Beyond 'drink spiking'

Drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

November 2003

Download Practice guide

Overview

Current media representations of drink spiking tend to ignore the realities of most sexual assaults that occur in the context of heavy alcohol consumption. The author of this paper states that to avoid the re-emergence of victim-blaming stereotypes, drink spiking must be situated in the broader context of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault. Australian data sources on the prevalence of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault are discussed, followed by an exploration of media responses to this issue. Awareness and prevention approaches that treat drugs and alcohol as weapons are then presented.

Introduction

In recent years, the problem of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault has been receiving increased attention in Australia from sexual assault service providers, police, and law reform bodies. However, media interest in this issue has largely been restricted to the specific problem of "drink spiking", and generally understood to involve the covert addition of an illicit substance to a drink in order to facilitate sexual assault. In July this year, a media debate erupted around whether drink spiking was at "epidemic" levels, or just an "urban myth".

This article examines some key issues in that debate, focusing in particular on how media (mis)representations of the phenomenon of alcohol induced sexual assault has led to the recall of traditional victim-blaming stereotypes.

A key concern is that media reports and community perceptions of drink spiking do not reflect the experience of most victims of drug or alcohol assisted rape, and seem largely unaware of reforms to rape laws that suggest consent is vitiated where a person is heavily intoxicated. This article seeks to locate drink spiking in the broader context of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault, the majority of which involves voluntary ingestion by the victim.

The article starts with a review of Australian data sources on the prevalence of drink spiking and/or drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault, and considers the discrepancy between victim-based prevalence estimates, and those based on forensic investigation following a report to police. It then considers the media response to findings that suggested most victims of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault had voluntarily consumed high levels of alcohol. The media concluded that what they had previously described as a drink-spiking epidemic was in fact an "urban myth". The construction of drink spiking as an urban myth is concerning because it resurrects an old stereotype of women lying about consensual sex that they later regret. The belief that women frequently "cry rape" in such circumstances has long been used to dismiss women's reports of sexual assault, especially where victims are intoxicated.

A variety of prevention campaigns conducted by police and sexual assault service providers targeting drink spiking will then be examined. Mostly, these have taken the form of community awareness projects where alcohol and other drugs are constructed as the new "weapon" used in the commission of sexual assault. Responsibility for preventing sexual assault is often inadvertently located with women, as they are warned to "watch their drink" and "watch their friends". It is suggested that these responses ultimately help to sustain a victim-blaming mythology, and fail to acknowledge the complex debates about cultural and legal definitions of sexual assault, and women's (in)capacity to consent, in situations where they are heavily intoxicated.

Australian data sources on prevalence

Establishing the prevalence rates of drink spiking in Australia has been particularly controversial. This is chiefly due to a discrepancy between prevalence studies that rely on victims' disclosures to services versus studies that rely on the forensic (toxicological) investigation of incidents of drink spiking reported to police. Services indicate that sexual assaults involving drugs and/or alcohol are both common and on the increase, yet toxicology tests are failing to find any "rape drugs" in samples analysed from victims who report drink spiking to police.

However, this discrepancy is largely the result of different conceptions of the problem. Victim centred statistics (those provided by sexual assault services) focus primarily on sexual assault, with the presence of drugs and/or alcohol being secondary. For services, the concern is not to try to distinguish between drink spiking and sexual assault in the context of voluntary ingestion. Forensic investigation, in contrast, is principally concerned with the presence or absence of drugs, and the question of whether ingestion was voluntary or involuntary. The veracity of a woman's claim that she was sexually assaulted becomes tied to the question "was she spiked?", and tests for spiking agents become tests of victim credibility.

Prevalence studies based on victim disclosures

Sexual assault service providers are seeing an increase in (mainly) young women who are reporting the involvement of drugs in sexual assault. Moreton and Bedford's (2002: 3) study on drink spiking was conducted because: "The Eastern and Central Sexual Assault Service has noted over a short period of time an increase in the numbers of crisis referrals where the victim of the sexual assault appeared to have been drugged prior to the assault. The numbers indicated that these incidences may not be isolated and that a trend may be emerging."

