Rates of therapy use following a disclosure of child sexual abuse

June 2021

James Herbert

Download Policy and practice paper

Overview

Therapy for children disclosing sexual abuse is important for addressing the effects of trauma and the potentially lifelong impacts of abuse (Blakemore, Herbert, Arney, & Parkinson, 2017; Cashmore & Shakel, 2013; Lewey et al., 2018). However, there are often considerable barriers to children and their families being able to access these services. This paper presents findings from a systematic literature search on the typical rates of referral, engagement and completion of therapy following a disclosure of child sexual abuse to police or child protection authorities.

Understanding the accessibility of therapy across studies and contexts allows services and policy makers across systems (i.e. criminal justice, child protection, community support and mental health systems) to better understand the accessibility and level of demand for local services when designing intake procedures and developing interventions. No Australian jurisdictions have available and current data on rates of referral, engagement and completion of therapy following the disclosure of child sexual abuse. In part, this is because of the range of government and non-government agencies involved in the delivery of this therapy. The lack of published Australian data to include in the review highlights the need for increased local research attention on the barriers to therapy use following disclosure.

This paper describes a rapid evidence review into research on the utilisation of therapy for child sexual abuse. The results of this rapid evidence review are also reported in the companion paper Factors Influencing Therapy Use Following a Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse.

Appendix A describes the search strategy used in the review and Appendix B outlines the characteristics of the included studies.

Key messages

-

Children who disclose sexual abuse may not be receiving the benefits of therapy due to non-referral, lack of engagement or non-completion of therapy.

-

Providing referrals to therapy for all children with suspected or substantiated sexual abuse would likely increase engagement rates.

-

Focused research is required to better identify the barriers to engagement and completion and identify approaches to improving accessibility to therapy.

-

Additional supports or interventions may be needed to help address barriers to the engagement and completion of therapy for child sexual abuse.

-

Engagement and completion of therapy needs to be systematically tracked to more completely track the outcomes and impacts of sexual abuse therapy services.

Introduction

The point of disclosure to authorities is a critical point to engage children and families affected by child sexual abuse with therapy services. Across all Australian jurisdictions, support services and referrals to therapy tend to be positioned much later in the criminal justice system (for an overview of processes in each Australian jurisdiction see Herbert & Bromfield, 2017), limiting access to the minority whose cases proceed to court or who receive an active response from child protection authorities. This results in considerable sexual harm remaining untreated in the community, or children attending services after symptoms of trauma are already present.

An unknown number of cases of sexual harm in the community go undisclosed (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020) and intervening in these cases is extremely difficult. Where there is disclosure, relatively simple changes to supports at the point of disclosure could have a considerable impact on the extent of untreated sexual harm in the community. While not all children and young people would or should immediately engage with therapy, disclosure remains an important point at which to establish connections between families and supportive services, with a referral to a therapy service part of the discussion.

This review has focused on the accessibility of therapy as a separate issue from the effectiveness of therapy. For the most part, informal systems of referral assume that children have a protective parent who is in a position to be able to advocate for and seek services for them. The lack of a planned system of referral at the point of disclosure means there are limited data on the rate at which children engage with and complete therapy.

In this paper, therapy refers to any program of treatment intended to reduce the effects of trauma following child sexual abuse. Where specified, the most common modalities were structured trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy, other forms of cognitive behavioural therapy (including exposure based), non-structured supportive therapy (an open-ended approach commonly used as a comparison condition for trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy) or other forms of open-ended child-centred therapy, non-directive play and art therapy, and animal-assisted therapy. A summary of the types of therapy from studies in the analysis is included in Appendix B.

This literature review identified rates of referral, engagement and completion of therapy following a disclosure of child sexual abuse to police or child protection authorities. By identifying the typical rates of referral, engagement and completion of therapy, services and policy makers in criminal justice, child protection, community support and mental health systems can better understand the accessibility and level of demand for local services when designing intake procedures and developing interventions. This review enabled analysis of the factors that influence engagement and completion following disclosure that is reported in the companion paper Factors Influencing Therapy Use Following a Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse.

Methodology

This review used a rapid evidence review approach completed by a single reviewer. The search strategy is described in Appendix A. A search string of terms was generated using the NVIVO auto-code feature with full text extracted from 15 studies identified by the author; this was used to identify key terms likely to identify other relevant studies (see Box A.1). The search string was run across Psychinfo, Embase, Medline, Proquest Social Science Premium Collection, and Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global. The results were screened by title and abstract, and then by full record.

Review method

The search identified 49 eligible studies with relevant data reporting on rates in a variety of clinical and community- based therapy service contexts in Australia and the United States. No eligible studies from other countries were identified. Eligible studies reported on rates of therapy referral, engagement or completion following a disclosure of sexual abuse to police or child protection authorities (see Box 1 for a summary of sample types). An overview of the included studies is contained in Appendix B.

The studies reflect diverse service contexts, including tightly controlled clinical studies and community-based services that work with clients with a variety of other issues (e.g. exposure to family and domestic violence, parental mental health, and substance abuse). Most of the studies involved retrospective service data on referral, engagement and completion. The rates were combined using proportional meta-analyses1 (see Appendix A for more detail on the method). These meta-analyses provide a figure referred to as a pooled rate2 across each of the groupings throughout this paper. In a pooled rate, the results are combined as though all participants were in the same study; this is in contrast to an average that treats all studies as the same regardless of the sample sizes in each of the individual studies.

Box 1: Sample types included in the review

Referral samples - rates from studies that reported on the rate at which children received a referral to a therapy service provider:

- Substantiated sexual abuse samples - samples where inclusion in the study required children to have their abuse substantiated by police, state child protection authorities or other equivalent authorities.

- Suspected sexual abuse samples - samples where inclusion did not require a substantiation; so mixed samples of substantiated cases and cases that did not meet the threshold for substantiation after an initial review by authorities.

Engagement samples - rates from studies that reported on engagement with therapy, which meant attending the first session of therapy:

- Observational samples - studies where adults reported retrospectively whether they attended therapy as a child or young person following child sexual abuse.

- Post-investigation - self and professional referral - studies where rates were reported for samples regardless of whether they received a referral.

- Post-investigation - specified professional referral - studies where rates were reported in reference to a specific referral by investigators.

- Therapy initiators - studies where rates were reported for all children and families who made contact with the service to obtain therapy.

- Children in foster care - studies where rates were reported for children in foster care; these were reported separately as this represented a different context from the other samples whose engagement depended on parents/guardians.

Completion samples - rates from studies that reported on completion of therapy, which was defined as finishing a set program, goals or treatment components; the completion of an end of program assessment; a minimum number of sessions completed; therapist discharge or mutual discharge; or continued engagement at the end of data collection:

- Clinical samples - studies that reported rates from samples that involved therapy provided to a carefully controlled group of participants with eligibility (e.g. clinically significant symptoms3) and exclusion criteria (e.g. no current domestic violence or parental mental illness).

