Working Together to Care for Kids

A survey of foster and relative/kinship carers

May 2018

Download Research report

Overview

AIFS was commissioned and funded by the Department of Social Services (DSS) to conduct the survey Working Together to Care for Kids: A Survey of Foster and Relative/kinship Carers. This national survey involved telephone interviews with 2,203 foster and relative/kinship carers in late 2016 and was aimed at providing a better understanding of the characteristics and needs of the carers of children who are living in out-of-home care in Australia.

Key messages

-

The study found that relative/kinship carers were more likely to be older, to report lower educational attainments, and to be from an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background.

-

Relative/kinship carers were less likely to live with a partner and to be not as well-off as foster carers.

-

Many carers reported that they were coping despite difficulties, and felt that they were making a positive difference to a child's life.

-

However the study identified that there is the need to better inform and prepare carers for their role and to provide more support while children are in their care.

Executive summary

AIFS was commissioned and funded by the Department of Social Services (DSS) to conduct the survey Working Together to Care for Kids: A Survey of Foster and Relative/kinship Carers (also known as the 'Working Together to Care for Kids Survey', or WTCKS). This national survey involved telephone interviews with 2,203 foster and relative/kinship carers in late 2016 and was aimed at providing a better understanding of the characteristics and needs of the carers of children who are living in out-of-home care in Australia. Participants in this survey were foster and relative/kinship carers who were registered as formal carers (i.e., had at least one child in care under 18 years of age living with them) at 31 December 2015 in all jurisdictions except the Northern Territory.1 Most questions relating to children who were placed under the carers' care were directed to one child (referred to as "study child" or "study children").

Key findings

Characteristics of carers

This study provided significant insight into the socio-demographic characteristics of the participating carers (n = 2,203: relative/kinship: 53%; foster: 47%). The vast majority of carers were female (relative/kinship: 87%; foster: 88%) with a mean age of 53 years. Nearly one-half of carers were aged between 50 and 64 years, and substantial proportions were aged 65-69 years (12%) or 70 years and older (6%). Over one-tenth of carers were Indigenous, a higher percentage than there is in the general population. Most carers under 65 years of age were not in paid employment. Nearly one-half of carers had two or more children in out-of-home care at the time of the survey, with one-fifth having three or more children in their care.

The majority of carers had an annual gross household income of less than $60,000, while one-fifth of carers were relying on less than $30,000. Carers had lower levels of annual gross household income when compared to general Australian households. In addition, a greater proportion of carers lived in public housing compared to the general population, according to HILDA. While these data suggest that carers were financially not as well-off as the general Australian household, most carers reported that they were "reasonably comfortable".

Relative/kinship carers were more likely to be older, to report lower educational attainments, and to be from an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background and less likely to live with a partner. In addition, relative/kinship carers were not as well-off as foster carers. Male carers were more likely to be older than female carers and were more likely to report higher educational attainment, to be in paid employment and to live with a partner.

Care experience

Most carers reported that they were approached by their jurisdictional department or agency about becoming a carer for the study child, although this was more common for foster carers than relative/kinship carers. A substantial minority of relative/kinship carers were asked by the child's parents or a family member to care for the study child.

The mean age of study children was 9 years old and the median duration that they had been living with their current carer was 3.4 years. Although just under one-half of carers reported that the study children were in their care for two years or less, over one-tenth reported a much longer duration (at least 10 years). Foster carers were more likely than relative/kinship carers to have cared for the study child for less than one year.

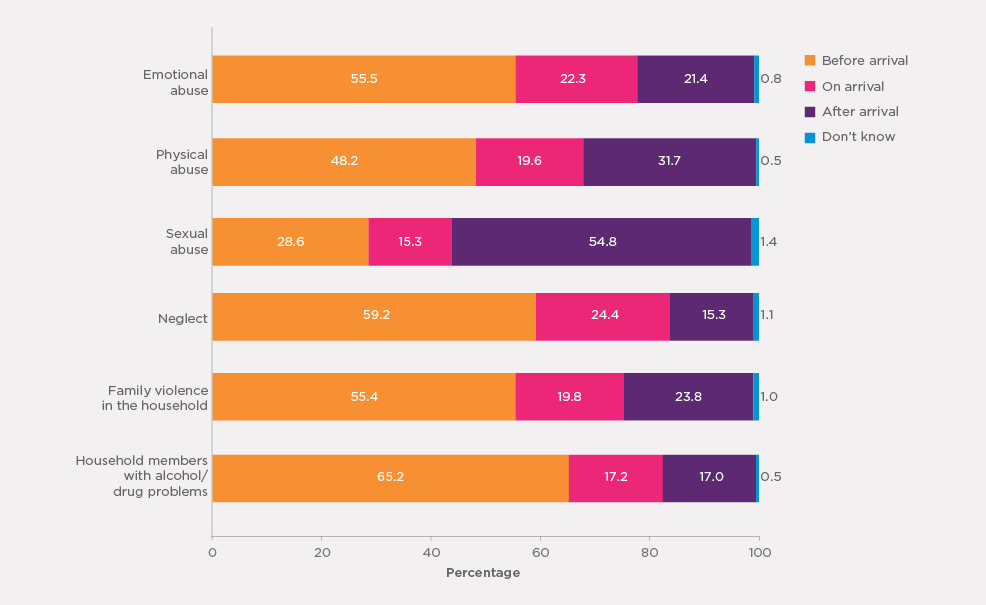

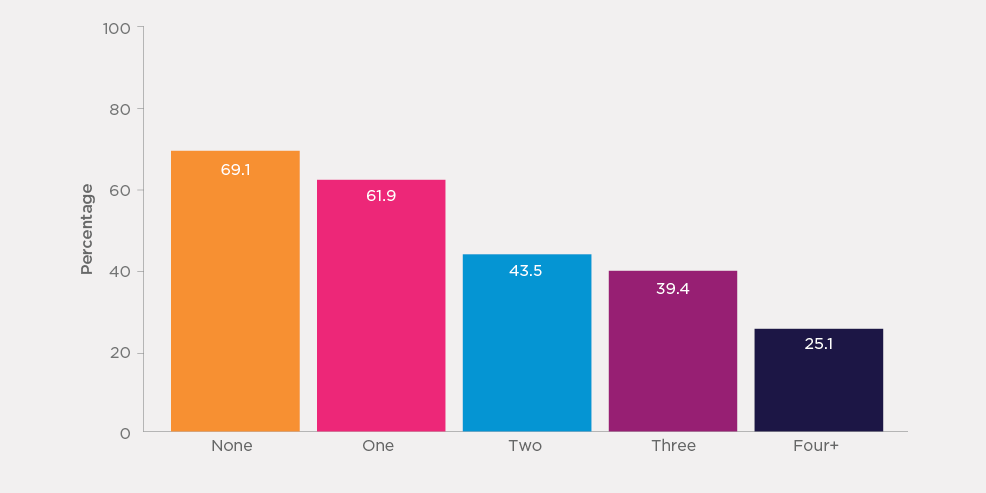

Most carers (86%) reported being aware that the study child in their care had experienced or been exposed to at least one of six indicators of abuse, neglect and problems at home. The most common indicators reported as experienced by study children were having lived with household member(s) who had alcohol or drug use problems (72%), followed by neglect (68%), family violence (62%) and emotional abuse (55%).

Although most carers were aware of the study child's experience of the various indicators of abuse/neglect prior to their arrival in their household, a significant minority of carers only became aware of such prior history after the study child had been in their care. In instances of sexual abuse, a majority (55%) of carers reported that they had not learned of its occurrence until after the child was in their care.

