What contributes to placement moves in out-of-home care?

August 2021

Claire Farrugia

Download Policy and practice paper

Summary

Children without a safe and stable home environment require alternative living arrangements and can be placed in out-of-home care (OOHC). The stability of their placement has a significant impact on the child's wellbeing and outcomes. One measure of stability is the number of placements a child has while in OOHC. Understanding what a placement move is and why it happens can help to inform work with children, carers, families of origin and communities.

This paper presents local and international evidence from a scoping review on the factors that influence placement moves for children in OOHC. The paper aims to support practitioners in making evidence-informed placement decisions when working with children and carers in OOHC.

Key messages

-

This review found that a number of factors are likely to increase the risk of a placement move and reduce the duration of first placement. Two key factors are:

- the age at which a child first enters OOHC

- the presence of externalising behaviour, particularly where carers feel at risk.

The review also found that placement in kinship care reduces the risk of a placement move and increases placement stability, especially for older children.

-

The quality of 'parental care' provided by carers also affects placement stability.

-

Evidence is mixed on the impact of placement with siblings on placement stability.

-

There is a significant gap in Australian evidence on risk and protective factors for placement moves for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, who are over-represented in OOHC.

-

Placement stability may be improved by selecting and preparing carers and having regard to the risks of a placement move, particularly in relation to externalising behaviour and those of an older age entering care.

Introduction

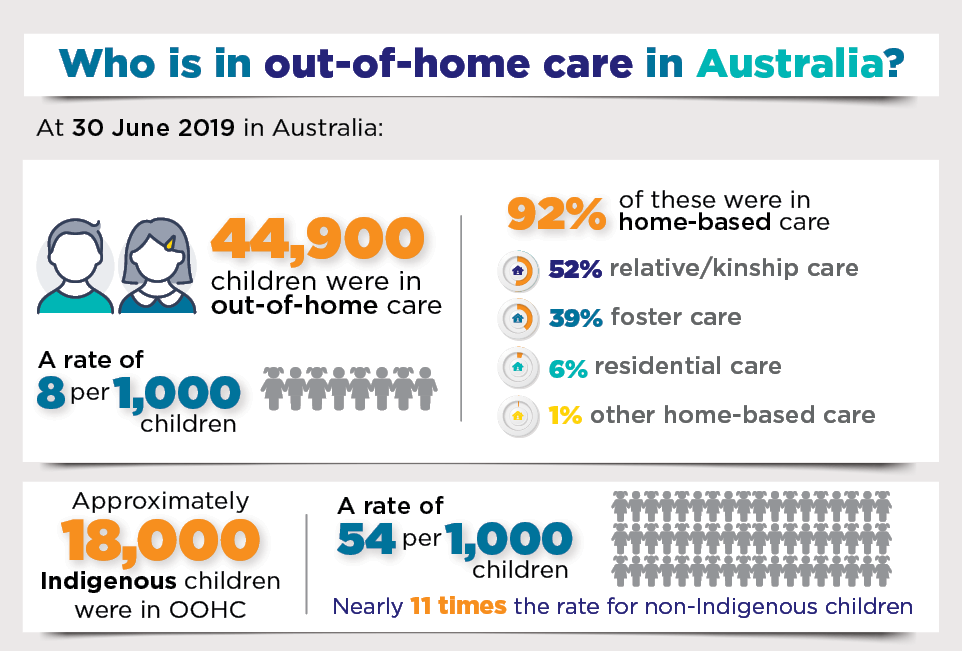

In 2019-20, one in every 33 Australian children received child protection services (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2021). When it is not possible for a child to stay at home with their family due to abuse and neglect, they can be placed in out-of-home care (OOHC) (see Box 1). These arrangements can be formal or informal and for short or extended periods of time (AIHW, 2020).

Placement stability is a critical objective for child family welfare services, and the Australian National Standards for Out-of-home Care outline a set of indicators related to stability that are associated with better outcomes for children in care (Commonwealth of Australia, 2011). Placement stability contributes to a sense of feeling safe and can relate to life more generally, including stability of relationships and connections, stability in schooling, and stability of community and/or participation in community activities such as sports (Commonwealth of Australia, 2011). Children who have had only one or two placements prior to exiting OOHC are considered as a broad indicator of stability that sits under a number of National Framework indicators to ensure children are safe and well in Australia (AIHW, 2020).

Placement stability is associated with better immediate and long-term outcomes during and after children leave care (Strijker, Knorth, & Knot-Dickscheit, 2008). For this reason, the number of placement moves a child experiences is often used as a measure of stability/instability in OOHC (Konijn et al., 2019; Rock, Michelson, Thomson, & Day, 2015). A placement move is considered to have taken place if a child moves to another foster family, other family or kinship care, or residential care placement. A placement move can be planned (e.g. a chance to reunite with kin) or unplanned (e.g. the result of carer sickness or a relationship breakdown between carer and child) (Vreeland et al., 2020). Some moves may be considered in the child's best interest, such as the move to kinship care. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP) is in place to ensure that Indigenous children maintain connections within their own biological family, extended family, community and culture to ensure health, wellbeing and stability.

As such, a placement move can carry a number of different meanings according to child, carer and placement type. However, a placement move may also compound and worsen the difficulties that some children and young people already face in OOHC (Font, Sattler, & Gershoff, 2018; Jedwab, Xu, Keyser, & Shaw, 2019). Children who are removed from their home and find themselves experiencing multiple placements during their OOHC journey are more likely to experience distrust, behavioural difficulties, a lack of securely attached relationships, physical and mental health challenges and academic difficulties (Chambers et al., 2017; Chesmore, Weiler, & Taussig, 2017; Conradi, Wherry, & Kisiel, 2011; Murray, Lacey, Maughan, & Sacker, 2020; Rock et al., 2015; Rostill-Brookes, Larkin, Toms, & Churchman, 2011). Therefore, while the number of moves is only one part of defining stability, it is one that is particularly relevant for caseworkers and managers making decisions about children in OOHC and is the focus of the current paper.

Box 1: What is out-of-home care?

Out-of-home care (OOHC) is overnight care for children aged under 18 who are unable to live with their families due to concerns regarding child safety or parental incapacity. This includes placements approved by the government department bound by relevant child protection legislation. These departments are responsible for child protection for which there is ongoing case management and financial support (including where a financial payment has been offered but declined by the carer).

OOHC includes legal and voluntary placements, as well as placements made for the purpose of providing respite for parents and/or carers. The scope of OOHC reporting has been revised to not account for permanent care and guardianship orders, children on immigration orders, young people aged 18 and over and children in pre-adoptive placements.

