Access to early childhood education in Australia

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Download Research report

Overview

This report presents AIFS research undertaken to identify gaps in access to and participation in preschool programs by Australian children in the year before full-time school. This research had the following objectives:

- review how "access" to preschool services is conceptualised and defined;

- identify the issues and factors that affect access to preschool services; and

- document and provide recommendations on how access to preschool services can be measured beyond broad performance indicators.

To meet these objectives, the publication includes a review of Australian and international literature; results of consultations across Australia; and analyses of participation of children in early childhood education using a number of Australian datasets.

Key messages

-

"Access" to early childhood education (ECE) in Australia is considered to be more than just "participation" in ECE. It should, for example, also cover elements of quality, relevance to children. However, data are not available that would allow measurement against such a broadly defined concept of "access".

-

There are difficulties and limitations in using existing survey and administrative data to measure "access" by "participation" in ECE. Nevertheless these data provide broad indications of ECE participation. Participation rates have the advantage of being easily understood and easily compared over jurisdictions and time.

-

The complexity and variation in how ECE is delivered in Australia has implications for the measurement of access. This is related to different nomenclature used, and varied ages at which children are eligible to attend ECE. The different models of delivery of ECE also complicate the measurement issues, with long day care a widespread provider of ECE in some states/territories, but not others.

-

Given there are difficulties in measuring access, this research used a number of datasets, to provide a fuller understanding of access across Australia.

-

The analyses showed that children missing out on ECE were more often represented among disadvantaged families, and whose children are perhaps in greatest need of ECE to achieve school-readiness. The groups of children who stood out in these analyses as being less likely to be participating in ECE were Indigenous children and children from NESB backgrounds.

Executive summary

The Access to Early Childhood Education project

On 29 November 2008, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) endorsed the National Partnership Agreement on Early Childhood Education (NP ECE). This agreement committed the Commonwealth and all state and territory governments to achieving universal access to preschool by 2013. As part of this National Partnership, it was acknowledged that high-quality information is an essential component of the COAG Early Childhood Reform Agenda to ensure an evidence base for policy and program development.

The Access to Early Childhood Education (AECE) project was undertaken by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) on behalf of the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) to explore access to early childhood education (ECE) in the context of the NP ECE. There were three key components to the project:

- a conceptual analysis of what "access" means, according to Australian and international literature and key stakeholders;

- consideration of issues around measuring access and how it may be better measured in the future; and

- examination of the factors that affect access to early childhood education for Australian families, especially in relation to vulnerable or at-risk groups of children.

The undertaking of these project objectives broadly entailed the following methods:

- a review of the Australian and international literatures;

- consultation with key government and non-government stakeholders across Australia; and

- analyses of national datasets from the National Survey of Parents' Child Care Choices (NSPCCC), 2009; the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), 2008; the Australian Early Development Index (AEDI), 2009; and the Childhood Education and Care Survey (CEaCS), 2008.

This research has focused on exploring early childhood education for children, specifically those in the year prior to full-time schooling.

The literature reviews and consultations were important in addressing each of the three key components of the projects. The analysis of survey data provided insights into issues concerning measurement of access, but was particularly valuable for the third of the components, on factors that affect access to ECE. Results from each of the methodologies are woven together in the sections that follow, summarising the key findings for each component of the study. However, before interpreting the results it is prudent to first consider the context of ECE in Australia.

Early childhood education in Australia

Reflecting the federal system of government in Australia, the delivery of early childhood education services is undertaken by the state and territory governments. Furthermore, many local governments are also involved in the provision of such services, and the result of this division of powers and responsibilities is a great deal of variation in the way in which ECE is provided. The complexity and diversity is apparent if we consider that ECE services are provided through kindergartens, stand-alone preschools, long day care (LDC) settings and early learning centres, as well as preschool programs within the independent school sector.

ECE programs in Australia tend to be delivered along two broad models of ECE - one a predominantly government model and the other a predominantly non-government model. In the former, it is more typical for ECE to be accessed through standalone preschools or preschools attached to schools. Preschool is often free (with a voluntary levy) under this model. In the latter, there is more diversity in the arrangements, with LDC also playing a significant role, and costs tending to be higher. The eastern states of NSW, Victoria and Queensland generally are more closely aligned with the non-government model, with the other states/territories looking more like the government model.

Taking account of the variation of settings within which ECE is offered across Australia was an important factor in understanding the findings of the AECE project. In particular, the complexity of ECE in Australia has implications for the measurement of access. The extent to which different settings might affect access to ECE is an important issue, and this is discussed below, when considering the question of whether (and why) some children are missing out on ECE.

The meaning of "access" to early childhood education

One of the components of the AECE project was in relation to establishing the meaning of "access" to early childhood education. Views of key stakeholders were sought regarding what they perceived "access" to early childhood education to be. The literature regarding the meaning of "access" was reviewed, particularly in the context of early childhood education. Together, this information confirmed that there is widespread agreement that "access" to ECE is a multidimensional concept, encompassing more than just the number or proportion of children enrolled in ECE.

The stakeholder discussions identified the following components of "access":

- creating opportunities for children to participate in ECE programs;

- providing enough time within the programs for children to learn; and

- allowing children to experience the program (and its potential benefits) fully.

In other words, being able to provide a place for children to enrol in ECE is the first step toward access. Whether availability of places translates into enrolment in places is likely to depend on the characteristics of the services that offer those places and on the preferences of parents of children who are eligible to attend these services. The Australian and international literature identified factors such as cost, quality, opening hours, physical location and the responsiveness of services to meeting diverse child and family needs as being important to families.

The aspect of time, when raised by stakeholders as one part of the "access" concept, may to some extent reflect that under the NP ECE, access to ECE involves providing programs to children for 15 hours per week.

Beyond the idea of children simply being present at a service for enough time in the year prior to full-time schooling, there was also acknowledgement in both the stakeholder discussions and the literature that access needs to be considered in terms of the experience of attending the program being of benefit to children. That is, the program needs to be of high quality, accessible and delivered in such a way that the child is able to fully experience the potential benefits of ECE.

In summary, this component of the project found that "access" to ECE is multidimensional, both conceptually and in practice, which supports the broader goals of the NP ECE. This, of course, provides challenges when attempts to measure a more completely defined concept are attempted, as discussed in the next subsection.

Measuring "access" to early childhood education

The second component of this project related to the measurement of access to early childhood education. Broadly, there were two sets of issues:

- measurement issues related to the simplest aspect of access - that of participation or enrolment in ECE; and

- whether or not, and how, to incorporate the multidimensional nature of "access" into the measurement.

Access measured by participation or enrolment

Several difficulties in measuring access to ECE in terms of participation were identified in this report, and were evident in the analyses of survey data. Difficulties were clearly documented in the existing literature and were also described by the various government and non-government stakeholders in our consultations. In fact, we found that measurement issues are keenly felt at the operational level, with some stakeholders feeling that they lack full information about the extent to which children - and children with particular characteristics - might be missing out on ECE in their region.

