Developments to strengthen systems for child protection across Australia

November 2017

Dr Sarah Wise

Download Policy and practice paper

Summary

Child protection systems are multidimensional, complex, continually adapting entities that seek to prevent and respond to protection-related risks. Systems for child protection in Australia today are facing significant challenges. This has created the imperative to go beyond incremental adjustments and aim for transformational change. This paper outlines the latest iteration of changes within Australian child protection systems. It draws on a survey completed by child protection departments across Australia on change and reform planned or underway since July 2010. Change is documented and compared in terms of child protection system principles, goals and components. Considerable changes to systems for protecting children are planned or underway right across Australia. These are being designed and implemented mainly in response to shortcomings identified in independent reviews. They aim to reduce the number of children involved in statutory child protection and out-of-home care (OOHC) and achieve greater permanence and improved outcomes for children who enter OOHC. Addressing the over-representation of Aboriginal children and families in all areas of the statutory child protection system, particularly the high number of Aboriginal children entering OOHC, is an area of particular focus for reform.

Key messages

-

Systems for child protection in Australia today are facing significant challenges including insufficient capacity to meet the quantity and complexity of cases into statutory child protection and out-of-home care (OOHC), failure to improve outcomes for children in OOHC and the over-representation of Aboriginal children in statutory child protection and OOHC.

-

There has been a remarkable degree of reform and change in child protection systems across Australia in recent times.

-

While strategies have been adopted in response to specific concerns and the unique context of service delivery in each jurisdiction, there are many parallels between jurisdictions.

-

Several jurisdictions are establishing new approaches to build a more robust and coordinated community service system, reconfiguring their OOHC and leaving care systems and investing in Aboriginal service organisations, Aboriginal service practices and Aboriginal workforce capacity.

-

To see real and lasting change, the principle of collective responsibility for protecting children must extend to system stewardship. When diverse stakeholders learn and solve problems collaboratively they can foster more effective actions and better outcomes for children and families than they could otherwise accomplish.

Background

Australian state and territory child protection systems are facing significant challenges including:

- insufficient capacity to meet the quantity and complexity of cases into statutory child protection and out-of-home care (OOHC);

- practice concerns in statutory child protection;

- presentation of families with more chronic and complex risks and needs requiring a response that crosses the boundaries of government agencies that isn’t always available;

- the intergenerational cycle of abuse and neglect;

- failure to improve outcomes for children in OOHC;

- unstable OOHC placements, poor outcomes for care leavers; and

- over-representation of Aboriginal children in statutory child protection and OOHC (see reports of public inquiries and reviews referenced in Appendix A and Katz, Cortis, Shlonsky, & Mildon, 2016).

This has created an imperative to go beyond incremental adjustments and aim for transformational change. There is no single optimal system to protect children from abuse and neglect (Katz, 2015) and as Munro stated, there “was no golden age” of child protection (2010, p. 9). Each country must work within its own particular cultural, community, resource and societal context to tackle the task of protecting children. However, jurisdictions can learn from each other and, in particular, from other sectors who take a similar approach to building child protection systems (Connolly, 2014).

The aim of this paper is to chart the changes in Australia in recent years, so jurisdictions can learn from reform happening elsewhere. The paper includes some broad observations on how our systems are evolving and how they can be steered towards their objectives for children and families in the future.

Box 1: Describing and comparing child protection systems

There is a growing body of research that describes and analyses how different countries and jurisdictions manage and implement systems for protecting children. This research helps facilitate discussion about the objectives of such systems and their impact on children, and brings into focus the way systems are developing within a particular country or jurisdiction.

Bromfield and Higgins (2005) provided detailed descriptions of the process of providing statutory child protection services in Australia. Bromfield and Holzer (2008) collected additional information about strategies to integrate statutory child protection with other sectors (health, education and justice) and early intervention approaches to prevent child protection involvement. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW) Child Protection Australia series also includes accompanying information about jurisdictions’ mandatory reporting requirements, child welfare legislation, grounds that indicate a child is in need of protection as well as policy and practice differences that affect the reporting and aggregation of child protection statistics (see AIHW, 2017). Recent changes to jurisdictions’ policies and data systems are also included as an appendix to the annual Child Protection Australia report. The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020 annual report to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) 2012–13 includes information about major and planned state and territory child protection reforms across Australia since 2000 (see Department of Social Services [DSS], 2014).

There is also a body of international research that analyses and compares various aspects of child protection systems. For example, the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) recently compared aspects of the protection and care system in New Zealand with several other jurisdictions around the world, including the Australian state of New South Wales (see Katz, Cortis, Shlonsky, & Mildon, 2016). The HESTIA research project is currently comparing three quite different welfare states (England, Germany and the Netherlands) in order to discover the nature and impact of variations in child protection systems (see Hestia Research Project).

