What the research evidence tells us about coercive control victimisation

February 2024

Jasmine B. MacDonald, Melissa Willoughby, Pragya Gartoulla, Eliza Cotton, Evita March, Kristel Alla, Cat Strawa

Download Policy and practice paper

Executive summary

Overview

Coercive control is the ongoing and repetitive use of behaviours or strategies (including physical and non-physical violence) to control a current or ex intimate partner (i.e. victim-survivor) and make them feel inferior to, and dependent on, the perpetrator (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety [ANROWS], 2021)1

Coercive control is a relatively new area to policy, practice and research and the research evidence is still emerging. However, AIFS' consultations with key stakeholders in the child and family sector identified coercive control as a key topic of interest for policy makers and practitioners and that there is a desire for a synthesis of current evidence. This paper synthesises the findings of a rapid literature review to describe what we know about how common coercive control victimisation is, as well as risk factors and impacts of coercive control victimisation.2

A victim-survivor3 is someone who has experienced coercive control victimisation (i.e. been the target of coercive control behaviours by a current or ex intimate partner). The term victim-survivor is used to acknowledge 'the ongoing effects and harm caused by abuse and violence as well as honouring the strength and resilience of people with lived experience of family violence' (Victorian Government, 2022).

The findings of the rapid literature review are presented in 3 chapters:

- How common is coercive control victimisation?

- Risk factors associated with coercive control victimisation

- Impacts associated with coercive control victimisation.

The key findings for each of these results sections are summarised in the subsections below. Please refer to the full chapter for more detail, including the evidence synthesis of relevant research studies and implications for practice, research and policy.

Key messages

Quality of coercive control victimisation research

The studies sampled in this review provide important foundational insights about coercive control victimisation but had some limitations. These limitations were related to the relatively early stage of research on coercive control victimisation and the practical barriers associated with research in a complex area of human experience. Based on our review, we made the following observations about the state of evidence on coercive control victimisation in Australia:

- There is a need for research specific to the Australian context. Only a small proportion of the sampled studies (3 out of 13; 23%) explored Australian experiences.

- We currently know little about the unique experiences of:

- Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples

- people with disability

- LGBTQIA+ communities

- culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities

- people in older age groups (65+ years)

- children and young people where there is coercive control between their parents

- intersectional experiences across more than one of the above.

- There is debate among researchers and experts about what exactly coercive control victimisation is and how it should be conceptualised:

- Some studies emphasised the gendered nature of coercive control and others did not.

- Some studies have not used a measure of coercive control but rather a measure of domestic and family violence (DFV), sometimes from a previous study. In such instances, coercive control victimisation is often considered to be synonymous with the experience of psychological or emotional abuse behaviours as distinct from experiences of physical or sexual violence in the DFV measures.

- Others, such as Stark and colleagues (Stark, 2007; Stark & Hester, 2019) and ANROWS (2021), conceptualise coercive control as the context in which intimate partner violence (IPV) occurs, meaning that physical and sexual violence are considered behaviours to enact coercive control (when not occurring in isolated incidence-based abuse).

- Most studies (70%) used customised measurements of coercive control victimisation (i.e. measures constructed by the authors for the purpose of the study). Standardised and psychometrically validated measures were used by only 4 of the 13 sampled studies.

- Research design differences between studies make it challenging to:

- distinguish between IPV characterised by a coercive control pattern and that which is not

- identify coercive control in practice

- inform prevention and intervention

- know which risk factors and impacts are most robust and deserving of further investigation.

- Most studies used a cross-sectional survey method for data collection. These studies cannot demonstrate changes for specific individuals over time or indicate coercive control victimisation causing a change in outcomes such as mental health within the sampled participants. A longitudinal research design is required to demonstrate such changes and potential causation.

- Studies were also characterised by:

- self-report data

- large differences in sample sizes

- an absence of demographic and other relevant social variables in analyses

- a broad range of risk factors and impact measures, with little consistency of measures or replication of findings

- a tendency to focus on individual-level factors associated with victimisation, without equal consideration of broader institutional or societal levels.

How common is coercive control victimisation?

- Because of differences in definitions of coercive control and research design (including participant sampling methods) there is a wide range of figures reported across studies indicating how common coercive control victimisation is. The various design methods used mean it is not possible to know what the true prevalence of coercive control is in the Australian general population.

- In studies examining general population samples, 7.5%-28% of participants may have experienced coercive control victimisation.

- Some studies only examined groups of women who may be at an already increased risk of coercive control, such as those who've accessed domestic violence services, women's shelters, engaged in custody disputes with ex-partners or separated from an abusive partner. These studies find that the frequency rates of coercive control victimisation among these women ranged between 4.4% and 100%.

- The frequency of coercive control victimisation in the single study assessing same-sex relationships in Australia (24%) reported a similar frequency figure to that of the general population samples (28%).

- The available evidence suggests that the frequency of coercive control victimisation may be higher in Australian samples than in other countries. However, this may be because coercive control is better understood and reported in Australia compared to elsewhere. Additionally, the coercive control victimisation research is in an emergent phase, with few studies conducted in Australia. Across international studies there are also limitations and challenges related to the measurement of coercive control, making it difficult to compare findings across studies and countries.

Risk factors associated with coercive control victimisation

- The evidence about risk factors for coercive control victimisation is mixed and somewhat inconclusive. A broad number of risk factors have been assessed but most in only a single study. Where risk factors have been assessed across more than one study, the findings have been inconsistent.

- The mixed findings on risk factors may be a result of researchers using different: (a) definitions of coercive control victimisation, (b) measures of coercive control victimisation, and (c) participant sampling methods (e.g. non-representative methods such as convenience sampling).

- Confidence in findings is required to establish which risk factors warrant greater attention from a practice and policy perspective. Confidence can be increased through: (a) replication across multiple studies and (b) the use of statistical methods comparing multiple risk factors relative to one another.

- Practitioners, researchers and policy makers may want to explore assessing risk factors that have already been established for IPV, and to a lesser extent DFV, due to the close relationship between experiences of coercive control and IPV and DFV.

Impacts associated with coercive control victimisation

- None of the sampled studies examined the impacts of coercive control victimisation in Australia.

- Research on the impacts of coercive control victimisation has been conducted predominantly in Canada and the United Kingdom.

- Mental health outcomes are the most frequently researched impact factors of coercive control victimisation among women. Because of this, they are the most established impact factors, although the quality of the evidence varies. Unsurprisingly, studies generally found that coercive control victimisation was associated with decreases in women's mental health and wellbeing.

- Beyond mental health, the included studies examined a small number of negative impacts on decision-making abilities, family health and wellbeing, physical injury levels, emotional injury levels and amount of time taken off paid work.

- Efforts to improve the rigour of coercive control research are required to better understand coercive control and its effects, as well as for there to be effective translation of research into meaningful supports or actions for victim-survivors.

- Some key gaps in the evidence on victimisation include:

- the impacts of coercive control victimisation among children of victim-survivors

- non-mental health related impacts of coercive control victimisation

- the impacts of coercive control victimisation specific to the Australian population

- more rigorous analysis of the impact of coercive control victimisation over time.

1 For an explanation of the definition of coercive control used in this paper, please refer to the Introduction chapter.

2 For a full description of the steps undertaken to conduct the rapid literature review, please refer to the Method chapter.

