for early release of super, as the aim of the program was to provide assistance to those experiencing financial distress due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

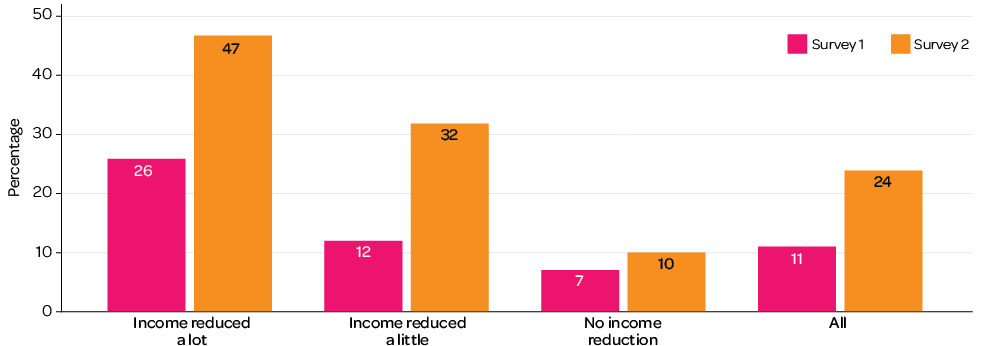

There were clear differences in the percentage of respondents who reported that someone in their household had accessed their superannuation, depending on whether they had experienced a reduction in income (Figure 3). Among respondents in the May-June 2020 survey who reported that their or their partner's income had been reduced a lot, more than a quarter said that someone in their household had accessed their superannuation, and for respondents surveyed November-December 2020 who reported a large reduction in (their or their partner's) income, almost half (47%) said that a household member had drawn down their super.

Figure 3: Respondent, or someone in their household, accessed superannuation early

Note: For respondents living with a spouse or partner, income changes refer to changes in respondent's or spouse/partner's income.

Source: Families in Australia Surveys: Life during COVID-19 and Towards COVID Normal, N = 6,428 ( first survey) and 3,729 (second survey). Weighted data used.

Characteristics of those who accessed their superannuation

Among Families in Australia second survey participants who had accessed their superannuation under the early release program, one in four (25%) had experienced a reduction in work hours, and one in five (21%) a reduction in their wage or salary (Table 1).5 One in seven (14%) had lost their job and just over one in 10 (11%) had been stood down temporarily. More than a third (35%) had not experienced any of these changes to their employment.

Among those who reported no changes to their employment, just over half (54%) were in paid employment at the time of second survey, one in five (19%) were retired, 14% were not working due to caring responsibilities and 11% were unemployed and would have been eligible for the early release program.6

For those living with a spouse or partner, the likelihood of drawing down superannuation may have also been impacted by changes to their partner's employment arrangements, changes that affected household income, such as a job loss or reduction in working hours. In couple households where only one person had accessed their superannuation, a considerable proportion of those who had drawn down superannuation had a partner who had experienced a change to their employment, such as a reduction in work hours (35%), a reduction in their wage (45%) or a job loss (32%).

| Employment change | % |

|---|---|

| Reduction in work hours | 25.3 |

| Reduction in wage or salary | 21.1 |

| Lost job | 14.2 |

| Stood down temporarily | 10.8 |

| Changed jobs | 10.5 |

| Made redundant | 4.6 |

| Had to close business | #2.3 |

| Stopped work for other reasons (retired, moved, had a baby) | 25.9 |

| None of the above | 35.0 |

Notes: Respondents were asked about changes to their and their partner's employment in the six months prior to the survey. Gender difference only apparent for changed job (Male 14%, Female 5%), and so have not been reported.

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal. Weighted (n = 563, combined respondent-partner data.) #Estimate not reliable, cell count < 20.

While approximately two-thirds of second survey participants who had accessed their superannuation early had experienced changes to their employment arrangements in 2020, almost 60% were in paid employment at the time of the survey (Table 2). Of those who were not in paid employment (around 40%), more than half were actively seeking employment, with significantly more males than females actively seeking paid work; and more females than males saying they preferred not to work for reasons other than caring responsibilities. Among those who had accessed their superannuation, 11% were receiving JobSeeker Allowance and 16% were receiving JobKeeper Allowance at the time of the survey.

| Employment status | Male (%) | Female (%) | All (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed | (59.9) | (56.7) | (58.5) |

| Working for an employer | 49.0 | 39.1 | 44.8 |

| Self-employed or business owner | 8.2 | 7.1 | 7.7 |

| Both employee and self-employed* | 2.7 | 10.5 | 6.0 |

| Not employed | (40.1) | (43.3) | (41.5) |

| Retired | 3.8 | 8.9 | #0.5 |

| Caring for children | 6.5 | 9.1 | 8.8 |

| Prefer not to work for other reason* | 1.4 | 8.4 | 5.1 |

| Looking for work* | 23.3 | 13.6 | 22.1 |

| Want to work, but not actively seeking employment | 5.0 | 3.3 | 5.0 |

| Receiving JobSeeker Allowance | 11.2 | 9.5 | 10.5 |

| Receiving JobKeeper Allowance | 19.6 | 10.7 | 16.2 |

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal. Weighted (n = 563, combined respondent-partner data (329 respondents, 234 partners). #Estimate not reliable, cell count < 20. *Indicates the gender difference is significant at the 5% level.

Reporting by survey participants in the open-text responses indicates the strong links between their experiences in employment, or those of other family members, and their need to access their superannuation funds. This family perspective is not surprising, particularly in families in which the income of the main or only income earner was negatively impacted in 2020.

Both myself and my partner have withdrawn super to get through this year due to changes with COVID though not directly related to our employment. Loss of tenants in rental properties and decrease in my partner's business.

Female, 52 years

I had to withdraw some of my super early because of bills being late due to not enough work.

