Sexual revictimisation

Individual, interpersonal and contextual factors

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

May 2014

Download Practice guide

Overview

There is a complex array of variables related to sexual revictimisation. Although prevalence is difficult to ascertain, several studies relate that people who have been sexually abused as children are two to three times more likely to be sexually revictimised in adolescence and/or adulthood. Much of the literature on sexual revictimisation focuses on the individual risk factors for the victim/survivor - their risk perception and emotional dysregulation resulting from initial sexual victimisation - and how these create vulnerability for sexual revictimisation. Broader contextual factors beyond the victim/survivor, however, are often ignored.

These contextual factors are explored here with a particular emphasis on minority groups, such as people with a disability; gay, lesbian and bisexual people; and Indigenous people. This focus demonstrates that individual risk factors often do not account for how perpetrators may target vulnerable people who have previously been victimised, how community and organisational attitudes and norms may support sexual revictimisation, and how broader social norms create vulnerability for certain groups. A focus on these broader contextual factors helps to inform prevention strategies.

Key messages

-

People who are sexually abused in childhood are two to three times more likely to be sexually revictimised in adolescence and/or adulthood.

-

Individual risk factors include a history of child sexual abuse, poor risk perception, emotional dysregulation, cumulative past abuse, family conflict and distress.

-

Broader contextual factors, such as perpetrator tactics, community and organisational attitudes, and social norms, are also risk factors for sexual revictimisation.

-

Those vulnerable to sexual revictimisation, including minority groups such as people with a disability; gay, lesbian and bisexual people; and Indigenous people may require greater support and advocacy in order to alleviate trauma and trauma symptoms, and increase their resilience.

-

Similar strategies used in the sexual violence primary prevention space may be used to prevent sexual revictimisation. This includes respectful relationships education, gender equity principles and a focus on important sites of social norm reproduction, such as sporting sites and the media, to convey messages of respect and equality.

Introduction

There are complex variables that contribute to sexual revictimisation, including individual, interpersonal and contextual factors. Sexual revictimisation can be defined in various ways, but for the purposes of this summary it will include any sexual abuse or assault subsequent to a first abuse or assault that is perpetrated by a different offender to the initial victimisation. Usually this will mean a child sexual abuse followed by an adolescent or adult sexual revictimisation, or an adolescent sexual abuse followed by an adult sexual revictimisation, by a different perpetrator. It can also be defined as multiple adult victimisation experiences by different perpetrators. It is important to attempt to work through how and why sexual revictimisation is so prevalent and what can be done to better identify risks associated with the perpetration of sexual revictimisation—one perpetrator offending multiple times, or offending against a person who has previously been victimised.

Most literature concerning sexual revictimisation iterates that those who are victims of child sexual abuse are two to three times more likely to be sexually revictimised in their lifetime (Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005; Grauerholz, 2000; Heidt, Marx, & Gold, 2005; Noll & Grych, 2011; Ogloff, Cutuajar, Mann, & Mullen, 2012). However, there is very little literature available that brings together all the contextual factors related to sexual revictimisation. Data can be difficult to collate on minority or vulnerable groups who might best be described as falling through the gaps between services and justice mechanisms. This is particularly true of gay, lesbian and bisexual people, Indigenous people and people with a disability.

The interpersonal and contextual factors related to sexual revictimisation will be explored in this paper. The discussion begins with a look at what is known about the prevalence of sexual revictimisation and the associated risk factors, specifically for heterosexual populations, and then for the minority or vulnerable populations outlined above.

The prevalence of sexual revictimisation

The prevalence rates for sexual revictimisation are worryingly high for both men and women who have experienced child sexual abuse; they are two to three times more likely to experience subsequent abuse in adolescence or adulthood. This statistic is certainly supported by several studies, some of which are outlined below (Chiu et al., 2013; Classen et al., 2005; Desai, Arias, Thompson, & Basile, 2002; Ministry of Women's Affairs, 2012; Noll & Grych, 2011; Volker, Randjbar, Moritz, & Jelinek, 2013). An even stronger correlation has been found between young women who are sexually abused in adolescence and subsequent adult sexual abuse victimisation (Classen et al., 2005).

General prevalence studies

Large- and broad-scale studies tend to assume sexuality through omission of questions related to sexuality in their surveys, therefore it is unclear as to whether the prevalence and the factors associated with recidivism differ between heterosexual and non-heterosexual groups. Despite large-scale studies being conducted on the issue of revictimisation, our understanding remains murky, as definitions of sexual revictimisation vary among studies.

One such study by Chiu et al. (2013) examined the results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey for the prevalence and overlap of childhood and adult physical, sexual and emotional abuse. The 2,301 men and 3,201 women in the survey who reported a history of childhood abuse were more likely to also have experiences of adult sexual abuse. Participants in this study who had at least one type of child abuse incident were 5.8 times more likely to experience an adult abuse incident (Chiu et al., 2013).

