Towards COVID normal: Impacts on pregnancy and fertility intentions

Families in Australia Survey report

July 2021

Download Research report

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused great damage to economies and social lives around the globe. Many people have lost their jobs and even more have experienced financial difficulties. Parents have juggled working from home while looking after and home-schooling their children. For some people, the pandemic may have also reshaped their views about having their first or an additional child, thereby leaving an indelible mark on the shape of a nation's future population.

In the first and second waves of COVID-19, as the health sector was focused on treating those infected and stopping the spread, the experience of those who were expecting newborns was inevitably affected. This report examines the impacts of COVID-19 on the pregnancy and fertility decisions of those who were trying to have children before the pandemic and women who were currently expecting a child. It also looks at women's future intentions for having children.

Key messages

-

Over one in 10 women reported that they and their partner had been trying for a first or additional child before the pandemic. However, 18% of these women ceased trying to conceive at least partly because of the pandemic.

-

For those who stopped trying to conceive at least partly owing to the pandemic, concerns about their current and future financial situation had contributed to their decision.

-

A small proportion of women were pregnant at the time of survey, with 22% of these women indicating that COVID-19 had 'very much' or 'somewhat' affected the timing of their current pregnancy:

- Some indicated that they had brought forwarded their plan of having children.

- Some expressed concerns of having children during the pandemic.

- Some reported that their pregnancy was delayed because IVF treatment was suspended during the lockdown.

-

Around one-fifth of women reported that COVID-19 had had an impact on their intentions of having children.

-

Women were more likely to report that COVID-19 had affected the timing of having children than the number of children they would have in the future:

- 14% of women under 40 years of age reported that COVID-19 'has impacted the likely timing of having children', typically delaying the timing.

- 5% reported it had impacted the likely number of children they would have, with almost all indicating fewer children.

Introduction

The Australian Institute of Family Studies conducted the Families in Australia: Towards COVID Normal survey in November-December 2020 (see 'About the survey' for a brief description of the survey and participants). Drawing on the survey data, this report examines the following issues relating to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on women who were of reproductive age and:

- who were planning to have children before the pandemic

- who were currently expecting a child

- their future plans of having children.

Attempting to have children before COVID-19

Female respondents who were living with a partner were asked whether they had been trying to have a child or another child before the pandemic became apparent.1 Respondents who had ceased trying were further asked whether their decision to abandon such attempts was due to the pandemic:

- 12% indicated that they and their partner had been trying for a first or additional child

- two-thirds of these said that they had given this up at the time of survey

- 18% of the women who had tried to conceive before COVID-19 reported that they stopped trying owing to the pandemic, with 6% indicating that their decision was entirely due to the pandemic and 12% indicating that their decision was influenced by the pandemic to some extent.

Of the women who had ceased trying to conceive a child, those who reported that this decision had been influenced by the pandemic were more likely than their counterparts who had stopped trying for other reasons to indicate that they or their partner had experienced reduced work hours or job loss because of the pandemic (62% vs 26%).

Notes: These statistics are based on weighted data. The unweighted sample sizes of the two groups are: influenced by COVID-19, n = 31; not influenced by COVID-19, n = 107. The difference between the two groups regarding the pandemic's employment repercussions was statistically significant (p < .001).