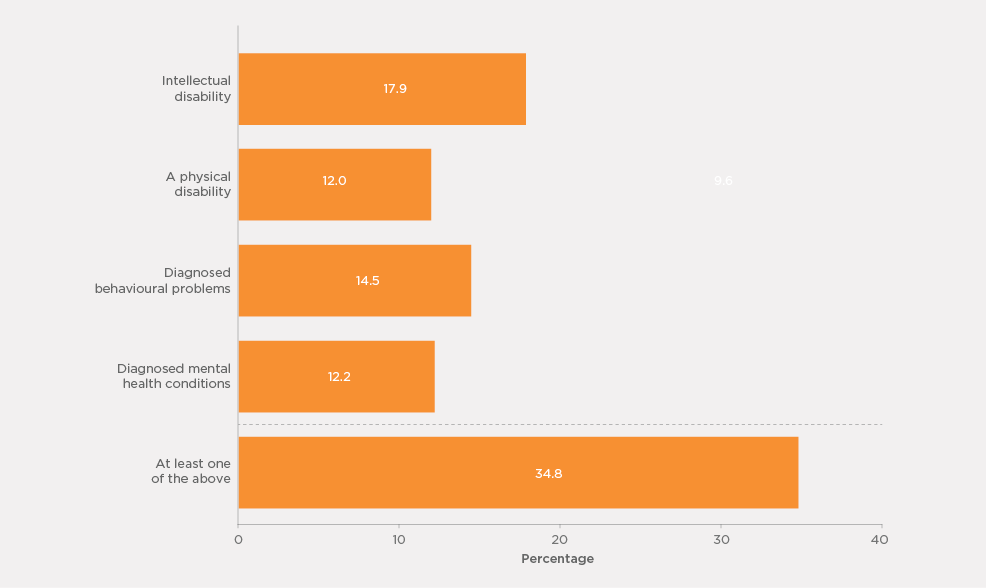

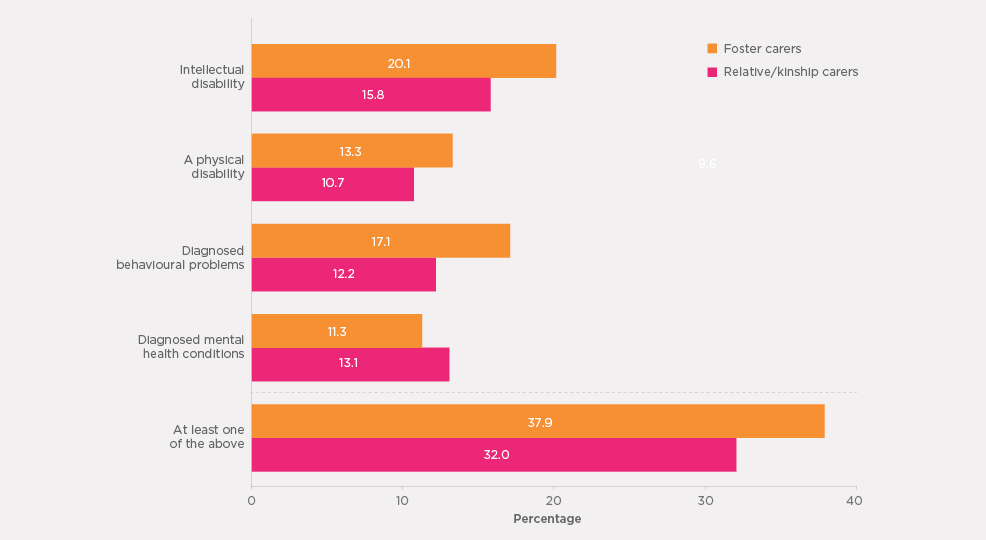

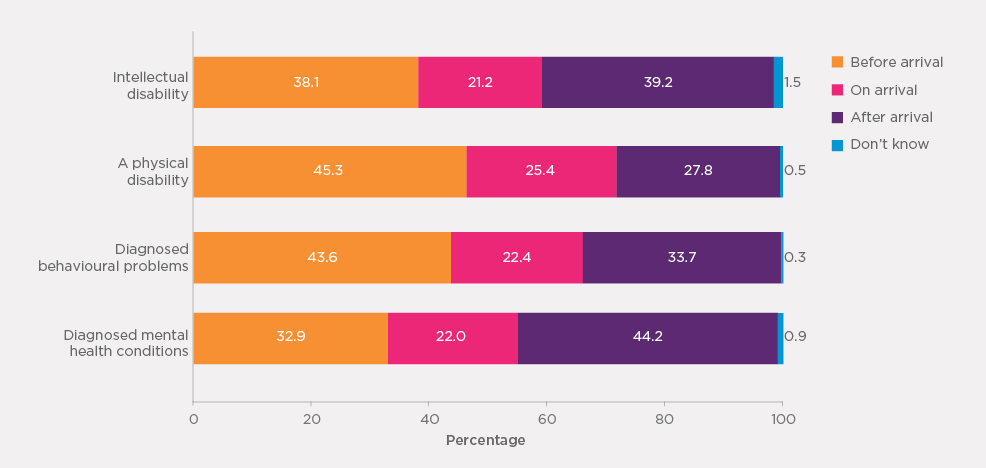

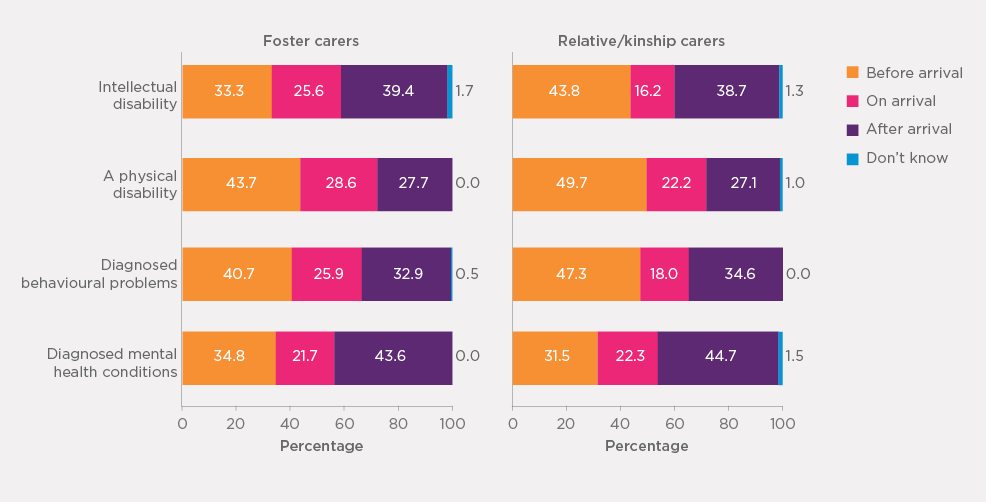

One-third of carers also reported that the study child had been diagnosed with at least one type of developmental condition - intellectual disability, a physical disability, diagnosed behavioural problems, or diagnosed mental health conditions. The most commonly reported developmental conditions were intellectual disabilities (18%) and behavioural problems (15%). Foster carers were more likely than relative/kinship carers to indicate that the study child had at least one of the four developmental conditions. In many cases, especially in regards to physical disabilities, carers were aware of these conditions prior to the study child coming to live with them, but it was also relatively common for the carer not to become aware of these conditions until or after the study child's arrival, and this was more apparent for foster carers than relative/kinship carers.

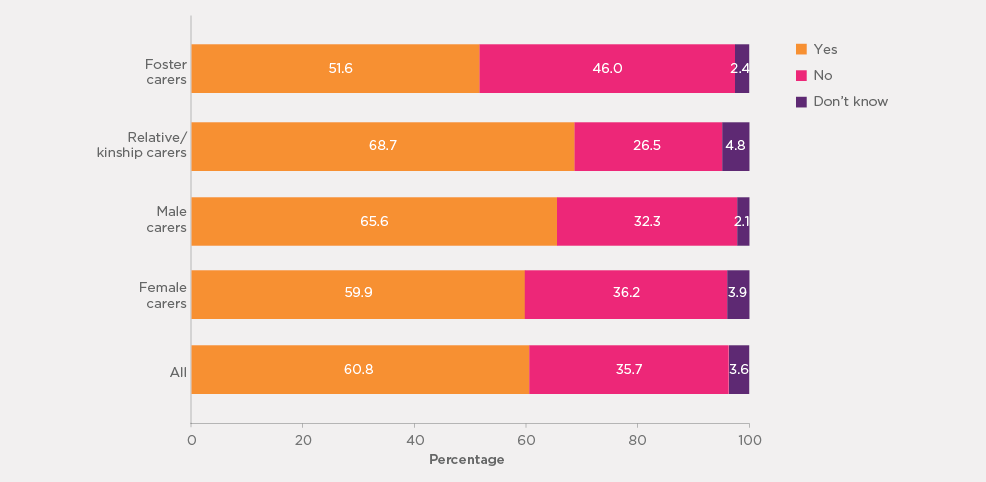

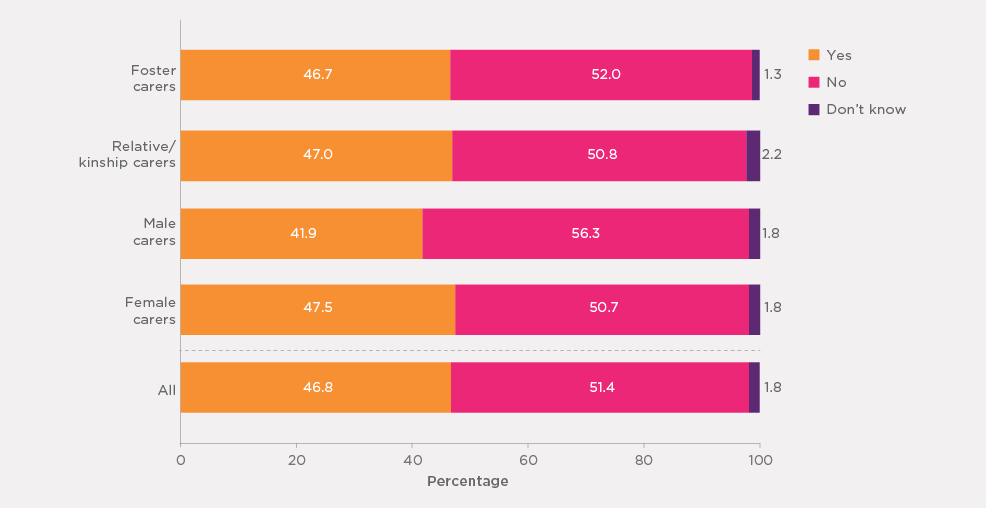

Overall, most carers (61%) reported that they were provided with adequate information about the study child's history before they came into their care, with relative/kinship carers being more likely than foster carers to believe this was the case (69% vs 52%). Importantly, however, more than one-third of carers reported that they were not provided with adequate information about the study child prior to their arrival, with this view being more prevalent for foster carers than for relative/kinship carers (46% vs 27%).

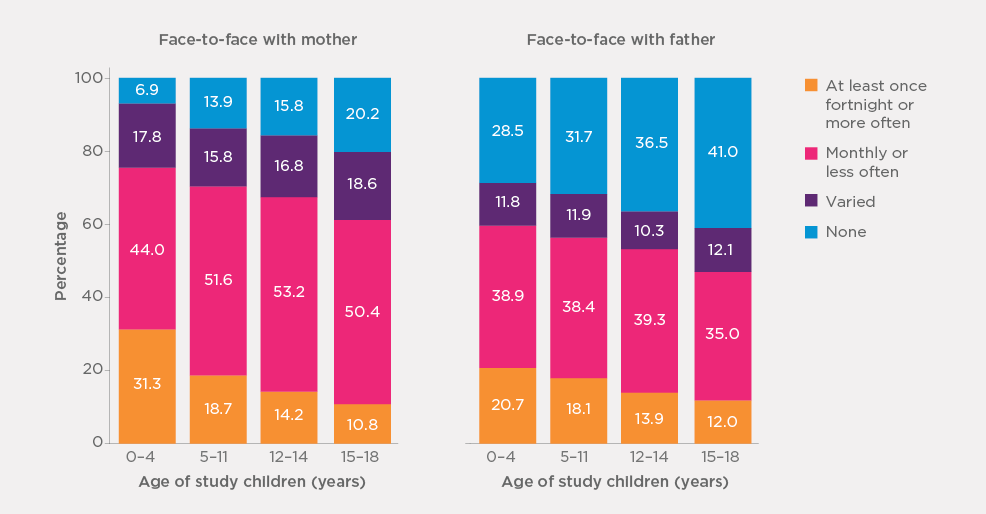

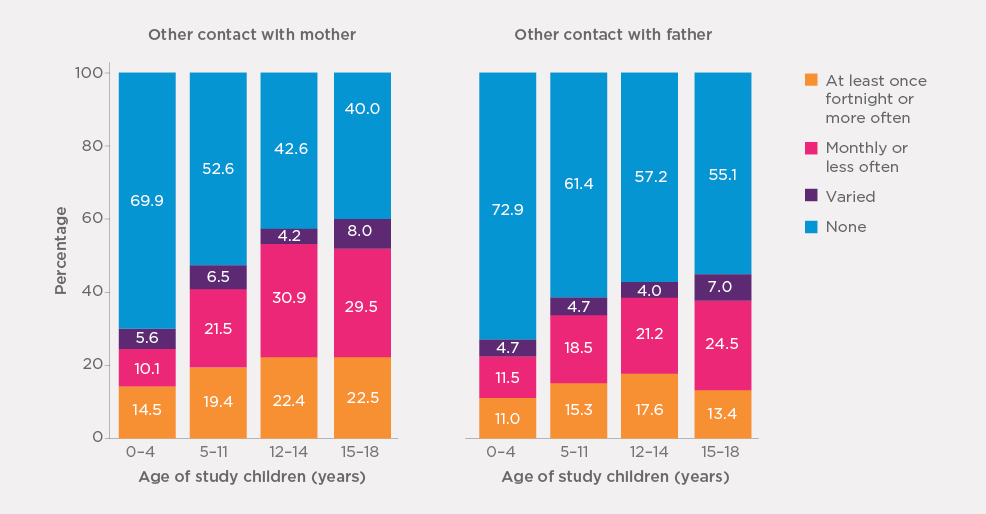

While a majority of the study children's birth parents were reported to remain alive, the degree and type of parental contact the children had varied. The study children had face-to-face contact less frequently with their father than their mother. One-third of study children had seen their mother at least once a month while less than one-fifth had seen their father at least once a month. Nearly one-third of study children had not seen their father in the past six months and over one-tenth did not see their mother. 2 Almost half of the study children had some degree of other contact with their mother, such as talking on the phone, emailing or contacting each other via social media, while just over a third of study children had this level of contact with their father.

