Geographical isolation: Factors, dynamics and effects of isolation for older people

February 2024

Download Research snapshot

What is geographical isolation?

Connection to community and services is important to supporting the wellbeing of older people. Geographical isolation can mean that maintaining this connection is challenging. Geographical isolation is characterised by logistical and practical barriers to an older person's connection to and participation in the community.

Geographical isolation can be experienced by people in locations other than regional and rural settings who can experience the following:

- financial barriers

- transportation barriers

- technological barriers

- cultural and linguistic barriers

- cognitive or other impairments.

Geographical isolation can also affect older people's access to health services, social and community services, financial services and legal and dispute resolution services.

Sources: Adorno et al., 2018; Brooke et al., 2022; Byrne & Ghaiumy Anaraky 2022; Commissioner for Senior Victorians, 2020; Herro et al., 2021; Holaday et al., 2022; Hunter & De Simone, 2009; Lamanna et al., 2020; Law Council of Australia, 2017; Levasseur et al., 2020; Pekmezaris et al., 2013; Vine et al., 2014; West & Ramcharan, 2019.

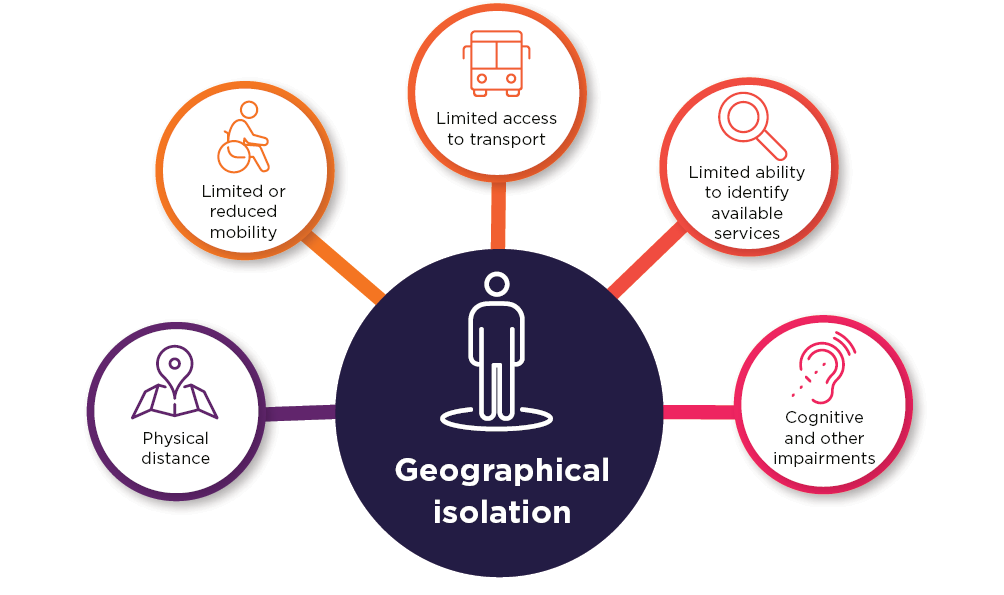

What factors give rise to geographical isolation?

Geographical isolation can arise from a range of factors and these include:

Sources: Adorno et al., 2018; Commissioner for Senior Victorians, 2020; Lamanna et al., 2020; Levasseur et al., 2020; Parsons et al., 2021; Winterton et al., 2014

How is geographical isolation experienced by older people?

A lack of access to local opportunities

A lack of local opportunities is a factor in experiences of loneliness and social disconnectedness. In a recent study of Victorian people aged 60 years and over (n = 4,726) 36% of respondents reported a lack of local opportunities to engage in their community (Commissioner for Senior Victorians, 2020). Additionally, 35% of respondents reported a lack of information on what was available to them in their local community. Barriers are further amplified for those who live in rural and remote locations (Community Legal Centres Queensland Inc, 2019; Hunter & De Simone, 2019; Law Council of Australia, 2017) where self-efficacy, legal, residential and aged-care outcomes can also be affected.

