Enhancing the implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle

Policy and practice considerations

August 2015

Fiona Arney, Marie Iannos, Alwin Chong, Stewart McDougall, Samantha Parkinson

Download Policy and practice paper

Overview

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle ("the Principle") was developed in recognition of the devastating effects of forced separation of Indigenous children from families, communities and culture. The Principle exists in legislation and policy in all Australian jurisdictions, and while its importance is recognised in many boards of inquiry and reviews into child protection and justice systems, there are significant concerns about the implementation of the Principle. Recent estimates suggest the Principle has been fully applied in as few as 13% of child protection cases involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. The purpose of this paper is to explore the contemporary understanding of the Principle, and review the multiple and complex barriers at the policy and practice levels which are impeding its implementation. Promising approaches that might address these barriers are also examined.

Key messages

-

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle was developed in response to the trauma experienced by individuals, families and communities from government policies that involved the widespread removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

-

The fundamental goal of the Principle is to enhance and preserve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children's connection to family and community, and sense of identity and culture.

-

The Principle is often conceptualised as the "placement hierarchy", in which placement choices for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children start with family and kin networks, then Indigenous non-related carers in the child's community, then carers in another Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community. If no other suitable placement with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander carers can be sought, children are placed with non-Indigenous carers as a last resort, provided they are able to maintain the child's connections to their family, community and cultural identity.

-

However, the aims of the Principle are much broader and include: (1) recognition and protection of the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, family members and communities in child welfare matters; (2) self-determination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in child welfare matters; and (3) reduction in the disproportionate representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the child protection system.

-

Related to these aims are five inter-related elements of the Principle: prevention, partnership, placement, participation and connection.

-

Implementation of the Principle varies between and within jurisdictions, and concerns have been raised about the implementation of the Principle in terms of the physical, emotional and cultural safety of children.

-

Barriers to implementation include the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the child protection system, a shortage of Indigenous carers, poor identification and assessment of carers, inconsistent involvement of Indigenous people and organisations in decision-making, deficiencies in the provision of cultural care, and inconsistent quantification and monitoring of the Principle.

-

Supports to implementation include approaches based on partnerships between communities and governments, with a focus on enhancing understanding of the intent of the Principle, improving links between legislation, policy and practice, providing earlier supports for families, recognising and enhancing leadership, participation and decision-making among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and enhancing the recruitment and assessment of Indigenous carers.

Background

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle ("the Principle") was developed 30 years ago from an understanding of the devastating effect of the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families and communities, which created the legacy of what is now known as the Stolen Generations. The Principle upholds the rights of the child's family and community to have some control and influence over decisions about their children. It also prioritises options that should be explored when an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child is placed in care so that familial, cultural and community ties can remain strong.

Culture, land and spirit are tied together so closely that you can't have one without the other, but it's not a complete story without family - it's like building a house without mortar, it makes it the right shape but there's nothing to hold it together. (Williams in SNAICC, 2012, p. 8)

The Stolen Generations refer to the practice of forcibly removing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families by Australian federal and state government agencies and missions, under acts of their respective parliaments (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1997). In 1997 the Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families revealed the extent of forced removal policies, a practice which went on for 150 years up to the early 1970s (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1997).

The report revealed the devastating effects of the forcible removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, and their experiences of physical, psychological and sexual abuse once removed, in terms of spiritual, emotional and physical trauma, as a direct result of the broken connection to traditional land, culture and language and the separation of families, and the effect of these on the ability to provide nurturing consistent care to children (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1997; Litwin, 1997).

These effects continue into present times, and are now considered trans-generational as they have spanned many generations (Department of Education and Child Development, 2014; Dudgeon, Wright, Paradies, Garvey, & Walker, 2010; Haebich, 2000).

Societal, environmental and poverty-related risk factors for children exist across all of society. However, when looking at risk factors impacting on Aboriginal children in child welfare the impacts of intergenerational experiences of dispossession, cultural erosion and policies of child removal must be considered. These issues not only impact on families, but also on the ability of families to seek or accept help from a system perceived to have caused or contributed to problems in the first place. (Northern Territory Government, 2010, p. 116)

There are still grave concerns about the removal of Aboriginal children from their families and communities, the absence of connection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to culture, country, language and family and the effect on future generations (Ah Kee & Tilbury, 1999; Libesman, 2011). Connection to family, community and culture is essential for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in their social and emotional development, identity formation, and physical safety (Lewis & Burton, 2014; Lohoar, Butera, & Kennedy, 2014). These connections provide a large support network for both children and parents where responsibility is shared and builds security, trust and confidence that the community is there for support whenever it is needed. Having a community with "many eyes" watching over each other's children allows the children to explore, grow and develop both through independent experience, safe in the knowledge that they are being looked out for, and adopting positive behaviours modelled by their family and community members. A strong sense of community connection enables children to develop a positive self-identity, as well as strengthening their resilience and emotional strength (Lewis & Burton, 2014).

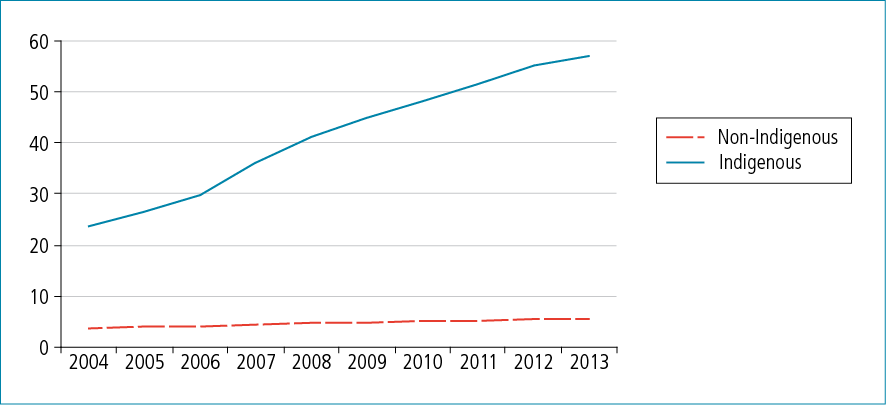

However, in some jurisdictions in Australia, the rate of Indigenous children in foster, kinship and residential care on any one night has reached almost one in ten (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2014). This rate is almost 11 times higher than non-Indigenous children and has steadily increased over the past decade (see Figure 1; AIHW, 2014). Contrast this with rates of non-Indigenous children in out-of-home care, which have stabilised in most jurisdictions.

Figure 1: Rate per 1,000 Indigenous and non-Indigenous children in out-of-home care at June 30, by year

Source: AIHW, 2014.