- Community samples - studies that reported rates from samples that did not require children to have clinically significant symptoms to enrol in the program or study, and did not exclude participation due to factors that may interfere with the completion of the therapy.

1 The term 'meta-analysis' describes a method of combining results across similar studies, which can then be analysed as a new set of data. A 'proportional meta-analysis' combines the proportions of positive cases (e.g. cases where children completed therapy) across studies.

2 The term 'pooled rate' used throughout the paper is used instead of an average rate to more accurately reflect the number of 'positive' cases in a sample (e.g. number of cases that did complete therapy) in the context of the sample size of the study. The percentages of positive cases are 'pooled' across studies to arrive at the rates reported in this paper.

3 'Clinically significant symptoms' is distinct from the concept of statistical significance and refers to a score on a standardised instrument (e.g. Child Behaviour Checklist) that suggests the presence of some diagnosable issue or disorder.

What are the findings of this review?

Rates of referral to therapy service providers

Key finding

- Children with substantiated sexual abuse have a pooled rate of referral to therapy that is higher (79%) than children with suspected sexual abuse (47%).

Relatively few studies reported on rates of referral to therapy service providers (n = 5). For those that did, these were separated into samples where referrals were made for suspected abuse and referrals were made for substantiated abuse. Suspected abuse samples included children referred for an assessment or investigation to determine whether abuse occurred. Substantiated abuse samples only included children whose abuse had been substantiated by police, state child protection authorities or other equivalent authorities. Table 1 shows the rates across the five studies reporting on rates of referral.

| Study | N | % Received referral | Sample type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected abuse | |||

| Cross et al. (2008) | 1,452 | 53 | Sample of caregivers responding for children referred for a forensic interview with suspected sexual abuse |

| Fong et al. (2018) | 160 | 47 | National sample (US) of children subject to a protection investigation for suspected sexual abuse |

| Lane et al. (2002) | 66 | 36 | Sample of children attending a sexual abuse evaluation centre |

| Substantiated abuse | |||

| Humphreys (1995) | 155 | 78 | Sample of children with substantiated sexual abuse |

| Smith et al. (2006) | 17 | 88 | Sample of children with substantiated sexual abuse |

Among the suspected abuse samples, the pooled rate of referral for therapy was just under half (47%). In a large sample study, Cross and colleagues (2008) found around 53% of children attending a forensic interview received a referral for therapy.

For the substantiated abuse samples, the pooled rate of referral for therapy was much higher (79%). Humphreys (1995) noted that only 78% of children with substantiated abuse received a referral for therapy, despite a policy in New South Wales at the time for all children with substantiated abuse to be referred for therapy.

Engagement with therapy

Key findings

- Only around one-third of children in the pooled sample of children without a referral following an interview or investigation engaged with services (30%).

- Nearly two-thirds of the children in the pooled sample of children that received a referral from a professional following an interview or investigation commenced their therapy (61%).

- Rates of engagement were high (81%) for those in the pooled sample of children that initiated contact with therapy providers.

Table 2 provides an overview of engagement rates across each of the categories of studies included.

| Study | N | % Engaged | Sample type | Substantiated | Definition of Engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational samples | |||||

| Allen et al. (2014) | 117 | 39 | College-age survivors reporting retrospectively | N | Accessed any mental health service |

| Arata (1998) | 62 | 16 | College-age survivors reporting retrospectively | N | Accessed any counselling |

| 59 | 40 | College-age survivors reporting retrospectively | N | Accessed any therapy | |

| Post-investigation - self & professional referral | |||||

| Anderson (2016) | 139 | 25 | Referred for therapy after a forensic interview | Y | Commenced any counselling |

| Cross et al. (2008) | 284 | 35 | Referred for therapy after a forensic interview | N | Commenced any mental health services |

| Post-investigation - specified professional referral | |||||

| Haskett et al. (1991) | 129 | 65 | Referral part of hospital-based crisis intervention centre | Y | Commenced counselling |

| Humphreys (1995) | 121 | 61 | Referred for therapy by child protection authority | Y | Commenced any mental health services |

| Lane et al. (2003) | 24 | 58 | Referral after presenting at a child abuse evaluation clinic | N | Commenced therapy |

| Lippert et al. (2008) | 101 | 54 | Referred for therapy after a forensic interview | N | Commenced therapy |

| McPherson et al. (2012) | 490 | 52 | Referred for therapy at a child sexual abuse assessment centre | N | Commenced therapy |

| Self-Brown et al. (2016) | 41 | 71 | Referral for therapy at a children's advocacy centre | N | Enrolled in therapy |

| Tingus et al. (1995) | 511 | 69 | Referred for therapy by a suspected abuse team | Y | Commenced therapy |

| Therapy initiators | |||||

| Deblinger et al. (2001) | 67 | 81 | Volunteered for therapy after a forensic medical examination | Y | Completed 3 sessions |

| Deblinger et al. (2011) | 210 | 85 | Volunteered for therapy following substantiation of abuse | Y | Completed 3 sessions |

| Horowitz et al. (1997) | 81 | 98 | Volunteered for therapy, referred by child protection authority | N | Commenced therapy |

| Koch (2004) | 91 | 93 | Children presenting at a guidance clinic for therapy service | N | Commenced individual therapy |

| 91 | 74 | Children presenting at a guidance clinic for therapy service | N | Commenced group therapy | |

| Mogge (1999) | 174 | 51 | Children presenting at a school mental health clinic specialising in child sexual abuse for therapy service | N | Completed 3 sessions |

| Oates et al. (1994) | 66 | 66 | Children presenting to sexual assault clinic for therapy service | Y | Commenced therapy |

| Smith et al. (2006) | 15 | 87 | Referral to inhouse therapy service after investigation | Y | Commenced counselling |

| Children in foster care | |||||

| Garland et al. (1996) | 75 | 77 | Children in foster care (subsample of sexually abused children) | Y | Commenced mental health services |

All studies defined engagement similarly in terms of accessing, commencing or attending services (i.e. attending one session of therapy), although three studies defined engagement as attending three sessions of therapy. All sample types included mostly administrative data obtained retrospectively to track engagement in therapy following an initial contact or referral for services. The rates of engagement differed considerably across the sample types.

Two studies reported retrospectively on college-age survivors' engagement with services by studying large cohorts of college students, some of whom reported that they had experienced child sexual abuse - these are observational samples that relied on adults reporting retrospectively. This included reported rates of engagement with counselling, therapy or other kinds of mental health service. Arata (1998) reported that very few participants indicated they had accessed counselling (16%), although they were more likely to indicate they had accessed therapy at some point in their lives (40%). Allen, Tellez, Wevodau, Woods, & Percosky (2014) reported similar rates for accessing any kind of mental health service (39%).