Services and support

Access to support services

The vast majority of these carers (90%) had used at least one service for helping them look after the children who were placed in their care in the past, with over half (54%) having ever used three or more services over time. Over two-thirds of carers had received at least one type of services in the past six months. More than one-half of participating carers reported accessing carer support staff from their government child protection department and child counselling/psychologist services.

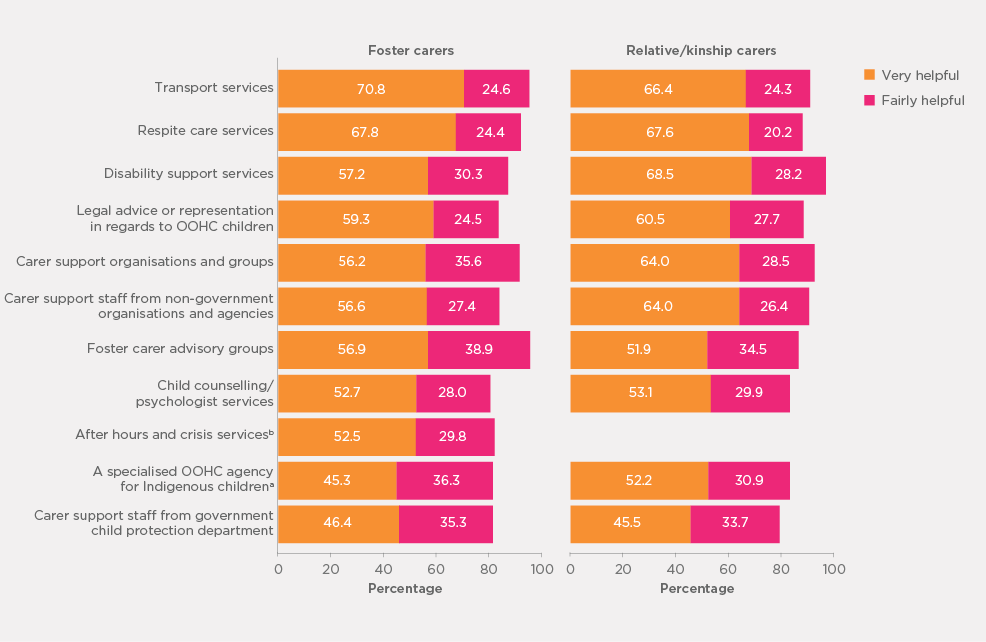

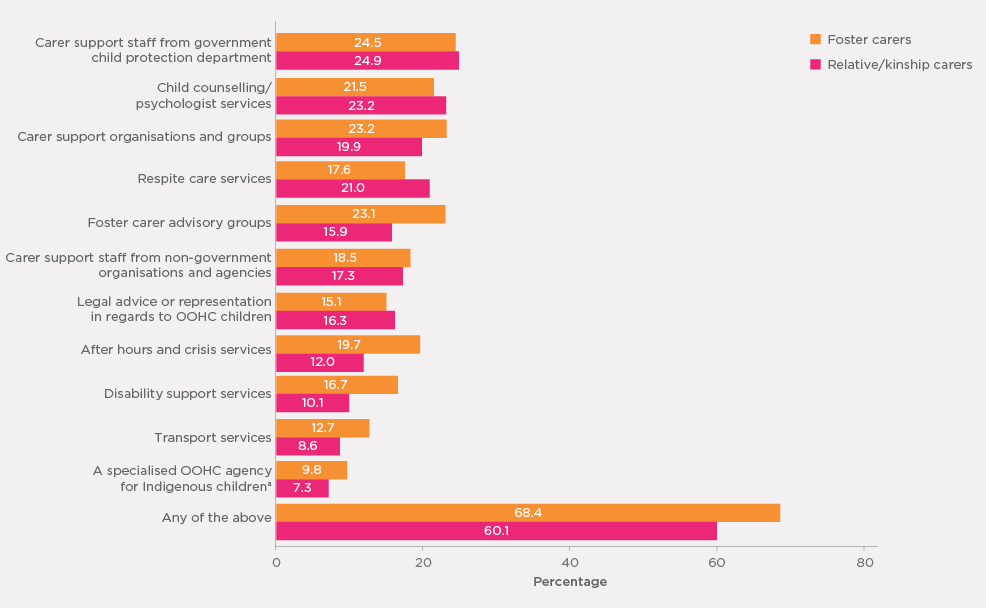

Overall, for most types of services, foster carers were more likely than relative/kinship carers to report having received support. Eight in ten foster carers had received at least one type of service support in the past six months. In contrast, less than six in ten relative/kinship carers had received at least one type of service, meaning that four in ten relative/kinship carers had not received services in the past six months at the time of their interview. Overall, carers perceived the services they had received to be "very helpful" or "fairly helpful", with only a minority indicating that the services received were unhelpful.

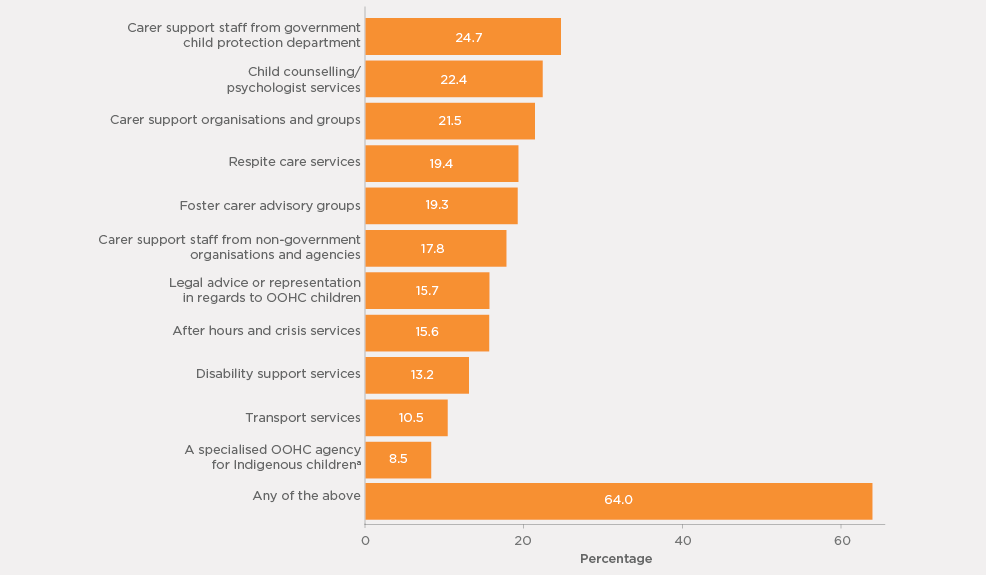

Overall, eight in ten carers reported that they currently required at least one service (regardless of whether they were currently using it). The number of carers who reported having current needs for at least one type of service was greater than the number of carers who reported having received at least one type of service in the past six months, demonstrating the extent of carers' needs for support. Indeed, two thirds of carers had one service need that was not met. Counselling/psychologist services were the most commonly nominated by carers as being currently needed, followed by carer support staff from a government child protection department, respite care services and carer support teams from non-government organisations and agencies. The analysis also revealed that substantial proportions of carers had current needs for these services but had not received the services in the past six months or never had. Almost half of the carers with a need for at least one type of services (nearly four in ten carers overall) said that they had some difficulty in getting the professional support they needed, with the most commonly reported barrier being long waiting lists/low support staff availability.

Training

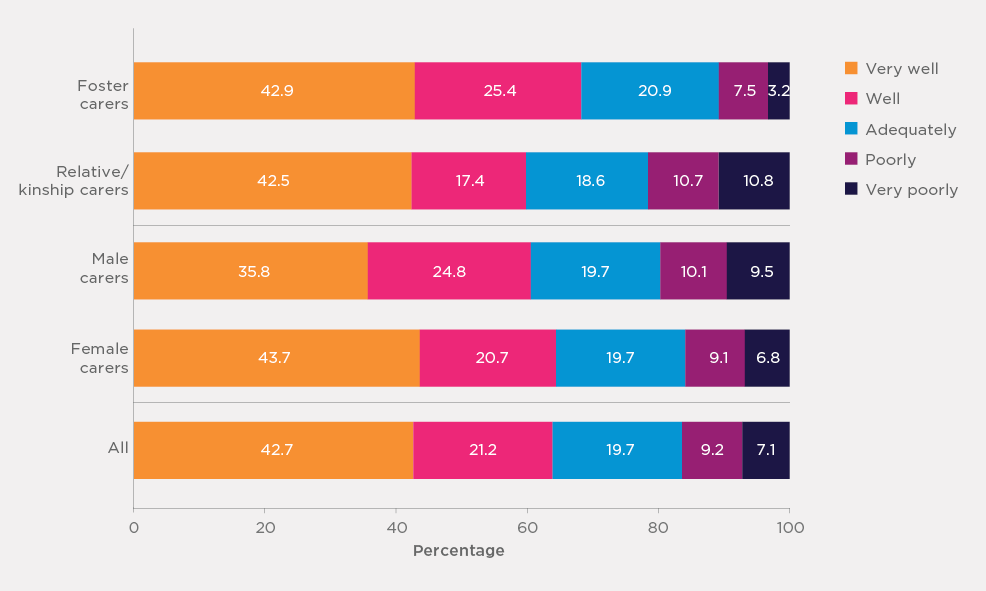

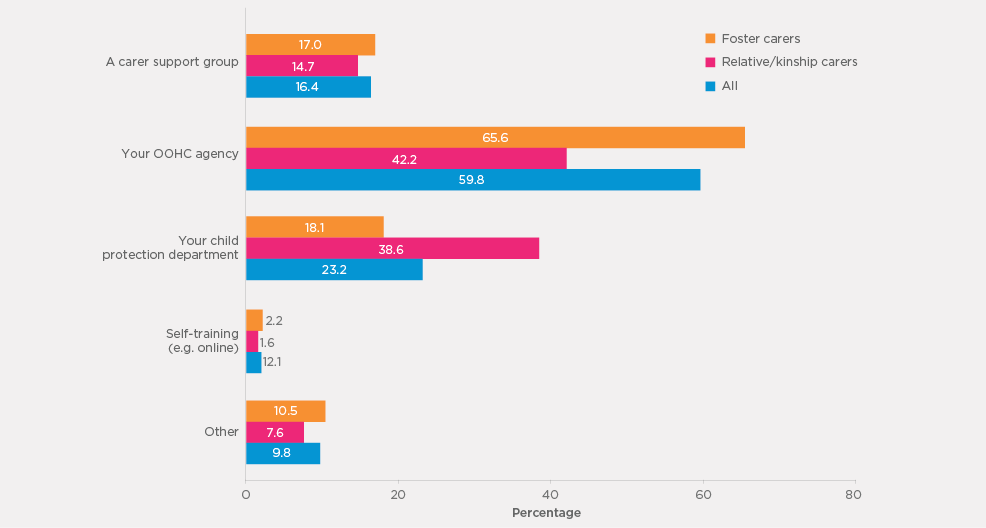

Participating carers were asked about how well prepared they felt for their caring role, with almost two-thirds indicating that they felt very well or well prepared. Almost two-thirds of carers also reported that they had attended some form of training course or workshop to assist them in their caring role, with 40% undertaking training in the past year.