Female, 55 years

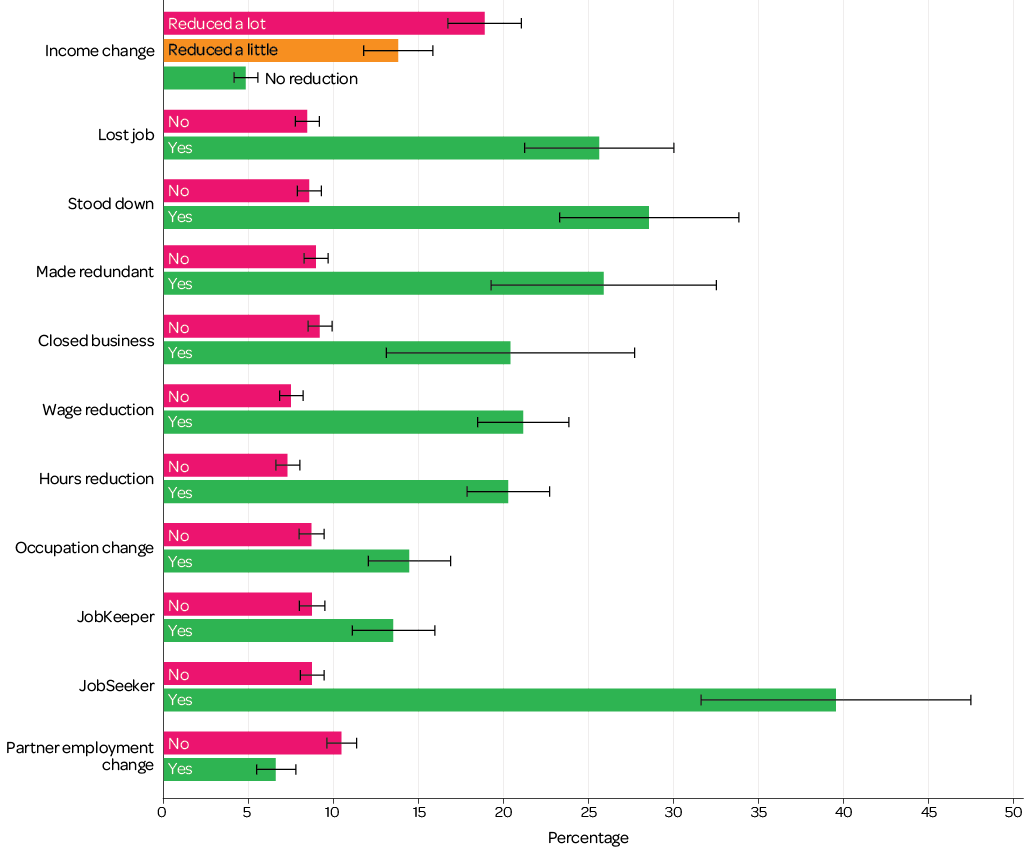

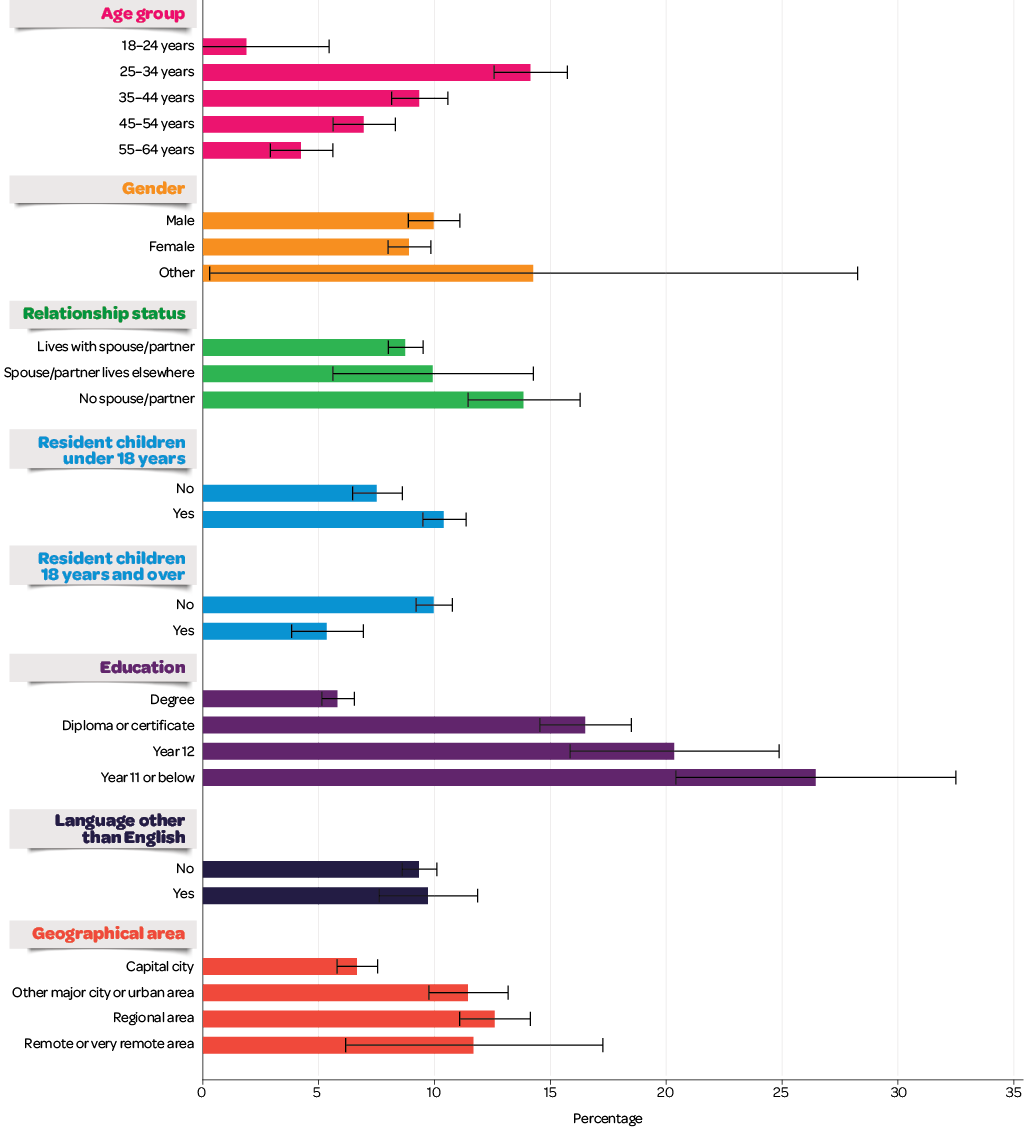

Multivariate analysis was used to explore what characteristics were related to the likelihood of having accessed superannuation early. See Figure 4 for the findings presented as predicted probabilities against the employment and income-related characteristics, and Figure 5 for the predicted probabilities against the demographic characteristics.7

In summary, after controlling for income and employment changes and demographic characteristics, the likelihood of accessing superannuation under the early release program was:

Higher among those:

- whose income, or that of their partner, had been reduced substantially

- who had experienced changes to their employment (i.e. lost their job, been stood down, made redundant, changed jobs, or had a reduction in work hours or salary)

- whose spouse or partner experienced a change to their employment

- receiving JobSeeker or JobKeeper allowance

- aged 25-34 years, compared to those aged 18-24 and those aged 35 and over

- who did not have a spouse or partner, compared to those who were living with a spouse or partner

- who had resident children under the age of 18, compared to those who did not.

Lower among those:

- who had resident children 18 or older, compared to those who did not

- with a degree qualification, compared to those who did not

- living in major cities, compared to those living in other urban areas and regional areas.

These findings are broadly consistent with the broader literature on the financial wellbeing of Australian households. For example, data from the Melbourne Institute's Taking the Pulse of the Nation (TTPN) Survey (Melbourne Institute, 2020) showed that, compared to those aged 65 and over, younger people were more likely to have experienced elevated levels of financial stress in the early months of the COVID crisis; and research examining pre-COVID levels of financial stress showed excess levels of financial stress among single-parent households and households with dependants (Tsiaplias, 2021).

Figure 4: Predicted probability of having accessed superannuation early according to employment and income-related characteristics

Notes: Based on a logistic regression model including age, gender, relationship status, resident children under 18, resident children 18 and over, education, language other than English, state and region of residence, indicators of receipt of JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments, changes to employment in the previous six months, an indicator of whether a spouse or partner had experienced any changes to their employment and an indicator of whether the data were provided by the respondent or their partner. combined respondent-partner data for participants aged under 65, excluding those who had reached superannuation preservation age and were retired, n = 5,288, Model Pseudo R-squared = 0.1869. 95% confidence interval shown.

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal

Figure 5: Predicted probability of having accessed superannuation early according to demographic characteristics

Notes: Based on a logistic regression model including age, gender, relationship status, resident children under 18, resident children 18 and over, education, language other than English, state and region of residence, indicators of receipt of JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments, changes to employment in the previous six months, an indicator of whether a spouse or partner had experienced any changes to their employment and an indicator of whether the data were provided by the respondent or their partner. combined respondent-partner data for participants aged under 65, excluding those who had reached superannuation preservation age and were retired, n = 5,288, Model Pseudo R-squared = 0.1869. 95%confidence interval shown.

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal

3 Due to the timing of the Families in Australia surveys, with the first survey conducted during the first round of the early release program and the second survey during the second round, the percentage of respondents who reported that they, or another household member, had accessed their superannuation early was considerably higher in the second survey than in the first. The wording of the question was also slightly different between surveys. In the first survey, respondents were asked 'Have you, or has anyone in your household, done any of the following due to financial impacts of COVID-19?' In the second survey, respondents were asked: 'In the last six months, have you, or anyone in your household, done any of the following?' A list of financial actions including applying for early access to superannuation was provided.

4 Note that 4% of couples in households where someone had accessed their superannuation were same-sex couples.

5 One in seven (14.6%) participants who had accessed their superannuation experienced a reduction in both hours and wage or salary.

6 A further 4% were not in paid employment and answered 'prefer not to say' when asked about the reason they were not in paid employment. It is possible that some respondents who accessed superannuation and reported no employment changes were receiving parenting payment, special benefit or farm household allowance, making them eligible to access their superannuation early.

7 Based on a logistic regression model including age, gender, relationship status, resident children under 18, resident children 18 and over, education, language other than English, state and region of residence, indicators of receipt of JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments, changes to employment in the previous six months, an indicator of whether a spouse or partner had experienced any changes to their employment and an indicator of whether the data were provided by the respondent or their partner. Combined respondent-partner data for participants aged under 65, excluding those who had reached superannuation preservation age and were retired, n = 5,288, Model Pseudo R-squared=0.1869.