The key issues affecting measurement of participation or enrolment in ECE for children in the year prior to full-time schooling that were identified in the AECE project include the following:

- The diversity of ECE systems across Australia and the different nomenclature used for preschool and the first year of school across the states caused some initial difficulties, especially in the surveys, in the collection of accurate data on children's participation in ECE. For example, some parents may not have been aware of whether their child received a preschool program in LDC, while some parents may have found it difficult to say whether their child attended a preschool as opposed to a child care centre. If ECE was delivered in a school setting, this could likewise have been misreported as the children being in school rather than ECE.

- Related to this, the variation in school starting age caused difficulties in identifying the population eligible for ECE. This is due to differences across jurisdictions in the age at which children commence full-time school, and from children being able to commence school one year after they are eligible to start.

- The diversity of service providers also adds complexity and challenges to the collection and analyses of administrative data. The availability of multiple service providers for ECE can pose challenges for those relying on administrative data, as children may be double-counted if they attend more than one program.

- Survey data (such as those from the national collections used in this report) are usually not useful for analyses of local area or regional patterns of ECE participation, given sample sizes do not allow disaggregation to small areas. Administrators and service providers require information about ECE participation as it applies to their region or local area.

- Information on ECE enrolment allows examination of the characteristics of those who enrol, but obviously not the details of children who have not enrolled. This, then, limits the potential to study factors related to children missing out on ECE in that area or jurisdiction. Australian Census data can be helpful in identifying potentially eligible populations, but these data become out-of-date between Census years (with gaps of up to five years).

Despite the measurement difficulties and limitations, in this report we have shown that survey data can provide some insights into ECE in Australia, at least at the broader state/territory and national levels. Participation rates have the advantage of being easily understood and easily compared over jurisdictions and time. Compared to more sophisticated measures, such figures are also relatively easy to derive from existing datasets.

There are, however, still challenges that mean even these estimates are not as exact as might be needed. This was evident in this report in the divergence of some of findings across different datasets - particularly so when examining participation rates within particular states and territories of Australia. For this reason, we did not remark on these differences in this report. These divergent findings highlight that it is important to be mindful of the limitations of the data that are currently available when using these data for decision-making.

A multidimensional measure of access to early childhood education?

Clearly, focusing only on participation misses out on the multidimensionality of the concept of "access", as this disregards dimensions such as the hours and quality of children's experiences of an ECE program. Conceptually, it would be relatively simple to extend the notion of participation, as used in this report, to incorporate the dimension of time - to classify children, for example, as receiving no ECE, some ECE but fewer than 15 hours a week, and receiving ECE for 15 hours per week or more. In practice, there are likely to be challenges, especially for children who receive ECE across more than one program, and those who may vary their hours of ECE from week to week.

Adding in a dimension of quality of the ECE experience for children is immensely more challenging. It may be possible to identify to what extent children are receiving their ECE from appropriately trained educators; however, in surveys, parents may be unaware of these details. Again, it would be difficult to capture the instances of children receiving ECE from multiple providers. Of course, the qualification of the educator is just one indicator of the likely quality of the ECE experience. It is, however, not clear how other indicators could be captured to reflect individual children's experience within a program; for example, compared to other children, those with special needs and from culturally diverse or disadvantaged backgrounds may gain different experiences and benefits from an otherwise high-quality program.

These analyses have led us to the view that it is useful to measure access, in the first instance, in terms of participation or enrolment, which allows examination of how access varies across time, across jurisdictions and across different socio-economic groups. This, however, needs to be done carefully, being mindful of the data issues and limitations that are a consequence of the way in which ECE is delivered in Australia.

Until access can be measured well in this simple way, it will be difficult to draw in the other dimensions that have been highlighted in this report. However, consideration of the multidimensionality of access can still be acknowledged. The information about participation or enrolment could be supplemented with other more detailed, and perhaps qualitative information, to inform on these different aspects of access and provide more depth to the overall quantitative data.

Which children are missing out, and why?

In this component of the AECE project, we drew upon the views of stakeholders, the literature, and new analyses of three main datasets (AEDI, NSPCCC and LSAC), to explore which characteristics of children, families or regions might predict lower levels of access to ECE. These data analyses focused on access in terms of participation in ECE, for children in the year before full-time school. Children were considered to be in ECE if they were in either preschool or long day care. Any participation in LDC was counted as ECE, regardless of whether parents reported that their children had a preschool program as part of LDC. It was felt that any LDC for children of this age was likely to involve a structured program, and would be expected to have some component of early learning built in. Also, the decision to include any LDC as ECE was partly due to data quality concerns about the distinction between LDC with and without preschool programs.

Some analyses of the types of ECE used was also included, with a view to understanding whether there were particular gaps in the use of some types of services by those children who were potentially at risk of missing out on ECE.

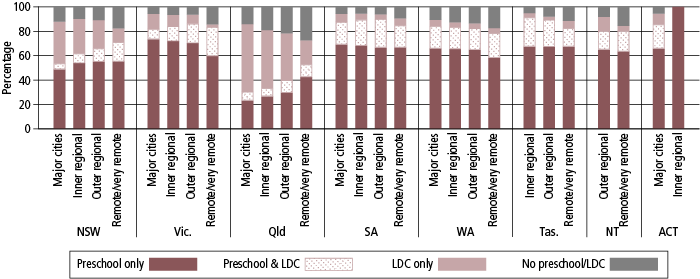

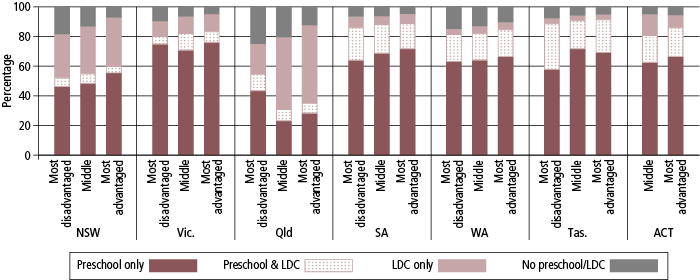

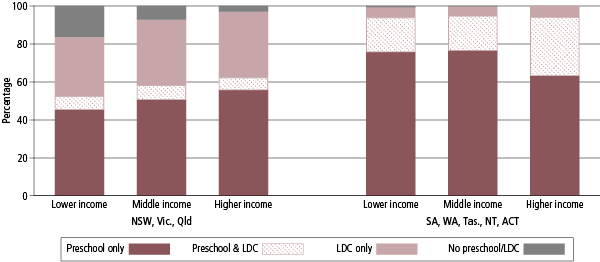

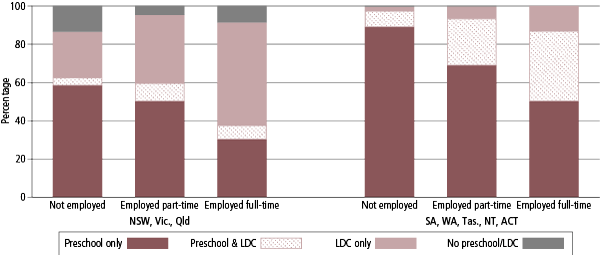

As noted above, in the analyses of participation in ECE, we found that each dataset portrayed a different story with regard to participation rates across states and territories, and so we have not focused on those differences. However, the variation in types of ECE clearly reflected the state/territory differences in ECE delivery, showing up the greater reliance on LDC in the eastern states than in other states. In all states/territories, though, there was a significant proportion of children in both preschool and LDC.