3 Victim-survivors are 'Adults, children and young people who have direct first-hand experience of family violence, as well as immediate family members of those who have lost their lives to family violence. This term acknowledges the ongoing effects and harm caused by abuse and violence as well as honouring the strength and resilience of people with lived experience of family violence' (Victorian Government, 2022).

Introduction

Coercive control is increasingly recognised as a public health and safety issue in urgent need of response in Australia (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety [ANROWS], 2021) and globally (Nevala, 2017). As the concept of coercive control, and its relationship to Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), has become better known and understood, policy and legal reforms related to coercive control response and prevention have attracted increasing debate and rapid change. Some states and territories across Australia have taken steps towards criminalising coercive control.4 Although, at the time of writing, there is not a consistent legislative response in Australia, the Commonwealth government has published the draft National Principles to Address Coercive Control.

Effective policy and practice efforts to respond to and prevent coercive control should be informed by high-quality research evidence. However, coercive control is a complex issue and, because the concept is relatively recent, the research evidence in this space is still emerging. AIFS' consultations with stakeholders in the child and family sector identified a desire for more information and evidence about coercive control (outlined further in the Method section). This paper aims to synthesise what is currently known about coercive control victimisation to inform policy and practice. Specifically, this paper aims to synthesise the evidence about how common coercive control victimisation is, as well as the risk factors and impacts of coercive control victimisation.

Synthesising research evidence involves bringing together the findings of multiple studies to describe the most reliable information and to consider what is known and unknown about a topic (Gough et al., 2020). Evidence syntheses aim to provide a holistic overview of the research literature, to inform practice, policy decision making (Gough et al., 2020) and future research. At the time of writing, the peer-reviewed quantitative research evidence on coercive control victimisation and how it applies to the Australian context had not previously been synthesised.

A note on terminology: in this paper, we use the term 'victim-survivor'. A victim-survivor is someone who has experienced coercive control victimisation (i.e. been the target of coercive control behaviours by a current or ex intimate partner). The term victim-survivor is used to acknowledge 'the ongoing effects and harm caused by abuse and violence as well as honouring the strength and resilience of people with lived experience' (Victorian Government, 2022).

Structure of this paper

This paper has 8 sections:

- Glossary: provides definitions of key terms and acronyms used in this paper.

- Introduction: explains the aims and focus of this paper, defines coercive control and summarises qualitative insights from Australian literature on what coercive control looks like.

- Why it is important to understand coercive control victimisation: provides a rationale for why it is important to understand coercive control victimisation and the consequences for victim-survivors of a lack of understanding.

- The nature of the evidence base: summarises the characteristics of the studies included in the rapid review and key reflections on the quality of research conducted to date.

- How common is coercive control victimisation? provides a summary of the main insights about the frequency of coercive control victimisation in the general population and clinical samples, as well as implications for practice, research and policy, together with detail on the findings of studies assessing prevalence.

- Risk factors associated with coercive control victimisation: provides a summary of the main risk factors for coercive control victimisation, and implications for practice, research and policy. The rest of the chapter provides more detail on the findings of studies assessing risk factors.

- Impacts associated with coercive control victimisation: provides a summary of the main impacts of coercive control victimisation and implications for practice, research and policy. The rest of the chapter provides more detail on the findings of studies assessing impacts.

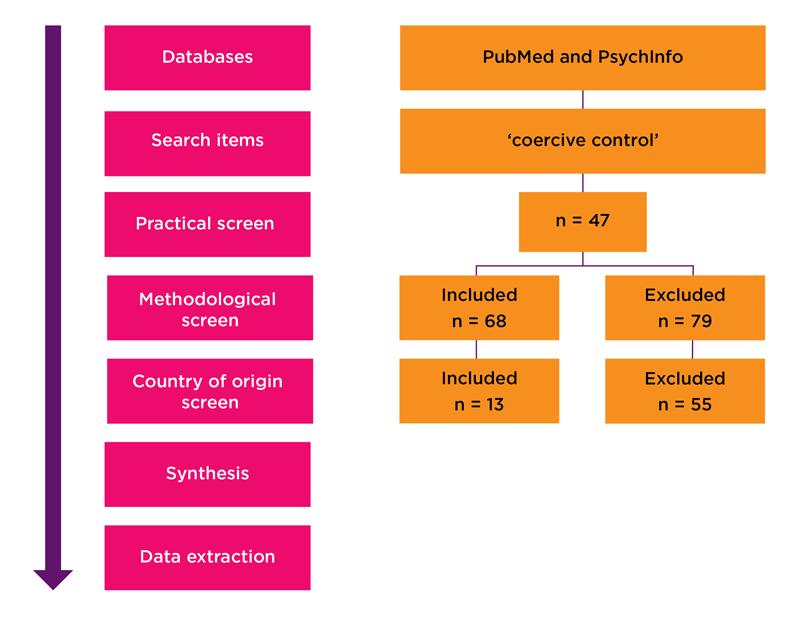

- Method: How the rapid literature review was conducted: describes the method used to conduct the rapid literature review. It also describes the stakeholder engagement that informed the rapid literature review as well as potential limitations to be considered in future literature reviews on coercive control victimisation.

Definition of coercive control used in this paper

Even though the need to address coercive control is becoming more widely recognised, there is no single, consistently used definition of coercive control. A previous literature review found that there were 22 different measures and definitions of coercive control used by researchers (Hamberger et al., 2017). A particular point of contention within the literature is whether coercive control is a subtype of IPV or if it is the broader context within which IPV occurs.

Early conceptualisations of coercive control have emphasised the distinction between ongoing patterns of violence and situational violence. Of particular relevance here is the framework developed by Johnson (2008) outlining 4 distinct types of IPV violence use and the extent to which control is a motivating factor. In this framework, 'intimate terrorism' can be considered one of the early conceptual origins of coercive control. It is a relationship where one individual uses violence to control their partner. The type of control motivation here is not a situational one-off, goal-oriented violence. Rather:

the control sought in intimate terrorism is general and long term. Although each particular act of intimate violence may appear to have any number of short-term, specific goals, it is embedded in a larger pattern of power and control that permeates the relationship. (Johnson, 2008, p 13)

'Violent resistance' is when one individual uses violence in response to their partner's intimate terrorism. 'Mutual violent control' is a relationship type where both individuals use violence to control one another. Finally, 'situational couple violence' is where one or both individuals use violence but not to gain long-term and general control over the other. Except for situational couple violence, all the other 3 types of IPV relationships in Johnson's framework include coercive control enacted by at least one of the individuals within the relationship. Since the original conceptualisations by Johnson (2008) and Stark (2007) (described below), the conceptualisation of coercive control has continued to be refined as our understanding of this issue grows (Stark & Hester, 2019).

In this paper, we use the definition of coercive control applied by ANROWS.5 This ensures that this paper is consistent with and comparable to other work across Australia on coercive control. ANROWS' definition of coercive control is also consistent with that proposed by Stark (2007; described in the following paragraphs) who originally developed the concept of 'coercive control' and Johnson's (2008) conceptualisation of intimate terrorism.