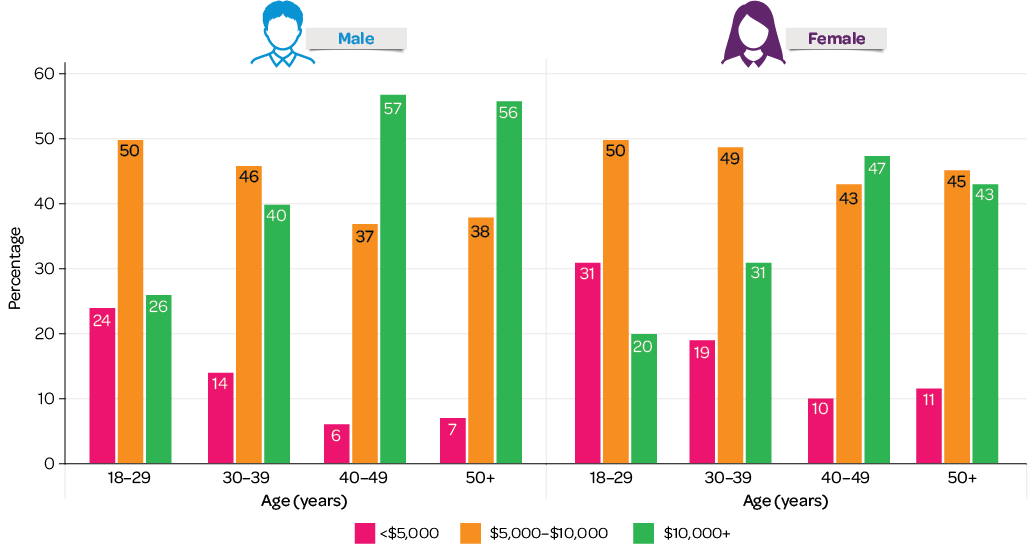

How much superannuation did people draw down?

Estimates from the 2020 Survey of Income and Housing indicate that the average single withdrawal was $7,728 for the first opportunity (April-June 2020), $7,536 for the second (July-December 2020); and the average amount of superannuation withdrawn by those who accessed the early release program twice was $17,441 (ABS, 2021).

Research based on a survey of over 3,000 members of the CBUS Industry superannuation fund who had withdrawn some or all of their superannuation savings during the first phase of the COVID-19 early release program found that respondents were strongly guided, and effectively constrained, by the $10,000 limit - most respondents withdrew either $10,000, or an amount very close to their account balance if their balance was less than $10,000; and while more than 20% of respondents had virtually emptied their accounts, 43% reported they had withdrawn less than 20% of their entire balance (Bateman et al., 2020).

Among Families in Australia participants who had accessed their superannuation, 16% had accessed less than $5,000, 46% drew down between $5,000 and $10,000, and 39% had accessed superannuation in both rounds of the scheme, drawing down more than $10,000. Amounts drawn down increased with age, and were larger for males than for females, presumably reflecting age and gender differences in the amount of superannuation savings available (Figure 6).8

Figure 6: Amount of super accessed, by age and gender

Notes: Estimates based on ordered probit model using information provided by the respondent about their or their partner's early access to superannuation (Partner-respondent combined file, N = 443) controlling for age group, gender and whether the information was provided by the respondent or their partner. When measures of household composition were included in the model, it showed no significant differences in the amounts that individuals drew down according to household, whether they were living with a spouse or partner, or whether they had resident children.

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal

The constraints on the amount available to survey respondents were apparent in their comments in the open-text responses.

I took out $20,000 of my super. It is nearly all gone.

Female, 61 years

Looking back, I would love to have taken more super out - might have meant struggles later but being able to get through things easier might have been less stressful.

Male, 35 years

My wife earns $80k per year, which is good, BUT when I lose a job worth about the same that's a big $80k hole in a family's income. But we didn't qualify for any government help. We were hardly rich before losing my job, now we struggle. I had to take $20k out of my super, and now no money goes into super so retirement is getting worse and worse.

Male, 52 years

The super that was accessed was all that was available. Had more been available, more would have been accessed.

Female, 62 years

8 The causes and impacts of gender differences in superannuation savings are discussed in Warren (2020). Note that although Families in Australia respondents whose partner accessed super were asked about the amount of super their partner drew down, as these data were captured in ranges for the respondent and their partner, it was not possible to calculate the combined amount drawn down for the 78 couples who both accessed their superannuation.

