Supporting young people experiencing disadvantage to secure work

November 2022

Key messages

-

Young people who are not engaged in any education, training or paid employment by the age of 24 are most at risk of experiencing future long-term unemployment.

-

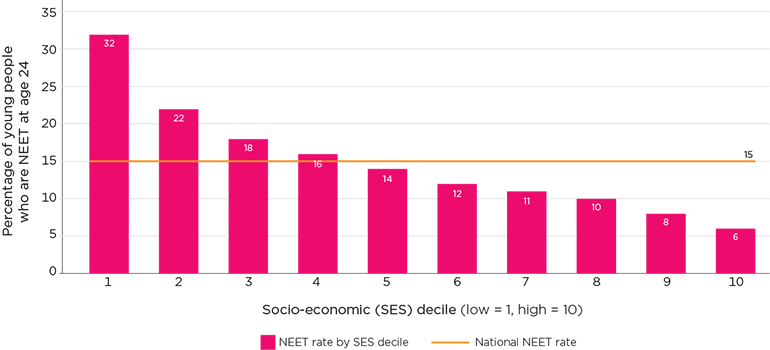

One in three Australians aged 24 and from the lowest socio-economic backgrounds are not in education, employment or training, compared to one in 15 from the highest socio-economic backgrounds.

-

Young people experiencing disadvantage may benefit from receiving multiple or complementary supports at the same time, including access to industry-specific and transferable skill development programs as well as more personalised supports.

-

Providing early intervention support while young people are still in school can promote work-based skills and knowledge before students encounter problems finding employment.

Introduction

Employment plays a key role in people’s financial security, ability to participate in society and overall wellbeing (Modini et al., 2016; Qian, Riseley, & Barraket, 2019). Young people experiencing disadvantage are more likely to experience repeated and long-term periods of unemployment, which can adversely affect their life course (Hart et al., 2020; Mawn et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2019; Stanwick, Forrest, & Skujins, 2017).

This short article provides an overview of the evidence on young people experiencing disadvantage and unemployment. It highlights strategies that may be useful for practitioners working in education and employment settings to support young people experiencing disadvantage to prepare for and find work.

What is the relationship between experiences of disadvantage and unemployment?

Recent government reports and research define disadvantage as a ‘lack of opportunities for social and economic participation’ (Productivity Commission, 2018, p. 23). Experiences of disadvantage include low income and poverty, a lack of resources to meet basic needs (often called ‘material deprivation’) and social exclusion (an inability to take part in the ordinary activities of a community) (Productivity Commission, 2018, p. 107; Saunders et al., 2018; Wood, Griffiths, & Emslie, 2019). These experiences can be multiple and cumulative and often combine with labour market conditions, such as economic recessions and industrial automation, and forms of discrimination to create further barriers to employment (Borland and Coelli, 2021; Hart et al., 2020; Productivity Commission, 2018; Saunders et al., 2018). For young people, experiencing disadvantage while living at home leads to a higher likelihood of future disadvantage and barriers to employment after becoming independent; this is referred to as the intergenerational experience of disadvantage (Lamb & Huo, 2017; Productivity Commission, 2018; Wood et al., 2019).

Experiences of disadvantage can create economic and social barriers to education, training pathways and employment, which increase young people’s risk of experiencing long-term exclusion from the workforce (Lamb et al., 2020; Productivity Commission, 2018). Experiences of disadvantage and unemployment are interrelated and mutually reinforcing; repeated and long-term periods of unemployment can also create and worsen experiences of disadvantage (Cassidy, Chan, Gao, & Penrose, 2020).

What do we know about unemployment for Australian young people experiencing disadvantage?

Most young people will experience transitory periods of unemployment without negative effects as they move between school or post-school training and enter the workforce (Lamb et al., 2020; The Smith Family, 2014). However, not all young people experience unemployment equally or in the same way. Young people experiencing disadvantage are more at risk of experiencing unemployment (Height, 2016; Lamb et al., 2020; Mawn et al., 2017; Stanwick et al., 2017; The Smith Family, 2014). They are also more likely to experience repeated and long-term unemployment, which can lead to persistent exclusion from the workforce, lower earnings, low motivation, loss of skills, financial stress, social exclusion and negative effects on mental and physical health (Atkins, Callis, Flatau, & Kaleveld, 2020; Hart et al., 2020; Kluve et al., 2017; Lamb & Huo, 2017; Lamb et al., 2020; Mawn et al., 2017; Modini et al., 2016; Stanwick et al., 2017).