Permanent care and guardianship orders are mostly now not counted in OOHC statistics. There are five types of OOHC:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Foster care | Where placement is in the home of a carer who is receiving a payment from a state or territory for caring for a child |

| Relative or kinship care | Where the caregiver is a family member or person with a pre-existing relationship to a child. These arrangements may be formal placements under the child protection system, or informal arrangements that divert children from formal care. |

| Family group homes | Where placement is in a residential building owned by the jurisdiction. These homes are typically run like family homes and have a limited number of children who are cared for around the clock by paid resident carers. |

| Residential care | Where placement is in a residential building where the purpose is to provide placements for children and where there are salaried staff. This category includes facilities where there are rostered staff and where staff live off site. |

| Independent living | Such as private boarding arrangements |

Source: Adapted from Commonwealth of Australia, 2011

Source: AIHW, 2020

Of the children in OOHC placements for two or more years at 30 June 2019, nearly two-thirds of children (10,300 or 62%, excluding New South Wales) had only had one care arrangement in their current episode of care. This measure does not include children previously placed in OOHC who were returned home and re-entered OOHC at a later date. A further 20% had had two care arrangements, 14% had had 3-4 care arrangements, and nearly 5% had had five or more care arrangements (AIHW, 2020). At the national level (excluding New South Wales), the number of placements for children in OOHC care for two or more years varied little by Indigenous status or age (AIHW, 2020). The proportion of children with only one care arrangement varied considerably across states, ranging from 47% in Queensland to 85% in the Australian Capital Territory (AIHW, 2020).

Methodology

A scoping review was conducted following the steps outlined in Arksey and O'Malley (2005) to appraise peer-reviewed and grey literature on the topic. The research question for this paper is: What factors influence placement moves for children in out-of-home care? This question was developed in consultation with practitioners and researchers working in OOHC in Australia.

The search strategy was guided by inclusion criteria (see Appendix A). A range of databases were searched in January 2021 including Web of Science, Scopus and APA PsychInfo. In addition, Google Scholar was searched to include relevant government research reports and increase the scope of Australian data. While the literature review was limited to the years of 2010-20, older Australian literature was included if deemed important to the search topic. The search strategy included a combination of the following key terms: 'out of home care', 'foster care', 'residential care institutions' and 'placement moves'. These terms were combined with 'placement disruption', 'placement instability' and 'placement stability'.

Given the significant variety in studies that focused on elements of 'instability' or 'stability' in OOHC, studies were excluded if they did not provide empirical data or literature reviews related specifically to placement moves. Despite adding rich context to understandings of placement moves, studies or background literature that focused on definitions of 'placement moves', 'instability' or 'stability' or 'placement changes' were excluded if they did not directly contribute to an understanding of the risk and protective factors for placement moves. While 'placement moves' are a change in the physical location of the placement, 'placement changes' can relate to other changes in the placement such as a change in carer or other children entering or exiting the placement.

Across the literature, there are differences in whether a short-term move is counted as a placement move. For example, in one study, if a placement lasted more than two months, this was viewed as a new placement (Tregeagle & Hamill, 2011). A range of studies were included despite differences in how a placement move was defined. Additional exclusion criteria were papers not written or translated into English and those written before 2010.

Data management

Eighteen publications were included in this review. The majority (94.1%) of these were peer-reviewed journal articles originating from Europe (38.8%) and the USA (33.3%). Sample sizes ranged from 19 in qualitative studies to 23,760 in quantitative studies and 666,615 when including systematic reviews. Publications drawing on large sample sizes utilised administrative data from the USA and the UK.

In line with scoping review methodology, this search involved an iterative exploratory process, where early findings informed later searches and revisions to the search criteria. Due to an identified gap in search results, additional targeted searches were conducted in the following areas: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, carer supports and evaluated practitioner interventions. Selected peer-reviewed and grey literature from 2000 to 2010 was included, in addition to the list of included studies, if it provided data relevant to the Australian context of OOHC between 2010 and 2020, and evidence for possible practitioner interventions.

Due to limited and older empirical research on placement moves in OOHC in Australia, the majority of included publications were international. Differences in definitions, legislation and systems of OOHC make direct comparison difficult. The included studies also differ in the time frames used for data collection; for example, a focus on the initial four months of a placement (Barber, Delfabbro, & Cooper, 2001) compared to a retrospective assessment of the journey of a child over a five-year period (Hiller & St Clair, 2018). Different lengths of placement (short-term, permanent), types of care (kinship, foster, residential) and longitudinal or point-of-time studies of children and young people of a variety of ages limits comparison.

A significant gap in the included studies was Australian research relating to peer-reviewed publications on the factors that contribute to placement stability for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC. Relevant grey literature has questioned how concepts such as 'permanence' and 'stability' relate to the experience of Indigenous children and their need for ongoing connection to community, kin and country (Hunter et al., 2020). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP) outlines the vital role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, families and communities to participate in decisions about the safety and wellbeing of children in OOHC (SNAICC, 2018). Independent reviews and government inquiries have identified specific and systemic barriers relating to the placement of Indigenous children in OOHC. Some of these barriers include early intervention placement support for Indigenous children and carers (Davis, 2019) as well as the unmet needs of specific cohorts such as disability support for Indigenous children in OOHC (Commission for Children and Young People [CCYP], 2016). Despite this, no publication focuses on the factors that increase placement moves for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and, as such, this is an identified gap in this paper in need of further research.

What does the evidence tell us?

Age of the child

Eleven studies in this review assessed how the age of a child on entry into care affects the likelihood of a placement move (Barber et al., 2001; Bernedo, García-Martín, Salas, & Fuentes, 2016; Cashmore & Paxman, 2006; Clark, Palmer, Akin, Dunkerley, & Brook, 2020; Font et al., 2018; Jedwab et al., 2019; Jedwab, Xu, & Shaw, 2020; Konijn et al., 2019; Leathers, Spielfogel, Geiger, Barnett, & Vande Voort, 2019; Rock et al., 2015; Vinnerljung, Sallnäs, & Berlin, 2017). Synthesising findings from the included studies is limited by the extent to which researchers defined and clarified the different age ranges of the children included in their studies or reported on the experiences of different age groups. Despite a lack of definitions, the 'older age' of a child was loosely defined as the period of adolescence, generally considered to be between 10 and 18 years of age. Of these studies, six suggested that the older a child is when they enter OOHC, the more likely they are to experience placement disruptions and placement moves, particularly during adolescence (Barber et al., 2001; Cashmore & Paxman, 2006; Font et al., 2018; Jedwab et al., 2019; Jedwab et al., 2020; Leathers et al., 2019).

Jedwab and colleagues (2019) used a representative sample of 4,177 children with an average age of seven years and found that the older the child was when they entered care, the more likely they were to be moved from their initial foster care placement (p < 0.001, HR = 1.01).1 Not only were they more likely to be moved but the older they were, the more likely they were to have a shorter length of first foster care placement (Jedwab et al., 2019; Vreeland et al., 2020). Older children also have more chance of having experienced previous placement moves. In Australia, a 2001 study found age was a significant predictor of placement moves (p < 0.01) for children aged 4-17 years who had experienced one previous placement move and were over the age of 10 when they entered care (Barber et al., 2001).