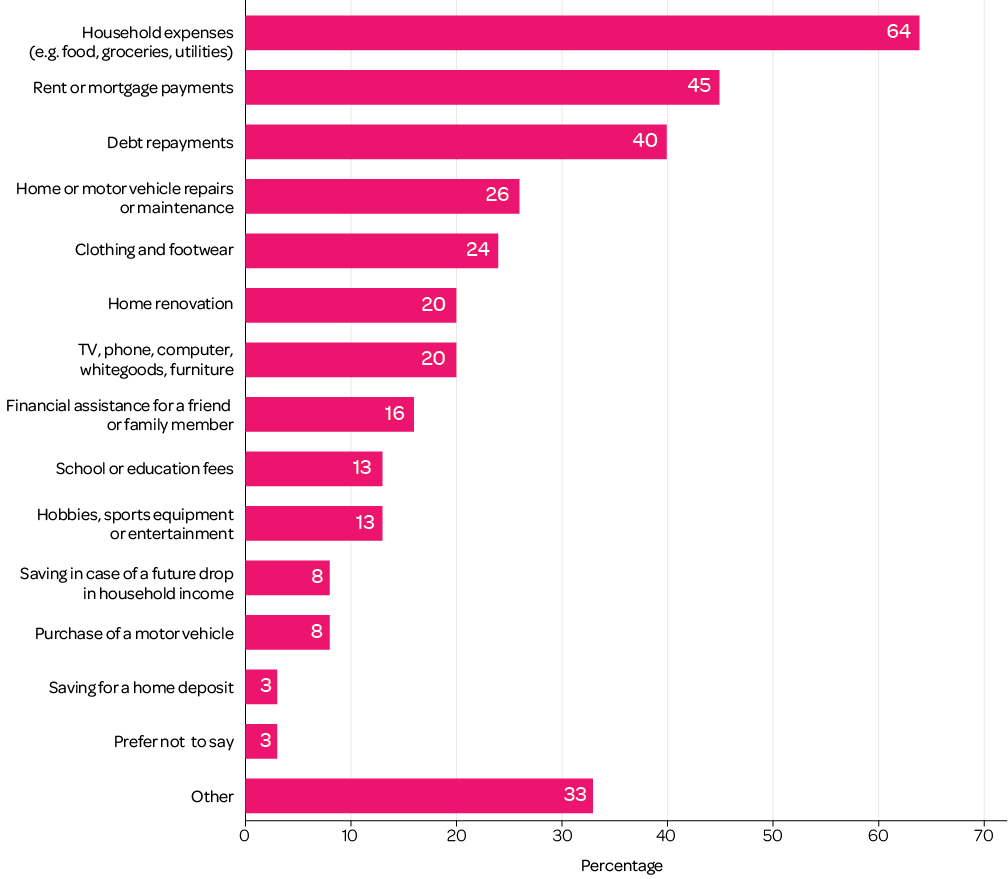

How the money accessed from superannuation was used

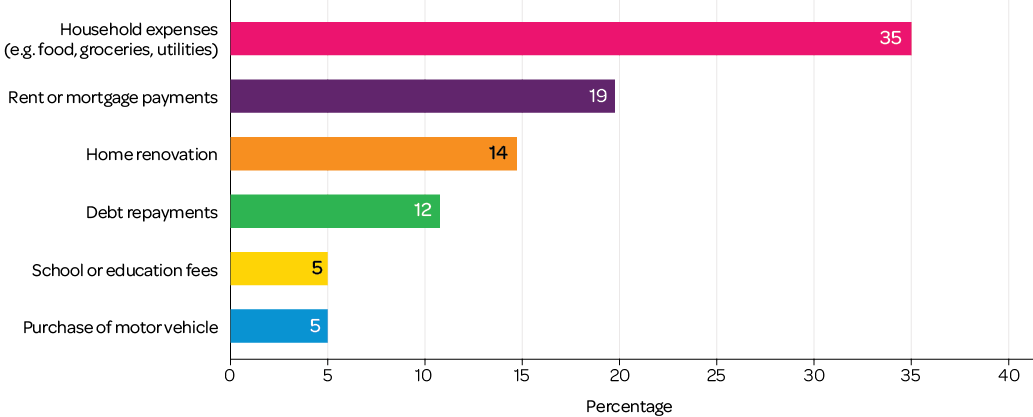

Among Families in Australia respondents in households where someone had accessed their superannuation early, most reported having used the funds to address immediate financial needs. Almost two-thirds (64%) said that at least some of the money had been used for household expenses (Figure 7). The next most commonly reported uses were rent or mortgage repayments (45%) and debt repayments (40%).

Overall, 75% of respondents in households where superannuation was accessed said that at least some of the money was used for the alleviation of financial stress (i.e. household expenses, paying the rent or mortgage, or reducing debt). However, most respondents (84%) reported using the superannuation money for more than one purpose - only 14% said that it was used only for household expenses, rent or mortgage payments or paying off debt.

Figure 7: Uses of funds drawn from superannuation accounts

Notes: Weighted (N = 514, respondents who said that they or someone in their household had accessed their superannuation early). Other items included in the question were: 'withdrew and reinvested to obtain a tax benefit', 'cigarettes, tobacco products or alcohol' and 'gambling - online or offline'. These have been included in the 'Other' category, as the number of responses was too small for reliable estimates.

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal

Almost one in four said that some of the money had been used for clothing and footwear, one in five reported spending the money on a TV, phone, whitegoods or furniture and 13% said that at least some of the money had been used for hobbies, sports equipment or entertainment.

Around one in five respondents (21%) who had accessed their superannuation said that the funds had been used for other purposes than those listed in Figure 7. The most commonly reported other purposes were medical expenses, legal fees and starting a new business.

Not covering costs as I started a new business on 1st of April (day COVID-19 lockdown 1 started) and had to use super, etc. to cover shop rent and mortgage costs as I was not entitled to JobKeeper. As a small business I was, and still am, living week for week.

Female, 50 years

I separated and moved into temporary accommodation until I could find permanent housing in my hometown. I withdrew my super to help pay for the relocation costs and to purchase furniture and whitegoods. We left most things at the family home when we left.

Female, 34 years

Seriously distressing and scary - a massive source of anxiety for me. No one would lease me a house without substantial savings in a bank account due to me not being in full-time employment and on Jobseeker. I had to pay bond and I had to pay removalists. The rest of my super was used very closely behind that for my household expenses, textbooks, clothing, etc. for the kids for school and some very unexpected car repairs. I am now just about at the end due to needing the money over the last months to help me pay rent as well since Jobseeker was reduced.

Female 49 years

Sole provider husband made redundant due to COVID in June. I accessed super to pay for pregnancy and baby-related items. To take care of toddler expenses and preparing for new baby.

Female, 35 years

We took a massive hit financially after losing our home and almost everything in it ... then COVID hit and made things 10 times worse!! Accessing my super early was the only way we could stay afloat during that time.

Female, 32 years

How the money accessed from superannuation was used will depend strongly on the financial situation and the needs of the respondent and their family. That is, their family's income and expenses, and their levels of savings and debts. We note that in accounts of how the superannuation money was used, the family perspective comes through, with couple respondents, in particular, referring to joint decisions or joint financial experiences. Some even referred to the contributions of their children in helping to support family financial wellbeing through them accessing superannuation early.

Even though I am separated from the girls' father, we still share the same accounts and funds - he lost 25% of his salary for six months, we put our mortgage payments on hold for six months and then he has taken money from his super to travel to the UK for his sick father and then to be able to pay the quarantine bill on his return.

Female, 49 years

I have ended up supporting my kids again - I am fortunate to have a good salary. My kids have also accessed super early payments to help.

Female, 54 years

Access to super allowed us to buy our own home - what we believe is a good investment.

Female, 37 years

It is extremely stressful financially. We paid off all debt except one using super and were so pleased.