Young people not in education, employment or training and experiencing disadvantage

The term ‘not in education, employment or training’ (NEET) refers to a young person who is neither engaged with any education or training nor in paid employment (Lamb et al., 2020; OECD, 2022; Productivity Commission, 2018). Young people’s engagement with the labour market is often measured by ‘NEET rates’ instead of unemployment rates because many young people will be temporarily unemployed while they pursue further education and training to secure future employment.1 Australian and international research suggests that young people who are not engaged in any education, training or paid employment by the age of 24 are most at risk of experiencing future long-term unemployment (Lamb et al., 2020; OECD, 2022).

Accessing consistent data on young people experiencing disadvantage and then exploring how this relates to unemployment can be difficult. ‘Experiences of disadvantage’ are defined and measured differently across sources, and data are often adult-centric and do not capture young people’s diverse experiences (Saunders et al., 2018). However, examining the relationship between measures that are more consistently defined, such as socio-economic status2 (a widely used proxy measure of disadvantage that indicates people's level of income, access to resources and ability to participate in society (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2016)) and the rates of young people who are not in education, employment or training can help identify which young people may need more support to access employment opportunities.

On average, by the age of 24, 15% of Australians are not in education, employment or training (Figure 1) (Lamb et al., 2020), which is consistent with other countries of similar economic development (Lamb et al., 2020; OECD, 2022). However, as Figure 1 highlights, population averages can obscure the large differences that exist between young people from high and low socio-economic backgrounds (Lamb et al., 2020). Around one in three Australians aged 24 from the lowest socio-economic background are not in education, employment or training, compared to one in 15 from the highest socio-economic background (Lamb et al., 2020). This indicates that low socio-economic status has a substantial effect on a young person’s opportunities to secure future employment.

Figure 1: National rates of Australian young people (N = 380,725) not in education, employment or training (NEET) at age 24 by socio-economic status (SES) decile.

Source: Australian Census of Population and Housing 2016 in Lamb et al. (2020). The relevant population was divided into deciles based on SES area measures, using the ABS SEIFA Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage.

Certain groups of young people are more likely to be recorded as both ‘not in education, employment or training’ and living in a low-income household (a measure and indicator of socio-economic disadvantage). There are data that show a higher percentage of young people living in remote postcodes are recorded as not in education, employment or training (38%) than young people living in major cities (13%) (Lamb et al., 2020). Households in rural and remote Australia are also more likely to be low-income (National Rural Health Alliance [NRHA], 2017).

Data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s experiences show that 45% were not recorded as being engaged in education, employment and training, compared to 14% for non-Indigenous young people (Lamb et al., 2020). Income data show Indigenous Australians are also more likely to live in low-income households (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2021).

This indicates that some young people are more likely to live in households experiencing at least one aspect of socio-economic disadvantage and may find it difficult to access further education, employment and training opportunities (Lamb et al., 2020). However, these data don’t capture all the experiences of disadvantage they may face, such as discrimination and social exclusion.

What works to support young people experiencing disadvantage to prepare for work?

Evidence shows that young people not in education, employment or training and experiencing disadvantage may benefit from multiple, personalised supports and early intervention while in school (Berger, Hanham, Stevens, & Holmes, 2019; Hart et al., 2020; Kluve et al., 2017; Mawn et al., 2017; Quian et al., 2019). This evidence also suggests the need for large-scale, structural solutions that consider broader economic and labour market conditions and the effects these have on young people’s employment opportunities (Kluve et al., 2017; Quian et al., 2019; Productivity Commission, 2018).

