Client violence towards workers in the child, family and community welfare sector

March 2020

Karen Broadley, Nicole Paterson

Download Policy and practice paper

Overview

This paper explores the prevalence and presentation of client violence towards workers, considering any violent or aggressive behaviour from clients, direct associates of clients, and friends or family members of clients. It compares current research on client violence towards workers to official data reports, and considers why there might be a discrepancy between the two sets of data. It details the effects that client violence has on workers personally and the implications for their practice. Finally, it outlines strategies for improving responses to client violence towards workers, including practical responses that can be implemented at an organisational, educational and policy level.

Key messages

-

Physical violence, threats of violence, verbal abuse and intimidation from clients of child, family and community welfare sector workers are a frequent occurrence according to all studies reviewed.

-

Workers experience psychological effects from client violence, which can lead to diminished quality of care for clients, burnout and high staff turnover.

-

There is a lack of official data reporting on violence from clients. The data that does exist under-represents the scope of the problem identified in studies.

-

Client violence towards workers is often seen as 'part of the job', contributing to a culture of under-reporting.

-

Workers largely remain committed to the profession despite experiences of violence and aggression from clients.

-

More up-to-date Australian primary research, and improved official data collection and reporting, could help inform education, training and organisational support.

Introduction

Research studies have confirmed that workers in the child, family and community welfare sector in Australia, and internationally, can be the target of violence and aggression by clients and their direct associates (Briggs, Broadhurst, & Hawkins, 2004; Broadhurst, White, Fish, Munro, Fletcher, & Lincoln, 2010; Hunt, Goddard, Cooper, Littlechild, & Wild, 2016; Koritsas, Coles, & Boyle, 2008; Stanley & Goddard, 2002). Workers employed in social welfare roles have a range of professional backgrounds, including social work, community work and youth work. They can have clients who struggle with complex and inter-related problems associated with mental illness, alcohol and other drug misuse, disability, relationship and parenting issues, family violence, financial instability and housing instability.

The most recent Australian study looking at the prevalence of violence towards workers is Koritsas and colleagues (2008), which is now over 10 years old. These researchers surveyed 216 social workers1 across Australia to establish the prevalence of six forms of workplace violence. They looked at social workers' experiences of violence from clients and friends/family members of clients, as well as from colleagues or other professionals. However, their overall research focus was on violence towards social workers due to the high degree of client contact in the profession.

Workers in the survey reported experiences of workplace violence from the preceding 12 months. The study found that the proportion of workers who had experienced:

- verbal abuse was approximately 3 in 5 workers

- intimidation was approximately 1 in 2 workers

- property damage or theft was almost 1 in 5 workers

- sexual harassment was approximately 1 in 7 workers

- physical abuse was approximately 1 in 10 workers

- sexual assault was 1 in 100 workers.

Overall, 67% of these workers had experienced at least one form of violence in the past 12 months (Koritsas et al., 2008). More recent international research indicates a continuation of issues with client violence towards workers in this sector. All of these experiences could have implications for the safety and wellbeing of workers in the sector, as well as on their practice with clients.

Client violence can be distinct from other experiences of workplace violence and trauma (e.g. abuse from colleagues, vicarious trauma). While a substantial body of literature exists on issues such as workplace bullying and vicarious trauma in the welfare sector, the authors identified a research gap in how workers experience client violence, particularly in Australia.

This paper investigates what is known about the prevalence and nature of client violence towards workers in the child, family and community welfare sector; and it synthesises the evidence-informed implications for addressing this violence with targeted responses through policy and practice.

While existing literature on client violence tends to focus on statutory child protection workers, this paper will draw on studies relating to client violence2 towards all workers in the sector more broadly. In the context of this paper, the studies specifically refer to adult clients.

Using a systematic search method, supplementary hand searching and recent grey literature, this paper aims to answer four questions:

- What do official statistics tell us about the prevalence and nature of client violence towards workers in the child, family and community welfare sector?

- What does the peer-reviewed literature tell us about the prevalence and nature of the problem?

- What are the similarities and differences between the official statistics and the peer-reviewed literature?

- What are the evidence-informed implications for policy, organisational action and practice?

Note about this paper

This paper does not label all clients as dangerous, or seek to generalise the prevalence of violent behaviour among all social welfare clients. As Tzafrir, Enosh, and Gur (2015, p. 67) point out, 'clients utilise social services when dealing with significant life problems; by definition, such times are demanding of and stressful for the client'. On top of this, the effects of systemic constraints are real and can have devastating consequences for clients. Issues such as eligibility criteria, bureaucratic processes, high service demands, and time-limited funding can all act as barriers to clients getting the help they need, and can contribute to the aggravation of clients under extreme stress. In some instances, aggression may be a client's most effective mechanism for fulfilling their needs, developed as a survival strategy over time. However, failing to acknowledge and appropriately respond to the problem of client violence towards workers can have serious consequences for the workers and, ultimately, their clients.

Importance of understanding the prevalence and nature of client violence towards workers

Experiencing client violence, threats of client violence and verbal aggression from clients is likely to have a harmful effect on workers' personal lives and sense of wellbeing (Hunt et al., 2016; Koritsas et al., 2008; Stanley & Goddard, 2002). Other consequences of client violence are likely to include compromised professional decision making, a lowering of overall work standards, increased absenteeism, lower morale and higher staff turnover (Koritsas et al., 2008; Stanley & Goddard, 2002).

Gathering data about the magnitude and nature of client violence towards workers also matters because 'if you don't ask, you don't know, and if you don't know, you can't act' (Krieger, 1992, p. 412). Borrowing from interdisciplinary public health experts (Lee, Teutsch, Thacker, & St Louis, 2010), gathering data about the size and nature of a particular problem is necessary to inform prevention and intervention strategies.

Methodology

In order to map the scale of the problem, a rapid review of the literature was undertaken to find the most pertinent and recent research on this topic. A rapid review was employed in order to reduce bias in answering the specific question: 'What is the prevalence and nature of client violence towards workers in the child, family and community welfare sector?' This objective and transparent approach to research selection guards against the 'expectancy effect': when the researcher's hypothesis or expectation unintentionally leads to the researcher selecting data that will confirm their expectation (Rosnow & Rosenthal, 1997, p. 43).

The literature was accessed via various databases through the Australian Institute of Family Studies library, which included PsycINFO, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, SocINDEX, E-Journals, PsycARTICLES and MEDLINE. These databases were considered to be the most appropriate social science and psychology databases to search for this topic.

A methodological issue encountered by the authors was that although the Australian context is our primary area of interest, only two Australian studies have explored the prevalence of client violence in social work during the time period reviewed (from 2008). This was confirmed through our scoping research. Therefore, in this paper we widened the scope to include international studies.

Another methodological issue encountered, and reflected in similar papers, was the lack of consistent terminology used across the literature to describe the issue of client violence towards workers. In order to maximise the return of relevant articles, the authors mapped out commonly used terms and developed a Boolean search strategy (see Appendix A).