The researchers also reported that:

the prevalence of adulthood sexual abuse was 15% among men who reported one type of childhood abuse, 28% among men who reported two types of childhood abuse, and 57% among men who reported three types of childhood abuse. (Chiu et al., 2013, p. 391)

The prevalence was slightly higher for women. The finding that exposure to multi-type maltreatment1 is associated with subsequent adolescent or adult victimisation is iterated by other researchers (Classen et al., 2005; Desai et al., 2002; Ministry of Women's Affairs, 2012). The study by Chui et al. (2013) does not delineate between heterosexual, gay, lesbian or bisexual participants, but does include a representative sample of diverse races/ethnicities as per the greater Boston population.

In a large-scale, nationally representative telephone survey looking at child sexual abuse and subsequent adult revictimisation, Desai et al. (2002) found women who had experienced child sexual abuse were three times more likely to be revictimised in adulthood. Men were also three times as likely to experience revictimisation if they had been sexually abused in childhood (Desai et al., 2002). In other words, more people who had experienced child sexual abuse went on to be revictimised in adulthood. One of the reasons given for this heightened risk of revictimisation is the emotional dysregulation and reduced risk perception of victimised individuals.

One clear message in the literature is the need to consider greater supports for children following an experience of child sexual abuse to temper the individual risk factors relevant to sexual revictimisation (discussed later in this summary).

Gay, lesbian and bisexual communities

A community of people often absent from discussions of sexual revictimisation continues to be gay, lesbian and bisexual people. This can work to maintain the marginalised position that minority sexualities experience and can play a role in perpetuating the belief that sexual abuse and revictimisation does not occur as often or as destructively for gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals (Fileborn, 2012).

Very few studies look specifically at sexual revictimisation for gay men, lesbian women and bisexual men and women (Heidt et al., 2005; Hequembourg, Livingston, & Parks, 2013). One study by Heidt et al. (2005) began work in this field in order to at least present an initial prevalence rate of revictimisation for gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals on which other research could be built. They surveyed 307 individuals (139 male, 168 female: 118 gay men, 123 lesbians, 66 bisexual men and women). The authors defined sexual revictimisation as oral and vaginal contact or penetration in both childhood and adulthood (Heidt et al., 2005).

The researchers surveyed the participants about depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, life experiences and sexual experiences. They found that 39% of the participants reported both a childhood sexual abuse incident and a subsequent adult sexual victimisation incident. Although this study is not representative, it offers an insight into revictimisation rates for gay, lesbian and bisexual populations, and highlights the need for greater research and for psychological services to be geared towards offering support and counselling for gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals who have been sexually revictimised (Heidt et al., 2005).

Hequembourg et al. (2013) cite research indicating that rates of child sexual abuse may be higher among bisexual and lesbian women - "15% to 76% among bisexual women and from 18% to 60% among lesbian women" (p. 636) - than among heterosexual women (up to 29%). Yet "despite a pernicious pattern of revictimization among heterosexual female child sexual abuse survivors, little is known about the patterns of revictimization among sexual minority women with histories of [child sexual abuse]" (p. 637). There is still a need for further research that can more clearly elucidate the rates of sexual revictimisation as well as the differences and similarities in the experiences of diverse sexualities and sexual revictimisation.

Indigenous communities

The history of forced resettlement on reserves, the placing of many thousands of children in institutions, and the loss of land and culture are evident in the disadvantages still experienced by many Aboriginal people today. (Australian Law Reform Commission, 2014, para. 29)

It is a significant task to undo the complex interplay of social disadvantages imposed by white settlement.. Although it is well documented that Indigenous communities experience disadvantage and high levels of abuse and violence, no work has specifically investigated the rates of sexual revictimisation in a focused way (Keel, 2004).

What is known is that child sexual abuse notifications in Indigenous communities are five times greater than those for non-Indigenous communities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012, Tables A1.34 and A31.37). Indigenous women are also up to four times more likely to be the victims of sexual assault than non-Indigenous women (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2012). Although there are no statistics outlining revictimisation rates for Indigenous men and women, the above statistics do give rise to the notion that sexual revictimisation would be prevalent in Indigenous communities.

People with disabilities

Like other chronically disadvantaged and invisible groups in society, some people with disabilities deal with a complex constellation of social ills. Although there are excellent organisations that advocate on behalf of people with disabilities to gain greater visibility, sexual revictimisation experiences of people with disabilities are often not represented in nationally representative safety and crime statistics. This means that less is known about prevalence within these communities. People with disabilities are, however, at greater risk of experiencing sexual assault and sexual revictimisation as they may be specifically targeted due to their perceived vulnerability (Murray & Powell, 2008).