Two studies tracked engagement following a forensic interview or investigation and did not require a referral to therapy for clients to be included in the study - these are referred to as post-investigation - self and professional referral. Both tracked involvement in services following an investigation, either through an interview with caregivers (Cross et al., 2008) or through a retrospective case file review (Anderson, 2016). The rate at which the pooled sample of mixed referral types (self and professional) engaged with services across these studies (30%) was much lower than the other sample types.

Nearly two-thirds of the children in the pooled sample who received a referral from a professional following an interview or investigation commenced therapy (61%). The rates across the post-investigation - specified professional referral studies varied between Self-Brown, Tiwari, Lai, Roby, and Kinnish (2016) at 71%, and McPherson, Scribano, and Stevens (2012) reporting 52%. Many of the studies (Lippert, Favre, Alexander, & Cross, 2008; McPherson et al., 2012) reported on engagement in the context of a children's advocacy centre, where child and family advocates had a role in the forensic process to engage children and their families with therapy services often located on-site.

Rates of engagement across the therapy initiators pooled sample were high (81%) and included some studies with very high rates of engagement (Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, Runyon, & Steer, 2011; Horowitz, Putnam, Noll, & Trickett, 1997; Koch, 2004; Smith, Witte, & Fricker-Elhai, 2006). Many of the studies with very high rates were reporting on children and parents who had contacted services and had undertaken some kind of intake or assessment prior to commencing their first session of therapy.

A single study reported high rates of access to services for sexually abused children in foster care (77%) (Garland, Landsverk, Hough, & Ellis-MacLeod, 1996), asking the caregiver whether the child had been taken to a professional for any kind of mental health service.

Therapy completion rates

Key findings

- For clinical samples with clinically significant symptoms, the pooled rate of completion was 73%.

- For community samples, the pooled rate of completion was 59%.

Studies reporting on rates of completion of therapy following a disclosure of sexual abuse were grouped into clinical samples, which required participants to have clinically significant symptomatology on a psychometric instrument; and community samples, which did not require clinically significant symptomology. The clinical studies had more stringent criteria for entry to the study, which often included a requirement for abuse to be substantiated by a child protection authority or equivalent and the exclusion of families experiencing ongoing domestic violence, substance abuse or parental mental health issues. The clinical samples represent studies with more tightly controlled conditions (i.e. procedures to monitor fidelity to the treatment model), usually as the study was undertaken, to demonstrate the efficacy of the different therapies in optimal conditions. Table 3 contains an overview of completion rates across these samples.

The studies differed in how completion was defined, which also depended on the type of study and the analysis being conducted. Most studies defined completion in terms of finishing a set program, goals or treatment components (n = 12) or the completion of an end of program assessment (n = 10). A minimum number of sessions (n = 8), therapist recommended discharge (n = 5) or mutual discharge (n = 2) were also commonly used. Some studies reported on continued engagement at the end of data collection, rather than completion of therapy (n = 4).

The pooled completion rate among studies that required clinically significant symptoms for inclusion was 73%, and varied between 60% (Cohen & Mannarino, 1996, 2000) and 92% (Cohen, Mannarino, Perel, & Staron, 2007). These studies carefully controlled entry into the samples, requiring clinically significant scores on the post-traumatic stress scale of the Child Behavior Checklist, minimum symptomology on the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory, or meeting minimum thresholds on other trauma and anxiety assessment instruments. Rates were similar across different definitions of completion and across sample sizes (n = <100 or >100).

| Study | N | % Completed | Completion definition | Substantiation required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical sample | ||||

| Allen & Hoskowitz (2017) | 420 | 62 | End of treatment assessment | N |

| Ancha (2003) | 57 | 68 | Attendance rate (80%) | N |

| Celano et al. (2018) | 77 | 69 | Completion of treatment components | N |

| Cohen & Mannarino (1996) | 86 | 80 | Number of sessions (12) | Y |

| Cohen & Mannarino (1997) | 86 | 78 | Complete treatment plan | Y |

| Cohen & Mannarino (2000) | 82 | 60 | Number of sessions (12) and post-treatment assessment | Y |

| Cohen et al. (2004) | 229 | 65 | Complete treatment plan | Y |

| Cohen et al. (2005) | 82 | 60 | Complete treatment plan | Y |

| Cohen et al. (2007) | 24 | 92 | Complete treatment plan | Y |

| Deblinger et al. (1996) | 100 | 90 | Completion of post-treatment measures | Y |

| Deblinger et al. (2011) | 210 | 75 | Completion of post-treatment measures | Y |

| King et al. (2000) | 46 | 83 | Complete treatment plan | Y |

| Community sample (does not require clinical symptoms for enrolment) | ||||

| Barnett (2007) | 945 | 69 | Clinician and parent agreed discharge | N |

| Chasson (2007) | 90 | 60 | Completion of post-treatment measures | N |

| Chasson et al. (2008) | 99 | 70 | Post-treatment assessment and number of sessions (>13) | N |

| Chasson et al. (2013) | 134 | 60 | Number of sessions (15) | N |

| Deblinger et al. (2001) | 63 | 66 | Completion of post-treatment measures | Y |

| DeLorenzi, Daire, & Bloom (2016) | 107 | 37 | Completion of treatment goals | N |

| Friedrich et al. (1992) | 42 | 79 | Clinician and parent agreed discharge | N |

| Hartman (2011) | 22 | 64 | Completion of post-treatment measures | N |

| Horowitz et al. (1997) | 79 | 67 | Number of sessions (26) | N |

| Humphreys (1995) | 74 | 73 | Therapist discharge from treatment or still engaged at point of data collection | Y |

| Koch (2004) | 85 | 71 | Time engaged (>6 months; individual therapy) | N |

| 67 | 69 | Time engaged (>6 months; group therapy) | N | |

| Lippert et al. (2008) | 54 | 74 | Completion not defined | N |

| Macias (2004) | 85 | 53 | Therapist discharge from treatment | N |

| Marx (2004) | 134 | 44 | Therapist discharge from treatment | Y |

| McPherson et al. (2012) | 254 | 39 | Completion of treatment goals | N |

| Mogge (1999) | 172 | 45 | Number of sessions (6 and still engaged at point of data collection | Y |

| Murphy et al. (2014) | 404 | 44 | Therapist discharge from treatment | N |

| New & Berliner (2000) | 608 | 75 | Number of sessions (23) | Y |

| Reyes (1996) | 43 | 65 | Remaining in treatment at point of data collection (rate at 3 months) | N |