Female, 46 years

We are only starting to breathe now that we have accessed our super. The debts we had were starting to drown us as we have a limited income due to maternity leave, reduction of work hours. We battled with taking the money out of super, but I made spreadsheets of the debt we had and the interest and it was more financially viable for us to pay off the debt/s and then re-invest money into the super that we would have been paying in credit card interest. Having the flexibility of our income during this tough time (not most of it going to debt repayments) has made it a little less daunting.

Female, 33 years

For each of the possible uses of superannuation funds listed in Figure 6, multivariate analysis was used to determine what characteristics explained the likelihood of spending superannuation money for that purpose.9 For each, after controlling for the range of demographic characteristics, the two strongest predictors of how money accessed from superannuation was used were reported changes in income (of the respondent or their spouse/partner) and housing tenure (whether respondents were renting, paying off a mortgage, or owned their home outright). These differences were:

Changes in income and employment

- Using the money accessed from superannuation for necessities such as household expenses, paying the rent or mortgage, or paying off other debts was significantly more likely among those who reported a large reduction in their or their partner's income. Using superannuation money for car or home maintenance was also more common among those who reported a large reduction in income than those who did not.

- After controlling for reported changes in income and other demographic characteristics, using money accessed from superannuation to pay the rent or mortgage was most common among single people who had experienced a change in their employment arrangements (such as losing their job, being stood down, or having their work hours reduced). On the other hand, using the money for hobbies, sporting equipment or entertainment was most common among single people whose employment arrangements had not changed.

- After controlling for reported reduction in income, there were very few significant associations between reported income at the time of the second survey and how money drawn down from superannuation was used.10 Spending on clothing and footwear was less common among higher-income respondents ($3,000 or more per week); and paying off debts was more common among respondents with (couple-combined) incomes less than $1,000 per week.11

Housing tenure

- Use of superannuation for paying the rent or mortgage was more common among renters, than those paying off a mortgage. This may reflect difficulties experienced by some renters in negotiating rent relief from landlords or agents.12

- Compared to respondents who were paying off a mortgage, use of superannuation funds to pay for household expenses or purchase a motor vehicle was more common among renters, while using funds to purchase furniture or appliances or saving the money in case of a future drop in income was less common among renters.

- Using money accessed from superannuation to provide financial assistance to others was more common among those who owned their home outright, than renters and those who were paying off a mortgage.

- Among respondents who owned their home outright or were paying off a mortgage, use of superannuation funds for home renovations was less common among those with resident children aged 18 or older, and more common among those who did not complete Year 12, compared to those with a degree.

Some uses of superannuation money, such as school or education expenses and providing financial assistance to others, were related to demographic characteristics such as age and household composition:

- The use of superannuation funds for rent, mortgage payments or paying off debts was more common among respondents aged under 30 than those 30 or over; and spending on appliances or furniture (TV, phone, whitegoods, computer, furniture) was less common among those under 30. Spending on school or education fees was most common among respondents aged 40-49, while saving money for the future and spending on hobbies, sports equipment or entertainment was less common among respondents aged 50 or older than those under 50.

- By household composition, reports of using the money for home or car repairs were more common among those with a spouse or partner who did not live with them, compared to those living with a spouse or partner.

- Reports of using money drawn down from superannuation for school or education fees, helping others financially, or saving in case of a future drop in income was more common among respondents who spoke a language other than English, compared to those who spoke English only.

- Compared to respondents who had a degree qualification, using money accessed from superannuation for school or education fees was more common among those with a Year 12 qualification; and using the money for debt repayment was more common among those who did not have a degree qualification.

- Using the money for rent or mortgage payments was less common among those in regional areas, compared to capital cities; while the use of superannuation to pay for household expenses or school or education expenses was less common among respondents who lived in capital cities and regional or remote areas, compared to those in other major cities or urban areas.

Main use of money accessed from superannuation

Most respondents (84%) in households where someone had accessed superannuation said that the money had been used for more than one purpose. When asked about the main purpose the money was used for, the majority (66%) reported having mainly used the money for the alleviation of financial stress (e.g. for household expenses, paying the rent or mortgage, or debt repayments) (Figure 8). However, one in seven respondents (14%) said that the superannuation funds were mainly used for a home renovation.13

Figure 8: Main use of funds drawn from superannuation accounts

Note: Weighted (n = 514, respondents who said that they or someone in their household had accessed their superannuation early).

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal

I withdrew money from super when my business needed to go on hold, also because I was part way through renovations on a small apartment in Brisbane that I couldn't finish because of lockdowns, so I've been without rent from it all year. I'm hoping I can finish by about Christmas and rent it out in 2021, which will make life much easier.

Female, 56 years

We withdrew on my super to pay an unachievable credit card off in full. Besides our mortgage it was our only debt and we weren't able to shift it so now we do not use it and are saving money for the first time in years.

Female, 30 years

Became relatively debt free because of super withdrawal, but at the same time higher unemployment makes it hard to find a good casual job to fit around caring roles.

Male, 32 years

Sold an investment property to ensure we had liquidity during this time. Super was spent on fixing it up before sale.

Female, 34 years

9 Based on logistic regressions of the subsample who reported that they or another household member had accessed superannuation (n = 514). Controlling for age group, gender, relationship status, resident children under 18, resident children aged 18 or older, education, housing tenure, state and region of residence, whether a language other than English is spoken at home and reported changes in income. For home renovations, the sample is restricted to those who owned their home outright or were paying off a mortgage. For rent or mortgage payments, the sample excludes those who own their home outright. There were no statistically significant associations between using superannuation for clothing and footwear and the characteristics included in the model.

10 For some respondents in households where superannuation was accessed, income at the time of the second survey may not reflect their financial situation at the time they made the decision to draw down superannuation funds. With rates of unemployment and underemployment close to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2020, many of those who experienced an income reduction due to a job loss or reduction in working hours are likely to have returned to their pre-pandemic income levels by time these data were collected.