Typologies cluster different child protection systems according to shared characteristics and enable the analyst to focus on similar patterns that recur across jurisdictions (UNICEF, UNHCR, Save the Children & World Vision, 2013b). The typology approach helps us to better understand the nature of different systems and the implications of different approaches to protecting children. This approach builds on the work of Gilbert (1997), who divided child protection systems into “child protection” and “family support” orientated systems by their position on four dimensions: problem frame (individualistic/social), preliminary intervention (legalistic/therapeutic), state/parent relationship (adversarial/partnership) and OOHC placements (voluntary/involuntary). Child focus/child development and community care orientations have since been added to Gilbert’s dichotomy (Gilbert, Parton, & Skivenes, 2011).

The validity and usefulness of protection typologies in describing modern child protection systems, which are more dynamic, complex and multidimensional, has since been challenged. Emerging child protection systems in low and middle income countries have also challenged the fit, nature and scope of typologies built upon the experience of high-income countries.

Experts agree that there are a number of dimensions that can describe child protection systems, such as

- the level of service integration and shared responsibility for children (single or multi-agency responsibility for children);

- the emphasis on early intervention and prevention (preventative vs responsive child protection/response measures);

- the focus of protection efforts (families, institutions, community);

- the degree to which interventions are established or sanctioned by the government (degree of formality/informality);

- overall approach of the system to the child in his/her family and community (e.g., from punitive to a rights-based system);

- the context within which the child protection system operates (fragility/complexity of systems); and

- the performance of the system (see Katz, 2015; UNICEF, UNHCR, Save the Children & World Vision, 2013b).

Project methodology

During November 2016, key contacts in agencies with responsibility for statutory child protection in all Australian states/territories and the Commonwealth Department of Social Services (see Table 1) were invited by Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) to complete a data collection survey. The survey included questions related to actual or planned changes to aspects of the child protection system included in Figure 1 since July 2010.

Key contacts were advised that completion of the survey may require input from other government departments that have a role in preventing entry or re-entry of children into the statutory child protection system. Information contained in completed surveys was transposed into a summary table (see Appendix A [PDF, 2.12 MB]). Key contacts were asked to include links to websites wherever possible. These have been included in Appendix A so readers can access further information. Early in 2017 a draft version of Appendix A was circulated to key contacts for verification. Some information was subsequently updated.

Surveys were completed for all states/territories (with the exception of South Australia) and the Commonwealth. At the time of data collection, the Government of South Australia was preparing its response to the Child Protection Systems Royal Commission report, The Life They Deserve (Government of South Australia, 2016a). The response, Child Protection: A Fresh Start (Government of South Australia, 2016b) signals an intent to significantly reform the statutory child protection system and reorient the broader system for protecting children towards a child development system that devotes resources and efforts to preventing child maltreatment. So, while it was not possible to include South Australia in this comparison and discussion, the South Australian system is undergoing significant transformation.

| State/Territory | Name of Department | Acronym |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | Department of Family and Community Services | FACS |

| Western Australia | Department of Child Protection and Family Support | DCPFS |

| Australian Capital Territory | Child and Youth Protection Services | CYPS |

| Queensland | Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services | DCCSDS |

| Northern Territory | Territory Families1 | DCF |

| Tasmania | Department of Health and Human Services | DHHS |

| Victoria | Department of Health and Human Services | DHHS |

Examining system components, goals and principles

The survey collected information about changes within eight system components or “building blocks” (structures, functions and capacities) that have either been included in earlier child protection system models (e.g., Forbes, Luu, Oswald, & Tutnjevic, 2011; Wulczyn et al., 2010) or described in relevant work on child protection systems change (Allen Consulting Group, 2009; Delaney & Quigley, 2014; Fox et al., 2015; Munro, 2010; NZ Productivity Commission, 2015; Shergold, 2013). The system components examined were system rules, decision-making, feedback, knowledge and evidence, service components, service connections, workforce and service providers.

The survey also collected information about system principles and system goals. System components interact with each another to affect system outcomes, or goals for children and families (UNICEF, UNHCR, Save the Children, & World Vision, 2013a). Principles define and underpin the overall orientation to protecting children.

Further, the survey took a broad view of the people, agencies and sectors that were inside the child protection system. Child protection was conceptualised as both a sector and inter-sectoral, incorporating prevention as a key characteristic and requiring integration with a range of different sectors and coordination between many actors in the system (e.g., civil society, NGOs, state services).

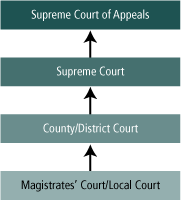

A child protection system model representing system components, system actors, principles and goals was developed specifically for the survey (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Child protection system framework.

It is also important to recognise that this paper intentionally compares jurisdictions in terms of change and reform that has occurred between July 2010 and November 2016 and does not provide a detailed description of system components, goals and principles at a particular point in time. For example, this time frame may not capture several changes introduced in NSW in 2009–10 following the Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into Child Protection Services in New South Wales in 2008 (“Wood Royal Commission Report”; State of New South Wales, 2008) nor will it reflect their position of development on several system aspects.

1 Territory Families was established by the Northern Territory Government on 12 September 2016. Prior to this the Department of Children and Families was responsible for child protection functions.

