Therapeutic residential care: An update on current issues in Australia

September 2018

Sara McLean

Download Policy and practice paper

Overview

Therapeutic residential care is a relatively recent development in out-of-home care service provision for young people who are unable to be placed in family-based care. This paper provides an update on developments in therapeutic residential care, discusses the implications of these developments, and touches on further issues and dilemmas that should form the focus of research and practitioner partnerships in the future.

Key messages

-

Therapeutic residential care is a relatively recent development in service delivery for young people with complex care needs in out-of-home care.

-

There is emerging consensus about the effective elements of therapeutic residential care including: shared understanding of young people's needs; placement based on shared needs; therapeutic input tailored to needs; best possible connection to family and culture; and prioritising relationship-based work.

-

The Australian definition of therapeutic residential care reflects the unique aspects of therapeutic care service provision in this country.

-

Many Australian jurisdictions are adopting therapeutic residential care and this is now reflected in policy and practice documents in many jurisdictions.

-

Some Australian jurisdictions have begun to mandate minimum qualifications for residential care workers.

Introduction

Therapeutic residential care is a relatively recent development in out-of-home care service provision for young people who are unable to be placed in family-based care for a range of reasons.

Since the inaugural Australian Therapeutic Residential Care Forum in 2010 - held shortly after therapeutic residential care was first piloted in Australia - this form of service provision has seen sustained growth in this country.

This paper provides an update on developments in therapeutic residential care that have occurred since the forum and the publication of its companion paper Therapeutic residential care in Australia: Taking stock and looking forward (McLean, Price-Robertson, & Robinson, 2011). These developments include: the creation of an industry peak body; an Australian definition for therapeutic residential care; a better understanding of young people's needs; an understanding of the effective elements of therapeutic residential care; and guiding policies and workforce initiatives in Australian jurisdictions. This paper also discusses the implications of these developments, and touches on further issues and dilemmas that should form the focus of research and practitioner partnerships in the future.

A companion paper to this paper will present the results of a 2018 survey of existing Australian therapeutic residential care services (McLean, forthcoming), in order to better describe contemporary Australian practice. The results of this survey are expected to provide a useful description of how Australian services currently operate; and provide baseline information to inform future policy, research and service delivery.

Therapeutic residential care in Australia

Therapeutic residential care is an out-of-home care (OOHC) service provision model for children and young people with complex needs. The model looks to respond to the complex effects of abuse, neglect and separation from family by actively facilitating healing and recovery. It offers care based on several guiding principles for: understanding and responding to young people's needs; adopting clear models of practice; and the recruiting and staffing of therapeutic residential care homes. These principles are detailed later in this paper.

There is currently no detailed information about what proportion of Australian residential-care homes deliver services according to the guiding principles of therapeutic residential care. At present, the closest information is the data on the use of residential care for children in OOHC collated by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) each year in its annual report Child protection Australia (AIHW, 2018).

As of 30 June 2017, approximately one in 20 young people in OOHC were living in residential care in Australia (AIHW, 2018). This is generally consistent with other English-speaking countries, in which residential care is used for a relatively small proportion of young people in OOHC, when compared with mainland European countries (e.g. 54% in Germany; Hart, La Valle, & Holmes, 2015). In Australia, the vast majority of these children were aged 10 years or over (85%); with a median age of 14. Only 3% of children in residential care were aged five years or younger (AIHW, 2018). Anecdotally, residential care may be used to enable sibling groups to remain together when no other alternative is available (AIHW, 2018; McLean, 2015). Aboriginal young people remain over represented in residential care (AIHW, 2018).

Residential services vary widely across the world with respect to unit size and location, length of stay, level of restrictiveness, staffing configuration and treatment goals, populations, models and program rationale (Delfabbro, Osborn, & Barber, 2005; James, 2011; McLean, 2016). Internationally, residential programs are provided to young people with a range of diverse needs (e.g. mental health, youth justice and child welfare needs). In Australia, both 'standard' and 'therapeutic' residential care (Victorian Auditor-General's Office [VAGO], 2014) is used almost exclusively to service referrals for young people in the statutory child welfare system.

While the proportion of young people in residential care has remained relatively stable over the past decade; there has been a growth in the number of Australian services claiming to provide therapeutic residential care (National Therapeutic Residential Care Alliance, personal communication, 12 September 2017). These services will be described in a companion paper to this paper, which will present the results of a 2018 survey of existing Australian therapeutic residential care services (McLean, forthcoming).

Recent developments in therapeutic residential care

Since the publication of Therapeutic residential care in Australia (McLean et al., 2011), there has been a number of key developments in the area of therapeutic residential care. These include:

- an industry peak body for therapeutic residential care services

- an agreed definition of therapeutic residential care in Australia

- a better understanding of young people's needs

- an understanding of the effective elements of therapeutic residential care

- the development of guiding policies

- the development of workforce initiatives.

Each of these key developments will be described in turn, and the implications for service development will be discussed. Areas in need of further development will also be highlighted.

1. An industry peak body for therapeutic residential care services

The formation of the National Therapeutic Residential Care Alliance (NTRCA) in 2012 was one of the key developments arising from the second national Therapeutic Residential Care Forum in Brisbane in 2012. This peak body began as a community of practice; sharing their collective knowledge about best practice in the area of therapeutic residential care. Since its inception, the NTRCA has met regularly to support research and development in the sector; as well as advocate for the need for therapeutic service provision as a viable option for many young people in OOHC. The objectives of the NTRCA are to:

- promote the judicial use of therapeutic residential care

- generate consensus regarding the nature and scope of therapeutic care service provision

- support agencies that provide therapeutic care

- take a considered approach to building the evidence base in this field by partnering with leading researchers in this area.

Box 1: National Therapeutic Residential Care Alliance (NTRCA)

Since the NTRCA was formed, it has continued to grow. It has a membership reflective of all Australian jurisdictions and is comprised of service leaders in therapeutic residential care service provision. The next phase of development for the NTRCA is the dissemination of research-to-practice related materials, the advancement of a set of national standards and the construction of a website to support therapeutic residential care service delivery in the Australian context. The NTRCA and its membership is available to provide comment and advice to government agencies and other community service organisations on the delivery of therapeutic residential care.

For more information on the NTRCA and to view a list of foundational reference group members, visit the NTRCA website or email [email protected]

2. An agreed definition of therapeutic residential care in Australia

An initial interim definition of Australian therapeutic residential care was produced in 2011:

Therapeutic Residential Care is intensive and time-limited care for a child or young person in statutory care that responds to the complex impacts of abuse, neglect and separation from family. This is achieved through the creation of positive, safe, healing relationships and experiences informed by a sound understanding of trauma, damaged attachment and developmental needs. (National Therapeutic Residential Care Working Group; in McLean et al., 2011, p. 2)

Notably, this original definition specified that therapeutic residential care should be time limited; and be offered to a child or young person in statutory care.