In the data analyses, a range of characteristics was examined to cover local area variation (remoteness and socio-economic disadvantage of regions), socio-economic characteristics of families (parental income, employment, single- versus couple-parent families, parental education); and other characteristics, including Indigenous background of families, non-English speaking background (NESB) of families, and children with special health needs. These characteristics were included in the analyses as they reflected some of the key factors referred to in the literature and the consultations as being potentially able to identify children who were missing out on ECE.

Which children are missing out on ECE?

The analyses confirmed the expectations of the stakeholders and also the findings reported in the literature that children missing out on ECE are more often represented among disadvantaged families, and among children who are perhaps in greatest need of ECE in respect of preparing children for school. The groups of children who stood out in these analyses as being less likely to be participating in ECE were Indigenous children and children from NESB families. Children from socio-economically disadvantaged families were also less likely to participate in ECE than those from socio-economically advantaged families. Children living in remote areas had the lowest levels of participation in ECE compared to those living in major city areas. There was also some variation according to the disadvantage of regions, but it was not clear that this reflected the characteristics of the regions or the families living within those regions.

We did find that there tended to be more variation in participation in ECE by these characteristics in the eastern states - the states in which ECE is more often provided through LDC. That is, there were greater differences in participation between the least and most vulnerable children in the eastern states than in the other states.

The factors driving the differences in ECE participation are not all easy to identify, given the overlapping nature of many of the characteristics we have examined. For example, compared to non-Indigenous children, Indigenous children are more likely to be living in socio-economically disadvantaged families and in remote regions, so their lower participation rates may be affected by all or any of these factors. Also, the analysis is complicated by the distinction between preschool and child care. In particular, parental employment is likely to be strongly linked with a need for child care. Decisions about child care versus preschool for some families, are expected to be associated with parental employment factors, as well as the availability of different care and ECE options.

Why do some children miss out on ECE?

This question proved particularly difficult to answer within the scope of this research project, and we could not provide any definite answers. As discussed below, understanding reasons for non-participation would be best explored with a different research methodology.

With one of the differences in the models of delivery of ECE being the cost of services, an important question is to what extent cost (or perceived cost) of services affects access to ECE for more vulnerable or disadvantaged families. Issues of costs or availability to ECE were sometimes referred to by parents when they were asked why their children were not in ECE. However, parents were most likely to say their children were not in ECE because of reasons related to the availability of a parent to care for children, or related to a belief in parental care of children. This suggests some degree of choice being exercised by these parents, but it warrants further attention, preferably with a different research methodology that would allow the decision-making process to be explored more fully. This would be particularly useful in regard to more disadvantaged and vulnerable families.

The analyses of parental decision-making and types of ECE provide some insights into the various factors parents take into account when choosing ECE for their child. While some clear patterns emerge from some of these data, they need to be interpreted cautiously. For example, these analyses show that for children attending LDC only, the most common response parents provided as the reason for choosing this arrangement was to accommodate work and study commitments. Where children were attending a preschool-only program, however, the most common reasons provided focused on social and intellectual development. However, this does not mean that parents choosing only LDC don't value their child's development - it may be that they are also taking these factors into account when choosing ECE for their child.

Most of the findings presented here were consistent with expectations, although some suggest that further research may be useful in helping disentangle how different factors affect family decision-making regarding child participation in ECE. In particular, more research on factors related to family income, employment and parental education levels, and how they intersect with decisions about ECE would help in understanding the issues for more vulnerable families. If such research also took into account the availability of different types of ECE in the local area, it would be useful for examining how the supply of different services affects the decision-making of parents.

Conclusion

Returning to the broader focus of this project, we have presented the view that access to ECE should be considered as being multidimensional. This is important because participation or enrolment should not be seen as the end point, and the intended goals of ECE need to be built into the concept of access.

However, in terms of measurement, this research suggests that it is important to address, as far as is possible, issues regarding the simplest measures of access - those of participation or enrolment - before attempting to incorporate other dimensions of access into the measures used. A simple measure of participation or enrolment is a useful starting point for monitoring trends and comparisons across groups. Even with some measurement difficulties, this report has highlighted the value of such measures in identifying some characteristics that are related to lower rates of access to ECE. To supplement this, more qualitative information, captured through one-off or occasional studies at regional (or national) levels, could be extremely valuable for providing greater insights into the other aspects of access. No doubt, service providers and other stakeholders also have available to them other ways of capturing some of the other dimensions of access that can be useful at the program level. Use of measures of participation or enrolment, along with this supplementary information, allows the multifaceted nature of access to be recognised without attempting the collection of new information, which is likely to come with its own set of very challenging measurement issues.

Another important part of this paper was using the information that we have to examine to what extent, and why, certain children are missing out on ECE. These analyses have identified that there are some risk factors and, consistent with prior research, we have found that more vulnerable and disadvantaged families are more likely to miss out on ECE. The picture is complicated, though, in part because of the interplay between preschool and long day care, and how parental choice of such services for children will also depend on parents' employment arrangements.

The most difficult aspect of this research, then, is "why" some children miss out on ECE. Existing data do not really delve into this question sufficiently to be able to understand to what extent non-participation is related more to choice or to constraints of parents. In the preceding section we already discussed some of the limitations of what we know about parents' decision-making in this regard. Gaining greater insights into the reasons for children's non-participation in ECE, as well as the experiences of children who do go, would be of considerable value. Such insights may need to be sought in a less structured format than is imposed through the questionnaires used in these analyses. More detailed discussions with parents may help to identify what the real barriers are for those not attending ECE and what factors are important within an ECE setting for their children to be able to fully experience the program.

1. Introduction

On 29 November 2008, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) endorsed the National Partnership Agreement on Early Childhood Education (NP ECE). This agreement committed the Commonwealth and all state and territory governments to achieving universal access to preschool by 2013. As part of this agreement, the following core objectives were outlined in clauses 17-19 of the NP ECE (COAG, 2008):

17. The universal access commitment is that by 2013 every child will have access to a preschool program in the 12 months prior to full-time schooling. The preschool program is to be delivered by a four year university qualified early childhood teacher, in accordance with a national early years learning framework, for 15 hours a week, 40 weeks a year. It will be accessible across a diversity of settings, in a form that meets the needs of parents and in a manner that ensures cost does not present a barrier to access. Reasonable transitional arrangements - including potentially beyond 2013 - are needed to implement the commitment to preschool program delivery by four year university qualified early childhood teachers, as agreed in the bilateral agreements.

18. Especially for the first two years of implementing universal access (2009 and 2010), national priorities include: increasing participation rates, particularly for Indigenous and disadvantaged children; increasing program hours; ensuring cost is not a barrier to access; strengthening program quality and consistency; and fostering service integration and coordination across stand-alone preschool and child care. The strategies for addressing these priorities may differ on a state-by-state basis.