However, the age of a child in OOHC was found to be a less significant factor influencing placement moves when assessed alongside other case characteristics. A meta-analysis of 42 studies suggested that age was a factor in placement instability but was not as influential as other influencing factors such as a child's behaviour (r = 0.35),2 placement outside kinship care (r = 0.31) or quality of parenting (r = 0.29) (Konijn et al., 2019). Clark and colleagues (2020) also found that the initial reason for removal and the presence of clinically significant trauma symptoms in children were more important factors than the age of a child (OR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.99,1.07], p = 0.129) (Clark et al., 2020).

While studies separate these factors to report on their relative importance, they are not all independent of each other. Additional evidence suggests the following:

- Age at removal is a more important factor in placement moves for children in non-relative foster care and kinship care than for children in residential and group care (Font et al., 2018).

- Age is closely related to disruptive behaviour and it is possible that disruptive behaviour is more tolerated in younger children (Barber et al., 2001; Vreeland et al., 2020) and that older children have unique developmental needs and cumulative trauma that younger children do not (Rock et al., 2015).

Synthesising findings from the included studies is limited by the extent to which researchers defined and clarified the different age ranges of the children included in their studies or reported on the experiences of different age groups.

Externalising behaviour

Externalising behaviour is understood as behaviour that 'outwardly externalises' difficult feelings. For example, hyperactivity, confrontations, substance use and acts of aggression are elements of externalising behaviour (Hiller & St Clair, 2018). These behaviours can be difficult for carers to manage and qualitative research suggests placements of children who exhibit externalising behaviour are more likely to end without placement preparation and support interventions for carers (Gilbertson & Barber, 2003).

Twelve of the included studies assessed the role that externalising behaviour played in the placement moves experienced by children in OOHC (Barber et al., 2001; Clark et al., 2020; Font et al., 2018; Gilbertson & Barber, 2003; Hiller & St Clair, 2018; Jedwab et al., 2019; Khoo & Skoog, 2014; Konijn et al., 2019; Leathers et al., 2019; Rock et al., 2015; Tregeagle & Hamill, 2011; Vreeland et al., 2020). The included studies used alternative terms to describe externalising behaviour; for example, 'disruptive behaviour' (Font et al., 2018) or 'conduct problems' (Hiller & St Clair, 2018), and this contributed to a variation in measures and subsequent findings.

In a recent study from the USA, using a sample of 20,701 children and youth aged 5-19, externalising behaviour had the strongest association with the number of lifetime placements of the child. This study also found that externalising behaviour was the second strongest predictor of the duration of the first placement after a child's age (Vreeland et al., 2020). This finding was confirmed by a meta-analysis of 42 studies looking at foster care placement instability, which found the most significant effects for child behavioural problems (respective to (non-)kinship care, quality parenting, age, and placement with siblings). The meta-analysis confirmed that externalising behaviours had the largest overall effect on instability (medium-to-large effect) in comparison to general behaviour problems (small effect) and internalised problems (medium effect) (Konijn et al., 2019).

In a smaller Australian study, analysis of the reasons for placement change revealed that at least 40 of 125 children from unstable placements experienced at least one placement breakdown due to challenges relating to disruptive behaviour and had a mean number of placements of 5.7 (SD = 4.2)3 in a period of four months (Barber et al., 2001). Two studies suggested that the likelihood of placement moves increased further if the child was also removed from their family of origin due to behavioural issues (Clark et al., 2020; Jedwab et al., 2019). There is a particular risk for older children with externalising behaviour, with Vreeland and colleagues (2020) suggesting that difficult behaviours might be more tolerated in younger children.

The impact of externalising behaviour in the OOHC journey is also directly related to the support and placement planning carers receive (Khoo & Skoog, 2014). Without appropriate support to address a child's specific difficulties, carers can decide to end care (Rock et al., 2015). Leathers and colleagues' (2019) mixed methods study involving qualitative interviews with 139 foster parents suggested that the risk of a placement move due to externalising behaviours only became a significant concern when the child's behaviour posed a risk to others. Risk can be a subjective feeling and includes the threat of physical aggression towards the carer or other children or, in a minority of cases, sexually aggressive behaviours (Leathers et al., 2019). This finding aligns with qualitative findings from a Gilbertson and Barber (2003) study, which found that 14 out of 19 foster carers ended their placement due to feeling unsafe or abused.

Kinship care

Findings from this review suggest that kinship care is associated with greater placement stability relative to other OOHC placements. Six studies reported on the relationship between kinship care as a protective factor against placement breakdown and moves (Font et al., 2018; Gilbertson & Barber, 2003; Jedwab et al., 2019; Jedwab et al., 2020; Konijn et al., 2019; Vinnerljung et al., 2017). Children and young people in kinship care have higher rates of stability than those in non-relative care, including a longer length of first placement, less chance of moving to a second placement and fewer placements in total (Font et al., 2018; Gilbertson & Barber, 2003; Jedwab et al., 2019; Jedwab et al., 2020; Konijn et al., 2019; Vinnerljung et al., 2017).

Konijn and colleagues (2019) conducted a meta-analysis of 42 studies and found that children in kinship care faced fewer placement disruptions and moves. This was particularly the case when kinship care was the first placement for older children - a cohort at particular risk for placement moves (Konijn et al., 2019). Kinship care was identified as a more important factor for placement stability than age of the child, quality of parenting, and sibling placement, but a less important factor than child behavioural problems (Konijn et al., 2019).

In addition to these findings, Winokur, Holtan, and Batchelder's (2014) systematic review of 102 quasi-experimental studies found that children in foster care had 2.6 times the odds of experiencing three or more placement settings as did children in kinship care, and children in kinship care were significantly less likely to re-enter care than were children placed in foster care. Children in kinship care were also found to experience better outcomes regarding behavioural problems and mental health and wellbeing and in overall placement stability (as measured by placement settings, number of placements and placement disruption) (Winokur et al., 2014).

A study of the administrative data of 4,177 children (Jedwab et al., 2019) found that children who were placed in kinship care (42%) experienced a lower rate of placement moves when compared to children in residential care (44%), children in foster homes (52%), children in group homes (64%), and children in the 'other' group - the majority of whom were in different types of intensive care placement, such as inpatient medical care or inpatient psychiatric care (83%, x2 = 195.0, p < 0.001) (Jedwab et al., 2019). The mean length for an initial change was also longer for children in kinship care compared to children in foster and group homes (Jedwab et al., 2019) and children were less likely to have a second out-of-home placement within the first three years of OOHC (Jedwab et al., 2020).

While no studies point to an increased risk of placement moves for children in kinship care, in a study of 136 foster children in Sweden, kinship care was no more stable than non-relative foster care (Vinnerljung et al., 2017). However, this could be a consequence of low statistical power (n = 21 for kinship placements) and further investigation is needed.