Since then, a consortium of international researchers has proposed an alternative consensus definition for therapeutic residential care (Whittaker, del Valle, & Holmes, 2014). This definition responds to growing recognition of the potential for therapeutic residential care to enhance young people's lives by addressing multiple life domains. It places emphasis on different elements of care; in particular, it emphasises the intentional and goal-directed nature of therapeutic residential care; and places an emphasis on partnership with family and community:

Therapeutic Residential Care involves the planful use of a purposefully constructed, multi-dimensional living environment designed to enhance or provide treatment, education, socialisation, support and protection to children and youth with identified mental health or behavioural needs in partnership with their families and in collaboration with a full spectrum of community-based formal and informal helping resources. (Whittaker et al., 2014, p. 24)

In developing this definition, the authors acknowledged that therapeutic care could be expressed in a variety of ways in a residential environment; according to the different cultural and service contexts in which the service is delivered (Whittaker et al., 2014). Therefore, an advantage of this definition is that it is flexible enough to accommodate regional variations in the focus of the intervention and populations served (Bath, 2017).

Both the Australian and the international definitions may be limited by their failure to recognise needs such as disability, pervasive developmental disorders and conditions such as foetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD); all of which appear commonly in OOHC (AIHW, 2018; Bath, 2017; McLean, 2016).

Notwithstanding this, it is worth highlighting key differences between the 2011 Australian definition of therapeutic residential care and the 2014 international definition, as detailed in Table 1.

| 2011 Australian interim definition | International consensus definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Who is supported | Young people in statutory care (OOHC) | Children and youth with identified mental health and behavioural needs |

| The nature of care | Intensive and time-limited care | Purposeful and planful admissions |

| The scope of intervention | Complex trauma history (focus of support is on helping young people with a history of multiple interpersonal traumas in the context of the caregiving relationship) | Mental health and behaviour (focus on support is on young people with serious and significant challenges to their mental wellbeing; and who may express their distress as behavioural disturbance) |

| The scope of need | Attachment, healing relationship and development (young people who need support in understanding and healing from unhelpful attachment and relationship difficulties) | Multi-dimensional systemic approach involving family and community partnerships (young people who need support to form positive and supportive connections to prosocial family and community supports) |

Taken all together, these distinctions highlight the conceptual, ideological and practical distinctions between therapeutic residential care as it is used in Australia, and how it is used elsewhere in the world (for a comprehensive description of international models see Courtney & Iwaniec, 2009 and Whittaker et al., 2016).

Arguably, neither definition adequately reflects the way that therapeutic residential care is currently being used in Australia (Ainsworth, 2017; Ainsworth & Hansen, 2015; Bath, 2017). More specifically, Ainsworth (2017) notes that in Australia:

- Therapeutic residential care is still most commonly used for young people in statutory care who have had multiple 'failed' foster placements (compared to young people being referred with mental health or forensic concerns, or being placed straight into residential group homes based on assessed need).

- Therapeutic residential care is likely to be staffed by youth workers (compared to specialist mental health professionals such as psychologists or psychiatrists); although there may be input from therapeutic specialists, who may have training in psychology.

- Therapeutic residential care is unlikely to involve formal therapeutic or mental health group work; although emphasis is placed on the creation of a therapeutic milieu.

- Therapeutic residential care is unlikely to be a time-limited 'treatment', with many young people in all forms of residential care remaining there until they reach 18; with some remaining as long as three years (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2018; Family and Community Services, 2017a, 2017b).

In light of these fundamental differences between how therapeutic residential care is conceptualised in the international literature, and how it appears to be used in Australia, the NTRCA has proposed a revised definition. Arguably, this definition better describes the 'philosophy' of care embodied in therapeutic residential care in Australia, as compared with how residential care is offered elsewhere in the world.

Therapeutic residential care is an intensive intervention for children and young people, which, in Australia, is a part of the out-of-home care system. It is a purposefully constructed living environment which creates a therapeutic milieu that is the basis of positive, safe, healing relationships and experiences designed to address complex needs arising from the impacts of abuse, neglect, adversity and separation from family, community and culture. Therapeutic care is informed by current understandings of trauma, attachment, socialisation and child development theories; which are translated into practice and embedded in the therapeutic care program. (National Therapeutic Residential Care Alliance, 2016)

This definition acknowledges the unique role that therapeutic residential care plays in the Australian OOHC service landscape. It addresses perceived limitations of the previous Australian definition by removing the 'time-limited' component of the definition; while being consistent with Australian ideology and staffing configurations that do not tend to conceptualise young people's needs through a forensic or mental health lens. The definition reflects the fact that facilities are typically staffed by youth workers who prioritise a supportive relationship with young people as a means to promote young people's psychosocial development. The definition also counters a view of therapeutic residential care as a 'placement of last resort' following the failure of less intensive interventions. Instead, it is viewed as one of a range of potential services provided by an organisation under an overarching therapeutic practice framework. Finally, the definition mirrors the essential elements of therapeutic care now articulated in policy and practice documentation across several Australian jurisdictions.

Arguably, the adoption of a local Australian consensus definition will be an important step in advancing the status of therapeutic residential care in this country. It is noteworthy, however, that some key Australian authors favour the international consensus definition over the local definition. In particular, an advantage of the international definition is its scope to accommodate a broader range of developmental issues beyond relational trauma (see Ainsworth, 2017; Bath, 2017).

3. A better understanding of young people's needs

It is well accepted that young people in residential care are likely to have been exposed to significant trauma and neglect in the context of their early caregiving relationships and in their subsequent relationships with other adults (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2015). Concepts such as 'trauma-informed' care and organisational 'congruence' permeate Australian policy and practice documentation related to effective therapeutic residential care (Bath, 2017; McLean et al., 2011). The field of therapeutic residential care in Australia and elsewhere continues to be influenced by key authors such as James Anglin, Sandra Bloom and Bruce Perry (Anglin, 2002; Bloom, 2005; Perry, 2006).

More recently, our understanding of the needs of young people has also been shaped by the increasing recognition of the need to:

- engage with a young person's family of origin and wider community network (Ainsworth, 2017; Holden, Anglin, Nunno, & Izzo, 2014; Holden et al., 2010)

- understand and respond to a young person's developmental functioning - emotionally, cognitively and socially (Bath, 2017; Holden et al., 2010; Holden et al., 2014)

- tailor residential programs to meet young people's mental health and behavioural needs (Ainsworth, 2017; Whittaker et al., 2014)

- prioritise quality relationships between workers and young people as a means for offering an alternative narrative of self in a relationship, and of adult-child dynamics (Holden et al., 2010).

Each of these areas of need is described in more detail below and the implications for therapeutic service provision is discussed.

a. Engaging with a young person's family of origin and wider community network

Publications over more than a decade have highlighted the importance of involving a young person's family members in maintaining good outcomes over time (Ainsworth, 2017; Bath, 2008a, 2008b, 2015; Knorth, Harder, Zanberg, & Kendrick, 2008; McLean et al., 2011; McNamara, 2014). When significant family members are not engaged in planning and supporting the young person's goals, outcomes may not be maintained post-care (Knorth et al., 2008).