People with cognitive disabilities may be unable to disclose or even recognise abuse, which means prevalence statistics for revictimisation are not readily available. Unfortunately, nationally representative surveys related to sexual victimisation do not ask for the disability status of participants (Murray & Powell, 2008). What is known is that that "approximately 20% of Australian women, and 6% of men" with a disability will experience sexual victimisation some time in their lives (ABS, 2006, as quoted in Murray & Powell, 2008). These statistics unfortunately do not help us in calculating rates of revictimisation.

Summary of what is currently known about the prevalence of revictimisation

It is clear that the risk of sexual revictimisation is high for people who have experienced child sexual abuse (as opposed to multiple adult victimisation experiences, for example, for which statistics and data are difficult to elucidate due to the paucity of research in this area). Vulnerable groups are at particular risk, although a distinct lack of research and evidence obscures actual prevalence and complicates prevention efforts. There are a number of ways to understand sexual revictimisation; however, many of them focus on the obvious common denominator of the victim, while ignoring the tactics that perpetrators use to target vulnerable people and the broader cultural context that may contribute to sexual revictimisation (Clark & Quadara, 2010; Council of Australian Governments, 2011; Ministry of Women's Affairs, 2012). The following section outlines a theoretical framework that helps to shape a more holistic understanding of the risks of sexual revictimisation.

1 Multi-type maltreatment describes five overlapping types of child maltreatment - physical, sexual, psychological, neglect and witnessing family/domestic violence. (For more information please see Higgins & Price-Robertson, 2011; Higgins & McCabe, 2003.)

Theoretical framework for revictimisation

A lack of adequate understanding about why and how sexual revictimisation occurs means the focus has been placed on what is known: the victim/survivor. This is where the victim/survivor's experiences, life circumstances and decisions become the focal point for intervention. While the literature presented in this paper will outline some identified risk factors for victim/survivors, it will use Grauerholz's (2000) socio-ecological model to explore how broader contexts relate to sexual revictimisation, and what avenues may be best explored, beyond the victim/survivor, in identifying risk factors for sexual revictimisation.

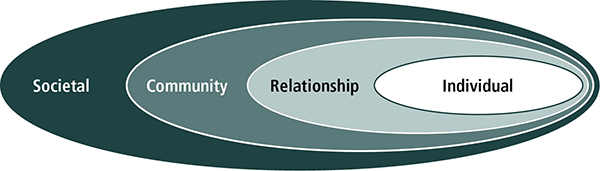

The socio-ecological model is commonly used in violence and sexual assault prevention and was used initially in public health prevention when it was adapted from Bronfenbrenner (1977). The model indicates the interrelated aspects of social life and how they all play a part in forming behaviours, such as those related to revictimisation (Figure 1). The socio-ecological model starts with the societal sphere, which encompasses the community or organisational sphere, within which is the interpersonal or relationship sphere, and finally the individual sphere.

Figure 1: The socio-ecological model

Source: Quadara & Wall, 2012, p. 4

Although the victim/survivor is necessarily at the centre of the investigation into revictimisation - as it is only through sexual abuse and assault victim statistics that we know anything of revictimisation - the phenomenon of sexual revictimisation can only really be understood by considering the four levels of the socio-ecological model: individual, relationship, community and societal The pertinent questions are how do these levels affect a victim/survivor's behaviour and what supports do these levels provide for a perpetrator to sexually revictimise the victim/survivor?

Individual factors for the victim/survivor: Risks, impacts, correlates

The individual level of the socio-ecological model - the victim/survivor - is often where the focus lies when seeking to identify risk factors. There is a range of literature regarding the demographic features and characteristics of sexual abuse and assault victim/survivors (Classen et al., 2005; Desai et al., 2002; Ministry of Women's Affairs, 2012; Volker et al., 2013; Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, 2012). It is important to have clarity on who is at risk and how to best respond to them, so this literature has been invaluable in the field of sexual assault research, policy and practice.

In a meta-analysis, Classen et al. (2005) reviewed 90 studies related to revictimisation. A strong correlation was found between young women who were sexually abused in adolescence and subsequent adult sexual abuse victimisation (Classen et al., 2005). They also found at least 30 of the 90 studies indicated a strong correlation between child sexual abuse and subsequent adult sexual assault. The severity and type of abuse also correlated with revictimisation (Riser, Hetzel-Riggin, Thomsen, & McCanne, 2006). Severity is defined variously in studies, however the more intrusive the abuse, the greater the correlation with revictimisation (Classen et al., 2005). Classen et al. concluded that it is very difficult to separate the literature on risks, impacts and correlates of revictimisation. It should be noted that correlation and association are not causal factors and should be read as being related to revictimisation rather than directly causing revictimisation. Classen et al., Riser et al., Noll and Grych (2011), and Walsh et al. (2012) found that the following factors were related to revictimisation:

- child and adolescent sexual abuse - can lead to risky sexual behaviour, substance misuse, shame and dissociation related to post traumatic stress disorder;

- level of severity of previous abuse;

- a recent incident of victimisation;

- having a relationship with the perpetrator - intrafamilial sexual abuse was more closely associated with revictimisation than extrafamilial sexual abuse;

- cumulative past abuse, i.e physical and sexual abuse;

- family factors such as dysfunction and high levels of conflict;

- a (mal)adaptive risk response to dangerous situations;

- poor risk perception and emotional dysregulation (an impaired and poorly modulated emotional response);

- level of distress - particularly in relation to previous abuse.