| 43 | 49 | Remaining in treatment at point of data collection (rate at 6 months) | N | |

| Self-Brown et al. (2016) | 29 | 31 | Complete treatment plan | N |

| Signal et al. (2017) | 23 | 87 | Complete treatment plan | N |

| Tavkar (2010) | 104 | 56 | Completion of post-treatment measures | Y |

| Tebbett (2013) | 104 | 56 | Completion of post-treatment measures | N |

| Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) | 122 | 44 | Number of sessions (12) and clinician discharge | N |

| Zaidi & Gutierrez-Kovner (1995) | 6 | 67 | Complete treatment plan | N |

The pooled rate of completion across the community sample was 59%, ranging from 31% (Self-Brown et al., 2016) to 87% (Signal, Taylor, Prentice, McDade, & Burke, 2017). Most of the studies were characterised as community samples, reflecting that they did not require children to have clinically significant symptoms to enrol in the program or study, and did not exclude participation due to factors that may interfere with the completion of the therapy (e.g. parental mental health, presence of domestic violence). These programs were also more likely to be open-ended with most studies defining completion in terms of discharge from therapy (n = 7), the number of sessions (n = 6), or a post-treatment assessment that marked the completion of therapy (n = 6). Smaller sample studies (n = <100) tended to have a slightly higher rate of completion.

The rates included were from experimental studies4 (i.e. including completion rates from both experimental and regular practice comparison conditions), and for the most part completion rates weren't able to be separated into different treatment conditions.

4 Experimental studies involve a comparison between an experimental condition (e.g. trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy) and a control condition (e.g. no treatment or a standard form of treatment), which enables researchers to be able to attribute any differences in outcomes (e.g. symptoms of child trauma) to the treatment itself.

Limitations to these findings

Some of the rates reported in this study were limited by the number of studies in each category, particularly in terms of the suspected abuse and substantiated abuse referral rate types and the post-investigation - self and professional referral engagement group. Each of these pooled rates had fairly large confidence intervals. Similarly, a large confidence interval was found for the therapy initiators engagement group, indicating variation in the average rates of engagement across the included studies. A small number of studies in this group had extremely high completion rates that affected the confidence interval.

Meta-analyses looking at the effects of programs against comparison conditions typically report on publication bias, controlling for the increased tendency for studies with larger effect sizes to be accepted for publication (Kicinski, Springate, & Kontopantelis, 2015). This appears to be less of an issue in this review, a proportional meta-analysis where often the rates of engagement/completion were incidental to the study, and where a high or low rate of engagement/completion appears unlikely to influence the likelihood of publication. While the risk of publication bias was low on each of the indicators for most of the samples, the tests indicate a risk of publication bias with the two referral samples (suspected abuse and substantiated abuse), and the post-investigation - self and professional referral samples (see Appendix A for test results). This adds additional uncertainty to these results, although each of the tests used are less effective at detecting publication bias with small numbers of studies (Lin et al., 2018).

Regarding the search strategy, while the review included a comprehensive strategy likely to identify all relevant studies, the search was limited to only peer-reviewed literature, meaning that relevant data from government reports and evaluations may not have been identified. In addition, the search string included the term 'counselling', which may have limited the results by not including other variants on the word (e.g. counsellor, counseling). As is typical in many reviews, the studies were overwhelmingly from the United States. That said, these studies were from a variety of American states that reflect often vastly different socio-economic and socio-legal contexts (e.g. California, Utah, Georgia and Massachusetts).

What are the implications for policy and practice?

Key findings

- Many children are not receiving the benefits of therapy due to non-referral, not engaging when they are referred or non-completion.

- Providing referrals to therapy for all children with suspected or substantiated sexual abuse would likely increase engagement rates but would require increased capacity to deliver therapy to achieve meaningful improvements.

- Additional supports or interventions may be needed to help address barriers to engagement and completion of therapy.

- Engagement and completion of therapy needs to be systematically tracked to quantify the benefits of sexual abuse services and to identify approaches to improve the accessibility of services.

This evidence review extracted data from 49 studies to identify typical rates at which children who have disclosed sexual abuse will receive a referral, and engage with and complete therapy. The samples collected reflect several different situations to get a comprehensive picture of referral, engagement and completion. These rates illustrate the potential stages at which children that have experienced sexual harm may go without the potential benefits of therapy, highlighting very low rates of engagement among studies of the whole cohort of children receiving interviews (Anderson, 2016; Cross et al., 2008). An analysis of factors that may influence engagement and completion are included in the companion paper Factors Influencing Therapy Use Following a Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse.

Around 20% of children in samples that contacted agencies for a service do not commence therapy. Less than half of children with suspected abuse seen by authorities received a referral to therapy, although most with substantiated abuse did. Around one-third of children referred for therapy by authorities do not commence their therapy, and around one-third that commence therapy in a community clinic do not complete their therapy.

Only four Australian studies were identified in the search, and three of these were conducted more than 20 years ago. Humphreys (1995) was about average for referral and engagement rates compared to the studies set in the United States; Oates, O'Toole, Lynch, Stern, and Cooney (1994) was lower than the pooled average for engagement; and completion rates tended to be higher than the pooled average among the Australian studies (Humphreys, 1995; King et al., 2000; Signal et al., 2017).5 There is a clear need for more Australian research on the topic, particularly comparative research that examines the effects of referral practices in different jurisdictions. In addition, future reviews should consider a grey literature strategy to capture government research and commissioned evaluations.

It is well known that there is considerable untreated sexual harm in the community, much of it among children who do not disclose until later in life (e.g. McElvaney, 2015). Relative to the wider population of abused children, children who have disclosed or have abuse that is suspected and investigated by authorities are an easy population to identify as they are known to one or more agencies involved in the response to abuse (i.e. police, child protection, health). Some of these children may not receive referrals for therapy as they do not initially present as being impacted by their abuse or do not demonstrate symptoms that would require an immediate therapeutic response. However, it is well understood that most children will experience impacts from their abuse (Blakemore et al., 2017; Cashmore & Shackel, 2013). Not having arrangements in place to support children and families known or suspected to have been affected by sexual abuse represents a considerable missed opportunity for early intervention and the prevention of re-victimisation.

Considering the extent of sexual harm in the community (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016), the lifelong impacts of abuse (McCarthy et al., 2016) and the rate of attrition from services identified in this research synthesis, a greater focus is needed on improving systems of referral to these services. Many children affected by sexual abuse will be in families with complex needs that have multiple barriers to being able to engage with services for the scale of time needed to address trauma (Fong et al., 2016). Without putting in place systems to help address these barriers, some of the most vulnerable children affected by sexual abuse will go without having their trauma addressed therapeutically.