Efforts to improve systems for protecting children

There has been a remarkable degree of reform and change in child protection systems across Australia in recent times. All jurisdictions with the exception of the Northern Territory currently have a major plan or strategy for reforming their system (or a subsystem such as the OOHC system) for protecting children. The Northern Territory has a number of major activities and initiatives underway. Plans for system reform include:

- Safe Home for Life (New South Wales);

- Their Futures Matter: A New Approach (New South Wales);

- Building a Better Future (Western Australia);

- Building Safe and Strong Families (Western Australia);

- A Step-Up for Our Kids (Australian Capital Territory);

- Supporting Families, Changing Futures (Queensland);

- Strong Families–Safe Kids (Tasmania); and

- Roadmap for Reform (Victoria).

Specific reform efforts are described next.

Principles

Permanency for children is a principle that appears in new legislation in New South Wales, the Northern Territory and Victoria. The Tasmanian Children, Young Persons and Their Families Act 1997 is strongly based on the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCROC) and New South Wales has strengthened children’s participation rights in respect of whether a Guardianship application proceeds. New South Wales legislation requires a child or young person’s consent before a Guardianship Order can be approved. Introducing an expanded paramount principle of “the safety, wellbeing and best interests of a child now and throughout their lives” is one of the options being considered in a current review of child protection legislation in Queensland. Jurisdictions have also articulated a number of principles that underpin and guide reform directions that reflect current attitudes and values about the operation of systems for protecting children. Aboriginal consultation, dialogue and, in some cases, control are key principles of reform, as are principles such as working together and intervening early.

Goals and priorities for reform

While the Commonwealth Government has articulated six high-level outcomes or goals for protecting Australia’s children, with the exception of the Northern Territory,2 which specified five strategic outcomes for the Department of Children and Families, jurisdictions have not articulated an overall purpose for their systems for protecting children. However, jurisdictions have developed outcomes frameworks for human services more broadly (e.g., the New South Wales Human Services Outcomes Framework and the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services Outcomes Framework).3

Jurisdictions have specified remarkably similar strategic goals for reforming systems for protecting children. They include:

- diverting children from statutory child protection;

- reducing re-reporting to statutory child protection;

- increasing exits from OOHC;

- reducing the number of children in OOHC;

- improving outcomes for children in OOHC and post-care; and

- reducing the over-representation of Aboriginal children in the statutory child protection system.

Jurisdictions have also specified how they plan to achieve these goals, such as:

- better use of evidence and building the evidence of effective programs and interventions;

- enhanced analytics capacity;

- use of big data and actuarial calculations to derive evidence and insights about where to target interventions;

- sharing responsibility across organisations and government departments;

- greater use of client-directed and other devolved approaches;

- strengthened processes for continuous improvement;

- improving workforce capability and cultural competence; and

- enhancing prevention and early intervention efforts.

Rules

There have been changes to principle Acts of Parliament relevant to child protection in a number of jurisdictions. Legislation has also been introduced to establish oversight agencies (e.g., Advocate for Children and Young People in New South Wales, Queensland Family and Child Commission (QFCC) and Office of the Public Guardian, and the National Commissioner) or to define and strengthen responsibilities of existing oversight agencies (e.g., Commissioner for Children and Young People, Tasmania). A number of jurisdictions have also made consequential amendments to key child protection legislation to support reform directions. It is particularly noteworthy that within the time frame for this comparison, several jurisdictions have established time limits for reunification and/or introduced new court orders to give children in OOHC a more permanent family life (Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory, New South Wales and Victoria).

New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory have also strengthened Working with Children legislation, while the Australian Capital Territory has amended legislation to better facilitate information sharing. New legislation in New South Wales and Victoria advances self-determination, or the opportunity to participate and exercise meaningful control in the protection and care of children for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Operational protocols, standards and regulations

There are a number of developments designed to strengthen control of how systems for protecting children operate and to ensure that organisations and services adhere to high quality standards. Child-safe standards and guidelines for organisations providing direct care and support to children and for individuals working with children (including carers) are apparent in several states. The Commonwealth Government has also developed national OOHC standards, which the Australian Capital Territory has adopted. New South Wales has developed its own quality assurance framework for OOHC and Tasmania has a quality and regulatory framework for OOHC in development. Similarly, the Northern Territory has introduced a charter of rights for children in OOHC and Victoria is introducing spot audits for residential care units. Several jurisdictions have also established new oversight committees, departmental branches or extended the role of external oversight bodies in relation to system monitoring, as well as new or improved systems for managing adverse incidents and complaints (e.g., New South Wales, the Northern Territory and Victoria).

Decision-making

Western Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland and New South Wales provided information about the establishment of new committees and governance bodies for integrated and/or localised governance and to strengthen relationships between government departments and funded NGOs. Several jurisdictions are also making better use of client feedback and insights, especially in relation to the involvement of children and young people in OOHC or who have had an OOHC experience. This is through the establishment of advisory groups and other innovative methods of engagement. Other stakeholders, particularly funded non-government organisations, are also being engaged in policy design and implementation processes through Ministerial Advisory Groups and other consultative arrangements (e.g., stakeholders were engaged in the design of the Hope and Healing trauma-informed therapeutic framework for the residential care of children and young people in Queensland and ChildStory in New South Wales).