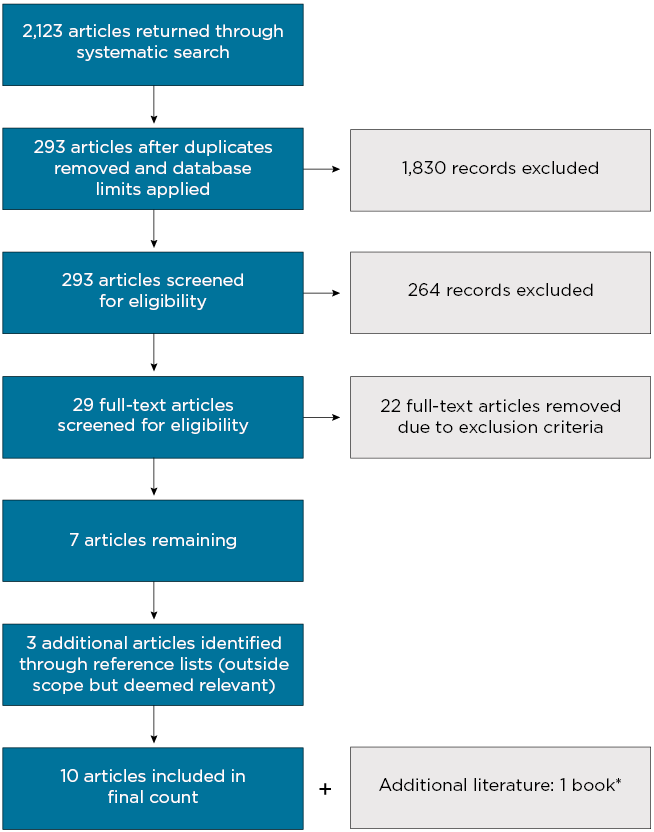

This search strategy was applied to the relevant databases, using 'or' between alternative search terms and 'and' between key words. Search terms were applied to subject headings, titles and abstracts during the systematic search undertaken in September 2018. This search returned 2,123 articles. An inclusion/exclusion criteria was then applied (see Appendix B).

After applying the available limits to the search and removing duplicates, 293 articles remained. A manual screen of titles and abstracts was then undertaken to extract the most relevant articles (29), this was judged by keywords, title and theme of the abstract, and articles with no definitive relationship to the scope of this paper were excluded. The body of the remaining articles were then reviewed by both authors to ensure that primary studies examining prevalence were included. Reference lists were cross-checked to ensure all relevant studies have been sourced. Ten articles were included: seven articles met the inclusion criteria; and on further review an additional three studies were included due to their relevance (a systematic review providing key prevalence data between 1982 and 2012, an Australian study from outside the inclusion time frame and an article reporting on official data that was not an original primary study). These studies will help to establish the nature and prevalence of client violence towards workers.

In addition to these 10 studies, one Australian study (published in a book rather than a journal and outside of the inclusion time frame) and two grey literature reports on Australian official data were identified by the authors and will be included in the discussion of the results. The authors identified these other relevant sources by checking the reference lists of the studies in the rapid review, and by doing Google scholar and internet searches using the key search terms. This was a necessary step to ensure all relevant literature was included in the results, due to a lack of consistent terminology across studies and the small number of Australian studies. A flow chart of the methodology is outlined in Appendix C.

Results

Table 1 provides an overview of the included studies located through a systematic search. These studies will be drawn on in the discussion of results and the implications for policy and practice.

The table can also be viewed on pages 6–14 of the PDF.

| Author/s | Article title | Date & country | Methodology | Sample size (n=) | Prevalence | Other key findings | Implications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Briggs, F. Broadhurst, D. Hawkins, R. | Violence, threats and intimidation in the lives of professionals whose work involved children* | 2004 Aus. | Questionnaire of self-selected participants using network sampling:

| 589 professionals with child protection obligations (214 social workers) | Of the whole sample:

|

|

|

|

| Criss, P. | Effects of client violence on social work students: A national study | 2010 USA | Cross-sectional study:

| 595 Master/ Bachelor of Social Work students |

|

|

|

|

| Harris, B. Leather, P. | Levels and consequences of exposure to service user violence: Evidence from a sample of UK social care staff | 2012 UK | Cross-sectional study:

| 363 social care staff |

|

|

|

|

| Hunt, S. Goddard, C. Cooper, J. Littlechild, B. Wild, J. | 'If I feel like this, how does the child feel?' Child protection workers, supervision, management and organisational responses to parental violence** | 2016 UK | Online survey | 590 child protection workers (402 social workers) |

|

|

|

|

| Koritsas, S. Coles, J. Boyle, M. | Workplace violence towards social workers: The Australian experience | 2008 Aus. | Postal questionnaire of Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) social workers | 216 social workers | In the previous 12 months:

|

|

|

|

| Littlechild, B. Hunt, S. Goddard, C. Cooper, J. Raynes, B. Wild, J. | The effects of violence and aggression from parents on child protection workers' personal, family, and professional lives** | 2016 UK | Online survey | 590 child protection workers (402 social workers) | During previous 6 months:

Impact on workers' personal lives:

Effects on workers' own/wider child protection work:

|

|

| No limitations were discussed |

| Respass, G. Payne, B. | Social services workers and workplace violence*** | 2008 USA | US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2005) | National data on assault injuries between 1995 and 2002 |

|

|

|

|

| Robson, A. Cossar, J. Quayle, E. | The impact of work-related violence towards social workers in children and family services**** | 2014 UK | Systematic review | 7 included studies (Horejsi et al., 1994; Horwitz, 2006; Littlechild, 2005a; Littlechild, 2005b; Newhill & Wexler, 1997; Regehr et al., 2004) |

|

|

| No limitations were discussed |

| Winstanley, S. Hales, L. | Prevalence of aggression towards residential social workers: Do qualifications and experience make a difference? | 2008 UK | Quasi-experimental between groups design | 87 staff members from residential children's homes | In the preceding 12 months:

|

|

|

|

| Zelnick, J. Slayter, E. Flanzbaum, B. Butler, N. Domingo, B. Perlstein, J. Trust, C. | Part of the job? Workplace violence in Massachusetts Social Service Agencies | 2013 USA | Online survey | 2,627 clinical staff 6,395 direct care staff | In the 2009 fiscal year:

|

|

|

|

Notes: *Briggs et al. (2004) was included because it is a highly relevant primary study undertaken in Victoria, Australia. It did not fit original inclusion criteria due to its 2004 publication date. **Hunt et al. (2016) uses the same primary data as Littlechild et al. (2016). The data is used to illustrate two different research theses, both of which are relevant to this paper. ***Respass & Payne (2008) was included as it illustrates prevalence according to official data. It did not fit the original inclusion criteria as it is not an original primary study. ****Robson et al. (2014) was included because it is a systematic review of primary studies undertaken between 1982 and 2012, providing background information on prevalence and helping to establish a trend of violence towards workers. It did not fit the original inclusion criteria as it is not an original study.

1. What do official statistics tell us?

Official statistics on client violence towards workers can provide insight into the prevalence and nature of the problem in different jurisdictions. This section draws from the 10 studies found in the rapid review, and from official data found by extensive online searching in Australia and internationally without date restrictions. Limited official data on the prevalence of client violence towards workers in the child, family and community welfare sector were found for Australia and internationally. Many government and non-government agencies do not collect and/or report on the prevalence and nature of client violence towards workers.

In Australia, two sources of official data were found through online searching: Safe Work Australia (2017; 2018) and the Victorian Auditor-General's Office (2018); neither of these specifically report on the child, family and community welfare sector as a whole.