The research literature shows that there is a need for more consistent, high-quality evaluation of interventions to strengthen our understanding of their effectiveness (Apunyo et al., 2022; Kluve et al., 2017; Mawn et al., 2017). However, Australian and international research and service organisation reports (Atkins et al., 2020; Berger et al., 2019; Borland and Coelli, 2021; Brotherhood of St Laurence, 2018; Height, 2016; Lamb et al., 2020; Newton, Sinclair, Tyers, & Wilson, 2020; Qian et al., 2019) and systematic reviews (Hart, 2020; Kluve et al., 2017; Mawn et al., 2017) have identified strategies that practitioners working in education and employment settings can use to help young people experiencing disadvantage to prepare for or find work. These strategies are outlined below.

Multiple, complementary supports

Services to help young people find work can include training and skills development, further education, job search assistance, financial support and career counselling (Height, 2016; Kluve et al., 2017; Newton et al., 2020). The research evidence suggests that there isn’t one ‘specific combination’ of these services that works for all young people experiencing disadvantage to gain or better their employment (Kluve et al., 2016, p. 39). However, when multiple or complementary supports are provided together with a main service, young people’s employment outcomes tend to improve (Kluve et al., 2017; Newton et al., 2020; Mawn et al., 2017).

Providing support across multiple settings also leads to better employment outcomes for young people (Kluve at al., 2017). For example, practitioners can arrange or connect young people to skill development pathways that span education, work and training settings.

Work-based skill development

Supporting young people to access industry-specific and transferable skill development programs can improve employability and help young people engage with practical training pathways (Berger, et al., 2019; Hart et al., 2020; Kluve et al., 2017). Pathways can include higher education and literacy skills development, vocational education and training and apprenticeship or work experience programs (Height, 2016; Stanwick et al., 2017).

Practitioners may want to connect young people to skill development pathways that include soft skills such as communication, problem-solving and social skills, which can help build self-efficacy, job searching and interview skills, and other transferable workplace skills such as collaboration and critical thinking (Basharat, Bobadilla, Lord, Pakula, & Fowler, 2020; Height, 2016).

Targeted and personalised supports

Personalised employment supports that target young people’s specific social, cultural and economic experiences can lead to better employment outcomes and higher income (Kluve et al., 2017; Height, 2016; Newton et al., 2020; Qian et al., 2019). Targeted and personalised support often seeks to address the specific barriers young people experience (Atkins et al., 2020; Height, 2016; Kluve et al., 2017; Newton et al., 2020; Quian et al., 2019). For example, they may facilitate or provide access to technological (including internet), financial, language and literacy, or mental health supports (when needed), alongside general employment services (Atkins et al., 2020; Hart et al., 2020; Height, 2016; Newton et al., 2020).

Personalised advice and guidance provided on a one-to-one basis by a single consistent advisor can also empower young people to feel more confident in their job search and improve their motivation, self-efficacy and confidence (Newton et al., 2020).

Early intervention during school

For young people, low educational attainment including poor literacy skills is a risk factor for experiencing poor employment outcomes (Borland and Coelli, 2021; Kluve et al., 2017; Mawn et al., 2017; OECD, 2017). Young people experiencing disadvantage are more likely to have low attainment and engagement in education (Lamb et al., 2020), and are more likely to experience misalignment between their career aspirations and qualification levels (Berger et al., 2019; OCED, 2020).

Practitioners working with school-aged young people can provide career guidance to promote work-based skills and knowledge before students leave school and encounter problems finding employment (Height, 2016; Newton et al., 2020). Providing feedback on the alignment of young people’s preferred qualifications or skills and career aspirations can support their understanding of ways to engage with labour markets (Berger et al., 2019).

Supporting young people to gain foundational literacy and numeracy skills while in school is important as young people with very low literacy and numeracy skills are more likely to find it difficult to access and participate fully in further education, training and employment (Height, 2016; Lamb et al., 2020).

Practitioners may want to consider working with education and community organisations to identify young people experiencing disadvantage who are at risk of future unemployment (Height, 2016; OECD, 2017; Newton et al., 2020). For example, linking at-risk young people to the Transition to Work initiative – a government-funded service provided by community organisations that offers practical pre-employment support including skills building and job search assistance – may be helpful (Brotherhood of St Lawrence, 2018).