There were, however, large differences between foster and relative/kinship carers in regards to training, with over nine in ten foster carers reporting that they had undertaken some form of training, in comparison to only just over a third of relative/kinship carers.

Among carers who had not attended any training, views were mixed about whether it would have been helpful to do so, particularly among relative/kinship carers. Together, these data suggest that relative/kinship carers may have less access to training than foster carers and that when training opportunities arise, relative/kinship carers may be taking them up less frequently than foster carers.

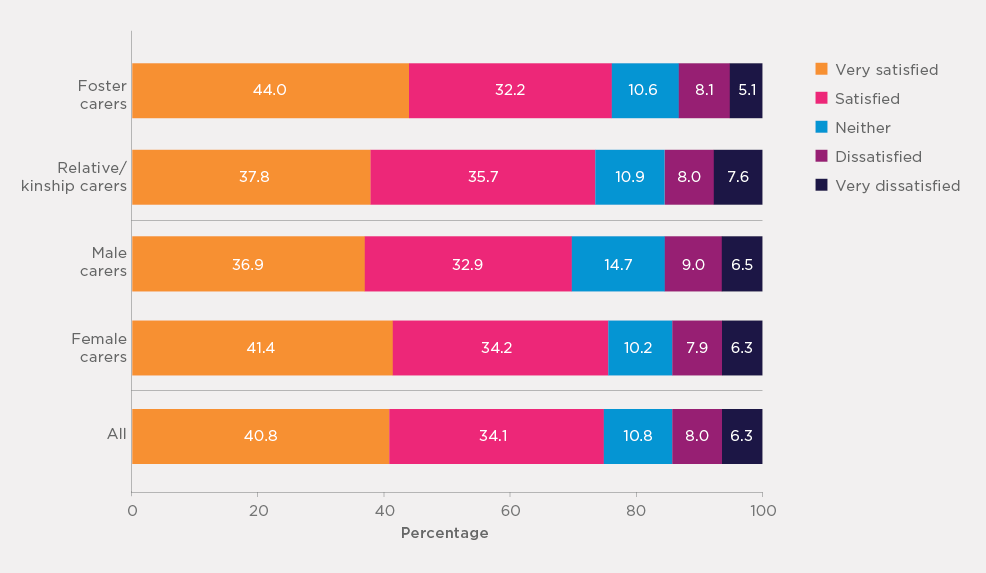

Contact with caseworker/carer support worker and other carer families

While the majority of carers were in contact with a caseworker/carer support worker at least once a month, foster carers tended to have more frequent contact than relative/kinship carers. For relative/kinship carers, their caseworker/carer support worker was most likely to be from a government department, while for foster carers, they were equally likely to be from a non-government organisation as a government department. Overall, carers were satisfied with the advice or assistance they received from their caseworker/carer support worker in regards to their most recent contact.

Just under one-half reported that they had met other carer families through a carer support group or on a social basis, but foster carers were much more likely to report this type of contact than relative/kinship carers.

Rewards and challenges

Most carers (i.e., over 90%) strongly agreed/agreed that they could make a positive difference in the life of a child in care, that they could provide the child with a positive family experience, and that it was a rewarding experience to care for these children. Nevertheless, carers also revealed the significant challenges they had faced in carrying out their caring role. Nearly one-half agreed that caring for children in out-of-home care was stressful, and an even higher proportion agreed that it was difficult to manage their behaviours, and that these children required more time or effort than other children of the same age.

Approximately one-half of carers agreed that the allowances received for the study child were adequate and that they were well supported by agencies/services. However, nearly one-quarter of carers felt that allowances were inadequate to care for the study child and three in ten did not feel well supported by agencies/services in meeting the study child's needs. This dissatisfaction was more prevalent among relative/kinship carers than foster carers, and was particularly evident among carers looking after the study children who had experienced or were exposed to at least four types of abuse/violence/neglect.

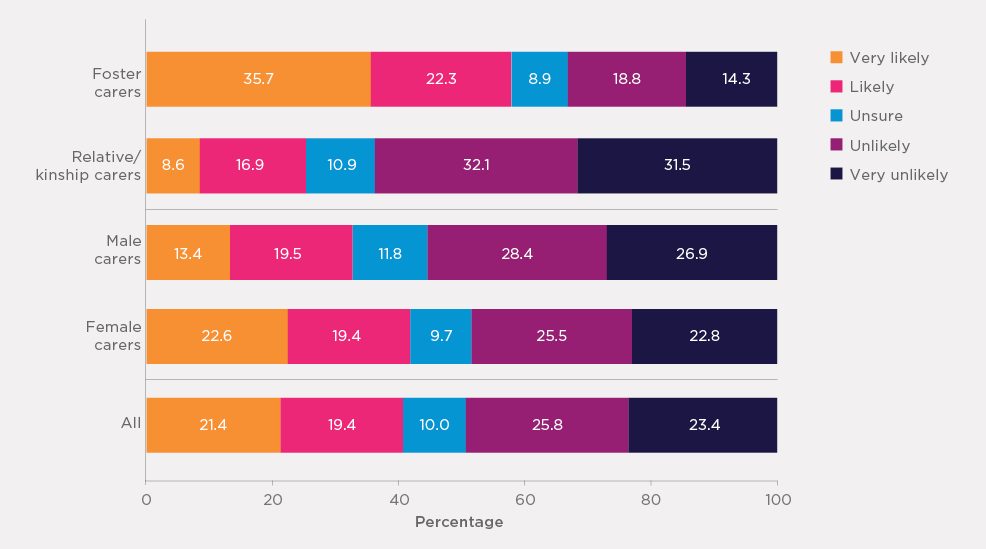

Although carers had a strong sense of reward, nearly one-half reported that they were unlikely or very unlikely to care for another child in the future, with relative/kinship carers being more likely than foster carers to express this view. Carers reporting higher levels of care challenges and a lack of support were also less likely to be a carer again.

Carer wellbeing and family relationships

Overall, carers reported positively on their wellbeing and family relationships. The majority of carers rated their health as "excellent" or "very good", with relatively high levels of vitality and mental health. While the majority of carers were highly satisfied with their life, some carers fared less well. Male carers rated more poorly than female carers on their general health, and male carers were also less satisfied with life, and less satisfied with family relationships. Relative/kinship carers also rated less well on their general health compared to foster carers and almost one in four relative/kinship carer had a disability or medical condition that was likely to last for six months or more.

Although relative/kinship carers provided lower ratings of life satisfaction when compared to foster carers, they were more satisfied with their own relationship with the study child, their partner's relationship with the study child, and how the study child got along with the other children in the household. This is likely to reflect the established relationships and bond with the study child.

Significant care challenges and lack of support were found to be associated with poorer carer wellbeing and family relationships for carers.

Conclusion

This report has examined the characteristics of foster and relative/kinship carers and of study children, together with carers' experiences of the circumstances relating to how the study children came into their care and their experience of service use, support and training received in carrying out their caring role. It has also examined the rewards and challenges of being a carer and the wellbeing of carers and their family relationships, including those concerning the study children, and the link between their wellbeing and family relationships and their care experiences.

Overall, while many carers reported that they were coping well in their caring roles despite the challenging circumstances and complexities associated with caring for a child in an out-of-home-care placement, this study identified that there is the need to better inform and prepare carers for their role and to provide more support while children are in their care, given the variety of needs that are likely to emerge over time. While service provision and support clearly remains important for both foster and relative/kinship carers, the findings suggest that more may be required to assist relative/kinship carers in particular, in order to increase availability and their participation in and/or uptake of services/training. The results from this study also highlight positives emerging from the caring experience, with carers reporting that they could make a real difference to a child's life and that they find being a carer a rewarding undertaking.

1 Note that in New South Wales the OOHC system includes NGOs, and these NGOs drew the samples following the same procedure but with the care type undefined.

2 The survey did not ask about the study child's prior maltreatments associated with parents and it is not possible to assess whether the lack of contact for some study children was linked with such a history.

1. Introduction

This report presents important findings from the Working Together to Care for Kids Survey (WTCKS), a collaborative project between the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS). The primary objective of this survey is to better understand the characteristics and needs of the foster and relative/kinship carers of the vulnerable children who are living in out-of-home care in Australia. These findings can be used to better inform government policies and practices in support of these carers.

AIFS designed, developed and implemented a national survey, in consultation with DSS, as well as the study's working group that included at least one representative from each jurisdiction. The survey was conducted during September and November 2016 and entailed telephone interviews with 2,203 foster and relative/kinship carers.3 This section first provides some background against which the study was conducted and then outlines the structure of this report.

1.1 Background

There are significant numbers of Australian children who live in out-of-home care. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), in their annual publication on child protection data, there were 46,448 children aged 0-17 years who were in out-of-home care (representing 8.6 per 1,000 Australian children) at 30 June 2016, compared to 37,648 children at 30 June 2011 (representing 7.3 per 1,000 children) (AIHW, 2017, 2012). The majority of the children at 30 June 2016 were living with foster or relative/kinship carers in home-based care arrangements: 39% in foster care, 49% in relative/kinship care (AIHW, 2017).4

The current study focuses on these two groups of formal carers: foster and relative/kinship carers. These carers have formal care arrangements that involve some form of legal or statutory child protection intervention, whereas informal care may occur in circumstances where a private arrangement is made without legal or statutory child protection intervention. Although the Australian jurisdictions vary in how these care types are defined and governed, they can broadly be described as follows:

Relative or kinship care involves placing a child or young person with a relative or someone they already know. A relative/kinship carer could be any of the following: a biological relative of the child; a person who is not a biologically related but who has a legal, social or other relationship with the child and/or birth parent(s); and/or a person from the child's or family's community (in accordance with their culture) (AIHW, 2017). In Indigenous communities, "kin" may also be someone who shares a cultural connection with the child (Bromfield & Osborn, 2007). While there may be a preference for out-of-home-care children to be placed with a family member or someone close to them whenever possible (i.e., in a relative/kinship care placement), sometimes this is not possible. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care are to be placed according to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle developed over three decades ago, which was designed to place children with carers who can maintain their familial, cultural and community connection. Nevertheless, Arney, Iannos, Chong, McDougall, and Parkinson (2015) found that the Principle guided only a minority of placements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Foster care is where a family or an individual care for other people's children in their own home and the caregiver is authorised by the state or territory to look after the children. Although the specific requirements to be a carer vary between jurisdictions, prospective carers must complete an assessment/accreditation process in order to be formally recognised as a foster carer in their jurisdiction and thereby be eligible to care for a child. For both foster care and relative/kinship care, the caregiver may be financially reimbursed (or offered financial reimbursement but decline the offer) by their state or territory (AIHW, 2017).

Much of the research on carers who look after children in out-of-home care focuses on specific states or territories. Rosier and Hunter (2016), in their audit review of research and evaluation projects on child protection between 2011 and 2015, observed that research in child protection, including that with a focus on carers, tended to be qualitative and based on small sample sizes. Indeed, more than half of the research projects between 2011 and 2015, and the majority of studies conducted earlier, were based on sample sizes fewer than 100. A study with a nationally representative and relatively large sample of carers was needed to provide a national picture of carers and understand their care experiences and needs.