Differences in the characteristics of children entering kinship care (vs non-relative foster care) could influence the stability of kinship care. For example, children might be placed in kinship care when they have less disruptive behaviour, and/or there may be more willingness for family to care for a child despite periods of disruptive behaviour (Font et al., 2018). Caseworkers might also be more proactive in preventing the breakdown of kinship placements because they are seen as the most preferable placement to maintain (Gilbertson & Barber, 2003).

There is a lack of research that specifically examines the benefits (or harms) of moving a child from one placement into a kinship placement (Font et al., 2018). Regardless of these limitations, placement with kin seems to be a strong protective factor against placement moves.

Number of previous placements

Five studies included in this review suggest that previous placement moves in OOHC increase the likelihood of subsequent placement moves (Font et al., 2018; Hiller & St Clair, 2018; Jedwab et al., 2019; Leathers et al., 2019; Vinnerljung et al., 2017). However, two studies found that previous placement moves were not a significant risk factor for placement moves when other factors were included (Clark et al., 2020; Konijn et al., 2019). Together, the studies suggest that there is less evidence regarding the number of previous placements after controlling for (taking into consideration) age, externalising behaviour and kinship care placement status.

Children who have experienced a previous care placement have a higher rate of change in placement compared to children without a previous experience (Jedwab et al., 2019). In Font and colleagues (2018), the number of prior placements was associated with increased risk of an unexpected placement move for all placement types except restrictive residential placements. In this sample of children, those children who had been removed from their family of origin more than once faced a greater risk for future placement moves (Font et al., 2018).

Two studies in the review identified that emotional and behavioural difficulties were related to a higher number of previous placements (Hiller & St Clair, 2018; Leathers et al., 2019). In a sample of 139 foster carers caring for children with disruptive behaviours, the children had been in an average of over four previous placements (Leathers et al., 2019). Despite the large number of previous placements, the reasons why having previous placements was a risk factor for future placements were not explored (Barber et al., 2001; Leathers et al., 2019).

Evidence suggests that emotional and behavioural difficulties can both cause placement changes and be the effect of placement changes. The number of previous placements may be a factor in future placement moves because of the close relationship between disruptive behaviour, emotional challenges and previous placement breakdowns (Hiller & St Clair, 2018). This relationship is likely related - emotional difficulties can be hard for carers to know how to manage, particularly if they are under stress, and potentially increase the risk of placement breakdown. At the same time, a placement breakdown can disrupt established support for children, adding to emotional trauma and increasing the risk of future breakdowns, due to decreased trust and capacity to form secure attachments (Leathers et al., 2019).

Placement with siblings

Current available evidence on how placement with siblings affects the likelihood of placement moves is mixed. Five studies assessed whether placement with siblings could act as either a protective or risk factor (Font et al., 2018; Hiller & St Clair, 2018; Konijn et al., 2019; Leathers et al., 2019; Rock et al., 2015). However, considerable variation in the aspects of sibling placement studied (e.g. whether a focus on siblings, reunified siblings, siblings in care, siblings in care at the same time, same number of siblings during the stay in care, history of sibling placements) hampers comparisons across the studies. Despite this limitation, sibling placement is not as significant a factor in placement moves as age, behaviour, kinship care and quality of parenting (Konijn et al., 2019; Leathers et al., 2019).

There are many reasons why a young person may be separated from their siblings in placement. Findings suggest that these reasons align with factors that increase the likelihood of a placement move; for example, if one sibling is demonstrating externalising behaviours that may present a threat to the others.

In a review of studies on OOHC placement moves, placement without siblings increased the risk for placement breakdown (Rock et al., 2015). The included studies suggest a number of reasons why this could be the case. Hiller and St Clair (2018) provided evidence that living separated from siblings was associated with higher internalising and externalising behaviours These behaviours could arise from the emotional difficulties and lack of secure attachment that children experience being separated from their family of origin. Rock and colleagues (2015) found that children feel less secure when separated from their siblings and report missing them as much as their parents. The emotional challenges of being separated from siblings can also influence a child's behaviour.

When other factors such as disruptive behaviour were included alongside sibling placement, there was less evidence that sibling placement was a significant predictor of a placement move in and of itself (Hiller & St Clair, 2018; Leathers et al., 2019). In addition, selected findings suggest that the impact of placement apart from siblings could differ by placement type. Placement apart was protective against placement breakdowns or sudden moves when in non-relative care settings but increased the risk of breakdown and moves in residential and kinship settings (Font et al., 2018).

1 A small p-value (typically ≤ 0.05) indicates strong evidence against a research hypothesis. A large p-value (> 0.05) indicates weak evidence against the hypothesis.

2 r is used to measure correlation, the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables on a scatterplot.

3 Standard deviation helps to understand how spread out a dataset is by measuring how close a set of data is from its average.

Evidence-informed implications for practice

Drawing on the evidence presented above, this section provides evidence-informed implications for service managers and client-facing practitioners. The aim is to support work to reduce the risk of placement moves and maximise stability for children in OOHC. Relevant secondary literature is included to expand on the insights gained from the studies in the review.

Planning for placement stability

Many of the risk and protective factors that linked to placement stability are known at the beginning of a placement and can be considered in planning and supporting the placement. The child's first year of a care placement can require the most support from caseworkers and other services and has the highest risk of placement breakdown (Eastman, Katz, & McHugh, 2018). The needs a child displays in this year can continue to have an impact on their placement in the years following (Hiller & St Clair, 2018). Working to identify children at risk of placement moves and implementing effective interventions can help promote the resilience of carers, children and families of origin (Vreeland et al., 2020).

The following considerations can help mitigate placement instability. These considerations are informed by the broader evidence on placement stability and can help practitioners critically reflect on stability requirements prior to and during a placement (Bernedo et al., 2016; Kalinin, Gilroy, & Pinckham, 2018; Oosterman, Schuengel, Slot, Bullens, & Doreleijers, 2007; Osborn, Delfabbro, & Barber, 2008; Zeijlmans, López, Grietens, & Knorth, 2017):

- Risk and protective factors for placement moves and the compatibility of child, carer and family of origin are assessed. This can be a form of 'Placement Matching' that can help plan for placement success. Matching is a process rather than a one-off event and requires consistent contact with all stakeholders.

- Consider a child's externalising behaviour, age and whether previous placement moves have taken place that could compound behavioural problems (Osborn et al., 2008).

- Place the child with protective factors in mind; for example, the use of kinship care where possible, particularly for older children.

- Carers of children with externalising behaviours or who were older at first placement should be selected carefully, as these placements can be challenging to maintain. Placement support, child counselling and crisis response information can help protect against breakdown.

- Work to ensure cultural connections are prioritised and maintained.

- Consider how to get extra therapeutic or social supports for children with disruptive behaviours and children over the age of five, particularly if there is a history of trauma, abuse or neglect.

- Consider children's views about their placement.

- Value the existing relationships that children have (i.e. broader community, culture, family, school, health practitioners, transportation, friends).

- Ensure casework is responsive and information is shared with all relevant services.