A specific area of inquiry into individual risk factors is how the impacts of sexual abuse and assault can mediate revictimisation. Below is a brief summary of the literature that explores these factors.

Individual risk factors: Emotional dysregulation and risk perception

Particular attention has been paid to victim/survivors' emotional dysregulation and risk perception in creating vulnerability for sexual revictimisation. The literature on emotional dysregulation is instructive in that it highlights the importance of therapeutic support following an incident of sexual abuse or assault. For many victim/survivors one of the effects of abuse can be an inability to connect with or accept their own feelings (to become angry with themselves if they feel sad, for example). Noll and Grych (2011) stressed that an incomplete or "inadequate" response in the face of a dangerous situation that may lead to sexual revictimisation may stem from a biological dysregulation that can be traced back to child sexual abuse. In other words, a victim's ability to engage with an imminent threat is compromised because of an impaired cognitive response mechanism.

Walsh et al. (2012) explored the comparative risk perception between previously victimised and non-victimised participants and found that those who had been previously victimised had a reduced ability to leave "risky" social situations. Similarly, Volker et al. (2013) looked at factors that "put people at risk of repeated victimization" (p. 40). They found there was no significant difference in risk perception between the three groups being researched (non-victimised, single-incident victimisation, and revictimised); however, the revictimised group were more likely to wait longer before leaving a perceived risky situation than the single-victimised and non-victimised groups.

The intention of the above studies appears to be the identification of vulnerability within victim/survivors to revictimisation; however, it shifts almost imperceptibly towards victim-blaming and offers no immediate corrective to the risk or threat of revictimisation (Grauerholz, 2000; Wager, 2009).

Therefore, although these studies are of some interest to the field, it can be acknowledged that for certain populations of victim/survivors of trauma they are of limited use. This creates a tension as it maintains a focus on the prevention of sexual revictimisation as the responsibility of the victim/survivor and creates a risk avoidance paradigm; this tension is explored below.

The tension in identifying individual risk factors for sexual revictimisation

Identifying individual risk factors is an important facet of sexual revictimisation research. However, for many populations, these studies shift prevention strategies into risk avoidance strategies. The reason for this lies in the focus on the victim/survivor at the expense of looking more broadly, including at the surrounding contextual factors related to sexual revictimisation.

For example, for a person with a disability who may be physically unable to leave a risky situation, a focus on poor risk perception and individual risk factors more generally does not lessen the risk of revictimisation. This is particularly true if the person with a disability relies on others for physical support, or is housed in an institution (Murray & Powell, 2008). "They are silent, out of sight and out of mind. Worse still, these people remain at high risk of further sexual assault and abuse" (Goodfellow & Camilleri, 2003, p. 7).

Similarly, for Indigenous women who are geographically isolated in remote regions of Australia, the ability to leave a risky situation is mediated by the knowledge that the perpetrators (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) reside within the community and can access the victim any time (Keel, 2004). Research by Edie Carter (as cited in Keel, 2004) reveals that Indigenous women have high rates of sexual assault, multiple perpetrator assaults and sexual assaults that continue over time. Coupled with this is an intergenerational element to the violence and abuse that risks normalising sexual violence (Keel, 2004). These issues of vulnerability and risk are embedded within communities and social groups, making them difficult to walk away from.

The ability of victim/survivors to leave a risky situation may not be dependent on their perceived assessment of risk but rather on their understanding of the tactics used by perpetrators to isolate and disempower them using social norms (Clark & Quadara, 2010). This issue is discussed in the following section.

Relationship/interpersonal factors: Perpetrators

An important aspect of revictimisation is the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator, as well as the specific strategies and steps perpetrators use to take advantage of previously victimised individuals. Forensic Interview Advisor with Victoria Police Patrick Tidmarsh states "It's so important for people to understand the relationship and the context in which the abusive behaviour takes place" (Tidmarsh, 2012, "What are some of the challenges". para. 1).