The available research on foster and relative/kinship carers has highlighted a number of important issues, both in regards to the differences between these two types of carers, as well as their general views of and experiences within their caring role. An important point to note is that the perceptions and expectations of the role of carers of out-of-home-care children can vary considerably between various stakeholders - including government departments, child protection workers, the children in out-of-home care, the community in general, and carers themselves (Blythe, Halcomb, Wilkes, & Jackson, 2013). This can potentially make intervention or assistance difficult.

It has been reported that there is ambiguity about the role of the foster carer in the Australian community. The ambiguity is at least in part due to the complexity of the child protection system, including that it is administrated by government and non-government (NGO) organisations and also governed by legislation, policies and protocols that vary between each state and territory. And while there can be significant disagreement between foster carers themselves regarding their role, Blythe et al. (2013) found that female foster carers tended to perceive themselves as mothers to the long-term foster children in their care, but as foster carers for children in their short-term care. Furthermore, Schofield, Beek, Ward, and Biggart (2013) differentiated between foster carers who were able to move flexibly between being both a professional carer and a parent to a child in out-of-home care and others who struggled to manage different role expectations and demands; this again highlights the different ways in which carers can perceive their role and also the potential for this to change over time as well as issues related to the professional-personal structure of the carer role.

The foster care literature has indicated a number of challenges associated with fostering. For example, there can be emotional and psychological difficulties, particularly in regards to attachment issues with foster children after they have transitioned from their care (e.g., to a permanent placement or to be reunified with their birth parents). In addition, the complex needs and behavioural issues that are often associated with children in out-of-home care can have a negative impact on carers and their families. Some foster carers have also indicated that the role has placed them under financial strain, due to factors such as a lower capacity to engage in paid employment and inadequate state reimbursement (McHugh, 2006; Wilks & Wise, 2011). A survey conducted by Wilks and Wise (2011) of foster carers in Victoria also found a proportion of carers identified "system challenges" as a barrier in their caring roles, such as insufficient agency/department support and their frustration with the system.

On the other hand, foster carers have identified a number of rewards associated with fostering. These include feeling that they are making a difference in children's lives and seeing children in out-of-home care respond well to living in a safe and secure home. Furthermore, foster carers often view the role as an opportunity to "give back" and make a difference to the community, and may gain purpose and personal fulfilment as a result of doing so. There can also be a positive impact on the wider fostering family, by drawing its members closer together and encouraging growth and maturation in carers' birth children (McHugh et al., 2004; Wilks & Wise, 2011).

Research on relative/kinship carers indicates that economic disadvantage, stress, health issues and a lack of resources are issues commonly faced by relative/kinship carers (Bromfield, Higgins, Higgins, & Richardson, 2007; Dunne & Kettler, 2006). Economic disadvantage in relative/kinship families compared to foster care families has been consistently found in the literature - this is likely to be at least partly due to a higher proportion of relative/kinship carers being single parents and/or older. It has been suggested that these issues can negatively affect the caring capacity of these carers, in conjunction with the various and complex needs of the children in their care and managing family relationships (including with birth parents). Hence, it is important that support, interventions and training cater to the individual needs of relative/kinship carers. This could be achieved through consulting with carers and improving communication between carers and the relevant service professionals (Portengen & van der Neut, 1999; Waldman & Wheal, 1999; cf. Dunne & Kettler, 2006; Golding, 2004).

In addition, an Australian study of grandparent relative/kinship carers, which involved interviews with 55 service providers and policy-makers from New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory, found that these carers are often lacking the timely and accessible information and support they require (valentine, Jenkins, Brennan, & Cass, 2013). The study concluded that this may impact on both their material and emotional wellbeing.

There is also some research evidence to suggest that carers are able to cope better with the demands of caring with appropriate service support. For example, data from a UK study of adolescents in foster care indicated that the levels of strain experienced by foster carers can be mitigated by enhanced support; for example, the regular availability of and assistance provided by the child's caseworker (Farmer, Lipscombe, & Moyers, 2005). Training may also be an important factor for carers, both initially and ongoing, to ensure that carers' expectations are managed and they feel equipped for their caring roles (Randle, Ernst, Leisch, & Dolnicar, 2016). For example, the results from a British study of foster carers found that those who undertook a counselling skills training course had greater confidence in their ability to look after children's mental health and emotional needs (Mosuro, Malcolm, & Guishard-Pine, 2014).

Current research on carers of out-of-home-care children indicates that both foster and relative/kinship carers have different and somewhat complex needs, which may not always be consistently met from a service provision and training perspective. A national study that investigates aspects such as their support needs, and their views and experiences, has been lacking. Australia, like many countries in the Western world, has been experiencing difficulties with the recruitment and retention of carers, and is increasingly reliant on older carers and former carers (Wilks & Wise, 2011). It is important to gain a greater understanding of what motivates these individuals to become carers and what could be done to better support them in their roles. Recognising the significant role that the carers play in shaping the lives and development of children in care, the Second Action Plan 2012-2015 of the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020 (National Framework) (DSS, 2011, p. 6) stated:

The provision of support that is timely and responsive to the needs of carers and the children and young people they are caring for, and ongoing quality training and development, will help carers deliver the best care possible in often complex or challenging circumstances.

Meeting carers' support needs is now part of the national standards for improving the quality of care to children and younger people in care. In this context, the current study was conducted to better understand their needs, thoughts and motivations and, ultimately, enable support to be better targeted to these individuals.

1.2 Structure of this report

The next section outlines the methodology of the survey. Section 3 depicts characteristics of foster and relative/kinship carers. Circumstances surrounding the time that children in out-of-home care came to the carer's households are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 focuses on carers' experience of service support and training support. The two following sections (6 and 7) examine carers' views on motivations and challenges in providing their care to the vulnerable children and their wellbeing. The final section summarises the key findings of this report.

This report aims to provide a national picture of foster and relative/kinship carers of children in out-of-home care and bring together the multiple and complex challenges carers face, including those around services. This report does not provide findings at state and territory levels, given all the differences in carer services between states/territories such as child protection legislation, service eligibility and provision models.

3 Responding carers were from all of the Australian states and territories, with the exception of the Northern Territory.

4 There is some limitation in data comparability due to differences in the definition of placement types and reporting between states and territories, see Figure 5.3, AIHW (2017), pp.50 & 65.

2. Methodology

This study focuses on formal carers (foster and relative/kinship) who look after one or more out-of-home-care child under 18 years of age in their household. The sample of the study was drawn from carer registration databases across the states and territories (i.e., jurisdictions). This section outlines the target population on which the sample was based, sampling procedures, data collection, questionnaire design and fieldwork outcomes. It also outlines the data weighting procedures for the final sample to adjust for differential probability of sample selection.

2.1 The study population and sample

The population for this study was foster and relative/kinship carers who were registered as formal carers in state and territory departments responsible for child protection across Australia and had at least one child under 18 years of age in out-of-home care who was living with them at 31 December 2015. The population definition applied to all jurisdictions except the Northern Territory (the Northern Territory did not participate in the survey due to some legislative and administrative barriers.)

The sample selection process involved engaging with the study's Working Group representatives from each of the participating jurisdictions. Sample selection was household-based and stratified by jurisdiction and care type (foster carer households and relative/kinship carer households). The main sample process in the jurisdictions (except the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Tasmania) involved a randomly extracted sample from foster care and relative/kinship households at a ratio of seven in every ten of these carer households in their database. In New South Wales (NSW), the out-of-home-care system includes non-government organisations (NGOs), which drew samples using the same procedure but with the care type undefined. Given their small carer populations, all foster and relative/kinship households in the ACT and Tasmania were selected.

Each jurisdiction then sent a letter, in early to mid 2016, to the primary carers within the selected households informing them that their contact details may be divulged to a reputable research fieldwork agency for this study, and providing them with the opportunity to contact their jurisdiction within a specified time frame if they did not wish to be contacted for the study. A flyer outlining the purpose and other aspects of the study was sent with the letter. The proportion of carers who contacted their jurisdiction to advise that they did not wish to be contacted for the study was 2-4% across the four jurisdictions that provided this information.5

The sampling process was implemented slightly differently in Victoria due to the administrative requirements and privacy legislation in place in this jurisdiction; the main variation was that the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Victoria, directly approached the carers and this was done by the selected fieldwork company (the Social Research Centre) on behalf of DHHS.

2.2 The survey content domains

The survey went through an extensive developmental process, which involved the research team at AIFS, DSS representatives and the Working Group, as well as the fieldwork company, the Social Research Centre (SRC), at the programming stage. The final survey instrument that was programmed for the main studies was comprised of the following modules:

Introduction (confirming who the qualifying respondent carer might be):

Screening (ascertaining the number of children currently in out-of-home care in the household and/or in care within the past six months);

Section A: The child in out-of-home care and household composition;

Section B: The carer's caring experience and child wellbeing;

Section C: Services and supports;

Section D: Motivations and challenges;

Section E: Carer wellbeing and family relationships; and

Section F: Demographics.

2.3 The fieldwork

The pilot study for the WTCKS was conducted in early August 2016 to test the survey questions and length as well as the effectiveness of the survey instrument. A total of 105 pilot interviews were completed, which led to further improvement in the instrument such as the clarity of some questions and survey flow. The main fieldwork period began in early September 2016 and concluded in early November 2016.

Carers who no longer had a child currently in their care as part of the out-of-home-care system but had done so in the past six months could still be considered in-scope for the survey. Carer interviews were terminated if it was discovered the respondent had not been a formally registered primary carer of at least one child aged under 18 (in either a foster or relative/kinship care arrangement) in the past six months. This was due to the consideration of difficulties in recalling information about the child and other information such as service use if the child had left more than six months ago. If the respondent had cared for more than one child in the past six months, a random selection process was applied to identify a "study child", who would be the reference child for several questions throughout the survey. This meant that the age of each child was recorded and one was selected at random, with preference given to the child/children who were currently in care, if applicable.

The SRC made contact with 5,275 carers. The final sample size was 2,203 interviews, representing 42% of the selected sample members. The numbers of interviews across participating jurisdictions by care type are shown in Table 2.1. A relatively small proportion (n = 151 or 7%) of interviews were conducted with carers who did not currently have a child in their care. The average interview duration was 33 minutes.

| Strata | Final achieved interviews n (%) |

|---|---|

| NSW NGO* | 411 (18.7) |

| NSW Kinship | 384 (17.4) |

| NSW Foster | 236 (10.7) |

| NSW total | 1,031 (46.8) |

| Vic. Kinship | 266 (12.1) |

| Vic. Foster | 154 (7.0) |

| Vic. total | 420 (19.1) |

| Qld Kinship | 128 (5.8) |

| Qld Foster | 235 (10.7) |

| Qld total | 363 (16.5) |

| SA Kinship | 76 (3.4) |

| SA Foster | 65 (3.0) |

| SA total | 141 (6.4) |

| WA Kinship | 102 (4.6) |

| WA Foster | 73 (3.3) |

| WA total | 175 (7.9) |

| Tas. Kinship | 20 (00.9) |

| Tas. Foster | 20 (0.9) |

| Tas. Total | 40 (1.8) |

| ACT Kinship | 20 (0.9) |

| ACT Foster | 13 (0.6) |

| ACT total | 33 (1.5) |

| Total | 2,203 (100) |

Note: * The care type was unavailable for responding carers from NSW NGOs. The care type was derived based on the carer's relationship to the child in out-of-home care.

