The tyrannies of distance and disadvantage

Factors related to children's development in regional and disadvantaged areas of Australia

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

November 2013

Ben Edwards, Jennifer Baxter

Download Research report

Overview

This research report investigates whether children in regional areas experience a "tyranny of distance" or a "tyranny of disadvantage".

In other words, are the gaps in children's development in regional areas compared to children living in the major cities explained by their distance from the major cities (remoteness), or is it because many regional areas are disadvantaged compared to the cities?

The analyses make use of data from Growing up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) to report on differences in family demographic and economic characteristics, parent wellbeing and parenting style, family social capital and access to services, and children's educational activities, and to relate those differences to how children are developing. The study includes children aged from 0-1 up to 8-9 years old.

Key messages

-

There is a tyranny of distance or disadvantage but it depends on the outcome examined.

-

There were enduring differences in child cognitive outcomes by whether children live in major city areas compared to regional areas, even after a broad range of other factors are taken into account, indicating that there is a tyranny of distance for cognitive outcomes.

-

There was also a tyranny of disadvantage for child emotional or behavioural problems. The findings suggest that children living in disadvantaged areas experience greater emotional or behavioural problems, even when all other factors are taken into account.

-

Findings from the current study provide the first systematic national information on a broad range of child outcomes, as well as a large number of other variables that are known to shape children's development, which could vary depending on geographic locality or level of disadvantage.

Executive summary

Families living in regional or rural areas of Australia can face challenges that may be less commonly experienced by families in major cities; for example, in accessing services and good-quality infrastructure. It is important to understand whether these different experiences and other differences in family life associated with living in regional areas have implications for children's development. Further, within geographically defined localities of Australia, some are more socio-economically disadvantaged than others. The level of socio-economic disadvantage in the local area in which children live is known to influence children's development, though it is not understood whether children living in disadvantaged major city areas have different experiences and outcomes compared to children living in disadvantaged regional areas.a

This report examines whether what children in regional areas experience is a "tyranny of distance" or a "tyranny of disadvantage". In other words, are the gaps in children's development in regional areas compared to children living in the major cities explained by their distance from the major cities (remoteness), or is it because many regional areas are disadvantaged compared to the cities? The analyses make use of data from the first three waves of Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) to report on differences in neighbourhood, family, social, educational and other contexts for children, and to relate those differences to how children are developing. The study includes children aged from 0-1 up to 8-9 years old, and therefore provides useful insights into issues of relevance to families with children in their early years.

The current study compares families and children living in different areas of Australia, first defined according to their remoteness (major cities, inner regional areas and outer regional areas), and then according to their level of disadvantage (defined using local area unemployment rates). While an important group, children from remote parts of Australia are not included in the current study, as they are not represented in sufficient numbers in LSAC to obtain robust statistical estimates. Throughout the report, comparisons are thus made across the following socio-geographic areas:

- major city areas with low unemployment rates;

- major city areas with high unemployment rates;

- inner regional areas with low unemployment rates;

- inner regional areas with high unemployment rates;

- outer regional areas with low unemployment rates; and

- outer regional areas with high unemployment rates.

The main question we sought to answer was how children's outcomes vary by geographic locality and by disadvantage. We examined two cognitive outcomes - receptive vocabulary and non-verbal reasoning - and two other outcomes - the risk of experiencing clinically significant emotional or behavioural problems and of being overweight.

Differences in local area characteristics, family demographics, parent wellbeing and parenting, social capital and access to services, and educational activities between geographic localities, or between disadvantaged and advantaged areas might be part of the explanation for any differences in child wellbeing that were observed, so we also provide information here on these characteristics for each of the six socio-geographic areas.

Contexts for child development

We focused on how the following contexts vary according to the remoteness and disadvantage of different areas across Australia:

- family demographic and economic characteristics;

- parent wellbeing and parenting style;

- family social capital and access to services; and

- children's educational activities.

The key findings from each context are discussed in more detail below. Together, there are a number of key differences in contexts that may be relevant to children's development according to geographic locality and level of disadvantage, which may be reflected in how children grow and develop. One of the important features of these factors is that many are amenable to change, and therefore could be the targets of policies and service delivery.

Family demographic and economic characteristics

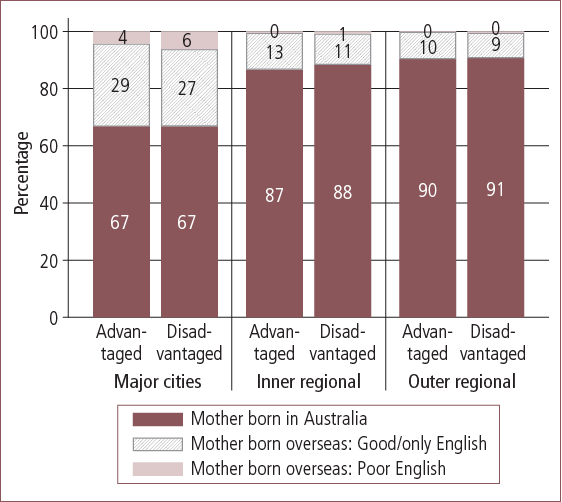

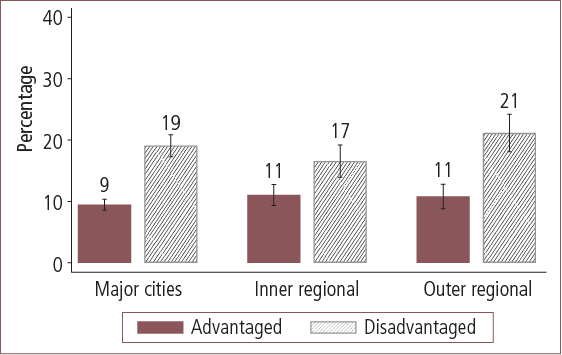

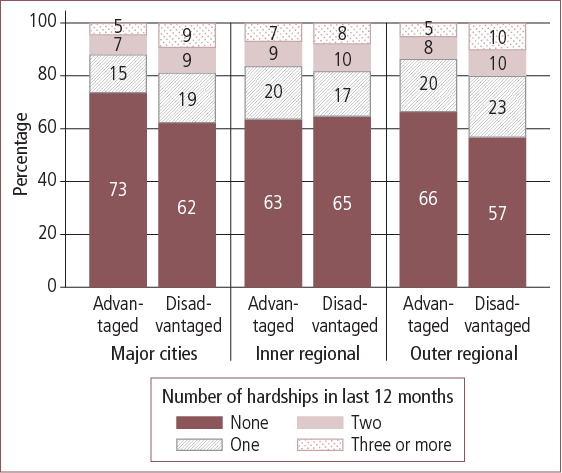

Advantaged areas in major cities stood apart from the other areas examined when focusing on family demographic and economic characteristics. On many measures, the circumstances of these families differed from those in disadvantaged major city areas, as well as from those in inner and outer regional areas. Differences according to disadvantage were also apparent in inner and outer regional areas, although the advantage/disadvantage disparity was not as great as it was in major city areas. For example, the percentages of single parents, mothers with a university education and mothers born overseas were similar in both disadvantaged and advantaged regional areas, but rates were different in advantaged and disadvantaged areas in the major cities. The percentage of jobless families and those experiencing financial hardship were more similar in disadvantaged and advantaged regional areas than in advantaged and disadvantaged major city areas, where there was a greater discrepancy.

Parent wellbeing and parenting style

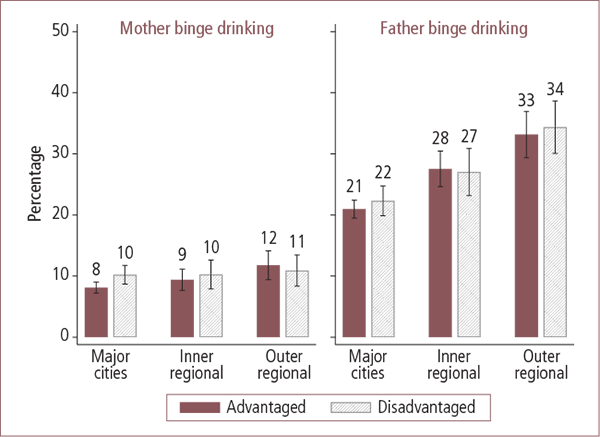

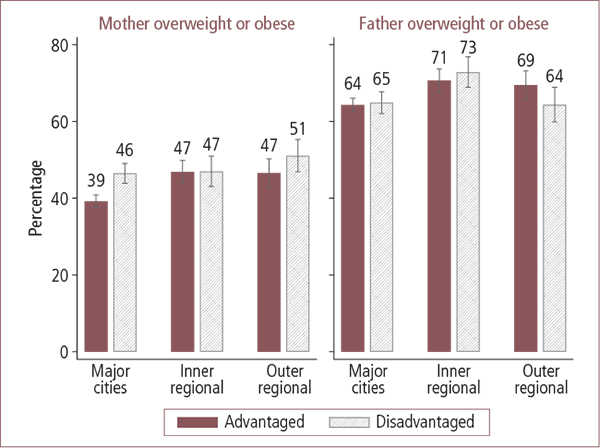

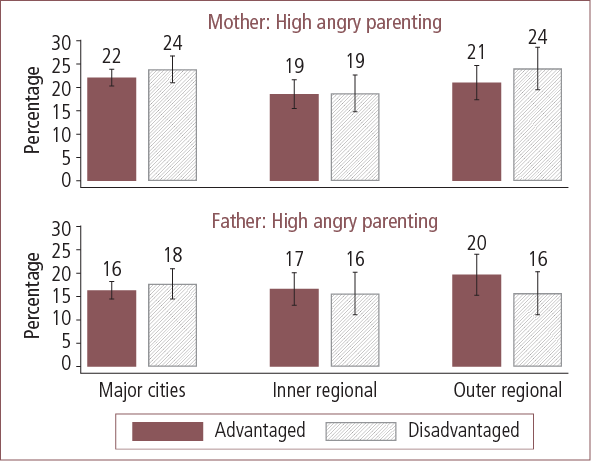

In terms of parent wellbeing and parenting style, there were fewer differences. There were no differences by geographic locality or level of disadvantage in terms of mental health and relationship hostility. Fathers had much higher rates of risky binge drinking in regional areas, particularly in outer regional areas, than in major city areas; but though these rates were high, they were consistent with other studies (e.g., Miller, Coomber, Staiger, Zinkiewicz, & Toumbourou, 2010). There were differences by locality and level of disadvantage for mothers and fathers being overweight. For mothers, a higher proportion was overweight in regional areas, as well as in disadvantaged areas (regardless of locality), with the highest percentage being those in disadvantaged outer regional areas. On the other hand, for fathers, the highest levels of being overweight were in inner regional areas. In outer regional areas, higher proportions of fathers were overweight in advantaged compared to disadvantaged areas. There was little difference in parenting styles of mothers and fathers between geographic localities or between disadvantaged and advantaged areas.

