The intersection between the child protection and youth justice systems

July 2018

Adam Dean

Download Policy and practice paper

Overview

This resource sheet summarises data that link the child protection system and youth justice supervision in Australia, with a focus on those groups who are over-represented in the youth justice system. It presents an overview of the number of young people under youth justice supervision and young people involved in both the youth justice and child protection systems.1 Recent research on the link between child maltreatment and youth offending is also summarised. While this resource sheet discusses some aspects of the child protection system, it does not provide an overview of child protection or child maltreatment statistics.

1 For the purposes of this resource sheet, young people refers to people aged 10–17 years in Australia unless otherwise stated.

Introduction

In 2015/16,2 one in every 476 young people aged 10–17 years in Australia were under youth justice supervision on an average day. Males, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds were significantly over-represented among those under youth justice supervision.

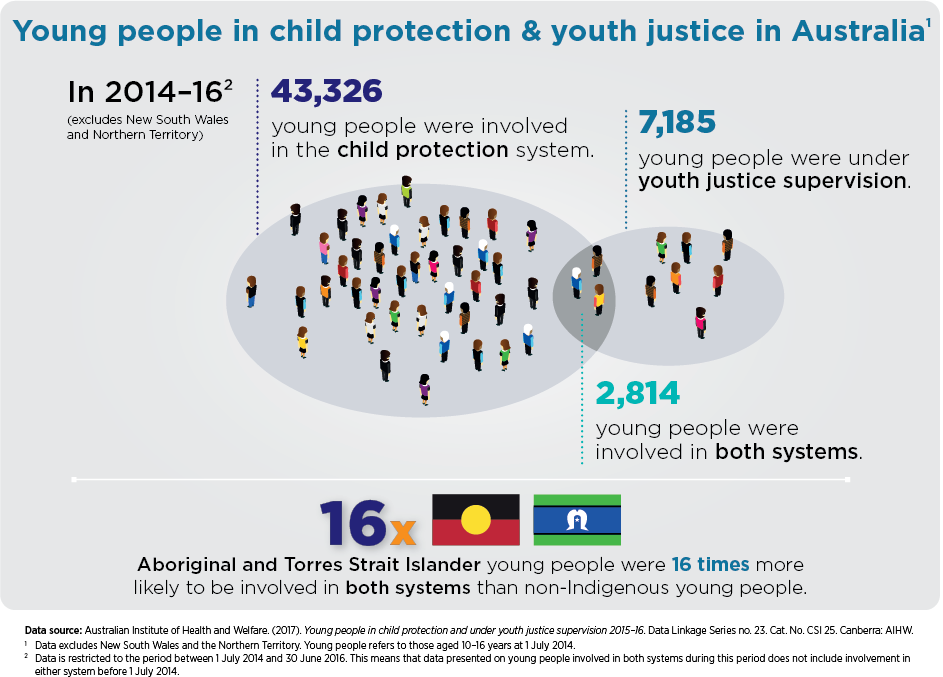

Young people involved in the child protection system were similarly over-represented in the youth justice system. In the period from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2016, young people involved in the child protection system were 12 times more likely to also be under youth justice supervision than the general population. During the same period, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people were 16 times more likely to be involved in both systems than non-Indigenous young people. Young people with a history of maltreatment are particularly vulnerable to coming into contact with the criminal justice system. Those who do often have a range of complex needs, including developmental trauma and problem behaviours.

Note:

At the time of writing, data that links child protection and youth justice systems are available for all Australian states and territories, except New South Wales and the Northern Territory where datasets are not yet linked.

The data presented in this resource sheet are based on two Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) reports:

- Youth Justice in Australia 2015–16 (2017a)

- Young People in Child Protection and Under Youth Justice Supervision 2015–16 (2017b)

This resource sheet is updated annually once both datasets are available. Please check the AIHW website for recent updates to the datasets.

2 Periods stated in this resource sheet represent financial years beginning 1 July of the first year and ending 30 June of the following year, unless otherwise stated.

Youth justice supervision

This section gives a brief overview of the youth justice system in Australia with a particular focus on youth justice supervision. It summarises data collected on types of youth justice supervision, including rates of young people under supervision by state and territory, sex and age, Indigenous status, remoteness and socio-economic position.

Youth justice system

In Australia, the youth justice system refers to the 'set of processes and practices for managing children and young people who have committed, or allegedly committed, an offence' (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2017a, p. 3). In all states and territories, young people aged 10 years and older may be charged with an offence.3 Youth justice is typically restricted to young people aged 10–17 in Australia, though some exceptions apply.4 Until recently, youth justice in Queensland was restricted to young people aged 10–16 years. However, legislation enacted in February 2018 means that 17 year olds are now included in Queensland's youth justice system (Department of Justice and Attorney-General, 2017).5

Types of youth justice supervision

There are two main types of youth justice supervision:

- Community-based supervision: Young people who live in the community and are supervised by the youth justice department.