19. Children living in remote Indigenous communities have been identified as a specific focus for universal access, with the Prime Minister announcing as part of his Sorry Day address that by 2013 every Indigenous four year old in a remote community be enrolled and attending a preschool program. This reflects the significant under-representation of Indigenous children in preschool programs. (pp. 5-6)

As part of this National Partnership, it has been acknowledged that high-quality information is an essential component of the COAG Early Childhood Reform Agenda to ensure an evidence base for policy and program development. To inform this evidence base, there is a need to undertake research on how to define and measure "access" in order to better inform and assess the progress of the NP ECE.

1.1 The benefits of early childhood education for children

The key principles driving the NP ECE involve the benefits of providing universal access to early childhood education, as set out in clauses 6-8 of the agreement (COAG, 2008):

6. Early childhood is a critical time in human development. There is now comprehensive research that shows that experiences children have in the early years of life set neurological and biological pathways that can have life-long impacts on health, learning and behaviour. There is also compelling international evidence about the returns on investment in early childhood services for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, including the work of Nobel Laureate James Heckman.

7. On average, children in Australia have good outcomes overall. The outcomes for some children however are poor and the gap is widening. Early childhood services, policies and practices in Australia have not benefited from a national focus and are therefore quite fragmented. This can be problematic for some families and particularly for those families with multiple and complex vulnerabilities, who may find it difficult to access and navigate fragmented services. It also makes it difficult to advance prevention-orientated and early intervention approaches for all children and to coordinate services for those with complex problems.

8. High quality early childhood services offer the productivity benefits of giving children the best possible start in life, and for parents, the opportunity to be active participants in the workforce or community life. (pp. 3-4)

These principles are based on an extensive international literature about the benefits of early childhood education for children prior to full-time schooling, and a detailed review of this literature was recently published as part of the 2010 annual progress report for the evaluation of the National Partnership (Urbis Social Policy, 2011).

High-quality early childhood education experiences are seen to have the potential to benefit all children in terms of their cognitive and social development, with higher quality programs having a higher positive effect on these dimensions (Urbis Social Policy, 2011; Wise, Da Silva, Webster, & Sanson, 2005). Participation in early childhood education programs has also been found to "improve school readiness, expressive and receptive language and positive behaviour for all children" (Urbis Social Policy, 2011, p. 30). For children from "disadvantaged" families, the link between quality programs and outcomes is even more pronounced, with "high quality education and care [offering] a direct strategy for maximising developmental outcomes, especially for young children from vulnerable families" (Urbis Social Policy, 2011, p. 29).

Similar syntheses of the research findings about the potential benefits of ECE have also been found in other reviews (Elliott, 2006; Press & Hayes, 2001).

1.2 Measuring access to early childhood education in Australia

Defining and measuring access to early childhood education is central to developing early childhood policies. As part of ongoing bilateral arrangements under the NP ECE, states and territories provide jurisdictional annual reports to the Commonwealth Government that inform on their progress towards achieving universal access against six NP ECE performance indicators. These include the proportion of children enrolled in (and attending, where possible to measure) a preschool program; the number of teachers delivering preschool programs who are four-year university-trained and qualified in early childhood education; hours per week of children's attendance; weekly cost per child (after subsidies); and the proportion of disadvantaged children, including Indigenous children, enrolled in (and attending) a preschool program (where possible to measure). While the Commonwealth and states and territories continue to work together to bring these reports into alignment, the diversity found across the different states and territories around the ways in which preschool programs are delivered, and the ages at which children participate in these programs, provide ongoing challenges. This is particularly the case when considering national datasets that seek to measure participation and outcomes, particularly for different groups within this cohort.

The data available suggest that a proportion of young children are not participating in preschool programs and therefore missing out on its potential benefits. Developing a better understanding of this group - that is, who is not participating in preschool programs and why - will help inform future early childhood policy and link with achieving universal access for all children. As noted above, this is seen to be particularly important for children from disadvantaged and vulnerable backgrounds, where there is strong evidence that the delivery of a high-quality early childhood education program in the year before full-time schooling is vital in providing a solid foundation for future learning and development.

The Access to Early Childhood Education Project

The Access to Early Childhood Education (AECE) Project has been undertaken by the Australian Institute of Family Studies on behalf of the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR)1 to explore the question of what "access" to ECE means and how it could be measured. The research involved a number of methodologies, including a review of Australian and international literature; consultations across Australia with key stakeholders from both government departments involved in the implementation of the NP ECE and non-government agencies concerned with the education and wellbeing of young children; and analyses of key Australian datasets that provide information about the participation of children in ECE in the year prior to full-time schooling.

There are three key components to the project:

- a conceptual analysis of what "access" means, according to Australian and international literature and key stakeholders;

- consideration of issues around measuring access and how it may be better measured in the future; and

- analyses of several key datasets to examine the factors that affect access to early childhood education for Australian families, especially in relation to vulnerable or at-risk groups of children.

To explore these factors, the report examines a range of child, family and regional characteristics to identify those groups of children most likely to be missing out on ECE. Analyses of parental decision-making concerning ECE are also included, to help inform on why particular groups of children may not be receiving ECE.

The report commences in Section 2 with a brief overview of how ECE is delivered in Australia, followed in Section 3 by a detailed description of the methodologies employed in the AECE Project. Section 4 then considers the meaning of the term "access", and discusses the various characteristics expected to be associated with variations in levels of access to ECE, as well as issues related to the measurement of such access. Section 5 presents the first set of data analyses, focusing on how overall access to ECE varies for children with different characteristics. Section 6 presents the second set of data analyses, with a view to explaining the variation in the types of ECE in which children participate. Finally, Section 7 presents a conclusion to the report.

1 The research project was commissioned by DEEWR on behalf of the Early Childhood Data Sub Group (ECDSG), which works to implement the National Information Agreement on Early Childhood Education and Care (NIA ECEC). The NIA ECEC outlines an agreed work program, which includes the administration of projects funded from the overall allocation of $3 million retained annually for national early childhood research, evaluation and data development activities.

2. The provision of early childhood education in Australia

Since the 2008 COAG commitment that by 2013 "all children in the year before full-time schooling will have access to high quality early childhood education programs delivered by degree-qualified early childhood teachers, for 15 hours per week, 40 weeks of the year, in public, private and community-based preschools and child care" (Dowling & O'Malley, 2009), the delivery of early childhood education in Australia has undergone significant change.

In this report, we focus on the provision of ECE to children in the year prior to full-time schooling. This mainly involves children aged 4 years old; however, as discussed below, this is affected to some extent by the variation in school starting ages across the different states and territories (see also Edwards, Taylor, & Fiorini, 2011).

2.1 Models of early childhood education delivery

Reflecting the federal system of government in Australia, the delivery of early childhood education services is undertaken by the state and territory governments. Furthermore, many local governments are also involved in the provision of such services, and the result of this division of powers and responsibilities is a great deal of variation in the way in which ECE is provided (Press & Hayes, 2001).