There are clear imperatives to redress the wrongs of the past by acknowledging the impact of past policies and the abuse and traumatisation of generations of Indigenous Australians, to provide healing for those who have suffered as a result of these policies, to find solutions within culture and community and to take clear steps to prevent children being disconnected from family, community, identity and language and from suffering further abuse and trauma. These imperatives are recognised through human rights mechanisms including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle grew from a grassroots community movement initiated by Aboriginal and Islander Child Care Agencies (AICCAs)1 during the 1970s. AICCAs strongly advocated for the best interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, and aimed to abolish the harsh practices and policies of forced removal. Inspired by the success of the Indian Child Welfare Act 1978 for Native American Indians in the United States during this period, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle similarly sought to establish distinct national child welfare legislation and policy focused on reducing rates of child removal, and enhancing and preserving children's connections to family and community as well as their sense of cultural identity (Tilbury, Burton, Sydenham, Boss, & Louw, 2013). Over time, the Principle has been introduced into legislation and policy across all Australian states and territories.

The fundamental goal of the Principle is to enhance and preserve Aboriginal children's connection to family and community and sense of identity and culture. In child protection legislation, policy and practice, the Principle has often been conceptualised as a placement hierarchy "guide" for Aboriginal children who are not able to remain in the care of their parents. In general, placement priorities in descending order start with:

- within family and kinship networks;

- non-related carers in the child's community; then

- carers in another Aboriginal community.

If no other suitable placement with Aboriginal carers can be sought, children are placed with non-Indigenous carers as a last resort, provided they are able to maintain the child's connections to their family, community and cultural identity. However this demonstrates a limited understanding and only partial application of the Principle across Australia.

As Tilbury et al. (2013, p. 7) explained, there is:

a misperception that the Principle is only about a placement hierarchy for out of home care, the [Principle], however is not just about where or with whom an Aboriginal child is placed. Placement in out of home care is one of a range of interventions to protect an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child at risk of harm. The history and intention of the Child Placement Principle is about keeping Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander children connected to their family, community, culture and country.

Furthermore, fundamental to the Principle is the recognition that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have the knowledge and experience to make the best decisions concerning their children (Tilbury et al., 2013):

Our families are essential to our children's experience of, and connection with, their culture and thus their healing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people learn and experience our culture and spirituality through our families: whether through our knowledge, stories, and songs from parents, grandparents, Elders, and uncles and aunts, and through everyday lived experience of shared values, meaning, language, custom, behaviour and ceremonies. (Williams in SNAICC, 2012, p. 8)

The Secretariat for National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC), Australia's peak body in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child care, suggests that the aims of the Principle must be conceptualised in broad terms; that is to:

- recognise and protect the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, family members and communities in child welfare matters;

- increase the level of self-determination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in child welfare matters; and

- reduce the disproportionate representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the child protection system (Tilbury et al., 2013).

From these three broad aims, five inter-related elements of the Principle flow: prevention, partnership, placement, participation and connection (see Table 1; Tilbury et al., 2013). The child placement hierarchy is only one of these elements.

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Prevention | Each Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child has the right to be brought up within their own family and community. |

| 2. Partnership | The participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community representatives, external to the statutory agency, is required in all child protection decision-making, including intake, assessment, intervention, placement and care, and judicial decision-making processes. |

| 3. Placement | Placement of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child in out-of-home care is prioritised in the following way: 1. with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander relatives or extended family members, or other relatives or extended family members; or 2. with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander members of the child's community; or 3. with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander family-based carers. If the preferred options are not available, as a last resort the child may be placed with 4. a non-Indigenous carer or in a residential setting. If the child is not placed with their extended Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander family, the placement must be within close geographic proximity to the child's family. |

| 4. Participation | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, parents and family members are entitled to participate in all child protection decisions affecting them regarding intervention, placement and care, including judicial decisions. |

| 5. Connection | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care are supported to maintain connection to their family, community and culture, especially children placed with non-Indigenous carers. |

Source: Tilbury et al., 2013, p. 7.

1 While specific roles of AICCAs vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, AICCAs generally provide support to families including family support and family preservation services which aim to keep families together and prevent child removal, advocacy for children and families, as well as keeping children connected to family and culture if they are to be removed (SNAICC, 2005).

Implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle

The importance of the Principle and its place in child protection legislation and policy has been recognised in major reviews and inquiries into child protection systems across Australian jurisdictions (most recently in the Queensland Child Protection Commission of Inquiry, the Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry, and the Inquiry into the Child Protection System in the Northern Territory).

These inquiries also highlight concerns about compliance, implementation and monitoring of the Principle, echoing difficulties in the implementation of the Principle that have been noted for some time (Ban, 2005; Crime and Misconduct Commission, 2004; Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1997; Johnston, 1991; Lock, 1997). The United Nations Human Rights Committee on the Rights of the Child has also specified poor implementation of the principle as of particular concern to the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children being placed in care (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2012).

Importantly, while self-determination2 in child protection matters may be an aim of the Principle (Libesman, 2014; SNAICC, 2013), it is important to note that implementation of the Principle has not been within the control of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, communities and organisations (Ban, 2005, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1997). The existence of the Principle in legislation is itself not a measure of self-determination, and Litwin (1997) argued that strategies to promote Indigenous autonomy and self-determination within child protection systems have themselves not challenged the prevailing form of mainstream child protection systems. This means that Indigenous child welfare and family preservation processes must be incorporated within systems that have child removal as a core function:

While the previous child welfare policies pursued by both public and private sector agencies have been universally condemned, the questioning of the practice of separating Indigenous children from their families is not just a questioning of the past. These practices continue to be questioned into the present. (Litwin, 1997, p. 319)

Additional concerns about the application of the Principle have related to the lack of adherence to the Principle (i.e., the number of children placed with non-kin and outside of family and community groups and the lack of searching for family placements), the safety of children in some kin and non-kin placements, and the removal of children in care from secure long-term foster placements to family-based placements (Northern Territory Government, 2010). In some cases, inquiries and reviews have raised concerns that the best interests of children have not been considered paramount in determining placements for Indigenous children (Crime and Misconduct Commission, 2004) and conversely that cultural identity and connection have not always been a consideration when making decisions about the best interests of children (Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013a).

Improved implementation of the Principle has become the focus of national attention and action through:

- the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children (Council of Australian Governments, 2009), in which it is embedded as a priority action and is reflected in Outcome 5: Indigenous children are supported and safe in their families and communities;

- the National Standards for Out-of-Home Care (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs [FaHCSIA], 2011), in which the participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in decision-making regarding the care and placement of their young people, and the hierarchy of placement are given specific consideration; and

- the national Family Matters: Kids Safe in Culture, Not in Care project - a community-driven initiative which aims to break the cycle of child removal and halve the number of Indigenous children in out-of-home care by 2018. It identifies increasing compliance with the Principle as one of the key actions related to achieving their vision (Family Matters, 2014, p. 7).