This also means that investments in addressing the harms of sexual abuse are not having their intended effect. While it is not expected that every child should or would complete therapy, referral practices that assume families are in a position to obtain services has the effect of minimising the demand for services, and results in lingering untreated sexual harm in the community with its associated costs for individuals and communities (McCarthy et al., 2016).

Currently, no Australian jurisdictions report data on the rates of engagement and completion of funded child sexual abuse services from the point of contact with the criminal justice system. Often this is challenging due to the numerous community service providers or multiple health/community systems involved in providing therapy services. Systematically measuring attrition from therapy following sexual abuse is an initial step towards developing evidence-based and data-driven responses to addressing attrition and ensuring children receive treatments that will effectively address their trauma. To advance this, clear and current data on barriers to engagement and completion are needed to inform new approaches.

Monitoring the engagement, completion and benefits of therapy services are critical to demonstrating the benefits of specialised therapy programs and for making a credible case for further investment to increase the accessibility of these targeted services. Monitoring these services would provide critical information about the adequacy of the service system to provide care for the cases identified by authorities. Increasing engagement and completion of services assumes that services are effective in improving outcomes for children and families; undoubtably more work is needed to improve the standards of services and to build in outcome measures that provide clear assurances of the benefits of these services.

It is hoped that these rates will prompt further reflection about the children and young people who either do not engage with or do not complete therapy services following their disclosures. Better understanding of the reasons for not engaging with or withdrawing from services is critical for improving systems of intake, triage and case management within agencies providing therapy to children that have experienced sexual abuse and across service systems connecting investigations to support services.

While many of the barriers to accessing services are difficult to address (e.g. insecure housing, long waitlists), in some cases, barriers (e.g. resistance to accessing mental health services, doubts about the value of therapy) can be addressed or services identified to attempt to manage issues that may lead to disengagement. As an example, the Chicago Children's Advocacy Centre's Providing Access Toward Hope & Healing initiative aimed to improve access to children's mental health services using a system of triage (severity of symptoms and motivation to engage in services) across their network of services, a centralised waitlist, a Hope and Healing drop-in group for children and families on the waitlist, and an enhanced family advocacy service including motivational interviewing and comprehensive family screening (Budde & Waters, 2014).

5 Note: This study had a small sample size (n = 23).

References

- Allen, B., & Hoskowitz, N. A. (2017). Structured trauma-focused CBT and unstructured play/experiential techniques in the treatment of sexually abused children: A field study with practicing clinicians. Child Maltreatment, 22(2), 112-120.

- Allen, B., Tellez, A., Wevodau, A., Woods, C. L., & Percosky, A. (2014). The impact of sexual abuse committed by a child on mental health in adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(12), 2257-2272.

- Ancha, A. J. (2003). Program evaluation of a time-limited, abuse-focused treatment for child and adolescent sexual abuse victims and their families (Psy.D.). Argosy University MI, Ann Arbor, United States.

- Anderson, G. D. (2016). Service outcomes following disclosure of child sexual abuse during forensic interviews: An exploratory study. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10(5), 477-494.

- Arata, C. M. (1998). To tell or not to tell: Current functioning of child sexual abuse survivors who disclosed their victimization. Child Maltreatment, 3(1), 63-71.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Personal Safety, Australia. Canberra; Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/personal-safety-australia/latest-release

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2020). Sexual assault in Australia. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from

- www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/0375553f-0395-46cc-9574-d54c74fa601a/aihw-fdv-5.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- Barnett, C. W. (2007). Predicting treatment completion with maltreated children. The University of Utah, Salt Lake City UT, United States.

- Blakemore, T., Herbert, J. L., Arney, F., & Parkinson, S. (2017). The impacts of institutional child sexual abuse: A rapid review of the evidence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 74, 35-48.

- Budde, S. & Waters, J. (2014). PATHH: Improving access and quality of mental health services to sexually abused children in Chicago. Chicago, IL: Chicago Children's Advocacy Center. Retrieved from www.chicagocac.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/ChicagoCAC-PATHH-White-Paper-102414.pdf

- Cashmore, J. & Shackel, R. (2013). The long-term effects of child sexual abuse. (CFCA Paper No. 11). Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Celano, M., NeMoyer, A., Stagg, A., & Scott, N. (2018). Predictors of treatment completion for families referred to trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy after child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(3), 454-459.

- Chasson, G. S. (2007). Survival analysis of treatment attrition with child victims of trauma: The role of trauma severity. Houston, TX: University of Houston.

- Chasson, G. S., Mychailyszyn, M. P., Vincent, J. P., & Harris, G. E. (2013). Evaluation of trauma characteristics as predictors of attrition from cognitive-behavioral therapy for child victims of violence. Psychological Reports, 113(3), 734-753.

- Chasson, G. S., Vincent, J. P., & Harris, G. E. (2008). The use of symptom severity measured just before termination to predict child treatment dropout. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(97), 891-904.

- Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., & Steer, R. (2004). A multi-site, randomized controlled trial for children with abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 393-402.

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1996). Factors that mediate treatment outcome of sexually abused preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(1), 1402-1410.

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1997). A treatment study for sexually abused preschool children: Outcome during a one-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(9), 1228-1235.

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1998). Factors that mediate treatment outcome of sexually abused preschool children: Six- and 12-month follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(1), 44-51.

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (2000). Predictors of treatment outcome in sexually abused children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(7), 983-994.

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Knudsen, K. (2005). Treating sexually abused children: 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(2), 135-145.

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Perel, J. M., & Staron, V. (2007). A pilot randomized controlled trial of combined trauma-focused CBT and sertraline for childhood PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(7), 811-819.

- Cross, T. P., Jones, L. M., Walsh, W. A., Simone, M., Kolko, D., Sczepanski, J. et al. (2008). Evaluating children's advocacy centres' response to child sexual abuse. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, 106, 1-11.

- Deblinger, E., Lippmann, J., & Steer, R. (1996). Sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms: Initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreatment, 1(4), 310-321.

- Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Runyon, M. K., & Steer, R. A. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 67-75.

- Deblinger, E., Stauffer, L. B., & Steer, R. A. (2001). Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for young children who have been sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreatment, 6(4), 332-343.

- DeLorenzi, L., Daire, A. P., & Bloom, Z. D. (2016). Predicting treatment attrition for child sexual abuse victims: The role of child trauma and co-occurring caregiver intimate partner violence. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 7(1), 40-52.

- Fong, H. F., Alegria, M., Bair-Merritt, M. H., & Beardslee, W. (2018). Factors associated with mental health services referrals for children investigated by child welfare. Child Abuse and Neglect, 79, 401-412.

- Fong, H., Bennett, C. E., Mondestin, V., Scribano, P. V., Mollen, C., & Wood, J. N. (2016). Caregiver perceptions about mental health services after child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 284-294.