The current system of delivery of early childhood education within and across the different states and territories is complex and multifaceted, with services being provided in a mix of contexts, including kindergartens, stand-alone preschools, long day care (LDC) settings, early learning centres, and preschool programs within the independent school sector. These services are also delivered through a variety of different "providers" that involve "complex layers and connections between government, voluntary and church groups, public education systems, independent, Catholic and other religious schools, community organisations, free-market forces, small business owner-operators and major commercial childcare companies, plus of course families and children" (Elliott, 2006, p. 1).

While a mix of service provision exists within all of the states and territories, two major, distinct models can be derived (Dowling & O'Malley, 2009). The first is one where ECE is primarily funded and delivered by government, and the second is where the government subsidises ECE but the service is primarily delivered by non-government agencies. These two models broadly have the characteristics summarised in Table 1.

In the Australian context, while no state or territory system fits wholly within one or other of these models, it has been argued that the provision of ECE in South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory sits more within the first model (government-funded and delivered) and New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland have a model of service delivery that is more like the second model (where government subsidises services that are delivered by other agencies) (Dowling & O'Malley, 2009; Urbis Social Policy, 2011). However, as Dowling and O'Malley (2009) pointed out, all jurisdictions involve a "mix of the two and the reality is more complex than the models suggest" (p. 4). For example, private providers operate within states that are primarily model 1 and some government-run preschools operate in model 2 states, such as New South Wales.

| Model 1: Government model | Model 2: Non-government model |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: Urbis Social Policy (2011), p. 91

There is also significant diversity in what ECE services in the year prior to children commencing full-time schooling are called across the different states and territories. For example, "kindergarten" is used in Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania; "preschool" in New South Wales, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory; and both "kindergarten" and "preschool" in Victoria and South Australia.

The age at which children participate in ECE in the year prior to commencing full-time school also varies between the jurisdictions, reflecting the different school starting ages between the states and territories. Table 2 provides a summary of the different characteristics of ECE across the jurisdictions, and also provides some additional details about the different ways in which it is delivered.

| Jurisdiction | Year before full-time schooling | First year of full-time schooling | Characteristics of model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW | Name | Preschool | Kindergarten | Non-government model. Mixed system, with most programs provided by LDC services and community preschools, and regulated by the NSW Department of Community Services. Also 100 preschools are attached to primary schools and administered by the Department of Education and Training. |

| Age | 4 years by 31 July | 5 years by 31 July | ||

| Vic. | Name | Kindergarten | Preparatory | Non-government model. Mixed system, with programs provided by LDC services, community facilities, children's hubs and schools. Most services are run by local governments and businesses. ECE is funded by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Requires teachers with ECE qualifications in addition to tertiary degrees. |

| Age | 4 years by 30 April | 5 years by 30 April | ||

| Qld | Name | Kindergarten | Preparatory | Non-government model. ECE is primarily provided by community providers and regulated and funded by the Department of Education, Training and the Arts. |

| Age | 4 years by 30 June | 5 years by 30 June | ||

| SA | Name | Kindergarten | Reception | Government model. A number of preschools are staffed and funded by the education department and integrated with or linked to schools. Requires teachers with ECE qualifications in addition to tertiary degrees. Government-provided preschool education is free, with a voluntary levy. |

| Age | 4th birthday | 5th birthday | ||

| WA | Name | Kindergarten | Pre-primary | Government model. A number of preschools are staffed and funded by the education department and integrated with or linked to schools. Requires teachers with ECE qualifications in addition to tertiary degrees. Government-provided preschool education is free, with a voluntary levy. |

| Age | 4 years by 30 June | 5 years by 30 June | ||

| Tas. | Name | Kindergarten | Preparatory | Government model. A number of preschools are staffed and funded by the education department and integrated with or linked to schools. Government-provided preschool education is free, with a voluntary levy. |

| Age | 4 years by 1 January | 5 years by 1 January | ||

| NT | Name | Preschool | Transition | Government model. A number of preschools are staffed and funded by the education department and integrated with or linked to schools. Government-provided preschool education is free, with a voluntary levy. |

| Age | 4th birthday | 5 years by 30 June | ||

| ACT | Name | Preschool | Kindergarten | Government model. A number of preschools are staffed and funded by the education department and integrated with or linked to schools. Requires teachers with ECE qualifications in addition to tertiary degrees. Government-provided preschool education is free, with a voluntary levy. |

| Age | 4 years by 30 April | 5 years by 30 April | ||

Source: Urbis Social Policy (2011), in particular, pp. 90-91

2.2 Participation in early childhood education

Enrolment rates for children in ECE in the year prior to full-time schooling are provided by the states and territories in the NP ECE annual reports for 2010.2 Table 3 shows the enrolment rates and proportions of children enrolled in ECE programs for each state, as well as the proportions of children enrolled in a program where at least 15 hours per week is available. Given the diversity of the systems of ECE operating in the different jurisdictions, and the different starting points for each of the states and territories at the beginning of the NP ECE, the enrolment rates are still somewhat varied across states. However, all jurisdictions reported positive progress in regard to meeting the targets of the National Partnership.

| Jurisdiction | Enrolment rates in all ECE programs (%) | Enrolment rates in ECE programs where at least 15 hours per week available (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NSW | 86.2 | 41 |

| Vic. | 99.9 | 18.4 |

| Qld | 40 | 55 |

| SA | 87.7 | 28.8 |

| WA | 97.5 | 26.2 |

| Tas. | 97 | 33.4 |

| NT | 88.4 | 36 |

| ACT | 95.4 | 27.2 |

Note: Figures have been presented here with and without decimal places - as they were presented in the original documents. Note that state/territory estimates are not derived using a consistent methodology.

Source: NP ECE annual reports (2010). The figures in this table are drawn from the annual reports for the 2010 calendar year provided by each of the states and territories about their progress with NP ECE targets. See footnote 2.

Reflecting the diversity of service provision within all of the states and territories, issues around accurately measuring and tracking progress against the performance indicators were indicated to some extent in almost all of the 2010 annual reports. Key issues shared across some of the jurisdictions included:

- concerns about the quality of the baseline measures;

- the variable quality of population estimates used for calculating proportions of children participating in ECE (particularly when small age and geographic cohorts were involved); and

- difficulties in accessing comparable data across different service contexts in terms of both the measures used and the timing of measures.

2 Annual reports about the progress of the NP ECE are provided by each of the state and territory governments. The individual reports are available from the DEEWR website at <www.deewr.gov.au/Earlychildhood/Policy_Agenda/ECUA/Pages/annualreports.aspx>.

3. Methodology and data

In order to address the objectives outlined in Section 1, this project used a range of methodologies:

- consultating with key stakeholders, including state and territory government departments responsible for implementing the COAG agreement, as well as other stakeholders with interests in the wellbeing of young children;

- undertaking a comprehensive review of international and Australian literature; and

- analysing a range of Australian datasets.

Results from each approach have been integrated throughout the report. A description of the first two of these methodologies is provided below, with more detail about the data analyses provided in Appendix B.

3.1 Consultations with stakeholders

A key component of the project was consulting with state and territory government departments that have responsibility for early childhood education. These consultations were particularly important in addressing questions around how access to early childhood education was conceptualised within each of the different states and territories, issues around measuring access, and the factors affecting participation in ECE and the various groups that may not be accessing ECE within the different jurisdictions.