2 Self-determination in Indigenous child protection has been described as "having the means and decision-making powers to look after our own children" (Ah Kee & Tilbury, 1999, p. 4).

Measuring compliance with the Principle

At present, there is no Australia-wide systematic protocol in place to monitor and assess implementation of the Principle. Across Australia, a total of 68% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care were placed with either relatives/kin, other Indigenous caregivers, or in Indigenous residential care (that is, in placements in the first three orders of preference reflected in the placement hierarchy) (AIHW, 2014).

Table 2 shows the number and percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in these placements, in all jurisdictions, by placement type. These proportions vary greatly across jurisdictions, with the percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in placement with relatives/kin, other Indigenous caregivers, or in Indigenous residential care ranging from 40% in Tasmania to 82% in New South Wales (AIHW, 2014).

| Relationship | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous relative/kin | 5,216 | 37.5 |

| Other Indigenous caregiver | 2,225 | 16.0 |

| Other relative/kin | 2,002 | 14.4 |

| Other caregiver | 4,243 | 30.5 |

| Total | 13,911 | 100.0 |

Source: AIHW, 2014

This type of measure of compliance with the Principle has been critiqued as it is an administrative measure that reports on the outcome of the placement decision-making process, without considering whether the process of achieving children's safety and familial and cultural connection outlined by the Principle has been followed (Higgins, Bromfield, & Richardson, 2005). That is, it does not identify the number of placement decisions that complied with all components of the decision-making, participation and support processes as specified in the Principle. Some authors have identified that this kind of measurement actually legitimises the placement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with non-Indigenous caregivers (Valentine & Gray, 2006).

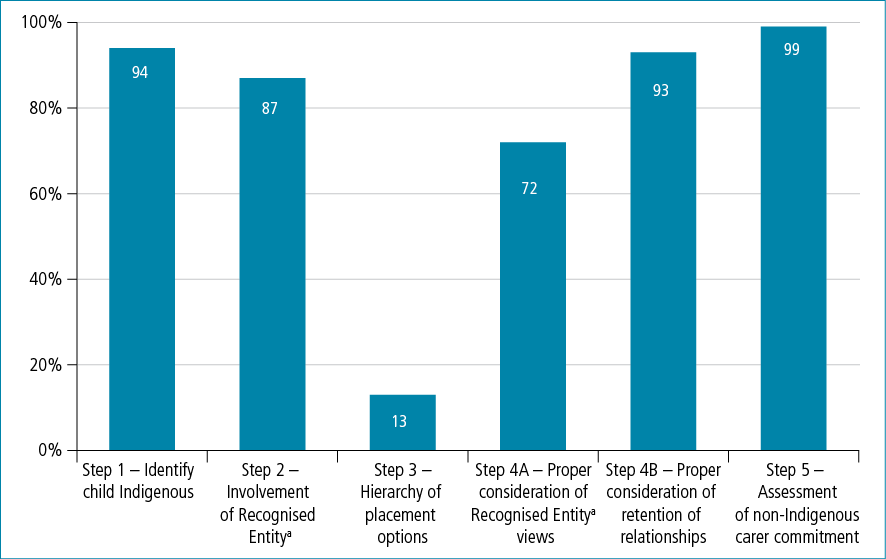

To date, the Queensland Indigenous Child Placement Principle audit conducted by the Commissioner for Children and Young People and Child Guardian has been the only systematic audit aimed at exploring the systemic and practice issues affecting compliance to the Principle in any Australian jurisdiction. Since 2008, three audits have been conducted, with the second and third audit reports in 2010-11 and 2012-13. The audits assessed compliance to the Principle as per five steps that must be followed when considering all placement options for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children as outlined in section 83 of the Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld).

A key finding of this audit was that while compliance within each step was reported as "quite good", full compliance with each of the five required steps, when viewed together, was not achieved at all in the 2008 sample and was only achieved in 15% of the audit sample in 2010-11 and 12.5% in 2012-13 (see Figure 2 for 2012-13 compliance figures).

It is important to note that this audit process used the Queensland legislative framework to examine compliance to the Principle in that jurisdiction alone. This method does not necessarily capture compliance to the broader intent of the Principle described earlier.

Figure 2: Proportion of compliance with each of the five elements outlined in the Queensland Child Protection Act, 2012-13

Source: Commission for Children and Young People and Child Guardian, 2014.

a Recognised Entities are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations or individuals that have been mandated by their communities and approved and funded by the Queensland Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services, to provide culturally appropriate and family advice regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child protection matters.

Barriers impeding the implementation of the Principle

The gap between the intent and application of the Principle has been identified as being due to barriers such as:

- the increasing over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the statutory child protection system;

- a shortage of Indigenous foster and kinship carers;

- poor identification and assessment of carers;

- inconsistent involvement of, and support for, Indigenous people and organisations in child protection decision-making;

- deficiencies in the provision of cultural care and connection to culture and community;

- practice and systemic issues impacting the operation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child care agencies; and

- inconsistent quantification, measurement and monitoring of the Principle across jurisdictions.

These barriers are discussed in more detail below.

The increasing over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the statutory child protection system

As described earlier, rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children entering care have significantly increased over the past decade (see Table 3). The over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children has increased by 140% in the past decade, as compared with rates of non-Indigenous children, which have increased by 50% (AIHW, 2014). Across Australian jurisdictions, between 6% and 28% of Indigenous children have been the subject of a notification to child protection services in one 12-month period (Productivity Commission, 2015).

| Number of children | Rate per 1,000 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Total | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous |

| 2013 | 13,952 | 26,422 | 40,549 | 57.1 | 5.4 |

| 2012 | 13,299 | 26,127 | 39,621 | 55.1 | 5.4 |

| 2011 | 12,358 | 24,929 | 37,648 | 51.7 | 5.1 |

| 2010 | 11,468 | 24,279 | 35,895 | 48.4 | 5.0 |

| 2009 | 10,512 | 23,374 | 34,069 | 44.8 | 4.9 |

| 2008 | 9,070 | 21,539 | 31,116 | 41.3 | 4.6 |

| 2007 | 7,892 | 20,349 | 28,379 | 36.1 | 4.4 |

| 2006 | 6,497 | 18,957 | 25,454 | 29.8 | 4.1 |

| 2005 | 5,678 | 18,017 | 23,695 | 26.4 | 3.9 |

| 2004 | 5,069 | 16,736 | 21,795 | 23.7 | 3.6 |

Source: AIHW, 2014.