Since 1998, at the request of the Eastern and Central Sexual Assault Service (ECAS), the New South Wales Department of Health has collected statistics on incidents in which "a drug has been used as a weapon to facilitate sexual assault" (Moreton and Bedford 2002: 3). According to these statistics, 21.4 per cent of people presenting to the service during the year 2000 reported the use of drugs in their assault, increasing from 17 per cent the previous year. However, these statistics do not distinguish between voluntary and involuntary ingestion.

Forensic testing for drink spiking agents

The largest forensic studies on drink spiking have been conducted in America, and revealed high levels of alcohol, and much lower than expected findings for central nervous system (CNS) depressants, like Rohypnol and GHB. Slaughter's (2000) analysis of 2,003 specimens revealed GHB in 5.4 per cent, and flunitrazepam (FN), the benzodiazepine known as Rohypnol, in only 0.5 per cent of specimens. Although the numbers detected were small, the use of GHB and FN actually appeared to decline over the two-year study period. Alcohol was present in 63 per cent of the samples, and marijuana in 30 per cent. Similarly, Elsohly and Salamone (1999), with a sample of 1,179 specimens, found alcohol in 40.8 per cent, marijuana in 18 per cent, benzodiazepines in 8 per cent, and GHB in 4 per cent of specimens. Despite the low levels of "rape drugs" and high amounts of alcohol indicated by these studies, many subsequent reports concerned with drug facilitated sexual assault continued to focus exclusively on illicit drugs (for example, Schwartz et al. 2000; Smith 1999).

To date, there has been only one forensic study conducted in Australia to detect drugs in samples from victims specifically reporting drink spiking to police. Toxicology tests conducted by the Chemistry Centre in Western Australia between June 2002 and February 2003 on 44 cases of alleged drink spiking detected none of the CNS depressants normally associated with drink spiking, such as the benzodiazepines, GHB and ketamine (although it was acknowledged that GHB is extremely difficult to detect, even with early reporting). However, alcohol was present in 75 per cent of samples, with 31 per cent of all cases showing blood alcohol concentration levels in excess of 0.15 per cent. In the majority of cases, the level of alcohol was significantly higher than anticipated, based on the victim's self-assessment of consumption.

A victim-centred approach to prevalence

Robert Hansson, principal chemist at the Forensic Science Laboratory, who conducted the Western Australian study, offered two possible explanations for the levels of alcohol detected: either drinks are being spiked with additional alcohol, or people are underestimating the effects of alcohol or the amounts they consume. Similarly, Paul Dillon, from the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, argues that social attitudes towards alcohol consumption are more of a problem than drink spiking with illicit additives. He cites increases in women's drinking and the practice of people buying triple shots for unsuspecting friends, as indicative of the real source of the problem. Both these experts make the case for alcohol spiking, yet they are also reported as concluding that drink spiking is an "urban myth".1

From a victim perspective, drink spiking with illicit additives is not occurring at "epidemic rates". However, the broader problem of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault can be understood in the following terms:

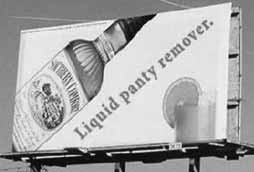

Parody alcohol advertisement circulated on the internet.

Reproduced with the permission of www.core-dev.co.nz/

A proportionally very small number of people are victims of what the media understands as "drink spiking" - sexual assault following the surreptitious administration of a sedative or hypnotic drug other than alcohol.