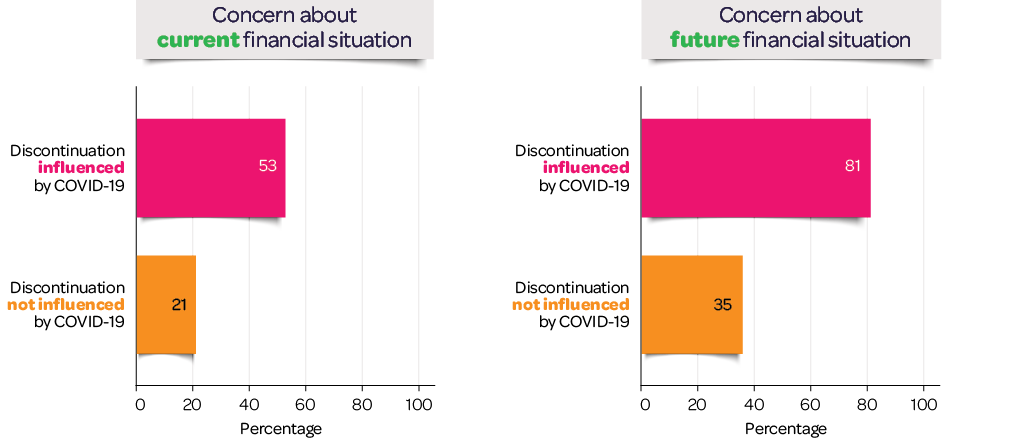

Figure 1 shows the extent to which women who had ceased trying to conceive a child were concerned about their current and future financial circumstances. Patterns of the extent of these financial concerns are shown by whether they said their decision to stop had been influenced by the pandemic.

- Both groups tended to express greater concerns about their future than current financial situation, with this pattern being more marked for women who said that their decision to abandon trying for a baby had been influenced by the pandemic.

- Of women whose decision had been influenced by the pandemic, 53% said that they were somewhat or very concerned about their current financial situation and 81% expressed these levels of concern about their future financial situation.

- Of those whose decision had not been influenced by the pandemic, 21% indicated that they were somewhat or very concerned about their current financial situation, while 35% expressed such concern about their future situation.

- Women whose decision had been influenced by the pandemic were more likely than women who had not been influenced to be very or somewhat concerned about their current financial situation (53% vs 21%) and their future financial situation (81% vs 35%).

Figure 1: Female respondents who had ceased trying to conceive a child: reports of concerns about their current and future financial situation, by whether the pandemic influenced their decision to discontinue attempts to conceive

Notes: The statistics are based on weighted data. The unweighted sample sizes of the two groups are: influenced by COVID, n = 31; not influenced by COVID, n = 107. Statistically significant differences between the two groups emerged for both the extent to which they were concerned about their current financial situation (p < .01) and their future financial situation (p < .001).

1 This question was skipped for those who were currently pregnant.

Current pregnancy

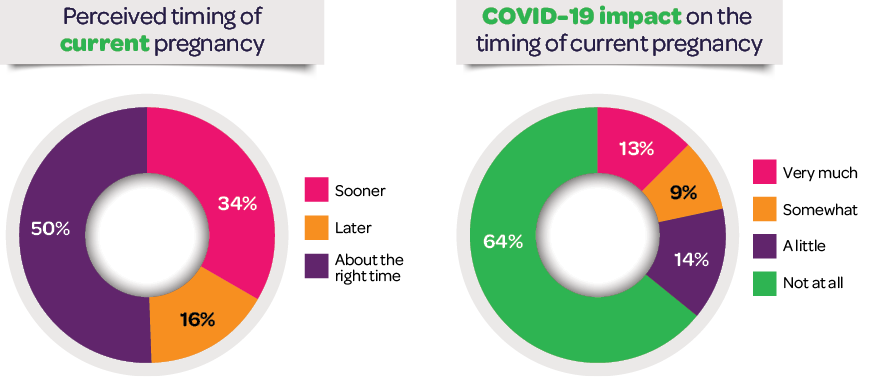

A small number of female respondents were pregnant at the time of the survey (n = 110). They were asked whether their pregnancy had happened sooner or later than they wanted or at about the right time, and whether COVID-19 had affected the timing of their current pregnancy. Responses to these questions are summarised in Figure 2.

- Approximately one-half of the women who were pregnant at the time of the survey indicated that their current pregnancy was at about the right time. One-third (34%) felt that it was sooner, while one in six (16%) indicated that their pregnancy had happened later than they would have preferred.

- A significant minority of the women (36%) indicated that the pandemic had affected the timing of their current pregnancy, with 22% reporting a 'very much'/'somewhat' impact and 14% 'a little' impact.

