Understanding food insecurity in Australia

September 2020

Mitchell Bowden

Download Policy and practice paper

Overview

This practice paper and its companion practice guide describe the prevalence, experience and impact of food insecurity in Australia, identifying the populations most at risk and exploring various responses. Large-scale, structural solutions are required to address the underlying causes of food insecurity; however, smaller-scale service and practice responses are likely to always be required. Child and family welfare service practitioners play an active role in identifying and providing practical assistance to clients experiencing food insecurity and linking them with further supports.

Key messages

-

In Australia, food security is not measured at a population level regularly or consistently. However, estimates suggest that between 4% and 13% of the general population are food insecure; and 22% to 32% of the Indigenous population, depending on location.

-

Some Australians may be more vulnerable to food insecurity, including: low-income earners, people who are socially or geographically isolated, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, culturally and linguistically diverse groups, single-parent households, older people and people experiencing homelessness.

-

For children, food insecurity can have negative short- and long-term effects academically, socially, emotionally, physically and developmentally.

-

The primary reason for food insecurity is material hardship and inadequate financial resources. People can also experience food insecurity due to: difficulty accessing affordable healthy food (e.g. financially or geographically), or limited food and nutrition literacy (e.g. knowing how to purchase and prepare ingredients to make a healthy meal).

-

The strategies required to address food insecurity for all Australians are many and varied. These include policy interventions; local level collaborations; emergency food relief initiatives; school-based programs and education.

Introduction

Food security and insecurity are terms used to describe whether an individual can access food in the quantity and of the quality they need to live an active and healthy life. Food insecurity is commonly considered a concern for developing nations in relation to poverty, agricultural capacity and sustainability. However, it is also an issue for developed nations like Australia where individuals, families and communities experience unequal levels of security in relation to food. While the contributing factors may differ across developed and developing nations, the range of experiences from secure to insecure are seen in both and result in differing manifestations of hunger, physical, social and emotional health implications and coping strategies.

Building on a CAFCA practice paper (Rosier, 2011), this practice paper and its companion practice guide offer insight into the experiences of food security and insecurity specifically in Australia. These resources were produced during a period spanning the 2019/20 bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic. Natural disasters and pandemics can have significant social and economic impacts on affected individuals, families and communities, including their risk of food insecurity. At the time of writing, data are not available on the full impact of these events.

These resources are in two parts. In the practice paper Understanding food insecurity in Australia, it provides a review of the best available evidence on food security in Australia, and synthesises what is known about food insecurity by:

- defining food security and insecurity

- outlining some of the relevant contributing factors

- highlighting the populations within Australia more frequently affected by food insecurity

- describing different lived experiences.

In the practice guide Identifying and responding to food insecurity in Australia, it provides evidence-based and evidence-informed guidance on:

- screening for food insecurity

- supporting individuals and families

- reflecting on and adapting practice.

This practice paper and its companion practice guide are intended for practitioners working with families and households who may be affected by food insecurity to inform service responses.

Methodology

Evidence included in this practice paper was gathered from a range of sources. A comprehensive literature search was conducted on: definitions; affected populations and at-risk groups (including Indigenous peoples, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, low income families, and children); prevalence; causes of food insecurity (including geography, access to food, lack of education and low income); impacts on families and children; intervention strategies (including by government, non-government and community groups), and program examples and evaluations.

The search utilised databases at the Australian Institute of Family Studies, including Academic Search Complete, Australian Family and Society Abstracts, Australian Public Affairs, Business Source Premier, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EconLit, ERIC, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PsycInfo, and SocIndex. The search also used snowballing techniques to identify online resources and grey literature from Australian and international governments or community organisations, such as the AGRICOLA database of the US National Agricultural Library.

Rigorous evaluations of government programs addressing food insecurity were difficult to source. Therefore, it was necessary to draw on a range of sources to identify best-available evidence, including: peer-reviewed journal articles, case studies, literature reviews, program descriptions and analyses, internal organisational evaluations and research institute publications. Despite the limitations of the existing literature, important insights can be gleaned from this information. Unless specified otherwise, most references refer to studies or programs conducted in Australia.

Food security versus food insecurity

While food security is broadly defined as 'when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets the dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life'; food insecurity exists 'whenever the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or the ability to acquire acceptable food in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain' (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Committee on World Food Security, 2012, p. 5).

As such, being food secure is more than having a sufficient quantity of food. It is having access to quality, 'nutritionally adequate and safe' food (Radimer, 2002, p. 2). And, as a fundamental human right, food should also be able to be sourced in ways that are socially acceptable and maintain human dignity. This means that food secure families and individuals can use regular marketplace sources and do not have to resort to emergency food relief and/or begging, stealing or scavenging (Olson & Holben, 2002).

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2006) and the World Health Organization (2011) describe food security as having four dimensions, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The four dimensions of food security

1. Food availability

The reliable supply of appropriate quality food from domestic production or importation, including:

- location of food outlets

- availability of food within stores

- price, quality and variety of available food (Nolan, Rikard-Bell, Mohsin, & Williams, 2006).

2. Food access

The economic and physical capacity to acquire foods that are safe, culturally appropriate and nutritious, including:

- the capacity to buy and transport food

- mobility to shop for food.

3. Food use

The physical, social and human resources to transform food into adequate and safe meals, including:

- the knowledge and skills to decide what food to purchase, how to prepare and consume it, and how to allocate it within a household

- home storage, preparation and cooking facilities

- time available to shop, prepare and cook food

- the use of non-food inputs that are important for wellbeing, such as clean water, hygiene and sanitation, and health care.

4. Food stability and sustainability

The consistent supply of food and the capability to account for risks such as natural disasters, price flux and conflict, including:

- economic stability

- household resilience

- insurance measures against natural disasters and crop failures.