- Detention: Young people who are detained in a youth justice centre or detention facility.

Within these two types of supervision, young people can be under either unsentenced legal orders (charged with an offence, or found or pleaded guilty, but waiting to be sentenced) or sentenced legal orders (proven guilty in court and sentenced).

| Community-based | Detention | |

|---|---|---|

| Unsentenced supervision | Home-detention bail: supervised or conditional bail | Remanded in custody (can be police or court referred) |

| Sentenced supervision | Parole or supervised release, probation or similar suspended detention | Sentenced to detention |

Source: AIHW, 2017a

On an average day in 2015/16, most young people in community-based supervision were under sentenced legal orders, while most of those in detention were under unsentenced legal orders, although this varies by jurisdiction. In each state and territory, legislation is based on the principle that young people should be placed in detention only as a last resort, which contributes to the higher proportion of young people supervised in the community than in detention (AIHW, 2017a).

Box 1: Measures used for numbers of young people under supervision

In reporting the numbers of young people under supervision, two types of measures are used:

- An 'average day' is the number of young people under supervision on any given day during a financial year. It is calculated by dividing the total number of days each young person spends under supervision by the number of days in a year.

- 'During the year' is the total number of individuals who were supervised at any time during a financial year, regardless of how many times they entered and exited the system.

In reviewing the data on youth justice supervision in Australia, it is important to note that differences in legislation, policies and practices between jurisdictions may affect the rates of young people under supervision and data collection processes, which means that the rates of youth justice involvement may not be directly comparable between states and territories (AIHW, 2017a).6

See 'Technical notes' of the AIHW report (2017a, p. 20) for more details.

Numbers of young people under supervision

The number of supervised young people varies by state and territory, age and sex, Indigenous status, remoteness and socio-economic position. In 2015/16, a total of 11,007 young people aged 10 years and older were under youth justice supervision at some point during the year. However, this is a smaller number (9,544) when restricted to young people aged 10–17 years for whom the youth justice system is typically restricted.7

Due to movements in and out of the system, about half of this number of young people aged 10–17 years (4,821) were under supervision on an average day. This equates to about one in every 476 young people in Australia. On an average day, most young people under supervision were under community-based supervision (84%), with the remainder in detention (17%).8 Over the course of the year, 44% of all supervised young people were in detention at some point.

In 2015/16, supervised young people spent, on average, a total of 182 days (about six months) under supervision. This varies by supervision type, where periods are typically longer in community-based supervision (an average of 171 days) than for detention (an average of 69 days).

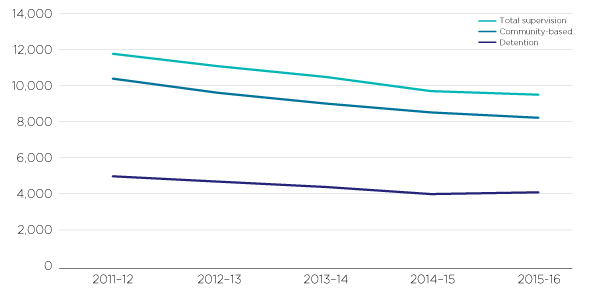

As shown in Figure 1, the total number of young people aged 10–17 years under supervision during a year decreased in the five-year period from 2011/12 to 2015/16 from 11,861 to 9,544. The rate of young people under supervision during a year dropped from 52.7 young people per 10,000 to 41.5 per 10,000.

Figure 1: Young people aged 10–17 years under supervision during the year in Australia, 2011/12 to 2015/16

Notes: 1. The Northern Territory did not supply Juvenile Justice National Minimum Data Set (JJ NMDS) data for 2008/09 to 2015/16. 2. Includes non-standard data for the Northern Territory for 2011/12 to 2015/16. 3. Trend data may differ from those previously published due to data revisions. 4. Age calculated as at start of financial year if first period of community-based supervision in the relevant year began before the start of the financial year, otherwise age calculated as at start of first period of community-based supervision in the relevant year.