Placing siblings together needs careful consideration in relation to whether it will increase the risk of placement instability or reduce the risk of placement instability. Understand the emotional and social value siblings place on being in OOHC together. Placement decisions are influenced by multiple case factors. Placement moves can be necessary in many situations. The amount of decision-making power that individual practitioners hold can be limited. A lack of available kin and foster families can reduce choices (Zeijlmans et al., 2017).

Placement moves can also reflect policy preferences. This can involve a judgement that the benefits of a placement move outweigh the risks. For example, children in non-relative care being moved into kinship care can be the result of a policy preference for kinship care rather than a problem in the initial placement (Barber et al., 2001; Gilbertson & Barber, 2003). In addition, the implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP) can see a child removed from a non-Indigenous home to preserve an Indigenous child's sense of identity as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. The ATSICPP works to ensure that Indigenous children are maintained within their own biological family, extended family, local Indigenous community and culture.

Poor adherence to the ATSICPP has been identified as a concern in The Family Matters Report 2020: Measuring Trends to Turn the Tide on the Over-Representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Out-Of-Home Care in Australia (Hunter et al., 2020). To assist with its implementation, this Reflective Practice Tool can help practitioners apply a cultural lens and reflect on the application of the five elements of the ATSICPP: connection, participation, prevention, partnership and placement. Prior to entry into care, it is also possible to engage with Indigenous family members to plan for the placement of a child when and if removal is necessary. This type of planning is known as 'parallel planning', 'concurrent planning' or 'twin track' planning and helps to ensure Indigenous children are placed in Indigenous families if they are unable to stay with their parents (Davis, 2019).

Support for carers

While there is a gap in large-scale or high-quality evidence on how the support needs of carers affect placement breakdowns, up to 50% of carers indicated that they either regretted their decision to end the placement or would have had the child returned to their care (Gilbertson & Barber, 2003).

Carers' perceptions of support received from social workers can be associated with placement breakdown (Gilbertson & Barber, 2003), and many foster carers believe that placement breakdowns could be avoided with additional:

- pre-placement information and preparation

- enhanced support during the placement

- greater discussion of alternatives at the end of placement.

Carers come with a range of skills and attributes. Further support may be required for carers to understand the developmental, emotional, behavioural and physical needs of children at different ages. This may include help with:

- managing finances to contribute to the health and wellbeing of the child

- maintaining and managing relationships with birth families

- grief and loss associated with prior placement breakdowns

- the difficulties of engaging with the statutory system

- difficulties accessing specialist support services for children (Blakeslee & Keller, 2016).

Carers should have adequate training in advance of a placement on how to manage externalising behaviour and their own mental health in the face of challenges. Specific advice and training can help preserve the carer-child relationship during externalising behaviour. In particular:

- Training can include the use of effective behaviour management techniques to caregivers during the period when the child is first seeking to adapt to the foster family (Bernedo et al., 2016; Vreeland et al., 2020). The warmth, attentiveness and quality of parenting by carers can help prevent placement breakdowns and moves (Bernedo et al., 2016; Konijn et al., 2019; Leathers et al., 2019).

- Support caregivers to understand links between traumatic experiences and children's behaviour (Clark et al., 2020). In particular, they should understand the role that interpersonal and inter-generational trauma can play for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, young people and families (Menzies & Grace, 2020).

Ongoing training and access to resources can help avoid placement moves due to the carer burning out or the relationship between the carer and child breaking down. Training and resources are available for carers in Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, New South Wales, the Northern Territory, and the Australian Capital Territory from government and non-government sources. National grandparent advisers can assist non-parent carers, such as grandparents, who provide ongoing care for children.

Due to the history of the Stolen Generations and the continued high rates of child removal for Aboriginal children, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers may be cautious about engaging with child protection systems for support. Referral to an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Organisation can be the most appropriate method to convey support in addition to any appropriate resources (Kalinin et al., 2018).

In some states, foster care training is mandatory but kinship care training is optional. Support groups or peer support programs have been found to be useful to kinship carers (Lin, 2014; Thomson, McArthur, & Watt, 2016). There is a lack of research on the needs of kinship carers but identified gaps include:

- additional support to manage birth-family contact due to their own existing family relationships

- additional financial support given that kinship carers generally have a lower socio-economic status than foster carers.

Support for children

How a child understands their placement in OOHC can influence whether they settle into their living arrangements. Large quantitative studies provide limited reference to child participation in the decision to leave a placement. In contrast, smaller qualitative studies suggest that a child's dissatisfaction with a placement and involvement in a placement breakdown can shape feelings of placement stability and impact placement moves (Cashmore & Paxman, 2006; CCYP, 2019; McDowall, 2018; Vinnerljung et al., 2017).

Practitioners can support the greater involvement of children and young people in these ways:

- Identify the children who may need extra support. For example, children who have already moved placements are more likely to have an increased need for socio-emotional support to feel secure (Eastman et al., 2018).

- Encourage young people to have a role in the creation and ownership of their care plan (Greeno, Strubler, Lee, & Shaw, 2018).

- Consider the main types of support/services a child needs, including cultural supports, health services (particularly mental health services), optical, dental, educational and therapeutic services (e.g. counselling, speech, physiotherapy) and recreational activities (Sinclair, Wilson, & Gibbs, 2005).

- Given the mixed evidence on placing siblings together, consultation with the child about what they want would be appropriate, as child dissatisfaction can contribute to the risk of a placement move.

The evidence suggests that extra effort is warranted to support children entering care at older ages and children with externalising behaviours to adapt and settle into a new care placement. This can include caseworkers and carers working to maintain some continuity in social connections for children in care. Continuity in social connections is important for children's attachment and resilience. Continuity has a better chance of being maintained during a placement and placement move if practitioners learn where and with whom the child/young person has social connections and, where possible, how to maintain these connections (Best & Blakeslee, 2020). For example, a positive school climate is protective for children living in difficult family situations (Vreeland et al., 2020). Maintaining children in the school of origin can help ease the impact of placement disruptions as well as prevent future academic difficulty (Clemens, Klopfenstein, Lalonde, & Tis, 2018).

A number of specific techniques can help obtain information about a child's social connections including life story work (Atwool, 2016). Life story work can help children make sense of their situation while decisions are being made about their placement. For example, reflective questions, such as 'Who am I?', 'How did I get here?', and 'Where am I going?', can help make a child more comfortable to participate in decisions that impact their life. Other ways to engage children could involve inviting them to use photos to express their feelings and asking what can be done to help them feel connected to the important people in their life and to their culture (see CFCA article The multiple meanings of permanency).

Box 2 provides a brief overview of findings on child participation from CREATE's 2018 study (McDowall, 2018). The example in Box 2 illustrates a lack of consultation with children and the consequence of the breakdown of the carer-child relationship, which it would be desirable to protect against.