This presents particular challenges for residential-care staff working with young people in a statutory context. Clear guidelines are needed to determine how to support 'best possible' connection with family and community (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2018; McLean, 2016; McLean et al., 2011). It may be that practice in this area can be improved by supporting youth workers to take part in activities that sit outside their traditional mandate (e.g. in facilitating family work; assessing risk and safety in family connections; and in sourcing and building community connections for youth in care). Therapeutic residential care services are likely to benefit from clearly articulated guidelines on how to promote best possible family and cultural connections. There may be scope for a young person's key residential care worker to take a more active 'casework-like' role in supporting a young person's relationship with family and cultural networks.

b. Understanding and responding to a young person's developmental functioning

There is increasing recognition of the importance of understanding and responding to young people's current developmental level; and to their cognitive, sensory and language functioning in particular (McLean, 2016). The CARE model (Holden et al., 2010; Holden et al., 2014; see Box 2 for more on this and other models) explicitly articulates the need to meet a young person at their current developmental level, and to support and extend the young person's development based on a sound understanding of their current functioning. In light of this, all residential care workers may benefit from training in the normative course of child development across all ages, including the developmental stages of language, cognitive and moral development (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2018). Recent studies in residential homes have demonstrated the benefit of addressing delayed language development among youth in residential care (Manso, Sanchez, Alonso, & Romero, 2012; Moreno-Manso, García-Baamonde, Blázquez-Alonso, & Pozueco-Romero, 2015; Moreno-Manso, García-Baamonde, Blázquez-Alonso, Pozueco-Romero, & Godoy-Merino, 2016). Residential care workers may benefit from training in strategies to simplify and scaffold young people's developing language and cognitive skills. Some resources already exist to help caregivers to scaffold language development (see Language and Communication Difficulties).

c. Tailoring residential programs to meet young people's mental health and behavioural needs

There is an increasing understanding of the need to tailor a residential care service to better address young people's mental health and behavioural needs (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2018; Bath, 2017; McLean, 2016). While 'trauma-informed' care is necessary, it may not be sufficient to meet the complex support needs of some young people (Bath, 2017; McLean, 2016, 2018). There is a need for services to be tailored to young people's shared mental health and behavioural support needs. This may mean providing a highly structured living environment; it may involve cognitive behavioural programs to address emotional regulation, problem solving or impulse control; or in some cases it may involve modifying language and instructions to accommodate young people's memory or language issues (Ainsworth, 2017; Manso et al., 2012; McCurdy & McIntyre, 2004; McLean, 2016; Thompson & Daly, 2014).

Young people's developmental and behavioural issues (e.g. intellectual disability, sexual offending, conduct disorder) may be addressed more effectively by adopting some of the evidence-based interventions that feature in residential treatment models (such as structured behavioural analysis, skills training and empathy training programs) (Ainsworth, 2017; Knorth et al., 2008; McLean, 2016). Developments such as these would have significant workforce and funding implications.

ADHD Estimates range from 3-68% Ford, Vostanis, Meltzer, & Goodman, 2007; McCann, Wilson, & Dunn, 1996; Willis, Dhakras, & Cortese, 2017 |

Alcohol and substance use Estimates range from 21-40% Braciszewski & Stout, 2012; Department of Communities, 2011; Pottick, Warner, & Yoder, 2005 |

Anxiety disorder Estimates range from 11-26% Bazalgette, Rahilly, & Trevelyn, 2015; Ford et al., 2007; McCann et al., 1996; Meltzer, Lader, Corbin, Goodman, & Ford, 2004 |

Autism spectrum disorder/pervasive developmental disorder Estimates range from 2-36% Department of Communities, 2011 |

Depression Estimates range from 3-23% Bazalgette et al., 2015; Ford et al., 2007; McCann et al., 1996; Meltzer et al., 2004; Sawyer, Carbone, Searle, & Robinson, 2007; Winsor & McLean, 2016 |

Fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders Estimates range from 6-16.7% Lange, Shield, Rehm, & Popova, 2013 |

Intellectual disability Estimates range from 3-25% Baker, 2007; Hill, Baker, Kelly, & Dowling, 2015; Kelly, Dowling, & Winter, 2012; Mitchell, 2013; Sawyer et al., 2007 |

Language disorder or delay Estimated at 12% Hill et al., 2015; |

Learning difficulties and educational delays Estimated at least 10% Trout, Hagaman, Casey, Reid, & Epstein, 2008; Trout, Hagaman, Chmelka et al., 2008 |

Problem sexual behaviour Estimated range up to 48% Department of Communities, 2011 |

Suicide - attempted or threatened Estimates range from 6-30% Pottick et al., 2005; |

Youth offending Estimates range from 10-44% AIHW, 2017; |

There is growing international recognition of the considerable mental health needs of many young people placed in residential care homes; including a high level of youth meeting criteria for dual clinical mental health diagnosis (Nelson et al., 2012; Pottick et al., 2005). Internationally, there is a growing trend towards services implementing evidence-informed strategies (James et al., 2015). There is clear potential for Australian services to benefit from incorporating evidence-informed treatment programs tailored to young people's shared behavioural and mental health needs.

In practice, this could be facilitated by:

- funding that enabled the employment of mental and allied health clinicians, familiar with the issues of residential care, to complement existing youth work and therapeutic specialist positions (Ainsworth, 2017; Ainsworth & Hansen, 2018)

- requiring services to structure the residential care environment to better respond to developmental difference and sensory needs (Holden et al., 2014; McLean, 2016)

- requiring greater emphasis paid to effective staff-client interactions in the context of language and intellectual barriers (Manso et al., 2012)

- using 'shared need' as a basis for the commissioning of services and placement of young people; thereby maximising the positive impact of treatment programs and minimising the negative impact of 'contagion' and poor client mix (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2015; Bath 2008a, 2008b).

There is also a growing recognition internationally about the complex needs of young people in residential care. To date, there does not appear to be the same recognition of this specialised need in Australia; nor the corresponding uptake of specialised mental health treatment programs. Similarly, there does not appear to be any consistent or comprehensive assessment of the developmental or mental health needs of young people entering residential care.

In Australia there is still predominantly a reliance on the creation of a trauma-informed culture, and on nurturing relationships as a means of improving young people's lives. There is a clear scope to pilot and evaluate more 'treatment-oriented' models for those young people for whom 'trauma-informed' and 'relationship-based' models are important but may not be sufficient to fully address their needs. Such 'treatment' derived models could remain founded on 'trauma-informed' and 'relationship-based' practice - but also be informed by a comprehensive assessment of shared need for those young people; together with evidence-based interventions matched to need.

d. Prioritising quality relationships between workers and young people

There is growing recognition of the key role that a young person's relationship with staff and their key worker plays in offering an alternative and reparative experience of a relationship. Therapeutic residential care services prioritise quality relationships with young people and value and support young people's existing relationships. The value of safe and predictable caregiving is demonstrated through a consistent care team and consistent rostering. High quality and supportive relationships between young people and staff are foundational to young people's recovery from abuse and neglect by providing an alternative parenting model and an alternative experience of a caregiving relationship (Holden et al., 2010; McLean et al., 2011; Verso Consulting, 2011).

The Verso report (Verso Consulting, 2011) indicated that the quality of young people's relationships with workers, family and the wider community contributed to the superior outcomes found in pilot models of therapeutic residential care; when compared with typical residential care homes. Staff who approached every interaction with young people as an opportunity to build positive relationships and to work through issues were seen as 'crucial' to the success of therapeutic residential care (Verso Consulting, 2011, p. 5). A cost-benefit analysis completed as part of the evaluation reported potential benefits in terms of reduced demand for crisis services and intensive intervention services such as secure welfare, youth justice, police and the courts (Verso Consulting, 2011).

One challenge for therapeutic residential care service models in the future is the question of how 'relational' models co-exist and compliment mental health and behavioural interventions.

4. An understanding of the effective elements of therapeutic residential care

Collectively, the body of knowledge about the elements that make residential care therapeutic and effective is growing. There are three bodies of literature that inform the evidence base for these elements:

- international literature outlining the effective elements of treatment models of residential care

- international literature on the effective elements of residential group homes

- a smaller body of literature on Australian therapeutic residential care.