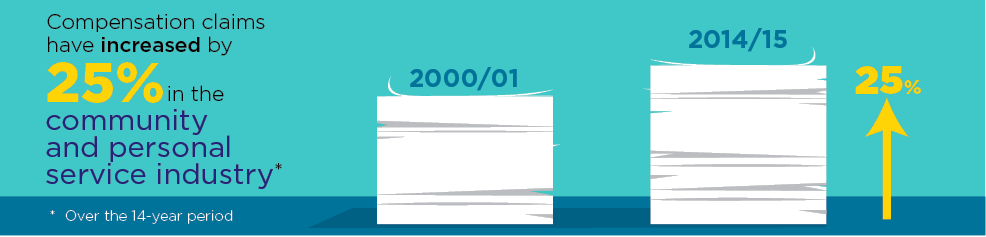

Safe Work Australia is an Australian Government statutory body that reports on the number and nature of serious workers compensation claims3 lodged across occupational groups in Australia each year (Safe Work Australia 2017; 2018). Safe Work Australia does not have an occupational category equivalent to the child, family and community welfare sector; their closest category is the community and personal service industry, which it does not define. A limitation of these data is that incidents of violence towards workers that result in less than one week's absence from work are not reflected in the Safe Work Australia data. According to Safe Work Australia:

- for all compensation claims, there has been a 17% decrease in the total number of claims lodged from 133,045 claims in 2000/01 to 110,280 claims in 2014/15 (Safe Work Australia, 2017)

- the total number of all claims due to being assaulted has more than doubled over the 14-year period (Safe Work Australia, 2017)

- in the community and personal service industry, the number of compensation claims has increased by 25% over the 14-year period (Safe Work Australia, 2017).

Figure 1: Compensation claims in the community and personal service industry, from 2000/01 to 2014/15

Source: Safe Work Australia (2017)

Safe Work Australia has identified that reducing the number and rate of occupational injuries and diseases in the health care and social assistance industry (defined as hospitals, medical and other health care services, residential services and social assistance services) is a national priority (Safe Work Australia, 2018).

The Victorian Auditor-General's Office (VAGO) report on Maintaining the Mental Health of Child Protection Practitioners (2018) suggests the problem of violence and aggression towards child protection workers in Victoria is under-estimated by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services' official data. According to the VAGO report, 142 disease/injury/near miss/accident (DINMA) reports were made by 1,9334 Victorian child protection workers in 2016/17. Of these, 8% were due to exposure to workplace or occupational violence, and 5% were due to harassment (VAGO, 2018).5

Internationally, one source of official data was found through the rapid review process: Respass and Payne (2008). The authors used national US data to determine the rates of violence towards social services workers (referring to assault injuries by clients at work). They defined social services workers as Bachelor of Social Work/Master of Social Work social workers and other workers holding human services and social services positions. Respass and Payne obtained data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2005), which maintained data on all types of injuries experienced by workers in which at least one day of work was missed. Data on assault injuries across five occupations (social service workers, nursing home workers, home health care workers, hospital workers, those working in doctors' offices and all workers in the US) between the years of 1995 and 2002 were gathered. These data showed that:

- In comparing the rate for all workers (2.7 per 10,000 workers) to social services workers (18.3 per 10,000 workers), 'social services workers are at particularly high risk for experiencing some form of workplace violence' (p. 137).

- In 2002, the rate of workplace violence for social services workers was the highest among the groups examined (nearly six times more likely to experience workplace violence than other workers).

- Although all the groups had experienced a decline in workplace violence over the previous years, this was significantly more so for the other groups than for social services workers.

The authors noted that 'it is difficult to gauge the true extent of violence against social services workers' (Respass & Payne, 2008, p. 133). They described their own study limitation as the inability of the data to capture the full prevalence of worker violence, as it requires workers to miss at least one day of work due to an assault. This suggests that their data only represent the most severe workplace injuries. This may be because workers do not report incidents of violence towards them. Or it may be because many government and non-government agencies do not collect and report on this information. Both of these reasons are discussed in section 3.

3 Safe Work Australia data do not cover all cases of work-related injuries, violence and diseases. A serious claim is defined as an accepted workers' compensation claim that results in a total absence from work of one working week or more.

4 According to the Victorian Auditor-General's report (2018) there were a total of 1,933 child protection workers employed across Victoria as of 30 June 2017.

5 These statistics are in addition to records of work-related harassment and/or workplace bullying (6%) and are thus considered sufficiently granular for the purpose of this paper.

2. What does research tell us?

Drawing from the 10 studies included in this review, and from one other relevant study found through a hand search,6 this discussion will focus on: the type and prevalence of violence and aggression workers face from clients; the effect on workers' personal lives and professional practice; organisational responses to client violence towards workers; and risk factors for perpetrating and being a victim of client violence.

Across all 10 studies, workers reported experiencing client violence in the course of their work. The nature of client violence reported by workers in these studies was varied, including: verbal abuse; intimidating behaviour; property damage; theft; stalking; official complaints; threatened and actual lawsuits; sexual harassment; threats of death; threats of death or harm to their families; physical assaults; threats of serious harm with weapons including knives, bombs and firearms; sexual assaults; and being held captive.

Physical assault: prevalence

There were consistent data across all 10 studies demonstrating a high prevalence of actual and attempted physical client violence towards workers. In Australia, Koritsas and colleagues (2008) found that within the previous 12-month period, 9% of workers had experienced physical abuse (which they define as an actual or attempted physical attack such as actual or attempted punching, slapping, kicking or use of a weapon) and 1% had experienced sexual assault. In their Australian study, Briggs and colleagues (2004) found that 24% of participants had experienced physical assault while working. Outside of the scope of the rapid review, Stanley and Goddard's (2002) Australian study found that 18% of workers interviewed had been assaulted by a client, and 8% of workers had been assaulted by a client using an object.

Internationally, Hunt and colleagues (2016) in their UK study found that, over the course of their career, 18% of workers had been physically assaulted (including one worker who was permanently injured as a result of a murder attempt) and 10% had been held captive in a client's home. In their UK study, Harris and Leather (2012) found that 56% of workers had been physically assaulted during their career. Winstanley and Hales (2008), also in the UK, found that 64% of participants had been assaulted within the preceding 12 months, and 56% had been assaulted more than once. Robson, Cossar, and Quayle (2014) in their systematic review found that physical assaults were described across all seven studies they reviewed.

Threats, intimidation and harassment: prevalence

Serious threats of violence, intimidation and harassment from clients or their associates were commonly reported across all 10 studies. For example, Koritsas and colleagues (2008) in their Australian study of 216 social workers found that workers had experienced various forms of violence and harassment by clients within the previous 12 months.

Internationally, Hunt and colleagues (2016), in their UK study, found that over the course of their career, 8% of participants had received death threats, 2% had been threatened with knives, 2% had been threatened with firearms, and 1% threatened with bombs. Harris and Leather (2012), in their UK study, found that 71% of workers had been threatened or intimidated by clients at some stage during their employment.

Another form of harassment that emerged from the studies was aggravated complaints (or the threat of complaints) by clients, as a threatening or intimidating tactic. Littlechild and colleagues (2016) cited a survey undertaken by Community Care in the UK on parental hostility that found that 77% of the respondents had been threatened with complaints. Littlechild and colleagues noted that although some of these complaints may be justified, there are some made with the intention of intimidating and distracting the worker from fulfilling their duties (Littlechild et al., 2016).