- There is evidence to suggest that increasing numbers of assaults are occurring after victims' drinks are spiked with alcohol. In these cases the perpetrator is a friend or acquaintance buying double or triple "shots" of spirits where the woman has voluntarily been consuming alcohol. Perpetrators generally have no conception of themselves as "drink spikers", given that using alcohol to lower inhibitions has been culturally sanctioned. The strength of the association between women's alcohol consumption and men's expectation of sexual activity was revealed when a parody of an alcohol advertisement circulated on the internet (see image, right) was widely mistaken for a legitimate ad campaign (Salkever 2001).

- Women are also being sexually assaulted when they are intoxicated from alcohol or other drugs that they have voluntarily consumed. This occurs when the offender knowingly engages in sexual acts with a person (almost always a woman) who is so affected by alcohol and other drugs that she is incapable of freely agreeing to sexual activity.

Media representations of the issue have never seriously entertained the possibility that the unexpectedly high levels of alcohol present in victim toxicology results might indicate drink spiking with alcohol. That sexual assault also occurs in the context of voluntary ingestion appears even more difficult to accept. This is not surprising, as a major difficulty for reformers has been securing public and legal recognition that sexual assault in the context of voluntary intoxication does in fact constitute "real rape".

1 When media interest in drink spiking intensified after the release of the Western Australian forensic study, Paul Dillon was frequently interviewed for radio and print media (for example, Radio National 2003). Dillon consistently argued that spiking with alcohol occurs, and emphasised that it constitutes physical assault. However, in articles where he is quoted, his comments on alcohol spiking are consistently bracketed off from "real drink spiking" in order to sustain the "drink spiking as urban myth" narrative favoured by the media.

Media responses: Urban myths and irresponsible women

Since the release of the Western Australian findings on drink spiking in July 2003, there has been a distinct shift in the media's response to the issue of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault. The change from touting drink spiking as an epidemic, to dismissing it as an urban myth, needs to be examined in terms of the way it represents drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault, and women who report it.

In 2002, the ABC's television program "7:30 Report" represented drink spiking as a growing problem in Australia requiring urgent attention. In the absence of reliable toxicology studies in Australia at the time, the media relied on the testimony of individual victims, and victim-centred prevalence reports provided by sexual assault services. The report described drink spiking as "putting something into someone's drink to take advantage of them", and included an interview with a victim whose experience accorded with the dominant conception of drink spiking - a woman who had been assaulted after a stranger had surreptitiously spiked her drink with an illicit substance.

The report warned of drink spiking being "widespread", and quoted statistics from two sexual assault service providers (ECAS and a Melbourne Centre Against Sexual Assault) to substantiate this claim. Several themes identifying drink spiking as "real rape" were evident in the report. In particular, there was the clear message that drink spiking made women "completely unable to resist". There was also an attempt to challenge any assumptions about where drink spiking was more likely to occur: "It's not uncommon for a person to have been out to a highly respectable place and end up as a victim of spiked drinks. So it's not necessarily a phenomenon associated with sleazy down-and-out bars in Kings Cross."

However, with the release of the Western Australian findings, the media placed greater emphasis on identifying "real victims" of drink spiking, and women reporting sexual assault involving drugs and/or alcohol became subject to this evaluation. Little consideration was given to the likelihood of women's drinks being spiked with alcohol rather than an illicit "rape drug", and no attention was directed toward sexual assault in circumstances where women were voluntarily consuming large quantities of alcohol.

A week prior to the official release of the West Australian findings, an article in The Age (13 July 2003), Authorities dubious on "epidemic", reported that "increasing numbers of people are claiming to be victims of drink spiking", yet authorities are seldom finding "proof that a crime has been committed". It also noted that "young people may be blaming drink spiking for their own misuse or misunderstanding of drugs they are voluntarily consuming", although in the second last paragraph it is suggested that "both police and the Drug and Alcohol Research Centre believe . . . drinks are being spiked - with more alcohol". In the article, Sheri Lawson, a counsellor/advocate from a Melbourne Centre Against Sexual Assault (CASA), is quoted as saying that "anecdotal reports suggest the crime is being committed and an increasing awareness is encouraging more women to report it". Interestingly, the only indication in the article that drink spiking relates to sexual assault is in noting CASA House as Sheri Lawson's workplace. She is also the only person to acknowledge the gendered nature of drink spiking. The article implies that because authorities are finding no "proof" of drink spiking, serious doubts about the likelihood of sexual assaults occurring in this context have also arisen.