Family social capital and access to services

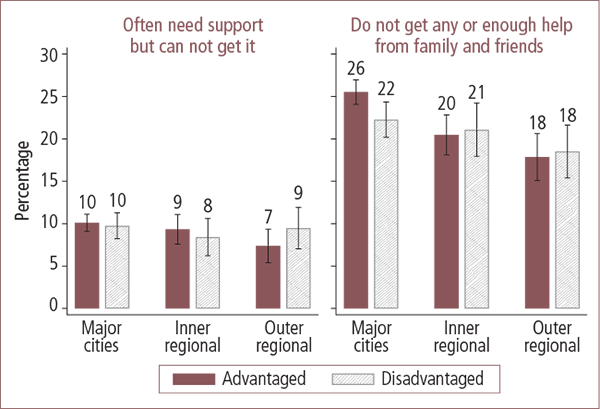

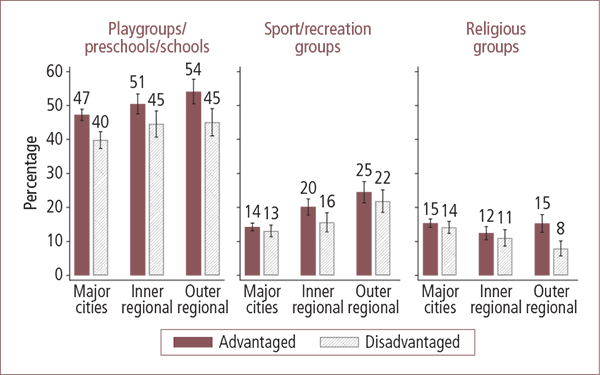

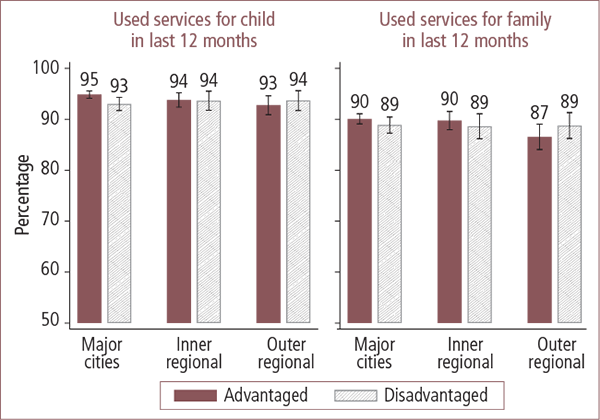

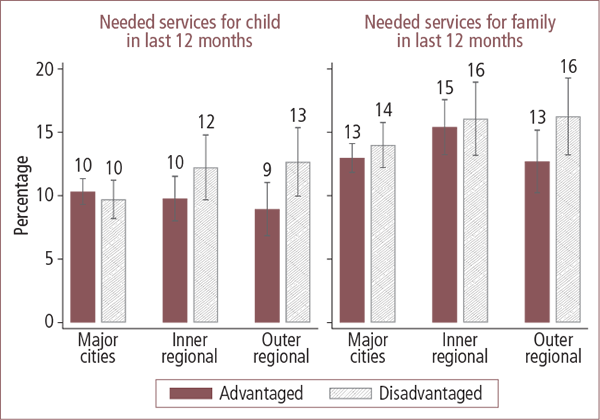

Some measures of social capital and service use for children did not vary according to areas of remoteness and disadvantage, but there were some protective factors for parent and child wellbeing that were higher in regional areas than in major cities, such as involvement in community organisations, sense of neighbourhood belonging and safety, and obtaining help from family and friends. Also, ratings of neighbourhood quality - including parents' perceptions of safety and parents' involvement in volunteer or community groups - were higher in advantaged areas than in disadvantaged areas.

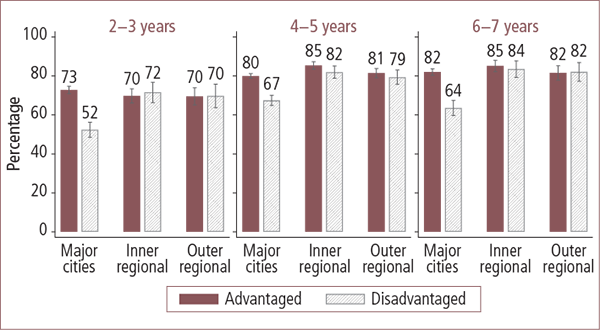

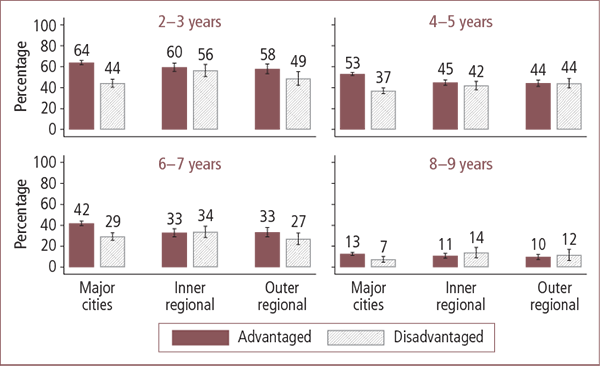

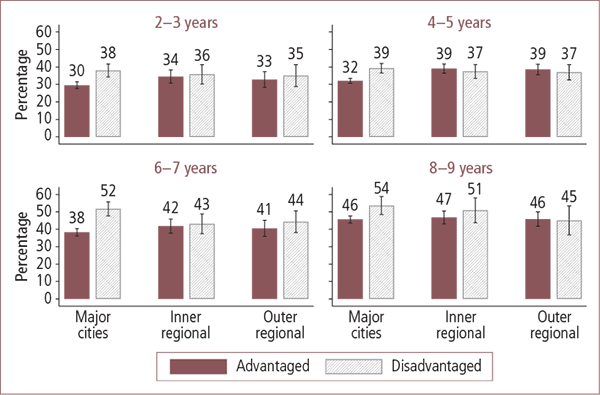

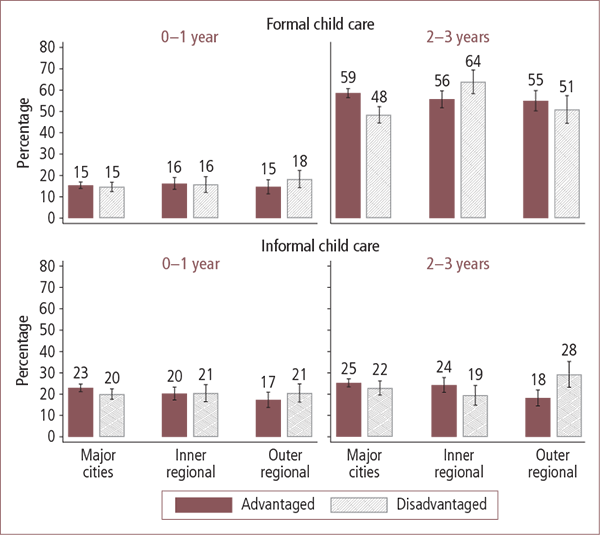

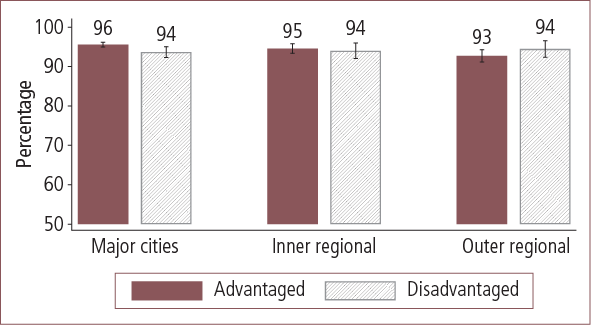

Children's educational activities

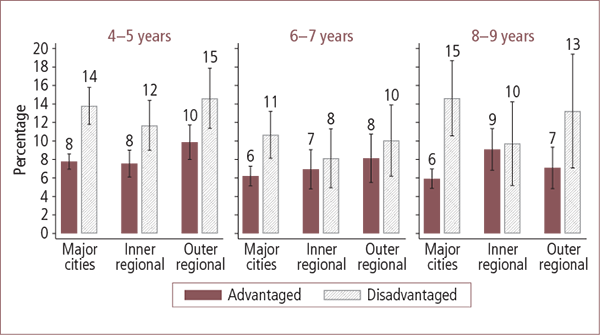

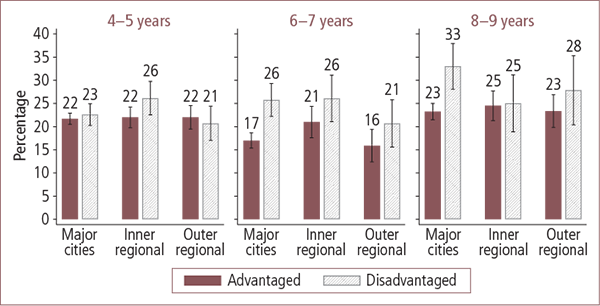

Children's educational activities are likely to be shaped by parents' aspirations for their children's learning, and by their employment arrangements, which can mean parents have varying needs for child care. There were some differences in children's educational activities in the home, with fewer children living in disadvantaged areas having 30 or more children's books in the home and being read to daily than in advantaged areas. Children's television viewing was also marked by consistent differences between advantaged and disadvantaged areas for all ages, with children living in disadvantaged areas being more likely to watch a greater amount of television. Within major city areas, differences between disadvantaged and advantaged areas were most apparent; however, high levels of television viewing were similar in both advantaged and disadvantaged areas in inner and outer regional areas. Also, those children in disadvantaged areas of the major cities were less likely to be enrolled in outside-school-hours care, or to participate in other outside-school activities. There were no consistent differences in children's attendance at child care between geographic localities or between disadvantaged and advantaged areas, and rates of preschool attendance were consistently high across all socio-geographic areas.