Frequency of the behaviour

All of the studies in the review found violence, threats, verbal abuse and intimidation of workers by clients were frequent and repetitive. Hunt and colleagues (2016) in the UK found that almost two-thirds (61%) of participants had been threatened by a hostile or intimidating client in the previous six months; a third of participants (32%) were threatened three or more times in the previous six months; and half (50%) of participants worked with hostile or intimidating clients at least once a week. Harris and Leather (2012, p. 859) in the UK found:

Verbal abuse occurred weekly, or more frequently, for 27 per cent of the sample, while 29 per cent reported threatening or intimidating behaviour to occur at least monthly, if not more often.

Robson and colleagues (2014) in their systematic review found that non-physical forms of client violence were reported as being common - such as verbal aggression, threats and property damage. Six of their seven studies found verbal aggression to be the most common, most frequent and also the most difficult form of client violence to manage, mainly because of the frequency of the aggression (Robson et al., 2014). Winstanley and Hales (2008), in the UK, found that workers commonly experienced repeated work-related aggression from clients.

Effect on workers' personal lives

Across all studies, the detrimental psychological impacts of client violence towards workers were recorded. Common responses to client violence and aggression included stress, anxiety, fear, panic attacks, feelings of burnout, anger, depression, poor sleep, disturbing dreams, social dysfunction, and suffering from physical and mental ill health (Briggs et al., 2004; Criss, 2010; Harris & Leather, 2012; Hunt et al., 2016; Littlechild et al., 2016; Robson et al., 2014; Stanley & Goddard, 2002).

It was found that the fear of future violence can also have a significantly harmful effect on workers, and on students during their social work training (Criss, 2010; Harris & Leather, 2012; Littlechild et al., 2016; Robson et al., 2014). It is not only the experience of direct violence but also the experience of indirect violence that leads to a fear of future violence (Criss, 2010; Harris & Leather, 2012). Criss (2010) found that being indirectly exposed to client violence was even more strongly correlated with fear of future violence than being directly exposed to client violence. When workers indirectly hear about or witness client violence that is directed at other workers, they may be even more fearful of violence than if they were the target of the violence themselves. Criss (2010) suggested this may be because direct threats are better processed, which might give an individual a greater sense of control over whether another incident may occur, whereas vicarious events challenge an individual's sense of control.

Client violence was also found to have a negative impact on workers' own families. Robson and colleagues (2014, p. 933) in their systematic review found:

Threats appeared to have particularly damaging repercussions when perceived to be personally directed at workers and their families.

Some workers in Littlechild and colleagues' (2016, p. 7) study reported having to 'change their names, change their cars, having police alarms fitted to their homes, being subject to police surveillance, or having to take time off work'.

Effect on workers' professional practice

It was commonly agreed across the studies that client violence affects practice, compromising worker confidence, effectiveness and overall work standards (Briggs et al., 2004; Harris & Leather, 2012; Koritsas et al., 2008; Littlechild et al. 2016; Robson et al., 2014; Stanley & Goddard, 2002). In relation to the child protection system, Hunt and colleagues (2016, pp. 19-20) noted:

There are many losses incurred when intimidated workers are inadequately supervised and resourced. Children are not visited as often as they should be, or at all in some cases, due to workers' avoidance because of fears of violence and anxiety … Parental violence also often aids the perpetrator, as their antisocial behaviour can be rewarded by workers not visiting the house or not performing thorough assessments. The result of this is that children do not receive adequate assessment and protection leaving them in danger.

Some studies pointed to client violence towards workers affecting workers' confidence and effectiveness, leading them to avoid seeing clients, having a negative impact on their ability to conduct full assessments and make good decisions about children's and families' lives (Briggs et al., 2004; Harris & Leather, 2012; Robson et al., 2014). Harris and Leather (2012, p. 866) noted that 'the threat of violence can be both pervasive and disempowering'.

Other consequences of client violence towards workers included low morale and high staff turnover (Hunt et al., 2016; Robson et al., 2014), which, it was suggested, could lead to an inexperienced workforce that does not function optimally (Hunt et al., 2016). High absenteeism was also a problem affecting practice, with many studies noting that workers took sick leave as part of their management of the impact of client violence (e.g. 22% of respondents in Briggs and colleagues 2004 study). If social work students are directly or indirectly exposed to client violence when they are on student placement, they may reconsider their desire to be a social worker, before they even start in the sector (Criss, 2010).

Organisational responses

As there is little recent Australian research, the range or adequacy of current Australian organisational responses are not known. Across the studies, many studies noted limited organisational responses to workers reporting client violence. In particular, the lack of adequate supervision was cited as an issue in the Hunt and colleagues (2016) and Littlechild and colleagues (2016) studies. These studies (using the same data sample) found that 42% of workers agreed or strongly agreed that vulnerable children were being put at risk because workers do not get enough supervision and support when dealing with hostile and intimidating parents:

Many workers (42%) reported that the quality of care they are able to provide to children is poorer due to inadequate supervision and support … Participants reported that lack of support had a significant impact on the quality of their practice and the children they are protecting … The accumulation of these issues can lead to experienced workers ultimately leaving child protection … Many participants noted the impact of violence directed to workers on the protected children … Workers expressed empathy towards how the child must feel living with parents who are hostile and intimidating. (Hunt et al., 2016, pp. 17-19)

Several studies also suggested that workers believe management expects them to put up with a certain degree of client violence and aggression as part of the job (Briggs et al., 2004; Criss, 2010; Respass & Payne, 2008; Robson et al., 2014) and to be resilient and to look after themselves (Hunt et al., 2016; Littlechild et al., 2016; Respass & Payne, 2008).

Harris and Leather (2012) noted that 'many social care staff report their experience of the job itself to be intrinsically rewarding and fulfilling, despite their concerns and unhappiness with a number of organisational issues' (p. 865).

Risk factors for victimisation

Many of the 10 studies identified risk factors for being a perpetrator or victim of client violence. Understanding risk factors can inform prevention and intervention strategies.

It is difficult to know whether male or female workers are at greater risk of victimisation, as the vast majority of workers in the studies reviewed are female. Table 2 shows the percentage of female respondents in three of the studies. The majority of child protection workers in Australia are female; beyond the scope of the review, McArthur and Thomson (2012) estimated this figure to be between 84-89% nationwide. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) reported a high proportion of women (79%) working in the health care and social assistance industry in 2017/18.

| Study | Year | Percentage of female respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Harris and Leather | 2012 | 81.26 |

| Koritas et al. | 2008 | 88.00 |

| Littlechild et al. | 2016 | 82.00 |

It is also difficult to know whether perpetrators of violence towards workers are more likely to be male or female. While some of the studies in Robson and colleagues' (2014) review found men to be the most common offenders, others reported women to be more physically aggressive, particularly in the child protection field.

