Mental health literacy and interventions for school-aged children

December 2022

Alexandra Marinucci, Christine Grove, Pragya Gartoulla

Introduction

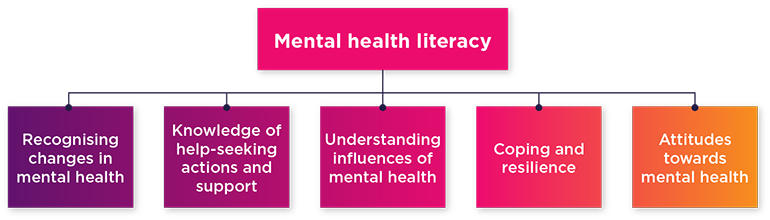

There is some evidence that Australian youth are increasingly facing mental health challenges, with the rate of psychological distress experienced by youth rising from 18.6% in 2012 to 26.6% in 2020 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2021; Brennan et al., 2021). However, despite young people’s need for support, there are barriers to them accessing the appropriate supports. These include a lack of awareness of mental health issues or how to seek help, as well as negative attitudes towards mental illness (Marinucci, Grové, & Rozendorn, 2022; Radez, 2020; Radez, 2021; Teng, Crabb, Winefield, & Venning, 2017). There is evidence to suggest young people are less likely to seek help than adults (Rickwood, Deane, & Wilson, 2007), and that willingness to seek help decreases during the adolescent years (Warren & Daraganova, 2017). Therefore, there is increasing emphasis on the need for preventative and proactive approaches such as school-based mental health literacy interventions (Jorm, 2020). Mental health literacy is the understanding of mental health, including knowing how to maintain good mental health and address poor mental health (Bale, Grové, & Costello, 2020; Jorm, 2020; Kutcher et al., 2016) (see Figure 1). This short article discusses how practitioners can incorporate mental health literacy interventions into the school environment.

Figure 1. Components of mental health literacy interventions

Source: Bale et al. (2020)

The need for mental health literacy interventions

Mental health literacy is different to mental health first aid. Mental health first aid is ‘help provided to a person who is developing a mental health problem or who is in a mental health crisis, until appropriate professional help is received or the crisis resolves’ (Morgan, Ross, & Reavley, 2018, p. 2). In contrast, mental health literacy is knowledge and holistic understanding of mental health to obtain good mental health and develop positive coping behaviours. The literature on school-based mental health literacy interventions notes interventions aimed at:

- understanding symptoms of mental illness

- appropriate coping skills

- caring for one’s mental health

- helping others experiencing mental ill-health

- understanding help-seeking options

- understanding the effects of mental illness stigma

(Bale et al., 2020; Marinucci, Grové, & Allen, 2022).

The Youth Education and Support Program (Marinucci, Grové, Allen, & Riebschleger, 2021; Riebschleger, Costello, Cavanaugh, & Grové, 2019) is an example of a school-based mental health literacy program.

Mental health literacy can be cultivated and grown over time, with skills able to be applied individually and to help others. Offering mental health literacy interventions in groups; that is, at a class or year level, provides accurate information to many young people (rather than one at one time) who may struggle to find good information online or who may be on long waiting lists to access professional help. Group-based programs have the potential to be a more cost-effective way to provide mental health information and support versus individual intervention. Normalising help-seeking for mental health problems to reduce stigma surrounding mental health could also be achieved through group programs (Marinucci, Grové, & Rozendorn, 2022; Patafio, Miller, Baldwin, Taylor, & Hyder, 2021; Seedaket, Turnbull, Phajan, & Wanchai, 2020).

Mental illness often develops during late childhood to adolescence (Solmi et al., 2021) and this affects areas such as education, achievement, relationships and occupational success (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). Consequently, there is a need for children and youth to receive information about mental health in their learning environment. Evidence suggests that young people experiencing mental illness want school staff and students to be educated and better informed about mental health to help reduce stigma and increase appropriate help-seeking actions in the school setting (Kostenius, Gabrielsson, & Lindgren, 2020). Mental health and learning cannot be separated, and school is a place where young people can learn about mental health.