Box 2: Child participation

I was younger, and my carer and myself were having arguments at home. And later on, I was at school and I was called up to the office to find all my bags and boxes packed with all my stuff in it. They removed me from their home and that is how I found out. (Female, 16 years) (cited in McDowell, 2018)

Children in OOHC are not regularly consulted on the placement decisions that shape their lives. In Australia, only 37% of children were consulted before they were moved into their current placement and there were no differences in the number who were consulted from state to state (McDowall, 2018). Those in residential care were least likely to have a say about where they were placed currently (only 21% indicated they had). In contrast, those living independently were more likely to be consulted about care options, because most could be called 'self-placed' and had chosen where they wanted to be (79%) (McDowall, 2018). Of those who had an unwanted change in placement, only 17% had been consulted before that action was taken (McDowall, 2018). In Victoria, more than half of the cases reviewed by the Commission for Children and Young People contained no evidence that children and young people had been consulted about their placement change.

For further information see: Children's Participation in Decision-Making Processes in the Child Protection System: Key Considerations for Organisations and Practitioners and In our own Words: Systemic Inquiry into the Lived Experience of Children and Young People in the Victorian Out-of-Home Care System

Limitations and gaps in findings

The findings and evidence-informed implications of this review must be considered in light of several limitations. Australian evidence on this topic is limited and findings reported in this paper should be considered in light of the reliance on service data that are not always easily generalisable to the Australian context or OOHC in specific Australian states. In particular, there is a significant gap in evidence regarding the experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people, who are over-represented in OOHC. The risk of placement instability for this population may be related to the permanence of their identity in connection with family, kin, culture and country. The availability and retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers, adequate levels of support for carer, child, family of origin and community, and the implementation of the ATSICPP are factors in placement instability that require further qualitative and quantitative research (Kalinin et al., 2018).

Differences in study designs also make comparisons across the included studies difficult. For example, this review included studies using large-scale administrative data from the US (Font et al., 2018) in contrast to an Australian study that focused on one OOHC program (Tregeagle & Hamill, 2011). Administrative databases can differ in measures and indicators. For example, some include only basic demographics and case characteristics, while others include caseworker notes that are valuable for their subjective insight. The differences in these data make it difficult to attribute one reason for a placement move but, as the review has demonstrated, a placement move can involve multiple factors simultaneously.

In addition, the included publications differ in the time frames used for data collection, the length of placement assessed (short-term, permanent), the types of care (kinship, foster, residential) and whether longitudinal or point-of-time studies were used. Finally, there is limited evidence on the evaluation of these strategies to maximise the stability of a placement. The evaluation of community and welfare interventions that look at child, carer and placement outcomes over time and include the voices of children would assist with understanding what works when making placement decisions for children in OOHC.

Conclusion

This paper reviewed available evidence on the factors that influence placement moves for children in OOHC. Australian evidence is limited and many of the included international studies focused largely on demographic and case characteristics of children in foster care, which may not provide a complete understanding of the diversity of children's OOHC journeys.

- This review found that a number of factors are likely to increase the risk of a placement move and reduce the duration of first placement:

- the age at which a child first enters OOHC

- the presence of externalising behaviour, particularly where carers feel at risk.

- The review also found that placement in kinship care , rather than non-relative foster care, reduces the risk of a placement move and increases placement stability, especially for older children.

- The quality of 'parental care' provided by carers affects placement stability.

- Evidence is mixed on the impact of placement with siblings on placement stability.

These risk factors do not act in isolation and can shape the increased likelihood of a child or young person being moved from one placement to another.

The included studies suggest that disruptions in placement may compound and worsen the difficulties that children and young people already face in OOHC. In particular, multiple placement moves have significant consequences for children in OOHC. A greater understanding of the evidence behind the factors that give rise to frequent placement moves, and the factors that protect against frequent placement moves, will help OOHC client-facing practitioners and service managers make evidence-informed decisions. When and if placement breakdowns happen, they are a shared emotional experience between children and carers. Consideration of the social and emotional wellbeing of children and carers can help alleviate distress and maximise placement stability.

In planning placements, it would be beneficial to take additional care with placements that are at greater risk of a subsequent placement move, including selection and preparation of carers, and ongoing support of both carers and children to mitigate the risk of a placement move. Strategies to include children's perspectives in decisions around placements would also be desirable.

Further resources

- Children's attachment needs shape OOHC experiences. Children's Attachment Needs in the Context of Out-of-Home Care provides an overview of what we know, and what needs to be better understood with a particular focus on disorganised attachment, which is thought to be common in high-risk populations.

- The Family Matters Report 2020 measures the trends on the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC in Australia and adherence to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle.

- Child participation has benefits for children, organisations, practitioners and the community. An Overview of Child Participation: Key Issues for Organisations and Practitioners looks at the key factors that practitioners and organisations should consider when consulting children.

- Trauma-Informed Care in Child/Family Welfare Services aims to define and clarify what trauma-informed service delivery means in the context of delivering child/family welfare services in Australia. Exposure to traumatic life events such as child abuse, neglect and domestic violence is a driver of service need.

- A 2020 review of the implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle. Implementation remains poor and limited across states and territories and a number of areas for reform are identified.

References

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

Atwool, N. (2016). Life story work: Optional extra or fundamental entitlement? Child Care in Practice, 23(1), 64-76. doi:10.1080/13575279.2015.1126228

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare(AIHW). (2020). Child protection Australia 2018-19. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2018-19/summary

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2020). National framework for protecting Australia's children indicators. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/nfpac/contents/national-framework-indicators-data-visualisations/4-2-placement-stability

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Child protection in the time of COVID-19. Canberra: AIHW.

Barber, J. G., Delfabbro, P. H., & Cooper, L. L. (2001). The predictors of unsuccessful transition to foster care. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 42(6), 785-790. doi:10.1017/S002196300100751X

Bernedo, I. M., García-Martín, M. A., Salas, M. D., & Fuentes, M. J. (2016). Placement stability in non-kinship foster care: Variables associated with placement disruption. European Journal of Social Work, 19(6), 917-930. doi:10.1080/13691457.2015.1076770

Best, J. I., & Blakeslee, J. E. (2020). Perspectives of youth aging out of foster care on relationship strength and closeness in their support networks. Children and Youth Services Review, 108. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104626

Blakeslee, J. E., & Keller, T. E. (2016). Assessing support network stability with transition-age foster youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(7), 857-868. doi:10.1177/1049731516678662

Cashmore, J., & Paxman, M. (2006). Predicting after-care outcomes: The importance of 'felt' security. Child & Family Social Work, 11(3), 232-241. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00430.x

Chambers, R. M., Crutchfield, R. M., Willis, T. Y., Cuza, H. A., Otero, A., & Carmichael, H. (2017). Perspectives: Former foster youth refining the definition of placement moves. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 392-397. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.010

Chesmore, A. A., Weiler, L. M., & Taussig, H. N. (2017). Mentoring relationship quality and maltreated children's coping. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(1-2), 229-241. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12151

Clark, S. L., Palmer, A. N., Akin, B. A., Dunkerley, S., & Brook, J. (2020). Investigating the relationship between trauma symptoms and placement instability. Child Abuse and Neglect, 108. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104660

Clemens, E. V., Klopfenstein, K., Lalonde, T. L., & Tis, M. (2018). The effects of placement and school stability on academic growth trajectories of students in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 87, 86-94. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.015

Commission for Children and Young People (CCYP). (2016). 'Always was, always will be Koori children': Systemic inquiry into services provided to Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care in Victoria. Melbourne: CCYP.