Some studies found that younger workers may be at greater risk of client violence than older workers (Koritsas et al., 2008; Winstanley & Hales, 2008; Zelnick et al., 2013). The reasons for this are not straightforward. Koritsas and colleagues (2008) suggest that age is a proxy measure for experience and that more experienced workers may be less likely to experience client violence. Koritsas and colleagues (2008) and Zelnick and colleagues (2013) found that the more contact workers have with clients, the more likely it is that they will encounter a client who is violent. Zelnick and colleagues stated that 'when staff have more contact hours with clients, their increased risk is logical' (2013, p. 81). It may be that younger workers have more client contact than older workers who may be more likely to enter management roles, and that this may be one of the reasons why younger workers are at greater risk than older workers. Zelnick and colleagues (2013, p. 81) found:

Being a lower paid, lower status worker in social services appears, by the data in this study, to be associated with increased risk of exposure to workplace violence [by clients].

There is some evidence that residential workers are at greater risk of client violence than other workers (Harris & Leather, 2012; Winstanley & Hales, 2008). The fear, anxiety and negative consequences for residential workers are not the same as for other workers. In their study, Harris and Leather (2012, p. 862) found that although:

levels of exposure to client violence were higher in residential work, levels of fear were greater in the field. A possible explanation for this is the fact that interviewees from residential and day care reported feeling protected to some degree at least by the proximity of their team.

Hunt and colleagues (2016) similarly pointed to the added layer of fear and anxiety faced by workers who visit clients in their homes compared to those who work in a more public setting with other professionals present. The findings of Zelnick and colleagues (2013) are somewhat supportive of this; their research showed workers perceived the client home to be the most risky setting for both direct care and clinical staff (although the data revealed that only 12% and 7% of non-restraint related incidents occurred in the home for direct care staff and clinical staff respectively). Some studies indicated that child protection workers are subject to higher levels of client violence than social workers in other child, family and community welfare work settings (Koritsas et al., 2008; Robson et al., 2014).

Some findings indicated that workers in rural locations may be more likely to experience intimidation and violence from clients than workers in metropolitan areas (Koritsas et al., 2008). This may be because workers in rural locations are more likely to work with clients who are also acquaintances and neighbours. Given the small populations, perpetrators of violence may attempt to intimidate and pressure social workers into overlooking a situation rather than taking action to prevent their dangerous behaviours (Koritsas et al., 2008).

6 Stanley and Goddard's (2002) Australian study has been included in this discussion in addition to the 10 studies. This reference was not picked up through the systematic search as it was published in a book rather than a journal, and was outside the inclusion time frame. The study is included in the discussion to ensure all relevant literature is captured, due the small number of Australian studies.

3. The similarities and differences between research and official statistics

The literature shows that similarities and differences exist between research and official statistics. Overall, both datasets indicate the presence of client violence towards workers in the child, family and community welfare sector; however, the official data are scarce and insufficiently granular to convey the breadth of the issue when compared to the research literature. As well, looking at the similarities and differences, this section will identify significant gaps between what is known from research and official data.

Zelnick and colleagues (2013) suggested under-reporting of workplace health and safety incidents was a common phenomenon. The studies found in this rapid review suggest there are a number of reasons for this. In this section, we draw from these 10 studies and the official data. We also refer to a number of additional studies, found through hand-searching reference lists of the 10 studies, supporting the findings from the rapid review and official literature.

Client violence and aggression are viewed as being part of the job

Based on the findings of their systematic review, Robson and colleagues (2014) suggested that the frequency of verbal violence and intimidation from clients, combined with a powerlessness to prevent it, has led workers to accept it as 'as part of the job' (p. 934), contributing to a 'culture of under-reporting' (p. 934). Respass and Payne (2008, p. 138) suggested that 'for too long, it seems that violence faced by social workers in their job setting has been seen as part of the job'. Virkki (2008) agreed that there is a tendency among social workers to habituate to displays of violence from clients due to its high frequency of occurrence. Similarly, Criss (2010, p. 383) found that:

Though verbal abuse can be as damaging as other types of violence, victims often rationalise its existence. It may be that social work students rationalise derogatory speech from a client as part of the job.

These findings are echoed in the Victorian Auditor-General's report Maintaining the Mental Health of Child Protection Practitioners (2018, p. 39):

When we questioned CPPs (child protection practitioners) as to how they managed the psychological effects of such experiences, they most commonly responded that, unless the incident involved physical violence, they do not tend to make reports. CPPs explained that harassment such as being cursed or spat at was something that they 'just had to put up with'. This suggests that abusive behaviour towards CPPs has become a normalised aspect of child protection work.

Workers being told they should be more resilient

A number of studies revealed that some workers feel blamed for the violence perpetrated by clients towards them (Hunt et al., 2016; Regehr & Glancy, 2011; Virkki, 2008). Workers in Hunt and colleagues' (2016, pp. 13-14) study:

were told (by management) that they needed to accept violent and intimidating behaviour as part of the job … they needed to improve their stamina and resilience to cope with intimidating parents, that the problem was workers themselves.

Similarly, Respass and Payne (2008) found that workers were of the view that they should be able to take care of themselves, and that these distorted views can result in workers feeling like they might be blamed for the violence, fearing reprisal and even job loss. Workers in Virkki's (2008) study felt the aggression and abuse directed towards them by clients was not taken seriously by management. Their inability to just put up with the violence resulted in them feeling guilty and ashamed about what they saw as their own lack of professionalism. In some instances, managers were said to have discouraged workers from making a formal report about an incident (Hunt et al., 2016; Virkki, 2008).

Verbal abuse, intimidation and harassment can be difficult to quantify

Ambiguous definitions of violence can result in workers being abused and harmed without recognising the behaviour as abusive (Respass & Payne, 2008). These incidents are then not officially reported. Littlechild and colleagues (2016, p. 3) also found that verbal aggression and threats made to workers were the most difficult forms of violence to manage as it was 'less obvious', 'pervasive' and 'insidious'; even though verbal aggression was widely found to be the most frequent type of abuse experienced by workers (Robson et al., 2014).

Too busy to fill out the necessary paperwork

Busy, unrelenting workloads further dissuade workers from completing the tasks necessary to make a report (VAGO, 2018; Zelnick et al., 2013). Zelnick and colleagues (2013) found that being time poor (referring to both caseloads and the administrative burden involved in reporting) prevented workers from reporting incidents of client violence. The Victorian Auditor-General's report similarly referred to child protection workers 'not completing the DINMA proforma because of workload issues' (VAGO, p. 54). Respass and Payne (2008, p. 133) found that some agencies 'even discourage reporting because of the extra work associated with the process'.

Workers have empathy for clients

There is some limited evidence to suggest that workers do not report client violence because they have empathy for the client. In Regehr and Glancy's (2011, p. 237) study, they suggested that 'under-reporting of threats and violence is endemic', and a reason for this may be the worker's concern about negative consequences for the client. Respass and Payne (2008, p. 133) noted that one of the reasons why a worker may choose not to report client violence was that they may 'believe that the client did not mean to harm them'. They also suggested it may be difficult for workers to view themselves as being both professional and a victim.

It may be hypothesised that there is an apparent tension between the values of social work and holding clients accountable for their actions. The Australian Association of Social Workers' Code of Ethics (2010, p. 7) noted that social workers are: 'committed to the pursuit and maintenance of human wellbeing … [and to] … working to address and redress inequity and injustice affecting the lives of clients, client groups and socially disadvantaged'. Therefore, workers may be reluctant to be tough on violence, if they perceive this as being tough on clients. Given that many clients involved in the child, family and community welfare system face complex issues (such as substance misuse, mental illness, family violence) and suffer multiple disadvantages (Bromfield, Lamont, Parker, & Horsfall, 2010; Lonne, Parton, Thomson, & Harries, 2008), reporting the incident, involving the police and/or pressing charges may seem contrary to the social work ideals of advocacy and support.