Mental health literacy interventions have the potential to create a safe platform for learning about mental health and to connect young people with necessary support (Kelly, Jorm, & Wright, 2007; WHO, 2021). The interventions could be incorporated at the Tier 1 level of support to promote positive mental health and wellbeing at a universal scale. More targeted approaches may be necessary to provide additional support at particular points throughout the school journey; for example, transitioning from primary to secondary school. Although this article does not focus on mental health during times of community crisis such as bushfires, specific support at these times may also be needed.

The current evidence on mental health literacy interventions

Awareness of the value of mental health literacy is growing in educational settings; however, more research is required to develop a sound evidence base to benefit student wellbeing (Patafio, 2021; Seedaket, 2020). Current evidence on school-based mental health literacy interventions have multiple methodological limitations, raising concerns over the quality of studies and feasibility of interventions under real world conditions (Cilar, Štiglic, Kmetec, Barr, & Pajnkihar, 2020; O'Connor, Dyson, Cowdell, & Watson, 2018; Wei, Hayden, Kutcher, Zygmunt, & McGrath, 2013). Despite this, emerging evidence is showing that programs targeting mental health literacy with a focus on coping and help seeking can be effective (Marinucci, Grové, & Allen, 2022; Riebschleger, Costello, Cavanaugh, & Grové, 2019). For example, an evaluation of the Youth Education and Support program found participants had improved coping and mental health knowledge following completion of the program (Riebschleger et al., 2019).

The evidence suggests that interventions should be multi-modal to increase engagement and address the learning needs of all youth. Young people report that they want mental health literacy information throughout their schooling years, and this should be continually taught and built on with a scaffolding approach (Marinucci, Grové, & Rozendorn, 2022). Health care professionals working in a school environment can implement or support these interventions at the beginning and during uptake to ensure interventions are addressing student needs.

What are the implications for practice?

Education settings allow access to large populations of youth within an established learning environment (Lanfredi et al., 2019; Milin et al., 2016). Mental health and wellbeing are a priority for most schools (Allen, Kern, Vella-Brodrick, & Waters, 2018) and developing mental health literacy could be supported by professionals, such as trained counsellors or psychologists already working within an educational setting. Professionals with experience, training and knowledge in youth mental health, and who are based in school settings, are best equipped to deliver mental health literacy interventions. These practitioners are aware of how a school environment functions and may be able to incorporate mental health literacy interventions into supporting student mental health.

The research evidence suggests the following strategies can be used to help increase mental health literacy for young people:

- using different types of evidence-based interventions; for example, group programs, educational lectures, activities based on principles of therapeutic techniques such as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (Hernandez, & Hodges, 2006; Marinucci et al., 2021)

- ongoing assessment of student mental health needs and including them in tailored interventions to suit their needs; for example, using a youth advisory board within the school, questionnaires measuring student wellbeing (National Association of School Psychologists, 2021)

- experienced professionals training teachers in understanding youth mental health and providing support in implementing evidence-based interventions (Shernoff et al., 2016)

- increasing awareness of mental health in the school environment; for example, by supporting a positive classroom climate, responding with empathy to student concerns and discussing help-seeking options with students (Marinucci, Grové, & Rozendorn, 2022)

- advocating for schoolwide preventative approaches to address student mental health literacy needs, such as interventions delivered across year levels, mental health awareness activities tailored to student age (Hage, 2007)

- reducing stigma towards mental illness and help seeking by offering accessible psychological services in the education environment by health care professionals (Meyers, & Swerdlik, 2003; Oyen, Eklund, & von der Embse, 2020)

- professionals collaborating with teachers, principals, parents and students in ensuring mental health literacy interventions are adequate and appropriate.

Conclusion

The prevalence of psychological distress amongst our youth population is high and possibly increasing, with young people wanting more mental health information provided at school (Marinucci, Grové, & Rozendorn, 2022). Interventions to address mental health literacy need to be engaging and provide practical tools to build competencies in maintaining good mental health. The move to a preventative approach to mental illness requires a change in focus from reactive to proactive interventions. One such strategy involves incorporating mental health literacy interventions into the school environment, which can address children’s mental health needs early in their development.

Further reading and related resources

The resources below provide more information about mental health literacy and ways that mental health literacy interventions can be implemented.