Collectively, this literature suggests that the following elements contribute to therapeutic outcomes for young people:

- where young people's needs are well understood

- where this understanding is shared by key stakeholders

- where young people's needs are similar, not disparate, leading to good client 'mix' and minimising 'contagion'

- where there is specialist input and appropriate staffing (Verso Consulting, 2011)

- where the therapeutic input is tailored to, and matched to, young people's developmental, cognitive or socio-emotional functioning

- where there is best possible involvement with family and community

where adult-child relationships are valued and continued post-care.

(Ainsworth & Hansen, 2018; Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016; Knorth et al., 2008; McLean, 2016; Whittaker et al., 2016)

Internationally, several models of therapeutic residential care have been identified by the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (CEBC) as either promising or supported by evidence (see Box 2). While these models all differ in important ways, most have the following in common:

- Emphasis is on the therapeutic culture and positive, safe relationships between young people and staff (Holden et al., 2010). Physical and psychological safety is a priority - residential care 'does no further harm' (Whittaker et al., 2016).

- Emphasis is placed on all staff sharing a common understanding and approach to young people's behaviour (Holden et al., 2010). Extensive training is provided to facilitate common, agency-wide understanding of young people's difficulties (Holden et al., 2010; McDonald & Millen, 2012).

- There is recognition that most young people in residential care have experienced a wide range of traumatic experiences and disadvantage. Accordingly, emphasis is placed on understanding and responding to the reasons behind the behaviour (Holden et al., 2010; McDonald & Millen, 2012). Emphasis is on both staff and young people being aware of, and regulating, their responses to stressful situations and reminders of trauma (Holden et al., 2010; McDonald & Millen, 2012).

- Emphasis is placed on the development of competencies in young people (e.g. coping skills, emotional regulation, psycho-education about trauma) that are aligned with young people's current developmental level (Holden et al., 2010; Holden et al., 2014).

- Casework that requires staff to include the young person's wider environment is emphasised (e.g. school, family, community) (McDonald & Millen, 2012; McLean et al., 2011); in order to promote strong and vital family and community linkages (Holden et al., 2010; Whittaker et al., 2016).

Practice draws on evidence-informed models that are effective, articulated in policy and practice, and replicable (McDonald & Millen, 2012; Whittaker et al., 2016).

(The key points above were adapted from: Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016; CEBC; Holden et al., 2010; James, 2011; McDonald & McMillen, 2012; McLean, 2016; McLean et al., 2011; Verso Consulting, 2011; Whittaker et al., 2016).

It is worth noting that these international models do not yet appear to have been evaluated in an Australian service setting in any systematic way; and that the Australian context differs significantly to the North American setting across client cohorts and frameworks, including funding, staffing, qualifications and group size.

Box 2: Examples of promising and supported programs in therapeutic residential care

The CEBC periodically reviews the evidence in support of models and programs of care for young people in the child welfare system. Based on these reviews, programs are given a rating from 5 (a concerning practice) through to 1 (well supported by research evidence). A rating of 3 indicates a 'promising' intervention - one that has been demonstrated in at least one study to be superior to a comparison intervention. A rating of 2 indicates a 'supported' intervention - one that has been demonstrated in at least one randomised controlled study to be superior to an appropriate comparison intervention.

Positive Peer Culture model (CEBC rating 2 - Supported)

The Positive Peer Culture treatment model was developed by Vorrath and Brendtro (1985) and forms the basis for many residential programs in North America. It was specifically designed for 'troubled and troubling' youth, in response to the need to deal with negative peer influences among offending youth (James, 2011). The key targeted outcome is the development of a socially motivated orientation of 'care and concern' or social interest orientation. The culture conveys a belief in the capacity of youth to achieve. The focus is not on conforming to authority per se but motivating this via responsibility for actions, reinforcement of prosocial behaviours and peer helping. The aim is to foster a commitment to helping others, and hurtful behaviours are reduced as a by-product. The essential elements are assumed to be:

- the development of a norm of group belonging and responsibility (similar to the home environment)

- group meetings (problem solving using a 'common language' list of problem behaviours)

- the use of community service learning (community service projects in the community)

- a teamwork focus (staff are organised in teams around distinct groups of children).

The evaluation of this model has been limited. One randomised control study demonstrated reduced recidivism and behavioural and social gains relative to control conditions (Leeman, Gibbs, & Fuller, 1993). Reductions in unhelpful cognitive distortions and covert antisocial behaviour have also been found following this intervention (Nas, Brugman, & Koops, 2005).

CARE® model (CEBC rating 3 - Promising)

CARE is a principle-based program designed to enhance the social dynamics in residential care settings through targeted staff development and ongoing reflective practice. Using an ecological approach, CARE aims to engage all staff at a residential care agency to provide developmentally enriched living environments and to create a sense of normality for youth. CARE is supported by a comprehensive evidence-based implementation approach, addressing the entire organisational and service culture, and is delivered and monitored by trained staff over a three-year period. CARE is based on six principles related to attachment theory, trauma recovery and ecological theory. The principles state that child care practices must be:

- relationship-based

- trauma-informed

- developmentally focused

- competence-centred

- family-involved

- ecologically oriented.

A non-randomised evaluation that monitored behavioural incidents across 11 participating agencies found that implementation of the CARE program was associated with changes in levels of youth aggression towards staff, absconding and property damage. There were less consistent findings on self-harm and peer aggression (Holden et al., 2010; Izzo et al., 2016).

Sanctuary® model (CEBC rating 3 - Promising)

The Sanctuary model, originating from the Andrus Children's Centre in New York, is a systems-level approach that targets the entire organisation. The focus is to create a trauma-informed and sensitive environment within which specific trauma-focused interventions can be carried out. Trauma-sensitive organisational structures and trauma recovery frameworks are central to the model. These structures and frameworks support staff to process and address those children's needs that are seen as arising out of a traumatic background. Within the culture, the model uses a 12-week recurring program of weekly explicit psycho-education. The program also engages family members wherever possible.

The core elements include the development of a culture of: non-violence (teaching and modelling safety skills); emotional intelligence (teaching and modelling affect regulation/management skills); inquiry and social learning; shared governance (teaching and modelling self-discipline and appropriate use of authority); open communication (teaching and modelling healthy interactions and boundaries); social responsibility (social connections and healthy attachments); and growth and change (focus on hope, meaning and purpose).

The Sanctuary model has been subject to limited evaluation. When compared with a non-randomised control group (residential treatment as usual), youths who undertook programs based on the Sanctuary model demonstrated improvements in the areas of interpersonal conflict, personal control, verbal aggression and problem-solving skills (Rivard, Bloom, McCorkle, & Abramowitz, 2005). Measures of 'therapeutic culture' at a six-month follow-up also picked up changes on dimensions of the organisational environment that are considered essential to a trauma-sensitive culture.

Stop-Gap model (CEBC rating 3 - Promising)

The Stop-Gap model, originating from the Devereux Centre for Effective Schools in Pennsylvania, is a short-term residential group care model specifically targeted at children with disruptive behaviour disorders (McCurdy & McIntyre, 2004). The program has two main treatment components: (1) the provision of environment-based interventions; and (2) discharge-focused services. Environmental interventions include the use of a token economy (i.e. a reward system for preferred behaviours), academic support, explicit teaching of social skills and problem-solving and anger-management skills. At the same time, active planning related to discharge, such as parent behaviour management training, community integration and ongoing case management, is implemented. More problematic behaviour is addressed by intensive functional behavioural analysis. One preliminary evaluation indicated a reduction in physical restraints at 12 months following program implementation, compared with a matched non-randomised control group (McCurdy & McIntyre, 2004).