On 17 July 2003, Queensland's Courier Mail released a report on the Western Australian forensic results, entitled Drink spiking epidemic an urban myth, say police, in which, once again, sexual assault is not mentioned, although there is a reference to "'date rape' drugs such as GHB". However, in this instance (given that the WA study was conducted as a result of public outcry over sexual assaults in the context of drink spiking), the reader is left in no doubt of the meaning of drink spiking, and that it is women who are most often claiming to be victims.

The article begins by establishing the "urban myth" narrative, stating: "Police have dismissed as an urban myth an apparent epidemic of drink spiking in Perth nightclubs, after tests on suspected victims found alcohol to be the only significant drug present." The article clearly locates women as the source of the confusion: "Police believe some young women were getting drunk at Perth nightspots and then using drink spiking as an excuse to justify behaviour they later regretted." The article quotes Alcohol and Drug Coordination Unit project officer Barry Newell as stating: "While we can't dismiss all cases, the results suggest that a fair proportion of drink spiking is just an urban myth . . . It seems that a proportion of young women are getting incredibly intoxicated and using drink spiking as an excuse to explain behaviour they are not happy with."

There is only brief reference, towards the end of the article, to an alternative scenario, again quoting Barry Newell: "It could be that men are purposely buying triple shots of spirits or the new high-alcohol sodas in order to get women intoxicated." However, there is no further analysis of this issue, or any connection made between the research findings and the broader problem of sexual assault occurring in contexts involving large quantities of alcohol. Instead, the implication is simply that women are "crying rape" to explain consensual sexual activity that occurred when they were drunk.

The next day, 18 July 2003, The Australian published an article entitled Spiked or just drunk too much?, which is almost identical in structure, content and style: identical quotes are given, the "urban myth" phrase appears, and again there is only cursory mention of the fact that men might be attempting to intoxicate women in order to facilitate sexual activity.

On 21 July 2003, an ABC radio interview with Robert Hansson was conducted around the question Drink spiking - a reality or urban myth? Unusually, the subsequent write-up emphasised spiking with additional alcohol: "If spiking is going on, it seems to be with alcohol . . . Perhaps that result is not surprising. Alcohol is legal, readily available and relatively cheap. Add to that, it can be difficult to effectively spike a drink with a powdered drug made from commercially available tablets, since those tablets are made up of largely inert, insoluble material that leaves a visible residue."

Immediately following this concession, however, the write-up concludes: "We've basically declared it [drink spiking] an urban myth." Hansson went on: "We believe it's just an excuse to hide abhorrent behaviour or inexperienced drinking, as a way of explaining, or trying to explain away, what young people are doing when they shouldn't be."

In these media reports, sexual assault is subsumed within the crime of drink spiking to such an extent that it literally cannot be spoken about without reference to a sedative or hypnotic substance, like Rohypnol, GHB, or ketamine. In the absence of "rape drugs", what women describe as sexual assault is turned into the problem (women's problem) of inexperienced drinking and risky, or even "abhorrent", behaviour.

Awareness and prevention approaches: Drugs and alcohol as "weapons"

While police and sexual assault services have become more alert to the phenomenon of drink spiking with illicit substances, they have rightly assumed that alcohol is by far the most common drug used in this context. Service providers in particular have also been active in demonstrating the strong association between alcohol and victim-blaming. Women's advocates have fought against the litany of stereotypes that have seen women as deserving or responsible for assaults that occur in circumstances where women have been socialising and/or consuming alcohol (Easteal 1993; Edwards and Heenan 1994; Scott et. al. 1995). Service providers have therefore been keen to communicate two messages in having alcohol recognised as the key spiking agent: that alcohol can have similar physiological effects to "rape drugs" like Rohypnol, and that women's consumption of alcohol should not be considered evidence of victim precipitation.