Source: Tables S10b, S45b and S83b (AIHW, 2017a)

States and territories

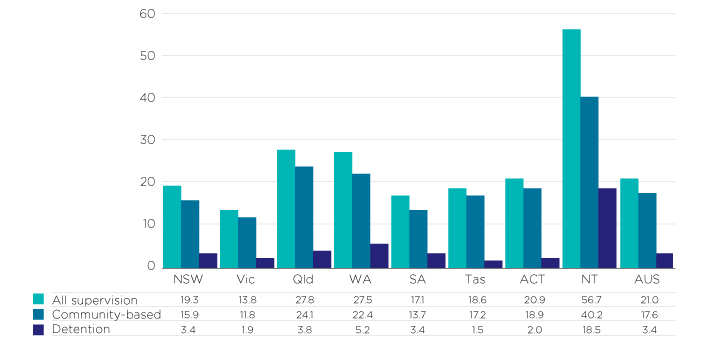

As shown in Figure 2, on an average day in 2015/16, 21 in every 10,000 young people aged 10–17 were under some form of supervision: 17.6 per 10,000 were in community supervision and 3.4 per 10,000 were in detention. These rates vary by jurisdiction, ranging from 13.8 per 10,000 in Victoria to 56.7 per 10,000 in the Northern Territory (AIHW, 2017a).

Figure 2: Rates of young people aged 10–17 under supervision on an average day in 2015/16 by jurisdiction.

Notes: 1. Rates are number of young people per 10,000 relevant population. 2.The Northern Territory did not supply JJ NMDS data for 2015/16. 3. Includes non-standard data for the Northern Territory.

Source: Tables S4a, S39a and S77a (AIHW, 2017a)

In terms of total numbers rather than rates, New South Wales had the highest number of young people under supervision on an average day (1,494), followed by Queensland (1,466) and Victoria (1,084) (AIHW, 2017a, p. 5).

Sex and age

Males are over-represented in youth justice supervision. Most young people under supervision on an average day in 2015/16 were male (82.5%), ranging from 74% in the Australian Capital Territory to 87% in Tasmania (AIHW, 2017a). Males were about four times more likely to be under supervision than females on an average day.

Most young people under supervision were aged 14–17 (79%), with 16 year olds representing the highest number (1,364) and rates (47 per 10,000) of all age groups. Young people aged 10–13 years represented 9% of young people under supervision and those aged 18 or older represented 12%. Again, this varies by state and territory, which is partly due to differences in processes between jurisdictions.

The difference between males and females in offending behaviours—typically known as the gender gap in crime—has been a topic of sustained research and theoretical debate (Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996). Researchers have largely focused on various social and cultural factors that influence male and female behaviours to help explain the gender gap in crime (Gault-Sherman, 2013; Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996). For example, Steffensmeier and Allan (1996) explain this gender difference in terms of what limits female offending but encourages male offending. This approach focuses on how differences between males and females in gender roles, social pressures, physical strength (perceived or actual), and opportunities to offend mean that females are less likely to offend than males and are far less likely to be involved in serious crimes (e.g. violent crimes) than males.

Based on their review of the evidence, Kerig and Becker (2015) suggest that females may engage in more covert forms of antisocial or offending behaviours that avoid the attention of legal authorities. Other researchers have offered alternative explanations for the gender gap that have focused on developmental differences between males and females that occur during adolescence and early adulthood (Shulman, Harden, Chein, & Steinberg, 2015). In their analysis of longitudinal data, Shulman and colleagues (2015) found that males have higher levels of sensation seeking (e.g. desire for new and exciting experiences) and lower impulse control than females during adolescence and early adulthood, which suggests that young males engage in riskier behaviours and with less self-control than young females.

Indigenous young people

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are over-represented in youth justice supervision. On an average day in 2015/16, Indigenous young people were 17 times more likely than non-Indigenous young people to be under supervision. Indigenous young people represented 48% of all young people under supervision, despite representing less than 6% of all young people in Australia. This is even higher for those in detention where more than half of young people were Indigenous (59%), making them 25 times more likely to be in detention than non-Indigenous young people.

Indigenous over-representation in youth justice supervision varied by jurisdiction, with Tasmania recording the lowest rate of over-representation (three times more likely) and Western Australia recording the highest (27 times more likely). While the overall proportion of Indigenous young people under supervision has decreased between 2011/12 and 2015/16 from 203 to 184 per 10,000, it has decreased at a slower rate than for non-Indigenous young people. This means that Indigenous over-representation has increased during this period (AIHW, 2017a), despite total numbers decreasing (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The over-representation of Indigenous young people under youth justice supervision

Notes: 1. The Northern Territory did not supply JJ NMDS data for 2011/12 to 2015/16. 2. Includes non-standard data for the Northern Territory for 2011/12 to 2015/16. 3. Trend data may differ from those previously published due to data revisions. 4. Rates are number of young people per 10,000 relevant population.

Source: Table S12a (AIHW, 2017a)

Box 2: Why are Indigenous young people over-represented in the youth justice system?