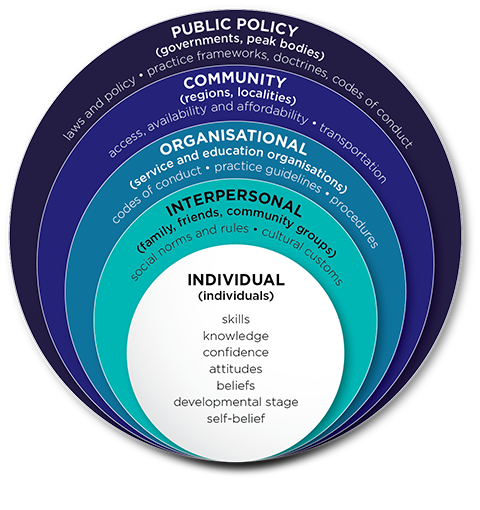

As evident from these four dimensions, there are many factors that affect how individuals, families and communities experience food security and insecurity. Like many public health issues, these factors can be organised according to the degree of individual agency or control (see Figure 2 ). With the individual at the centre of the figure, each consecutive layer moving outwards introduces a set of factors that are increasingly outside of an individual's control. Interventions are necessary at each level in order to address food insecurity for all Australians. However, this paper focuses primarily on outlining best-practice strategies for addressing food security at the individual, interpersonal and organisational levels. It does not aim to detail community or public policy level solutions.

Figure 2: Socio-ecological model of food security

Source: Based on McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz (1988)

Experiences of food insecurity

This section explores Australians' experiences of food insecurity, reviewing how food insecurity is measured in Australia and how these measurements differ in their results, leaving an unclear picture of the true prevalence. It also looks at common experiences and health implications of food insecurity according to severity, and strategies frequently employed by households to cope.

Food security measurement in Australia

At a population level, food security in Australia is not measured regularly. The most recent national measurement taken through the 2011/2013 Australian Health Survey estimated that 4% of all Australians are food insecure (ABS, 2015c). By comparison, 22% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in urban areas, and 31% living in remote areas were also found to be food insecure (ABS, 2015b). This survey used one question to identify food insecurity: 'In the last 12 months was there any time you have run out of food and not been able to purchase more?' (ABS, 2015a). This question did not give an indication of severity (e.g. mild/severe, chronic/transitory). For more insight into severity, respondents who answered 'Yes' were asked whether they, or members of their household, had gone without food as a result. Of those indicating they were food insecure, 2% of all Australians had gone without food (ABS, 2015c). In comparison, 7% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in urban areas and 21% living in remote areas had gone without food (ABS, 2015b). McKechnie, Turrell, Giskes, and Gallegos (2018) highlight that this combined method of measurement potentially underestimates the prevalence of food insecurity in Australia by approximately 5%.

Insights into food security in Australia are available through two longitudinal studies that follow participants over time. The national study Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) and the Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) study ask respondents whether they have had to skip meals due to a shortage of money.

LSAC has followed the experiences of two cohorts of children (born 1999-2000 and 2003-2004) and their families since 2004 (Gray & Smart, 2009). LSAC data shows that on average 1-2% of parent respondents had gone without meals in the previous 12 months due to a shortage of money. This rate was higher among families experiencing socio-economic disadvantage, single-parent households and households where only one parent or no parents were employed.

BNLA follows the settlement experiences of humanitarian migrants who arrived in Australia or received their permanent protection visa between May and December 2013 (De Maio, Silbert, Jenkinson, & Smart, 2014). In their first interview (2013/14), 9% of principal respondents1 reported having gone without meals in the previous 12 months due to a shortage of money. While this decreased over time to 4% five years later, it was still significantly higher than that reported for other groups in the population. Similar socio-demographic factors were noted to increase the risk of a household being food insecure, including single-parent households, unemployment and reliance on government financial assistance.

Australians' experiences of food insecurity are also the topic of academic research. A number of survey instruments are used in research studies on food security in Australia, producing a range of prevalence estimates. For the general population, these estimates range from 4% to 13%. The most recent estimation of the prevalence of 'moderate' and 'severe' food insecurity in Australia using the Food Insecurity Experience Scale2 was 13.4% in 2016-18 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2016). For specific populations, prevalence has been estimated at 2% for older Australians and up to 90% for asylum seekers (McKay & Dunn, 2015; Quine & Morrell, 2006).

Chronic versus transitory food insecurity

Food insecurity can be experienced as chronic or transitory. Chronic food insecurity is experienced by households with incomes that are inadequate to meet their needs. This can be because the total income itself is low, as is the case for those receiving government financial assistance (Temple, Booth, & Pollard, 2019). It can also be because the high cost of other expenses (e.g. housing, energy, transport, health and education) leaves little income for food (Davidson, Saunders, Bradbury, & Wong, 2020). Limited data are available on the experiences of chronic food insecurity. However, as LSAC and BNLA follow families over a number of years, their results provide some insight into these experiences. Across both studies, 3% of respondents reported having gone without meals at two or more time points.

Transitory food insecurity is usually due to a short-term shock. These shocks could include situations such as natural disasters, pandemics (such as COVID-19), or civil unrest (such as strikes) that interrupt food supply for a population and affect local availability. The shocks could also include more immediate factors such as job loss, short-term increases to education or health costs, or unexpected expenses such as car repairs (King, Bellamy, Kemp, & Mollenhauer, 2013).

Both chronic and transitory food insecurity can be cyclical. With chronic food insecurity, the cycle may synchronise with income payments (e.g. food security increasing immediately after payment). With transitory food insecurity, cycles may be longer and linked to key stress points such as school commencement or celebrations (e.g. birthdays, Christmas).

The food security continuum

Food security and insecurity can be conceptualised using a continuum, with four categories ranging from high food security to severe food insecurity (United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, 2006). The lived experience, potential health implications and strategies used to adapt differ for each category (see Table 1).

The health implications of experiencing food insecurity

Food insecurity negatively impacts the physical, mental and social health of adults and children. These consequences may be greater as the severity of food insecurity increases (Tarasuk, Mitchell, McLaren, & McIntyre, 2013). Food insecure households are not only more likely to consume inadequate nutrients and have poorer diets (Kirkpatrick & Tarasuk, 2008), they may also forego healthcare and/or medications due to financial limitations. As a result, food insecure adults are more vulnerable to developing chronic conditions including diabetes, heart disease, obesity, hypertension, arthritis, back problems and poor mental health (Vozoris & Tarasuk, 2003). They may also experience difficulties managing existing chronic health problems.