Commission for Children and Young People. (2019). 'In our own words': Systemic inquiry into the lived experience of children and young people in the Victorian out-of-home care system. Melbourne: CCYP. Retrieved from ccyp.vic.gov.au/assets/Publications-inquiries/CCYP-In-Our-Own-Words.pdf

Commonwealth of Australia. (2011). An outline of National Standards for Out-of-home Care: A priority project under the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020. Canberra: Department of Social Services. Retrieved from www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/pac_national_standard.pdf

Conradi, L., Wherry, J., & Kisiel, C. (2011). Linking child welfare and mental health using trauma-informed screening and assessment practices. Child Welfare, 90(6), 129-147.

Davis, M. (2019). Family is Culture: Independent review into Aboriginal out-of-home-care in NSW. Sydney: Family is Culture, NSW Government.

Eastman, C., Katz, I., & McHugh, M. (2018). Service needs and uptake amongst children in out-of-home care and their carers. Pathways of care longitudinal study: Outcomes of children and young people in out-of-home care. Research Report Number 10. Sydney: NSW Department of Family and Community Services.

Font, S., Sattler, K., & Gershoff, E. (2018). Measurement and correlates of foster care placement moves. Children and Youth Services Review, 91, 248-258. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.019

Gilbertson, R., & Barber, J. G. (2003). Breakdown of foster care placement: Carer perspectives and system factors. Australian Social Work, 56(4), 329-340. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0748.2003.00095.x

Greeno, E. J., Strubler, K. A., Lee, B. R., & Shaw, T. V. (2018). Older youth in extended out-of-home care. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 12(5), 540-554. doi:10.1080/15548732.2018.1431171

Hiller, R. M., & St Clair, M. C. (2018). The emotional and behavioural symptom trajectories of children in long-term out-of-home care in an English local authority. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 106-117. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.017

Hunter, S., Burton, A., Blacklaws, G., Soltysik, A., Nadesha, J., & Bhathal, A. (2020). The Family Matters report 2020: Measuring trends to turn the tide on the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care in Australia. Melbourne: Family Matters.

Jedwab, M., Xu, Y., Keyser, D., & Shaw, T. V. (2019). Children and youth in out-of-home care: What can predict an initial change in placement? Child Abuse & Neglect, 93, 55-65. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.009

Jedwab, M., Xu, Y., & Shaw, T. V. (2020). Kinship care first? Factors associated with placement moves in out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 115, 105104. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105104

Kalinin, D., Gilroy, J., & Pinckham., S. (2018). The needs of carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people in foster care in Australia: A systematic literature review, July 2018. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Khoo, E., & Skoog, V. (2014). The road to placement breakdown: Foster parents' experiences of the events surrounding the unexpected ending of a child's placement in their care. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 13(2), 255-269. doi:10.1177/1473325012474017

Konijn, C., Admiraal, S., Baart, J., van Rooij, F., Stams, G.-J., Colonnesi, C. et al. (2019). Foster care placement instability: A meta-analytic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 96, 483-499. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.002

Leathers, S., Spielfogel, J., Geiger, J., Barnett, J., & Vande Voort, B. (2019). Placement disruption in foster care: Children's behavior, foster parent support, and parenting experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 91, 147-159. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.012

Lin, C. H. (2014). Evaluating services for kinship care families: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 36, 32-41.

McDowall, J. J. (2018). Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people's views after five years of National Standards. Sydney: Create Foundation. Retrieved from create.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CREATE-OOHC-In-Care-2018-Report.pdf

Menzies, K., & Grace, R. (2020). The efficacy of a child protection training program on the historical welfare context and Aboriginal trauma. Australian Social Work, 1-14. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2020.1745857

Murray, E. T., Lacey, R., Maughan, B., & Sacker, A. (2020). Association of childhood out-of-home care status with all-cause mortality up to 42-years later: Office of National Statistics longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 735. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08867-3

Oosterman, M., Schuengel, C., Slot, W., Bullens, R., & Doreleijers, T. (2007). Disruptions in foster care: A review and meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 29, 53-76. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.07.003

Osborn, A. L., Delfabbro, P., & Barber, J. G. (2008). The psychosocial functioning and family background of children experiencing significant placement instability in Australian out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(8), 847-860. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.012

Rock, S., Michelson, D., Thomson, S., & Day, C. (2015). Understanding foster placement instability for looked after children: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(1), 177-203. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct084

Rostill-Brookes, H., Larkin, M., Toms, A., & Churchman, C. (2011). A shared experience of fragmentation: Making sense of foster placement breakdown. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 16, 103-127. doi:10.1177/1359104509352894

Sinclair, I., Wilson, K., & Gibbs, I. (2005). Foster placements: Why they succeed and why they fail. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

SNAICC. (2018). Understanding and applying the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle. Melbourne: SNAICC. Retrieved from www.snaicc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Understanding_applying_ATSICCP.pdf

Strijker, J., Knorth, E. J., & Knot-Dickscheit, J. (2008). Placement history of foster children: A study of placement history and outcomes in long-term family foster care. Child Welfare, 87(5), 107-124.

Thomson, L., McArthur, M., & Watt, E. (2016). Literature review: Foster carer attraction, recruitment, support and retention. Canberra: Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University.

Tregeagle, S., & Hamill, R. (2011). Can stability in out-of-home care be improved? An analysis of unplanned and planned placement changes in foster care. Children Australia, 36(2), 74-80. doi:10.1375/jcas.36.2.74

Trickey, D., Siddaway, A. P., Meiser-Stedman, R., Serpell, L., & Field, A. P. (2012). A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(2), 122-138. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.001

Vinnerljung, B., Sallnäs, M., & Berlin, M. (2017). Placement breakdowns in long-term foster care - a regional Swedish study. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 15-25. doi:10.1111/cfs.12189

Vreeland, A., Ebert, J. S., Kuhn, T. M., Gracey, K. A., Shaffer, A. M., Watson, K. H. et al. (2020). Predictors of placement disruptions in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 99, 104283. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104283

Winokur, M., Holtan, A., & Batchelder, K. E. (2014). Kinship care for the safety, permanency, and well-being of children removed from the home for maltreatment: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 1-292. doi:10.4073/csr.2014.2