Virkki (2008) in her Finnish study similarly suggested there were inherent tensions that exist in the social work profession: between the personal needs of the worker versus the client; self-interest versus professional values; and individual goals versus public objectives. These tensions can hinder the recognition of, and appropriate responses to, client aggression. Tzafir and colleagues (2015, p. 72) suggested that although 'workers are expected to disregard transgressions of their personal dignity to help clients in need', this is not a helpful expectation. They contended that this places clients on a pedestal and forces workers into a position of self-sacrifice. Clients are ultimately disempowered when they are not encouraged to take responsibility for their own destructive behaviours.

Agencies do not adequately collect and/or report on client violence towards workers

A lack of sufficiently detailed data on client violence towards workers found in the research and online searching suggests that many government and non-government agencies do not adequately collect and/or report on the prevalence and nature of client violence towards social workers at a sufficiently granular level. This is also suggested by Zelnick and colleagues (2013, p. 77) in their US study:

There is little discussion in the literature of how agencies collect data on incidents of work-place violence beyond the requirement of reporting an incident to a supervisor.

4. Evidence-informed implications for policy and practice

Based on the rapid review of official statistics and research in this paper, this section provides evidence-informed implications for policy and practice for the response, management and reduction of client violence towards workers. In this section, we draw from the 10 rapid review studies and the official data. In addition, we refer to a number of other studies found through hand-searching reference lists of the 10 studies in order to support the findings from the rapid review and official literature.

Data collection

Main implications from the research

Research suggests the need to:

- collect and report sufficiently granular data on the magnitude and nature of client violence towards workers

- standardise definitions of violence towards workers in data collection

- report on low impact/high frequency incidents of client violence, as well as high impact/low frequency incidences.

Collecting and reporting high-quality official data on client violence towards workers can enable government and community stakeholders to know the extent of the problem, identify where the problem is most prevalent, and track incidence and prevalence over time (Lee et al., 2010). Such data can inform prevention and intervention strategies (as outlined in the following sub-sections on legal and organisational support, and education and training programs). These data may also guide decisions on where further research is needed (Broadley, Goddard & Tucci, 2014). Data collection and reporting could be a joint responsibility between government and non-government organisations.

Research suggests the need to standardise definitions of various types of client violence (e.g. physical violence, death threats, threats of physical harm, threats to harm a worker's family, threatened or actual property damage) across settings (Koritsas et al., 2008; Robson et al., 2014; Runyan, 2001). Common definitions are crucial in order to know the magnitude and nature of the problem, assist in evaluating prevention and intervention strategies, and identify risk factors. Koritsas and colleagues (2008, p. 3) suggested:

Understanding the factors that predict or predispose social workers to workplace violence may aid with the development of interventions that assist social workers to prevent and manage workplace violence.

Research suggests the validity of reporting all instances of client violence towards workers, including low impact but higher frequency incidents such as verbal abuse, harassment, intimidation, threats, property damage and threats of damage. The definition of aggression has evolved and we now know that physical 'injury is not essential to any definition of aggression and that assault need not even have taken place for workplace aggression to be considered harmful' (Winstanley & Hales, 2008, p. 104).

Legal and organisational protection for workers

Main implications from the research

Research suggests:

- There needs to be legislation to protect workers from client violence, beyond WHS legislation.

- Organisations should have a written workplace violence policy, specifying actions to be taken to prevent and respond to client violence.

- Organisations should have clear risk-assessment and risk-reduction processes.

- When a worker experiences client violence, post-incident counselling and support is crucial.

- Organisations should ensure workers are aware of what support to expect in the prevention and response to client violence.

- Workers should be encouraged by their employer to attend training to raise their awareness about the risks of client violence, and to enhance their skill in recognising early warning signs of violence and in de-escalating situations.

In the US, Respass and Payne (2008) recommend that legislators consider how they can help in creating laws that will protect workers and impose strict penalties on violent clients.

In 2014, the Victorian Government criminalised threats and assaults of registered health practitioners on hospital premises, or anywhere they are working or providing care or treatment to patients. Health Minister David Davis stated:

This legislation sends a clear message that assaults on doctors, nurses and other health professionals providing care are unacceptable … our new legislation further extends this commitment to all registered health practitioners going about their normal duties … health care workers should not be subject to threatening behaviour, violence and compromised safety … the caring role of our health care workers should be respected … our legislation will send a clear message to ensure that everyone is fully aware that violence will not be tolerated. (Victorian Government, 2014)

In addition to legislative protection for workers, research indicates that organisations should be committed to the prevention of workplace violence from clients (Harris & Leather, 2012; Koritsas et al., 2008). It is acknowledged that many Australian organisations in the child, family and community welfare sector are committed to the prevention of client violence towards workers and have been working hard towards this. A national survey of FaRS-funded service providers in 2017/18 confirmed that survey respondents expressed generally high levels of confidence in their service's procedures and protocols for identifying and managing risk and safety concerns for workers (Harvey & Muir, 2018). Workers in the field should be adequately supported by their workplaces in preventing and dealing with incidents when they occur. 'Staff health and safety should receive the same priority as client's safety and wellbeing' (Macdonald & Sirotich, 2005, as cited by Harris & Leather, 2012, p. 867).

Research suggests that organisations should have a written workplace violence prevention policy, specifying actions to be taken to prevent and respond to client violence, and that all workers should be made aware of the policy (Koritsas et al., 2008; Regehr & Glancy, 2011; Respass & Payne, 2008). Research indicates the policy should include that (but not be limited to):

- All types of client violence, verbal abuse and threats towards workers are not acceptable and not part of the job. Holding clients accountable for their dangerous and illegal behaviour is not incompatible with the values of social work. Workers' right to safety is in no way decreased because they are human services workers (Respass & Payne, 2008).

- Workers are strongly encouraged to report all incidents of client violence (including verbal abuse, threats and intimidation) to management (Jayaratne, Croxton & Mattison, 2004; Koritsas et al., 2008).

- Clients will be given a clear message from the organisation (e.g. through posters or leaflets) that violence and aggression towards workers is not acceptable, and if it occurs the police will be notified (Hunt et al., 2016; Littlechild et al., 2016; Regehr & Glancy, 2011; Stanley & Goddard, 2002).

- Management will take all incidents of client violence seriously by contacting the police and, on police advice, could take criminal action against those who have assaulted or threatened the worker. A call to the police can be a source of additional intelligence on the client about their history of violence or alcohol or other drug misuse. Such information can inform a risk assessment. Additionally, when the organisation takes responsibility for reporting incidents to the police, it takes the burden off individual workers who may feel reluctant to press charges; for example, because they are fearful of retaliation from the client (Hunt et al., 2016; Littlechild et al., 2016; Regehr & Glancy, 2011; Respass & Payne, 2008; Stanley & Goddard, 2002).

Research suggests the following practices should be implemented:

- To assist with the apprehension and prosecution of offenders, workers should be encouraged to obtain and keep any forms of evidence of client violence. Regehr and Glancy (2011, p. 238) recommend that voicemail and text messages should be kept and provided to the police.