Teaching Family model (CEBC rating 3 - Promising)

The Teaching Family model is a well-known model of service delivery originally designed for juvenile offenders but also used for other children with behavioural issues. It is used and researched more extensively than other models of group care (James, 2011) and has formed the basis of many residential services in North America. A modified form of the model was used at Boys Town in Australia (Daly & Dowd, 1992). The model uses teaching parents to provide a family-like atmosphere to residential care. The teaching parents help children to learn positive social interaction and living skills. It is a competency-based skill development program, using clearly defined goals. The carers (or teaching parents) receive support and training as accredited and professionalised carer treatment teams.

Compared with non-matched 'treatment as usual' residential care, this model of care has reported significant differences in academic attainment (Thompson et al., 1996), use of physical restraint (Jones & Timbers, 2003), and observer ratings of parent-child treatment interactions and offending behaviour (Bedlington, Braukmann, Ramp, & Wolf, 1988). It was associated with more favourable discharge characteristics when compared with treatment foster care (Lee & Thompson, 2008).

For more detailed information about these programs, see James (2011) or McDonald and Millen (2012). Descriptions of the Sanctuary, Stop-Gap, Teaching Family and Positive Peer Culture models have been adapted from McLean and colleagues (2011).

5. Development of guiding policies

Since the 2010 inaugural Therapeutic Residential Care Forum, several Australian jurisdictions have published policy and practice documents that outline the requirements and practices in relation to therapeutic care service provision. These developments are summarised below.

New South Wales

New South Wales has recently undergone a strategic review of its residential care services, with a view to developing an evidence-informed practice and evaluation framework (see Family and Community Services, 2017: Verso Report). New South Wales has also published a Therapeutic Care Framework; which includes 16 practice principles that are intended to guide service provision towards improving outcomes for young people in care. It is noteworthy that the distinction between residential and therapeutic residential care, as outlined in this paper, will be replaced by the term intensive residential care in future tendering processes (Bath, 6 May 2018, personal communication).

Queensland

Queensland has made significant steps towards identifying and operationalising the core elements of therapeutic residential care. This began with the publication of Queensland's Contemporary model of residential care (Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services [DCCSD], 2010), which articulated core elements of therapeutic residential care that were comparable to those from Victoria. This was supplemented by policy stipulating the roles of the DCCSD and community service organisations in supporting young people (DCCSD, 2013).

In 2016, The Hope and Healing Framework for residential care was released (PeakCare Queensland, 2016). This provides a vision, principles and theory for offering 'trauma'-informed care. It outlines the phases of the care journey, including the transition out of care; and the therapeutic focus associated with each phase of care. This framework articulates five key domains for therapeutic focus that include:

- the young person (their rights, their voice and their development)

- the young person's connections (service is offered in context of community and culture)

- the residential care environment (interactions with other young people and staff, connected and safe relationships, routines and rituals, purposeful programming and physical space)

- the residential service provider (organisational procedures, staffing, rostering and collaboration with other services)

- working with the wider service system (health, education, disability and child protection).

The Hope and Healing Framework also articulates the respective roles of staff, provider organisations, care teams and child protection staff. The Hope and Healing Framework provides high-level guidance about the principles of therapeutic care and how it is operationalised, while leaving enough scope for procedural differences or difference in practice model between agencies (PeakCare Queensland, 2016).

South Australia

South Australia is currently undergoing a review of its residential care services and work is underway to develop a therapeutic framework to underpin all residential care service delivery in the state; subject to the completion of a consultation process.

Victoria

In Victoria, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has built on positive evaluations of the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of therapeutic homes (Verso Consulting, 2011; Victorian Auditor-General's Office, 2014) in order to clearly operationalise therapeutic concepts into policy and practice.

The DHHS has clearly articulated what is expected from services providing residential care (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016; see Program requirements for the delivery of therapeutic residential care in Victoria) by providing a summary of guiding principles and legislation, and linking these to domains of support for young people in care. This document clearly outlines the organisational features, the elements of program design, therapeutic plans, staffing configurations and physical characteristics of the home required by therapeutic residential care services in the state (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). In particular, the document specifies the role of the therapeutic specialist in providing assessments and therapeutic plans for young people, in addition to providing support for staff in relation to providing therapeutic responses to young people during their stay.

Western Australia

In Western Australia, the Department for Child Protection and Family Support (DCPFS) stipulates that all residential care services must offer a '… coherent therapeutic approach to care and more importantly … a model for organisational change within the facilities' (Department for Child Protection, 2012, p. 2). The recent Building a better future reform plan stipulates that agencies providing OOHC services will be required to demonstrate that services are delivered according to therapeutic principles (DCPFS, 2016). The department's published manuals for residential care - Residential care practice manual: Residential group homes, family group homes and residential care (Sanctuary) framework - endorse the Sanctuary® model of care (Department for Child Protection, 2011, 2012, pp. 3-5) and the use of key workers, active casework and input from psychology and education specialists. Unit managers are required to report monthly to the Director of Residential Care. No information was available in these documents on the criteria for employment or the staffing ratios in residential care homes.

Other jurisdictions

Several other Australian jurisdictions may be delivering therapeutic residential care. At the time of publication, there did not appear to be any current documentation publicly available on this for the Northern Territory, Tasmania or the Australian Capital Territory.

6. Development of workforce initiatives

Commencing in 2017, there have been several initiatives aimed at developing the skills of the residential care workforce. These include:

- minimum qualification initiatives - aimed at establishing minimum qualifications for the residential care workforce

- training initiatives - focused on upskilling the existing workforce.

Both approaches have implications for the sector, in particular for its ability to attract and retain workers. Further to this, two workforce surveys have been completed since 2010, which add to our understanding of the residential care workforce characteristics and needs, and what kind of training might be of benefit.

a. Minimum qualification initiatives

The minimum qualification strategy for residential care workers in Victoria (Department of Health and Human Services, 2017) details the new mandatory minimum qualification requirements to ensure that residential care workers have the necessary skills, qualifications and training to care for vulnerable young people. The strategy stipulates that from 2018 all residential care workers providing direct care to young people will be required to hold or to be undertaking a Certificate IV in Youth and Family Intervention (Residential and Out-of-Home Care) - including a mandatory unit on trauma; or have a recognised equivalent qualification in combination with a short top-up skills course. This workforce strategy is supported by appropriately allocated funding to assist its implementation across Victoria.

Queensland is currently considering the adoption of similar mandatory qualifications and the Queensland Family and Child Commission is driving a workforce strategy and action plan designed to improve workforce capability within child-focused services (see Strengthening our sector strategy & action plans).

New South Wales is believed to be considering implementing a minimum qualification strategy (Bath, 6 May 2018, personal communication); but mandatory qualification initiatives do not appear to be currently under consideration in other Australian jurisdictions.

b. Training initiatives

In Victoria, the Residential Care Learning and Development Strategy (RCLDS) provides training and learning opportunities to residential care workers. Funded by the Victorian Government, the aim of this suite of training programs is to support the development of a stable, skilled and culturally competent workforce. This strategy is supported by the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare who administer a range of applied training relevant to the sector. Other jurisdictions are considering a similar approach; however, the impact of this initiative does not appear to have been evaluated to date.