The causes for this over-representation and the increasing rates of Indigenous children in care are multiple and complex. They are, however, largely recognised as a combination of factors including the intergenerational effects of forced removal of children, poor socio-economic status, and cultural differences in child-rearing practices (AIHW, 2014). These factors are further exacerbated by a lack of culturally appropriate early intervention and support services, with many services being triggered by involvement with child protection services, rather than before problems reach this crisis point (Department of Education and Child Development, 2014).

In some jurisdictions, as many as three-quarters of notifications to child protection services are deemed to require support other than a child protection response (Bromfield, Arney, & Higgins, 2014; Northern Territory Government, 2010). Many of these children do not receive such a response, and the concerns about their wellbeing may go unaddressed (Arney, 2010). Problems that could have benefited from early support worsen until they reach a threshold for statutory intervention (Northern Territory Government, 2010). Community members and policy-makers liken this focus on responding to harm rather than preventing it as "the ambulance waiting at the bottom of the cliff".

A shortage of Indigenous foster and kinship carers

A significant barrier impeding the implementation of the Principle is the shortage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers (Bromfield, Higgins, Higgins, & Richardson, 2007; Higgins et al., 2005; Richardson, Bromfield, & Higgins, 2005; Richardson, Bromfield, & Osborn, 2007). This is related to a number of factors including the insufficient number of adults to provide care, inadequate methods for identifying kin relationships and assessing carers, carer burnout, fear and mistrust of child welfare systems and eligibility criteria that exclude some carers (Ban, 2005; Bromfield et al., 2007; FaHCSIA, 2012; Higgins et al., 2005; Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Protection Peak, 2011; Richardson et al., 2007).

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children comprise approximately one third of the out-of-home care population, Indigenous people comprise only 2% of the total Australian population. Also, compared with non-Indigenous children and adults, there is an imbalance in the youth dependency ratio,3 which means that there is a greater proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults potentially available to care for them (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2014). For example, nationally the youth dependency ratio for non-Indigenous people is 0.27, but for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people it is 0.6 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013). This has implications for the capacity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to meet the needs of children requiring out-of-home care (Bromfield et al., 2007). In addition, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers may be providing multiple forms of care, including foster care, kinship care, care for their own children and informal care for biologically related or unrelated children (Bromfield & Osborn, 2007; Higgins et al., 2005).

It should be emphasised that the problems in carer recruitment and retention are not caused by a lack of willingness to provide care. On the contrary, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely to provide care than their non-Indigenous counterparts and are often motivated by a sense of duty or obligation to meet the needs of children within their families and to preserve their families' and the child's identity, and a legacy of shared care-giving within families (Bromfield et al., 2007; Higgins et al., 2005; McGuinness & Arney, 2012). However, in addition to the factors identified above, reasons for difficulties in recruitment and retention also include a lack of financial and practical capacity to provide appropriate care. While kinship care is the preferred option of care for Indigenous children, Indigenous kinship carers are more likely to come from a low socio-economic background and live in poorer conditions (McGuinness & Arney, 2012). They often receive less practical and financial support from child welfare bodies than their foster-carer counterparts, including less training, less information and less caseworker support (FaHCSIA, 2012). Furthermore, when training to provide care is available, it is often culturally inappropriate (Richardson et al., 2007).

It has also been shown that many carers are older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (often grandparents), some of whom work in professional positions in carer agencies themselves and feel obligated to take on the responsibilities of providing foster care, as well as caring for their own children (Bromfield et al., 2007; Higgins et al., 2005). Care provision involves not only the financial and practical burdens, but also significant emotional and physical demands. Many children in out-of-home care have highly complex needs and issues, in particular mental health and behavioural problems stemming from their own traumatic abuse experiences (De Lisi & Vaughn, 2011; Lange, Shield, Rehm, & Popova, 2013; Sawyer, Carbone, Searle, & Robinson, 2007). This contributes to high levels of stress and risk of burnout for carers.

Poor identification and assessment of potential carers

Factors that further impede the identification and registration of family members as carers include tight time frames for decision-making (e.g., within 24 hours; Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013a). Kinship carers are often unable to be recruited in advance, and immediate needs for placement of children may mean that children are placed with non-Indigenous carers while family members are sought.

Inconsistencies in practitioner knowledge and skill are a significant issue regarding adherence to the Principle. Some practitioners possess a high level of skill in searching for and assessing potential carers, whereas other practitioners may fail to delve further than the first identified placement for the child. Lack of familiarity with kinship systems and relationships with communities may mean that workers do not know how to identify children's family and kinship ties beyond the immediate family. Hence there may be Indigenous kin who are able and willing to care for children, but who are not known to workers (McGuinness & Arney, 2012). Poorly resourced cultural support can hinder family finding (Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013a) and there is a need to involve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with knowledge of kinships, social structures and local communities for successful recruitment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers.

Where family members are able to be identified, feelings of mistrust and fear of mainstream welfare organisations can affect their willingness to engage and participate as carers (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2014; FaHCSIA, 2012). In addition, systemic barriers to carer recruitment include high levels of disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; for example, chronic housing shortages and overcrowding may mean that potential carers may not be assessed as suitable (Northern Territory Government, 2010). Restrictions regarding the care history or criminal history of potential carers and their family members will also limit the potential number of adults who can be registered as carers because of higher rates of adult imprisonment, criminal history and substantiations of child maltreatment in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (Allard, 2010; Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013a).

Until recently, there have been minimal training and guidelines for kinship carer assessment, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (McGuinness & Arney, 2012; Spence, 2004). Mainstream procedural approaches to assessment, recruitment and training of carers have been identified as barriers to recruitment of Indigenous carers (Libesman, 2011; McHugh, 2011). Carer assessment procedures undertaken by mainstream child protection services do not necessarily account for cultural differences in Indigenous family structures, living arrangements and parenting practices (Higgins et al., 2005). For example, sharing the care of children between multiple adults, not all of whom are biologically related, does not fit with Anglo-centric assessment models based on concepts of a biological nuclear family being the "safest" configuration (FaHCSIA, 2012).

Inconsistent involvement of, and support for, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in child protection decision-making

The Principle outlines a strong focus on the prevention of child protection intervention; however, the lack of focus on this aspect of the Principle in legislation and the lack of resourcing affects agencies' abilities to provide preventative services to adequately address the needs of vulnerable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, families and communities before child protection involvement is required. Among their various roles and responsibilities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies across Australia provide support and services based on an understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childrearing practices to promote family preservation, prevent family breakdown, assist in child protection investigative processes, support children who may need to be placed in out-of-home care, utilise a holistic approach by supporting families to engage with other services (e.g., health, education, domestic violence and legal), provide family reunification services, and advocacy (SNAICC, 2005). However, the involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies in this range of services varies on a jurisdictional and regional basis.