The reasons why Indigenous young people are over-represented in the youth justice system are multiple and complex, and include a range of social and economic disadvantages (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, 2011; Muirhead & Johnston, 1991; Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017). This over-representation can be considered on two inter-related levels:

- offending patterns and criminal justice system responses

- underlying issues contributing to offending patterns and criminal justice responses.

When considering offending patterns and criminal justice responses, some factors that contribute to over-representation (Blagg, Morgan, Cunneen, & Ferrante, 2005; Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017) include:

- offending behaviours that are more likely to lead to imprisonment or supervision for Indigenous young people compared to non-Indigenous young people

- a greater likelihood of coming into contact with police and justice systems for Indigenous peoples, including the over-policing of Aboriginal communities

- legislation that has a disproportionate impact on Indigenous young people than non-Indigenous young people, such as mandatory sentencing laws for property offences

- lower levels of access to legal or other social support services for Indigenous peoples.

When considering the underlying issues contributing to offending patterns and criminal justice responses, a range of social, economic and cultural disadvantages experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be identified (Muirhead & Johnston, 1991; Productivity Commission, 2016; Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017). More fundamentally, these disadvantages are widely recognised as the continuing effects of colonisation and a history of government policies of segregation, assimilation and control (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission [HREOC], 1997; Muirhead & Johnston, 1991). These issues (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, 2011; HREOC, 1997; Productivity Commission, 2016; Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017) include:

- loss of autonomy and disempowerment

- systemic racism

- intergenerational trauma resulting from forced removals of Aboriginal children from their families

- high rates of poverty

- lower levels of education and employment

- high rates of mental illness

- high rates of substance abuse

- high rates of child maltreatment and family violence

- high rates of involvement in the child protection system.

These underlying issues and their complex interactions mean that Indigenous young people are at greater risk of offending and coming into contact with the criminal justice system than non-Indigenous young people.

For information about what works to reduce Indigenous over-representation in the criminal justice system, see the Doing Time – Time For Doing report (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, 2011).

Remoteness and socio-economic position

Young people from geographically remote areas9 and low socio-economic positions10 are over-represented in youth justice supervision. On an average day in 2015–16, young people from remote areas were six times more likely to be under youth justice supervision than those from major cities (89 per 10,000 compared to 14 per 10,000). This is even greater for very remote areas, where young people are 10 times more likely to be under youth justice supervision (139 per 10,000). Similarly, young people from the lowest socio-economic areas were about six times more likely to be under supervision compared to those from the highest socio-economic areas (38 per 10,000 compared to six per 10,000).

Similar to the gender gap, discussed above, the relationship between socio-economic disadvantage and offending is a topic of debate among researchers. Some have argued that socio-economic disadvantage weakens a community's ability to control anti-social behaviours in their neighbourhood, while others have argued that it weakens the capacity of parents to provide quality parenting (Weatherburn & Lind, 2006). In their analysis of New South Wales data, Weatherburn and Lind (2006) argue that socio-economic disadvantage weakens both community capacity and parenting quality in ways that increase the prevalence of child neglect, which in turn leads to greater offending behaviours (see What is the link between child maltreatment and youth offending?).

3 In its final report, the Royal Commission and Board of Inquiry into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory recommended that ‘Section 38(1) of the Criminal Code Act (NT) be amended to provide that the age of criminal responsibility be 12 years’ (Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017, p. 46). However, at the time of writing, legislation to raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 years to 12 years has not changed in the Northern Territory.

4 As noted in AIHW (2017a): ‘Some young people aged 18 and older are also involved in the youth justice system. This may be due to the offence being committed when the young person was aged 17 or younger, the continuation of supervision once they turn 18, or in some cases because of vulnerability or immaturity. Also, in Victoria, some young people aged 18–20 may be sentenced to detention in a youth facility under the state’s ‘dual track’ sentencing system, which is intended to prevent young people from entering the adult prison system at an early age.’ (p. 3).

5 For more information, see the Queensland Government website: http://justice.qld.gov.au/corporate/business-areas/youth-justice/inclusion-of-17-year-old-persons

6 For more details, see information on the Juvenile Justice National Minimum Data Set available on the AIHW website.

7 Because the youth justice system is typically restricted to young people aged 10–17 years, this resource sheet focuses particularly on this cohort.

8 Total percentages presented in this section do not always equal 100% due to rounding and the fact that young people may be under both types of supervision on the same day (AIHW, 2017a, p. 5).

9 AIHW data on remoteness uses the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) Remoteness Structure developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). These areas are Major cities, Inner regional, Outer regional, Remote and Very remote. More information on the ASGC Remoteness Structure is available on the ABS website.