ANROWS (2021) defines coercive control as behaviours or strategies (including physical and non-physical violence) used to control a victim-survivor and make them feel inferior to, and dependent on, the perpetrator enacting these behaviours or strategies. Coercive control involves ongoing and repetitive strategies that add up over time to impact the victim-survivor's independence, freedom and equality (ANROWS, 2021). The perpetrator's dominance and control over the victim-survivor has the potential to impact 'every aspect of her life, effectively removing her personhood' (ANROWS, 2021, p 1). ANROWS describe coercive control as the broader situation within which ongoing intimate partner violence (IPV) occurs (ANROWS, 2021).

Coercive control is the ongoing and repetitive use of behaviours or strategies (including physical and non-physical violence) to control a current or ex-intimate partner (i.e. victim-survivor) and make them feel inferior to, and dependent on, the perpetrator. (ANROWS, 2021)

Essential to this definition of coercive control are 2 components: (a) it includes physical and/or non-physical violence and (b) the physical and/or non-physical violence is ongoing. Viewing the victim-survivor's abuse as incident specific (i.e. in isolation from other incidences of violence or abuse perpetrated by the same person towards the victim-survivor) or viewing physical injury or physical trauma as a more serious form of abuse 'disaggregates, trivialises, normalises or renders invisible' the ongoing oppression they experience (Stark, 2009, p 1510).

ANROWS (2021) describes coercive control as a kind of power that (almost exclusively) male perpetrators use against (almost exclusively) female victim-survivors. This definition is in part supported by national Australian data suggesting that women have greater likelihood of experiencing family, domestic and sexual violence than men (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2018). However, not all organisations or researchers describe coercive control in this way; some examine coercive control victimisation among men as well as women. To account for this broader conceptualisation, this review did not exclude any studies based on participant gender or sexuality.

ANROWS highlight the following list of strategies perpetrators may use to enact coercive control (2022, p 1):

- physical, sexual, verbal and/or emotional abuse

- psychologically controlling acts

- deprivation of resources and other forms of financial abuse

- social isolation

- using systems to cause harm (e.g. the legal system)

- stalking and harassment

- deprivation of liberty

- intimidation.

The list above contains some possible strategies and behaviours used by perpetrators but it is not a comprehensive list. The perpetrator is likely to use any strategies they believe will be effective in controlling the specific victim-survivor. For example, there is emerging research indicating that perpetrators may threaten to or actually harm the family pet in order to control the victim-survivor's behaviour (Collins et al., 2018; Muri et al., 2022).

Consistent with the strategies outlined by ANROWS listed above, Australian qualitative studies have highlighted some of the common behaviours and strategies used by perpetrators of coercive control as reported by victim-survivors, including:

- monitoring or surveillance of the victim-survivor's location (Moulding et al., 2021)

- stalking the victim-survivor (Eriksson et al., 2022)

- becoming jealous of the victim-survivor spending time with other people (e.g. accusing them of having affairs) (Eriksson et al., 2022)

- restricting the victim-survivor's relationships and social support (Moulding et al., 2021)

- being emotionally, physically or sexually abusive (Eriksson et al., 2022; Pitman, 2017)

- thinking they are superior, entitled, dominant or have ownership over the victim-survivor (Eriksson et al., 2022; Pitman, 2017)

- controlling or criticising the victim-survivor's appearance or weight (Eriksson et al., 2022; Moulding et al., 2021)

- avoiding, obstructing or retaliating in response to the victim-survivor trying to negotiate or maintain boundaries within the relationship (e.g. refusing to communicate, threating to overdose on a substance, or using or threatening physical or sexual violence) (Pitman, 2017)

- establishing double standards in the relationship in terms of rights, reciprocity and accountability (Pitman, 2017)

- placing contradictory expectations on the victim-survivor (e.g. demanding the victim-survivor focus on them and adapt to their needs but not be dependent on them) (Pitman, 2017).

4 At the time of writing, Tasmania is currently the only Australian jurisdiction to have criminalised coercive control (Safe from Violence, n.d.). Although in 2022-23, legislative amendments have passed in the New South Wales (Parliament of New South Wales, 2022) and Queensland state governments (Queensland Government, 2023) and consultations have begun in South Australia.

5 ANROWS is an independent, not-for-profit national body for research on domestic and family violence in Australia (ANROWS, 2021).

Why it is important to understand coercive control victimisation

This chapter outlines some of the key reasons why it is important to have a greater understanding of common coercive control victimisation and what risk factors and impacts are associated with coercive control victimisation.6 In particular, this chapter highlights some of the reported consequences for victim-survivors of:

- a lack of understanding in police and legal responses to coercive control

- community misconceptions of coercive control.

Police and legal responses to coercive control

A lack of understanding of coercive control within the legal system can lead to poor or unjust outcomes for victim-survivors (Boxall et al., 2020; Nancarrow et al., 2020; Ulbrick & Jago, 2018) and impairs the level of protection provided to victim-survivors. Although police are not DFV specialists, they are important frontline workers who can potentially identify patterns of coercive control in callouts related to DFV (Myhill & Hohl, 2019). A study of police reports of domestic violence cases in the United Kingdom found that the reports often referenced coercive control behaviours (Myhill & Hohl, 2019), such as the victim-survivor feeling isolated or frightened and the perpetrator controlling the victim-survivor and being excessively jealous.

If these signs of coercive control are missed or not understood by police, this may result in police viewing the violence on an incident-by-incident basis, as opposed to an ongoing pattern of abuse. This can result in missed opportunities to provide victim-survivors with appropriate referrals and support. It can also mean that: (a) perpetrators are not held accountable for ongoing violent patterns of behaviour, and (b) the cumulative impact on victim-survivors is not adequately acknowledged (Stark & Hester, 2019).

If police view violence on an incident-by-incident basis, this is particularly problematic when victim-survivors use violence to defend themselves from a violent partner (described earlier as violent resistance) and are misidentified as a sole or co-perpetrator (Boxall et al., 2020; Nancarrow et al., 2020; Ulbrick & Jago, 2018). In this kind of situation:

- It may be difficult for police and the broader legal system to identify the person in the relationship most in need of legal protection (Nancarrow et al., 2020).

- Victim-survivors may be unjustly criminalised (Nancarrow et al., 2020).

Victim-survivors can also be harmed by perpetrators using the legal system to enact coercive control. Douglas (2018) interviewed 65 Australian women engaged with the legal system because of intimate partner violence. The women described strategies used by their violent partners to continue controlling and having access to the victim-survivor after separation through legal processes, such as requesting numerous last-minute adjournments of court cases and extending mediation time.

Community misconceptions of coercive control

Challenging community-level misconceptions and increasing awareness of coercive control are important to preventing and responding to coercive control. A nationally representative study of 17,500 Australians aged 16+ years found that approximately 1 in 3 Australians believe that women who do not leave an abusive relationship are partially responsible for the violence they experience (Webster et al., 2018). About 1 in 6 Australians do not believe it is difficult for a woman to leave an abusive relationship (Webster et al., 2018).7

These misconceptions do not take into consideration the complexity of coercive control victimisation and place the responsibility of the violence on the victim-survivor rather than the perpetrator. In reality, the periods of time without active violence required to plan how to leave safely or take action on such a plan may not exist (ANROWS, 2021). Perpetrators use a wide variety of strategies to foster a sense of entrapment, erode victim-survivors sense of autonomy and make it very challenging (if not impossible) for victim-survivors to safely leave (ANROWS, 2021). Additionally, research indicates that trying to end a relationship with a violent partner can escalate the violence, including increased risk of intimate partner homicide, as the violent partner attempts to maintain control (Monckton Smith, 2020).