- Friedrich, W. N., Luecke, W. J., Beilke, R. L., & Place, V. (1992). Psychotherapy outcome of sexually abused boys: An agency study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 7(3), 396-409.

- Garland, A. F., Landsverk, J. L., Hough, R. L., & Ellis-MacLeod, E. (1996). Type of maltreatment as a predictor of mental health service use for children in foster care. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20(8), 675-688.

- Hartman, S. (2011). From efficacy to effectiveness: A look at trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy in a community setting (Psy.D.). Pace University, Ann Arbor, MI.

- Haskett, M. E., Nowlan, N. P., Hutcheson, J. S., & Whitworth, J. M. (1991). Factors associated with successful entry into therapy in child sexual abuse cases. Child Abuse & Neglect, 15(4), 467-476.

- Herbert, J. L. & Bromfield, L. M. (2018). National comparison of cross-agency practice in investigating and responding to severe child abuse. (CFCA Paper No. 47). Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/national-comparison-cross-agency-practice-investigating-and-responding

- Horowitz, L. A., Putnam, F. W., Noll, J. G., & Trickett, P. K. (1997). Factors affecting utilization of treatment services by sexually abused girls. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(1), 35-48.

- Humphreys, C. (1995). Whatever happened on the way to counselling? Hurdles in the interagency environment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 19(7), 801-809.

- Kicinski, M., Springate, D. A., & Kontopantelis E. (2015) Publication bias in meta-analyses from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Statistics in Medicine, 34, 2781-2793.

- King, N. J., Tonge, B. J., Mullen, P., Myerson, N., Heyne, D., Rollings, S. et al. (2000). Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(11), 1347-1355.

- Koch, E. R. (2004). Factors associated with treatment outcomes among Hispanic survivors of childhood sexual abuse. PhD thesis. Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, CA.

- Lane, W. G., Dubowitz, H., & Harrington, D. (2003). Child sexual abuse evaluations: Adherence to recommendations, Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 11(4), 17-34.

- Lewey, J. H., Smith, C. L, Burcham, B., Saunders, N. L, Elfallal, D., & O'Toole, S. K. (2018). Comparing the effectiveness of EMDR and TF-CBT for children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(4), 457-472.

- Lin, L., Chu, H., Murad, M. H., Hong, C., Qu, Z., Cole, S. R., & Chen, Y. (2018). Empirical comparison of publication bias tests in meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33, 1260-1267.

- Lippert, T., Favre, T., Alexander, C., & Cross, T. P. (2008). Families who begin versus decline therapy for children who are sexually abused. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 859-868.

- Macias, S. B. (2004). The intergenerational transmission of abuse: The relationship between maternal abuse history, parenting stress, child symptomatology, and treatment attrition. PhD thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

- Marx, T. (2004). Attrition from childhood sexual abuse treatment as a function of gender, ethnicity, and parental stress. PhD thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

- McCarthy, M. M., Taylor, P., Norman, R. E., Pezzullo, L., Tucci, J., & Goddard, C. (2016). The lifetime economic and social costs of child maltreatment in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review, 71, 217-226.

- McElvaney, R. (2015). Disclosure of child sexual abuse: Delays, non-disclosure and partial disclosure. What the research tells us and implications for practice. Child Abuse Review, 24(3), 159-169.

- McPherson, P., Scribano, P., & Stevens, J. (2012). Barriers to successful treatment completion in child sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(1), 23-29.

- Mogge, K. L. (1999). Predictors of dropout in child sexual abuse treatment. PhD thesis. University of Memphis, Memphis, TN.

- Murphy, R. A., Sink, H. E., Ake, G. S., Carmondy, K. A., Amaya-Jackson, L. M., & Briggs, E. C. (2014). Predictors of treatment completion in a sample of youth who have experienced physical or sexual trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(1), 3-19.

- New, M., & Berliner, L. (2000). Mental health service utilization by victims of crime. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(4), 693-707.

- Oates, R. K., O'Toole, B. I., Lynch, D. L., Stern, A., & Cooney, G. (1994). Stability and change in outcomes for sexually abused children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(7), 945-953.

- Reyes, C. J. (1996). Resiliency of young children: Self-concept, parental support, and traumatic symptoms after sexual abuse. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

- Self-Brown, S., Tiwari, A., Lai, B., Roby, S., & Kinnish, K. (2016). Impact of caregiver factors on youth service utilization of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy in a community setting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1871-1879.

- Signal, T., Taylor, N., Prentice, K., McDade, M., & Burke, K. J. (2017). Going to the dogs: A quasi-experimental assessment of animal assisted therapy for children who have experienced abuse. Applied Developmental Science, 21(2), 81-93.

- Smith, D. W., Witte, T. H., & Fricker-Elhai, A. E. (2006). Service outcomes in physical and sexual abuse cases: A comparison of child advocacy center-based and standard services. Child Maltreatment, 11(4), 354-360.

- Tavkar, P. (2010). Psychological and support characteristics of parents of child sexual abuse victims: Relationship with child functioning and treatment. PhD thesis. The University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE.

- Tebbett, A. A. (2013). Predictors of attrition in trauma-specific cognitive-behavioral therapy. PhD thesis. St. John's University, New York, NY.

- Tingus, K. D., Heger, A. H., Foy, D. W., & Leskin, G. A. (1996). Factors associated with entry into therapy in children evaluated for sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(1), 63-68.

- Wamser-Nanney, R., & Steinzor, C. E. (2017). Factors related to attrition from trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect, 66, 73-83.

- Zaidi, L. Y., & Gutierrez-Kovner, V. M. (1995). Group treatment of sexually abused latency-age girls. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10(2), 215-227.

Appendix A: Therapy use

Search strategy

A search string was generated using the NVIVO auto-code feature with full text extracted from 15 target studies; this was used to identify key terms likely to identify other relevant studies (see Box A.1). The search string6 was run across Psychinfo, Embase, Medline, Proquest Social Science Premium Collection, and Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global. The results were screened in Covidence by title and abstract, and then by full record.

Box A.1 Search string

((treat* or mental health or mental-health or therap* or service* or counselling) and (child* or youth or young pe* or girls or boys) and (sexual abus* or molest* or sexual assault or exploit or sexual harm or sexual maltreat*) and (utilis* or utiliz* or complet* or engag* or attend* or obstacle* or attrition or access* or hinder* or motivation* or enrol* or drop* or exit* or cessat* or quit* or leave* or end*) and (factors or barriers or enabl* or characteris* or cause* or component* or influenc* or aspect* or impediment* or obstacle* or facilitate* or predict* or pattern* or determin*)).ab.