Information was also provided on new frameworks for commissioning services and driving improved outcomes, such as utilising social investment approaches and initiatives under the broad framework of payment or contracting for outcomes (e.g., New South Wales, Tasmania and Queensland) and flexible models for commissioning services, particularly in relation to complex families and OOHC clients (e.g., Victoria and New South Wales). States/territories also indicated more robust performance monitoring approaches as well as targets designed to change operations (e.g., targets for provision of services to Aboriginal children and families and contracts requiring partnerships with Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations in Western Australia). The Australian Capital Territory has established a flat fee for OOHC to encourage efforts to keep children in home-based care instead of residential care.

Feedback on system performance

While current reform agendas have been driven by an external inquiry, internal feedback mechanisms are emerging, particularly in relation to capturing client outcomes and service experience data in OOHC so problems can be detected and acted on in a timely manner. There have also been developments in New South Wales and the Northern Territory to improve system analytic capability. This is in addition to performance monitoring approaches (understanding the processing of cases through targets) outlined under “Decision-making” above.

Knowledge and evidence

There is considerable effort underway to bring practice more in line with research and thereby improve quality of care. This is occurring through building understanding of interventions and service components that are effective, and rigorously evaluating innovative service models. In Queensland, the Queensland Family and Child Commission (QFCC) has legislative responsibility (under s 9(1)(e) of the Family and Child Commission Act 2014) to assist relevant agencies to evaluate the efficacy of their programs, identify the most effective program models and to analyse and evaluate whole system policies and practices. There is also significant investment in testing new initiatives, such as the practice first model in New South Wales, Family Support Networks in Western Australia and the Step-Up for Our Kids reform in the Australian Capital Territory. Some state departments have also formed partnerships to develop new, science-based interventions that can better protect children, such as the Northern Territory partnership with the Menzies School of Health Research to develop a logic model for remote family services.

Jurisdictions are also investing in strategic research to understand how policies are currently working, and to plan for the future. For example, New South Wales has the Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study (underway since 2010) and Western Australia is planning their own longitudinal study of OOHC. Queensland, the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales and the Northern Territory are collaborating with the university sector to develop the evidence base for child and family services (e.g., the establishment of the Institute of Open Adoption Studies in New South Wales). Victoria is undertaking an evidence gap map to inform the development of a child and family research agenda.

At a national level, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) continue to explore options for improved national data analysis and reporting, including longitudinal studies of children in OOHC.

Service components

Several jurisdictions have funded new programs and services that extend the range of services and/or substitute or adapt existing services for protecting children. The details are outlined below.

Early intervention

There has been increased focus nationally on developing early intervention services and approaches in order to divert families from statutory child protection. Most jurisdictions have invested in new and enhanced models of intensive family support (such as the introduction of the SafeCare program in New South Wales and adaptations to the Best Beginnings home-visiting program in Western Australia). The Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory have also invested in new intensive family preservation/support programs and introduced new ways of working with families with complex needs and risks who are involved in multiple services. Aligning the work of family and domestic violence services with family support and child protection is a common theme across these developments.

Queensland has enhanced universal prevention by making the Triple P parenting program free of charge to all Queensland parents and carers of children 16 years of age and younger. Queensland has also taken steps to enhance the natural support networks of parents through the Talking Families social marketing campaign and has integrated the functions of several family support programs into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Family Wellbeing services to provide holistic prevention and early intervention services.

Statutory child protection

Jurisdictions have made several changes across the reporting, intake, investigation/assessment, case planning and case management phases of child protection services. In terms of mandatory reporting requirements, Western Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland and Victoria have all broadened the occupational groups designated as mandatory reporters (relating to sexual abuse in Western Australia). The Australian Capital Territory has introduced a reportable conduct scheme to ensure that allegations of child abuse and certain criminal convictions are identified, reported and acted on. In Western Australia, psychological abuse has been removed as a separate ground for protection. Instead, a definition is provided of emotional abuse that includes psychological abuse and exposure to domestic violence. New South Wales and Queensland have improved and clarified their mandatory reporting guidelines and the Australian Capital Territory is working with the police to improve the quality of reports (notifications). FACS (NSW) is also reviewing its prenatal policy to improve its response to expectant parents and their unborn child who is the subject of a prenatal report.

In relation to the intake phase of child protection, there have been changes to the way government reporting agencies are structured and operate. Western Australia (metropolitan district offices) and the Northern Territory have moved to a central child protection intake model, with the Northern Territory providing a 24-hours a day, seven-days a week response. In Victoria, eight business-hour regional intake services have been replaced by four business-hour divisional services.