For non-familial relationships, Clark and Quadara (2010) brought some clarity to understanding how perpetrators choose vulnerable individuals. It is a highly social process and relies on the perpetrator taking advantage of trust, and exploiting the social scripts related to sexual seduction. Clark and Quadara noted that perpetrators "made deliberate choices and enacted situationally targeted strategies to secure sexual interaction with the victim/survivor" (p. 53). Their research includes one story in which a victim of sexual violence who had spoken publically about the details of her assault was manipulated into a vulnerable situation by a perpetrator who "used the same method of overpowering me as I'd described in my speech" (Dana, as quoted in Clark & Quadara, 2010, p. 23).

Gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals and communities have historically had a difficult relationship with social acceptance within a majority heterosexual society. This tension and lack of acceptance can manifest at the individual level as hate crimes. "Individuals (and communities of people) who challenge the dominant norms around sex, gender, and sexuality can face significant levels of violence and abuse of both a physical and sexual nature" (Fileborn, 2012, p. 3). The fear of not being socially accepted may keep gay, lesbian, trans, bisexual, intersex and queer (GLTBIQ) individuals in unsafe relationships where intimate partner sexual violence is a feature. Fileborn's review of the literature on sexual violence against those in the GLBTIQ community suggests that sexual assaults can be homophobic in nature.

Beyond the interaction between the perpetrator and the victim/survivor, this social sphere also includes consideration of a support system that the victim/survivor may draw from following their revictimisation. Victim/survivors of sexual violence demonstrate lower levels of trauma and harm following an assault if they are able to access strong support networks such as family and friends to help them process the trauma (Boyd, 2011).

These examples, which consider vulnerable populations, illustrate the importance of taking a wider view when considering where risk of sexual revictimisation is situated. Questions related to the types of initiatives to be undertaken for the prevention of sexual revictimisation can cast a wider net to include perpetrators that target those with a history of sexual violence and vulnerability (Noll, 2005). Of course, perpetrators and their victims live within a broader community context that influences their interactions. This social sphere is explored in the following section.

Community/organisational factors: Microsystems

The next level in the socio-ecological model is the microsystem, or the community and organisational sphere of life. To understand how community and organisational factors may contribute to sexual revictimisation, Grauerholz (2000) reminds us to be concerned with "how social power is derived and how one's (lack of) social power contributes to vulnerability" (pp. 12-13). Apart from factors such as socio-economic position, gender, disability, ethnicity, class and sexuality having an influence on social power, so too does a history of victimisation. This can translate into how a victim/survivor experiences his/her relationships with the broader community and organisations with which they engage (Grauerholz, 2000).

Organisational policies and procedures and the communities within which they are embedded can shape how support is provided to victim/survivors of sexual violence and sexual revictimisation (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2010).

Community attitudes

The attitudes and beliefs of people within communities can also be instrumental in supporting or removing support for the resources that perpetrators use to target vulnerable people. These attitudes and beliefs can include perceptions related to alcohol and/or drug use, how often women falsify claims of violence by a partner, how likely people are to intervene in domestic violence incidences and belief in gender equity (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2010). The National Survey on Community Attitudes to Violence Against Women (2010) found that 16% of women and 16% of men believed that "if a woman is raped while she is drunk or affected by drugs she is at least partly responsible" for her rape (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2010, p. 41). This attitude indicates a victim-blaming stance towards rape victim/survivors that can also be considered a supportive attitude towards sexual assault perpetration - giving justification to sexual violence due to a victim's intoxication. Overall, community attitudes toward sexual violence are improving, but the above statistics demonstrate that negative views about sexual abuse survivors are still present in sections of our population.

Organisational policies: The police

This section briefly considers how an organisation, such as the police force, may affect sexual revictimisation. Indeed other organisations may also effect revictimisation and the police force is merely being used as one example here. There is research which also looks at how the criminal justice system more broadly may include bias in decision-making processes that ultimately disadvantages sexual assault victims, including prosecutorial decision-making (see Kelly, 2010; Lievore, 2004). There exists a large body of literature on sexual assault that considers barriers to disclosure of sexual violence for victim/survivors (see Allimant & Ostapiej-Piatkowski, 2011; Foster, Boyd, & O'Leary, 2012; Quadara, 2008). Due to longstanding cultural myths surrounding sexual assault, many victim/survivors do not report their assault to police (Fileborn, 2012; Foster et al., 2012; Jordan, 2004). Victim/survivors may fear being disbelieved by the police, having their private lives exposed, being blamed for the assault and might not even feel the assault warrants police time. As the police are an important avenue of justice for victims of crime as well as an important social institution, there is some urgency in ensuring police responses to victim/survivors of sexual revictimisation reflects victim/survivors' needs.

There is research to suggest that police have increased both their understanding and their support of rape victim/survivors in recent years; however, as Jordan (2004) demonstrates in her research, this has not always been the case.