All letters, emails, notes and gifts should be retained. Photos should be taken of damage and of messages left on property … contemporaneous recording of incidents are excellent ways of demonstrating a pattern of repetition … while any single occurrence seems innocuous, pages of notes recording reported small events leads to a more compelling argument of threat.

- Organisations should have clear risk assessment processes. This involves consideration of characteristics of the client that are known to increase risk (e.g. a history of previous violent behaviour, alcohol or other drug misuse, expressed threats towards the workers), as well as contextual factors such as opportunity for violence and vulnerability of the victim (Regehr & Glancy, 2011). In order to undertake a risk assessment, workers need to be given the time to review client files before meeting with clients (Respass & Payne, 2008). In some situations, a 'formal risk management assessment may need to be conducted by those with expertise in threat assessment to ascertain the risk of violence towards the victim' (Regehr & Glancy, 2011, p. 237).

- Organisations should have clear risk reduction processes in their policy and practice. For example, this may involve reviewing work routines and creating policies to promote the safety of workers. Workers undertaking home visits should be encouraged to:

- inform others about who and where they are visiting and when they are expected to return

- have a person from the office call to check on safety

- park their car so that a hasty departure cannot be blocked

- terminate visits if a client is substance affected

- be aware of their personal safety and ensure they always have a clear exit plan (Respass & Payne, 2008)

- conduct home visits in pairs, if the client is not known to the service or if there are any known or suspected risk factors

- have another worker present when transporting clients, because of vulnerabilities associated with driving (Respass & Payne, 2008).

- Interview rooms should be designed so that workers have unobstructed access to exit doors, and furniture that can be used as weapons should be avoided (Koritsas et al., 2008). In some situations, workers should be provided with duress alarms (Koritsas et al., 2008). When working with aggressive involuntary clients, the support of the police should be considered (Broadhurst et al., 2010; Respass & Payne, 2008). In the case of voluntary clients, it may be necessary to consider the withdrawal of services. Organisational policies should guide professional boundaries around sharing personal information with clients, suggesting this is kept to a minimum. Social media access should be limited to known parties (Regehr & Glancy, 2011).

- When a worker experiences client violence, post-incident counselling and support from the organisation is crucial (Briggs et al., 2004; Hunt et al., 2016; Koritsas et al., 2008; Respass & Payne, 2008; Stanley & Goddard, 2002).

- Workers should be encouraged by their employer to attend training to raise their awareness about the risks of client violence, to enhance their skill in recognising early warning signs of violence, learn de-escalation skills, and know what support to expect from their organisation in terms of preventing and responding to client violence.

Education, training and professional development

Main implications from the research

Research suggests:

- Education programs (e.g. social work undergraduate programs) should include content on dealing with potential violence and aggression in the workplace.

Education programs, such as schools of social work, should prepare students for the potential for encountering client violence in the workplace. Given the tensions discussed earlier that can underpin social work roles in this sector, students should be educated on strategies for managing client violence. This education is necessary for workers; for example, mental health workers providing therapy to clients while also being responsible for recommending involuntary treatment, or housing workers seeking to support tenants while also being responsible for handing out eviction notices. Child protection workers - for who it is not uncommon 'to be giving evidence against a family in court one day, and visiting the home to support the change process the next' (McPherson & Barnett, 2006, p. 193) - are also at heightened risk. Littlechild and colleagues (2016, p. 8, citing Ferguson, 2005) in the UK expressed the concern that:

perhaps the biggest single deficit of social work, and certainly of social work education, is a failure to get to grips with the complexity of service users and the reality of involuntary clients as they are experienced in practice.

In the Australian context, it has similarly been found that schools of social work7 give little attention to preparing students to deal with aggressive clients (Laird, 2013). The Australian Association of Social Workers (2008) Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards outline mandatory curriculum content; however, 'no mention is made of the knowledge base, communication skills or professional qualities relevant to addressing client aggression' (Laird, 2013, p. 4). The Australian Association of Social Workers (2015) Australian Social Work and Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) 2012 VI.4 Revised January 2015 also makes no mention of effective practice with clients who are aggressive, threatening, hostile or violent.

Research suggests schools of social work and other programs providing education to students likely to work within the child, family and community welfare sector should give attention to educating students about:

- the magnitude of the workplace violence problem (Respass & Payne, 2008)

- theories explaining causes of violence (Respass & Payne, 2008). Students should understand the reasons for client violence specifically, not just to enhance workers' de-escalation skills but also to better meet client needs and minimise the likelihood of violence (Respass & Payne, 2008).

- the consequences of violence in the workplace (Koritsas et al., 2008). This will include educating students about the consequences for workers personally, their families, their practice, their organisations and for clients and their families.

- how to assess and reduce their own risk (Respass & Payne, 2008). This will involve teaching basic principles of risk assessment, risk factors and risk management. The same risk assessment skills that workers commonly apply to their everyday work with children and families should be applied to workers' own safety.

- having self-awareness. Students should understand their own reactions when they deal with people who are hostile or angry (Respass & Payne, 2008).

- verbal de-escalation skills (Respass & Payne, 2008)

- what they should expect from their organisations in terms of supervision, support, protection and counselling (Koritsas et al., 2008)

- the tensions that exist for workers when working in the real world. For example, the dichotomous role of social care/social control, which often provides the context for client violence towards workers, must be acknowledge and grappled with.

Further research implications

The demonstrated lack of Australian studies into the nature and prevalence of client violence towards workers indicates that a comprehensive Australian study on this topic is needed to address the significant knowledge gaps and discrepancies that have been identified in this paper and the existing literature. In particular, this study should include low-impact and high-frequency incidents of client violence, threats and aggression towards workers. Winstanley and Hales (2008) noted that many prevalence studies do not adequately capture the frequency with which staff are victimised, often only reporting on the proportion of staff who have experienced client violence. Winstanley and Hales (2008) suggested that future research should focus on larger-scale, more detailed analyses regarding the frequency of aggression experienced by some workers, and give voice to those workers' experiences.

Limitations

A major limitation of this rapid review is the dearth of studies on client violence towards workers in Australia, indicating an area for future research. Many of the studies referred to in this paper are not easily comparable, for reasons such as methodological differences, differing definitions of client violence and varied time frames within study samples. For example, in some studies, the researchers ask participants about their experiences of client violence over their career and in other studies it is within a specified time frame. This paper also did not comment on the quality of included studies, except to refer to any limitations identified by the authors. Future research should have greater capacity to capture this information. Another limitation of this rapid review is its inability to compare or correlate organisational policies and procedures with workers' experiences of client violence in the child, family and community welfare sector in Australia. Finally, due to the age of some studies, there was an inability to comment on the experience of technology-facilitated client violence towards workers (e.g. being sent threatening text messages). This further reiterates the need for future studies to be undertaken in a current Australian context.

7 There are similar findings in the US and UK (Laird, 2013).

Conclusion

Client violence towards workers is a complicated phenomenon. This paper reviewed evidence about client violence, and the threat of this behaviour, towards workers in the child, family and community welfare sector. While the studies reviewed in this paper were consistent in their findings that client violence towards workers is common, this was not reflected in the official data reviewed in this paper because it measures industry cases rather than specifically reporting on the child, family and community welfare sector. In the official data reviewed, a lack of granularity was found on the safety of workers in the welfare sector.