Greater community-level understanding of coercive control could enhance the ability of victim-survivors to seek support (Webster et al., 2018).

6 It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the evidence on coercive control perpetration. However, we acknowledge that this is a crucial area of research that requires further investigation. As the evidence base on coercive control perpetration develops, broader literature and interventions focused on the perpetration of family, domestic and sexual violence provides insights likely to be transferrable to practice with perpetrators of coercive control. Please see the Further reading and related resources section for links to 2 useful resources in this area.

7 Although a more recent version of this nationally representative study is available (Coumarelos et al., 2023), the study did not ask these questions and so we have reported the earlier data.

The nature of the evidence base

The following 3 chapters of this paper provide a synthesis of research findings about how common coercive control victimisation is, as well as associated risk factors and impacts. The literature synthesised in the following chapters is different to that described in the previous chapter, which served to provide context for the chapters to follow. The 13 research studies included in the following synthesis chapters were identified through a rapid review of the coercive control victimisation literature. The rapid review method is described later in the chapter, see Method: How the rapid literature review was conducted. This chapter explains the nature of the literature on how common coercive control victimisation is, and the risk factors and impacts, as identified through the rapid review method (described below as 'the sample').

Characteristics of studies sampled in the review

Of the 13 studies included in the sample, 7 studies (54%) were published during or after 2017. Roughly half of the studies were from Canada (n = 6, 46%). Four studies (31%) were from the United Kingdom. Only 3 studies (23%) were conducted in Australia.8 Appendix A contains a table listing the individual studies and highlighting relevant characteristics of each. This section provides an overview of those relevant characteristics.

Most studies (11, 85%) used the cross-sectional survey method for data collection (data collected at one point in time) and one study had a longitudinal survey methodology (using data gathered over several years). All but one study analysed self-reported data from victim-survivors, with the exception analysing data from police created reports about family and domestic violence incidents where stalking had occurred.

The studies had sample sizes ranging from 40 to 42,000 participants. Eight studies (62%) had samples of over 1,000 participants. Most studies described participants in terms of their gender, parental or marital/cohabitation status and/or service access. Participants were predominantly adult women, with 2 studies also including underage men and women (15+ and 16+ years old) (Myhill, 2015; Pedersen et al., 2013). Only around one-third of the studies (4, 31%) included male participants in addition to women (Frankland & Brown, 2014; Mayshak et al., 2020; Myhill, 2015). In 2 studies, the sample was exclusively mothers (Broughton & Ford-Gilboe, 2017; Skafida et al., 2022). Additionally, 2 studies only included women who were married or cohabitating (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015; Pedersen et al., 2013), and one included only women who had separated from an abusive partner (Broughton & Ford-Gilboe, 2017). Only one study specifically explored the experiences of same-sex attracted adults (Frankland & Brown, 2014). Regarding service access, 2 studies involved current or previous residents of women's or homeless shelters (Ellis et al., 2021; Levine & Fritz, 2016), and one study had recruited clients of domestic violence services (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018).

Bendlin and Sheridan (2019) was the only study to analyse police reports. All other studies analysed self-report data from victim-survivors. Bendlin and Sheridan (2019) analysed a dataset of DFV reports completed by police in Perth, Australia, between 2013 and 2017 (n = 9,884 reports). The researchers included only those reports where there had been stalking. The authors of this study did not report participant characteristics beyond 'reports of domestic violence'.

Most studies (70%) adopted customised measurements of coercive control victimisation (i.e. measures constructed by the authors for the purpose of the study). Standardised measures were used by only 4 studies. These included the Women's Experiences of Battering (WEB; Broughton & Ford-Gilboe, 2017; Ford-Gilboe et al., 2016), the Revised Controlling Behaviours Scale (CBS-R; Levine & Fritz, 2016) and the Coercive Control UK Scale (CCUK; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018).

The quality of evidence on coercive control victimisation

Research on coercive control victimisation is still at a relatively early stage of development and this limits what can be said about its frequency or impact, especially in Australia. This section of the paper outlines some considerations relating to the nature and quality of the research to date on coercive control victimisation. This section covers: (a) issues with study populations, (b) the way coercive control victimisation is defined and measured, and (c) research design.

Participants in the sampled studies

There is at present little research specific to the Australian context. Only a small proportion of the studies explored for this paper considered Australian experiences (3 out of 13 studies, 23%). There is a need for foundational knowledge about frequency, risk factors and impacts of coercive control victimisation for various subpopulations in Australia. We currently know little about the unique experiences of:

- Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples

- people with disability

- LGBTQIA+ communities

- culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities

- people in older age groups (65+ years)

- children and young people where there is coercive control between their parents

- intersectional experiences across more than one of the above.

To date, data have typically been collected from either clinical samples, where individuals are targeted for recruitment because they have experienced IPV, or from the general population. There are strengths and weaknesses associated with both kinds of studies.

Findings from clinical samples are useful because they can tell us about coercive control victimisation among those who experience an increased risk, such as individuals experiencing IPV. This can aid our understanding of different forms of abuse. However, we can expect some of the findings among this group to differ from that of the general population. For example, the prevalence rate of coercive control victimisation is likely to be higher in clinical samples than in the general population.

Myhill (2015, p 360) notes that clinical samples 'have been useful in exploring the dynamics of abuse and prompting the development of typologies to differentiate between different forms of abuse,' but to establish population-level estimates of coercive control we need to use representative national samples (Myhill, 2015). Additionally, sample sizes in clinical sample studies tend to be small, making it difficult to know how generalisable the findings are to other people accessing support services as a result of IPV (the clinical population). Because the clinical samples tend to be convenience or snowball samples, it is also difficult to know whether there is systematic bias whereby certain service users were less likely to choose or have the opportunity to participate in the studies.

Conversely, general population studies can provide insights into how widespread coercive control is. The general population studies covered in this review did recruit larger numbers of participants but often provided little information about the representativeness of the sample or how participants were selected. Only 4 of the 13 studies provided information about participant response rates (Ellis et al., 2021; Kaukinen & Powers, 2015; Myhill, 2015; Skafida et al., 2022). Response rates are important because they indicate what proportion of people who were given the chance to participate decided not to. Response rate information for the sampled studies can be found in Appendix A.

Victim-survivors of IPV may be under-represented in general population samples for a range of reasons including lack of independence from the perpetrator and social isolation (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015). Participants in general population studies may also be less likely than those in clinical samples to disclose violence (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015). For these reasons, the reported prevalence rates may underrepresent the actual prevalence of coercive control within the broader community (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015).

Defining and measuring coercive control

Summarising the research evidence on coercive control victimisation is also hampered by the debate among researchers and experts on what exactly coercive control victimisation is. A literature review by Hamberger and colleagues (2017) demonstrated this point well when it identified 22 different measures and definitions of coercive control victimisation but none that had been frequently used. This lack of consistency was also evident in the studies sampled in the present review:

- Some emphasised the gendered nature of coercive control by only sampling women victim-survivors who had been in IPV relationships with men, whereas others sampled men and women in opposite- and same-sex relationships.