Queensland is developing a training strategy to support the implementation of the Hope and Healing framework, in collaboration with PeakCare Queensland. In South Australia, the peak body for child and family services (Child and Family Focus SA), in conjunction with the Department for Child Protection, is offering sector training developed by the training arm of the Association for Child and Family Welfare Association (ACWA) (Cert IV in Child Youth and Family Intervention (Residential and Out-of-Home Care Specialisation)). At the present time, there do not appear to be similar training initiatives in other Australian jurisdictions.

Outside Australia, there are a few applied training programs that could be relevant for the Australian therapeutic residential care workforce. These include: a) the Residential Care Matters program; and b) the RESuLT Training program, both originating in the UK. See Box 3 for details of these training materials.

Box 3: Examples of competency-based workforce development packages tailored to therapeutic residential care

Residential Care Matters

The Residential Care Matters program is a set of UK training and resource materials designed to build workforce morale and improve the consistency and quality of care provided to young people in group homes. This program is designed to be delivered either online or in person (in the UK). It consists of 20 modules under seven broad topic areas: values (value base, statement of purpose); planning (arrivals and departures, placement plans and reviews); home environment (daily routine, state of the home); health and emotional wellbeing (building positive relationships, attachment, healthy lives); positive behaviour (making sense of behaviour, setting limits, sanctions and rewards, physical intervention); safeguarding and protecting (preventing abuse, children who runaway or go missing, countering bullying, extremism and radicalisation, child sexual exploitation); and leadership (duties and roles, effective supervision, complaints and representations). An advantage of these training materials is the ability to work through materials online and/or to use modules flexibly according to the needs of the residential home at any given time. For more information, see the Residential Care Matters website. These materials do not appear to have been evaluated to date.

RESuLT Training program

The RESuLT Training program is a social learning theory-based program for staff in young people's group homes that was recommended by the UK Independent Residential Care Review (Narey, 2016). The training aims to enable residential care workers to develop the skills needed to respond appropriately to young people; balancing behaviour management with helping young people develop self-efficacy and skills to be successful beyond leaving care. The curriculum includes skills in promoting a whole-home approach and positive living environment, enhancing self-regulation; positive behaviour support strategies; management of negative and risky behaviour; understanding child development and the impact of abuse and neglect on development; and communication and relationship skills. It teaches these skills through video, role play and practical exercises. This 12-week training package has been independently evaluated (Berridge et al., 2016). This evaluation found that participating workers experienced improvements in team work, and feelings of being valued and respected by colleagues and managers; as well as a better sense of purpose and planning. Young people experienced more praise, and were given greater responsibility, and more positive interactions with staff following training (Berridge et al., 2016), suggesting this is a promising staff training model for staff in residential facilities. Currently this program appears to only be available in the UK. For more information, see the RESuLT Training website.

Implications of qualification and training initiatives for the current workforce

While any initiative designed to support the residential care workforce is likely to be useful; there may also be an argument for implementing applied, competency-based programs such as RESuLT or Residential Care Matters over an approach that mandates a minimum qualification. It is also unclear whether establishing a universal minimum qualification might act as an unintended barrier to recruiting staff into residential care facilities. In particular, it is still unknown at this stage how the roll out of the National Disability Insurance Scheme, and the anticipated demand for disability support workers, will impact on the potential to recruit residential care workers in Australia.

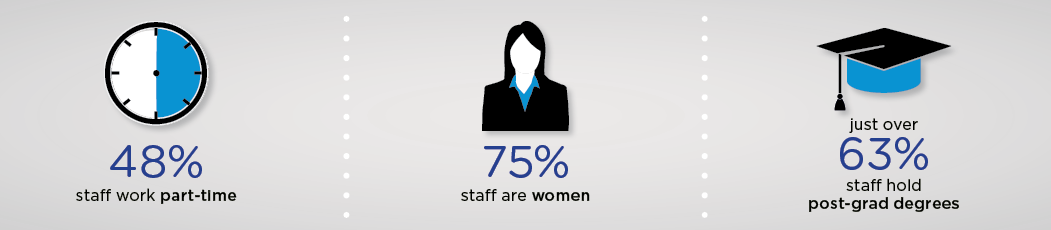

Surveys of workforce characteristics and needs

An audit of Victorian residential care workers in 2012 (sample number not reported) identified that around 38% of the workforce held a Certificate IV in Child, Youth and Family Intervention (Residential and Out-of-Home Care). Around a third of the workforce held a diploma, bachelor or postgraduate degree (Department of Health and Human Services, 2017; see also Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare website: Residential Care Workforce Project), with 68% holding either tertiary qualifications or a Certificate IV. Collectively, this data suggests that many workers are degree qualified, and a comparable proportion have applied qualifications in youth welfare.

In Queensland, the Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services (DCCSDS) funded PeakCare Queensland to deliver a professional development strategy in 2017-18, based on the Hope and Healing Framework. In preparation for this task, PeakCare Queensland administered a workforce survey (from February to June 2017) in order to gain a better understanding of workforce characteristics and needs. Of the workforce sample in this study that provided information about their qualifications (n = 371), 10.5% held Certificate I or Certificate III qualifications and 24% held a Bachelor degree or higher (although not necessarily in a related field). It is worth noting that 31.6% of the total sample did not provide information about their qualifications (n = 170). The available data suggests that at least one-third of respondents would not currently meet the Victorian mandatory qualification strategy (Department of Health and Human Services, 2017), despite many having higher degree qualifications (PeakCare Queensland, 2017).

1 Estimates vary due to variations in how these difficulties are defined, assessed and reported; and variations in sample methodology.

Future issues and dilemmas

As this narrative review indicates, there has been substantial interest in therapeutic residential care and it continues to be a relevant service option for a small cohort of young people in care. This has been accompanied by significant developments in policy and practice in several jurisdictions since 2011, as outlined in this paper.

The need for out-of-home care services, and residential care in particular, to be delivered in the context of a therapeutic framework has been repeatedly emphasised (e.g. Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2011); Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017)). Significant work remains to be done to develop an agreed framework for delivering and evaluating residential care; and a primary concern must be the needs of Aboriginal children and families (Office of the Guardian for Children and Young People, 2015), especially cultural and family connections (Iannos, McLean, McDougall, & Arney, 2013).

This is not to say that existing services do not operate from a clear practice framework. Within the constraints of this brief review, there was no scope to describe examples of existing service models in Australia that hold promise but that have not yet been subject to evaluation or peer review.

At present, there is also not enough known about how Australian therapeutic residential care services are configured in order to make meaningful comparison between services (and, therefore, effective elements) possible. As noted in the introduction, it is hoped that the results of a 2018 survey of existing Australian therapeutic residential care services (McLean, forthcoming) will go some way towards describing existing Australian therapeutic residential care services, and contemporary Australian practice. It is anticipated that the results of this survey will provide a useful description of how Australian services operate at this point of time; and provide useful 'baseline' information that can be built on (in step with developments in this form of service delivery) over time.

There are several ways that the practice of therapeutic residential care can be further developed and these should form the focus of future research and practice partnership activities (McLean et al., 2011; Whittaker et al., 2016).

