Planning for safety with at-risk families: Resource guide for workers in intensive home-based family support programs

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

May 2013

Marie Iannos, Greg Antcliff

Developing and implementing a meaningful safety plan is a collaborative process undertaken by the worker and family together to address immediate safety issues and set goals for the intervention. This resource guide describes practical tips to assist family support workers develop and implement a safety plan with their clients, and draws upon the principles from the Signs of Safety practice framework (Department for Child Protection, 2011; Turnell, 2012) and evidence based practices for working with families at risk of abuse and neglect (De Panfillis, 2006).

Developing a meaningful safety plan is a collaborative process undertaken by the family and worker together and focuses on a fundamental question: what needs to happen to ensure the children will be safe in their own family?

The goal of intensive home-based support programs for vulnerable high-risk families is ensuring that children stay safe and remain within their family. Intensive home based family support programs aim to reduce re-notification or re-substantiation risk, close the case without court involvement, prevent the removal of children into alternative care, or facilitate family reunification. These programs are usually of long term duration (up to 12 months) and require frequent weekly worker contact with families.

Increasing safety is one of several core outcomes identified by the Resilience-Led Approach (Daniel, Burgess, & Antcliff, 2011) which can be used across all child protection work. Safety can be considered as the parent's capacity to provide physical safety (where children are kept safe from abuse/neglect and family violence), environmental safety (stable and secure housing which is hygienic and free from hazards), and adequate physical care (nutrition, hygiene, healthcare).

Developing and implementing a meaningful safety plan is a collaborative process undertaken by the worker and family together to address immediate safety issues and set goals for the intervention.

Planning for safety

Understanding the context of family problems

Families referred to intensive home-based family support programs often have multiple issues and complex needs. This can feel overwhelming for both worker and family. Address the family's basic survival, safety and security needs first.

The risk factors most commonly associated with the occurrence of child abuse and neglect include domestic violence, parental substance abuse, parental mental health problems, and parental disability (physical/intellectual). These issues often occur within a wider context of economic and social disadvantage and become part of a complex inter-related group of problems (Bromfield, Lamont, Parker, & Horsfall, 2010).

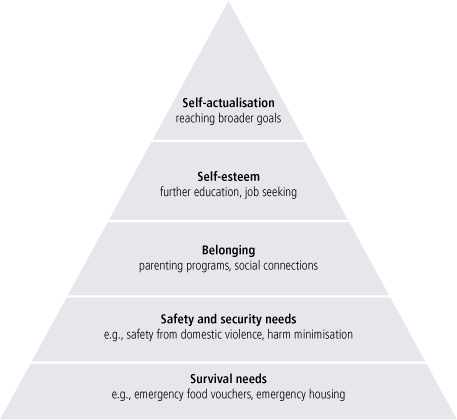

Trying to tackle all the problems facing the family simultaneously can be overwhelming. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs theory tells us that people are unlikely to be able to focus on their family relationships if their survival and safety needs are not being met first (see Figure 1). Therefore families with complex problems may not have the capacity to engage in parenting interventions if they are still being exposed to domestic violence, unable to meet their children's basic needs for stable housing, food and clothing, or cannot pay the rent. It is not until these basic survival, safety, and security needs are met that any other interventions worked into the safety plan will be effective.

Figure 1. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Source: McAdams, 2006, cited in Bromfield et al., 2010, p. 16.

Engage the family

Parents may be reluctant to engage due to negative past experiences with service providers, and it may take time to build a trusting relationship. Engaging the family is a good place to start.

Raising the safety concerns with the family requires sensitivity and care, so engaging the family in a collaborative partnership is crucial. Miller and Bromfield (2010) reported that several ways to build rapport and trust include:

- approaching the family in a non-judgemental way;

- being respectful and courteous;

- developing trust through sensitive and inclusive enquiry about their circumstances;

- focusing on building the family's strengths;

- taking an active, caring, whole of family approach to their situation;

- focusing on the children's needs;

- establishing shared decision making;

- maintaining a continuous relationship with the family; and

- remaining culturally aware and sensitive.