Child outcomes

The key question of the report is the extent to which children's outcomes are shaped by a tyranny of distance (differences between geographic localities) or by a tyranny of disadvantage (differences between areas with higher compared to lower levels of unemployment). Findings from the current study provide the first systematic national information on a broad range of child outcomes, as well as a large number of other variables that are known to shape children's development, which could vary depending on geographic locality or level of disadvantage.

Is there a tyranny of distance or disadvantage? The answer to this question depends on the outcome examined. The evidence seems to suggest that there are enduring differences in child cognitive outcomes by whether children live in major city areas compared to regional areas, even after a broad range of factors are taken into account, indicating that there is a tyranny of distance for cognitive outcomes.

There was also a tyranny of disadvantage for child emotional or behavioural problems. The findings suggest that children living in disadvantaged areas experience greater emotional or behavioural problems, even when all other factors are taken into account. While there were differences by disadvantage between children's levels of cognitive and physical outcomes when not adjusting for other demographic characteristics, these differences could be partly or wholly explained by the demographic composition of families and aspects of the children's social context, including parenting and social capital.

A note of caution in the interpretation of findings from the statistical modelling is warranted, as the modelling precludes causal explanations, even though there was a rich set of variables included.

Study implications

Turning to the study implications, the authors ask what the role of location-based approaches is in the development of service delivery and policy. First, an important point should be made about having location-based services targeted at families living in disadvantaged areas. Even if there are no additional effects of disadvantaged areas over and above the demographic composition of families living in such areas, these types of policies should be considered, as they offer an effective means of planning and targeting services to disadvantaged families. Clearly, in instances where there are persistent differences between disadvantaged and advantaged areas even after a large number of other factors are taken into account - such as is the case with children's emotional or behavioural problems - then there is an additional reason and benefit to targeting services in areas of high unemployment.

In the case of geographic localities, a focus on enhancing the learning environments of children may be important, given that findings from this study also suggest that there were persistent differences in children's cognitive outcomes between the major cities and regional areas that were not explained by the rich set of variables that were included in the statistical models. Enhancing the early education experiences of children and improving the quality of primary school education, as well as getting parents more involved in children's education at home (such as through reading programs) may be important in addressing the "gap" between children's cognitive outcomes in the major cities and in regional areas.

To understand differences in children's outcomes between geographic localities, it is important to note that academic achievement and cognitive development are not the only predictors of positive development, and that on other factors - such as emotional or behavioural problems and overweight or obese - there were no differences between geographic localities once other factors were taken into account in the statistical models. Moreover, high levels of achievement may be important if children wish to attend university, but in many occupations, tertiary qualifications are not relevant. In other studies of rural areas, adolescents learned independence, leadership and social skills by interacting with their family through working on farms, engaging in extracurricular activities and community groups, and taking up leadership positions in these community groups (Elder & Conger, 2000). Many of these skills are transferable to jobs that may be more prevalent in regional areas.

It is important to be mindful that children's development occurs in different environmental contexts, and the development of policies and delivery of services need to be nuanced to cater to the different needs and strengths of children growing up in this "wide brown land".

Footnote

a For the sake of clarity, the terms "geographic locality" or "locality" are used in this report to refer generically to the three areas defined by remoteness: major city, inner regional and outer regional. "Socio-geographic areas" is used to refer generically to the six areas defined by remoteness ´ disadvantage. "Regional areas" is used when referring to both the inner and outer regional areas (but not the major cities).

1. Introduction

There is growing awareness that issues faced by families living in regional or rural areas of Australia are not necessarily the same as those faced by families living in major cities. Differential access to services and infrastructure, along with different social and demographic characteristics of the various geographic localities of Australia make it essential for us to understand whether such differences have implications for children. Further, there are many areas in Australia that are socio-economically disadvantaged. The level of disadvantage in the local area in which children live is known to influence children's development, although it is not understood whether children living in disadvantaged major city areas have different experiences and outcomes compared to children living in disadvantaged regional or rural areas.1

This report examines whether what children in regional areas experience is a "tyranny of distance" or a "tyranny of disadvantage". In other words, are the gaps in children's development in regional areas compared to children living in the major cities explained by their distance from the major cities (remoteness), or is it because many regional areas are disadvantaged compared to the cities? The analyses make use of data from the first three waves of Growing up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) to report on differences in neighbourhood, family, social, educational and other contexts for children, and to relate those differences to how children are developing. The study includes children aged from 0-1 up to 8-9 years old, and therefore provides useful insights into issues of relevance to families with children in their early years.

The current study compares families and children living in different areas of Australia, first defined according to their remoteness (major cities, inner regional areas and outer regional areas), and then according to their level of disadvantage (defined using local area unemployment rates). The remoteness measure we use is based upon an underlying Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia Plus (ARIA+) score, which is derived from information about road distances from major service centres (Glover & Tennant, 2003). While a very important group, children from very remote parts of Australia are not included in the current study, as they are not represented in sufficient numbers in LSAC to obtain robust statistical estimates. Throughout the report, comparisons are made thus across the following socio-geographic areas:

- major city areas with low unemployment rates;

- major city areas with high unemployment rates;

- inner regional areas with low unemployment rates;

- inner regional areas with high unemployment rates;

- outer regional areas with low unemployment rates; and

- outer regional areas with high unemployment rates.

Comparisons between regional areas and major cities often ignore levels of socio-economic disadvantage, which can be significant in regional areas. The focus of this report is to highlight issues faced by children in regional areas and children in disadvantaged areas, and therefore the literature that follows (Section 2) concentrates on what is known on these topics.

The structure of the report is as follows. Section 2 provides a brief review of the literature on the geographic distribution and demography of the Australian population, socio-economic changes in regional areas in Australia, geographic location and child development, and local area disadvantage and child development. Section 3 describes the data and methods used in the study. Sections 4 to 8 analyse the characteristics of families and children who live in the six socio-geographic areas described above that might potentially explain differences in child outcomes. Section 4 focuses on differences in the local area, such as the socio-demographic characteristics of the area and parents' ratings of neighbourhood quality. Section 5 reports on family demographic and economic characteristics, including family form, maternal education, employment status of parents, country of birth, financial hardship and housing tenure. In Section 6, differences in parent wellbeing and parenting are documented. Social capital - the social connections between people in the neighbourhood that encourage trust, support and understanding (Stone, 2001) - and the services that are available to families in each of the six socio-geographic areas is examined in Section 7. Section 8 provides information on children's education, both in the home (books, reading by parents, TV watching and educational expectations) and outside the home (child care and preschool). Section 9 focuses on the key research question of whether a tyranny of distance or disadvantage affects children's outcomes. It describes differences in learning, social and emotional wellbeing and physical health between children living in the six socio-geographic areas, while taking into account many of the characteristics described in Sections 4 to 8. Section 10 discusses the overall findings and implications of the study.

Footnote

1 For the sake of clarity, the terms "geographic locality" or "locality" are used in this report to refer generically to the three areas defined by remoteness: major city, inner regional and outer regional. "Socio-geographic areas" is used to refer generically to the six areas defined by remoteness × disadvantage. "Regional areas" is used when referring to both the inner and outer regional areas (but not the major cities).

2. Literature review

2.1 Geographic distribution and demography of the Australian population

According to 2011 Australian Census data, seven in ten (70%) Australians live in major cities, almost one in five (18%) live in inner regional areas, almost one in ten (9%) in outer regional areas and around one in forty live in remote or very remote areas (1.6% remote and 1.1 % very remote).2

Largely as a result of the decline in the agricultural sector, the proportion of the Australian population living outside the capital cities declined from the early 1900s to the 1970s'in 1906, 63% of the population lived outside of the capital cities, and this fell to about 36% by 1976 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2007). Since then, the regional population has been relatively stable. From 1996 to 2006, there was a small increase in population growth in inner regional areas (0.8%), but the number of people living in outer regional areas was stable (ABS, 2008). There was similarly little change between 2006 and 2011 in the distribution of the population across regional areas, with the percentages in 2006 in each of the remoteness areas being very similar to those given above for 2011 (see Baxter, Gray & Hayes, 2011).

There have been considerable changes in population distribution within Australia. One particularly noteworthy change is the movement of the population towards coastal areas, referred to as a 'sea change'. Major provincial centres and towns around capital cities have also experienced growth, largely reflecting the relocation of retirees, lifestyle changes, high city house prices and an increased prevalence of jobs where people can work remotely from home (ABS, 2007). Another very significant factor in the growth of regional towns has been the flourishing mining industry, which has led to significant increases in the population of those areas involved in that business.