11 Based on couple-combined income if respondents are living with a spouse or partner.

12 A survey of 15,000 renters in Australia, with data collected during July and August 2020, found that while the majority of requests for a rent alteration were met with either a rent reduction or deferment, 36% of respondents said that either the landlord would not negotiate or that they have not yet received a response from their landlord (Baker, Bentley, Beer, & Daniel, 2020).

13 It is possible that, for some of these respondents, this decision was related to the Federal Government's home builder grant scheme, which provided eligible owner-occupiers (including first home buyers) with a grant to assist with the cost of building a new home or substantially renovating an existing home (Treasury, 2020b). While some banks see having drawn down superannuation funds as a sign of financial distress and may be less likely to approve a loan where the deposit comes mainly from superannuation funds (Derwin, 2020), this may be less of an issue for home renovations, as a renovation loan will be smaller in value than a home loan, and borrowers seeking a loan for a home renovation are likely to already have some equity in their property.

Other financial actions taken

Respondents were asked if they, or someone in their household, had taken any action in response to the financial impact of COVID-19. See Figure 9 for the full list of actions. Among respondents in households in which someone had accessed superannuation, almost all (95%) had also taken other actions due to financial stress, compared to 64% of respondents in households where no-one had accessed superannuation early (Figure 9). This suggests that the majority of those who accessed their superannuation early were in genuine financial difficulty at the time they made the decision to draw down their superannuation. This is consistent with the open-text responses, with quotes presented elsewhere in the report illustrative of the degree of financial hardship experienced in many families.

Figure 9: Financial actions taken in the past six months, by whether superannuation had been accessed

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal, weighted, n = 3,743

Cutting spending on essential and non-essential items and using money that had been saved for other purposes to pay for everyday expenses were the most common actions taken, with the likelihood of having taken these actions significantly higher if a household member had drawn down their superannuation, compared to those in households where no-one had accessed their superannuation. In households where superannuation had been drawn down, arranging a payment plan for utilities and asking for financial help from friends or family was also much more common than for those in households where super had not been accessed.

Concerns about financial wellbeing

While accessing superannuation funds early provided financial relief to many Australians; for some, the long-term impact on retirement savings may mean the difference between a comfortable lifestyle in retirement and relying on the age pension. Analysis undertaken by the Australian Treasury as part of the 2020 Retirement Income Review showed that a person withdrawing $10,000 in two consecutive years from age 30 would lower their superannuation at retirement by $40,300, and for a 55 year old, their superannuation balance at retirement would be $24,600 lower (Treasury, 2020c).14

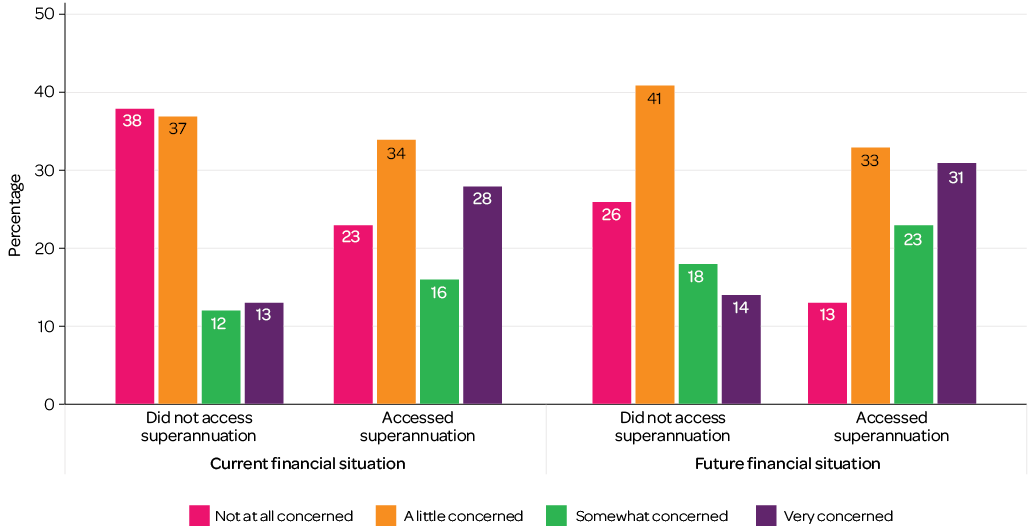

Data from the Families in Australia survey show that respondents' levels of concern about their family's current and future financial situations were higher among respondents in households where someone had accessed superannuation. Among those in households in which someone had accessed their superannuation, 28% said they were very concerned about their current financial situation, and 31% said they were very concerned about their family's future financial situation (Figure 10). Open-text responses show that, for some respondents, while early access to super had helped them address their immediate financial needs, there were concerns about the future, particularly related to the impact of reducing their superannuation balance on their income when they retire.

Figure 10: Concerns about family's financial situation

Note: Accessed superannuation refers to access by any household member.

Source: Families in Australia Survey: Towards COVID Normal, weighted. n = 3,667 (current), 3,646 (future)

It has been a financially difficult year. Early access to super, helped keep us afloat when I had lost a job due to COVID, and there was no guarantee of finding new employment. I was very thankful after some months to find a higher paying job, and I have now been able to assist not only myself but members of my immediate and extended family and friends through COVID, this has been through a combination of lowering my accommodation costs, cutting back on spending and a higher income. I am unsure of what direction to take next financially, myself and the majority of my family members are in insecure, low-paying employment.

Female, 54 years

Loss of employment hours as self-employed. Unable to travel across the state and interstate to complete work type. Requiring access to super has impacted on retirement funds, pause on mortgage. There have been many impacts on financial wellbeing this year.

Female, 47 years

Due to COVID we have had to draw down on our superannuation, which results in us having much less finances to be able to retire on.

Male, 54 years

Husband had to access super for financial reasons so less money will be available at retirement.

Female, 47 years

When I was stood down whilst pregnant we were very concerned for the future year; however, the JobKeeper and super access put us back into a better financial situation and we are very stable.