- Some used archive data from many years earlier that focused on broader conceptualisations of IPV or DFV and selected items to best fit the existing data to a study exploring coercive control. In these cases, coercive control victimisation tended to be conceptualised as the experience of psychological or emotional abuse behaviours in broader scales of DFV (i.e. not physical or sexual abuse). However, in contrast, the foundational work by Stark and colleagues (Stark, 2007; Stark & Hester, 2019) and later by ANROWS (2021) conceptualises coercive control as the context in which IPV occurs, meaning that physical and sexual violence are considered behaviours that can be used to enact coercive control (when not occurring in isolated incidence based abuse).

- Most studies (70%) used customised measurements of coercive control victimisation (i.e. measures constructed by the authors for the purpose of the study). Standardised and psychometrically validated measures were used by only 4 of the 13 sampled studies.

The significant differences between definitions and study populations means that findings across studies are not easily comparable. Among other consequences, this means it is uncertain which risk factors and impacts are most robust and deserving of further investigation. The lack of consistent definitions may also make it more challenging to develop practice responses.

Research design

The studies sampled in this review provide important foundational insights about coercive control victimisation. This section highlights some limitations with the research designs adopted in the studies. It is important to note that all research studies have limitations and many of these are the result of the practical barriers that come with studying a complex area of human experience.

Most of the reviewed studies used a type of data collection method called a cross-sectional survey. In these studies, participants were asked about their experiences and attitudes at a single point in time, with the analysis inferring the relationship between groups of variables. For example, higher levels of coercive control victimisation can be associated with specific outcome variables such as higher levels of negative mental health symptoms. Cross-sectional research cannot establish the direction of this relationship - that is, whether coercive control causes mental health problems or whether mental health problems create a susceptibility to coercive control - or demonstrate change over time. Longitudinal methods are required for those insights.

Some other areas for consideration include:

- the large differences in sample sizes, ranging from 40 to 42,000 participants

- the absence of demographic and other relevant social variables in analyses that might assist in greater understanding of how findings may differ between various subpopulations

- a broad range of risk factors and impact measures across the various studies with little consistency of measures or replication of findings

- a tendency to focus on individual-level factors associated with victimisation, without equal consideration of broader institutional or societal factors (such as gendered drivers of inequality that reinforce violence against women).9

8 Studies from the United States were excluded because the findings are not as readily comparable to the Australian context as those of the other international studies included. More information about this is provided in the Screen for country of origin in the method chapter.

9 Community and structural gendered drivers of inequality that reinforce violence against women include: (a) attitudes and behaviours that condone violence against women, (b) men having greater decision-making abilities in public and private institutions, (c) gender stereotyping and (d) dominant forms of masculinity that emphasise aggression, dominance and control (Coumarelos et al., 2023).

How common is coercive control victimisation?

The main insights about the frequency of coercive control victimisation and implications for practice, research and policy are set out in the key messages box. The rest of the chapter provides more detail on the findings of studies assessing frequency.

Frequency: key messages

- Differences in definitions of coercive control and research design (including participant sampling methods) mean there is a wide range of frequency figures reported across studies (between 2.7% and 100% across clinical and general population samples). It is not possible to assess from the available literature what the true prevalence of coercive control is in the Australian general population.

- In studies examining general population samples, 7.5%-28% of participants may have experienced coercive control victimisation.

- Some studies only examined groups of women who may already be at increased risk of coercive control, such as those who've accessed domestic violence services, accessed women's shelters, engaged in custody disputes with ex-partners or separated from an abusive partner. These studies found that the frequency rates of coercive control victimisation among these women ranged between 4.4%-100%.

- The frequency of coercive control victimisation in the single study assessing same-sex relationships in Australia reported a similar frequency figure (24%) to that of the general population samples (28%).

- The available evidence suggests that the frequency of coercive control victimisation may be higher in Australian samples than in other countries. However, this may be because coercive control is better understood and reported in Australia compared to elsewhere. Additionally, coercive control victimisation research is still emerging, with few studies conducted in Australia. Across international studies there are also limitations and challenges relating to the measurement of coercive control, making it difficult to compare findings across studies and countries.

Frequency: potential implications

Practice

- Victim-survivors of coercive control may access non-specialist services to get support for a range of wellbeing purposes but not necessarily disclose their experiences of coercive control. Currently, it is difficult to know what the prevalence of coercive control is across the general population. For these reasons, practitioners in non-specialist services should consider: (a) how they can adapt their practice to provide a safe space for disclosure, (b) how they might personally respond to disclosures, and (c) which specialist services they can refer victim-survivors to.

- Specialist practitioners working with individuals experiencing IPV should be aware that the proportion of clients that have experienced coercive control victimisation varies considerably but could be as high at 100%. The clinical samples studied to date include women who have accessed domestic violence services, accessed women's shelters, engaged in custody disputes with ex-partners or separated from an abusive partner. There is a need to provide individualised care that considers a potential history of coercive control.

Research gaps

- The use of representative national samples could assist in establishing population-level estimates. This would involve matching the research sample to the broader population on various demographic factors (e.g. state of residence, age and gender).

- Including demographic and other relevant social variables in analyses may assist in greater understanding of how prevalence and risk factors differ between various subpopulations. Risk factors are discussed further in the next chapter.

- There is a need to build on existing research findings by using validated measurement tools and making efforts to minimise the effect of the research limitations identified within this paper.

Policy

- There may be a need to assess policy and service provision given that we currently do not have a clear picture of the actual prevalence of Australians who have experienced coercive control victimisation.

What the research tells us about the frequency of coercive control victimisation

This section summarises the frequency rates of coercive control victimisation reported across studies. The focus of this paper is on the experiences of victim-survivors, not on the frequency of perpetration behaviours. However, the limitations described in The nature of the evidence base chapter makes it challenging to accurately estimate the prevalence of coercive control victimisation.

The frequency findings for clinical and general population samples covered in this review are summarised separately because the findings are not directly comparable, and each comes with its own strengths and weaknesses. As noted above, the ways in which coercive control is conceptualised and measured in different studies affect reported frequency rates. Because of these challenges in measuring coercive control victimisation, the frequency figures discussed in the following discussion are best interpreted as a rough estimate of the possible range of frequency within clinical and general population samples.

Frequency in general population samples

Findings about coercive control victimisation from general population studies are mixed and not based on representative samples. This makes them difficult to interpret. The reviewed studies reported frequency rates between 7.5% and 28% in samples taken from the general population in the countries where studies were undertaken. The frequency rates for studies looking at international women and mothers ranged from 7.5% to 15% (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015; Nevala, 2017; Skafida et al., 2022). US data were excluded from the sample of this review but Kaukinen and Powers (2015) reported 17% frequency rate in a US general population sample of married or cohabiting women.

In 1 of the 2 Australian studies, Mayshak and colleagues (2020) conducted an online survey of 1,009 Australian adults aged 18-79 years, including male and female participants. Of the 989 participants who responded to the coercive control questions in the survey, 28% (n = 276) of all participants (male and female combined) had experienced coercive control victimisation over the past 12 months from a current or most recent partner.

Frankland and Brown (2014) sampled same-sex attracted adults (n = 184), presenting them with 15 different types of controlling behaviours and asking how many of these behaviours they engaged in (M = 2.7, SD = 3.2) and how many their partner engaged in (M = 3.3, SD = 3.7).10 The most frequently reported behaviours related to dominance and emotional control. The sample was then separated in to low and high levels of coercive control. The frequency of high control was approximately 24% in participants who self-reported about their own behaviours and those of their partner.