Jordan (2004) conducted research into police decision-making in relation to rape victim/survivors. The research demonstrates that a majority of women who reported a sexual revictimisation were classified as "possibly true/possibly false" or "police said false". Jordan contended that these classifications were based on biased decision making rather than thorough police investigations. This means that police were making various decisions about the integrity of the victim/survivor and how believable their report was based on their own views of how a victim/survivor of assault should act. Additionally, police may consider a report as "possibly true/possibly false" if there is insufficient evidence (Jordan, 2004). Insufficient evidence has always been an unfortunate hallmark of sexual assault cases. Considering the nature of the assault (usually only the perpetrator and the victim are present), it does not mean an assault did not take place or is being falsely reported (Wall & Tarczon, 2013).

Jordan's study also demonstrates why data on sexual revictimisation are so patchy. If police in the study considered sexual revictimisation as a dubious and unlikely possibility, then the concept of sexual revictimisation is not well understood nor given adequate legitimacy. This affects the collection of data, which, in turn, can have an effect on research efforts.

A study on police investigations and the outcomes of rapes reported to Victoria Police found that police brought forward charges on only 15% of the cases reported to them in a three-year period (Heenan & Murray, 2006, as cited in Morrison, 2008). In the same three-year period, 26% of the cases included a victim/survivor who had mental health issues. These cases were twice as likely to be labelled as false allegations by police. This echoes Jordan's work and indicates a significant bias against people with mental health issues or cognitive disabilities who report sexual revictimisation.

These examples are indicative of community conditions that foster a lack of support for people who are sexually revictimised. Findings such as these illustrate Grauerholz's theory that contextual factors are important factors in sexual revictimisation and a site for the identification of risk factors beyond the individual. It is also at this level of the socio-ecological model that education campaigns and community-based programs can support respectful relationships and gender equality principles, which are considered important in reducing violence against women more broadly (Council of Australian Governments, 2011). Taking an even wider view, societal factors can also play a part in sexual revictimisation, and how this might occur is explored in the section below.

Societal factors contributing to sexual revictimisation: The broader view

The broadest sphere of the socio-ecological model is the social sphere encompassing social and cultural processes, beliefs, systems and structures. "To fully understand the process of revictimisation or any gender/family violence, one needs to take into account the larger cultural context in which the individual, her relationships, and the community are embedded" (Grauerholz, 2000, p. 14). The National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and Their Children identifies broader cultural beliefs and attitudes related to sexual violence that require change in order to reduce violence against women (Council of Australian Governments, 2011). The cultural belief that victim/survivors are somehow responsible for their abuse is a relevant factor in victim/survivors not disclosing incidents of sexual abuse due to, for instance feelings of shame, and this, in turn, increases the risk of sexual revictimisation (Grauerholz, 2000; Wall, 2012).

For more vulnerable communities, the broader social context can have an even greater immediate effect. Due to a history of colonisation, displacement and disenfranchisement, Indigenous people have been reluctant to report instances of sexual victimisation and sexual revictimisation to authorities, preferring to disclose to family and community members (Australian Institute of Criminology, 2011). This has resulted in very little data being generated regarding prevalence, revictimisation and help seeking mechanisms utilised in Indigenous communities. This is particularly true of remote communities that experience wide-ranging disadvantage and require quite complex system responses (Bath, 2013). Although rates of sexual victimisation are high, many Indigenous communities would rather see offenders offered an avenue to heal, than to be imprisoned. How non-Indigenous Australian society addresses sexual revictimisation may not fit for Indigenous communities (Keel, 2004). It is therefore important to acknowledge and address how wider Australian society affects rates of sexual revictimisation in Indigenous communities and how it can support Indigenous communities to reduce rates of sexual revictimisation.

Other social factors related to sexual revictimisation for vulnerable or minority populations include the beliefs that:

- sexual violence doesn't occur in same-sex relationships;

- sexual violence is rare;

- women often falsely report rape;

- sexual revictimisation is just a part of Indigenous culture;

- men can't be raped; and

- women are complicit in their sexual revictimisation (Duncanson, 2013; Fileborn, 2012; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2010; Wall & Tarczon, 2013).

When considering the factors that underlie sexual revictimisation, a broader view looking outward from the individual, encompassing their relationships, their communities and the broader cultural landscape may be a more effective and holistic approach to understanding sexual revictimisation (Grauerholz, 2000). It is also at this level of the socio-ecological model that prevention strategies for revictimisation can be given a broader focus in a similar way to prevention strategies for violence against women (see Council of Australian Governments, 2011; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2007).

Conclusion

The available literature on sexual revictimisation reveals a focus on how individual victim/survivors of child sexual abuse and/or adolescent sexual abuse "are at considerable risk for subsequent victimisation whereas others successfully avoid it" (Noll, 2005, p. 458). Yet ways to "avoid" sexual revictimisation seem to target only the victim/survivor. Of course, the individual must do all they can to decrease the risk of further victimisation, and the literature concerning sexual revictimisation reveals that risk perception and emotional dysregulation exhibited by victim/survivors of sexual violence are a focus for intervention. This indicates a need to provide therapeutic services and interventions to all victim/survivors of sexual violence in an effort to treat trauma and traumatic symptoms so they are not a mediating factor in further victimisation.