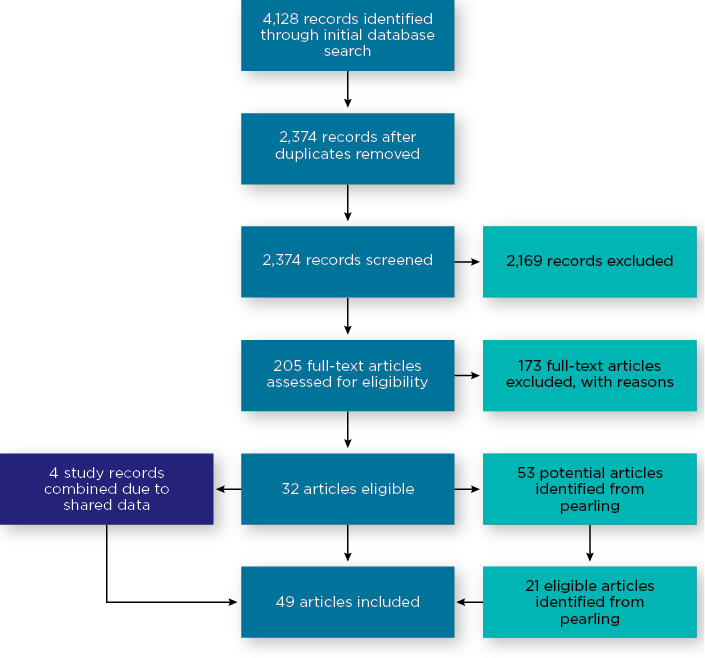

The search identified 2,374 individual studies for title and abstract screening, which was reduced to 205 studies by a single reviewer for full-text screening (see Figure A.1). These were studies that very clearly did not meet eligibility based on title and abstract. These 205 studies were assessed for eligibility, which identified 32 eligible studies. A total of 173 studies were excluded for the following reasons:

- The study was about the impacts of abuse rather than referral/engagement/completion of therapy (n = 42).

- The study involved an adult population (n = 32).

- The study design did not allow for data about referral/engagement/completion (n = 18).

- Sexual abuse was not analysed separately from other forms of maltreatment (n = 15).

- Study was about the characteristics or impacts of abuse rather than about the treatment of abuse (n = 12).

- The paper did not involve empirical research and was a conceptual or theoretical paper (n = 8).

- Full text could not be obtained, even when requested from the University of South Australia library services (n = 7).

- Other/miscellaneous (n = 11).

Pearling7 was undertaken across the 32 eligible studies. This involved reading through each of the articles and identifying any references to studies that may contain relevant information for the review. This process identified an additional 21 eligible studies. Some of the eligible studies (n = 4) were found to be an analysis of the same dataset. In these cases, information about the studies was combined into a single record in the extraction template. A total of 49 studies were found to be eligible and were extracted.

Figure A.1: PRIMSA flow diagram of systematic literature search

The extraction template included:

- study information: study ID number, authors, year, if the study shared data with any other included studies, title, country of study, publication type, study design

- sample information: sample type narrative description, whether caregiver consent to participate in the study was required, whether clinical symptoms were required to be included, whether the sample initiated therapy, if the sample was from a children's advocacy centre, if cases were required to be substantiated to be included, if a mixed abuse sample then what proportion included sexual abuse, if mixed age groups then what proportion was under 18, gender, ethnicity

- therapy characteristics: therapy narrative description, if caregivers were part of the therapy, definition of referral, definition of engagement, definition of completion

- data: total sample, referral data, engagement data, completion data

- independent variable narrative: significant differences, non-significant differences.

Five studies had relevant data on rates of referral, 19 studies had relevant data on rates of engagement, and 37 studies had relevant data on rates of completion of services. The reported rates for groups of studies are based on pooled proportions using a random effects proportional meta-analysis conducted in MedCalc (see below for meta-analysis methodology).

This research was undertaken to identify typical rates of referral, engagement and completion across different types of therapy services for children disclosing sexual abuse. The intent of this was to illustrate the typical proportions of children that are not benefiting from or not receiving the full benefit of therapeutic services to address harm from sexual abuse. We note that many survivors access therapy later in life; however, intervening early is critical to reducing the effects of trauma and the impacts of abuse across life domains.

Meta-analysis

Multiple proportional meta-analyses were conducted on the included studies to produce the pooled rates reported. Each of the rates was grouped based on characteristics that seemed likely to affect the referral/engagement/completion rates.

For referral rates, studies were grouped on whether they required cases to have been substantiated by authorities (i.e. police, child protection or some other authority), or whether abuse was suspected and still subject to investigation.

For engagement rates, studies were grouped into post-investigation - self and professional referral, post-investigation - specified professional referral, and therapy initiators. Two other groupings of studies were found that have been reported on (observational studies and children in care) but were not included as meta-analyses due to small numbers and these studies not being as relevant to the central questions of service access following disclosure. Post-investigation - self and professional referral refers to studies that examined engagement with therapy following an investigation regardless of whether a referral was made for a child. Post-investigation - specified professional referral refers to studies examining engagement related to a specific referral made by police, child protection or some other professional following an investigation. Therapy initiators refers to studies examining the rate of engagement for clients that have contacted specialist sexual abuse services; for these studies it generally is not known who made the referral.

For completion rates studies were grouped into either clinical samples, which required clinically significant symptomology to be included, or community samples, where services responded to clients regardless of if they met the threshold for clinically significant symptomatology. Clinical samples also tended to deliver a structured program of therapy as part of efforts to test the effectiveness of treatment, which also included screening out clients that may have ongoing issues in the home such as parental mental health, family and domestic violence, or parental substance abuse.

The proportional meta-analysis feature in MedCalc was used, reporting on the results of the random effects model, reflecting that the studies were heterogeneous in that rates were likely to be affected by the characteristics of the studies and samples. Publication bias testing was performed in Statsdirect 3.

The results of each of the meta-analyses are reported in Table A.1. The funnel plots for each of the tests are available from the author on request.

| Pooled sample | Test for heterogeneity | Random effects [95% confidence interval] | Publication bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral rates | ||||

| Suspected abuse | 1,678 | Q = 8.74, df = 2, p = 0.013* | 47% [39-56] | Egger's test, p = <0.05 I 2 = 77.1% |

| Substantiated abuse | 172 | Q = 0.75, df = 1, p = 0.385 | 79% [72-85] | Egger's test, p = <0.05 I 2 = 0% |

| Engagement rates | ||||

| Post investigation - self and professional referral | 423 | Q = 4.08, df = 1, p = 0.043* | 30% [22-40] | Egger's test, p = <0.05 I 2 = 75.5% |

| Post investigation - specified professional referral | 1,417 | Q = 35.77, df = 6, p = <0.0001* | 61% [54-68] | Egger's test, p = 0.952 I 2 = 83.2% |

| Therapy initiators | 795 | Q = 119.79, df = 7, p = <0.0001* | 81% [68-91] | Egger's test, p = 0.154 I 2 = 94.2% |

| Completion rates | ||||

| Clinical samples | 1,499 | Q = 73.025, df = 11, p = <0.0001* | 73% [67-79] | Egger's test, p = 0.662 I 2 = 80.6% |

| Community samples | 3,992 | Q = 301.83, df = 26, p = <0.0001* | 59% [54-65] | Egger's test, p = 0.662 I 2 = 91.3% |

Note: * p = <.05

6 The search string is a standard format of search terms - using a search string is important so that potentially someone can run the same search and arrive at the same result.