Consultations with government stakeholders mainly took place with departmental officers involved in the implementation of the NP ECE. Participation from each of the jurisdictions was sought via the ECDSG, with members from each of the states and territories agreeing to be the initial contact points for arranging discussions.

Discussions took place with departmental officers from each of the states and territories from July through to September 2011. Most discussions involved groups of between two and eight participants and generally took between one and two hours. With the participants' consent, the discussions were audio-recorded and then transcribed to ensure that the content of the discussions was accurately documented and to allow a detailed review of the discussions to be undertaken.

Discussions usually commenced with some background information about how early childhood education was being delivered within the jurisdiction and any significant changes that had taken place in its delivery since the signing of the COAG agreement. The discussion then focused on the three broad areas of the Access to Early Childhood Education Project. These involved asking participants about the following areas:

- Defining and conceptualising access to early childhood education services:

- How is "access" defined or conceptualised in the jurisdiction?

- Factors affecting access to early childhood education services:

- Within the jurisdiction, what different delivery systems exist (i.e., school-based, community-based, long-day-care-based, integrated and specialised/targeted services)? To what extent do these different systems affect participation?

- What are the factors that participants have observed that influence a family's decision about whether or not to access early childhood education services for their children?

- Are there different access issues for different cohorts of the population in the jurisdiction (e.g., low socio-economic status; Indigenous, remote or other disadvantaged groups) and if so, how may these be addressed?

- Measuring access to early childhood education services:

- How do departments in the jurisdiction measure access to early childhood education services?

- What issues has the jurisdiction encountered in measuring access?

AIFS also consulted with a range of other stakeholders in order to gain a broader range of perspectives on what constitutes access, what critical issues affect access. and the difficulties that early childhood education services face in providing accurate and consistent data to allow state and territory departments to measure access. These stakeholders included children's commissions, and organisations representing service providers, early childhood teachers and other agencies with interests in the wellbeing of young children. These stakeholders were approached in a variety of ways. In some cases, the different jurisdictions organised for these stakeholders to take part; either in the same discussion as the departmental stakeholders or in a separate meeting. Other jurisdictions provided a list of stakeholders, which were then contacted by the research team. Two of the stakeholders provided written submissions rather than participating in a discussion. In total, 40 different other stakeholders took part in the consultations.

The discussions focused on the same broad themes as those with the government stakeholders and the same questions were used as the starting point. While some of the stakeholders were happy to be identified and have their comments attributed to them, most were not.

With the agreement of those who contributed to the project, the information provided from these discussions has been reported confidentially. Any information that may have identified an individual has been removed throughout the report.

3.2 Literature review

To inform and supplement the consultations and data analyses, AIFS undertook a systematic literature review on the topic of early childhood education.

The focus of the search was the factors parents take into account when deciding whether or not their children will participate in early childhood education, as well as the structural factors that may support or inhibit the participation of children in these services. In addition, the search considered particular groups that may be less likely to participate in early childhood education, such as children with disabilities, or those from low-income, culturally and linguistically diverse or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background to explore potential barriers to their participation.

The Institute also commissioned Professor Peter Moss (Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London) to provide an international perspective on the issues encompassed by this research project. This international context helps explain the conceptualisation of "access" and the measurement of participation in ECE in an international context. The report by Professor Moss is included in Appendix A and the results from the literature review have been integrated throughout the report.

3.3 Data analyses

Analyses of existing datasets were undertaken to explore factors related to access to early childhood education services and to explore parental decision-making. The datasets primarily used were:

- the National Survey of Parents' Child Care Choices (NSPCCC), 2009;

- the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), 2008;

- the Australian Early Development Index (AEDI), 2009; and

- the Childhood Education and Care Survey (CEaCS), 2008.3

The main uses of each dataset are summarised in Table 4.

| Data source | Uses |

|---|---|

| National Survey of Parents' Child Care Choices (2009) | Children who were likely to be in the year before full-time schooling were identified and the analyses focused on these children. These data were then used to analyse:

|

| Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (2008) | The B cohort at Wave 3 was used, when children were aged 4-5 years (in 2008). Of these children, those identified by parents as being in the year before full-time schooling were the focus of the analyses. These data were then used to analyse:

|

| Australian Early Development Index (2009) | From this source, data are available from almost all children across Australia in their first year of full-time schooling in 2009, on their enrolment in care or early education before starting school. This information was used to analyse:

|

| Childhood Education and Care Survey (2008) | This survey was used to analyse parental decision-making and barriers regarding participation in ECE, and in different types of ECE. |

Each of these data sources had some limitations in being able to fully explore children's access to ECE. Difficulties in measuring ECE, as encountered in these analyses, are described in subsection 4.3. Appendix B includes details of how each dataset was used, and associated issues related to scope and definition.

Table 5 presents a summary of the estimates of participation in ECE - derived from NSPCCC, LSAC and AEDI - for children in the year before full-time school. NSPCCC provides estimates for 2009, while LSAC and AEDI refer to participation in 2008. The AEDI data were collected retrospectively in 2009. The different timing of these collections may contribute to the variation across data sources in estimates of participation in ECE. Note that there are some differences in the data items and classifications used in each survey, because of differences in the availability of ECE information.

| NSPCCC | LSAC | AEDI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participation rates |

|

|

|

| Period of data collection | As at time of collection in May 2009. | As at time of collection. Most interviews held between April and October 2008. | Collected in 2009, in regard to ECE in 2008. |

| Methodology | Sample survey. Includes children estimated to be in year before full-time school, based on exact age of child and state of residence. | Sample survey. Includes children aged 4-5 years who were in year before full-time school, as determined by parents' reports of expected school attendance in the following year. | Population-based collection. Completed by teachers, using school enrolment details. Covers most children in first year of full-time school. |

| No. of observations | N = 1,637 | N = 3,005 | N = 236,251 |

Note: The different classifications used in each collection reflect differences in the underlying ECE data available from each source. The main differences relate to children in LDC, and being able to accurately identify those children who attended a preschool program in the LDC. This was captured well in NSPCCC. While LSAC allowed children to be classified to "LDC with a preschool program", some of those who were instead classified as "LDC" may have received a preschool program. In AEDI, a high proportion of teachers could not differentiate between LDC with or without a preschool program, and so this distinction was not used and, instead, if children attended an LDC this was classified as "LDC with or without a preschool program". See Appendix B for more detailed information.