Regarding the investigation and assessment phase of child protection, following the example of New South Wales with its introduction of the Joint Investigative Response Taskforce (JIRT) model in 1997, several jurisdictions are moving to a more multidisciplinary approach to the statutory child protection investigation process. This includes the introduction of Multi-agency Investigation and Support Teams (MIST) in Western Australia, a MOU for joint investigations with police in the Northern Territory and multidisciplinary units consisting of police, centres against sexual assault and statutory child protection in Victoria. In March 2014, New South Wales JIRT Agencies implemented a statewide protocol (JIRT Local Contact Point Protocol (LCP)) to assist with the provision of information and support to parents and concerned community members where there are allegations of child sexual abuse involving an institution. This JIRT LCP Protocol has been supported by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. Structured Decision Making (SDM) tools have been introduced in the Northern Territory to facilitate decision-making at critical points in the child protection investigation process.

In terms of case planning and ongoing child protection intervention, models of family group conferences/meetings have also been introduced or are being strengthened at various points in the child protection process (e.g., prior to court proceedings and/or during case planning) to empower families, enhance partnerships with parents involved with statutory child protection and avoid contested court hearings. Family-inclusive decision-making processes include Family Group Conferencing in New South Wales, Signs of Safety Pre-Hearing Conferences in Western Australia and Children’s Court Conciliation Conferences in Victoria. Queensland also has plans to strengthen its family group meeting model.

Measures have also been introduced to help navigate and support families through their involvement with statutory child protection. The Australian Capital Territory has introduced independent advocacy support to birth families of children and young people at risk of, or who have entered, the care system when they are dealing with statutory child protection.

Court processes and child protection orders

There have been several changes to the way in which child protection matters are resolved including changes to court processes, new court networks that allow for greater collaboration with other courts, and changes to care and protection orders. For example, Western Australia is trialling child protection matters in the Family Court to achieve greater collaboration between the family law and child protection systems. A Koori Court has also been established within the family division of the Children’s Court of Victoria. In Queensland, new legislation has enabled the establishment of a new court work model for the statutory child protection system.

As highlighted under legislation in Appendix A, New South Wales, the Northern Territory and Victoria have introduced a new placement hierarchy or set of child protection orders that aim to achieve greater permanency for children in or entering OOHC, while Western Australia has expanded responsible parenting agreements (formal written agreement between a parent and an authorised officer in one of the departments of education, child protection or corrective services).

Out-of-home care

Across Australia, there has been the widespread introduction and/or development of therapeutic care frameworks and care models, including:

- a new evidence-based therapeutic residential care system in New South Wales;

- the introduction of therapeutic assessments and plans in the Australian Capital Territory; and

- the introduction of the Hope and Healing therapeutic framework for residential care in Queensland.

Models of therapeutic residential care are in development in the Northern Territory (in partnership with the Australian Childhood Foundation) and Victoria. In Western Australia, the Department of Child Protection and Family Support (DCPFS) has been certified as a Sanctuary organisation4 contact centres using the Circle of Security model. Western Australia has also introduced the Circle of Security model for day-to-day therapeutic practice with children in residential care facilities and is proposing further changes to focus on healing from trauma. A range of other initiatives to reform the OOHC model are being trialled in Victoria, including a trial of the program Treatment Foster Care Oregon. Queensland is currently reviewing its investment in placement services and the Australian Capital Territory is establishing new and differentiated models of OOHC.

Carer and birth parent supports

New South Wales has expanded its intensive family preservation program to support authorised carers and birth parents. Western Australia has introduced a one-off establishment payment to informal relative carers. Victoria has made additional funding available in connection with new permanency legislation for flexible packages to work with birth families intensively to support reunification and family preservation. Queensland has committed to have all kinship carers supported by a Foster Care Support Agency. Both New South Wales and Victoria have introduced tailored support packages/targeted care packages to provide children and families with services based on need.

Leaving care and aftercare

Ensuring that care leavers have sufficient opportunities to progress toward a satisfactory standard of wellbeing in adulthood has been a focus of reform across several jurisdictions and the Commonwealth. The Australian Capital Territory has extended financial support to young people leaving care until the age of 21 and extended voluntary support to the age of 25. Queensland has introduced new post-care support through the Next Steps After Care service. New South Wales is further developing a leaving care strategy. Under the Care for my Future reform strategy, New South Wales is implementing a number of changes including a reconfiguration of the specialist aftercare services program to provide better access to care leavers from high-risk cohorts. Victoria is trialling the Better Futures leaving care model as part of a system redesign initiative. The Commonwealth funded a trial of Towards Independent Adulthood, an intensive, wraparound case management service in Western Australia. Queensland has also developed the Kicbox mobile phone app to support care leavers, while the Northern Territory has expanded on pre-existing preparation and planning requirements for young people transitioning from care.