2.2 Socio-economic changes in regional areas in Australia

Although not the focus of this study, it is important to review recent socio-economic changes that have occurred in regional areas in Australia. The decline in the importance of agriculture over the last few decades has been a key one of these. The reduction in the terms of trade for primary produce such as wheat, wool and barley that began in the mid-1970s has continued through the 2000s (Productivity Commission, 2009), and the droughts in 2002-03 and 2006-10 accelerated the associated decrease in agricultural employment in inner and outer regional and remote areas (Edwards, Gray & Hunter, 2009; Productivity Commission, 2009). Analysis of the 2001 and 2006 Census of Population and Housing by the Productivity Commission (2009) showed that over that period the share of people employed in agriculture reduced by 2% in inner regional areas and 3% in outer regional and remote areas. This was particularly important for outer regional and remote areas, as in those areas agriculture employed more people than mining and manufacturing combined.

While the number of farms has decreased, the average farm size has increased. There were 196,000 farms in 1968-69, but by 2004-05 this had dropped to 130,000. Over the same period, the average farm size increased from around 2,500 hectares to 3,400 hectares, and the concentration of agricultural output from the largest farms also increased (Productivity Commission, 2009).

Further analysis of the Census of Population and Housing has provided a more nuanced perspective on those regional areas that have been economic winners and losers (Baum, Haynes, Gellecum, & Han, 2007). Based on the 2001 Census, advantaged areas include the mining regions, areas with high levels of amenity or tourism, and those that have important regional and rural service functions. In terms of disadvantage, Baum et al. described regional areas that were characterised by poor labour market outcomes, high levels of financial stress, and household joblessness; these were usually in areas where there had been high levels of manufacturing supported by protectionism. Also described as being disadvantaged were areas with high levels of employment in agriculture but with far more low-income than high-income earners, and the 'income poor but asset rich' amenity-based areas on the coasts of NSW and Queensland that are characterised by high levels of internal migration by retirees and welfare recipients.

Tony Vinson's (2007) Dropping Off the Edge report documented areas of concentrated disadvantage across Australia, based on the indicators of low income, high rates of disability, elevated levels of criminal convictions, poorer economic conditions (unskilled workers, long-term unemployment, limited computer use/access to Internet), and low educational attainment (incomplete secondary education, early school leaving). Vinson identified areas of disadvantage in Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, and found that across the five largest states, 52% of the 170 disadvantaged locations were in rural areas (60% in Queensland, 48% in New South Wales, 33% in Victoria, 60% in South Australia and 70% in Western Australia). This highlights that in Australia, locational disadvantage is as much an issue for regional and rural areas as it is for the major cities.

2.3 Geographic location and child development

There has been limited research comparing children's development in regional and rural areas of Australia with that of those living in cities, with a particular gap existing in data available from large-scale national studies. Bell and Merrick (2009), in an editorial about rural child health, stated: 'There is an urgent need to develop an existing body of research on the needs of rural and remote children and adolescents' (p. 86).

Recent analyses using LSAC data for 8-9 year old children, showed that some differences are apparent in outcomes for children in regional areas (Baxter, Gray, & Hayes, 2011). In terms of learning or cognitive outcomes, children were doing best in major cities, followed by inner regional areas and then outer regional areas. For physical outcomes, children in inner regional areas were somewhat less likely to have very good outcomes compared with children in outer regional areas or major cities. Socio-emotional outcomes were not found to vary across geographic localities; however, these analyses were intended to provide a broad overview of these data and did not examine the reasons for such differences.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW; 2009) report, A Picture of Australia's Children, brought together some national information on differences in outcomes of children by geographic locality. For example, data on child mortality for the period 2004-06 suggest there were some differences by locality'rates of death for infants (under 1 year) in major cities (about 4 per 1,000 live births) were significantly lower than in inner regional and outer regional areas (about 5 and 6 per 1,000 live births respectively). The rates of death per 100,000 for children aged 1-14 years were also higher in inner and outer regional areas compared to major cities (although the difference was only statistically significant for outer regional areas).

The National Assessment Program'Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) provides national data on the academic achievement of Australian students by locality. In 2010, there were consistent differences between Year 3 students by geographic location, with children living in metropolitan areas having better mean scores on reading, writing, language conventions and numeracy when compared to children living in provincial and remote areas (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2010). This was the case even when the sample was restricted to children who were not Indigenous.

Analysis of the 2007 Australian National Children's Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey suggests that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children aged 2-12 years is higher among children living in inner regional areas (24%) than in major cities (22%) and outer regional and remote areas (22%) (AIHW, 2009). However, a smaller study of 636 children aged 5-12 years residing in rural and urban areas of Victoria found no significant differences in the percentage of children who were overweight or obese (29% in urban areas and 27% in rural areas; Cleland et al., 2010). A New Zealand study of 3,275 children aged 5-15 years, collected as part of the 2002 National Children's Nutrition Survey, reported that urban boys and girls were more likely to be overweight or obese than their rural counterparts (1.3 times for boys and 1.4 for girls; Hodgkin, Hamlin, Ross, & Peters, 2010).

The 2005 ABS Childcare Survey provides some information on rates of attendance at preschool or long day care according to geographic locality. Attendance at preschool or long day care was similar across localities for 4-year-olds; however, 3-year-olds attended at the highest rates in major cities, followed by inner regional areas, and then outer regional and remote areas (AIHW, 2009).

The most notable international longitudinal study of rural children has been the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP; Elder & Conger, 2000). This study followed the lives of 451 children (since seventh grade) and their families from an agricultural area of rural Iowa, United States, from 1989 to 2000. While more focused on adolescence, the IYFP was an important study because it tracked a relatively large sample of families during a period of significant economic change in the agricultural sector. Researchers from the study also developed the family stress model of economic hardship'a theoretical model of how families cope with economic strains and the pathways of influence on children's developmental outcomes. We will use this theoretical model to inform this study and also describe it in this section.

Elder and Conger (2000) reported that, at the time of the study, a significant restructuring of the agricultural sector in Iowa had taken place, similar in nature but greater in scope than what had occurred in Australia over a similar period. Between 1950 and 1990, the number of farms in the study area halved, while the size of the farms doubled. The population declined by 12% over this forty-year period, with the majority of the population loss flowing out of the farm sector. The value of farmland decreased from a high of over US$4,500 per acre in 1978 to US$1,500 per acre in 1987. Other economic indicators also reflected this decline; for example, building permits had reduced to a fraction of the number approved from the 1970s, while retail sales in the area also decreased.

The key findings from the Iowa Youth and Families Project emphasised that how parents coped with economic hardship individually (e.g., mental health) and as a couple (e.g., parental relationships) influenced their ability to parent effectively, and made a difference as to how economic hardships were experienced by their children (Elder & Conger, 2000). The family stress model of economic hardship postulates a series of mediated relationships between financial hardship, parents' mental health, conflict between caregivers, parenting practices and children's mental health (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). In brief, the model proposes that the experience of low income and lack of parental employment influences the number of financial hardship events experienced by the family (e.g., difficulty paying bills, making financial cutbacks, or selling goods to generate income). The experience of financial hardship, in turn, produces elevated levels of parental mental health problems. The negative affect or emotional distress from the adverse experience of financial hardship also produces aggression, in the form of increased conflict in the parental relationship. Both mental health problems and parental relationship conflict are proposed to decrease warm parenting, and increase angry, critical and inconsistent parenting behaviours directed towards children. Although originally developed and tested using data from the IYFP (Conger & Elder, 1994), empirical support for the family stress model of economic hardship has been found in several other studies, using samples representing a broad range of national and ethnic groups, geographic locations and children's ages (for a review of these, see Conger & Donnellan, 2007).

In addition to the role of the family factors discussed above, findings from the IYFP suggest that the role of extended family ties is important in successful child development. Grandparents were particularly important in supporting vulnerable children in the IYFP. Children who had parents who exhibited low parenting warmth but had a close grandparent did better academically and socially than children with low parenting warmth who did not have a close grandparent (Elder & Conger, 2000).

Parental involvement in community life (such as church, school and civic groups) was also protective. Families where parents were actively involved in community life themselves were more likely to have children who were involved in church groups, sports and social clubs, and leadership programs at school. All of these activities were associated with youth having better grades, being more socially competent and having lower levels of antisocial behaviour. Interestingly, families who continued to work on their farms and were not displaced from farming were also more likely to be involved in the community and to have children who were involved in sporting and social clubs (Elder & Conger, 2000).

2.4 Local area disadvantage and child development

As discussed above, family functioning and child outcomes are likely to be affected by a family's experience of financial stress. In addition to the effects of a family's own experience of financial stress, living in economically disadvantaged areas may also influence the physical and social environments of parents and their children. In this report and in the majority of research focusing on the influence of local areas or neighbourhoods on children, local areas are defined by using Statistical Local Areas (SLAs), which are administrative units akin to local government areas. While there has been criticism of using administratively defined areas, the empirical research suggests that, while not perfect, they do accord with residents' perceptions of their local area (De Marco & De Marco, 2010).

The associations between local area socio-economic disadvantage and child wellbeing are due both to the characteristics of the people and families living in the disadvantaged communities (e.g., their individual education levels, employment, substance use) and to the impacts of these neighbourhood characteristics themselves (over and above individual and family characteristics). While disentangling these two effects is difficult, there is now good evidence of the impact of neighbourhood characteristics on children (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000).

Living in a disadvantaged neighbourhood, compared to living in a less disadvantaged neighbourhood, has been linked to:

- poorer outcomes for children, including poorer learning and behavioural outcomes, poorer physical health and higher rates of child maltreatment (Coulton, Crampton, Irwin, Spilsbury, & Korbin, 2007; Edwards, 2005; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000);

- poorer health in adults, as evidenced by higher rates of infectious diseases, asthma, smoking and depression, and poorer diet and self-rated health (Kawachi & Berkman, 2003); and

- reduced job and educational prospects for youth (Andrews, Green & Mangan, 2004; Galster, Marcotte, Mandell, Wolman & Augustine, 2007).

There are several ways in which neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage influences young children's development:

- The quality of neighbourhood resources and services may be poorer in more disadvantaged areas; for example, parents' ratings of the quality of neighbourhood facilities are lower in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Edwards, 2006).