- A Scoping Review and Analysis of Mental Health Literacy Interventions for Children and Youth

The paper this resource is based on. - Child mental health literacy: What is it and why is it important?

An overview of child mental health literacy from Emerging Minds. - Developing A Mental Health Literacy Model And Measurement Scale For Children

A child-focused mental health literacy model. - Building Better Schools with Evidence-based Policy

A free book available outlining various school-based policies for building better schools. - Strategies To Support Young People To Manage Stress At School

A resource developed by headspace with strategies to support youth experiencing stress at school. - Coping Strategies

KidsHelpline developed this resource outlining some coping strategies for teens. - 6 Ways to Help a Friend with Depression or Anxiety

A resource for youth developed by ReachOut with ideas of how to help a friend experiencing depression or anxiety. - Reducing Stigma

Developed by SANE Australia, a resource discussing what stigma is and how we can reduce it. - BeYou Program Directory

Beyond Blue’s searchable database of mental health and wellbeing programs for educational settings.

How was this resource developed?

This resource was developed based on a scoping review of school-based mental health literacy programs (Marinucci, Grové, & Allen, 2022). Six electronic databases were searched to determine the current literature evaluating mental health literacy interventions for children and adolescents in a school environment. These excluded interventions focusing on suicide prevention and mental health first aid as these focus on crisis specific interventions. A total of 27 studies were included in the review.

References

- Allen, K.-A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2018). Understanding the priorities of Australian secondary schools through an analysis of their mission and vision statements. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(2), 249–274. doi.org/10.1177/0013161X18758655

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2021). Australia’s youth: In brief. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/70b59dde-b494-48a7-ab51-f0cab369904f/Australia-s-Young-people-in-brief.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- Bale, J., Grové, C., & Costello, S. (2020). Building a mental health literacy model and verbal scale for children: Results of a Delphi study. Children and Youth Services Review, 109, 104–667. doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104667

- Brennan, N., Beames, J. R., Kos, J. R., Reily, N., Connell, C., Hall, S. et al. (2021). Psychological distress in young people in Australia: Fifth biennial youth mental health report. 2012–2020. Mission Australia.

- Cilar, L., Štiglic, G., Kmetec, S., Barr, O., & Pajnkihar, M. (2020). Effectiveness of school-based mental well-being interventions among adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(8), 2023–2045. doi.org/10.1111/jan.14408

- Hage, S. M., Romano, J. L., Conyne, R. K., Kenny, M., Matthews, C., Schwartz, J. P. et al. (2007). Best practice guidelines on prevention practice, research, training, and social advocacy for psychologists. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(4), 493–566. doi.org/10.1177/0011000006291411

- Hernandez, M., & Hodges, S. (2006). Applying a theory of change approach to interagency planning in child mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38(3–4), 183–190. doi.org/10.1007/s10464-006-9079-7

- Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67(3), 231–243. doi.org/10.1037/a0025957

- Jorm, A. F. (2020). We need to move from ‘mental health literacy’ to ‘mental health action’. Mental Health & Prevention, 18. doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2020.200179

- Kelly, C. M., Jorm, A. F., & Wright, A. (2007). Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. Medical Journal of Australia, 187(S7), S26–S30. doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01332.x

- Kostenius, C., Gabrielsson, S. & Lindgren, E. (2020). Promoting mental health in school: Young people from Scotland and Sweden sharing their perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 1521–1535. doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00202-1

- Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., Costa, S., GusmГЈo, R., Skokauskas, N., & Sourander, A. (2016). Enhancing mental health literacy in young people. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(6), 567. doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0867-9

- Lanfredi, M., Macis, A., Ferrari, C., Rillosi, L., Ughi, E., Fanetti, A. et al. (2019). Effects of education and social contact on mental health-related stigma among high-school students. Psychiatry Research, 281, 112–581. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112581

- Marinucci, A., Grové, C., & Allen, K.-A. (2022). A scoping review and analysis of mental health literacy interventions for children and youth. School Psychology Review, 1-15. doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2018918