A lack of services available for older people in regional and remote New South Wales was highlighted by some of the service providers interviewed. One participant observed that the closure of many banks across the state in smaller centres contributed to experiences of disconnection from the community. Echoing this finding, one service provider explained:

So, in the last year and a half, there's been a number of closures of very small facilities around New South Wales, and I'm sure it's across the whole country, and it impacts the regional people more than any others because in a built-up urban area, there's probably another nursing home in the next suburb. In a small town, the next closest bed available could be an hour and a half away … the older person becomes isolated from their families because they own farms or businesses in the small town. So that has been a major impact on isolation for older people just from our observations. (P06_P4, community sector, regional)

A lack of access to supports and services affects an older person's self-efficacy, their physical and mental health and their financial wellbeing because they are unable to access legal remedies, address their health or financial issues, or secure appropriate residential aged care outcomes (Inder et al., 2012; Longman, et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2021; West & Ramcharan, 2019).

Gendered dynamics of geographical isolation

Recent data indicates that older people experience lower inclusion scores than the national average (Australian Digital Inclusion Index, 2023). Technology can help to lessen the prevalence of geographical isolation but there is a need for age-friendly technology participation (Berg et al., 2017; Winterton, 2016). Additionally, not all older people have access to technology. Some service providers interviewed said it was important to take flexible approaches to supporting their clients. Access to and confidence in using technology (e.g. the ability to order groceries online) became particularly important in the COVID-19 context, as noted by some service providers:

[COVID-19] was hard because we couldn't get into the hospital to assist people, which meant that we had to move to an online service. And I think that made it really hard for older people … if their hearing's not great the fact that they then weren't coming into the hospital for their normal appointments meant that they weren't accessing services like ours like they normally would ... our older clients didn't have access to computers, so we're very reliant on social workers to help with that if they were visiting all the people in the community. (P04, not-for-profit community sector, metropolitan)

At the same time, some service providers observed that access to support for online engagement was important for older people who did have the resources to engage in this mode by themselves:

During COVID, we did a lot of Zoom groups trivia sessions, and we also did Zumba sessions. We did them via Zoom so that engaged a lot of the clients who were feeling isolated. (P03_P2_ community sector, metropolitan)

Service providers took flexible approaches during COVID-19 restrictions to help connect older people with supports both through technology, if this was accessible to them, as well as in other ways (e.g. through facilitating shopping trips).

Consistent with these findings, previous research has indicated that experiences of geographical isolation were exacerbated during COVID-19 restrictions, which led to service innovation such as virtual platforms and remote service provisions. However, it is important to acknowledge that while virtual platforms can be supportive, there were limitations, with in-person engagement required in contexts (Brooke et al., 2022; Holaday et al., 2022).

How do service providers identify georgraphical isolation and support access to services?

Identifying geographically isolated older people can be challenging given the many practical barriers this group faces with connecting with the community. Some service providers mentioned the key screening tools they used to identify if an older person is geographically isolated; for example, the Modified Monash Model scale through the My Aged Care platform:

We've got a Modified Monash Model scale on My Aged Care. [The scale] consider[s] anybody living in MMM [Modified Monash Model Scale] 6 to be isolated … we see clients in MMM5, which will be considered rural and regional … we cover a huge part of [regional and rural] New South Wales. (P01, public sector, rural)

Other service providers reflected on the less formal ways they can identify isolated older people through their engagement in the community and connections with health care services:

I think we've all got our connections and our local areas that might feedback into us. So ACAT [Aged Care Assessment Team], hospital, social workers in different environments. So, we've built those networks that they're coming to us with that information about someone that's vulnerable and isolated. (P06_P4, community sector, regional)

Summary

- Geographical isolation can have many negative effects on the health and wellbeing of older people.

- Older people living in regional and rural locations can face challenges in relation to accessing services, supports and connections in their community.

- Geographical isolation has the potential to compound experiences of social isolation.

- The data indicate the need for policy to address the physical, social and mental health impacts and the underlying factors giving rise to isolation.

About this study

Seniors Rights Service commissioned the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) to undertake an exploratory, qualitative study to examine the factors, dynamics and effects of isolation experienced by older people in New South Wales. The study was funded by the New NSW government and based on a desktop review and qualitative interviews with professionals.

This snapshot briefly summarises key findings from the desktop review of Australian and international literature relating to experiences of isolation among older people. It also provides relevant insights from individual and group interviews with 20 professionals who work with older people in a variety of settings.

Access the full report: Factors, dynamics and effects of isolation for older people: an exploratory study.

Get more information about the Senior Rights Service.

References

Adorno, G., Fields, N., Cronley, C., Parekh, R., & Magruder, K. (2018). Ageing in a low-density urban city: Transportation mobility as a social equity issue. Ageing & Society, 38(2), 296-320.