Coping strategies

Households employ various strategies to cope with food insecurity. These strategies may be income-based (such as increasing employment, selling assets and utilising debt management or financial counselling initiatives) or food-based (see Table 1). Law, Ward, and Coveney (2011) list those food-based strategies used by single parents, including bargain hunting, increasing cooking skills to buy cheaper unprepared food, efficient time use, and relationships with store owners to ensure value for money. Similarly, Ferguson and colleagues (2017) note that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in remote areas often supplement purchased items with food from traditional sources to alleviate food insecurity. Some of these strategies can become adaptive; that is, households integrate them as business as usual and may, therefore, not necessarily identify as being food insecure (Kleve, Booth, Davidson, & Palermo, 2018), which can, in turn, affect help-seeking and the provision of support.

The table can also be viewed on pages 8–9 of the PDF.

Category (Synonyms) | High food security (Food secure) | Mild food insecurity (Marginal food secure) | Moderate food insecurity (Low food security OR food insecure without hunger) | Severe food insecurity (Very low food security OR food insecure with hunger) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lived experience | Households have no problems or anxiety about accessing nutritious, affordable, culturally appropriate food. | Households have problems at times, or are anxious, about accessing adequate food but the quality or quantity of what they are consuming is not substantially interrupted. | Households have reduced the quality and variety of the food they are eating but have not decreased the amount they are consuming. This is usually precipitated by inadequate income for food, given that the food budget is one of the few flexible expenditures. | Households have one or more members with routinely altered eating patterns, including reducing food intake due to a lack of money or other resources. The likelihood of one or more members of the household experiencing hunger is greater in this category. |

| Potential health implications | Optimal health and reduced risks for diet-related conditions. | Worrying and anxiety about where future meals will come from has negative effects on adult and child mental health, child behaviour and development (mediated by parenting practices) (Seivwright, Callis, & Flatau, 2020). | Diet may be altered to include energy dense, nutrient poor foods that can contribute to overweight, obesity and chronic conditions. Diet may also be lacking in diversity resulting in reduced consumption of essential vitamins and minerals contributing to micronutrient deficiencies. | This experience includes aspects of mild and moderate food insecurity but is worsened further by reductions in the size or frequency of meals. This experience can affect the health and wellbeing of pregnant women, in-utero foetal growth and outcomes as well as children's wellbeing, growth and development; manifesting in greater risks for conditions such as asthma, as well as mental illness in adolescence and early adulthood (Kirkpatrick, McIntyre, & Potestio, 2010). |

| Coping strategies | None | Strategies used by households that may not yet be adaptive:

| The coping strategies used by households when they experience mild food insecurity become adaptive. Households may resort to using emergency food relief. | Coping with this level of food insecurity may involve:

In this situation, for households with children, children are often protected for as long as possible, with adults' meals being reduced in size or skipped. It is not until all other options are exhausted that children's meals are reduced in size or skipped. |

1 The BNLA sample was based on the principal applicant in the visa application. Some questions in the questionnaire were only asked of the principal applicant, referred to as the principal respondent.

2 Based on the United States Department of Agriculture's commonly used Household Food Security Survey Module, this scale was developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Populations affected by food insecurity

Food insecurity rarely occurs in isolation but rather alongside economic, health and housing insecurity (Herault & Ribar, 2016). Some population groups (particularly those experiencing disadvantage or vulnerability) are more likely to be food insecure (Smith, Rabbitt, & Coleman-Jensen, 2017; Temple, 2018; Temple et al., 2019).

Some of the populations most at risk include:

- individuals experiencing material and/or financial hardship

- people living in remote areas

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- people from a CALD background, including refugees and people seeking asylum

- single-parent households

- older people

- people experiencing homelessness

- children.

Other non-demographic factors associated with food insecurity can be grouped into two distinct categories (Table 2). While these factors alone can reduce food security, when experienced by the population groups above, they further heighten risk and increase vulnerability.

| Category | Factors |

|---|---|

| Factors associated with diagnosed disorders and disabilities |

|

| Factors associated with social conditions |

|

Individuals experiencing material and/or financial hardship

As discussed in 'Experiences of food insecurity', above, individuals in low-income households are vulnerable to food insecurity, often experiencing challenges in purchasing adequate quantities of food, as well as appropriate healthy food (NSW Council of Social Service, 2018; Ramsey, Giskes, Turrell, & Gallegos, 2011b; Ward, Williams, & Connally, 2013). This is particularly the case for those with lower incomes living in remote areas, relying on government financial assistance or as single parents, who must spend a greater proportion of their disposable income to buy healthy food (Pollard, Savage, Landrigan, Hanbury, & Kerr, 2015; Ward et al., 2013).

This vulnerability is compounded by the rising cost of living (e.g. housing, utilities, petrol) (Foodbank, 2018a). A lack of public or private transport to and from supermarkets or other outlets may also affect those on lower incomes (NSW Council of Social Service, 2018).

The Salvation Army's (2017) national survey3 of individuals accessing its emergency relief and community support services found:

- Over two-thirds (69%) identified their top issue as not being able to afford enough food to eat.

- Almost half (45%) reported they went without meals, went hungry when they ran out of money, and skipped meals to manage finances.

People living in remote areas

Communities in remote areas where food outlets are sparse and/or not well linked to public transport are also at risk of food insecurity (Foodbank, 2018b; National Rural Health Alliance, 2016; Northern Territory Council of Social Services, 2014; Queensland Health, 2014). This is attributable to healthy food being more expensive in rural areas, and even more expensive in remote areas due largely to additional transport and logistics costs for suppliers that are passed on to retailers and, ultimately, customers (Pollard et al., 2015; Ward, Coveney, Verity, Carter, & Schilling, 2012). Foodbank (2018a) estimates those in rural or remote areas are a third more likely to be food insecure than those living in cities. Similarly, Queensland Health's 2014 study found households in remote areas need a significant proportion (26.5%) of their disposable income to afford healthy food. Other issues facing those living in remote areas include:

- food deserts, where a small number of full-service grocery stores exist within a locality (Godrich, Lo, Davies, Darby, & Devine, 2017; NSW Council of Social Service, 2018; Ward et al., 2013)

- fewer large supermarkets forcing dependence on smaller shops that stock a limited range of foods, often at higher prices (Turrell, Hewitt, Patterson, Oldenburg, & Gould, 2002)

- limited connections to appropriate food suppliers, which increases food transport and logistics costs (Australian Red Cross, Dietitians Association of Australia, & Public Health Association Australia, 2013; Davy, 2016; National Rural Health Alliance, 2016)

- a higher density of, or greater access to, take-away food outlets compared to healthier food outlets (Vandenberg & Galvin, 2016).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can be vulnerable to food insecurity. The 2012-13 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey found 22% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were living in a household where someone went without food when household supplies ran out, compared to 3.7% in the non-Indigenous population (ABS, 2015b). Factors that can affect the food security of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people include: low income; household infrastructure and overcrowding; and access to transport, storage and cooking facilities (Browne, Laurence, & Thorpe, 2009).