10 AIHW data on socio-economic position uses the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) that the ABS has developed to analyse the socio-economic position of the usual residence of young people under supervision. The Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage is used. More information is available on the ABS website.

The overlap between child protection and youth justice

This section summarises data collected by child protection and youth justice agencies, and linked by the AIHW. This data is presented from two perspectives:

- young people in child protection who were also under supervision

- young people under supervision who were also involved in child protection.

Linked data are currently available for all jurisdictions except New South Wales and the Northern Territory and are restricted to people who were aged 10–16 years at 1 July 2014.

The data on the overlap between the child protection system and youth justice supervision are restricted to the period between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2016. Data presented on young people involved in both systems during this period do not include young people involved in either system before 1 July 2014. For example, a young person who was in the child protection system before 1 July 2014 and then was under youth justice supervision during 2014–16 would not be captured in this data. Over time, the longitudinal data collected via these linked data sets will allow for a more comprehensive analysis of young people's involvement in both systems over the course of their childhood and adolescence (AIHW, 2017b).

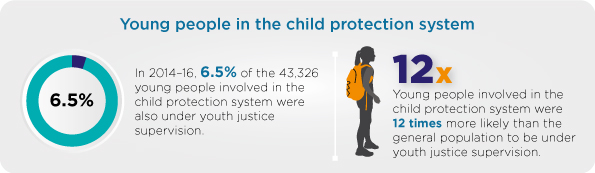

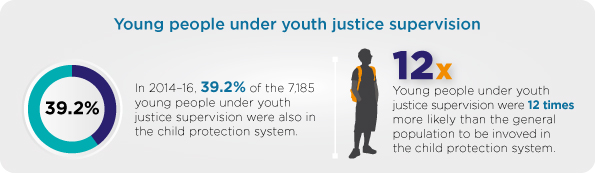

In this 2014–16 period, 2,814 out of the 7,185 (39.2%) young people under youth justice supervision were also involved in the child protection system. This represents 6.5% of young people involved in the child protection system during this period. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people were 16 times more likely to be involved in both systems than non-Indigenous young people (AIHW, 2017b). This is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: The overlap between the child protection system and youth justice supervision, 2014–16

Notes: 1 Young people refers to those aged 10–16 years at 1 July 2014. 2 Data are restricted to the period between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2016. This means that data presented on young people involved in both systems during this period do not include involvement in either system before 1 July 2014.

Source: Diagram adapted from AIHW (2017b)

Young people in child protection who were also under supervision

A relatively small proportion of young people involved in the child protection system were also under youth justice supervision during 2014–16. Young people involved in the child protection system refers to those who were:

- subject to an investigated notification (either substantiated or unsubstantiated investigations)

- subject to a care and protection order

or - in out-of-home care.11

Figure 5: Young people in child protection who were also under youth justice supervision, 2014–16

Notes: Young people refers to those aged 10–16 years at 1 July 2014. Data are restricted to the period between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2016. This means that data presented on young people involved in both systems during this period do not include involvement in either system before 1 July 2014.

Source: Diagram adapted from AIHW (2017b)

Of the 43,326 young people aged 10–16 years involved in the child protection system during 2014–16, 6.5% were also under youth justice supervision in the same period. Overall, young people involved in child protection were 12 times more likely than the general population to be under youth justice supervision (AIHW, 2017b). Both Indigenous young people and males were over-represented within this population.

Within this group of young people involved in the child protection system and also under youth justice supervision the percentage:

- subject of an investigated notification was 5.7%

- subject of a care and protection order was 10.4%

- in out-of-home care was 10.2%.

These types of involvement with the child protection system are discussed in more detail below, with definitions adapted from the Young People in Child Protection and Under Youth Justice Supervision 2015–16 report (AIHW, 2017b).

Investigated notifications

Notifications received by child protection departments of possible abuse, neglect or other harm, which are then investigated to find whether a child has been maltreated or is at imminent risk of maltreatment, in which case, the notification will be substantiated or unsubstantiated.

During 2014–16, 33,383 young people aged 10–16 years were the subject of an investigated notification (including both substantiated and unsubstantiated outcomes) under the child protection system for the jurisdictions presented in the data. Of these young people, 5.7% were also under youth justice supervision in the same period. This is 11 times the rate of the general population of the same age. Indigenous young people who were subject to an investigated notification were more likely to also be under youth justice supervision in this period than non-Indigenous young people: 18.9% of Indigenous males and 8.2% of Indigenous females, compared to 6.2% of non-Indigenous males and 2.2% of non-Indigenous females.

There was also a difference between substantiated and unsubstantiated investigations: 8.7% of those with a substantiated investigation were also under supervision compared to 4.9% of those with unsubstantiated investigations.