In light of the complexities of the family's issues, how do workers go about creating a safety plan with a family? The Signs of Safety approach has been adopted as the practice framework by the Western Australian Department for Child Protection (2011). The Signs of Safety Framework utilises the principles of Turnell and Edwards' (1999) seminal work Signs of Safety, which described a practical approach to child protection casework.1

The Framework outlined that planning for safety with families requires the practitioner to ask four basic questions which can be recorded on a form and then used as a collaborative tool to assist the safety planning process. Table 1 shows an example of the simplified Signs of Safety assessment and planning protocol developed by Turnell (2012). The protocol describes the four domains of enquiry as:

- What are we worried about?

- What's working well?

- What needs to happen?

- How safe is the family (on a scale of 0 to 10)?

The example used in Table 1 demonstrates the areas of concern that may be explored with a mother who has a history of depressive illness and suicide attempts, has recently left a violent relationship, and is struggling with financial difficulties.

| When we think about the situation facing this family: | ||

|---|---|---|

| What are we worried about? | What's working well? | What needs to happen? |

Jane's ex-partner John has been violent towards her. Her son, Jack, has witnessed the violence. Jane has a history of depression which she calls "being blue" and has difficulty coping with Jack when she feels like this. Jane does not have enough money to pay the rent this month. | Jane has separated from John and has taken out an AVO. Jack reported he feels safer now that John is no longer living with them. Jane recalls when she was taking her medication and seeing her psychiatrist regularly she felt better and was coping better with Jack. | Jane must call the police if John tries to make contact with her. Jane must be able to cope with her depression and provide good care to Jack even when she is feeling blue. This means:

Worker will help Jane obtain emergency rent assistance. |

| On a scale of 0-10 where 10 means everyone knows the children are safe enough for the child protection authorities to close the case and 0 means things are so bad for the children that they can't live at home, where do we rate this situation? (if different judgements place different people's number on the continuum) | ||

* Signs of Safety assessment and planning protocol reproduced with permission from Turnell, A. (2012). The Signs of Safety® is a proprietary trademark owned by Resolutions Consultancy Pty Ltd, Perth Western Australia.

Identify safety concerns

What are we worried about? Clearly articulating the safety concerns is important as they define the fundamental issues that the program will address

Safety planning starts with being able to clearly articulate the family's safety concerns. It is helpful to:

- openly discuss and clearly define the safety concerns facing the family using simple language. Prioritise the basic survival and safety needs first - e.g., "Jane does not have enough money to pay the rent this month"; and

- after all the safety concerns have been discussed, collaboratively assess the family's overall level of safety by asking the family to rate their level of safety on a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 = very unsafe/child must be removed and 10 = very safe/no further assistance required.

Once the worker and family are clear about the safety issues, this will make it easier to develop goals.

Acknowledge family strengths

What's working well? Recognise and utilise the family's own strengths and resources as much as possible.

Explicitly identifying the family's safety concerns can be a challenging conversation for a worker who does not wish to jeopardise engagement. It is therefore important to adopt a strengths-based approach. Continually identify and honour the family for everything they can see that is positive in their everyday care and involvement with their children.

The worker's main task here is to ask the family to come up with their "best thinking" about what they can do to ensure the children stay safe (DCP, 2011). In this way, parents may be much more likely be able to openly discuss the safety issues and work collaboratively to set safety goals. During this process, is important to:

- incorporate the family's existing personal strengths and resources as much as possible, and record these on the safety plan - e.g., "Jane has separated from John and has taken out an AVO". This includes other people in their safety network (e.g., friends, relatives, professionals); and

- encourage and compliment the activities the family already does to create a safe environment and provide good care of the children.

Set safety goals

What needs to happen? The goals of the safety plan should clearly describe in behavioural terms the specific actions parents need to undertake in order to ensure the family's safety. Goals should be SMART (See Box 1) (De Panfillis, 2006).

Goal setting is an important aspect of the safety planning process. Safety goals should be targeted towards achieving desired outcomes for the family that demonstrate a reduced risk of abuse/neglect and increase safety and stability (De Panfillis, 2006). The goals should clearly describe the specific actions parents and/or the worker needs to undertake in order to achieve the family's safety outcomes. This means describing the behaviours they should do more of, rather than simply focus on reducing behaviours (what they should do less of). For example, "Jane will call the police if John tries to make contact with her". Effective safety goals can be developed using the SMART acronym, as show in Box 1.