Poster from an American campaign: "Now rapists don't have to use force to get what they want. / Their weapon is drugs. Ruffies or GHB. Dropped in your drink. You can't fight back. Watch your drink. It's your best defence."

One approach in this context has been to identify the broad category of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault as rape achieved with a weapon (that is, the drug). The fundamentals of the drink spiking narrative are retained, but alcohol is added to the list of drugs, which becomes a list of weapons, that may be used in the commission of the crime. The theme of drugs as weapons first appears in American campaigns (see poster, right), which firmly inscribe drink spiking as a narrative of overcoming women's resistance to sex.

In Australia, campaigns have been less inclined to spell out what constitutes drink spiking. In an early article, Drugged and assaulted, McKey (2000: 21) speaks about "the drugging and sexual assault of unsuspecting night clubbers" and of "clients [of sexual assault services] being unwittingly drugged", but offers no explicit definition of drink spiking. Similarly, in a recent study simply entitled "Spiked Drinks", there is no precise definition given for drink spiking. However, it is clear that both writers are concerned with illicit drugs. McKey describes changes to Rohypnol to make it visible in drinks as a significant prevention strategy; and a classic drink spiking narrative of "slipping something into a drink" is pervasive in Moreton and Bedford's report. Images accompanying early campaigns (such as the one below) also sent a clear message about the nature of drink spiking.

Spiked drinks poster - do you know what you're drinking?

The definition of spiking offered in this campaign, Spiked - Means A Drug Has Been Added To Your Drink, implies that alcohol is not a drug, or at least not a "spiking" drug. The caution, Don't Leave Your Drink Unattended, and the image of a man disguised with a ski mask, implies that the perpetrators of drink spiking are likely to be strangers lurking unseen in the shadows of nightclubs premeditating their next strike.

Examining more recent campaigns directed at drink spiking reveals a move towards including alcohol among the list of spiking agents, and incorporating the metaphor of "drugs as weapons" into public awareness strategies.

The Australian Defence Force Drink Spiking Fact Sheet defined drink spiking as: "The covert placement of drugs (including alcohol) into a person's drink with the aim of sedating them, usually for the purposes of sexual assault or robbery . . . Alcohol is the most commonly used drug to facilitate sexual assault. This occurs when alcohol is added to a non-alcoholic drink or when an alcoholic drink has shots of spirits added to it without request" (ADF Fact Sheet).

The Manly "Don't Get Spiked" Awareness Campaign further demonstrates this trend: "The message of the campaign was that alcohol and drugs can be used as a weapon, making victims vulnerable to sexual assault, assault, robbery or other crimes. Patrons were encouraged to consider how they could prevent this from happening to themselves or their friends. The campaign conveyed a strong message that alcohol is a main contributor in spiked drink incidents [and] aimed to reduce the incidence of drink spiking and encourage protective behaviours in social settings" (Huxley and Meyers-Brittain 2001).

While the literature and associated campaigns acknowledge the centrality of alcohol rather than illicit substances in drink spiking, the focus has remained predominantly on the behaviour of potential victims, and prevention is generally reduced to women's risk management. This approach has been criticised by commentators such as Sheri Lawson (2003) whose article, "Surrendering the Night! The seduction of victim blaming in drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault prevention strategies", provides an important and insightful contribution to the debate on drink spiking. Lawson notes the failure, discussed above, to connect sexual assault with drink spiking in most media representations of the issue, and highlights the disproportionate emphasis in campaigns on women taking responsibility for avoiding sexual assault through modifying their own behaviour. She provides a breakdown of campaign messages into "victim directed" and "offender directed", with the greater proportion falling into the former category.2

The problem with much of the literature and campaigns targeting drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault is that the components of the drink spiking narrative are maintained: the surreptitious administration of a drug or additional alcohol is considered the primary mode of facilitating sexual assault. The metaphor of drugs or alcohol as "weapons" re-situates sexual assault as a crime involving force and resistance or, more specifically, women's capacity (and indeed their obligation) to resist.