Conclusions

The research evidence shows an association between young people’s experiences of disadvantage and the risk of long-term unemployment. Data indicate that some groups of young people are more likely to experience disadvantage and be recorded as not in further education and training or employment (Lamb et al., 2020). The relationship between disadvantage and long-term unemployment is complex and has several structural causes, which makes it difficult to measure and address (Kluve et al., 2017; Productivity Commission, 2018). However, practitioners can provide meaningful support to young people experiencing disadvantage that will help them prepare for and find work. Evidence suggests there are benefits to providing multiple, complementary supports, including work-based skill development, and early intervention in schools (Berger et al., 2019; Hart et al., 2020; Kluve et al., 2017; Mawn et al., 2017; Newton et al., 2020; Quian et al., 2019). Identifying young people experiencing disadvantage who may need more support and personalising the advice and supports available to them can improve the effectiveness of services (Kluve et al., 2017; Newton et al., 2020; Qian et al, 2019).

Further reading and related resources

- Transition to Work

The Transition to Work initiative, by the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE), partners with education and training providers and local community services to support young people to find work. - I’m a young person: Work & study (headspace.org.au)

This webpage by headspace provides resources to support young people trying to find work and study. - List of Employment Services & Support

This webpage by headspace lists Australia-wide and state-based employment support services for young people. - Inclusive activation: New toolkit for professionals

This website by the European Social Network provides approaches and resources on how to support people experiencing disadvantage to feel included in the labour market. - Employment Empowers

A service provided by The Centre for Multicultural Youth that connects newly arrived young people from migrant or refugee backgrounds with volunteer mentors, who are able to support them to find work.

References

- Apunyo, R., White, H., Otike, C., Katairo, T., Puerto, S., Gardiner, D. et al. (2022). Interventions to increase youth employment: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18, e1216. doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1216

- Atkins, M., Callis, Z., Flatau, P., & Kaleveld, L. (2020). COVID-19 and youth unemployment: CSI response. Australia: Centre for Social Impact. Retrieved from www.csi.edu.au/media/uploads/csi_fact_sheet_social_covid-19_youth_unemployment.pdf

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016). Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA):Technical Paper. Retrieved from www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/756EE3DBEFA869EFCA2582590

00BA746/$File/SEIFA%202016%20Technical%20Paper.pdf - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2021). Indigenous income and finance. Canberra; AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-income-and-finance

- Basharat, S., Bobadilla, A., Lord, C., Pakula, B., & Fowler, H. S. (2020) Soft skills as a workforce development strategy for Opportunity youth: Review of the evidence. The Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC). Retrieved from www.srdc.org/media/553249/sel-evidence-review-oct2020.pdf

- Berger, N., Hanham, J., Stevens, C. J., & Holmes, K. (2019). Immediate feedback improves career decision self-efficacy and aspirational alignment. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 255. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00255

- Borland, J., and Coelli, M. (2021). Is it 'dog days' for the young in the Australian labour market? Australian Economic Review, 54(4), 421–444. doi:10.1111/1467-8462.12431

- Brotherhood of St Laurence (BSL). (2018). A fit-for-purpose national youth employment service: Submission to the Future Employment Services Consultation. Adelaide: VOCEDplus. Retrieved from library.bsl.org.au/jspui/bitstream/1/10893/4/TtW_CoP_Subm_Future_Employment_Services

_Consultation_Aug2018.pdf - Cassidy, N., Chan, I., Gao, A., & Penrose, G. (2020). Long-term unemployment in Australia. Bulletin, December. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved from www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2020/dec/long-term-unemployment-in-australia.html

- Hart, A., Psyllou, A., Eryigit-Madzwamuse, S., Heaver, B., Rathbone, A., Duncan, S. et al. (2020). Transitions into work for young people with complex needs: A systematic review of UK and Ireland studies to improve employability. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 48(5), 623–637. doi:10.1080/03069885.2020.1786007