Care and protection orders

Legal orders or arrangements that give child protection departments some responsibility for a child's welfare.

During 2014–16, 13,982 young people aged 10–16 years were the subject of a care and protection order in the jurisdictions represented in the data. Of these young people, 10.4% were also under youth justice supervision during the same period. This is 19 times the rate of the general population of the same age. For males, both Indigenous (19.4%) and non-Indigenous (12%), the rate was higher. Similarly, Indigenous females were much more likely to be under supervision (10%) than non-Indigenous females (5.3%).

Out-of-home care

Arrangements where children are placed in care for which the department has made or offered a financial payment to the carer, in cases when parents cannot give adequate care, children need a more protective environment, or other accommodation is needed during family conflict.

During 2014–16, 11,999 young people aged 10–16 years were in out-of-home care in the jurisdictions represented in the data. Of these young people, 10.2% were also under youth justice supervision during the same period. This is 19 times the rate of the general population of the same age. For Indigenous males this rate was much higher (17.8%) compared to non-Indigenous males (12%). Similarly, Indigenous females in out-of-home care were much more likely to be under youth justice supervision (9.9%) than non-Indigenous females (5.6%), who were less likely to be under youth justice supervision among those in out-of-home care.

Young people under supervision who were also involved in child protection

At some point in 2014–16, 7,185 young people aged 10–16 years were under youth supervision (as noted above, this data excludes New South Wales and the Northern Territory). Of these young people, 39.2% were also involved in the child protection system during the same period. This is 12 times the rate of the general population of the same age. As noted above, there are two types of supervision – community-based supervision and detention – and young people may have been under one or both of these types of supervision during the two-year period reported. These types of supervision are discussed in more detail below, with definitions adapted from the Young People in Child Protection and Under Youth Justice Supervision 2015–16 report (AIHW, 2017b).

Figure 6: Young people under youth justice supervision who were also involved in the child protection system, 2014–16

Notes: Young people refers to those aged 10–16 years at 1 July 2014. Data are restricted to the period between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2016. This means that data presented on young people involved in both systems during this period do not include involvement in either system before 1 July 2014.

Source: Diagram adapted from AIHW (2017b)

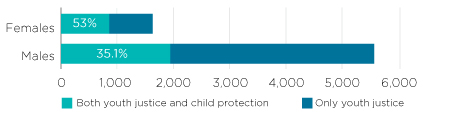

During this period, females under youth justice supervision were more likely to have been involved in the child protection system (53%) than males (35.1%) (see Figure 7). While the available research shows gender differences in risks for offending, patterns of offending and the impact of out-of-home care and adverse childhood experiences that may contribute to this difference (AIHW, 2017b; Forrest & Edwards, 2015; Goodkind, Shook, Kim, Pohlig, & Herring, 2013; Malvaso & Delfabbro, 2015; Malvaso, Delfabbro, Day, & Nobes, 2018), the research literature is unclear about what accounts for the greater proportion of females involved in both systems among those under youth justice supervision compared to males.

Figure 7: Number of young people under youth justice supervision by involvement in the child protection system, 1 July 2014–30 June 2016

There were small differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people under youth justice supervision who were also involved in the child protection system (40.5% compared to 38.5% respectively).

Community-based supervision

Young people who live in the community and are supervised by the youth justice department.

In 2014–16, 6,543 young people aged 10–16 years were under youth justice community-based supervision in the jurisdictions represented in the data. Of these young people, 39.2% were also involved in the child protection system during the same period. This is 12 times the rate of the general population. Females in community-based supervision were more likely to have also been involved in the child protection system during this period than males: 52.4% of Indigenous females and 54.5% of non-Indigenous females compared to 37% of Indigenous males and 34.2% of non-Indigenous males.

Detention

Young people who are detained in a youth justice centre or detention facility.

In 2014–16, 3,769 young people aged 10–16 years were in detention in the jurisdictions represented in the data. Of these young people, 43.4% were also involved in the child protection system in the same period. This is 13 times the rate of the general population. Similar to community-based supervision, those in detention who were also involved in the child protection system were more likely to be female (58.2%) than male (39.7%).

There were small differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people when comparing those in detention who were also in the child protection system: 42.6% of Indigenous young people compared with 44.5% of non-Indigenous young people.

Age at first youth justice supervision

Younger adolescents entering youth justice supervision for the first time during the 2014–16 period were significantly more likely to be involved in the child protection system than older adolescents. Of those aged 10 years entering youth justice supervision for the first time, 62.3% were also involved in the child protection system, compared to 16.7% of those aged 17 years.