It is noteworthy that these 2 Australian studies have similar frequency rates, both of which appear elevated compared to the international studies summarised above. However, the small number of studies conducted in Australia, and limitations related to measurement and sampling, make it difficult to assess the true prevalence of coercive control victimisation in the Australian general population. For example, another Australian study reporting women's prevalence of coercive control victimisation was identified in the grey literature. That study reported a much lower 11% prevalence (Boxall & Morgan, 2021a), which is more aligned with the international studies reviewed.

Frankland and Brown's (2014) study was the only one to assess the frequency of Johnson's 4 types of IPV violence (intimate terrorism, violent resistance, mutual violent control and situational couple violence). Frankland and Brown (2014) also identified a fifth type of violence to identify relationships where control is present but physical violence is not: non-violent control. Participants provided information about their own behaviours and that of their partner. This information was then used to group the couples into 1 of these 5 categories or into a no violence and no control group. More than half of the sample was categorised as being in a no violence and no control group relationship (58.2%). The most common type of IPV relationship was situational couple violence (participants 13.0%, partners 14.7%), followed by mutual violent control (12.5% for both). Non-violent control (participants 7.1%, partners 5.4%) and intimate terrorism (participants 4.3%, partners 6.5%) were similar in frequency. Least common was violent resistance (2.7% for both).

Frequency in clinical samples

Four of the six clinical sample studies used a cross-sectional survey design (Broughton & Ford-Gilboe, 2017; Levine & Fritz, 2016; Myhill, 2015) and one used a longitudinal design (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Participants were women who had accessed domestic violence services, accessed women's shelters, engaged in custody disputes with ex-partners or separated from an abusive partner. The sample sizes ranged from 40 to 2,335 and each study measured coercive control victimisation differently.

Frequency rates of coercive control victimisation among women in clinical samples ranged between 4.4% and 100% (Broughton & Ford-Gilboe, 2017; Ellis et al., 2021; Myhill, 2015; Pedersen et al., 2013; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Myhill (2015) also provided a frequency rate of 6% for men.11 In the sixth study, Bendlin and Sheridan (2019) analysed a dataset of family violence reports completed by police in Perth, Australia (n = 9,884). The authors reported a frequency rate of 43.5% (n = 4,304) in family violence police reports that included stalking.12

10 See glossary for definition of mean (M) and standard deviation (SD).

11 Although coercive control is sometimes defined as a type of power almost exclusively used by men (ANROWS, 2021), because there are varied definitions used in the literature, this review did not exclude any studies based on the gender or sexuality of participants.

12 Bendlin and Sheridan (2019) used family violence police reports from 2013 to 2017 (n = 9,884). The researchers included only those reports where stalking occurred because research literature cited by the authors had identified stalking to be a common component of coercive control perpetration. For this reason, it would be expected that this study would report an elevated coercive control prevalence. Cases were categorised as involving coercive control if the responding officer recorded their belief that the perpetrator was coercively controlling the victim-survivor.

Risk factors associated with coercive control victimisation

The main risk factors for coercive control victimisation and implications for practice, research and policy are set out in the key messages box. The rest of the chapter provides more detail on the findings of studies assessing risk factors.

Risk factors: key messages

- The evidence about risk factors for coercive control victimisation is inconclusive. A broad number of risk factors have been identified but they vary between studies. Where risk factors have been assessed across more than one study, the findings about their significance have been inconsistent.

- The mixed findings on risk factors may be a result of researchers using different: (a) definitions of coercive control victimisation, (b) measures of coercive control victimisation, and (c) participant sampling methods (e.g. non-representative methods such as convenience sampling).

- Confidence in findings is required to establish which risk factors warrant greater attention from a practice and policy perspective. Confidence can be increased through: (a) replication across multiple studies, and (b) the use of statistical methods comparing multiple risk factors relative to one another.

- Practitioners, researchers and policy makers may want to explore assessing risk factors already established for IPV and, to a lesser extent DFV, due to the close relationship between experiences of coercive control victimisation and IPV and DFV.

Risk factors: potential implications

Practice

- Research literature cannot currently provide practitioners with a good understanding of which characteristics or experiences indicate or cause elevated risk for experiencing coercive control victimisation. This means that practitioners need to keep an open mind when working with clients because anyone could be experiencing coercive control victimisation.

- Although the findings in this review on coercive control do not provide sufficient evidence to assess whether gender is a factor in elevated risk for experiencing coercive control victimisation, national Australian data does suggest that women have a greater likelihood of experiencing family, domestic and sexual violence than do men (AIHW, 2018).

Research

- Research has tentatively identified a wide range of potential individual-level risk factors. Replication of findings is required to determine whether these are meaningful areas to target for practice and policy changes.

- There is a need for research specific to Australia and including Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, people with disability, LGBTQIA+ communities, CALD communities, and people in older age groups (65+ years).

- Future research may need to focus on the development, validation and consistent application of measures to explore risk factors. This would allow for comparisons across studies and build knowledge over time and across population groups.

- Future research should focus on testing associations reported in previous studies to: (a) strengthen the evidence about which risk factors are significant, and (b) facilitate development of targeted and effective supports.

- Future research should adopt a longitudinal design to provide information over time about the possible causal links between various risk factors and coercive control victimisation.

Policy

- Evidence on risk factors is inconclusive. It is not clear how resources may be best directed to support individuals at elevated risk of experiencing coercive control victimisation. While more conclusive insights are being formed, it may be beneficial to: (a) focus on awareness raising within the Australia community, (b) provide training for generalist practitioners to identify warning signs of clients potentially experiencing coercive control victimisation, and (c) strengthen referral pathways from generalist support services to specialist IPV services.

- Child and family services need support to build capabilities and resources for consistent data collection.

What the research tells us about risk factors associated with coercive control victimisation

The studies reviewed for this paper identified numerous risk factors for, or characteristics associated with, coercive control victimisation. These varied considerably between studies. We have listed all statistically significant (highlighted in blue) and non-significant findings (highlighted in pink) in the reviewed studies in Table 1. The common cut off for determining statistical significance in the reviewed studies was a p value of <0.05; that is, where there was less than 5% chance that a finding of difference between compared groups, or a relationship between coercive control victimisation and a specific risk factor, was the result of chance. We have included non-significant findings in this table because reporting only significant findings makes it difficult for those working in this area to know the full range of variables that previous research has focused on or the extent to which there is inconsistency in findings.