Box 1: SMART goals

Specific - the family knows exactly what has to be done.

Measurable - goals should be measurable, clear and understandable so everyone knows when they have been achieved.

Achievable - the family should be able to accomplish the goal in a designated time period given their available resources.

Realistic - the family should have input and agreement in developing feasible goals.

Time-limited - time frames for goal accomplishment should be determined based on understanding the family's risks, strengths, ability and motivation to change, and availability of resources.

Source: De Panfilis (2006, p. 65)

Maintain safety: review progress

Planning for safety is a dynamic process, which is co-created by the family and includes an informed safety network. It must also adapt to the family's progress and changing circumstances as they achieve their safety goals

A safety plan is collaboratively created and needs to be "owned" by the family to be meaningful. It should "contain detail around the what, how, who, where and when, and adapt to progress and changing circumstances" (DCP , 2011, p. 28). The plan should be regularly reviewed to adapt to the family's progress as they achieve their safety goals. According to the Signs of Safety Practice Framework (DCP, 2011, p. 29), when reviewing the family's progress workers are encouraged to consider the following questions:

- What changes/actions on the safety plan has parent achieved? Acknowledge and celebrate the family's successes.

- What safety goals are yet to be achieved? What behaviours do we still need to see from the parent in order to achieve these goals?

- Does the parent have some strategies to cope when faced with a crisis? Who will step in and support?

- What needs to be put in place (resources, services, people), by whom and by when, in order for the parent to maintain safety, stability and security for the children?

Conclusion

Planning for safety is a key practice element for service providers of intensive home-based family support programs for high-risk families with multiple complex problems. The ultimate aim is to ensure the parent is able to provide adequate safety, stability and security so that the children can stay safe within their family. Creating a safety plan is a collaborative task undertaken by parents and worker together, rather than a set of "rules" imposed on the family. Engaging the family respectfully, and acknowledging and utilising the family's strengths are essential. Addressing the family's basic survival and safety needs (physical safety, food, shelter, and clothing) should be prioritised above other interventions (e.g., parenting strategies) within the program. Safety goals should be clearly articulated in behavioural terms. Workers are encouraged to review the safety plans regularly as the family achieves their safety goals within the program, as well as work into the plan how the family will manage any crises that may arise.

Resources

Additional reading and resources are available from the Signs of Safety website

References

- Bromfield, L., Lamont, A., Parker, R., & Horsfall, B. (2010). Issues for the safety and wellbeing of children in families with multiple and complex problems: The co-occurrence of domestic violence, parental substance misuse, and mental health problems (NCPC Issues Paper No. 33). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues33/>

- Daniel, B., Burgess, C., & Antcliff, G. (2011). Resilience practice framework. Paddington, Sydney: The Benevolent Society.

- De Panfilis, D. (2006). Child neglect: A guide for prevention, assessment and intervention (Child Abuse and Neglect User Manual Series). Washington: Child Welfare Information Gateway.

- Department for Child Protection. (2011). The Signs of Safety child protection practice framework (2nd ed.) (PDF 1.2 MB). Perth: Government of Western Australia, Department for Child Protection. Retrieved from <www.dcp.wa.gov.au/Resources/Documents/Policies%20and%20Frameworks/SignsOfSafetyFramework2011.pdf>.

- Miller, R., & Bromfield, L. ( 2012). Cumulative harm: Best interests case practice model specialist practice resource. Melbourne: Victorian Government Department of Human Services. Retrieved from

<www.dhs.vic.gov.au/for-service-providers/children,-youth-and-families/child-protection/specialist-practice-resources-for-child-protection-workers/cumulative-harm-specialist-practice-resource>. - Turnell, A. (2012). Signs of Safety: Briefing paper (2nd ed.). Perth: Resolutions Consultancy. Retrieved from <www.signsofsafety.net>

- Turnell, A., & Edwards, S. (1999). Signs of Safety: A safety and solution oriented approach to child protection casework. New York: WW Norton.

Endnote

1. The information described in this resource describes the basic principles of the Signs of Safety® approach only, and should not be considered a substitute for practitioner training in the use of the Framework. More information is available at Signs of Safety