Zeijlmans, K., López, M., Grietens, H., & Knorth, E. J. (2017). Matching children with foster carers: A literature review. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 257-265. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.12.017

| Parameters | Inclusion |

|---|---|

| Location | Australia or countries with comparable OOHC systems |

| Language | English |

| Publication date | Jan 2010-Dec 2020. Older studies were included if considered highly relevant. |

| Population | Children and young people in out-of-home care. |

| Publication type | Journal article, report or guideline. |

| Study type | Original research using quantitative and/or qualitative methodology, systematic reviews, narrative reviews and meta-analyses if they included a targeted focus on factors related to placement moves. |

| Keyword searches | Out of home care; foster care; residential care; kinship care; placement moves; placement; placement disruption; placement instability; placement stability; child/ren, young people. |

The table can also be viewed on pages 18–20 of the PDF.

| Author(s) | Country | Publication type | Study design | Methods | Population group and type of care | Number of participants | Factors influencing placement moves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barber et al. (2001) | Australia | Journal article | Longitudinal | Children's baseline and follow-up measures | Children in foster care | 235 | Adolescents with mental health or behavioural problems were the least likely to achieve placement stability defined as either returning (and remaining) home following a single foster placement or assignment to one out-of-home placement only. |

| Bernedo et al. (2016) | Spain | Journal article | Quantitative | Administrative data and interviews with social workers | Children in foster care | 104 | Age at the time of being fostered and the emotional relationship quality between children and foster carers |

| Cashmore & Paxman (2006) | Australia | Journal article | Longitudinal | Interviews with children | Children in foster and kinship care | 47 | Greater perceived emotional security was associated with fewer placements. |

| Clark et al. (2020) | USA | Journal article | Quantitative | National administrative data | Children in foster care | 1,668 | Children with clinically significant trauma symptoms (scores ≥19) had 46% higher odds of experiencing three or more placements during the foster care (OR = 1.46, 95% CI [1.16, 1.82], p = 0.001). Other factors include older age at foster care entry, being male, being Black or another race other than White, and having any type of disability. |

| Font et al. (2018) | USA | Journal article | Longitudinal | Administrative database | Children in foster care | 23,760 | Age at removal was a factor in 'non-progress moves' for children in non-relative foster care. Behaviour problem/delinquency was associated with an 84% or larger increase in risk of a non-progress move in shelter, non-relative and kinship care settings but a (non-significant) 9% increased risk in restrictive settings. Similar patterns were found for mental health problems and cognitive disabilities. |

| Gilbertson & Barber (2003) | Australia | Journal article | Qualitative | Interviews with foster carers | Children in foster care | 19 | System problems including placement breakdown from the decrements associated with serial placement instability and poor placement preparation and support |

| Hiller & St Clair (2018) | UK | Journal article | Quantitative | Service data | Children in long-term care | 217 | Emotional problems, peer problems, conduct problems and hyperactivity in the first year in care contributed to significantly more placement moves than peers on 'resilient trajectories'. A lower number of placement providers significantly predicted increased likelihood of indicators of resilience. |

| Jedwab et al. (2019) | UK | Journal article | Quantitative | Descriptive, bivariate, and survival Cox regression models using administrative data | Children in foster care, residential care and kinship care | 4,177 | Several factors significantly increased the likelihood of an initial change, including: older children (p < 0.001, HR = 1.01), children with behavioural problems (p < 0 .001, HR = 1.26), parental substance abuse (p < 0.05, HR = 1.12), and cases in which the parents voluntarily gave up their parental rights (p < 0.05, HR = 1.12). The type of placement also increased the risk for placement change. |

| Jedwab et al. (2020) | USA | Journal article | Quantitative | Descriptive, bivariate, and regression analyses using administrative data | Children in first kinship care, foster care or group home/residential centre placement | 3,838 | Factors associated with children moving to a second placement are first placement in kinship care (43% moved vs 25% initially placed in non-kin foster care); for children moving from kinship care into non-kinship care, housing issues and parents voluntarily giving up their rights were factors. Older age was associated with increased risk of any placement move. |

| Khoo & Skoog (2015) | Sweden | Journal article | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | Foster carers | 8 | Discrepancy between the statutory obligations of social services toward the foster home and the foster parents' perceptions of support they receive; a lack of individualised service with the right supports for carers |

| Konijn et al. (2019) | The Netherlands | Journal article | Meta-analysis | Systematic review | Children in foster care | Medium significant effects were found for child behavioural problems (r = 0.35), (non-)kinship care (r = 0.31), and quality parenting (r = 0.29). Smaller effects were found for age of the child (r = 0.25), placement with(out) siblings (r = 0.16), and history of maltreatment of the child before placement (r = 0.14). | |

| Leathers (2019) | USA | Journal article | Mixed methods | Interviews and administrative data | Foster parents caring for children | 139 | Foster parents' expectation that they would adopt the child meant lower odds for disruption at the trend level (p = 0.06). Children who had entered the home at a younger age were significantly less likely to experience a disruption. Those cared for by foster parents who were also adoptive parents were less likely to experience a disruption at the trend level (p = 0.09). |

| McDowall (2018) | Australia | Report | Mixed methods | Survey | Children in care | 1,275 | Anglo-Australians have more placement moves than Aboriginal and Torres Strait children. 'Other Cultural Group' experience the most disruption to their placements, but the effect was not significant because of the relatively small numbers in this sample (n = 58) compared with the other groups. |

| Rock et al. (2015) | UK | Journal article | Systematic review | Literature review | Children in foster care | 58 | Older age of children, externalising behaviour, longer total time in care, residential care as first placement setting, separation from siblings, foster care versus kinship care and experience of multiple social workers. Key protective factors included placements with siblings, placements with older foster carers, more experienced foster carers with strong parenting skills, and placements where foster carers provide opportunities for children to develop intellectually. |

| Tregeagle & Hamill (2011) | Australia | Journal article | Mixed methods | Administrative records and interviews | Children in care and social workers | 1,759 records; interviews n/r | Move did not appear to relate to demographic characteristic or length of time in care but unexpected life events (18% of moves) impacting carer households or casework decision-making. |

| Vinnerljung et al. (2017) | Sweden | Journal article | Longitudinal | Administrative case notes | Children in foster care | 136 | Placed after age two; birth sibling in the same foster home; child or the foster parents repeatedly expressed dissatisfaction with the placement |

| Vreeland et al. (2020) | USA | Journal article | Quantitative | Administrative and archival data | Children in foster care | 8,853 | Child internalising and externalising symptoms, school difficulties, youth affect dysregulation, and child age |

| Winokur et al. (2014) | USA | Journal article | Systematic review | Administrative data | Children in foster and kinship care | 102 quasi-experimental studies, with 666,615 children | Placed in foster care a risk to stability; kinship care a protective factor against instability |

All authors are employed by the Australian Institute of Family Studies. Dr Claire Farrugia is a Senior Research Officer and Dr Nerida Joss is the Executive Manager of the Knowledge Translation and Impact Lab.

The authors would like to thank Dr Stewart Muir at the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Dr Susan Baidawi at Monash University for their review and feedback on the paper.

Featured image: © GettyImages/Andrii Atanov

978-1-76016-235-1