- Height, J. (2016). Effective ways to support youth into employment. Sydney: Social Ventures Australia. Retrieved from apo.org.au/node/62631

- Kluve, J., Puerto, S., Robalino, D., Romero, J. M., Rother, F., Stoterau, J. et al. (2016). Do youth employment programs improve labor market outcomes? A systematic review, Ruhr Economic Papers, 648. doi: 10.4419/86788754

- Kluve, J., Puerto, S., Robalino, D., Romero, J. M., Rother, F., Stöterau, J. et al. (2017). Interventions to improve the labour market outcomes of youth: A systematic review of training, entrepreneurship promotion, employment services and subsidized employment interventions. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–288. doi:10.4073/csr.2017.12

- Lamb, S., & Huo, S. (2017). Counting the costs of lost opportunity in Australian education. Centre for International Research on Education Systems. Victoria University for the Mitchell Institute. Melbourne: Mitchell Institute.

- Lamb, S., Huo, S., Walstab, A., Wade, A., Maire, Q., Doecke, E. et al. (2020). Educational opportunity in Australia 2020: Who succeeds and who misses out. Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University, for the Mitchell Institute. Melbourne: Mitchell Institute.

- Mawn, L., Oliver, E. J., Akhter, N., Bambra, C. L., Torgerson, C., Bridle, C. et al. (2017). Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Systematic Reviews. 6(16). doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0394-2

- Modini, M., Joyce, S., Mykletun, A., Christensen, H., Bryant, R. A., Mitchell, P. B. et al. (2016). The mental health benefits of employment: Results of a systematic meta-review. Australasian Psychiatry, 24(4), 331–336. doi:10.1177/1039856215618523

- National Rural Health Alliance (NRHA). (2017) Poverty in rural and remote Australia. [Fact sheet]. Deakin, ACT: National Rural Health Alliance.

- Newton, B., Sinclair, A., Tyers, C., & Wilson, T. (2020). Supporting disadvantaged young people into meaningful work: An initial evidence review to identify what works and inform good practice among practitioners and employers. Brighton, UK: Institute for Employment Studies. Retrieved from www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/supporting-disadvantaged-young-people-meaningful-work

- OECD. (2017). Connecting people with jobs: Key issues for raising labour market participation in Australia. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264269637-en

- OECD. (2022). Youth not in employment, education or training (NEET) (indicator). Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/72d1033a-en.

- Productivity Commission. (2018). Rising inequality? A stocktake of the evidence. Commission Research Paper. Canberra: Productivity Commission. Retrieved from www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/rising-inequality/rising-inequality.pdf

- Qian, J., Riseley, E., & Barraket, J. (2019). Do employment-focused social enterprises provide a pathway out of disadvantage? An evidence review. Australia: The Centre for Social Impact Swinburne

- Saunders, P., Bedford, M., Judith, E., Brown, J., Naidoo, Y., & Adamson, E. (2018). Material deprivation and social exclusion among young Australians: A child-focused approach (SPRC Report 24/18). Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. doi.org/10.26190/5bd2aacfb0112

- The Smith Family. (2014). Young people’s successful transition to work: What are the pre-conditions? The Smith Family Research Report. Sydney: The Smith Family.

- Stanwick, J., Forrest, C., & Skujins, P. (2017). Who are the persistently NEET young people? Adelaide: NCVER.

- Wood, D., Griffiths, K., & Emslie, O. (2019). Generation gap: Ensuring a fair go for younger Australians. Melbourne: Grattan Institute. Retrieved from apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2019-08/apo-nid254026.pdf

1 ‘NEET rates’ have been criticised for being deficit-based and placing young people in a ‘problem state’, and research is beginning to emerge that uses a more strengths-based approach to measure and understand young people’s experiences (Basharat et al., 2020, p. 5). However, existing data on young people not in education, employment or training can provide insights into which young people are currently disengaged and maybe at risk of long-term unemployment.

2 The measure of socio-economic status summarises a range of information about the economic and social conditions of households including income level, housing quality, occupation level (typically of parents/caregivers) and access to material and social resources. Low socio-economic status indicates experiences of socio-economic disadvantage (ABS, 2016).