Five of the factors included in Table 1 are theoretical risk factors for perpetration, not victimisation: psychopathy, Machiavellianism, grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism and sadism.13 The study that included these factors reported scores for both perpetrators and victim-survivors (Mayshak et al., 2020). Because the research base on coercive control victimisation is currently small, we decided to include findings about these theoretical perpetration risk factors and likelihood of victimisation to present a more complete picture of existing research evidence.

| Risk factor | Description of findings | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Frequency of coercive control experiences is significantly higher for women than it is for men. | (Myhill, 2015) |

| Levels of coercive control experiences are not significantly different between men and women. | (Mayshak et al., 2020) | |

| Age | Age is not significantly associated with coercive control experiences (One study sampled women, the other sampled women and men). | (Mayshak et al., 2020; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Ethnicity | Aboriginal women experience significantly higher rates of coercive control and stalking experiences than non-Aboriginal women. | (Pedersen et al., 2013) |

| Mothers that identify as 'white' are significantly more likely to experience coercive control than those who identify as 'other ethnicity'. | (Skafida et al., 2022) | |

| Women's coercive control experiences are not significantly different between ethnicity groups (White, Black, Asian, and other). | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) | |

| Education | Mothers with higher levels of education are significantly more likely to experience coercive control than mothers with lower levels of education. | (Skafida et al., 2022) |

| Women's coercive control experiences are not significantly different between education level groups (no high school, high school, and college). | (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015) | |

| Employment status | Unemployed women are significantly more likely to experience coercive control than employed women. | (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015) |

| Income | Mothers who have lower household income are significantly more likely to experience coercive control than those with higher household income. | (Skafida et al., 2022) |

| Women experiencing poverty are not significantly more likely than high income earning women to experience coercive control (<$5,000 Canadian Dollars per year compared to >$40,000). | (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015) | |

| Psychopathy | Adults with higher levels of psychopathy experience significantly greater levels of coercive control victimisation | (Mayshak et al., 2020) |

| Machiavellianism | Levels of coercive control experiences were not significantly associated with levels of Machiavellianism. | (Mayshak et al., 2020) |

| Grandiose narcissism | Levels of coercive control experiences were not significantly associated with levels of grandiose narcissism. | (Mayshak et al., 2020) |

| Vulnerable narcissism | Levels of coercive control experiences were not significantly associated with levels of vulnerable narcissism. | (Mayshak et al., 2020) |

| Sadism | Levels of coercive control experiences were not significantly associated with levels of sadism. | (Mayshak et al., 2020) |

| Victim-survivor experiencing maltreatment as a child | Women who reported higher levels of childhood maltreatment experienced significantly higher levels of coercive control. | (Levine & Fritz, 2016) |

| Victim-survivor being a mother | Women who have children are not significantly more likely than those who do not have children to experience coercive control. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Victim-survivor age when their first child was born | First-time mothers <30 years old are significantly more likely to experience coercive control than those aged 40+ years. | (Skafida et al., 2022) |

| Number of children a victim-survivor has | Mothers with 2 children are significantly more likely to experience coercive control than mothers who have one child. | (Skafida et al., 2022) |

| Gender of victim-survivor's children | Mothers of male children are significantly more likely to experience coercive control than mothers of female children. | (Skafida et al., 2022) |

| Means of meeting partners | Adults who use face-to-face and/or website dating methods experience higher levels of coercive control than those who use dating applications. | (Mayshak et al., 2020) |

| Perpetrator's substance use | Women with greater concern about their ex-partner's substance use experience significantly higher levels of coercive control from that ex-partner. | (Ellis et al., 2021) |

| Perpetrator's mental health | Women with greater concern about their ex-partner's mental health experience significantly higher levels of coercive control from that ex-partner. | (Ellis et al., 2021) |

| Citizenship status of victim-survivor | Women's coercive control experiences are not significantly different between citizenship status groups (citizen, permanent resident, and others including asylum seekers and refugees). | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Social class | Mothers in lower social classes are significantly more likely than mothers in higher social classes to experience coercive control. | (Skafida et al., 2022) |

| Perceived gender equality | Countries with lower levels of perceived gender equality have significantly higher prevalence of coercive control. | (Nevala, 2017) |

Note: blue = statistically significant, pink = not statistically significant.

The evidence about risk factors for coercive control victimisation is inconclusive. Although several risk factors for coercive control victimisation have been identified, most of these were only reported in one study. Where risk factors were assessed in more than one study, the findings about their significance were inconsistent. The risk factors with inconsistent findings across studies were:

- being female, compared to male (Mayshak et al., 2020; Myhill, 2015).

- As described earlier, ANROWS and Stark (Stark, 2007) conceptualise coercive control as being something that, almost exclusively, male perpetrators enact on female victim-survivors. In this context, it is notable that the study of Australian adults aged 18+ years did not find a significant difference between men's and women's levels of coercive control victimisation (Mayshak et al., 2020).

- In contrast, Myhill (2015) found that, among people who had experienced an abusive relationship, a greater proportion of women compared to men had experienced coercive control. This was a significant difference between men and women. The inconsistency in these findings may in part relate to the samples each study examined. Mayshak and colleagues (2020) examined a general population sample, whereas Myhill (2015) examined a clinical sample of those who have been in an abusive relationship and, therefore, may have been more likely to experience coercive control than the general population.

- having higher levels of educational training (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015; Skafida et al., 2022).

- having lower household income (Kaukinen & Powers, 2015; Skafida et al., 2022).

Because the significant findings have not yet been adequately replicated in multiple studies, it is difficult to draw conclusions from the current evidence.

Psychopathy has also been found to be a risk factor associated with coercive control victimisation but not perpetration (Mayshak et al., 2020). Theoretically, the opposite should be true because psychopathy is a socially aversive personality trait characterised by a lack of remorse, thrill-seeking tendencies, manipulation, lying, impulsivity and behaviour generally motivated by callousness (Miller et al., 2010; Paulhus, 2014). It could be that this finding is the result of methodological challenges in distinguishing between mutually violent relationships and other kinds of IPV. Further research is required to understand the positive association between psychopathy and coercive control victimisation.

Three studies considered ethnicity as a possible risk factor but each measured ethnicity in different ways and the findings across these studies were inconsistent with each other. One study found no significant difference in coercive control victimisation between 4 ethnicity categories (white, Black, Asian and other). One reported that identifying as 'white' is a risk factor compared to those identifying as 'other ethnicity'. One reported identifying as an Aboriginal woman is a risk factor (in comparison to identifying as a non-Aboriginal women).

Age was not found to be a risk factor for experiences of coercive control victimisation in either of the 2 studies that considered this risk factor (Mayshak et al., 2020; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Both studies used age as a continuous variable to see whether being younger or older was significantly associated with higher or lower levels of coercive control experiences. These are useful foundation findings, requiring replication in representative samples to increase our confidence that there is not a relationship between age and victimisation in this way.

A future direction for exploring age as a risk factor is to compare age groups. It may be that specific age groups experience coercive control victimisation differently, either qualitatively or quantitatively (e.g. people aged 65+ years). These group-based differences are not apparent when examining age as a continuous variable. If age group differences exist, this is important to know so that tailored prevention and intervention strategies can be developed. Refer to Appendix B for discussion on future research directions on age as a risk factor for coercive control victimisation.

Because most of the studies we reviewed used a cross-sectional design, the findings are not able to identify risk factors that caused coercive control victimisation. The research findings can only indicate that the risk factor is associated with coercive control victimisation. This is important evidence for building understanding of coercive control victimisation but there may be other, unidentified factors influencing the relationships between risk factors and coercive control victimisation than are reported here. There is a need for longitudinal research that follows people over time to understand more about the nature of the relationships between coercive control victimisation and the risk factors identified in this review to assess how robust the associations are. This kind of information could help inform prevention and early intervention strategies to support specific subpopulations at risk of or experiencing coercive control victimisation.

13 See glossary for definitions of psychopathy, Machiavellianism, grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism and sadism.

Impacts associated with coercive control victimisation

The main impacts of coercive control victimisation and implications for practice, research and policy are set out in the following box. The rest of the chapter provides more detail on the findings of studies assessing prevalence.