- High rates of joblessness and residential mobility that characterise many disadvantaged neighbourhoods have an impact on community social capital (Sampson, Morenoff & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). For instance, lower neighbourhood socio-economic status and higher residential instability in the neighbourhood have been associated with less social interaction and fewer connections between people, lower levels of reciprocity, lower expectations of shared child control, and a reduced sense of belonging (Edwards, 2006; Sampson, Morenoff & Earls, 1999).

- Crime rates are also generally higher and ratings of neighbourhood safety lower in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Sampson et al., 1999), and parental concerns about the safety of neighbourhoods can have a negative impact on their mental health which, in turn, can impair their capacity to effectively parent their children (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Orr et al., 2003).

One explanation for these influences that has been neglected in the literature is the role that the macro-economy plays in increasing neighbourhood income inequality. Internationally, there has been a trend towards the geographic concentration of poverty and affluence (Massey, 1996). For instance, the growth in income inequality between neighbourhoods in Australia since the 1970s mirrors the trends of other developed countries, such as the US and Canada (Gregory & Hunter, 1995; Hunter & Gregory, 2001). In Australia, after each economic recession there has been a decline in manufacturing sector jobs and an increase in the availability of service sector employment (Hunter & Gregory, 2001). Service sector income growth has also increased at a faster rate. Given that manufacturing tends to be concentrated in more disadvantaged areas and higher paying service sector jobs in advantaged areas, both these factors explain the growth in neighbourhood income inequality.

Another limitation of previous research has been that studies have primarily focused on examining neighbourhood disadvantage in the context of urban cities and not regional areas (De Marco & De Marco, 2010). Thus, in Australia, it is unknown whether children growing up in disadvantaged regional areas experience poorer outcomes than children living in major city areas.

2.5 Summary

By advancing our knowledge of family life in different localities of Australia, this report builds on research conducted to date. Comparing disadvantaged and advantaged areas ('the tyranny of disadvantage') is informed by the large international literature on the influence of neighbourhood disadvantage on children's development. The focus on differences in geographic locality ('the tyranny of distance') is more novel and, as much of the work in this area is not Australian, it will be important to assess to what extent the findings from the US translate to Australia's geographic context.

Footnote

2 Derived from 2011 Australian Census, Tablebuilder.

3. Data and method

3.1 The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children

The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children is conducted in a partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The study aims to examine the impact of Australia's unique social, economic and cultural environment on children growing up in today's world.

The study follows two cohorts of children who were selected from across Australia. Children in the B cohort ("babies" at Wave 1) were born between March 2003 and February 2004, and children in the K cohort ("kindergarten" at Wave 1) were born between March 1999 and February 2000. At the time of writing, data from three main waves of the survey were available, collected in 2004, 2006 and 2008. Data from the fourth wave of the survey became available in 2011.

The percentage of the sample that has been retained from one wave to another has been over 90%. For instance around 90% of the Wave 1 sample was retained in Wave 2 and 95-97% of the Wave 2 sample was retained for Wave 3. As a consequence, the Wave 3 sample comprises around 86% of the original Wave 1 sample. Attrition across waves has meant the responding sample has some biases; for example, by being more likely to be couple parents with higher education levels.

Sample weights have been designed to adjust sample estimates to take account of these and a range of other differences in the responding sample (Sipthorp & Misson, 2009). However, sample weights have not been adjusted to take account of non-response to particular instruments, such as the self-completion questionnaire, or to other item non-response. Table 1 shows the smaller numbers of self-completion questionnaires completed, relative to the total numbers of responding families.

| B cohort | K cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 year | 2-3 years | 4-5 years | 4-5 years | 6-7 years | 8-9 years | |

| Total families | 5,107 | 4,606 | 4,386 | 4,983 | 4,464 | 4,331 |

| % of Wave 1 sample | - | 90.19 | 85.88 | - | 89.58 | 86.92 |

| Self-complete data from Parent 1 (primary carer) | 4,341 | 3,536 | 3,831 | 4,229 | 3,495 | 3,807 |

| Self-complete data from Parent 2 (secondary carer) | 3,696 | 3,128 | 2,753 | 3,388 | 2,949 | 2,680 |

Note: In Waves 1 and 2, Parent 1 filled in a self-completion questionnaire that was mailed back to the survey. In Wave 3, Parent 1 filled in a self-completion questionnaire while the interviewer was present.

The sampling frame for LSAC was created using the then Health Insurance Commission's (HIC) Medicare database, a comprehensive database of Australia's population. Using the database, a stratified sample of postcodes was generated, a sample of children selected and their families invited to participate in the study. The final sample, comprising 54% of these families, was broadly representative of Australian children (AIFS, 2005). For a detailed description of the design of LSAC, see Gray and Smart (2009).

For each family, parents were asked to nominate one parent as the "primary carer"; that is, the parent who knew the most about the child. In most families, parents nominated the mother as the primary carer (96-98% of cases, varying slightly across cohorts and waves). This parent provides an extensive set of data about their child and about themselves, and also, on some items, about the other parent. Interviews and self-complete questionnaires are used to collect this information. In couple families, the other parent is also asked to complete a questionnaire, which contains a large amount of information, particularly relating to parenting practices and different measures of wellbeing.

LSAC has been designed so that the study child is the main focus of the study. Reports of different respondents are sought in order to obtain information about the child's behaviour in different contexts. Information is collected from the child (using physical measurement, cognitive testing and, depending upon the age of the child, interviews), the parents who live with the child (biological, adoptive or step-parents), home-based and centre-based carers for preschool children who are regularly in non-parental care, and teachers (for school-aged children). From Wave 2, information has also been obtained from parents who live apart from their child but who still have contact with the child.

In addition to the interviews and self-completion questionnaires, data are also collected from children through the completion of time use diaries, and other data are matched from administrative sources and aggregate Census data. Census data have been used in this paper.

3.2 Sample scope, and geographic and disadvantaged classifications

This study uses data from both the B and K cohorts, in Waves 1 to 3 of LSAC.

As one of the aims of this report is to examine geographic variation in children's lives, a key issue is that of the coverage of LSAC. The LSAC sample was designed to cover most of Australia, but some remote areas were excluded. As a result, children in the sample who are from remote areas are not representative of all children in such areas. Therefore, in this analysis, children living in remote areas of Australia have been excluded.

Children were classified according to whether they lived in a major city, an inner regional area or an outer regional area. This Australian Standard Geographic Classification of remoteness is based upon an underlying ARIA+ score (see Section 1), which is derived from information about road distances from major service centres. While the ARIA is an accepted measure of remoteness, it does have some limitations. For example, the classification of Hobart as an inner regional area and Darwin as an outer regional area is misleading, as residents of these capital cities have good access to services (Glover & Tennant, 2003).

The ABS provides information about the remoteness classification of postal areas, and this information was matched to the postcodes in LSAC. Some postal areas did not align exactly with the LSAC remoteness classification; for example, a postal area might be 80% major city and 20% inner regional. Where this occurred, the postal area was assigned the value belonging to its largest remoteness area. This allowed areas to be identified as major cities, inner regional areas or outer regional areas.

As shown in Table 2, around two-thirds of children in the LSAC sample lived in major cities, with 21% living in inner regional areas and 15% in outer regional areas.

| B cohort | K cohort | Totals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 year | 2-3 years | 4-5 years | 4-5 years | 6-7 years | 8-9 years | ||

| Sample counts | Sample counts | ||||||

| Major cities | 3,099 | 2,799 | 2,651 | 2,974 | 2,659 | 2,577 | 16,759 |

| Inner regional | 1,063 | 960 | 925 | 1,018 | 928 | 906 | 5,800 |

| Outer regional | 794 | 713 | 681 | 838 | 736 | 710 | 4,472 |

| Total | 4,956 | 4,472 | 4,257 | 4,830 | 4,323 | 4,193 | 27,031 |

| Percentage | Percentage | ||||||

| Major cities | 65.54 | 63.71 | 65.49 | 62.42 | 64.37 | 62.51 | 64.01 |

| Inner regional | 19.96 | 20.97 | 20.10 | 21.68 | 20.91 | 22.04 | 20.93 |

| Outer regional | 14.50 | 15.32 | 14.41 | 15.90 | 14.72 | 15.46 | 15.06 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Note: Excludes children living in remote or very remote regions of Australia. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

The distribution of different geographic localities of Australia is shown in Figure 1. We can see from this that examples of major cities are Perth, Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, Newcastle and Brisbane. Inner regional areas include the Blue Mountains (NSW), Echuca (Victoria), Bundaberg (Queensland) and the Adelaide Hills (South Australia). Outer regional areas include Tamworth (NSW), Mildura (Victoria), Rockhampton (Queensland), Port Augusta (South Australia), Bunbury (Western Australia) and Burnie (Tasmania).

Figure 1: Geographic remoteness in Australia

Notes: The range of ARIA+ values in each of the remoteness categories is shown in brackets in the legend. For details of how ARIA+ values are calculated refer to AIHW (2004).

The other key aspect of these analyses was to classify areas according to their level of disadvantage. Of course, "disadvantage" is a relative term, and also not one that can easily be defined. As a result, there are various possible approaches to the classification of areas as being disadvantaged. To more closely align with the policy emphasis on labour market participation and locational disadvantage as part of the social inclusion agenda (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2009), we used local area unemployment rates as the basis for the classification.

The only regular series available on local area unemployment rates in relatively small geographic areas is the Small Area Labour Market (SALM) data. The SALM series provides quarterly estimates of the unemployment rate for every Statistical Local Area (SLA)3 in Australia (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations [DEEWR], 2009). Details of the construction of SALM data can be found in Appendix A. Quarterly unemployment rates for each SLA over the period 2004 to 2008 are used in this report. These data are provided for SLA boundaries from the 2001 edition of the Australian Standard Geography Classification (ABS, 2001).