Table 2.2 shows the details of call outcomes. The number of refusals was small. The numbers not leading to an interview were typically due to non-contacts (e.g., no answer, answering machines or disconnected phone services).

| Call outcome | n (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews | 2,203 (42) | |

| Refusals | 319 (6) | |

| Appointments | 177 (3) | Appointments were made but did not lead to actual interviews. |

| Out-of-scope* | 126 (2) | Predominantly involved sample members who had not been caring for a child in a foster or relative/ kinship care placement within the past six months. |

| Non-contacts** | 1,507 (29) | Predominantly involved calls where there was no answer or the call went straight to an answering machine. |

| Unusable sample*** | 873 (17) | Of the unusable sample, 75% (n = 657) involved the number being disconnected/receiving a Telstra message. |

| Other**** | 70 (1) | Predominantly involved the carer identifying a LOTE (Language other than English) as their first language. |

| Total initiated sample | 5,275 (100) |

The cooperation rate is another way of considering response rate. Based on the known call outcomes, it is defined as the total number of interviews as a proportion of the total number of interviews plus all refusals. The cooperation rate for the main data collection was 87%. Table 2.3 shows that the cooperation rate varied somewhat across the stratification criteria of carer type and jurisdiction, with the main difference being the higher cooperation rate for Tasmania, which is likely due to its small sample size. The cooperation rate was also slightly higher in foster carer and NGO households in comparison to relative/kinship carer households.

| Stratification variable | Interviews (n) | Refusals (n) | Cooperation rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carer type | |||

| Relative/kinship | 996 | 179 | 85 |

| Foster | 796 | 90 | 90 |

| NGO | 411 | 50 | 89 |

| Jurisdiction | |||

| NSW | 1,031 | 142 | 88 |

| Vic. | 420 | 59 | 88 |

| Qld | 363 | 60 | 86 |

| SA | 141 | 22 | 87 |

| WA | 175 | 29 | 86 |

| Tas. | 40 | 1 | 98 |

| ACT | 33 | 6 | 85 |

| Total | 2,203 | 319 | 87 |

2.4 Data weighting

As described above, the cooperation rates varied across the participating jurisdictions and care types. A data weighting procedure was applied in an attempt to adjust for differential responses and differential coverage (e.g., oversampling of small jurisdictions). Jurisdiction, care type (foster care, relative/kinship care, care type unspecified) and SEIFA Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (quintiles) were used in the final weighting. The results of logistic regression of having a completed interview with three variables (jurisdiction, care type and quintile of the index of relative socio-economic disadvantage) suggest that the three variables were linked with the likelihood of participation in the study. For example, carers in the top quintile of the index of relative socio-economic disadvantage were more likely than those in the bottom quintile to participate in the study.6

Survey weights were computed using the ipfweight algorithm (also known as iterative proportional fitting or raking) in Stata (Mannheim).7 This procedure performs a stepwise adjustment of survey sampling weights to achieve known population margins. The computed weights ranged from 0.7 to 1.79.

5 The data on the extent to which carers did not wish to be part of the study for ACT, NSW and Vic. were not available. For NSW, the NGOs sent out the letters but accurate/complete information could not be traced back.

6 While other variables such as age and gender may be important for data weighting, the variables were not provided by all the participating jurisdictions.

7 See <ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457353.html> for further information. Retrieved 9/1/2017.

3. Characteristics of carers

This section focuses on the demographic characteristics of the carers who participated in the survey, including their financial circumstances. Data on the number and age of children in care is also provided.

3.1 Care type and gender of carers

For the purpose of survey stratification, care type as reported by jurisdictions was used. However, respondents who were recruited from the database of NGOs did not have a care type. A small number of respondents (n = 20) were interviewed but not originally listed as a primary carer of children in the household.

For these reasons, care type in this report was derived according to the respondent's report of their relationship with the study child.8

As shown in Figure 3.1:

- forty-seven per cent were foster carers; and

- fifty-three per cent were relative/kinship carers.

The distribution of the two groups of carers in the study is similar to the data of out-of-home care reported by AIHW. AIHW (2015) suggests that of carer households with a placement during 2012-13, 47% were foster carer households and 53% were relative/kinship carer households.

Among relative/kinship carers:

- the majority (66%) were grandparents to the study child in their care (including a small number of great-grandparents);

- twenty-seven per cent were uncles or aunties to the study child; and

- the remainder (7%) were other relatives (e.g., cousins, siblings and so on). (These results are not shown in Figure 3.1.)

The great majority of carers (88%) were female, and only 12% were male. Gender distributions were similar between the two types of carers, with 12% of males among foster carers and 13% among the relative/kinship group.

The distributions of foster and relative/kinship carers were similar between men and women:

- Forty-five per cent of male carers and 48% of female carers were foster carers.

- Relative/kinship carers accounted for 55% and 42% of male and female carers respectively. (These results are not shown in Figure 3.1.)

Figure 3.1: Carers by care type and by gender

Note: Percentages are based on weighted data.

3.2 Children in out-of-home care

Table 3.1 shows the age and gender of study children as well as the number of children in out-of-home care that carers were looking after at the time of interview and in the six months prior to the interview.

- The mean age of study children was 9 years old.

- The most common age group of study children was 5-11 years (44%), followed by under five years (23%).

- Eighteen per cent were 12-14 years and 15% were 15-18 years.9

- The mean ages of study children for the two groups of carers were similar.

- There were slightly more boys than girls among study children (52% vs 48%), and this pattern applied to both groups of carers.

- The mean age of study children cared for by male carers was older than that of study children with female carers. For example, 18% of study children looked after by male carers were 15 years old and over, compared to 14% of those children in the care of female carers, while 24% of study children in the care of female carers were under five years, compared to 17% among those who were looked after by male carers.

The distributions of the number of children in out-of-home care who were looked after by carers at the time of interview and in the six months prior to the interview were broadly similar, with one child being the most common.

- At the time of interview, just under one-half of carers looked after one child in out-of-home care (45%) and just over one-quarter (27%) had two children in their care. One-fifth (22%) of carers had three or more children and a small proportion (7%) reported that a child had left within the past six months and they did not have any children in out-of-home care who were living with them at the time of interview.

- Relative/kinship carers were more likely to have one child in their care compared with foster carers (50% vs 37% at the time of interview). Conversely, multiple children in out-of-home care were more common among foster carers than they were for relative/kinship carers.

- Formally caring for a large number of children in out-of-home care (four or more) was slightly more common for female carers than for male carers (10% vs 7%) and the proportion of children who had left was slightly higher for male carers than for female carers (8% vs 7%). Nevertheless, the broader patterns were similar between male and female carers.

| Care type | Carer's gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster carers (%) | Relative/kinship carers (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | All a (%) | ||

| Age of study child | ||||||

| 0-4 | 22.8 | 23.4 | 17.2 | 24.0 | 23.1 | |

| 5-11 | 42.5 | 46.1 | 47.2 | 44.0 | 44.4 | |

| 12-14 | 19.1 | 16.3 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 17.7 | |

| 15-18 | 15.6 | 14.1 | 18.2 | 14.3 | 14.8 | |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Mean | 9.0 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 8.8* | 8.9 | |

| SD | (5.2) | (4.3) | (4.6) | 4.8 | 4.8 | |

| Gender of study child | ||||||

| Boys | 52.9 | 50.6 | 56.1 | 51.0 | 51.6 | |

| Girls | 47.1 | 49.4 | 43.9 | 49.0 | 48.4 | |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Whether study child is indigenous | ||||||

| Yes | 30.7 | 31.9 | 30.2 | 31.6 | 31.4 | |

| No | 69.3 | 68.1 | 69.8 | 68.4 | 68.6 | |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Number of children in out-of-home care currently in household | *** | *** | ||||

| 0 | 7.8 | 6.0 | 8.2 | 6.6 | 6.8 | |

| 1 | 38.6 | 50.1 | 45.3 | 44.5 | 44.6 | |

| 2 | 28.2 | 25.8 | 26.0 | 27.1 | 26.9 | |

| 3 | 13.7 | 11.3 | 14.9 | 12.1 | 12.5 | |

| 4+ | 11.7 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 9.6 | 9.1 | |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Number of children in out-of-home care in household currently and in last 6 months | *** | *** | ||||

| 1 | 34.1 | 49.4 | 45.3 | 41.6 | 42.1 | |

| 2 | 27.5 | 28.9 | 28.0 | 28.2 | 28.2 | |

| 3 | 17.9 | 13.0 | 17.3 | 15.0 | 15.3 | |

| 4+ | 20.6 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 15.1 | 14.4 | |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Number of carers b | 1,196 | 1,005 | 267 | 1,935 | 2,203 | |

Notes: Percentages and means are based on weighted data and sample sizes on unweighted data. For each variable relating to the children, a design-based chi-square test was used to assess statistically significant difference between foster carers and relative/kinship carers, and between male and female carers (*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding. a Includes carers whose care type couldn't be ascertained or gender was missing. b Sample sizes varied slightly across variables due to non-responses to specific variables.

3.3 Selected characteristics of carers

The selected socio-demographic characteristics of carers are presented in Table 3.2).

- The mean age of carers was 53 years. Nearly one-half were 50-64 years old, and less than one-quarter were aged in their 40s. There were more carers who were aged 65 years or older than there were under 40 years old (15% vs 12%). It is also worth noting that 6% of carers were aged 70 years and over (data not shown in the table).

- The majority of carers (62%) were living with a partner.

- The proportion of carers who were Indigenous was 12%. Whereas the percentage of Indigenous people within the national population is 3%, based on the 2011 Census (ABS, 2013).

- One-half of carers did not have any post-school qualification and four in ten did not complete secondary school. Less than one-fifth had a degree or higher qualification, and one-third had another post-school qualification (i.e., lower than a degree).

- Of carers under 65 years old, more than one-half (56%) were not in paid work, and part-time employment was more common than full-time employment, with 25% and 19% in part-time and full-time employment, respectively.

Foster and relative/kinship carers differed in socio-demographic characteristics.

- Relative/kinship carers were older than foster carers (mean age: 54.5 years vs 51.4 years). Nearly one-fifth of relative/kinship carers were 65 years old or older, compared to one-tenth of foster carers. This reflects the fact that most relative/kinship carers were grandparents to the children in their care.

- Relative/kinship carers were less likely to live with a partner than foster carers (58% vs 67%).

- Relative/kinship carers were more likely than foster carers to be Indigenous (16% vs 8%), but slightly less likely to be born overseas (13% vs 17%).

- Lower educational attainments (i.e., non-completion of secondary school) were more common among relative/kinship carers than foster carers. This is partly due to the differential age profiles between the two groups - foster carers being younger, on average, by about three years. There was also a lower employment rate among relative/kinship carers aged under 65 years.

- There were also apparent differences between male and female carers in some characteristics.