While the legislation in most jurisdictions provides a role for Aboriginal agencies with respect to making placement decisions for Aboriginal children requiring out-of-home care, some jurisdictions give greater recognition to Aboriginal agencies in decision-making than others (SNAICC, 2013). There is a lack of specificity in the legislation and policies with respect to which Aboriginal organisations will play a role in decision-making, the timing of their involvement in care and protection processes, and the level to which they will be involved. Complicating this further is that, at times, conflicting advice may be provided by different Indigenous staff in care and protection matters (e.g., different staff within an Indigenous organisation, or between staff in Indigenous and non-Indigenous agencies, and/or with family and community members).

There is no requirement for Aboriginal children to be placed via an Aboriginal agency and many Aboriginal caregivers, for historical reasons, will not work with state agencies. In addition, even if an Aboriginal child is placed with an Aboriginal family by a non-Aboriginal agency, particularly if not supervised by an Aboriginal worker, Aboriginal culture is suppressed because the placement is subject to the dominant rules, mores, and conventions that inform non-Aboriginal policies, procedures, and practices as well as the values of non-Aboriginal workers (Valentine & Gray, 2006, p. 539).

The sentiment that consultation of recognised Aboriginal agencies and individuals is being implemented as a tick-the-box exercise has been echoed from both mainstream statutory child protection staff and the staff of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations (Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013a). This is despite recommendations (e.g., the Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry) that the responsibility for the placement of Aboriginal children should lie entirely with recognised Aboriginal agencies.

While Aboriginal agencies possess the appropriate cultural expertise, communication and negotiation skills and community connections, and are by far better placed to undertake cultural care work than non-Indigenous agencies, they may be inadequately resourced to do it. This includes having insufficient time, funding, staffing and practical staff supports to undertake the complex and time-consuming family location work, resources to find carers, as well as funding for the practical day-to-day work required to maintain the child's contact with family (Libesman, 2011). This has led to consultation processes that are ad-hoc, with insufficient time and resources and hampered by information-sharing restrictions.

Deficiencies in the provision of cultural care and connection to culture and community

Cultural care is one component of the child's best interests; however, cultural care planning has often been seen in practice as a tick-the-box process, with plans being limited in scope (e.g., being limited to participation in activities such as NAIDOC events). There is an absence of a unifying national practice framework across jurisdictions, underpinning cultural care planning for Indigenous children (Richardson et al., 2007). Research has shown that the integration of cultural care plans in departmental policies, resourcing for plans and how they are implemented in practice vary greatly between jurisdictions (Libesman, 2011).

Another limitation is that cultural care plans are often regarded as static documents, with the child's cultural needs at entry into care remaining their perceived needs throughout their time in care. Cultural support plans should be dynamic documents, which are revised and monitored on an ongoing basis to keep children connected at different stages of their time in care (e.g., initial placement compared with permanent care arrangements).

Non-Indigenous carers and workers require special support to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in their care receive appropriate cultural care. Carers and workers may not have cultural knowledge and training, or connections with the child's community. At present, there are insufficient and inconsistent supports offered to non-Indigenous carers and workers to help them keep the children in their care connected to their family, kin, culture and communities (Libesman, 2011).

Practice and systemic issues impacting the operation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child care agencies

Research has suggested that there is a lack of adequate and uniform procedural knowledge with regard to the application of the Principle. This is particularly so with respect to administrative procedures and record-keeping between statutory child protection departments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies to ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children receive an ongoing connection to culture and family (Libesman, 2011).

Some of these procedures include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations but see this inclusion as a tick-the-box exercise rather than as serving an essential role in decision-making about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and the building of cultural competence in non-Indigenous services. Related to this, incredibly short time-frames and the under-resourcing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies to provide cultural support and services may affect the information and service that can be provided, with resources being thinly spread in order to meet statutory and funding requirements (Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013b).

The importance of adequate resourcing and establishing effective, respectful working relationships between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies and non-Indigenous departmental and NGO staff involved in child welfare cannot be underestimated.

High workforce turnover in government and Indigenous agencies has been identified as a significant barrier to supporting strong relationships and continuity of care across all aspects of child protection and out-of-home care service provision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. The impacts of this turnover include the loss of cultural, community and organisational knowledge as well as the costs of training and support for new staff.

Related to high turnover and high workloads is incomplete record-keeping. The Queensland Commission for Children and Young People and Child Guardian's audit of the implementation of the Principle in that jurisdiction has repeatedly identified poor record-keeping in statutory services as an impediment both to the implementation of the Principle and to assessing compliance with it (Commission for Children and Young People and Child Guardian, 2014).

Libesman (2011) has also identified that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies may not place the same emphasis on documenting and reporting on outcomes and processes as non-Indigenous organisations, making it difficult to argue for their effectiveness. In this focus group research, some staff in Aboriginal agencies identified some weaknesses in compliance with record keeping and documentation requirements, potentially as a result of the perceived lack of relevance and purpose of documentation, and the precedence of other more pressing responsibilities including the provision of cultural support. The pressure on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies to provide more services for specialised cultural advice and assistance than they are funded for, means there is less time available for administrative/record-keeping tasks (Libesman, 2011).

Inconsistent quantification, measurement and monitoring of the Principle across jurisdictions

One major issue affecting our understanding of the factors which impact on compliance with the Principle relates to how compliance data can be quantified, measured and monitored. SNAICC (2013) suggested that jurisdictions differ in the ways they monitor, measure, collect and report compliance data. These inconsistencies make data interpretation and reporting difficult, particularly when comparing and interpreting the data at a national level. The problems are created by differing legislation, policies and practices in government departments who employ varying methodologies to collect and report on the numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in care, the involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies and the placement decision-making processes. There is also a lack of community control over monitoring adherence to the Principle (Ban, 2005).

Current statistics only count children entering the care system, not those who are successfully prevented from entering the system or who are able to return home to their families. It appears that the collection of child protection data is "removal" focused, rather than "reunification driven". Using a broader suite of indicators that examine what decisions are being made about children as soon as they come into contact with child protection systems, those who receive family support and those who progress to out-of-home care may drive changes in practice. Reunification data, noting the number of children who return to their families of origin, will also be an important reflection of the application of the Principle. Because this information is not currently reported on nationally, this means that there is no national accountability regarding these functions of the system with regard to supporting the retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children within their families.

Another area in which concerns have been raised is the identification of the Aboriginality of children. Some authors have identified that in practice Aboriginality may be determined by skin colour (Valentine & Gray, 2006), and children may be de-identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (the notion of "unticking the box") in instances where family could not be found or Aboriginality of children was not confirmed by others who may not know of the child's origins. The implications of "unticking the box" confirming Aboriginality is connected to issues around trans-generational removal and identity. Conversely, there may be situations where a child is first identified as having an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background when in contact with the child protection system, with no prior cultural contact or engagement, and there is no guidance or pathways for dealing with this situation.