Service connections

Several jurisdictions have introduced, or are planning to introduce, common assessment frameworks to build shared knowledge and capacity across the whole system for protecting children. New South Wales is planning the introduction of a common risk and needs identification tool. In Western Australia, a common client self-assessment tool is used across Family Support Networks. Tasmania has committed to promoting the use of the Common Approach more broadly across services, while the Commonwealth has trialled an adapted version of the Common Approach in 13 mental health support services across Australia. The Queensland Strengthening Families Protecting Children Framework for Practice includes a collaborative assessment and planning framework.

Several jurisdictions have introduced, or are trialling, common, visible entry points into community-based services as a way of better connecting families with a network of local services without unnecessary contact with the statutory child protection system. Western Australia is establishing Family Support Networks, the Australian Capital Territory has established the OneLink service and is planning the establishment of Family Safety Hubs, Queensland has established a Family and Child Connect service, Victoria is planning the introduction of Support and Safety Hubs with a focus on the safety of women and children, and New South Wales is trialling local child protection intake and referral services. New roles (lead workers and system navigators) have been introduced to further enhance integrated system and person-centred change.

New multi-disciplinary service models introduced include:

- multi-disciplinary family violence response teams in Western Australia;

- joint Child FIRST and Western Australia Police Child Assessment and Interview Teams;

- Child Safety Coordination meetings in remote areas of the Northern Territory;

- Lookout Education Support Centres in Victoria to improve educational outcomes of children in OOHC; and

- the Child and Youth Protection Service (CYPS), providing integrated care and protection and youth justice management in the Australian Capital Territory.

New information-sharing protocols have also been introduced to improve service journeys, service collaboration and client outcomes. They provide detailed guidance and procedures to inform the way professionals in social care, health, education, domestic violence and police services work together to safeguard children and young people. New legislation has been introduced or is planned/under consideration to facilitate information sharing between prescribed or authorised agencies in Western Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland and Victoria. The Northern Territory has introduced information-sharing guidelines to assist authorised people and organisations to share information about a child or family in order to facilitate working together for the safety and wellbeing of a child.

Building on earlier legislative reform to allow information exchange between human service and justice organisations, New South Wales will soon fully commission the ChildStory client information system, which allows real-time information sharing between FACS, NGOs, education, health, police and justice, and Patchwork, an app that supports team collaboration. In the Australian Capital Territory, Child, Youth and Family Services (CYFS) has access to the police referral gateway SupportLink.

The Commonwealth is also currently developing a best practice model for information exchange, drawing on jurisdictional approaches.

Workforce

There are a number of new measures to better resource and support the child protection workforce. New South Wales and Queensland have introduced practice frameworks that guide statutory child protection: Practice First (New South Wales) and the Strengthening Families Protecting Children Framework (Queensland). Western Australia has implemented the Signs of Safety Reloaded Project to strengthen practice.

Other initiatives to support the child protection workforce include the development of a child protection academy and group supervision sessions in New South Wales, a supervision case practice policy and a learning and development centre in Western Australia and the establishment of case analysis teams and a refreshed supervision framework for child and youth protection services in the Australian Capital Territory. The Northern Territory has also enhanced supervision training for team leaders and managers and established a practice reflection forum and learning hub.

Efforts have also been made to increase workforce capacity in statutory child protection services. Queensland created 47 new frontline and frontline support positions in September 2016 and a further 86 frontline positions in October 2016. The Northern Territory is dealing with critical workforce shortages in child protection through a partnership with Charles Darwin University.

Foster carers and residential care workers

New measures have been introduced in several jurisdictions to better support foster carers and enhance quality of care. These include improved preparation training in Western Australia, Victoria and the Northern Territory as well as new trauma training for carers in the Australian Capital Territory, new training for kinship carers in Queensland and ongoing training opportunities for carers in the Northern Territory, Victoria and Western Australia (via a mobile app). Victoria has also invested $8 million in the immediate upskilling of residential care workers and will introduce mandatory qualifications for residential care workers from 2017 (Certificate IV Child, Youth and Family Intervention (Residential and OOHC)).

Service providers

New South Wales indicated a progressive transition of the provision of OOHC to the NGO sector, while this is planned in the Northern Territory. Queensland is currently reviewing its existing investment into OOHC, which may result in a change to the supplier profile or market.

Discussion and conclusion

Considerable changes to systems for protecting children are planned or underway right across Australia. These are being designed and implemented mainly in response to system shortcomings identified in independent reviews. They aim to reduce the number of children involved in statutory child protection and OOHC and achieve greater permanence and improved outcomes for children who enter OOHC. Addressing the over-representation of Aboriginal children and families in all areas of the statutory child protection system, particularly the high number of Aboriginal children entering OOHC, is an area of particular focus for reform.

While strategies have been adopted in response to specific concerns and the unique context of service delivery in each jurisdiction, there are many parallels. New system architecture is being introduced in several Australian states and territories to build a more robust and coordinated community service system to refer families to. This attempts to divert families from statutory child protection and assist families in a more holistic way, and includes new entry points into the child and family system, changes to confidentiality and information-sharing provisions and new multi-agency teams and services,5 new professional roles to act as service integrators (lead workers, system navigators) and enhanced capacity in prevention, early intervention and intensive family support, including the introduction of innovative services as well as programs and practices that are empirically based.