Moreover, the "weapon" metaphor can only function as long as definitions of drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault exclude situations involving voluntary ingestion by victims. A weapon is actively employed or used by a perpetrator to ensure submission; incapacitation resulting from voluntary ingestion cannot figure in an analysis that positions drugs as weapons.

Implicit within the "drugs as weapons" metaphor is a concern with the victim's capacity to consent. However, women's advocates have demonstrated that conceptualising rape as a crime centred around force and resistance has led to a focus on women's behaviour and conduct - did she fight back, sustain injuries, tear her clothing? When a focus on consent is displaced by a search for evidence of force and resistance, it becomes all too easy to hold women responsible for sexual assault. The proliferation of advice about "protective strategies", which urge women to modify their behaviour in order to avoid rape, provide the clearest indication that more progressive notions of consent are being reduced to a traditional understanding of rape as dependent on proof of force and resistance.

"Real rape", in the context of drink spiking, is demonstrated when a woman claims to have been sexually assaulted, and her allegation is supported by a positive toxicology test. Under these circumstances, proof of assault lies in forensic evidence of a CNS depressant as the weapon used to overcome resistance. The presence of a drug ultimately signals a lack of consent. In the meantime women can undertake various behaviour modifications to prevent "real rape" in the context of "real drink spiking" by not going out alone at night, going to dangerous areas, wearing revealing clothing, being provocative, leaving drinks unattended, or accepting drinks from strangers. They must also watch themselves, watch their friends, and rigorously check the colour, odour and fizziness of their drinks.

What is often missing from media reports and prevention strategies is acknowledgement of the extent to which drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault occurs in the absence of spiking - in other words, where a woman is sexually assaulted after having voluntarily consumed alcohol or other drugs to such an extent as to be incapable of freely agreeing to sex.

Sexual activity that occurs when women are too intoxicated to freely consent is occasionally discussed in the literature on young people and alcohol abuse. However, there is a tendency to subsume sex in this context under the rubric of alcohol related harm (for which inebriated women are responsible) rather than examining it as a crime involving a victim and a perpetrator. For example, an article entitled The morning after: young people, sex and alcohol carries the by-line "Unplanned, unwanted and unsafe sex are commonplace, it seems, when alcohol and young people come together" (Wood 1999: 13, emphasis added). Another example is the Salvation Army's recent Alcohol Awareness Survey, which found that "22 per cent of girls are drinking between 13 and 30 drinks in a session" and that "over 21 per cent of girls after drinking had experienced unwanted sexual activity" (2003: 2, emphasis added). The meaning of "unwanted sexual activity" is unclear. However, the level of alcohol consumption involved (13-30 drinks) would seem to indicate that at least some of this "unwanted" sex occurs when young women are so intoxicated as to be incapable of consenting to sexual relations.

The legal position in most states and territories in Australia is that sexual assault can occur in the context of voluntary ingestion of drugs or alcohol precisely because the victim is intoxicated and therefore unable to consent to sexual activity. Hence, what is often euphemistically termed "unwanted sexual activity" in the context of young people's consumption of drugs and alcohol, may well constitute sexual assault under the law. Sexual assault in the context of voluntary ingestion is not a harm resulting from women's intoxication; it is a crime resulting from men's disregard for a lack of consent, or recklessness in ascertaining whether consent is present or can even be formed.