Australian Digital Inclusion Index. (2023). Key findings and next steps. Carlton, Vic: ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society.

Berg, T., Winterton, R., Petersen, M., & Warburton, J. (2017). 'Although we're isolated, we're not really isolated': The value of information and communication technology for older people in rural Australia. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 36(4), 313-317.

Brooke, J., Dunford, S., & Clark, M. (2022). Older adult's longitudinal experiences of household isolation and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Older People Nursing, e12459.

Byrne, K. A., & Ghaiumy Anaraky, R. (2022). Identifying racial and rural disparities of cognitive functioning among older adults: The role of social isolation and social technology use. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences.

Commissioner for Senior Victorians. (2020). Ageing well in a changing world. Melbourne: Commissioner for Senior Victorians.

Community Legal Centres Queensland Inc. (2019). Evidence & analysis of legal need. Brisbane, Qld.: Community Legal Centres Queensland Inc.

Herro, A., Lee, K. Y., Withall, A., Peisah, C., Chappell, L., & Sinclair, C. (2021). Elder mediation services among diverse older adult communities in Australia: Practitioner perspectives on accessibility. Gerontologist, 61(7), 1141-1152.

Holaday, L. W., Oladele, C. R., Miller, S. M., Dueñas, M. I., Roy, B., & Ross, J. S. (2022). Loneliness, sadness, and feelings of social disconnection in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(2), 329-340.

Hunter, R., & De Simone, T. (2009). Women, legal aid and social inclusion. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 44(4), 379-398.

Inder, K. J., Lewin, T. J., & Kelly, B. J. (2012). Factors impacting on the well-being of older residents in rural communities. Perspectives in Public Health, 132(4), 182-191.

Lamanna, M., Klinger, C. A., Liu, A., & Mirza, R. M. (2020). The association between public transportation and social isolation in older adults: A scoping review of the literature. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne du Iieillissement, 39(3), 393-405.

Law Council of Australia. (2017). The Justice Project: Older persons. Consultation paper. Braddon, ACT: Law Council of Australia.

Levasseur, M., Routhier, S., Clapperton, I., Doré, C., & Gallagher, F. (2020). Social participation needs of older adults living in a rural regional county municipality: Toward reducing situations of isolation and vulnerability. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 1-12.

Longman, J., Passey, M., Singer, J., & Morgan, G. (2013). The role of social isolation in frequent and/or avoidable hospitalisation: Rural community-based service providers' perspectives. Australian Health Review: A publication of the Australian Hospital Association, 37(2), 223-231.

Parsons, K., Gaudine, A., & Swab, M. (2021). Experiences of older adults accessing specialized health care services in rural and remote areas: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 19(6), 1328-1343.

Pekmezaris, R., Kozikowski, A., Moise, G., Clement, P., Hirsch, J., Kraut, J. et al. (2013). Aging in suburbia: An assessment of senior needs. Educational Gerontology, 39(5), 355-365.

Vine, D., Buys, L., & Aird, R. (2014). Conceptions of 'community' among older adults living in high-density urban areas: An Australian case study. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 33(2), 1-6.

West, R., & Ramcharan, P. (2019). The emerging role of financial counsellors in supporting older persons in financial hardship and with management of consumer-directed care packages within Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 54(1), 32-51.

Winterton, R. (2016). Organizational responsibility for age-friendly social participation: Views of Australian rural community stakeholders. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 28(4), 261-276.

Winterton, R., Clune, S., Warburton, J., & Martin, J. (2014). Local governance responses to social inclusion for older rural Victorians: building resources, opportunities and capabilities. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 33(3), E8-E12.

Media releases

© GettyImages/Eva-Katalin

Stevens, E., Carson, R., & Wall, L. (2023). Geographical isolation: Factors, dynamics and effects of isolation for older people. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Download Research snapshot

Related publications

Factors, dynamics and effects of isolation for older people…

This report sets out the findings of the Factors, Dynamics and Effects of Isolation for Older People: An Exploratory…

Read more

Factors, dynamics and effects of isolation for older people

This snapshot discusses what factors give rise to isolation and how it is experienced by older people.

Read more

Social isolation: Factors, dynamics and effects of…

This snapshot discusses social isolation for older people being an objective lack of connection and interaction with…

Read more