Operationalising and evaluating therapeutic principles and processes

While concepts such as 'congruence' and 'trauma-informed' have offered the field a common conceptual language, there has not yet been consensus about how these concepts are operationalised in practice. What are the indicators that 'trauma-informed' care is being delivered? What does it look like and how is it measured? Operationalised concepts are observable events and behavioural indicators that can be measured and tracked over time. A focused effort on developing consensus indicators will help to develop the evidence for 'therapeutic' care.

Similarly, there is scope to develop an agreed 'logic model' and evaluation framework for therapeutic residential care, with agreed upon 'inputs' and desired outcomes. Such a model should be flexible enough to incorporate a range of treatment components, based on shared need. This activity will greatly assist in developing the conceptual and empirical basis for therapeutic care in Australia.

There is a pressing need to develop methodologies, reporting standards and programs of research in residential care that will contribute to our understanding of the client base and of effective care; consistent with the recommendations of Lee and Barth (2011) and others (Harder & Knorth, 2014; Lee & Barth, 2014; Whittaker et al., 2016).

Following on from these foundational activities, there is scope to develop more universal standards of accreditation, licensing and quality, including a common set of quality and outcome indicators (Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016).

Defining and refining service models and matching programs to need

The practice in Australia of providing residential care in small houses of between 2-4 young people has both advantages and disadvantages. This service configuration is based on an ideology of providing a 'normal' and 'home-like' environment and offers many advantages. In this model, it may also be more difficult to achieve the kind of oversight that ensures high-quality service provision and guards against adverse interactions between isolated staff and high-needs young people. There may also be a role for larger facilities that can support multidisciplinary service delivery to special groups of young people such as those with an intellectual disability, sexualised behaviour, a conduct disorder or aggressive behaviour, as well as large sibling groups; whose needs may not be addressed well in smaller homes; that lack the 'economies of scale' to bring in specialist support (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2018).

There is a need for foundational research on the mental health, developmental and social-emotional profiles of young people in care (McLean, 2016; Thompson, Duppong Hurley, Trout, Huefner, & Daly, 2017); and to better understand the pathways into and out of residential care (del Valle, Sainero, & Bravo, 2014; Lausten, 2014; Lyons, Obeid, & Cummings 2014; Mendes, Baidawi, & Snow, 2014; Okpych & Courtney, 2014; Stein, 2012; Thoburn & Ainsworth, 2014; Ziera, 2014).

There is a need to collate and share the knowledge base for effective and promising program elements that are matched to young people's needs (Andreassen, 2014; Jakobsen, 2014; James, 2014; McNamara, 2014; Thompson & Daly 2014; Whittaker et al., 2016); in particular, for high-risk behaviours that negatively impact on young people's capacity to experience stable placements; and to fund innovative programs that meet an identified need.

Partnerships between practitioners and qualitative researchers can help unpack the 'black box' of effective therapeutic residential care, especially in regards to the relational aspects of the care environment (see Thompson et al., 2017). For example, there is a need to document best practice in culturally and linguistically competent care; including critical reflection on current practice and its contribution to disparity in culturally diverse young people (Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016). It is also important to explore new and innovative approaches to document young people's experiences; how young people's views of adults and relationships might change over time as a result of high-quality care (Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016); and how the best possible connection with family is facilitated in a statutory setting (Small, Bellonci, & Ramsey, 2014).

Developing the residential care workforce: role identity, skills and knowledge

There is also scope to develop a model of 'youth work' case management for young people in residential care. Such a model should be based in theories of socio-cultural ecology, child development, developmental trauma and socialisation. This may help enhance the professional identity of residential care workers (White, Gibb, & Graham, 2015). Residential care staff may be able to meet young people's needs more efficiently if delegated (albeit prescribed) decision making is devolved to these staff.

It is widely recommended that all young people in residential care have best possible contact with family and up-to-date therapeutic care plans - this will require practitioners to embrace family work and care coordination at some level; either in collaboration with case managers or as a key worker driving this process for young people. These skills may sit outside of their current work roles and 'comfort zone'.

There is a need to develop strategies to attract and retain residential care staff, through training, support and financial incentives, as a means to ensure quality and evidence-based care (Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016; Bravo, del Valle, & Santos, 2014; Grietens, 2014; Holden et al., 2014; Lyons & Schmidt, 2014).

Throughout this work, as outlined in the three points above, strategic partnerships between practitioners and researchers will be necessary in order to build a rigorous evidence base in relation to the integrity, use and evaluation of therapeutic service delivery; and to promote the timely translation of research knowledge directly into residential-care practice settings (Thompson et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Therapeutic residential care is a form of service provision that is increasingly recognised as a treatment of choice for a significant group of young people in care. Our knowledge about the effective elements of therapeutic care is developing, both nationally and internationally. In the future, partnerships between practitioners and researchers, targeting the key issues outlined in this paper, will be an important means of growing the local evidence base and expertise in this cost-intensive form of care. Sustained investment in the development and evaluation of residential care is needed in order to become clearer about how effective this type of service is, and for whom it may be most effective (McLean et al., 2011; Whittaker et al., 2016).

References

Ainsworth, F. (2017). For the few not the many: An Australian perspective on the use of therapeutic residential care for children and young people. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 34(3-4), 325-338.

Ainsworth, F., & Hansen, P. (2015). Therapeutic residential care: Different population, different purpose, different costs. Children Australia, 40(4), 342-347.

Ainsworth, F., & Hansen, P. (2018). Group homes for children and young people: The problem not the solution. Children Australia, 43(1), 42-46. doi:10.1017/cha.2018.4

Andreassen, T. (2014). MultifunC: Multifunctional treatment in residential and community settings. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 100-113). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Anglin, J. (2002). Pain, normality and the struggle for congruence: Reinterpreting residential care for children and youth. Birmingham, NY: Haworth Press.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2017). Young people in child protection and under youth justice supervision 2015-16. (Cat. no. CSI 25). Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW. (2018). Child protection Australia 2016-17 (Child welfare series no. 68). (Cat. no. CWS 63). Canberra: AIHW.

Baker, C. (2007). Disabled children's experience of permanency in the looked after system. British Journal of Social Work, 37, 1173-1188.

Bath, H. (2008a). Residential care in Australia, Part I: Service trends, the young people in care and service responses. Children Australia, 33(2), 6-17.

Bath, H. (2008b). Residential care in Australia, Part II: A review of recent literature and emerging themes to inform service provision. Children Australia, 33(2), 18-36.

Bath, H. (2015). Out of home care in Australia: Looking back and looking ahead. Children Australia, 40(4), 310-315.

Bath, H. (2017). The trouble with trauma. Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care, 16(1), 1478-1840.

Bath, H. (2018, 6 May). Personal communication.

Bazalgette, L., Rahilly, T., & Trevelyn, G. (2015). Achieving wellbeing for looked after children: A whole system approach. London: NSPCC. Retrieved from www.nspcc.org.uk/globalassets/documents/research-reports/achieving-emotional-wellbeing-for-looked-after-children.pdf

Bedlington, M. M., Braukmann, C. J., Ramp, K. A., & Wolf, M. M. (1988). A comparison of treatment environments in community-based group homes for adolescent offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 15(30), 349-363.

Berridge, D., Holmes, L., Wood, M., Mollidor, C., Knibbs, K., & Bierman, R. (2016). RESuLT Training evaluation report. London: Ipsos MORI.