The majority (79%) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples live in non-remote areas (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2017); with 36.8% living in major cities (Markham & Biddle, 2016). The ABS (2015b) found that 20% of this cohort were living in a household that had run out of food and couldn't afford to buy more, compared to 31% of those living in remote areas. These statistics are similar to the those of other studies (Byrne & Anderson, 2014; Murray et al., 2014; Rogers, Ferguson, Ritchie, Van Den Boogaard, & Brimblecombe, 2018). In remote areas, as noted above (see 'People living in remote areas'), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are less likely to have large supermarkets that benefit from economies of scale and can offer healthy food at affordable prices as a result (Ferguson et al., 2016; Palermo, Walker, Hill, & McDonald, 2008). For example, Ferguson and colleagues (2016) found food products in remote areas were, on average, 60% and 68% more expensive than advertised prices for Darwin and Adelaide supermarkets, respectively.

People from a CALD background, including refugees and people seeking asylum

People from CALD backgrounds are at higher risk of food insecurity (Alonso, Cockx, & Swinnen, 2018). In particular, migrants from refugee backgrounds can be vulnerable to food insecurity due to:

- difficulty finding culturally appropriate food suppliers and unfamiliarity with some Australian foods (Lawlis, Islam, & Upton, 2018; McKay, Bugden, Dunn, & Bazerghi, 2018; Salvation Army, 2017)

- needing to adapt food skills and knowledge because of changes in the way food is sourced and consumed, such as cooking with frozen foods, using new appliances, shopping in new contexts and cooking in a less communal environment (Lawlis et al., 2018; Moffat, Mohamed, & Newbold, 2017)

- challenges encountered during resettlement, including poverty, unemployment, visa conditions, compromised health, language and cultural barriers (Lawlis et al., 2018)

- sending funds to family members remaining in their countries of origin (Gallegos, Ellies, & Wright, 2008)

- restricted access to government financial assistance or work-related income, particularly for asylum seekers (McKay & Dunn, 2015). A study conducted by McKay and colleagues (2018) found that for some asylum seekers with limited or no income, emergency food relief services were the main source of weekly food. The same study also found that despite financial and food insecurity, two-thirds of these asylum seekers were not accessing emergency food relief services. This was attributed to barriers such as: food not being culturally or religiously appropriate; discomfort with taking food from others in need; or transport difficulties.

Single-parent households

Single-parent households experience periods of food insecurity more frequently than other Australian households (Give Where You Live Foundation, 2014; Law et al., 2011; National Rural Health Alliance, 2016; Vandenberg & Galvin, 2016). This may be due to additional time pressures (Law et al., 2011; Queensland Health, 2014) or limited disposable income.

The risk of food insecurity for single-parent households is likely to be heightened by the presence of other factors such as disabilities, mental health difficulties, living in remote areas and relying on government financial assistance (Pollard et al., 2015; Vandenberg & Galvin, 2016). A West Australian study found single-parent households receiving government financial assistance needed 36% of their disposable income to purchase weekly meals (Pollard et al., 2015). Food insecurity resulting from being a single parent is more commonly experienced by women. Foodbank's Hunger report (2018a) highlights food insecure women are 21% more likely than food insecure men (49% compared to 28%) to have raised children on their own for an extended period of time.

Older people

Research findings on older people's vulnerability to food insecurity are mixed. While ageing alone does not necessarily increase risk of food insecurity (Quine & Morrell, 2006; Temple et al., 2019), some factors associated with older people's health and living conditions may make them vulnerable to food insecurity (Forsey, 2018; National Rural Health Alliance, 2016). Australia's National Rural Health Alliance (2016) indicates those aged 70-80 years are at risk of food insecurity when they are reliant on government financial assistance, in rented accommodation and unable to live independently. Other factors that may also place older people at greater risk of food insecurity include: illness, frailness and social isolation (Forsey, 2018); as well as limited mobility, including capability to walk to local food outlets or to lift or carry goods (Burns, Bentley, Thornton, & Kavanagh, 2015; NSW Council of Social Service, 2018; Sorbello & Martin, 2012).

People experiencing homelessness

Homelessness is commonly associated with food insecurity (Chigavazira, et al., 2014; Crawford et al., 2014; Herault & Ribar, 2016). People experiencing homelessness are vulnerable to food insecurity due to a lack of funds to purchase nutritious food and limited facilities for meal preparation (Chigavazira et al., 2014). Despite a greater proportion of women generally experiencing food insecurity (27% compared to 18% of males) (Foodbank, 2018a), Herault and Ribar (2016) found the association between homelessness and food insecurity is stronger for men than women. Additionally, Crawford and colleagues (2014) identified various barriers that particularly impact the food security of young people experiencing homelessness including: living in poverty or with low income; low access to affordable, healthy food stores; and a lack of cooking and storage facilities in temporary accommodation (e.g. community housing, private rentals or friend's/family's homes).

Children

A study by Foodbank (2018b) found children are more likely to live in a food insecure household (22%) than adults (15%). As children are generally protected by adults for as long as possible, food insecurity among children is a potential indicator of greater severity in household food insecurity (Knowles, Rabinowich, De Cuba, Cutts, & Chilton, 2016).

Children are particularly at risk if they are living in households affected by any of the factors in this section. For example, a study by Godrich and colleagues (2017) on the prevalence of food insecurity among rural and remote West Australian children found around one-fifth of children to be food insecure; particularly those whose family relied on government financial assistance or lived in a low socio-economic area. For children, food insecurity can mean: going without meals or fresh food; eating meals at other family members' houses; and attending school without breakfast (Foodbank, 2018a; Foodbank, 2018b). This can negatively impact children's physical health, their social and emotional wellbeing, and their academic achievement.