- Marinucci, A., Grové, C., Allen, K.-A., & Riebschleger, J. (2021). Evaluation of a youth mental health literacy and action program: Protocol for a cluster controlled trial. Mental Health & Prevention, 24, 200216. doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2021.200216

- Marinucci, A., Grové, C., & Rozendorn, G. (2022). “It’s something that we all need to know”: Australian youth perspectives of mental health literacy and action in schools. Frontiers in Education, 7. doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.829578

- Meyers, A. B., & Swerdlik, M. E. (2003). School-based health centers: Opportunities and challenges for school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 40(3), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10085

- Milin, R., Kutcher, S., Lewis, S. P., Walker, S., Wei, Y., Ferrill, N. et al. (2016). Impact of a mental health curriculum on knowledge and stigma among high school students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(5), 383–391. doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.02.018

- Morgan A. J., Ross A., & Reavley N. J. (2018). Systematic review and meta-analysis of Mental Health First Aid training: Effects on knowledge, stigma, and helping behaviour. PLoS ONE, 13(5), e0197102. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197102

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2021). Who are school psychologists? Bethesda, MY: NASP. Retrieved from www.nasponline.org/about-school-psychology/who-are-school-psychologists

- O'Connor, C. A., Dyson, J., Cowdell, F., & Watson, R. (2018). Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(3–4), 412–426. doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14078

- Oyen, K. A., Eklund, K., & von der Embse, N. (2020). The landscape of advocacy in public schools: The role of school psychologists. Psychological Services, 17(S1), 81–85. doi.org/10.1037/ser0000373

- Patafio, B., Miller, P., Baldwin, R., Taylor, N., & Hyder, S. (2021). A systematic mapping review of interventions to improve adolescent mental health literacy, attitudes and behaviours. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. doi.org/10.1111/eip.13109

- Radez, J., Reardon, T., Creswell, C., Lawrence, P. J., Evdoka-Burton, G., & Waite, P. (2020). Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4

- Radez, J., Reardon, T., Creswell, C., Orchard, F., & Waite, P. (2021). Adolescents’ perceived barriers and facilitators to seeking and accessing professional help for anxiety and depressive disorders: A qualitative interview study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01707-0

- Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems?. Medical Journal of Australia, 187(S7), S35–S39. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01334.x

- Riebschleger, J., Costello, S., Cavanaugh, D. L., & Grové, C. (2019). Mental health literacy of youth that have a family member with a mental illness: Outcomes from a new program and scale. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 2. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00002

- Seedaket, S., Turnbull, N., Phajan, T., & Wanchai, A. (2020). Improving mental health literacy in adolescents: Systematic review of supporting intervention studies. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 25(9), 1055–1064. doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13449

- Shernoff, E. S., Frazier, S. L., Marinez-Lora, A. M., Lakind, D., Atkins, M. S., Jakobsons, L., et al. (2016). Expanding the role of school psychologists to support early career teachers: A mixed-method study. School Psychology Review, 45(2), 226–249. doi.org/10.17105/SPR45-2.226-249

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G. et al. (2021). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry. doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

- Teng, E., Crabb, S., Winefield, H., & Venning, A. (2017). Crying wolf? Australian adolescents’ perceptions of the ambiguity of visible indicators of mental health and authenticity of mental illness. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(2), 171–199. doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2017.1282566

- Warren, D., & Daraganova, G. (Eds.). (2017). Growing Up In Australia – The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Annual Statistical Report. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from growingupinaustralia.gov.au/research-findings/annual-statistical-report-2017

- Wei, Y., Hayden, J. A., Kutcher, S., Zygmunt, A., & McGrath, P. (2013). The effectiveness of school mental health literacy programs to address knowledge, attitudes and help seeking among youth. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 7(2), 109–121. doi.org/10.1111/eip.12010

- World Health Organization. (2021). Adolescent mental health. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved from www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

Alexandra Marinucci is Psychologist and PhD Candidate in the School of Educational Psychology & Counselling, Faculty of Education, Monash University.

Dr Christine Grove is Educational & Developmental Psychologist, Fulbright Scholar and Adjunct Senior Lecturer at Monash University.

Dr Pragya Gartoulla is Research Fellow at the Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) information exchange at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

© GettyImages/SDI Productions