For minority groups who are more vulnerable to sexual revictimisation due to their disability, sexuality or because they are Indigenous, greater advocacy, research and supports are required in order that these groups do not remain under-researched, and that evidence-based interventions can reduce the rates of sexual revictimisation among these groups. However, it cannot be ignored that much of the literature on the risks for sexual revictimisation, in focusing on the individual risk factors, tend to ignore the broader social context.

Using the work of Grauerholz (2000), this research summary presents a more holistic view of the supports for sexual revictimisation through use of the socio-ecological model. The socio-ecological model for sexual revictimisation demonstrates sites of risk beyond the individual, such as perpetrators who target vulnerable people, community attitudes that blame rape victims, and social systems that have disenfranchised minority groups from their own culture.

Knowing the contextual factors related to sexual revictimisation, we can focus on prevention strategies that address them, such as respectful relationship education, gender equality principles and a focus on important sites of social norm reproduction, such as sporting sites and the media, to convey messages of respect and equality (Council of Australian Governments, 2011; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2007). These strategies currently make up primary prevention efforts for sexual and physical violence against women more generally. Situating risk in the socio-ecological model allows for a more holistic view of risk. It points us in the right direction for increasing our understanding of the prevalence of sexual revictimisation and beginning the work of strategising towards possible prevention models for sexual revictimisation.

References

- Allimant, A., & Ostapiej-Piatkowski, B. (2011). Supporting women from CALD backgrounds who are victim/survivors of sexual violence: Challenges and opportunities for practitioners (ACSSA Wrap). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/wrap/wrap9/index.html>.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Recorded crime: Victims, Australia, 2011. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Institute of Criminology. (2011). Non-disclosure of violence in Australian Indigenous communities. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2012). Child protection Australia 2010-2011 (Child Welfare Series No. 53, Cat No. CWS 41). Canberra: AIHW.

- Australian Law Reform Commission. (2014). Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws (ALRC Report 31) Sydney: ALRC. Retrieved from <www.alrc.gov.au/publications/3. Aboriginal Societies%3A The Experience of Contact/impacts-settlement-aboriginal-people>.

- Bath, H. (2013). After the Intervention: The ongoing challenge of ensuring the safety and wellbeing of vulnerable children in the Northern Territory. Paper presented at the Child Family Community Australia webinar/seminar, Melbourne. Retreived from <www.aifs.gov.au/cfca/events/bath/index.html>.

- Boyd, C. (2011). The impacts of sexual assault on women (ACSSA Resource Sheet No. 2). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/sheets/rs2/index.html>.

- Chiu, G. R., Lutfey, K. E., Litman, H. J., Link, C. L., Hall, S. A., & McKinlay, J. B. (2013). Prevalence and overlap of childhood and adult physical, sexual, and emotional abuse: A descriptive analysis of results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Violence and Victims, 28(3), 381-402.

- Clark, H., & Quadara, A. (2010). Insights into sexual assault perpetration: Giving voice to victim/survivors' knowledge (Research Report No. 18). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/resreport18/index.html>

- Classen, C. C., Palesh, O. G., & Aggarwal, R. (2005). Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 6(2), 103-129.

- Council of Australian Governments. (2011). National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and Their Children 2010-2022. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Desai, S., Arias, I., Thompson, M. P., & Basile, K. C. (2002). Childhood victimization and subsequent adult revictimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of women and men. Violence and Victims, 17(6), 639-653.

- Duncanson, K. (2013). Community beliefs and misconceptions about male sexual assault (ACSSA Resource Sheet No. 7). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/sheets/rs7/index.html>.

- Fileborn, B. (2012). Sexual violence and gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer communities (ACSSA Resource Sheet No. 3). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/sheets/rs3/index.html>.

- Foster, G., Boyd, C., & O'Leary, P. (2012). Improving policy and practice responses for men sexually abused in childhood (ACSSA Wrap). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/wrap/wrap12/index.html>.

- Goodfellow, J., & Camilleri, M. (2003). Beyond belief, beyond justice: The difficulties for victim/survivors with disabilities when reporting sexual assault and seeking justice. Final report of the Sexual Offences Project, stage one. Footscray, Vic.: Disability Discrimination Legal Service.

- Grauerholz, L. (2000). An ecological approach to understanding sexual revictimization: Linking personal, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors and processes. Child Maltreatment, 5(1), 5-17.

- Heidt, J. M., Marx, B. P., & Gold, S. D. (2005). Sexual revictimization among sexual minorities: A preliminary study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 533-540.