Several jurisdictions are also progressively changing their OOHC systems through more decisive decision-making when children enter OOHC and new investment to increase capacity in, and diversify the type of, care arrangements. This includes replacing existing OOHC models with new therapeutic and treatment care models and introducing new specialist models of care to accommodate siblings and other client groups. These approaches are often complemented by, or incorporate, more explicit work with birth families to facilitate the earliest possible exit from care. Extensions of financial support and new aftercare services have also been introduced to assist care leavers.

States and territories are also making extensive changes to better support the goal of Aboriginal children living with their families and within their communities. This includes efforts to expand Indigenous employment and service delivery by Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) (including case management of Aboriginal children on a child protection order) by consolidating Aboriginal services and strategies and through capacity building and practice, policy and workforce development. Other measures include Aboriginal cultural training for the mainstream child and family workforce, strengthening family involvement in child protection decision-making and planning, earlier identification of Aboriginality and a strengthened approach to developing cultural plans to support the needs of Aboriginal children who reside with non-Aboriginal carers.

Other system alterations include strengthening the workforce (including foster and kinship carers) through better training supervision/coaching, enhanced practice frameworks and measures to deal with understaffing in child protection, strengthening external oversight and increasing compliance with standards (especially in relation to child-safe organisations and the screening and regulation of authorised carers), new policy-making approaches (such as social investment and co-design) and new commissioning frameworks and funding models that allow greater flexibility to work around the needs of clients and develop innovative program approaches.

While the current iteration of child protection changes are well-intentioned and, on the surface, appear substantial, the question remains as to whether they will address systemic challenges and lead to the better protection of children. Making decisions for the future has never been easy and previous reforms have not led to the expected level of improvements. Whether the changes actually get to the complex and multi-level root causes of systemic failures and challenges, whether the strategies target high impact change levers, the extent to which measures are well-designed and well-implemented, and the synergistic effect of a suite of reforms occurring in a complex environment fraught with uncertainties will all have a bearing on whether these actions today see results.

There are several things we don’t know about the success or otherwise of current reforms; however, we do know that system strengthening is not a singular “event”. The complex problem of child maltreatment and child removal will need to be managed through a continuous process of adaptation. System stewardship as an improvement model is a promising way forward. This requires leaders and decision-makers who understand how systems behave, who can foster shared learning and shift the collective focus from reactive problem-solving to co-creating future action (Senge, Hamilton, & Kania, 2015). The rudiments of a system learning approach are evident in developments in policy-making that connect feedback loops, strategic research, evaluation and data to decision-making and which engage policy people with diverse stakeholders through collaborative forms of governance and co-design. To produce real and lasting change for children and families, the principle of collective responsibility for protecting children must extend to system stewardship.

5 Often for the purpose of increasing safety for people experiencing domestic violence.

List of abbreviations

| ACCOs | Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations |

|---|---|

| CP | Child protection |

| DSS | Department of Social Services |

| OOHC | Out-of-home care |

| SDM | Structured Decision Making |

| UNCROC | United National Convention on the Rights of the Child |

References

- Allen Consulting Group. (2009). Inverting the pyramid: Enhancing systems for protecting children. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY). Retrieved from <www.eccq.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/inverting-the-pyramid_2009.pdf>.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2017). Child protection Australia 2015–16 (Child Welfare Series no. 66). Cat. no. CWS 60. Canberra: AIHW.

- Bromfield, L., & Higgins, D. (2005). National comparison of child protection systems (Child Abuse Prevention Issues No. 22). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/issues22.pdf>.

- Bromfield, L., & Holzer, P. (2008). A national approach for child protection: Project report. Commissioned by the Community and Disability Services Ministers’ Advisory Council. Australian Institute of Family Studies National Child Protection Clearinghouse. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/cdsmac.pdf>.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2009). Protecting Children is Everyone’s Business: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/child_protection_framework.pdf>.

- Connolly, M. (2014). Toward a typology for child protection systems. UNICEF webinar. 15 April 2014. Retrieved from <knowledge-gateway.org/sharetlfnkvyxl1z4231db79t3kxc66t7bdffv0s/childprotection/cpsystems/webinarcpsystems/library/zl1amq6h?o=lc>.

- Connolly, M., Katz, I., Shlonsky, A., & Bromfield, L. (2014). Towards a typology for child protection systems: Final report to UNICEF and Save the Children UK. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

- Delaney, S., & Quigley, P.C. (2014). Understanding and applying a system approach to child protection: A guide for program staff. Child Frontiers and Terre de homes. Retrieved from <www.tdh.ch/sites/default/files/tdh_e.pdf>.

- Department for Education. (2011). The Munro Review of child protection: Final report. A child-centred system. London: Department for Education. Retrieved from <www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/175391/Munro-Review.pdf>.

- Department of Social Services. (2014). National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020: Annual report to the Council of Australian Governments 2012–13. Canberra: DSS. Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/10_2014/nfpac_annualrpt201213.pdf>.