7 Pearling involves searching the reference list of included studies to identify any additional relevant studies that may not have been identified in the initial search.

Appendix B: Therapy use

| Author(s) | Country | Sample8 | Therapy type/s | Study design | Data included in reviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen & Hoskowitz (2017) | United States | 420 | TF-CBTa vs play/experiential therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion |

| Allen et al. (2014) | United States | 117 | Unspecified ('mental health services, therapy or treatment') | Retrospective study of college students that had experienced sexual abuse | Rate of engagement Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) |

| Ancha (2003) | United States | 57 | Abuse-focused cognitive behavioural therapy | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion |

| Anderson (2014; 2016)9 | United States | 139 | Unspecified ('counselling') | Study of service use following a forensic interview | Rate of engagement Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| Arata (1998) | United States | 204 | Unspecified ('counselling' and 'therapy') | Study of current wellbeing of CSA survivors | Rate of engagement |

| Barnett (2007) | United States | 945 | Unspecified ('mental health treatment') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Celano et al. (2018) | United States | 77 | TF-CBT | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Chasson (2007) | United States | 90 | Combination of cognitive behavioral and supportive therapy | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) |

| Chasson et al. (2008; 2013) | United States | 134 | Exposure-based CBTb | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) |

| Chasson, Vincent, & Harris (2008) | United States | 99 | Combination of cognitive behavioral and supportive therapy | Study of whether symptom severity can predict attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen & Mannarino (1996)10 | United States | 86 | CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Study of factors influencing treatment outcomes | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen & Mannarino (1997) | United States | 86 | CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion |

| Cohen & Mannarino (2000) | United States | 82 | CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen et al. (2004) | United States | 229 | TF-CBT vs child-centred therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen et al. (2007) | United States | 24 | TF-CBT with sertraline vs TF-CBT with placebo | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion |

| Cohen, Mannarino, & Knudsen (2005) | United States | 82 | TF-CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Cross et al. (2008) | United States | 1452 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of referral Rate of engagement |

| Deblinger et al. (2011) | United States | 210 | TF-CBT without trauma narrative vs TF-CBT with trauma narrative | Outcomes comparison | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Deblinger, Lippmann, & Steer (1996) | United States | 100 | CBT vs standard community care | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Deblinger, Stauffer, & Steer (2001) | United States | 67 | CBT vs supportive counselling | Outcomes comparison | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Child characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| DeLorenzi, Daire, & Bloom (2016) | United States | 107 | Unspecified ('counselling') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Fong et al. (2018) | United States | 160 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Sub-set of national (US) dataset on referral to therapy | Rate of referral |

| Friedrich et al. (1992) | United States | 42 | Open-ended therapy with directive and non-directive components | Outcomes study | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) |

| Garland et al. (1996) | United States | 75 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement |

| Hartman (2011) | United States | 24 | TF-CBT | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion |

| Haskett et al. (1991) | United States | 129 | Unspecified ('crisis counselling') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) |

| Horowitz et al. (1997) | United States | 81 | Unspecified ('treatment services') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Humphreys (1995) | Australia | 155 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of referral Rate of engagement Rate of completion |

| King et al. (2000) | Australia | 46 | CBT vs waitlist | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Koch (2004) | United States | 91 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of factors associated with treatment outcomes | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Lane, Dubowitz, & Harrington (2002) | United States | 66 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of referral Rate of engagement |

| Lippert et al. (2008) | United States | 101 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) |

| Macias (2004) | United States | 85 | Unstructured treatment | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Marx (2004) | United States | 134 | Unstructured treatment | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| McPherson, Scribano, & Stevens (2012) | United States | 490 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Mogge (1999) | United States | 174 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Murphy et al. (2014) | United States | 404 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion |

| New & Berliner (2000) | United States | 608 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Oates et al. (1994) | Australia | 66 | Therapists reported on the type of therapy approaches used | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of engagement Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| Reyes (1996) | United States | 43 | Non-directed play therapy | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) |

| Self-Brown et al. (2016) | United States | 41 | TF-CBT | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| Signal et al. (2017) | Australia | 23 | Animal-assisted therapy | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion |

| Smith, Witte, & Fricker-Elhai (2006) | United States | 17 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement |

| Tavkar (2010) | United States | 104 | CBT | Study of factors associated with treatment outcomes | Rate of referral Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Tebbett (2013) | United States | 104 | TF-CBT | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Tingus et al. (1995) | United States | 511 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) |

| Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) | United States | 122 | TF-CBT | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Zaidi & Gutierrez-Kovner (1995) | United States | 6 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Description of treatment | Rate of completion |

Notes: a Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy; b Cognitive behavioural therapy

8 Note: In some instances, the total sample of the study does not match the figures used in the meta-analysis. This is because some studies used subsets to report on engagement and completion.

9 The search identified an additional paper that drew from the same data in Anderson (2016). The additional article identified in the search that drew on the same data is: Anderson, G. D. (2014). How do contextual factors and family support influence disclosure of child sexual abuse during forensic interviews and service outcomes in child protection cases? PhD thesis. University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN.

10 The search identified multiple papers that drew from the same data as in Cohen and Mannarino (1996). The additional articles identified in the search that drew on the same data are: Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1996). A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: Initial findings. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(1), 42-50.

Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1998). Factors that mediate treatment outcome of sexually abused preschool children: Six- and 12-month follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(1), 44-51.

Dr James Herbert is a Senior Research Fellow at the Australian Centre for Child Protection, University of South Australia. Dr Herbert specialises in research and evaluation on multi-agency responses to abuse and neglect, and cross-systems challenges in responses to social problems. His most recent work focuses on the quality of deliberation in multi-agency case review meetings, along with a focus on effective referral and support systems following the disclosure of abuse.

The author would like to thank Fernando Lima for his feedback on the meta-analysis approach, Professor Leah Bromfield for her review of an early draft of the paper, and Amanda Coleiro and Nerida Joss for their assistance with preparing the paper.

Featured image: © GettyImages/Zurijeta

978-1-76016-223-8