Health issues

Children from food insecure households may experience poorer general health compared to their food secure counterparts (Holley & Mason, 2019). Internationally, and in Australia, children experiencing food insecurity are:

- approximately twice as likely to have asthma

- almost three times as likely to have iron-deficiency anaemia (Kirkpatrick et al., 2010).

In Australia, childhood experiences of food insecurity have also been linked to:

- the current childhood 'obesity epidemic' (Gill et al., 2009), due to higher consumption of energy-dense foods or additional carbohydrates to compensate for overall lack of food (NSW Council of Social Service, 2018)

- socio-economic inequalities in lifestyle-related chronic diseases in adulthood, such as type-2 diabetes, higher rates of coronary heart disease and some cancers (Ramsey et al., 2011a).

Social, emotional and behavioural issues

A lack of food has been linked to emotional changes such as declines in happiness, irritability, tantrums, hyperactivity, misbehaviour at home and school, increased lethargy, and impacts on sleep (Foodbank, 2018b; Ramsey et al., 2011a). Ramsey and colleagues (2011a) also suggest children from food insecure homes may be up to 2.5 times more likely to experience borderline or atypical emotional and behavioural difficulties. A lack of food has also been linked to children and parents not inviting people to their home due to embarrassment and shame at not having food (Foodbank, 2018b; Ramsey et al., 2011a).

Academic issues

Food insecurity can affect children's school readiness, academic achievement and school attendance, as well as their energy to participate in extracurricular physical activity (Edith Cowan University & Telethon Kids Institute, 2018; Foodbank, 2018b; MacDonald, 2019). Two-thirds (67%) of Australian teachers report having students come to school hungry or without having eaten breakfast, and estimate that these students lose more than two hours a day in learning (Australian Government Department of Education and Training, 2019; Foodbank, 2018b).

3 The Salvation Army's 2017 National Economic and Social Impact Survey explored the levels of disadvantage experienced by those who access its 272 Emergency Relief and Community Support services, with 1,380 respondents.

Conclusion

While it is difficult to capture the full extent of food insecurity in Australia with the figures that are available, some populations are more likely to be food insecure than others. Attending to the personal or household contributors of food insecurity, while important, does not address the origins of the issue. This is because food insecurity rarely happens in isolation but rather in co-occurrence with economic, health and housing insecurity and other hardships (Herault & Ribar, 2016). As such, public policy and community level solutions are required to address food insecurity for all Australians. For child and family welfare service practitioners, strategies responding to food insecurity typically focus on: building food and nutrition literacy through education; alleviating hunger through emerging food relief; and/or partnering to deliver local solutions. Child and family welfare practitioners and services can support food insecure households through sound screening and identification processes, and referrals to appropriate supports.

References

- Aliakbari, J., Latimore, R., Polson, C., Ross-Kelly, M., & Hannan-Jones, M. (2013). A partnership approach to delivering health education in remote Indigenous communities. National Rural Health Conference 2013. Retrieved from www.ruralhealth.org.au/12nrhc/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Latimore-Rachel_Polson-Cara_ppr.pdf

- Allen, L., O'Connor, J., Amezdroz, E., Bucello, P., Mitchell, H., Thomas, A. et al. (2014). Impact of the Social Café Meals program: A qualitative investigation. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 20(1), 79-84.

- Alonso, E., Cockx, L., & Swinnen, J. (2018). Culture and food security. Global Food Security, 17, 113-127.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Food Research and Action Centre (FRAC). (2017). Addressing food insecurity: A toolkit for pediatricians. Washington, D.C.: AAP & FRAC. Retrieved from www.frac.org/wp-content/uploads/frac-aap-toolkit.pdf

- Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC). (2018). Food justice truck. Footscray, Vic.: ASRC. Retrieved from www.asrc.org.au/foodjustice

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2015a). Australian Health Survey: Users' guide, 2011-13 - food security (Catalogue number 4363.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/1F1C9AF1C156EA24CA257B8E001707B5?opendocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015b). Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Nutrition results - food and nutrients (Catalogue Number 4727.0.55.005). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015c). National Health Survey 2011-2012. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/4364.0.55.0092011-12?OpenDocument

- Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS). (2011). The emergency relief handbook: A guide for emergency relief workers, 4th Edition. Strawberry Hills, NSW: ACOSS. Retrieved from acoss.org.au/images/uploads/Emergency_Relief_Handbook_4th_Edition.pdf

- Australian Government Department of Education and Training. (2019). Australian Early Development Census national report 2018. Canberra: Department of Education and Training. Retrieved from www.aedc.gov.au/resources/detail/2018-aedc-national-report

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2017). Australia's welfare 2017: In brief. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/australias-welfare-2017-in-brief/contents/indigenous-australians

- Australian Red Cross. (2018). FoodREDi community nutrition education. Melbourne: Australian Red Cross. Retrieved from www.redcross.org.au/about/how-we-help/food-security/foodredi-education-programs

- Australian Red Cross, Dietitians Association of Australia, & Public Health Association Australia. (2013). Policy-at-a-glance - Food Security for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Peoples Policy. Retrieved from www.phaa.net.au/documents/item/245

- Begley, A. (2018). 2018 Impacts: Food Sensations for Adults. Perth: Foodbank WA. Retrieved from www.foodbank.org.au/ wp-content/uploads/2019/02/FBWA-FSA-Impact-2018.pdf

- Begley, A., Paynter, E., Butcher, L., & Dhaliwal, S. (2019). Examining the association between food literacy and food insecurity. Nutrients, 11(2), 445.

- Booth, S., & Pollard, C. (2020). Food insecurity, food crimes and structural violence: An Australian perspective. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 44(2), 87-88.

- Bowditch, C. (2013). Deadly Mereny Noonak Ngyn Moort: Good food for my people. Mid-term evaluation. 12th National Rural Health Conference. Retrieved from www.ruralhealth.org.au/12nrhc/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Bowditch-Claire_ppr.pdf

- Burns, C., Bentley, R., Thornton, L., & Kavanagh, A. (2015). Associations between the purchase of healthy and fast foods and restrictions to food access: A cross-sectional study in Melbourne, Australia. Public Health Nutrition, 18(1), 143-150.