Female, 34 years

14 Values are in 2018-19 dollars, deflated by average weekly earnings (Treasury, 2020c). Analysis by Industry Super Australia (2020), based on different assumptions concerning future levels of inflation and fund returns showed that a 25 year old who accessed the full $20,000 available under the scheme could lose more than $95,000 from their retirement balance, a 30 year old would lose $80,000 and, for a 40 year old, their superannuation savings at retirement would be $54,000 lower.

Summary

As a result of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment and work hours, many Australians found themselves in a financial situation they had never experienced before. The early release of superannuation program, part of the government's financial response to COVID, aimed to assist those experiencing financial hardship. Analysis of data from the Families in Australia Survey show in families where someone had drawn down their superannuation, the money was mainly used to assist with their everyday household expenses, paying the rent or mortgage and for repaying debts, as was intended when the program was introduced.

There was variation in access to superannuation, the amount accessed and the subsequent use of these funds by a range of demographic, employment and income-related characteristics. Some differences were likely reflecting differences in superannuation balances to start with (by age and by gender, for example). Not surprisingly, in accordance with eligibility criteria, the survey found that those who had accessed their superannuation included a high proportion that had experienced changes in work hours or income.

The findings highlight the role that early access to superannuation had in supporting families, and not just individuals, with many of those who accessed their superannuation being from couple families or families with children. While in most households, superannuation was only accessed by one person, around one in six survey respondents in households where superannuation was accessed said that both they and their spouse or partner had accessed superannuation early.

Respondents in households where someone had accessed their superannuation early were more likely also to report having taken other actions in response to the financial impact of COVID, such as cutting down on essential and non-essential spending, arranging payment plans for utilities, and asking for financial assistance from friends or family. This further supports the conclusion that the majority of those who accessed their superannuation did so because of an immediate need, rather than for the purposes of non-discretionary spending or for precautionary saving.

Reports of concern about their family's current and future financial wellbeing were higher among respondents in households where someone had accessed their superannuation. For some, the concerns about the future were related to the impact that drawing down superannuation had on their retirement savings and their future retirement income.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2020). Household financial resources: Preliminary estimates of household income, wealth and housing costs by various characteristics from the Survey of Income and Housing. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Labour Force, Australia, Catalogue No. 6202.0. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/latest-release#key-statistics

- Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). (2021). COVID-19 Early Release Scheme - Issue 36,. Sydney: APRA. Retrieved from www.apra.gov.au/covid-19-early-release-scheme-issue-36

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO). (2021a). COVID-19 early release of super interim report: 2019-20 applications. Canberra: ATO.

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO). (2021b). COVID-19 early release of super - integrity and compliance. Canberra: ATO.

- Baker, E., Bentley, R., Beer, A., & Daniel, L. (2020). Renting in the time of COVID-19: Understanding the impacts (AHURI Final Report No. 340). Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. Retrieved from www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/340

- Bateman, H., Campo, R., Constable, D., Dobrescu, I., Goodwin, A., Liu, J. et al. (2020). 20K now or 50K later? What's driving people's decision to withdraw their super? Sydney: ARC Centre for Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR), UNSW Business School.

- Carroll, M., Budinski, M., Warren, D., Baxter, J., & Harvey, J. (2021). Towards COVID Normal report 1: Connection to family, friends and community. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Derwin, J, (2020, 26 June). Early super withdrawals are being used to get onto the property ladder. Australian Financial Review.

- Industry Super Australia. (2020). Accessing super early should be a last resort for financially stressed members. Melbourne: Industry Super Australia. Retrieved from www.industrysuper.com/assets/FileDownloadCTA/200323-Accessing-super-should-be-a-last-resort-v3.pdf

- Kolenikov, S. (2014). Calibrating survey data using iterative proportional fitting (raking). Stata Journal, 14(1), 22-59.

- Melbourne Institute. (2020). Taking the Pulse of the Nation: Three in ten Australians financially stressed over impact of COVID-19 (Research Insights). Melbourne: Melbourne Institute. Retrieved from melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/3358132/Taking-the-Pulse-of-the-Nation-20-23-Apr.pdf

- Qu, L. (2020). Families then and now: Households and families (Research Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- The Treasury. (2020a). Economic response to the Coronavirus: Early access to superannuation. Canberra: The Treasury.

- The Treasury. (2020b). Economic response to the Coronavirus: Homebuilder. Canberra: The Treasury.

- The Treasury. (2020c). Retirement income review, final report, July 2020. Canberra: The Treasury.

- Tsiaplias, S. (2021). The welfare implications of unobserved heterogeneity. Review of Income and Wealth, forthcoming. doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12499

- Warren, D. (2020). Families then and now: Income and wealth. (Research Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

About the survey

Towards COVID Normal was the second survey in the Families in Australia Survey (AIFS' flagship survey series). It ran from 19 November to 23 December 2020, when restrictions had been eased in most states.

The pandemic in Australia triggered an unprecedented set of government responses, including the closing of Australia's borders to non-residents, and restrictions on movement, gatherings and 'non-essential' services.

Although the health consequences over the period were not as severe in Australia as they were in many countries, social and economic effects were profound. The Towards COVID Normal survey attempted to capture some of those effects. The survey was promoted through the media, social media, newsletters, internet advertising and word of mouth.

Survey participants

In the first survey, there were 7,306 respondents, of which 6,435 completed all survey questions. There were 4,843 couple respondents.

In the second survey, 4,866 participants responded, of which 3,627 completed all survey questions. There were 2,610 couple respondents.

Author: Diana Warren

External reviewer: Sarantis Tsiaplias

Editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

Featured image: © GettyImages/staticnak1983

Warren, D. (2021). Towards COVID normal: The early release of superannuation, through a family lens. (Families in Australia Survey report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-76016-239-9