There is a paucity of research on the experience of Australian social workers exposed to client violence, particularly in roles other than child protection; and the literature indicates sector-wide policy and practice responses are not addressing the extent of the problem.

Official data and research findings indicate that violence and aggression can be viewed as part the job for workers in the sector. Research suggests social workers can experience complex professional tensions around this, as the nature of their role is to provide advocacy and support to people experiencing disadvantage. Workers may feel reluctant to report client violence due to feelings of empathy towards their client, and a desire to shield them from further disadvantage.

It is essential that all workers can practice in a safe working environment. When exposed to client violence, worker wellbeing and professional practice can be compromised, diminishing worker morale and increasing staff turnover. This ultimately impacts the child, family and community welfare sector and the provision of care for their clients.

References

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2008). Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards. Canberra: Australian Association of Social Workers.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Gender indicators, Australia: Economic security (cat. no. 4125.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/4125.0~Sep%202018~Main%20Features~Economic%20Security~4.

- Briggs, F., Broadhurst, D., & Hawkins, R. (2004). Violence, threats and intimidation in the lives of professionals whose work involves children (Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 273). Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Broadhurst, K., White, S., Fish, S., Munro, E., Fletcher, K., & Lincoln, H. (2010). Ten pitfalls and how to avoid them: What research tells us. London: National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

- Broadley, K., Goddard, A., & Tucci, J. (2014). They count for nothing: Poor child protection statistics are a barrier to a child-centred national framework. Melbourne: Australian Childhood Foundation.

- Bromfield, L., Lamont, A., Parker, R., & Horsfall, B. (2010). Issues for the safety and wellbeing of children in families with multiple and complex problems. Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Criss, P. (2010). Effects of client violence on social work students: A national study. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(3), 371-390.

- Harris, B., & Leather, P. (2012). Levels and consequences of exposure to service user violence: Evidence from a sample of UK social care staff. British Journal of Social Work, 42(5), 851-869.

- Harvey, J., & Muir, S. (2018). National survey of FaRS-funded service providers (Research report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/1808_national_survey_of_fars-funded_service_providers-with-image.pdf

- Hunt, S., Goddard, C., Cooper, J., Littlechild, B., & Wild, J. (2016). 'If I feel like this, how does the child feel?': Child protection workers, supervision, management and organisational responses to parental violence. Journal of Social Work Practice, 30(1), 5-24.

- Jayaratne, S., Croxton, T., & Mattison, D. (2004). A national survey of violence in the practice of social work. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 85(4), 445-453.

- Koritsas, S., Coles, J., & Boyle, M. (2008). Workplace violence towards social workers: The Australian experience. British Journal of Social Work, 40(1), 257-271.

- Krieger, N. (1992). The making of public health data: Paradigms, politics, and policy. Journal of Public Health Policy, 13(4), 412-427.

- Laird, S. E. (2013). Training social workers to effectively manage aggressive parental behaviour in child protection in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom. British Journal of Social Work, 44(7), 1967-1987.

- Lee, L. M., Teutsch, S. M., Thacker, S. B., & St. Louis, M. E. (2010). Principles and practice of public health surveillance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Littlechild, B., Hunt, S., Goddard, C., Cooper, J., Raynes, B., & Wild, J. (2016). The effects of violence and aggression from parents on child protection workers' personal, family, and professional lives. SAGE Open, 6(1), 1-12.

- Lonne, R., Parton, N., Thomson, J., & Harries, M. (2008). Reforming child protection. London: Routledge.

- McArthur, M., & Thomson, L. (2012). National analysis of workforce trends in statutory child protection. Canberra: Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University.

- McPherson, L., & Barnett, M. (2006). Beginning Practice in Child Protection: A blended learning approach. Social Work Education, 25(2), 192-198.

- Regehr, C., & Glancy, G. (2011). When social workers are stalked: Risks, strategies, and legal protections. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39(3), 232-242.

- Respass, G., & Payne, B. (2008). Social services workers and workplace violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 16(2), 131-143.

- Robson, A., Cossar, J., & Quayle, E. (2014). Critical commentary: The impact of work-related violence towards social workers in children and family services. British Journal of Social Work, 44(4), 924-936.

- Rosnow, R. L., & Rosenthal, R. (1997). People studying people artifacts and ethics in behavioral research. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Runyan, C. W. (2001). Moving forward with research on the prevention of violence against workers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20(2), 169-172.

- Safe Work Australia. (2017). Australian Workers' Compensation Statistics 2015-16. Canberra: Safe Work Australia.

- Safe Work Australia. (2018). Australian Workers' Compensation Statistics 2016-17. Canberra: Safe Work Australia.

- Stanley, J., & Goddard, C. (2002). In the firing line: Violence and power in child protection work. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Tzafrir, S., Enosh, G., & Gur, A. (2015). Client aggression and the disenchantment process among Israeli social workers: Realizing the gap. Qualitative Social Work, 14(1), 65-85.

- Victorian Auditor-General's Office. (2018). Maintaining the mental health of child protection practitioners. Melbourne: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

- Victorian Government. (2014, September). Tough new penalties for healthcare assaults. Melbourne: Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from www.health.vic.gov.au/healthvictoria/sep14/tough.htm.

- Virkki, T. (2008). Habitual trust in encountering violence at work: Attitudes towards client violence among Finnish social workers and nurses. Journal of Social Work, 8(3), 247-267.

- Winstanley, S., & Hales, L. (2008). Prevalence of aggression towards residential social workers: Do qualifications and experience make a difference? Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(2), 103-110.

- Zelnick, J. R., Slayter, E., Flanzbaum, B., Butler, N. G., Domingo, B., Perlstein, J., & Trust, C. (2013). Part of the job? Workplace violence in Massachusetts social service agencies. Health & Social Work, 38(2), 75-85.

Appendices

Appendix A: Search terms

| Key word | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Worker | child welfare worker, child protection social worker, social worker, child protection worker, community worker, mental health worker, social care worker, housing worker, homelessness worker |

| Violence | worker violence, worker abuse, worker assault, worker trauma, work-based violence, work-based trauma, work-based assault, work-based abuse, workplace violence, workplace trauma, workplace assault, workplace abuse, occupational trauma, occupational violence, occupational abuse, violence against workers, violence towards workers, threats against workers, threats towards workers, abuse of workers |

Appendix B: Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies from 2008 | Studies about healthcare workers specifically (although articles including them in the sample were included) |

| Peer-reviewed journal articles | Studies primarily focused on vicarious traumatisation |

| Studies including violence against workers from clients, clients' friends and clients' families | Studies prior to 2008 |

| Studies including social workers in various sectors | Studies not published in English |

| Published in English | |

| Studies comparable to Western context |

Appendix C: PRISMA diagram

PRISMA diagrams provide a graphical representation of the flow of citations in the course of a rapid review.

* Stanley and Goddard (2002). Met all inclusion criteria except date of publication. Included due to limited additional Australian literature.

Karen Broadley, at the time of writing, was a Senior Research Officer with the Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) information exchange at the Australian Institute of Family Studies. Nicole Paterson is a Research Officer with the CFCA information exchange at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable feedback given by Natasha Cortis, and thank Amanda Coleiro and Rebecca Armstrong for their feedback and advice during the process.

Featured image: © GettyImages/kieferpix

978-1-76016-195-8