In each dataset, children in the year before full-time school were identified. Of these children, those participating in preschool or long day care were considered to be in ECE. Overall, in NSPCCC, 82% of children were in ECE in the year before full-time school, in LSAC 93% and in AEDI 89%. State-level estimates are shown in Table 6, with more detail, including the classifications shown in Table 5, presented in Appendix C.

| NSW (%) | Vic. (%) | Qld (%) | SA (%) | WA (%) | Tas. (%) | NT (%) | ACT (%) | Aus. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children in ECE | |||||||||

| NSPCCC (2009) | 84.9 | 84.6 | 77.4 | 73.7 | 79.8 | 85.6 | 77.8 | 88.9 | 82.1 |

| LSAC (2008) | 89.8 | 98.7 | 81.0 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 92.9 |

| AEDI (2009) | 88.4 | 94.1 | 83.1 | 94.1 | 88.2 | 93.8 | 88.5 | 94.5 | 89.2 |

| Children enrolled in ECE in 2010 | |||||||||

| 2010 annual reports | 86.2 | 99.9 | 40 | 87.7 | 97.5 | 97.0 | 88.4 | 95.4 | n.a. |

Note: The discrepancy between survey estimates and official enrolment figures for Queensland relate to the different treatment of LDC in each source. All children participating in LDC are included in the participation rates in the survey data; however, in the official estimates, LDC is only included as ECE in particular situations.

Source: AEDI (2009), NSPCCC (2009), LSAC (2008) and COAG (2008) (see Table 3).

There is some variation in national and state/territory estimates, depending upon which source is used. These estimates also differ from the official estimates presented in Section 2. These differences reflect that each data source varies in scope, timing and the definitions of ECE used, as well as the underlying data collection methodology. We do not attempt to explain these differences in detail, but instead will be using these data to explore how participation rates (and types of ECE) vary within data sources according to different child, family and regional characteristics. We also do not consider one dataset to be superior to the others overall, as each has its strengths and weaknesses. For example, NSPCCC is useful because of the detailed questions concerning different types of ECE participation. LSAC is useful because of the large range of child, family and regional characteristics that can be related to ECE participation, in addition to the quite large sample size. The strength of the AEDI lies in the very large number of observations, with ECE information being available for all children in the dataset.

The focus throughout the data analyses is on overall levels of participation in and types of ECE. These analyses do not consider the hours of ECE received, nor workforce issues such as the educational attainment of early education workers.

Other datasets were considered when scoping this report. One potential data source was the Australian Census of Population and Housing. However, concerns about the data being able to identify children receiving early childhood education, as well as being able to identify those who were eligible, led to our decision to not include this data source. Data from the Australian Government Census of Child Care Services, the National Preschool Census and the National Early Childhood Education and Care Workforce Census were also not used in this report. There may be value in examining the potential for analysing early childhood education with these datasets in the future.4

3 See Acknowledgement and Appendix B for details of the organisations that fund and administer these projects.

4 To examine issues specific to Indigenous children, we also considered using the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey and the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC). These surveys offer the potential to analyse some of the detail of Indigenous children's participation in ECE (e.g., number of days or hours of ECE), but are less useful for measuring access in the same way as has been done with the other datasets. Also, participation in ECE by Indigenous children has already been analysed using LSIC data by Hewitt and Walter (2011).

4. Understanding "access" to early childhood education

This section explores how "access" to early childhood education services is defined, the factors that may affect access, and issues related to its measurement according to both the Australian and international literatures and from discussions with the key government and non-government stakeholders.

4.1 What is "access"?

The term "access" is often used in relation to the care and education of young children, but is often not clearly defined. In the context of the stated goals of the National Partnership, outlined in Section 1 of this report, "access", in its simplest form, can mean the opportunity to participate in ECE, among those families who would like their children to take part. At the most basic level, this can be interpreted as meaning that there are places available for all children whose families would like them. However, the goals of the National Partnership also highlight the importance of families having the freedom or ability to make use of ECE, as reflected in the focus placed on affordability, quality and participation rates within the National Partnership Agreement.

What is "access" according to key stakeholders?

A key question for the stakeholder consultations undertaken for the Access to Early Childhood Education Project was the way in which "access" was defined or conceptualised within the government jurisdictions or non-government organisations. The broad issues raised as part of the stakeholder discussions were similar in scope to those embedded within the National Partnership Agreement; that is, stakeholders generally described it in a multidimensional way, including the following components:

- creating opportunities for children to participate in ECE programs;

- providing enough time within the programs for children to learn; and

- allowing children to experience the program (and its potential benefits) fully.

The relationship between these components and the aims of the National Partnership Agreement, particularly for departmental officers, is not surprising given that they are working to implement the goals of universal access within their own jurisdictions. However, there was some variation that emerged in the discussions. To some extent, this was related to participants' own roles within their organisations (for example, people involved in managing and collecting data tended to be more focused on participation rates, while people from a practice background often saw the nature of children's experience as being at the core of access), as well as to what the core focus of their jurisdiction was at the time of discussions. Nevertheless, it is important to note that in all discussions, "access" was referred to in a multidimensional manner.

Not surprisingly, all officers from state and territory government departments involved in implementing the NP ECE, in the first instance described "access" as having enough places within the service system for all eligible children to be able to attend ECE programs:

Access is the ability for every child to go and access a program. That a place is available for each child. (Departmental officer)

There's an entitlement that any child … can access that year of education. (Departmental officer)

However, it was acknowledged that access was a more complex issue than simply providing a place:

Basically, if you live in [state], you have the entitlement to be able to access a preschool … We certainly acknowledge the difficulties here that all families can access, you know, are able to access preschool, but there's "access" and there's "access". But from the position of the [state] government, we're providing it to all children, should they want it. That's a very important point. (Departmental officer)

So in most discussions with stakeholders (government or otherwise), the ability to provide a place for children to enrol in early childhood education, was seen as the "starting point" for providing access:

Enrolments are our first starting point, basically, for determining the access to preschool programs. Another aspect that has to do with access is that we are targeting specific groups within the general population in terms of providing supply of preschool programs. (Departmental officer)

This notion of targeting specific groups to encourage participation was another issue frequently discussed by stakeholders. For many of the departmental officers, access was also being considered within their own jurisdictions in terms of who wasn't participating:

For the first part of universal access, we hit the mainstream, but now we are focusing on the more hard-to-reach groups. (Departmental officer)

Universal access is good for [state] because it gives us a chance to deal with some of the more fringe issues. (Departmental officer)

However, there was also general agreement among participants that some parents would ultimately choose never to make use of services, regardless of what was made available:

That is the aim, to maximise access, but … some parents may feel they have access - they can easily access a service, but they don't want to. (Departmental officer)

Subsection 4.2 provides a more detailed discussion of the characteristics that stakeholders reported were associated with lower levels of access to early childhood education.

For many of the departmental stakeholders, a key focus in the discussion about "access" was also the amount of time that children spent in an ECE program. Again, to some extent this was driven by the agreement under the NP ECE, in which providing "access" involves delivering access to programs for 15 hours per week. While on the whole this was viewed positively by participants, it was also seen as being potentially a risk to access by specific groups, such as younger children (specifically relating to 3-year-old kindergarten programs) and children with special needs:

It will certainly have an impact around supporting the inclusion of children with disabilities. I think that there will be a greater demand for resources to support their attendance for 15 hours. (Departmental officer)

A number of participants also extended the notion of access beyond examining participation rates and barriers to enrolments and attendance. They described the need to examine the extent to which children are able to fully experience the program they attend and be able to make the most of the benefits on offer:

What does "access" really mean? … I think we're talking about getting children in the door, but we're actually talking around what is meaningful participation. I think that is the key too. (Departmental officer)

Access is more than a place for every child. We understand that the place and the child need to be compatible. So where they're not compatible, we need to provide something a bit different. (Departmental officer)

Non-government stakeholders had less to say about the broader meanings of "access", as they tended to have a focus that reflected their more specific interests around barriers and particular groups. But some did provide some broader statements. Like those of the government stakeholders, these descriptions were multidimensional and took into account being able to both attend ECE programs and gain from the experience in a meaningful way:

Access can mean many things. The ability to get a child to preschool for working parents, the ability of a child to access the curriculum and the supports for them to do so … Being able to access a preschool that is within the community (religious or cultural) that they are a part of. (Service provider)

For optimal wellbeing, children and young people need to be actively engaged in learning, with a curriculum that meets their educational needs. Clearly, universal access (as defined by the NP Agreement) is an important, but minimum, first step. (Non-government stakeholder)

What is "access" according to the literature?