Impacts: key messages

- None of the sampled studies examined the impacts of coercive control victimisation in Australia.

- Research on the impacts of coercive control victimisation has been conducted predominantly in Canada and the United Kingdom.

- Mental health outcomes are the most frequently researched impact factors among women but the quality of the evidence varies. Unsurprisingly, studies generally found that coercive control victimisation decreased women's mental health and wellbeing.

- Other studied impacts included decision-making abilities, family health and wellbeing, physical injury levels, emotional injury levels and time taken off paid work.

- The studies provide useful foundational information. Efforts to improve research are required to better understand coercive control victimisation and its effects. There also needs to be effective translation of research into meaningful supports or actions for victim-survivors.

- Some key gaps in evidence include:

- the impacts of coercive control victimisation on children of victim-survivors

- non-mental health related impacts of coercive control victimisation

- the impacts of coercive control victimisation specific to the Australian population

- more rigorous analysis of the impact of coercive control victimisation over time.

Impacts: potential implications

Practice

- Women who are experiencing, or have experienced, coercive control victimisation are likely experiencing mental health issues, such as elevated symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression.

- Practitioners working with victim-survivors need to be prepared to discuss mental health and provide referrals to mental health services if required.

- Mental health workers are important frontline workers who may be able to identify and support victim-survivors who access support for their psychological distress but do not disclose their abuse.

- We do not yet fully understand how coercive control impacts victim-survivors. The impact likely differs between people, with each victim-survivor requiring support specific to their needs.

Research

Research gaps and considerations for future research studies:

- whether longitudinal population-based cohort or data linkage studies methods are feasible and appropriate

- how to extend beyond measuring mental health impacts of coercive control victimisation

- how the impacts of coercive control victimisation change over time

- who the most appropriate comparison or control groups might be for studies of the impact of coercive control. Some studies have compared the findings for individuals experiencing coercive control victimisation to those categorised as experiencing IPV but, as we noted earlier, these are not necessarily mutually exclusive groups. It may be more meaningful to compare coercive control victim-survivors to a comparison group that has not experienced IPV or that has experienced only situational violence.

- how to sample a diverse range of women and assess their unique experiences

- how to build on existing research and knowledge when planning and designing studies

- how to assess the impacts of coercive control victimisation effects for families and the broader community, not just the individual

- whether it is possible and appropriate to use existing research definitions, measures and subcategories to assess the impact of coercive control victimisation. The greater the differences in these areas between studies, the more challenging it is to compare findings and make recommendations on the most trustworthy findings to pursue with respect to practice and policy initiatives.

- how coercive control impacts the health and wellbeing of children of the victim-survivor and perpetrator

- the experiences of coercive control for people aged 65+.

Policy

There is a need for:

- integration between mental health assessment and treatment services and DFV and IPV systems and services

- increased funding opportunities for high-quality quantitative research on coercive control victimisation in Australia.

What the research tells us about the impacts of coercive control victimisation

The reviewed studies identified several potential impacts associated with coercive control victimisation, of which several related to mental health. All significant and non-significant findings from the reviewed studies have been summarised in Table 2. Statistically significant findings have been highlighted in blue and non-significant findings have been highlighted in pink.

Direct comparison across studies is challenging because different populations and impacts have been examined. Most of the reviewed studies used cross-sectional study designs (Broughton & Ford-Gilboe, 2017; Ellis et al., 2021; Ford-Gilboe et al., 2016; Levine & Fritz, 2016; Myhill, 2015). As mentioned previously, in this type of study variables are measured at a single point in time. This means we cannot be sure whether a variable (e.g. mental health challenges) is a consequence of coercive control victimisation or a characteristic of people at risk of coercive control victimisation (Setia, 2016).

| Impact variable | Description of findings | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health treatment | Women who experience elevated levels of coercive control are significantly more likely to access mental health treatment because of the abuse they have experienced. | (Ellis et al., 2021) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Women who experience elevated levels of coercive control are significantly more likely to experience elevated levels of PTSD symptoms. | (Levine & Fritz, 2016) |

| Depressive symptoms | Women's coercive control experiences are not significantly associated with depressive symptoms. | (Levine & Fritz, 2016) |

| Freedom in psychological decision making | Women who experience elevated levels of coercive control experience significantly reduced levels of confidence, sense of safety and satisfaction with their lives. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Freedom in economic decision making | Women who experience elevated levels of coercive control experience significantly lower levels of security and comfort with their finances and their physical home. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Freedom in physical decision making | Women who experience elevated levels of coercive control experience significantly lower levels of satisfaction and decision making about their own appearance and their overall wellbeing. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Freedom in support and relationships decision making | Women who experience elevated levels of coercive control experience significantly lower levels of satisfaction and decision making about having friends, accessing support and having intimate relationships. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Freedom in wider community connection decision making | Women who experience elevated levels of coercive control experience significantly lower levels of connection with their community. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Freedom in parenting decision making | Women's coercive control experiences are not significantly associated with attitudes towards being a mother. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) |

| Freedom in efficacy decision making | Women's coercive control experiences are not significantly associated with their ability to 'deal with authorities and services, cope with child care and household responsibilities, and manage a budget'. | (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018, p. 175) |

| Physical health | Victim-survivors of coercive control are significantly more likely to experience physical injuries than victim-survivors of situational violence. | (Myhill, 2015) |

| Emotional wellbeing | Victim-survivors of coercive control are significantly more likely to experience emotional injuries (e.g. difficulty sleeping, nightmares, depression or low self-esteem) than victim-survivors of situational violence in relationships. | (Myhill, 2015) |

| Absence from work | Victim-survivors of coercive control are significantly more likely than victim-survivors of situational violence to take time off paid work due to the abuse they had experienced in the previous 12 months. | (Myhill, 2015) |

Note: blue = statistically significant, pink = not statistically significant.

None of the reviewed studies addressing the impact of coercive control victimisation were conducted in Australia. This potentially limits the applicability of these findings to Australia. However, the countries in which studies were undertaken are relatively similar to Australia14 and so the impacts of coercive control victimisation are likely to be comparable.

This review identified that mental health is the most frequently researched, and so the most well-established statistically significant, impact domain of coercive control victimisation.15 The more coercive control experiences that participants reported, the more likely they were to also report elevated PTSD symptoms and to be accessing mental health treatment (Levine & Fritz, 2016). Women who had experienced coercive control victimisation had lower levels of self-esteem, confidence, sense of safety and life satisfaction (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Men and women who had experienced coercive control victimisation were more likely to experience mental health related symptoms such as difficulty sleeping, nightmares and depressive symptoms (Myhill, 2015). However, it is noteworthy that a study specifically measuring depressive symptoms among women did not report a significant association between coercive control victimisation and depressive symptoms (Levine & Fritz, 2016).

As we note above, due to the research designs of the reviewed studies, the relationship between these mental health symptoms and coercive control victimisation is also not fully established. Previous research suggests that experiences of IPV can lead to elevated PTSD symptoms. However, because much of the data on coercive control victimisation and mental health challenges, such as PTSD symptoms, are collected at the same time, we cannot be entirely sure if PTSD symptoms are a consequence of coercive control, or if they instead might place people at greater risk of coercive control victimisation or be associated with some other previous non-IPV related trauma experiences of the victim-survivor.