The SALM SLA-level unemployment rates were matched to LSAC unit record data according to the SLA of a family's residence. For each wave and cohort, the month and the year of each respondent's interview was identified, and the unemployment rate for that quarter was matched. This means that, depending on the time of interview, two children could be living in the same SLA but have somewhat different area-level unemployment rates, reflecting that changes can occur in the labour market over time.

As there is no definitive point at which an unemployment rate could be said to indicate disadvantage, the distribution of these rates was used to identify at which point there might be a suitable cut-off. We categorised an SLA with an unemployment rate of more than 6% as being disadvantaged, and with a rate of less than or equal to 6% as advantaged.4 This resulted in 28% of the (weighted) sample being classified as living in disadvantaged areas. An important requirement of the classification of disadvantage for this report was to ensure that there were sufficient sample sizes for adequate statistical precision in the different types of areas when categorised as disadvantaged and not disadvantaged. Table 3 shows that at each wave and for each cohort the minimum sample size was 120 (for 4-5 year old children in the B cohort living in disadvantaged outer regional areas), which was sufficient for the analytical purposes of this report.

| B cohort | K cohort | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 year | 2-3 years | 4-5 years | 4-5 years | 6-7 years | 8-9 years | ||

| Sample counts | Sample counts | ||||||

| Major cities disadvantaged | 1,006 | 649 | 365 | 865 | 598 | 357 | 3,840 |

| Major cities advantaged | 2,085 | 2,099 | 2,271 | 2,097 | 2,011 | 2,218 | 12,781 |

| Inner regional disadvantaged | 387 | 291 | 182 | 389 | 299 | 196 | 1,744 |

| Inner regional advantaged | 672 | 614 | 727 | 627 | 569 | 700 | 3,909 |

| Outer regional disadvantaged | 348 | 229 | 120 | 349 | 246 | 142 | 1,434 |

| Outer regional advantaged | 435 | 427 | 555 | 484 | 430 | 561 | 2,892 |

| Total disadvantaged | 1,741 | 1,169 | 667 | 1,603 | 1,143 | 695 | 7,018 |

| Total not disadvantaged | 3,192 | 3,140 | 3,553 | 3,208 | 3,010 | 3,479 | 19,582 |

| Percentage | Percentage | ||||||

| Major cities disadvantaged | 21.23 | 17.42 | 11.27 | 19.35 | 16.95 | 10.71 | 16.37 |

| Major cities advantaged | 44.41 | 47.30 | 54.37 | 43.07 | 48.52 | 52.00 | 48.05 |

| Inner regional disadvantaged | 7.13 | 6.96 | 4.58 | 8.30 | 7.07 | 5.17 | 6.59 |

| Inner regional advantaged | 12.85 | 13.54 | 15.38 | 13.42 | 13.34 | 16.77 | 14.16 |

| Outer regional disadvantaged | 6.74 | 5.78 | 2.91 | 7.05 | 5.44 | 3.58 | 5.34 |

| Outer regional advantaged | 7.64 | 9.00 | 11.49 | 8.80 | 8.67 | 11.77 | 9.49 |

| Total disadvantaged | 35.10 | 30.15 | 18.75 | 34.69 | 29.46 | 19.46 | 28.30 |

| Total not disadvantaged | 64.90 | 69.85 | 81.25 | 65.31 | 70.54 | 80.54 | 71.70 |

| Disadvantaged areas in: | |||||||

| Major cities | 32.35 | 26.92 | 17.16 | 31.00 | 25.89 | 17.07 | 25.42 |

| Inner regional | 35.69 | 33.93 | 22.93 | 38.20 | 34.63 | 23.55 | 31.76 |

| Outer regional | 46.88 | 39.09 | 20.20 | 44.42 | 38.56 | 23.34 | 35.98 |

| Total | 35.10 | 30.15 | 18.75 | 34.69 | 29.46 | 19.46 | 28.30 |

It is important to acknowledge that there was an overall decline in the unemployment rate over the period 2004 to 2008. During this period, the national unemployment rate went from 5.7% in March 2004 to 4.4% in December 2008 (Gray, Edwards, Hayes & Baxter, 2009). Table 3 shows that, as would be expected, higher proportions of each of the cohorts were classified as disadvantaged in Wave 1 compared to later waves. This is partly because unemployment rates were higher at the time of the Wave 1 interviews. Also, survey attrition means that the Wave 2 and Wave 3 samples had proportionally more families from advantaged rather than disadvantaged areas. The changes in local area unemployment rates across the cohorts/waves of LSAC, and differences according to geographic locality and disadvantage are shown in Appendix Table A1.

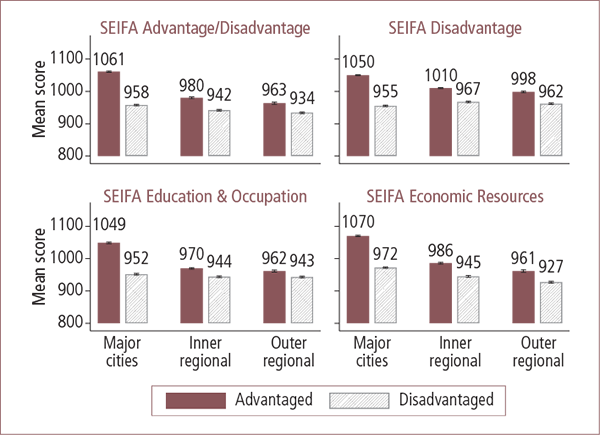

Another tool used to identify the level of disadvantage in a locality is the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA; Edwards, 2005, 2006; Edwards & Bromfield, 2009, 2010). There are four SEIFA indices: the SEIFA Index of Advantage/Disadvantage; the SEIFA Index of Disadvantage, which focuses on low-income earners, people with relatively low educational attainment, and those who are unemployed; the SEIFA Index of Education and Occupation; and the SEIFA Index of Economic Resources, which measures the financial aspects of advantage and disadvantage (e.g., high-income earners, small business owners, and people paying high rents and mortgages).

The SEIFA Index of Advantage/Disadvantage, in particular, has been used in other Australian research. The index is the weighted average of a composite of 31 variables, such as income, unemployment, occupation and education (Trewin, 2004). Areas are ranked and the average area has a score of 1,000, with 70% of areas having scores ranging from 900 to 1,100. Lower scores indicate more disadvantage and less advantage, and higher scores indicate the reverse. Using these data, for example, Edwards (2011) categorised areas with a SEIFA score in the bottom 25% as being disadvantaged. The main limitation of this approach relates to the fact that SEIFA is derived from so many different variables that when interpreting results, it is not clear which of these underlying factors is the most influential. Similar criticisms have been made about the use of measures of individual socio-economic status (see Magnusson & Duncan, 2002, for a discussion). Given that current Australian Government policy emphasises labour market programs, then a measure of locational disadvantage that has clear links with these types of programs is important. An alternative measure that could be useful from a policy perspective would be local area information on numbers of recipients of Centrelink pensions or allowances; however, these data are not available, so in their absence the area-level unemployment rate is the most useful measure.

Another limitation with SEIFA is that it is produced from the Census of Population and Housing and is therefore only updated every five years. Much can change in the interim, and having a measure of locational disadvantage that is sensitive to changes in the local labour market is a significant factor in preferring SLA unemployment rates from the SALM data.

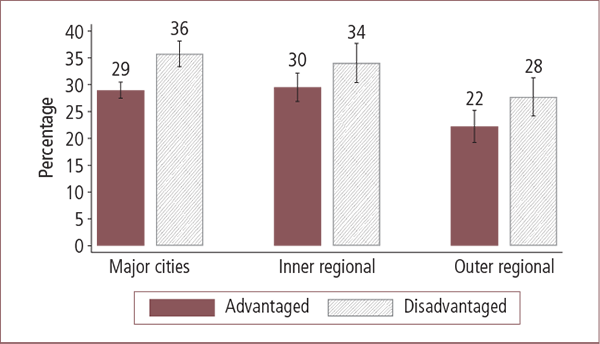

The SLA unemployment rates classification of localities does correlate in the expected direction with the four different SEIFA indices (Figure 2). The pattern of results is similar for the SEIFA Index of Advantage/Disadvantage, the SEIFA Index of Disadvantage and the SEIFA Index of Economic resources, in which areas that are advantaged in major cities have much higher SEIFA scores than any other group. For all the SEIFA indices, the differences between advantaged and disadvantaged areas is also greatest (statistically significant at the 95% level of confidence) in major cities, with smaller differences being apparent between advantaged and disadvantaged areas in outer regional and inner regional areas respectively.

Figure 2: Mean SEIFA index scores for Australian advantaged and disadvantaged areas, by geographic locality

Notes: Sample sizes: Major cities advantaged n = 4,182; major cities disadvantaged n = 1,871; inner regional advantaged n = 1,299; inner regional disadvantaged n = 776; outer regional advantaged n = 919; outer regional disadvantaged n = 697. Differences in mean scores for remoteness × disadvantage, localities overall, disadvantage overall, and disadvantage within each locality were statistically significant (p < .05).

Source: LSAC Wave 1, B and K cohorts combined, linked Census data

Apart from major cities, it is notable that the differences by disadvantage and across geographic localities were more limited for the SEIFA Index of Education and Occupation. In a sense, this result is expected, as education and occupational status in particular areas are different from labour force participation.

3.3 Methods

Much of this report focuses on comparing the characteristics of families across the six socio-geographic areas:

- major city areas with low unemployment rates;

- major city areas with high unemployment rates;

- inner regional areas with low unemployment rates;

- inner regional areas with high unemployment rates;

- outer regional areas with low unemployment rates; and

- outer regional areas with high unemployment rates.

To make these comparisons, graphs showing means or percentages, with 95% confidence intervals or "I" bars, have been presented. In the graphs, non-overlapping confidence intervals in two columns suggest that we can be 95% confident that the two values represented in the columns are significantly different. However, overlapping confidence intervals does not necessarily suggest that the corresponding means or percentages are significantly different. Therefore, statistical tests were also conducted to assess whether differences in the figures were statistically significant.