As was evident from discussions with the stakeholders, our review of the Australian and international literature found that "access" tends to be defined and conceptualised in a multidimensional manner.

At a minimum, such definitions usually involve a focus on creating opportunities for families and children to participate in ECE programs. However, providing access is usually acknowledged within the literature as going beyond simply having places available for children. For example, Press and Hayes, in 2001, described access to ECE as meaning that while "first and foremost places must be available; it must suit the family's needs in terms of location, hours available and the service provided; it must meet at least a minimum standard of quality; and it must be affordable" (p. 30).

Like the stakeholders interviewed for this project, the literature recognises that having enough places for all children to attend an ECE program does not mean that they will. For example, in his review for this project of early childhood education and care (ECEC) in OECD countries, Peter Moss (Appendix A) cited the OECD argument that "universal access does not necessarily entail achieving full coverage, as there are variations in demand for ECEC at different ages and in different family circumstances. Rather, it implies making access available to all children whose parents wish them to participate" (OECD, 2006, cited in Moss, Appendix A )

However, Moss (Appendix A) agreed with Press and Hayes that "to make access to ECEC a realistic option - services have to meet certain conditions. For example they need to be free or available at a price parents can afford … to provide an offer that parents need and want, in terms for example of quality, opening hours and type of provision. In sparsely populated areas they need to be physically available … Last but not least, ECEC services need to recognise and be responsive to the diversity of children and families and their needs".

Another section of the literature states that access to early childhood education should be a "citizenship right" for young children and their families (Petriwskyj, 2010). In this way of considering access, children's ability to participate in ECE and to experience its benefits is seen as a key part of their rights as citizens of the countries in which they live. In this context, creating programs that meet the needs of the children who attend them - to be "inclusive" - is seen as a basic right for children. A key part of this discussion, however, is whether this can be achieved by creating programs that can be inclusive of all children or whether more individualised and tailored programs need to be developed to meet different children's needs (Petriwskyj, 2010). Not all commentators see the notion of children as citizens as being useful for this debate, and they argue that to try and frame discourses around children's access to ECE does not take into account that children are not able to exercise their rights as citizens in the same ways in which adults can (both legally and practically) (Millei & Imre, 2009).

4.2 What factors affect access to early childhood education?

Taking into account both the literature and the consultations with stakeholders, it is clear that a key part of the "access" discussion involves the idea that not all children are able to make use of ECE equally; that is, there are factors that influence the extent to which different groups engage with ECE services, and there are a number of potential barriers that may affect children's and families' access to these services.

A number of factors affecting the participation of children in ECE that consistently emerged throughout the literature reviews and stakeholder consultations include:

- parents' preferences and beliefs;

- locational factors, such as remoteness and living in disadvantaged communities;

- the socio-economic status of families;

- the Indigenous status of families;

- whether children have a culturally and linguistically diverse background; and

- whether children experience disability or have special health care needs.

In line with these discussions, the literature and stakeholder discussions also identified a number of groups that were seen as being less likely to access ECE in the year before full-time school. These included:

- children from remote communities;

- children from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds;

- children from Indigenous backgrounds;

- children from non-English speaking backgrounds (NESB); and

- children experiencing disability or having special health care needs.

The findings from the literature review and stakeholder discussions for each of these factors and groups are provided below. These factors and groups also form the basis of the analyses of various datasets undertaken for the Access to Early Childhood Education Project. The findings from these analyses are reported on in Sections 5 and 6 of this report.

Parental decision-making and preferences

A strong theme in the discussions with stakeholders was that while governments can provide places that meet a broad range of families' needs, there would always be some families who would choose not to allow their children to participate in ECE. This reluctance on the part of families was sometimes seen by the stakeholders as being due to a lack of understanding of the potential benefits of ECE. Some participants were keen to find ways of better communicating these benefits to families; however, others felt there would always be a small group who believed that children should not be cared for by adults other than family members until they commenced full-time school.

Research around parental beliefs about the use of child care does support this latter view (Hand, 2005; Hand & Hughes, 2004; Holloway, 1998). In addition, the research has found that these concerns may be mitigated if parents feel that the programs offered fit with their own parenting beliefs, or are offered by providers who they see as supporting their own childrearing beliefs and practices (Holloway, 1998; Wise & Da Silva, 2007). This argument was also posited by Moss (Appendix A), who noted that "changing parental expectations and understandings of good parenting and a good childhood" can also affect demand from parents for ECEC, as does "a high level of parental satisfaction with well developed and accessible" systems of ECEC.

Location

A key issue for many of the jurisdictions was the provision of ECE for children living in remote locations. More remote regions are, by definition, further away from the larger service centres and so when services are required, travelling distances can be large. In itself, this is likely to affect rates of access to ECE, and consultations with stakeholders frequently raised the challenges of service provision in remote areas. This was often discussed in terms of distances to be travelled; however, it was also acknowledged that as remoteness increases, population density declines, and because of the sparser distribution of the population, smaller numbers of services can be funded to meet the needs of families in those areas, again potentially increasing the distances families need to travel. Conversely, if the program is delivered closer to home, it may decrease the potential for children to experience the more social aspects of ECE if there are no other children of the same age available to participate.

The availability of suitably qualified and experienced staff is also an ongoing issue for remote area service provision. Attracting and retaining staff to remote services was a key concern for many stakeholders and, as recorded in other research, it was noted that even where ECE teachers were available to provide programs, ongoing turnover of staff had the potential to diminish quality, as "in these communities, there is little consistency or knowledge of local families and children" (Walker, 2004, p. 39).

It is likely, then, that families in remote areas may have more difficulty in accessing a high-quality ECE service within a reasonable distance from their home.

Socio-economic status of families

A key concern for participants in the stakeholder discussions was the engagement of families who live in disadvantaged areas or experience socio-economic disadvantage. Stakeholders from both government and non-government sectors reported that children from low socio-economic backgrounds continue to be under-represented in ECE. This was seen to be a result of a number of factors, including issues relating to costs (real or perceived), a lack of awareness of available services or the benefits of ECE, and the "interference" of other factors that co-exist with financial disadvantage, such as parental physical and/or mental health issues, drug and alcohol problems and poor experiences of education. Other potential barriers for this group included parents having a lack of access to transport, having poor English language skills and not feeling welcome by the services available to them.