- Browne, J., Laurence, S., & Thorpe, S. (2009). Acting on food insecurity in urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: Policy and practice interventions to improve local access and supply of nutritious food. Retrieved from pdfs.semanticscholar.org/88fa/cb39cd108e471de0b76e673af92190d695b0.pdf

- Byrne, M., & Anderson, K. (2014). School Breakfast Program: 2013 evaluation report. Retrieved from www.healthyfoodforall.com.au/school-breakfast-program/research-evaluation

- Chigavazira, A., Johnson, G., Moschion, J., Scutella, R., Tseng, Y., & Wooden, M. (2014). Journey's Home research report no. 5: Findings from Waves 1 to 5. Special topics. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. Retrieved from melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2202859/Scutella_et_al_Journeys_Home_Research_Report_W5.pdf

- Chilton, M., Knowles, M., & Bloom, S. (2017). The intergenerational circumstances of household food insecurity and adversity. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, 12(2), 269-297.

- Crawford, B., Yamazaki, R., Franke, E., Amanatidis, S., & Ravulo, J. (2015). Is something better than nothing? Food insecurity and eating patterns of young people experiencing homelessness. Wollongong: University of Wollongong. Retrieved from ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com.au/&httpsredir=1&article=4701&context=sspapers

- Crawford, B., Yamazaki, R., Franke, E., Amanatidis, S., Ravulo, J., Steinbeck, K. et al. (2014). Sustaining dignity? Food insecurity in homeless young people in urban Australia. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 25(2), 71-78.

- Davidson, P., Saunders, P., Bradbury, B., & Wong, M. (2020). Poverty in Australia 2020: Part 1, Overview. (ACOSS/UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership Report No. 3). Sydney: ACOSS. Retrieved from povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Poverty-in-Australia-2020_Part-1_Overview.pdf

- Davy, D. (2016). Australia's efforts to improve food security for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Health and Human Rights, 18(2), 209-218.

- De Maio, J., Silbert, M., Jenkinson, R., & Smart, D. (2014). Building a New Life in Australia: Introducing the Longitudinal Study of Humanitarian Migrants. Family Matters, 94, 5-14.

- Drewnowski A., & Specter, E. (2004). Poverty and obesity: The role of energy density and energy costs. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 79(1), 6.

- Edith Cowan University & Telethon Kids Institute. (2018). Evaluation of the Foodbank WA School Breakfast and Nutrition Education Program: Statewide - Year 2 progress report. Perth: Edith Cowan University. Retrieved from www.foodbank.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FBWA-2018-SBP-Evaluation-Report.pdf

- Fareshare. (2018). Fareshare kitchen garden. Melbourne: Fareshare. Retrieved from www.fareshare.net.au/kitchen-garden/

- Ferguson, M., Brown, C., Georga, C., Miles, E., Wilson, A., & Brimblecombe, J. (2017). Traditional food availability and consumption in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 41(3), 294-298.

- Ferguson, M., O'Dea, K., Chatfield, M., Moodie, M., Altman, J., & Brimblecombe, J. (2016). The comparative cost of food and beverages at remote Indigenous communities, Northern Territory, Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 40(S1):S21-S26.

- Flego, A., Herbert, J., Waters, E., Gibbs, L., Swinburn, B., Reynolds, J., & Moodie, M. (2014). Jamie's Ministry of Food: Quasi-experimental evaluation of immediate and sustained impacts of a cooking skills program in Australia. Retrieved from journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0114673

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FOA). (2006). Policy Brief - Food Security. Geneva: FAO. Retrieved from www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/faoitaly/documents/pdf/pdf_Food_Security_Cocept_Note.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2016). Methods for estimating comparable rates of food insecurity experienced by adults throughout the world. Geneva: FAO. Retrieved from www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/2c22259f-ad59-4399-b740-b967744bb98d

- Food and Agricultural Organization, Committee on World Food Security. (2012). Coming to terms with terminology. Geneva: FAO. Retrieved from www.fao.org/3/MD776E/MD776E.pdf

- Foodbank. (2018a). Foodbank hunger report 2018. North Ryde, NSW: Foodbank. Retrieved from www.foodbank.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-Foodbank-Hunger-Report.pdf

- Foodbank. (2018b). Rumbling tummies child hunger in Australia. North Ryde, NSW: Foodbank. Retrieved from www.foodbank.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Rumbling-Tummies-Full-Report-2018.pdf

- Foodbank. (2018c). Farms to families. Yarraville, Vic.: Foodbank. Retrieved from www.foodbankvictoria.org.au/our-work/farms-to-families/

- Forsey, A. (2018). Hidden hunger and malnutrition in the elderly. London: All Party Parliamentary Groups. Retrieved from www.feedingbritain.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=2e6622e8-c9f6-42a9-be83-1e89f5c2f6a3

- Gallegos, D., Ellies, P., & Wright, J. (2008). Still there's no food! Food insecurity in a refugee population in Perth, Western Australia. Nutrition & Dietetics, 65(1), 78-83.

- Gill, T. P., Baur, L. A., Bauman, A. E., Steinbeck, K. S., Storlien, L. H., Fiatarone Singh, M. A. et al. (2009). Childhood obesity in Australia remains a widespread health concern that warrants population-wide prevention programs. Medical Journal of Australia, 190(3), 146-148.

- Give Where You Live Foundation. (2014). Food for thought: A needs assessment of food assistance in the Geelong region, Victoria. Geelong: Give Where You Live Foundation. Retrieved from www.weebly.com/editor/uploads/6/5/4/4/65449825/466732491938594281_food_for_thought_summary_report_final_2.pdf

- Godrich, S., Lo, J., Davies, C., Darby, J., & Devine, A. (2017). Prevalence and socio-demographic predictors of food insecurity among regional and remote Western Australian children. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 41(62).

- Gooey, M., Browne, J., Thorpe, S., & Barbour, L. (2017). Determining the reach and capacity of rural and regional Aboriginal community food programs in Victoria. Rural and Remote Health, 75, 3573. doi.org/10.22605/RRH3573

- Gray, M., & Smart, D. (2009). Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. A valuable new data source for economists. Australian Economic Review, 42(3), 367-376.