- Male carers were older than female carers (54.7 years vs 52.8 years). The proportion of those who were aged 65 years and older was 21% among male carers, compared to 14% of female carers.

- Male carers had a higher level of education than female carers. For example, a higher proportion of male carers than female carers had a degree or higher qualification (23% vs 17%). The gender difference in education was not statistically significant, due to the small sample of male carers.

- Male carers under 65 years old were more likely than female carers to be employed (56% vs 43%), most commonly on a full-time basis (46% vs 16%).

- In addition, a higher proportion of male carers than female carers lived with a partner (77% vs 60%).

| Care type | Carer's gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster carers (%) | Relative/kinship carers (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | All a (%) | |

| Age | |||||

| Under 40 years | 11.5 | 12.5 | 10.8 | 12.2 | 12.1 |

| 40-49 | 31.8 | 16.0 | 17.4 | 24.4 | 23.5 |

| 50-64 | 46.0 | 52.4 | 51.4 | 49.0 | 49.3 |

| 65+ | 10.8 | 19.1 | 20.5 | 14.4 | 15.2 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Mean | 51.4 | 54.5*** | 54.7 | 52.8* | 53.0 |

| SD | 10.9 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 11.2 |

| Educational attainment | *** | ||||

| Degree+ | 24.7 | 11.5 | 23.2 | 17.0 | 17.7 |

| Other post-school qualification | 35.3 | 30.1 | 38.1 | 31.9 | 32.6 |

| Year 12 | 10.3 | 8.2 | 5.4 | 9.7 | 9.2 |

| Year 11 or lower | 29.8 | 50.2 | 33.3 | 41.4 | 40.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 |

| Employment status,carers aged under 65 years | *** | *** | |||

| Full time | 21.3 | 17.0 | 46.2 | 15.6 | 19.1 |

| Part time | 27.2 | 23.3 | 10.1 | 27.3 | 25.3 |

| Not employed | 51.5 | 59.7 | 43.7 | 57.1 | 55.5 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 |

| Whether living with a partner | *** | *** | |||

| Yes | 67.3 | 57.6 | 77.4 | 60.0 | 62.2 |

| No | 32.7 | 42.4 | 22.6 | 40.0 | 37.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 |

| Indigenous status | *** | ||||

| Indigenous | 7.7 | 15.8 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 12 |

| Non-indigenous | 92.3 | 84.2 | 89.9 | 87.7 | 88 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 |

| Country of birth | ns | ||||

| Australia | 82.7 | 86.6 | 84.9 | 84.7 | 84.8 |

| Overseas | 17.3 | 13.4 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 15.2 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 |

| Number of carers b | 1,196 | 1,004 | 267 | 1,935 | 2,203 |

Notes: Percentages and other figures are based on weighted data and sample sizes on unweighted data. For each characteristic variable, a design-based chi-square test was used to assess statistically significant difference between foster carers and relative/kinship carers, and between male and female carers (*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding. a Includes carers whose care type couldn't be ascertained or gender was missing. b Sample sizes varied slightly across variables due to non-responses to specific variables.

Table 3.3 depicts carers' financial circumstances. Financial circumstances were measured using annual gross household income, housing tenure, number of financial hardships experienced in the past year, and self-assessed financial situation. The number of financial hardships was measured by asking carers whether they had experienced any of eight specific events in the last 12 months due to a shortage of money, with the events including incidences such as inability to pay utility bills, car registrations, rent or mortgage on time; inability to heat the home; missing meals; selling something; or seeking financial assistance from family/friends or a welfare/community agency. The table shows the extent to which carers experienced none, one hardship or multiple hardships.

Carers' assessments of their financial circumstances were based on their responses to being asked how they felt that they and their family were getting along financially, given their current needs and financial responsibilities. Six response options were provided (prosperous, very comfortable, reasonably comfortable, just getting by, poor and very poor). The table shows responses in four groups - prosperous or very comfortable, reasonably comfortable, just getting by, poor or very poor.

- Just over one-half of carers (54%) had an annual gross household income under $60,000, with over one-fifth under $30,000. One-quarter of carers reported that their annual gross household income was between $60,000 and $99,999, while just one-fifth had a gross household income consisting of $100,000 or more.10

- How do carers' household income levels compare with Australian households overall? To address this question, the data collected from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey11 in 2014 were analysed. The results suggest that carers had a lower household income compared with overall Australian households.

- Of the households in HILDA data collected in 2014, 16% had an annual gross household income under $30,000 (here called "low income"), while 37% had a level of annual gross household income of at least $100,000 (here called "high income"). By contrast, a higher proportion of carers was in the low household income group (22%) and a lower proportion was in the high household income group (21%).

- In terms of housing, one-quarter of carers reported that they owned their home outright and 40% were purchasing. Close to one-quarter were renting privately and one-tenth were on public housing. The proportion of carers who were living in public housing was higher than for general households in Australia according to HILDA 2014 (11% vs 4%). This is consistent with the lower level of household income among carers than generally across Australian households.

- The majority of carers reported that they did not experience any of the specified financial hardship events in the past 12 months. One-tenth of carers experienced one form of hardship while 14% reported experiencing at least two hardships. HILDA also collected this data and their results were similar to the reports of the carers.12

- Although the results above suggest that carers were financially not as well-off as Australian households overall, few carers considered that they and their families were poor or very poor (less than 1%). Instead, the most common response was that they were reasonably comfortable (58%), followed by feeling that they were just getting by (25%). Seventeen per cent of carers said they were prosperous or very comfortable. HILDA also collected this data and the responses to this question in HILDA 2014 were similar to those by carers in this study.13

Foster carers and relative/kinship carers differed in their financial circumstances. With each measure, relative/kinship carers were less well-off financially than foster carers.

- A higher proportion of relative/kinship carers than foster carers was in the lowest category of annual gross household income (< $30,000) (28% vs 16%), while a higher proportion of foster carers than relative/kinship carers was in the top category of household income ($100,000+) (30% vs 13%).

- Higher proportions of relative/kinship carers than foster carers were in private rental (26% vs 20%) or in public housing (15% vs 5%).

- Relative/kinship carers were more likely than foster carers to experience multiple financial hardships (19% vs 8%).

- Compared with foster carers, relative/kinship carers were more likely to report that they and their families were financially just getting by, poor or very poor (33% vs 17%).

The difference in financial circumstances between male and female carers was less apparent than that between foster and relative/kinship carers.

- Compared with male carers, a higher proportion of female carers was in the lowest category of annual gross household income (less than $30,000) (23% vs 17%) and a lower proportion was in the highest category ($100,000+) (20% vs 28%).

- Male and female carers were similar in terms of housing tenure, their experience of financial hardships and self-assessed financial situation.

| Care type | Carer's gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster carers (%) | Relative/kinship carers (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | All a (%) | |

| Annual gross household income | *** | * | |||

| < $30 k | 16.0 | 27.7 | 17.2 | 22.7 | 22.0 |

| $30-59 k | 26.5 | 37.8 | 28.0 | 32.8 | 32.2 |

| $60-99 k | 27.8 | 22.0 | 27.0 | 24.6 | 24.9 |

| $100+ k | 29.8 | 12.5 | 27.7 | 19.9 | 20.9 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Housing tenure | *** | ||||

| Own outright | 25.0 | 24.7 | 27.2 | 24.5 | 24.9 |

| Purchasing | 48.5 | 31.9 | 42.8 | 39.3 | 39.7 |

| Private rental | 19.6 | 26.4 | 19.7 | 23.7 | 23.2 |

| Public housing | 5.4 | 15.1 | 9.1 | 10.8 | 10.5 |

| Other | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Number financial hardships experienced in the past year | *** | ||||

| None | 83.5 | 70.7 | 75.9 | 76.9 | 76.8 |

| One | 8.4 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 9.7 |

| Two or more | 8.1 | 18.5 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 13.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Self-assessed financial circumstances | *** | ||||

| Prosperous/very comfortable | 22.3 | 11.5 | 13.8 | 17.0 | 16.6 |

| Reasonably comfortable | 60.5 | 55.8 | 60.0 | 57.8 | 58.1 |

| Just getting by | 17.0 | 31.4 | 25.8 | 24.4 | 24.5 |

| Poor, very poor | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Number of carers b | 1,196 | 1,004 | 267 | 1,935 | 2,203 |

Notes: Percentages and other figures are based on weighted data and sample sizes on unweighted data. For each characteristic variable, a design-based chi-square test was used to assess statistically significant differences between foster carers and relative/kinship carers, and between male and female carers (*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding. a Includes carers whose care type couldn't be ascertained or gender was missing. b Sample sizes varied slightly across variables due to non-responses to specific variables.

3.4 Summary

Among the responding carers, a slightly higher proportion were relative/kinship carers (53%) as compared to foster carers (47%), with the great majority of carers being female in both groups (87% and 88% respectively). The majority of relative/kinship carers (66%) were grandparents to the study children. The distribution of the two care types was similar to the national data on carers in the child protection systems across Australia (AIHW, 2015).

Carers were 53 years old on average, with nearly one-half aged 50-64 years of age, and with a further 12% of carers aged 65 years or older. A small proportion of carers (6%) was aged 70 years or older. Most carers had no post-school qualifications, including four in ten who had not completed secondary education, and more than half of the carers under 65 years of age were not in paid employment. There were some differences in the socio-demographic characteristics of foster carers and relative/kinship carers, with the latter group reporting lower educational attainments. They were also more likely to be older and to be from an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background but less likely to live with a partner. When considering both carer groups, male carers were more likely to be older than female carers and were more likely to live with a partner, report higher educational attainment and be in paid employment.

The mean age of the study children was 9 years, with similar mean ages for the two carer groups and slightly more male than female children among the study children. More than four in ten study children were of primary school age (5-11 years) and close to one-quarter were pre-school aged (under 5 years).

The data showed that the majority of carers had an annual gross household income of less than $60,000, while one-fifth of carers relied on less than $30,000. Carers had lower levels of annual gross household income compared to general Australian households. Furthermore, a greater proportion of carers lived in public housing compared to the general population, according to HILDA. Although the data suggests that carers were not as financially well-off as Australian households, most carers reported themselves to be "reasonably comfortable". Of note, however, compared to foster carers, relative/kinship carers were more likely to have low annual gross household incomes, to live in private rental or public housing and to report experiencing financial hardship.

8 For two carers, care type could not be determined.

9 The survey was meant to focus on carers with children under 18 years in out-of-home care; however, eight carers with a child who had just turned 18 were included in the survey.

10 Gross household income includes income from all sources (e.g., wages, pensions, income supports, allowances, etc.).

11 The HILDA project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

12 It should be noted that HILDA collected this data in a self-completed questionnaire from all respondents aged 15 years and older. The HILDA sample is younger than the sample of carers in this study. The mean age of the HILDA sample in 2014 was 45 years, compared to 53 years for carers in this study.

13 See Footnote 12 for differences between this study and HILDA in how this data were collected and the mean age of respondents.

4. Care experience

Children in out-of-home care have often experienced abuse, neglect or other traumatic events that can lead to severe consequences for their development and wellbeing, in addition to immediate harm (e.g., Frederico, Jackson, & Black, 2009). This complexity of children's prior experience and developmental needs can present significant challenges for carers. The survey assessed the carers' experiences from a range of aspects, including how the children came to be in their care, how long carers had looked after the study child and, in particular, the timing of knowing about the study child's prior history of abuse, neglect and problems at home as well as the child's developmental and health disorders.