Figure 2: Female respondents who were currently pregnant: perceived timing of current pregnancy and the impacts of COVID-19 on the timing of pregnancy

Notes: The statistics are based on weighted data. The unweighted sample size, n = 110

Figure 3 further shows that the impact of the pandemic on the timing of the current pregnancy was more apparent for those who reported that their current pregnancy came 'sooner' than for those who reported that their pregnancy came 'later'.

For those who reported their current pregnancy timing was affected by the pandemic:

- at least four in 10 indicated their current pregnancy came sooner (44%) (i.e. 14% of all currently pregnant women)

- less than one-fifth said their current pregnancy was delayed (18%) (i.e. 3% of all currently pregnant women).

Figure 3: Currently pregnant female respondents: the proportion reporting that COVID-19 had 'very much'/'somewhat' affected the current pregnancy timing, by whether the pregnancy came sooner, later or at about the right time

Notes: The statistics are based on weighted data. The unweighted sample sizes: 'Sooner', n = 26; 'Later', n = 33; 'About the right time', n = 47. The differences between the 'Sooner' and 'Later' groups and between the 'Sooner' and 'About the right time' groups were statistically significant based on bivariate logit regression (p < .01).

Female respondents who indicated that COVID-19 had affected the timing of their current pregnancy further explained in what way they were affected by COVID-19.

Of women who felt that the timing of their current pregnancy was sooner than they preferred, some reported that COVID-19 had had a 'positive impact' on their current pregnancy. The reasons included travels being cancelled or other plans, such as a wedding, put on hold and so they decided to have a child/another child, the lockdown enabling more intimate time together.

Longer times together and the decrease of work stress allowed for increased fertility.

30 year old, pregnant with first child

We had to postpone our wedding, so we decided to have a baby instead.

26 year old, pregnant with first child

However, some expressed that their pregnancy had come sooner than they wanted and were especially concerned about uncertainties in the context of COVID-19.

Unsure I wanted to bring any more children into the world after what's been happening with COVID-19.

33 year old, pregnant with later child

Didn't expect to fall pregnant so quickly, made it a little scary as it was when COVID first became an issue.

29 year old, pregnant with later child

Women who indicated that the timing of their current pregnancy was later than they had preferred commonly reported that their IVF treatment was suspended because of the COVID-19 restrictions.

IVF clinics were shut down and our cycle earlier in the year was cancelled.

37 year old, pregnant with first child

IVF was stopped due to COVID.

36 year old, pregnant with later child

Some did not want to have a/another child during the pandemic.

Waited before trying due to COVID restrictions and not wanting to bring a baby into the world with little family support.

28 year old, pregnant with first child

We decided not to try for a baby during COVID and waited months until the COVID peak had passed as we knew we would need care or a grandparent helping us during any pregnancy.