11 For the purposes of this resource, involvement in the child protection system refers to investigated notifications, care and protection orders and out-of-home care placements. This excludes “notifications that were not investigated, care and protection orders that were ‘other’ or ‘not stated’, and living arrangements that do not constitute out-of-home care” (AIHW, 2017b, p. 3).

What is the link between child maltreatment and youth offending?

A strong body of evidence demonstrates a link between child maltreatment and youth offending – often termed the maltreatment–offending association (Cashmore, 2011; Hurren, Stewart, & Dennison, 2017; Malvaso, Delfabbro, & Day, 2016). It finds that children and young people with a history of abuse or neglect are at increased risk of engaging in offending behaviours than those without a history of maltreatment. It does not suggest that all maltreated children and young people will engage in offending behaviours – the majority do not – but it does show that they are more likely to come into contact with the youth justice system compared to the general population.

Young people involved in both the child protection system and under youth justice supervision are generally recognised as having a range of complex needs, including developmental trauma, problem behaviours and mental health difficulties among others (Bollinger, Scott-Smith & Mendes, 2017; Malvaso & Delfabbro, 2015; Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017).

The maltreatment–offending association is complex. It can involve a range of factors that influence the risk of subsequent offending behaviour, including variations in the maltreatment experiences and placement in out-of-home care. Furthermore, other individual, social and contextual factors have been found to mediate or moderate risks associated with maltreatment and out-of-home care experiences (Malvaso et al., 2016). These are outlined in more detail below.

Maltreatment experiences

Studies on the maltreatment–offending association have largely focused on how variations in the type, timing and recurrence of maltreatment influence the development of offending behaviours (Malvaso et al., 2016; Malvaso, Delfabbro, & Day, 2017). In their systematic review of longitudinal studies, Malvaso and colleagues (2016) found that all types of maltreatment – physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and neglect – have been found to be associated with offending (see also Malvaso et al., 2017). However, while all types of maltreatment increase this risk, the effect that any particular type has on offending behaviours is inconsistent. For example, some studies show that physical abuse increases the risk of violent crime, while others find it has a stronger association with non-violent crime (Malvaso et al., 2016). These findings suggest that the trauma and stress associated with any experience of maltreatment, regardless of type, might be more important in explaining why young people who have been maltreated are more likely to offend.

The maltreatment–offending association can also be influenced by the timing of maltreatment – for example, abuse or neglect that occurs in early childhood, middle childhood or adolescence – and its recurrence over time. Several studies indicate that children who experience frequent maltreatment that persists over time and peaks in adolescence are at a greater risk of offending (Cashmore, 2011; Hurren et al., 2017; Malvaso et al., 2017). More generally, Malvaso and colleagues (2016) found evidence that the risk of offending increases with age of maltreatment substantiation.

Out-of-home care experiences

The maltreatment–offending association can also be influenced by children and young people's out-of-home care experiences. While placement in out-of-home care can help reduce the risk of offending, in some cases this risk can be exacerbated. Placement in residential care, placement instability and young people transitioning from care to independence are common factors that are associated with an increased risk of offending for maltreated young people (Malvaso & Delfabbro, 2015; Malvaso et al., 2016; Mendes, Baidawi, & Snow, 2014; Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017; Victoria Legal Aid, 2016). For example, residential care may increase the risk of offending due to the co-location of young people with problem behaviours, greater contact with police and the criminalisation of problem behaviours (also known as care-criminalisation) (Cashmore 2011; McFarlane, 2010; Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, 2017).

Other risk factors

Finally, a range of other risk factors can influence the maltreatment–offending association. These can include:

- individual risk factors (e.g. gender, age, ethnicity, lower levels of education, mental health difficulties, substance misuse, trauma, developmental delays, problem behaviours, homelessness)

- social risk factors (e.g. parent–child relationships, family structure, family poverty)

- contextual risk factors (e.g. social disadvantage, neighbourhood poverty, community violence) (AIHW, 2016; Bollinger et al., 2017; Malvaso et al., 2016).

Where present, such risk factors can help to explain why some maltreatment and out-of-home care experiences increase the risk of young people offending. As noted above, the available evidence suggests (Malvaso et al., 2016; Malvaso, Delfabbro, & Day, 2017) that the complex interaction between individual, social and contextual risk factors with maltreatment and out-of-home care experiences can significantly influence the development of offending behaviours for young people and their risk of coming into contact with the criminal justice system.

The maltreatment–offending association highlights the complex range of factors involved for maltreated children and young people that contribute to their increased risk of offending.

Conclusion

Young people in the child protection system are much more likely to be under youth justice supervision than the general population. The reasons for this are multiple and complex, and involve a range of risk factors including a history of maltreatment, social disadvantage, out-of-home care experiences, trauma and developmental delays.