4.1 Becoming the study child's carer

Carers were asked how the study child came into their care - whether they were approached by their jurisdictional department, by the study child's parents or family members, or had volunteered to look after the study child. Their responses are shown in Table 4.1.

- The most common response by carers was that they were approached by their jurisdictional department or agency (64%); the next most common response was having volunteered before any approach by a department or agency (29%).

- Over one-tenth (12%) reported that they were asked by the child's parents or family members to look after the child. A very small proportion said that the study child transitioned from a temporary care arrangement to a long-term arrangement in their care.

- Foster carers were more likely to report that they were approached by a department or agency compared to relative/kinship carers (76% vs 53%).

- A substantial minority of relative/kinship carers (20%) said that they were asked by the child's parents or family members to look after the child, which was much less commonly reported by foster carers (2%).

- A very small proportion of foster carers became the formal carer of the study child from a temporary arrangement, which is a pattern that does not apply to relative/kinship carers. On the other hand, for a small proportion of relative/kinship carers, the study child came into their care from a court order or via the study child's own request.

- Reports of male carers and female carers were similar regarding how the study child came into their care.

| Care type | Carer's gender |

All a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster carers (%) | Relative/kinship carers (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | ||

| Approached by a department or agency | 76.2 | 52.8 | 61.5 | 64.2 | 63.9 |

| Volunteered before any approach by a department or agency | 22.6 | 34.4 | 32.8 | 28.3 | 28.9 |

| Influenced by participating in a Family Group Conference/planning meeting (WA only) | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Approached by study child's parent(s) or family member(s) | 2.1 | 20.1 | 8.5 | 12.0 | 11.6 |

| Transitioned from respite/temporary care | 0.7 | - | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Court order | - | 1.4 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| Approached by study child him/herself | - | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Other | 1.4 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Two or more reasons | 3.1 | 11.0 | 8.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 |

| Number of carers | 1,193 | 999 | 264 | 1,929 | 2,194 |

Notes: Percentages are based on weighted data and sample sizes on unweighted data. A small number of respondents who either refused or opted "Don't know" were excluded from the analysis (0.4%). Multiple responses and percentages may exceed exactly 100% in total. a Includes carers whose care type couldn't be ascertained or gender was missing.

Further analysis was carried out by dividing relative/kinship carers into two groups: grandparents and other relatives. The analysis indicates that how study children came into their care differed somewhat between the group groups (results not shown in Table 4.1):

- Grandparents were more likely than other relative/kinship carers to report that a department or agency approached them (56% vs 46%).

- Other relative/kinship carers were more likely than grandparents to report that one of the study child's parents or family members asked them to look after the child (29% vs 15%).

Only grandparents reported that that the study child was in their care as a result of a court order, none of the other relative/kinship carers reported this.

4.2 Number of times and duration of looking after study child

While relative/kinship carers would be likely to have known the study child before he/she came into their care, some foster carers may have also known their study child. Some carers may have looked after the study child previously. The extent to which the study child had lived with the carer previously is presented in Figure 4.1.

- The great majority of carers reported that the study child had only lived with them once, that is, the current episode (88%). Nine per cent reported that the study child had lived with them once previously and an even smaller proportion (4%) said that the study child had lived with them in two separate periods.

- Given the likelihood of having an established relationship with the study child, it is not surprising that a higher proportion of relative/kinship carers than foster carers reported that the study child had previously lived with them (14% vs 10%).

- Further analysis revealed that grandparent carers were more likely than other relative/kinship carers to have previously had the study child living with them (16% vs 11%).

- There was no gender difference among carers in whether carers had previously had the study child living with them.

Figure 4.1: Number of times that study child came to live in the household (including current episode), by care type and gender of carers

Note: Percentages are based on weighted data.

Figure 4.3 shows when carers learned of study children's previous experiences of abuse, neglect or problems at home by care type. Foster carers and relative/kinship carers differed somewhat in terms of when they were informed about the study child's past experiences.

- Regarding sexual abuse that study children experienced in the past, both foster and relative/kinship carers typically reported that they learned this information after their study child was living with them (57% and 52% respectively).

- Regarding the other five types of abuse/neglect experiences that study children had experienced in the past, foster carers were much more likely than relative/kinship carers to become aware of what happened after their study child was living with them:

- emotional abuse: 30% vs 13%

- physical abuse: 41% vs 21%

- neglect: 22% vs 9%

- family violence in the household: 36% vs 12%

- household member(s) with alcohol or drug use problems: 30% vs 7%.

Figure 4.3: The stage at which carers became aware of the study child's previous experiences of abuse and/or neglect, by care type

Note: Percentages are based on weighted data.

Figure 4.4 shows when carers learned of study children's experiences of abuse and/or neglect in the past by gender.

- A greater proportion of male carers than female carers reported learning about the study child's prior experiences before their arrival, except with neglect:

- emotional abuse: 60% vs 55%

- physical abuse: 55% vs 47%

- sexual abuse: 34% vs 28%

- family violence: 64% vs 54%

- alcohol/drug problems on the part of household members: 74% vs 64%.

Figure 4.4: The stage at which carers became aware of the study child's previous experiences of abuse and/or neglect, by carer gender

Note: Percentages are based on weighted data. a Base on a small number (n = 30)

Carers were asked to report on how they became aware of each indicator of the study child's abuse and/or neglect, that is, who provided the carer with the information. Carers' responses are presented in Table 4.5, which also shows results by care type and by gender of carers.

- In relation to each indicator of abuse and neglect, a caseworker or official was most commonly reported as the source of information for the carers (38-50%).

- The second most common responses were that carers knew, had witnessed or suspected it (25-46%), except in the case of sexual abuse (8%).

- The next two less common, but significant, sources were the study child themselves (9-33%) and the study child's family (11-19%).

- Of the six indicators of abuse and neglect, the study child as a source of information was the highest in relation to sexual abuse (33%), followed by physical abuse (27%), while it was 9-20% for the other forms.

- Small proportions of carers reported other sources (e.g., psychologist, found out by themselves) (5% or lower).

How carers became aware of the prior experiences of abuse and/or neglect of study children differed between the two types of carers.

Higher proportions of foster carers than relative/kinship carers reported that they were advised by a caseworker or other official (49-71% vs 18-28%), while relative/kinship carers were more likely to report that they had witnessed or suspected each form (13-75% vs 5-12%).

- The majority of foster carers reported that they were advised by a caseworker or other official (56-71%), but this was lower in the case of sexual abuse (49%). The second most common source reported was the study child themselves.

- Relative/kinship carers most commonly reported that they had witnessed or suspected the abuse and/or neglect experiences (44-75%), except for experiences of sexual abuse, which were more commonly disclosed by the study child (34%). Approximately one-quarter or fewer carers in this group reported that they became aware of the study child's abuse/neglect experiences from a caseworker or other official. Somewhat lower proportions of relative/kinship carers became aware of the child's experiences because of a disclosure from the study child but were more frequently told by another member of the child's family.

Male and female carers were similar in their reports of sources of knowledge about the study child's prior experiences.

| Emotional abuse | Physical abuse | Sexual abuse | Neglect | Family violence in the household | Household members with alcohol/drug use problems | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster carers | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| I knew the family and had witnessed or suspected it | 12.0 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 10.9 | 9.1 | 11.0 |

| A caseworker/other official | 59.6 | 56.3 | 49.3 | 70.9 | 67.3 | 70.3 |

| Study child told me | 22.1 | 29.4 | 31.9 | 12.4 | 17.9 | 13.1 |

| A family member of study child | 10.2 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 15.8 | 12.7 |

| I found it out | 6.9 | 5.6 | 12.2 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Psychologist | 2.2 | 2.7 | 6.4 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Other | 5.1 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 4.3 |

| Don't know | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Number of carers | 697 | 498 | 136 | 865 | 745 | 827 |

| Relative/kinship carers | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| I knew the family and had witnessed or suspected it | 61.4 | 43.7 | 12.8 | 59.9 | 56.4 | 75.1 |

| A caseworker/other official | 22.4 | 24.6 | 17.9 | 28.3 | 22.8 | 19.6 |

| Study child told me | 17.3 | 24.2 | 33.7 | 8.3 | 13.5 | 6.3 |

| A family member of study child | 15.3 | 20.7 | 16.9 | 13.1 | 22.5 | 15.0 |

| I found it out | 2.5 | 2.4 | 11.0 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Psychologist | 1.2 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Other | 4.7 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 3.1 |

| Don't know | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Number of carers | 517 | 330 | 62 | 648 | 609 | 75 |

| Male carers | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| I knew the family and had witnessed or suspected it | 38.8 | 21.7 | 10.4 | 33.1 | 42.5 | 49.8 |

| A caseworker/other official | 47.0 | 49.7 | 31.9 | 50.5 | 44.0 | 40.1 |

| Study child told me | 23.2 | 27.0 | 45.6 | 13.8 | 17.9 | 8.3 |

| A family member of study child | 12.2 | 7.8 | 4.2 | 11.2 | 14.7 | 10.7 |

| I found it out | 2.1 | 2.8 | 6.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| Psychologist | 0.6 | 6.5 | 11.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.8 |

| Other | 4.1 | 5.7 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 2.4 |

| Don't know | 1.2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Number of carers | 142 | 107 | 27 | 179 | 147 | 183 |

| Female carers | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| I knew the family and had witnessed or suspected it | 36.2 | 25.2 | 7.6 | 35.6 | 32.6 | 45.6 |

| A caseworker/other official | 40.4 | 40.2 | 38.4 | 49.6 | 44.2 | 42.8 |

| Study child told me | 19.2 | 26.9 | 30.5 | 9.9 | 15.4 | 9.6 |

| A family member of study child | 12.8 | 15.7 | 13.6 | 11.1 | 19.9 | 14.4 |

| I found it out | 5.1 | 4.3 | 12.5 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Psychologist | 1.9 | 2.7 | 6.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Other | 5.0 | 4.9 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 3.8 |

| Don't know | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Number of carers | 1,073 | 722 | 171 | 1,335 | 1,209 | 1,400 |

| All | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| I knew the family and had witnessed or suspected it | 36.5 | 24.7 | 8.0 | 35.3 | 33.7 | 46.1 |

| A caseworker/other official | 41.2 | 41.4 | 37.5 | 49.7 | 44.1 | 42.5 |

| Study child told me | 19.7 | 26.9 | 32.6 | 10.4 | 15.7 | 9.4 |

| A family member of study child | 12.7 | 14.7 | 12.3 | 11.1 | 19.3 | 13.9 |

| I found it out | 4.7 | 4.1 | 11.7 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| Psychologist | 1.7 | 3.2 | 6.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Other | 4.9 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 3.7 |

| Don't know | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Number of carers | 1,215 | 829 | 198 | 1,514 | 1,356 | 1,583 |

Notes: Percentages are based on weighted data and sample sizes are unweighted. Multiple responses and the sum of column percentages may exceed 100% and statistical test is not applied.

4.4 Study children's developmental conditions before current placement