Bloom, S. L. (2005). Creating sanctuary for kids: Helping children to heal from violence. Therapeutic Community: The International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations, 26(1), 57-63.

Boel-Studt, M., & Tobia, L. (2016). A review of trends, research, and recommendations for strengthening the evidence-base and quality of residential group care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33(1), 13-35. doi:10.1080/0886571X.2016.1175995

Braciszewski, J. M., & Stout, R. L. (2012). Substance use among current and former foster youth: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2337-2344. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.011

Bravo, A., del Valle, J. F., & Santos, I. (2014). Helping staff to connect quality, practice and evaluation in therapeutic residential care: The SERAR Model in Spain. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 275-288). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (CEBC). www.cebc4cw.org/

Courtney, M., & Iwaniec, D. (Eds.). (2009). Residential care of children: Comparative perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daly, D. L., & Dowd, T. P. (1992). Characteristics of effective, harm-free environments for children in out-of-home care. Child Welfare, 71(6), 487-496.

Delfabbro, P., Osborn, A., & Barber, J. G. (2005). Beyond the continuum: New perspectives on the future of out-of-home care in Australia. Children Australia, 30(2), 11-18.

del Valle, J. F., Sainero, A., & Bravo, A. (2014). Needs and characteristics of high-resource using children and youth: Spain. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 49-62). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Department for Child Protection. (2011). Residential care practice manual: Residential group homes, family group homes. Perth: Government of Western Australia.

Department for Child Protection. (2012). Residential Care (Sanctuary) Framework. Perth: Government of Western Australia.

Department for Child Protection and Family Support. (2016). Building a better future: Out-of-home care reform in Western Australia. Perth: Government of Western Australia. Retrieved from www.dcp.wa.gov.au/ChildrenInCare/Documents/Building%20a%20Better%20Future.pdf

Department of Communities. (2011). Specialist foster care review: Enhanced foster care literature review and Australian programs description. Queensland: Department of Communities. Retrieved from www.communities.qld.gov.au/resources/childsafety/foster-care/sfc-literature-review-australian-programs-description.pdf

Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services (DCCSD). (2010). Queensland's model of residential care: State-wide consultation and literature review. Brisbane: Department of Communities and PeakCare Queensland.

DCCSD. (2013). Policy: Therapeutic residential care (Policy CPD577-3). Brisbane: DCCSD.

Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2011). An outline of National Standards for out-of-home care. Canberra: Department of Social Services. Retrieved from www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/families-and-children/publications-articles/an-outline-of-national-standards-for-out-of-home-care-2011

Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Program requirements for the delivery of residential care in Victoria. Melbourne: State of Victoria. Retrieved from providers.dhhs.vic.gov.au/search?keys=therapeutic+residential

Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Minimum qualification strategy for residential care workers in Victoria. Melbourne: State of Victoria.

Family and Community Services. (2017a). Therapeutic residential care system development. Sydney: Family and Community Services. Retrieved from www.community.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/381892/System-Design-Redacted-211016-accessible.pdf

Family and Community Services. (2017b). Permanency support (Out of Home Care Program) service overview: Appendix 5. Intensive therapeutic care (ITC). Sydney: Family and Community Services. Retrieved from www.community.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/437733/TAB-F-Appendix-5-Service-Overview-ITC.PDF

Ford, T., Vostanis, P., Meltzer, H., & Goodman, R. (2007). Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: Comparison with children living in private households. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 319-325. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025023

Grietens, H. (2014). A European perspective on the context and content for social pedagogy in therapeutic residential care. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 288-301). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Harder, A. T., & Knorth, E. J. (2014). Uncovering what is inside the 'black box' of effective therapeutic residential youth care. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 217-231). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Hart, D., La Valle, I., & Holmes, L. (2015). The place of residential care in the English child welfare system: Research report. London: Department for Education.

Hill, L., Baker, C., Kelly, B., & Dowling, S. (2015). Being counted? Examining the prevalence of looked-after disabled children and young people across the UK. Child and Family Social Work. doi:10.1111/cfs.12239

Holden, M., Izzo, C., Nunno, M., Smith, E., Endres, T., Holden, J., & Kuhn, F. (2010). Children and residential experiences: A comprehensive strategy for implementing a research informed program model for residential care. Child Welfare, 898(2), 131-149.

Holden, M. J., Anglin, J. P., Nunno, M. A., & Izzo, C. P. (2014). Engaging the total therapeutic residential care program in a process of quality improvement: Learning from the CARE model. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes. (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 301-316). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Iannos, M., McLean, S., McDougall, S., & Arney, F. (2013). Maintaining connectedness: Family contact for children in statutory residential care in South Australia. Communities, Children and Families Australia, 7(1), 63-74.

Izzo, C. V., Smith, E. G., Holden, M. J., Norton, C. L., Nunno, M. A., & Sellers, D. F. (2016). Intervening at the setting level to prevent behavioural incidents in residential child care: Efficacy of the CARE program model. Prevention Science, 17, 554-564. doi:10.1007/s11121-016-0649-0

Jakobsen, T. B. (2014). Varieties of Nordic residential care: A way forward for institutionalized therapeutic interventions? In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 87-100). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

James, S. (2011). What works in group care? A structured review of treatment models for group homes and residential care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 308-321.

James, S. (2014). What works in group care? A structured review of treatment models for group homes and residential care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 301-321.

Jones, R. J., & Timbers, G. D. (2003). Minimizing the need for physical restraint and seclusion in residential youth care through skill-based treatment programming. Families in Society, 84(1), 21-29.

Kelly, B., Dowling, S., & Winter, K. (2012). Disabled children and young people who are looked after: A literature review. Belfast: Queen's University Belfast.

Knorth, E. J., Harder, A. T., Zanberg, T., & Kendrick, A. J. (2008). Under one roof: A review and selective meta-analysis on the outcomes of residential child and youth care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 123-140. doi:10.1016/j. childyouth.2007.09.001

Lange, S., Shield, K., Rehm, J., & Popova, S. (2013). Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in child care settings: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(4), e980-e995.

Lausten, M. (2014). Needs and characteristics of high-resource using children and youth: Denmark. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 73-85). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lee, B. R., & Barth, R. P. (2011). Defining group care programs: An index of reporting standards. Child Youth Care Forum, 40, 253-266. doi:10.1007/s10566-011-9143-9

Lee, B. R., & Barth, R. P. (2014). Improving the research base for therapeutic residential care: Logistical and analytic challenges meet methodological innovations. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 231-245). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lee, B. R., & Thompson, R. (2008). Comparing outcomes for youth in treatment foster care and family-style group care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 746-757.

Leeman, L. W., Gibbs, J. C., & Fuller, D. (1993). Evaluation of a multi-component group treatment program for juvenile delinquents. Aggressive Behavior, 19, 281-292.

Lyons, J. S., Obeid, N., & Cummings, M. (2014). Needs and characteristics of high-resource using youth: North America. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 62-73). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lyons, J. S., & Schmidt, L. (2014). Outcomes management in residential treatment: The CANS approach. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 316-329). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Manso, J. M., Sanchez, E., Alonso, M., & Romero, J. (2012). Pragmatic communicative intervention strategies for victims of child abuse. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 1729-1734. Retrieved from doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.05.003

McCann, J. A., Wilson, S., & Dunn, G. (1996). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in young people in the care system, British Medical Journal, 313, 1529-1530.