Tests evaluated the significance of differences between: (a) the six socio-geographic areas (remoteness × disadvantage); (b) the three geographic localities overall; (c) disadvantaged and advantaged areas; and (d) disadvantaged and advantaged areas within each geographic locality. When the variable was a continuous measure, such as the SEIFA scores shown in Figure 2, t-tests were used to compare between disadvantaged and advantaged areas, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare between the three types of geographic localities or between the six socio-geographic areas. When the variable was categorical, chi-square tests were used to assess the level of significance in differences across any of the groups. The results of these statistical tests are shown in the figure footnotes.

In Sections 4 to 9 of this report, various child and family characteristics are examined in relation to the socio-geographic areas described above. To present this information, we usually focus on characteristics as measured at one wave, combining the cohorts. While information is often available from multiple waves of LSAC, including data from more than one wave is not necessary to demonstrate the relationships. In fact, if more than one wave were used, more sophisticated methods would be required to assess the significance of differences across the six groups. As such, presentation of data from one wave proved to be the best approach. For some analyses, it was relevant to consider characteristics at different ages of children, and in those cases, more than one wave of data was used, but in doing so, these data were presented and analysed separately by the ages of the children. The sources of data are noted throughout the report. The specific characteristics examined are described in detail in each of the following sections.

Section 9 focuses on the children's learning, socio-emotional and physical outcomes; specifically whether children in regional areas experience a tyranny of distance or a tyranny of disadvantage in relation to these outcomes. Is it distance from major cities that explains the gaps in children's development in regional areas or is it mainly because these regional areas are often disadvantaged? As with other descriptive analyses, the various outcome measures are presented by the six socio-geographic areas. However, to formally test the statistical significance of differences between children living in advantaged and disadvantaged areas, and between the three geographic localities, we use multivariate analyses. These multivariate analyses also enable us to formally test whether any differences in children's outcomes according to disadvantage or distance can be explained by the different characteristics of the children and families in these areas. The measures used and the multivariate techniques applied are described in more detail in Section 9.

Footnotes

3 SLAs are based on the boundaries of incorporated bodies of local government, where these exist. SLAs are the smallest unit of geography for which statistical estimates can be calculated between Census years and therefore are most appropriate for use in longitudinal studies.

4 An alternative approach to classifying disadvantaged areas would have been to identify, at any wave, those regions with unemployment rates in the top 20% of the distribution. There are a few concerns with such an approach, which are best illustrated by a hypothetical example. Consider the example of area A, which is categorised as being disadvantaged in Wave 1 (i.e., it is in the top 20% of unemployment rate areas). By Wave 2, the unemployment rate for area A has increased further; however, the unemployment rates in other areas have increased even more than area A so that now, at Wave 2, even though the unemployment rate has increased in area A, it is no longer defined as being disadvantaged. In our preferred approach, area A would continue to be defined as being disadvantaged and the other areas that have had substantial increases in unemployment rates would also fall into this category.

4. Local area contextual factors

This section presents an overview of the different geographic localities within which the LSAC children live and comparing them according to their relative remoteness, as well as comparing areas that are disadvantaged to those that are not. First, we build a socio-demographic profile of the residents in these areas by using data linked to LSAC from the ABS Census of Population and Housing (the Census). In addition to these Census data on the socio-demographic profile of neighbourhoods, we present LSAC data on parent ratings on different aspects of the quality of their neighbourhood. More detailed demographic characteristics as captured in LSAC are then presented in Section 5.

A summary of the data analysed in this section is presented in Table 4.

| Measure | Values | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Linked Census data (for SLA) | ||

| Economic resources | Percentage of persons completed Year 12 | Based on interpolation from 2001 and 2006 Census |

| Percentage of persons working (employed) | ||

| Percentage of persons with weekly income of < $1,000 | ||

| Cultural diversity | Percentage of persons who were Australia-born | Based on interpolation from 2001 and 2006 Census |

| Percentage of persons speaking only English at home | ||

| Percentage of persons with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origins | ||

| Internet | Percentage of households with Internet capacity | Only available from 2006, so shown for Wave 2 (2006) |

| Percentage of households with broadband | ||

| LSAC data | ||

| Perceptions of neighbourhood (primary carers' ratings) | Agree or strongly agree that: | |

| Neighbourhood is safe | ||

| Neighbourhood is clean | ||

| Neighbourhood has good parks, playgrounds and play spaces | ||

| Neighbourhood has good roads, footpaths and lighting | ||

4.1 The demography of the area: Linked Census data

The linked Census data provide a broad view of the nature of the area within which the LSAC respondents live, and also provide information that is collected independently of LSAC, which is useful for building a picture of the area, as represented by those who are not parents of young children.

The linked Census data were derived from the two most recent Census periods, conducted in 2001 and 2006. As LSAC was conducted in 2004, 2006 and 2008, the 2004 and 2008 collections do not match these Census years; therefore, for 2004 and 2008, the characteristics from 2001 and 2006 were used to interpolate probable values for these years. Questions relating to Internet access were not asked in 2001, and so these data were not interpolated. (See the AIFS, 2011, LSAC Data User Guide, for more information about the linkage and interpolation process.)

These analyses present Census data for one wave of LSAC only, with Wave 1 being used for most data. Wave 2 data were used for Internet/broadband access, since these Census data were collected in 2006, around the time of the Wave 2 collection.

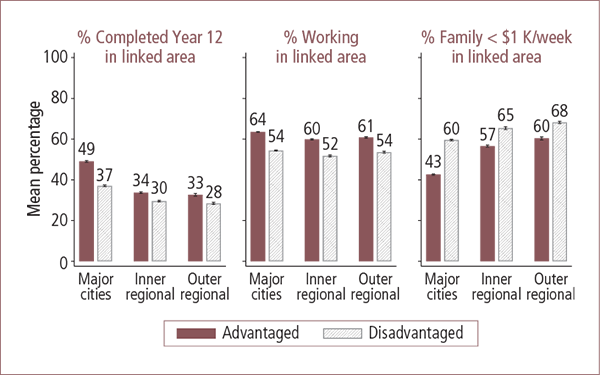

Figure 3 provides a comparison of some indicators of economic resources across the geographic localities and disadvantaged areas, using linked Census data.5 This figure shows, for the SLAs of each LSAC respondent, the percentage who had completed Year 12, the percentage in paid work and the percentage of families who had an income of less than $1,000 per week.

Figure 3: Area-level economic resources in Australian advantaged and disadvantaged areas, by geographic locality

Notes: Sample sizes: Major cities advantaged n = 4,182; major cities disadvantaged n = 1,871; inner regional advantaged n = 1,299; inner regional disadvantaged n = 776; outer regional advantaged n = 919; outer regional disadvantaged n = 697. Differences in mean percentages for remoteness × disadvantage, localities overall, disadvantage overall, and disadvantage within each locality were statistically significant (p < .05).

Source: LSAC Wave 1, B and K cohorts combined, linked Census data

Compared to the other geographic localities, major city areas included a relatively high percentage of people who had completed a secondary education. This was especially so in advantaged areas in major cities (49%). Even in disadvantaged areas in major cities the percentage who completed their secondary education (37%) was relatively high compared to advantaged and disadvantaged inner and outer regional areas. Across all localities, the disadvantaged areas included a smaller percentage of the population who had completed secondary education than advantaged areas, with the lowest percentages being in disadvantaged inner and outer regional areas. Differences according to disadvantage, however, were not as great in the inner and outer regional areas as they were in major city areas.

Looking at the percentage of the population who were in paid work across the geographic localities, there was an expected difference in percentages according to whether or not the area was disadvantaged. Also, within advantaged areas, there was about a three-percentage point difference between geographic localities, with higher percentages being in paid work in major cities than in the inner or outer regional areas. Within disadvantaged areas, there was a higher percentage in paid work in major cities and outer regional areas compared to inner regional areas.

The percentage of families with incomes of less than $1,000 per week also varied across the geographic localities. Advantaged major city areas had the lowest percentage of families with lower incomes (43%), while the highest percentage of these families were living in disadvantaged inner (65%) and outer regional areas (68%). The differences in the percentages of lower income families were large, even between disadvantaged major city areas compared to disadvantaged inner and outer regional areas. In disadvantaged areas of major cities, 60% of families had an income of less than $1,000 per week, compared to 65-68% of families in disadvantaged inner and outer regional areas.

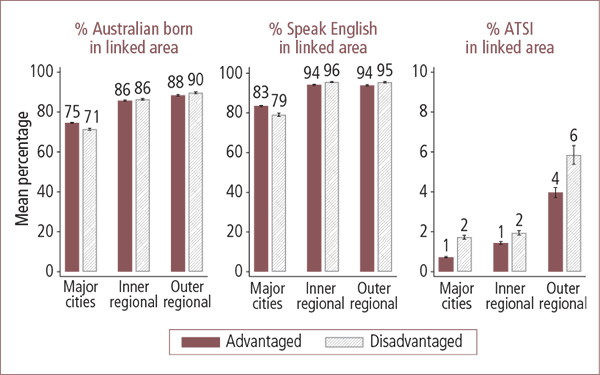

Cultural diversity is considered next. Figure 4 shows three indicators from the Census of ethnicity or cultural diversity across Australian localities. First, the percentage of Australian-born residents varied most in regard to the remoteness of the area, with much higher percentages of Australian-born people living in regional areas than in major cities. Within the regional areas, there was no apparent difference in the proportion of Australian-born residents according to the disadvantage of the area. Within major cities, however, a difference was apparent, with a somewhat smaller proportion of Australian-born people living in disadvantaged areas. These findings reflect migration patterns that see new arrivals to Australia being concentrated in disadvantaged areas of major cities (Hugo et al., 2010).