- Hequembourg, A. L., Livingston, J. A., & Parks, K. A. (2013). Sexual victimization and associated risks among lesbian and bisexual women. Violence Against Women, 19(5), 634-657.

- Higgins, D., & Price-Robertson, R. (2011). What's the use of the "multi-type maltreatment" and "polyvictimization" concepts? International comparisons of key issues, predictors, prevalence and impact on wellbeing (PDF 704 KB). Paper presented at the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (APSAC), Philadephia. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/papers/2011/higginspricerobertson.pdf>.

- Higgins, D. J., & McCabe, M. P. (2003). Maltreatment and family dysfunction in childhood and the subsequent adjustment of children and adults. Journal of Family Violence, 18(2), 107-120.

- Jordan, J. (2004). Beyond belief?: Police, rape and women's credibility. Criminal Justice, 4(1), 29-59.

- Keel, M. (2004). Family violence and sexual assault in Indigenous communities: "Walk the talk" (ACSSA Briefing No. 4).Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Kelly, L. (2010). The (in)credible words of women: False allegations in European rape research. Violence Against Women, 16(12), 1345-1355

- Lievore, D. (2004). Victim credibility in adult sexual assault cases (Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No. 288). Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Ministry of Women's Affairs. (2012). Lightning does strike twice: preventing sexual revictimisation. Wellington: Ministry of Women's Affairs.

- Morrison, Z. (2008). What is the outcome of reporting rape to police? ACSSA Newsletter, 17, 4-11. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/newsletter/n17.html#What>.

- Murray, S., & Powell, A. (2008). Sexual assault and adults with a disability; Enabling recognition, disclosure and a just response (ACSSA Issues paper). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/issue/i9.html>.

- Noll, J. G. (2005). Does childhood sexual abuse set in motion a cycle of violence against women? What we know and what we need to learn. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(4), 455-462.

- Noll, J. G., & Grych, J. H. (2011). Read-react-respond: An integrative model for understanding sexual revictimization. Psychology of Violence, 1(3), 202-215.

- Ogloff, J. R. P., Cutuajar, M. C., Mann, E., & Mullen, P. (2012). Child sexual abuse and subsequent offending and victimisation: A 45 year follow-up study (Trends & Issues in Crime & Criminal Justice No. 440). Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Quadara, A. (2008). Responding to young people disclosing sexual assault: A resource for schools (ACSSA Wrap). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/wrap/w6.html>.

- Quadara, A., & Wall, L. (2012). What is effective primary prevention in sexual assault? Translating the evidence for action (ACSSA Wrap No. 11). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/wrap/wrap11/index.html>.

- Riser, H. J., Hetzel-Riggin, M. D., Thomsen, C. J., & McCanne, T. R. (2006). PTSD as a mediator of sexual revictimization: The role of rexperiencing, avoidance and arousal symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(5), 687-698.

- Tidmarsh, P. (2012). Working with sexual assault investigations (Sexual Offences Child Abuse Investigation Team) (Interviewed by M. Stathopoulos) (ACSSA Working With). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/workingwith/investigations.html>.

- Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. (2007). Preventing violence before it occurs: A framework and background paper to guide the primary prevention of violence against women in Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation.

- Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. (2010). National Survey on Community Attitudes to Violence Against Women 2009: Changing cultures, changing attitudes. Preventing violence against women: A summary of findings. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation.

- Volker, J., Randjbar, S., Moritz, S., & Jelinek, L. (2013). Risk recognition and sensation seeking in revictimization and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Modification, 37(1), 39-61.

- Wager, N. (2009). Sexual revictimisation: A critical review of the theoretical pathways from childhood sexual abuse to adult sexual assault (Stage 1: Diploma of Forensic Psychology). NP: academia.edu. Retrieved from <www.academia.edu/675184/Theoretical_Explanations_for_Sexual_Revictimisation>.

- Wall, L. (2012). The many facets of shame in intimate partner sexual violence(ACSSA Research Summary No. 1). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/researchsummary/ressum1/index.html>.

- Wall, L., & Tarczon, C. (2013). True or false? The contested terrain of false allegations (ACSSA Research Summary No. 4). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/acssa/pubs/researchsummary/ressum4/rs4a.html>.

- Walsh, K., DiLillo, D., & Messman-Moore, T. L. (2012). Lifetime sexual victimization and poor risk perception: Does emotional dysregulation account for the links? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(15), 3054-3071.

At the time of writing Mary Stathopoulos was a Senior Research Officer with ACSSA at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The author would like to thank AIFS staff, particularly Daryl Higgins and Antonia Quadara for their guidance and feedback throughout the production of this publication.

Stathopoulos, M. (2014). Sexual revictimisation: Individual, interpersonal and contextual factors (ACSSA Research Summary). Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-922038-47-0