38 year old, pregnant with later child

Future plan of having children

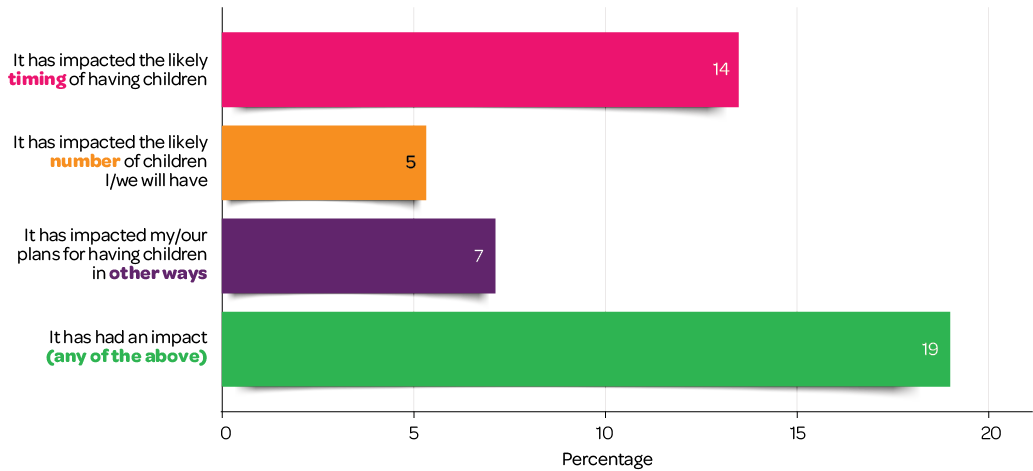

Close to one-fifth of women under 40 years of age reported that COVID-19 had had an impact on their intentions to have a first or additional child (Figure 4). Respondents were more likely to report that the pandemic had had an impact on the timing of having children than on the number of children they would like to have (14% cf. 5%). When female respondents indicated that COVID-19 had had an impact on the likely timing of having children, they mostly meant that they would likely have children later because of the pandemic (92%). Likewise, of women who reported that COVID-19 had had an impact on the likely number of children they would have, almost all said that they would likely have fewer children than they wanted because of the pandemic. A small proportion reported an impact in other ways (but without further elaboration) (7%).

Figure 4: Perceived impact of COVID-19 on plans for having children, by female respondents aged under 40 years

Notes: Weighted data for the statistics. Unweighted sample size, n = 1,449.

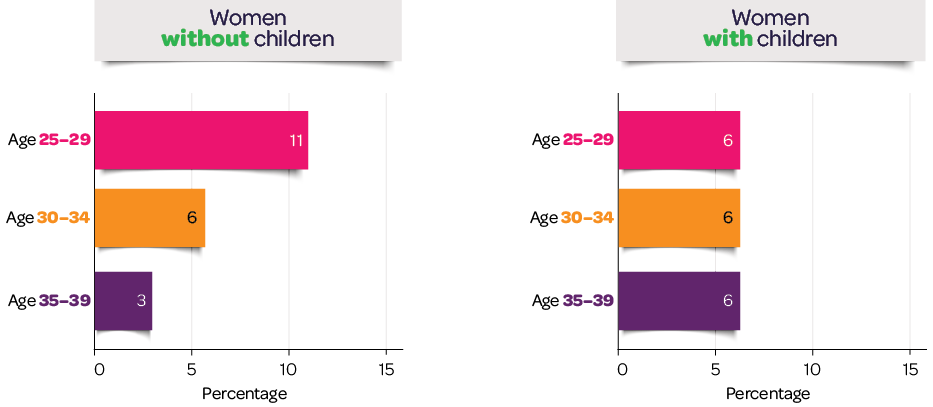

The reports on the impact of COVID-19 on plans/intentions of having children varied with age and whether women already had children. Figure 5 shows the reported impact of COVID-19 on the timing of having children by age (25-29, 30-34 and 35-39 years) and by whether they had children. Figure 6 focuses on the reported impact on the likely number of children they intended to have. (Note that the number of women aged 18-24 years with or without children was too small for reliable estimates and this age group is not reported.)

Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on the timing of having children in the future:

- For women who had no children, the older they were, the less likely they were to report that they would delay having children because of the pandemic. Conversely, the younger women without children were, the more likely they were to report they would delay having children because of the pandemic. These patterns likely reflect the fact that older women could not 'afford' waiting longer because of their age, while younger women felt they still had time and were able to delay having children.

Further analysis revealed that younger childless women were more likely than their older counterparts to have concerns about their current and future financial situation.

- For women with children, reports on the impact of COVID-19 on the timing of having another child in the future did not show any age-related patterns.

Figure 5: Proportions of women who indicated that they would have a/another child later than preferred because of COVID-19, by age and whether they have children

Notes: Weighted data for the statistics. Unweighted sample size: three age groups (25-29, 30-34, 35-39) for women without children, n = 132, 135, & 71 respectively; three age groups (25-29, 30-34, 35-39) for women with children, n = 158, 415, & 478 respectively. For women without children, the difference between the age groups of 25-29 and 35-39 was statistically significant based on weighted bivariate logit regression (p < .05). For women with children, the difference between age groups was not statistically significant based on weighted bivariate logit regression.

In relation to the impact of COVID-19 on the number of children women intended to have in the future (Figure 6), the younger women who had no children were more likely to report they would likely have fewer children as a result of the pandemic. For example, 11% of women without children in their late 20s reported the likelihood of having fewer children because of the pandemic, compared to 3-6% of their counterparts in the two older age groups. On the other hand, of women who had children, the reports on the likelihood of having fewer children were similar across the age groups.