2 Importantly, sexual assault services in Australia have endeavoured to design campaigns or prevention strategies that retain a focus on the offender, or the potential offender's, behaviour. The South Australian rape and sexual assault service, Yarrow Place, distributed drink coasters to licensed premises that carried messages such as: "No always means No"; "Will you take No for an answer? Are you sure you want to face the consequences?"; and "Too out of it means No". Sexual assault services in Victoria and Tasmania adopted similar themes in approaching licensed premises to place stickers and other materials in bars and clubs with slogans that target men taking responsibility for potentially criminal behaviour.

Conclusion

Media interest in drug and alcohol facilitated sexual assault, and attempts by service providers and police to raise awareness of the problem, have prompted a resurgence in representations of rape that centre on notions of force, resistance, responsibility and blame. In conceptualising drugs and alcohol in sexual assault as "weapons" to overcome resistance, it is easy to loose sight of the two elements that underpin sexual assault as a crime: a woman's right to sexual autonomy regardless of her sobriety; and a perpetrator's violation of that right.

References

- ABC (2002), 7:30 Report: Police call for greater sexual assault awareness, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney.

- Easteal, P. (1992), "Rape prevention: Combating the myths", in P. Easteal (ed.) Without Consent: Confronting Adult Sexual Violence: Proceedings of a Conference held 27-29 October 1992, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

- Edwards, A. & Heenan, M. (1994), "Rape trials in Victoria: Gender, socio-cultural factors and justice", Australia and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, vol. 27, pp. 213-236.

- El Sohly, M.A. & Salamone, S.J. (1999), "Prevalence of drugs used in cases of alleged sexual assault", Journal of Analytical Toxicology, vol. 23, pp. 141-146.

- Huxley, J. & Meyers-Brittain, J. (2001), "Drug and/or alcohol facilitated sexual assault: A growing concern", presented at Seeking Solutions: Australia's Inaugural Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault Conference, available at http://adfvc.arts.unsw.edu.au/Conference%20papers/Seek-soln/Meyers-Brittain,Jillian.pdf

- King, D. (2003), "Spiked or just drunk too much?", The Australian, 18 July, Downloaded from www.newstext.com.au on 24 September.

- Lawson, S. (2003), "Surrendering the night! The seduction of victim blaming in drug and alcohol facilitated sexual prevention strategies", Women Against Violence, Issue 13, pp. 33-38.

- Lennon, D. & Reid, S. (2003), "Drink spiking: A reality or urban myth?", Transcript from 21 July, available: http://www.abc.net.au/rn/lifematters/stories/2003/914309.htm

- McKey, J. (2000), "Drugged and assaulted", Connexions, February/March, pp. 21-24.

- Moreton, R. & Bedford, K. (2002), "Spiked drinks: A focus group study of young women's perceptions of risk and behaviours", Central Sydney Area Health Service.

- Medew, J. (2003), "Authorities dubious on 'epidemic'", The Age, 13 July.

- Mayes, A. (2003), "Drink spiking epidemic an urban myth, say police", The Courier Mail, 17 July.

- Radio National (2003), Life Matters, 01/08, available at http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/lm/stories/s914309.htm

- Salkever, A. (2001), "Southern Comfort's Internet Hangover " Business Week, 09/01, available at: www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/jan2001/nf2001019_870.htm

- Schwartz, R., Milteer, R.& LeBeau, M. (2000), "Drug facilitated sexual assault ('Date Rape')", Southern Medical Journal, vol. 83, no. 6, pp. 558-561.

- Scott, D., Walker, L. & Gilmore, K. (1995), Breaking the Silence: A Guide to Supporting Adult Victim/Survivors of Sexual Assault, Second Edition, CASA House, Royal Women's Hospital, Melbourne.

- Slaughter, L. (2000), "Involvement of drugs in sexual assault", The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, vol. 45, no.5, pp. 425-430.

- Smith, K. (1999), "Drugs used in acquaintance rape", Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 519-525.

0-642-39508-X