- Herault, N., & Ribar, C. (2016). Food insecurity and homelessness in the Journeys Home survey. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. Retrieved from melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/downloads/working_paper_series/wp2016n15.pdf

- Hollander Analytical Services. (2013). Evidence review: Food security. Canada: Population and Public Health BC Ministry of Health. Retrieved from www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2013/food-security-evidence-review.pdf

- Holley, C., & Mason, C. (2019). A systematic review of the evaluation of interventions to tackle children's food insecurity. Current Nutrition Reports, 8(1), 11-27.

- Huxtable, A., & Whelan, J. (2016). A decade of good food - Café meals in the Geelong region: A ten year reflection. In Council of Homeless Persons (Ed.), Parity: Beyond emergency food. Responding to food insecurity and homelessness. Melbourne: Council of Homeless Persons.

- Kerz, A., Bell, K., White, M., Thompson, A., Suter, M., McKechnie, R., & Gallegos, D. (2020). Development and preliminary validation of a brief household food insecurity screening tool for paediatric health services in Australia. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- King, S., Bellamy, J., Kemp, B., & Mollenhauer, J. (2013). Hard choices: Going without in a time of plenty, a study of food insecurity in NSW and the ACT. Sydney: Anglicare Sydney, the Samaritans Foundation and Anglicare NSW South, Anglicare NSW West & Anglicare ACT.

- Kirkpatrick, S., McIntyre, L., & Potestio, M. (2010). Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Archives of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(8), 754-762.

- Kirkpatrick, S., & Tarasuk, V. (2008). Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. The Journal of Nutrition, 138(3), 604-612.

- Kleve, S., Booth, S., Davidson, Z., & Palermo, C. (2018). Walking the food security tightrope: Exploring the experiences of low-to-middle income Melbourne households. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 2206.

- Knowles, M., Rabinowich, J., De Cuba, S., Cutts, D., & Chilton, M. (2016). "Do you wanna breathe or eat?": Parent perspectives on child health consequences of food insecurity, trade-offs, and toxic stress. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(1), 25-32.

- Law, I., Ward, P. R., & Coveney, J. D. (2011). Food insecurity in South Australian single parents: An assessment of the livelihoods framework approach. Critical Public Health, 21(4), 455-469.

- Lawlis, T., Islam, W., & Upton, P. (2018). Achieving the four dimensions of food security for resettled refugees in Australia: A systematic review. Nutrition & Dietetics, 75, 182-192.

- Lindberg, R., Lawrence, M., Gold, L., Friel, S., & Pegram O. (2015). Food insecurity in Australia: Implications for general practitioners. Australian Family Physician, 44(11), 859-862.

- Loopstra, R. (2018). Interventions to address household food insecurity in high-income countries. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 77(3), 270-281.

- Lovell, R., Husk, K., Bethel, A., & Garside, R. (2014). What are the health and well-being impacts of community gardening for adults and children: A mixed methods systematic review protocol. Environmental Evidence, 3(20), 2047-2382.

- MacDonald, F. (2019). Evaluation of the School Breakfast Clubs Program. Food Bank. Retrieved from www.foodbank.org.au/homepage/who-we-help/schools/?state=vic

- McKay, F. H., Bugden, M., Dunn, M., & Bazerghi, C. (2018). Experiences of food access for asylum seekers who have ceased using a food bank in Melbourne, Australia. British Food Journal, 120(8), 1708-1721.

- McKay, F. H., & Dunn, M. (2015). Food security among asylum seekers in Melbourne. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39(4), 344-349.

- McKechnie, R., Turrell, G., Giskes, K., & Gallegos, D. (2018). Single-item measure of food insecurity used in the National Health Survey may underestimate prevalence in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42(4), 389-395.

- McKenzie, H., & McKay, F. (2018). Thinking outside the box: Strategies used by low-income single mothers to make ends meet. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 53(3), 304-319.

- McLeroy, K., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An Ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 251-377.

- Markham, F., & Biddle, N. (2016). Indigenous population change in the 2016 Census. Canberra: CAEPR, Australian National University. Retrieved from caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/CAEPR_Census_Paper_1_2018.pdf

- Moffat, T., Mohamed, C., & Newbold, K. (2017). Cultural dimensions of food insecurity among immigrants and refugees. Human Organization, 76(1), 15.

- Murray, M., Bonnell, E., Thorpe, S., Browne, J., Barbour, L., MacDonald, C., & Palermo, C. (2014). Sharing the tracks to good tucker: Identifying the benefits and challenges of implementing community food programs for Aboriginal communities in Victoria. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 20, 373-378.

- National Rural Health Alliance. (2016). Food security and health in rural and remote Australia. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved from www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/16-065.pdf

- Nolan, M., Rikard-Bell, G., Mohsin, M., & Williams, M. (2006). Food insecurity in three socially disadvantaged localities in Sydney, Australia. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17(3), 247-254.

- Northern Territory Council of Social Services. (2014). Cost of living report: Tracking changes in the cost of living, particularly for vulnerable and disadvantaged Northern Territorians. The cost of food in the Territory. Nightcliff, NT: NTCOSS. Retrieved from ntcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Cost-of-Living-Report-No.6-Food1.pdf

- NSW Council of Social Service. (2018). Access to healthy food: NCOSS cost of living report. Sydney: NSW Council of Social Service. Retrieved from www.ncoss.org.au/policy/access-to-healthy-food-ncoss-cost-of-living-report-2018

- Olson, C., & Holben, D. (2002). Position of the American Dietetic Associaton: Domestic food and nutrition security. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102, 1840-1847.

- Palermo, C., Walker, K., Hill, P., & McDonald, J. (2008). The cost of healthy food in rural Victoria. Rural and Remote Health, 8(4), 1074.

- Pollard, C. M., Savage, V., Landrigan, T., Hanbury, A., & Kerr, D. (2015). Food Access and Cost Survey, Department of Health, Perth, Western Australia. Perth: Department of Health. Retrieved from www.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Files/Corporate/Reports%20and%20publications/Chronic%20Disease/Food-Access-and-Cost-Survey-Report-2013-Report.pdf

- Queensland Health. (2014). 2014 Healthy Food Access Basket Survey. Brisbane: Queensland Health. Retrieved from www.health.qld.gov.au/research-reports/reports/public-health/food-nutrition/access/overview

- Quine, S. & Morrell, S. (2006). Food insecurity in community-dwelling older Australians. Public Health Nutrition, 9(2), 219-224.