3 Defined by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare as the proportion of the population aged under 15 years divided by the proportion of the population aged 15-64 years.

Strategies for improving adherence to the Principle and strengthening outcomes for children

A number of strategies have been identified which in part may support improved adherence to the Principle, and afford more chances for children to remain connected to their families, communities and culture. These strategies are based on partnership approaches between communities and governments, with a focus on:

- enhancing understanding of the intent of the Principle as being far greater than the hierarchy of placement options;

- improving links between legislation, policy and practice;

- providing earlier intervention, prevention and healing supports for families in the context of their communities;

- recognising and enhancing leadership, participation and decision-making of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in child protection matters; and

- enhancing the recruitment, assessment and support of carers.

Some of these approaches represent a seismic shift in working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and children, and their communities - from a "power over" to a "power sharing" relationship, and hopefully to an empowering one. The approaches also include a clear focus on the professional development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous workers to undertake this work in a culturally safe and evidence-based way.

Enhancing understanding of the intent of the Principle

Although the intent of the Principle is to keep children within families, its current definition and description in the legislation conjure negative connotations focused on the removal and placement of children into out-of-home care. This essentially creates a notion of the Principle based on child "rescue" and removal, rather than around family preservation and reunification.

A new understanding, driven by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, has the potential to re-focus system and practice activities on family preservation and keeping children within culture. It is important that the broad intent of the Principle, to keep Indigenous children within their families and communities, is understood by the general public, practitioners and policy-makers.

This includes an understanding that in order to implement the Principle, and to reduce the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children being removed from families, there needs to be a focus on and investment in culturally appropriate early intervention, prevention, family preservation and restoration activities, rather than simply a focus on the placement hierarchy. The five elements of prevention, partnership, placement, participation and connection emphasised by SNAICC (Tilbury et al., 2013) provide a clear framework for this.

It will also be possible to then develop target outcomes and best practice standards based upon this refreshed understanding of the Principle, which can consequently be monitored and overseen at a national level.

Improving links between legislation, policy and practice

Application of the Principle as it was intended requires a shift in attitudes and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family structures and world views. This shift must also occur in parallel across the court and judicial systems, as well as child protection systems. Framing practice and policy approaches with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families in the child protection system within the context of trauma theory and cultural identity has great potential for breaking intergenerational cycles of child protection involvement (Northern Territory Government, 2010). Including a focus on the child's Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander culture as a protective factor, rather than the current conceptualisation of Aboriginality as a risk factor, can strengthen cultural identity and promote links to cultural practices which will promote safety and security for children (Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013b).

"Compliance" with the Principle is not just about focusing on what individual practitioners do, it is also about the systems and programs practitioners work within. Thus a wider perspective of "compliance" can be developed which takes into account practitioner and system/programs levels. For example, the identification of children as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and the identification of kin can be supported at a systems level through the development of policy and practice resources (e.g., to assist with the development of genealogies and links with formal tracing services), cultural competence training specific to child welfare, and the valuing of cultural knowledge through cultural support workers and family finding teams with knowledge of kinship ties in their local region.

Similarly, data gathering and monitoring which assists to educate and inform decision-making for the workforce will support better links between the Principle, policy and practice. The current focus of reporting on the living arrangements of children in out-of-home care does not reflect the original intent of the Principle, which is a focus on keeping children at home or restoring children to the care of their family (i.e., family preservation or conservation and connection). The development of national best practice standards for data collection and monitoring of the Principle could better support policy and practice decisions. These could include standards mapping out data requirements with regard to out-of-home care, reunification, diversion, cultural connection and the decision-making processes. Incorporating the voices of children and young people will also enhance and inform decision-making. Hearing about the experiences of young people will assist in improving quality of care and increase the depth of understanding of the application of the Principle.

Providing earlier intervention and prevention supports for families in the context of their communities

In response to the growing concerns about crisis-based approaches proving ineffective in preventing harm to children and young people, there has been a call for universal, secondary and tertiary prevention efforts that include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, communities and organisations in service design and delivery (Arney, 2010). For example, Indigenous child and family centres can be used to provide support to all young children and their families in a community, as well as platforms for more targeted services and supports for families who might be vulnerable to future problems or who are currently experiencing difficulties in parenting (Arney, 2010; Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2013a).

The following strategies have been identified as ones that could reduce the need for statutory intervention and child removal (see also Arney, 2010, p. 24; Northern Territory Government, 2010):

- Parenting- and family-focused - ensuring that families are strong in culture; connected to other families; and free from substance abuse, mental illness and violence, by:

- providing intensive family support services to strengthen parenting skills and provide respite;

- building social networks and services attuned to child development and connected to specialty care;

- building strong attachment through improved parent-child relationships and communication; and

- addressing parental mental health, wellbeing and safety through provision of child-sensitive adult-focused services.

- Community-focused - ensuring that communities and neighbourhoods are safe, stable and supportive; and that vulnerable communities have a capacity to respond, by:

- promoting strong community norms about the wellbeing of children and young people;

- helping communities to function well and support families within them;

- promoting community healing;

- providing opportunities for participation and the development of social supports; and

- providing services and supports that target populations in communities with concentrated risk factors.

- Child-focused - ensuring that children and young people are nurtured, safe and engaged, by:

- promoting early detection of and response to health, mental health and developmental concerns;

- providing high-quality child care and schools; and

- providing opportunities for youth to engage in civic and community life.

Additionally, strategies aimed at healing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and addressing the impacts of intergenerational trauma can help to reduce the need for statutory intervention and child removal. Established in 2012, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation aims to do this by supporting local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies to develop, deliver and evaluate culturally strong healing programs specifically designed for children and young people, their families and communities. These programs aim to improve the wellbeing and resilience of children, young people and adults by providing opportunities for healing, and to develop positive strategies to cope with pain and loss, as well as to strengthen cultural connectedness and identity.

Recognising and enhancing leadership, participation and decision-making of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in child protection matters.

The success or otherwise of attempts to develop culturally appropriate services (at least from the Indigenous perspective) will be dependent on the agreed basis by which Indigenous communities are to participate in the formal child welfare system, and more importantly the extent to which the relevant State Agency is willing to devolve responsibility for decision making to Indigenous communities. (Litwin, 1997, p. 322)

The importance of leadership and participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including children and young people, in policy development, system monitoring, service design, program evaluation and at the level of individual cases has been emphasised repeatedly (Cummins, Scott, & Scales, 2012; McGuinness & Leckning, 2013; Northern Territory Government, 2010; SNAICC, 2013; United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2012). This has included calls for the expansion in the roles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies in child protection matters, oversight by Aboriginal Children's Commissioners and community involvement in determining priorities for local action and family decision-making approaches that emphasise family involvement in decision-making. Combining decision-making authority for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies and individuals with the delivery of culturally based programs (e.g., Indigenous parenting programs), identification and assessment of kin, family decision-making and cultural care planning, has been identified as holding great promise.