Figure 4: Cultural diversity in Australian advantaged and disadvantaged areas, by geographic locality

Notes: Sample sizes: Major cities advantaged n = 4,182; major cities disadvantaged n = 1,871; inner regional advantaged n = 1,299; inner regional disadvantaged n = 776; outer regional advantaged n = 919; outer regional disadvantaged n = 697. Differences between disadvantaged and advantaged areas in the percentages who were Australia-born were non-significant overall and within inner and outer regional areas (p > .05). All other differences in mean percentages for remoteness × disadvantage, localities overall, and disadvantage within major city areas were statistically significant (p < .05).

Source: LSAC Wave 1, B and K cohorts combined, linked Census data.

The proportions of people speaking only English at home presented a similar picture, with the vast majority of those living in areas of inner and outer regional Australia speaking only English. In major cities, while most people only spoke English, this proportion was lower than in regional areas, and especially so in disadvantaged parts of the major cities.

The proportion of the population who were Indigenous Australians within the LSAC respondents' localities was small overall, but Figure 4 shows that this proportion was highest in outer regional Australia, and was especially high in disadvantaged parts of those localities. We have not included remote parts of Australia here, where the percentage who were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander would have been significantly higher again (see Baxter et al., 2011).

Increasingly, the Internet is being used for service delivery (e.g., for banking) by both the government and private sectors. The proportion of the population having access to a reliable and fast Internet connection is therefore an important indicator of an area's level of access to services. Figure 5 indicates that both overall access to the Internet and access to broadband in particular show the same types of differences across geographic localities. The more remote the locality, the smaller the percentage of homes with access, and within localities, disadvantaged areas had a smaller percentage of homes with access.

Figure 5: Internet access in Australian advantaged and disadvantaged areas, by geographic locality

Notes: Sample sizes: Major cities advantaged n = 4,106; major cities disadvantaged n = 1,245; inner regional advantaged n = 1,180; inner regional disadvantaged n = 586; outer regional advantaged n = 848; outer regional disadvantaged n = 471. Differences in mean percentages for remoteness × disadvantage, localities overall, disadvantage overall, and disadvantage within each locality were statistically significant (p < .05).

Source: LSAC Wave 2, B and K cohorts combined, linked 2006 Census data

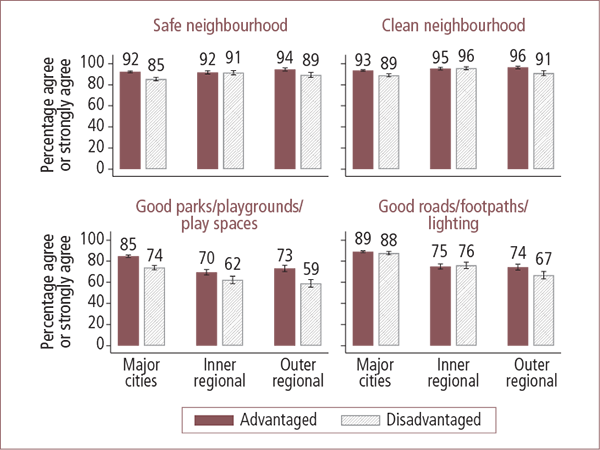

4.2 Parent reports on neighbourhood quality: LSAC data

In the LSAC survey, parents are asked to rate the quality of their neighbourhoods. In this section, we report on the primary carers' ratings of the degree to which they strongly agreed or agreed that their neighbourhood or local area: (a) was safe; (b) was clean; (c) had good parks, playgrounds and play spaces; and (d) had good roads, footpaths and lighting.

Figure 6 shows that, according to Wave 1 data, LSAC parents were quite positive about how safe and clean they perceived their neighbourhood to be. This was especially so for advantaged areas, but also for disadvantaged regional areas. Small differences in these measures were apparent across localities; most notably, significantly smaller percentages of parents living in disadvantaged areas in major cities and outer regional areas reported that their neighbourhood was safe and clean. For example, when comparing advantaged major city areas to disadvantaged major city areas, there was a seven percentage point difference in the proportion of parents agreeing that their neighbourhood was safe.

Figure 6: Perceptions of neighbourhood quality in Australian advantaged and disadvantaged areas, by geographic locality

Notes: Sample sizes: Major cities advantaged n = 4,182; major cities disadvantaged n = 1,871; inner regional advantaged n = 1,299; inner regional disadvantaged n = 776; outer regional advantaged n = 919; outer regional disadvantaged n = 697. Differences by disadvantage were not significant (p > .05) for "safe neighbourhood" and "clean neighbourhood" in inner regional areas, and for "good roads, footpaths and lighting" in major cities and inner regional areas. All other differences in percentages for remoteness × disadvantage, localities overall, disadvantage overall, and disadvantage within each locality were statistically significant (p < .05).

Source: LSAC Wave 1, B and K cohorts combined

With regard to neighbourhood safety, the lack of differences between disadvantaged and advantaged inner regional areas may reflect the protective role that higher levels of social capital play in these communities. Certainly, work by Edwards and Bromfield (2009, 2010) showed that children living in socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods with higher levels of social capital in the area had better social and emotional wellbeing than children living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods where social capital was lower. Other US studies have also reported similar findings; for example, in disadvantaged areas of Chicago, violent crime rates were lower when residents reported higher levels of social capital (Sampson, Raudenbush & Earls, 1997).

Parental perceptions of having access to good parks, playgrounds and play spaces varied between geographic localities and between disadvantaged and advantaged areas. When compared to parents living in advantaged areas, a significantly smaller percentage of parents living in the same locality but in disadvantaged areas reported that they had good parks, playgrounds and play spaces in their area. However, a greater percentage of parents living in disadvantaged major city areas reported having good play facilities than parents living in disadvantaged inner and outer regional areas. In advantaged areas, those most likely to agree that they had such facilities were those living in major cities, followed by those in outer then inner regional areas. For disadvantaged areas, there was a steady reduction in the percentage of parents who reported they had good play facilities from major cities through to inner, then outer regional areas. Only 59% of parents living in disadvantaged outer regional areas reported having good parks and playgrounds in their neighbourhood.

There were differences between advantaged and disadvantaged outer regional areas with respect to parents' perceptions about good roads, footpaths and lighting. A smaller percentage of parents living in a disadvantaged outer regional areas compared to advantaged outer regional areas reported good roads, footpaths and lighting. This finding may reflect inadequate infrastructure in more regional areas, particularly in the more disadvantaged areas.

Summary

This section has explored how local area characteristics vary for families living in different geographic localities of Australia. The clearest and most consistent findings were in regard to the differences between advantaged and disadvantaged areas. Disadvantaged areas, as defined by local area unemployment rates, were also characterised by disadvantage on measures of human capital and employment, as well as access to the Internet. Differences between disadvantaged and advantaged areas were particularly marked in major city areas. LSAC parents' reports on the quality of their neighbourhood also varied somewhat according to the disadvantage of the area, and this was most apparent with regard to having access to good parks, playgrounds and play spaces.

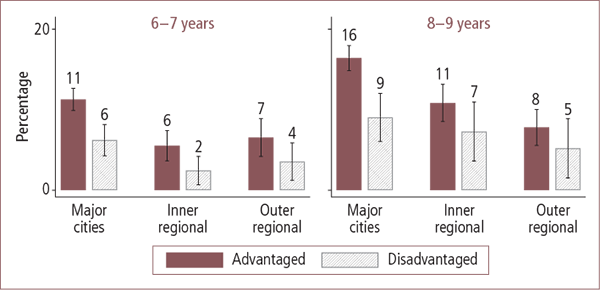

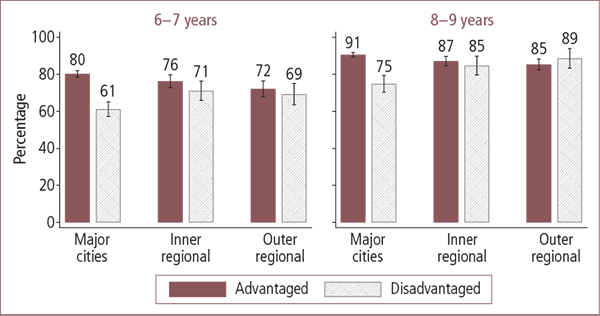

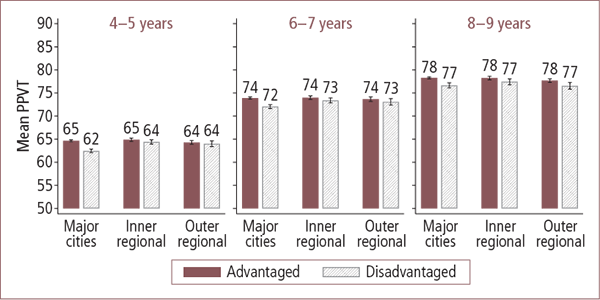

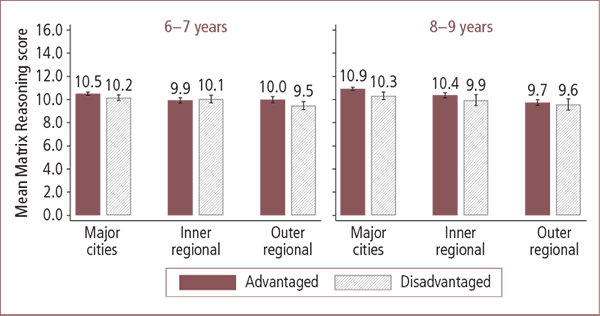

Some characteristics of local areas also varied according to the remoteness of the area, with higher levels of education and greater access to the Internet (and broadband) being evident among those living in major cities, and higher percentages of families having relatively low incomes in inner regional and outer regional areas. According to LSAC parents, the quality of the neighbourhood was not rated as highly in inner and outer regional areas, especially in terms of access to good parks, playgrounds and play spaces and having good roads, footpaths and lighting.