While only a minority of young people involved in the child protection system were also under youth justice supervision in 2014–16, those who were represent a comparatively high proportion of the total number under youth justice supervision.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2016). Vulnerable young people: Interactions across homelessness, youth justice and child protection – 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2015. Cat. no. HOU 279. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW. (2017a). Youth Justice in Australia 2015–16. Bulletin 139. Cat. No. AUS 211. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW. (2017b). Young people in child protection and under youth justice supervision 2015–16. Data Linkage Series no. 23. Cat. No. CSI 25. Canberra: AIHW.

- Blagg, H., Morgan, N., Cunneen, C., & Ferrante, A. (2005). Systemic racism as a factor in the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people in the Victorian criminal justice system. Melbourne: Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission.

- Bollinger, J., Scott-Smith, S., & Mendes, P. (2017). How complex developmental trauma, residential out-of-home care and contact with the justice system intersect. Children Australia, 1–5.

- Cashmore, J. (2011). The link between child maltreatment and adolescent offending: Systems neglect of adolescents. Family Matters, 89, 31–41.

- Department of Justice and Attorney-General. (2017). Inclusion of 17 year olds in the youth justice system. Brisbane: Department of Justice and Attorney-General.

- Forrest, W., & Edwards, B. (2015). Early onset of crime and delinquency among Australian children. In Australian Institute of Family Studies. (Eds.), The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children annual statistical report 2014 (pp. 131–150). Melbourne: AIFS.

- Gault-Sherman, M. (2013). The gender gap in delinquency: Does SES matter? Deviant Behavior, 34, 255–273.

- Goodkind, S., Shook, J. J., Kim, K. H., Pohlig, R. T., & Herring, D. J. (2013). From child welfare to juvenile justice: Race, gender, and system experiences. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 11, 249–272.

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs. (2011). Doing Time – Time for Doing: Indigenous youth in the criminal justice system. Canberra: Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC). (1997). Bringing Them Home. Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Sydney: HREOC.

- Hurren, E., Stewart, A., & Dennison, S. (2017). Transitions and turning points revisited: A replication to explore child maltreatment and youth offending links within and across Australian cohorts. Child Abuse & Neglect, 65, 24–26.

- Kerig, P. K., & Becker, S. P. (2015). Early abuse and neglect as risk factors for the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. In J. Morizot, & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Malvaso, C., & Delfabbro, P. (2015). Offending behaviour among young people with complex needs in the Australian out-of-home care system. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 24, 3561–3569.

- Malvaso, C. G., Delfabbro, P. H., & Day, A. (2016). Risk factors that influence the maltreatment–offending association: A systematic review of prospective and longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 1–15.

- Malvaso, C. G., Delfabbro, P. H., & Day, A. (2017). The child protection and juvenile justice nexus in Australia: A longitudinal examination of the relationship between maltreatment and offending. Child Abuse & Neglect, 64, 32–46.

- Malvaso, C. G., Delfabbro, P. H., Day, A., & Nobes, G. (2018). The maltreatment–violence link: Exploring the role of maltreatment experiences and other individual and social risk factors among young people who offend. Journal of Criminal Justice, 55, 25–45.

- McFarlane, K. (2010). From care to custody: Young women in out-of-home care in the criminal justice system. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 22, 345–353.

- Mendes, P., Baidawi, S., & Snow, P. C. (2014). Young people transitioning from out-of-home care in Victoria: Strengthening support services for dual clients of child protection and youth justice. Australian Social Work, 67(1), 6–23.

- Muirhead, J. H., & Johnston, E. (1991). Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody: National report. Canberra: Australian Government Public Service.

- Productivity Commission. (2016). Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key indicators 2016. Melbourne: Productivity Commission.

- Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory. (2017). Report of the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory. Canberra: Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory.

- Shulman, E. P., Harden, K. P., Chein, J. M., & Steinberg, L. (2015). Sex differences in the developmental trajectories of impulse control and sensation-seeking from early adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1–17.

- Steffensmeier, D., & Allan, E. (1996). Gender and crime: Toward a gendered theory of female offending. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 459–487.

- Victoria Legal Aid. (2016). Care not Custody: A new approach to keep kids in residential care out of the criminal justice system. Melbourne: Victoria Legal Aid.

- Weatherburn, D., & Lind, B. (2006). What mediates the macro-level effects of economic and social stress on crime? The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 39(3), 384–397.

This paper was authored by Adam Dean, Senior Research Officer with the Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) information exchange at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The author would like to thank Dr Catia Malvaso, Research Fellow at the School of Psychology, University of Adelaide, for reviewing this resource sheet.

Featured image: © GettyImages/Slonov