Where families have greater involvement in decision-making in child protection, there is greater trust and less adversarial relationships between families and child protection services (Rodgers & Cahn, 2010). Since their inception, family decision-making models (such as family group conferencing) have been developed and implemented in a number of Australian jurisdictions and internationally (Arney et al., 2010; Brown, 2003; Harris, 2008). Family decision-making processes aim to redress the power imbalance in child protection matters by providing an alternative forum where families are active participants in the decision-making process (Connolly, 2007; 2010). Family decision-making models for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families involve including extended family and respected Elders in decision-making and case planning for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, and may be used in family preservation and reunification processes (Ban, 2005; Department of Human Services, 2007; Linqage International, 2003).

These models have spread widely, albeit not always consistently, because of the appeal of the values underpinning family decision-making models (Arney et al., 2010). This includes the promotion of families' rights to participate in decision-making about their children, and children's rights to have involvement with their family (Barnsdale & Walker, 2007; Brown, 2003; Sundell & Vinnerljung, 2004), the congruence of the model with the Principle (Ban, 2005), participant satisfaction with the elements of the model, and the perceived adaptability of the model to different contexts (Arney et al., 2010). Unfortunately, in some Australian jurisdictions, these family decision-making processes are under-utilised and appropriate weighting is not given to the input of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities involved and therefore limits their influence on decisions relating to child protection (SNAICC, 2013). It is important that these conferences are co-facilitated by a representative from both an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander agency and child protection services so it is indeed used as a joint decision-making process rather than the presentation of pre-arranged outcomes to the family.

As many jurisdictions are looking to review, reintroduce or reframe family decision-making models in child protection matters, there is a role for a national implementation and support body to promote best practice, share learnings and evaluate the impact of family decision-making approaches on the wellbeing and safety of children and the involvement of their families and communities.

Increased involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies in providing cultural advice and support during decision-making processes allows them to act as an independent voice of the community and enhance community leadership and participation in child protection matters (SNAICC, 2013). Several initiatives designed to enhance community leadership and involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies in child protection matters are currently being trialled or implemented across Australian states and territories. One such initiative being trialled in Victoria is the transfer of guardianship for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies within Victoria.

Enhancing recruitment, assessment and support for carers

Effective approaches must be found to increase the recruitment and retention of Indigenous carers. These include increasing the role of community members in identifying potential relative carers and enhancing the understanding of mainstream child practitioners about the resources within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to provide care. Work needs to be done at legislative and policy levels to eliminate the perceived and real barriers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people becoming registered carers; for example, that prior criminal convictions may not preclude people becoming carers. Furthermore, there is a need to reduce the stigma that exists about being a carer by developing culturally informed progressive recruitment, screening and training processes. For example, the Yorganop program (Higgins et al., 2005) actively encourages former young people in care who have had positive experiences to become carers themselves.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship carers are a precious and valuable source of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and require appropriate practical, financial, social and emotional support delivered in a non-invasive way. Culturally appropriate carer assessments, which are based on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander world views and concepts of family structure, are important, rather than relying on assessment systems based on Anglo-centric concepts of nuclear family functioning. This requires the development and use of culturally appropriate assessment tools for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, which can be delivered by appropriately skilled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander assessors and practitioners. The Winangay Kinship Carer's Assessment Tool is a promising resource that has been developed and is undergoing a nationwide evaluation (Blacklock, Arney, Menzies, Bonser, & Hayden, 2014).

Strategies for recruiting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers are likely to be more effective when they are community-generated and conducted by Indigenous people through Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2014). The involvement and resourcing of these agencies in the recruitment, assessment and support of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers means that culturally appropriate approaches can be used that are informed by community knowledge and cultural understanding. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander agencies can liaise between departments and carers (or potential carers) to address the shortfalls that come with non-Indigenous models of recruitment, assessment and support for carers and suggest alternatives that are more suitable for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Ongoing education and cultural awareness training and supports for non-Indigenous carers and practitioners should be improved to enhance their knowledge and skills to work with Indigenous families and provide cultural care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. For example, supporting non-Indigenous carers to provide enhanced cultural care through designated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers or links to communities to provide connections to cultural practices and events for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people in their care.

Conclusion

The importance of children retaining cultural identity and connection has been well illustrated through the tragic impacts of past policies that involved the severing of those connections. The Principle was developed from this understanding; however, the implementation of the Principle has been beset by many systemic and practice challenges. Given that these challenges are experienced by all Australian jurisdictions, there is great promise in taking a national approach to child protection action and reform on this issue.

While its inclusion in legislation is an essential step towards improving the outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, the Principle, in and of itself, particularly when interpreted narrowly as a hierarchy of placement options for Aboriginal children, will be of limited value unless the appropriate monitoring and strategies are in place to support its implementation and assess the outcomes for children (Valentine & Gray, 2006). The broader intent of the Principle needs to be supported through a suite of strategies that include funding, training, planning, cultural recognition and inclusion, and strengthened in legislation and policy, including the focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children's best interests and safety. The current reform processes taking place in child protection systems across Australia may provide just the context in which innovation in Indigenous child welfare could be harnessed and scaled up to promote a new way of working together.

References

- Ah Kee, M., & Tilbury, C. (1999). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child placement principle is about self determination. Children Australia, 24(3), 4-8.

- Allard, T. (2010). Understanding and preventing Indigenous offending. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Arney, F. (2010). Promoting the wellbeing of young Aboriginal children. Public Health Bulletin SA, 7(3), 23-27.

- Arney, F., Lewig, K., Salveron, M., McLaren, H., Gibson, C., & Scott, D. (2010). Spreading promising ideas and innovations in child and family services. In F. Arney & D. Scott (Eds.), Working With Vulnerable Families: A Partnership Approach (pp. 275-293). Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011 (No. 3238.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from <www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/3238.0.55.001>.

- Australian Centre for Child Protection. (2013a). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle Workshop summary. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

- Australian Centre for Child Protection. (2013b). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle: Discussion paper prepared for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle Workshop. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2014). Child protection and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2014). Child Protection Australia 2012-13 Child Welfare Series. ACT: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Ban, P. (2005). Aboriginal child placement principle and family group conferences. Australian Social Work, 58(4), 384-394.

- Barnsdale, L., & Walker, M. (2007). Examining the use and impact of family group conferencing (S. W. R. Centre, Trans.). Stirling: University of Stirling.

- Blacklock, S., Arney, F., Menzies, K., Bonser, G., & Hayden, P. (2014). Transforming evidence and practice to promote connection for Aboriginal children, their families and communities. Paper presented at the 2014 Association of Children's Welfare Agencies (ACWA) Conference, Sydney.