Regardless of age and whether they already have children or not, women were much more likely to report that they would postpone having children than that they would have fewer children because of COVID-19.

Figure 6: Proportions of women who reported they would likely have fewer children because of COVID-19, by age and whether they have children

Notes: Weighted data for the statistics. Unweighted sample size: three age groups (25-29, 30-34, 35-39) for women without children, n = 132, 138, & 75 respectively; three age groups (25-29, 30-34, 35-39) for women with children, n = 160, 482, & 485 respectively. For women without children, the difference between the age groups of 25-29 and 35-39 was statistically significant based on weighted bivariate logit regression (p < .05). For women with children, the differences across age groups were not statistically significant.

Women who indicated that they would likely have fewer children further elaborated why they felt this way.

Some expressed concerns related to current financial difficulties and an uncertain future due to the loss of employment or reduced work hours. The pandemic also led to doubt and pessimism about the world not being a good place to bring up children. Some felt that they would likely have fewer children than they preferred because of the uncertainties caused by the pandemic; for example, access to health care, health implications of COVID-19 for mothers and babies, and running out of time to have children when the pandemic ended.

Financial concerns and job insecurity

Due to COVID my workplace has reduced hours indefinitely. Subsequently I'm working two part-time jobs to make ends meet. This is not viable long term with more children … so we likely will not have enough money to have a third child. My husband is even having second thoughts about a second child.

31 year old, has children

Before COVID-19 we were in a better financial position. Since the pandemic has hit, my husband has lost his job and we have both been struggling with mental health issues, including extra exhaustion on top of the exhaustion of a one year old. Now I'm hoping to go back to work, so I'm not sure if I'll be wanting or able to have another child by the time I find work and get settled.

39 year old, has children

Concerns that the world is not a good place for children

The uncertainty of the world you're bringing children into, and uncertainty around hospital care made us apprehensive to try especially during the Victorian shutdown.

37 year old, no children

It definitely ignites some fear about the world you would be bringing your child into.

25 year old, no children

Other concerns such as medical care and age

Due to my age, this will likely mean I will have fewer children as a result of COVID.

37 year old, no children

We have put off trying for another baby during the pandemic because of the challenges of needing medical care if the pandemic here worsens. Also the longer-term impacts for children/babies who experience this is known. This will likely mean we only have time for one more child rather than another two as we had planned.

34 year old, has children

We were genuinely planning on having another child this year. Before COVID we were considering having two more but now I'm uncertain if we'll even have the second one.

30 year old, has children

About the survey

Towards COVID Normal was the second survey in the Families in Australia Survey (AIFS' flagship survey series). It ran from 19 November to 23 December 2020, when restrictions had been eased in most states.

The pandemic in Australia triggered an unprecedented set of government responses, including the closing of Australia's borders to non-residents, and restrictions on movement, gatherings and 'non-essential' services.

Although the health consequences over the period were not as severe in Australia as they were in many countries, social and economic effects were profound. The Towards COVID Normal survey attempted to capture some of those effects. The survey was promoted through the media, social media, newsletters, internet advertising and word of mouth.

Survey participants

In total, 3,730 people participated, 86% of whom were women. People aged under 25 years and 55 years or older were under-represented (1% and 11% respectively, compared to 12% and 35% in the 2016 Census).

In the analysis, data weights were generated to adjust the sample's differential representation of age, gender and other demographic characteristics. The analysis is based on weighted data.

The present analysis focuses on the subsample of women and men who were asked to answer the survey's set of fertility questions - that is, women under 45 years of age and men under 55 years of age. Owing to small sample sizes for men on various issues and for the sake of simplicity, this analysis focused exclusively on the female respondents.

Author: Lixia Qu

Editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

Featured image: © GettyImages/pabst_ell

Qu, L. (2021). Towards COVID normal: Impacts on pregnancy and fertility intentions. (Families in Australia Survey report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.