- Fox, S., Southwell, A., Stafford, N., Goodhue, R., Jackson, D., & Smith, C. (2015). Better systems better chances: A review of research and practice for prevention and early intervention. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY). Retrieved from <www.aracy.org.au/publications-resources/command/download_file/id/274/filename/Better-systems-better-chances.pdf>.

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (Eds.). (2011). Child protection systems: International trends and orientations. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Government of South Australia. (2016a). Child Protection Systems Royal Commission, The life they deserve: Child Protection Systems Royal Commission report, Volume 1. Summary and report. Adelaide: Government of South Australia. Retrieved from <www.agd.sa.gov.au/projects-and-consultations/projects-archive/child-protection-systems-royal-commission>.

- Government of South Australia. (2016b). Child protection: A fresh start. Adelaide: Attorney General’s Department. Retrieved from <www.childprotection.sa.gov.au/sites/g/files/net916/f/a-fresh-start.pdf>.

- Forbes, B., Luu, D., Oswald, E., & Tutnjevic, T. (2011). A systems approach to child protection. A World Vision discussion paper. World Vision International. Retrieved from <www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/Systems_Approach_to_Child_Protection.pdf>.

- Foster-Fishman, P. G., Nowell, B., & Yang, H. (2007). Putting the system back into systems change. A framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39(3–4), 197–215.

- Katz, Cortis, Shlonsky, & Mildon. (2016). Modernising child protection in New Zealand: Learning from system reform in other jurisdictions. Wellington: Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit, Superu. Retrieved from <www.superu.govt.nz/sites/default/files/Modernising%20Child%20Protection%20report.pdf>.

- Katz, I. (2015). What is a good child protection system? And how can we measure it? Paper presented at Haruv Conference, Jerusalem. Retrieved from <haruv.org.il/_Uploads/dbsAttachedFiles/IlanKatz(1).pdf>.

- Munro, E. (2010). The Munro Review of Child Protection: Part one. A systems analysis. London: Department for Education. Retrieved from <www.gov.uk/government/publications/munro-review-of-child-protection-part-1-a-systems-analysis>.

- New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2015). More effective social services. NZ Productivity Commission. Retrieved from <www.productivity.govt.nz/sites/default/files/social-services-final-report-main.pdf>.

- Senge, P., Hamilton, H., & Kania, J. (2015). The dawn of system leadership. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter. Retrieved from <ssir.org/articles/entry/the_dawn_of_system_leadership>.

- Shergold, P. (2013). Service sector reform: A roadmap for community and human services reform. Retrieved from <vcoss.org.au/documents/2013/07/FINAL-Report-Service-Sector-Reform.pdf>.

- State of New South Wales. (2008). Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into Child Protection Services in NSW. Sydney: State of New South Wales through the Special Commission of Inquiry into Child Protection Services in NSW. Retrieved from <www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/33796/Volume_1_-_Special_Commission_of_Inquiry_into_Child_Protection_Services_in_New_South_Wales.pdf>.

- UNICEF, UNHCR, Save the Children, & World Vision. (2013a). A better way to protect ALL children: The theory and practice of child protection systems. Conference Report. New York: UNICEF Child Protection Section. Retrieved from <www.unicef.org/protection/files/C956_CPS_interior_5_130620web.pdf>.

- UNICEF, UNHCR, Save the Children, & World Vision. (2013b). Towards a typology for child protection systems: Revised discussion paper. New York: UNICEF Child Protection Section. Retrieved from <file:///Users/wise/Downloads/revised%20typology%20paper%20-%20FINAL.pdf>.

- UNICEF. (2015). Child protection resource pack: How to plan, evaluate and monitor child protection programmes. New York: UNICEF Child Protection Section. Retrieved from <www.unicef.org/protection/files/CPR-WEB.pdf>.

- Wulczyn, F., Daro, D., Fluke, J., Feldman, S., Goldek, C., & Lifanda, K. (2010). Adapting a systems approach to child protection: Key concepts and considerations. Working Paper. UNICEF, UNHCR, Chapin Hall, Save the Children. Retrieved from <www.unicef.org/protection/files/Adapting_Systems_Child_Protection_Jan__2010.pdf>

Dr Sarah Wise currently holds a joint appointment within the Department of Social Work at the University of Melbourne and the Berry Street Childhood Institute as the Good Childhood Fellow. Sarah conducts academic research in the early childhood and child protection fields and works to integrate knowledge into service systems and programs designed to support children with vulnerabilities.

The author expresses her appreciation and thanks to the people within government departments for completing the data collection template and reviewing an earlier draft of the paper. The author is also most grateful to Kathryn Goldsworthy, Senior Research Officer at the Australian Institute of Family Studies for liaising with government departments and undertaking other logistical and administrative tasks. Great thanks is also due to Professor Ilan Katz of the University of New South Wales Social Policy Research Centre for his critical insights and comments on a draft of this paper.

Featured image: © istockphoto/Kikovic

978-1-76016-138-5