- Bromfield, L. M., Arney, F., & Higgins, D. J. (2014). Contemporary issues in child protection intake, referral and family support. In A. Hayes & D. J. Higgins (Eds.), Families, policy and the law: Selected essays on contemporary issues for Australia. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Bromfield, L. M., Higgins, J. R., Higgins, D. J., & Richardson, N. (2007). Why is there a shortage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Carers? Perspectives of professionals from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, non-government agencies and government departments. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Bromfield, L. M., & Osborn, A. L. (2007). Kinship care (NCPC Brief No. 10). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Brown, L. (2003). Mainstream or margin? The current use of family group conferences in child welfare practice in the UK. Child and Family Social Work, 8(4), 331-340.

- Commission for Children and Young People and Child Guardian. (2014). Indigenous Child Placement Principle audit report 2012/13. Brisbane: Commission for Children and Young People and Child Guardian.

- Connolly, M. (2007). Family group conferences in child welfare. Developing Practice, 19, 25-33.

- Connolly, M. (2010). Engaging family members in decision-making in child welfare contexts. In F. Arney & D. Scott (Eds.), Working with vulnerable families: A partnership approach (pp. 209-266). Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Council of Australian Governments. (2009). Protecting children is everyone's business: National framework for protecting Australia's children 2009-2020. Canberra: Council of Australian Governments.

- Crime and Misconduct Commission. (2004). Protecting Children: An Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Foster Care. Brisbane: Crime and Misconduct Commission.

- Cummins, P., Scott, D., & Scales, B. (2012). Report of the Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry. Melbourne: Department of Premier and Cabinet.

- De Lisi, M., & Vaughn, M. G. (2011). The importance of neuropsychological deficits relating to self-control and temperament to the prevention of serious antisocial behaviour. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 1-2, 12-35.

- Department of Education and Child Development. (2014). The removal of many Aboriginal children. Adelaide: Department of Education and Child Development.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2011). An outline of the National Standards for Out-of-Home Care: A priority project under the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services, and Indigenous Affairs. (2012). A Report on consultations carried out by the Department of Families, Communities and Indigenous Affairs with Indigenous care organisations under the National Framework of Protecting Australia's Children. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Human Services. (2007). Aboriginal family preservation and restoration. Melbourne: Department of Human Services.

- Dudgeon, P., Wright, M., Paradies, Y., Garvey, D., & Walker, I. (2010). The social, cultural and historical context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. In P. Dudgeon, H. Milroy, & R. Walker. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice, (pp. 25-42). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Family Matters. (2014). Family Matter: Kids safe in culture not in care. South Australian report. Adelaide: Family Matters.

- Haebich, A. (2000). Broken circles: Fragmenting Indigenous families 1800-2000. Fremantle, Perth: Arts Centre Press.

- Harris, N. (2008). Family group conferencing in Australia 15 years on. Child Abuse Prevention Issues, 27.

- Higgins, D. J., Bromfield, L. M., & Richardson, N. (2005). Enhancing out-of-home care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. (1997). Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry Into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children From Their Families. Canberra: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

- Johnston, E. (1991). Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, National report. Volumes 1 to 5. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Lange, S., Shield, K., Rehm, J., & Popova, S. (2013). Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in child care settings: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(4), e980-e995.

- Lewis, N., and Burton, J. (2014). Keeping kids safe at home is key to preventing institutional abuse. Indigenous Law Bulletin, 8(13), 11-14.

- Libesman, T. (2011). Cultural care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out of home care. Fitzroy, Melbourne: Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC).

- Libesman, T. (2014). Decolonising Indigenous child welfare: Comparative perspectives (1st ed.). Oxford and New York: Routledge.

- Linqage International. (2003). A.T.S.I. Family Decision Making Program evaluation: "Approaching Families Together 2002". Melbourne: Victorian Department of Human Services.

- Litwin, J. (1997). Child protection interventions within Indigenous communities: An "anthropological" perspective. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 32(4), 317-340.

- Lock, J. A. (1997). The Aboriginal Child Placement Principle: Research project no. 7. Sydney: New South Wales Law Reform Commission.

- Lohoar, S., Butera, N., & Kennedy, E. (2014). Strengths of Australian Aboriginal cultural practices in family life and child rearing. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- McGuinness, K., & Arney, F. (2012). Foster and kinship care recruitment campaign literature review. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

- McGuinness, K., & Leckning, B. (2013). Bicultural practice in the Northern Territory children and families sector. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

- McHugh, M. (2011). A review of foster carer allowances: Responding to Recommendation 16.9 of the Special Commission of Inquiry into Child Protection (NSW). Children Australia, 36(1), 18-25. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1375/jcas.36.1.18

- Northern Territory Government. (2010). Growing Them Strong, Together: Promoting the safety and wellbeing of the Northern Territory's children, Report of the Board of Inquiry into the Child Protection System in the Northern Territory 2010, M.Bamblett, H. Bath and R. Roseby. Darwin, NT: Northern Territory Government.

- Productivity Commission. (2015). Report on government services. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Protection Peak. (2011). Losing ground: A report on the adherence to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle in Queensland. Brisbane: Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Protection Peak.

- Richardson, N., Bromfield, L. M., & Higgins, D. J. (2005). The recruitment, retention and support of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander foster carers: A literature review. Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Richardson, N., Bromfield, L. M., & Osborn, A. (2007). Cultural considerations in out of home care. Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Rodgers, A., & Cahn, K. (2010). Involving families in decision making in child welfare: A review of the literature. Portland: Portland State University.

- Sawyer, M., Carbone, J. A., Searle, A., & Robinson, P. (2007). The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home-based foster care. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(4), 181-184.

- SNAICC. (2005). Footprints to where we are: A resource manual for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children's services. Melbourne: Secretariat for National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care.

- SNAICC. (2012). Healing in practice: Promising practices in healing programs. Melbourne: Secretariat for National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care.

- SNAICC. (2013). Whose voice counts? Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in child protection decision-making. Melbourne: Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care.

- Spence, N. (2004). Kinship care in Australia. Child Abuse Review, 13(4), 263-276.

- Sundell, K., & Vinnerljung, B. (2004). Outcomes of family group conferencing in Sweden: A 3-year follow-up. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 267-287.

- Tilbury, C., Burton, J., Sydenham, E., Boss, R., & Louw, T. (2013). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle: Aims and core elements. Melbourne: Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC).

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2012). Committee on the Rights of the Child, Sixtieth session 29th May-15th June 2012.

- Valentine, B., & Gray, M. (2006). International perspectives on foster care: Keeping them home. Aboriginal out-of-home care in Australia. Families in Society, 87(4), 537-545.