- Radimer, K. (2002). Measurement of household food security in the USA and other industrialized countries. Public Health Nutrition, 5(6A), 859-864.

- Ramsey, R., Giskes, K., Turrell, G., & Gallegos, D. (2011a). Food insecurity among Australian children: Potential determinants, health and developmental consequences. Journal of Child Health Care, 15(4), 401-416.

- Ramsey, R., Giskes, K., Turrell, G., & Gallegos, D. (2011b). Food insecurity among adults residing in disadvantaged urban areas: Potential health and dietary consequences. Public Health Nutrition, 15(2), 227-237.

- Rhodes, A. (2017). RCH National Child Health Poll, Kids and food: Challenges facing families. Melbourne: Royal Children's Hospital. Retrieved from www.rchpoll.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/NCHP9_Poll-report_FA_embargoed.pdf

- Rogers, A., Ferguson, M., Ritchie, J., Van Den Boogaard, C., & Brimblecombe, J. (2018). Strengthening food systems with remote Indigenous Australians: Stakeholders' perspectives. Health Promotion International, 33, 38-48.

- Rosier, K. (2011). Food insecurity in Australia: What is it, who experiences it and how can child and family services support families experiencing it? CAFCA Practice sheet. Melbourne: Communities and Families Clearinghouse Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Salvation Army. (2017). The Hard Road: National Economic and Social Impact Survey 2017. Blackburn, Vic.: Salvation Army. Retrieved from salvos.org.au/scribe/sites/auesalvos/files/ESIS_2017.pdf

- Schembri, L., Curran, J., Collins, L., Pelinovskaia, M., Bell, H., Richardson, C., & Palermo, C. (2016). The effect of nutrition education on nutrition-related health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: A systematic review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 40, S42-S47.

- Schwartz, N., Buliung, R., & Wilson, K. (2019). Disability and food access and insecurity: A scoping review of the literature. Health and Place, 57, 107-121.

- Secondbite. (2018). Who we help. Heidelberg West, Vic.: Secondbite. Retrieved from www.secondbite.org/who-we-help

- Seivwright, A., Callis, Z., & Flatau, P. (2020). Food insecurity and socioeconomic disadvantage in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 559.

- Slade, C., & Baldwin, C. (2016). Critiquing food security inter-governmental partnership approaches in Victoria, Australia. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 76(2), 204-220.

- Smith, M. D., Rabbitt, M. P., & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2017). Who are the world's food insecure? New evidence from the Food and Agricultural Organization's food insecurity scale. World Development, 93, 402-412.

- Sorbello, C., & Martin, C. (2012). Bundaberg Community Food Assessment Report. Journal of the HEIA, 19(1).

- Tarasuk, V., Mitchell, A., McLaren, L., & McIntyre, L. (2013). Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. The Journal of Nutrition, 143(11), 1785-1793.

- Temple, J. B. (2018). The association between stressful events and food insecurity: Cross-sectional evidence from Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 2333.

- Temple, J. B., Booth, S., Pollard, C. M. (2019). Social assistance payments and food insecurity in Australia: Evidence from the Household Expenditure Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 455.

- Testa, A., & Jackson, D. (2019). Food insecurity among formerly incarcerated adults. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 46(10), 1493-1511.

- Turrell, G., Hewitt, B., Patterson, C., Oldenburg, B., & Gould, T. (2002). Socioeconomic differences in food purchasing behaviour and suggested implications for diet-related health promotion. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 15, 355-364.

- United States Government Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (2006). Food security in the U.S: Measurement. Washington, D.C.: Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx#measurement

- Vandenberg, M., & Galvin, L. (2016). Dishing up the facts: Going without healthy food in Tasmania. Retrieved from www.healthyfoodaccesstasmania.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Dishing-up-the-facts-July2016.pdf

- Venn, D., Dixon, J., Banwell, C., & Strazdins, L. (2017). Social determinants of household food expenditure in Australia: The role of education, income, geography and time. Public Health Nutrition, 21(5), 902-911.

- VicHealth. (2011). Food for All 2005-10 program evaluation. Melbourne: VicHeath. Retrieved from www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/media-and-resources/publications/food-for-all-2005-10-program-evaluation-report

- Vozoris, N., & Tarasuk, V. (2003). Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. The Journal of Nutrition, 133(1), 120-126.

- Ward, P., Coveney, J., Verity, F., Carter, P., & Schilling, M. (2012). Cost and affordability of healthy food in rural South Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 12, 1938.

- Ward, A., Williams, J., & Connally, S. (2013). Food for all Tasmanians: Development of a food security strategy. 12th National Rural Health Conference. Retrieved from www.ruralhealth.org.au/12nrhc/program/concurrent-speakers/index.html

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2011). Food security. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved from www.who.int/trade/glossary/story028/en/

- Yeatman, H., Quinsey, K., Dawber, J., Nielsen, W., Condon-Paoloni, D., Eckermann, S. et al. (2013). Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden National Program Evaluation: Final report. Wollongong: University of Wollongong. Retrieved from www.kitchengardenfoundation.org.au/sites/default/files/food%20education/sakgnp_evaluation_uow_finalreport_2012.pdf

- Yii, V., Palermo, C., & Kleve, S. (2020). Population-based interventions addressing food insecurity in Australia: A systematic scoping review. Nutrition and Dietetics, 77(1), 6-18.

This practice paper was updated by Mitchell Bowden, Manager, Engagement and Impact, with the Child Family Community Australia information exchange, AIFS.

The author would like to thank Dr Rebecca Armstrong, former Executive Manager, Knowledge Translation and Impact, AIFS, for her expertise in developing early drafts of this paper, and Sam Morley for his support in developing the early research and drafts of this paper.

The author consulted with Dr Sue Kleve, Professor Danielle Gallegos and Dr Rebecca Lindberg from the Australian Household Food Security Research Collaboration for their expertise on the 'Experiences of food insecurity' and the 'Screening for food insecurity' sections of this practice paper and practice guide.

The 2011 edition of this practice paper was authored by Kate Rosier, Research Officer, AIFS.

Featured image: © GettyImages/marilyna

978-1-76016-209-2